User login

Is physician-assisted suicide compatible with the Hippocratic Oath?

Do we stand by our Hippocratic Oath when providing physician-assisted suicide?

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is a form of euthanasia in which a physician provides the patient with the pertinent information, and, in certain cases, a prescription for the necessary lethal drugs, so that the individual can willingly and successfully terminate his or her own life. The justification for PAS is the compassionate relief of intractable human suffering. Euthanasia and PAS are accepted practices in European countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Such patients are mentally incapable of making the difficult decision to end their life and therefore should require a psychiatric evaluation to include counseling prior to making a decision to engage in PAS. For patients with mental illness, PAS is even more problematic than for terminally ill patients, because patients may lack the capacity to make rational and responsible decisions. Indeed, there are sizable loopholes where our medical system lacks safeguards and similarly lacks the requirements for a thorough, pre-PAS mental health examination, family notifications, and consultations, and for the minimally necessary legal pressure required to ensure patient cooperation.

Critical role of mental health workers

Although PAS has been legalized in those five U.S. states, its support and cases have stalled in recent years, indicating serious ethical concerns, mostly because of multileveled challenges of combating and delineating cultural stereotypes, quantifying mental capacity, gauging quality of life, and deciding where to situate psychiatrists in the PAS decision.

The psychiatrist’s role is being debated. In the United States, opponents take issue with current PAS-legal state’s legislation regarding psychiatric evaluations. For example, Oregon stipulates a psychiatrist referral only in cases where a physician other than a psychiatrist believes the patient’s judgment is impaired. It’s agreed that psychiatrists have the best skill set to assess a patient’s perceptions. Other PAS-legal states require a psychiatrist or psychologist assessment before making the decision. Unfortunately, though, physicians have rarely referred these patients to psychiatrists before offering PAS as an option.

PAS opponents target standards by which concepts like “quality of life” or “contributing member of society” are judged – specifically, that “unbearable suffering” and its ramifications are ill defined – people whose lives are deemed “not worth living” (including the terminally ill) would be susceptible to “sympathetic death” via PAS that might result from PAS legalization. Opponents also argue that recognizing a suicide “right” contradicts that a significant number of suicide attempters have mental illness and need help. They say that legalizing PAS would enable mentally incapacitated people to commit the irreversible act based on their distorted perceptions without providing them the expected assistance from their profession.1

The use of euthanasia or PAS gradually is trending from physically terminally ill patients toward psychiatrically complex patients. There are cases in which euthanasia or PAS was requested by psychiatric patients who had chronic psychiatric, medical, and psychosocial histories rather than purely physical ailment histories. In one study, Scott Y. H. Kim, MD, PhD, and his associates reviewed cases in the Netherlands in which either euthanasia or PAS for psychiatric disorders was deployed. The granted PAS requests appeared to involve physician judgment without psychiatric input.

The study reviewed 66 cases: 55% of patients had chronic severe conditions with extensive histories of attempted suicides and psychiatric hospitalizations, demonstrating that the granted euthanasia and PAS requests had involved extensive evaluations. However, 11% of cases had no independent psychiatric input, and 24% involved disagreement among the physicians.2 PAS proponents and opponents support the involvement and expertise of psychiatrists in all of this.

Psychiatrists have long contended that suicide attempts are often a “cry for help,” not an earnest act to end one’s life. Legalizing PAS tells suicidal individuals that society does not care whether they live or die – a truly un-Hippocratic stance. The stereotypes tossed around in the PAS debate, which could mean life or death, need to be unpacked with specific criteria attached, rather than preconceptions.

Autonomy of patients and implications of PAS

In the PAS debate, there are serious life concerns exhibited by terminally ill/psychiatrically ill patients over losing their autonomy and becoming a burden to their families and caregivers. Stereotypes must be deconstructed, yes, but such patients generally have been considered to be rendered, by the sum effect of their illnesses, mentally incapable of making the decision to end their lives. Addressing this order of patient life concerns generally has been the realm of social workers, psychologists, and, in the most desirable cases, psychiatrists. Therefore, even in keeping with established practice, some form of competent psychiatric evaluation should be required before considering PAS as a viable option.

The call for this requirement is backed up by a study, which reported that 47% of patients who had considered or committed suicide previously were diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, and 15% had undiagnosed psychiatric disorders.3 Also, inventories of thwarted suicide attempters reveal that most lack the conviction to end their lives, and this obverse phenomenon is backed by a study that revealed that 75% of 96 suicidal patients were found to be ambivalent in their intent to end their lives. Suicide attempters simply may be trying to communicate with people in their lives in order to test their love and care.4 This indicates that those who attempt suicide are predominantly psychiatrically ill and prone to distorted perceptions, impaired judgment, frustration, escapism, and manipulative guilt.

Suicide is abhorrent to most human beings’ sensibilities, because humanity has an innate will to live.5 It is wrong to offer patients life-ending options when they might rejuvenate or ease into death naturally. With the debilitated or elderly, PAS could violate their human rights. If the attitude that they are a burden to society persists, then a certain segment of society might be tempted to avoid their intergenerational obligations to elders, particularly those elders presenting with concurrent mental illnesses. PAS would additionally fuel that problem. This would represent a profound injustice and gross violation of human dignity, while also serving as a denial of basic human rights, particularly the right to life and care.6

Conclusion

The complex physical, psychological, and social challenges associated with PAS and the difficulty in enforcing its laws necessitate more adept alternatives. Instead of conditionally legalizing suicide, we should ease patient suffering with compassion and calibrated treatment.6,7

Terminally ill patients often suffer from depression, affecting their rationality. Adequate counseling, medical care, and psychological care should be the response to terminally ill patients considering suicide. If society accepts that ending a life is a reasonable response to human suffering that could otherwise be treated or reversed, then those with the most serious psychiatric conditions are destined to become more vulnerable. Therefore, physicians and psychiatrists should instead work harder to help patients recover, rather than participating in their quest for death.

Simplistic legal and regulatory oversight is insufficient, because the questions evoked by PAS are complicated by life, death, and ethics. Further research is needed to look into the mechanisms and morality of how psychiatrists and other physicians will make judgments and recommendations that are vital elements in developing regulatory oversight on PAS. Finally, future studies should look at which practices have been successful and which might be deemed unethical.

References

1. Clin Med (Lond). 2010 Aug;109(4):323-5.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):362-8.

3. “The Final Months: A Study of the Lives of 134 Persons Who Committed Suicide,” New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

4. “Why We Shouldn’t Legalize Assisting Suicide, Part I.” Department of Medical Ethics, National Right to Life Committee.

5. “Working with Suicidal Individuals: A Guide to Providing Understanding, Assessment and Support,” Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010.

6. “Always Care, Never Kill: How Physician-Assisted Suicide Endangers the Weak, Corrupts Medicine, Compromises the Family, and Violates Human Dignity and Equality,” Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2015.

7. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 3;156(1 Pt 2):73-104.

Dr. Ahmed is a 2nd-year resident in the psychiatry & behavioral sciences department at the Nassau University Medical Center, New York. Over the last 3 years, he has published and presented papers at national and international forums. His interests include public social psychiatry, health care policy, health disparities, mental health stigma, and undiagnosed and overdiagnosed psychiatric illnesses in children. Dr. Ahmed is a member of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, and the American Association for Social Psychiatry.

Do we stand by our Hippocratic Oath when providing physician-assisted suicide?

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is a form of euthanasia in which a physician provides the patient with the pertinent information, and, in certain cases, a prescription for the necessary lethal drugs, so that the individual can willingly and successfully terminate his or her own life. The justification for PAS is the compassionate relief of intractable human suffering. Euthanasia and PAS are accepted practices in European countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Such patients are mentally incapable of making the difficult decision to end their life and therefore should require a psychiatric evaluation to include counseling prior to making a decision to engage in PAS. For patients with mental illness, PAS is even more problematic than for terminally ill patients, because patients may lack the capacity to make rational and responsible decisions. Indeed, there are sizable loopholes where our medical system lacks safeguards and similarly lacks the requirements for a thorough, pre-PAS mental health examination, family notifications, and consultations, and for the minimally necessary legal pressure required to ensure patient cooperation.

Critical role of mental health workers

Although PAS has been legalized in those five U.S. states, its support and cases have stalled in recent years, indicating serious ethical concerns, mostly because of multileveled challenges of combating and delineating cultural stereotypes, quantifying mental capacity, gauging quality of life, and deciding where to situate psychiatrists in the PAS decision.

The psychiatrist’s role is being debated. In the United States, opponents take issue with current PAS-legal state’s legislation regarding psychiatric evaluations. For example, Oregon stipulates a psychiatrist referral only in cases where a physician other than a psychiatrist believes the patient’s judgment is impaired. It’s agreed that psychiatrists have the best skill set to assess a patient’s perceptions. Other PAS-legal states require a psychiatrist or psychologist assessment before making the decision. Unfortunately, though, physicians have rarely referred these patients to psychiatrists before offering PAS as an option.

PAS opponents target standards by which concepts like “quality of life” or “contributing member of society” are judged – specifically, that “unbearable suffering” and its ramifications are ill defined – people whose lives are deemed “not worth living” (including the terminally ill) would be susceptible to “sympathetic death” via PAS that might result from PAS legalization. Opponents also argue that recognizing a suicide “right” contradicts that a significant number of suicide attempters have mental illness and need help. They say that legalizing PAS would enable mentally incapacitated people to commit the irreversible act based on their distorted perceptions without providing them the expected assistance from their profession.1

The use of euthanasia or PAS gradually is trending from physically terminally ill patients toward psychiatrically complex patients. There are cases in which euthanasia or PAS was requested by psychiatric patients who had chronic psychiatric, medical, and psychosocial histories rather than purely physical ailment histories. In one study, Scott Y. H. Kim, MD, PhD, and his associates reviewed cases in the Netherlands in which either euthanasia or PAS for psychiatric disorders was deployed. The granted PAS requests appeared to involve physician judgment without psychiatric input.

The study reviewed 66 cases: 55% of patients had chronic severe conditions with extensive histories of attempted suicides and psychiatric hospitalizations, demonstrating that the granted euthanasia and PAS requests had involved extensive evaluations. However, 11% of cases had no independent psychiatric input, and 24% involved disagreement among the physicians.2 PAS proponents and opponents support the involvement and expertise of psychiatrists in all of this.

Psychiatrists have long contended that suicide attempts are often a “cry for help,” not an earnest act to end one’s life. Legalizing PAS tells suicidal individuals that society does not care whether they live or die – a truly un-Hippocratic stance. The stereotypes tossed around in the PAS debate, which could mean life or death, need to be unpacked with specific criteria attached, rather than preconceptions.

Autonomy of patients and implications of PAS

In the PAS debate, there are serious life concerns exhibited by terminally ill/psychiatrically ill patients over losing their autonomy and becoming a burden to their families and caregivers. Stereotypes must be deconstructed, yes, but such patients generally have been considered to be rendered, by the sum effect of their illnesses, mentally incapable of making the decision to end their lives. Addressing this order of patient life concerns generally has been the realm of social workers, psychologists, and, in the most desirable cases, psychiatrists. Therefore, even in keeping with established practice, some form of competent psychiatric evaluation should be required before considering PAS as a viable option.

The call for this requirement is backed up by a study, which reported that 47% of patients who had considered or committed suicide previously were diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, and 15% had undiagnosed psychiatric disorders.3 Also, inventories of thwarted suicide attempters reveal that most lack the conviction to end their lives, and this obverse phenomenon is backed by a study that revealed that 75% of 96 suicidal patients were found to be ambivalent in their intent to end their lives. Suicide attempters simply may be trying to communicate with people in their lives in order to test their love and care.4 This indicates that those who attempt suicide are predominantly psychiatrically ill and prone to distorted perceptions, impaired judgment, frustration, escapism, and manipulative guilt.

Suicide is abhorrent to most human beings’ sensibilities, because humanity has an innate will to live.5 It is wrong to offer patients life-ending options when they might rejuvenate or ease into death naturally. With the debilitated or elderly, PAS could violate their human rights. If the attitude that they are a burden to society persists, then a certain segment of society might be tempted to avoid their intergenerational obligations to elders, particularly those elders presenting with concurrent mental illnesses. PAS would additionally fuel that problem. This would represent a profound injustice and gross violation of human dignity, while also serving as a denial of basic human rights, particularly the right to life and care.6

Conclusion

The complex physical, psychological, and social challenges associated with PAS and the difficulty in enforcing its laws necessitate more adept alternatives. Instead of conditionally legalizing suicide, we should ease patient suffering with compassion and calibrated treatment.6,7

Terminally ill patients often suffer from depression, affecting their rationality. Adequate counseling, medical care, and psychological care should be the response to terminally ill patients considering suicide. If society accepts that ending a life is a reasonable response to human suffering that could otherwise be treated or reversed, then those with the most serious psychiatric conditions are destined to become more vulnerable. Therefore, physicians and psychiatrists should instead work harder to help patients recover, rather than participating in their quest for death.

Simplistic legal and regulatory oversight is insufficient, because the questions evoked by PAS are complicated by life, death, and ethics. Further research is needed to look into the mechanisms and morality of how psychiatrists and other physicians will make judgments and recommendations that are vital elements in developing regulatory oversight on PAS. Finally, future studies should look at which practices have been successful and which might be deemed unethical.

References

1. Clin Med (Lond). 2010 Aug;109(4):323-5.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):362-8.

3. “The Final Months: A Study of the Lives of 134 Persons Who Committed Suicide,” New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

4. “Why We Shouldn’t Legalize Assisting Suicide, Part I.” Department of Medical Ethics, National Right to Life Committee.

5. “Working with Suicidal Individuals: A Guide to Providing Understanding, Assessment and Support,” Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010.

6. “Always Care, Never Kill: How Physician-Assisted Suicide Endangers the Weak, Corrupts Medicine, Compromises the Family, and Violates Human Dignity and Equality,” Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2015.

7. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 3;156(1 Pt 2):73-104.

Dr. Ahmed is a 2nd-year resident in the psychiatry & behavioral sciences department at the Nassau University Medical Center, New York. Over the last 3 years, he has published and presented papers at national and international forums. His interests include public social psychiatry, health care policy, health disparities, mental health stigma, and undiagnosed and overdiagnosed psychiatric illnesses in children. Dr. Ahmed is a member of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, and the American Association for Social Psychiatry.

Do we stand by our Hippocratic Oath when providing physician-assisted suicide?

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is a form of euthanasia in which a physician provides the patient with the pertinent information, and, in certain cases, a prescription for the necessary lethal drugs, so that the individual can willingly and successfully terminate his or her own life. The justification for PAS is the compassionate relief of intractable human suffering. Euthanasia and PAS are accepted practices in European countries such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Such patients are mentally incapable of making the difficult decision to end their life and therefore should require a psychiatric evaluation to include counseling prior to making a decision to engage in PAS. For patients with mental illness, PAS is even more problematic than for terminally ill patients, because patients may lack the capacity to make rational and responsible decisions. Indeed, there are sizable loopholes where our medical system lacks safeguards and similarly lacks the requirements for a thorough, pre-PAS mental health examination, family notifications, and consultations, and for the minimally necessary legal pressure required to ensure patient cooperation.

Critical role of mental health workers

Although PAS has been legalized in those five U.S. states, its support and cases have stalled in recent years, indicating serious ethical concerns, mostly because of multileveled challenges of combating and delineating cultural stereotypes, quantifying mental capacity, gauging quality of life, and deciding where to situate psychiatrists in the PAS decision.

The psychiatrist’s role is being debated. In the United States, opponents take issue with current PAS-legal state’s legislation regarding psychiatric evaluations. For example, Oregon stipulates a psychiatrist referral only in cases where a physician other than a psychiatrist believes the patient’s judgment is impaired. It’s agreed that psychiatrists have the best skill set to assess a patient’s perceptions. Other PAS-legal states require a psychiatrist or psychologist assessment before making the decision. Unfortunately, though, physicians have rarely referred these patients to psychiatrists before offering PAS as an option.

PAS opponents target standards by which concepts like “quality of life” or “contributing member of society” are judged – specifically, that “unbearable suffering” and its ramifications are ill defined – people whose lives are deemed “not worth living” (including the terminally ill) would be susceptible to “sympathetic death” via PAS that might result from PAS legalization. Opponents also argue that recognizing a suicide “right” contradicts that a significant number of suicide attempters have mental illness and need help. They say that legalizing PAS would enable mentally incapacitated people to commit the irreversible act based on their distorted perceptions without providing them the expected assistance from their profession.1

The use of euthanasia or PAS gradually is trending from physically terminally ill patients toward psychiatrically complex patients. There are cases in which euthanasia or PAS was requested by psychiatric patients who had chronic psychiatric, medical, and psychosocial histories rather than purely physical ailment histories. In one study, Scott Y. H. Kim, MD, PhD, and his associates reviewed cases in the Netherlands in which either euthanasia or PAS for psychiatric disorders was deployed. The granted PAS requests appeared to involve physician judgment without psychiatric input.

The study reviewed 66 cases: 55% of patients had chronic severe conditions with extensive histories of attempted suicides and psychiatric hospitalizations, demonstrating that the granted euthanasia and PAS requests had involved extensive evaluations. However, 11% of cases had no independent psychiatric input, and 24% involved disagreement among the physicians.2 PAS proponents and opponents support the involvement and expertise of psychiatrists in all of this.

Psychiatrists have long contended that suicide attempts are often a “cry for help,” not an earnest act to end one’s life. Legalizing PAS tells suicidal individuals that society does not care whether they live or die – a truly un-Hippocratic stance. The stereotypes tossed around in the PAS debate, which could mean life or death, need to be unpacked with specific criteria attached, rather than preconceptions.

Autonomy of patients and implications of PAS

In the PAS debate, there are serious life concerns exhibited by terminally ill/psychiatrically ill patients over losing their autonomy and becoming a burden to their families and caregivers. Stereotypes must be deconstructed, yes, but such patients generally have been considered to be rendered, by the sum effect of their illnesses, mentally incapable of making the decision to end their lives. Addressing this order of patient life concerns generally has been the realm of social workers, psychologists, and, in the most desirable cases, psychiatrists. Therefore, even in keeping with established practice, some form of competent psychiatric evaluation should be required before considering PAS as a viable option.

The call for this requirement is backed up by a study, which reported that 47% of patients who had considered or committed suicide previously were diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, and 15% had undiagnosed psychiatric disorders.3 Also, inventories of thwarted suicide attempters reveal that most lack the conviction to end their lives, and this obverse phenomenon is backed by a study that revealed that 75% of 96 suicidal patients were found to be ambivalent in their intent to end their lives. Suicide attempters simply may be trying to communicate with people in their lives in order to test their love and care.4 This indicates that those who attempt suicide are predominantly psychiatrically ill and prone to distorted perceptions, impaired judgment, frustration, escapism, and manipulative guilt.

Suicide is abhorrent to most human beings’ sensibilities, because humanity has an innate will to live.5 It is wrong to offer patients life-ending options when they might rejuvenate or ease into death naturally. With the debilitated or elderly, PAS could violate their human rights. If the attitude that they are a burden to society persists, then a certain segment of society might be tempted to avoid their intergenerational obligations to elders, particularly those elders presenting with concurrent mental illnesses. PAS would additionally fuel that problem. This would represent a profound injustice and gross violation of human dignity, while also serving as a denial of basic human rights, particularly the right to life and care.6

Conclusion

The complex physical, psychological, and social challenges associated with PAS and the difficulty in enforcing its laws necessitate more adept alternatives. Instead of conditionally legalizing suicide, we should ease patient suffering with compassion and calibrated treatment.6,7

Terminally ill patients often suffer from depression, affecting their rationality. Adequate counseling, medical care, and psychological care should be the response to terminally ill patients considering suicide. If society accepts that ending a life is a reasonable response to human suffering that could otherwise be treated or reversed, then those with the most serious psychiatric conditions are destined to become more vulnerable. Therefore, physicians and psychiatrists should instead work harder to help patients recover, rather than participating in their quest for death.

Simplistic legal and regulatory oversight is insufficient, because the questions evoked by PAS are complicated by life, death, and ethics. Further research is needed to look into the mechanisms and morality of how psychiatrists and other physicians will make judgments and recommendations that are vital elements in developing regulatory oversight on PAS. Finally, future studies should look at which practices have been successful and which might be deemed unethical.

References

1. Clin Med (Lond). 2010 Aug;109(4):323-5.

2. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(4):362-8.

3. “The Final Months: A Study of the Lives of 134 Persons Who Committed Suicide,” New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

4. “Why We Shouldn’t Legalize Assisting Suicide, Part I.” Department of Medical Ethics, National Right to Life Committee.

5. “Working with Suicidal Individuals: A Guide to Providing Understanding, Assessment and Support,” Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010.

6. “Always Care, Never Kill: How Physician-Assisted Suicide Endangers the Weak, Corrupts Medicine, Compromises the Family, and Violates Human Dignity and Equality,” Washington: The Heritage Foundation, 2015.

7. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 3;156(1 Pt 2):73-104.

Dr. Ahmed is a 2nd-year resident in the psychiatry & behavioral sciences department at the Nassau University Medical Center, New York. Over the last 3 years, he has published and presented papers at national and international forums. His interests include public social psychiatry, health care policy, health disparities, mental health stigma, and undiagnosed and overdiagnosed psychiatric illnesses in children. Dr. Ahmed is a member of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, and the American Association for Social Psychiatry.

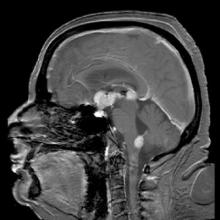

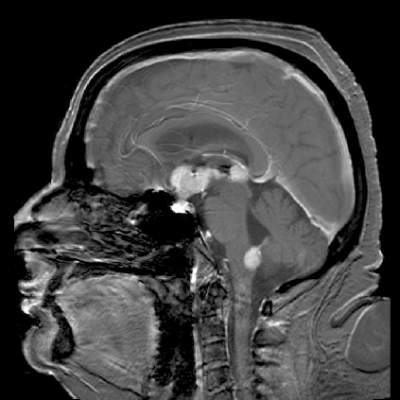

Less cognitive decline with stereotactic radiosurgery after brain metastases resection

BOSTON – For patients with resected brain metastases, stereotactic radiosurgery offers survival comparable with what’s seen with whole-brain radiotherapy, but with better quality of life and more effective preservation of cognitive function, investigators reported.

In the phase III N107C trial, there was no difference in overall survival between patients who were randomly assigned to undergo stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) or whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), but patients who underwent WBRT had a twofold greater decline in cognitive function, compared with patients who underwent SRS, Paul D. Brown, MD, a radiation oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

In a similar prospective, randomized study, Anita Mahajan, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston compared postoperative SRS after complete resection with observation alone in 128 patients, and found that although there was no difference in either distant brain metastases or overall survival, SRS was associated with significant improvements in local control.

“I think that going forward with the next patient I see with this scenario, I’m going to be a bit better informed and be able to inform my patient better of the trade-offs involved with regards to the decision of SRS vs. whole-brain radiotherapy,” commented George Rodrigues, MD, from the London (Ontario) Health Sciences Center in Canada. Dr. Rodrigues moderated a briefing during which Dr. Brown and Dr. Mahajan presented their data.

WBRT has been the standard of care for improving local control following surgical resection of brain metastases, but it does not offer a survival benefit and comes at a significant cost in side effects, including alopecia, fatigue, erythema, and, most distressing to patients, significant decline in cognitive function.

The precision of radiosurgery, on the other hand, allows the radiation dose to be concentrated on the surgical bed, limiting exposure of surrounding tissues and structures. For this reason, many centers have begun to adopt SRS for patients with resected brain metastases, but there is not level I evidence to back it up, Dr. Brown said.

WBRT vs. SRS

To rectify this situation, Dr. Brown and his colleagues at the Mayo Clinic and 47 other institutions conducted a clinical trial in 194 patients with one to four brain metastases.

Following surgical resection, the patients were stratified by age, duration of extracranial disease control, number of preoperative metastases, histology, maximum diameter of the resection cavity, and institution, and then randomly assigned to undergo either WBRT or SRS.

Patients were assessed for cognitive function (a coprimary endpoint with overall survival) at baseline and approximately every 3 months thereafter for up to 24 months. Other assessments included MRI scans, and FACT-Br (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain), a quality-of-life instrument.

After a median follow-up of 18.7 months, there was no difference in median overall survival, which was 11.5 months for WBRT and 11.8 months for SRS.

There was, however, a significant difference in cognitive deterioration–free survival, which was 2.8 months for WBRT vs. 3.3 months for SRS. The hazard ratio for WBRT was 2.05 (P = .0001). Cognitive deterioration–free survival rates at 6 months were 5.4% and 22.9%, respectively (P = .0012).

The declines in cognitive function were accounted for by significant differences in the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) domains of total and delayed recall and in the Trail Making Test (Part A).

Overall brain disease control was significantly better with WBRT than with SRS at 3 months (P = .003) and at 6 and 12 months (P less than .001 for each time point).

Surgical bed control was similar between the treatment groups at 6 and 12 months, but was significantly better with WBRT at 12 months, with surgical bed relapse occurring in 21.8% and 44.4% of patients, respectively.

Patients treated with SRS reported significantly better physical well being at 3 and 6 months (P = .002 and .014, respectively). There were 18 grade 3 or greater radiation-related adverse events among patients treated with WBRT, compared with 7 among patients treated with SRS.

SRS vs. observation

In the MD Anderson study, 45% of patients who underwent observation alone had local control of disease at 12 months, compared with 72% treated with SRS. The hazard ratio for SRS was 0.46 (P = .01). The median time to local recurrence was 7.6 months among patients on observation only, but no time point was reached for SRS-treated patients.

The evidence from the two trials suggests that “radiosurgery is a, but not the, standard of care following resection for brain metastasis,” said Vinai Gondi, MD, of the Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center in Warrenville, Ill., the invited discussant.

“While the MD Anderson trial clearly demonstrated that radiosurgery reduces the risk of surgical bed relapse, the N107C trial demonstrated a 44% risk of surgical bed relapse, a rate that is arguably too high in regards to the long survival of resected brain metastasis patients, and it also challenges and risks the resection of surgical bed relapse following radiosurgery,” he said.

The N107C trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The MD Anderson trial was funded by a Cancer Center Grant. Dr. Brown, Dr. Mahajan, and Dr. Rodrigues reported no conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – For patients with resected brain metastases, stereotactic radiosurgery offers survival comparable with what’s seen with whole-brain radiotherapy, but with better quality of life and more effective preservation of cognitive function, investigators reported.

In the phase III N107C trial, there was no difference in overall survival between patients who were randomly assigned to undergo stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) or whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), but patients who underwent WBRT had a twofold greater decline in cognitive function, compared with patients who underwent SRS, Paul D. Brown, MD, a radiation oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

In a similar prospective, randomized study, Anita Mahajan, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston compared postoperative SRS after complete resection with observation alone in 128 patients, and found that although there was no difference in either distant brain metastases or overall survival, SRS was associated with significant improvements in local control.

“I think that going forward with the next patient I see with this scenario, I’m going to be a bit better informed and be able to inform my patient better of the trade-offs involved with regards to the decision of SRS vs. whole-brain radiotherapy,” commented George Rodrigues, MD, from the London (Ontario) Health Sciences Center in Canada. Dr. Rodrigues moderated a briefing during which Dr. Brown and Dr. Mahajan presented their data.

WBRT has been the standard of care for improving local control following surgical resection of brain metastases, but it does not offer a survival benefit and comes at a significant cost in side effects, including alopecia, fatigue, erythema, and, most distressing to patients, significant decline in cognitive function.

The precision of radiosurgery, on the other hand, allows the radiation dose to be concentrated on the surgical bed, limiting exposure of surrounding tissues and structures. For this reason, many centers have begun to adopt SRS for patients with resected brain metastases, but there is not level I evidence to back it up, Dr. Brown said.

WBRT vs. SRS

To rectify this situation, Dr. Brown and his colleagues at the Mayo Clinic and 47 other institutions conducted a clinical trial in 194 patients with one to four brain metastases.

Following surgical resection, the patients were stratified by age, duration of extracranial disease control, number of preoperative metastases, histology, maximum diameter of the resection cavity, and institution, and then randomly assigned to undergo either WBRT or SRS.

Patients were assessed for cognitive function (a coprimary endpoint with overall survival) at baseline and approximately every 3 months thereafter for up to 24 months. Other assessments included MRI scans, and FACT-Br (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain), a quality-of-life instrument.

After a median follow-up of 18.7 months, there was no difference in median overall survival, which was 11.5 months for WBRT and 11.8 months for SRS.

There was, however, a significant difference in cognitive deterioration–free survival, which was 2.8 months for WBRT vs. 3.3 months for SRS. The hazard ratio for WBRT was 2.05 (P = .0001). Cognitive deterioration–free survival rates at 6 months were 5.4% and 22.9%, respectively (P = .0012).

The declines in cognitive function were accounted for by significant differences in the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) domains of total and delayed recall and in the Trail Making Test (Part A).

Overall brain disease control was significantly better with WBRT than with SRS at 3 months (P = .003) and at 6 and 12 months (P less than .001 for each time point).

Surgical bed control was similar between the treatment groups at 6 and 12 months, but was significantly better with WBRT at 12 months, with surgical bed relapse occurring in 21.8% and 44.4% of patients, respectively.

Patients treated with SRS reported significantly better physical well being at 3 and 6 months (P = .002 and .014, respectively). There were 18 grade 3 or greater radiation-related adverse events among patients treated with WBRT, compared with 7 among patients treated with SRS.

SRS vs. observation

In the MD Anderson study, 45% of patients who underwent observation alone had local control of disease at 12 months, compared with 72% treated with SRS. The hazard ratio for SRS was 0.46 (P = .01). The median time to local recurrence was 7.6 months among patients on observation only, but no time point was reached for SRS-treated patients.

The evidence from the two trials suggests that “radiosurgery is a, but not the, standard of care following resection for brain metastasis,” said Vinai Gondi, MD, of the Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center in Warrenville, Ill., the invited discussant.

“While the MD Anderson trial clearly demonstrated that radiosurgery reduces the risk of surgical bed relapse, the N107C trial demonstrated a 44% risk of surgical bed relapse, a rate that is arguably too high in regards to the long survival of resected brain metastasis patients, and it also challenges and risks the resection of surgical bed relapse following radiosurgery,” he said.

The N107C trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The MD Anderson trial was funded by a Cancer Center Grant. Dr. Brown, Dr. Mahajan, and Dr. Rodrigues reported no conflicts of interest.

BOSTON – For patients with resected brain metastases, stereotactic radiosurgery offers survival comparable with what’s seen with whole-brain radiotherapy, but with better quality of life and more effective preservation of cognitive function, investigators reported.

In the phase III N107C trial, there was no difference in overall survival between patients who were randomly assigned to undergo stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) or whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), but patients who underwent WBRT had a twofold greater decline in cognitive function, compared with patients who underwent SRS, Paul D. Brown, MD, a radiation oncologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

In a similar prospective, randomized study, Anita Mahajan, MD, and colleagues from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston compared postoperative SRS after complete resection with observation alone in 128 patients, and found that although there was no difference in either distant brain metastases or overall survival, SRS was associated with significant improvements in local control.

“I think that going forward with the next patient I see with this scenario, I’m going to be a bit better informed and be able to inform my patient better of the trade-offs involved with regards to the decision of SRS vs. whole-brain radiotherapy,” commented George Rodrigues, MD, from the London (Ontario) Health Sciences Center in Canada. Dr. Rodrigues moderated a briefing during which Dr. Brown and Dr. Mahajan presented their data.

WBRT has been the standard of care for improving local control following surgical resection of brain metastases, but it does not offer a survival benefit and comes at a significant cost in side effects, including alopecia, fatigue, erythema, and, most distressing to patients, significant decline in cognitive function.

The precision of radiosurgery, on the other hand, allows the radiation dose to be concentrated on the surgical bed, limiting exposure of surrounding tissues and structures. For this reason, many centers have begun to adopt SRS for patients with resected brain metastases, but there is not level I evidence to back it up, Dr. Brown said.

WBRT vs. SRS

To rectify this situation, Dr. Brown and his colleagues at the Mayo Clinic and 47 other institutions conducted a clinical trial in 194 patients with one to four brain metastases.

Following surgical resection, the patients were stratified by age, duration of extracranial disease control, number of preoperative metastases, histology, maximum diameter of the resection cavity, and institution, and then randomly assigned to undergo either WBRT or SRS.

Patients were assessed for cognitive function (a coprimary endpoint with overall survival) at baseline and approximately every 3 months thereafter for up to 24 months. Other assessments included MRI scans, and FACT-Br (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain), a quality-of-life instrument.

After a median follow-up of 18.7 months, there was no difference in median overall survival, which was 11.5 months for WBRT and 11.8 months for SRS.

There was, however, a significant difference in cognitive deterioration–free survival, which was 2.8 months for WBRT vs. 3.3 months for SRS. The hazard ratio for WBRT was 2.05 (P = .0001). Cognitive deterioration–free survival rates at 6 months were 5.4% and 22.9%, respectively (P = .0012).

The declines in cognitive function were accounted for by significant differences in the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) domains of total and delayed recall and in the Trail Making Test (Part A).

Overall brain disease control was significantly better with WBRT than with SRS at 3 months (P = .003) and at 6 and 12 months (P less than .001 for each time point).

Surgical bed control was similar between the treatment groups at 6 and 12 months, but was significantly better with WBRT at 12 months, with surgical bed relapse occurring in 21.8% and 44.4% of patients, respectively.

Patients treated with SRS reported significantly better physical well being at 3 and 6 months (P = .002 and .014, respectively). There were 18 grade 3 or greater radiation-related adverse events among patients treated with WBRT, compared with 7 among patients treated with SRS.

SRS vs. observation

In the MD Anderson study, 45% of patients who underwent observation alone had local control of disease at 12 months, compared with 72% treated with SRS. The hazard ratio for SRS was 0.46 (P = .01). The median time to local recurrence was 7.6 months among patients on observation only, but no time point was reached for SRS-treated patients.

The evidence from the two trials suggests that “radiosurgery is a, but not the, standard of care following resection for brain metastasis,” said Vinai Gondi, MD, of the Northwestern Medicine Cancer Center in Warrenville, Ill., the invited discussant.

“While the MD Anderson trial clearly demonstrated that radiosurgery reduces the risk of surgical bed relapse, the N107C trial demonstrated a 44% risk of surgical bed relapse, a rate that is arguably too high in regards to the long survival of resected brain metastasis patients, and it also challenges and risks the resection of surgical bed relapse following radiosurgery,” he said.

The N107C trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The MD Anderson trial was funded by a Cancer Center Grant. Dr. Brown, Dr. Mahajan, and Dr. Rodrigues reported no conflicts of interest.

AT ASTRO ANNUAL MEETING 2016

Key clinical point: Stereotactic radiosurgery following brain metastases resection was associated with similar survival but less toxicity than was whole-brain radiation therapy.

Major finding: WBRT was associated with a twofold greater risk for cognitive deterioration than SRS in one study, and SRS provided better local control than observation alone in another study.

Data source: A randomized, phase III trial in 194 patients from 48 centers in the United States and Canada, and a randomized trial in 128 patients from the MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Disclosures: The N107C trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology. The MD Anderson trial was funded by a Cancer Center Grant. Dr. Brown, Dr. Mahajan, and Dr. Rodrigues reported no conflicts of interest.

Heat shock protein peptide vaccine appears safe, effective for glioblastoma patients

Chicago – A newly developed heat shock protein peptide vaccination appears to be safe and effective in treating patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM), according to the results of a phase II single arm study.

In adding the vaccine to standard therapy for 46 patients with newly diagnosed GBM, median overall survival was 23.8 months, and there were no grade 3 or 4 adverse events associated with the vaccine, lead author Dr. Orin Bloch of Northwestern University, Chicago, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Standard therapy typically results in a median survival of 16 months, he said.

“There is a lot of information out there right now regarding CNS and other solid organ tumors particularly in the area of checkpoint modulation and its ability to stimulate an innate immune response against a tumor. I think in GBM we are facing a bit of a different scenario, however, because the tumor exists in a very privileged area behind the blood brain barrier and doesn’t regularly metastasize beyond the CNS,” Dr. Bloch said.

Therefore, only modulating checkpoints without stimulating and educating the immune system may not be the most effective approach. Adaptive immunity through vaccination or some other form of stimulation might be more successful, Dr. Bloch said.

“As a way of inducing immune stimulation and education using tumor-autologous peptides, one can capitalize on the native system of heat shock stimulation. Heat shock proteins are chaperone proteins that are ubiquitously expressed in cells and they’re bound to any number of intracellular peptides at any one time including, in tumor cells, neoantigens. If you extract these heat shock proteins with their bound antigens and deliver them in a naked form into the systemic circulation, their uptake into antigen-presenting cells through the CD91 receptor [will result in] the peptide [being] cleaved and presented on MHC class one and two for stimulation of CD8- and CD4-positive T cell response,” he said.

Heat shock proteins also interact with toll-like receptors and stimulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, “acting as their own adjuvant,” Dr. Bloch further explained. Utilizing heat shock proteins activates both the innate and adaptive immune responses.

“This is an ideal platform for developing an immunotherapy for glioblastoma,” Dr. Bloch said.

In this phase II study, 46 adult patients with GBM underwent surgical resection of their tumors followed by chemoradiotherapy. At least four 25-microgram doses of vaccine were generated from tissue obtained during surgery. Within 5 weeks of completing radiotherapy, patients began receiving weekly vaccinations in combination with adjuvant temozolomide. Patients continued receiving vaccines until depletion or until tumor progression.

Median progression-free survival was 17.8 months (95% confidence interval, 11.3-21.6) and median overall survival was 23.8 months (95% CI, 19.8-30.2).

PD-L1 expression on circulating monocytes was also measured from peripheral blood samples obtained during surgery. Patients were classified as having either high PD-L1 expression (54.5% or more of monocytes) or low PD-L1 expression. Among patients classified as having high PD-L1 expression, the median overall survival was 18.0 months (95% CI, 10.0-23.3). Patients who had low PD-L1 expression had a significantly longer median overall survival time of 44.7 months with a confidence interval not calculable (hazard ratio, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.36-8.23; P = .003).

Finally, a multivariate proportional hazards model showed the MGMT methylation status and PD-L1 expression were the two greatest independent predictors of survival.

“Survival among patients who received the HSPPV-96 was greater than expected compared to historical controls... These results certainly, we feel, provide rationale for a phase III trial of vaccine plus standard of care versus standard of care alone,” Dr. Bloch said.

“PD-L1 expression on circulating myeloid cells is independently predictive of clinical response to vaccination, and it suggests that the low PD-L1 expressing population will most benefit from this anti-tumor vaccination scheme, but it also suggests that high PD-L1 expressing patients may benefit from combined checkpoint inhibition. Systemic immunosuppression driven by peripheral monocyte expression of PD-L1 is a previously unidentified factor that may mitigate vaccine efficacy,” Dr. Bloch further commented.

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Brain Tumor Society, the American Brain Tumor Association, and Accelerated Brain Cancer Cure. Dr. Bloch reporting having no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Chicago – A newly developed heat shock protein peptide vaccination appears to be safe and effective in treating patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM), according to the results of a phase II single arm study.

In adding the vaccine to standard therapy for 46 patients with newly diagnosed GBM, median overall survival was 23.8 months, and there were no grade 3 or 4 adverse events associated with the vaccine, lead author Dr. Orin Bloch of Northwestern University, Chicago, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Standard therapy typically results in a median survival of 16 months, he said.

“There is a lot of information out there right now regarding CNS and other solid organ tumors particularly in the area of checkpoint modulation and its ability to stimulate an innate immune response against a tumor. I think in GBM we are facing a bit of a different scenario, however, because the tumor exists in a very privileged area behind the blood brain barrier and doesn’t regularly metastasize beyond the CNS,” Dr. Bloch said.

Therefore, only modulating checkpoints without stimulating and educating the immune system may not be the most effective approach. Adaptive immunity through vaccination or some other form of stimulation might be more successful, Dr. Bloch said.

“As a way of inducing immune stimulation and education using tumor-autologous peptides, one can capitalize on the native system of heat shock stimulation. Heat shock proteins are chaperone proteins that are ubiquitously expressed in cells and they’re bound to any number of intracellular peptides at any one time including, in tumor cells, neoantigens. If you extract these heat shock proteins with their bound antigens and deliver them in a naked form into the systemic circulation, their uptake into antigen-presenting cells through the CD91 receptor [will result in] the peptide [being] cleaved and presented on MHC class one and two for stimulation of CD8- and CD4-positive T cell response,” he said.

Heat shock proteins also interact with toll-like receptors and stimulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, “acting as their own adjuvant,” Dr. Bloch further explained. Utilizing heat shock proteins activates both the innate and adaptive immune responses.

“This is an ideal platform for developing an immunotherapy for glioblastoma,” Dr. Bloch said.

In this phase II study, 46 adult patients with GBM underwent surgical resection of their tumors followed by chemoradiotherapy. At least four 25-microgram doses of vaccine were generated from tissue obtained during surgery. Within 5 weeks of completing radiotherapy, patients began receiving weekly vaccinations in combination with adjuvant temozolomide. Patients continued receiving vaccines until depletion or until tumor progression.

Median progression-free survival was 17.8 months (95% confidence interval, 11.3-21.6) and median overall survival was 23.8 months (95% CI, 19.8-30.2).

PD-L1 expression on circulating monocytes was also measured from peripheral blood samples obtained during surgery. Patients were classified as having either high PD-L1 expression (54.5% or more of monocytes) or low PD-L1 expression. Among patients classified as having high PD-L1 expression, the median overall survival was 18.0 months (95% CI, 10.0-23.3). Patients who had low PD-L1 expression had a significantly longer median overall survival time of 44.7 months with a confidence interval not calculable (hazard ratio, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.36-8.23; P = .003).

Finally, a multivariate proportional hazards model showed the MGMT methylation status and PD-L1 expression were the two greatest independent predictors of survival.

“Survival among patients who received the HSPPV-96 was greater than expected compared to historical controls... These results certainly, we feel, provide rationale for a phase III trial of vaccine plus standard of care versus standard of care alone,” Dr. Bloch said.

“PD-L1 expression on circulating myeloid cells is independently predictive of clinical response to vaccination, and it suggests that the low PD-L1 expressing population will most benefit from this anti-tumor vaccination scheme, but it also suggests that high PD-L1 expressing patients may benefit from combined checkpoint inhibition. Systemic immunosuppression driven by peripheral monocyte expression of PD-L1 is a previously unidentified factor that may mitigate vaccine efficacy,” Dr. Bloch further commented.

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Brain Tumor Society, the American Brain Tumor Association, and Accelerated Brain Cancer Cure. Dr. Bloch reporting having no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

Chicago – A newly developed heat shock protein peptide vaccination appears to be safe and effective in treating patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM), according to the results of a phase II single arm study.

In adding the vaccine to standard therapy for 46 patients with newly diagnosed GBM, median overall survival was 23.8 months, and there were no grade 3 or 4 adverse events associated with the vaccine, lead author Dr. Orin Bloch of Northwestern University, Chicago, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Standard therapy typically results in a median survival of 16 months, he said.

“There is a lot of information out there right now regarding CNS and other solid organ tumors particularly in the area of checkpoint modulation and its ability to stimulate an innate immune response against a tumor. I think in GBM we are facing a bit of a different scenario, however, because the tumor exists in a very privileged area behind the blood brain barrier and doesn’t regularly metastasize beyond the CNS,” Dr. Bloch said.

Therefore, only modulating checkpoints without stimulating and educating the immune system may not be the most effective approach. Adaptive immunity through vaccination or some other form of stimulation might be more successful, Dr. Bloch said.

“As a way of inducing immune stimulation and education using tumor-autologous peptides, one can capitalize on the native system of heat shock stimulation. Heat shock proteins are chaperone proteins that are ubiquitously expressed in cells and they’re bound to any number of intracellular peptides at any one time including, in tumor cells, neoantigens. If you extract these heat shock proteins with their bound antigens and deliver them in a naked form into the systemic circulation, their uptake into antigen-presenting cells through the CD91 receptor [will result in] the peptide [being] cleaved and presented on MHC class one and two for stimulation of CD8- and CD4-positive T cell response,” he said.

Heat shock proteins also interact with toll-like receptors and stimulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, “acting as their own adjuvant,” Dr. Bloch further explained. Utilizing heat shock proteins activates both the innate and adaptive immune responses.

“This is an ideal platform for developing an immunotherapy for glioblastoma,” Dr. Bloch said.

In this phase II study, 46 adult patients with GBM underwent surgical resection of their tumors followed by chemoradiotherapy. At least four 25-microgram doses of vaccine were generated from tissue obtained during surgery. Within 5 weeks of completing radiotherapy, patients began receiving weekly vaccinations in combination with adjuvant temozolomide. Patients continued receiving vaccines until depletion or until tumor progression.

Median progression-free survival was 17.8 months (95% confidence interval, 11.3-21.6) and median overall survival was 23.8 months (95% CI, 19.8-30.2).

PD-L1 expression on circulating monocytes was also measured from peripheral blood samples obtained during surgery. Patients were classified as having either high PD-L1 expression (54.5% or more of monocytes) or low PD-L1 expression. Among patients classified as having high PD-L1 expression, the median overall survival was 18.0 months (95% CI, 10.0-23.3). Patients who had low PD-L1 expression had a significantly longer median overall survival time of 44.7 months with a confidence interval not calculable (hazard ratio, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.36-8.23; P = .003).

Finally, a multivariate proportional hazards model showed the MGMT methylation status and PD-L1 expression were the two greatest independent predictors of survival.

“Survival among patients who received the HSPPV-96 was greater than expected compared to historical controls... These results certainly, we feel, provide rationale for a phase III trial of vaccine plus standard of care versus standard of care alone,” Dr. Bloch said.

“PD-L1 expression on circulating myeloid cells is independently predictive of clinical response to vaccination, and it suggests that the low PD-L1 expressing population will most benefit from this anti-tumor vaccination scheme, but it also suggests that high PD-L1 expressing patients may benefit from combined checkpoint inhibition. Systemic immunosuppression driven by peripheral monocyte expression of PD-L1 is a previously unidentified factor that may mitigate vaccine efficacy,” Dr. Bloch further commented.

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Brain Tumor Society, the American Brain Tumor Association, and Accelerated Brain Cancer Cure. Dr. Bloch reporting having no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @jessnicolecraig

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A heat shock protein peptide vaccine appears safe and effective for patients with glioblastoma in an early stage trial.

Major finding: Median progression-free survival was 17.8 months (95% CI, 11.3-21.6). Median overall survival was 23.8 months (95% CI, 19.8-30.2).

Data source: A phase II single arm study of 46 adult patients with glioblastoma.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Brain Tumor Society, the American Brain Tumor Association, and Accelerated Brain Cancer Cure. Dr. Bloch reporting having no relevant disclosures.

IL-2 adds only toxicity to neuroblastoma antibody tx

CHICAGO – Adding the cytokine IL-2 to front-line therapy with the anti-GD2 antibody ch14.18/CHO provided no additional survival benefit and only added to toxicity in the treatment of pediatric patients with high-risk neuroblastoma (NB), Dr. Ruth Ladenstein reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

A form of the antibody (dinutuximab) is approved for use in combination with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, IL-2, and 13-cis-retinoic acid (RA) to treat high risk NB. A previous study (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324-34) showed that a combination of ch14.18 and the cytokines improved event free survival to 66% at 2 years, but the role of cytokines in this context remained unclear. Dr. Ladenstein and associates therefore performed a phase III trial that randomized patients to the antibody with or without subcutaneous (sc) IL-2.

High-risk NB was defined as patients with International Neuroblastoma Staging System stage 4 disease 1 year old or older, stage 4 less than 1 year old with MYCN amplification, or stage 2,3 patients up to age 21 years with MYCN amplification. Patients underwent a rapid induction therapy, followed by peripheral stem cell harvest, local control with complete tumor resection, myeloablative therapy with peripheral stem cell transplant, local control with radiotherapy, and then ch14.18 anti-GD2 monoclonal immunotherapy with RA, with or without sc IL-2.

Inclusion criteria were a complete response or partial response with three or fewer skeletal metastatic spots and no positive bone marrow biopsies on two aspirates. Randomization occurred between day 60 and 90 post stem cell infusion. RA was given on days 1-14 post randomization. For the arm receiving IL-2, it was given as 5 daily injections of 6 x 106 IU/m2 per day over 8 hours on days 15-19. IL-2 was repeated on days 22-26. Both groups also received the ch14.18 antibody on days 22-26. All patients received high-dose morphine for pain management.

For event free survival (EFS), the primary endpoint of the trial, “if we look at 3 years, we see with antibody alone it’s 57%. With IL-2, it’s 60%. It’s completely clear that there’s no superiority for the IL-2 arm,” said Dr. Ladenstein, professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Cancer Research Institute, Austria.

At 5 years, the EFS was no different for the two treatment arms, at 51% for antibody alone and 56% for antibody plus IL-2 (P = .561). There were 199/200 patients in the antibody-alone arm with follow-up after randomization and 203/206 in the antibody plus IL-2 arm. The same was true for the secondary endpoint of overall survival, with 66% survival with antibody-alone and 58% in the antibody plus IL-2 at 5 years.

The EFS for patients with a complete response prior to immunotherapy was 66% at 3 years and was 50% for patients with less than a complete response, a significant difference (P = .003) in favor of those with a complete response. IL-2 administration had no effect on the EFS of the patients with a complete response if it was given with the immunotherapy. Similarly, IL-2 made no difference for patients who had had a very good partial response or a partial response prior to immunotherapy. For complete, very good partial, or partial responses prior to immunotherapy, the overall response to immunotherapy was 51%.

“However, feasibility is a concern, particularly in the IL-2 arm. Only 61% of the cycles were completed whereas it was 85% in the antibody-only arm, and the interruptions are definitely related mainly to the IL-2 component,” Dr. Ladenstein said.

Toxicity was higher for those patients receiving IL-2 compared to those getting antibody alone: Lansky performance status of 30% or less was 41% vs. 17%, early termination of therapy was 39% vs. 15%, and Common Terminology Criteria grade 3/4 fever was 41% vs. 14%, respectively (all P less than .001). There were also significantly more grade 3/4 allergic reactions and incidences of capillary leak, as well as diarrhea, hypotension, central nervous toxicity, and pain with IL-2.

The outcomes were favorable with antibody immunotherapy alone, but the higher toxicity with IL-2 shows that “a less toxic treatment schedule therefore is needed for this late treatment phase,” Dr. Ladenstein said.

Commenting on the trial, Dr. Barbara Hero of University Children’s Hospital in Cologne, Germany, asked whether cytokines are a useful part of the regimen “because we know the cytokines add quite a lot of toxicity to the regimens.” Even if they are potentially useful, researchers still do not know which cytokines, route of administration, and at what doses and timing would be best. Also, it is not known if a different induction regimen or antibody treatment could make a difference in using cytokines.

Another question is whether cytokines may be of benefit in patients with a higher tumor burden, e.g., more than three skeletal spots, used as the eligibility cut-off in this trial, Dr. Hero said.

CHICAGO – Adding the cytokine IL-2 to front-line therapy with the anti-GD2 antibody ch14.18/CHO provided no additional survival benefit and only added to toxicity in the treatment of pediatric patients with high-risk neuroblastoma (NB), Dr. Ruth Ladenstein reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

A form of the antibody (dinutuximab) is approved for use in combination with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, IL-2, and 13-cis-retinoic acid (RA) to treat high risk NB. A previous study (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324-34) showed that a combination of ch14.18 and the cytokines improved event free survival to 66% at 2 years, but the role of cytokines in this context remained unclear. Dr. Ladenstein and associates therefore performed a phase III trial that randomized patients to the antibody with or without subcutaneous (sc) IL-2.

High-risk NB was defined as patients with International Neuroblastoma Staging System stage 4 disease 1 year old or older, stage 4 less than 1 year old with MYCN amplification, or stage 2,3 patients up to age 21 years with MYCN amplification. Patients underwent a rapid induction therapy, followed by peripheral stem cell harvest, local control with complete tumor resection, myeloablative therapy with peripheral stem cell transplant, local control with radiotherapy, and then ch14.18 anti-GD2 monoclonal immunotherapy with RA, with or without sc IL-2.

Inclusion criteria were a complete response or partial response with three or fewer skeletal metastatic spots and no positive bone marrow biopsies on two aspirates. Randomization occurred between day 60 and 90 post stem cell infusion. RA was given on days 1-14 post randomization. For the arm receiving IL-2, it was given as 5 daily injections of 6 x 106 IU/m2 per day over 8 hours on days 15-19. IL-2 was repeated on days 22-26. Both groups also received the ch14.18 antibody on days 22-26. All patients received high-dose morphine for pain management.

For event free survival (EFS), the primary endpoint of the trial, “if we look at 3 years, we see with antibody alone it’s 57%. With IL-2, it’s 60%. It’s completely clear that there’s no superiority for the IL-2 arm,” said Dr. Ladenstein, professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Cancer Research Institute, Austria.

At 5 years, the EFS was no different for the two treatment arms, at 51% for antibody alone and 56% for antibody plus IL-2 (P = .561). There were 199/200 patients in the antibody-alone arm with follow-up after randomization and 203/206 in the antibody plus IL-2 arm. The same was true for the secondary endpoint of overall survival, with 66% survival with antibody-alone and 58% in the antibody plus IL-2 at 5 years.

The EFS for patients with a complete response prior to immunotherapy was 66% at 3 years and was 50% for patients with less than a complete response, a significant difference (P = .003) in favor of those with a complete response. IL-2 administration had no effect on the EFS of the patients with a complete response if it was given with the immunotherapy. Similarly, IL-2 made no difference for patients who had had a very good partial response or a partial response prior to immunotherapy. For complete, very good partial, or partial responses prior to immunotherapy, the overall response to immunotherapy was 51%.

“However, feasibility is a concern, particularly in the IL-2 arm. Only 61% of the cycles were completed whereas it was 85% in the antibody-only arm, and the interruptions are definitely related mainly to the IL-2 component,” Dr. Ladenstein said.

Toxicity was higher for those patients receiving IL-2 compared to those getting antibody alone: Lansky performance status of 30% or less was 41% vs. 17%, early termination of therapy was 39% vs. 15%, and Common Terminology Criteria grade 3/4 fever was 41% vs. 14%, respectively (all P less than .001). There were also significantly more grade 3/4 allergic reactions and incidences of capillary leak, as well as diarrhea, hypotension, central nervous toxicity, and pain with IL-2.

The outcomes were favorable with antibody immunotherapy alone, but the higher toxicity with IL-2 shows that “a less toxic treatment schedule therefore is needed for this late treatment phase,” Dr. Ladenstein said.

Commenting on the trial, Dr. Barbara Hero of University Children’s Hospital in Cologne, Germany, asked whether cytokines are a useful part of the regimen “because we know the cytokines add quite a lot of toxicity to the regimens.” Even if they are potentially useful, researchers still do not know which cytokines, route of administration, and at what doses and timing would be best. Also, it is not known if a different induction regimen or antibody treatment could make a difference in using cytokines.

Another question is whether cytokines may be of benefit in patients with a higher tumor burden, e.g., more than three skeletal spots, used as the eligibility cut-off in this trial, Dr. Hero said.

CHICAGO – Adding the cytokine IL-2 to front-line therapy with the anti-GD2 antibody ch14.18/CHO provided no additional survival benefit and only added to toxicity in the treatment of pediatric patients with high-risk neuroblastoma (NB), Dr. Ruth Ladenstein reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

A form of the antibody (dinutuximab) is approved for use in combination with granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, IL-2, and 13-cis-retinoic acid (RA) to treat high risk NB. A previous study (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324-34) showed that a combination of ch14.18 and the cytokines improved event free survival to 66% at 2 years, but the role of cytokines in this context remained unclear. Dr. Ladenstein and associates therefore performed a phase III trial that randomized patients to the antibody with or without subcutaneous (sc) IL-2.

High-risk NB was defined as patients with International Neuroblastoma Staging System stage 4 disease 1 year old or older, stage 4 less than 1 year old with MYCN amplification, or stage 2,3 patients up to age 21 years with MYCN amplification. Patients underwent a rapid induction therapy, followed by peripheral stem cell harvest, local control with complete tumor resection, myeloablative therapy with peripheral stem cell transplant, local control with radiotherapy, and then ch14.18 anti-GD2 monoclonal immunotherapy with RA, with or without sc IL-2.

Inclusion criteria were a complete response or partial response with three or fewer skeletal metastatic spots and no positive bone marrow biopsies on two aspirates. Randomization occurred between day 60 and 90 post stem cell infusion. RA was given on days 1-14 post randomization. For the arm receiving IL-2, it was given as 5 daily injections of 6 x 106 IU/m2 per day over 8 hours on days 15-19. IL-2 was repeated on days 22-26. Both groups also received the ch14.18 antibody on days 22-26. All patients received high-dose morphine for pain management.

For event free survival (EFS), the primary endpoint of the trial, “if we look at 3 years, we see with antibody alone it’s 57%. With IL-2, it’s 60%. It’s completely clear that there’s no superiority for the IL-2 arm,” said Dr. Ladenstein, professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Cancer Research Institute, Austria.

At 5 years, the EFS was no different for the two treatment arms, at 51% for antibody alone and 56% for antibody plus IL-2 (P = .561). There were 199/200 patients in the antibody-alone arm with follow-up after randomization and 203/206 in the antibody plus IL-2 arm. The same was true for the secondary endpoint of overall survival, with 66% survival with antibody-alone and 58% in the antibody plus IL-2 at 5 years.

The EFS for patients with a complete response prior to immunotherapy was 66% at 3 years and was 50% for patients with less than a complete response, a significant difference (P = .003) in favor of those with a complete response. IL-2 administration had no effect on the EFS of the patients with a complete response if it was given with the immunotherapy. Similarly, IL-2 made no difference for patients who had had a very good partial response or a partial response prior to immunotherapy. For complete, very good partial, or partial responses prior to immunotherapy, the overall response to immunotherapy was 51%.

“However, feasibility is a concern, particularly in the IL-2 arm. Only 61% of the cycles were completed whereas it was 85% in the antibody-only arm, and the interruptions are definitely related mainly to the IL-2 component,” Dr. Ladenstein said.

Toxicity was higher for those patients receiving IL-2 compared to those getting antibody alone: Lansky performance status of 30% or less was 41% vs. 17%, early termination of therapy was 39% vs. 15%, and Common Terminology Criteria grade 3/4 fever was 41% vs. 14%, respectively (all P less than .001). There were also significantly more grade 3/4 allergic reactions and incidences of capillary leak, as well as diarrhea, hypotension, central nervous toxicity, and pain with IL-2.

The outcomes were favorable with antibody immunotherapy alone, but the higher toxicity with IL-2 shows that “a less toxic treatment schedule therefore is needed for this late treatment phase,” Dr. Ladenstein said.

Commenting on the trial, Dr. Barbara Hero of University Children’s Hospital in Cologne, Germany, asked whether cytokines are a useful part of the regimen “because we know the cytokines add quite a lot of toxicity to the regimens.” Even if they are potentially useful, researchers still do not know which cytokines, route of administration, and at what doses and timing would be best. Also, it is not known if a different induction regimen or antibody treatment could make a difference in using cytokines.

Another question is whether cytokines may be of benefit in patients with a higher tumor burden, e.g., more than three skeletal spots, used as the eligibility cut-off in this trial, Dr. Hero said.

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: IL-2 adds no benefit, only toxicity, to neuroblastoma antibody therapy.

Major finding: Only 61% of treatment cycles were completed with IL-2.

Data source: Phase III, randomized, two-arm study of 402 pediatric/adolescent neuroblastoma patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Ladenstein has received honoraria and has had a consulting or advisory role with Apeiron Biologics and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has research funding from, patents with, has provided expert testimony for, and has received travel expenses from Apeiron. Dr. Hero had no disclosures.

Early results positive for treating high-grade gliomas with virus-based therapy

An investigational virus-based therapy was safely given to patients with high-grade or recurrent gliomas in a phase I study, improving survival for some, investigators report.

In the phase I trial of Toca 511 (vocimagene amiretrorepvec) in combination with surgical resection, median overall survival was 13.6 months (95% confidence interval, 10.8-20.0) among all evaluable patients with high-grade glioblastoma (n = 43) and 14.4 months (95% CI, 11.3-32.3) for patients with first or second recurrence (n = 32), Dr. Timothy Cloughesy of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his associates reported (Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:1-11).

Investigators compared their data to those of external controls with glioblastoma at first and second recurrence treated with lomustine and saw an almost twofold improvement in overall survival (13.6 months vs. 7.1 months (hazard ratio, 0.45; P = .003).

Toca 511 dispatches a virus to rapidly dividing cancer cells, then delivers a gene encoding an enzyme that converts a nontoxic prodrug, Toca FC (extended-release 5-fluorocytosine), into its active form, 5-fluorouracil.

There were no treatment-related deaths, and there were fewer grade 3 adverse events, compared with the external lomustine control group.

“Recurrent HGG [high-grade glioblastoma] is associated with dismal clinical outcomes, and patients are in need of safe and more efficacious therapy. The nonlytic RRV [retroviral replicating vector] Toca 511 and an extended-release 5-FC [5-fluorocytosine] have the potential to fill this medical need,” the researchers said.

A randomized phase II/III trial in patients with recurrent glioblastoma and anaplastic astrocytoma is underway, they said.