User login

It’s time to rethink your approach to C diff infection

CASE 1

Beth O, a 63-year-old woman, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of diarrhea (6 very loose, watery stools per day) and lower abdominal pain. The patient denies any vomiting, sick contacts, or recent travel. Past medical history includes varicose veins. Her only active medication is loperamide, as needed, for the past 2 weeks. Ms. O also recently completed a 10-day course of clindamycin for an infected laceration on her finger.

Ms. O’s laboratory values are unremarkable, with a normal white blood cell (WBC) count and serum creatinine (SCr) level. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) reveals some abnormal bowel dilatation and a slight increase in colon wall thickness. There is a high suspicion for Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) infection (CDI), and stool sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing comes back positive for C difficile toxin B. It is revealed to be a strain other than the BI/NAP1/027 epidemic strain (which has a higher mortality rate).

How should this patient be treated?

CASE 2

Sixty-eight-year-old Barbara Z presents to the ED from her skilled nursing facility with persistent diarrhea and abdominal cramping. She was diagnosed with CDI about 2 months ago and reports that her symptoms resolved within 4 to 5 days after starting a 14-day course of oral metronidazole.

Her past medical history is notable for multiple myeloma with bone metastasis, for which she is actively undergoing chemotherapy treatment. She also has chronic kidney disease (baseline SCr, 2.2 mg/dL), hypertension, and anemia of chronic disease. The patient’s medications include amlodipine and cholecalciferol. Her chemotherapy regimen consists of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone. CT of the abdomen shows diffuse colon wall thickening with surrounding inflammatory stranding—concerning for pancolitis. There is no evidence of toxic megacolon or ileus.

Ms. Z’s laboratory values are notable for a WBC count of 15,900 cells/mL and an SCr of 4.1 mg/dL. She is started on oral levofloxacin and metronidazole due to concern for an intra-abdominal infection. PCR testing is positive for C difficile, and an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for C difficile toxin is positive.

What factors put Ms. Z at risk for C difficile, and how should she be treated?

Continue to: C difficile is one of the most...

C difficile is one of the most commonly reported pathogens in health care–associated infections and affects almost 1% of all hospitalized patients in the United States each year.1 From 2001 to 2010, the incidence of CDI doubled in patients discharged from hospitals,2 with an estimated cost of more than $5 billion annually.3 Furthermore, rates of community-associated CDI continue to increase and account for about 40% of cases.4

After colonization in the intestine, C difficile releases 2 toxins (TcdA and TcdB) that cause colitis.5 Patients may present with mild diarrhea that can progress to abdominal pain, cramping, fever, and leukocytosis. Fulminant CDI can lead to the formation of pseudomembranes in the colon, toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, shock, and death.2

Beginning in the early 2000s, hospitals reported increases in severe cases of CDI.6 A specific strain known as BI/NAP1/027 was identified and characterized by fluoroquinolone resistance, increased spore formation, and a higher mortality rate.6

Further complicating matters … Recurrent CDI occurs in up to 10% to 30% of patients,7 typically within 14 to 45 days of completion of antibiotic pharmacotherapy for CDI.8 Recurrence is characterized by new-onset diarrhea or abdominal symptoms after completion of treatment for CDI.5

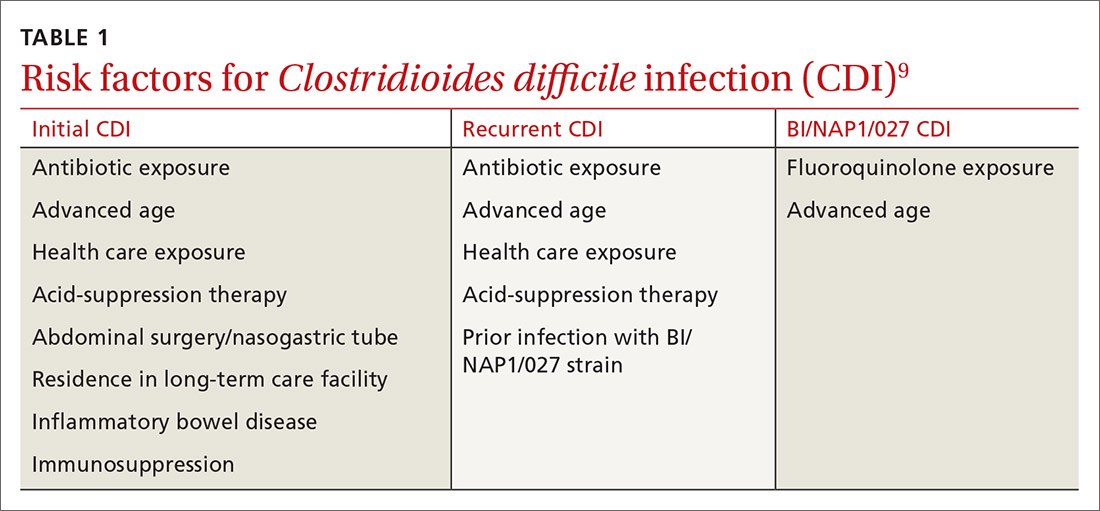

It typically begins with an antibiotic

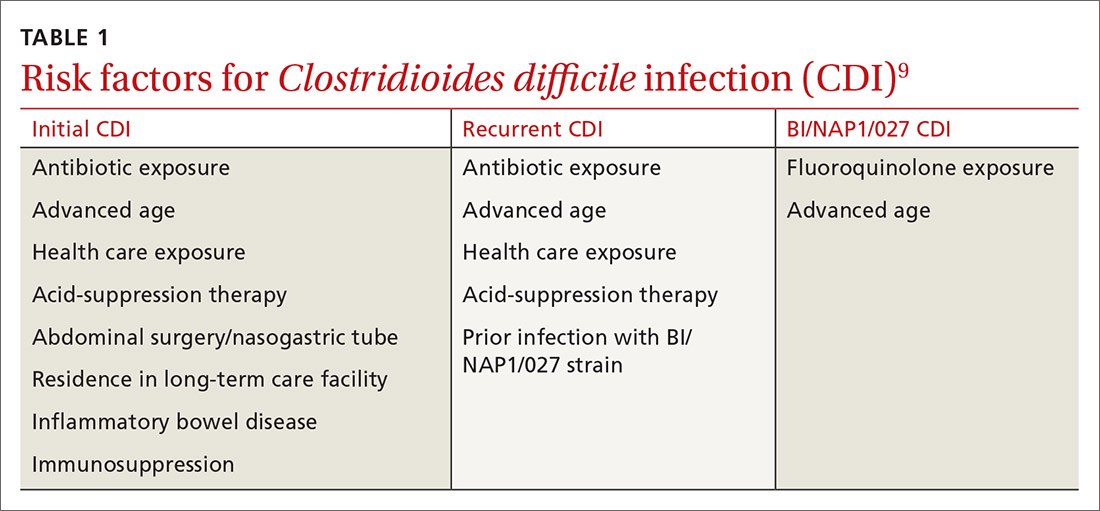

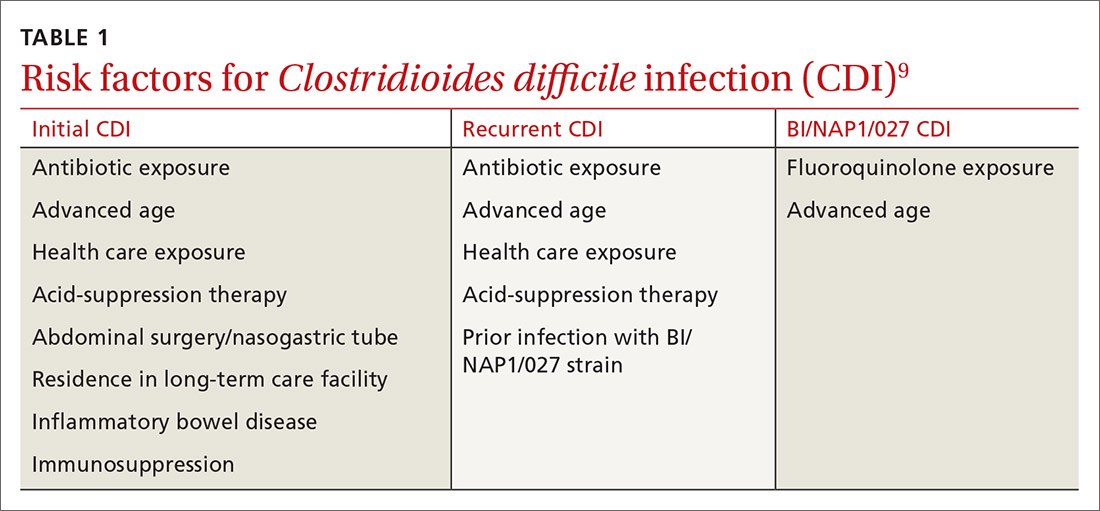

Risk factors for CDI are listed in TABLE 1.9 The most important modifiable risk factor for initial and recurrent CDI is recent use of antibiotics.10 Most antibiotics can disrupt normal intestinal flora, causing colonization of C difficile, but the strongest association seems to be with third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and clindamycin.11 The risk for CDI occurs during antibiotic treatment, as well as up to 3 months after completion of antibiotic therapy.7 Exposure to multiple antibiotics and extended duration of antibacterial therapy can greatly increase the risk for CDI, so antimicrobial stewardship is key.11

Continue to: Continuing antibiotics while attempting...

Continuing antibiotics while attempting to treat CDI reduces the patient’s clinical response to CDI treatment, which can lead to recurrence.12 The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines include a strong recommendation to discontinue concurrent antibiotics as soon as possible in these scenarios.11

Acid-suppression therapy has also been associated with CDI. The mechanism is thought to be an interruption in the protection provided by stomach acid, and use over time may reduce the diversity of flora within the gut microbiome.13 The data demonstrating an association between acid-suppression therapy and CDI is conflicting, which may be a result of confounding factors such as the severity of CDI illness and diarrhea induced by use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).4 IDSA guidelines do not provide a recommendation regarding discontinuation of PPI therapy for the prevention of CDI, although inappropriate PPI therapy should always be discontinued.11

Advanced age is an important nonmodifiable risk factor for CDI. Older adults who live in long-term care facilities are at a higher risk for CDI, and these facilities have colonization rates as high as 50%.12

Community-associated risk. In an analysis of community-associated cases of CDI, 82% of patients reported some sort of health care exposure (ranging from physician office visit to surgery admission), 64% reported the receipt of antimicrobial therapy, and 31% reported the use of PPIs.14 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may also put community dwellers at higher risk for CDI and its complications.15

CASES 1 & 2

Both CASE patients have risk factors for CDI. Ms. O (CASE 1) is likely at risk for CDI after completion of her recent course of clindamycin. Ms. Z (CASE 2) has several risk factors for recurrent CDI, including advanced age (≥ 65 years), residence in a long-term care facility, prior antibiotic exposure, and immunodeficiency because of chemotherapy/steroid use.

Continue to: Diagnosis

Diagnosis: Who and how to test

CDI should be both a clinical and laboratory-confirmed diagnosis. Patients should be tested for CDI if they have 3 or more episodes of unexplainable, new-onset unformed stools in 24 hours.11 Asymptomatic patients should not be tested to avoid unnecessary testing and treatment of those who are colonized but not infected.11 It is not recommended to routinely test patients who have taken laxatives within the previous 48 hours.11

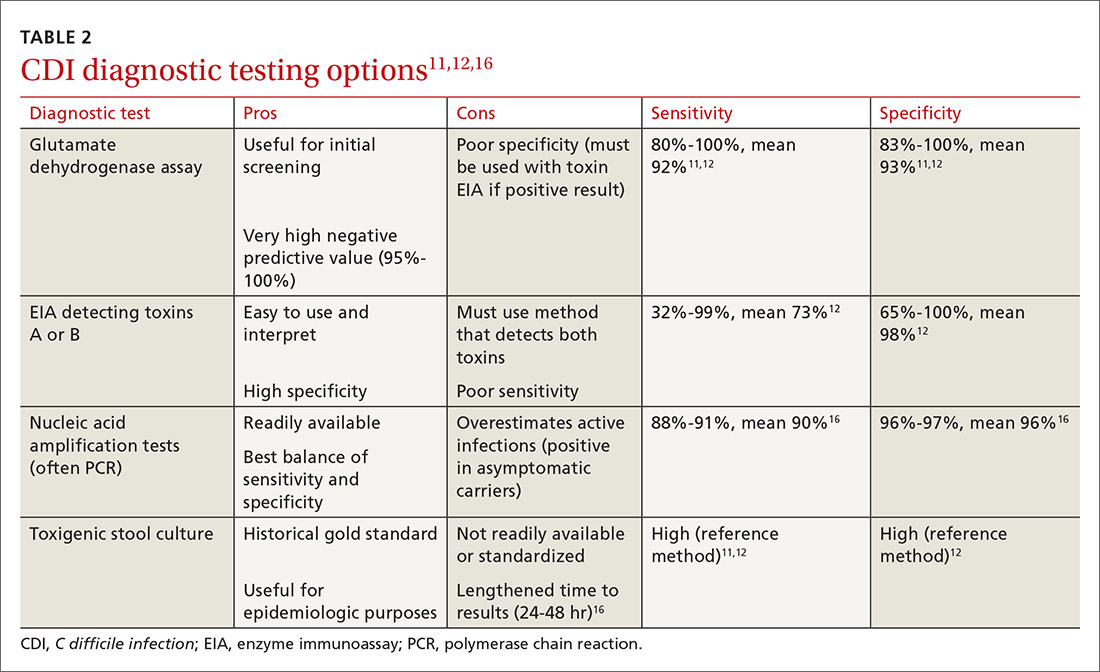

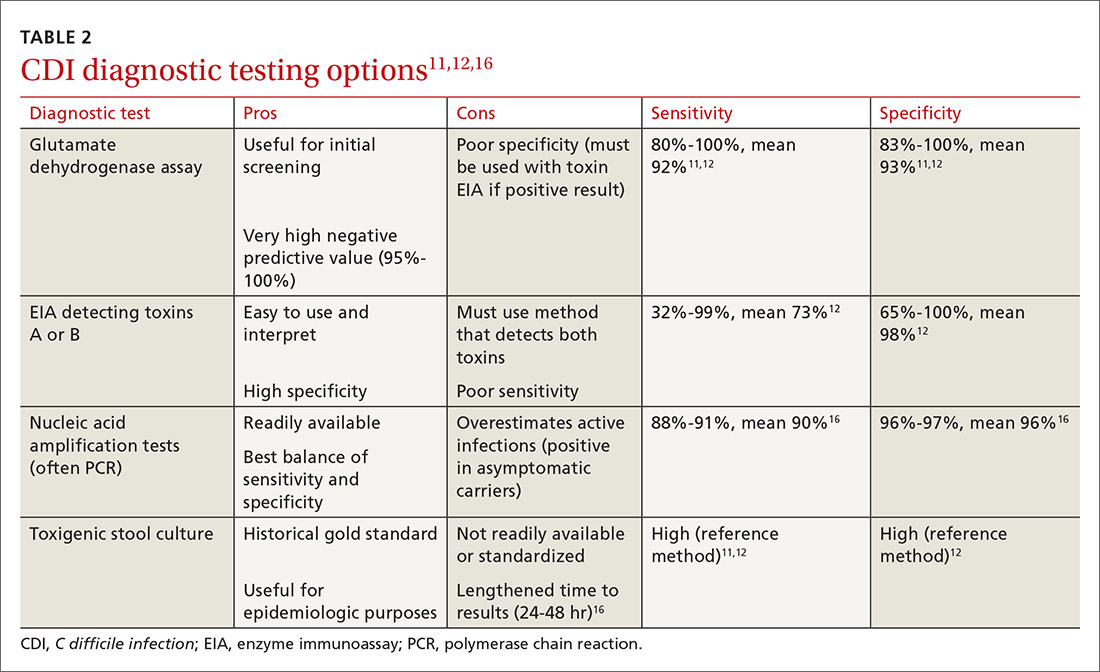

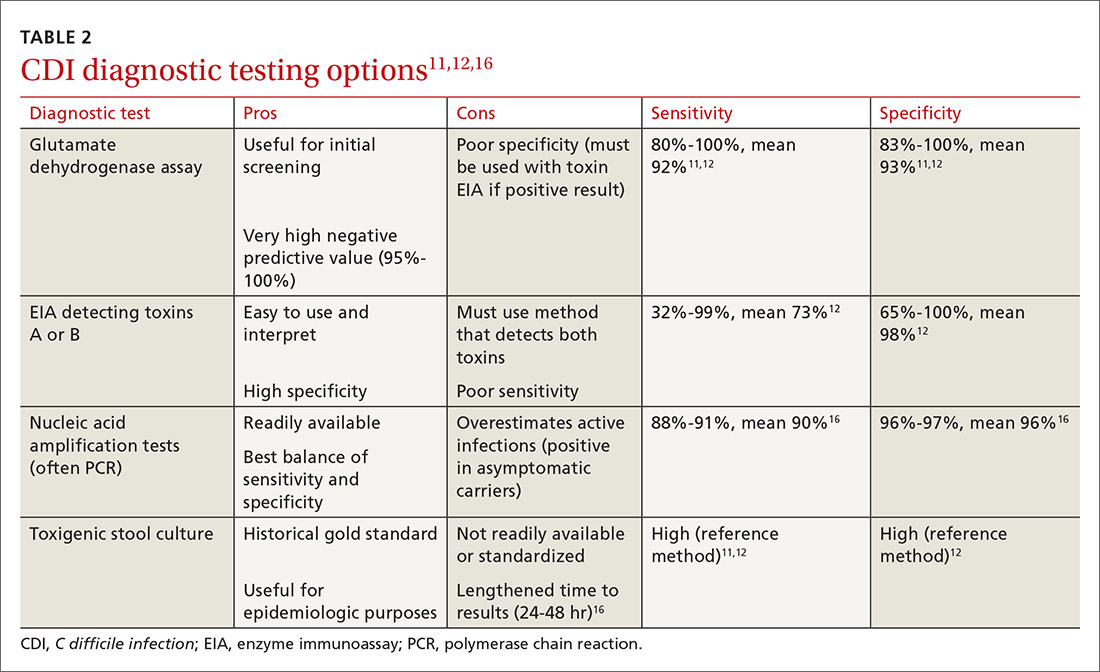

There are several stool-based laboratory test options for the diagnosis of CDI (TABLE 211,12,16) but no definitive recommendation for all institutions.11 Many institutions have now implemented PCR testing for the diagnosis of CDI. However, while the benefits of this test include reduced need for repeat testing and possible identification of carriers, it’s estimated that reports of CDI increase more than 50% when an institution switches to PCR testing.1 Nonetheless, a one-step, highly sensitive test such as PCR may be used if strict criteria are implemented and followed.

The increase in positive PCR tests has prompted evaluation of using another test in addition to or in place of PCR. Multistep testing options include a glutamate dehydrogenase assay (GDH) with a toxin EIA, GDH with a toxin EIA and final decision via PCR, or PCR with toxin EIA.11 Use of a multistep diagnostic algorithm may increase overall specificity up to 100%, which may improve determination of asymptomatic colonization vs active infection.16 (Patients who have negative toxin results with positive PCR likely have colonization but not infection and often do not require treatment.) IDSA guidelines recommend that the stool toxin test should be part of a multistep algorithm for diagnosis, rather than PCR alone, if strict criteria are not implemented for stool test submission.11

There is no need to perform a test of cure after a patient has been treated for CDI, and no repeat testing should be performed within 7 days of the previous test.11 After successful treatment, patients will continue to shed spores and test positively via PCR for weeks to months.11 When patients have a positive PCR test, there are several important infection control efforts that institutions should consider; see “IDSA weighs in on measures to combat C difficile.”

SIDEBAR

IDSA weighs in on measures to combat C difficile

The spores produced by Clostridioides difficile can survive for 5 months or longer on dry surfaces because of resistance to heat, acid, antibiotics, and many cleaning products.38 Unfortunately, spores transmitted from health care workers and the environment are the most likely cause of infection spreading in health care institutions. To prevent transmission of C difficile infection (CDI) throughout institutions, appropriate infection control measures are necessary.

Clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend that patients with CDI be isolated to a private room with a dedicated toilet. Health care staff should wear gloves and gowns when entering the room of, or taking care of, a patient with CDI. For patients who are suspected of having CDI, contact precautions should be implemented while awaiting test results. When the diagnosis is confirmed, contact precautions should remain in place for at least 48 hours after resolution of diarrhea but may be continued until discharge.11

Practicing good hand hygiene is essential, especially in institutions with high rates of CDI or if fecal contamination is likely.11 Hand hygiene with soap and water is preferred, due to evidence of a higher spore removal rate, but alcohol-based alternatives may be used if necessary.11 In institutions with high rates of CDI, terminal (post-discharge) cleaning of rooms with a sporicidal agent should be considered.11

Asymptomatic carriers are also a concern for transmission of CDI in institutional settings. Screening and isolating patients who are carriers may prevent transmission, and some institutions have implemented this process to reduce the risk for CDI that originates in a health care facility.39 The IDSA guidelines do not make a recommendation regarding screening or isolation of asymptomatic carriers, so the decision is institution specific.11 These guidelines also recommend that patients presenting with similar infectious organisms be housed in the same room, if needed, to avoid cross-contamination to others or additional surfaces.11

For pediatric patients, testing recommendations vary by age. Testing is not generally recommended for neonates or infants ≤ 2 years of age with diarrhea because of the prevalence of colonization with C difficile.11 For children older than 2 years, testing for CDI is only recommended in the setting of prolonged or worsening diarrhea and if the patient has risk factors such as IBD, immunocompromised state, health care exposure, or recent antibiotic use.11 In addition, testing in this population should only be considered once other infectious and noninfectious causes of diarrhea have been excluded.11

Continue to: First-line treatment? Drug of choice has changed

First-line treatment? Drug of choice has changed

In 2018, the IDSA published new treatment guidelines that provide important updates from the 2010 guidelines.11 Chief among these was the elimination of metronidazole as a first-line therapy. Vancomycin or fidaxomicin are now recommended as first-line treatment options because of superior eradication of C difficile when compared with metronidazole.11 In the opinion of the authors, vancomycin should be considered the drug of choice because of cost. (See “The case for vancomycin.”)

SIDEBAR

The case for vancomycin

The majority of studies conducted prior to publication of the 2010 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines described numerically worse eradication rates of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) with metronidazole compared with vancomycin for all severities of infection, but statistical significance was not achieved. These studies also showed a nonsignificant increase in CDI recurrence with metronidazole.17,40,41

A 2005 systematic review demonstrated increased treatment failure rates with metronidazole.42 The rates of metronidazole discontinuation and transition to alternative options more than doubled in 2003-2004, to 25.7% of patients compared with 9.6% in earlier years.42 Metronidazole efficacy was further questioned in a prospective observational study conducted in 2005, in which only 50% of patients were cured after an initial course of treatment, while 28% had recurrence within 90 days.43

Vancomycin was found to be the superior treatment option to metronidazole and tolevamer in a 2014 randomized controlled trial.18 This study also demonstrated that vancomycin was the superior therapy when comparing treatment-naïve vs experienced patients and severity of CDI.18 A 2017 retrospective cohort study demonstrated decreased 30-day all-cause mortality for patients taking vancomycin vs metronidazole (adjusted relative risk = 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.98), although it should be noted that this difference was driven by those with severe CDI, and there was no statistically significant difference in mortality for patients with mild-to-moderate CDI.44

The results of these studies led to the recommendation of vancomycin over metronidazole as first-line pharmacotherapy for CDI in practice, despite the historical perspective that overutilization of oral vancomycin could potentially increase rates of vancomycinresistant Enterococcus.11

Metronidazole should only be used in the treatment of CDI as a lastresort medication because of cost or insurance coverage. Although the price of oral vancomycin is higher, favorable patient outcomes are substantially greater, and recent analyses have shown that vancomycin is actually more cost-effective than metronidazole as a result.24 Adverse effects for metronidazole include neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal discomfort, and disulfiram-like reaction.

Vancomycin does not harbor as many adverse effects because of extremely low systemic absorption when taken orally, but patients may experience gastrointestinal discomfort.45 While systemic exposure with oral administration of vancomycin is very low (< 1%), there have been case reports of nephrotoxicity and “red man syndrome” that are more typically seen with intravenous vancomycin.44

Given the low rate of systemic exposure, routine monitoring of renal function and serum drug levels is not usually necessary during oral vancomycin therapy. However, it may be appropriate to monitor renal function and serum levels of vancomycin in patients who have renal failure, have altered intestinal integrity, are age ≥ 65 years, or are receiving high doses of vancomycin.46

10-day vs 14-day treatment of CDI. Most studies for the treatment of CDI have used a 10-day regimen rather than increasing the duration to a 14-day regimen, and nearly all studies conducted have displayed high rates of symptom resolution at the end of 10 days of treatment.17,18 Thus, treatment duration beyond 10 days should only be considered for patients who continue to have symptoms or complications with CDI on Day 10 of treatment.

First recurrence. Metronidazole is no longer the recommended treatment for first recurrence of CDI treated initially with metronidazole; instead, a 10-day course of vancomycin should be used.11 For recurrent cases in patients initially treated with vancomycin, a tapered and pulsed regimen of vancomycin is recommended11:

- vancomycin PO 125 mg four times daily for 10 to 14 days followed by

- vancomycin PO 125 mg twice daily for 7 days, then

- vancomycin PO 125 mg once daily for 7 days, then

- vancomycin PO 125 mg every 2 to 3 days for 2 to 8 weeks.

Pediatric patients. The IDSA guidelines recommend use of metronidazole or vancomycin to treat an initial case or first recurrence of mild-to-moderate CDI in this population.11 Due to a lack of quality evidence, the drug of choice for initial treatment is inconclusive, so patient-specific factors and cost should be considered when choosing an agent.11 If not cost prohibitive, vancomycin should be the drug of choice for most cases of pediatric CDI, and for severe cases or multiple recurrences of CDI, vancomycin is clearly the drug of choice.

Recommended agents: A closer look

Oral vancomycin products. Vancocin, a capsule, and Firvanq, an oral solution, are 2 vancomycin products currently on the market for CDI. Although the capsules are a readily available treatment option, the cost of the full course of treatment can be a barrier for patients without insurance, or with high copays or deductibles (brand name, $4000; generic, $1252).19

Continue to: Historically, in an effort to keep costs down...

Historically, in an effort to keep costs down, an oral solution was often inexpensively compounded at hospitals or pharmacies.20

Fidaxomicin, an oral macrocyclic antibiotic with minimal systemic absorption, was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for CDI in 2011.21 The IDSA guidelines recommend fidaxomicin for initial, and recurrent, cases of CDI as an alternative to vancomycin.11 This recommendation is based on 2 randomized double-blind trials comparing fidaxomicin to standard-dose oral vancomycin for initial or recurrent CDI.21,22

Pooled data from these 2 similar studies found that fidaxomicin was noninferior (10% noninferiority margin) to vancomycin for the primary outcome of clinical cure.23 Fidaxomicin was shown to be superior to vancomycin regarding rate of CDI recurrence (relative risk [RR] = 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43-0.87). These results were similar regardless of whether the CDI was an initial or recurrent case.23

Given the lack of systemic absorption, fidaxomicin is generally very well tolerated. The largest downside to fidaxomicin is its cost, which can be nearly $5000 for a standard 10-day course (vs as little as $165 for oral vancomycin).19 As a result, oral vancomycin solution is likely the most cost-effective therapy for initial cases of CDI.24 In patients with poor medication adherence, fidaxomicin offers the advantage of less-frequent dosing (twice daily vs 4 times daily with vancomycin).

For cases of recurrent CDI, when treatment failure occurred with vancomycin, fidaxomicin should be considered as an efficacious alternative. If fidaxomicin is used, it is advisable to verify coverage with the patient’s insurance plan, since prior authorization is frequently required.

Continue to: When meds fail, consider a fecal microbiota transplant

When meds fail, consider a fecal microbiota transplant

Another important change in the IDSA guidelines for CDI management is the strong recommendation for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with multiple recurrences of CDI for whom appropriate antibiotic treatment courses have failed.11,25 The goal of FMT is to “normalize” an abnormal gut microbiome by transplanting donor stool into a recipient.26

FMT has been shown to be highly effective in 5 randomized clinical trials conducted since 2013, with CDI cure rates between 85% and 94%.11 This rate of cure is particularly impressive given that the studies only included patients with refractory CDI.

Patients with recurrent CDI who may be candidates for FMT should be referred to a center or specialist with experience in FMT. These transplants can be expensive because of the screening process involved in obtaining donor samples. (Historically, a single FMT has cost $3000-$5000, and it is seldom covered by insurance.27) The emergence of universal stool banks offers a streamlined solution to this process.26

Fresh or frozen stool is considered equally effective in treating refractory CDI.26 Oral capsule and freeze-dried stool formulations have been studied, but their use is considered investigational at this time.26

Delivery via colonoscopy to the right colon is the preferred route of infusion; however, delivery via enema or nasogastric, nasojejunal, or nasoduodenal infusion can be considered as well.26

Continue to: In preparing for stool transplantation...

In preparing for stool transplantation, patients should be treated with standard doses of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for 3 days before the procedure to suppress intestinal C difficile, and the last dose of antibiotics should be given 12 to 48 hours before the procedure.26 Bowel lavage with polyethylene glycol is recommended, regardless of whether stool is delivered via colonoscopy or upper GI route.

Short-term adverse events associated with FMT appear to be minimal; data is lacking for long-term safety outcomes.28 While only recommended currently for cases of recurrent CDI, there is promising data emerging for use of FMT for severe cases, even without recurrence.29

The role of probiotics remains unclear

Probiotics have been explored in numerous trials to determine if they are effective in preventing CDI in patients who have been prescribed antibiotics.11 While no randomized trials have conclusively shown benefit, several meta-analyses have shown that the use of probiotics may result in a 60% to 65% relative risk reduction in CDI incidence.30,31

One proviso to these meta-analyses is that the incorporated studies have typically included patients at very high risk for CDI, and subanalyses have only found a reduction in CDI incidence when patients are at a very high baseline risk. In addition, there are many differences in probiotic types, formulations, treatment durations, and follow-up. As a result, the IDSA guidelines state that there is “insufficient data at this time” to recommend routine administration of probiotics for either primary or secondary CDI prophylaxis.11

Due to insufficient high-quality data, the IDSA guidelines do not provide a recommendation regarding use as an adjunct treatment option for acute CDI.11 Probiotics should not be routinely used to prevent CDI; however, they may provide benefit if reserved for patients at the highest risk for CDI (eg, history of CDI, prolonged use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, high local incidence).

Continue to: What about surgical intervention?

What about surgical intervention?

In severe cases of CDI, surgery may be necessary and can reduce mortality.32 The surgical procedure with the strongest recommendation in the IDSA guidelines is the subtotal colectomy, though the diverting loop ileostomy is an alternative option.11 Patients who may benefit from surgery include those with a WBC count ≥ 25,000; lactate > 5 mmol/L11; altered mental status; megacolon; perforation of the colon; acute abdomen on physical examination; or septic shock due to CDI.33 Although surgery can be beneficial, the mortality rate remains high for those with CDI who undergo colectomy.33

Reserve bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrence

Bezlotoxumab, a human monoclonal immunoglobulin GI/kappa antibody, was approved by the FDA in 2016 for the prevention of recurrent CDI. Its mechanism of action is to bind and neutralize C difficile toxin B. It was approved as a single infusion for adults who are receiving active antibiotic therapy for CDI and are considered to be at high risk for recurrence.34

This approval was based on 2 trials of more than 2500 patients, in which participants received bezlotoxumab or placebo while receiving treatment for primary or recurrent CDI. The primary outcome of these studies was recurrent infection within 12 weeks after infusion, which was significantly lower for bezlotoxumab in both studies: 17% vs 28% (P < 0.001) in one trial and 16% vs 26% (P < 0.001) in the other trial.35

Bezlotoxumab should only be used as an adjunct to prevent recurrence.32 There is no recommendation for or against bezlotoxumab in the IDSA guidelines because of the recent date of the drug’s approval. Its frequency of use will likely depend on the number of patients who meet criteria as high risk for recurrence and its estimated cost of $4560 per dose.34,36

CASES

CASE 1: In light of Ms. O’s recent completion of a course of clindamycin and unremarkable lab work, she should be treated for mild-to-moderate CDI. She has no comorbid conditions to warrant fidaxomicin, and thus vancomycin (capsules or oral solution) would be the best treatment option. Ms. O is started on vancomycin PO 125 mg qid for 10 days. She is also advised to discontinue loperamide as soon as possible, based on poor outcomes data seen with the use of antimotility agents in CDI.37

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2: Ms. Z has several risk factors for recurrent CDI and has an elevated WBC count and SCr level (WBC ≥ 15,000 and SCr > 1.5 mg/dL). Thus, she is classified as having severe, recurrent CDI. Oral levofloxacin and metronidazole should be discontinued, because they increase the risk for treatment failure and development of more virulent CDI strains, such as BI/NAP1/027. Since Ms. Z used metronidazole for treatment of her initial CDI, vancomycin or fidaxomicin should be used at this time. Either vancomycin PO 125 mg qid for 10 days or fidaxomicin 200 mg bid for 10 days would be an appropriate regimen; however, because of cost and unknown insurance coverage, vancomycin is the most appropriate regimen.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy Vandiver, PharmD, BCPS, University of Wyoming School of Pharmacy, Saint Joseph Family Medicine Residency, 1000 E. University Avenue, Dept 3375, Laramie, WY 82071; [email protected]

1. Polage CR, Gyorke CE, Kennedy MA, et al. Overdiagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in the molecular test era. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1792-1801.

2. Reveles KR, Lee GC, Boyd NK, et al. The rise in Clostridium difficile infection incidence among hospitalized adults in the United States: 2001-2010. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:1028-1032.

3. Dubberke ER, Olsen MA. Burden of Clostridium difficile on the healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S88-S92.

4. Tariq R, Singh S, Gupta A, et al. Association of gastric acid suppression with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:784-791.

5. Kachrimanidou M, Malisiovas N. Clostridium difficile infection: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:178-187.

6. O’Connor JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic BI/NAP1/027 strain. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1913-1924.

7. Kelly CP. A 76-year-old man with recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: review of C difficile infection. JAMA. 2009;301:954-962.

8. Cornely OA, Miller MA, Louie TJ, et al. Treatment of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: fidaxomicin versus vancomycin. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 2):S154-S161.

9. Napolitano LM, Edmiston CE Jr. Clostridium difficile disease: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment update. Surgery 2017;162:325-348.

10. Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, et al. Risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:452-460.

11. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:e1-e48.

12. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498; quiz 499.

13. Seto CT, Jeraldo P, Orenstein R, et al. Prolonged use of a proton pump inhibitor reduces microbial diversity: implications for Clostridium difficile susceptibility. Microbiome. 2014;2:42.

14. Chitnis AS, Holzbauer SM, Belflower RM, et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1359-1367.

15. Negrón ME, Rezaie A, Barkema HW, et al. Ulcerative colitis patients with Clostridium difficile are at increased risk of death, colectomy, and postoperative complications: a population-based inception cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:691-704.

16. Bagdasarian N, Rao K, Malani PN. Diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:398-408.

17. Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, et al. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:302-307.

18. Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:345-354.

19. Vancomycin: product details. Redbook Online. www.micromedexsolutions.com. Published 2018. Accessed June 13, 2020.

20. Mergenhagen KA, Wojciechowski AL, Paladino JA. A review of the economics of treating Clostridium difficile infection. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:639-650.

21. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:422-431.

22. Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:281-289.

23. Crook DW, Walker AS, Kean Y, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection: meta-analysis of pivotal randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55 suppl 2:S93-103.

24. Ford DC, Schroeder MC, Ince D, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of initial treatment strategies for mild-to-moderate Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75:1110-1121.

25. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-455.

26. Panchal P, Budree S, Scheeler A, et al. Scaling safe access to fecal microbiota transplantation: past, present, and future. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20:14.

27. Arbel LT, Hsu E, McNally K. Cost-effectiveness of fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9:e1599.

28. Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2017;66:569-580.

29. Hocquart M, Lagier JC, Cassir N, et al. Early fecal microbiota transplantation improves survival in severe Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:645-650.

30. Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD006095.

31. Johnston BC, Lytvyn L, Lo CK, et al. Microbial preparations (probiotics) for the prevention of Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 6,851 participants. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018:1-11.

32. Stewart DB, Hollenbeak CS, Wilson MZ. Is colectomy for fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis life saving? A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:798-804.

33. Julien M, Wild JL, Blansfield J, et al. Severe complicated Clostridium difficile infection: can the UPMC proposed scoring system predict the need for surgery? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:221-228.

34. Merck & Co, Inc. Sharp M. ZinplavaTM (bezlotoxumab [package insert] US Food and Drug Administration Web site. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/761046s000lbl.pdf. Revised October 2016. Accessed May 29, 2020.

35. Wilcox MH, Gerding DN, Poxton IR, et al. Bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:305-317.

36. Chahine EB, Cho JC, Worley MV. Bezlotoxumab for the Prevention of Clostridium difficile recurrence. Consult Pharm. 2018;33:89-97.

37. Koo HL, Koo DC, Musher DM, et al. Antimotility agents for the treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:598-605.

38. Rupnik M, Wilcox MH, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection: new developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:526-536.

39. Longtin Y, Paquet-Bolduc B, Gilca R, et al. Effect of detecting and isolating Clostridium difficile carriers at hospital admission on the incidence of C difficile infections: a quasi-experimental controlled study. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:796-804.

40. Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM, et al. Prospective randomised trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhoea and colitis. Lancet. 1983;2:1043-1046.

41. Wenisch C, Parschalk B, Hasenhündl M, et al. Comparison of vancomycin, teicoplanin, metronidazole, and fusidic acid for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:813-818.

42. Pepin J, Alary ME, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1591-1597.

43. Musher DM, Aslam S, Logan N, et al. Relatively poor outcome after treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis with metronidazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1586-1590.

44. Stevens VW, Nelson RE, Schwab-Daugherty EM, et al. Comparative effectiveness of vancomycin and metronidazole for the prevention of recurrence and death in patients with Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:546-553.

45. CutisPharma. FirvanqTM (vancomycin hydrochloride) for oral solution [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/208910s000lbl.pdf. Revised January 2018. Accessed May 29, 2020.

46.

CASE 1

Beth O, a 63-year-old woman, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of diarrhea (6 very loose, watery stools per day) and lower abdominal pain. The patient denies any vomiting, sick contacts, or recent travel. Past medical history includes varicose veins. Her only active medication is loperamide, as needed, for the past 2 weeks. Ms. O also recently completed a 10-day course of clindamycin for an infected laceration on her finger.

Ms. O’s laboratory values are unremarkable, with a normal white blood cell (WBC) count and serum creatinine (SCr) level. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) reveals some abnormal bowel dilatation and a slight increase in colon wall thickness. There is a high suspicion for Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) infection (CDI), and stool sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing comes back positive for C difficile toxin B. It is revealed to be a strain other than the BI/NAP1/027 epidemic strain (which has a higher mortality rate).

How should this patient be treated?

CASE 2

Sixty-eight-year-old Barbara Z presents to the ED from her skilled nursing facility with persistent diarrhea and abdominal cramping. She was diagnosed with CDI about 2 months ago and reports that her symptoms resolved within 4 to 5 days after starting a 14-day course of oral metronidazole.

Her past medical history is notable for multiple myeloma with bone metastasis, for which she is actively undergoing chemotherapy treatment. She also has chronic kidney disease (baseline SCr, 2.2 mg/dL), hypertension, and anemia of chronic disease. The patient’s medications include amlodipine and cholecalciferol. Her chemotherapy regimen consists of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone. CT of the abdomen shows diffuse colon wall thickening with surrounding inflammatory stranding—concerning for pancolitis. There is no evidence of toxic megacolon or ileus.

Ms. Z’s laboratory values are notable for a WBC count of 15,900 cells/mL and an SCr of 4.1 mg/dL. She is started on oral levofloxacin and metronidazole due to concern for an intra-abdominal infection. PCR testing is positive for C difficile, and an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for C difficile toxin is positive.

What factors put Ms. Z at risk for C difficile, and how should she be treated?

Continue to: C difficile is one of the most...

C difficile is one of the most commonly reported pathogens in health care–associated infections and affects almost 1% of all hospitalized patients in the United States each year.1 From 2001 to 2010, the incidence of CDI doubled in patients discharged from hospitals,2 with an estimated cost of more than $5 billion annually.3 Furthermore, rates of community-associated CDI continue to increase and account for about 40% of cases.4

After colonization in the intestine, C difficile releases 2 toxins (TcdA and TcdB) that cause colitis.5 Patients may present with mild diarrhea that can progress to abdominal pain, cramping, fever, and leukocytosis. Fulminant CDI can lead to the formation of pseudomembranes in the colon, toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, shock, and death.2

Beginning in the early 2000s, hospitals reported increases in severe cases of CDI.6 A specific strain known as BI/NAP1/027 was identified and characterized by fluoroquinolone resistance, increased spore formation, and a higher mortality rate.6

Further complicating matters … Recurrent CDI occurs in up to 10% to 30% of patients,7 typically within 14 to 45 days of completion of antibiotic pharmacotherapy for CDI.8 Recurrence is characterized by new-onset diarrhea or abdominal symptoms after completion of treatment for CDI.5

It typically begins with an antibiotic

Risk factors for CDI are listed in TABLE 1.9 The most important modifiable risk factor for initial and recurrent CDI is recent use of antibiotics.10 Most antibiotics can disrupt normal intestinal flora, causing colonization of C difficile, but the strongest association seems to be with third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and clindamycin.11 The risk for CDI occurs during antibiotic treatment, as well as up to 3 months after completion of antibiotic therapy.7 Exposure to multiple antibiotics and extended duration of antibacterial therapy can greatly increase the risk for CDI, so antimicrobial stewardship is key.11

Continue to: Continuing antibiotics while attempting...

Continuing antibiotics while attempting to treat CDI reduces the patient’s clinical response to CDI treatment, which can lead to recurrence.12 The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines include a strong recommendation to discontinue concurrent antibiotics as soon as possible in these scenarios.11

Acid-suppression therapy has also been associated with CDI. The mechanism is thought to be an interruption in the protection provided by stomach acid, and use over time may reduce the diversity of flora within the gut microbiome.13 The data demonstrating an association between acid-suppression therapy and CDI is conflicting, which may be a result of confounding factors such as the severity of CDI illness and diarrhea induced by use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).4 IDSA guidelines do not provide a recommendation regarding discontinuation of PPI therapy for the prevention of CDI, although inappropriate PPI therapy should always be discontinued.11

Advanced age is an important nonmodifiable risk factor for CDI. Older adults who live in long-term care facilities are at a higher risk for CDI, and these facilities have colonization rates as high as 50%.12

Community-associated risk. In an analysis of community-associated cases of CDI, 82% of patients reported some sort of health care exposure (ranging from physician office visit to surgery admission), 64% reported the receipt of antimicrobial therapy, and 31% reported the use of PPIs.14 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may also put community dwellers at higher risk for CDI and its complications.15

CASES 1 & 2

Both CASE patients have risk factors for CDI. Ms. O (CASE 1) is likely at risk for CDI after completion of her recent course of clindamycin. Ms. Z (CASE 2) has several risk factors for recurrent CDI, including advanced age (≥ 65 years), residence in a long-term care facility, prior antibiotic exposure, and immunodeficiency because of chemotherapy/steroid use.

Continue to: Diagnosis

Diagnosis: Who and how to test

CDI should be both a clinical and laboratory-confirmed diagnosis. Patients should be tested for CDI if they have 3 or more episodes of unexplainable, new-onset unformed stools in 24 hours.11 Asymptomatic patients should not be tested to avoid unnecessary testing and treatment of those who are colonized but not infected.11 It is not recommended to routinely test patients who have taken laxatives within the previous 48 hours.11

There are several stool-based laboratory test options for the diagnosis of CDI (TABLE 211,12,16) but no definitive recommendation for all institutions.11 Many institutions have now implemented PCR testing for the diagnosis of CDI. However, while the benefits of this test include reduced need for repeat testing and possible identification of carriers, it’s estimated that reports of CDI increase more than 50% when an institution switches to PCR testing.1 Nonetheless, a one-step, highly sensitive test such as PCR may be used if strict criteria are implemented and followed.

The increase in positive PCR tests has prompted evaluation of using another test in addition to or in place of PCR. Multistep testing options include a glutamate dehydrogenase assay (GDH) with a toxin EIA, GDH with a toxin EIA and final decision via PCR, or PCR with toxin EIA.11 Use of a multistep diagnostic algorithm may increase overall specificity up to 100%, which may improve determination of asymptomatic colonization vs active infection.16 (Patients who have negative toxin results with positive PCR likely have colonization but not infection and often do not require treatment.) IDSA guidelines recommend that the stool toxin test should be part of a multistep algorithm for diagnosis, rather than PCR alone, if strict criteria are not implemented for stool test submission.11

There is no need to perform a test of cure after a patient has been treated for CDI, and no repeat testing should be performed within 7 days of the previous test.11 After successful treatment, patients will continue to shed spores and test positively via PCR for weeks to months.11 When patients have a positive PCR test, there are several important infection control efforts that institutions should consider; see “IDSA weighs in on measures to combat C difficile.”

SIDEBAR

IDSA weighs in on measures to combat C difficile

The spores produced by Clostridioides difficile can survive for 5 months or longer on dry surfaces because of resistance to heat, acid, antibiotics, and many cleaning products.38 Unfortunately, spores transmitted from health care workers and the environment are the most likely cause of infection spreading in health care institutions. To prevent transmission of C difficile infection (CDI) throughout institutions, appropriate infection control measures are necessary.

Clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend that patients with CDI be isolated to a private room with a dedicated toilet. Health care staff should wear gloves and gowns when entering the room of, or taking care of, a patient with CDI. For patients who are suspected of having CDI, contact precautions should be implemented while awaiting test results. When the diagnosis is confirmed, contact precautions should remain in place for at least 48 hours after resolution of diarrhea but may be continued until discharge.11

Practicing good hand hygiene is essential, especially in institutions with high rates of CDI or if fecal contamination is likely.11 Hand hygiene with soap and water is preferred, due to evidence of a higher spore removal rate, but alcohol-based alternatives may be used if necessary.11 In institutions with high rates of CDI, terminal (post-discharge) cleaning of rooms with a sporicidal agent should be considered.11

Asymptomatic carriers are also a concern for transmission of CDI in institutional settings. Screening and isolating patients who are carriers may prevent transmission, and some institutions have implemented this process to reduce the risk for CDI that originates in a health care facility.39 The IDSA guidelines do not make a recommendation regarding screening or isolation of asymptomatic carriers, so the decision is institution specific.11 These guidelines also recommend that patients presenting with similar infectious organisms be housed in the same room, if needed, to avoid cross-contamination to others or additional surfaces.11

For pediatric patients, testing recommendations vary by age. Testing is not generally recommended for neonates or infants ≤ 2 years of age with diarrhea because of the prevalence of colonization with C difficile.11 For children older than 2 years, testing for CDI is only recommended in the setting of prolonged or worsening diarrhea and if the patient has risk factors such as IBD, immunocompromised state, health care exposure, or recent antibiotic use.11 In addition, testing in this population should only be considered once other infectious and noninfectious causes of diarrhea have been excluded.11

Continue to: First-line treatment? Drug of choice has changed

First-line treatment? Drug of choice has changed

In 2018, the IDSA published new treatment guidelines that provide important updates from the 2010 guidelines.11 Chief among these was the elimination of metronidazole as a first-line therapy. Vancomycin or fidaxomicin are now recommended as first-line treatment options because of superior eradication of C difficile when compared with metronidazole.11 In the opinion of the authors, vancomycin should be considered the drug of choice because of cost. (See “The case for vancomycin.”)

SIDEBAR

The case for vancomycin

The majority of studies conducted prior to publication of the 2010 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines described numerically worse eradication rates of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) with metronidazole compared with vancomycin for all severities of infection, but statistical significance was not achieved. These studies also showed a nonsignificant increase in CDI recurrence with metronidazole.17,40,41

A 2005 systematic review demonstrated increased treatment failure rates with metronidazole.42 The rates of metronidazole discontinuation and transition to alternative options more than doubled in 2003-2004, to 25.7% of patients compared with 9.6% in earlier years.42 Metronidazole efficacy was further questioned in a prospective observational study conducted in 2005, in which only 50% of patients were cured after an initial course of treatment, while 28% had recurrence within 90 days.43

Vancomycin was found to be the superior treatment option to metronidazole and tolevamer in a 2014 randomized controlled trial.18 This study also demonstrated that vancomycin was the superior therapy when comparing treatment-naïve vs experienced patients and severity of CDI.18 A 2017 retrospective cohort study demonstrated decreased 30-day all-cause mortality for patients taking vancomycin vs metronidazole (adjusted relative risk = 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.98), although it should be noted that this difference was driven by those with severe CDI, and there was no statistically significant difference in mortality for patients with mild-to-moderate CDI.44

The results of these studies led to the recommendation of vancomycin over metronidazole as first-line pharmacotherapy for CDI in practice, despite the historical perspective that overutilization of oral vancomycin could potentially increase rates of vancomycinresistant Enterococcus.11

Metronidazole should only be used in the treatment of CDI as a lastresort medication because of cost or insurance coverage. Although the price of oral vancomycin is higher, favorable patient outcomes are substantially greater, and recent analyses have shown that vancomycin is actually more cost-effective than metronidazole as a result.24 Adverse effects for metronidazole include neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal discomfort, and disulfiram-like reaction.

Vancomycin does not harbor as many adverse effects because of extremely low systemic absorption when taken orally, but patients may experience gastrointestinal discomfort.45 While systemic exposure with oral administration of vancomycin is very low (< 1%), there have been case reports of nephrotoxicity and “red man syndrome” that are more typically seen with intravenous vancomycin.44

Given the low rate of systemic exposure, routine monitoring of renal function and serum drug levels is not usually necessary during oral vancomycin therapy. However, it may be appropriate to monitor renal function and serum levels of vancomycin in patients who have renal failure, have altered intestinal integrity, are age ≥ 65 years, or are receiving high doses of vancomycin.46

10-day vs 14-day treatment of CDI. Most studies for the treatment of CDI have used a 10-day regimen rather than increasing the duration to a 14-day regimen, and nearly all studies conducted have displayed high rates of symptom resolution at the end of 10 days of treatment.17,18 Thus, treatment duration beyond 10 days should only be considered for patients who continue to have symptoms or complications with CDI on Day 10 of treatment.

First recurrence. Metronidazole is no longer the recommended treatment for first recurrence of CDI treated initially with metronidazole; instead, a 10-day course of vancomycin should be used.11 For recurrent cases in patients initially treated with vancomycin, a tapered and pulsed regimen of vancomycin is recommended11:

- vancomycin PO 125 mg four times daily for 10 to 14 days followed by

- vancomycin PO 125 mg twice daily for 7 days, then

- vancomycin PO 125 mg once daily for 7 days, then

- vancomycin PO 125 mg every 2 to 3 days for 2 to 8 weeks.

Pediatric patients. The IDSA guidelines recommend use of metronidazole or vancomycin to treat an initial case or first recurrence of mild-to-moderate CDI in this population.11 Due to a lack of quality evidence, the drug of choice for initial treatment is inconclusive, so patient-specific factors and cost should be considered when choosing an agent.11 If not cost prohibitive, vancomycin should be the drug of choice for most cases of pediatric CDI, and for severe cases or multiple recurrences of CDI, vancomycin is clearly the drug of choice.

Recommended agents: A closer look

Oral vancomycin products. Vancocin, a capsule, and Firvanq, an oral solution, are 2 vancomycin products currently on the market for CDI. Although the capsules are a readily available treatment option, the cost of the full course of treatment can be a barrier for patients without insurance, or with high copays or deductibles (brand name, $4000; generic, $1252).19

Continue to: Historically, in an effort to keep costs down...

Historically, in an effort to keep costs down, an oral solution was often inexpensively compounded at hospitals or pharmacies.20

Fidaxomicin, an oral macrocyclic antibiotic with minimal systemic absorption, was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for CDI in 2011.21 The IDSA guidelines recommend fidaxomicin for initial, and recurrent, cases of CDI as an alternative to vancomycin.11 This recommendation is based on 2 randomized double-blind trials comparing fidaxomicin to standard-dose oral vancomycin for initial or recurrent CDI.21,22

Pooled data from these 2 similar studies found that fidaxomicin was noninferior (10% noninferiority margin) to vancomycin for the primary outcome of clinical cure.23 Fidaxomicin was shown to be superior to vancomycin regarding rate of CDI recurrence (relative risk [RR] = 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43-0.87). These results were similar regardless of whether the CDI was an initial or recurrent case.23

Given the lack of systemic absorption, fidaxomicin is generally very well tolerated. The largest downside to fidaxomicin is its cost, which can be nearly $5000 for a standard 10-day course (vs as little as $165 for oral vancomycin).19 As a result, oral vancomycin solution is likely the most cost-effective therapy for initial cases of CDI.24 In patients with poor medication adherence, fidaxomicin offers the advantage of less-frequent dosing (twice daily vs 4 times daily with vancomycin).

For cases of recurrent CDI, when treatment failure occurred with vancomycin, fidaxomicin should be considered as an efficacious alternative. If fidaxomicin is used, it is advisable to verify coverage with the patient’s insurance plan, since prior authorization is frequently required.

Continue to: When meds fail, consider a fecal microbiota transplant

When meds fail, consider a fecal microbiota transplant

Another important change in the IDSA guidelines for CDI management is the strong recommendation for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in patients with multiple recurrences of CDI for whom appropriate antibiotic treatment courses have failed.11,25 The goal of FMT is to “normalize” an abnormal gut microbiome by transplanting donor stool into a recipient.26

FMT has been shown to be highly effective in 5 randomized clinical trials conducted since 2013, with CDI cure rates between 85% and 94%.11 This rate of cure is particularly impressive given that the studies only included patients with refractory CDI.

Patients with recurrent CDI who may be candidates for FMT should be referred to a center or specialist with experience in FMT. These transplants can be expensive because of the screening process involved in obtaining donor samples. (Historically, a single FMT has cost $3000-$5000, and it is seldom covered by insurance.27) The emergence of universal stool banks offers a streamlined solution to this process.26

Fresh or frozen stool is considered equally effective in treating refractory CDI.26 Oral capsule and freeze-dried stool formulations have been studied, but their use is considered investigational at this time.26

Delivery via colonoscopy to the right colon is the preferred route of infusion; however, delivery via enema or nasogastric, nasojejunal, or nasoduodenal infusion can be considered as well.26

Continue to: In preparing for stool transplantation...

In preparing for stool transplantation, patients should be treated with standard doses of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for 3 days before the procedure to suppress intestinal C difficile, and the last dose of antibiotics should be given 12 to 48 hours before the procedure.26 Bowel lavage with polyethylene glycol is recommended, regardless of whether stool is delivered via colonoscopy or upper GI route.

Short-term adverse events associated with FMT appear to be minimal; data is lacking for long-term safety outcomes.28 While only recommended currently for cases of recurrent CDI, there is promising data emerging for use of FMT for severe cases, even without recurrence.29

The role of probiotics remains unclear

Probiotics have been explored in numerous trials to determine if they are effective in preventing CDI in patients who have been prescribed antibiotics.11 While no randomized trials have conclusively shown benefit, several meta-analyses have shown that the use of probiotics may result in a 60% to 65% relative risk reduction in CDI incidence.30,31

One proviso to these meta-analyses is that the incorporated studies have typically included patients at very high risk for CDI, and subanalyses have only found a reduction in CDI incidence when patients are at a very high baseline risk. In addition, there are many differences in probiotic types, formulations, treatment durations, and follow-up. As a result, the IDSA guidelines state that there is “insufficient data at this time” to recommend routine administration of probiotics for either primary or secondary CDI prophylaxis.11

Due to insufficient high-quality data, the IDSA guidelines do not provide a recommendation regarding use as an adjunct treatment option for acute CDI.11 Probiotics should not be routinely used to prevent CDI; however, they may provide benefit if reserved for patients at the highest risk for CDI (eg, history of CDI, prolonged use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, high local incidence).

Continue to: What about surgical intervention?

What about surgical intervention?

In severe cases of CDI, surgery may be necessary and can reduce mortality.32 The surgical procedure with the strongest recommendation in the IDSA guidelines is the subtotal colectomy, though the diverting loop ileostomy is an alternative option.11 Patients who may benefit from surgery include those with a WBC count ≥ 25,000; lactate > 5 mmol/L11; altered mental status; megacolon; perforation of the colon; acute abdomen on physical examination; or septic shock due to CDI.33 Although surgery can be beneficial, the mortality rate remains high for those with CDI who undergo colectomy.33

Reserve bezlotoxumab for prevention of recurrence

Bezlotoxumab, a human monoclonal immunoglobulin GI/kappa antibody, was approved by the FDA in 2016 for the prevention of recurrent CDI. Its mechanism of action is to bind and neutralize C difficile toxin B. It was approved as a single infusion for adults who are receiving active antibiotic therapy for CDI and are considered to be at high risk for recurrence.34

This approval was based on 2 trials of more than 2500 patients, in which participants received bezlotoxumab or placebo while receiving treatment for primary or recurrent CDI. The primary outcome of these studies was recurrent infection within 12 weeks after infusion, which was significantly lower for bezlotoxumab in both studies: 17% vs 28% (P < 0.001) in one trial and 16% vs 26% (P < 0.001) in the other trial.35

Bezlotoxumab should only be used as an adjunct to prevent recurrence.32 There is no recommendation for or against bezlotoxumab in the IDSA guidelines because of the recent date of the drug’s approval. Its frequency of use will likely depend on the number of patients who meet criteria as high risk for recurrence and its estimated cost of $4560 per dose.34,36

CASES

CASE 1: In light of Ms. O’s recent completion of a course of clindamycin and unremarkable lab work, she should be treated for mild-to-moderate CDI. She has no comorbid conditions to warrant fidaxomicin, and thus vancomycin (capsules or oral solution) would be the best treatment option. Ms. O is started on vancomycin PO 125 mg qid for 10 days. She is also advised to discontinue loperamide as soon as possible, based on poor outcomes data seen with the use of antimotility agents in CDI.37

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2: Ms. Z has several risk factors for recurrent CDI and has an elevated WBC count and SCr level (WBC ≥ 15,000 and SCr > 1.5 mg/dL). Thus, she is classified as having severe, recurrent CDI. Oral levofloxacin and metronidazole should be discontinued, because they increase the risk for treatment failure and development of more virulent CDI strains, such as BI/NAP1/027. Since Ms. Z used metronidazole for treatment of her initial CDI, vancomycin or fidaxomicin should be used at this time. Either vancomycin PO 125 mg qid for 10 days or fidaxomicin 200 mg bid for 10 days would be an appropriate regimen; however, because of cost and unknown insurance coverage, vancomycin is the most appropriate regimen.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jeremy Vandiver, PharmD, BCPS, University of Wyoming School of Pharmacy, Saint Joseph Family Medicine Residency, 1000 E. University Avenue, Dept 3375, Laramie, WY 82071; [email protected]

CASE 1

Beth O, a 63-year-old woman, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of diarrhea (6 very loose, watery stools per day) and lower abdominal pain. The patient denies any vomiting, sick contacts, or recent travel. Past medical history includes varicose veins. Her only active medication is loperamide, as needed, for the past 2 weeks. Ms. O also recently completed a 10-day course of clindamycin for an infected laceration on her finger.

Ms. O’s laboratory values are unremarkable, with a normal white blood cell (WBC) count and serum creatinine (SCr) level. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) reveals some abnormal bowel dilatation and a slight increase in colon wall thickness. There is a high suspicion for Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile) infection (CDI), and stool sent for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing comes back positive for C difficile toxin B. It is revealed to be a strain other than the BI/NAP1/027 epidemic strain (which has a higher mortality rate).

How should this patient be treated?

CASE 2

Sixty-eight-year-old Barbara Z presents to the ED from her skilled nursing facility with persistent diarrhea and abdominal cramping. She was diagnosed with CDI about 2 months ago and reports that her symptoms resolved within 4 to 5 days after starting a 14-day course of oral metronidazole.

Her past medical history is notable for multiple myeloma with bone metastasis, for which she is actively undergoing chemotherapy treatment. She also has chronic kidney disease (baseline SCr, 2.2 mg/dL), hypertension, and anemia of chronic disease. The patient’s medications include amlodipine and cholecalciferol. Her chemotherapy regimen consists of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone. CT of the abdomen shows diffuse colon wall thickening with surrounding inflammatory stranding—concerning for pancolitis. There is no evidence of toxic megacolon or ileus.

Ms. Z’s laboratory values are notable for a WBC count of 15,900 cells/mL and an SCr of 4.1 mg/dL. She is started on oral levofloxacin and metronidazole due to concern for an intra-abdominal infection. PCR testing is positive for C difficile, and an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for C difficile toxin is positive.

What factors put Ms. Z at risk for C difficile, and how should she be treated?

Continue to: C difficile is one of the most...

C difficile is one of the most commonly reported pathogens in health care–associated infections and affects almost 1% of all hospitalized patients in the United States each year.1 From 2001 to 2010, the incidence of CDI doubled in patients discharged from hospitals,2 with an estimated cost of more than $5 billion annually.3 Furthermore, rates of community-associated CDI continue to increase and account for about 40% of cases.4

After colonization in the intestine, C difficile releases 2 toxins (TcdA and TcdB) that cause colitis.5 Patients may present with mild diarrhea that can progress to abdominal pain, cramping, fever, and leukocytosis. Fulminant CDI can lead to the formation of pseudomembranes in the colon, toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, shock, and death.2

Beginning in the early 2000s, hospitals reported increases in severe cases of CDI.6 A specific strain known as BI/NAP1/027 was identified and characterized by fluoroquinolone resistance, increased spore formation, and a higher mortality rate.6

Further complicating matters … Recurrent CDI occurs in up to 10% to 30% of patients,7 typically within 14 to 45 days of completion of antibiotic pharmacotherapy for CDI.8 Recurrence is characterized by new-onset diarrhea or abdominal symptoms after completion of treatment for CDI.5

It typically begins with an antibiotic

Risk factors for CDI are listed in TABLE 1.9 The most important modifiable risk factor for initial and recurrent CDI is recent use of antibiotics.10 Most antibiotics can disrupt normal intestinal flora, causing colonization of C difficile, but the strongest association seems to be with third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and clindamycin.11 The risk for CDI occurs during antibiotic treatment, as well as up to 3 months after completion of antibiotic therapy.7 Exposure to multiple antibiotics and extended duration of antibacterial therapy can greatly increase the risk for CDI, so antimicrobial stewardship is key.11

Continue to: Continuing antibiotics while attempting...

Continuing antibiotics while attempting to treat CDI reduces the patient’s clinical response to CDI treatment, which can lead to recurrence.12 The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines include a strong recommendation to discontinue concurrent antibiotics as soon as possible in these scenarios.11

Acid-suppression therapy has also been associated with CDI. The mechanism is thought to be an interruption in the protection provided by stomach acid, and use over time may reduce the diversity of flora within the gut microbiome.13 The data demonstrating an association between acid-suppression therapy and CDI is conflicting, which may be a result of confounding factors such as the severity of CDI illness and diarrhea induced by use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).4 IDSA guidelines do not provide a recommendation regarding discontinuation of PPI therapy for the prevention of CDI, although inappropriate PPI therapy should always be discontinued.11

Advanced age is an important nonmodifiable risk factor for CDI. Older adults who live in long-term care facilities are at a higher risk for CDI, and these facilities have colonization rates as high as 50%.12

Community-associated risk. In an analysis of community-associated cases of CDI, 82% of patients reported some sort of health care exposure (ranging from physician office visit to surgery admission), 64% reported the receipt of antimicrobial therapy, and 31% reported the use of PPIs.14 Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) may also put community dwellers at higher risk for CDI and its complications.15

CASES 1 & 2

Both CASE patients have risk factors for CDI. Ms. O (CASE 1) is likely at risk for CDI after completion of her recent course of clindamycin. Ms. Z (CASE 2) has several risk factors for recurrent CDI, including advanced age (≥ 65 years), residence in a long-term care facility, prior antibiotic exposure, and immunodeficiency because of chemotherapy/steroid use.

Continue to: Diagnosis

Diagnosis: Who and how to test

CDI should be both a clinical and laboratory-confirmed diagnosis. Patients should be tested for CDI if they have 3 or more episodes of unexplainable, new-onset unformed stools in 24 hours.11 Asymptomatic patients should not be tested to avoid unnecessary testing and treatment of those who are colonized but not infected.11 It is not recommended to routinely test patients who have taken laxatives within the previous 48 hours.11

There are several stool-based laboratory test options for the diagnosis of CDI (TABLE 211,12,16) but no definitive recommendation for all institutions.11 Many institutions have now implemented PCR testing for the diagnosis of CDI. However, while the benefits of this test include reduced need for repeat testing and possible identification of carriers, it’s estimated that reports of CDI increase more than 50% when an institution switches to PCR testing.1 Nonetheless, a one-step, highly sensitive test such as PCR may be used if strict criteria are implemented and followed.

The increase in positive PCR tests has prompted evaluation of using another test in addition to or in place of PCR. Multistep testing options include a glutamate dehydrogenase assay (GDH) with a toxin EIA, GDH with a toxin EIA and final decision via PCR, or PCR with toxin EIA.11 Use of a multistep diagnostic algorithm may increase overall specificity up to 100%, which may improve determination of asymptomatic colonization vs active infection.16 (Patients who have negative toxin results with positive PCR likely have colonization but not infection and often do not require treatment.) IDSA guidelines recommend that the stool toxin test should be part of a multistep algorithm for diagnosis, rather than PCR alone, if strict criteria are not implemented for stool test submission.11

There is no need to perform a test of cure after a patient has been treated for CDI, and no repeat testing should be performed within 7 days of the previous test.11 After successful treatment, patients will continue to shed spores and test positively via PCR for weeks to months.11 When patients have a positive PCR test, there are several important infection control efforts that institutions should consider; see “IDSA weighs in on measures to combat C difficile.”

SIDEBAR

IDSA weighs in on measures to combat C difficile

The spores produced by Clostridioides difficile can survive for 5 months or longer on dry surfaces because of resistance to heat, acid, antibiotics, and many cleaning products.38 Unfortunately, spores transmitted from health care workers and the environment are the most likely cause of infection spreading in health care institutions. To prevent transmission of C difficile infection (CDI) throughout institutions, appropriate infection control measures are necessary.

Clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommend that patients with CDI be isolated to a private room with a dedicated toilet. Health care staff should wear gloves and gowns when entering the room of, or taking care of, a patient with CDI. For patients who are suspected of having CDI, contact precautions should be implemented while awaiting test results. When the diagnosis is confirmed, contact precautions should remain in place for at least 48 hours after resolution of diarrhea but may be continued until discharge.11

Practicing good hand hygiene is essential, especially in institutions with high rates of CDI or if fecal contamination is likely.11 Hand hygiene with soap and water is preferred, due to evidence of a higher spore removal rate, but alcohol-based alternatives may be used if necessary.11 In institutions with high rates of CDI, terminal (post-discharge) cleaning of rooms with a sporicidal agent should be considered.11

Asymptomatic carriers are also a concern for transmission of CDI in institutional settings. Screening and isolating patients who are carriers may prevent transmission, and some institutions have implemented this process to reduce the risk for CDI that originates in a health care facility.39 The IDSA guidelines do not make a recommendation regarding screening or isolation of asymptomatic carriers, so the decision is institution specific.11 These guidelines also recommend that patients presenting with similar infectious organisms be housed in the same room, if needed, to avoid cross-contamination to others or additional surfaces.11

For pediatric patients, testing recommendations vary by age. Testing is not generally recommended for neonates or infants ≤ 2 years of age with diarrhea because of the prevalence of colonization with C difficile.11 For children older than 2 years, testing for CDI is only recommended in the setting of prolonged or worsening diarrhea and if the patient has risk factors such as IBD, immunocompromised state, health care exposure, or recent antibiotic use.11 In addition, testing in this population should only be considered once other infectious and noninfectious causes of diarrhea have been excluded.11

Continue to: First-line treatment? Drug of choice has changed

First-line treatment? Drug of choice has changed

In 2018, the IDSA published new treatment guidelines that provide important updates from the 2010 guidelines.11 Chief among these was the elimination of metronidazole as a first-line therapy. Vancomycin or fidaxomicin are now recommended as first-line treatment options because of superior eradication of C difficile when compared with metronidazole.11 In the opinion of the authors, vancomycin should be considered the drug of choice because of cost. (See “The case for vancomycin.”)

SIDEBAR

The case for vancomycin

The majority of studies conducted prior to publication of the 2010 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines described numerically worse eradication rates of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) with metronidazole compared with vancomycin for all severities of infection, but statistical significance was not achieved. These studies also showed a nonsignificant increase in CDI recurrence with metronidazole.17,40,41

A 2005 systematic review demonstrated increased treatment failure rates with metronidazole.42 The rates of metronidazole discontinuation and transition to alternative options more than doubled in 2003-2004, to 25.7% of patients compared with 9.6% in earlier years.42 Metronidazole efficacy was further questioned in a prospective observational study conducted in 2005, in which only 50% of patients were cured after an initial course of treatment, while 28% had recurrence within 90 days.43

Vancomycin was found to be the superior treatment option to metronidazole and tolevamer in a 2014 randomized controlled trial.18 This study also demonstrated that vancomycin was the superior therapy when comparing treatment-naïve vs experienced patients and severity of CDI.18 A 2017 retrospective cohort study demonstrated decreased 30-day all-cause mortality for patients taking vancomycin vs metronidazole (adjusted relative risk = 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.98), although it should be noted that this difference was driven by those with severe CDI, and there was no statistically significant difference in mortality for patients with mild-to-moderate CDI.44

The results of these studies led to the recommendation of vancomycin over metronidazole as first-line pharmacotherapy for CDI in practice, despite the historical perspective that overutilization of oral vancomycin could potentially increase rates of vancomycinresistant Enterococcus.11

Metronidazole should only be used in the treatment of CDI as a lastresort medication because of cost or insurance coverage. Although the price of oral vancomycin is higher, favorable patient outcomes are substantially greater, and recent analyses have shown that vancomycin is actually more cost-effective than metronidazole as a result.24 Adverse effects for metronidazole include neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal discomfort, and disulfiram-like reaction.

Vancomycin does not harbor as many adverse effects because of extremely low systemic absorption when taken orally, but patients may experience gastrointestinal discomfort.45 While systemic exposure with oral administration of vancomycin is very low (< 1%), there have been case reports of nephrotoxicity and “red man syndrome” that are more typically seen with intravenous vancomycin.44

Given the low rate of systemic exposure, routine monitoring of renal function and serum drug levels is not usually necessary during oral vancomycin therapy. However, it may be appropriate to monitor renal function and serum levels of vancomycin in patients who have renal failure, have altered intestinal integrity, are age ≥ 65 years, or are receiving high doses of vancomycin.46

10-day vs 14-day treatment of CDI. Most studies for the treatment of CDI have used a 10-day regimen rather than increasing the duration to a 14-day regimen, and nearly all studies conducted have displayed high rates of symptom resolution at the end of 10 days of treatment.17,18 Thus, treatment duration beyond 10 days should only be considered for patients who continue to have symptoms or complications with CDI on Day 10 of treatment.

First recurrence. Metronidazole is no longer the recommended treatment for first recurrence of CDI treated initially with metronidazole; instead, a 10-day course of vancomycin should be used.11 For recurrent cases in patients initially treated with vancomycin, a tapered and pulsed regimen of vancomycin is recommended11:

- vancomycin PO 125 mg four times daily for 10 to 14 days followed by

- vancomycin PO 125 mg twice daily for 7 days, then

- vancomycin PO 125 mg once daily for 7 days, then

- vancomycin PO 125 mg every 2 to 3 days for 2 to 8 weeks.

Pediatric patients. The IDSA guidelines recommend use of metronidazole or vancomycin to treat an initial case or first recurrence of mild-to-moderate CDI in this population.11 Due to a lack of quality evidence, the drug of choice for initial treatment is inconclusive, so patient-specific factors and cost should be considered when choosing an agent.11 If not cost prohibitive, vancomycin should be the drug of choice for most cases of pediatric CDI, and for severe cases or multiple recurrences of CDI, vancomycin is clearly the drug of choice.

Recommended agents: A closer look

Oral vancomycin products. Vancocin, a capsule, and Firvanq, an oral solution, are 2 vancomycin products currently on the market for CDI. Although the capsules are a readily available treatment option, the cost of the full course of treatment can be a barrier for patients without insurance, or with high copays or deductibles (brand name, $4000; generic, $1252).19

Continue to: Historically, in an effort to keep costs down...

Historically, in an effort to keep costs down, an oral solution was often inexpensively compounded at hospitals or pharmacies.20

Fidaxomicin, an oral macrocyclic antibiotic with minimal systemic absorption, was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for CDI in 2011.21 The IDSA guidelines recommend fidaxomicin for initial, and recurrent, cases of CDI as an alternative to vancomycin.11 This recommendation is based on 2 randomized double-blind trials comparing fidaxomicin to standard-dose oral vancomycin for initial or recurrent CDI.21,22

Pooled data from these 2 similar studies found that fidaxomicin was noninferior (10% noninferiority margin) to vancomycin for the primary outcome of clinical cure.23 Fidaxomicin was shown to be superior to vancomycin regarding rate of CDI recurrence (relative risk [RR] = 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43-0.87). These results were similar regardless of whether the CDI was an initial or recurrent case.23