User login

New Clues on How Blast Exposure May Lead to Alzheimer’s Disease

In October 2023, Robert Card — a grenade instructor in the Army Reserve — shot and killed 18 people in Maine, before turning the gun on himself. As reported by The New York Times, his family said that he had become increasingly erratic and violent during the months before the rampage.

A postmortem conducted by the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center at Boston University found “significant evidence of traumatic brain injuries” [TBIs] and “significant degeneration, axonal and myelin loss, inflammation, and small blood vessel injury” in the white matter, the center’s director, Ann McKee, MD, said in a press release. “These findings align with our previous studies on the effects of blast injury in humans and experimental models.”

Members of the military, such as Mr. Card, are exposed to blasts from repeated firing of heavy weapons not only during combat but also during training.

A higher index of suspicion for dementia or Alzheimer’s disease may be warranted in patients with a history of blast exposure or subconcussive brain injury who present with cognitive issues, according to experts interviewed.

In 2022, the US Department of Defense (DOD) launched its Warfighter Brain Health Initiative with the aim of “optimizing service member brain health and countering traumatic brain injuries.”

In April 2024, the Blast Overpressure Safety Act was introduced in the Senate to require the DOD to enact better blast screening, tracking, prevention, and treatment. The DOD initiated 26 blast overpressure studies.

Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of Medical and Scientific Relations, said that an important component of that research involves “the need to study the difference between TBI-caused dementia and dementia caused independently” and “the need to study biomarkers to better understand the long-term consequences of TBI.”

What Is the Underlying Biology?

Dr. Snyder was the lead author of a white paper produced by the Alzheimer’s Association in 2018 on military-related risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. “There is a lot of work trying to understand the effect of pure blast waves on the brain, as opposed to the actual impact of the injury,” she said.

The white paper speculated that blast exposure may be analogous to subconcussive brain injury in athletes where there are no obvious immediate clinical symptoms or neurological dysfunction but which can cause cumulative injury and functional impairment over time.

“We are also trying to understand the underlying biology around brain changes, such as accumulation of tau and amyloid and other specific markers related to brain changes in Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Snyder, chair of the Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program Programmatic Panel for Alzheimer’s Disease/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and TBI.

Common Biomarker Signatures

A recent study in Neurology comparing 51 veterans with mild TBI (mTBI) with 85 veterans and civilians with no lifetime history of TBI is among the first to explore these biomarker changes in human beings.

“Our findings suggest that chronic neuropathologic processes associated with blast mTBI share properties in common with pathogenic processes that are precursors to Alzheimer’s disease onset,” said coauthor Elaine R. Peskind, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Washington, Seattle.

The largely male participants were a mean age of 34 years and underwent standardized clinical and neuropsychological testing as well as lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The mTBI group had experienced at least one war zone blast or combined blast/impact that met criteria for mTBI, but 91% had more than one blast mTBI, and the study took place over 13 years.

The researchers found that the mTBI group “had biomarker signatures in common with the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Peskind.

For example, at age 50, they had lower mean levels of CSF amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42), the earliest marker of brain parenchymal Abeta deposition, compared with the control group (154 pg/mL and 1864 pg/mL lower, respectively).

High CSF phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181) and total tau are established biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. However, levels of these biomarkers remained “relatively constant with age” in participants with mTBI but were higher in older ages for the non-TBI group.

The mTBI group also showed worse cognitive performance at older ages (P < .08). Poorer verbal memory and verbal fluency performance were associated with lower CSF Abeta42 in older participants (P ≤ .05).

In Alzheimer’s disease, a reduction in CSF Abeta42 may occur up to 20 years before the onset of clinical symptoms, according to Dr. Peskind. “But what we don’t know from this study is what this means, as total tau protein and p-tau181 in the CSF were also low, which isn’t entirely typical in the picture of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease,” she said. However, changes in total tau and p-tau181 lag behind changes in Abeta42.

Is Impaired Clearance the Culprit?

Coauthor Jeffrey Iliff, PhD, professor, University of Washington Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and University of Washington Department of Neurology, Seattle, elaborated.

“In the setting of Alzheimer’s disease, a signature of the disease is reduced CSF Abeta42, which is thought to reflect that much of the amyloid gets ‘stuck’ in the brain in the form of amyloid plaques,” he said. “There are usually higher levels of phosphorylated tau and total tau, which are thought to reflect the presence of tau tangles and degeneration of neurons in the brain. But in this study, all of those were lowered, which is not exactly an Alzheimer’s disease profile.”

Dr. Iliff, associate director for research, VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, suggested that the culprit may be impairment in the brain’s glymphatic system. “Recently described biological research supports [the concept of] clearance of waste out of the brain during sleep via the glymphatic system, with amyloid and tau being cleared from the brain interstitium during sleep.”

A recent hypothesis is that blast TBI impairs that process. “This is why we see less of those proteins in the CSF. They’re not being cleared, which might contribute downstream to the clumping up of protein in the brain,” he suggested.

The evidence base corroborating that hypothesis is in its infancy; however, new research conducted by Dr. Iliff and his colleagues sheds light on this potential mechanism.

In blast TBI, energy from the explosion and resulting overpressure wave are “transmitted through the brain, which causes tissues of different densities — such as gray and white matter — to accelerate at different rates,” according to Dr. Iliff. This results in the shearing and stretching of brain tissue, leading to a “diffuse pattern of tissue damage.”

It is known that blast TBI has clinical overlap and associations with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and persistent neurobehavioral symptoms; that veterans with a history of TBI are more than twice as likely to die by suicide than veterans with no TBI history; and that TBI may increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders, as well as CTE.

The missing link may be the glymphatic system — a “brain-wide network of perivascular pathways, along which CSF and interstitial fluid (ISF) exchange, supporting the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid-beta.”

Dr. Iliff and his group previously found that glymphatic function is “markedly and chronically impaired” following impact TBI in mice and that this impairment is associated with the mislocalization of astroglial aquaporin 4 (AQP4), a water channel that lines perivascular spaces and plays a role in healthy glymphatic exchange.

In their new study, the researchers examined both the expression and the localization of AQP4 in the human postmortem frontal cortex and found “distinct laminar differences” in AQP4 expression following blast exposure. They observed similar changes as well as impairment of glymphatic function, which emerged 28 days following blast injury in a mouse model of repetitive blast mTBI.

And in a cohort of veterans with blast mTBI, blast exposure was found to be associated with an increased burden of frontal cortical MRI-visible perivascular spaces — a “putative neuroimaging marker” of glymphatic perivascular dysfunction.

The earlier Neurology study “showed impairment of biomarkers in the CSF, but the new study showed ‘why’ or ‘how’ these biomarkers are impaired, which is via impairment of the glymphatic clearance process,” Dr. Iliff explained.

Veterans Especially Vulnerable

Dr. Peskind, co-director of the VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, noted that while the veterans in the earlier study had at least one TBI, the average number was 20, and it was more common to have more than 50 mTBIs than to have a single one.

“These were highly exposed combat vets,” she said. “And that number doesn’t even account for subconcussive exposure to blasts, which now appear to cause detectable brain damage, even in the absence of a diagnosable TBI.”

The Maine shooter, Mr. Card, had not seen combat and was not assessed for TBI during a psychiatric hospitalization, according to The New York Times.

Dr. Peskind added that this type of blast damage is likely specific to individuals in the military. “It isn’t the sound that causes the damage,” she explained. “It’s the blast wave, the pressure wave, and there aren’t a lot of other occupations that have those types of occupational exposures.”

Dr. Snyder added that the majority of blast TBIs have been studied in military personnel, and she is not aware of studies that have looked at blast injuries in other industries, such as demolition or mining, to see if they have the same type of biologic consequences.

Dr. Snyder hopes that the researchers will follow the participants in the Neurology study and continue looking at specific markers related to Alzheimer’s disease brain changes. What the research so far shows “is that, at an earlier age, we’re starting to see those markers changing, suggesting that the underlying biology in people with mild blast TBI is similar to the underlying biology in Alzheimer’s disease as well.”

Michael Alosco, PhD, associate professor and vice chair of research, department of neurology, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, called the issue of blast exposure and TBI “a very complex and nuanced topic,” especially because TBI is “considered a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease” and “different types of TBIs could trigger distinct pathophysiologic processes; however, the long-term impact of repetitive blast TBIs on neurodegenerative disease changes remains unknown.”

He coauthored an editorial on the earlier Neurology study that noted its limitations, such as a small sample size and lack of consideration of lifestyle and health factors but acknowledged that the “findings provide preliminary evidence that repetitive blast exposures might influence beta-amyloid accumulation.”

Clinical Implications

For Dr. Peskind, the “inflection point” was seeing lower CSF Abeta42, about 20 years earlier than ages 60 and 70, which is more typical in cognitively normal community volunteers.

But she described herself as “loath to say that veterans or service members have a 20-year acceleration of risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” adding, “I don’t want to scare the heck out of our service members of veterans.” Although “this is what we fear, we’re not ready to say it for sure yet because we need to do more work. Nevertheless, it does increase the index of suspicion.”

The clinical take-home messages are not unique to service members or veterans or people with a history of head injuries or a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease, she emphasized. “If anyone of any age or occupation comes in with cognitive issues, such as [impaired] memory or executive function, they deserve a workup for dementing disorders.” Frontotemporal dementia, for example, can present earlier than Alzheimer’s disease typically does.

Common comorbidities with TBI are PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can also cause cognitive issues and are also risk factors for dementia.

Dr. Iliff agreed. “If you see a veteran with a history of PTSD, a history of blast TBI, and a history of OSA or some combination of those three, I recommend having a higher index of suspicion [for potential dementia] than for an average person without any of these, even at a younger age than one would ordinarily expect.”

Of all of these factors, the only truly directly modifiable one is sleep disruption, including that caused by OSA or sleep disorders related to PTSD, he added. “Epidemiologic data suggest a connection particularly between midlife sleep disruption and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and so it’s worth thinking about sleep as a modifiable risk factor even as early as the 40s and 50s, whether the patient is or isn’t a veteran.”

Dr. Peskind recommended asking patients, “Do they snore? Do they thrash about during sleep? Do they have trauma nightmares? This will inform the type of intervention required.”

Dr. Alosco added that there is no known “safe” threshold of exposure to blasts, and that thresholds are “unclear, particularly at the individual level.” In American football, there is a dose-response relationship between years of play and risk for later-life neurological disorder. “The best way to mitigate risk is to limit cumulative exposure,” he said.

The study by Li and colleagues was funded by grant funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service and the University of Washington Friends of Alzheimer’s Research. Other sources of funding to individual researchers are listed in the original paper. The study by Braun and colleagues was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service; and the National Institute on Aging. The white paper included studies that received funding from numerous sources, including the National Institutes of Health and the DOD. Dr. Iliff serves as the chair of the Scientific Advisory Board for Applied Cognition Inc., from which he receives compensation and in which he holds an equity stake. In the last year, he served as a paid consultant to Gryphon Biosciences. Dr. Peskind has served as a paid consultant to the companies Genentech, Roche, and Alpha Cognition. Dr. Alosco was supported by grant funding from the NIH; he received research support from Rainwater Charitable Foundation Inc., and Life Molecular Imaging Inc.; he has received a single honorarium from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for services unrelated to this editorial; and he received royalties from Oxford University Press Inc. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original papers.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In October 2023, Robert Card — a grenade instructor in the Army Reserve — shot and killed 18 people in Maine, before turning the gun on himself. As reported by The New York Times, his family said that he had become increasingly erratic and violent during the months before the rampage.

A postmortem conducted by the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center at Boston University found “significant evidence of traumatic brain injuries” [TBIs] and “significant degeneration, axonal and myelin loss, inflammation, and small blood vessel injury” in the white matter, the center’s director, Ann McKee, MD, said in a press release. “These findings align with our previous studies on the effects of blast injury in humans and experimental models.”

Members of the military, such as Mr. Card, are exposed to blasts from repeated firing of heavy weapons not only during combat but also during training.

A higher index of suspicion for dementia or Alzheimer’s disease may be warranted in patients with a history of blast exposure or subconcussive brain injury who present with cognitive issues, according to experts interviewed.

In 2022, the US Department of Defense (DOD) launched its Warfighter Brain Health Initiative with the aim of “optimizing service member brain health and countering traumatic brain injuries.”

In April 2024, the Blast Overpressure Safety Act was introduced in the Senate to require the DOD to enact better blast screening, tracking, prevention, and treatment. The DOD initiated 26 blast overpressure studies.

Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of Medical and Scientific Relations, said that an important component of that research involves “the need to study the difference between TBI-caused dementia and dementia caused independently” and “the need to study biomarkers to better understand the long-term consequences of TBI.”

What Is the Underlying Biology?

Dr. Snyder was the lead author of a white paper produced by the Alzheimer’s Association in 2018 on military-related risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. “There is a lot of work trying to understand the effect of pure blast waves on the brain, as opposed to the actual impact of the injury,” she said.

The white paper speculated that blast exposure may be analogous to subconcussive brain injury in athletes where there are no obvious immediate clinical symptoms or neurological dysfunction but which can cause cumulative injury and functional impairment over time.

“We are also trying to understand the underlying biology around brain changes, such as accumulation of tau and amyloid and other specific markers related to brain changes in Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Snyder, chair of the Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program Programmatic Panel for Alzheimer’s Disease/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and TBI.

Common Biomarker Signatures

A recent study in Neurology comparing 51 veterans with mild TBI (mTBI) with 85 veterans and civilians with no lifetime history of TBI is among the first to explore these biomarker changes in human beings.

“Our findings suggest that chronic neuropathologic processes associated with blast mTBI share properties in common with pathogenic processes that are precursors to Alzheimer’s disease onset,” said coauthor Elaine R. Peskind, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Washington, Seattle.

The largely male participants were a mean age of 34 years and underwent standardized clinical and neuropsychological testing as well as lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The mTBI group had experienced at least one war zone blast or combined blast/impact that met criteria for mTBI, but 91% had more than one blast mTBI, and the study took place over 13 years.

The researchers found that the mTBI group “had biomarker signatures in common with the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Peskind.

For example, at age 50, they had lower mean levels of CSF amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42), the earliest marker of brain parenchymal Abeta deposition, compared with the control group (154 pg/mL and 1864 pg/mL lower, respectively).

High CSF phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181) and total tau are established biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. However, levels of these biomarkers remained “relatively constant with age” in participants with mTBI but were higher in older ages for the non-TBI group.

The mTBI group also showed worse cognitive performance at older ages (P < .08). Poorer verbal memory and verbal fluency performance were associated with lower CSF Abeta42 in older participants (P ≤ .05).

In Alzheimer’s disease, a reduction in CSF Abeta42 may occur up to 20 years before the onset of clinical symptoms, according to Dr. Peskind. “But what we don’t know from this study is what this means, as total tau protein and p-tau181 in the CSF were also low, which isn’t entirely typical in the picture of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease,” she said. However, changes in total tau and p-tau181 lag behind changes in Abeta42.

Is Impaired Clearance the Culprit?

Coauthor Jeffrey Iliff, PhD, professor, University of Washington Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and University of Washington Department of Neurology, Seattle, elaborated.

“In the setting of Alzheimer’s disease, a signature of the disease is reduced CSF Abeta42, which is thought to reflect that much of the amyloid gets ‘stuck’ in the brain in the form of amyloid plaques,” he said. “There are usually higher levels of phosphorylated tau and total tau, which are thought to reflect the presence of tau tangles and degeneration of neurons in the brain. But in this study, all of those were lowered, which is not exactly an Alzheimer’s disease profile.”

Dr. Iliff, associate director for research, VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, suggested that the culprit may be impairment in the brain’s glymphatic system. “Recently described biological research supports [the concept of] clearance of waste out of the brain during sleep via the glymphatic system, with amyloid and tau being cleared from the brain interstitium during sleep.”

A recent hypothesis is that blast TBI impairs that process. “This is why we see less of those proteins in the CSF. They’re not being cleared, which might contribute downstream to the clumping up of protein in the brain,” he suggested.

The evidence base corroborating that hypothesis is in its infancy; however, new research conducted by Dr. Iliff and his colleagues sheds light on this potential mechanism.

In blast TBI, energy from the explosion and resulting overpressure wave are “transmitted through the brain, which causes tissues of different densities — such as gray and white matter — to accelerate at different rates,” according to Dr. Iliff. This results in the shearing and stretching of brain tissue, leading to a “diffuse pattern of tissue damage.”

It is known that blast TBI has clinical overlap and associations with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and persistent neurobehavioral symptoms; that veterans with a history of TBI are more than twice as likely to die by suicide than veterans with no TBI history; and that TBI may increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders, as well as CTE.

The missing link may be the glymphatic system — a “brain-wide network of perivascular pathways, along which CSF and interstitial fluid (ISF) exchange, supporting the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid-beta.”

Dr. Iliff and his group previously found that glymphatic function is “markedly and chronically impaired” following impact TBI in mice and that this impairment is associated with the mislocalization of astroglial aquaporin 4 (AQP4), a water channel that lines perivascular spaces and plays a role in healthy glymphatic exchange.

In their new study, the researchers examined both the expression and the localization of AQP4 in the human postmortem frontal cortex and found “distinct laminar differences” in AQP4 expression following blast exposure. They observed similar changes as well as impairment of glymphatic function, which emerged 28 days following blast injury in a mouse model of repetitive blast mTBI.

And in a cohort of veterans with blast mTBI, blast exposure was found to be associated with an increased burden of frontal cortical MRI-visible perivascular spaces — a “putative neuroimaging marker” of glymphatic perivascular dysfunction.

The earlier Neurology study “showed impairment of biomarkers in the CSF, but the new study showed ‘why’ or ‘how’ these biomarkers are impaired, which is via impairment of the glymphatic clearance process,” Dr. Iliff explained.

Veterans Especially Vulnerable

Dr. Peskind, co-director of the VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, noted that while the veterans in the earlier study had at least one TBI, the average number was 20, and it was more common to have more than 50 mTBIs than to have a single one.

“These were highly exposed combat vets,” she said. “And that number doesn’t even account for subconcussive exposure to blasts, which now appear to cause detectable brain damage, even in the absence of a diagnosable TBI.”

The Maine shooter, Mr. Card, had not seen combat and was not assessed for TBI during a psychiatric hospitalization, according to The New York Times.

Dr. Peskind added that this type of blast damage is likely specific to individuals in the military. “It isn’t the sound that causes the damage,” she explained. “It’s the blast wave, the pressure wave, and there aren’t a lot of other occupations that have those types of occupational exposures.”

Dr. Snyder added that the majority of blast TBIs have been studied in military personnel, and she is not aware of studies that have looked at blast injuries in other industries, such as demolition or mining, to see if they have the same type of biologic consequences.

Dr. Snyder hopes that the researchers will follow the participants in the Neurology study and continue looking at specific markers related to Alzheimer’s disease brain changes. What the research so far shows “is that, at an earlier age, we’re starting to see those markers changing, suggesting that the underlying biology in people with mild blast TBI is similar to the underlying biology in Alzheimer’s disease as well.”

Michael Alosco, PhD, associate professor and vice chair of research, department of neurology, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, called the issue of blast exposure and TBI “a very complex and nuanced topic,” especially because TBI is “considered a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease” and “different types of TBIs could trigger distinct pathophysiologic processes; however, the long-term impact of repetitive blast TBIs on neurodegenerative disease changes remains unknown.”

He coauthored an editorial on the earlier Neurology study that noted its limitations, such as a small sample size and lack of consideration of lifestyle and health factors but acknowledged that the “findings provide preliminary evidence that repetitive blast exposures might influence beta-amyloid accumulation.”

Clinical Implications

For Dr. Peskind, the “inflection point” was seeing lower CSF Abeta42, about 20 years earlier than ages 60 and 70, which is more typical in cognitively normal community volunteers.

But she described herself as “loath to say that veterans or service members have a 20-year acceleration of risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” adding, “I don’t want to scare the heck out of our service members of veterans.” Although “this is what we fear, we’re not ready to say it for sure yet because we need to do more work. Nevertheless, it does increase the index of suspicion.”

The clinical take-home messages are not unique to service members or veterans or people with a history of head injuries or a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease, she emphasized. “If anyone of any age or occupation comes in with cognitive issues, such as [impaired] memory or executive function, they deserve a workup for dementing disorders.” Frontotemporal dementia, for example, can present earlier than Alzheimer’s disease typically does.

Common comorbidities with TBI are PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can also cause cognitive issues and are also risk factors for dementia.

Dr. Iliff agreed. “If you see a veteran with a history of PTSD, a history of blast TBI, and a history of OSA or some combination of those three, I recommend having a higher index of suspicion [for potential dementia] than for an average person without any of these, even at a younger age than one would ordinarily expect.”

Of all of these factors, the only truly directly modifiable one is sleep disruption, including that caused by OSA or sleep disorders related to PTSD, he added. “Epidemiologic data suggest a connection particularly between midlife sleep disruption and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and so it’s worth thinking about sleep as a modifiable risk factor even as early as the 40s and 50s, whether the patient is or isn’t a veteran.”

Dr. Peskind recommended asking patients, “Do they snore? Do they thrash about during sleep? Do they have trauma nightmares? This will inform the type of intervention required.”

Dr. Alosco added that there is no known “safe” threshold of exposure to blasts, and that thresholds are “unclear, particularly at the individual level.” In American football, there is a dose-response relationship between years of play and risk for later-life neurological disorder. “The best way to mitigate risk is to limit cumulative exposure,” he said.

The study by Li and colleagues was funded by grant funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service and the University of Washington Friends of Alzheimer’s Research. Other sources of funding to individual researchers are listed in the original paper. The study by Braun and colleagues was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service; and the National Institute on Aging. The white paper included studies that received funding from numerous sources, including the National Institutes of Health and the DOD. Dr. Iliff serves as the chair of the Scientific Advisory Board for Applied Cognition Inc., from which he receives compensation and in which he holds an equity stake. In the last year, he served as a paid consultant to Gryphon Biosciences. Dr. Peskind has served as a paid consultant to the companies Genentech, Roche, and Alpha Cognition. Dr. Alosco was supported by grant funding from the NIH; he received research support from Rainwater Charitable Foundation Inc., and Life Molecular Imaging Inc.; he has received a single honorarium from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for services unrelated to this editorial; and he received royalties from Oxford University Press Inc. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original papers.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In October 2023, Robert Card — a grenade instructor in the Army Reserve — shot and killed 18 people in Maine, before turning the gun on himself. As reported by The New York Times, his family said that he had become increasingly erratic and violent during the months before the rampage.

A postmortem conducted by the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center at Boston University found “significant evidence of traumatic brain injuries” [TBIs] and “significant degeneration, axonal and myelin loss, inflammation, and small blood vessel injury” in the white matter, the center’s director, Ann McKee, MD, said in a press release. “These findings align with our previous studies on the effects of blast injury in humans and experimental models.”

Members of the military, such as Mr. Card, are exposed to blasts from repeated firing of heavy weapons not only during combat but also during training.

A higher index of suspicion for dementia or Alzheimer’s disease may be warranted in patients with a history of blast exposure or subconcussive brain injury who present with cognitive issues, according to experts interviewed.

In 2022, the US Department of Defense (DOD) launched its Warfighter Brain Health Initiative with the aim of “optimizing service member brain health and countering traumatic brain injuries.”

In April 2024, the Blast Overpressure Safety Act was introduced in the Senate to require the DOD to enact better blast screening, tracking, prevention, and treatment. The DOD initiated 26 blast overpressure studies.

Heather Snyder, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association vice president of Medical and Scientific Relations, said that an important component of that research involves “the need to study the difference between TBI-caused dementia and dementia caused independently” and “the need to study biomarkers to better understand the long-term consequences of TBI.”

What Is the Underlying Biology?

Dr. Snyder was the lead author of a white paper produced by the Alzheimer’s Association in 2018 on military-related risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. “There is a lot of work trying to understand the effect of pure blast waves on the brain, as opposed to the actual impact of the injury,” she said.

The white paper speculated that blast exposure may be analogous to subconcussive brain injury in athletes where there are no obvious immediate clinical symptoms or neurological dysfunction but which can cause cumulative injury and functional impairment over time.

“We are also trying to understand the underlying biology around brain changes, such as accumulation of tau and amyloid and other specific markers related to brain changes in Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Snyder, chair of the Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program Programmatic Panel for Alzheimer’s Disease/Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias and TBI.

Common Biomarker Signatures

A recent study in Neurology comparing 51 veterans with mild TBI (mTBI) with 85 veterans and civilians with no lifetime history of TBI is among the first to explore these biomarker changes in human beings.

“Our findings suggest that chronic neuropathologic processes associated with blast mTBI share properties in common with pathogenic processes that are precursors to Alzheimer’s disease onset,” said coauthor Elaine R. Peskind, MD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Washington, Seattle.

The largely male participants were a mean age of 34 years and underwent standardized clinical and neuropsychological testing as well as lumbar puncture to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The mTBI group had experienced at least one war zone blast or combined blast/impact that met criteria for mTBI, but 91% had more than one blast mTBI, and the study took place over 13 years.

The researchers found that the mTBI group “had biomarker signatures in common with the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Peskind.

For example, at age 50, they had lower mean levels of CSF amyloid beta 42 (Abeta42), the earliest marker of brain parenchymal Abeta deposition, compared with the control group (154 pg/mL and 1864 pg/mL lower, respectively).

High CSF phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181) and total tau are established biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. However, levels of these biomarkers remained “relatively constant with age” in participants with mTBI but were higher in older ages for the non-TBI group.

The mTBI group also showed worse cognitive performance at older ages (P < .08). Poorer verbal memory and verbal fluency performance were associated with lower CSF Abeta42 in older participants (P ≤ .05).

In Alzheimer’s disease, a reduction in CSF Abeta42 may occur up to 20 years before the onset of clinical symptoms, according to Dr. Peskind. “But what we don’t know from this study is what this means, as total tau protein and p-tau181 in the CSF were also low, which isn’t entirely typical in the picture of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease,” she said. However, changes in total tau and p-tau181 lag behind changes in Abeta42.

Is Impaired Clearance the Culprit?

Coauthor Jeffrey Iliff, PhD, professor, University of Washington Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and University of Washington Department of Neurology, Seattle, elaborated.

“In the setting of Alzheimer’s disease, a signature of the disease is reduced CSF Abeta42, which is thought to reflect that much of the amyloid gets ‘stuck’ in the brain in the form of amyloid plaques,” he said. “There are usually higher levels of phosphorylated tau and total tau, which are thought to reflect the presence of tau tangles and degeneration of neurons in the brain. But in this study, all of those were lowered, which is not exactly an Alzheimer’s disease profile.”

Dr. Iliff, associate director for research, VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, suggested that the culprit may be impairment in the brain’s glymphatic system. “Recently described biological research supports [the concept of] clearance of waste out of the brain during sleep via the glymphatic system, with amyloid and tau being cleared from the brain interstitium during sleep.”

A recent hypothesis is that blast TBI impairs that process. “This is why we see less of those proteins in the CSF. They’re not being cleared, which might contribute downstream to the clumping up of protein in the brain,” he suggested.

The evidence base corroborating that hypothesis is in its infancy; however, new research conducted by Dr. Iliff and his colleagues sheds light on this potential mechanism.

In blast TBI, energy from the explosion and resulting overpressure wave are “transmitted through the brain, which causes tissues of different densities — such as gray and white matter — to accelerate at different rates,” according to Dr. Iliff. This results in the shearing and stretching of brain tissue, leading to a “diffuse pattern of tissue damage.”

It is known that blast TBI has clinical overlap and associations with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and persistent neurobehavioral symptoms; that veterans with a history of TBI are more than twice as likely to die by suicide than veterans with no TBI history; and that TBI may increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementing disorders, as well as CTE.

The missing link may be the glymphatic system — a “brain-wide network of perivascular pathways, along which CSF and interstitial fluid (ISF) exchange, supporting the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid-beta.”

Dr. Iliff and his group previously found that glymphatic function is “markedly and chronically impaired” following impact TBI in mice and that this impairment is associated with the mislocalization of astroglial aquaporin 4 (AQP4), a water channel that lines perivascular spaces and plays a role in healthy glymphatic exchange.

In their new study, the researchers examined both the expression and the localization of AQP4 in the human postmortem frontal cortex and found “distinct laminar differences” in AQP4 expression following blast exposure. They observed similar changes as well as impairment of glymphatic function, which emerged 28 days following blast injury in a mouse model of repetitive blast mTBI.

And in a cohort of veterans with blast mTBI, blast exposure was found to be associated with an increased burden of frontal cortical MRI-visible perivascular spaces — a “putative neuroimaging marker” of glymphatic perivascular dysfunction.

The earlier Neurology study “showed impairment of biomarkers in the CSF, but the new study showed ‘why’ or ‘how’ these biomarkers are impaired, which is via impairment of the glymphatic clearance process,” Dr. Iliff explained.

Veterans Especially Vulnerable

Dr. Peskind, co-director of the VA Northwest Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, noted that while the veterans in the earlier study had at least one TBI, the average number was 20, and it was more common to have more than 50 mTBIs than to have a single one.

“These were highly exposed combat vets,” she said. “And that number doesn’t even account for subconcussive exposure to blasts, which now appear to cause detectable brain damage, even in the absence of a diagnosable TBI.”

The Maine shooter, Mr. Card, had not seen combat and was not assessed for TBI during a psychiatric hospitalization, according to The New York Times.

Dr. Peskind added that this type of blast damage is likely specific to individuals in the military. “It isn’t the sound that causes the damage,” she explained. “It’s the blast wave, the pressure wave, and there aren’t a lot of other occupations that have those types of occupational exposures.”

Dr. Snyder added that the majority of blast TBIs have been studied in military personnel, and she is not aware of studies that have looked at blast injuries in other industries, such as demolition or mining, to see if they have the same type of biologic consequences.

Dr. Snyder hopes that the researchers will follow the participants in the Neurology study and continue looking at specific markers related to Alzheimer’s disease brain changes. What the research so far shows “is that, at an earlier age, we’re starting to see those markers changing, suggesting that the underlying biology in people with mild blast TBI is similar to the underlying biology in Alzheimer’s disease as well.”

Michael Alosco, PhD, associate professor and vice chair of research, department of neurology, Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, called the issue of blast exposure and TBI “a very complex and nuanced topic,” especially because TBI is “considered a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease” and “different types of TBIs could trigger distinct pathophysiologic processes; however, the long-term impact of repetitive blast TBIs on neurodegenerative disease changes remains unknown.”

He coauthored an editorial on the earlier Neurology study that noted its limitations, such as a small sample size and lack of consideration of lifestyle and health factors but acknowledged that the “findings provide preliminary evidence that repetitive blast exposures might influence beta-amyloid accumulation.”

Clinical Implications

For Dr. Peskind, the “inflection point” was seeing lower CSF Abeta42, about 20 years earlier than ages 60 and 70, which is more typical in cognitively normal community volunteers.

But she described herself as “loath to say that veterans or service members have a 20-year acceleration of risk of Alzheimer’s disease,” adding, “I don’t want to scare the heck out of our service members of veterans.” Although “this is what we fear, we’re not ready to say it for sure yet because we need to do more work. Nevertheless, it does increase the index of suspicion.”

The clinical take-home messages are not unique to service members or veterans or people with a history of head injuries or a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease, she emphasized. “If anyone of any age or occupation comes in with cognitive issues, such as [impaired] memory or executive function, they deserve a workup for dementing disorders.” Frontotemporal dementia, for example, can present earlier than Alzheimer’s disease typically does.

Common comorbidities with TBI are PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which can also cause cognitive issues and are also risk factors for dementia.

Dr. Iliff agreed. “If you see a veteran with a history of PTSD, a history of blast TBI, and a history of OSA or some combination of those three, I recommend having a higher index of suspicion [for potential dementia] than for an average person without any of these, even at a younger age than one would ordinarily expect.”

Of all of these factors, the only truly directly modifiable one is sleep disruption, including that caused by OSA or sleep disorders related to PTSD, he added. “Epidemiologic data suggest a connection particularly between midlife sleep disruption and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and so it’s worth thinking about sleep as a modifiable risk factor even as early as the 40s and 50s, whether the patient is or isn’t a veteran.”

Dr. Peskind recommended asking patients, “Do they snore? Do they thrash about during sleep? Do they have trauma nightmares? This will inform the type of intervention required.”

Dr. Alosco added that there is no known “safe” threshold of exposure to blasts, and that thresholds are “unclear, particularly at the individual level.” In American football, there is a dose-response relationship between years of play and risk for later-life neurological disorder. “The best way to mitigate risk is to limit cumulative exposure,” he said.

The study by Li and colleagues was funded by grant funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service and the University of Washington Friends of Alzheimer’s Research. Other sources of funding to individual researchers are listed in the original paper. The study by Braun and colleagues was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service; and the National Institute on Aging. The white paper included studies that received funding from numerous sources, including the National Institutes of Health and the DOD. Dr. Iliff serves as the chair of the Scientific Advisory Board for Applied Cognition Inc., from which he receives compensation and in which he holds an equity stake. In the last year, he served as a paid consultant to Gryphon Biosciences. Dr. Peskind has served as a paid consultant to the companies Genentech, Roche, and Alpha Cognition. Dr. Alosco was supported by grant funding from the NIH; he received research support from Rainwater Charitable Foundation Inc., and Life Molecular Imaging Inc.; he has received a single honorarium from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for services unrelated to this editorial; and he received royalties from Oxford University Press Inc. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original papers.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Are Primary Care Physicians the Answer to the US Headache Neurologist Shortage?

SAN DIEGO —

It is estimated that about 4 million PCP office visits annually are headache related, and that 52.8% of all migraine encounters occur in primary care settings.

However, PCPs aren’t always adequately trained in headache management and referral times to specialist care can be lengthy.

Data published in Headache show only 564 accredited headache specialists practice in the United States, but at least 3700 headache specialists are needed to treat those affected by migraine, with even more needed to address other disabling headache types such as tension-type headache and cluster headache. To keep up with population growth, it is estimated that the United States will require 4500 headache specialists by 2040.

First Contact

To tackle this specialist shortfall, the AHS developed the First Contact program with the aim of improving headache education in primary care and help alleviate at least some of the demand for specialist care.

The national program was rolled out in 2020 and 2021. The educational symposia were delivered to PCPs at multiple locations across the country. The initiative also included a comprehensive website with numerous support resources.

After participating in the initiative, attendees were surveyed about the value of the program, and the results were subsequently analyzed and presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The analysis included 636 survey respondents, a 38% response rate. Almost all participants (96%) were MDs and DOs. The remainder included nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and dentists.

About 85.6% of respondents reported being completely or very confident in their ability to recognize and accurately diagnose headache disorders, and 81.3% said they were completely or very confident in their ability to create tailored treatment plans.

Just over 90% of participants reported they would implement practice changes as a result of the program. The most commonly cited change was the use of diagnostic tools such as the three-question Migraine ID screener, followed closely by consideration of prescribing triptans and reducing the use of unnecessary neuroimaging.

“Overall, there was a positive response to this type of educational programming and interest in ongoing education in addressing headache disorders with both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatment options,” said Nisha Malhotra, MD, a resident at New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York City, who presented the findings at the conference.

The fact that so many general practitioners were keen to use this easy-to-use screen [Migraine ID screener], which can pick up about 90% of people with migraine, is “great,” said study investigator Mia Minen, MD, associate professor and chief of headache research at NYU Langone Health. “I’m pleased primary care providers said they were considering implementing this simple tool.”

However, respondents also cited barriers to change. These included cost constraints (48.9%), insurance reimbursement issues (48.6%), and lack of time (45.3%). Dr. Malhotra noted these concerns are primarily related to workflow rather than knowledge gaps or lack of training.

“This is exciting in that there doesn’t seem to be an issue with education primarily but rather with the logistical issues that exist in the workflow in a primary care setting,” said Dr. Malhotra.

Participants also noted the need for other improvements. For example, they expressed interest in differentiating migraine from other headache types and having a better understanding of how and when to refer to specialists, said Dr. Malhotra.

These practitioners also want to know more about treatment options beyond first-line medications. “They were interested in understanding more advanced medication treatment options beyond just the typical triptan,” said Dr. Malhotra.

In addition, they want to become more skilled in non-pharmaceutical options such as occipital nerve blocks and in massage, acupuncture, and other complementary forms of migraine management, she said.

The study may be vulnerable to sampling bias as survey participants had just attended an educational symposium on headaches. “They were already, to some degree, interested in improving their knowledge on headache,” said Dr. Malhotra.

Another study limitation was that researchers didn’t conduct a pre-survey analysis to determine changes as a result of the symposia. And as the survey was conducted so close to the symposium, “it’s difficult to draw conclusions on the long-term effects,” she added.

“That being said, First Contact is one of the first national initiatives for primary care education, and thus far, it has been very well received.”

The next step is to continue expanding the program and to create a First Contact for women and First Contact for pediatrics, said Dr. Minen.

Improved Diagnosis, Better Care

Commenting on the initiative, Juliana VanderPluym, MD, a headache specialist at the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, who co-chaired the session where the survey results were presented, said it helps address the supply-demand imbalance in headache healthcare.

“Many, many people have headache disorders, and very few people are technically headache specialists, so we have to rely on our colleagues in primary care to help address the great need that’s out there for patients with headache disorders.”

Too many patients don’t get a proper diagnosis or appropriate treatment, said Dr. VanderPluym, so as time passes, “diseases can become more chronic and more refractory, and it affects people’s quality of life and productivity.”

The First Contact program, she said, helps increase providers’ comfort and confidence that they are providing the best patient care possible and lead to a reduction in the need for specialist referrals.

Dr. Minen serves on the First Contact advisory board.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO —

It is estimated that about 4 million PCP office visits annually are headache related, and that 52.8% of all migraine encounters occur in primary care settings.

However, PCPs aren’t always adequately trained in headache management and referral times to specialist care can be lengthy.

Data published in Headache show only 564 accredited headache specialists practice in the United States, but at least 3700 headache specialists are needed to treat those affected by migraine, with even more needed to address other disabling headache types such as tension-type headache and cluster headache. To keep up with population growth, it is estimated that the United States will require 4500 headache specialists by 2040.

First Contact

To tackle this specialist shortfall, the AHS developed the First Contact program with the aim of improving headache education in primary care and help alleviate at least some of the demand for specialist care.

The national program was rolled out in 2020 and 2021. The educational symposia were delivered to PCPs at multiple locations across the country. The initiative also included a comprehensive website with numerous support resources.

After participating in the initiative, attendees were surveyed about the value of the program, and the results were subsequently analyzed and presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The analysis included 636 survey respondents, a 38% response rate. Almost all participants (96%) were MDs and DOs. The remainder included nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and dentists.

About 85.6% of respondents reported being completely or very confident in their ability to recognize and accurately diagnose headache disorders, and 81.3% said they were completely or very confident in their ability to create tailored treatment plans.

Just over 90% of participants reported they would implement practice changes as a result of the program. The most commonly cited change was the use of diagnostic tools such as the three-question Migraine ID screener, followed closely by consideration of prescribing triptans and reducing the use of unnecessary neuroimaging.

“Overall, there was a positive response to this type of educational programming and interest in ongoing education in addressing headache disorders with both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatment options,” said Nisha Malhotra, MD, a resident at New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York City, who presented the findings at the conference.

The fact that so many general practitioners were keen to use this easy-to-use screen [Migraine ID screener], which can pick up about 90% of people with migraine, is “great,” said study investigator Mia Minen, MD, associate professor and chief of headache research at NYU Langone Health. “I’m pleased primary care providers said they were considering implementing this simple tool.”

However, respondents also cited barriers to change. These included cost constraints (48.9%), insurance reimbursement issues (48.6%), and lack of time (45.3%). Dr. Malhotra noted these concerns are primarily related to workflow rather than knowledge gaps or lack of training.

“This is exciting in that there doesn’t seem to be an issue with education primarily but rather with the logistical issues that exist in the workflow in a primary care setting,” said Dr. Malhotra.

Participants also noted the need for other improvements. For example, they expressed interest in differentiating migraine from other headache types and having a better understanding of how and when to refer to specialists, said Dr. Malhotra.

These practitioners also want to know more about treatment options beyond first-line medications. “They were interested in understanding more advanced medication treatment options beyond just the typical triptan,” said Dr. Malhotra.

In addition, they want to become more skilled in non-pharmaceutical options such as occipital nerve blocks and in massage, acupuncture, and other complementary forms of migraine management, she said.

The study may be vulnerable to sampling bias as survey participants had just attended an educational symposium on headaches. “They were already, to some degree, interested in improving their knowledge on headache,” said Dr. Malhotra.

Another study limitation was that researchers didn’t conduct a pre-survey analysis to determine changes as a result of the symposia. And as the survey was conducted so close to the symposium, “it’s difficult to draw conclusions on the long-term effects,” she added.

“That being said, First Contact is one of the first national initiatives for primary care education, and thus far, it has been very well received.”

The next step is to continue expanding the program and to create a First Contact for women and First Contact for pediatrics, said Dr. Minen.

Improved Diagnosis, Better Care

Commenting on the initiative, Juliana VanderPluym, MD, a headache specialist at the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, who co-chaired the session where the survey results were presented, said it helps address the supply-demand imbalance in headache healthcare.

“Many, many people have headache disorders, and very few people are technically headache specialists, so we have to rely on our colleagues in primary care to help address the great need that’s out there for patients with headache disorders.”

Too many patients don’t get a proper diagnosis or appropriate treatment, said Dr. VanderPluym, so as time passes, “diseases can become more chronic and more refractory, and it affects people’s quality of life and productivity.”

The First Contact program, she said, helps increase providers’ comfort and confidence that they are providing the best patient care possible and lead to a reduction in the need for specialist referrals.

Dr. Minen serves on the First Contact advisory board.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO —

It is estimated that about 4 million PCP office visits annually are headache related, and that 52.8% of all migraine encounters occur in primary care settings.

However, PCPs aren’t always adequately trained in headache management and referral times to specialist care can be lengthy.

Data published in Headache show only 564 accredited headache specialists practice in the United States, but at least 3700 headache specialists are needed to treat those affected by migraine, with even more needed to address other disabling headache types such as tension-type headache and cluster headache. To keep up with population growth, it is estimated that the United States will require 4500 headache specialists by 2040.

First Contact

To tackle this specialist shortfall, the AHS developed the First Contact program with the aim of improving headache education in primary care and help alleviate at least some of the demand for specialist care.

The national program was rolled out in 2020 and 2021. The educational symposia were delivered to PCPs at multiple locations across the country. The initiative also included a comprehensive website with numerous support resources.

After participating in the initiative, attendees were surveyed about the value of the program, and the results were subsequently analyzed and presented at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

The analysis included 636 survey respondents, a 38% response rate. Almost all participants (96%) were MDs and DOs. The remainder included nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and dentists.

About 85.6% of respondents reported being completely or very confident in their ability to recognize and accurately diagnose headache disorders, and 81.3% said they were completely or very confident in their ability to create tailored treatment plans.

Just over 90% of participants reported they would implement practice changes as a result of the program. The most commonly cited change was the use of diagnostic tools such as the three-question Migraine ID screener, followed closely by consideration of prescribing triptans and reducing the use of unnecessary neuroimaging.

“Overall, there was a positive response to this type of educational programming and interest in ongoing education in addressing headache disorders with both pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatment options,” said Nisha Malhotra, MD, a resident at New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York City, who presented the findings at the conference.

The fact that so many general practitioners were keen to use this easy-to-use screen [Migraine ID screener], which can pick up about 90% of people with migraine, is “great,” said study investigator Mia Minen, MD, associate professor and chief of headache research at NYU Langone Health. “I’m pleased primary care providers said they were considering implementing this simple tool.”

However, respondents also cited barriers to change. These included cost constraints (48.9%), insurance reimbursement issues (48.6%), and lack of time (45.3%). Dr. Malhotra noted these concerns are primarily related to workflow rather than knowledge gaps or lack of training.

“This is exciting in that there doesn’t seem to be an issue with education primarily but rather with the logistical issues that exist in the workflow in a primary care setting,” said Dr. Malhotra.

Participants also noted the need for other improvements. For example, they expressed interest in differentiating migraine from other headache types and having a better understanding of how and when to refer to specialists, said Dr. Malhotra.

These practitioners also want to know more about treatment options beyond first-line medications. “They were interested in understanding more advanced medication treatment options beyond just the typical triptan,” said Dr. Malhotra.

In addition, they want to become more skilled in non-pharmaceutical options such as occipital nerve blocks and in massage, acupuncture, and other complementary forms of migraine management, she said.

The study may be vulnerable to sampling bias as survey participants had just attended an educational symposium on headaches. “They were already, to some degree, interested in improving their knowledge on headache,” said Dr. Malhotra.

Another study limitation was that researchers didn’t conduct a pre-survey analysis to determine changes as a result of the symposia. And as the survey was conducted so close to the symposium, “it’s difficult to draw conclusions on the long-term effects,” she added.

“That being said, First Contact is one of the first national initiatives for primary care education, and thus far, it has been very well received.”

The next step is to continue expanding the program and to create a First Contact for women and First Contact for pediatrics, said Dr. Minen.

Improved Diagnosis, Better Care

Commenting on the initiative, Juliana VanderPluym, MD, a headache specialist at the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, who co-chaired the session where the survey results were presented, said it helps address the supply-demand imbalance in headache healthcare.

“Many, many people have headache disorders, and very few people are technically headache specialists, so we have to rely on our colleagues in primary care to help address the great need that’s out there for patients with headache disorders.”

Too many patients don’t get a proper diagnosis or appropriate treatment, said Dr. VanderPluym, so as time passes, “diseases can become more chronic and more refractory, and it affects people’s quality of life and productivity.”

The First Contact program, she said, helps increase providers’ comfort and confidence that they are providing the best patient care possible and lead to a reduction in the need for specialist referrals.

Dr. Minen serves on the First Contact advisory board.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AHS 2024

Vision Impairment Tied to Higher Dementia Risk in Older Adults

TOPLINE:

; a decline in contrast sensitivity over time also correlates with the risk of developing dementia.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a longitudinal study to analyze the association of visual function with the risk for dementia in 2159 men and women (mean age, 77.9 years; 54% women) included from the National Health and Aging Trends Study between 2021 and 2022.

- All participants were free from dementia at baseline and underwent visual assessment while wearing their usual glasses or contact lenses.

- Distance and near visual acuity were measured as the log minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) units where higher values indicated worse visual acuity; contrast sensitivity was measured as the log contrast sensitivity (logCS) units where lower values represented worse outcomes.

- Dementia status was determined by a medical diagnosis, a dementia score of 2 or more, or poor performance on cognitive testing.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over the 1-year follow-up period, 192 adults (6.6%) developed dementia.

- Worsening of distant and near vision by 0.1 logMAR increased the risk for dementia by 8% (P = .01) and 7% (P = .02), respectively.

- Each 0.1 logCS decline in baseline contrast sensitivity increased the risk for dementia by 9% (P = .003).

- A yearly decline in contrast sensitivity by 0.1 logCS increased the likelihood of dementia by 14% (P = .007).

- Changes in distant and near vision over time did not show a significant association with risk for dementia (P = .58 and P = .79, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“Visual function, especially contrast sensitivity, might be a risk factor for developing dementia,” the authors wrote. “Early vision screening may help identify adults at higher risk of dementia, allowing for timely interventions.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Louay Almidani, MD, MSc, of the Wilmer Eye Institute at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore, and was published online in the American Journal of Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study had a limited follow-up period of 1 year and may not have captured the long-term association between visual impairment and the risk for dementia. Moreover, the researchers did not consider other visual function measures such as depth perception and visual field, which might have affected the results.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not have any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

; a decline in contrast sensitivity over time also correlates with the risk of developing dementia.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a longitudinal study to analyze the association of visual function with the risk for dementia in 2159 men and women (mean age, 77.9 years; 54% women) included from the National Health and Aging Trends Study between 2021 and 2022.

- All participants were free from dementia at baseline and underwent visual assessment while wearing their usual glasses or contact lenses.

- Distance and near visual acuity were measured as the log minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) units where higher values indicated worse visual acuity; contrast sensitivity was measured as the log contrast sensitivity (logCS) units where lower values represented worse outcomes.

- Dementia status was determined by a medical diagnosis, a dementia score of 2 or more, or poor performance on cognitive testing.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over the 1-year follow-up period, 192 adults (6.6%) developed dementia.

- Worsening of distant and near vision by 0.1 logMAR increased the risk for dementia by 8% (P = .01) and 7% (P = .02), respectively.

- Each 0.1 logCS decline in baseline contrast sensitivity increased the risk for dementia by 9% (P = .003).

- A yearly decline in contrast sensitivity by 0.1 logCS increased the likelihood of dementia by 14% (P = .007).

- Changes in distant and near vision over time did not show a significant association with risk for dementia (P = .58 and P = .79, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“Visual function, especially contrast sensitivity, might be a risk factor for developing dementia,” the authors wrote. “Early vision screening may help identify adults at higher risk of dementia, allowing for timely interventions.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Louay Almidani, MD, MSc, of the Wilmer Eye Institute at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore, and was published online in the American Journal of Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study had a limited follow-up period of 1 year and may not have captured the long-term association between visual impairment and the risk for dementia. Moreover, the researchers did not consider other visual function measures such as depth perception and visual field, which might have affected the results.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not have any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

; a decline in contrast sensitivity over time also correlates with the risk of developing dementia.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a longitudinal study to analyze the association of visual function with the risk for dementia in 2159 men and women (mean age, 77.9 years; 54% women) included from the National Health and Aging Trends Study between 2021 and 2022.

- All participants were free from dementia at baseline and underwent visual assessment while wearing their usual glasses or contact lenses.

- Distance and near visual acuity were measured as the log minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) units where higher values indicated worse visual acuity; contrast sensitivity was measured as the log contrast sensitivity (logCS) units where lower values represented worse outcomes.

- Dementia status was determined by a medical diagnosis, a dementia score of 2 or more, or poor performance on cognitive testing.

TAKEAWAY:

- Over the 1-year follow-up period, 192 adults (6.6%) developed dementia.

- Worsening of distant and near vision by 0.1 logMAR increased the risk for dementia by 8% (P = .01) and 7% (P = .02), respectively.

- Each 0.1 logCS decline in baseline contrast sensitivity increased the risk for dementia by 9% (P = .003).

- A yearly decline in contrast sensitivity by 0.1 logCS increased the likelihood of dementia by 14% (P = .007).

- Changes in distant and near vision over time did not show a significant association with risk for dementia (P = .58 and P = .79, respectively).

IN PRACTICE:

“Visual function, especially contrast sensitivity, might be a risk factor for developing dementia,” the authors wrote. “Early vision screening may help identify adults at higher risk of dementia, allowing for timely interventions.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Louay Almidani, MD, MSc, of the Wilmer Eye Institute at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore, and was published online in the American Journal of Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study had a limited follow-up period of 1 year and may not have captured the long-term association between visual impairment and the risk for dementia. Moreover, the researchers did not consider other visual function measures such as depth perception and visual field, which might have affected the results.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not have any funding source. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Uncommon Locations for Brain Herniations Into Arachnoid Granulations: 5 Cases and Literature Review

The circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is crucial for maintaining homeostasis for the optimal functioning of the multiple complex activities of the brain and spinal cord, including the disposal of metabolic waste products of brain and spinal cord activity into the cerebral venous drainage. Throughout the brain, the arachnoid mater forms small outpouchings or diverticula that penetrate the dura mater and communicate with the dural venous sinuses. These outpuchings are called arachnoid granulations or arachnoid villi, and most are found within the dural sinuses, primarily in the transverse sinuses and superior sagittal sinus, but can occasionally be seen extending into the inner table of the calvarium.1,2

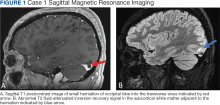

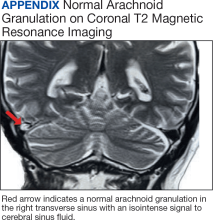

The amount of arachnoid granulations seen in bone, particularly around the superior sagittal sinus, may increase with age.2 Arachnoid granulations are generally small but the largest ones can be seen on gross examination during intracranial procedures or autopsy.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect arachnoid granulations, which are characterized as T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense (CSF isointense), well-circumscribed, small, nonenhancing masses within the dural sinuses or in the diploic space (Figure 1). Even small arachnoid granulations < 1 mm in length can be detected.2

Smaller arachnoid granulations have been described histologically as entirely covered by a dural membrane, thus creating a subdural space that separates the body of the arachnoid granulation from the lumen of the accompanying venous sinus.4 However, larger arachnoid granulations may not be completely covered by a dural membrane, thus creating a point of contact between the arachnoid granulation and the venous sinus.4 Larger arachnoid granulations are normally filled with CSF, and their signal characteristics are similar to CSF on imaging.5,6 Arachnoid granulations also often contain vessels draining into the adjacent venous sinus.5,6

When larger arachnoid granulations are present, they may permit the protrusion of herniated brain tissue. There has been an increasing number of reports of these brain herniations into arachnoid granulations (BHAGs) in the literature.7-10 While these herniations have been associated with nonspecific neurologic symptoms like tinnitus and idiopathic intracranial hypertension, their true clinical significance remains undetermined.10,11 This article presents 5 cases of BHAG, discusses their clinical presentations and image findings, and reviews the current literature.

Case 1

A 30-year-old male with a history of multiple traumatic brain injuries presented for evaluation of seizures. The patient described the semiology of the seizures as a bright, colorful light in his right visual field, followed by loss of vision, then loss of awareness and full body convulsion. The semiology of this patient’s seizures was consistent with left temporo-occipital lobe seizure. The only abnormality seen in the brain MRI was the herniation of brain parenchyma originating from the occipital lobe into the transverse sinus, presumably through an arachnoid granulation (Figure 1). An electroencephalogram (EEG) was unremarkable, though the semiology of the seizure historically described by the patient was localized to the area of BHAG. The patient is currently taking antiseizure medications and has experienced no additional seizures.

Case 2

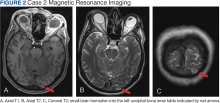

A male aged 53 years with a history of peripheral artery disease presented with a 6-month history of headaches and dizziness. The patient reported the onset of visual aura to his right visual field, starting as a fingernail-sized scintillating kaleidoscope light that would gradually increase in size to a round shape with fading kaleidoscope colors. This episode would last for a few minutes and was immediately followed by a headache. There was no alteration of consciousness during visual aura, although sometimes the patient would have right-sided scalp tingling. These episodes were often unprovoked, but occasionally triggered by bright lights. A single routine EEG was unremarkable. The patient reported headaches without aura, but not aura without headaches, which made occipital lobe seizure less likely. MRI demonstrated a small herniation of brain parenchyma into the inner table of the left occipital bone (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with migraine with aura, and the semiology of the visual aura corresponded to the location of the herniation in the left occipital region.

Case 3

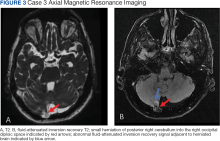

A 77-year-old male with a history of left ear diving injury presented with left-sided asymmetric hearing loss and word recognition difficulty for several years. MRI obtained as part of his work-up to evaluate for possible schwannoma of the eighth left cranial nerve instead demonstrated an incidental right cerebellar herniation within an arachnoid granulation into the diploic space of the occipital bone (Figure 3). The BHAG for this patient appeared to be an incidental finding unrelated to his asymmetric hearing loss.

Case 4

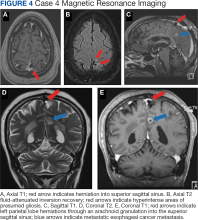

A male aged 62 years with a history of metastatic esophageal cancer, substance abuse, and a prior presumed alcohol withdrawal seizure underwent an MRI for evaluation of brain metastasis after presenting to the hospital with confusion 1 day after starting chemotherapy (Figure 4). Nine years prior, the patient had an isolated generalized tonic-clonic seizure approximately 72 hours following a period of alcohol cessation. The MRI demonstrated an incidental left parasagittal herniation of left parietal lobe tissue through an arachnoid granulation into the superior sagittal sinus, in addition to metastatic brain lesions. An EEG showed mild encephalopathy without evidence of seizures. It was determined that the patient's confusion was most likely due to toxic-metabolic encephalopathy from chemotherapy.

Case 5

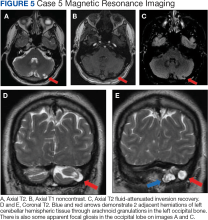

A 51-year-old male presented with worsening headache severity and frequency. He had a history of chronic headaches for about 20 years that occurred annually, but were now occurring twice weekly. The headaches often started with a left eye visual aura followed by pressure in the left eye, left frontal region, and left ear, with at times a cervicogenic component. No cervical spine imaging was available. An MRI revealed 2 small adjacent areas of cerebellar herniation into arachnoid granulations in the left occipital bone (Figure 5).

Discussion