User login

Mortality trends in childhood after infant bacterial meningitis

Among infants younger than 1 year of age, bacterial meningitis is associated with worse long-term mortality, even after recovery from the initial infection. Heightened mortality risk stretched out to 10 years, and was highest in the wake of infection from Streptococcus agalactiae, according to a retrospective analysis of children in the Netherlands.

“The adjusted hazard rates were high for the whole group of bacterial meningitis, especially within the first year after onset. (Staphylococcus agalactiae) meningitis has the highest mortality risk within one year of disease onset,” Linde Snoek said during her presentation of the study (abstract 913) at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year. Ms. Snoek is a PhD student at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Over longer time periods, the mortality associations were different. “The adjusted hazard rates were highest for pneumococcal meningitis compared to the other pathogens. And this was the case for 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years after disease onset,” said Ms. Snoek.

The study appears to be the first to look at extended mortality following bacterial meningitis in this age group, according to Marie Rohr, MD, who comoderated the session where the research was presented.

“In a quick review of the literature I did not find any [equivalent] study concerning short- and long-term mortality after bacterial meningitis in under 1 year of age,” said Dr. Rohr, a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at University Hospitals of Geneva. But the message to physicians is clear. “Children with history of bacterial meningitis have a higher long-term mortality than children without a history of bacterial meningitis,” said Dr. Rohr.

The study did have a key limitation: For matched controls, it relied on anonymous data from the Municipal Personal Records Database in Statistics Netherlands. “Important information like cause of death is lacking,” said Dr. Rohr.

Bacterial meningitis is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. Pathogens behind the infections vary with age group and geographic location, as well as immunization status.

To examine long-term mortality after bacterial meningitis, the researchers collected 1,646 records from an exposed cohort, with a date range of 1995 to 2018, from the Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis. Included patients had a positive culture diagnosis of bacterial meningitis during the first year of life. Each exposed subject was compared to 10 controls matched by birth month, birth year, and sex, who had no exposure to bacterial meningitis.

Staphylococcus pneumoniae accounted for the most cases, at 32.0% (median age of onset, 180 days), followed by Neisseria meningitidis at 29.0% (median age of onset, 203 days). Other pathogens included S. agalactiae (19.7%, 10 days), Escherichia coli (8.8%, 13 days), and Haemophilus influenzae (5.4%, 231 days).

The mortality risk within 1 year of disease onset was higher for all pathogens (6.2% vs. 0.2% unexposed). The highest mortality risk was seen for S. agalactiae (8.7%), followed by E. coli (6.4%), N. meningitidis (4.9%), and H. influenzae (3.4%).

Hazard ratios (HR) for mortality were also higher, particularly in the first year after disease onset. For all pathogens, mortality rates were higher within 1 year (HR, 39.2), 5 years (HR, 28.7), and 10 years (HR, 24.1). The consistently highest mortality rates were associated with S. pneumoniae over 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year follow-up (HR, 42.8; HR, 45.6; HR, 40.6, respectively). Within 1 year, the highest mortality rate was associated with N. meningitidis (HR, 58.4).

Ms. Snoek and Dr. Rohr have no relevant financial disclosures.

Among infants younger than 1 year of age, bacterial meningitis is associated with worse long-term mortality, even after recovery from the initial infection. Heightened mortality risk stretched out to 10 years, and was highest in the wake of infection from Streptococcus agalactiae, according to a retrospective analysis of children in the Netherlands.

“The adjusted hazard rates were high for the whole group of bacterial meningitis, especially within the first year after onset. (Staphylococcus agalactiae) meningitis has the highest mortality risk within one year of disease onset,” Linde Snoek said during her presentation of the study (abstract 913) at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year. Ms. Snoek is a PhD student at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Over longer time periods, the mortality associations were different. “The adjusted hazard rates were highest for pneumococcal meningitis compared to the other pathogens. And this was the case for 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years after disease onset,” said Ms. Snoek.

The study appears to be the first to look at extended mortality following bacterial meningitis in this age group, according to Marie Rohr, MD, who comoderated the session where the research was presented.

“In a quick review of the literature I did not find any [equivalent] study concerning short- and long-term mortality after bacterial meningitis in under 1 year of age,” said Dr. Rohr, a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at University Hospitals of Geneva. But the message to physicians is clear. “Children with history of bacterial meningitis have a higher long-term mortality than children without a history of bacterial meningitis,” said Dr. Rohr.

The study did have a key limitation: For matched controls, it relied on anonymous data from the Municipal Personal Records Database in Statistics Netherlands. “Important information like cause of death is lacking,” said Dr. Rohr.

Bacterial meningitis is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. Pathogens behind the infections vary with age group and geographic location, as well as immunization status.

To examine long-term mortality after bacterial meningitis, the researchers collected 1,646 records from an exposed cohort, with a date range of 1995 to 2018, from the Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis. Included patients had a positive culture diagnosis of bacterial meningitis during the first year of life. Each exposed subject was compared to 10 controls matched by birth month, birth year, and sex, who had no exposure to bacterial meningitis.

Staphylococcus pneumoniae accounted for the most cases, at 32.0% (median age of onset, 180 days), followed by Neisseria meningitidis at 29.0% (median age of onset, 203 days). Other pathogens included S. agalactiae (19.7%, 10 days), Escherichia coli (8.8%, 13 days), and Haemophilus influenzae (5.4%, 231 days).

The mortality risk within 1 year of disease onset was higher for all pathogens (6.2% vs. 0.2% unexposed). The highest mortality risk was seen for S. agalactiae (8.7%), followed by E. coli (6.4%), N. meningitidis (4.9%), and H. influenzae (3.4%).

Hazard ratios (HR) for mortality were also higher, particularly in the first year after disease onset. For all pathogens, mortality rates were higher within 1 year (HR, 39.2), 5 years (HR, 28.7), and 10 years (HR, 24.1). The consistently highest mortality rates were associated with S. pneumoniae over 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year follow-up (HR, 42.8; HR, 45.6; HR, 40.6, respectively). Within 1 year, the highest mortality rate was associated with N. meningitidis (HR, 58.4).

Ms. Snoek and Dr. Rohr have no relevant financial disclosures.

Among infants younger than 1 year of age, bacterial meningitis is associated with worse long-term mortality, even after recovery from the initial infection. Heightened mortality risk stretched out to 10 years, and was highest in the wake of infection from Streptococcus agalactiae, according to a retrospective analysis of children in the Netherlands.

“The adjusted hazard rates were high for the whole group of bacterial meningitis, especially within the first year after onset. (Staphylococcus agalactiae) meningitis has the highest mortality risk within one year of disease onset,” Linde Snoek said during her presentation of the study (abstract 913) at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year. Ms. Snoek is a PhD student at Amsterdam University Medical Center.

Over longer time periods, the mortality associations were different. “The adjusted hazard rates were highest for pneumococcal meningitis compared to the other pathogens. And this was the case for 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years after disease onset,” said Ms. Snoek.

The study appears to be the first to look at extended mortality following bacterial meningitis in this age group, according to Marie Rohr, MD, who comoderated the session where the research was presented.

“In a quick review of the literature I did not find any [equivalent] study concerning short- and long-term mortality after bacterial meningitis in under 1 year of age,” said Dr. Rohr, a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at University Hospitals of Geneva. But the message to physicians is clear. “Children with history of bacterial meningitis have a higher long-term mortality than children without a history of bacterial meningitis,” said Dr. Rohr.

The study did have a key limitation: For matched controls, it relied on anonymous data from the Municipal Personal Records Database in Statistics Netherlands. “Important information like cause of death is lacking,” said Dr. Rohr.

Bacterial meningitis is associated with significant mortality and morbidity. Pathogens behind the infections vary with age group and geographic location, as well as immunization status.

To examine long-term mortality after bacterial meningitis, the researchers collected 1,646 records from an exposed cohort, with a date range of 1995 to 2018, from the Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis. Included patients had a positive culture diagnosis of bacterial meningitis during the first year of life. Each exposed subject was compared to 10 controls matched by birth month, birth year, and sex, who had no exposure to bacterial meningitis.

Staphylococcus pneumoniae accounted for the most cases, at 32.0% (median age of onset, 180 days), followed by Neisseria meningitidis at 29.0% (median age of onset, 203 days). Other pathogens included S. agalactiae (19.7%, 10 days), Escherichia coli (8.8%, 13 days), and Haemophilus influenzae (5.4%, 231 days).

The mortality risk within 1 year of disease onset was higher for all pathogens (6.2% vs. 0.2% unexposed). The highest mortality risk was seen for S. agalactiae (8.7%), followed by E. coli (6.4%), N. meningitidis (4.9%), and H. influenzae (3.4%).

Hazard ratios (HR) for mortality were also higher, particularly in the first year after disease onset. For all pathogens, mortality rates were higher within 1 year (HR, 39.2), 5 years (HR, 28.7), and 10 years (HR, 24.1). The consistently highest mortality rates were associated with S. pneumoniae over 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year follow-up (HR, 42.8; HR, 45.6; HR, 40.6, respectively). Within 1 year, the highest mortality rate was associated with N. meningitidis (HR, 58.4).

Ms. Snoek and Dr. Rohr have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ESPID 2021

FDA approves ibrexafungerp for vaginal yeast infection

Ibrexafungerp is the first drug approved in a new antifungal class for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in more than 20 years, the drug’s manufacturer Scynexis said in a press release. It becomes the first and only nonazole treatment for vaginal yeast infections.

The biotechnology company said approval came after positive results from two phase 3 studies in which oral ibrexafungerp demonstrated efficacy and tolerability. The most common reactions observed in clinical trials were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, and vomiting.

There are few other treatments for vaginal yeast infections, which is the second most common cause of vaginitis. Those previously approved agents include several topical azole antifungals and oral fluconazole (Diflucan), which, Scynexis said, is the only other orally administered antifungal approved for the treatment of VVC in the United States and has accounted for over more than 90% of prescriptions written for the condition each year.

However, the company noted, oral fluconazole reports a 55% therapeutic cure rate on its label, which now also includes warnings of potential fetal harm, demonstrating the need for new oral options.

The new drug may not fill that need for pregnant women, however, as the company noted that ibrexafungerp should not be used during pregnancy, and administration during pregnancy “may cause fetal harm based on animal studies.”

Because of possible teratogenic effects, the company advised clinicians to verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential before prescribing ibrexafungerp and advises effective contraception during treatment.

VVC can come with substantial morbidity, including genital pain, itching and burning, reduced sexual pleasure, and psychological distress.

David Angulo, MD, chief medical officer for Scynexis, said in a statement the tablets brings new benefits.

Dr. Angulo said the drug “has a differentiated fungicidal mechanism of action that kills a broad range of Candida species, including azole-resistant strains. We are working on completing our CANDLE study investigating ibrexafungerp for the prevention of recurrent VVC and expect we will be submitting a supplemental NDA [new drug application] in the first half of 2022.”

Scynexis said it partnered with Amplity Health, a Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company, to support U.S. marketing of the drug. The commercial launch will follow the approval.

Ibrexafungerp was granted approval through both the FDA’s Qualified Infectious Disease Product and Fast Track designations. It is expected to be marketed exclusively in the United States for 10 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ibrexafungerp is the first drug approved in a new antifungal class for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in more than 20 years, the drug’s manufacturer Scynexis said in a press release. It becomes the first and only nonazole treatment for vaginal yeast infections.

The biotechnology company said approval came after positive results from two phase 3 studies in which oral ibrexafungerp demonstrated efficacy and tolerability. The most common reactions observed in clinical trials were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, and vomiting.

There are few other treatments for vaginal yeast infections, which is the second most common cause of vaginitis. Those previously approved agents include several topical azole antifungals and oral fluconazole (Diflucan), which, Scynexis said, is the only other orally administered antifungal approved for the treatment of VVC in the United States and has accounted for over more than 90% of prescriptions written for the condition each year.

However, the company noted, oral fluconazole reports a 55% therapeutic cure rate on its label, which now also includes warnings of potential fetal harm, demonstrating the need for new oral options.

The new drug may not fill that need for pregnant women, however, as the company noted that ibrexafungerp should not be used during pregnancy, and administration during pregnancy “may cause fetal harm based on animal studies.”

Because of possible teratogenic effects, the company advised clinicians to verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential before prescribing ibrexafungerp and advises effective contraception during treatment.

VVC can come with substantial morbidity, including genital pain, itching and burning, reduced sexual pleasure, and psychological distress.

David Angulo, MD, chief medical officer for Scynexis, said in a statement the tablets brings new benefits.

Dr. Angulo said the drug “has a differentiated fungicidal mechanism of action that kills a broad range of Candida species, including azole-resistant strains. We are working on completing our CANDLE study investigating ibrexafungerp for the prevention of recurrent VVC and expect we will be submitting a supplemental NDA [new drug application] in the first half of 2022.”

Scynexis said it partnered with Amplity Health, a Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company, to support U.S. marketing of the drug. The commercial launch will follow the approval.

Ibrexafungerp was granted approval through both the FDA’s Qualified Infectious Disease Product and Fast Track designations. It is expected to be marketed exclusively in the United States for 10 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ibrexafungerp is the first drug approved in a new antifungal class for vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) in more than 20 years, the drug’s manufacturer Scynexis said in a press release. It becomes the first and only nonazole treatment for vaginal yeast infections.

The biotechnology company said approval came after positive results from two phase 3 studies in which oral ibrexafungerp demonstrated efficacy and tolerability. The most common reactions observed in clinical trials were diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, dizziness, and vomiting.

There are few other treatments for vaginal yeast infections, which is the second most common cause of vaginitis. Those previously approved agents include several topical azole antifungals and oral fluconazole (Diflucan), which, Scynexis said, is the only other orally administered antifungal approved for the treatment of VVC in the United States and has accounted for over more than 90% of prescriptions written for the condition each year.

However, the company noted, oral fluconazole reports a 55% therapeutic cure rate on its label, which now also includes warnings of potential fetal harm, demonstrating the need for new oral options.

The new drug may not fill that need for pregnant women, however, as the company noted that ibrexafungerp should not be used during pregnancy, and administration during pregnancy “may cause fetal harm based on animal studies.”

Because of possible teratogenic effects, the company advised clinicians to verify pregnancy status in females of reproductive potential before prescribing ibrexafungerp and advises effective contraception during treatment.

VVC can come with substantial morbidity, including genital pain, itching and burning, reduced sexual pleasure, and psychological distress.

David Angulo, MD, chief medical officer for Scynexis, said in a statement the tablets brings new benefits.

Dr. Angulo said the drug “has a differentiated fungicidal mechanism of action that kills a broad range of Candida species, including azole-resistant strains. We are working on completing our CANDLE study investigating ibrexafungerp for the prevention of recurrent VVC and expect we will be submitting a supplemental NDA [new drug application] in the first half of 2022.”

Scynexis said it partnered with Amplity Health, a Pennsylvania-based pharmaceutical company, to support U.S. marketing of the drug. The commercial launch will follow the approval.

Ibrexafungerp was granted approval through both the FDA’s Qualified Infectious Disease Product and Fast Track designations. It is expected to be marketed exclusively in the United States for 10 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC: New botulism guidelines focus on mass casualty events

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Botulinum toxin is said to be the most lethal substance known. Inhaling just 1-3 nanograms of toxin per kilogram of body mass constitutes a lethal dose.

The CDC has been working on these guidelines since 2015, initially establishing a technical development group and steering committee to prioritize topics for review and make recommendations. Since then, the agency published 15 systematic reviews in Clinical Infectious Diseases early in 2018. The reviews addressed the recognition of botulism clinically, treatment with botulinum antitoxin, and complications from that treatment. They also looked at the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks and botulism in the special populations of vulnerable pediatric and pregnant patients.

In 2016, the CDC held two extended forums and convened a workshop with 72 experts. In addition to the more standard topics of diagnosis and treatment, attention was given to crisis standards of care, caring for multiple patients at once, and ethical considerations in management.

Amesh Adalja, MD, senior scholar, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, said in an interview that the new guidance “was really specific [and] was meant to address the gap in guidance for mass casualty settings.”

While clinicians are used to focusing on an individual patient, in times of crises, with multiple patients from a food-borne outbreak or a bioterrorism attack, the focus must shift to the population rather than the individual. The workshop explored issues of triaging, adding beds, and caring for patients when a hospital is overwhelmed with an acute influx of severely ill patients.

Such a mass casualty event is similar to the stress encountered this past year with COVID-19 patients swamping the hospitals, which had too little oxygen, too few ventilators, and too few staff members to care for the sudden influx of critically ill patients.

Diagnosis

Leslie Edwards, MHS, BSN, a CDC epidemiologist and botulism expert, said that “botulism is rare and [so] could be difficult to diagnose.” The CDC “wanted to highlight some of those key clinical factors” to speed recognition.

Hospitals and health officials are being urged to develop crisis protocols as part of emergency preparedness plans. And clinicians should be able to recognize four major syndromes: botulism from food, wounds, and inhalation, as well as iatrogenic botulism (from exposure via injection of the neurotoxin).

Botulism has a characteristic and unusual pattern of symptoms, which begin with cranial nerve palsies. Then there is typically a descending, symmetric flaccid paralysis. Symptoms might progress to respiratory failure and death. Other critical clues that implicate botulism include a lack of sensory deficits and the absence of pain.

Symptoms are most likely to be mistaken for myasthenia gravis or Guillain-Barré syndrome, but the latter has an ascending paralysis. Cranial nerve involvement can present as blurred vision, ptosis (drooping lid), diplopia (double vision), ophthalmoplegia (weak eye muscles), or difficulty with speech and swallowing. Shortness of breath and abdominal discomfort can also occur. Respiratory failure may occur from weakness or paralysis of cranial nerves. Cranial nerve signs and symptoms in the absence of fever, along with a descending paralysis, should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

With food-borne botulism, vomiting occurs in half the patients. Improperly sterilized home-canned food is the major risk factor. While the toxin is rapidly destroyed by heat, the bacterial spores are not. Wound botulism is most commonly associated with the injection of drugs, particularly black tar heroin.

Dr. Edwards stressed that “time is of the essence when it comes to botulism diagnostics and treating. Timely administration of the botulism antitoxin early in the course of illness can arrest the progression of paralysis and possibly avert the need for intubation or ventilation.”

It’s essential to note that botulism is an urgent diagnosis that has to be made on clinical grounds. Lab assays for botulinum neurotoxins take too long and are only conducted in public health laboratories. The decision to use antitoxin must not be delayed to wait for confirmation.

Clinicians should immediately contact the local or state health department’s emergency on-call team if botulism is suspected. They will arrange for expert consultation.

Treatment

Botulinum antitoxin is the only specific therapy for this infection. If given early – preferably within 24-48 hours of symptom onset – it can stop the progression of paralysis. But antitoxin will not reverse existing paralysis. If paralysis is still progressing outside of that 24- to 48-hour window, the antitoxin should still provide benefit. The antitoxin is available only through state health departments and a request to the CDC.

Botulism antitoxin is made from horse serum and therefore may cause a variety of allergic reactions. The risk for anaphylaxis is less than 2%, far lower than the mortality from untreated botulism.

While these guidelines have an important focus on triaging and treating mass casualties from botulism, it’s important to note that food-borne outbreaks and prevention issues are covered elsewhere on the CDC site.

Dr. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Adalja is a consultant for Emergent BioSolutions, which makes the heptavalent botulism antitoxin.

Dr. Stone is an infectious disease specialist and author of “Resilience: One Family’s Story of Hope and Triumph Over Evil” and of “Conducting Clinical Research,” the essential guide to the topic. You can find her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In Zambia, PCR tracks pertussis

In the periurban slum of Lusaka, Zambia, asymptomatic pertussis infections were common among both mothers and infants, a surprising finding since asymptomatic infections are assumed to be rare in infants. The findings suggested that pertussis should be considered in cases of chronic cough, and that current standards of treating pertussis infections in low-resource settings may need to be reexamined.

The results come from testing of 1,320 infant-mother pairs who were first enrolled at a public health clinic, then followed over at least four visits. The researchers tracked pertussis infection using quantitative PCR (qPCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs. Over the course of the study, 8.9% tested positive, although only one infant developed clinical pertussis during the study.

The study was presented by Christian Gunning, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year. The group also included researchers at Boston University and the University of Zambia, where PCR tests were conducted.

“That was amazing,” said session moderator Vana Spoulou, MD, PhD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases at National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, who is associated with Aghia Sofia Children’s Hospital of Athens. She noted that the study found that many physicians misdiagnosed coughs, believing them to be caused by another agent. “It was very interesting that there was so much pertussis spreading around in that community, and that nobody knew that it was around,” said Dr. Spoulou.

It’s important that physicians provide appropriate treatment, since ampicillin, which is typically prescribed for childhood upper respiratory illnesses, is believed to be ineffective against pertussis, while macrolides are effective and can prevent transmission.

Dr. Spoulou also noted that Zambia uses a whole cell vaccine, which is contraindicated in pregnant women because of potential side effects. “The good thing, despite that there was [a lot of] infection, there were no deaths, which means that maybe because the mother was infected, maybe some antibodies of the mother had passed to the child and could help the child to develop milder symptoms. So these are the pros and cons of natural infection,” said Dr. Spoulou.

The study took place in 2015, and participants were seen at the Chawama Public Health Clinic from about age 1 week to 4 months (with a target of seven clinic visits). Researchers recorded respiratory symptoms and antibiotics use at each visit, and collected a nasopharyngeal swab that was tested retrospectively using qPCR for Bordetella pertussis.

Real-time PCR analysis of the samples yields the CT value, which represents the number of amplification cycles that the PCR test must complete before Bordetella pertussis is detectable. The fewer the cycles (and the lower the CT value), the more infectious particles must have been present in the sample. For pertussis testing, a value below 35 is considered a clinically positive result. Tests that come back with higher CT values are increasingly likely to be false positives.

The researchers plotted a value called evidence for infection (EFI), which combined a range of CT values with the number of positive tests over the seven clinic visits to group patients into none, weak, or strong EFI. Among infants with no symptoms, 77% were in the no EFI category, 16% were in the weak category, and 7% were in the strong EFI group. Of infants with minimal respiratory symptoms, 18% were in the strong group, and 20% with moderate to severe symptoms were in the strong EFI group. Among mothers, 13% with no symptoms were in the strong group. 19% in the minimal symptom group were categorized as strong EFI, as were 11% in the moderate to severe symptom group.

The study used a full range of CT, not just positive test results (for pertussis, CT ≤ 35). Beyond contributing to composite measures such as EFI, CT values can serve as leading indicators of infectious disease outbreaks in a population, according to Dr. Gunning. That’s because weaker qPCR signals (CT > 35) can provide additional information within a large sample population. Higher CT values are successively more prone to false positives, but that’s less important for disease surveillance where sensitivity is of the highest importance. The false positive “noise” tends to cancel out over time. “It may be the case that you don’t make that call (correctly) 100% of the time for 100% of the people, but if you get it right in 80 out of 100 people, that’s sufficient to say we see this pathogen circulating in the population,” said Dr. Gunning.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Gunning and Dr. Spoulou have no relevant financial disclosures.

In the periurban slum of Lusaka, Zambia, asymptomatic pertussis infections were common among both mothers and infants, a surprising finding since asymptomatic infections are assumed to be rare in infants. The findings suggested that pertussis should be considered in cases of chronic cough, and that current standards of treating pertussis infections in low-resource settings may need to be reexamined.

The results come from testing of 1,320 infant-mother pairs who were first enrolled at a public health clinic, then followed over at least four visits. The researchers tracked pertussis infection using quantitative PCR (qPCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs. Over the course of the study, 8.9% tested positive, although only one infant developed clinical pertussis during the study.

The study was presented by Christian Gunning, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year. The group also included researchers at Boston University and the University of Zambia, where PCR tests were conducted.

“That was amazing,” said session moderator Vana Spoulou, MD, PhD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases at National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, who is associated with Aghia Sofia Children’s Hospital of Athens. She noted that the study found that many physicians misdiagnosed coughs, believing them to be caused by another agent. “It was very interesting that there was so much pertussis spreading around in that community, and that nobody knew that it was around,” said Dr. Spoulou.

It’s important that physicians provide appropriate treatment, since ampicillin, which is typically prescribed for childhood upper respiratory illnesses, is believed to be ineffective against pertussis, while macrolides are effective and can prevent transmission.

Dr. Spoulou also noted that Zambia uses a whole cell vaccine, which is contraindicated in pregnant women because of potential side effects. “The good thing, despite that there was [a lot of] infection, there were no deaths, which means that maybe because the mother was infected, maybe some antibodies of the mother had passed to the child and could help the child to develop milder symptoms. So these are the pros and cons of natural infection,” said Dr. Spoulou.

The study took place in 2015, and participants were seen at the Chawama Public Health Clinic from about age 1 week to 4 months (with a target of seven clinic visits). Researchers recorded respiratory symptoms and antibiotics use at each visit, and collected a nasopharyngeal swab that was tested retrospectively using qPCR for Bordetella pertussis.

Real-time PCR analysis of the samples yields the CT value, which represents the number of amplification cycles that the PCR test must complete before Bordetella pertussis is detectable. The fewer the cycles (and the lower the CT value), the more infectious particles must have been present in the sample. For pertussis testing, a value below 35 is considered a clinically positive result. Tests that come back with higher CT values are increasingly likely to be false positives.

The researchers plotted a value called evidence for infection (EFI), which combined a range of CT values with the number of positive tests over the seven clinic visits to group patients into none, weak, or strong EFI. Among infants with no symptoms, 77% were in the no EFI category, 16% were in the weak category, and 7% were in the strong EFI group. Of infants with minimal respiratory symptoms, 18% were in the strong group, and 20% with moderate to severe symptoms were in the strong EFI group. Among mothers, 13% with no symptoms were in the strong group. 19% in the minimal symptom group were categorized as strong EFI, as were 11% in the moderate to severe symptom group.

The study used a full range of CT, not just positive test results (for pertussis, CT ≤ 35). Beyond contributing to composite measures such as EFI, CT values can serve as leading indicators of infectious disease outbreaks in a population, according to Dr. Gunning. That’s because weaker qPCR signals (CT > 35) can provide additional information within a large sample population. Higher CT values are successively more prone to false positives, but that’s less important for disease surveillance where sensitivity is of the highest importance. The false positive “noise” tends to cancel out over time. “It may be the case that you don’t make that call (correctly) 100% of the time for 100% of the people, but if you get it right in 80 out of 100 people, that’s sufficient to say we see this pathogen circulating in the population,” said Dr. Gunning.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Gunning and Dr. Spoulou have no relevant financial disclosures.

In the periurban slum of Lusaka, Zambia, asymptomatic pertussis infections were common among both mothers and infants, a surprising finding since asymptomatic infections are assumed to be rare in infants. The findings suggested that pertussis should be considered in cases of chronic cough, and that current standards of treating pertussis infections in low-resource settings may need to be reexamined.

The results come from testing of 1,320 infant-mother pairs who were first enrolled at a public health clinic, then followed over at least four visits. The researchers tracked pertussis infection using quantitative PCR (qPCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs. Over the course of the study, 8.9% tested positive, although only one infant developed clinical pertussis during the study.

The study was presented by Christian Gunning, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year. The group also included researchers at Boston University and the University of Zambia, where PCR tests were conducted.

“That was amazing,” said session moderator Vana Spoulou, MD, PhD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases at National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, who is associated with Aghia Sofia Children’s Hospital of Athens. She noted that the study found that many physicians misdiagnosed coughs, believing them to be caused by another agent. “It was very interesting that there was so much pertussis spreading around in that community, and that nobody knew that it was around,” said Dr. Spoulou.

It’s important that physicians provide appropriate treatment, since ampicillin, which is typically prescribed for childhood upper respiratory illnesses, is believed to be ineffective against pertussis, while macrolides are effective and can prevent transmission.

Dr. Spoulou also noted that Zambia uses a whole cell vaccine, which is contraindicated in pregnant women because of potential side effects. “The good thing, despite that there was [a lot of] infection, there were no deaths, which means that maybe because the mother was infected, maybe some antibodies of the mother had passed to the child and could help the child to develop milder symptoms. So these are the pros and cons of natural infection,” said Dr. Spoulou.

The study took place in 2015, and participants were seen at the Chawama Public Health Clinic from about age 1 week to 4 months (with a target of seven clinic visits). Researchers recorded respiratory symptoms and antibiotics use at each visit, and collected a nasopharyngeal swab that was tested retrospectively using qPCR for Bordetella pertussis.

Real-time PCR analysis of the samples yields the CT value, which represents the number of amplification cycles that the PCR test must complete before Bordetella pertussis is detectable. The fewer the cycles (and the lower the CT value), the more infectious particles must have been present in the sample. For pertussis testing, a value below 35 is considered a clinically positive result. Tests that come back with higher CT values are increasingly likely to be false positives.

The researchers plotted a value called evidence for infection (EFI), which combined a range of CT values with the number of positive tests over the seven clinic visits to group patients into none, weak, or strong EFI. Among infants with no symptoms, 77% were in the no EFI category, 16% were in the weak category, and 7% were in the strong EFI group. Of infants with minimal respiratory symptoms, 18% were in the strong group, and 20% with moderate to severe symptoms were in the strong EFI group. Among mothers, 13% with no symptoms were in the strong group. 19% in the minimal symptom group were categorized as strong EFI, as were 11% in the moderate to severe symptom group.

The study used a full range of CT, not just positive test results (for pertussis, CT ≤ 35). Beyond contributing to composite measures such as EFI, CT values can serve as leading indicators of infectious disease outbreaks in a population, according to Dr. Gunning. That’s because weaker qPCR signals (CT > 35) can provide additional information within a large sample population. Higher CT values are successively more prone to false positives, but that’s less important for disease surveillance where sensitivity is of the highest importance. The false positive “noise” tends to cancel out over time. “It may be the case that you don’t make that call (correctly) 100% of the time for 100% of the people, but if you get it right in 80 out of 100 people, that’s sufficient to say we see this pathogen circulating in the population,” said Dr. Gunning.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Gunning and Dr. Spoulou have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ESPID 2021

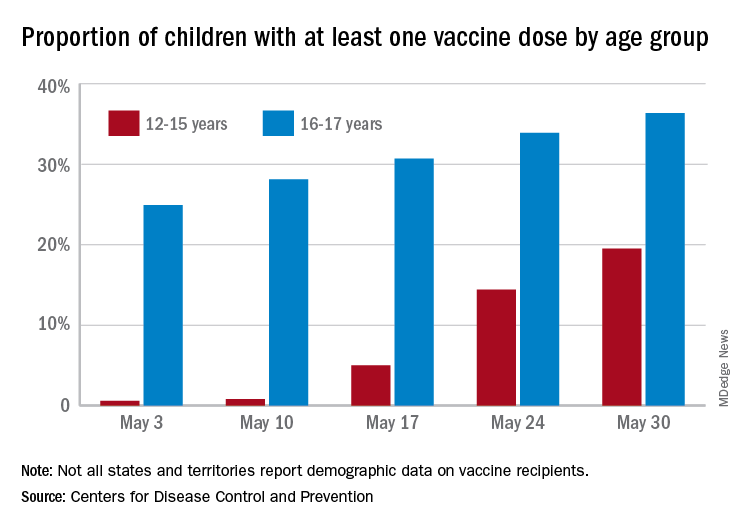

Children aged 12-15 years continue to close COVID-19 vaccination gap

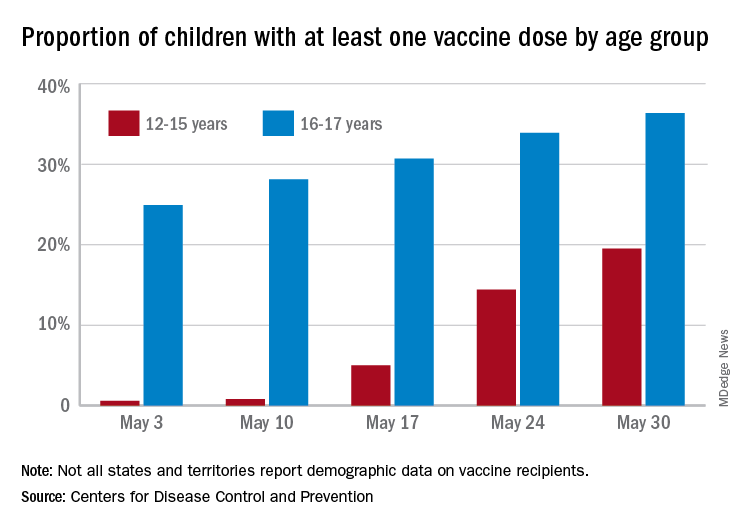

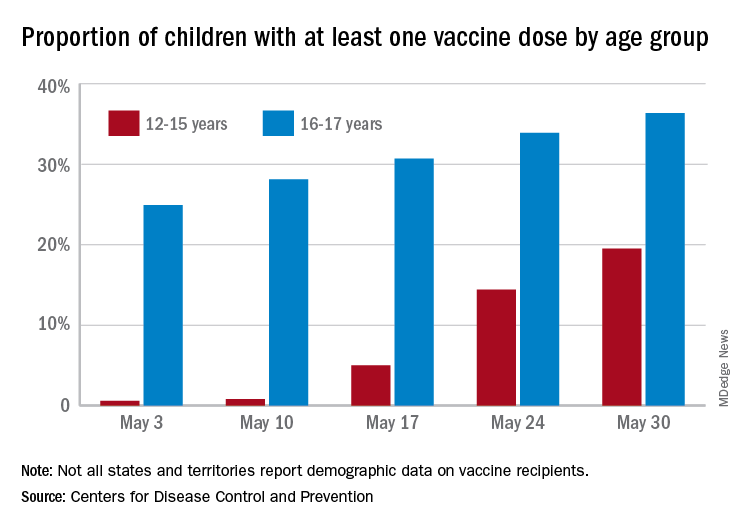

More children aged 12-15 years already have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine than have 16- and 17-year-olds, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

with those figures representing increases of 31.6% and 6.6% in the past week, respectively. Since the overall size of the 12-15 population is much larger, however, the proportion vaccinated is still smaller: 19.5% to 36.4%, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

A look at full vaccination status shows that only 0.7% of those aged 12-15 years have received both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of the single-shot variety, compared with 24% of those aged 16-17. For the country as a whole, 50.5% of all ages have received at least one dose and 40.7% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Children aged 12-15 represent the largest share of the U.S. population (23.4%) initiating vaccination in the 14 days ending May 30, while children aged 16-17 made up just 4.5% of those getting their first dose. The younger group’s later entry into the vaccination pool shows up again when looking at completion rates, though, representing just 0.4% of all Americans who reached full vaccination during that same 14-day period, compared with 4.6% of the older children, the CDC data show.

Not all states are reporting data such as age for vaccine recipients, the CDC noted, and there are other variables that affect data collection. “Demographic data ... might differ by populations prioritized within each state or jurisdiction’s vaccination phase. Every geographic area has a different racial and ethnic composition, and not all are in the same vaccination phase,” the CDC said.

More children aged 12-15 years already have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine than have 16- and 17-year-olds, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

with those figures representing increases of 31.6% and 6.6% in the past week, respectively. Since the overall size of the 12-15 population is much larger, however, the proportion vaccinated is still smaller: 19.5% to 36.4%, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

A look at full vaccination status shows that only 0.7% of those aged 12-15 years have received both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of the single-shot variety, compared with 24% of those aged 16-17. For the country as a whole, 50.5% of all ages have received at least one dose and 40.7% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Children aged 12-15 represent the largest share of the U.S. population (23.4%) initiating vaccination in the 14 days ending May 30, while children aged 16-17 made up just 4.5% of those getting their first dose. The younger group’s later entry into the vaccination pool shows up again when looking at completion rates, though, representing just 0.4% of all Americans who reached full vaccination during that same 14-day period, compared with 4.6% of the older children, the CDC data show.

Not all states are reporting data such as age for vaccine recipients, the CDC noted, and there are other variables that affect data collection. “Demographic data ... might differ by populations prioritized within each state or jurisdiction’s vaccination phase. Every geographic area has a different racial and ethnic composition, and not all are in the same vaccination phase,” the CDC said.

More children aged 12-15 years already have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine than have 16- and 17-year-olds, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

with those figures representing increases of 31.6% and 6.6% in the past week, respectively. Since the overall size of the 12-15 population is much larger, however, the proportion vaccinated is still smaller: 19.5% to 36.4%, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

A look at full vaccination status shows that only 0.7% of those aged 12-15 years have received both doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of the single-shot variety, compared with 24% of those aged 16-17. For the country as a whole, 50.5% of all ages have received at least one dose and 40.7% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Children aged 12-15 represent the largest share of the U.S. population (23.4%) initiating vaccination in the 14 days ending May 30, while children aged 16-17 made up just 4.5% of those getting their first dose. The younger group’s later entry into the vaccination pool shows up again when looking at completion rates, though, representing just 0.4% of all Americans who reached full vaccination during that same 14-day period, compared with 4.6% of the older children, the CDC data show.

Not all states are reporting data such as age for vaccine recipients, the CDC noted, and there are other variables that affect data collection. “Demographic data ... might differ by populations prioritized within each state or jurisdiction’s vaccination phase. Every geographic area has a different racial and ethnic composition, and not all are in the same vaccination phase,” the CDC said.

Sickle cell disease: Epidemiological change in bacterial infections

Among children with sickle cell disease who have not undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant, Salmonella is now the leading cause of invasive bacterial infection (IBI), according to a new retrospective study (BACT-SPRING) conducted in Europe. Streptococcus pneumoniae was the second most common source of infection, marking a shift from years past, when S. pneumoniae was the most common source. The epidemiology of IBI in Europe has been altered by adoption of prophylaxis and the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV13) in 2009.

Previous studies of IBI have been single center with small sample sizes, and few have been conducted since 2016, said Jean Gaschignard, MD, PhD, during his presentation of the study at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Dr. Gaschignard is head of pediatrics at Groupe Hospitalier Nord Essonne in Longjumeau, France.

The study produced some unexpected results. “We were surprised,” said Dr. Gaschignard, by results indicating that not all children aged under 10 years were undergoing prophylaxis. Instead, the figures were closer to 80% or 90%. Among children over 10, the rate of prophylaxis varies between countries. “Our study is a clue to discuss again the indications for the age limit for prophylaxis against pneumococcus,” said Dr. Gauschignard, during the question-and-answer session following his talk.

The data give clinicians an updated picture of the epidemiology in this population following introduction of the PCV13 vaccine. “It was very important to have new data on microbiology after this implementation,” said Marie Rohr, MD, who is a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at the University Hospitals of Geneva. Dr. Rohr moderated the session where the study was presented.

Dr. Rohr noted the shift from the dominant cause of IBI after the introduction of the PCV10/13 vaccine, from S. pneumoniae to Salmonella. The researchers also found a preponderance of bacteremia and osteoarticular infections. “The mortality and morbidity are still considerable despite infection preventive measures,” said Dr. Rohr.

The results should also prompt a second look at prevention strategies. “Even if the antibiotic prophylaxis is prescribed for a large [proportion of children with sickle cell disease] under 10 years old, the median age of invasive bacterial infection is 7 years old. This calls into question systematic antibiotic prophylaxis and case-control studies are needed to evaluate this and possibly modify antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations in the future,” said Dr. Rohr.

The BACT-SPRING study was conducted between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2019, using online data. It included 217 IBI episodes from 26 centers in five European countries. Just over half were from France, while about a quarter occurred in Spain. Other countries included Belgium, Portugal, and Great Britain. Participants were younger than 18 and had an IBI confirmed by bacterial culture or PCR from normally sterile fluid.

Thirty-eight episodes occurred in children who had undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and 179 in children who had not undergone HSCT. The presentation focused exclusively on the latter group.

Among episodes in children without HSCT, the mean age was 7. Forty-eight patients had a history of acute chest syndrome, 47 had a history of ICU admission, 29 had a history of IBI, and 27 had a history of acute splenic sequestration. Thirteen underwent a splenectomy. Almost half of children had none of these characteristics, while about one-fourth had two or more.

In the HSCT group, 141 children were on prophylaxis at the time of the infection; 74 were on hydroxyurea, and 36 were currently or previously on a transfusion program. Sixty-eight cases were primary bacteremia and 55 were osteoarticular. Other syndromes included pneumonia empyema (n = 18), and meningitis (n = 17), among others. In 44 cases, the isolated bacteria was Salmonella, followed by S. pneumoniae in 32 cases. Escherichia coli accounted for 22. Haemophilus influenza was identified in six episodes, and group A Streptococcus in three.

The study is the first large European epidemiologic study investigating IBI in children with sickle cell disease, and one of its strengths was the strict inclusion criteria. However, it was limited by its retrospective nature.

Dr. Gaschignard and Dr. Rohr have no relevant financial disclosures.

Among children with sickle cell disease who have not undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant, Salmonella is now the leading cause of invasive bacterial infection (IBI), according to a new retrospective study (BACT-SPRING) conducted in Europe. Streptococcus pneumoniae was the second most common source of infection, marking a shift from years past, when S. pneumoniae was the most common source. The epidemiology of IBI in Europe has been altered by adoption of prophylaxis and the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV13) in 2009.

Previous studies of IBI have been single center with small sample sizes, and few have been conducted since 2016, said Jean Gaschignard, MD, PhD, during his presentation of the study at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Dr. Gaschignard is head of pediatrics at Groupe Hospitalier Nord Essonne in Longjumeau, France.

The study produced some unexpected results. “We were surprised,” said Dr. Gaschignard, by results indicating that not all children aged under 10 years were undergoing prophylaxis. Instead, the figures were closer to 80% or 90%. Among children over 10, the rate of prophylaxis varies between countries. “Our study is a clue to discuss again the indications for the age limit for prophylaxis against pneumococcus,” said Dr. Gauschignard, during the question-and-answer session following his talk.

The data give clinicians an updated picture of the epidemiology in this population following introduction of the PCV13 vaccine. “It was very important to have new data on microbiology after this implementation,” said Marie Rohr, MD, who is a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at the University Hospitals of Geneva. Dr. Rohr moderated the session where the study was presented.

Dr. Rohr noted the shift from the dominant cause of IBI after the introduction of the PCV10/13 vaccine, from S. pneumoniae to Salmonella. The researchers also found a preponderance of bacteremia and osteoarticular infections. “The mortality and morbidity are still considerable despite infection preventive measures,” said Dr. Rohr.

The results should also prompt a second look at prevention strategies. “Even if the antibiotic prophylaxis is prescribed for a large [proportion of children with sickle cell disease] under 10 years old, the median age of invasive bacterial infection is 7 years old. This calls into question systematic antibiotic prophylaxis and case-control studies are needed to evaluate this and possibly modify antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations in the future,” said Dr. Rohr.

The BACT-SPRING study was conducted between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2019, using online data. It included 217 IBI episodes from 26 centers in five European countries. Just over half were from France, while about a quarter occurred in Spain. Other countries included Belgium, Portugal, and Great Britain. Participants were younger than 18 and had an IBI confirmed by bacterial culture or PCR from normally sterile fluid.

Thirty-eight episodes occurred in children who had undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and 179 in children who had not undergone HSCT. The presentation focused exclusively on the latter group.

Among episodes in children without HSCT, the mean age was 7. Forty-eight patients had a history of acute chest syndrome, 47 had a history of ICU admission, 29 had a history of IBI, and 27 had a history of acute splenic sequestration. Thirteen underwent a splenectomy. Almost half of children had none of these characteristics, while about one-fourth had two or more.

In the HSCT group, 141 children were on prophylaxis at the time of the infection; 74 were on hydroxyurea, and 36 were currently or previously on a transfusion program. Sixty-eight cases were primary bacteremia and 55 were osteoarticular. Other syndromes included pneumonia empyema (n = 18), and meningitis (n = 17), among others. In 44 cases, the isolated bacteria was Salmonella, followed by S. pneumoniae in 32 cases. Escherichia coli accounted for 22. Haemophilus influenza was identified in six episodes, and group A Streptococcus in three.

The study is the first large European epidemiologic study investigating IBI in children with sickle cell disease, and one of its strengths was the strict inclusion criteria. However, it was limited by its retrospective nature.

Dr. Gaschignard and Dr. Rohr have no relevant financial disclosures.

Among children with sickle cell disease who have not undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant, Salmonella is now the leading cause of invasive bacterial infection (IBI), according to a new retrospective study (BACT-SPRING) conducted in Europe. Streptococcus pneumoniae was the second most common source of infection, marking a shift from years past, when S. pneumoniae was the most common source. The epidemiology of IBI in Europe has been altered by adoption of prophylaxis and the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugated vaccine (PCV13) in 2009.

Previous studies of IBI have been single center with small sample sizes, and few have been conducted since 2016, said Jean Gaschignard, MD, PhD, during his presentation of the study at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Dr. Gaschignard is head of pediatrics at Groupe Hospitalier Nord Essonne in Longjumeau, France.

The study produced some unexpected results. “We were surprised,” said Dr. Gaschignard, by results indicating that not all children aged under 10 years were undergoing prophylaxis. Instead, the figures were closer to 80% or 90%. Among children over 10, the rate of prophylaxis varies between countries. “Our study is a clue to discuss again the indications for the age limit for prophylaxis against pneumococcus,” said Dr. Gauschignard, during the question-and-answer session following his talk.

The data give clinicians an updated picture of the epidemiology in this population following introduction of the PCV13 vaccine. “It was very important to have new data on microbiology after this implementation,” said Marie Rohr, MD, who is a fellow in pediatric infectious diseases at the University Hospitals of Geneva. Dr. Rohr moderated the session where the study was presented.

Dr. Rohr noted the shift from the dominant cause of IBI after the introduction of the PCV10/13 vaccine, from S. pneumoniae to Salmonella. The researchers also found a preponderance of bacteremia and osteoarticular infections. “The mortality and morbidity are still considerable despite infection preventive measures,” said Dr. Rohr.

The results should also prompt a second look at prevention strategies. “Even if the antibiotic prophylaxis is prescribed for a large [proportion of children with sickle cell disease] under 10 years old, the median age of invasive bacterial infection is 7 years old. This calls into question systematic antibiotic prophylaxis and case-control studies are needed to evaluate this and possibly modify antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations in the future,” said Dr. Rohr.

The BACT-SPRING study was conducted between Jan. 1, 2014, and Dec. 31, 2019, using online data. It included 217 IBI episodes from 26 centers in five European countries. Just over half were from France, while about a quarter occurred in Spain. Other countries included Belgium, Portugal, and Great Britain. Participants were younger than 18 and had an IBI confirmed by bacterial culture or PCR from normally sterile fluid.

Thirty-eight episodes occurred in children who had undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), and 179 in children who had not undergone HSCT. The presentation focused exclusively on the latter group.

Among episodes in children without HSCT, the mean age was 7. Forty-eight patients had a history of acute chest syndrome, 47 had a history of ICU admission, 29 had a history of IBI, and 27 had a history of acute splenic sequestration. Thirteen underwent a splenectomy. Almost half of children had none of these characteristics, while about one-fourth had two or more.

In the HSCT group, 141 children were on prophylaxis at the time of the infection; 74 were on hydroxyurea, and 36 were currently or previously on a transfusion program. Sixty-eight cases were primary bacteremia and 55 were osteoarticular. Other syndromes included pneumonia empyema (n = 18), and meningitis (n = 17), among others. In 44 cases, the isolated bacteria was Salmonella, followed by S. pneumoniae in 32 cases. Escherichia coli accounted for 22. Haemophilus influenza was identified in six episodes, and group A Streptococcus in three.

The study is the first large European epidemiologic study investigating IBI in children with sickle cell disease, and one of its strengths was the strict inclusion criteria. However, it was limited by its retrospective nature.

Dr. Gaschignard and Dr. Rohr have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ESPID 2021

Antiviral may improve hearing loss in congenital CMV

Infants with isolated sensorineural hearing loss as a result of congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) infection may benefit from treatment with valganciclovir, according to results from the CONCERT nonrandomized trial.

Subjects were found through the Newborn Hearing Screening program, using dried blood spot screening to confirm cCMV Infection. As a result of 6 weeks of therapy, more patients in the treatment group had improvements in hearing at age 20 months, and fewer had deterioration compared with untreated controls.

There is a general consensus that symptomatic cCMV should be treated with valganciclovir for 6 weeks or 6 months, but treatment of patients with only hearing loss is still under debate. The average age of participants was 8 weeks.

The study was presented by Pui Khi Chung, MD, a clinical microbiologist at the Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Out of 1,377 NHS-referred infants, 59 were diagnosed with cCMV (4.3%), and 35 were included in the study. Twenty-five patients received 6 weeks of valganciclovir, while 10 patients received placebo. The control group was expanded to 12 when two additional subjects were identified retrospectively and were successfully followed up at 20 months. Subjects in the treatment group were an average of 8 weeks old when treatment began. Both groups had similar neurodevelopmental outcomes at 20 months, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III) and the Child Development Inventory (CDI). There were no serious adverse events associated with treatment.

To measure efficacy, the researchers used a random intercept, random slope model that accounted for repeated measurements. The differences in slopes for analyses of the best ear were significantly different between the treatment and control groups (estimated difference in slopes, –0.93; P = .0071). Further analyses of total hearing found that improvement was more common in the treatment group, and deterioration/no change was more common in the nontreatment group (P = .044). In another analysis that excluded the most profoundly impaired ears (> 70 db hearing loss), none in the control group experienced improvement and almost half deteriorated. In the treatment group, most were unchanged and a small number improved, with almost none deteriorating (P = .006).

Asked whether the treatment has any effect on the most profoundly impaired ears, Dr. Chung said she had not yet completed that analysis, but the hypothesis is that the treatment is unlikely to lead to any improvement. “When you take out the severely impaired ears, you can see a greater [treatment] effect, so it does suggest that it doesn’t do anything for those ears,” Dr. Chung said during the Q&A session following her talk.

She was also asked why the treatment period was 6 weeks, rather than 6 months – a period of treatment that has shown a better effect on long-term hearing and developmental outcomes than 6 weeks of treatment in symptomatic patients. Dr. Chung replied that she wasn’t involved in the study design, but said that at her center, the 6-month regimen is not standard.

There were two key weaknesses in the study. One was the small sample size, and the other was its nonrandomized nature, which could have led to bias in the treated versus untreated group. “Although we don’t see any baseline differences between the groups, we have to be wary in analyses. Unfortunately, an RCT proved impossible in our setting. The CONCERT Trial started as randomized but this was amended to nonrandomized, as both parents and pediatricians had a clear preference for treatment,” said Dr. Chung.

The study could provide useful information about the timing of oral antiviral medication, according to Vana Spoulou, MD, who moderated the session where the research was presented. “The earliest you can give it is best, but sometimes it’s not easy to get them diagnosed immediately after birth. What they showed us is that even giving it so late, there was some improvement,” Dr. Spoulou said in an interview.

Dr. Spoulou isn’t ready to change practice based on the results, because she noted that some other studies have shown no benefit of treatment at 3 months. “But this was a hint that maybe even in these later diagnosed cases there could be some benefit,” she said.

Dr. Chung and Dr. Spoulou have no relevant financial disclosures.

Infants with isolated sensorineural hearing loss as a result of congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) infection may benefit from treatment with valganciclovir, according to results from the CONCERT nonrandomized trial.

Subjects were found through the Newborn Hearing Screening program, using dried blood spot screening to confirm cCMV Infection. As a result of 6 weeks of therapy, more patients in the treatment group had improvements in hearing at age 20 months, and fewer had deterioration compared with untreated controls.

There is a general consensus that symptomatic cCMV should be treated with valganciclovir for 6 weeks or 6 months, but treatment of patients with only hearing loss is still under debate. The average age of participants was 8 weeks.

The study was presented by Pui Khi Chung, MD, a clinical microbiologist at the Leiden University Medical Center, the Netherlands, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases, held virtually this year.

Out of 1,377 NHS-referred infants, 59 were diagnosed with cCMV (4.3%), and 35 were included in the study. Twenty-five patients received 6 weeks of valganciclovir, while 10 patients received placebo. The control group was expanded to 12 when two additional subjects were identified retrospectively and were successfully followed up at 20 months. Subjects in the treatment group were an average of 8 weeks old when treatment began. Both groups had similar neurodevelopmental outcomes at 20 months, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III) and the Child Development Inventory (CDI). There were no serious adverse events associated with treatment.

To measure efficacy, the researchers used a random intercept, random slope model that accounted for repeated measurements. The differences in slopes for analyses of the best ear were significantly different between the treatment and control groups (estimated difference in slopes, –0.93; P = .0071). Further analyses of total hearing found that improvement was more common in the treatment group, and deterioration/no change was more common in the nontreatment group (P = .044). In another analysis that excluded the most profoundly impaired ears (> 70 db hearing loss), none in the control group experienced improvement and almost half deteriorated. In the treatment group, most were unchanged and a small number improved, with almost none deteriorating (P = .006).

Asked whether the treatment has any effect on the most profoundly impaired ears, Dr. Chung said she had not yet completed that analysis, but the hypothesis is that the treatment is unlikely to lead to any improvement. “When you take out the severely impaired ears, you can see a greater [treatment] effect, so it does suggest that it doesn’t do anything for those ears,” Dr. Chung said during the Q&A session following her talk.

She was also asked why the treatment period was 6 weeks, rather than 6 months – a period of treatment that has shown a better effect on long-term hearing and developmental outcomes than 6 weeks of treatment in symptomatic patients. Dr. Chung replied that she wasn’t involved in the study design, but said that at her center, the 6-month regimen is not standard.

There were two key weaknesses in the study. One was the small sample size, and the other was its nonrandomized nature, which could have led to bias in the treated versus untreated group. “Although we don’t see any baseline differences between the groups, we have to be wary in analyses. Unfortunately, an RCT proved impossible in our setting. The CONCERT Trial started as randomized but this was amended to nonrandomized, as both parents and pediatricians had a clear preference for treatment,” said Dr. Chung.

The study could provide useful information about the timing of oral antiviral medication, according to Vana Spoulou, MD, who moderated the session where the research was presented. “The earliest you can give it is best, but sometimes it’s not easy to get them diagnosed immediately after birth. What they showed us is that even giving it so late, there was some improvement,” Dr. Spoulou said in an interview.