User login

Tinzaparin is a safe, effective anticoagulant in patients on dialysis

CHICAGO – Tinzaparin was safe and effective as an anticoagulant for hemodialysis patients based on results from the Intermittent Hemodialysis Anticoagulation with Tinzaparin (HEMO-TIN) trial presented at the annual meeting sponsored by the American Society for Nephrology.

In the multicenter randomized controlled trial of 192 adults on hemodialysis, tinzaparin, a low molecular weight heparin with antithrombotic properties, was compared with unfractionated heparin. Tinzaparin has been considered for hemodialysis patients because it is thought to be less dependent on renal clearance than are other low molecular weight heparins, Christine Ribic, MD, MSc, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in reporting the results.

After 3 months, the 78 patients remaining in the tinzaparin group crossed over to receive unfractionated heparin for 3 months. The 79 patients remaining in the unfractionated heparin group crossed over to receive tinzaparin for 3 months. Of these 156 patients, 125 completed the 3-month crossover phase.

There were 421 bleeding events in the 12,125 hemodialysis sessions studied. They were evenly distributed in the groups, with 212 (50.4%) in those receiving unfractionated heparin and 209 (49.6%) in those receiving tinzaparin. The prevalence of major bleeds (2.1 vs 1.6%), clinically important nonmajor bleeds (1.2% vs 0.2%), and minor bleeds (47.0% vs 47.7%) was also similar between the unfractionated heparin and tinzaparin groups.

Anti-Xa heparin levels were used as a surrogate measure of low molecular weight heparin activity levels and bleeding risk due to bioaccumulation. In tinzaparin-treated patients, anti-Xa heparin levels never exceeded a value of 0.2 either before or after dialysis. This value was considered the threshold between safety and increased risk for bleeding. This threshold level was routinely exceeded pre- and post-dialysis in patients receiving unfractionated heparin at baseline and both before and after crossover.

Grade 4 clotting was similar for tinzaparin and unfractionated heparin, occurring in 23 of 6,095 (0.4%) unfractionated heparin hemodialysis sessions and 41 of 6030 (0.7%) tinzaparin hemodialysis sessions. Mean dialyzer clotting scores and mean air trap clotting scores were also comparable.

The trial was supported by Leo Pharma, the maker of tinzaparin (innohep), in collaboration with McMaster University. Dr. Ribic is the sponsor of the trial.

CHICAGO – Tinzaparin was safe and effective as an anticoagulant for hemodialysis patients based on results from the Intermittent Hemodialysis Anticoagulation with Tinzaparin (HEMO-TIN) trial presented at the annual meeting sponsored by the American Society for Nephrology.

In the multicenter randomized controlled trial of 192 adults on hemodialysis, tinzaparin, a low molecular weight heparin with antithrombotic properties, was compared with unfractionated heparin. Tinzaparin has been considered for hemodialysis patients because it is thought to be less dependent on renal clearance than are other low molecular weight heparins, Christine Ribic, MD, MSc, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in reporting the results.

After 3 months, the 78 patients remaining in the tinzaparin group crossed over to receive unfractionated heparin for 3 months. The 79 patients remaining in the unfractionated heparin group crossed over to receive tinzaparin for 3 months. Of these 156 patients, 125 completed the 3-month crossover phase.

There were 421 bleeding events in the 12,125 hemodialysis sessions studied. They were evenly distributed in the groups, with 212 (50.4%) in those receiving unfractionated heparin and 209 (49.6%) in those receiving tinzaparin. The prevalence of major bleeds (2.1 vs 1.6%), clinically important nonmajor bleeds (1.2% vs 0.2%), and minor bleeds (47.0% vs 47.7%) was also similar between the unfractionated heparin and tinzaparin groups.

Anti-Xa heparin levels were used as a surrogate measure of low molecular weight heparin activity levels and bleeding risk due to bioaccumulation. In tinzaparin-treated patients, anti-Xa heparin levels never exceeded a value of 0.2 either before or after dialysis. This value was considered the threshold between safety and increased risk for bleeding. This threshold level was routinely exceeded pre- and post-dialysis in patients receiving unfractionated heparin at baseline and both before and after crossover.

Grade 4 clotting was similar for tinzaparin and unfractionated heparin, occurring in 23 of 6,095 (0.4%) unfractionated heparin hemodialysis sessions and 41 of 6030 (0.7%) tinzaparin hemodialysis sessions. Mean dialyzer clotting scores and mean air trap clotting scores were also comparable.

The trial was supported by Leo Pharma, the maker of tinzaparin (innohep), in collaboration with McMaster University. Dr. Ribic is the sponsor of the trial.

CHICAGO – Tinzaparin was safe and effective as an anticoagulant for hemodialysis patients based on results from the Intermittent Hemodialysis Anticoagulation with Tinzaparin (HEMO-TIN) trial presented at the annual meeting sponsored by the American Society for Nephrology.

In the multicenter randomized controlled trial of 192 adults on hemodialysis, tinzaparin, a low molecular weight heparin with antithrombotic properties, was compared with unfractionated heparin. Tinzaparin has been considered for hemodialysis patients because it is thought to be less dependent on renal clearance than are other low molecular weight heparins, Christine Ribic, MD, MSc, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said in reporting the results.

After 3 months, the 78 patients remaining in the tinzaparin group crossed over to receive unfractionated heparin for 3 months. The 79 patients remaining in the unfractionated heparin group crossed over to receive tinzaparin for 3 months. Of these 156 patients, 125 completed the 3-month crossover phase.

There were 421 bleeding events in the 12,125 hemodialysis sessions studied. They were evenly distributed in the groups, with 212 (50.4%) in those receiving unfractionated heparin and 209 (49.6%) in those receiving tinzaparin. The prevalence of major bleeds (2.1 vs 1.6%), clinically important nonmajor bleeds (1.2% vs 0.2%), and minor bleeds (47.0% vs 47.7%) was also similar between the unfractionated heparin and tinzaparin groups.

Anti-Xa heparin levels were used as a surrogate measure of low molecular weight heparin activity levels and bleeding risk due to bioaccumulation. In tinzaparin-treated patients, anti-Xa heparin levels never exceeded a value of 0.2 either before or after dialysis. This value was considered the threshold between safety and increased risk for bleeding. This threshold level was routinely exceeded pre- and post-dialysis in patients receiving unfractionated heparin at baseline and both before and after crossover.

Grade 4 clotting was similar for tinzaparin and unfractionated heparin, occurring in 23 of 6,095 (0.4%) unfractionated heparin hemodialysis sessions and 41 of 6030 (0.7%) tinzaparin hemodialysis sessions. Mean dialyzer clotting scores and mean air trap clotting scores were also comparable.

The trial was supported by Leo Pharma, the maker of tinzaparin (innohep), in collaboration with McMaster University. Dr. Ribic is the sponsor of the trial.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2016

Key clinical point: Tinzaparin outcomes compare to those with low molecular weight heparin, and tinzaparin may be safer because it is less dependent on renal clearance than are low molecular weight heparins.

Major finding: Mean anti-Xa levels post-hemodialysis did not exceed 0.2 for tinzaparin, indicating no residual anticoagulant effect.

Data source: Randomized, double-dummy, blinded crossover controlled trial involving 192 patients.

Disclosures: Study sponsor was McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. The study was funded by Leo Pharma. Dr. Ribic reported having no financial disclosures.

Liraglutide lessens risk of kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes

CHICAGO – Liraglutide reduced the risk of kidney disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes, a study showed.

The latest results from the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial build on the previously reported success of liraglutide in reducing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes.

“We now have drugs that not only lower blood sugar but also have an impact on new development of diabetic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease,” said Johannes Mann, MD, of the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany, in a plenary presentation at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The LEADER trial involved people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (mean duration, about 13 years) with a baseline hemoglobin A1c level greater than or equal to 7%. Some had never taken antidiabetic drugs, and some were taking oral antidiabetic drugs and/or basal/premixed insulin. They were either 50 years of age or older with established cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease, or 60 years and older with risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Exclusion criteria included type 1 diabetes; a history of medication with glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors, pramlintide, or rapid-acting insulin; and a family/personal history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 or medullary thyroid cancer.

The 9,340 subjects were randomized in a double-blind fashion to daily subcutaneous injection with 0.6-1.8 mg of liraglutide (4,668) or placebo (4,672) for at least 3.5 years to a maximum treatment time of 5 years. The mean follow-up was 3.8 years.

At baseline, microalbuminuria had been diagnosed in 26.4% and 26.6% of those randomized to liraglutide or placebo, respectively. The respective baseline rates of macroalbuminuria were 10% and 11%. An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was present in 23.9% of the liraglutide group and 22.3% of the control group.

In this analysis of the LEADER results, the primary renal outcome was a composite of the development of macroalbuminuria, doubling of serum creatinine, end-stage renal disease, or renal death. Liraglutide was superior to placebo in delaying the time to the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-0.92; P equal to .003). The outcome was driven by the reduction in development of macroalbuminuria (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60-0.91; P = .004), with treatment not being significantly effective for doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.67-1.19) or the need for dialysis (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.61-1.24).

The eGFR declined less in the liraglutide arm. The renal protection of the drug was restricted to subjects with a baseline eGFR of 30-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Liragutide was not associated with an increased risk of adverse renal events.

The latest results extend the potential indications of the therapeutic prowess of liraglutide in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic kidney disease, with the caveat that the significance of the primary outcome was due to macroalbuminuria rather than the arguably more important outcomes of doubling of serum creatinine and development of end-stage renal disease.

The trial was sponsored and funded by Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide (Victoza) and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mann disclosed financial relationships with various drug companies, including Novo Nordisk.

CHICAGO – Liraglutide reduced the risk of kidney disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes, a study showed.

The latest results from the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial build on the previously reported success of liraglutide in reducing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes.

“We now have drugs that not only lower blood sugar but also have an impact on new development of diabetic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease,” said Johannes Mann, MD, of the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany, in a plenary presentation at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The LEADER trial involved people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (mean duration, about 13 years) with a baseline hemoglobin A1c level greater than or equal to 7%. Some had never taken antidiabetic drugs, and some were taking oral antidiabetic drugs and/or basal/premixed insulin. They were either 50 years of age or older with established cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease, or 60 years and older with risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Exclusion criteria included type 1 diabetes; a history of medication with glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors, pramlintide, or rapid-acting insulin; and a family/personal history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 or medullary thyroid cancer.

The 9,340 subjects were randomized in a double-blind fashion to daily subcutaneous injection with 0.6-1.8 mg of liraglutide (4,668) or placebo (4,672) for at least 3.5 years to a maximum treatment time of 5 years. The mean follow-up was 3.8 years.

At baseline, microalbuminuria had been diagnosed in 26.4% and 26.6% of those randomized to liraglutide or placebo, respectively. The respective baseline rates of macroalbuminuria were 10% and 11%. An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was present in 23.9% of the liraglutide group and 22.3% of the control group.

In this analysis of the LEADER results, the primary renal outcome was a composite of the development of macroalbuminuria, doubling of serum creatinine, end-stage renal disease, or renal death. Liraglutide was superior to placebo in delaying the time to the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-0.92; P equal to .003). The outcome was driven by the reduction in development of macroalbuminuria (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60-0.91; P = .004), with treatment not being significantly effective for doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.67-1.19) or the need for dialysis (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.61-1.24).

The eGFR declined less in the liraglutide arm. The renal protection of the drug was restricted to subjects with a baseline eGFR of 30-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Liragutide was not associated with an increased risk of adverse renal events.

The latest results extend the potential indications of the therapeutic prowess of liraglutide in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic kidney disease, with the caveat that the significance of the primary outcome was due to macroalbuminuria rather than the arguably more important outcomes of doubling of serum creatinine and development of end-stage renal disease.

The trial was sponsored and funded by Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide (Victoza) and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mann disclosed financial relationships with various drug companies, including Novo Nordisk.

CHICAGO – Liraglutide reduced the risk of kidney disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetes, a study showed.

The latest results from the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial build on the previously reported success of liraglutide in reducing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes.

“We now have drugs that not only lower blood sugar but also have an impact on new development of diabetic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease,” said Johannes Mann, MD, of the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany, in a plenary presentation at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The LEADER trial involved people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (mean duration, about 13 years) with a baseline hemoglobin A1c level greater than or equal to 7%. Some had never taken antidiabetic drugs, and some were taking oral antidiabetic drugs and/or basal/premixed insulin. They were either 50 years of age or older with established cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease, or 60 years and older with risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Exclusion criteria included type 1 diabetes; a history of medication with glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitors, pramlintide, or rapid-acting insulin; and a family/personal history of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 or medullary thyroid cancer.

The 9,340 subjects were randomized in a double-blind fashion to daily subcutaneous injection with 0.6-1.8 mg of liraglutide (4,668) or placebo (4,672) for at least 3.5 years to a maximum treatment time of 5 years. The mean follow-up was 3.8 years.

At baseline, microalbuminuria had been diagnosed in 26.4% and 26.6% of those randomized to liraglutide or placebo, respectively. The respective baseline rates of macroalbuminuria were 10% and 11%. An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 was present in 23.9% of the liraglutide group and 22.3% of the control group.

In this analysis of the LEADER results, the primary renal outcome was a composite of the development of macroalbuminuria, doubling of serum creatinine, end-stage renal disease, or renal death. Liraglutide was superior to placebo in delaying the time to the primary outcome (hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-0.92; P equal to .003). The outcome was driven by the reduction in development of macroalbuminuria (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60-0.91; P = .004), with treatment not being significantly effective for doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.67-1.19) or the need for dialysis (HR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.61-1.24).

The eGFR declined less in the liraglutide arm. The renal protection of the drug was restricted to subjects with a baseline eGFR of 30-59 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Liragutide was not associated with an increased risk of adverse renal events.

The latest results extend the potential indications of the therapeutic prowess of liraglutide in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic kidney disease, with the caveat that the significance of the primary outcome was due to macroalbuminuria rather than the arguably more important outcomes of doubling of serum creatinine and development of end-stage renal disease.

The trial was sponsored and funded by Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide (Victoza) and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mann disclosed financial relationships with various drug companies, including Novo Nordisk.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Liraglutide significantly lessened all-cause death, compared with placebo.

Data source: LEADER, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial involving 9,340 patients.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored and funded by Novo Nordisk, the maker of liraglutide (Victoza) and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mann disclosed financial relationships with various drug companies, including Novo Nordisk.

AURA-LV study: Rapid remission with voclosporin for lupus nephritis

WASHINGTON – The investigational calcineurin inhibitor voclosporin, given in addition to mycophenolate mofetil and low-dose steroids, was associated with rapid and complete remissions in lupus nephritis patients in the randomized, controlled AURA-LV study.

Aurinia Urinary Protein Reduction Active – Lupus With Voclosporin (AURA-LV) included 265 subjects in over 20 countries with active lupus nephritis. Trial participants received low-dose voclosporin (23.7 mg b.i.d.) or high-dose voclosporin (39.5 mg b.i.d.) in addition to mycophenolate mofetil (2 g/day) and low-dose steroids. Patients began on 20-25 mg of a steroid with a taper to 5 mg at week 8 and 2.5 mg at week 16-24.

Complete remission occurred at 24 weeks in 32.6% of 89 subjects who received 23.7 mg of voclosporin twice daily and standard of care therapy and in 19.3% of 88 control subjects who received placebo and standard of care therapy (odds ratio, 2.03), Mary Anne Dooley, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The complete remission rate was 27.3% in the 88 subjects who received the higher dose (39.5 mg b.i.d.) of voclosporin. The difference between the high-dose voclosporin group and the control group was not statistically significant.

The “very exciting findings” of this study – the first lupus nephritis study to meet its primary endpoint of complete remission – are important, because “partial remission is insufficient for our patients,” she said.

“Clinical trials over the past 10 years have really shown that we’re not reaching a large group of patients. ... more than 40% of patients are complete nonresponders at 6 months,” she said. While attainment of partial remission has improved, half of those who achieve partial remission have been shown to have a 50% increase in the risk of end-stage renal disease in 10 years.

Complete remission was defined as urine protein/creatinine ratio of no more than 0.5 mg/mg using first morning void with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of at least 60 mL/min without a decrease of 20% or more, sustained low-dose steroids (at or below 10 mg/day) and no use of rescue medications.

Partial remission was a composite of reduction in protein/creatinine ratio of at least 50%, no use of rescue medication, and stability of renal function. Both the low- and high-dose voclosporin groups had outcomes that were superior to standard-of-care therapy, with 69.7% partial remission with low-dose voclosporin, 65.9% partial remission with high-dose voclosporin, and 49.4% partial remission with placebo, said Dr. Dooley, a rheumatologist in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“Patients began responding literally within weeks [to voclosporin] ... and we saw significant responses by 7-8 weeks. This was during the time period when the steroids rapidly decreased,” she said, noting that the steroid dosing at baseline was a median of 25 mg vs. 2.5 mg at 16 weeks.

Study subjects met ACR criteria for lupus and had biopsy-proven lupus nephritis, including proliferative nephritis class III/IV or class V alone or in combination with proliferative disease. All were treated with 2 g/day of mycophenolate mofetil, and the steroid taper “was such that by 10 weeks, patients were down to 5 mg, and that by 24 weeks the median dose was 2.5 mg,” she said.

Adverse events, most commonly infection and gastrointestinal disorders, occurred in 90% of study subjects. Infections occurred in 56.2% of those in the low-dose group, 63.6% of those in the high-dose group, and 50% of controls. GI disorders occurred in 41.6%, 52.3%, and 36.4% of patients in the groups, respectively.

Serious adverse events were more common in the voclosporin groups, occurring in 25.8% and 25% of patients in the low- and high-dose groups, respectively, compared with 15.8% of patients in the control group.

Ten of the 13 deaths occurred in the low-dose voclosporin group (3 due to infection, 3 due to thromboembolism, and 4 due to “other” causes); 2 occurred in the high-dose voclosporin group (1 each due to infection and thromboembolism); and 1 death due to thromboembolism occurred in the control group. As most of the deaths were clustered in the low-dose arm, and 11 of the 13 deaths occurred in areas with “compromised access to standard of care,” the deaths were not considered to be directly related to voclosporin therapy.

Patients who died had “a statistically different clinical baseline picture with higher levels of proteinuria or difficulty with comorbid conditions and some signs of poor nutrition,” Dr. Dooley said.

The findings of the study will be used as the basis for planned subsequent studies of the use of voclosporin in lupus nephritis, she said.

Voclosporin is an analogue of cyclosporin A that may allow flat dosing and a potentially improved safety profile compared with other calcineurin inhibitors.

Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, the maker of voclosporin, announced in early November 2016 that the twice-daily 23.7 mg voclosporin dose will advance to a global 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study in the second quarter of 2017. Voclosporin has already received fast track designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Dooley reported a financial relationship with Aurinia, which sponsored the study.

WASHINGTON – The investigational calcineurin inhibitor voclosporin, given in addition to mycophenolate mofetil and low-dose steroids, was associated with rapid and complete remissions in lupus nephritis patients in the randomized, controlled AURA-LV study.

Aurinia Urinary Protein Reduction Active – Lupus With Voclosporin (AURA-LV) included 265 subjects in over 20 countries with active lupus nephritis. Trial participants received low-dose voclosporin (23.7 mg b.i.d.) or high-dose voclosporin (39.5 mg b.i.d.) in addition to mycophenolate mofetil (2 g/day) and low-dose steroids. Patients began on 20-25 mg of a steroid with a taper to 5 mg at week 8 and 2.5 mg at week 16-24.

Complete remission occurred at 24 weeks in 32.6% of 89 subjects who received 23.7 mg of voclosporin twice daily and standard of care therapy and in 19.3% of 88 control subjects who received placebo and standard of care therapy (odds ratio, 2.03), Mary Anne Dooley, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The complete remission rate was 27.3% in the 88 subjects who received the higher dose (39.5 mg b.i.d.) of voclosporin. The difference between the high-dose voclosporin group and the control group was not statistically significant.

The “very exciting findings” of this study – the first lupus nephritis study to meet its primary endpoint of complete remission – are important, because “partial remission is insufficient for our patients,” she said.

“Clinical trials over the past 10 years have really shown that we’re not reaching a large group of patients. ... more than 40% of patients are complete nonresponders at 6 months,” she said. While attainment of partial remission has improved, half of those who achieve partial remission have been shown to have a 50% increase in the risk of end-stage renal disease in 10 years.

Complete remission was defined as urine protein/creatinine ratio of no more than 0.5 mg/mg using first morning void with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of at least 60 mL/min without a decrease of 20% or more, sustained low-dose steroids (at or below 10 mg/day) and no use of rescue medications.

Partial remission was a composite of reduction in protein/creatinine ratio of at least 50%, no use of rescue medication, and stability of renal function. Both the low- and high-dose voclosporin groups had outcomes that were superior to standard-of-care therapy, with 69.7% partial remission with low-dose voclosporin, 65.9% partial remission with high-dose voclosporin, and 49.4% partial remission with placebo, said Dr. Dooley, a rheumatologist in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“Patients began responding literally within weeks [to voclosporin] ... and we saw significant responses by 7-8 weeks. This was during the time period when the steroids rapidly decreased,” she said, noting that the steroid dosing at baseline was a median of 25 mg vs. 2.5 mg at 16 weeks.

Study subjects met ACR criteria for lupus and had biopsy-proven lupus nephritis, including proliferative nephritis class III/IV or class V alone or in combination with proliferative disease. All were treated with 2 g/day of mycophenolate mofetil, and the steroid taper “was such that by 10 weeks, patients were down to 5 mg, and that by 24 weeks the median dose was 2.5 mg,” she said.

Adverse events, most commonly infection and gastrointestinal disorders, occurred in 90% of study subjects. Infections occurred in 56.2% of those in the low-dose group, 63.6% of those in the high-dose group, and 50% of controls. GI disorders occurred in 41.6%, 52.3%, and 36.4% of patients in the groups, respectively.

Serious adverse events were more common in the voclosporin groups, occurring in 25.8% and 25% of patients in the low- and high-dose groups, respectively, compared with 15.8% of patients in the control group.

Ten of the 13 deaths occurred in the low-dose voclosporin group (3 due to infection, 3 due to thromboembolism, and 4 due to “other” causes); 2 occurred in the high-dose voclosporin group (1 each due to infection and thromboembolism); and 1 death due to thromboembolism occurred in the control group. As most of the deaths were clustered in the low-dose arm, and 11 of the 13 deaths occurred in areas with “compromised access to standard of care,” the deaths were not considered to be directly related to voclosporin therapy.

Patients who died had “a statistically different clinical baseline picture with higher levels of proteinuria or difficulty with comorbid conditions and some signs of poor nutrition,” Dr. Dooley said.

The findings of the study will be used as the basis for planned subsequent studies of the use of voclosporin in lupus nephritis, she said.

Voclosporin is an analogue of cyclosporin A that may allow flat dosing and a potentially improved safety profile compared with other calcineurin inhibitors.

Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, the maker of voclosporin, announced in early November 2016 that the twice-daily 23.7 mg voclosporin dose will advance to a global 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study in the second quarter of 2017. Voclosporin has already received fast track designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Dooley reported a financial relationship with Aurinia, which sponsored the study.

WASHINGTON – The investigational calcineurin inhibitor voclosporin, given in addition to mycophenolate mofetil and low-dose steroids, was associated with rapid and complete remissions in lupus nephritis patients in the randomized, controlled AURA-LV study.

Aurinia Urinary Protein Reduction Active – Lupus With Voclosporin (AURA-LV) included 265 subjects in over 20 countries with active lupus nephritis. Trial participants received low-dose voclosporin (23.7 mg b.i.d.) or high-dose voclosporin (39.5 mg b.i.d.) in addition to mycophenolate mofetil (2 g/day) and low-dose steroids. Patients began on 20-25 mg of a steroid with a taper to 5 mg at week 8 and 2.5 mg at week 16-24.

Complete remission occurred at 24 weeks in 32.6% of 89 subjects who received 23.7 mg of voclosporin twice daily and standard of care therapy and in 19.3% of 88 control subjects who received placebo and standard of care therapy (odds ratio, 2.03), Mary Anne Dooley, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The complete remission rate was 27.3% in the 88 subjects who received the higher dose (39.5 mg b.i.d.) of voclosporin. The difference between the high-dose voclosporin group and the control group was not statistically significant.

The “very exciting findings” of this study – the first lupus nephritis study to meet its primary endpoint of complete remission – are important, because “partial remission is insufficient for our patients,” she said.

“Clinical trials over the past 10 years have really shown that we’re not reaching a large group of patients. ... more than 40% of patients are complete nonresponders at 6 months,” she said. While attainment of partial remission has improved, half of those who achieve partial remission have been shown to have a 50% increase in the risk of end-stage renal disease in 10 years.

Complete remission was defined as urine protein/creatinine ratio of no more than 0.5 mg/mg using first morning void with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of at least 60 mL/min without a decrease of 20% or more, sustained low-dose steroids (at or below 10 mg/day) and no use of rescue medications.

Partial remission was a composite of reduction in protein/creatinine ratio of at least 50%, no use of rescue medication, and stability of renal function. Both the low- and high-dose voclosporin groups had outcomes that were superior to standard-of-care therapy, with 69.7% partial remission with low-dose voclosporin, 65.9% partial remission with high-dose voclosporin, and 49.4% partial remission with placebo, said Dr. Dooley, a rheumatologist in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“Patients began responding literally within weeks [to voclosporin] ... and we saw significant responses by 7-8 weeks. This was during the time period when the steroids rapidly decreased,” she said, noting that the steroid dosing at baseline was a median of 25 mg vs. 2.5 mg at 16 weeks.

Study subjects met ACR criteria for lupus and had biopsy-proven lupus nephritis, including proliferative nephritis class III/IV or class V alone or in combination with proliferative disease. All were treated with 2 g/day of mycophenolate mofetil, and the steroid taper “was such that by 10 weeks, patients were down to 5 mg, and that by 24 weeks the median dose was 2.5 mg,” she said.

Adverse events, most commonly infection and gastrointestinal disorders, occurred in 90% of study subjects. Infections occurred in 56.2% of those in the low-dose group, 63.6% of those in the high-dose group, and 50% of controls. GI disorders occurred in 41.6%, 52.3%, and 36.4% of patients in the groups, respectively.

Serious adverse events were more common in the voclosporin groups, occurring in 25.8% and 25% of patients in the low- and high-dose groups, respectively, compared with 15.8% of patients in the control group.

Ten of the 13 deaths occurred in the low-dose voclosporin group (3 due to infection, 3 due to thromboembolism, and 4 due to “other” causes); 2 occurred in the high-dose voclosporin group (1 each due to infection and thromboembolism); and 1 death due to thromboembolism occurred in the control group. As most of the deaths were clustered in the low-dose arm, and 11 of the 13 deaths occurred in areas with “compromised access to standard of care,” the deaths were not considered to be directly related to voclosporin therapy.

Patients who died had “a statistically different clinical baseline picture with higher levels of proteinuria or difficulty with comorbid conditions and some signs of poor nutrition,” Dr. Dooley said.

The findings of the study will be used as the basis for planned subsequent studies of the use of voclosporin in lupus nephritis, she said.

Voclosporin is an analogue of cyclosporin A that may allow flat dosing and a potentially improved safety profile compared with other calcineurin inhibitors.

Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, the maker of voclosporin, announced in early November 2016 that the twice-daily 23.7 mg voclosporin dose will advance to a global 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study in the second quarter of 2017. Voclosporin has already received fast track designation from the Food and Drug Administration.

Dr. Dooley reported a financial relationship with Aurinia, which sponsored the study.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The complete remission rate at 24 weeks was 32.6% vs. 19.3% in patients receiving low-dose voclosporin vs. controls (odds ratio, 2.03).

Data source: The randomized, controlled AURA-LV study of 265 lupus nephritis patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Dooley reported a financial relationship with Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, which sponsored the study.

Adjustment for fluid balance improved detection of AKI in critically ill children

CHICAGO – Adjustment for fluid balance increased the detection rate of acute kidney injury, more accurately staged the kidney damage, and distinguished false-positive cases in critically ill children, based on a secondary analysis of the Study of the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury in Children Using Risk Stratification and Biomarkers (AKI-CHERUB).

Fluid overload can mask acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill children. “The failure to correct serum creatinine measure for fluid overload dilutes the impact of AKI on outcomes,” David T. Selewski, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said at the annual meeting sponsored by the American Society for Nephrology.

The primary outcome was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes were length of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay in the ICU and the hospital.

The original study documented an ICU mortality rate of 7.1%. AKI was identified in 77 (41.8%) of the 184 patients. The median peak fluid overload during ICU admission was 12.9 (interquartile range, 7.4-20.8).

The serum creatinine data were corrected for fluid balance and these rates were reassessed. Following the adjustment, the rate of AKI increased from 41.8% to 53.4%, with 30 new cases identified according to standard defined criteria. The mean fluid overload was now 11.2 (interquartile range, 5.7-17.7).

In the original cohort, there were 40 cases of severe AKI (stage 2 and 3). Following the creatinine correction, 13 more cases were judged to be severe. Of these, five cases were associated with a worse outcome in terms of ICU mortality. Additionally, 10 cases that had been diagnosed as AKI were found to be false positives.

The results need to be studied in larger studies and in other populations, such as neonates, Dr. Selewski said.

CHICAGO – Adjustment for fluid balance increased the detection rate of acute kidney injury, more accurately staged the kidney damage, and distinguished false-positive cases in critically ill children, based on a secondary analysis of the Study of the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury in Children Using Risk Stratification and Biomarkers (AKI-CHERUB).

Fluid overload can mask acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill children. “The failure to correct serum creatinine measure for fluid overload dilutes the impact of AKI on outcomes,” David T. Selewski, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said at the annual meeting sponsored by the American Society for Nephrology.

The primary outcome was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes were length of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay in the ICU and the hospital.

The original study documented an ICU mortality rate of 7.1%. AKI was identified in 77 (41.8%) of the 184 patients. The median peak fluid overload during ICU admission was 12.9 (interquartile range, 7.4-20.8).

The serum creatinine data were corrected for fluid balance and these rates were reassessed. Following the adjustment, the rate of AKI increased from 41.8% to 53.4%, with 30 new cases identified according to standard defined criteria. The mean fluid overload was now 11.2 (interquartile range, 5.7-17.7).

In the original cohort, there were 40 cases of severe AKI (stage 2 and 3). Following the creatinine correction, 13 more cases were judged to be severe. Of these, five cases were associated with a worse outcome in terms of ICU mortality. Additionally, 10 cases that had been diagnosed as AKI were found to be false positives.

The results need to be studied in larger studies and in other populations, such as neonates, Dr. Selewski said.

CHICAGO – Adjustment for fluid balance increased the detection rate of acute kidney injury, more accurately staged the kidney damage, and distinguished false-positive cases in critically ill children, based on a secondary analysis of the Study of the Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury in Children Using Risk Stratification and Biomarkers (AKI-CHERUB).

Fluid overload can mask acute kidney injury (AKI) in critically ill children. “The failure to correct serum creatinine measure for fluid overload dilutes the impact of AKI on outcomes,” David T. Selewski, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, said at the annual meeting sponsored by the American Society for Nephrology.

The primary outcome was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes were length of mechanical ventilation, and length of stay in the ICU and the hospital.

The original study documented an ICU mortality rate of 7.1%. AKI was identified in 77 (41.8%) of the 184 patients. The median peak fluid overload during ICU admission was 12.9 (interquartile range, 7.4-20.8).

The serum creatinine data were corrected for fluid balance and these rates were reassessed. Following the adjustment, the rate of AKI increased from 41.8% to 53.4%, with 30 new cases identified according to standard defined criteria. The mean fluid overload was now 11.2 (interquartile range, 5.7-17.7).

In the original cohort, there were 40 cases of severe AKI (stage 2 and 3). Following the creatinine correction, 13 more cases were judged to be severe. Of these, five cases were associated with a worse outcome in terms of ICU mortality. Additionally, 10 cases that had been diagnosed as AKI were found to be false positives.

The results need to be studied in larger studies and in other populations, such as neonates, Dr. Selewski said.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2016

Key clinical point: Acute kidney injury can be detected more accurately in critically ill children by correcting for fluid overload.

Major finding: Fluid overload masked diagnosis of over 40% of patients with acute kidney injury in an observational study.

Data source: Secondary analysis of AKI-CHERUB single-center observational study involving 181 critically ill children.

Disclosures: The AKI-CHERUB study was funded by NIH. Dr. Selewski reported having no financial disclosures.

Acute kidney injury common in children, young adults in ICU

Acute kidney injury is common in children and young adults admitted to ICUs, and cannot always be identified by plasma creatinine level alone, according to the authors of a study presented at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury, Renal Angina, and Epidemiology (AWARE) study was a prospective, international, observational study in 4,683 patients aged 3 months to 25 years, recruited from 32 pediatric ICUs over the course of 3 months.

Ahmad Kaddourah, MD, from the Center for Acute Care Nephrology at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his coauthors found that 27% of the participants developed acute kidney injury and 12% developed severe acute kidney injury – defined as stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury – within the first 7 days after admission.

The risk of death within 28 days was 77% higher among individuals with severe acute kidney injury, even after accounting for their original diagnosis when they were admitted to the ICU. Mortality among these individuals was 11%, compared with 2.5% among patients without severe acute kidney injury. These patients also had an increased use of renal replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation, and were more likely to have longer stays in hospital.

Researchers also saw a stepwise increase in 28-day mortality associated with maximum stage of acute kidney injury.

“The common and early occurrence of acute kidney injury reinforces the need for systematic surveillance for acute kidney injury at the time of admission to the ICU,” Dr. Kaddourah and his associates wrote. “Early identification of modifiable risk factors for acute kidney injury (e.g., nephrotoxic medications) or adverse sequelae (e.g., fluid overload) has the potential to decrease morbidity and mortality.”

Of particular note was the observation that 67% of the patients who met the urine-output criteria for acute kidney injury would not have been diagnosed using the plasma creatinine criteria alone. Furthermore, “mortality was higher among patients diagnosed with stage 3 acute kidney injury according to urine output than among those diagnosed according to plasma creatinine levels,” the authors reported.

There was a steady increase in the daily prevalence of acute kidney disease, from 15% on day 1 after admission to 20% by day 7. Patients with stage 1 acute kidney injury on day 1 also were more likely to progress to stage 2 or 3 by day 7, compared with patients who did not have acute kidney injury on admission.

However, around three-quarters of this increase in stage occurred within the first 4 days after admission, which the authors suggested would support a 4-day time frame for future studies on acute kidney injury in children. They also stressed that as their assessments for acute kidney injury stopped at day 7 after admission, there may have been incidents that were missed.

Dr. Kaddourah and his associates noted that although the rates of severe and acute kidney injury seen in the study were slightly lower than those observed in studies in adults, the associations with morbidity and mortality were similar.

“The presence of chronic systemic diseases contributes to residual confounding in studies of acute kidney injury in adults,” they wrote. “Children have a low prevalence of such chronic diseases; thus, although the incremental association between acute kidney injury and risk of death mirrors that seen in adults, our study suggests that acute kidney injury itself may be key to the associated morbidity and mortality.”

The study was supported by the Pediatric Nephrology Center for Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The authors declared grants, consultancies, speaking engagements, and other support from private industry, some related to and some outside of the submitted work.

A strength of this study is the definition of acute kidney injury, with the use of precise and validated criteria. Limitations of the study, beyond its observational nature, include the lack of data about diuretic and other treatment that may have influenced urine output, and the requirement for just a single baseline plasma creatinine level for study entry.

However, the study results indicate that acute injury is not only common among critically ill children and young adults, but is associated with adverse outcomes, implying that we should look more carefully for markers of acute kidney injury. Given the link between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease, it possible that identifying and treating acute kidney injury promptly might reduce the prevalence of chronic kidney disease, now estimated as roughly one in eight adults in the United States.

Julie R. Ingelfinger, MD, is a pediatric nephrologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and deputy editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (N Eng J Med. 2016 Nov 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe613456). No conflicts of interest were declared.

A strength of this study is the definition of acute kidney injury, with the use of precise and validated criteria. Limitations of the study, beyond its observational nature, include the lack of data about diuretic and other treatment that may have influenced urine output, and the requirement for just a single baseline plasma creatinine level for study entry.

However, the study results indicate that acute injury is not only common among critically ill children and young adults, but is associated with adverse outcomes, implying that we should look more carefully for markers of acute kidney injury. Given the link between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease, it possible that identifying and treating acute kidney injury promptly might reduce the prevalence of chronic kidney disease, now estimated as roughly one in eight adults in the United States.

Julie R. Ingelfinger, MD, is a pediatric nephrologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and deputy editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (N Eng J Med. 2016 Nov 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe613456). No conflicts of interest were declared.

A strength of this study is the definition of acute kidney injury, with the use of precise and validated criteria. Limitations of the study, beyond its observational nature, include the lack of data about diuretic and other treatment that may have influenced urine output, and the requirement for just a single baseline plasma creatinine level for study entry.

However, the study results indicate that acute injury is not only common among critically ill children and young adults, but is associated with adverse outcomes, implying that we should look more carefully for markers of acute kidney injury. Given the link between acute kidney injury and subsequent chronic kidney disease, it possible that identifying and treating acute kidney injury promptly might reduce the prevalence of chronic kidney disease, now estimated as roughly one in eight adults in the United States.

Julie R. Ingelfinger, MD, is a pediatric nephrologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and deputy editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (N Eng J Med. 2016 Nov 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe613456). No conflicts of interest were declared.

Acute kidney injury is common in children and young adults admitted to ICUs, and cannot always be identified by plasma creatinine level alone, according to the authors of a study presented at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury, Renal Angina, and Epidemiology (AWARE) study was a prospective, international, observational study in 4,683 patients aged 3 months to 25 years, recruited from 32 pediatric ICUs over the course of 3 months.

Ahmad Kaddourah, MD, from the Center for Acute Care Nephrology at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his coauthors found that 27% of the participants developed acute kidney injury and 12% developed severe acute kidney injury – defined as stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury – within the first 7 days after admission.

The risk of death within 28 days was 77% higher among individuals with severe acute kidney injury, even after accounting for their original diagnosis when they were admitted to the ICU. Mortality among these individuals was 11%, compared with 2.5% among patients without severe acute kidney injury. These patients also had an increased use of renal replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation, and were more likely to have longer stays in hospital.

Researchers also saw a stepwise increase in 28-day mortality associated with maximum stage of acute kidney injury.

“The common and early occurrence of acute kidney injury reinforces the need for systematic surveillance for acute kidney injury at the time of admission to the ICU,” Dr. Kaddourah and his associates wrote. “Early identification of modifiable risk factors for acute kidney injury (e.g., nephrotoxic medications) or adverse sequelae (e.g., fluid overload) has the potential to decrease morbidity and mortality.”

Of particular note was the observation that 67% of the patients who met the urine-output criteria for acute kidney injury would not have been diagnosed using the plasma creatinine criteria alone. Furthermore, “mortality was higher among patients diagnosed with stage 3 acute kidney injury according to urine output than among those diagnosed according to plasma creatinine levels,” the authors reported.

There was a steady increase in the daily prevalence of acute kidney disease, from 15% on day 1 after admission to 20% by day 7. Patients with stage 1 acute kidney injury on day 1 also were more likely to progress to stage 2 or 3 by day 7, compared with patients who did not have acute kidney injury on admission.

However, around three-quarters of this increase in stage occurred within the first 4 days after admission, which the authors suggested would support a 4-day time frame for future studies on acute kidney injury in children. They also stressed that as their assessments for acute kidney injury stopped at day 7 after admission, there may have been incidents that were missed.

Dr. Kaddourah and his associates noted that although the rates of severe and acute kidney injury seen in the study were slightly lower than those observed in studies in adults, the associations with morbidity and mortality were similar.

“The presence of chronic systemic diseases contributes to residual confounding in studies of acute kidney injury in adults,” they wrote. “Children have a low prevalence of such chronic diseases; thus, although the incremental association between acute kidney injury and risk of death mirrors that seen in adults, our study suggests that acute kidney injury itself may be key to the associated morbidity and mortality.”

The study was supported by the Pediatric Nephrology Center for Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The authors declared grants, consultancies, speaking engagements, and other support from private industry, some related to and some outside of the submitted work.

Acute kidney injury is common in children and young adults admitted to ICUs, and cannot always be identified by plasma creatinine level alone, according to the authors of a study presented at the meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The Assessment of Worldwide Acute Kidney Injury, Renal Angina, and Epidemiology (AWARE) study was a prospective, international, observational study in 4,683 patients aged 3 months to 25 years, recruited from 32 pediatric ICUs over the course of 3 months.

Ahmad Kaddourah, MD, from the Center for Acute Care Nephrology at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his coauthors found that 27% of the participants developed acute kidney injury and 12% developed severe acute kidney injury – defined as stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury – within the first 7 days after admission.

The risk of death within 28 days was 77% higher among individuals with severe acute kidney injury, even after accounting for their original diagnosis when they were admitted to the ICU. Mortality among these individuals was 11%, compared with 2.5% among patients without severe acute kidney injury. These patients also had an increased use of renal replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation, and were more likely to have longer stays in hospital.

Researchers also saw a stepwise increase in 28-day mortality associated with maximum stage of acute kidney injury.

“The common and early occurrence of acute kidney injury reinforces the need for systematic surveillance for acute kidney injury at the time of admission to the ICU,” Dr. Kaddourah and his associates wrote. “Early identification of modifiable risk factors for acute kidney injury (e.g., nephrotoxic medications) or adverse sequelae (e.g., fluid overload) has the potential to decrease morbidity and mortality.”

Of particular note was the observation that 67% of the patients who met the urine-output criteria for acute kidney injury would not have been diagnosed using the plasma creatinine criteria alone. Furthermore, “mortality was higher among patients diagnosed with stage 3 acute kidney injury according to urine output than among those diagnosed according to plasma creatinine levels,” the authors reported.

There was a steady increase in the daily prevalence of acute kidney disease, from 15% on day 1 after admission to 20% by day 7. Patients with stage 1 acute kidney injury on day 1 also were more likely to progress to stage 2 or 3 by day 7, compared with patients who did not have acute kidney injury on admission.

However, around three-quarters of this increase in stage occurred within the first 4 days after admission, which the authors suggested would support a 4-day time frame for future studies on acute kidney injury in children. They also stressed that as their assessments for acute kidney injury stopped at day 7 after admission, there may have been incidents that were missed.

Dr. Kaddourah and his associates noted that although the rates of severe and acute kidney injury seen in the study were slightly lower than those observed in studies in adults, the associations with morbidity and mortality were similar.

“The presence of chronic systemic diseases contributes to residual confounding in studies of acute kidney injury in adults,” they wrote. “Children have a low prevalence of such chronic diseases; thus, although the incremental association between acute kidney injury and risk of death mirrors that seen in adults, our study suggests that acute kidney injury itself may be key to the associated morbidity and mortality.”

The study was supported by the Pediatric Nephrology Center for Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The authors declared grants, consultancies, speaking engagements, and other support from private industry, some related to and some outside of the submitted work.

FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2016

Key clinical point: Acute kidney injury is common in children and young adults admitted to ICU, but many cases may be missed using plasma creatinine criteria alone.

Major finding: Among children and young adults admitted to intensive care, as many as 1 in 4 may have acute kidney injury and 1 in 10 may have severe acute kidney injury.

Data source: Prospective observational study in 4,683 patients aged 3 months to 25 years admitted to pediatric intensive care.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Pediatric Nephrology Center for Excellence at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The authors declared grants, consultancies, speaking engagements and other support from private industry, some related to and some outside of the submitted work.

Kidney Disease & “Bad Teeth”

Q)Someone at a conference I attended said kidney disease and bad teeth go hand in hand. Is this true? What does that mean for my patients?

“Bad teeth” can refer to periodontitis, a chronic inflammation of the tissue and structures around the teeth. The sixth most common disease in the world, periodontitis often leads to shrinkage of the gums, infection, and subsequent loosening or loss of teeth.3

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are predisposed to oral lesions and tooth decay related to dryness of the mouth; alterations in taste; malnutrition; and low albumin. Certain medications—such as ß-blockers, diuretics, anticholinergics, anticonvulsants, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors—can increase the risk for dry mouth and negatively affect oral structures.4

Compared with community-dwelling adults, those with CKD have higher rates of periodontitis, which increase with disease progression.5 A systematic review found that periodontitis increases the risk for CKD; evidence was inconclusive for the impact of periodontal treatment on estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) but suggested positive improvements in eGFR.6

There is growing evidence of a multifaceted relationship between CKD, diabetes, periodontitis, and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the leading cause of mortality in patients with CKD.7 Studies have shown that periodontitis can contribute to systemic inflammation, inhibiting glycemic control and elevating the risk for conditions such as CVD.8-10

Diabetes, the most common cause of CKD, is associated with adverse dental outcomes and poor glycemic control. Vice versa, severe periodontitis increases risk for diabetes and worsening glucose control. Mechanical periodontal treatment has been shown to improve glycemic control.8

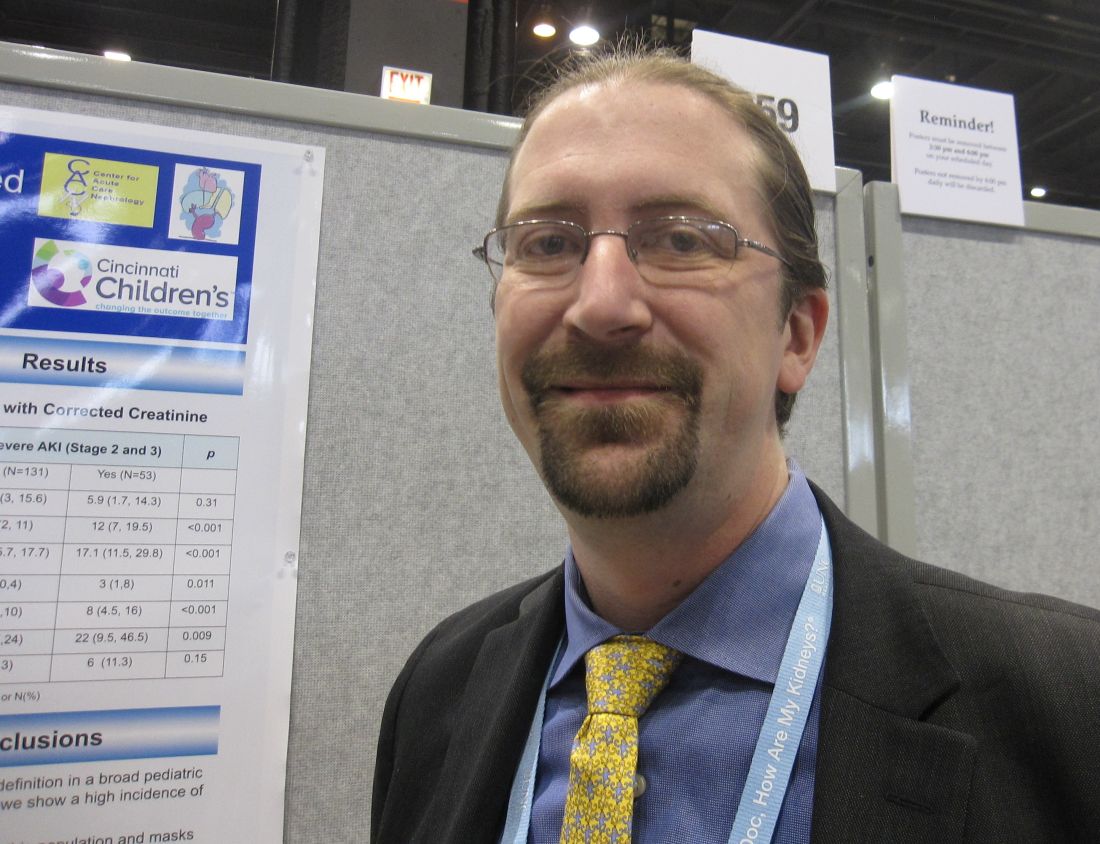

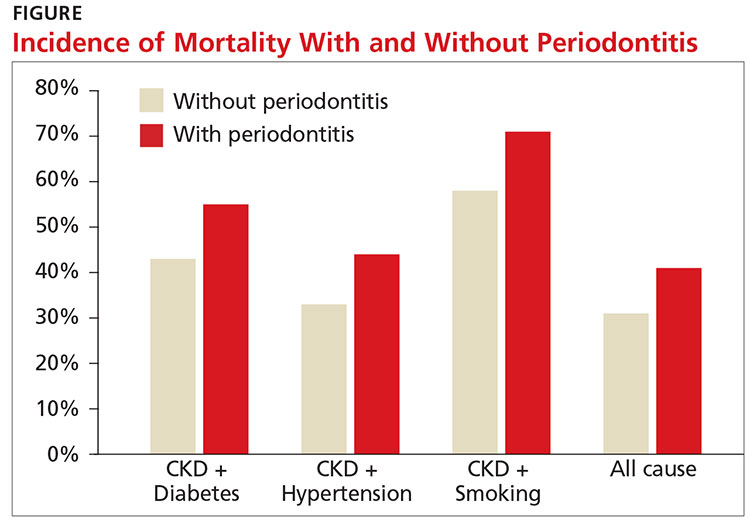

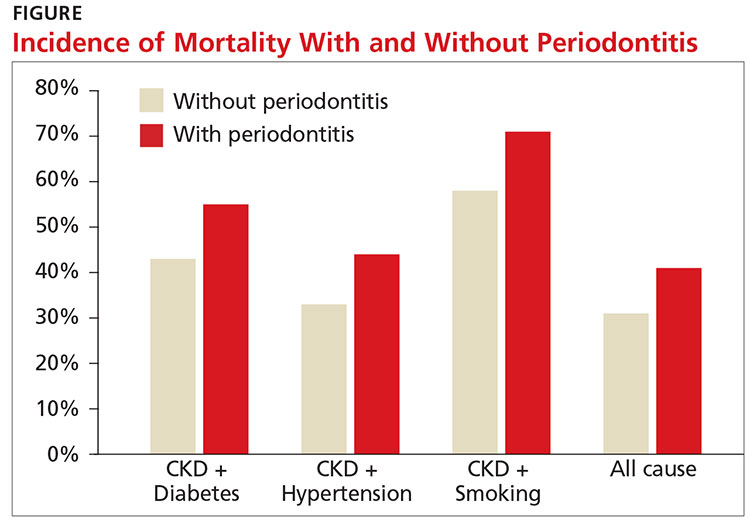

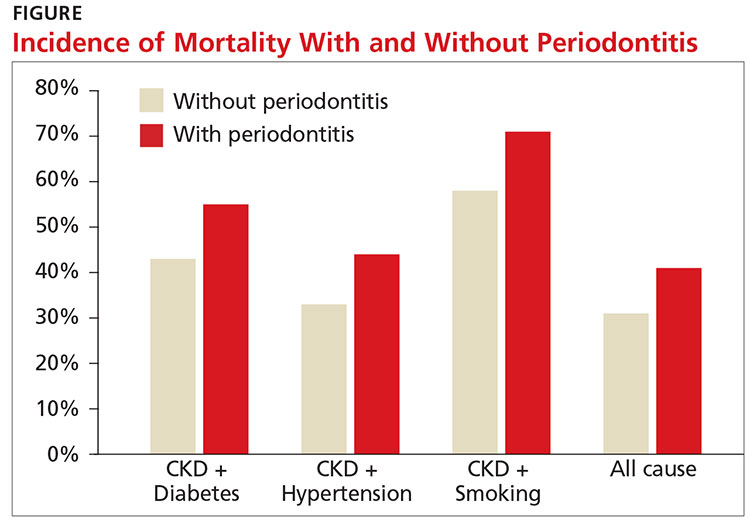

A recent study showed an increased risk for both CVD events and all-cause mortality in those with stage III to stage V CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). The study also found that periodontitis increased 10-year all-cause mortality in this population (see Figure).11

Research is ongoing regarding the complex relationship between CKD and oral health. For patients with CKD at any stage, evidence promotes the benefits of good oral health habits. Encourage smoking cessation, daily flossing and tooth brushing, regular dental cleanings, and prompt evaluation and treatment of any oral issues.12 —CS

Cynthia Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

3. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7):1387-1399.

4. Akar H, Akar GC, Carrero JJ, et al. Systemic consequences of poor oral health in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):218-226.

5. Borawski J, Wilczyn´ska-Borawska M, Stokowska W, Mys´liwiec M. The periodontal status of pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease and maintenance dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(2):457-464.

6. Chambrone L, Foz AM, Guglielmetti MR, et al. Periodontitis and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of the association of diseases and the effect of periodontal treatment on estimated glomerular filtration rate. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(5):443-456.

7. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296-1305.

8. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045-1053.

9. Chapple IL, Genco R; Working Group 2 of Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013; 40(14):S106-S112.

10. Menon V, Greene T, Wang X, et al. C-reactive protein and albumin as predictors of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(2):766-772.

11. Sharma P, Dietrich T, Ferro CJ, et al. Association between periodontitis and mortality in stages 3-5 chronic kidney disease: NHANES III and linked mortality study. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(2):104-113.

12. Ariyamuthu VK, Nolph KD, Ringdahl BE. Periodontal disease in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease patients: a review. Cardiorenal Med. 2013;3(1):71-78.

Q)Someone at a conference I attended said kidney disease and bad teeth go hand in hand. Is this true? What does that mean for my patients?

“Bad teeth” can refer to periodontitis, a chronic inflammation of the tissue and structures around the teeth. The sixth most common disease in the world, periodontitis often leads to shrinkage of the gums, infection, and subsequent loosening or loss of teeth.3

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are predisposed to oral lesions and tooth decay related to dryness of the mouth; alterations in taste; malnutrition; and low albumin. Certain medications—such as ß-blockers, diuretics, anticholinergics, anticonvulsants, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors—can increase the risk for dry mouth and negatively affect oral structures.4

Compared with community-dwelling adults, those with CKD have higher rates of periodontitis, which increase with disease progression.5 A systematic review found that periodontitis increases the risk for CKD; evidence was inconclusive for the impact of periodontal treatment on estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) but suggested positive improvements in eGFR.6

There is growing evidence of a multifaceted relationship between CKD, diabetes, periodontitis, and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the leading cause of mortality in patients with CKD.7 Studies have shown that periodontitis can contribute to systemic inflammation, inhibiting glycemic control and elevating the risk for conditions such as CVD.8-10

Diabetes, the most common cause of CKD, is associated with adverse dental outcomes and poor glycemic control. Vice versa, severe periodontitis increases risk for diabetes and worsening glucose control. Mechanical periodontal treatment has been shown to improve glycemic control.8

A recent study showed an increased risk for both CVD events and all-cause mortality in those with stage III to stage V CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). The study also found that periodontitis increased 10-year all-cause mortality in this population (see Figure).11

Research is ongoing regarding the complex relationship between CKD and oral health. For patients with CKD at any stage, evidence promotes the benefits of good oral health habits. Encourage smoking cessation, daily flossing and tooth brushing, regular dental cleanings, and prompt evaluation and treatment of any oral issues.12 —CS

Cynthia Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

Q)Someone at a conference I attended said kidney disease and bad teeth go hand in hand. Is this true? What does that mean for my patients?

“Bad teeth” can refer to periodontitis, a chronic inflammation of the tissue and structures around the teeth. The sixth most common disease in the world, periodontitis often leads to shrinkage of the gums, infection, and subsequent loosening or loss of teeth.3

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are predisposed to oral lesions and tooth decay related to dryness of the mouth; alterations in taste; malnutrition; and low albumin. Certain medications—such as ß-blockers, diuretics, anticholinergics, anticonvulsants, and serotonin reuptake inhibitors—can increase the risk for dry mouth and negatively affect oral structures.4

Compared with community-dwelling adults, those with CKD have higher rates of periodontitis, which increase with disease progression.5 A systematic review found that periodontitis increases the risk for CKD; evidence was inconclusive for the impact of periodontal treatment on estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) but suggested positive improvements in eGFR.6

There is growing evidence of a multifaceted relationship between CKD, diabetes, periodontitis, and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the leading cause of mortality in patients with CKD.7 Studies have shown that periodontitis can contribute to systemic inflammation, inhibiting glycemic control and elevating the risk for conditions such as CVD.8-10

Diabetes, the most common cause of CKD, is associated with adverse dental outcomes and poor glycemic control. Vice versa, severe periodontitis increases risk for diabetes and worsening glucose control. Mechanical periodontal treatment has been shown to improve glycemic control.8

A recent study showed an increased risk for both CVD events and all-cause mortality in those with stage III to stage V CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2). The study also found that periodontitis increased 10-year all-cause mortality in this population (see Figure).11

Research is ongoing regarding the complex relationship between CKD and oral health. For patients with CKD at any stage, evidence promotes the benefits of good oral health habits. Encourage smoking cessation, daily flossing and tooth brushing, regular dental cleanings, and prompt evaluation and treatment of any oral issues.12 —CS

Cynthia Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

3. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7):1387-1399.

4. Akar H, Akar GC, Carrero JJ, et al. Systemic consequences of poor oral health in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):218-226.

5. Borawski J, Wilczyn´ska-Borawska M, Stokowska W, Mys´liwiec M. The periodontal status of pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease and maintenance dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(2):457-464.

6. Chambrone L, Foz AM, Guglielmetti MR, et al. Periodontitis and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of the association of diseases and the effect of periodontal treatment on estimated glomerular filtration rate. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(5):443-456.

7. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296-1305.

8. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045-1053.

9. Chapple IL, Genco R; Working Group 2 of Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013; 40(14):S106-S112.

10. Menon V, Greene T, Wang X, et al. C-reactive protein and albumin as predictors of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(2):766-772.

11. Sharma P, Dietrich T, Ferro CJ, et al. Association between periodontitis and mortality in stages 3-5 chronic kidney disease: NHANES III and linked mortality study. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(2):104-113.

12. Ariyamuthu VK, Nolph KD, Ringdahl BE. Periodontal disease in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease patients: a review. Cardiorenal Med. 2013;3(1):71-78.

3. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7):1387-1399.

4. Akar H, Akar GC, Carrero JJ, et al. Systemic consequences of poor oral health in chronic kidney disease patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):218-226.

5. Borawski J, Wilczyn´ska-Borawska M, Stokowska W, Mys´liwiec M. The periodontal status of pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease and maintenance dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(2):457-464.

6. Chambrone L, Foz AM, Guglielmetti MR, et al. Periodontitis and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of the association of diseases and the effect of periodontal treatment on estimated glomerular filtration rate. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(5):443-456.

7. Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296-1305.

8. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93(11):1045-1053.

9. Chapple IL, Genco R; Working Group 2 of Joint EFP/AAP Workshop. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2013; 40(14):S106-S112.

10. Menon V, Greene T, Wang X, et al. C-reactive protein and albumin as predictors of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(2):766-772.

11. Sharma P, Dietrich T, Ferro CJ, et al. Association between periodontitis and mortality in stages 3-5 chronic kidney disease: NHANES III and linked mortality study. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(2):104-113.

12. Ariyamuthu VK, Nolph KD, Ringdahl BE. Periodontal disease in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease patients: a review. Cardiorenal Med. 2013;3(1):71-78.

Urate-lowering therapy poses no harm to kidney function

WASHINGTON – Evidence supporting the renal benefits of urate-lowering therapy in patients with hyperuricemia and gout comes from two separate studies presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In the first study, allopurinol did not increase the risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) in newly diagnosed patients with gout and normal or near-normal kidney function. The second study found that urate-lowering therapy (ULT) improved kidney function in patients who already had CKD.

Allopurinol in gout

The study was prompted by the recognition that gout patients are underdiagnosed and undertreated, and even when they have a diagnosis, both patients and primary care physicians who treat the majority of gout patients shy away from ULT.

“Further exacerbating the poor management of gout is the common practice of lowering the dose or stopping allopurinol when a patient with gout begins to have a decline in kidney function, which inevitably adds to the poor control of gout,” Dr. Vargas-Santos explained.

The study was based on electronic health records from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) database that includes patients treated by general practitioners in the United Kingdom. The study enrolled 13,608 patients with newly diagnosed gout and normal kidney function who initiated ULT with allopurinol; these patients were compared with 13,608 gout patients (matched by propensity score) in the THIN database who did not start ULT.

Patients were aged 18-89 years (mean age, 58 years) with incident gout diagnosed between 2000 and 2014 who had at least one contact with a general practitioner within a year of study enrollment. The investigators analyzed the relationship between allopurinol use by gout patients and the development of CKD stage 3 or higher.

At a mean follow-up of 4 years, there was no increased risk of developing CKD stage 3 or higher in the allopurinol users: 1,401 of the allopurinol initiators versus 1,319 of nonusers developed CKD stage 3 or higher. The relative risk of developing CKD stage 3 or higher on allopurinol was 1.05, which was not statistically significant. “Our study shows that there was no risk of harm to the kidney with allopurinol. This suggests that if a patient on gout presents with declining kidney function, it is better to look for other causes and keep the patient on allopurinol to lower serum urate. Accumulating evidence supports this. Doctors have to be less fearful of prescribing allopurinol. Gout patients deserve better,” Dr. Vargas-Santos said.

ULT in CKD

ULT improved kidney function in patients with CKD in a large retrospective study, with the greatest improvement observed in patients with CKD stage 3 and some improvement observed in patients with CKD stage 2. ULT had no benefit in patients with CKD stage 4, suggesting that these patients are too advanced to improve.

The study was conducted from 2008 to 2014 and included 12,751 patients with serum urate levels of greater than 7 mg/dL and CKD stages 2, 3, and 4 at the index date (the first time this test result was reported). Patients were drawn from the Kaiser Permanente database and treated by primary care physicians. Patients were followed for 1 year from the index date. The primary outcome measure was a 30% increase or a 30% decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) from baseline to the last available result.

Of the 12,751 patients, 2,690 were on ULT and 10,061 were not. Goal serum urate (sUA) was achieved in 1,118 (42%) of patients on ULT. Among patients who achieved goal sUA, a 30% improvement in GFR was observed in 17.1% versus 10.4% of patients who did not achieve goal sUA, for an absolute difference of 6.7% (P less than .001).

For patients at goal versus those not at goal, the ratio of improvement was 3.4 and 3.8, respectively.

“This study suggests that patients with CKD should be tested for uric acid independent of whether they have gout or not. Getting to goal is important. Stage 3 CKD is the sweet spot where patients got the most pronounced benefit from urate-lowering therapy,” he said. “Stage 4 CDK is too late.”

The authors of both studies had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

WASHINGTON – Evidence supporting the renal benefits of urate-lowering therapy in patients with hyperuricemia and gout comes from two separate studies presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

In the first study, allopurinol did not increase the risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) in newly diagnosed patients with gout and normal or near-normal kidney function. The second study found that urate-lowering therapy (ULT) improved kidney function in patients who already had CKD.

Allopurinol in gout

The study was prompted by the recognition that gout patients are underdiagnosed and undertreated, and even when they have a diagnosis, both patients and primary care physicians who treat the majority of gout patients shy away from ULT.

“Further exacerbating the poor management of gout is the common practice of lowering the dose or stopping allopurinol when a patient with gout begins to have a decline in kidney function, which inevitably adds to the poor control of gout,” Dr. Vargas-Santos explained.

The study was based on electronic health records from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) database that includes patients treated by general practitioners in the United Kingdom. The study enrolled 13,608 patients with newly diagnosed gout and normal kidney function who initiated ULT with allopurinol; these patients were compared with 13,608 gout patients (matched by propensity score) in the THIN database who did not start ULT.

Patients were aged 18-89 years (mean age, 58 years) with incident gout diagnosed between 2000 and 2014 who had at least one contact with a general practitioner within a year of study enrollment. The investigators analyzed the relationship between allopurinol use by gout patients and the development of CKD stage 3 or higher.

At a mean follow-up of 4 years, there was no increased risk of developing CKD stage 3 or higher in the allopurinol users: 1,401 of the allopurinol initiators versus 1,319 of nonusers developed CKD stage 3 or higher. The relative risk of developing CKD stage 3 or higher on allopurinol was 1.05, which was not statistically significant. “Our study shows that there was no risk of harm to the kidney with allopurinol. This suggests that if a patient on gout presents with declining kidney function, it is better to look for other causes and keep the patient on allopurinol to lower serum urate. Accumulating evidence supports this. Doctors have to be less fearful of prescribing allopurinol. Gout patients deserve better,” Dr. Vargas-Santos said.

ULT in CKD

ULT improved kidney function in patients with CKD in a large retrospective study, with the greatest improvement observed in patients with CKD stage 3 and some improvement observed in patients with CKD stage 2. ULT had no benefit in patients with CKD stage 4, suggesting that these patients are too advanced to improve.

The study was conducted from 2008 to 2014 and included 12,751 patients with serum urate levels of greater than 7 mg/dL and CKD stages 2, 3, and 4 at the index date (the first time this test result was reported). Patients were drawn from the Kaiser Permanente database and treated by primary care physicians. Patients were followed for 1 year from the index date. The primary outcome measure was a 30% increase or a 30% decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) from baseline to the last available result.

Of the 12,751 patients, 2,690 were on ULT and 10,061 were not. Goal serum urate (sUA) was achieved in 1,118 (42%) of patients on ULT. Among patients who achieved goal sUA, a 30% improvement in GFR was observed in 17.1% versus 10.4% of patients who did not achieve goal sUA, for an absolute difference of 6.7% (P less than .001).

For patients at goal versus those not at goal, the ratio of improvement was 3.4 and 3.8, respectively.