User login

Acute Kidney Injury in the ICU: Medication Dosing

Q: As a hospitalist, I often see patients in our ICU develop AKI. Our pharmacist helps us with medication dosing, but sometimes I feel as if we're pulling a dose out of the air. Are there any studies or guidelines we can refer to?

Standard medication dosing adjustments for patients with impaired renal function are generally based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Because SCr is a lagging indicator of AKI, all methods of deriving eGFR from SCr are valid only when the patient is in a steady state.10

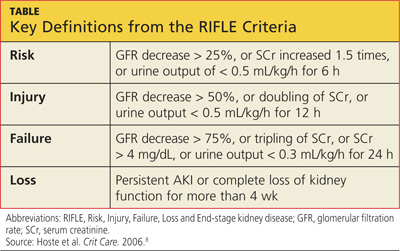

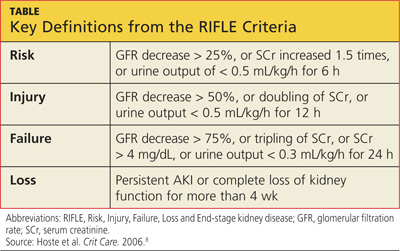

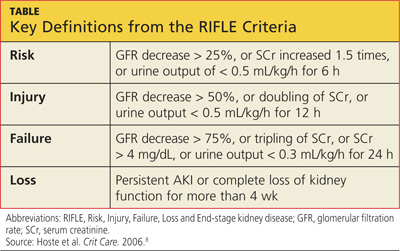

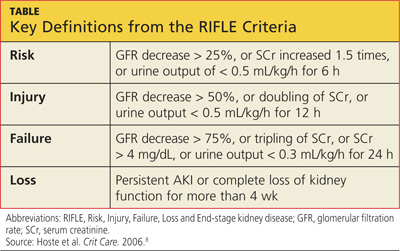

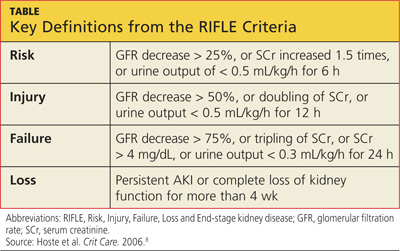

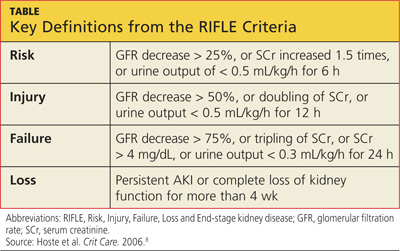

SCr has yet to be replaced by a real-time biomarker for AKI; this has left clinicians in the ICU setting with no simple or concise method for real-time assessment of renal function. In response to this common clinical conundrum, the RIFLE criteria,8 mentioned above, incorporates urinary output and relative increase in SCr as assessment criteria (see table for definitions).

This revised classification system may help the clinician define the severity of AKI in the acute setting. However, no medication dosing guidelines currently correspond with RIFLE staging. To further complicate the picture, there is evidence to suggest that AKI may affect drug metabolism through nonrenal pathways, such as hepatic clearance and transport functions.11 Add to this the potential for impaired drug absorption, distribution, and/or clearance due to variance in intravascular volume status, hepatic hypoperfusion, hypoxia, decreased protein synthesis, and competitive inhibition from concomitant medications—in short, the variables become too complex for calculating therapeutic drug dosing to be possible.

In the absence of definitive guidelines, the clinician plays a critical role in medication dosing adjustment for the ICU patient with AKI. The clinician must use astute clinical judgment to assess and prioritize the unique constellation of factors in any given case. Some of the factors that should be carefully considered when estimating medication dose adjustments in this context include RIFLE staging, trend in SCr, baseline SCr, nephrotoxicity of the medication to be administered, the drug's volume of distribution, the metabolic pathways of drug excretion, and the patient's weight.

A serum drug level, when available, is generally the best guide for dosing adjustment.10 The RIFLE staging does offer some clinical pearls that may be helpful. Though not evidence-based recommendations, these guides are commonly used in the clinical environment.

When patients are in the Failure stage, for example (see specifics in the table), they are generally considered to have an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min for purposes of drug dose adjustment (personal communication, Gideon Kayanan, PharmD, February 2013). However, patients in this category are much more likely than others to be undergoing dialysis, in which case the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are further complicated. In some cases, it may be appropriate to order creatinine clearance studies with a 6- or 12-hour urine collection and extrapolate a 24-hour creatinine clearance from this value.

The dearth of literature addressing this topic (despite the prevalence of AKI in the acute care setting) is a clear indication of the complexity of creating guidelines to address such a dynamic, multivariate pharmacokinetic process. Review of the literature clearly demonstrates that medical science in this area is not yet sufficiently developed to produce a standardized, data-driven guideline for dose adjustment calculation in patients with AKI.10 Until biomarkers are detected that offer real-time assessment of renal function and that can be used in the clinical setting, there will continue to be a component of estimation, analysis of trends, and reliance on clinical judgment in adjusting medication doses for inpatients with AKI. —AC

References

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: As a hospitalist, I often see patients in our ICU develop AKI. Our pharmacist helps us with medication dosing, but sometimes I feel as if we're pulling a dose out of the air. Are there any studies or guidelines we can refer to?

Standard medication dosing adjustments for patients with impaired renal function are generally based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Because SCr is a lagging indicator of AKI, all methods of deriving eGFR from SCr are valid only when the patient is in a steady state.10

SCr has yet to be replaced by a real-time biomarker for AKI; this has left clinicians in the ICU setting with no simple or concise method for real-time assessment of renal function. In response to this common clinical conundrum, the RIFLE criteria,8 mentioned above, incorporates urinary output and relative increase in SCr as assessment criteria (see table for definitions).

This revised classification system may help the clinician define the severity of AKI in the acute setting. However, no medication dosing guidelines currently correspond with RIFLE staging. To further complicate the picture, there is evidence to suggest that AKI may affect drug metabolism through nonrenal pathways, such as hepatic clearance and transport functions.11 Add to this the potential for impaired drug absorption, distribution, and/or clearance due to variance in intravascular volume status, hepatic hypoperfusion, hypoxia, decreased protein synthesis, and competitive inhibition from concomitant medications—in short, the variables become too complex for calculating therapeutic drug dosing to be possible.

In the absence of definitive guidelines, the clinician plays a critical role in medication dosing adjustment for the ICU patient with AKI. The clinician must use astute clinical judgment to assess and prioritize the unique constellation of factors in any given case. Some of the factors that should be carefully considered when estimating medication dose adjustments in this context include RIFLE staging, trend in SCr, baseline SCr, nephrotoxicity of the medication to be administered, the drug's volume of distribution, the metabolic pathways of drug excretion, and the patient's weight.

A serum drug level, when available, is generally the best guide for dosing adjustment.10 The RIFLE staging does offer some clinical pearls that may be helpful. Though not evidence-based recommendations, these guides are commonly used in the clinical environment.

When patients are in the Failure stage, for example (see specifics in the table), they are generally considered to have an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min for purposes of drug dose adjustment (personal communication, Gideon Kayanan, PharmD, February 2013). However, patients in this category are much more likely than others to be undergoing dialysis, in which case the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are further complicated. In some cases, it may be appropriate to order creatinine clearance studies with a 6- or 12-hour urine collection and extrapolate a 24-hour creatinine clearance from this value.

The dearth of literature addressing this topic (despite the prevalence of AKI in the acute care setting) is a clear indication of the complexity of creating guidelines to address such a dynamic, multivariate pharmacokinetic process. Review of the literature clearly demonstrates that medical science in this area is not yet sufficiently developed to produce a standardized, data-driven guideline for dose adjustment calculation in patients with AKI.10 Until biomarkers are detected that offer real-time assessment of renal function and that can be used in the clinical setting, there will continue to be a component of estimation, analysis of trends, and reliance on clinical judgment in adjusting medication doses for inpatients with AKI. —AC

References

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: As a hospitalist, I often see patients in our ICU develop AKI. Our pharmacist helps us with medication dosing, but sometimes I feel as if we're pulling a dose out of the air. Are there any studies or guidelines we can refer to?

Standard medication dosing adjustments for patients with impaired renal function are generally based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Because SCr is a lagging indicator of AKI, all methods of deriving eGFR from SCr are valid only when the patient is in a steady state.10

SCr has yet to be replaced by a real-time biomarker for AKI; this has left clinicians in the ICU setting with no simple or concise method for real-time assessment of renal function. In response to this common clinical conundrum, the RIFLE criteria,8 mentioned above, incorporates urinary output and relative increase in SCr as assessment criteria (see table for definitions).

This revised classification system may help the clinician define the severity of AKI in the acute setting. However, no medication dosing guidelines currently correspond with RIFLE staging. To further complicate the picture, there is evidence to suggest that AKI may affect drug metabolism through nonrenal pathways, such as hepatic clearance and transport functions.11 Add to this the potential for impaired drug absorption, distribution, and/or clearance due to variance in intravascular volume status, hepatic hypoperfusion, hypoxia, decreased protein synthesis, and competitive inhibition from concomitant medications—in short, the variables become too complex for calculating therapeutic drug dosing to be possible.

In the absence of definitive guidelines, the clinician plays a critical role in medication dosing adjustment for the ICU patient with AKI. The clinician must use astute clinical judgment to assess and prioritize the unique constellation of factors in any given case. Some of the factors that should be carefully considered when estimating medication dose adjustments in this context include RIFLE staging, trend in SCr, baseline SCr, nephrotoxicity of the medication to be administered, the drug's volume of distribution, the metabolic pathways of drug excretion, and the patient's weight.

A serum drug level, when available, is generally the best guide for dosing adjustment.10 The RIFLE staging does offer some clinical pearls that may be helpful. Though not evidence-based recommendations, these guides are commonly used in the clinical environment.

When patients are in the Failure stage, for example (see specifics in the table), they are generally considered to have an eGFR of less than 15 mL/min for purposes of drug dose adjustment (personal communication, Gideon Kayanan, PharmD, February 2013). However, patients in this category are much more likely than others to be undergoing dialysis, in which case the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are further complicated. In some cases, it may be appropriate to order creatinine clearance studies with a 6- or 12-hour urine collection and extrapolate a 24-hour creatinine clearance from this value.

The dearth of literature addressing this topic (despite the prevalence of AKI in the acute care setting) is a clear indication of the complexity of creating guidelines to address such a dynamic, multivariate pharmacokinetic process. Review of the literature clearly demonstrates that medical science in this area is not yet sufficiently developed to produce a standardized, data-driven guideline for dose adjustment calculation in patients with AKI.10 Until biomarkers are detected that offer real-time assessment of renal function and that can be used in the clinical setting, there will continue to be a component of estimation, analysis of trends, and reliance on clinical judgment in adjusting medication doses for inpatients with AKI. —AC

References

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Acute Kidney Injury in the ICU: Increasing Prevalence

Q: In 10 years as a hospitalist advanced practitioner, I've been seeing more and more AKI in our ICU. Is this true everywhere, or are we doing something wrong?

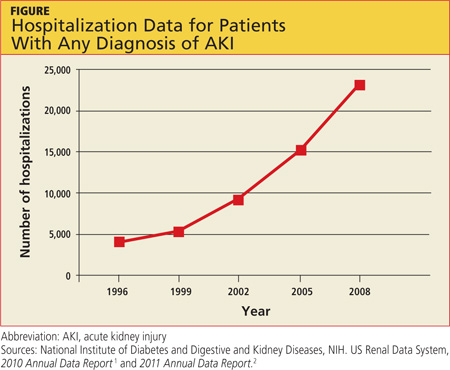

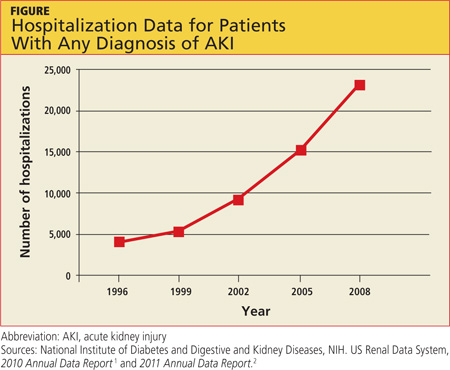

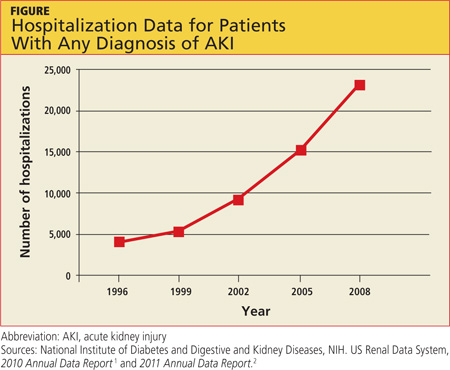

AKI is on the rise nationwide (see hospitalization data in figure), and it carries grim implications for patient outcomes.1-3 AKI with a rise in serum creatinine (SCr) as modest as 0.3 mg/dL is associated with a 70% increase in mortality risk. A rise in SCr exceeding 0.5 mg/dL has been associated with a 6.5-fold rise in the risk for death, even when adjusted for age and gender.4 This is higher than the mortality rate for inpatients admitted with cardiovascular disease or cancer, and just slightly more favorable than the mortality risk associated with sepsis (odds ratios, 6.6 and 7.5, respectively). AKI management in the non-ICU setting incurs the third highest median direct hospital cost, after acute MI and stroke.3

A recent retrospective analysis of hospital admissions nationwide from 2000 to 2009 shows a 10% annual increase in the incidence of AKI requiring dialysis, with at least doubling of the incidence and the number of deaths during that 10-year time period.5 Analyzing the incidence of AKI not requiring dialysis over time is more challenging because the criteria to define AKI have not been static; however, the rise in AKI requiring dialysis has mirrored the rise in AKI not requiring dialysis—suggesting that there is in fact an increased incidence of AKI, independent of variability in the defining criteria.3

Researchers reported in 2012 that during the previous year, the incidence of AKI among all hospitalized patients was 1 in 5.6 In the ICU, incidence of AKI has been reported at 39%, with a mortality rate of 25%.7 Based on the RIFLE criteria (a recently revised classification system whose name refers to Risk, Injury, Failure; Loss and End-stage kidney disease),8 as many as two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU meet criteria for a diagnosis of AKI.

Predictors for AKI include advancing age, baseline SCr below 1.2 mg/dL, the presence of diabetes, use of IV contrast, acute coronary syndromes, sepsis, liver or heart failure, and use of nephrotoxic medications.3

It is important for clinicians to recognize the implications of AKI, even when it manifests as a relatively minor rise in SCr. In addition to its association with poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, AKI increases the risk for chronic kidney disease and for readmissions within six months after hospital discharge.9 Unfortunately, our increased awareness of the implications of AKI in the inpatient setting has yet to translate into significant improvement in outcomes.

The evolution and availability of epidemiologic and outcome data, we can only hope, will serve to direct more resources and further study toward this issue. Clinicians' efforts to prevent and treat AKI can have profound implications for many of our nation's most chronically and critically ill patients. —AC

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: In 10 years as a hospitalist advanced practitioner, I've been seeing more and more AKI in our ICU. Is this true everywhere, or are we doing something wrong?

AKI is on the rise nationwide (see hospitalization data in figure), and it carries grim implications for patient outcomes.1-3 AKI with a rise in serum creatinine (SCr) as modest as 0.3 mg/dL is associated with a 70% increase in mortality risk. A rise in SCr exceeding 0.5 mg/dL has been associated with a 6.5-fold rise in the risk for death, even when adjusted for age and gender.4 This is higher than the mortality rate for inpatients admitted with cardiovascular disease or cancer, and just slightly more favorable than the mortality risk associated with sepsis (odds ratios, 6.6 and 7.5, respectively). AKI management in the non-ICU setting incurs the third highest median direct hospital cost, after acute MI and stroke.3

A recent retrospective analysis of hospital admissions nationwide from 2000 to 2009 shows a 10% annual increase in the incidence of AKI requiring dialysis, with at least doubling of the incidence and the number of deaths during that 10-year time period.5 Analyzing the incidence of AKI not requiring dialysis over time is more challenging because the criteria to define AKI have not been static; however, the rise in AKI requiring dialysis has mirrored the rise in AKI not requiring dialysis—suggesting that there is in fact an increased incidence of AKI, independent of variability in the defining criteria.3

Researchers reported in 2012 that during the previous year, the incidence of AKI among all hospitalized patients was 1 in 5.6 In the ICU, incidence of AKI has been reported at 39%, with a mortality rate of 25%.7 Based on the RIFLE criteria (a recently revised classification system whose name refers to Risk, Injury, Failure; Loss and End-stage kidney disease),8 as many as two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU meet criteria for a diagnosis of AKI.

Predictors for AKI include advancing age, baseline SCr below 1.2 mg/dL, the presence of diabetes, use of IV contrast, acute coronary syndromes, sepsis, liver or heart failure, and use of nephrotoxic medications.3

It is important for clinicians to recognize the implications of AKI, even when it manifests as a relatively minor rise in SCr. In addition to its association with poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, AKI increases the risk for chronic kidney disease and for readmissions within six months after hospital discharge.9 Unfortunately, our increased awareness of the implications of AKI in the inpatient setting has yet to translate into significant improvement in outcomes.

The evolution and availability of epidemiologic and outcome data, we can only hope, will serve to direct more resources and further study toward this issue. Clinicians' efforts to prevent and treat AKI can have profound implications for many of our nation's most chronically and critically ill patients. —AC

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Q: In 10 years as a hospitalist advanced practitioner, I've been seeing more and more AKI in our ICU. Is this true everywhere, or are we doing something wrong?

AKI is on the rise nationwide (see hospitalization data in figure), and it carries grim implications for patient outcomes.1-3 AKI with a rise in serum creatinine (SCr) as modest as 0.3 mg/dL is associated with a 70% increase in mortality risk. A rise in SCr exceeding 0.5 mg/dL has been associated with a 6.5-fold rise in the risk for death, even when adjusted for age and gender.4 This is higher than the mortality rate for inpatients admitted with cardiovascular disease or cancer, and just slightly more favorable than the mortality risk associated with sepsis (odds ratios, 6.6 and 7.5, respectively). AKI management in the non-ICU setting incurs the third highest median direct hospital cost, after acute MI and stroke.3

A recent retrospective analysis of hospital admissions nationwide from 2000 to 2009 shows a 10% annual increase in the incidence of AKI requiring dialysis, with at least doubling of the incidence and the number of deaths during that 10-year time period.5 Analyzing the incidence of AKI not requiring dialysis over time is more challenging because the criteria to define AKI have not been static; however, the rise in AKI requiring dialysis has mirrored the rise in AKI not requiring dialysis—suggesting that there is in fact an increased incidence of AKI, independent of variability in the defining criteria.3

Researchers reported in 2012 that during the previous year, the incidence of AKI among all hospitalized patients was 1 in 5.6 In the ICU, incidence of AKI has been reported at 39%, with a mortality rate of 25%.7 Based on the RIFLE criteria (a recently revised classification system whose name refers to Risk, Injury, Failure; Loss and End-stage kidney disease),8 as many as two-thirds of patients admitted to the ICU meet criteria for a diagnosis of AKI.

Predictors for AKI include advancing age, baseline SCr below 1.2 mg/dL, the presence of diabetes, use of IV contrast, acute coronary syndromes, sepsis, liver or heart failure, and use of nephrotoxic medications.3

It is important for clinicians to recognize the implications of AKI, even when it manifests as a relatively minor rise in SCr. In addition to its association with poor outcomes in hospitalized patients, AKI increases the risk for chronic kidney disease and for readmissions within six months after hospital discharge.9 Unfortunately, our increased awareness of the implications of AKI in the inpatient setting has yet to translate into significant improvement in outcomes.

The evolution and availability of epidemiologic and outcome data, we can only hope, will serve to direct more resources and further study toward this issue. Clinicians' efforts to prevent and treat AKI can have profound implications for many of our nation's most chronically and critically ill patients. —AC

REFERENCES

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2010 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2010/view/default.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

2. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH. US Renal Data System, 2011 Annual Data Report. www.usrds.org/2011/view/v2_00_appx.asp. Accessed March 5, 2013.

3. Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:844-861.

4. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, et al. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365-3370.

5. Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Dudley RA, et al. Temporal changes in incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;24:37-42.

6. Wang HE, Muntner P, Chertow GM, Warnock DG. Acute kidney injury and mortality in hospitalized patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35:349-355.

7. Nisula S, Kaukonen KM, Vaara ST, et al. Incidence, risk factors and 90-day mortality of patients with acute kidney injury in Finnish intensive care units: the FINNAKI study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:420-428.

8. Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73.

9. Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, et al. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:961-973.

10. Matzke GR, Aronoff GR, Atkinson AJ Jr, et al. Drug dosing consideration in patients with acute and chronic kidney disease: a clinical update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011;80:1122-1137.

11. Vilay AM, Churchwell MD, Mueller BA. Clinical review: drug metabolism and nonrenal clearance in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:235.

Acute Kidney Injury in an Unexpected Patient Population

Q: When I was doing sports physicals at the high school this week, several students asked if it was true that marijuana causes kidney failure. I had not heard this. Is it true? What should I tell teens who ask about this?

Synthetic marijuana, which goes by the street names of Spice, K2, Black Mamba, Fake Weed, Genie, and Zohai, is a mixture of herbs and spices that is sprayed with a synthetic THC-type compound.1 These can be sold over the Internet as "incense" or "bath salts." However, as is often the case with drugs purchased online or from a neighborhood dealer, other compounds toxic to humans can be cut and mixed in with these substances. While hypertension, nausea, cognitive dysfunction, and dizziness have all been associated with Spice, there has been a recent flurry of reports of severe and lasting cardiac and renal damage following use of these drugs.

In 2011, three cases of Spice-associated acute coronary syndrome were reported in the pediatric literature.2 In late 2012, four residents of the same Alabama community developed AKI after using Spice. While all four eventually recovered kidney function, they now have some permanent chronic kidney damage, and all four patients required kidney biopsies.3 Similarly, the CDC recently reported 14 cases of AKI in Wyoming that developed in patients who had smoked Spice.4 Six cases were reported from Oregon, two each from New York and Oklahoma, and one each from Rhode Island and Kansas. Half of the case patients required hemodialysis and kidney biopsy. All had residual chronic kidney disease after recovery.4

The patients' presentations were similar: they were all young and healthy with no history of kidney problems—then, wham! After they had smoked Spice, severe nausea and vomiting with flank pain took them to the ER. On admission, serum creatinine (SCr) was mildly abnormal, but it rose to an average of 8 mg/dL, with one patient's SCr peaking at 21 mg/dL.4

While there have been no Spice-associated deaths reported, the critical care needed for these young people included hemodialysis. Perhaps a graphic description of the standard 15-gauge needles we use for dialysis would be helpful during a discussion of drug use with teens.

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA, Metropolitan Nephrology, Alexandria, VA, and Clinton, MD

REFERENCES

1. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Fact Sheet: K2 or Spice. www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/K2_Spice.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

2. Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622-e1627.

3. Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, et al. AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

4. CDC. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93-98.

Q: When I was doing sports physicals at the high school this week, several students asked if it was true that marijuana causes kidney failure. I had not heard this. Is it true? What should I tell teens who ask about this?

Synthetic marijuana, which goes by the street names of Spice, K2, Black Mamba, Fake Weed, Genie, and Zohai, is a mixture of herbs and spices that is sprayed with a synthetic THC-type compound.1 These can be sold over the Internet as "incense" or "bath salts." However, as is often the case with drugs purchased online or from a neighborhood dealer, other compounds toxic to humans can be cut and mixed in with these substances. While hypertension, nausea, cognitive dysfunction, and dizziness have all been associated with Spice, there has been a recent flurry of reports of severe and lasting cardiac and renal damage following use of these drugs.

In 2011, three cases of Spice-associated acute coronary syndrome were reported in the pediatric literature.2 In late 2012, four residents of the same Alabama community developed AKI after using Spice. While all four eventually recovered kidney function, they now have some permanent chronic kidney damage, and all four patients required kidney biopsies.3 Similarly, the CDC recently reported 14 cases of AKI in Wyoming that developed in patients who had smoked Spice.4 Six cases were reported from Oregon, two each from New York and Oklahoma, and one each from Rhode Island and Kansas. Half of the case patients required hemodialysis and kidney biopsy. All had residual chronic kidney disease after recovery.4

The patients' presentations were similar: they were all young and healthy with no history of kidney problems—then, wham! After they had smoked Spice, severe nausea and vomiting with flank pain took them to the ER. On admission, serum creatinine (SCr) was mildly abnormal, but it rose to an average of 8 mg/dL, with one patient's SCr peaking at 21 mg/dL.4

While there have been no Spice-associated deaths reported, the critical care needed for these young people included hemodialysis. Perhaps a graphic description of the standard 15-gauge needles we use for dialysis would be helpful during a discussion of drug use with teens.

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA, Metropolitan Nephrology, Alexandria, VA, and Clinton, MD

REFERENCES

1. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Fact Sheet: K2 or Spice. www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/K2_Spice.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

2. Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622-e1627.

3. Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, et al. AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

4. CDC. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93-98.

Q: When I was doing sports physicals at the high school this week, several students asked if it was true that marijuana causes kidney failure. I had not heard this. Is it true? What should I tell teens who ask about this?

Synthetic marijuana, which goes by the street names of Spice, K2, Black Mamba, Fake Weed, Genie, and Zohai, is a mixture of herbs and spices that is sprayed with a synthetic THC-type compound.1 These can be sold over the Internet as "incense" or "bath salts." However, as is often the case with drugs purchased online or from a neighborhood dealer, other compounds toxic to humans can be cut and mixed in with these substances. While hypertension, nausea, cognitive dysfunction, and dizziness have all been associated with Spice, there has been a recent flurry of reports of severe and lasting cardiac and renal damage following use of these drugs.

In 2011, three cases of Spice-associated acute coronary syndrome were reported in the pediatric literature.2 In late 2012, four residents of the same Alabama community developed AKI after using Spice. While all four eventually recovered kidney function, they now have some permanent chronic kidney damage, and all four patients required kidney biopsies.3 Similarly, the CDC recently reported 14 cases of AKI in Wyoming that developed in patients who had smoked Spice.4 Six cases were reported from Oregon, two each from New York and Oklahoma, and one each from Rhode Island and Kansas. Half of the case patients required hemodialysis and kidney biopsy. All had residual chronic kidney disease after recovery.4

The patients' presentations were similar: they were all young and healthy with no history of kidney problems—then, wham! After they had smoked Spice, severe nausea and vomiting with flank pain took them to the ER. On admission, serum creatinine (SCr) was mildly abnormal, but it rose to an average of 8 mg/dL, with one patient's SCr peaking at 21 mg/dL.4

While there have been no Spice-associated deaths reported, the critical care needed for these young people included hemodialysis. Perhaps a graphic description of the standard 15-gauge needles we use for dialysis would be helpful during a discussion of drug use with teens.

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA, Metropolitan Nephrology, Alexandria, VA, and Clinton, MD

REFERENCES

1. US Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Fact Sheet: K2 or Spice. www.justice.gov/dea/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/K2_Spice.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2013.

2. Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622-e1627.

3. Bhanushali GK, Jain G, Fatima H, et al. AKI associated with synthetic cannabinoids: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Dec 14. [Epub ahead of print]

4. CDC. Acute kidney injury associated with synthetic cannabinoid use—multiple states, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:93-98.

NSAIDs for BPH

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is an uncommon cause of mortality but a common cause of morbidity.

More than 80% of men aged older than 80 years have histologic evidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). As most of us know, the most common symptoms of BPH are urinary frequency, nocturia, hesitancy, and weak urine stream. But it seems like nocturia is the source of most complaints in my panel.

Interestingly, many men will experience stabilization or improvement over time without therapy. We likely do not remember this, because men who present to us are not typically enamored with the idea of "watchful waiting" when they are up all night standing at the latrine. But in fact, 38% of men will have symptom improvement over 2.6 to 5 years of follow-up without intervention.

Treatment is symptom driven. Treatment modality selections are cost and convenience driven. Many of us will reach for an alpha-adrenergic antagonist or a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor as first-line therapy for patients with mild but annoying symptoms.

But how many of us consider NSAIDs in this setting?

Dr. Arman Kahokehr and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the literature examining the effects of NSAIDs in the treatment of men with BPH. Trials were included if they were randomized and included objective outcomes such as urologic symptom scales or urodynamics (BJU Int. 2013;111:304-11).

Three randomized trials enrolling 183 men and lasting 4-24 weeks were included in the meta-analysis. The trials used rofecoxib plus finasteride, celecoxib, and tenoxicam plus doxazosin. NSAIDs improved scores on the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS; P less than .001) and increased urine flow (0.89 mL/s; P = .01). No increased side effects were observed.

The authors highlight that inflammatory infiltration is seen in 43%-98% of BPH tissue, and men with acute or chronic inflammation have larger prostate volumes.

COX-2 inhibitors were used in the included studies, but nonselective NSAIDs may have as powerful an effect on the inflammatory process associated with BPH – and may be associated with less concern for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The long-term effects of NSAIDs on kidney function and the gastrointestinal mucosa, especially in older patients, need to be considered.

But the use of NSAIDs in combination with other BPH pharmacologic agents before changing doses, medications, or intervention approach may be an attractive short-term clinical option.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are those of the author.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is an uncommon cause of mortality but a common cause of morbidity.

More than 80% of men aged older than 80 years have histologic evidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). As most of us know, the most common symptoms of BPH are urinary frequency, nocturia, hesitancy, and weak urine stream. But it seems like nocturia is the source of most complaints in my panel.

Interestingly, many men will experience stabilization or improvement over time without therapy. We likely do not remember this, because men who present to us are not typically enamored with the idea of "watchful waiting" when they are up all night standing at the latrine. But in fact, 38% of men will have symptom improvement over 2.6 to 5 years of follow-up without intervention.

Treatment is symptom driven. Treatment modality selections are cost and convenience driven. Many of us will reach for an alpha-adrenergic antagonist or a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor as first-line therapy for patients with mild but annoying symptoms.

But how many of us consider NSAIDs in this setting?

Dr. Arman Kahokehr and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the literature examining the effects of NSAIDs in the treatment of men with BPH. Trials were included if they were randomized and included objective outcomes such as urologic symptom scales or urodynamics (BJU Int. 2013;111:304-11).

Three randomized trials enrolling 183 men and lasting 4-24 weeks were included in the meta-analysis. The trials used rofecoxib plus finasteride, celecoxib, and tenoxicam plus doxazosin. NSAIDs improved scores on the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS; P less than .001) and increased urine flow (0.89 mL/s; P = .01). No increased side effects were observed.

The authors highlight that inflammatory infiltration is seen in 43%-98% of BPH tissue, and men with acute or chronic inflammation have larger prostate volumes.

COX-2 inhibitors were used in the included studies, but nonselective NSAIDs may have as powerful an effect on the inflammatory process associated with BPH – and may be associated with less concern for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The long-term effects of NSAIDs on kidney function and the gastrointestinal mucosa, especially in older patients, need to be considered.

But the use of NSAIDs in combination with other BPH pharmacologic agents before changing doses, medications, or intervention approach may be an attractive short-term clinical option.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are those of the author.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia is an uncommon cause of mortality but a common cause of morbidity.

More than 80% of men aged older than 80 years have histologic evidence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). As most of us know, the most common symptoms of BPH are urinary frequency, nocturia, hesitancy, and weak urine stream. But it seems like nocturia is the source of most complaints in my panel.

Interestingly, many men will experience stabilization or improvement over time without therapy. We likely do not remember this, because men who present to us are not typically enamored with the idea of "watchful waiting" when they are up all night standing at the latrine. But in fact, 38% of men will have symptom improvement over 2.6 to 5 years of follow-up without intervention.

Treatment is symptom driven. Treatment modality selections are cost and convenience driven. Many of us will reach for an alpha-adrenergic antagonist or a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor as first-line therapy for patients with mild but annoying symptoms.

But how many of us consider NSAIDs in this setting?

Dr. Arman Kahokehr and colleagues conducted a systematic review of the literature examining the effects of NSAIDs in the treatment of men with BPH. Trials were included if they were randomized and included objective outcomes such as urologic symptom scales or urodynamics (BJU Int. 2013;111:304-11).

Three randomized trials enrolling 183 men and lasting 4-24 weeks were included in the meta-analysis. The trials used rofecoxib plus finasteride, celecoxib, and tenoxicam plus doxazosin. NSAIDs improved scores on the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS; P less than .001) and increased urine flow (0.89 mL/s; P = .01). No increased side effects were observed.

The authors highlight that inflammatory infiltration is seen in 43%-98% of BPH tissue, and men with acute or chronic inflammation have larger prostate volumes.

COX-2 inhibitors were used in the included studies, but nonselective NSAIDs may have as powerful an effect on the inflammatory process associated with BPH – and may be associated with less concern for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. The long-term effects of NSAIDs on kidney function and the gastrointestinal mucosa, especially in older patients, need to be considered.

But the use of NSAIDs in combination with other BPH pharmacologic agents before changing doses, medications, or intervention approach may be an attractive short-term clinical option.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are those of the author.

Bilateral adrenal masses

To the Editor: In their article “The clinical picture: bilateral adrenal masses” in the December 2012 issue,1 Drs. Saberi and Esfandiari provide excellent points about adrenal hemorrhage as a differential diagnosis for adrenal masses. However, there are two points worth emphasizing when mentioning this diagnosis, especially in the case they presented.

Drs. Saberi and Esfandiari cryptically mention this patient’s coagulopathy (with thrombocytopenia and a rise in creatinine) and anticoagulation as the probable causes of adrenal hemorrhage. We wonder if a diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) was overlooked. Even though overt Addison disease is reported in only 0.4% of patients with APS2 and APS is diagnosed in fewer than 0.5% of all patients with Addison disease,3 we think that in this case, since the patient initially presented with an arterial thrombus in the abdominal aorta, screening for APS would have been warranted.

Second, though it is rare, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage with normal imaging on initial presentation has been described,2,4 which raises this additional question: Should screening for adrenal insufficiency in a patient with possible APS or other coagulopathy be done early while waiting for repeat computed tomography to reveal hemorrhage? Occasionally, intraparenchymal microhemorrhages may not be recognized by sectional imaging but can nonetheless compromise adrenal function.4

- Saberi S, Esfandiari NH. The clinical picture: bilateral adrenal masses. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:841–842.

- Espinosa G, Santos E, Cervera R, et al. Adrenal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic characteristics of 86 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003; 82:106–118.

- Presotto F, Fornasini F, Betterle C, Federspil G, Rossato M. Acute adrenal failure as the heralding symptom of primary antiphospholipid syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol 2005; 153:507–514.

- Satta MA, Corsello SM, Della Casa S, et al. Adrenal insufficiency as the first clinical manifestation of the primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000; 52:123–126.

To the Editor: In their article “The clinical picture: bilateral adrenal masses” in the December 2012 issue,1 Drs. Saberi and Esfandiari provide excellent points about adrenal hemorrhage as a differential diagnosis for adrenal masses. However, there are two points worth emphasizing when mentioning this diagnosis, especially in the case they presented.

Drs. Saberi and Esfandiari cryptically mention this patient’s coagulopathy (with thrombocytopenia and a rise in creatinine) and anticoagulation as the probable causes of adrenal hemorrhage. We wonder if a diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) was overlooked. Even though overt Addison disease is reported in only 0.4% of patients with APS2 and APS is diagnosed in fewer than 0.5% of all patients with Addison disease,3 we think that in this case, since the patient initially presented with an arterial thrombus in the abdominal aorta, screening for APS would have been warranted.

Second, though it is rare, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage with normal imaging on initial presentation has been described,2,4 which raises this additional question: Should screening for adrenal insufficiency in a patient with possible APS or other coagulopathy be done early while waiting for repeat computed tomography to reveal hemorrhage? Occasionally, intraparenchymal microhemorrhages may not be recognized by sectional imaging but can nonetheless compromise adrenal function.4

To the Editor: In their article “The clinical picture: bilateral adrenal masses” in the December 2012 issue,1 Drs. Saberi and Esfandiari provide excellent points about adrenal hemorrhage as a differential diagnosis for adrenal masses. However, there are two points worth emphasizing when mentioning this diagnosis, especially in the case they presented.

Drs. Saberi and Esfandiari cryptically mention this patient’s coagulopathy (with thrombocytopenia and a rise in creatinine) and anticoagulation as the probable causes of adrenal hemorrhage. We wonder if a diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) was overlooked. Even though overt Addison disease is reported in only 0.4% of patients with APS2 and APS is diagnosed in fewer than 0.5% of all patients with Addison disease,3 we think that in this case, since the patient initially presented with an arterial thrombus in the abdominal aorta, screening for APS would have been warranted.

Second, though it is rare, bilateral adrenal hemorrhage with normal imaging on initial presentation has been described,2,4 which raises this additional question: Should screening for adrenal insufficiency in a patient with possible APS or other coagulopathy be done early while waiting for repeat computed tomography to reveal hemorrhage? Occasionally, intraparenchymal microhemorrhages may not be recognized by sectional imaging but can nonetheless compromise adrenal function.4

- Saberi S, Esfandiari NH. The clinical picture: bilateral adrenal masses. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:841–842.

- Espinosa G, Santos E, Cervera R, et al. Adrenal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic characteristics of 86 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003; 82:106–118.

- Presotto F, Fornasini F, Betterle C, Federspil G, Rossato M. Acute adrenal failure as the heralding symptom of primary antiphospholipid syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol 2005; 153:507–514.

- Satta MA, Corsello SM, Della Casa S, et al. Adrenal insufficiency as the first clinical manifestation of the primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000; 52:123–126.

- Saberi S, Esfandiari NH. The clinical picture: bilateral adrenal masses. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:841–842.

- Espinosa G, Santos E, Cervera R, et al. Adrenal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic characteristics of 86 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003; 82:106–118.

- Presotto F, Fornasini F, Betterle C, Federspil G, Rossato M. Acute adrenal failure as the heralding symptom of primary antiphospholipid syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol 2005; 153:507–514.

- Satta MA, Corsello SM, Della Casa S, et al. Adrenal insufficiency as the first clinical manifestation of the primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000; 52:123–126.

Even mild kidney dysfunction raises recurrent stroke risk

Diminished renal function is an independent risk factor for recurrent stroke within the first 6 months following hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke, Dr. Abraham Thomas reported at the International Stroke Conference.

The short-term risk of recurrent stroke climbs in stepwise fashion with decreasing renal function. Even patients categorized as having stage 2 renal function by National Kidney Foundation criteria – those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60-89 mL/min/1.73 m2 – have a 60% increased risk compared with those who have an estimated GFR of 90 or greater, according to Dr. Thomas of the University of California, San Francisco.

He presented an observational study involving 2,882 patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke to 12 Northern California Kaiser Permanente hospitals during 2004-2007. Twenty-four percent had stage 1 renal function upon admission, with an eGFR of at least 90 mL/min/1.73 m2. Forty-seven percent were stage 2, 25% were stage 3 as defined by an eGFR of 30-59, and the rest had stage 4 chronic kidney disease.

In a multivariate analysis, stage 2 renal function was independently associated with a 60% greater risk of recurrent stroke within 6 months compared with those who were stage 1. Patients with stage 3 renal function were at 70% greater risk than were those who were stage 1, while stage 4 patients were at 80% increased risk.

Renal dysfunction is an established risk factor for first-time cardiovascular events, including stroke. But the relationship between renal function and short-term risk of recurrent stroke has not previously been scrutinized.

One possible mechanism by which impaired renal function might predict an increased short-term risk of recurrent stroke involves poor blood pressure control, Dr. Thomas observed. The prevalence of hypertension was 19% with stage 1 renal function, 24% in those who were stage 2, and 26% in patients with stage 3 or 4 renal function. And at 6 months’ follow-up, blood pressure control was less than half as common among stage 4 patients than in those who were stages 1-3.

The conference was sponsored by the American Heart Association. Dr. Thomas reported having no financial conflicts.

National Kidney Foundation, glomerular, he University of California

Diminished renal function is an independent risk factor for recurrent stroke within the first 6 months following hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke, Dr. Abraham Thomas reported at the International Stroke Conference.

The short-term risk of recurrent stroke climbs in stepwise fashion with decreasing renal function. Even patients categorized as having stage 2 renal function by National Kidney Foundation criteria – those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60-89 mL/min/1.73 m2 – have a 60% increased risk compared with those who have an estimated GFR of 90 or greater, according to Dr. Thomas of the University of California, San Francisco.

He presented an observational study involving 2,882 patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke to 12 Northern California Kaiser Permanente hospitals during 2004-2007. Twenty-four percent had stage 1 renal function upon admission, with an eGFR of at least 90 mL/min/1.73 m2. Forty-seven percent were stage 2, 25% were stage 3 as defined by an eGFR of 30-59, and the rest had stage 4 chronic kidney disease.

In a multivariate analysis, stage 2 renal function was independently associated with a 60% greater risk of recurrent stroke within 6 months compared with those who were stage 1. Patients with stage 3 renal function were at 70% greater risk than were those who were stage 1, while stage 4 patients were at 80% increased risk.

Renal dysfunction is an established risk factor for first-time cardiovascular events, including stroke. But the relationship between renal function and short-term risk of recurrent stroke has not previously been scrutinized.

One possible mechanism by which impaired renal function might predict an increased short-term risk of recurrent stroke involves poor blood pressure control, Dr. Thomas observed. The prevalence of hypertension was 19% with stage 1 renal function, 24% in those who were stage 2, and 26% in patients with stage 3 or 4 renal function. And at 6 months’ follow-up, blood pressure control was less than half as common among stage 4 patients than in those who were stages 1-3.

The conference was sponsored by the American Heart Association. Dr. Thomas reported having no financial conflicts.

Diminished renal function is an independent risk factor for recurrent stroke within the first 6 months following hospitalization for an acute ischemic stroke, Dr. Abraham Thomas reported at the International Stroke Conference.

The short-term risk of recurrent stroke climbs in stepwise fashion with decreasing renal function. Even patients categorized as having stage 2 renal function by National Kidney Foundation criteria – those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60-89 mL/min/1.73 m2 – have a 60% increased risk compared with those who have an estimated GFR of 90 or greater, according to Dr. Thomas of the University of California, San Francisco.

He presented an observational study involving 2,882 patients admitted with acute ischemic stroke to 12 Northern California Kaiser Permanente hospitals during 2004-2007. Twenty-four percent had stage 1 renal function upon admission, with an eGFR of at least 90 mL/min/1.73 m2. Forty-seven percent were stage 2, 25% were stage 3 as defined by an eGFR of 30-59, and the rest had stage 4 chronic kidney disease.

In a multivariate analysis, stage 2 renal function was independently associated with a 60% greater risk of recurrent stroke within 6 months compared with those who were stage 1. Patients with stage 3 renal function were at 70% greater risk than were those who were stage 1, while stage 4 patients were at 80% increased risk.

Renal dysfunction is an established risk factor for first-time cardiovascular events, including stroke. But the relationship between renal function and short-term risk of recurrent stroke has not previously been scrutinized.

One possible mechanism by which impaired renal function might predict an increased short-term risk of recurrent stroke involves poor blood pressure control, Dr. Thomas observed. The prevalence of hypertension was 19% with stage 1 renal function, 24% in those who were stage 2, and 26% in patients with stage 3 or 4 renal function. And at 6 months’ follow-up, blood pressure control was less than half as common among stage 4 patients than in those who were stages 1-3.

The conference was sponsored by the American Heart Association. Dr. Thomas reported having no financial conflicts.

National Kidney Foundation, glomerular, he University of California

National Kidney Foundation, glomerular, he University of California

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Survival higher with surveillance of small kidney tumors

Older patients with small kidney tumors are up to 70% less likely to die from any cause when managed by watchful waiting rather than by surgery, based on findings from a large retrospective study.

Surveillance appears to be safe for these small lesions, with a kidney cancer mortality of just 3% over a 5-year period. In addition, watchful waiting seems to confer a cardiovascular benefit; these patients had a 49% lower cardiac mortality risk compared with that for patients who had kidney surgery, said lead author Dr. William C. Huang of New York University Medical Center.

The link between kidney surgery and heart problems is probably mediated by compromised kidney function, Dr. Huang said. "It’s believed that when surgery takes excess normal kidney tissue, it hastens the acceleration of kidney failure," leading to cardiovascular problems, he said.

The study findings are going to be increasingly valuable as imaging turns up more and more incidental asymptomatic kidney tumors. Last year alone, about 65,000 of these lesions were diagnosed, most of them during a work-up for other abdominal complaints.

While the trend toward surveillance of small asymptomatic lesions is growing, Dr. Huang said surgery is still the treatment mode for more than half of cases. Most procedures in the retrospective study were radical nephrectomies, with kidney removal in about half of those. "The majority of these small lesions could be removed laparoscopically, but even then you’re taking out normal kidney tissue that you might really want back someday," he said at a press briefing at the Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

"Physicians can comfortably tell an elderly patient, especially a patient who is not healthy enough to tolerate general anesthesia and surgery, that the likelihood of dying of kidney cancer is low and that kidney surgery is unlikely to extend their lives," he said. "However, since it is difficult to identify which tumors will become lethal, elderly patients who are completely healthy and have an extended life expectancy, may opt for surgery."

The study examined mortality data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database for 8,317 patients, aged 66 years or older, who were diagnosed from 2002 to 2007 with kidney tumors smaller than 1.5 cm. The patients were followed for a median of 59 months; 78% were managed with surgery and 22%, with surveillance. The use of surveillance increased over the course of the study, from about 25% in 2002 to almost 40% in 2007.

Over the study period, 2,078 (25%) of the patients died, including 277 (3%) who died of kidney cancer. At least one cardiovascular event occurred in 24% of the patients.

Kidney cancer mortality rates did not vary between the treatment groups. However, surgical patients had a significantly increased risk of death from any cause. At 7-36 months, those who had surveillance were 30% less likely to have died than those managed by surgery (hazard ratio, 0.70). After 36 months, patients were 63% less likely to have died if their tumors were managed by surveillance instead of surgery (HR, 0.37).

Dr. Huang also demonstrated that those in the surveillance group experienced a significant cardiovascular benefit as well. By the end of the study, 25% of the deaths were due to a cardiovascular event. Patients in the surveillance group had a 49% reduction in the chance of an event.

Dr. Huang said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Older patients with small kidney tumors are up to 70% less likely to die from any cause when managed by watchful waiting rather than by surgery, based on findings from a large retrospective study.

Surveillance appears to be safe for these small lesions, with a kidney cancer mortality of just 3% over a 5-year period. In addition, watchful waiting seems to confer a cardiovascular benefit; these patients had a 49% lower cardiac mortality risk compared with that for patients who had kidney surgery, said lead author Dr. William C. Huang of New York University Medical Center.

The link between kidney surgery and heart problems is probably mediated by compromised kidney function, Dr. Huang said. "It’s believed that when surgery takes excess normal kidney tissue, it hastens the acceleration of kidney failure," leading to cardiovascular problems, he said.

The study findings are going to be increasingly valuable as imaging turns up more and more incidental asymptomatic kidney tumors. Last year alone, about 65,000 of these lesions were diagnosed, most of them during a work-up for other abdominal complaints.

While the trend toward surveillance of small asymptomatic lesions is growing, Dr. Huang said surgery is still the treatment mode for more than half of cases. Most procedures in the retrospective study were radical nephrectomies, with kidney removal in about half of those. "The majority of these small lesions could be removed laparoscopically, but even then you’re taking out normal kidney tissue that you might really want back someday," he said at a press briefing at the Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

"Physicians can comfortably tell an elderly patient, especially a patient who is not healthy enough to tolerate general anesthesia and surgery, that the likelihood of dying of kidney cancer is low and that kidney surgery is unlikely to extend their lives," he said. "However, since it is difficult to identify which tumors will become lethal, elderly patients who are completely healthy and have an extended life expectancy, may opt for surgery."

The study examined mortality data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database for 8,317 patients, aged 66 years or older, who were diagnosed from 2002 to 2007 with kidney tumors smaller than 1.5 cm. The patients were followed for a median of 59 months; 78% were managed with surgery and 22%, with surveillance. The use of surveillance increased over the course of the study, from about 25% in 2002 to almost 40% in 2007.

Over the study period, 2,078 (25%) of the patients died, including 277 (3%) who died of kidney cancer. At least one cardiovascular event occurred in 24% of the patients.

Kidney cancer mortality rates did not vary between the treatment groups. However, surgical patients had a significantly increased risk of death from any cause. At 7-36 months, those who had surveillance were 30% less likely to have died than those managed by surgery (hazard ratio, 0.70). After 36 months, patients were 63% less likely to have died if their tumors were managed by surveillance instead of surgery (HR, 0.37).

Dr. Huang also demonstrated that those in the surveillance group experienced a significant cardiovascular benefit as well. By the end of the study, 25% of the deaths were due to a cardiovascular event. Patients in the surveillance group had a 49% reduction in the chance of an event.

Dr. Huang said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Older patients with small kidney tumors are up to 70% less likely to die from any cause when managed by watchful waiting rather than by surgery, based on findings from a large retrospective study.

Surveillance appears to be safe for these small lesions, with a kidney cancer mortality of just 3% over a 5-year period. In addition, watchful waiting seems to confer a cardiovascular benefit; these patients had a 49% lower cardiac mortality risk compared with that for patients who had kidney surgery, said lead author Dr. William C. Huang of New York University Medical Center.

The link between kidney surgery and heart problems is probably mediated by compromised kidney function, Dr. Huang said. "It’s believed that when surgery takes excess normal kidney tissue, it hastens the acceleration of kidney failure," leading to cardiovascular problems, he said.

The study findings are going to be increasingly valuable as imaging turns up more and more incidental asymptomatic kidney tumors. Last year alone, about 65,000 of these lesions were diagnosed, most of them during a work-up for other abdominal complaints.

While the trend toward surveillance of small asymptomatic lesions is growing, Dr. Huang said surgery is still the treatment mode for more than half of cases. Most procedures in the retrospective study were radical nephrectomies, with kidney removal in about half of those. "The majority of these small lesions could be removed laparoscopically, but even then you’re taking out normal kidney tissue that you might really want back someday," he said at a press briefing at the Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, sponsored by the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology.

"Physicians can comfortably tell an elderly patient, especially a patient who is not healthy enough to tolerate general anesthesia and surgery, that the likelihood of dying of kidney cancer is low and that kidney surgery is unlikely to extend their lives," he said. "However, since it is difficult to identify which tumors will become lethal, elderly patients who are completely healthy and have an extended life expectancy, may opt for surgery."

The study examined mortality data in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database for 8,317 patients, aged 66 years or older, who were diagnosed from 2002 to 2007 with kidney tumors smaller than 1.5 cm. The patients were followed for a median of 59 months; 78% were managed with surgery and 22%, with surveillance. The use of surveillance increased over the course of the study, from about 25% in 2002 to almost 40% in 2007.

Over the study period, 2,078 (25%) of the patients died, including 277 (3%) who died of kidney cancer. At least one cardiovascular event occurred in 24% of the patients.

Kidney cancer mortality rates did not vary between the treatment groups. However, surgical patients had a significantly increased risk of death from any cause. At 7-36 months, those who had surveillance were 30% less likely to have died than those managed by surgery (hazard ratio, 0.70). After 36 months, patients were 63% less likely to have died if their tumors were managed by surveillance instead of surgery (HR, 0.37).

Dr. Huang also demonstrated that those in the surveillance group experienced a significant cardiovascular benefit as well. By the end of the study, 25% of the deaths were due to a cardiovascular event. Patients in the surveillance group had a 49% reduction in the chance of an event.

Dr. Huang said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE GENITOURINARY CANCERS SYMPOSIUM

Major Finding: After 36 months, patients were 63% less likely to have died if their tumors were managed by surveillance instead of surgery (HR, 0.37).

Data Source: Mortality data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database for 8,317 patients, aged 66 years or older, who were diagnosed from 2002 to 2007 with kidney tumors smaller than 1.5 cm.

Disclosures: Dr. Huang said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

CDC: Multiple cases link synthetic cannabinoid, kidney injury

Sixteen cases of acute kidney injury following the use of synthetic cannabinoids were identified in the United States in 2012, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The cases, which occurred in six states and were unrelated in all but two incidents, underscore the importance of awareness on the part of health care providers about renal and other unexpected toxicities from the use of synthetic cannabinoid (SC) compounds, the CDC said in the Feb. 15 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

This is particularly true given the increasing use of SCs, also known as synthetic marijuana, "spice," or "K2, and in light of prior reports of toxicities associated with SC.

The initial four cases of acute kidney injury (AKI) following recent SC use were reported in Wyoming in March 2012, and an additional 12 cases were subsequently identified, including 6 in Oregon, 2 in New York, 2 in Oklahoma, and 1 each in Rhode Island and Kansas (MMWR 2013;62:93-8).

The patients – 15 adolescent or adult males aged 15-33 years, and one 15-year-old female – all visited emergency departments complaining of nausea and vomiting within days or hours of SC use; 12 also reported abdominal, flank, and/or back pain, and none had preexisting renal dysfunction or used medications associated with renal problems. All were hospitalized.

"The highest serum creatinine concentrations (creatinine peak) among the 16 patients ranged from 3.3 to 21.0 mg/dL (median: 6.7 mg/dL; normal 0.6-1.3 mg/dL) and occurred 1-6 days after symptom onset (median: 3 days)," according to the report.

Urinalysis results were variable, demonstrating proteinuria in eight patients, casts in five patients, white blood cells in nine patients, and red blood cells in eight patients. Renal ultrasonography in 12 patients showed that 9 had a nonspecific increase in renal cortical echogenicity. None had hydronephrosis.

Renal biopsy in eight patients demonstrated acute tubular injury in six cases, and features of acute interstitial nephritis in three.

Most patients experienced kidney function recovery within 3 days of creatinine peak, but five required hemodialysis, and four received corticosteroids.

Toxicologic analysis of the implicated SC product and clinical specimens were possible in seven cases, and two products were linked with the first three cases. These products contained 3-(1-naphthoyl) indole, a precursor to several aminoalkylindole synthetic cannabinoids, and one also contained AM 2201, a potent SC previously linked to human disease and death, but not to AKI.

With one exception, other product samples and/or blood or urine specimens from patients contained XLR-11 (a previously undescribed fluorinated-derivative of the known SC compound UR-144) either alone or in combination with an N-pentanoic acid metabolite of XLR-11 or UR-144.

These reports of AKI following SC use are concerning given the worldwide distribution of SC products, which are "packaged in colorful wrappers designed to appeal to teens, young adults, and first-time drug users," according to an editorial note in the report, which also states that SCs often are packaged with disingenuous labels claiming the products are not for human consumption, although it is widely known that they are smoked like marijuana.

Despite federal and state regulations prohibiting SC sale and distribution, illicit use continues, and reports of illness are increasing.

"The increasing use of synthetic cannabinoids in adolescents is particularly concerning because these substances can contain multiple active and inactive substances with a variety of short-term and potentially unknown long-term effects," Dr. Joanna S. Cohen said in an interview.

In a case study published last year, Dr. Cohen, of the departments of pediatrics and emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, noted the increasing use of SCs among adolescents, the potential dangers of SCs with respect to the developing brain, and the need for providers to become familiar with the presenting signs and symptoms of SC-related intoxication (Pediatrics 2012;129:e1064-7).

According to the MMWR report, SCs are related to the active ingredient in marijuana (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol), but are up to three times more likely to be associated with sympathomimetic effects such as tachycardia and hypertension, and about five times more likely to be associated with hallucinations.

An increase in seizure occurrence also has been reported with SC use.

"Given the rapidity with which new SC compounds enter the marketplace and their increasing use in the past 3 years, outbreaks of unexpected toxicity associated with their use are likely to increase," the CDC said.