User login

Danish study finds increased glioma risk in a rosacea population

An increased focus on neurologic symptoms in patients with rosacea may be warranted, according to Danish researchers, who found a significantly increased risk of glioma associated with rosacea, in a nationwide study of Danish citizens.

The observational study followed 5,484,910 Danish adults from January 1997 through December 2011; 68,372 were diagnosed with rosacea, and the remaining 5,416,538 were the reference group. The incidence rate of glioma per 10,000 person-years (adjusted for age, sex, and socioeconomic status) was 3.34 in the reference population, but was 4.99 among those with rosacea, reported Dr. Alexander Egeberg of the department of dermatoallergology, Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Hellerup, and his coauthors (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5549).

The adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) of glioma in patients with rosacea was 1.36 (P less than .001). When the researchers limited the analysis to patients who had been diagnosed by a hospital dermatologist, the adjusted IRR was 1.82. The results remained significant after sensitivity analyses and after adjustment for potential confounders.

Among the patients with rosacea, men had an increased risk of glioma, compared with women (an incidence rate per 10,000 person-years of 6.45 vs. 4.30), although “gliomas and rosacea were generally more common among women,” the authors reported.

The association might be partially mediated by mechanisms dependent on matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), the authors said, referring to studies indicating that MMPs, in particular MMP-9, “play a pivotal role in rosacea and regulation of the invasiveness of malignant glioma cells.” While speculative, “mechanisms dependent on MMPs may contribute to the link between rosacea and the risk for glioma,” the investigators added.

An increased focus on neurologic symptoms such as headaches, memory loss, visual symptoms, cognitive decline, and personality changes in patients with rosacea “and timely referral to relevant specialists may be warranted,” they concluded.

Limitations of the study included the observational design, which cannot establish causation, the authors noted. Dr. Egeberg reported being a former employee of Pfizer; one coauthor reported receiving consultancy and/or speaker honoraria from Galderma. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the LEO Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation and an unrestricted research scholarship from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

An increased focus on neurologic symptoms in patients with rosacea may be warranted, according to Danish researchers, who found a significantly increased risk of glioma associated with rosacea, in a nationwide study of Danish citizens.

The observational study followed 5,484,910 Danish adults from January 1997 through December 2011; 68,372 were diagnosed with rosacea, and the remaining 5,416,538 were the reference group. The incidence rate of glioma per 10,000 person-years (adjusted for age, sex, and socioeconomic status) was 3.34 in the reference population, but was 4.99 among those with rosacea, reported Dr. Alexander Egeberg of the department of dermatoallergology, Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Hellerup, and his coauthors (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5549).

The adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) of glioma in patients with rosacea was 1.36 (P less than .001). When the researchers limited the analysis to patients who had been diagnosed by a hospital dermatologist, the adjusted IRR was 1.82. The results remained significant after sensitivity analyses and after adjustment for potential confounders.

Among the patients with rosacea, men had an increased risk of glioma, compared with women (an incidence rate per 10,000 person-years of 6.45 vs. 4.30), although “gliomas and rosacea were generally more common among women,” the authors reported.

The association might be partially mediated by mechanisms dependent on matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), the authors said, referring to studies indicating that MMPs, in particular MMP-9, “play a pivotal role in rosacea and regulation of the invasiveness of malignant glioma cells.” While speculative, “mechanisms dependent on MMPs may contribute to the link between rosacea and the risk for glioma,” the investigators added.

An increased focus on neurologic symptoms such as headaches, memory loss, visual symptoms, cognitive decline, and personality changes in patients with rosacea “and timely referral to relevant specialists may be warranted,” they concluded.

Limitations of the study included the observational design, which cannot establish causation, the authors noted. Dr. Egeberg reported being a former employee of Pfizer; one coauthor reported receiving consultancy and/or speaker honoraria from Galderma. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the LEO Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation and an unrestricted research scholarship from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

An increased focus on neurologic symptoms in patients with rosacea may be warranted, according to Danish researchers, who found a significantly increased risk of glioma associated with rosacea, in a nationwide study of Danish citizens.

The observational study followed 5,484,910 Danish adults from January 1997 through December 2011; 68,372 were diagnosed with rosacea, and the remaining 5,416,538 were the reference group. The incidence rate of glioma per 10,000 person-years (adjusted for age, sex, and socioeconomic status) was 3.34 in the reference population, but was 4.99 among those with rosacea, reported Dr. Alexander Egeberg of the department of dermatoallergology, Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Hellerup, and his coauthors (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan 27. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5549).

The adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) of glioma in patients with rosacea was 1.36 (P less than .001). When the researchers limited the analysis to patients who had been diagnosed by a hospital dermatologist, the adjusted IRR was 1.82. The results remained significant after sensitivity analyses and after adjustment for potential confounders.

Among the patients with rosacea, men had an increased risk of glioma, compared with women (an incidence rate per 10,000 person-years of 6.45 vs. 4.30), although “gliomas and rosacea were generally more common among women,” the authors reported.

The association might be partially mediated by mechanisms dependent on matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), the authors said, referring to studies indicating that MMPs, in particular MMP-9, “play a pivotal role in rosacea and regulation of the invasiveness of malignant glioma cells.” While speculative, “mechanisms dependent on MMPs may contribute to the link between rosacea and the risk for glioma,” the investigators added.

An increased focus on neurologic symptoms such as headaches, memory loss, visual symptoms, cognitive decline, and personality changes in patients with rosacea “and timely referral to relevant specialists may be warranted,” they concluded.

Limitations of the study included the observational design, which cannot establish causation, the authors noted. Dr. Egeberg reported being a former employee of Pfizer; one coauthor reported receiving consultancy and/or speaker honoraria from Galderma. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the LEO Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation and an unrestricted research scholarship from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Clinicians should be mindful of neurologic symptoms in patients with rosacea because of a significant association between glioma and rosacea.

Major finding: The incidence rate ratio of glioma per 10,000 person-years was 3.34 in the reference population and 4.99 in patients with rosacea.

Data source: A nationwide cohort study that followed 5,484 910 Danish adults from 1997 through 2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Egeberg reported being a former employee of Pfizer; one coauthor reported receiving consultancy and/or speaker honoraria from Galderma. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the LEO Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation and an unrestricted research scholarship from the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Proton radiotherapy effective for childhood medulloblastoma

Treatment of childhood medulloblastoma with proton radiotherapy resulted in acceptable toxicity, with no observed cardiac, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal late effects, and achieved outcomes that were similar to those of photon (x-ray)-based therapy.

At a median follow up of 5 years, the cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 hearing loss was 16% (95% confidence interval, 6-29). The Full Scale Intelligence Quotient decreased significantly, particularly in children younger than 8 years, driven mostly by drops in processing speed and verbal comprehension. The cumulative incidence of any hormone deficit at 7 years was 63% (95% CI, 48-75).

For all patients, progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years was 80% (95% CI, 67-88) and overall survival (OS) was 83% (95% CI, 70-90). For patients with standard-risk disease, PFS was 85% (95% CI, 69-93) and OS was 86% (95% CI, 70-94); for intermediate-risk disease, PFS was 67% (95% CI, 19-90) and OS was 67% (95% CI, 19-90); for high-risk disease, PFS was 71% (95% CI, 41-88) and OS was 79% (95% CI, 47-93). These rates are similar to previously published outcomes of 81%-83% for PFS and 85%-86% for OS (Lancet Onc. 2016 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00167-9).

“Therefore, the similar disease control coupled with similar patterns of failure should quell concerns raised about the differences in relative biologic effectiveness of passively scattered proton radiotherapy,” wrote Dr. Torunn Yock, chief of pediatric radiation oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

“Although there remain some effects of treatment on hearing, endocrine, and neurocognitive outcomes – particularly in younger patients – other late effects common in photon-treated patients, such as cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal toxic effects, were absent,” they said.

Medulloblastoma survivors often have treatment-related adverse late effects, and proton radiotherapy is used to mitigate late effects by decreasing the volume of normal tissue irradiated.

The estimated mean loss per year of IQ points, at –1.5, was less than IQ differences reported in previous studies, which ranged from –1.9 to –5.8 depending on age, craniospinal irradiation dosing, boost volumes, and length of follow-up.

There were no observed cardiac effects, and no patients had restrictive lung disease, which can occur in 24%-50% of long-term survivors treated with craniospinal photon irradiation. In addition, there were no new cases of gastrointestinal toxic effects that have occurred in up to 44% of photon-treated patients.

The prospective, nonrandomized phase II study carried out at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, evaluated 59 patients aged 3-21 years (median age 6.6 years) who had medulloblastoma (39 standard risk, 6 intermediate risk, and 14 high risk). All patients received chemotherapy and 55 had a near or gross total resection.

The prospective study by Dr. Yock and colleagues sets a new benchmark for treatment of medulloblastoma in pediatric patients and alludes to the clinical benefits of advanced radiation treatment. It becomes increasingly important for radiation oncologists to incorporate new findings in genomics and molecular subtyping for diseases such as medulloblastoma in the design of prospective studies, and to implement strategies to prevent cognitive decline in pediatric patients. The investigators demonstrate benefits of low-dose sparing afforded by proton therapy, but further improvements are possible. With newer delivery techniques, such as spot scanning proton therapy for the craniospinal component of treatment, more improvements in hearing outcomes can be expected.

The rarity of the disease, combined with the compelling results of Dr. Yock and colleagues, make randomized trials of photons versus protons for medulloblastoma unlikely. Without randomized trial data, some states require that all pediatric patients be treated with photon therapy, a requirement that could result higher rates of cardiovascular disease and other adverse effects. Radiation oncologists understand the potential for severe adverse effects of treatment, and many embrace new technologies that mitigate effects of radiation therapy on patients’ quality of life, a consideration that is particularly important in treatment of pediatric cancers.

Dr. David Grosshans is at the department of radiation oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report by Dr. Yock and colleagues (Lancet Onc. 2016 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00217-X. Dr. Grosshans reported having no disclosures.

The prospective study by Dr. Yock and colleagues sets a new benchmark for treatment of medulloblastoma in pediatric patients and alludes to the clinical benefits of advanced radiation treatment. It becomes increasingly important for radiation oncologists to incorporate new findings in genomics and molecular subtyping for diseases such as medulloblastoma in the design of prospective studies, and to implement strategies to prevent cognitive decline in pediatric patients. The investigators demonstrate benefits of low-dose sparing afforded by proton therapy, but further improvements are possible. With newer delivery techniques, such as spot scanning proton therapy for the craniospinal component of treatment, more improvements in hearing outcomes can be expected.

The rarity of the disease, combined with the compelling results of Dr. Yock and colleagues, make randomized trials of photons versus protons for medulloblastoma unlikely. Without randomized trial data, some states require that all pediatric patients be treated with photon therapy, a requirement that could result higher rates of cardiovascular disease and other adverse effects. Radiation oncologists understand the potential for severe adverse effects of treatment, and many embrace new technologies that mitigate effects of radiation therapy on patients’ quality of life, a consideration that is particularly important in treatment of pediatric cancers.

Dr. David Grosshans is at the department of radiation oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report by Dr. Yock and colleagues (Lancet Onc. 2016 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00217-X. Dr. Grosshans reported having no disclosures.

The prospective study by Dr. Yock and colleagues sets a new benchmark for treatment of medulloblastoma in pediatric patients and alludes to the clinical benefits of advanced radiation treatment. It becomes increasingly important for radiation oncologists to incorporate new findings in genomics and molecular subtyping for diseases such as medulloblastoma in the design of prospective studies, and to implement strategies to prevent cognitive decline in pediatric patients. The investigators demonstrate benefits of low-dose sparing afforded by proton therapy, but further improvements are possible. With newer delivery techniques, such as spot scanning proton therapy for the craniospinal component of treatment, more improvements in hearing outcomes can be expected.

The rarity of the disease, combined with the compelling results of Dr. Yock and colleagues, make randomized trials of photons versus protons for medulloblastoma unlikely. Without randomized trial data, some states require that all pediatric patients be treated with photon therapy, a requirement that could result higher rates of cardiovascular disease and other adverse effects. Radiation oncologists understand the potential for severe adverse effects of treatment, and many embrace new technologies that mitigate effects of radiation therapy on patients’ quality of life, a consideration that is particularly important in treatment of pediatric cancers.

Dr. David Grosshans is at the department of radiation oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. These remarks were part of an editorial accompanying the report by Dr. Yock and colleagues (Lancet Onc. 2016 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00217-X. Dr. Grosshans reported having no disclosures.

Treatment of childhood medulloblastoma with proton radiotherapy resulted in acceptable toxicity, with no observed cardiac, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal late effects, and achieved outcomes that were similar to those of photon (x-ray)-based therapy.

At a median follow up of 5 years, the cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 hearing loss was 16% (95% confidence interval, 6-29). The Full Scale Intelligence Quotient decreased significantly, particularly in children younger than 8 years, driven mostly by drops in processing speed and verbal comprehension. The cumulative incidence of any hormone deficit at 7 years was 63% (95% CI, 48-75).

For all patients, progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years was 80% (95% CI, 67-88) and overall survival (OS) was 83% (95% CI, 70-90). For patients with standard-risk disease, PFS was 85% (95% CI, 69-93) and OS was 86% (95% CI, 70-94); for intermediate-risk disease, PFS was 67% (95% CI, 19-90) and OS was 67% (95% CI, 19-90); for high-risk disease, PFS was 71% (95% CI, 41-88) and OS was 79% (95% CI, 47-93). These rates are similar to previously published outcomes of 81%-83% for PFS and 85%-86% for OS (Lancet Onc. 2016 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00167-9).

“Therefore, the similar disease control coupled with similar patterns of failure should quell concerns raised about the differences in relative biologic effectiveness of passively scattered proton radiotherapy,” wrote Dr. Torunn Yock, chief of pediatric radiation oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

“Although there remain some effects of treatment on hearing, endocrine, and neurocognitive outcomes – particularly in younger patients – other late effects common in photon-treated patients, such as cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal toxic effects, were absent,” they said.

Medulloblastoma survivors often have treatment-related adverse late effects, and proton radiotherapy is used to mitigate late effects by decreasing the volume of normal tissue irradiated.

The estimated mean loss per year of IQ points, at –1.5, was less than IQ differences reported in previous studies, which ranged from –1.9 to –5.8 depending on age, craniospinal irradiation dosing, boost volumes, and length of follow-up.

There were no observed cardiac effects, and no patients had restrictive lung disease, which can occur in 24%-50% of long-term survivors treated with craniospinal photon irradiation. In addition, there were no new cases of gastrointestinal toxic effects that have occurred in up to 44% of photon-treated patients.

The prospective, nonrandomized phase II study carried out at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, evaluated 59 patients aged 3-21 years (median age 6.6 years) who had medulloblastoma (39 standard risk, 6 intermediate risk, and 14 high risk). All patients received chemotherapy and 55 had a near or gross total resection.

Treatment of childhood medulloblastoma with proton radiotherapy resulted in acceptable toxicity, with no observed cardiac, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal late effects, and achieved outcomes that were similar to those of photon (x-ray)-based therapy.

At a median follow up of 5 years, the cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 hearing loss was 16% (95% confidence interval, 6-29). The Full Scale Intelligence Quotient decreased significantly, particularly in children younger than 8 years, driven mostly by drops in processing speed and verbal comprehension. The cumulative incidence of any hormone deficit at 7 years was 63% (95% CI, 48-75).

For all patients, progression-free survival (PFS) at 5 years was 80% (95% CI, 67-88) and overall survival (OS) was 83% (95% CI, 70-90). For patients with standard-risk disease, PFS was 85% (95% CI, 69-93) and OS was 86% (95% CI, 70-94); for intermediate-risk disease, PFS was 67% (95% CI, 19-90) and OS was 67% (95% CI, 19-90); for high-risk disease, PFS was 71% (95% CI, 41-88) and OS was 79% (95% CI, 47-93). These rates are similar to previously published outcomes of 81%-83% for PFS and 85%-86% for OS (Lancet Onc. 2016 Jan 29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00167-9).

“Therefore, the similar disease control coupled with similar patterns of failure should quell concerns raised about the differences in relative biologic effectiveness of passively scattered proton radiotherapy,” wrote Dr. Torunn Yock, chief of pediatric radiation oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

“Although there remain some effects of treatment on hearing, endocrine, and neurocognitive outcomes – particularly in younger patients – other late effects common in photon-treated patients, such as cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal toxic effects, were absent,” they said.

Medulloblastoma survivors often have treatment-related adverse late effects, and proton radiotherapy is used to mitigate late effects by decreasing the volume of normal tissue irradiated.

The estimated mean loss per year of IQ points, at –1.5, was less than IQ differences reported in previous studies, which ranged from –1.9 to –5.8 depending on age, craniospinal irradiation dosing, boost volumes, and length of follow-up.

There were no observed cardiac effects, and no patients had restrictive lung disease, which can occur in 24%-50% of long-term survivors treated with craniospinal photon irradiation. In addition, there were no new cases of gastrointestinal toxic effects that have occurred in up to 44% of photon-treated patients.

The prospective, nonrandomized phase II study carried out at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, evaluated 59 patients aged 3-21 years (median age 6.6 years) who had medulloblastoma (39 standard risk, 6 intermediate risk, and 14 high risk). All patients received chemotherapy and 55 had a near or gross total resection.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Proton radiotherapy for childhood medulloblastoma resulted in similar survival outcomes to those of photon-based therapy and had acceptable toxicity.

Major finding: At 5 years, the cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 hearing loss was 16%; 5-year progression-free and overall survival for patients with standard risk were 85% and 86%, respectively, and for those with high to intermediate risk, 70% and 75%, respectively.

Data source: A prospective, nonrandomized, phase II study with 59 patients aged 3-21 years who had medulloblastoma (39 standard risk, 6 intermediate risk, and 14 high risk).

Disclosures: Dr. Yock and coauthors reported having no disclosures.

Neurosurgeon memoir illuminates the journey through cancer treatment and acceptance of mortality

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

Dr. Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon who had just completed his residency at the Stanford (Calif.) University, died of metastatic lung cancer last year, but he left a memoir of his experiences as a physician, a patient, and a dying man that was published on Jan. 12. His book, “When Breath Becomes Air” (New York: Random House, 2016), recounts the many years of working to exhaustion and deferring of life experiences and pleasures that are necessary to complete medical training.

In a review of the book, Janet Maslin wrote, “One of the most poignant things about Dr. Kalanithi’s story is that he had postponed learning how to live while pursuing his career in neurosurgery. By the time he was ready to enjoy a life outside the operating room, what he needed to learn was how to die.”

Dr. Kalanithi reflected on the profound grief and sense of loss that comes with a diagnosis that he knew meant imminent death. The memoir also reveals his search for meaning and joy, and finally, his acceptance of mortality. He opted for palliative care and his memoir, along with the epilogue written by his wife, Dr. Lucy Kalanithi, gives insight into the value of the palliative path to patients and their families in dire medical crises.

David Bowie’s death inspires blog on palliative care

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

The death of David Bowie, iconic musician and artist, on Jan. 10 inspired palliative care specialist Dr. Mark Taubert to write a blog about end-of-life scenarios and the importance of advance care planning. The blog, which begins by thanking Mr. Bowie for his many artistic contributions, continues by suggesting that his planned death at home will inspire many people in similar health crises to consider palliative care. The palliative care conversation between a doctor and a patient facing death can be challenging but can lead to what Dr. Taubert called “a good death” at home with symptoms managed and loved ones nearby. Mr. Bowie’s son, Duncan Jones, tweeted a link to the blog in the days after his father’s death.

Dr. Taubert found himself speaking with a patient who was facing probable death in the near future, and both doctor and patient found inspiration in Mr. Bowie’s final music project and his death at home with his family. Dr. Taubert and his patient were able to have the conversation about palliative care at end-of-life in part because they were both impressed with what Mr. Bowie was able to achieve in his last months. “Your story became a way for us to communicate very openly about death, something many doctors and nurses struggle to introduce as a topic of conversation,” he wrote.

Dr. Taubert of the Velindre NHS Trust in Cardiff, Wales, noted that, although palliative care is a highly developed skill with many resources to help patients at the end of life, “this essential part of training is not always available for junior healthcare professionals, including doctors and nurses, and is sometimes overlooked or under-prioritized by those who plan their education. I think if you [David Bowie] were ever to return (as Lazarus did), you would be a firm advocate for good palliative care training being available everywhere.”

Families perceive few benefits from aggressive end-of-life care

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Bereaved families were substantially more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients did not die in hospital, received more than 3 days of hospice care, and did not enter the ICU within 30 days of dying, according to a multicenter, prospective study published online Jan. 19 in JAMA.

The analysis is one of the first of its type to assess these end-of-life care indicators, said Dr. Alexi Wright of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates. The findings could affect health policy as electronic health records expand under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, they said.

End-of-life cancer care has become increasingly aggressive, belying evidence that this approach does not improve patient outcomes, quality of life, or caregiver bereavement. To explore alternatives, the researchers analyzed 1,146 interviews of family members of Medicare patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer by 2011. Their data source was the multiregional, prospective, observational Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (JAMA 2016;315:284-92).

Family members described end-of-life care as “excellent” 59% of the time when hospice care lasted more 3 days, but 43% of the time otherwise (95% confidence interval for adjusted difference, 11% to 22%). Notably, 73% of patients who received more than 3 days of hospice care died in their preferred location, compared with 40% of patients who received less or no hospice care. Care was rated as excellent 52% of the time when ICU admission was avoided within 30 days of death, and 57% of the time when patients died outside the hospital, compared with 45% and 42% of the time otherwise.

The results support “advance care planning consistent with the preferences of patients,” said the investigators. They recommended more extensive counseling of cancer patients and families, earlier palliative care referrals, and an audit and feedback system to monitor the use of aggressive end-of-life care.

The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the study. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum, also of Harvard Medical School, reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Bereaved family members were more satisfied with end-of-life cancer care when patients spent more than 3 days in hospice, died outside the hospital, and were not admitted to the ICU within 30 days of dying.

Major finding: Care was described as “excellent” about 9%-17% more often when these end-of-life quality indicators were met.

Data source: A multicenter, prospective, observational study of 1,146 family members of patients who died of lung or colorectal cancer.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium funded the analysis. One coinvestigator reported financial relationships with the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institute on Aging, Retirement Research Retirement Foundation, California Healthcare Foundation, Commonwealth Fund, West Health Institute, University of Wisconsin, and UpToDate.com. Senior author Dr. Mary Landrum reported grant funding from Pfizer and personal fees from McKinsey and Company and Greylock McKinnon Associates. The other authors had no disclosures.

Neurosurgery at the End of Life

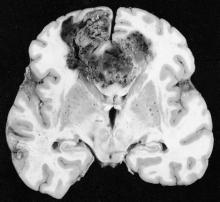

The juxtaposition between my first 2 days of neurosurgery could not have been more profound. On my first day as a third-year medical student, the attending and chief resident let me take the lead on the first case: a straightforward brain biopsy. I got to make the incision, drill the burr hole, and perform the needle biopsy. I still remember the thrill of the technical challenge, the controlled violence of drilling into the skull, and the finesse of accessing the tumor core.

The buzz was so strong that I barely registered the diagnosis that was called back from the pathologist: glioblastoma. It was not until I saw the face of the disease the next morning that I understood the reality of a GBM diagnosis. That face belonged to a 47-year-old man who hadn’t slept all night, wide eyed with apprehension at what news I might bring. He beseeched me with questions, and though his aphasia left him stammering to get the words out, I knew exactly what he was asking: Would he live or die? It was a question I was in no position to answer. Instead, I reassured him that we were waiting on the final pathology, all the while trying to forget the fact that the frozen section suggested an aggressive subtype, surely heralding a poor prognosis.

In his poignant memoir, “Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery” (New York: Thomas Dunne Book, 2015), Dr. Henry Marsh writes beautifully about how difficult it can be to find the balance between optimism and realism. In one memorable passage, Dr. Marsh shows a house officer a scan of a highly malignant brain tumor and asks him what he would say to the patient. The trainee reflexively hides behind jargon, skirting around what he knew to be the truth: This tumor would kill her. Marsh presses him to admit that he’s lying, before lamenting at how hard it is to improve these critical communication skills: “When I have had to break bad news I never know whether I have done it well or not. The patients aren’t going to ring me up afterward and say, ‘Mr. Marsh, I really liked the way you told me that I was going to die,’ or ‘Mr. Marsh, you were crap.’ You can only hope that you haven’t made too much of a mess of it.”

I could certainly relate to Dr. Marsh’s house officer as I walked away from my own patient. I felt almost deceitful withholding diagnostic information from him, even if I did the “right” thing. It made me wonder, why did I want to become a neurosurgeon? Surely to help people through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. But is it possible to be a source of comfort when you are required so often to be a harbinger of death? The answer depends on whether one can envision a role for the neurosurgeon beyond the mandate of “life at all costs.”

While the field has become known for its life-saving procedures, neurosurgeons are called just as often to preside over the end of their patient’s lives – work that requires just as much skill as any technical procedure. Dr. Marsh recognized the tremendous human cost of neglecting that work. For cases that appear “hopeless,” he writes, “We often end up operating because it’s easier than being honest, and it means that we can avoid a painful conversation.”

We are only beginning to understand the many issues that neurosurgical patients face at the end of life, but so far it is clear that neurosurgical trainees require substantive training in prognostication, communication, and palliation (Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43[9]:1964-77 1,2; J Neurooncol. 2009 Jan;91[1]:39-43). Is there room in the current training paradigm for more formal education in these domains? As we move further into the 21st century, we must embrace the need for masterful clinicians outside of the operating room if we are to ever challenge the axiom set forth by the renowned French surgeon, René Leriche, some 65 years ago: “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Let us look forward to the day when this is no longer the case.

Stephen Miranda is a medical student from the University of Rochester, who is now working as a research fellow at Ariadne Labs, a joint center for health systems innovation at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston.

The juxtaposition between my first 2 days of neurosurgery could not have been more profound. On my first day as a third-year medical student, the attending and chief resident let me take the lead on the first case: a straightforward brain biopsy. I got to make the incision, drill the burr hole, and perform the needle biopsy. I still remember the thrill of the technical challenge, the controlled violence of drilling into the skull, and the finesse of accessing the tumor core.

The buzz was so strong that I barely registered the diagnosis that was called back from the pathologist: glioblastoma. It was not until I saw the face of the disease the next morning that I understood the reality of a GBM diagnosis. That face belonged to a 47-year-old man who hadn’t slept all night, wide eyed with apprehension at what news I might bring. He beseeched me with questions, and though his aphasia left him stammering to get the words out, I knew exactly what he was asking: Would he live or die? It was a question I was in no position to answer. Instead, I reassured him that we were waiting on the final pathology, all the while trying to forget the fact that the frozen section suggested an aggressive subtype, surely heralding a poor prognosis.

In his poignant memoir, “Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery” (New York: Thomas Dunne Book, 2015), Dr. Henry Marsh writes beautifully about how difficult it can be to find the balance between optimism and realism. In one memorable passage, Dr. Marsh shows a house officer a scan of a highly malignant brain tumor and asks him what he would say to the patient. The trainee reflexively hides behind jargon, skirting around what he knew to be the truth: This tumor would kill her. Marsh presses him to admit that he’s lying, before lamenting at how hard it is to improve these critical communication skills: “When I have had to break bad news I never know whether I have done it well or not. The patients aren’t going to ring me up afterward and say, ‘Mr. Marsh, I really liked the way you told me that I was going to die,’ or ‘Mr. Marsh, you were crap.’ You can only hope that you haven’t made too much of a mess of it.”

I could certainly relate to Dr. Marsh’s house officer as I walked away from my own patient. I felt almost deceitful withholding diagnostic information from him, even if I did the “right” thing. It made me wonder, why did I want to become a neurosurgeon? Surely to help people through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. But is it possible to be a source of comfort when you are required so often to be a harbinger of death? The answer depends on whether one can envision a role for the neurosurgeon beyond the mandate of “life at all costs.”

While the field has become known for its life-saving procedures, neurosurgeons are called just as often to preside over the end of their patient’s lives – work that requires just as much skill as any technical procedure. Dr. Marsh recognized the tremendous human cost of neglecting that work. For cases that appear “hopeless,” he writes, “We often end up operating because it’s easier than being honest, and it means that we can avoid a painful conversation.”

We are only beginning to understand the many issues that neurosurgical patients face at the end of life, but so far it is clear that neurosurgical trainees require substantive training in prognostication, communication, and palliation (Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43[9]:1964-77 1,2; J Neurooncol. 2009 Jan;91[1]:39-43). Is there room in the current training paradigm for more formal education in these domains? As we move further into the 21st century, we must embrace the need for masterful clinicians outside of the operating room if we are to ever challenge the axiom set forth by the renowned French surgeon, René Leriche, some 65 years ago: “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Let us look forward to the day when this is no longer the case.

Stephen Miranda is a medical student from the University of Rochester, who is now working as a research fellow at Ariadne Labs, a joint center for health systems innovation at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston.

The juxtaposition between my first 2 days of neurosurgery could not have been more profound. On my first day as a third-year medical student, the attending and chief resident let me take the lead on the first case: a straightforward brain biopsy. I got to make the incision, drill the burr hole, and perform the needle biopsy. I still remember the thrill of the technical challenge, the controlled violence of drilling into the skull, and the finesse of accessing the tumor core.

The buzz was so strong that I barely registered the diagnosis that was called back from the pathologist: glioblastoma. It was not until I saw the face of the disease the next morning that I understood the reality of a GBM diagnosis. That face belonged to a 47-year-old man who hadn’t slept all night, wide eyed with apprehension at what news I might bring. He beseeched me with questions, and though his aphasia left him stammering to get the words out, I knew exactly what he was asking: Would he live or die? It was a question I was in no position to answer. Instead, I reassured him that we were waiting on the final pathology, all the while trying to forget the fact that the frozen section suggested an aggressive subtype, surely heralding a poor prognosis.

In his poignant memoir, “Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death and Brain Surgery” (New York: Thomas Dunne Book, 2015), Dr. Henry Marsh writes beautifully about how difficult it can be to find the balance between optimism and realism. In one memorable passage, Dr. Marsh shows a house officer a scan of a highly malignant brain tumor and asks him what he would say to the patient. The trainee reflexively hides behind jargon, skirting around what he knew to be the truth: This tumor would kill her. Marsh presses him to admit that he’s lying, before lamenting at how hard it is to improve these critical communication skills: “When I have had to break bad news I never know whether I have done it well or not. The patients aren’t going to ring me up afterward and say, ‘Mr. Marsh, I really liked the way you told me that I was going to die,’ or ‘Mr. Marsh, you were crap.’ You can only hope that you haven’t made too much of a mess of it.”

I could certainly relate to Dr. Marsh’s house officer as I walked away from my own patient. I felt almost deceitful withholding diagnostic information from him, even if I did the “right” thing. It made me wonder, why did I want to become a neurosurgeon? Surely to help people through some of the most difficult moments of their lives. But is it possible to be a source of comfort when you are required so often to be a harbinger of death? The answer depends on whether one can envision a role for the neurosurgeon beyond the mandate of “life at all costs.”

While the field has become known for its life-saving procedures, neurosurgeons are called just as often to preside over the end of their patient’s lives – work that requires just as much skill as any technical procedure. Dr. Marsh recognized the tremendous human cost of neglecting that work. For cases that appear “hopeless,” he writes, “We often end up operating because it’s easier than being honest, and it means that we can avoid a painful conversation.”

We are only beginning to understand the many issues that neurosurgical patients face at the end of life, but so far it is clear that neurosurgical trainees require substantive training in prognostication, communication, and palliation (Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43[9]:1964-77 1,2; J Neurooncol. 2009 Jan;91[1]:39-43). Is there room in the current training paradigm for more formal education in these domains? As we move further into the 21st century, we must embrace the need for masterful clinicians outside of the operating room if we are to ever challenge the axiom set forth by the renowned French surgeon, René Leriche, some 65 years ago: “Every surgeon carries within himself a small cemetery, where from time to time he goes to pray – a place of bitterness and regret, where he must look for an explanation for his failures.” Let us look forward to the day when this is no longer the case.

Stephen Miranda is a medical student from the University of Rochester, who is now working as a research fellow at Ariadne Labs, a joint center for health systems innovation at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston.

The palliative path: Talking with elderly patients facing emergency surgery

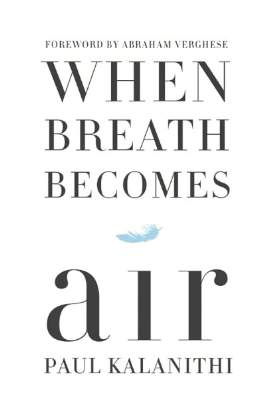

An expert panel has developed a communication framework to improve treatment of older, seriously ill patients who have surgical emergencies, which has been published online in Annals of Surgery.

A substantial portion of older patients who undergo emergency surgeries already have serious life-limiting illnesses such as cardiopulmonary disease, renal failure, liver failure, dementia, severe neurological impairment, or malignancy. The advisory panel based its work on the premise that surgery in these circumstances can lead to significant further morbidity, health care utilization, functional decline, prolonged hospital stay or institutionalization, and death, with attendant physical discomfort and psychological distress at the end of these patients’ lives.

Surgeons consulted in the emergency setting for these patients are hampered by patients unable to communicate well because they are in extremis, by surrogates who are unprepared for their role, and by time constraints, lack of familiarity with the patient, poor understanding of the illness by patients and families, prognostic uncertainty, and inadequate advance care planning. In addition, “many surgeons lack skills to engage in conversations about end-of-life care, or are too unfamiliar with palliative options to discuss them well,” or feel obligated to maintain postoperative life support despite the patient’s wishes, said Dr. Zara Cooper, of Ariadne Labs and the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and her associates.

To address these issues and assist surgeons in caring for such patients, an expert panel of 23 national leaders in acute care surgery, general surgery, surgical oncology, palliative medicine, critical care, emergency medicine, anesthesia, and health care innovation was convened at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The focus of the panel’s recommendations was a structured communications framework prototype to facilitate shared decision-making in these difficult circumstances.

Among the panel’s recommendations for surgeons were the following priorities:

• Review the medical record and consult the treatment team to fully understand the patient’s current condition, comorbidities, expected illness trajectory, and preferences for end-of-life care.

• Assess functional performance as part of the routine history and physical to fully understand the patient’s fitness for surgery.

• Formulate a prognosis regarding the patient’s overall health both with and without surgery.

The panel offered a set of principles and specific elements for the meeting with the patient and family:

• The surgeon should begin by introducing himself or herself; according to reports in the literature, physicians fail to do this approximately half of the time.

• Pay attention to nonverbal communication, such as eye contact and physical contact, as this is critical to building rapport. Immediately address pain, anxiety, and other indicators of distress, to maximize the patients’ and the families’ engagement in subsequent medical discussions. “Although adequate analgesia may render a patient unable to make their own decisions, surrogates are more likely to make appropriate decisions when they feel their loved one is comfortable,” the panel noted.

• Allow pauses and silences to occur. Let the patient and the family process information and their own emotions.

• Elicit the patients’ or the surrogates’ understanding of the illness and their views of the patients’ likely trajectory, correcting any inaccuracies. This substantially influences their decisions regarding the aggressiveness of subsequent treatments.

• Inform the patient and family of the life-threatening nature of the patient’s acute condition and its potential impact on the rest of his or her life, including the possibility of prolonged life support, ICU stay, burdensome treatment, and loss of independence. Use accepted techniques for breaking bad news, and check to be sure the patient understands what was conveyed.

• At this point, the surgeon should synthesize and summarize the information from the patient, the family, and the medical record, then pause to give them time to process the information and to assess their emotional state. It is helpful to label and respond to the patient’s emotions at this juncture, and to build empathy with statements such as “I know this is difficult news, and I wish it were different.”

• Describe the benefits, burdens, and range of likely outcomes if surgery is undertaken and if it is not. The surgeon should use nonmedical language to describe symptoms, and should convey his or her expectations regarding length of hospitalization, need for and duration of life support, burdensome symptoms, discharge to an institution, and functional recovery.

• Surgeons should be able to communicate palliative options possible either in combination with surgery or instead of surgery. Palliative care can aid in managing advanced symptoms, providing psychosocial support for patients and caregivers, facilitating interdisciplinary communication, and facilitating medical decisions and care transitions.

• Avoid describing surgical procedures as “doing everything” and palliative care as “doing nothing.” This can make patients and families “feel abandoned, fearful, isolated, and angry, and fails to encompass palliative care’s practices of proactive communication, aggressive symptom management, and timely emotional support to alleviate suffering and affirm quality of life,” the panel said.

• Surgeons should explicitly support the patients’ medical decisions, whether or not they choose surgery.

The panel also cited a few factors that would assist surgeons in following these recommendations. First, surgeons must recognize the importance of communicating well with seriously ill older patients and acknowledge that this is a crucial clinical skill for them to cultivate. They must also recognize that palliative care is vital to delivering high-quality surgical care. Surgeons should consider discharging patients to hospice, which can improve pain and symptom management, improve patient and family satisfaction with care, and avoid unwanted hospitalization or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

“There are a number of major barriers to introducing palliative care in these situations. One is an education problem - the perception on the part of patients and clinicians, and surgeons in particular, that palliative care is only limited to end-of-life care, which it is not. It is a misperception of what palliative care means in this equation - that palliative care and hospice are the same thing, which they absolutely are not,”said Dr. Cooper in an interview.

”The definition of palliative care has evolved over the past decade and the focus of palliative care is on quality of life and alleviating symptoms. End-of-life palliative care is part of that, and as patients get closer to the end of life, symptom management and quality of life become more focal than life-prolonging treatment... But for patients with chronic and serious illness, there has to be a role for palliative care because we know that when patients feel better, they tend to live longer. And when patients feel their emotional concerns and physical needs are being addressed, they tend to do better. Patients families have improved satisfaction when their loved one receives palliative care,” she noted.”

However, the number of palliative providers is completely inadequate to meet the needs of the number of seriously ill patients, she said. And a lot of hospital-based palliative care is by necessity limited to end-of-life care because of a lack of palliative resources.

Dr. Atul Gawande, a coauthor of the panel recommendations, wrote a best-selling book, Being Mortal (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014) addressing the shortcomings and potential remaking of medical care in the context of age-related frailty, grave illness, and death. Dr. Cooper noted that there is a growing sentiment among the general public that they want to have their quality of life addressed in the type of medical care they receive. She said that Dr. Gawande’s book tapped into the perception of a lack of recognition of personhood of seriously ill patients.

“We often focus on diagnosis and we don’t have the ‘bandwidth’ to focus on the person carrying that diagnosis, and our patients and focus on the person carrying that diagnosis, but our patients and their families are demanding different types of care. So, ultimately, the patients will be the ones to push us to do better for them.”

The next steps to further developing a widely used and validated communication framework would be to create educational opportunities for clinicians to develop clinical skills in communication with seriously ill patients and palliative care, and to study the impact of these initiatives on improving outcomes most relevant to older patient. This work was supported by the Ariadne Labs, a Joint Center for Health System Innovation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Cooper and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

An expert panel has developed a communication framework to improve treatment of older, seriously ill patients who have surgical emergencies, which has been published online in Annals of Surgery.

A substantial portion of older patients who undergo emergency surgeries already have serious life-limiting illnesses such as cardiopulmonary disease, renal failure, liver failure, dementia, severe neurological impairment, or malignancy. The advisory panel based its work on the premise that surgery in these circumstances can lead to significant further morbidity, health care utilization, functional decline, prolonged hospital stay or institutionalization, and death, with attendant physical discomfort and psychological distress at the end of these patients’ lives.

Surgeons consulted in the emergency setting for these patients are hampered by patients unable to communicate well because they are in extremis, by surrogates who are unprepared for their role, and by time constraints, lack of familiarity with the patient, poor understanding of the illness by patients and families, prognostic uncertainty, and inadequate advance care planning. In addition, “many surgeons lack skills to engage in conversations about end-of-life care, or are too unfamiliar with palliative options to discuss them well,” or feel obligated to maintain postoperative life support despite the patient’s wishes, said Dr. Zara Cooper, of Ariadne Labs and the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and her associates.

To address these issues and assist surgeons in caring for such patients, an expert panel of 23 national leaders in acute care surgery, general surgery, surgical oncology, palliative medicine, critical care, emergency medicine, anesthesia, and health care innovation was convened at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The focus of the panel’s recommendations was a structured communications framework prototype to facilitate shared decision-making in these difficult circumstances.

Among the panel’s recommendations for surgeons were the following priorities:

• Review the medical record and consult the treatment team to fully understand the patient’s current condition, comorbidities, expected illness trajectory, and preferences for end-of-life care.

• Assess functional performance as part of the routine history and physical to fully understand the patient’s fitness for surgery.

• Formulate a prognosis regarding the patient’s overall health both with and without surgery.

The panel offered a set of principles and specific elements for the meeting with the patient and family:

• The surgeon should begin by introducing himself or herself; according to reports in the literature, physicians fail to do this approximately half of the time.

• Pay attention to nonverbal communication, such as eye contact and physical contact, as this is critical to building rapport. Immediately address pain, anxiety, and other indicators of distress, to maximize the patients’ and the families’ engagement in subsequent medical discussions. “Although adequate analgesia may render a patient unable to make their own decisions, surrogates are more likely to make appropriate decisions when they feel their loved one is comfortable,” the panel noted.

• Allow pauses and silences to occur. Let the patient and the family process information and their own emotions.

• Elicit the patients’ or the surrogates’ understanding of the illness and their views of the patients’ likely trajectory, correcting any inaccuracies. This substantially influences their decisions regarding the aggressiveness of subsequent treatments.

• Inform the patient and family of the life-threatening nature of the patient’s acute condition and its potential impact on the rest of his or her life, including the possibility of prolonged life support, ICU stay, burdensome treatment, and loss of independence. Use accepted techniques for breaking bad news, and check to be sure the patient understands what was conveyed.

• At this point, the surgeon should synthesize and summarize the information from the patient, the family, and the medical record, then pause to give them time to process the information and to assess their emotional state. It is helpful to label and respond to the patient’s emotions at this juncture, and to build empathy with statements such as “I know this is difficult news, and I wish it were different.”

• Describe the benefits, burdens, and range of likely outcomes if surgery is undertaken and if it is not. The surgeon should use nonmedical language to describe symptoms, and should convey his or her expectations regarding length of hospitalization, need for and duration of life support, burdensome symptoms, discharge to an institution, and functional recovery.

• Surgeons should be able to communicate palliative options possible either in combination with surgery or instead of surgery. Palliative care can aid in managing advanced symptoms, providing psychosocial support for patients and caregivers, facilitating interdisciplinary communication, and facilitating medical decisions and care transitions.

• Avoid describing surgical procedures as “doing everything” and palliative care as “doing nothing.” This can make patients and families “feel abandoned, fearful, isolated, and angry, and fails to encompass palliative care’s practices of proactive communication, aggressive symptom management, and timely emotional support to alleviate suffering and affirm quality of life,” the panel said.

• Surgeons should explicitly support the patients’ medical decisions, whether or not they choose surgery.

The panel also cited a few factors that would assist surgeons in following these recommendations. First, surgeons must recognize the importance of communicating well with seriously ill older patients and acknowledge that this is a crucial clinical skill for them to cultivate. They must also recognize that palliative care is vital to delivering high-quality surgical care. Surgeons should consider discharging patients to hospice, which can improve pain and symptom management, improve patient and family satisfaction with care, and avoid unwanted hospitalization or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

“There are a number of major barriers to introducing palliative care in these situations. One is an education problem - the perception on the part of patients and clinicians, and surgeons in particular, that palliative care is only limited to end-of-life care, which it is not. It is a misperception of what palliative care means in this equation - that palliative care and hospice are the same thing, which they absolutely are not,”said Dr. Cooper in an interview.

”The definition of palliative care has evolved over the past decade and the focus of palliative care is on quality of life and alleviating symptoms. End-of-life palliative care is part of that, and as patients get closer to the end of life, symptom management and quality of life become more focal than life-prolonging treatment... But for patients with chronic and serious illness, there has to be a role for palliative care because we know that when patients feel better, they tend to live longer. And when patients feel their emotional concerns and physical needs are being addressed, they tend to do better. Patients families have improved satisfaction when their loved one receives palliative care,” she noted.”

However, the number of palliative providers is completely inadequate to meet the needs of the number of seriously ill patients, she said. And a lot of hospital-based palliative care is by necessity limited to end-of-life care because of a lack of palliative resources.

Dr. Atul Gawande, a coauthor of the panel recommendations, wrote a best-selling book, Being Mortal (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014) addressing the shortcomings and potential remaking of medical care in the context of age-related frailty, grave illness, and death. Dr. Cooper noted that there is a growing sentiment among the general public that they want to have their quality of life addressed in the type of medical care they receive. She said that Dr. Gawande’s book tapped into the perception of a lack of recognition of personhood of seriously ill patients.

“We often focus on diagnosis and we don’t have the ‘bandwidth’ to focus on the person carrying that diagnosis, and our patients and focus on the person carrying that diagnosis, but our patients and their families are demanding different types of care. So, ultimately, the patients will be the ones to push us to do better for them.”

The next steps to further developing a widely used and validated communication framework would be to create educational opportunities for clinicians to develop clinical skills in communication with seriously ill patients and palliative care, and to study the impact of these initiatives on improving outcomes most relevant to older patient. This work was supported by the Ariadne Labs, a Joint Center for Health System Innovation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Cooper and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

An expert panel has developed a communication framework to improve treatment of older, seriously ill patients who have surgical emergencies, which has been published online in Annals of Surgery.

A substantial portion of older patients who undergo emergency surgeries already have serious life-limiting illnesses such as cardiopulmonary disease, renal failure, liver failure, dementia, severe neurological impairment, or malignancy. The advisory panel based its work on the premise that surgery in these circumstances can lead to significant further morbidity, health care utilization, functional decline, prolonged hospital stay or institutionalization, and death, with attendant physical discomfort and psychological distress at the end of these patients’ lives.

Surgeons consulted in the emergency setting for these patients are hampered by patients unable to communicate well because they are in extremis, by surrogates who are unprepared for their role, and by time constraints, lack of familiarity with the patient, poor understanding of the illness by patients and families, prognostic uncertainty, and inadequate advance care planning. In addition, “many surgeons lack skills to engage in conversations about end-of-life care, or are too unfamiliar with palliative options to discuss them well,” or feel obligated to maintain postoperative life support despite the patient’s wishes, said Dr. Zara Cooper, of Ariadne Labs and the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and her associates.

To address these issues and assist surgeons in caring for such patients, an expert panel of 23 national leaders in acute care surgery, general surgery, surgical oncology, palliative medicine, critical care, emergency medicine, anesthesia, and health care innovation was convened at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The focus of the panel’s recommendations was a structured communications framework prototype to facilitate shared decision-making in these difficult circumstances.

Among the panel’s recommendations for surgeons were the following priorities:

• Review the medical record and consult the treatment team to fully understand the patient’s current condition, comorbidities, expected illness trajectory, and preferences for end-of-life care.

• Assess functional performance as part of the routine history and physical to fully understand the patient’s fitness for surgery.

• Formulate a prognosis regarding the patient’s overall health both with and without surgery.

The panel offered a set of principles and specific elements for the meeting with the patient and family:

• The surgeon should begin by introducing himself or herself; according to reports in the literature, physicians fail to do this approximately half of the time.

• Pay attention to nonverbal communication, such as eye contact and physical contact, as this is critical to building rapport. Immediately address pain, anxiety, and other indicators of distress, to maximize the patients’ and the families’ engagement in subsequent medical discussions. “Although adequate analgesia may render a patient unable to make their own decisions, surrogates are more likely to make appropriate decisions when they feel their loved one is comfortable,” the panel noted.

• Allow pauses and silences to occur. Let the patient and the family process information and their own emotions.

• Elicit the patients’ or the surrogates’ understanding of the illness and their views of the patients’ likely trajectory, correcting any inaccuracies. This substantially influences their decisions regarding the aggressiveness of subsequent treatments.

• Inform the patient and family of the life-threatening nature of the patient’s acute condition and its potential impact on the rest of his or her life, including the possibility of prolonged life support, ICU stay, burdensome treatment, and loss of independence. Use accepted techniques for breaking bad news, and check to be sure the patient understands what was conveyed.

• At this point, the surgeon should synthesize and summarize the information from the patient, the family, and the medical record, then pause to give them time to process the information and to assess their emotional state. It is helpful to label and respond to the patient’s emotions at this juncture, and to build empathy with statements such as “I know this is difficult news, and I wish it were different.”

• Describe the benefits, burdens, and range of likely outcomes if surgery is undertaken and if it is not. The surgeon should use nonmedical language to describe symptoms, and should convey his or her expectations regarding length of hospitalization, need for and duration of life support, burdensome symptoms, discharge to an institution, and functional recovery.

• Surgeons should be able to communicate palliative options possible either in combination with surgery or instead of surgery. Palliative care can aid in managing advanced symptoms, providing psychosocial support for patients and caregivers, facilitating interdisciplinary communication, and facilitating medical decisions and care transitions.

• Avoid describing surgical procedures as “doing everything” and palliative care as “doing nothing.” This can make patients and families “feel abandoned, fearful, isolated, and angry, and fails to encompass palliative care’s practices of proactive communication, aggressive symptom management, and timely emotional support to alleviate suffering and affirm quality of life,” the panel said.

• Surgeons should explicitly support the patients’ medical decisions, whether or not they choose surgery.