User login

Proton pump inhibitors linked to chronic kidney disease

The use of proton pump inhibitors increased the risk of chronic kidney disease by 20%-50%, said the authors of two large population-based cohort analyses published online Jan. 11 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

These are the first such studies to link PPI use to chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the association held up after controlling for multiple potential confounders, said Dr. Benjamin Lazarus of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his associates. “Further research is required to investigate whether PPI use itself causes kidney damage and, if so, the underlying mechanisms of this association,” they wrote.

Proton pump inhibitors have been linked to other adverse health effects but remain among the most frequently prescribed medications in the United States. To further explore the risk of PPI use, the researchers analyzed data for 10,482 adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study who were followed for a median of 13.9 years, and a replication cohort of 248,751 patients from a large rural health care system who were followed for a median of 6.2 years.

Incident CKD was defined based on hospital discharge diagnosis codes, reports of end-stage renal disease from the United States Renal Data System Registry, or a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 that persisted at follow-up visits (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 11. doi: 0.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193).

In the ARIC study, there were 56 cases of CKD among 322 self-reported baseline PPI users, for an incidence of 14.2 cases per 1,000 person-years – significantly higher than the rate of 10.7 cases per 1,000 person-years among self-reported baseline nonusers. The 10-year estimated absolute risk of CKD among baseline users was 11.8% – 3.3% higher than the expected risk had they not used PPIs. Furthermore, PPI users were at significantly higher risk of CKD after demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables were accounted for (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.0), after modeling varying use of PPIs over time (adjusted HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.5), after directly comparing PPI users with H2 receptor antagonist users (adjusted HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.01-1.9), and after comparing baseline PPI users with propensity score–matched nonusers (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7).

In the replication cohort, there were 1,921 new cases of CKD among 16,900 patients with an outpatient PPI prescription (incidence of 20.1 cases per 1,000 person-years). The incidence of CKD among the other patients was lower: 18.3 cases per 1,000 person-years. The use of PPIs was significantly associated with incident CKD in all analyses, and the 10-year absolute risk of CKD among baseline PPI users was 15.6% – 1.7% higher than the expected risk had they not used PPIs.

These observational analyses cannot show causality, but a causal relationship between PPIs and CKD “could have a considerable public health impact, give the widespread extent of use,” the researchers emphasized. “More than 15 million Americans used prescription PPIs in 2013, costing more than $10 billion. Study findings suggest that up to 70% of these prescriptions are without indication and that 25% of long-term PPI users could discontinue therapy without developing symptoms. Indeed, there are already calls for the reduction of unnecessary use of PPIs (BMJ. 2008;336:2-3).”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, both of which are part of the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no disclosures.

Available evidence suggests that proton pump inhibitor use is associated with an increased risk of both acute and chronic kidney disease, hypomagnesemia, Clostridium difficile infection, and osteoporotic fractures. Caution in prescribing PPIs should be used in patients at high risk for any of these conditions. Given the association with kidney disease and low magnesium levels, serum creatinine and magnesium levels probably should be monitored in patients using PPIs, especially those using high doses.

Given the evidence that PPI use is linked with a number of adverse outcomes, we recommend that patients and clinicians discuss the potential benefits and risks of PPI treatment, as well as potential alternative regimens such as histamine H2 receptor antagonists or lifestyle changes, before PPIs are prescribed. In patients with symptomatic gastrointestinal reflux, ulcer disease, and severe dyspepsia, the benefits of PPI use likely outweigh its potential harms. For less serious symptoms, however, and for prevention of bleeding in low-risk patients, potential harms may outweigh the benefits. A large number of patients are taking PPIs for no clear reason – often remote symptoms of dyspepsia or heartburn that have since resolved. In these patients, PPIs should be stopped to determine if symptomatic treatment is needed.

Dr. Adam J. Schoenfeld and Dr. Deborah Grady are with the University of California, San Francisco. They had no disclosures. These comments were taken from their editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7927).

The bottom line is that PPIs should be used continually for the three specific conditions for which they are known to be beneficial – hypersecretory states, gastroesophageal reflux disease (in all its manifestations), and NSAID/aspirin prophylaxis. As with all drugs, treatment always should be at the lowest effective dose. Although it is quite appropriate to limit chronic PPI use to these groups, given the potential association (no causality identified) with various putative side effects including renal disease, in my opinion, the risks of denying PPIs when indicated are higher than the low risks of renal or other possible side effects.

Dr. David C. Metz is associate chief for clinical affairs, GI division; codirector, esophagology and swallowing program; director, acid-peptic program; codirector, neuroendocrine tumor center; and professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Available evidence suggests that proton pump inhibitor use is associated with an increased risk of both acute and chronic kidney disease, hypomagnesemia, Clostridium difficile infection, and osteoporotic fractures. Caution in prescribing PPIs should be used in patients at high risk for any of these conditions. Given the association with kidney disease and low magnesium levels, serum creatinine and magnesium levels probably should be monitored in patients using PPIs, especially those using high doses.

Given the evidence that PPI use is linked with a number of adverse outcomes, we recommend that patients and clinicians discuss the potential benefits and risks of PPI treatment, as well as potential alternative regimens such as histamine H2 receptor antagonists or lifestyle changes, before PPIs are prescribed. In patients with symptomatic gastrointestinal reflux, ulcer disease, and severe dyspepsia, the benefits of PPI use likely outweigh its potential harms. For less serious symptoms, however, and for prevention of bleeding in low-risk patients, potential harms may outweigh the benefits. A large number of patients are taking PPIs for no clear reason – often remote symptoms of dyspepsia or heartburn that have since resolved. In these patients, PPIs should be stopped to determine if symptomatic treatment is needed.

Dr. Adam J. Schoenfeld and Dr. Deborah Grady are with the University of California, San Francisco. They had no disclosures. These comments were taken from their editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7927).

The bottom line is that PPIs should be used continually for the three specific conditions for which they are known to be beneficial – hypersecretory states, gastroesophageal reflux disease (in all its manifestations), and NSAID/aspirin prophylaxis. As with all drugs, treatment always should be at the lowest effective dose. Although it is quite appropriate to limit chronic PPI use to these groups, given the potential association (no causality identified) with various putative side effects including renal disease, in my opinion, the risks of denying PPIs when indicated are higher than the low risks of renal or other possible side effects.

Dr. David C. Metz is associate chief for clinical affairs, GI division; codirector, esophagology and swallowing program; director, acid-peptic program; codirector, neuroendocrine tumor center; and professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Available evidence suggests that proton pump inhibitor use is associated with an increased risk of both acute and chronic kidney disease, hypomagnesemia, Clostridium difficile infection, and osteoporotic fractures. Caution in prescribing PPIs should be used in patients at high risk for any of these conditions. Given the association with kidney disease and low magnesium levels, serum creatinine and magnesium levels probably should be monitored in patients using PPIs, especially those using high doses.

Given the evidence that PPI use is linked with a number of adverse outcomes, we recommend that patients and clinicians discuss the potential benefits and risks of PPI treatment, as well as potential alternative regimens such as histamine H2 receptor antagonists or lifestyle changes, before PPIs are prescribed. In patients with symptomatic gastrointestinal reflux, ulcer disease, and severe dyspepsia, the benefits of PPI use likely outweigh its potential harms. For less serious symptoms, however, and for prevention of bleeding in low-risk patients, potential harms may outweigh the benefits. A large number of patients are taking PPIs for no clear reason – often remote symptoms of dyspepsia or heartburn that have since resolved. In these patients, PPIs should be stopped to determine if symptomatic treatment is needed.

Dr. Adam J. Schoenfeld and Dr. Deborah Grady are with the University of California, San Francisco. They had no disclosures. These comments were taken from their editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7927).

The bottom line is that PPIs should be used continually for the three specific conditions for which they are known to be beneficial – hypersecretory states, gastroesophageal reflux disease (in all its manifestations), and NSAID/aspirin prophylaxis. As with all drugs, treatment always should be at the lowest effective dose. Although it is quite appropriate to limit chronic PPI use to these groups, given the potential association (no causality identified) with various putative side effects including renal disease, in my opinion, the risks of denying PPIs when indicated are higher than the low risks of renal or other possible side effects.

Dr. David C. Metz is associate chief for clinical affairs, GI division; codirector, esophagology and swallowing program; director, acid-peptic program; codirector, neuroendocrine tumor center; and professor of medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The use of proton pump inhibitors increased the risk of chronic kidney disease by 20%-50%, said the authors of two large population-based cohort analyses published online Jan. 11 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

These are the first such studies to link PPI use to chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the association held up after controlling for multiple potential confounders, said Dr. Benjamin Lazarus of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his associates. “Further research is required to investigate whether PPI use itself causes kidney damage and, if so, the underlying mechanisms of this association,” they wrote.

Proton pump inhibitors have been linked to other adverse health effects but remain among the most frequently prescribed medications in the United States. To further explore the risk of PPI use, the researchers analyzed data for 10,482 adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study who were followed for a median of 13.9 years, and a replication cohort of 248,751 patients from a large rural health care system who were followed for a median of 6.2 years.

Incident CKD was defined based on hospital discharge diagnosis codes, reports of end-stage renal disease from the United States Renal Data System Registry, or a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 that persisted at follow-up visits (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 11. doi: 0.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193).

In the ARIC study, there were 56 cases of CKD among 322 self-reported baseline PPI users, for an incidence of 14.2 cases per 1,000 person-years – significantly higher than the rate of 10.7 cases per 1,000 person-years among self-reported baseline nonusers. The 10-year estimated absolute risk of CKD among baseline users was 11.8% – 3.3% higher than the expected risk had they not used PPIs. Furthermore, PPI users were at significantly higher risk of CKD after demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables were accounted for (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.0), after modeling varying use of PPIs over time (adjusted HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.5), after directly comparing PPI users with H2 receptor antagonist users (adjusted HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.01-1.9), and after comparing baseline PPI users with propensity score–matched nonusers (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7).

In the replication cohort, there were 1,921 new cases of CKD among 16,900 patients with an outpatient PPI prescription (incidence of 20.1 cases per 1,000 person-years). The incidence of CKD among the other patients was lower: 18.3 cases per 1,000 person-years. The use of PPIs was significantly associated with incident CKD in all analyses, and the 10-year absolute risk of CKD among baseline PPI users was 15.6% – 1.7% higher than the expected risk had they not used PPIs.

These observational analyses cannot show causality, but a causal relationship between PPIs and CKD “could have a considerable public health impact, give the widespread extent of use,” the researchers emphasized. “More than 15 million Americans used prescription PPIs in 2013, costing more than $10 billion. Study findings suggest that up to 70% of these prescriptions are without indication and that 25% of long-term PPI users could discontinue therapy without developing symptoms. Indeed, there are already calls for the reduction of unnecessary use of PPIs (BMJ. 2008;336:2-3).”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, both of which are part of the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no disclosures.

The use of proton pump inhibitors increased the risk of chronic kidney disease by 20%-50%, said the authors of two large population-based cohort analyses published online Jan. 11 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

These are the first such studies to link PPI use to chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the association held up after controlling for multiple potential confounders, said Dr. Benjamin Lazarus of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his associates. “Further research is required to investigate whether PPI use itself causes kidney damage and, if so, the underlying mechanisms of this association,” they wrote.

Proton pump inhibitors have been linked to other adverse health effects but remain among the most frequently prescribed medications in the United States. To further explore the risk of PPI use, the researchers analyzed data for 10,482 adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study who were followed for a median of 13.9 years, and a replication cohort of 248,751 patients from a large rural health care system who were followed for a median of 6.2 years.

Incident CKD was defined based on hospital discharge diagnosis codes, reports of end-stage renal disease from the United States Renal Data System Registry, or a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 that persisted at follow-up visits (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 11. doi: 0.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7193).

In the ARIC study, there were 56 cases of CKD among 322 self-reported baseline PPI users, for an incidence of 14.2 cases per 1,000 person-years – significantly higher than the rate of 10.7 cases per 1,000 person-years among self-reported baseline nonusers. The 10-year estimated absolute risk of CKD among baseline users was 11.8% – 3.3% higher than the expected risk had they not used PPIs. Furthermore, PPI users were at significantly higher risk of CKD after demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical variables were accounted for (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.0), after modeling varying use of PPIs over time (adjusted HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2-1.5), after directly comparing PPI users with H2 receptor antagonist users (adjusted HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.01-1.9), and after comparing baseline PPI users with propensity score–matched nonusers (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7).

In the replication cohort, there were 1,921 new cases of CKD among 16,900 patients with an outpatient PPI prescription (incidence of 20.1 cases per 1,000 person-years). The incidence of CKD among the other patients was lower: 18.3 cases per 1,000 person-years. The use of PPIs was significantly associated with incident CKD in all analyses, and the 10-year absolute risk of CKD among baseline PPI users was 15.6% – 1.7% higher than the expected risk had they not used PPIs.

These observational analyses cannot show causality, but a causal relationship between PPIs and CKD “could have a considerable public health impact, give the widespread extent of use,” the researchers emphasized. “More than 15 million Americans used prescription PPIs in 2013, costing more than $10 billion. Study findings suggest that up to 70% of these prescriptions are without indication and that 25% of long-term PPI users could discontinue therapy without developing symptoms. Indeed, there are already calls for the reduction of unnecessary use of PPIs (BMJ. 2008;336:2-3).”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, both of which are part of the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The use of proton pump inhibitors was significantly associated with incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in two large population-based studies.

Major finding: Baseline PPI use was associated with a 20%-50% increase in the risk of CKD, and the association held up in all sensitivity analyses.

Data source: A prospective, population-based cohort study of 10,482 adults from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study and a separate replication analysis of 248,751 patients from a large health care system.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, both of which are part of the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no disclosures.

Denosumab boosts BMD in kidney transplant recipients

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Twice-yearly denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients, but was associated with more frequent episodes of urinary tract infections and hypocalcemia, results from a randomized trial showed.

“Kidney transplant recipients lose bone mass and are at increased risk for fractures, more so in females than in males,” Dr. Rudolf P. Wuthrich said at Kidney Week 2015, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology. Results from previous studies suggest that one in five patients may develop a fracture within 5 years after kidney transplantation.

Considering that current therapeutic options to prevent bone loss are limited, Dr. Wuthrich, director of the Clinic for Nephrology at University Hospital Zurich, and his associates assessed the efficacy and safety of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibition with denosumab to improve bone mineralization in the first year after kidney transplantation. They recruited 108 patients from June 2011 to May 2014. Of these, 90 were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment. The study’s primary endpoint was the percentage change in bone mineral density measured by DXA at the lumbar spine at 12 months. The study, known as Denosumab for Prevention of Osteoporosis in Renal Transplant Recipients (POSTOP), was limited to adults who had undergone kidney transplantation within 28 days and who were on standard triple immunosuppression, including a calcineurin antagonist, mycophenolate, and steroids.

Dr. Wuthrich reported results from 46 patients in the denosumab group and 44 patients in the control group. At baseline, their mean age was 50 years, 63% were male, and 96% were white. After 12 months, the total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001). Denosumab also significantly increased BMD at the total hip by 1.9% (P = .035) over that in the control group at 12 months.

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography in a subgroup of 24 patients showed that denosumab also significantly increased BMD and cortical thickness at the distal tibia and radius (P less than .05). Two biomarkers of bone resorption in beta C-terminal telopeptide and urine deoxypyridinoline markedly decreased in the denosumab group, as did two biomarkers of bone formation in procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (P less than .0001).

In terms of adverse events, there were significantly more urinary tract infections in the denosumab group, compared with the control group (15% vs. 9%, respectively), as well as more episodes of diarrhea (9% vs. 5%), and transient hypocalcemia (3% vs. 0.3%). The number of serious adverse events was similar between groups, at 17% and 19%, respectively.

“We had significantly increased bone mineral density at all measured skeletal sites in response to denosumab,” Dr. Wuthrich concluded. “We had a significant increase in bone biomarkers and we can say that denosumab was generally safe in a complex population of immunosuppressed kidney transplant recipients. But it was associated with a higher incidence of urinary tract infections. At this point we have no good explanation as to why this is. We also had a few episodes of transient and asymptomatic hypocalcemia.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Denosumab effectively increased bone mineral density in kidney transplant recipients in the POSTOP trial.

Major finding: After 12 months, total lumbar spine BMD increased by 4.6% in the denosumab group and decreased by 0.5% in the control group, for a between-group difference of 5.1% (P less than .0001).

Data source: POSTOP, a study of 90 patients who were randomized within 4 weeks after kidney transplant surgery in a 1:1 ratio to receive subcutaneous injections of 60 mg denosumab at baseline and after 6 months, or no treatment.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

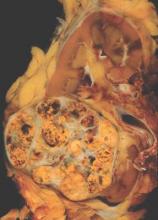

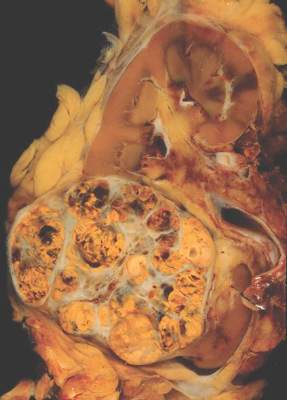

METEOR: Cabozantinib bests everolimus across renal cancer subgroups

The oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib is more efficacious than everolimus as therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma across a wide range of patients, suggests a subgroup analysis of the phase III METEOR trial being reported at the genitourinary cancers symposium.

Trial participants were 658 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma and clear cell histology who had experienced progression on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). There was no limit on the number of prior therapies.

The patients were randomized evenly to cabozantinib (Cometriq), which inhibits the VEGFR, MET, and AXL tyrosine kinases – all of which are up-regulated in this cancer – or to everolimus (Afinitor), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin that is considered a standard of care. (At present, cabozantinib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer.)

Results for the entire trial population showed that patients in the cabozantinib group were about half as likely as were their counterparts in the everolimus group to experience progression-free survival events, lead author Dr. Bernard Escudier reported in a press briefing held before the 2016 genitourinary cancers symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All patients appeared to derive benefit, with the reduction in risk ranging from 16% to 78% depending on the specific subgroup.

“Cabozantinib improved progression-free survival, compared to one of our standard therapies, everolimus, in advanced renal cell carcinoma,” concluded Dr. Escudier, who is chair of the Genitourinary Oncology Committee at the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. “Benefit was observed across prespecified subgroups,” including a small subgroup who had previously received immunotherapies targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1) signaling pathway.

Toxicity was somewhat problematic with cabozantinib, despite starting the drug at a lower dose than has typically been used in the past, he acknowledged. The most common side effects were diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, and hand-foot syndrome, and they often necessitated further dose reductions.

“Benefit with cabozantinib treatment is supported by a trend in overall survival, and hopefully, we will give this final overall survival analysis at ASCO this year,” Dr. Escudier added. Findings of an interim analysis reported last year were very promising with respect to this outcome (hazard ratio, 0.67; P = .005) (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 5;373:1814-23).

“This study is unique compared to others in that it allowed a broad range of patients: Patients could have had spread of cancer to the brain, they could have received any number of prior therapies, and they could have been exposed to immune-based treatments,” commented ASCO spokesperson and moderator of the press briefing Dr. Sumanta K. Pal. “The magnitude of benefit that patients got from cabozantinib far exceeds, in my opinion, what we have seen to date in this setting in terms of both delay in tumor growth and improving survival.”

In fact, for some oncologists, the findings may be strong enough to prompt use of cabozantinib as second-line therapy, according to Dr. Pal, who is a medical oncologist at the City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

“Given the fact that cabozantinib has a very compelling benefit in terms of both delay in tumor growth and a hint toward a benefit in terms of overall survival, I would perhaps tend to favor that as a second-line option as compared to other comparators, such as nivolumab (Opdivo), in that setting,” he said, referring to an antibody that targets the cell surface receptor PD-1. “Now that’s a personal opinion. I certainly think there are some merits with nivolumab, such as the toxicity profile. But, in broad terms, patients are very focused on clinical efficacy, and with that in mind, the data for cabozantinib truly speaks for itself.”

But Dr. Escudier offered a more-reserved perspective. “I think what people are going to do will be to use nivolumab as second-line [therapy] in most patients and keep cabozantinib for nivolumab failure,” he predicted. “Based on that, this subgroup, although small, is of importance. I don’t think it’s good enough to say we should use cabozantinib or nivolumab in second line based on the subgroup analyses we have.”

The eagerly awaited overall survival results will also help determine cabozantinib’s position in treatment sequence, he added. “If we get a survival advantage [that] is the same magnitude that we have with nivolumab, with such an impressive improvement in progression-free survival, maybe despite the toxicity with cabozantinib, people will be willing to use cabozantinib early on.”

In the new analysis, median progression-free survival in the entire trial population was 7.4 months with cabozantinib and 3.9 months with everolimus, translating to a near halving of the risk of events (hazard ratio, 0.52; P less than .001).

Subgroup analyses showed that patients in the cabozantinib group consistently had a lower risk of events, with hazard ratios ranging from 0.22 to 0.84, regardless of their Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center risk group, number of organs with metastases, presence of both visceral and bone metastases, number of prior VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the specific VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients who had received only one, and prior immunotherapy targeting the programmed death pathway.

The 42 patients who had previously received immunotherapy targeting that pathway were among those seeming to derive most benefit, Dr. Escudier reported. “Of course, this is a small number, but certainly an observation [of interest] when many patients are going to receive nivolumab as second-line in kidney cancer. This drug is still very active after PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies.”

The oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib is more efficacious than everolimus as therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma across a wide range of patients, suggests a subgroup analysis of the phase III METEOR trial being reported at the genitourinary cancers symposium.

Trial participants were 658 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma and clear cell histology who had experienced progression on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). There was no limit on the number of prior therapies.

The patients were randomized evenly to cabozantinib (Cometriq), which inhibits the VEGFR, MET, and AXL tyrosine kinases – all of which are up-regulated in this cancer – or to everolimus (Afinitor), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin that is considered a standard of care. (At present, cabozantinib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer.)

Results for the entire trial population showed that patients in the cabozantinib group were about half as likely as were their counterparts in the everolimus group to experience progression-free survival events, lead author Dr. Bernard Escudier reported in a press briefing held before the 2016 genitourinary cancers symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All patients appeared to derive benefit, with the reduction in risk ranging from 16% to 78% depending on the specific subgroup.

“Cabozantinib improved progression-free survival, compared to one of our standard therapies, everolimus, in advanced renal cell carcinoma,” concluded Dr. Escudier, who is chair of the Genitourinary Oncology Committee at the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. “Benefit was observed across prespecified subgroups,” including a small subgroup who had previously received immunotherapies targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1) signaling pathway.

Toxicity was somewhat problematic with cabozantinib, despite starting the drug at a lower dose than has typically been used in the past, he acknowledged. The most common side effects were diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, and hand-foot syndrome, and they often necessitated further dose reductions.

“Benefit with cabozantinib treatment is supported by a trend in overall survival, and hopefully, we will give this final overall survival analysis at ASCO this year,” Dr. Escudier added. Findings of an interim analysis reported last year were very promising with respect to this outcome (hazard ratio, 0.67; P = .005) (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 5;373:1814-23).

“This study is unique compared to others in that it allowed a broad range of patients: Patients could have had spread of cancer to the brain, they could have received any number of prior therapies, and they could have been exposed to immune-based treatments,” commented ASCO spokesperson and moderator of the press briefing Dr. Sumanta K. Pal. “The magnitude of benefit that patients got from cabozantinib far exceeds, in my opinion, what we have seen to date in this setting in terms of both delay in tumor growth and improving survival.”

In fact, for some oncologists, the findings may be strong enough to prompt use of cabozantinib as second-line therapy, according to Dr. Pal, who is a medical oncologist at the City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

“Given the fact that cabozantinib has a very compelling benefit in terms of both delay in tumor growth and a hint toward a benefit in terms of overall survival, I would perhaps tend to favor that as a second-line option as compared to other comparators, such as nivolumab (Opdivo), in that setting,” he said, referring to an antibody that targets the cell surface receptor PD-1. “Now that’s a personal opinion. I certainly think there are some merits with nivolumab, such as the toxicity profile. But, in broad terms, patients are very focused on clinical efficacy, and with that in mind, the data for cabozantinib truly speaks for itself.”

But Dr. Escudier offered a more-reserved perspective. “I think what people are going to do will be to use nivolumab as second-line [therapy] in most patients and keep cabozantinib for nivolumab failure,” he predicted. “Based on that, this subgroup, although small, is of importance. I don’t think it’s good enough to say we should use cabozantinib or nivolumab in second line based on the subgroup analyses we have.”

The eagerly awaited overall survival results will also help determine cabozantinib’s position in treatment sequence, he added. “If we get a survival advantage [that] is the same magnitude that we have with nivolumab, with such an impressive improvement in progression-free survival, maybe despite the toxicity with cabozantinib, people will be willing to use cabozantinib early on.”

In the new analysis, median progression-free survival in the entire trial population was 7.4 months with cabozantinib and 3.9 months with everolimus, translating to a near halving of the risk of events (hazard ratio, 0.52; P less than .001).

Subgroup analyses showed that patients in the cabozantinib group consistently had a lower risk of events, with hazard ratios ranging from 0.22 to 0.84, regardless of their Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center risk group, number of organs with metastases, presence of both visceral and bone metastases, number of prior VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the specific VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients who had received only one, and prior immunotherapy targeting the programmed death pathway.

The 42 patients who had previously received immunotherapy targeting that pathway were among those seeming to derive most benefit, Dr. Escudier reported. “Of course, this is a small number, but certainly an observation [of interest] when many patients are going to receive nivolumab as second-line in kidney cancer. This drug is still very active after PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies.”

The oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib is more efficacious than everolimus as therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma across a wide range of patients, suggests a subgroup analysis of the phase III METEOR trial being reported at the genitourinary cancers symposium.

Trial participants were 658 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma and clear cell histology who had experienced progression on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR). There was no limit on the number of prior therapies.

The patients were randomized evenly to cabozantinib (Cometriq), which inhibits the VEGFR, MET, and AXL tyrosine kinases – all of which are up-regulated in this cancer – or to everolimus (Afinitor), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin that is considered a standard of care. (At present, cabozantinib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer.)

Results for the entire trial population showed that patients in the cabozantinib group were about half as likely as were their counterparts in the everolimus group to experience progression-free survival events, lead author Dr. Bernard Escudier reported in a press briefing held before the 2016 genitourinary cancers symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. All patients appeared to derive benefit, with the reduction in risk ranging from 16% to 78% depending on the specific subgroup.

“Cabozantinib improved progression-free survival, compared to one of our standard therapies, everolimus, in advanced renal cell carcinoma,” concluded Dr. Escudier, who is chair of the Genitourinary Oncology Committee at the Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France. “Benefit was observed across prespecified subgroups,” including a small subgroup who had previously received immunotherapies targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1) signaling pathway.

Toxicity was somewhat problematic with cabozantinib, despite starting the drug at a lower dose than has typically been used in the past, he acknowledged. The most common side effects were diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, decreased appetite, and hand-foot syndrome, and they often necessitated further dose reductions.

“Benefit with cabozantinib treatment is supported by a trend in overall survival, and hopefully, we will give this final overall survival analysis at ASCO this year,” Dr. Escudier added. Findings of an interim analysis reported last year were very promising with respect to this outcome (hazard ratio, 0.67; P = .005) (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 5;373:1814-23).

“This study is unique compared to others in that it allowed a broad range of patients: Patients could have had spread of cancer to the brain, they could have received any number of prior therapies, and they could have been exposed to immune-based treatments,” commented ASCO spokesperson and moderator of the press briefing Dr. Sumanta K. Pal. “The magnitude of benefit that patients got from cabozantinib far exceeds, in my opinion, what we have seen to date in this setting in terms of both delay in tumor growth and improving survival.”

In fact, for some oncologists, the findings may be strong enough to prompt use of cabozantinib as second-line therapy, according to Dr. Pal, who is a medical oncologist at the City of Hope in Duarte, Calif.

“Given the fact that cabozantinib has a very compelling benefit in terms of both delay in tumor growth and a hint toward a benefit in terms of overall survival, I would perhaps tend to favor that as a second-line option as compared to other comparators, such as nivolumab (Opdivo), in that setting,” he said, referring to an antibody that targets the cell surface receptor PD-1. “Now that’s a personal opinion. I certainly think there are some merits with nivolumab, such as the toxicity profile. But, in broad terms, patients are very focused on clinical efficacy, and with that in mind, the data for cabozantinib truly speaks for itself.”

But Dr. Escudier offered a more-reserved perspective. “I think what people are going to do will be to use nivolumab as second-line [therapy] in most patients and keep cabozantinib for nivolumab failure,” he predicted. “Based on that, this subgroup, although small, is of importance. I don’t think it’s good enough to say we should use cabozantinib or nivolumab in second line based on the subgroup analyses we have.”

The eagerly awaited overall survival results will also help determine cabozantinib’s position in treatment sequence, he added. “If we get a survival advantage [that] is the same magnitude that we have with nivolumab, with such an impressive improvement in progression-free survival, maybe despite the toxicity with cabozantinib, people will be willing to use cabozantinib early on.”

In the new analysis, median progression-free survival in the entire trial population was 7.4 months with cabozantinib and 3.9 months with everolimus, translating to a near halving of the risk of events (hazard ratio, 0.52; P less than .001).

Subgroup analyses showed that patients in the cabozantinib group consistently had a lower risk of events, with hazard ratios ranging from 0.22 to 0.84, regardless of their Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center risk group, number of organs with metastases, presence of both visceral and bone metastases, number of prior VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the specific VEGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients who had received only one, and prior immunotherapy targeting the programmed death pathway.

The 42 patients who had previously received immunotherapy targeting that pathway were among those seeming to derive most benefit, Dr. Escudier reported. “Of course, this is a small number, but certainly an observation [of interest] when many patients are going to receive nivolumab as second-line in kidney cancer. This drug is still very active after PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies.”

FROM THE GENITOURINARY CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Cabozantinib appears more efficacious than does everolimus for a wide range of patients.

Major finding: Progression-free survival was better with cabozantinib than with everolimus across subgroups (hazard ratios, 0.22-0.84).

Data source: A subgroup analysis of 658 patients with previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma in a randomized phase III trial (METEOR).

Disclosures: Dr. Escudier disclosed that he has a consulting or advisory role with Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Exelixis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and that he receives honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Bayer. The study was funded in part by Exelixis. Dr. Pal disclosed that he receives honoraria from Astellas Pharma, Medivation, and Novartis; that he has a consulting or advisory role with Aveo, Genentech, Myriad Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Pfizer; and that he receives research funding from Medivation.

Disease Education

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Trading Kidneys: Innovative Program Could Save Thousands of Lives

While editing this month’s Renal Consult, I noted the mention of “paired kidney exchange” with particular interest. In 2005, I heard about a relatively new concept: matching two or more incompatible kidney donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. After conducting some research and interviewing experts, I wrote an article on paired kidney exchange for our sister publication, Clinician News. In the subsequent decade, the concept of paired exchange has expanded to the point that as many as 70 people have participated in a 35-kidney exchange. —AMH

Last year, almost 27,000 Americans received an organ transplant—a new national record, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services. Donations from living persons reached nearly 7,000, an increase of 2.3% from 2003. But despite these positive numbers, nearly 88,000 people are on the waiting list for an organ, and about 6,200 died last year before one became available.

But in some areas of the country, an innovative program is gaining momentum: paired kidney exchange, which puts together two or more incompatible donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. And while it will not close the gap between patients in need and those who receive, experts believe it could help thousands of people each year.

The real struggle is finding more willing donors. But Francis Delmonico, MD, Medical Director, New England Organ Bank, Newton, Massachusetts, says paired exchange is “an adjunct. When it can be of help, it’s helped a number of people already. And as with any of this, it’s a lot of work but it’s a tactic that we ought to try and apply anytime we can.”

“There are about 10,000 people who could be put into a program like this,” says Michael A. Rees, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo. “Once you put them into the program, we would hope that 2,000 to 3,000 per year could be matched up and we could do that many extra kidney transplants a year. And that would certainly help to close the gap.”

Continue for how it works >>

HOW IT WORKS

Paired kidney exchange got its start in the US at Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center, Baltimore, in 2001. The concept is simple: Recipient A needs a kidney and has a family member or friend, Donor A, who is willing to give. However, testing reveals that Donor A and Recipient A are incompatible. Meanwhile, Recipient B and Donor B find themselves with the same problem. But, it turns out, Donor B could give to Recipient A and Donor A could give to Recipient B. The patients and their donors are approached with the idea of an exchange, and if they agree, two people receive needed organs.

Twenty-two patients have received kidneys through the Johns Hopkins program, according to Robert A. Montgomery, MD, PhD, Director, Incompatible Kidney Transplant Programs (InKTP). Surgeons at Johns Hopkins have also expanded the exchange to three donor-recipient pairs; “triple swap” operations were performed at the hospital in 2003 and 2004.

“Everyone, when they come for an incompatible transplant, is offered the option of a paired exchange, because … if there’s any way to get a compatible kidney, that’s what you try for first,” says Janet Hiller, RN, MSN, Clinical Nurse Specialist, InKTP. “We’ve only had probably two out of a hundred [patients] who have thought, ‘No, I’d rather just get the kidney from my spouse or loved one.’”

“Patients are surprisingly open to this option, and almost all of them … request it when they are initially seen by me,” Montgomery told Clinician News via e-mail. “Some [recipients] have expressed apprehension about not knowing the donor and not being sure they have taken good care of their kidney. The donors have rarely expressed any concerns; they just want their loved one to receive a kidney…. It has universally been a positive experience.”

Ohio’s Rees first heard about paired exchange at a conference in 2001. He returned to his institution and consulted with the living donor coordinator to see if any pairs could be formed from people who had been willing to donate but unable due to blood type or other incompatibility problems. After identifying two pairs (out of 10 possibilities) for whom an exchange might work, Rees brought the patients and donors in for testing. But alas, the match wasn’t quite right.

“It became clear to me that if I really wanted to make this work, I needed a lot more than 10 pairs [to start with],” Rees says. “The numbers—if you try to match up people—go up logarithmically the more pairs that you have. So the chances you have of creating pairs go up exponentially.”

With this realization in mind, Rees set out to find someone willing to write a computer program that could identify potential matches from a larger bank of people pooled from several facilities. After some false starts—no computer programmer would work on the project for academic glory, the only reward Rees could offer—he convinced his father, Alan, to help. The senior Rees’ prototype was the basis for the current system, which links 10 transplant centers in Ohio.

Working with a larger pool of colleagues required numerous teleconference calls to iron out details for the statewide program. Among the questions were, “Are we going to make the donor travel, or are we going to cut the kidney out at home and ship the kidney in a box of ice to the place where it’s going to be transplanted?” he recalls. “And we decided that the donor has to travel.”

The first kidney exchange in the state of Ohio was performed in early November 2004. The third was scheduled for mid-April.

Creating one system to be shared by medical institutions that would normally be competitors took some work. “Trying to get us all to play in the same sandbox was very difficult,” Rees acknowledges. “But we did that; we stuck it out. And we all agreed to come up with something that we all think is a great idea and should help our patients.”

Delmonico, who is also a Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School and Visiting Surgeon in the Transplant Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, has also seen the gratifying cooperation between medical professionals. “Institutions are competitive in terms of medical care—that’s no mystery,” he says. “But in this instance, the physicians have been simply magnificent in trying to help patients. Innovative programs can be developed and sustained through the kind of collaboration that is going on here.”

The New England paired exchange program, dating back to 2002, is a collaboration involving a dozen hospitals. It started with a paper-and-pen effort (blood type–incompatible patients would be brought to the attention of Delmonico, who would then contact each transplant center, seeking others) but now has its own computer system.

New England also has another variation on the exchange program that is unique to the region, according to Delmonico. “Let’s say I wanted to give to you but I can’t. I’ll give to somebody on the list, and as a result of that donation, you would get a priority for the next available deceased donor kidney in New England,” he explains. “We’ve done that about 20 times now.”

Continue for going national >>

GOING NATIONAL

So where does paired exchange go from here? Johns Hopkins’ Montgomery organized a consensus meeting in March to discuss the possibility of creating a national network; Hiller, Rees, and Delmonico attended.

“I think our goal should be to one day have a national program,” Rees says. “But shipping somebody from Toledo down to Cincinnati is a lot easier to sell to a patient than shipping somebody from Toledo to Los Angeles. And the logistics of trying to do that when you have a whole different set of insurance companies … would be a lot more complicated. So, I think the way to begin is to do it on a more regional basis and prove that the concept works, that people can be satisfied with it, and then begin to expand it.”

Delmonico also thinks a national program is essential. “We need to enlarge the possibility of paired donation and exchange,” he says. “It will not happen successfully in a regional system. There aren’t enough patients that can be identified.” Questions to be answered before such a program could exist, Delmonico notes, include where the system will be based and who will administer it.

“There was a lot of agreement—though not total consensus—on the fact that UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing, would be the most likely place to ‘house’ and to manage the data,” Hiller reports. “They have all those systems in place already [and] are capable of managing this large database.”

Delmonico, as Vice President of UNOS, points out, “We have no authority to do that yet. Whether or not the country wants us to do that also remains to be determined.” But the UNOS Board of Directors is open to the idea; last year, they endorsed the concept of establishing a national paired exchange program with the understanding that details would have to be worked out over time, according to a UNOS spokesperson.

Another obstacle to widespread paired donation may be perceptions of it in the eyes of the government and critics: Could it be construed as a violation of the 1984 National Organ Transplant Act, which says that an organ should not be transplanted for a “value consideration”? Legal experts have assured Delmonico that paired exchanges can be interpreted as a gift.

“The government is also, properly, not wanting to see this as a slope toward buying and selling organs,” Delmonico says. “And I am adamantly opposed to that. In the instances that we’ve done paired exchange here, that’s not in the mix. That’s not our motivation, nor has it been the motivation of these donors. We wouldn’t do it if we felt that was the case.”

Montgomery says it will take several years to get a national system set up. But the bottom line for transplant surgeons is that a national paired kidney exchange program would do a world of good, two people at a time. “This is clearly what is best for our patients,” Montgomery says.

“The bigger we can get, if we can spread it nationally, the more people it will help,” Rees says. “And so we have to think of a way to do this so that we’re all satisfied that it’s moving forward in a way that will make everyone happy.”

Reprinted from Clinician News. 2005;9(5):cover, 3, 15.

While editing this month’s Renal Consult, I noted the mention of “paired kidney exchange” with particular interest. In 2005, I heard about a relatively new concept: matching two or more incompatible kidney donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. After conducting some research and interviewing experts, I wrote an article on paired kidney exchange for our sister publication, Clinician News. In the subsequent decade, the concept of paired exchange has expanded to the point that as many as 70 people have participated in a 35-kidney exchange. —AMH

Last year, almost 27,000 Americans received an organ transplant—a new national record, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services. Donations from living persons reached nearly 7,000, an increase of 2.3% from 2003. But despite these positive numbers, nearly 88,000 people are on the waiting list for an organ, and about 6,200 died last year before one became available.

But in some areas of the country, an innovative program is gaining momentum: paired kidney exchange, which puts together two or more incompatible donor-recipient pairs to create compatible matches. And while it will not close the gap between patients in need and those who receive, experts believe it could help thousands of people each year.

The real struggle is finding more willing donors. But Francis Delmonico, MD, Medical Director, New England Organ Bank, Newton, Massachusetts, says paired exchange is “an adjunct. When it can be of help, it’s helped a number of people already. And as with any of this, it’s a lot of work but it’s a tactic that we ought to try and apply anytime we can.”

“There are about 10,000 people who could be put into a program like this,” says Michael A. Rees, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, Medical College of Ohio, Toledo. “Once you put them into the program, we would hope that 2,000 to 3,000 per year could be matched up and we could do that many extra kidney transplants a year. And that would certainly help to close the gap.”

Continue for how it works >>

HOW IT WORKS

Paired kidney exchange got its start in the US at Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center, Baltimore, in 2001. The concept is simple: Recipient A needs a kidney and has a family member or friend, Donor A, who is willing to give. However, testing reveals that Donor A and Recipient A are incompatible. Meanwhile, Recipient B and Donor B find themselves with the same problem. But, it turns out, Donor B could give to Recipient A and Donor A could give to Recipient B. The patients and their donors are approached with the idea of an exchange, and if they agree, two people receive needed organs.

Twenty-two patients have received kidneys through the Johns Hopkins program, according to Robert A. Montgomery, MD, PhD, Director, Incompatible Kidney Transplant Programs (InKTP). Surgeons at Johns Hopkins have also expanded the exchange to three donor-recipient pairs; “triple swap” operations were performed at the hospital in 2003 and 2004.

“Everyone, when they come for an incompatible transplant, is offered the option of a paired exchange, because … if there’s any way to get a compatible kidney, that’s what you try for first,” says Janet Hiller, RN, MSN, Clinical Nurse Specialist, InKTP. “We’ve only had probably two out of a hundred [patients] who have thought, ‘No, I’d rather just get the kidney from my spouse or loved one.’”

“Patients are surprisingly open to this option, and almost all of them … request it when they are initially seen by me,” Montgomery told Clinician News via e-mail. “Some [recipients] have expressed apprehension about not knowing the donor and not being sure they have taken good care of their kidney. The donors have rarely expressed any concerns; they just want their loved one to receive a kidney…. It has universally been a positive experience.”

Ohio’s Rees first heard about paired exchange at a conference in 2001. He returned to his institution and consulted with the living donor coordinator to see if any pairs could be formed from people who had been willing to donate but unable due to blood type or other incompatibility problems. After identifying two pairs (out of 10 possibilities) for whom an exchange might work, Rees brought the patients and donors in for testing. But alas, the match wasn’t quite right.

“It became clear to me that if I really wanted to make this work, I needed a lot more than 10 pairs [to start with],” Rees says. “The numbers—if you try to match up people—go up logarithmically the more pairs that you have. So the chances you have of creating pairs go up exponentially.”

With this realization in mind, Rees set out to find someone willing to write a computer program that could identify potential matches from a larger bank of people pooled from several facilities. After some false starts—no computer programmer would work on the project for academic glory, the only reward Rees could offer—he convinced his father, Alan, to help. The senior Rees’ prototype was the basis for the current system, which links 10 transplant centers in Ohio.

Working with a larger pool of colleagues required numerous teleconference calls to iron out details for the statewide program. Among the questions were, “Are we going to make the donor travel, or are we going to cut the kidney out at home and ship the kidney in a box of ice to the place where it’s going to be transplanted?” he recalls. “And we decided that the donor has to travel.”

The first kidney exchange in the state of Ohio was performed in early November 2004. The third was scheduled for mid-April.

Creating one system to be shared by medical institutions that would normally be competitors took some work. “Trying to get us all to play in the same sandbox was very difficult,” Rees acknowledges. “But we did that; we stuck it out. And we all agreed to come up with something that we all think is a great idea and should help our patients.”

Delmonico, who is also a Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School and Visiting Surgeon in the Transplant Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, has also seen the gratifying cooperation between medical professionals. “Institutions are competitive in terms of medical care—that’s no mystery,” he says. “But in this instance, the physicians have been simply magnificent in trying to help patients. Innovative programs can be developed and sustained through the kind of collaboration that is going on here.”

The New England paired exchange program, dating back to 2002, is a collaboration involving a dozen hospitals. It started with a paper-and-pen effort (blood type–incompatible patients would be brought to the attention of Delmonico, who would then contact each transplant center, seeking others) but now has its own computer system.

New England also has another variation on the exchange program that is unique to the region, according to Delmonico. “Let’s say I wanted to give to you but I can’t. I’ll give to somebody on the list, and as a result of that donation, you would get a priority for the next available deceased donor kidney in New England,” he explains. “We’ve done that about 20 times now.”

Continue for going national >>

GOING NATIONAL

So where does paired exchange go from here? Johns Hopkins’ Montgomery organized a consensus meeting in March to discuss the possibility of creating a national network; Hiller, Rees, and Delmonico attended.

“I think our goal should be to one day have a national program,” Rees says. “But shipping somebody from Toledo down to Cincinnati is a lot easier to sell to a patient than shipping somebody from Toledo to Los Angeles. And the logistics of trying to do that when you have a whole different set of insurance companies … would be a lot more complicated. So, I think the way to begin is to do it on a more regional basis and prove that the concept works, that people can be satisfied with it, and then begin to expand it.”

Delmonico also thinks a national program is essential. “We need to enlarge the possibility of paired donation and exchange,” he says. “It will not happen successfully in a regional system. There aren’t enough patients that can be identified.” Questions to be answered before such a program could exist, Delmonico notes, include where the system will be based and who will administer it.

“There was a lot of agreement—though not total consensus—on the fact that UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing, would be the most likely place to ‘house’ and to manage the data,” Hiller reports. “They have all those systems in place already [and] are capable of managing this large database.”

Delmonico, as Vice President of UNOS, points out, “We have no authority to do that yet. Whether or not the country wants us to do that also remains to be determined.” But the UNOS Board of Directors is open to the idea; last year, they endorsed the concept of establishing a national paired exchange program with the understanding that details would have to be worked out over time, according to a UNOS spokesperson.

Another obstacle to widespread paired donation may be perceptions of it in the eyes of the government and critics: Could it be construed as a violation of the 1984 National Organ Transplant Act, which says that an organ should not be transplanted for a “value consideration”? Legal experts have assured Delmonico that paired exchanges can be interpreted as a gift.

“The government is also, properly, not wanting to see this as a slope toward buying and selling organs,” Delmonico says. “And I am adamantly opposed to that. In the instances that we’ve done paired exchange here, that’s not in the mix. That’s not our motivation, nor has it been the motivation of these donors. We wouldn’t do it if we felt that was the case.”

Montgomery says it will take several years to get a national system set up. But the bottom line for transplant surgeons is that a national paired kidney exchange program would do a world of good, two people at a time. “This is clearly what is best for our patients,” Montgomery says.

“The bigger we can get, if we can spread it nationally, the more people it will help,” Rees says. “And so we have to think of a way to do this so that we’re all satisfied that it’s moving forward in a way that will make everyone happy.”

Reprinted from Clinician News. 2005;9(5):cover, 3, 15.