User login

Economic burden of migraine increases with the number of treatment failures

, researchers wrote. Utilization of health care resources and associated costs are greater among patients with three or more treatment failures, compared with patients with fewer treatment failures. This research was presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

Migraine entails a significant economic burden, including direct costs (e.g., medical costs) and indirect costs (e.g., lost productivity). Information about the burden associated with failed preventive treatments among migraineurs is limited, however. Lawrence C. Newman, MD, director of the division of headache at NYU Langone Health in New York, and colleagues conducted a study to characterize health care resource utilization (HCRU) and its associated costs among migraineurs, stratified by the number of preventive treatment failures.

About one quarter of patients had two treatment failures

Using data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental database, Dr. Newman and colleagues identified patients who received a new diagnosis of migraine between Jan. 1, 2011, and June 30, 2015. Next, they identified the number of treatment failures during the 2 years following the initial migraine diagnosis. They assessed HCRU and associated costs during the 12 months following an index event. The index was the date of initiation of the second preventive treatment for patients with one treatment failure, the date of initiation of the third treatment for patients with two treatment failures, and the date of initiation of the fourth treatment for patients with three or more treatment failures.

Dr. Newman’s group identified 44,181 patients with incident migraine who had failed preventive treatments. Of this population, 27,112 patients (61.4%) had one treatment failure, 10,583 (24%) had two treatment failures, and 6,486 (14.7%) had three or more treatment failures.

The total medical cost per patient, including emergency room (ER), inpatient (IP), and outpatient (OP) care, increased with increasing number of treatment failures ($10,329 for one, $13,774 for two, and $35,392 for three or more). When the investigators added prescription drug costs, the total health care costs also increased with number of treatment failures ($13,946 for one, $18,685 for two, and $41,864 for three or more).

Similarly, the per-patient annual health care provider visits increased with increasing numbers of treatment failures. The number of ER visits per year was 0.54, 0.69, and 1.02 for patients with one, two, and three or more treatment failures, respectively. The annual number of IP visits was 0.46, 0.59, and 0.97, for patients with one, two, and three or more treatment failures, respectively. OP visits showed a similar trend. The annual number of office visits was 9.47 for patients with one, 11.24 for patients with two, and 14.26 for patients with three or more treatment failures. The annual number of other visits was 13.15 for patients with one, 15.73 for patients with two, and 19.96 for patients with three or more treatment failures.

Guidelines could enable appropriate treatment

Reasons for treatment failure include misdiagnosis of the headache disorder, failure to identify and account for comorbidities, overlooking concurrent acute medication overuse, and inappropriate dose or formulation, said Dr. Newman. “Common pitfalls in prevention that lead to treatment failure include not using evidence-based treatments, starting at too low of a dose and not increasing, starting too high or increasing the dose too quickly, discontinuing the medication before an effect can be seen (before 8 weeks), patient nonadherence, and not establishing realistic expectations.”

Available resources could help clinicians treat migraine effectively. “The American Headache Society (AHS)/AAN preventive guidelines have been retired, yet they offered several levels of effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments that were evidence-based,” said Dr. Newman. “Furthermore, in 2019, the AHS published a consensus statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. This statement offered advice about the new anti-CGRP agents, onabotulinum toxin, and neuromodulation devices. I think this is a good starting point for neurologists to be familiar with to choose appropriate therapeutic options for people living with migraine.”

Earlier treatment may reduce patients’ economic burden

The study’s weaknesses included its observational design and its reliance on diagnostic codes, which raised the possibility that comorbidities were inadequately recognized, said Dr. Newman. The reasons that patients changed medications are unknown, and the results are not generalizable to patients aged 65 years or older, he added.

Major strengths of Dr. Newman’s study are its large sample size and wealth of available data, said Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The multiple subcategories suggest that this was a carefully organized and implemented study,” he added. If any diagnoses of migraine were provided by general practitioners with little knowledge of migraine, this would weaken the study, said Dr. Rapoport, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews.

“We can ease the economic burden of migraineurs by improving acute care therapy with better selection and earlier starting of effective preventive therapy,” he continued. “Going for migraine-specific acute care therapy is better than pain medications or other nonspecific therapies. If you do not stop a migraine attack with effective therapy, you increase the odds that the patient will go on to chronic migraine. It is always important to effectively teach doctors and nurses to improve their diagnostic skills and use the optimal acute and preventive therapy.” For their next trial, maximizing an accurate diagnosis and performing a prospective study measuring treatment outcomes will be particularly valuable, Dr. Rapoport concluded.

Dr. Newman’s study was supported by Novartis Pharma in Basel, Switzerland. Together with Amgen, Novartis developed erenumab. Dr. Newman has received compensation from Allergan, Alder, Amgen, Biohaven, Novartis, Teva, Supernus, and Theranica for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities. He has received compensation from Springer Scientific for editorial services.

SOURCE: Newman L et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S47.009.

, researchers wrote. Utilization of health care resources and associated costs are greater among patients with three or more treatment failures, compared with patients with fewer treatment failures. This research was presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

Migraine entails a significant economic burden, including direct costs (e.g., medical costs) and indirect costs (e.g., lost productivity). Information about the burden associated with failed preventive treatments among migraineurs is limited, however. Lawrence C. Newman, MD, director of the division of headache at NYU Langone Health in New York, and colleagues conducted a study to characterize health care resource utilization (HCRU) and its associated costs among migraineurs, stratified by the number of preventive treatment failures.

About one quarter of patients had two treatment failures

Using data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental database, Dr. Newman and colleagues identified patients who received a new diagnosis of migraine between Jan. 1, 2011, and June 30, 2015. Next, they identified the number of treatment failures during the 2 years following the initial migraine diagnosis. They assessed HCRU and associated costs during the 12 months following an index event. The index was the date of initiation of the second preventive treatment for patients with one treatment failure, the date of initiation of the third treatment for patients with two treatment failures, and the date of initiation of the fourth treatment for patients with three or more treatment failures.

Dr. Newman’s group identified 44,181 patients with incident migraine who had failed preventive treatments. Of this population, 27,112 patients (61.4%) had one treatment failure, 10,583 (24%) had two treatment failures, and 6,486 (14.7%) had three or more treatment failures.

The total medical cost per patient, including emergency room (ER), inpatient (IP), and outpatient (OP) care, increased with increasing number of treatment failures ($10,329 for one, $13,774 for two, and $35,392 for three or more). When the investigators added prescription drug costs, the total health care costs also increased with number of treatment failures ($13,946 for one, $18,685 for two, and $41,864 for three or more).

Similarly, the per-patient annual health care provider visits increased with increasing numbers of treatment failures. The number of ER visits per year was 0.54, 0.69, and 1.02 for patients with one, two, and three or more treatment failures, respectively. The annual number of IP visits was 0.46, 0.59, and 0.97, for patients with one, two, and three or more treatment failures, respectively. OP visits showed a similar trend. The annual number of office visits was 9.47 for patients with one, 11.24 for patients with two, and 14.26 for patients with three or more treatment failures. The annual number of other visits was 13.15 for patients with one, 15.73 for patients with two, and 19.96 for patients with three or more treatment failures.

Guidelines could enable appropriate treatment

Reasons for treatment failure include misdiagnosis of the headache disorder, failure to identify and account for comorbidities, overlooking concurrent acute medication overuse, and inappropriate dose or formulation, said Dr. Newman. “Common pitfalls in prevention that lead to treatment failure include not using evidence-based treatments, starting at too low of a dose and not increasing, starting too high or increasing the dose too quickly, discontinuing the medication before an effect can be seen (before 8 weeks), patient nonadherence, and not establishing realistic expectations.”

Available resources could help clinicians treat migraine effectively. “The American Headache Society (AHS)/AAN preventive guidelines have been retired, yet they offered several levels of effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments that were evidence-based,” said Dr. Newman. “Furthermore, in 2019, the AHS published a consensus statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. This statement offered advice about the new anti-CGRP agents, onabotulinum toxin, and neuromodulation devices. I think this is a good starting point for neurologists to be familiar with to choose appropriate therapeutic options for people living with migraine.”

Earlier treatment may reduce patients’ economic burden

The study’s weaknesses included its observational design and its reliance on diagnostic codes, which raised the possibility that comorbidities were inadequately recognized, said Dr. Newman. The reasons that patients changed medications are unknown, and the results are not generalizable to patients aged 65 years or older, he added.

Major strengths of Dr. Newman’s study are its large sample size and wealth of available data, said Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The multiple subcategories suggest that this was a carefully organized and implemented study,” he added. If any diagnoses of migraine were provided by general practitioners with little knowledge of migraine, this would weaken the study, said Dr. Rapoport, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews.

“We can ease the economic burden of migraineurs by improving acute care therapy with better selection and earlier starting of effective preventive therapy,” he continued. “Going for migraine-specific acute care therapy is better than pain medications or other nonspecific therapies. If you do not stop a migraine attack with effective therapy, you increase the odds that the patient will go on to chronic migraine. It is always important to effectively teach doctors and nurses to improve their diagnostic skills and use the optimal acute and preventive therapy.” For their next trial, maximizing an accurate diagnosis and performing a prospective study measuring treatment outcomes will be particularly valuable, Dr. Rapoport concluded.

Dr. Newman’s study was supported by Novartis Pharma in Basel, Switzerland. Together with Amgen, Novartis developed erenumab. Dr. Newman has received compensation from Allergan, Alder, Amgen, Biohaven, Novartis, Teva, Supernus, and Theranica for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities. He has received compensation from Springer Scientific for editorial services.

SOURCE: Newman L et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S47.009.

, researchers wrote. Utilization of health care resources and associated costs are greater among patients with three or more treatment failures, compared with patients with fewer treatment failures. This research was presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

Migraine entails a significant economic burden, including direct costs (e.g., medical costs) and indirect costs (e.g., lost productivity). Information about the burden associated with failed preventive treatments among migraineurs is limited, however. Lawrence C. Newman, MD, director of the division of headache at NYU Langone Health in New York, and colleagues conducted a study to characterize health care resource utilization (HCRU) and its associated costs among migraineurs, stratified by the number of preventive treatment failures.

About one quarter of patients had two treatment failures

Using data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental database, Dr. Newman and colleagues identified patients who received a new diagnosis of migraine between Jan. 1, 2011, and June 30, 2015. Next, they identified the number of treatment failures during the 2 years following the initial migraine diagnosis. They assessed HCRU and associated costs during the 12 months following an index event. The index was the date of initiation of the second preventive treatment for patients with one treatment failure, the date of initiation of the third treatment for patients with two treatment failures, and the date of initiation of the fourth treatment for patients with three or more treatment failures.

Dr. Newman’s group identified 44,181 patients with incident migraine who had failed preventive treatments. Of this population, 27,112 patients (61.4%) had one treatment failure, 10,583 (24%) had two treatment failures, and 6,486 (14.7%) had three or more treatment failures.

The total medical cost per patient, including emergency room (ER), inpatient (IP), and outpatient (OP) care, increased with increasing number of treatment failures ($10,329 for one, $13,774 for two, and $35,392 for three or more). When the investigators added prescription drug costs, the total health care costs also increased with number of treatment failures ($13,946 for one, $18,685 for two, and $41,864 for three or more).

Similarly, the per-patient annual health care provider visits increased with increasing numbers of treatment failures. The number of ER visits per year was 0.54, 0.69, and 1.02 for patients with one, two, and three or more treatment failures, respectively. The annual number of IP visits was 0.46, 0.59, and 0.97, for patients with one, two, and three or more treatment failures, respectively. OP visits showed a similar trend. The annual number of office visits was 9.47 for patients with one, 11.24 for patients with two, and 14.26 for patients with three or more treatment failures. The annual number of other visits was 13.15 for patients with one, 15.73 for patients with two, and 19.96 for patients with three or more treatment failures.

Guidelines could enable appropriate treatment

Reasons for treatment failure include misdiagnosis of the headache disorder, failure to identify and account for comorbidities, overlooking concurrent acute medication overuse, and inappropriate dose or formulation, said Dr. Newman. “Common pitfalls in prevention that lead to treatment failure include not using evidence-based treatments, starting at too low of a dose and not increasing, starting too high or increasing the dose too quickly, discontinuing the medication before an effect can be seen (before 8 weeks), patient nonadherence, and not establishing realistic expectations.”

Available resources could help clinicians treat migraine effectively. “The American Headache Society (AHS)/AAN preventive guidelines have been retired, yet they offered several levels of effectiveness of pharmacologic treatments that were evidence-based,” said Dr. Newman. “Furthermore, in 2019, the AHS published a consensus statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. This statement offered advice about the new anti-CGRP agents, onabotulinum toxin, and neuromodulation devices. I think this is a good starting point for neurologists to be familiar with to choose appropriate therapeutic options for people living with migraine.”

Earlier treatment may reduce patients’ economic burden

The study’s weaknesses included its observational design and its reliance on diagnostic codes, which raised the possibility that comorbidities were inadequately recognized, said Dr. Newman. The reasons that patients changed medications are unknown, and the results are not generalizable to patients aged 65 years or older, he added.

Major strengths of Dr. Newman’s study are its large sample size and wealth of available data, said Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The multiple subcategories suggest that this was a carefully organized and implemented study,” he added. If any diagnoses of migraine were provided by general practitioners with little knowledge of migraine, this would weaken the study, said Dr. Rapoport, editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews.

“We can ease the economic burden of migraineurs by improving acute care therapy with better selection and earlier starting of effective preventive therapy,” he continued. “Going for migraine-specific acute care therapy is better than pain medications or other nonspecific therapies. If you do not stop a migraine attack with effective therapy, you increase the odds that the patient will go on to chronic migraine. It is always important to effectively teach doctors and nurses to improve their diagnostic skills and use the optimal acute and preventive therapy.” For their next trial, maximizing an accurate diagnosis and performing a prospective study measuring treatment outcomes will be particularly valuable, Dr. Rapoport concluded.

Dr. Newman’s study was supported by Novartis Pharma in Basel, Switzerland. Together with Amgen, Novartis developed erenumab. Dr. Newman has received compensation from Allergan, Alder, Amgen, Biohaven, Novartis, Teva, Supernus, and Theranica for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities. He has received compensation from Springer Scientific for editorial services.

SOURCE: Newman L et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S47.009.

From AAN 2020

Predictors of ICH after thrombectomy identified

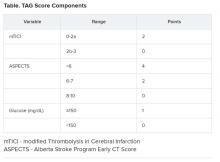

(ICH), new research suggests. In a study of nearly 600 patients undergoing thrombectomy, investigators combined a modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score, an Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS), and glucose levels (the “TAG score”) to predict risk. Results showed that each unit increase in the combination score was associated with a significant, nearly twofold greater likelihood of symptomatic ICH.

“It is very easy” to calculate the new score in a clinical setting, lead author Mayra Johana Montalvo Perero, MD, Department of Neurology, Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, said. “You just need three variables.”

The findings were presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

Limited data

High TAG scores are associated with symptomatic ICH in patients receiving mechanical thrombectomy, Dr. Montalvo Perero and colleagues said.

Although clinical predictors of symptomatic ICH are well established, “there is limited data in patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy,” the researchers noted.

To learn more, they assessed 578 patients (52% women; mean age, 73 years) who had mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke at a comprehensive stroke center. Within this cohort, 19 patients (3.3%) developed symptomatic ICH.

The investigators compared clinical and radiographic findings between patients who experienced symptomatic ICH and those who did not.

The TICI score emerged as a predictor when each unit decrease in this score was associated with greater risk for symptomatic ICH (odds ratio, 5.13; 95% confidence interval, 1.84-14.29; P = .002).

Each one-point decrease in the ASPECTS score also predicted increased risk (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0; P = .003).

“The main driver is the size of the stroke core, which is correlated with the ASPECTS score,” Dr. Montalvo Perero said.

Each 10 mg/dL increase in glucose level also correlated with increased risk (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01-1.13; P = .018).

Twice the risk

The investigators then combined these three independent variables into a weighted TAG score based on a multivariate analysis. Each unit increase in this composite score was associated with increased risk of symptomatic ICH (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.48-2.66; P < .001).

There was no association between patients who received tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and risk of symptomatic ICH, which Dr. Montalvo Perero said was surprising.

However, “that may be due to a small number” of patients with symptomatic ICH included in the study, she said. “Therefore, that would be an interesting question to ask in future studies with bigger cohorts.”

Larger studies are also needed to validate this scoring system and to test strategies to reduce risk of symptomatic ICH and make thrombectomy safer in patients with elevated TAG scores, Dr. Montalvo Perero said.

A step in the right direction?

Commenting on the study, Jeremy Payne, MD, PhD, director of the Stroke Center at Banner Health’s University Medicine Neuroscience Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, noted the importance of predicting which patients might have secondary bleeding after interventional treatment of a large vessel occlusion stroke

“In aggregate, the role of endovascular thrombectomy is quite clear, but we still struggle to predict at the individual patient level who will benefit,” said Dr. Payne, who was not involved with the research.

Transfer and treatment of these patients also carries an economic cost. “Just getting patients to our center, where about 80% of the complex stroke patients come by helicopter, costs upwards of $30,000,” Dr. Payne said. “The financial argument isn’t one we like to talk much about, but we’re committing to spending probably $100,000-$200,000 on each person’s care.”

This study “attempts to address an important issue,” he said.

Predicting who is more likely to benefit leads to the assumption that if that were to happen, “we could skip all the rigamarole of helicopters and procedures, avoid the extra expense and particularly not make things worse than they already are,” explained Dr. Payne.

Potential limitations include that this is a single-center study and is based on an analysis of 19 patients out of 578. As a result, it is not clear that these findings will necessarily be generalizable to other centers, said Dr. Payne.

The TICI and ASPECTS “are pretty obvious markers of risk,” he noted. “The glucose levels, however, are more subtly interesting.”

He also pointed out that an association between diabetes and worse stroke outcomes is well established.

“The mechanisms are poorly understood, but the role of glucose keeps popping up as a potential marker of risk, and so it’s interesting that it bubbles up in their work too,” Dr. Payne said.

Furthermore, unlike TICI and ASPECTS, glucose levels are modifiable.

“Overall, then, we will continue to study this,” Dr. Payne said. “It’s very important to refine our ability to predict which patients may receive benefit versus harm from such procedures, and this is a step in the right direction.”

Some findings were also published December 2019 in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Montalvo Perero and Payne have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SOURCE: Motalvo Perero MJ et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S20.001.

(ICH), new research suggests. In a study of nearly 600 patients undergoing thrombectomy, investigators combined a modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score, an Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS), and glucose levels (the “TAG score”) to predict risk. Results showed that each unit increase in the combination score was associated with a significant, nearly twofold greater likelihood of symptomatic ICH.

“It is very easy” to calculate the new score in a clinical setting, lead author Mayra Johana Montalvo Perero, MD, Department of Neurology, Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, said. “You just need three variables.”

The findings were presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

Limited data

High TAG scores are associated with symptomatic ICH in patients receiving mechanical thrombectomy, Dr. Montalvo Perero and colleagues said.

Although clinical predictors of symptomatic ICH are well established, “there is limited data in patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy,” the researchers noted.

To learn more, they assessed 578 patients (52% women; mean age, 73 years) who had mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke at a comprehensive stroke center. Within this cohort, 19 patients (3.3%) developed symptomatic ICH.

The investigators compared clinical and radiographic findings between patients who experienced symptomatic ICH and those who did not.

The TICI score emerged as a predictor when each unit decrease in this score was associated with greater risk for symptomatic ICH (odds ratio, 5.13; 95% confidence interval, 1.84-14.29; P = .002).

Each one-point decrease in the ASPECTS score also predicted increased risk (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0; P = .003).

“The main driver is the size of the stroke core, which is correlated with the ASPECTS score,” Dr. Montalvo Perero said.

Each 10 mg/dL increase in glucose level also correlated with increased risk (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01-1.13; P = .018).

Twice the risk

The investigators then combined these three independent variables into a weighted TAG score based on a multivariate analysis. Each unit increase in this composite score was associated with increased risk of symptomatic ICH (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.48-2.66; P < .001).

There was no association between patients who received tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and risk of symptomatic ICH, which Dr. Montalvo Perero said was surprising.

However, “that may be due to a small number” of patients with symptomatic ICH included in the study, she said. “Therefore, that would be an interesting question to ask in future studies with bigger cohorts.”

Larger studies are also needed to validate this scoring system and to test strategies to reduce risk of symptomatic ICH and make thrombectomy safer in patients with elevated TAG scores, Dr. Montalvo Perero said.

A step in the right direction?

Commenting on the study, Jeremy Payne, MD, PhD, director of the Stroke Center at Banner Health’s University Medicine Neuroscience Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, noted the importance of predicting which patients might have secondary bleeding after interventional treatment of a large vessel occlusion stroke

“In aggregate, the role of endovascular thrombectomy is quite clear, but we still struggle to predict at the individual patient level who will benefit,” said Dr. Payne, who was not involved with the research.

Transfer and treatment of these patients also carries an economic cost. “Just getting patients to our center, where about 80% of the complex stroke patients come by helicopter, costs upwards of $30,000,” Dr. Payne said. “The financial argument isn’t one we like to talk much about, but we’re committing to spending probably $100,000-$200,000 on each person’s care.”

This study “attempts to address an important issue,” he said.

Predicting who is more likely to benefit leads to the assumption that if that were to happen, “we could skip all the rigamarole of helicopters and procedures, avoid the extra expense and particularly not make things worse than they already are,” explained Dr. Payne.

Potential limitations include that this is a single-center study and is based on an analysis of 19 patients out of 578. As a result, it is not clear that these findings will necessarily be generalizable to other centers, said Dr. Payne.

The TICI and ASPECTS “are pretty obvious markers of risk,” he noted. “The glucose levels, however, are more subtly interesting.”

He also pointed out that an association between diabetes and worse stroke outcomes is well established.

“The mechanisms are poorly understood, but the role of glucose keeps popping up as a potential marker of risk, and so it’s interesting that it bubbles up in their work too,” Dr. Payne said.

Furthermore, unlike TICI and ASPECTS, glucose levels are modifiable.

“Overall, then, we will continue to study this,” Dr. Payne said. “It’s very important to refine our ability to predict which patients may receive benefit versus harm from such procedures, and this is a step in the right direction.”

Some findings were also published December 2019 in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Montalvo Perero and Payne have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SOURCE: Motalvo Perero MJ et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S20.001.

(ICH), new research suggests. In a study of nearly 600 patients undergoing thrombectomy, investigators combined a modified Thrombolysis in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) score, an Alberta Stroke Program Early Computed Tomography Score (ASPECTS), and glucose levels (the “TAG score”) to predict risk. Results showed that each unit increase in the combination score was associated with a significant, nearly twofold greater likelihood of symptomatic ICH.

“It is very easy” to calculate the new score in a clinical setting, lead author Mayra Johana Montalvo Perero, MD, Department of Neurology, Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, said. “You just need three variables.”

The findings were presented online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

Limited data

High TAG scores are associated with symptomatic ICH in patients receiving mechanical thrombectomy, Dr. Montalvo Perero and colleagues said.

Although clinical predictors of symptomatic ICH are well established, “there is limited data in patients who underwent mechanical thrombectomy,” the researchers noted.

To learn more, they assessed 578 patients (52% women; mean age, 73 years) who had mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke at a comprehensive stroke center. Within this cohort, 19 patients (3.3%) developed symptomatic ICH.

The investigators compared clinical and radiographic findings between patients who experienced symptomatic ICH and those who did not.

The TICI score emerged as a predictor when each unit decrease in this score was associated with greater risk for symptomatic ICH (odds ratio, 5.13; 95% confidence interval, 1.84-14.29; P = .002).

Each one-point decrease in the ASPECTS score also predicted increased risk (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0; P = .003).

“The main driver is the size of the stroke core, which is correlated with the ASPECTS score,” Dr. Montalvo Perero said.

Each 10 mg/dL increase in glucose level also correlated with increased risk (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01-1.13; P = .018).

Twice the risk

The investigators then combined these three independent variables into a weighted TAG score based on a multivariate analysis. Each unit increase in this composite score was associated with increased risk of symptomatic ICH (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.48-2.66; P < .001).

There was no association between patients who received tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and risk of symptomatic ICH, which Dr. Montalvo Perero said was surprising.

However, “that may be due to a small number” of patients with symptomatic ICH included in the study, she said. “Therefore, that would be an interesting question to ask in future studies with bigger cohorts.”

Larger studies are also needed to validate this scoring system and to test strategies to reduce risk of symptomatic ICH and make thrombectomy safer in patients with elevated TAG scores, Dr. Montalvo Perero said.

A step in the right direction?

Commenting on the study, Jeremy Payne, MD, PhD, director of the Stroke Center at Banner Health’s University Medicine Neuroscience Institute in Phoenix, Arizona, noted the importance of predicting which patients might have secondary bleeding after interventional treatment of a large vessel occlusion stroke

“In aggregate, the role of endovascular thrombectomy is quite clear, but we still struggle to predict at the individual patient level who will benefit,” said Dr. Payne, who was not involved with the research.

Transfer and treatment of these patients also carries an economic cost. “Just getting patients to our center, where about 80% of the complex stroke patients come by helicopter, costs upwards of $30,000,” Dr. Payne said. “The financial argument isn’t one we like to talk much about, but we’re committing to spending probably $100,000-$200,000 on each person’s care.”

This study “attempts to address an important issue,” he said.

Predicting who is more likely to benefit leads to the assumption that if that were to happen, “we could skip all the rigamarole of helicopters and procedures, avoid the extra expense and particularly not make things worse than they already are,” explained Dr. Payne.

Potential limitations include that this is a single-center study and is based on an analysis of 19 patients out of 578. As a result, it is not clear that these findings will necessarily be generalizable to other centers, said Dr. Payne.

The TICI and ASPECTS “are pretty obvious markers of risk,” he noted. “The glucose levels, however, are more subtly interesting.”

He also pointed out that an association between diabetes and worse stroke outcomes is well established.

“The mechanisms are poorly understood, but the role of glucose keeps popping up as a potential marker of risk, and so it’s interesting that it bubbles up in their work too,” Dr. Payne said.

Furthermore, unlike TICI and ASPECTS, glucose levels are modifiable.

“Overall, then, we will continue to study this,” Dr. Payne said. “It’s very important to refine our ability to predict which patients may receive benefit versus harm from such procedures, and this is a step in the right direction.”

Some findings were also published December 2019 in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Montalvo Perero and Payne have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SOURCE: Motalvo Perero MJ et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S20.001.

AAN 2020

CGRP inhibitors receive reassuring real-world safety report

Stephen D. Silberstein, MD, reported online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

He presented a retrospective analysis of spontaneous postmarketing reports to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) for Aimovig (erenumab-aooe), Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm), and Emgality (galcanezumab-gnlm).

The top-10 lists of adverse events for all three monoclonal antibodies targeting CGRP were skewed heavily towards injection-site reactions, such as injection-site pain, itching, swelling, and erythema. The rates were relatively low. For example, injection-site pain was reported at a rate of 2.94 cases per 1,000 patients exposed to erenumab, 0.8/1,000 for fremanezumab, and 4.9/1,000 for galcanezumab, according to Dr. Silberstein, professor of neurology and director of the headache center at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia.

Migraine, headache, and drug ineffectiveness were in the top 10 for all three medications, as is typical in FAERS reports, since no drug is effective in everyone. These events were reported at rates of 1-5/1,000 exposed patients. Constipation was reported in association with the use of erenumab at a rate of 4.9 cases/1,000 patients, but did not reach the top-10 lists for the other two CGRP antagonists.

Notably, cardiovascular events were not among the top-10 adverse events reported for any of the novel preventive agents.

“These results will be practice changing, since some physicians have been holding back from prescribing these drugs pending the results of this sort of longer-term safety data,” Dr. Silberstein predicted in an interview.

Asked to comment on the FAERS study, neurologist Holly Yancy, DO, said that she found the findings unsurprising because the adverse effects were essentially as expected based upon the earlier favorable clinical trials experience.

“These medications are living up to the expectations for good tolerability that were in place when they were initially approved by the FDA just under 2 years ago,” said Dr. Yancy, a headache specialist at the Banner–University Medicine Neuroscience Institute in Phoenix.

“Injection-site reactions were anticipated. Clinically, I’ve found that if the medications reduce migraine days and severity, patients find the risk of temporary pain, redness, or itching at the injection site is an easy trade off,” she added.

CGRP is a vasoactive peptide. There has been a theoretic concern that its pharmacologic inhibition for prevention of migraine could lead to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, especially in individuals with coronary disease or a history of stroke. The absence of any such signal during the first 6 months of widespread clinical use of the CGRP inhibitors is highly encouraging, although this is an issue that warrants longer-term study, Dr. Yancy continued.

These drugs, which were expressly designed for migraine prevention, are a considerable advance over what was previously available in her view. They’re equally or more effective and considerably better tolerated than the preventive medications physicians had long been using off label, including antidepressants, antiepileptics, and cardiac drugs.

Dr. Silberstein reported financial relationships with close to two dozen pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Yancy reported serving on speakers’ bureaus for Amgen and Novartis.

SOURCE: Silverstein SD et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S58.008.

Stephen D. Silberstein, MD, reported online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

He presented a retrospective analysis of spontaneous postmarketing reports to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) for Aimovig (erenumab-aooe), Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm), and Emgality (galcanezumab-gnlm).

The top-10 lists of adverse events for all three monoclonal antibodies targeting CGRP were skewed heavily towards injection-site reactions, such as injection-site pain, itching, swelling, and erythema. The rates were relatively low. For example, injection-site pain was reported at a rate of 2.94 cases per 1,000 patients exposed to erenumab, 0.8/1,000 for fremanezumab, and 4.9/1,000 for galcanezumab, according to Dr. Silberstein, professor of neurology and director of the headache center at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia.

Migraine, headache, and drug ineffectiveness were in the top 10 for all three medications, as is typical in FAERS reports, since no drug is effective in everyone. These events were reported at rates of 1-5/1,000 exposed patients. Constipation was reported in association with the use of erenumab at a rate of 4.9 cases/1,000 patients, but did not reach the top-10 lists for the other two CGRP antagonists.

Notably, cardiovascular events were not among the top-10 adverse events reported for any of the novel preventive agents.

“These results will be practice changing, since some physicians have been holding back from prescribing these drugs pending the results of this sort of longer-term safety data,” Dr. Silberstein predicted in an interview.

Asked to comment on the FAERS study, neurologist Holly Yancy, DO, said that she found the findings unsurprising because the adverse effects were essentially as expected based upon the earlier favorable clinical trials experience.

“These medications are living up to the expectations for good tolerability that were in place when they were initially approved by the FDA just under 2 years ago,” said Dr. Yancy, a headache specialist at the Banner–University Medicine Neuroscience Institute in Phoenix.

“Injection-site reactions were anticipated. Clinically, I’ve found that if the medications reduce migraine days and severity, patients find the risk of temporary pain, redness, or itching at the injection site is an easy trade off,” she added.

CGRP is a vasoactive peptide. There has been a theoretic concern that its pharmacologic inhibition for prevention of migraine could lead to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, especially in individuals with coronary disease or a history of stroke. The absence of any such signal during the first 6 months of widespread clinical use of the CGRP inhibitors is highly encouraging, although this is an issue that warrants longer-term study, Dr. Yancy continued.

These drugs, which were expressly designed for migraine prevention, are a considerable advance over what was previously available in her view. They’re equally or more effective and considerably better tolerated than the preventive medications physicians had long been using off label, including antidepressants, antiepileptics, and cardiac drugs.

Dr. Silberstein reported financial relationships with close to two dozen pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Yancy reported serving on speakers’ bureaus for Amgen and Novartis.

SOURCE: Silverstein SD et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S58.008.

Stephen D. Silberstein, MD, reported online as part of the 2020 American Academy of Neurology Science Highlights.

He presented a retrospective analysis of spontaneous postmarketing reports to the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) for Aimovig (erenumab-aooe), Ajovy (fremanezumab-vfrm), and Emgality (galcanezumab-gnlm).

The top-10 lists of adverse events for all three monoclonal antibodies targeting CGRP were skewed heavily towards injection-site reactions, such as injection-site pain, itching, swelling, and erythema. The rates were relatively low. For example, injection-site pain was reported at a rate of 2.94 cases per 1,000 patients exposed to erenumab, 0.8/1,000 for fremanezumab, and 4.9/1,000 for galcanezumab, according to Dr. Silberstein, professor of neurology and director of the headache center at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia.

Migraine, headache, and drug ineffectiveness were in the top 10 for all three medications, as is typical in FAERS reports, since no drug is effective in everyone. These events were reported at rates of 1-5/1,000 exposed patients. Constipation was reported in association with the use of erenumab at a rate of 4.9 cases/1,000 patients, but did not reach the top-10 lists for the other two CGRP antagonists.

Notably, cardiovascular events were not among the top-10 adverse events reported for any of the novel preventive agents.

“These results will be practice changing, since some physicians have been holding back from prescribing these drugs pending the results of this sort of longer-term safety data,” Dr. Silberstein predicted in an interview.

Asked to comment on the FAERS study, neurologist Holly Yancy, DO, said that she found the findings unsurprising because the adverse effects were essentially as expected based upon the earlier favorable clinical trials experience.

“These medications are living up to the expectations for good tolerability that were in place when they were initially approved by the FDA just under 2 years ago,” said Dr. Yancy, a headache specialist at the Banner–University Medicine Neuroscience Institute in Phoenix.

“Injection-site reactions were anticipated. Clinically, I’ve found that if the medications reduce migraine days and severity, patients find the risk of temporary pain, redness, or itching at the injection site is an easy trade off,” she added.

CGRP is a vasoactive peptide. There has been a theoretic concern that its pharmacologic inhibition for prevention of migraine could lead to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, especially in individuals with coronary disease or a history of stroke. The absence of any such signal during the first 6 months of widespread clinical use of the CGRP inhibitors is highly encouraging, although this is an issue that warrants longer-term study, Dr. Yancy continued.

These drugs, which were expressly designed for migraine prevention, are a considerable advance over what was previously available in her view. They’re equally or more effective and considerably better tolerated than the preventive medications physicians had long been using off label, including antidepressants, antiepileptics, and cardiac drugs.

Dr. Silberstein reported financial relationships with close to two dozen pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Yancy reported serving on speakers’ bureaus for Amgen and Novartis.

SOURCE: Silverstein SD et al. AAN 2020, Abstract S58.008.

FROM AAN 2020

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis or primary psychiatric disorder?

New insights and ‘red flags’ provide clues to diagnosis

It remains difficult to distinguish anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis from a primary psychiatric disorder, but recent studies have identified clinical features and proposed screening criteria that could make it easier to identify these patients who would benefit from immunotherapy, according to an expert in the neurologic disease.

Most patients with confirmed anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis will experience substantial improvement after treatment with immunotherapy and other modalities, said Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, professor at the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Barcelona and adjunct professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In our experience, being aggressive with immune therapy ... the patients do quite well, which means that basically 85%-90% of the patients substantially improved over the next few months,” Dr. Dalmau said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

Identified for the first time a little more than a decade ago, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is a rare, immune-mediated disease that is usually found in children and young adults and is more common among women. It is frequently associated with ovarian tumors and teratomas, said Dr. Dalmau, and in about 90% of cases, patients will have prominent psychiatric and behavioral symptoms.

Patients develop IgG antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the NMDA receptor. These autoantibodies represent not only a diagnostic marker of the disease, but are also pathogenic, altering NMDA receptor–related synaptic transmission, Dr. Dalmau said.

In several recent studies, investigators have attempted to cobble together a distinct phenotype on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis to aid psychiatrists who might encounter patients with the disease, he said.

In one of the most recent studies, researchers combed the medical literature and found that, among 544 individuals with the disease, the most common psychiatric symptoms were agitation, seen in 59%, and psychotic symptoms (particularly visual-auditory hallucinations and disorganized behavior) in 54%; catatonia was seen in 42% of adults and 35% of children.

according to a report from researchers in Berlin, Dr. Dalmau added. By picking up on those clinical signs, which included seizures, catatonia, autonomic instability, or hyperkinesia, the time from symptom onset to diagnosis could be cut in half, the researchers found.

There’s also a handy acronym that could serve as a mnemonic to pick up on “diagnostic clues” of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis among patients with new-onset psychiatric symptoms, Dr. Dalmau said.

That acronym, published in a review article by Dr. Dalmau and colleagues, is SEARCH For NMDAR-A, covering, in order: sleep dysfunction, excitement, agitation, rapid onset, child and young adult predominance, history of psychiatric disease (absent), fluctuating catatonia, negative and positive symptoms, memory deficit, decreased verbal output, antipsychotic intolerance, rule out neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and of course, antibodies (though the final “A” also stands for additional testing, including magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid studies, and electroencephalogram).

While the disease can be lethal, Dr. Dalmau said most patients respond to immunotherapy, and if applicable, treatment of the underlying tumor can help. The most common first-line treatments include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange, he said, while second-line treatments include the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab and cyclophosphamide.

Beyond immunotherapy, patients may benefit from supportive care and psychiatric treatment. Benzodiazepines are well tolerated, but Dr. Dalmau said antipsychotic intolerance is frequent, and electroconvulsive therapy has “mixed results” in these patients.

The recovery process can take months and may be complicated by hypersomnia, hyperphagia, and hypersexuality, he added.

“Some patients improve dramatically in 1 month, but this is uncommon, really,” he said, adding that an early recovery may be a “red flag” that the underlying condition is something other than anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Dr. Dalmau provided disclosures related to Cellex Foundation, Safra Foundation, Caixa Health Project Foundation, and Sage Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Dalmau J. APA 2020, Abstract.

New insights and ‘red flags’ provide clues to diagnosis

New insights and ‘red flags’ provide clues to diagnosis

It remains difficult to distinguish anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis from a primary psychiatric disorder, but recent studies have identified clinical features and proposed screening criteria that could make it easier to identify these patients who would benefit from immunotherapy, according to an expert in the neurologic disease.

Most patients with confirmed anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis will experience substantial improvement after treatment with immunotherapy and other modalities, said Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, professor at the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Barcelona and adjunct professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In our experience, being aggressive with immune therapy ... the patients do quite well, which means that basically 85%-90% of the patients substantially improved over the next few months,” Dr. Dalmau said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

Identified for the first time a little more than a decade ago, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is a rare, immune-mediated disease that is usually found in children and young adults and is more common among women. It is frequently associated with ovarian tumors and teratomas, said Dr. Dalmau, and in about 90% of cases, patients will have prominent psychiatric and behavioral symptoms.

Patients develop IgG antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the NMDA receptor. These autoantibodies represent not only a diagnostic marker of the disease, but are also pathogenic, altering NMDA receptor–related synaptic transmission, Dr. Dalmau said.

In several recent studies, investigators have attempted to cobble together a distinct phenotype on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis to aid psychiatrists who might encounter patients with the disease, he said.

In one of the most recent studies, researchers combed the medical literature and found that, among 544 individuals with the disease, the most common psychiatric symptoms were agitation, seen in 59%, and psychotic symptoms (particularly visual-auditory hallucinations and disorganized behavior) in 54%; catatonia was seen in 42% of adults and 35% of children.

according to a report from researchers in Berlin, Dr. Dalmau added. By picking up on those clinical signs, which included seizures, catatonia, autonomic instability, or hyperkinesia, the time from symptom onset to diagnosis could be cut in half, the researchers found.

There’s also a handy acronym that could serve as a mnemonic to pick up on “diagnostic clues” of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis among patients with new-onset psychiatric symptoms, Dr. Dalmau said.

That acronym, published in a review article by Dr. Dalmau and colleagues, is SEARCH For NMDAR-A, covering, in order: sleep dysfunction, excitement, agitation, rapid onset, child and young adult predominance, history of psychiatric disease (absent), fluctuating catatonia, negative and positive symptoms, memory deficit, decreased verbal output, antipsychotic intolerance, rule out neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and of course, antibodies (though the final “A” also stands for additional testing, including magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid studies, and electroencephalogram).

While the disease can be lethal, Dr. Dalmau said most patients respond to immunotherapy, and if applicable, treatment of the underlying tumor can help. The most common first-line treatments include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange, he said, while second-line treatments include the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab and cyclophosphamide.

Beyond immunotherapy, patients may benefit from supportive care and psychiatric treatment. Benzodiazepines are well tolerated, but Dr. Dalmau said antipsychotic intolerance is frequent, and electroconvulsive therapy has “mixed results” in these patients.

The recovery process can take months and may be complicated by hypersomnia, hyperphagia, and hypersexuality, he added.

“Some patients improve dramatically in 1 month, but this is uncommon, really,” he said, adding that an early recovery may be a “red flag” that the underlying condition is something other than anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Dr. Dalmau provided disclosures related to Cellex Foundation, Safra Foundation, Caixa Health Project Foundation, and Sage Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Dalmau J. APA 2020, Abstract.

It remains difficult to distinguish anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis from a primary psychiatric disorder, but recent studies have identified clinical features and proposed screening criteria that could make it easier to identify these patients who would benefit from immunotherapy, according to an expert in the neurologic disease.

Most patients with confirmed anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis will experience substantial improvement after treatment with immunotherapy and other modalities, said Josep Dalmau, MD, PhD, professor at the Catalan Institute for Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Barcelona and adjunct professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“In our experience, being aggressive with immune therapy ... the patients do quite well, which means that basically 85%-90% of the patients substantially improved over the next few months,” Dr. Dalmau said at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, which was held as a virtual live event.

Identified for the first time a little more than a decade ago, anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis is a rare, immune-mediated disease that is usually found in children and young adults and is more common among women. It is frequently associated with ovarian tumors and teratomas, said Dr. Dalmau, and in about 90% of cases, patients will have prominent psychiatric and behavioral symptoms.

Patients develop IgG antibodies against the GluN1 subunit of the NMDA receptor. These autoantibodies represent not only a diagnostic marker of the disease, but are also pathogenic, altering NMDA receptor–related synaptic transmission, Dr. Dalmau said.

In several recent studies, investigators have attempted to cobble together a distinct phenotype on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis to aid psychiatrists who might encounter patients with the disease, he said.

In one of the most recent studies, researchers combed the medical literature and found that, among 544 individuals with the disease, the most common psychiatric symptoms were agitation, seen in 59%, and psychotic symptoms (particularly visual-auditory hallucinations and disorganized behavior) in 54%; catatonia was seen in 42% of adults and 35% of children.

according to a report from researchers in Berlin, Dr. Dalmau added. By picking up on those clinical signs, which included seizures, catatonia, autonomic instability, or hyperkinesia, the time from symptom onset to diagnosis could be cut in half, the researchers found.

There’s also a handy acronym that could serve as a mnemonic to pick up on “diagnostic clues” of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis among patients with new-onset psychiatric symptoms, Dr. Dalmau said.

That acronym, published in a review article by Dr. Dalmau and colleagues, is SEARCH For NMDAR-A, covering, in order: sleep dysfunction, excitement, agitation, rapid onset, child and young adult predominance, history of psychiatric disease (absent), fluctuating catatonia, negative and positive symptoms, memory deficit, decreased verbal output, antipsychotic intolerance, rule out neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and of course, antibodies (though the final “A” also stands for additional testing, including magnetic resonance imaging, cerebrospinal fluid studies, and electroencephalogram).

While the disease can be lethal, Dr. Dalmau said most patients respond to immunotherapy, and if applicable, treatment of the underlying tumor can help. The most common first-line treatments include steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange, he said, while second-line treatments include the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab and cyclophosphamide.

Beyond immunotherapy, patients may benefit from supportive care and psychiatric treatment. Benzodiazepines are well tolerated, but Dr. Dalmau said antipsychotic intolerance is frequent, and electroconvulsive therapy has “mixed results” in these patients.

The recovery process can take months and may be complicated by hypersomnia, hyperphagia, and hypersexuality, he added.

“Some patients improve dramatically in 1 month, but this is uncommon, really,” he said, adding that an early recovery may be a “red flag” that the underlying condition is something other than anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Dr. Dalmau provided disclosures related to Cellex Foundation, Safra Foundation, Caixa Health Project Foundation, and Sage Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Dalmau J. APA 2020, Abstract.

FROM APA 2020

Trials and tribulations: Neurology research during COVID-19

However, researchers remain determined to forge ahead – with many redesigning their studies, at least in part to optimize the safety of their participants and research staff.

Keeping people engaged while protocols are on hold; expanding normal safety considerations; and re-enlisting statisticians to keep their findings as significant as possible are just some of study survival strategies underway.

Alzheimer’s disease research on hold

The pandemic is having a significant impact on Alzheimer’s disease research, and medical research in general, says Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president, Medical & Scientific Relations at the Alzheimer’s Association.

“Many clinical trials worldwide are pausing, changing, or halting the testing of the drug or the intervention,” she told Medscape Medical News. “How the teams have adapted depends on the study,” she added. “As you can imagine, things are changing on a daily basis.”

The US Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk (U.S. POINTER) trial, for example, is on hold until at least May 31. The Alzheimer’s Association is helping to implement and fund the study along with Wake Forest University Medical Center.

“We’re not randomizing participants at this point in time and the intervention — which is based on a team meeting, and there is a social aspect to that — has been paused,” Dr. Snyder said.

Another pivotal study underway is the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s study (the A4 Study). Investigators are evaluating if an anti-amyloid antibody, solanezumab (Eli Lilly), can slow memory loss among people with amyloid on imaging but no symptoms of cognitive decline at baseline.

“The A4 Study is definitely continuing. However, in an effort to minimize risk to participants, site staff and study integrity, we have implemented an optional study hiatus for both the double-blind and open-label extension phases,” lead investigator Reisa Anne Sperling, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

“We wanted to prioritize the safety of our participants as well as the ability of participants to remain in the study … despite disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Dr. Sperling, who is professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The ultimate goal is for A4 participants to receive the full number of planned infusions and assessments, even if it takes longer, she added.

Many Alzheimer’s disease researchers outside the United States face similar challenges. “As you probably are well aware, Spain is now in a complete lockdown. This has affected research centers like ours, the Barcelona Brain Research Center, and the way we work,” José Luís Molinuevo Guix, MD, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

All participants in observational studies like the ALFA+ study and initiatives, as well as those in trials including PENSA and AB1601, “are not allowed, by law, to come in, hence from a safety perspective we are on good grounds,” added Dr. Molinuevo Guix, who directs the Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders unit at the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona.

The investigators are creating protocols for communicating with participants during the pandemic and for restarting visits safely after the lockdown has ended.

Stroke studies amended or suspended

A similar situation is occurring in stroke trials. Stroke is “obviously an acute disease, as well as a disease that requires secondary prevention,” Mitchell Elkind, MD, president-elect of the American Heart Association, told Medscape Medical News.

“One could argue that patients with stroke are going to be in the hospital anyway – why not enroll them in a study? They’re not incurring any additional risk,” he said. “But the staff have to come in to see them, and we’re really trying to avoid exposure.”

One ongoing trial, the Atrial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke (ARCADIA), stopped randomly assigning new participants to secondary prevention with apixaban or aspirin because of COVID-19. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues plan to provide medication to the 440 people already in the trial.

“Wherever possible, the study coordinators are shipping the drug to people and doing follow-up visits by phone or video,” said Dr. Elkind, chief of the Division of Neurology Clinical Outcomes Research and Population Sciences at Columbia University in New York City.

Protecting patients, staff, and ultimately society is a “major driving force in stopping the randomizations,” he stressed.

ARCADIA is part of the StrokeNet prevention trials network, run by the NIH’s National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional pivotal trials include the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy Versus Stenting Trial (CREST) and the Multi-arm Optimization of Stroke Thrombolysis (MOST) studies, he said.

Joseph Broderick, MD, director of the national NIH StrokeNet, agreed that safety comes first. “It was the decision of the StrokeNet leadership and the principal investigators of the trials that we needed to hold recruitment of new patients while we worked on adapting processes of enrollment to ensure the safety of both patients and researchers interacting with study patients,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Potential risks vary based on the study intervention and the need for in-person interactions. Trials that include stimulation devices or physical therapy, for example, might be most affected, added Dr. Broderick, professor and director of the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

Nevertheless, “there are potential ways … to move as much as possible toward telemedicine and digital interactions during this time.”

Multiple challenges in multiple sclerosis

At the national level, the COVID-19 pandemic has had an “unprecedented impact on almost all the clinical trials funded by NINDS,” said Clinton Wright, MD, director of the Division of Clinical Research at NINDS. “Investigators have had to adapt quickly.”

Supplementing existing grants with money to conduct research on COVID-19 and pursuing research opportunities from different institutes are “some of the creative approaches [that] have come from the NIH [National Institutes of Health] itself,” Dr. Wright said. “Other creative approaches have come from investigators trying to keep their studies and trials going during the pandemic.”

In clinical trials, “everything from electronic consent to in-home research drug delivery is being brought to bear.”

“A few ongoing trials have been able to modify their protocols to obtain consent and carry out evaluations remotely by telephone or videoconferencing,” Dr. Wright said. “This is especially critical for trials that involve medical management of specific risk factors or conditions, where suspension of the trial could itself have adverse consequences due to reduced engagement with research participants.”

For participants already in MS studies, “each upcoming visit is assessed for whether it’s critical or could be done virtually or just skipped. If a person needs a treatment that cannot be postponed or skipped, they come in,” Jeffrey Cohen, MD, director of the Experimental Therapeutics Program at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, told Medscape Medical News.

New study enrollment is largely on hold and study visits for existing participants are limited, said Dr. Cohen, who is also president of the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS).

Some of the major ongoing trials in MS are “looking at very fundamental questions in the field,” Dr. Cohen said. The Determining the Effectiveness of earLy Intensive Versus Escalation Approaches for RRMS (DELIVER-MS) and Traditional Versus Early Aggressive Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis (TREAT-MS) trials, for example, evaluate whether treatment should be initiated with one of the less efficacious agents with escalation as needed, or whether treatment should begin with a high-efficacy agent.

Both trials are currently on hold because of the pandemic, as is the Best Available Therapy Versus Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant for Multiple Sclerosis (BEAT-MS) study.

“There has been a lot of interest in hematopoietic stem cell transplants and where they fit into our overall treatment strategy, and this is intended to provide a more definitive answer,” Dr. Cohen said.

Making the most of down time

“The pandemic has been challenging” in terms of ongoing MS research, said Benjamin M. Segal, MD, chair of the Department of Neurology and director of the Neuroscience Research Institute at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

“With regard to the lab, our animal model experiments have been placed on hold. We have stopped collecting samples from clinical subjects for biomarker studies.

“However, my research team has been taking advantage of the time that has been freed up from bench work by analyzing data sets that had been placed aside, delving more deeply into the literature, and writing new grant proposals and articles,” he added.

Two of Dr. Segal’s trainees are writing review articles on the immunopathogenesis of MS and its treatment. Another postdoctoral candidate is writing a grant proposal to investigate how coinfection with a coronavirus modulates CNS pathology and the clinical course of an animal model of MS.

“I am asking my trainees to plan out experiments further in advance than they ever have before, so they are as prepared as possible to resume their research agendas once we are up and running again,” Dr. Segal said.

Confronting current challenges while planning for a future less disrupted by the pandemic is a common theme that emerges.

“The duration of this [pandemic] will dictate how we analyze the data at the end [for the US POINTER study]. There is a large group of statisticians working on this,” Dr. Snyder said.

Dr. Sperling of Harvard Medical School also remains undeterred. “This is definitely a challenging time, as we must not allow the COVID-19 to interfere with our essential mission to find a successful treatment to prevent cognitive decline in AD. We do need, however, to be as flexible as possible to protect our participants and minimize the impact to our overall study integrity,” she said.

NIH guidance

Dr. Molinuevo Guix, of the Barcelona Brain Research Center, is also determined to continue his Alzheimer’s disease research. “I am aware that after the crisis, there will be less [risk] but still a COVID-19 infection risk, so apart from trying to generate part of our visits virtually, we want to make sure we have all necessary safety measures in place. We remain very active to preserve the work we have done to keep up the fight against Alzheimer’s and dementia,” he said.

Such forward thinking also applies to major stroke trials, said Dr. Broderick of the University of Cincinnati. “As soon as we shut down enrollment in stroke trials, we immediately began to make plans about how and when we can restart our stroke trials,” he explained. “One of our trials can do every step of the trial process remotely without direct in-person interactions and will be able to restart soon.”

An individualized approach is needed, Dr. Broderick added. “For trials involving necessary in-person and hands-on assessments, we will need to consider how best to use protective equipment and expanded testing that will likely match the ongoing clinical care and requirements at a given institution.

“Even if a trial officially reopens enrollment, the decision to enroll locally will need to follow local institutional environment and guidelines. Thus, restart of trial enrollment will not likely be uniform, similar to how trials often start in the first place,” Dr. Broderick said.

The NIH published uniform standards for researchers across its institutes to help guide them during the pandemic. Future contingency plans also are underway at the NINDS.

“As the pandemic wanes and in-person research activities restart, it will be important to have in place safety measures that prevent a resurgence of the virus, such as proper personal protective equipment for staff and research participants, said Dr. Wright, the clinical research director at NINDS.

For clinical trials, NINDS is prepared to provide supplemental funds to trial investigators to help support additional activities undertaken as a result of the pandemic.

“This has been an instructive experience. The pandemic will end, and we will resume much of our old patterns of behavior,” said Ohio State’s Dr. Segal. “But some of the strategies that we have employed to get through this time will continue to influence the way we communicate information, plan experiments, and prioritize research activities in the future, to good effect.”

Drs. Snyder, Sperling, Molinuevo Guix, Elkind, Broderick, Wright, Cohen, and Segal have disclosed no relevant disclosures.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

However, researchers remain determined to forge ahead – with many redesigning their studies, at least in part to optimize the safety of their participants and research staff.

Keeping people engaged while protocols are on hold; expanding normal safety considerations; and re-enlisting statisticians to keep their findings as significant as possible are just some of study survival strategies underway.

Alzheimer’s disease research on hold

The pandemic is having a significant impact on Alzheimer’s disease research, and medical research in general, says Heather Snyder, PhD, vice president, Medical & Scientific Relations at the Alzheimer’s Association.

“Many clinical trials worldwide are pausing, changing, or halting the testing of the drug or the intervention,” she told Medscape Medical News. “How the teams have adapted depends on the study,” she added. “As you can imagine, things are changing on a daily basis.”

The US Study to Protect Brain Health Through Lifestyle Intervention to Reduce Risk (U.S. POINTER) trial, for example, is on hold until at least May 31. The Alzheimer’s Association is helping to implement and fund the study along with Wake Forest University Medical Center.

“We’re not randomizing participants at this point in time and the intervention — which is based on a team meeting, and there is a social aspect to that — has been paused,” Dr. Snyder said.

Another pivotal study underway is the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s study (the A4 Study). Investigators are evaluating if an anti-amyloid antibody, solanezumab (Eli Lilly), can slow memory loss among people with amyloid on imaging but no symptoms of cognitive decline at baseline.

“The A4 Study is definitely continuing. However, in an effort to minimize risk to participants, site staff and study integrity, we have implemented an optional study hiatus for both the double-blind and open-label extension phases,” lead investigator Reisa Anne Sperling, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

“We wanted to prioritize the safety of our participants as well as the ability of participants to remain in the study … despite disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Dr. Sperling, who is professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

The ultimate goal is for A4 participants to receive the full number of planned infusions and assessments, even if it takes longer, she added.

Many Alzheimer’s disease researchers outside the United States face similar challenges. “As you probably are well aware, Spain is now in a complete lockdown. This has affected research centers like ours, the Barcelona Brain Research Center, and the way we work,” José Luís Molinuevo Guix, MD, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

All participants in observational studies like the ALFA+ study and initiatives, as well as those in trials including PENSA and AB1601, “are not allowed, by law, to come in, hence from a safety perspective we are on good grounds,” added Dr. Molinuevo Guix, who directs the Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disorders unit at the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona.

The investigators are creating protocols for communicating with participants during the pandemic and for restarting visits safely after the lockdown has ended.

Stroke studies amended or suspended

A similar situation is occurring in stroke trials. Stroke is “obviously an acute disease, as well as a disease that requires secondary prevention,” Mitchell Elkind, MD, president-elect of the American Heart Association, told Medscape Medical News.

“One could argue that patients with stroke are going to be in the hospital anyway – why not enroll them in a study? They’re not incurring any additional risk,” he said. “But the staff have to come in to see them, and we’re really trying to avoid exposure.”

One ongoing trial, the Atrial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke (ARCADIA), stopped randomly assigning new participants to secondary prevention with apixaban or aspirin because of COVID-19. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues plan to provide medication to the 440 people already in the trial.

“Wherever possible, the study coordinators are shipping the drug to people and doing follow-up visits by phone or video,” said Dr. Elkind, chief of the Division of Neurology Clinical Outcomes Research and Population Sciences at Columbia University in New York City.

Protecting patients, staff, and ultimately society is a “major driving force in stopping the randomizations,” he stressed.

ARCADIA is part of the StrokeNet prevention trials network, run by the NIH’s National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional pivotal trials include the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy Versus Stenting Trial (CREST) and the Multi-arm Optimization of Stroke Thrombolysis (MOST) studies, he said.

Joseph Broderick, MD, director of the national NIH StrokeNet, agreed that safety comes first. “It was the decision of the StrokeNet leadership and the principal investigators of the trials that we needed to hold recruitment of new patients while we worked on adapting processes of enrollment to ensure the safety of both patients and researchers interacting with study patients,” he told Medscape Medical News.