User login

Volunteering during the pandemic: What doctors need to know

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a silly picture of myself with one N95 mask and asked the folks on Twitter what else I might need. In a matter of a few days, I had filled out a form online for volunteering through the Society of Critical Care Medicine, been assigned to work at a hospital in New York City, and booked a hotel and flight.

I was going to volunteer, although I wasn’t sure of exactly what I would be doing. I’m trained as a bariatric surgeon – not obviously suited for critical care, but arguably even less suited for medicine wards.

I undoubtedly would have been less prepared if I hadn’t sought guidance on what to bring with me and generally what to expect. Less than a day after seeking advice, two local women physicians donated N95s, face shields, gowns, bouffants, and coveralls to me. I also received a laminated photo of myself to attach to my gown in the mail from a stranger I met online.

Others suggested I bring goggles, chocolate, protein bars, hand sanitizer, powdered laundry detergent, and alcohol wipes. After running around all over town, I was able find everything but the wipes.

Just as others helped me achieve my goal of volunteering, I hope I can guide those who would like to do similar work by sharing details about my experience and other information I have collected about volunteering.

Below I answer some questions that those considering volunteering might have, including why I went, who I contacted to set this up, who paid for my flight, and what I observed in the hospital.

Motivation and logistics

I am currently serving in a nonclinical role at my institution. So when the pandemic hit the United States, I felt an immense amount of guilt for not being on the front lines caring for patients. I offered my services to local hospitals and registered for the California Health Corps. I live in northern California, which was the first part of the country to shelter in place. Since my home was actually relatively spared, my services weren’t needed.

As the weeks passed, I was slowly getting more and more fit, exercising in my house since there was little else I could do, and the guilt became a cloud gathering over my head.

I decided to volunteer in a place where demands for help were higher – New York. I tried very hard to sign up to volunteer through the state’s registry for health care volunteers, but was unable to do so. Coincidentally, around that same time, I saw on Twitter that Josh Mugele, MD, emergency medicine physician and program director of the emergency medicine residency at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville, was on his way to New York. He shared the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s form for volunteering with me, and in less than 48 hours, I was assigned to a hospital in New York City. Five days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to my destination on the opposite side of the country. The airline paid for my flight.

This is not the only path to volunteering. Another volunteer, Sara Pauk, MD, ob.gyn. at the University of Washington, Seattle, found her volunteer role through contacting the New York City Health and Hospitals system directly. Other who have volunteered told me they had contacted specific hospitals or worked with agencies that were placing physicians.

PPE

The Brooklyn hospital where I volunteered provided me with two sets of scrubs and two N95s. Gowns were variably available on our unit, and there was no eye protection. As a colleague of mine, Ben Daxon, MD, anesthesia and critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., had suggested, anyone volunteering in this context should bring personal protective equipment (PPE) – That includes gowns, bouffants/scrub caps, eye protection, masks, and scrubs.

The “COVID corner”

Once I arrived in New York, I did not feel particularly safe in my hotel, so I moved to another the next day. Then I had to sort out how to keep the whole room from being contaminated. I created a “COVID corner” right by the door where I kept almost everything that had been outside the door.

Every time I walked in the door, I immediately took off my shoes and left them in that corner. I could not find alcohol wipes, even after looking around in the city, so I relied on time to kill the virus, which I presumed was on everything that came from outside.

Groceries stayed by the door for 48-72 hours if possible. After that, I would move them to the “clean” parts of the room. I wore the same outfit to and from the hospital everyday, putting it on right before I left and taking it off immediately after walking into the room (and then proceeding directly to the shower). Those clothes – “my COVID outfit” – lived in the COVID corner. Anything else I wore, including exercise clothes and underwear, got washed right after I wore it.

At the hospital, I would change into scrubs and leave my COVID outfit in a plastic bag inside my handbag. Note: I fully accepted that my handbag was now a COVID handbag. I kept a pair of clogs in the hospital for daily wear. Without alcohol wipes, my room did not feel clean. But I did start to become at peace with my system, even though it was inferior to the system I use in my own home.

Meal time

In addition to bringing snacks from home, I gathered some meal items at a grocery store during my first day in New York. These included water, yogurt, a few protein drinks, fruit, and some mini chocolate croissants. It’s a pandemic – chocolate is encouraged, right?

Neither any of the volunteers I knew nor I had access to a kitchen, so this was about the best I could do.

My first week I worked nights and ate sporadically. A couple of days I bought bagel sandwiches on the way back to the hotel in the morning. Other times, I would eat yogurt or a protein bar.

I had trouble sleeping, so I would wake up early and either do yoga in my room or go for a run in a nearby park. Usually I didn’t plan well enough to eat before I went into the hospital, so I would take yogurt, some fruit, and a croissant with me as I headed out. It was hard eating on the run with a mask on my face.

When I switched to working days, I actually ordered proper dinners from local Thai, Mexican, and Indian restaurants. I paid around $20 a meal.

One night I even had dinner with a coworker who was staying at a hotel close to mine – what a luxury! Prior to all this I had been sheltering in place alone for weeks, so in that sense, this experience was a delight. I interacted with other people, in person, every day!

My commute

My hotel was about 20 minutes from the hospital. Well-meaning folks informed me that Hertz had free car rentals and Uber had discounts for health care workers. When I investigated these options, I found that only employees of certain hospitals were eligible. As a volunteer, I was not eligible.

I ultimately took Uber back and forth, and I was lucky that a few friends had sent me Uber gift cards to defray the costs. Most days, I paid about $20 each way, although 1 day there actually was “surge pricing.” The grand total for the trip was close to $800.

Many of the Uber drivers had put up plastic partitions – reminiscent of the plastic Dexter would use to contain his crime scenes – to increase their separation from their passengers. It was a bit eerie, but also somewhat welcome.

New normal

The actual work at the hospital in Brooklyn where I volunteered was different from usual practice in numerous ways. One of the things I immediately noticed was how difficult it was to get chest x-rays. After placing an emergent chest tube for a tension pneumothorax, it took about 6 hours to get a chest x-ray to assess placement.

Because code medications were needed much more frequently than normal times, these medications were kept in an open supply closet for ease of access. Many of the ventilators looked like they were from the 1970s. (They had been borrowed from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.)

What was most distinct about this work was the sheer volume of deaths and dying patients -- at least one death on our unit occurred every day I was there -- and the way families communicated with their loved ones. Countless times I held my phone over the faces of my unconscious patients to let their family profess their love and beg them to fight. While I have had to deliver bad news over the phone many times in my career, I have never had to intrude on families’ last conversations with their dying loved ones or witness that conversation occurring via a tiny screen.

Reentry

In many ways, I am lucky that I do not do clinical work in my hometown. So while other volunteers were figuring out how many more vacation days they would have to use, or whether they would have to take unpaid leave, and when and how they would get tested, all I had to do was prepare to go back home and quarantine myself for a couple of weeks.

I used up 2 weeks of vacation to volunteer in New York, but luckily, I could resume my normal work the day after I returned home.

Obviously, living in the pandemic is unique to anything we have ever experienced. Recognizing that, I recorded video diaries the whole time I was in New York. I laughed (like when I tried to fit all of my PPE on my tiny head), and I cried – several times. I suppose 1 day I may actually watch them and be reminded of what it was like to have been able to serve in this historic moment. Until then, they will remain locked up on the same phone that served as the only communication vehicle between my patients and their loved ones.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University.

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a silly picture of myself with one N95 mask and asked the folks on Twitter what else I might need. In a matter of a few days, I had filled out a form online for volunteering through the Society of Critical Care Medicine, been assigned to work at a hospital in New York City, and booked a hotel and flight.

I was going to volunteer, although I wasn’t sure of exactly what I would be doing. I’m trained as a bariatric surgeon – not obviously suited for critical care, but arguably even less suited for medicine wards.

I undoubtedly would have been less prepared if I hadn’t sought guidance on what to bring with me and generally what to expect. Less than a day after seeking advice, two local women physicians donated N95s, face shields, gowns, bouffants, and coveralls to me. I also received a laminated photo of myself to attach to my gown in the mail from a stranger I met online.

Others suggested I bring goggles, chocolate, protein bars, hand sanitizer, powdered laundry detergent, and alcohol wipes. After running around all over town, I was able find everything but the wipes.

Just as others helped me achieve my goal of volunteering, I hope I can guide those who would like to do similar work by sharing details about my experience and other information I have collected about volunteering.

Below I answer some questions that those considering volunteering might have, including why I went, who I contacted to set this up, who paid for my flight, and what I observed in the hospital.

Motivation and logistics

I am currently serving in a nonclinical role at my institution. So when the pandemic hit the United States, I felt an immense amount of guilt for not being on the front lines caring for patients. I offered my services to local hospitals and registered for the California Health Corps. I live in northern California, which was the first part of the country to shelter in place. Since my home was actually relatively spared, my services weren’t needed.

As the weeks passed, I was slowly getting more and more fit, exercising in my house since there was little else I could do, and the guilt became a cloud gathering over my head.

I decided to volunteer in a place where demands for help were higher – New York. I tried very hard to sign up to volunteer through the state’s registry for health care volunteers, but was unable to do so. Coincidentally, around that same time, I saw on Twitter that Josh Mugele, MD, emergency medicine physician and program director of the emergency medicine residency at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville, was on his way to New York. He shared the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s form for volunteering with me, and in less than 48 hours, I was assigned to a hospital in New York City. Five days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to my destination on the opposite side of the country. The airline paid for my flight.

This is not the only path to volunteering. Another volunteer, Sara Pauk, MD, ob.gyn. at the University of Washington, Seattle, found her volunteer role through contacting the New York City Health and Hospitals system directly. Other who have volunteered told me they had contacted specific hospitals or worked with agencies that were placing physicians.

PPE

The Brooklyn hospital where I volunteered provided me with two sets of scrubs and two N95s. Gowns were variably available on our unit, and there was no eye protection. As a colleague of mine, Ben Daxon, MD, anesthesia and critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., had suggested, anyone volunteering in this context should bring personal protective equipment (PPE) – That includes gowns, bouffants/scrub caps, eye protection, masks, and scrubs.

The “COVID corner”

Once I arrived in New York, I did not feel particularly safe in my hotel, so I moved to another the next day. Then I had to sort out how to keep the whole room from being contaminated. I created a “COVID corner” right by the door where I kept almost everything that had been outside the door.

Every time I walked in the door, I immediately took off my shoes and left them in that corner. I could not find alcohol wipes, even after looking around in the city, so I relied on time to kill the virus, which I presumed was on everything that came from outside.

Groceries stayed by the door for 48-72 hours if possible. After that, I would move them to the “clean” parts of the room. I wore the same outfit to and from the hospital everyday, putting it on right before I left and taking it off immediately after walking into the room (and then proceeding directly to the shower). Those clothes – “my COVID outfit” – lived in the COVID corner. Anything else I wore, including exercise clothes and underwear, got washed right after I wore it.

At the hospital, I would change into scrubs and leave my COVID outfit in a plastic bag inside my handbag. Note: I fully accepted that my handbag was now a COVID handbag. I kept a pair of clogs in the hospital for daily wear. Without alcohol wipes, my room did not feel clean. But I did start to become at peace with my system, even though it was inferior to the system I use in my own home.

Meal time

In addition to bringing snacks from home, I gathered some meal items at a grocery store during my first day in New York. These included water, yogurt, a few protein drinks, fruit, and some mini chocolate croissants. It’s a pandemic – chocolate is encouraged, right?

Neither any of the volunteers I knew nor I had access to a kitchen, so this was about the best I could do.

My first week I worked nights and ate sporadically. A couple of days I bought bagel sandwiches on the way back to the hotel in the morning. Other times, I would eat yogurt or a protein bar.

I had trouble sleeping, so I would wake up early and either do yoga in my room or go for a run in a nearby park. Usually I didn’t plan well enough to eat before I went into the hospital, so I would take yogurt, some fruit, and a croissant with me as I headed out. It was hard eating on the run with a mask on my face.

When I switched to working days, I actually ordered proper dinners from local Thai, Mexican, and Indian restaurants. I paid around $20 a meal.

One night I even had dinner with a coworker who was staying at a hotel close to mine – what a luxury! Prior to all this I had been sheltering in place alone for weeks, so in that sense, this experience was a delight. I interacted with other people, in person, every day!

My commute

My hotel was about 20 minutes from the hospital. Well-meaning folks informed me that Hertz had free car rentals and Uber had discounts for health care workers. When I investigated these options, I found that only employees of certain hospitals were eligible. As a volunteer, I was not eligible.

I ultimately took Uber back and forth, and I was lucky that a few friends had sent me Uber gift cards to defray the costs. Most days, I paid about $20 each way, although 1 day there actually was “surge pricing.” The grand total for the trip was close to $800.

Many of the Uber drivers had put up plastic partitions – reminiscent of the plastic Dexter would use to contain his crime scenes – to increase their separation from their passengers. It was a bit eerie, but also somewhat welcome.

New normal

The actual work at the hospital in Brooklyn where I volunteered was different from usual practice in numerous ways. One of the things I immediately noticed was how difficult it was to get chest x-rays. After placing an emergent chest tube for a tension pneumothorax, it took about 6 hours to get a chest x-ray to assess placement.

Because code medications were needed much more frequently than normal times, these medications were kept in an open supply closet for ease of access. Many of the ventilators looked like they were from the 1970s. (They had been borrowed from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.)

What was most distinct about this work was the sheer volume of deaths and dying patients -- at least one death on our unit occurred every day I was there -- and the way families communicated with their loved ones. Countless times I held my phone over the faces of my unconscious patients to let their family profess their love and beg them to fight. While I have had to deliver bad news over the phone many times in my career, I have never had to intrude on families’ last conversations with their dying loved ones or witness that conversation occurring via a tiny screen.

Reentry

In many ways, I am lucky that I do not do clinical work in my hometown. So while other volunteers were figuring out how many more vacation days they would have to use, or whether they would have to take unpaid leave, and when and how they would get tested, all I had to do was prepare to go back home and quarantine myself for a couple of weeks.

I used up 2 weeks of vacation to volunteer in New York, but luckily, I could resume my normal work the day after I returned home.

Obviously, living in the pandemic is unique to anything we have ever experienced. Recognizing that, I recorded video diaries the whole time I was in New York. I laughed (like when I tried to fit all of my PPE on my tiny head), and I cried – several times. I suppose 1 day I may actually watch them and be reminded of what it was like to have been able to serve in this historic moment. Until then, they will remain locked up on the same phone that served as the only communication vehicle between my patients and their loved ones.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University.

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a silly picture of myself with one N95 mask and asked the folks on Twitter what else I might need. In a matter of a few days, I had filled out a form online for volunteering through the Society of Critical Care Medicine, been assigned to work at a hospital in New York City, and booked a hotel and flight.

I was going to volunteer, although I wasn’t sure of exactly what I would be doing. I’m trained as a bariatric surgeon – not obviously suited for critical care, but arguably even less suited for medicine wards.

I undoubtedly would have been less prepared if I hadn’t sought guidance on what to bring with me and generally what to expect. Less than a day after seeking advice, two local women physicians donated N95s, face shields, gowns, bouffants, and coveralls to me. I also received a laminated photo of myself to attach to my gown in the mail from a stranger I met online.

Others suggested I bring goggles, chocolate, protein bars, hand sanitizer, powdered laundry detergent, and alcohol wipes. After running around all over town, I was able find everything but the wipes.

Just as others helped me achieve my goal of volunteering, I hope I can guide those who would like to do similar work by sharing details about my experience and other information I have collected about volunteering.

Below I answer some questions that those considering volunteering might have, including why I went, who I contacted to set this up, who paid for my flight, and what I observed in the hospital.

Motivation and logistics

I am currently serving in a nonclinical role at my institution. So when the pandemic hit the United States, I felt an immense amount of guilt for not being on the front lines caring for patients. I offered my services to local hospitals and registered for the California Health Corps. I live in northern California, which was the first part of the country to shelter in place. Since my home was actually relatively spared, my services weren’t needed.

As the weeks passed, I was slowly getting more and more fit, exercising in my house since there was little else I could do, and the guilt became a cloud gathering over my head.

I decided to volunteer in a place where demands for help were higher – New York. I tried very hard to sign up to volunteer through the state’s registry for health care volunteers, but was unable to do so. Coincidentally, around that same time, I saw on Twitter that Josh Mugele, MD, emergency medicine physician and program director of the emergency medicine residency at Northeast Georgia Medical Center in Gainesville, was on his way to New York. He shared the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s form for volunteering with me, and in less than 48 hours, I was assigned to a hospital in New York City. Five days later I was on a plane from San Francisco to my destination on the opposite side of the country. The airline paid for my flight.

This is not the only path to volunteering. Another volunteer, Sara Pauk, MD, ob.gyn. at the University of Washington, Seattle, found her volunteer role through contacting the New York City Health and Hospitals system directly. Other who have volunteered told me they had contacted specific hospitals or worked with agencies that were placing physicians.

PPE

The Brooklyn hospital where I volunteered provided me with two sets of scrubs and two N95s. Gowns were variably available on our unit, and there was no eye protection. As a colleague of mine, Ben Daxon, MD, anesthesia and critical care physician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., had suggested, anyone volunteering in this context should bring personal protective equipment (PPE) – That includes gowns, bouffants/scrub caps, eye protection, masks, and scrubs.

The “COVID corner”

Once I arrived in New York, I did not feel particularly safe in my hotel, so I moved to another the next day. Then I had to sort out how to keep the whole room from being contaminated. I created a “COVID corner” right by the door where I kept almost everything that had been outside the door.

Every time I walked in the door, I immediately took off my shoes and left them in that corner. I could not find alcohol wipes, even after looking around in the city, so I relied on time to kill the virus, which I presumed was on everything that came from outside.

Groceries stayed by the door for 48-72 hours if possible. After that, I would move them to the “clean” parts of the room. I wore the same outfit to and from the hospital everyday, putting it on right before I left and taking it off immediately after walking into the room (and then proceeding directly to the shower). Those clothes – “my COVID outfit” – lived in the COVID corner. Anything else I wore, including exercise clothes and underwear, got washed right after I wore it.

At the hospital, I would change into scrubs and leave my COVID outfit in a plastic bag inside my handbag. Note: I fully accepted that my handbag was now a COVID handbag. I kept a pair of clogs in the hospital for daily wear. Without alcohol wipes, my room did not feel clean. But I did start to become at peace with my system, even though it was inferior to the system I use in my own home.

Meal time

In addition to bringing snacks from home, I gathered some meal items at a grocery store during my first day in New York. These included water, yogurt, a few protein drinks, fruit, and some mini chocolate croissants. It’s a pandemic – chocolate is encouraged, right?

Neither any of the volunteers I knew nor I had access to a kitchen, so this was about the best I could do.

My first week I worked nights and ate sporadically. A couple of days I bought bagel sandwiches on the way back to the hotel in the morning. Other times, I would eat yogurt or a protein bar.

I had trouble sleeping, so I would wake up early and either do yoga in my room or go for a run in a nearby park. Usually I didn’t plan well enough to eat before I went into the hospital, so I would take yogurt, some fruit, and a croissant with me as I headed out. It was hard eating on the run with a mask on my face.

When I switched to working days, I actually ordered proper dinners from local Thai, Mexican, and Indian restaurants. I paid around $20 a meal.

One night I even had dinner with a coworker who was staying at a hotel close to mine – what a luxury! Prior to all this I had been sheltering in place alone for weeks, so in that sense, this experience was a delight. I interacted with other people, in person, every day!

My commute

My hotel was about 20 minutes from the hospital. Well-meaning folks informed me that Hertz had free car rentals and Uber had discounts for health care workers. When I investigated these options, I found that only employees of certain hospitals were eligible. As a volunteer, I was not eligible.

I ultimately took Uber back and forth, and I was lucky that a few friends had sent me Uber gift cards to defray the costs. Most days, I paid about $20 each way, although 1 day there actually was “surge pricing.” The grand total for the trip was close to $800.

Many of the Uber drivers had put up plastic partitions – reminiscent of the plastic Dexter would use to contain his crime scenes – to increase their separation from their passengers. It was a bit eerie, but also somewhat welcome.

New normal

The actual work at the hospital in Brooklyn where I volunteered was different from usual practice in numerous ways. One of the things I immediately noticed was how difficult it was to get chest x-rays. After placing an emergent chest tube for a tension pneumothorax, it took about 6 hours to get a chest x-ray to assess placement.

Because code medications were needed much more frequently than normal times, these medications were kept in an open supply closet for ease of access. Many of the ventilators looked like they were from the 1970s. (They had been borrowed from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.)

What was most distinct about this work was the sheer volume of deaths and dying patients -- at least one death on our unit occurred every day I was there -- and the way families communicated with their loved ones. Countless times I held my phone over the faces of my unconscious patients to let their family profess their love and beg them to fight. While I have had to deliver bad news over the phone many times in my career, I have never had to intrude on families’ last conversations with their dying loved ones or witness that conversation occurring via a tiny screen.

Reentry

In many ways, I am lucky that I do not do clinical work in my hometown. So while other volunteers were figuring out how many more vacation days they would have to use, or whether they would have to take unpaid leave, and when and how they would get tested, all I had to do was prepare to go back home and quarantine myself for a couple of weeks.

I used up 2 weeks of vacation to volunteer in New York, but luckily, I could resume my normal work the day after I returned home.

Obviously, living in the pandemic is unique to anything we have ever experienced. Recognizing that, I recorded video diaries the whole time I was in New York. I laughed (like when I tried to fit all of my PPE on my tiny head), and I cried – several times. I suppose 1 day I may actually watch them and be reminded of what it was like to have been able to serve in this historic moment. Until then, they will remain locked up on the same phone that served as the only communication vehicle between my patients and their loved ones.

Dr. Salles is a bariatric surgeon and is currently a Scholar in Residence at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Pandemic-related stress rising among ICU clinicians

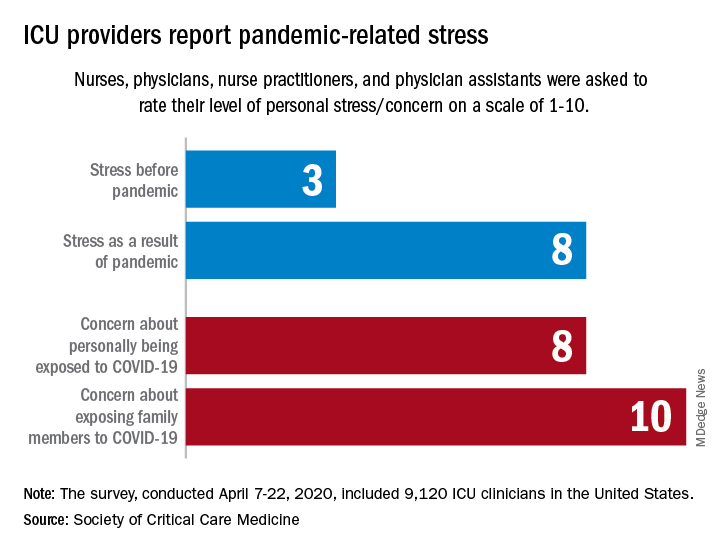

They are worried about getting infected, and they are even more worried about infecting family members, according to the Society for Critical Care Medicine, which surveyed members of four professional organizations – the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and the SCCM – April 7-22, 2020.

Four items in the survey assessed respondents’ level of stress or concern on a scale of 1-10:

- Personal stress before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Personal stress as a result of COVID-19 pandemic.

- Concern about personally being exposed to COVID-19.

- Concern about exposing family members to COVID-19.

Personal stress rose from a median of 3 before the pandemic to a current 8, a level that was equaled by personal concerns about being exposed and surpassed (10) by concerns about exposing family members, the SCCM reported in a blog post.

Most of the respondents “are taking special measures to limit the potential spread of the virus to their loved ones, including implementing a decontamination routine before interacting with families,” the SCCM wrote.

The most common strategy, employed by 72% of ICU clinicians, is changing clothes before/after work. Showering before joining family was mentioned by 64% of providers, followed by limiting contact until decontamination (57%) and using hand sanitizer before entering home (51%), the SCCM said.

More extreme measures included self-isolating within their homes (16%) and staying in alternative housing away from their families (12%), the SCCM said, based on data for 9,120 clinicians in the United States.

Most of the respondents (88%) reported having cared for a patient with confirmed or presumed COVID-19. Nurses made up the majority (91%) of the sample, which also included nurse practitioners and physician assistants (4.5%) and physicians (2.9%), as well as smaller numbers of respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and emergency medicine flight personnel.

The results of the survey “underline the personal sacrifices of critical care clinicians during the COVID-19 response and suggest the need to help them proactively manage stress,” the SCCM wrote.

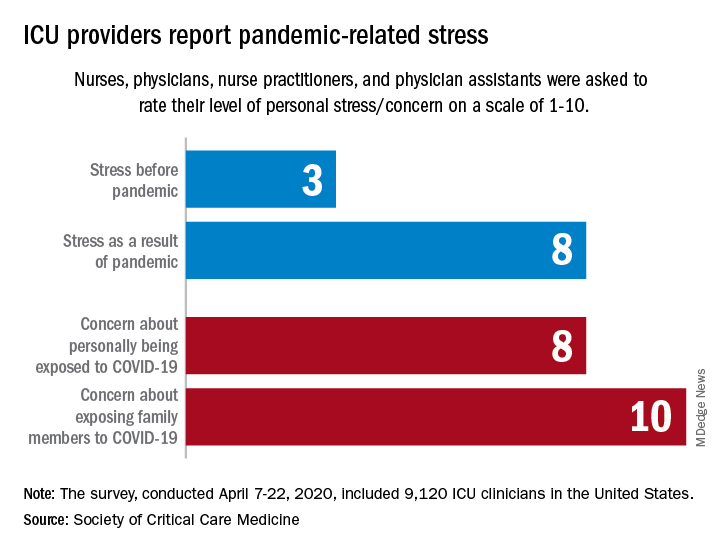

They are worried about getting infected, and they are even more worried about infecting family members, according to the Society for Critical Care Medicine, which surveyed members of four professional organizations – the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and the SCCM – April 7-22, 2020.

Four items in the survey assessed respondents’ level of stress or concern on a scale of 1-10:

- Personal stress before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Personal stress as a result of COVID-19 pandemic.

- Concern about personally being exposed to COVID-19.

- Concern about exposing family members to COVID-19.

Personal stress rose from a median of 3 before the pandemic to a current 8, a level that was equaled by personal concerns about being exposed and surpassed (10) by concerns about exposing family members, the SCCM reported in a blog post.

Most of the respondents “are taking special measures to limit the potential spread of the virus to their loved ones, including implementing a decontamination routine before interacting with families,” the SCCM wrote.

The most common strategy, employed by 72% of ICU clinicians, is changing clothes before/after work. Showering before joining family was mentioned by 64% of providers, followed by limiting contact until decontamination (57%) and using hand sanitizer before entering home (51%), the SCCM said.

More extreme measures included self-isolating within their homes (16%) and staying in alternative housing away from their families (12%), the SCCM said, based on data for 9,120 clinicians in the United States.

Most of the respondents (88%) reported having cared for a patient with confirmed or presumed COVID-19. Nurses made up the majority (91%) of the sample, which also included nurse practitioners and physician assistants (4.5%) and physicians (2.9%), as well as smaller numbers of respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and emergency medicine flight personnel.

The results of the survey “underline the personal sacrifices of critical care clinicians during the COVID-19 response and suggest the need to help them proactively manage stress,” the SCCM wrote.

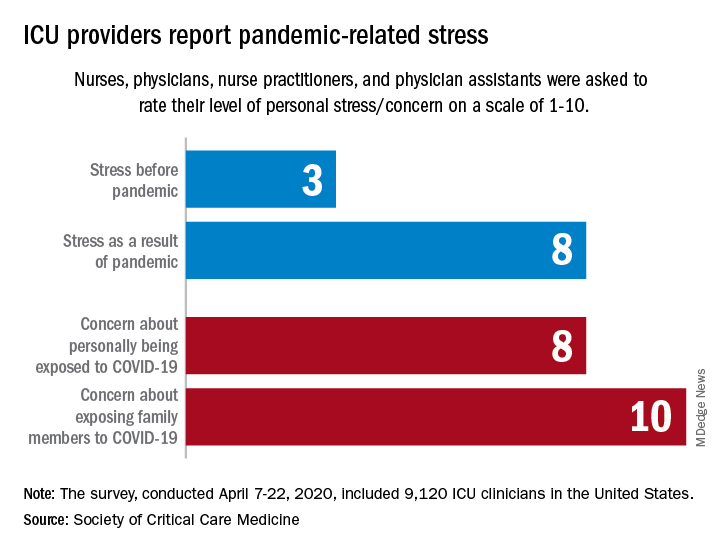

They are worried about getting infected, and they are even more worried about infecting family members, according to the Society for Critical Care Medicine, which surveyed members of four professional organizations – the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and the SCCM – April 7-22, 2020.

Four items in the survey assessed respondents’ level of stress or concern on a scale of 1-10:

- Personal stress before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Personal stress as a result of COVID-19 pandemic.

- Concern about personally being exposed to COVID-19.

- Concern about exposing family members to COVID-19.

Personal stress rose from a median of 3 before the pandemic to a current 8, a level that was equaled by personal concerns about being exposed and surpassed (10) by concerns about exposing family members, the SCCM reported in a blog post.

Most of the respondents “are taking special measures to limit the potential spread of the virus to their loved ones, including implementing a decontamination routine before interacting with families,” the SCCM wrote.

The most common strategy, employed by 72% of ICU clinicians, is changing clothes before/after work. Showering before joining family was mentioned by 64% of providers, followed by limiting contact until decontamination (57%) and using hand sanitizer before entering home (51%), the SCCM said.

More extreme measures included self-isolating within their homes (16%) and staying in alternative housing away from their families (12%), the SCCM said, based on data for 9,120 clinicians in the United States.

Most of the respondents (88%) reported having cared for a patient with confirmed or presumed COVID-19. Nurses made up the majority (91%) of the sample, which also included nurse practitioners and physician assistants (4.5%) and physicians (2.9%), as well as smaller numbers of respiratory therapists, pharmacists, and emergency medicine flight personnel.

The results of the survey “underline the personal sacrifices of critical care clinicians during the COVID-19 response and suggest the need to help them proactively manage stress,” the SCCM wrote.

COVID-19: Eight steps for getting ready to see patients again

After COVID-19 hit the Denver area, internist Jean Kutner, MD, and her clinical colleagues drastically reduced the number of patients they saw and kept a minimum number of people in the office. A small team sees patients who still require in-person visits on one side of the clinic; on the other side, another team conducts clinic-based telehealth visits. A rotating schedule allows for social distancing.

The rest of the practice’s physicians are home, conducting more virtual visits.

Dr. Kutner said she is looking forward to reopening her practice completely at some point. She said she realizes that the practice probably won’t be exactly the same as before.

“We have to embrace the fact that the way we practice medicine has fundamentally changed,” said Dr. Kutner, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and incoming president of the Society of General Internal Medicine. She anticipates keeping many of these changes in place for the foreseeable future.

Nearly half of 2,600 primary care physicians who responded to a recent national survey said they were struggling to remain open during the crisis. Most have had to limit wellness/chronic-disease management visits, and nearly half reported that physicians or staff were out sick. Layoffs, furloughs, and reduced hours are commonplace; some practices were forced to shut down entirely.

Social distancing helps reduce the rates of hospitalizations and deaths.

For example, remote monitoring capabilities have reduced the need for in-person checks of vital signs, such as respiratory rate oxygenation, blood glucose levels, and heart rate. “We can’t go back,” she said.

Dr. Kutner sees the pandemic as an opportunity to innovate, to think about how primary practices can best utilize their resources, face-to-face time with patients, and when and how to best leverage virtual visits in a way that improves patient health. The goal, of course, is to meet the needs of the patients while keeping everyone safe.

Like many physicians in private practice, Dr. Kutner is concerned about revenue. She hopes the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services makes its temporary waivers permanent.

What you need to consider when planning to reopen your office

Physicians say their post-COVID-19 practices will look very different from their prepandemic practices. Many plan to maintain guidelines, such as those from the AAFP, long after the pandemic has peaked.

If you are starting to think about reopening, here are some major considerations.

1. Develop procedures and practices that will keep your patients and staff safe.

“When we return, the first thing we need to do is limit the number of patients in the waiting room,” said Clinton Coleman, MD, who practices internal medicine and nephrology in Teaneck, N.J. “No one is comfortable in a waiting room any longer,” said Dr. Coleman, chief of internal medicine at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck.

Careful planning is required to resume in-person care of patients requiring non-COVID-19 care, as well as all aspects of care, according to the CMS. Adequate staff, testing, supplies, and support services, such as pathology services, are just a few considerations. The CMS recommends that physicians “evaluate the necessity of the care based on clinical needs. Providers should prioritize surgical/procedural care and high-complexity chronic disease management; however, select preventive services may also be highly necessary.”

The American Medical Association recently unveiled a checklist for reopening. One key recommendation was for practices to select a date for reopening the office, ideally preceded by a “soft” or incremental reopening to ensure that new procedures are working. The AMA also recommends opening incrementally, continuing telehealth while also inviting patients back into the office.

2. Figure out how to safely see patients, particularly in your waiting areas and common spaces.

Logistic factors, such as managing patient flow, will change. Waiting rooms will be emptier; in some locations, patients may be asked to wait in their cars until an exam room is available.

The AMA also suggests limiting nonpatient visitors by posting the practice’s policy at the entrance and on the practice’s website. If service calls for repairs are needed, have those visitors come outside of normal operating hours.

Commonly shared objects such magazines or toys in pediatric offices will likely disappear. Wipes, hand sanitizers, and the wearing of masks will become even more commonplace. Those who suspect they’re ill or who have respiratory symptoms may be relegated to specific “sick visit” appointment times or taken to designated exam rooms, which will be thoroughly sanitized between patients.

3. Prepare for routine screening of staff and other facility workers.

According to recent CMS guidelines, you and your staff will need to undergo routine screening, as will others who work in the facility (housekeeping, delivery personnel, and anyone else who enters the area). This may mean regularly stocking screening tests and setting guidelines for what to do if one of your staff tests positive.

You may need to hire temporary workers if your staff tests positive. The CDC recommends at the very least understanding the minimum staffing requirements to ensure good patient care and a safe work environment. Consider adjusting staff schedules and rotating clinical personnel to positions that support patient care activities. You may also want to look into cross-training your office staff so that they can fill in or help out with each other’s responsibilities if one or more persons are ill.

Dr. Kutner is on board with these changes. “We don’t want to get rid of social distancing right away, because it will give us a new spike in cases – how do we figure out patient flow while honoring that?”

4. Develop a strategy for triaging and caring for a potential backlog of patients.

“Many of my partners are scared right now because they have no income except for emergencies,” said Andrew Gonzalez, MD, JD, MPH, a vascular surgeon and assistant professor of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Almost all nonemergency surgery has been put on hold.

“If we don’t operate, the practice makes no money,” he said. He thinks revenue will continue to be a problem as long as patients fear in-person consultations or undergoing surgery for nonacute problems such as hernias.

As restrictions ease, most physicians will face an enormous backlog of patients and will need to find new ways of triaging the most serious cases, he says. Telehealth will help, but Dr. Gonzalez predicts many of his colleagues will be working longer hours and on weekends to catch up. “Physicians are going to have to really think about ways of optimizing their time and workflow to be very efficient, because the backlog is going to prodigious.”

5. Anticipate changes in patient expectations.

This may entail your reconsidering tests and procedures you previously performed and considering developing new sources for some services, phasing some others out, and revising your current approach. It will most likely also mean that you make telemedicine and televisits a greater part of your practice.

Carolyn Kaloostian, MD, a family medicine and geriatric practitioner in Los Angeles, points to increased reliance on community agencies for conducting common office-based procedures, such as performing blood tests and taking ECGs and x-rays. “A lot of patients are using telemedicine or telephone visits and get the lab work or x-rays somewhere that’s less congested,” she said. To become sustainable, many of these changes will hinge on economics – whether and how they are reimbursed.

The pandemic will leave lasting effects in our health care delivery, according to Dr. Kaloostian. She is sure many of her colleagues’ and patients’ current experiences will be infused into future care. “I can’t say we’ll ever be back to normal, necessarily.”

Even if the CMS rolls back its telehealth waivers, some physicians, like Dr. Coleman, plan to continue using the technology extensively. He’s confident about the level of care he’s currently providing patients in his practice. It allows him to better manage many low-income patients who can’t access his office regularly. Not only does splitting his time between the clinic and telehealth allow him to be more available for more patients, he says it also empowers patients to take better care of themselves.

6. Consider a new way to conduct “check-in visits.”

One thing that will likely go by the wayside are “check-in” visits, or so-called “social visits,” those interval appointments that can just as easily be completed virtually. “Patients are going to ask why they need to drive 3 hours so you can tell them their incision looks fine from an operation you did 5 years ago,” Dr. Gonzalez said.

He’s concerned that some people will remain so fearful of the health care system that a formerly busy practice may see the pendulum swing in the opposite direction. If an aneurysm patient skips a visit, that person may also decide not to undergo a CT scan – and something preventable will be missed. “Not everybody has the option to stay away until they feel comfortable. They’re basically playing hot potato. And at some point, the music’s going to stop,” Dr. Gonzalez said.

The pandemic has prompted some very honest conversations with his patients about what truly needs to get done and what may be optional. “Everyone has now become a hyper-rational user of health care,” he said.

7. If you haven’t yet, consider becoming more involved with technology.

In addition to greater use of telehealth, Dr. Kaloostian, assistant professor of clinical family medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, foresees continued reliance upon technology such as smartphone apps that connect with a user’s smartwatch. This allows for more proactive, remote monitoring.

“For example, any time a patient is having recurrent nighttime trips to the bathroom, I’ll get pinged and know that,” she explained. It means she can reach out and ask about any changes before a fall occurs or a condition worsens. “It provides reassurance to the provider and to the patient that you’re doing all you can to keep an eye on them from afar.”

8. Update or reformulate your business plans.

Some physicians in smaller practices may have to temporarily or permanently rethink their situation. Those who have struggled or who have closed down and are considering reopening need to update their business plans. It may be safer economically to become part of a bigger group that is affiliated with an academic center or join a larger health care system that has more funds or resources.

In addition, Dr. Kaloostian suggests that primary care physicians become more flexible in the short term, perhaps working part time in an urgent care clinic or larger organization to gain additional sources of revenue until their own practice finances pick back up.

For offices that reopen, the AMA recommends contacting medical malpractice insurance carriers to check on possible liability concerns. Congress has provided certain protections for clinicians during this time, but malpractice carriers may have more information and may offer more coverage.

Dr. Coleman said a hybrid model of fewer in-person and more telehealth visits “will allow me to practice in a different way.” If the CMS reimposes prior restrictions, reimbursement may be affected initially, but that will likely change once insurers see the increased cost-effectiveness of this approach. Patients with minor complaints, those who need to have medications refilled, and patients with chronic diseases that need managing won’t have to deal with crowded waiting rooms, and it will help mitigate problems with infection control.

If there’s any upside to the pandemic, it’s an increase in attention given to advanced care planning, said Dr. Kutner. It’s something she hopes continues after everyone stops being in crisis mode. “We’re realizing how important it is to have these conversations and document people’s goals and values and code status,” she said.

Are offices likely to open soon?

An assumption that may or may not be valid is that a practice will remain viable and can return to former capacity. Prior to passage of the CARES Act on March 27, a survey from Kareo, a company in Irvine, California, that makes a technology platform for independent physician practices, found that 9% of respondents reported practice closures. Many more reported concern about potential closures as patient office visits plummet because of stay-at-home orders and other concerns.

By mid-April, a survey from the Primary Care Collaborative and the Larry A. Green Center found that 42% of practices had experienced layoffs and had furloughed staff. Most (85%) have seen dramatic decreases in patient volume.

“Reopening the economy or loosening physical distancing restrictions will be difficult when 20% of primary care practices predict closure within 4 weeks,” the survey concluded.

For the practices and the doctors who make it through this, we’re going to probably be better, stronger, and more efficient, Dr. Gonzalez predicts. This shock has uncovered a lot of weaknesses in the American health care system that doctors have known about and have been complaining about for a long time. It will take an open mind and lots of continued flexibility on the part of physicians, hospitals, health care systems, and the government for these changes to stick.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

After COVID-19 hit the Denver area, internist Jean Kutner, MD, and her clinical colleagues drastically reduced the number of patients they saw and kept a minimum number of people in the office. A small team sees patients who still require in-person visits on one side of the clinic; on the other side, another team conducts clinic-based telehealth visits. A rotating schedule allows for social distancing.

The rest of the practice’s physicians are home, conducting more virtual visits.

Dr. Kutner said she is looking forward to reopening her practice completely at some point. She said she realizes that the practice probably won’t be exactly the same as before.

“We have to embrace the fact that the way we practice medicine has fundamentally changed,” said Dr. Kutner, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and incoming president of the Society of General Internal Medicine. She anticipates keeping many of these changes in place for the foreseeable future.

Nearly half of 2,600 primary care physicians who responded to a recent national survey said they were struggling to remain open during the crisis. Most have had to limit wellness/chronic-disease management visits, and nearly half reported that physicians or staff were out sick. Layoffs, furloughs, and reduced hours are commonplace; some practices were forced to shut down entirely.

Social distancing helps reduce the rates of hospitalizations and deaths.

For example, remote monitoring capabilities have reduced the need for in-person checks of vital signs, such as respiratory rate oxygenation, blood glucose levels, and heart rate. “We can’t go back,” she said.

Dr. Kutner sees the pandemic as an opportunity to innovate, to think about how primary practices can best utilize their resources, face-to-face time with patients, and when and how to best leverage virtual visits in a way that improves patient health. The goal, of course, is to meet the needs of the patients while keeping everyone safe.

Like many physicians in private practice, Dr. Kutner is concerned about revenue. She hopes the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services makes its temporary waivers permanent.

What you need to consider when planning to reopen your office

Physicians say their post-COVID-19 practices will look very different from their prepandemic practices. Many plan to maintain guidelines, such as those from the AAFP, long after the pandemic has peaked.

If you are starting to think about reopening, here are some major considerations.

1. Develop procedures and practices that will keep your patients and staff safe.

“When we return, the first thing we need to do is limit the number of patients in the waiting room,” said Clinton Coleman, MD, who practices internal medicine and nephrology in Teaneck, N.J. “No one is comfortable in a waiting room any longer,” said Dr. Coleman, chief of internal medicine at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck.

Careful planning is required to resume in-person care of patients requiring non-COVID-19 care, as well as all aspects of care, according to the CMS. Adequate staff, testing, supplies, and support services, such as pathology services, are just a few considerations. The CMS recommends that physicians “evaluate the necessity of the care based on clinical needs. Providers should prioritize surgical/procedural care and high-complexity chronic disease management; however, select preventive services may also be highly necessary.”

The American Medical Association recently unveiled a checklist for reopening. One key recommendation was for practices to select a date for reopening the office, ideally preceded by a “soft” or incremental reopening to ensure that new procedures are working. The AMA also recommends opening incrementally, continuing telehealth while also inviting patients back into the office.

2. Figure out how to safely see patients, particularly in your waiting areas and common spaces.

Logistic factors, such as managing patient flow, will change. Waiting rooms will be emptier; in some locations, patients may be asked to wait in their cars until an exam room is available.

The AMA also suggests limiting nonpatient visitors by posting the practice’s policy at the entrance and on the practice’s website. If service calls for repairs are needed, have those visitors come outside of normal operating hours.

Commonly shared objects such magazines or toys in pediatric offices will likely disappear. Wipes, hand sanitizers, and the wearing of masks will become even more commonplace. Those who suspect they’re ill or who have respiratory symptoms may be relegated to specific “sick visit” appointment times or taken to designated exam rooms, which will be thoroughly sanitized between patients.

3. Prepare for routine screening of staff and other facility workers.

According to recent CMS guidelines, you and your staff will need to undergo routine screening, as will others who work in the facility (housekeeping, delivery personnel, and anyone else who enters the area). This may mean regularly stocking screening tests and setting guidelines for what to do if one of your staff tests positive.

You may need to hire temporary workers if your staff tests positive. The CDC recommends at the very least understanding the minimum staffing requirements to ensure good patient care and a safe work environment. Consider adjusting staff schedules and rotating clinical personnel to positions that support patient care activities. You may also want to look into cross-training your office staff so that they can fill in or help out with each other’s responsibilities if one or more persons are ill.

Dr. Kutner is on board with these changes. “We don’t want to get rid of social distancing right away, because it will give us a new spike in cases – how do we figure out patient flow while honoring that?”

4. Develop a strategy for triaging and caring for a potential backlog of patients.

“Many of my partners are scared right now because they have no income except for emergencies,” said Andrew Gonzalez, MD, JD, MPH, a vascular surgeon and assistant professor of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Almost all nonemergency surgery has been put on hold.

“If we don’t operate, the practice makes no money,” he said. He thinks revenue will continue to be a problem as long as patients fear in-person consultations or undergoing surgery for nonacute problems such as hernias.

As restrictions ease, most physicians will face an enormous backlog of patients and will need to find new ways of triaging the most serious cases, he says. Telehealth will help, but Dr. Gonzalez predicts many of his colleagues will be working longer hours and on weekends to catch up. “Physicians are going to have to really think about ways of optimizing their time and workflow to be very efficient, because the backlog is going to prodigious.”

5. Anticipate changes in patient expectations.

This may entail your reconsidering tests and procedures you previously performed and considering developing new sources for some services, phasing some others out, and revising your current approach. It will most likely also mean that you make telemedicine and televisits a greater part of your practice.

Carolyn Kaloostian, MD, a family medicine and geriatric practitioner in Los Angeles, points to increased reliance on community agencies for conducting common office-based procedures, such as performing blood tests and taking ECGs and x-rays. “A lot of patients are using telemedicine or telephone visits and get the lab work or x-rays somewhere that’s less congested,” she said. To become sustainable, many of these changes will hinge on economics – whether and how they are reimbursed.

The pandemic will leave lasting effects in our health care delivery, according to Dr. Kaloostian. She is sure many of her colleagues’ and patients’ current experiences will be infused into future care. “I can’t say we’ll ever be back to normal, necessarily.”

Even if the CMS rolls back its telehealth waivers, some physicians, like Dr. Coleman, plan to continue using the technology extensively. He’s confident about the level of care he’s currently providing patients in his practice. It allows him to better manage many low-income patients who can’t access his office regularly. Not only does splitting his time between the clinic and telehealth allow him to be more available for more patients, he says it also empowers patients to take better care of themselves.

6. Consider a new way to conduct “check-in visits.”

One thing that will likely go by the wayside are “check-in” visits, or so-called “social visits,” those interval appointments that can just as easily be completed virtually. “Patients are going to ask why they need to drive 3 hours so you can tell them their incision looks fine from an operation you did 5 years ago,” Dr. Gonzalez said.

He’s concerned that some people will remain so fearful of the health care system that a formerly busy practice may see the pendulum swing in the opposite direction. If an aneurysm patient skips a visit, that person may also decide not to undergo a CT scan – and something preventable will be missed. “Not everybody has the option to stay away until they feel comfortable. They’re basically playing hot potato. And at some point, the music’s going to stop,” Dr. Gonzalez said.

The pandemic has prompted some very honest conversations with his patients about what truly needs to get done and what may be optional. “Everyone has now become a hyper-rational user of health care,” he said.

7. If you haven’t yet, consider becoming more involved with technology.

In addition to greater use of telehealth, Dr. Kaloostian, assistant professor of clinical family medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, foresees continued reliance upon technology such as smartphone apps that connect with a user’s smartwatch. This allows for more proactive, remote monitoring.

“For example, any time a patient is having recurrent nighttime trips to the bathroom, I’ll get pinged and know that,” she explained. It means she can reach out and ask about any changes before a fall occurs or a condition worsens. “It provides reassurance to the provider and to the patient that you’re doing all you can to keep an eye on them from afar.”

8. Update or reformulate your business plans.

Some physicians in smaller practices may have to temporarily or permanently rethink their situation. Those who have struggled or who have closed down and are considering reopening need to update their business plans. It may be safer economically to become part of a bigger group that is affiliated with an academic center or join a larger health care system that has more funds or resources.

In addition, Dr. Kaloostian suggests that primary care physicians become more flexible in the short term, perhaps working part time in an urgent care clinic or larger organization to gain additional sources of revenue until their own practice finances pick back up.

For offices that reopen, the AMA recommends contacting medical malpractice insurance carriers to check on possible liability concerns. Congress has provided certain protections for clinicians during this time, but malpractice carriers may have more information and may offer more coverage.

Dr. Coleman said a hybrid model of fewer in-person and more telehealth visits “will allow me to practice in a different way.” If the CMS reimposes prior restrictions, reimbursement may be affected initially, but that will likely change once insurers see the increased cost-effectiveness of this approach. Patients with minor complaints, those who need to have medications refilled, and patients with chronic diseases that need managing won’t have to deal with crowded waiting rooms, and it will help mitigate problems with infection control.

If there’s any upside to the pandemic, it’s an increase in attention given to advanced care planning, said Dr. Kutner. It’s something she hopes continues after everyone stops being in crisis mode. “We’re realizing how important it is to have these conversations and document people’s goals and values and code status,” she said.

Are offices likely to open soon?

An assumption that may or may not be valid is that a practice will remain viable and can return to former capacity. Prior to passage of the CARES Act on March 27, a survey from Kareo, a company in Irvine, California, that makes a technology platform for independent physician practices, found that 9% of respondents reported practice closures. Many more reported concern about potential closures as patient office visits plummet because of stay-at-home orders and other concerns.

By mid-April, a survey from the Primary Care Collaborative and the Larry A. Green Center found that 42% of practices had experienced layoffs and had furloughed staff. Most (85%) have seen dramatic decreases in patient volume.

“Reopening the economy or loosening physical distancing restrictions will be difficult when 20% of primary care practices predict closure within 4 weeks,” the survey concluded.

For the practices and the doctors who make it through this, we’re going to probably be better, stronger, and more efficient, Dr. Gonzalez predicts. This shock has uncovered a lot of weaknesses in the American health care system that doctors have known about and have been complaining about for a long time. It will take an open mind and lots of continued flexibility on the part of physicians, hospitals, health care systems, and the government for these changes to stick.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

After COVID-19 hit the Denver area, internist Jean Kutner, MD, and her clinical colleagues drastically reduced the number of patients they saw and kept a minimum number of people in the office. A small team sees patients who still require in-person visits on one side of the clinic; on the other side, another team conducts clinic-based telehealth visits. A rotating schedule allows for social distancing.

The rest of the practice’s physicians are home, conducting more virtual visits.

Dr. Kutner said she is looking forward to reopening her practice completely at some point. She said she realizes that the practice probably won’t be exactly the same as before.

“We have to embrace the fact that the way we practice medicine has fundamentally changed,” said Dr. Kutner, professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and incoming president of the Society of General Internal Medicine. She anticipates keeping many of these changes in place for the foreseeable future.

Nearly half of 2,600 primary care physicians who responded to a recent national survey said they were struggling to remain open during the crisis. Most have had to limit wellness/chronic-disease management visits, and nearly half reported that physicians or staff were out sick. Layoffs, furloughs, and reduced hours are commonplace; some practices were forced to shut down entirely.

Social distancing helps reduce the rates of hospitalizations and deaths.

For example, remote monitoring capabilities have reduced the need for in-person checks of vital signs, such as respiratory rate oxygenation, blood glucose levels, and heart rate. “We can’t go back,” she said.

Dr. Kutner sees the pandemic as an opportunity to innovate, to think about how primary practices can best utilize their resources, face-to-face time with patients, and when and how to best leverage virtual visits in a way that improves patient health. The goal, of course, is to meet the needs of the patients while keeping everyone safe.

Like many physicians in private practice, Dr. Kutner is concerned about revenue. She hopes the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services makes its temporary waivers permanent.

What you need to consider when planning to reopen your office

Physicians say their post-COVID-19 practices will look very different from their prepandemic practices. Many plan to maintain guidelines, such as those from the AAFP, long after the pandemic has peaked.

If you are starting to think about reopening, here are some major considerations.

1. Develop procedures and practices that will keep your patients and staff safe.

“When we return, the first thing we need to do is limit the number of patients in the waiting room,” said Clinton Coleman, MD, who practices internal medicine and nephrology in Teaneck, N.J. “No one is comfortable in a waiting room any longer,” said Dr. Coleman, chief of internal medicine at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck.

Careful planning is required to resume in-person care of patients requiring non-COVID-19 care, as well as all aspects of care, according to the CMS. Adequate staff, testing, supplies, and support services, such as pathology services, are just a few considerations. The CMS recommends that physicians “evaluate the necessity of the care based on clinical needs. Providers should prioritize surgical/procedural care and high-complexity chronic disease management; however, select preventive services may also be highly necessary.”

The American Medical Association recently unveiled a checklist for reopening. One key recommendation was for practices to select a date for reopening the office, ideally preceded by a “soft” or incremental reopening to ensure that new procedures are working. The AMA also recommends opening incrementally, continuing telehealth while also inviting patients back into the office.

2. Figure out how to safely see patients, particularly in your waiting areas and common spaces.

Logistic factors, such as managing patient flow, will change. Waiting rooms will be emptier; in some locations, patients may be asked to wait in their cars until an exam room is available.

The AMA also suggests limiting nonpatient visitors by posting the practice’s policy at the entrance and on the practice’s website. If service calls for repairs are needed, have those visitors come outside of normal operating hours.

Commonly shared objects such magazines or toys in pediatric offices will likely disappear. Wipes, hand sanitizers, and the wearing of masks will become even more commonplace. Those who suspect they’re ill or who have respiratory symptoms may be relegated to specific “sick visit” appointment times or taken to designated exam rooms, which will be thoroughly sanitized between patients.

3. Prepare for routine screening of staff and other facility workers.

According to recent CMS guidelines, you and your staff will need to undergo routine screening, as will others who work in the facility (housekeeping, delivery personnel, and anyone else who enters the area). This may mean regularly stocking screening tests and setting guidelines for what to do if one of your staff tests positive.

You may need to hire temporary workers if your staff tests positive. The CDC recommends at the very least understanding the minimum staffing requirements to ensure good patient care and a safe work environment. Consider adjusting staff schedules and rotating clinical personnel to positions that support patient care activities. You may also want to look into cross-training your office staff so that they can fill in or help out with each other’s responsibilities if one or more persons are ill.

Dr. Kutner is on board with these changes. “We don’t want to get rid of social distancing right away, because it will give us a new spike in cases – how do we figure out patient flow while honoring that?”

4. Develop a strategy for triaging and caring for a potential backlog of patients.

“Many of my partners are scared right now because they have no income except for emergencies,” said Andrew Gonzalez, MD, JD, MPH, a vascular surgeon and assistant professor of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis. Almost all nonemergency surgery has been put on hold.

“If we don’t operate, the practice makes no money,” he said. He thinks revenue will continue to be a problem as long as patients fear in-person consultations or undergoing surgery for nonacute problems such as hernias.

As restrictions ease, most physicians will face an enormous backlog of patients and will need to find new ways of triaging the most serious cases, he says. Telehealth will help, but Dr. Gonzalez predicts many of his colleagues will be working longer hours and on weekends to catch up. “Physicians are going to have to really think about ways of optimizing their time and workflow to be very efficient, because the backlog is going to prodigious.”

5. Anticipate changes in patient expectations.

This may entail your reconsidering tests and procedures you previously performed and considering developing new sources for some services, phasing some others out, and revising your current approach. It will most likely also mean that you make telemedicine and televisits a greater part of your practice.

Carolyn Kaloostian, MD, a family medicine and geriatric practitioner in Los Angeles, points to increased reliance on community agencies for conducting common office-based procedures, such as performing blood tests and taking ECGs and x-rays. “A lot of patients are using telemedicine or telephone visits and get the lab work or x-rays somewhere that’s less congested,” she said. To become sustainable, many of these changes will hinge on economics – whether and how they are reimbursed.

The pandemic will leave lasting effects in our health care delivery, according to Dr. Kaloostian. She is sure many of her colleagues’ and patients’ current experiences will be infused into future care. “I can’t say we’ll ever be back to normal, necessarily.”

Even if the CMS rolls back its telehealth waivers, some physicians, like Dr. Coleman, plan to continue using the technology extensively. He’s confident about the level of care he’s currently providing patients in his practice. It allows him to better manage many low-income patients who can’t access his office regularly. Not only does splitting his time between the clinic and telehealth allow him to be more available for more patients, he says it also empowers patients to take better care of themselves.

6. Consider a new way to conduct “check-in visits.”

One thing that will likely go by the wayside are “check-in” visits, or so-called “social visits,” those interval appointments that can just as easily be completed virtually. “Patients are going to ask why they need to drive 3 hours so you can tell them their incision looks fine from an operation you did 5 years ago,” Dr. Gonzalez said.

He’s concerned that some people will remain so fearful of the health care system that a formerly busy practice may see the pendulum swing in the opposite direction. If an aneurysm patient skips a visit, that person may also decide not to undergo a CT scan – and something preventable will be missed. “Not everybody has the option to stay away until they feel comfortable. They’re basically playing hot potato. And at some point, the music’s going to stop,” Dr. Gonzalez said.

The pandemic has prompted some very honest conversations with his patients about what truly needs to get done and what may be optional. “Everyone has now become a hyper-rational user of health care,” he said.

7. If you haven’t yet, consider becoming more involved with technology.

In addition to greater use of telehealth, Dr. Kaloostian, assistant professor of clinical family medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, foresees continued reliance upon technology such as smartphone apps that connect with a user’s smartwatch. This allows for more proactive, remote monitoring.

“For example, any time a patient is having recurrent nighttime trips to the bathroom, I’ll get pinged and know that,” she explained. It means she can reach out and ask about any changes before a fall occurs or a condition worsens. “It provides reassurance to the provider and to the patient that you’re doing all you can to keep an eye on them from afar.”

8. Update or reformulate your business plans.

Some physicians in smaller practices may have to temporarily or permanently rethink their situation. Those who have struggled or who have closed down and are considering reopening need to update their business plans. It may be safer economically to become part of a bigger group that is affiliated with an academic center or join a larger health care system that has more funds or resources.

In addition, Dr. Kaloostian suggests that primary care physicians become more flexible in the short term, perhaps working part time in an urgent care clinic or larger organization to gain additional sources of revenue until their own practice finances pick back up.

For offices that reopen, the AMA recommends contacting medical malpractice insurance carriers to check on possible liability concerns. Congress has provided certain protections for clinicians during this time, but malpractice carriers may have more information and may offer more coverage.

Dr. Coleman said a hybrid model of fewer in-person and more telehealth visits “will allow me to practice in a different way.” If the CMS reimposes prior restrictions, reimbursement may be affected initially, but that will likely change once insurers see the increased cost-effectiveness of this approach. Patients with minor complaints, those who need to have medications refilled, and patients with chronic diseases that need managing won’t have to deal with crowded waiting rooms, and it will help mitigate problems with infection control.

If there’s any upside to the pandemic, it’s an increase in attention given to advanced care planning, said Dr. Kutner. It’s something she hopes continues after everyone stops being in crisis mode. “We’re realizing how important it is to have these conversations and document people’s goals and values and code status,” she said.

Are offices likely to open soon?

An assumption that may or may not be valid is that a practice will remain viable and can return to former capacity. Prior to passage of the CARES Act on March 27, a survey from Kareo, a company in Irvine, California, that makes a technology platform for independent physician practices, found that 9% of respondents reported practice closures. Many more reported concern about potential closures as patient office visits plummet because of stay-at-home orders and other concerns.

By mid-April, a survey from the Primary Care Collaborative and the Larry A. Green Center found that 42% of practices had experienced layoffs and had furloughed staff. Most (85%) have seen dramatic decreases in patient volume.

“Reopening the economy or loosening physical distancing restrictions will be difficult when 20% of primary care practices predict closure within 4 weeks,” the survey concluded.

For the practices and the doctors who make it through this, we’re going to probably be better, stronger, and more efficient, Dr. Gonzalez predicts. This shock has uncovered a lot of weaknesses in the American health care system that doctors have known about and have been complaining about for a long time. It will take an open mind and lots of continued flexibility on the part of physicians, hospitals, health care systems, and the government for these changes to stick.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

More guidance on inpatient management of blood glucose in COVID-19

“The glycemic management of many COVID-19–positive patients with diabetes is proving extremely complex, with huge fluctuations in glucose control and the need for very high doses of insulin,” says Diabetes UK’s National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team.

“Intravenous infusion pumps, also required for inotropes, are at a premium and there may be the need to consider the use of subcutaneous or intramuscular insulin protocols,” they note.

Updated as of April 29, all of the information of the National Diabetes Inpatient COVID Response Team is available on the Diabetes UK website.

The new inpatient management graphic adds more detail to the previous “front-door” guidance, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The document stressed that, as well as identifying patients with known diabetes, it is imperative that all newly admitted patients with COVID-19 are evaluated for diabetes, as the infection is known to cause new-onset diabetes.

Subcutaneous insulin dosing

The new graphic gives extensive details on subcutaneous insulin dosing in place of variable rate intravenous insulin when infusion pumps are not available, and when the patient has a glucose level above 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) but does not have DKA or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

However, the advice is not intended for people with COVID-19 causing severe insulin resistance in the intensive care unit.

The other new guidance graphic on managing DKA or hyperosmolar state in people with COVID-19 using subcutaneous insulin is also intended for situations where intravenous infusion isn’t available.

Seek help from specialist diabetes team when needed