User login

Skin imaging working group releases first guidelines for AI algorithms used in dermatology

The

The guidelines, published in JAMA Dermatology on Dec. 1, 2021, contain a broad range of recommendations stakeholders should consider when developing and assessing image-based AI algorithms in dermatology. The recommendations are divided into categories of data, technique, technical assessment, and application. ISIC is “an academia and industry partnership designed to facilitate the application of digital skin imaging to help reduce melanoma mortality,” and is organized into different working groups, including the AI working group, according to its website.

“Our goal with these guidelines was to create higher-quality reporting of dataset and algorithm characteristics for dermatology AI,” first author Roxana Daneshjou, MD, PhD, clinical scholar in dermatology, in the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “We hope these guidelines also aid regulatory bodies around the world when they are assessing algorithms to be used in dermatology.”

Recommendations for data

The authors recommended that datasets used by AI algorithms have image descriptions and details on image artifacts. “For photography, these include the type of camera used; whether images were taken under standardized or varying conditions; whether they were taken by professional photographers, laymen, or health care professionals; and image quality,” they wrote. They also recommended that developers include in an image description the type of lighting used and whether the photo contains pen markings, hair, tattoos, injuries, surgical effects, or other “physical perturbations.”

Exchangeable image file format data obtained from the camera, and preprocessing procedures like color normalization and “postprocessing” of images, such as filtering, should also be disclosed. In addition, developers should disclose and justify inclusion of images that have been created by an algorithm within a dataset. Any public images used in the datasets should have references, and privately used images should be made public where possible, the authors said.

The ISIC working group guidelines also provided recommendations for patient-level metadata. Each image should include a patient’s geographical location and medical center they visited as well as their age, sex and gender, ethnicity and/or race, and skin tone. Dr. Daneshjou said this was one area where she and her colleagues found a lack of transparency in AI datasets in algorithms in a recent review. “We found that many AI papers provided sparse details about the images used to train and test their algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou explained. “For example, only 7 out of 70 papers had any information about the skin tones in the images used for developing and/or testing AI algorithms. Understanding the diversity of images used to train and test algorithms is important because algorithms that are developed on images of predominantly white skin likely won’t work as well on Black and brown skin.”

The guideline authors also asked algorithm developers to describe the limitations of not including patient-level metadata information when it is incomplete or unavailable. In addition, “we ask that algorithm developers comment on potential biases of their algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “For example, an algorithm based only on telemedicine images may not capture the full range of diseases seen within an in-person clinic.”

When describing their AI algorithm, developers should detail their reasoning for the dataset size and partitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria for images, and use of any external samples for test sets. “Authors should consider any differences between the image characteristics used for algorithm development and those that might be encountered in the real world,” the guidelines stated.

Recommendations for technique

How the images in a dataset are labeled is a unique challenge in developing AI algorithms for dermatology, the authors noted. Developers should use histopathological diagnosis in their labeling, but this can sometimes result in label noise.

“Many of the AI algorithms in dermatology use supervised learning, which requires labeled examples to help the algorithm ‘learn’ features for discriminating between lesions. We found that some papers use consensus labeling – dermatologists providing a label – to label skin cancers; however, the standard for diagnosing skin cancer is using histopathology from a biopsy,” she said. “Dermatologists can biopsy seven to eight suspected melanomas before discovering a true melanoma, so dermatologist labeling of skin cancers is prone to label noise.”

ISIC’s guidelines stated a gold standard of labeling for dermatologic images is one area that still needs future research, but currently, “diagnoses, labels and diagnostic groups used in data repositories as well as public ontologies” such as ICD-11, AnatomyMapper, and SNOMED-CT should be included in dermatologic image datasets.

AI developers should also provide a detailed description of their algorithm, which includes methods, work flows, mathematical formulas as well as the generalizability of the algorithm across more than one dataset.

Recommendations for technical assessment

“Another important recommendation is that algorithm developers should provide a way for algorithms to be publicly evaluable by researchers,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “Many dermatology AI algorithms do not share either their data or their algorithm. Algorithm sharing is important for assessing reproducibility and robustness.”

Google’s recently announced AI-powered dermatology assistant tool, for example, “has made claims about its accuracy and ability to diagnose skin disease at a dermatologist level, but there is no way for researchers to independently test these claims,” she said. Other options like Model Dermatology, developed by Seung Seog Han, MD, PhD, of the Dermatology Clinic in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues, offer an application programming interface “that allows researchers to test the algorithm,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “This kind of openness is key for assessing algorithm robustness.”

Developers should also note in their algorithm explanations how performance markers and benchmarks would translate to proposed clinical application. “In this context,” the use case – the context in which the AI application is being used – “should be clearly described – who are the intended users and under what clinical scenario are they using the algorithm,” the authors wrote.

Recommendations for application

The guidelines note that use case for the model should also be described by the AI developers. “Our checklist includes delineating use cases for algorithms and describing what use cases may be within the scope of the algorithm versus which use cases are out of scope,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “For example, an algorithm developed to provide decision support to dermatologists, with a human in the loop, may not be accurate enough to release directly to consumers.”

As the goal of AI algorithms in dermatology is eventual implementation for clinicians and patients, the authors asked developers to consider shortcomings and potential harms of the algorithm during implementation. “Ethical considerations and impact on vulnerable populations should also be considered and discussed,” they wrote. An algorithm “suggesting aesthetic medical treatments may have negative effects given the biased nature of beauty standards,” and “an algorithm that diagnoses basal cell carcinomas but lacks any pigmented basal cell carcinomas, which are more often seen in skin of color, will not perform equitably across populations.”

Prior to implementing an AI algorithm, the ISIC working group recommended developers perform prospective clinical trials for validation. Checklists and guidelines like SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI “provide guidance on how to design clinical trials to test AI algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou said.

After implementation, “I believe we need additional research in how we monitor algorithms after they are deployed clinically, Dr. Daneshjou said. “Currently there are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved AI algorithms in dermatology; however, there are several applications that have CE mark in Europe, and there are no mechanisms for postmarket surveillance there.

'Timely' recommendations

Commenting on the ISIC working group guidelines, Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, director and chief of medical dermatology for Stanford Health Care, who was not involved with the work, said that the recommendations are timely and provide “a framework for a ‘common language’ around AI datasets specifically tailored to dermatology.” Dr. Ko, chair of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Ad Hoc Task Force on Augmented Intelligence, noted the work by Dr. Daneshjou and colleagues “is consistent with and builds further details” on the position statement released by the AAD AI task force in 2019.

“As machine-learning capabilities and commercial efforts continue to mature, it becomes increasingly important that we are able to ‘look under the hood,’ and evaluate all the critical factors that influence development of these capabilities,” he said in an interview. “A standard set of reporting guidelines not only allows for transparency in evaluating data and performance of models and algorithms, but also forces the consideration of issues of equity, fairness, mitigation of bias, and clinically meaningful outcomes.”

One concern is the impact of AI algorithms on societal or health systems, he noted, which is brought up in the guidelines. “The last thing we would want is the development of robust AI systems that exacerbate access challenges, or generate patient anxiety/worry, or drive low-value utilization, or adds to care team burden, or create a technological barrier to care, or increases inequity in dermatologic care,” he said.

In developing AI algorithms for dermatology, a “major practical issue” is how performance on paper will translate to real-world use, Dr. Ko explained, and the ISIC guidelines “provide a critical step in empowering clinicians, practices, and our field to shape the advent of the AI and augmented intelligence tools and systems to promote and enhance meaningful clinical outcomes, and augment the core patient-clinician relationship and ensure they are grounded in principles of fairness, equity and transparency.”

This research was funded by awards and grants to individual authors from the Charina Fund, a Google Research Award, Melanoma Research Alliance, National Health and Medical Research Council, National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, National Science Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors disclosed relationships with governmental entities, pharmaceutical companies, technology startups, medical publishers, charitable trusts, consulting firms, dermatology training companies, providers of medical devices, manufacturers of dermatologic products, and other organizations related to the paper in the form of supplied equipment, having founded a company; receiving grants, patents, or personal fees; holding shares; and medical reporting. Dr. Ko reported that he serves as a clinical advisor for Skin Analytics, and has an ongoing research collaboration with Google.

The

The guidelines, published in JAMA Dermatology on Dec. 1, 2021, contain a broad range of recommendations stakeholders should consider when developing and assessing image-based AI algorithms in dermatology. The recommendations are divided into categories of data, technique, technical assessment, and application. ISIC is “an academia and industry partnership designed to facilitate the application of digital skin imaging to help reduce melanoma mortality,” and is organized into different working groups, including the AI working group, according to its website.

“Our goal with these guidelines was to create higher-quality reporting of dataset and algorithm characteristics for dermatology AI,” first author Roxana Daneshjou, MD, PhD, clinical scholar in dermatology, in the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “We hope these guidelines also aid regulatory bodies around the world when they are assessing algorithms to be used in dermatology.”

Recommendations for data

The authors recommended that datasets used by AI algorithms have image descriptions and details on image artifacts. “For photography, these include the type of camera used; whether images were taken under standardized or varying conditions; whether they were taken by professional photographers, laymen, or health care professionals; and image quality,” they wrote. They also recommended that developers include in an image description the type of lighting used and whether the photo contains pen markings, hair, tattoos, injuries, surgical effects, or other “physical perturbations.”

Exchangeable image file format data obtained from the camera, and preprocessing procedures like color normalization and “postprocessing” of images, such as filtering, should also be disclosed. In addition, developers should disclose and justify inclusion of images that have been created by an algorithm within a dataset. Any public images used in the datasets should have references, and privately used images should be made public where possible, the authors said.

The ISIC working group guidelines also provided recommendations for patient-level metadata. Each image should include a patient’s geographical location and medical center they visited as well as their age, sex and gender, ethnicity and/or race, and skin tone. Dr. Daneshjou said this was one area where she and her colleagues found a lack of transparency in AI datasets in algorithms in a recent review. “We found that many AI papers provided sparse details about the images used to train and test their algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou explained. “For example, only 7 out of 70 papers had any information about the skin tones in the images used for developing and/or testing AI algorithms. Understanding the diversity of images used to train and test algorithms is important because algorithms that are developed on images of predominantly white skin likely won’t work as well on Black and brown skin.”

The guideline authors also asked algorithm developers to describe the limitations of not including patient-level metadata information when it is incomplete or unavailable. In addition, “we ask that algorithm developers comment on potential biases of their algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “For example, an algorithm based only on telemedicine images may not capture the full range of diseases seen within an in-person clinic.”

When describing their AI algorithm, developers should detail their reasoning for the dataset size and partitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria for images, and use of any external samples for test sets. “Authors should consider any differences between the image characteristics used for algorithm development and those that might be encountered in the real world,” the guidelines stated.

Recommendations for technique

How the images in a dataset are labeled is a unique challenge in developing AI algorithms for dermatology, the authors noted. Developers should use histopathological diagnosis in their labeling, but this can sometimes result in label noise.

“Many of the AI algorithms in dermatology use supervised learning, which requires labeled examples to help the algorithm ‘learn’ features for discriminating between lesions. We found that some papers use consensus labeling – dermatologists providing a label – to label skin cancers; however, the standard for diagnosing skin cancer is using histopathology from a biopsy,” she said. “Dermatologists can biopsy seven to eight suspected melanomas before discovering a true melanoma, so dermatologist labeling of skin cancers is prone to label noise.”

ISIC’s guidelines stated a gold standard of labeling for dermatologic images is one area that still needs future research, but currently, “diagnoses, labels and diagnostic groups used in data repositories as well as public ontologies” such as ICD-11, AnatomyMapper, and SNOMED-CT should be included in dermatologic image datasets.

AI developers should also provide a detailed description of their algorithm, which includes methods, work flows, mathematical formulas as well as the generalizability of the algorithm across more than one dataset.

Recommendations for technical assessment

“Another important recommendation is that algorithm developers should provide a way for algorithms to be publicly evaluable by researchers,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “Many dermatology AI algorithms do not share either their data or their algorithm. Algorithm sharing is important for assessing reproducibility and robustness.”

Google’s recently announced AI-powered dermatology assistant tool, for example, “has made claims about its accuracy and ability to diagnose skin disease at a dermatologist level, but there is no way for researchers to independently test these claims,” she said. Other options like Model Dermatology, developed by Seung Seog Han, MD, PhD, of the Dermatology Clinic in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues, offer an application programming interface “that allows researchers to test the algorithm,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “This kind of openness is key for assessing algorithm robustness.”

Developers should also note in their algorithm explanations how performance markers and benchmarks would translate to proposed clinical application. “In this context,” the use case – the context in which the AI application is being used – “should be clearly described – who are the intended users and under what clinical scenario are they using the algorithm,” the authors wrote.

Recommendations for application

The guidelines note that use case for the model should also be described by the AI developers. “Our checklist includes delineating use cases for algorithms and describing what use cases may be within the scope of the algorithm versus which use cases are out of scope,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “For example, an algorithm developed to provide decision support to dermatologists, with a human in the loop, may not be accurate enough to release directly to consumers.”

As the goal of AI algorithms in dermatology is eventual implementation for clinicians and patients, the authors asked developers to consider shortcomings and potential harms of the algorithm during implementation. “Ethical considerations and impact on vulnerable populations should also be considered and discussed,” they wrote. An algorithm “suggesting aesthetic medical treatments may have negative effects given the biased nature of beauty standards,” and “an algorithm that diagnoses basal cell carcinomas but lacks any pigmented basal cell carcinomas, which are more often seen in skin of color, will not perform equitably across populations.”

Prior to implementing an AI algorithm, the ISIC working group recommended developers perform prospective clinical trials for validation. Checklists and guidelines like SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI “provide guidance on how to design clinical trials to test AI algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou said.

After implementation, “I believe we need additional research in how we monitor algorithms after they are deployed clinically, Dr. Daneshjou said. “Currently there are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved AI algorithms in dermatology; however, there are several applications that have CE mark in Europe, and there are no mechanisms for postmarket surveillance there.

'Timely' recommendations

Commenting on the ISIC working group guidelines, Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, director and chief of medical dermatology for Stanford Health Care, who was not involved with the work, said that the recommendations are timely and provide “a framework for a ‘common language’ around AI datasets specifically tailored to dermatology.” Dr. Ko, chair of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Ad Hoc Task Force on Augmented Intelligence, noted the work by Dr. Daneshjou and colleagues “is consistent with and builds further details” on the position statement released by the AAD AI task force in 2019.

“As machine-learning capabilities and commercial efforts continue to mature, it becomes increasingly important that we are able to ‘look under the hood,’ and evaluate all the critical factors that influence development of these capabilities,” he said in an interview. “A standard set of reporting guidelines not only allows for transparency in evaluating data and performance of models and algorithms, but also forces the consideration of issues of equity, fairness, mitigation of bias, and clinically meaningful outcomes.”

One concern is the impact of AI algorithms on societal or health systems, he noted, which is brought up in the guidelines. “The last thing we would want is the development of robust AI systems that exacerbate access challenges, or generate patient anxiety/worry, or drive low-value utilization, or adds to care team burden, or create a technological barrier to care, or increases inequity in dermatologic care,” he said.

In developing AI algorithms for dermatology, a “major practical issue” is how performance on paper will translate to real-world use, Dr. Ko explained, and the ISIC guidelines “provide a critical step in empowering clinicians, practices, and our field to shape the advent of the AI and augmented intelligence tools and systems to promote and enhance meaningful clinical outcomes, and augment the core patient-clinician relationship and ensure they are grounded in principles of fairness, equity and transparency.”

This research was funded by awards and grants to individual authors from the Charina Fund, a Google Research Award, Melanoma Research Alliance, National Health and Medical Research Council, National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, National Science Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors disclosed relationships with governmental entities, pharmaceutical companies, technology startups, medical publishers, charitable trusts, consulting firms, dermatology training companies, providers of medical devices, manufacturers of dermatologic products, and other organizations related to the paper in the form of supplied equipment, having founded a company; receiving grants, patents, or personal fees; holding shares; and medical reporting. Dr. Ko reported that he serves as a clinical advisor for Skin Analytics, and has an ongoing research collaboration with Google.

The

The guidelines, published in JAMA Dermatology on Dec. 1, 2021, contain a broad range of recommendations stakeholders should consider when developing and assessing image-based AI algorithms in dermatology. The recommendations are divided into categories of data, technique, technical assessment, and application. ISIC is “an academia and industry partnership designed to facilitate the application of digital skin imaging to help reduce melanoma mortality,” and is organized into different working groups, including the AI working group, according to its website.

“Our goal with these guidelines was to create higher-quality reporting of dataset and algorithm characteristics for dermatology AI,” first author Roxana Daneshjou, MD, PhD, clinical scholar in dermatology, in the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “We hope these guidelines also aid regulatory bodies around the world when they are assessing algorithms to be used in dermatology.”

Recommendations for data

The authors recommended that datasets used by AI algorithms have image descriptions and details on image artifacts. “For photography, these include the type of camera used; whether images were taken under standardized or varying conditions; whether they were taken by professional photographers, laymen, or health care professionals; and image quality,” they wrote. They also recommended that developers include in an image description the type of lighting used and whether the photo contains pen markings, hair, tattoos, injuries, surgical effects, or other “physical perturbations.”

Exchangeable image file format data obtained from the camera, and preprocessing procedures like color normalization and “postprocessing” of images, such as filtering, should also be disclosed. In addition, developers should disclose and justify inclusion of images that have been created by an algorithm within a dataset. Any public images used in the datasets should have references, and privately used images should be made public where possible, the authors said.

The ISIC working group guidelines also provided recommendations for patient-level metadata. Each image should include a patient’s geographical location and medical center they visited as well as their age, sex and gender, ethnicity and/or race, and skin tone. Dr. Daneshjou said this was one area where she and her colleagues found a lack of transparency in AI datasets in algorithms in a recent review. “We found that many AI papers provided sparse details about the images used to train and test their algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou explained. “For example, only 7 out of 70 papers had any information about the skin tones in the images used for developing and/or testing AI algorithms. Understanding the diversity of images used to train and test algorithms is important because algorithms that are developed on images of predominantly white skin likely won’t work as well on Black and brown skin.”

The guideline authors also asked algorithm developers to describe the limitations of not including patient-level metadata information when it is incomplete or unavailable. In addition, “we ask that algorithm developers comment on potential biases of their algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “For example, an algorithm based only on telemedicine images may not capture the full range of diseases seen within an in-person clinic.”

When describing their AI algorithm, developers should detail their reasoning for the dataset size and partitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria for images, and use of any external samples for test sets. “Authors should consider any differences between the image characteristics used for algorithm development and those that might be encountered in the real world,” the guidelines stated.

Recommendations for technique

How the images in a dataset are labeled is a unique challenge in developing AI algorithms for dermatology, the authors noted. Developers should use histopathological diagnosis in their labeling, but this can sometimes result in label noise.

“Many of the AI algorithms in dermatology use supervised learning, which requires labeled examples to help the algorithm ‘learn’ features for discriminating between lesions. We found that some papers use consensus labeling – dermatologists providing a label – to label skin cancers; however, the standard for diagnosing skin cancer is using histopathology from a biopsy,” she said. “Dermatologists can biopsy seven to eight suspected melanomas before discovering a true melanoma, so dermatologist labeling of skin cancers is prone to label noise.”

ISIC’s guidelines stated a gold standard of labeling for dermatologic images is one area that still needs future research, but currently, “diagnoses, labels and diagnostic groups used in data repositories as well as public ontologies” such as ICD-11, AnatomyMapper, and SNOMED-CT should be included in dermatologic image datasets.

AI developers should also provide a detailed description of their algorithm, which includes methods, work flows, mathematical formulas as well as the generalizability of the algorithm across more than one dataset.

Recommendations for technical assessment

“Another important recommendation is that algorithm developers should provide a way for algorithms to be publicly evaluable by researchers,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “Many dermatology AI algorithms do not share either their data or their algorithm. Algorithm sharing is important for assessing reproducibility and robustness.”

Google’s recently announced AI-powered dermatology assistant tool, for example, “has made claims about its accuracy and ability to diagnose skin disease at a dermatologist level, but there is no way for researchers to independently test these claims,” she said. Other options like Model Dermatology, developed by Seung Seog Han, MD, PhD, of the Dermatology Clinic in Seoul, South Korea, and colleagues, offer an application programming interface “that allows researchers to test the algorithm,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “This kind of openness is key for assessing algorithm robustness.”

Developers should also note in their algorithm explanations how performance markers and benchmarks would translate to proposed clinical application. “In this context,” the use case – the context in which the AI application is being used – “should be clearly described – who are the intended users and under what clinical scenario are they using the algorithm,” the authors wrote.

Recommendations for application

The guidelines note that use case for the model should also be described by the AI developers. “Our checklist includes delineating use cases for algorithms and describing what use cases may be within the scope of the algorithm versus which use cases are out of scope,” Dr. Daneshjou said. “For example, an algorithm developed to provide decision support to dermatologists, with a human in the loop, may not be accurate enough to release directly to consumers.”

As the goal of AI algorithms in dermatology is eventual implementation for clinicians and patients, the authors asked developers to consider shortcomings and potential harms of the algorithm during implementation. “Ethical considerations and impact on vulnerable populations should also be considered and discussed,” they wrote. An algorithm “suggesting aesthetic medical treatments may have negative effects given the biased nature of beauty standards,” and “an algorithm that diagnoses basal cell carcinomas but lacks any pigmented basal cell carcinomas, which are more often seen in skin of color, will not perform equitably across populations.”

Prior to implementing an AI algorithm, the ISIC working group recommended developers perform prospective clinical trials for validation. Checklists and guidelines like SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI “provide guidance on how to design clinical trials to test AI algorithms,” Dr. Daneshjou said.

After implementation, “I believe we need additional research in how we monitor algorithms after they are deployed clinically, Dr. Daneshjou said. “Currently there are no [Food and Drug Administration]–approved AI algorithms in dermatology; however, there are several applications that have CE mark in Europe, and there are no mechanisms for postmarket surveillance there.

'Timely' recommendations

Commenting on the ISIC working group guidelines, Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, director and chief of medical dermatology for Stanford Health Care, who was not involved with the work, said that the recommendations are timely and provide “a framework for a ‘common language’ around AI datasets specifically tailored to dermatology.” Dr. Ko, chair of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Ad Hoc Task Force on Augmented Intelligence, noted the work by Dr. Daneshjou and colleagues “is consistent with and builds further details” on the position statement released by the AAD AI task force in 2019.

“As machine-learning capabilities and commercial efforts continue to mature, it becomes increasingly important that we are able to ‘look under the hood,’ and evaluate all the critical factors that influence development of these capabilities,” he said in an interview. “A standard set of reporting guidelines not only allows for transparency in evaluating data and performance of models and algorithms, but also forces the consideration of issues of equity, fairness, mitigation of bias, and clinically meaningful outcomes.”

One concern is the impact of AI algorithms on societal or health systems, he noted, which is brought up in the guidelines. “The last thing we would want is the development of robust AI systems that exacerbate access challenges, or generate patient anxiety/worry, or drive low-value utilization, or adds to care team burden, or create a technological barrier to care, or increases inequity in dermatologic care,” he said.

In developing AI algorithms for dermatology, a “major practical issue” is how performance on paper will translate to real-world use, Dr. Ko explained, and the ISIC guidelines “provide a critical step in empowering clinicians, practices, and our field to shape the advent of the AI and augmented intelligence tools and systems to promote and enhance meaningful clinical outcomes, and augment the core patient-clinician relationship and ensure they are grounded in principles of fairness, equity and transparency.”

This research was funded by awards and grants to individual authors from the Charina Fund, a Google Research Award, Melanoma Research Alliance, National Health and Medical Research Council, National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute, National Science Foundation, and the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors disclosed relationships with governmental entities, pharmaceutical companies, technology startups, medical publishers, charitable trusts, consulting firms, dermatology training companies, providers of medical devices, manufacturers of dermatologic products, and other organizations related to the paper in the form of supplied equipment, having founded a company; receiving grants, patents, or personal fees; holding shares; and medical reporting. Dr. Ko reported that he serves as a clinical advisor for Skin Analytics, and has an ongoing research collaboration with Google.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Elevated mortality seen in Merkel cell patients from rural areas

This paradox was discovered in an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program that primary author Bryan T. Carroll, MD, PhD, and colleagues presented during a virtual abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

“MCC is a rare and aggressive neoplasm of the skin with high mortality,” said coauthor Emma Larson, MD, a dermatology clinical research fellow at University Hospitals of Cleveland. “Previous studies have demonstrated that MCC survival is lower in low–dermatologist density areas. Associations are difficult to characterize without historical staging data aggregated from large registries. We hypothesized that decreased MCC survival is associated with rural counties.”

The researchers used 18 registries from the November 2019 SEER database to retrospectively evaluate adults who were diagnosed with MCC between 2004 and 2015 as confirmed by positive histology. Study endpoints were SEER historic stage at diagnosis and 5-year survival. MCC cases were stratified by 2013 USDA urban-rural continuum codes, which defines metropolitan counties as those with a population of 1 million or more, urban counties as those with a population of less than 1 million, and rural counties as nonmetropolitan counties not adjacent to a metropolitan area.

A total of 6,291 cases with a mean age of 75 years were included in the final analysis: 3,750 from metro areas, 2,235 from urban areas, and 306 from rural areas. A higher proportion of MCC patients from rural areas were male (69% vs. 62% from metro areas and 64% from urban areas) and white (97% vs. 95% and 96%, respectively). “This may contribute to differences in MCC care,” Dr. Larson said. “However, we also found that there is an increased incidence of locally staged disease in rural areas (51%) than in metro (44%) or urban (45%) areas (P = .02). In addition, fewer lymph node surgeries were performed in rural (50%) and urban (51%) areas than in metro areas (45%; P = .01).”

Overall survival was worse among patients in rural areas (a mean of 34 months), compared with those in urban (a mean of 41 months) and metro areas (a mean of 47 months; P = .02). “This may be due to the fact that rural counties have the higher risk factors for MCC incidence and death, but when we account for the confounders, including sex, age, race, and MCC stage, we still found a difference in overall survival in rural counties, compared to metro and urban counties,” Dr. Larson said.

Dr. Carroll, an associate professor of dermatology at University Hospitals of Cleveland, characterized the finding as “not what you’d expect with a higher incidence of local disease. Therefore, there is the potential for mis-staging in rural counties, where we did see that the interrogation of lymph nodes was done less frequently than in urban centers, which were more aligned with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines during this time period. Still, after correction, rural location is still associated with a higher MCC mortality. There is a need for us to further interrogate what the causes are for this disparity in care between rural and urban centers.”

The other study authors were Dustin DeMeo and Christian Scheufele, MD. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

This paradox was discovered in an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program that primary author Bryan T. Carroll, MD, PhD, and colleagues presented during a virtual abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

“MCC is a rare and aggressive neoplasm of the skin with high mortality,” said coauthor Emma Larson, MD, a dermatology clinical research fellow at University Hospitals of Cleveland. “Previous studies have demonstrated that MCC survival is lower in low–dermatologist density areas. Associations are difficult to characterize without historical staging data aggregated from large registries. We hypothesized that decreased MCC survival is associated with rural counties.”

The researchers used 18 registries from the November 2019 SEER database to retrospectively evaluate adults who were diagnosed with MCC between 2004 and 2015 as confirmed by positive histology. Study endpoints were SEER historic stage at diagnosis and 5-year survival. MCC cases were stratified by 2013 USDA urban-rural continuum codes, which defines metropolitan counties as those with a population of 1 million or more, urban counties as those with a population of less than 1 million, and rural counties as nonmetropolitan counties not adjacent to a metropolitan area.

A total of 6,291 cases with a mean age of 75 years were included in the final analysis: 3,750 from metro areas, 2,235 from urban areas, and 306 from rural areas. A higher proportion of MCC patients from rural areas were male (69% vs. 62% from metro areas and 64% from urban areas) and white (97% vs. 95% and 96%, respectively). “This may contribute to differences in MCC care,” Dr. Larson said. “However, we also found that there is an increased incidence of locally staged disease in rural areas (51%) than in metro (44%) or urban (45%) areas (P = .02). In addition, fewer lymph node surgeries were performed in rural (50%) and urban (51%) areas than in metro areas (45%; P = .01).”

Overall survival was worse among patients in rural areas (a mean of 34 months), compared with those in urban (a mean of 41 months) and metro areas (a mean of 47 months; P = .02). “This may be due to the fact that rural counties have the higher risk factors for MCC incidence and death, but when we account for the confounders, including sex, age, race, and MCC stage, we still found a difference in overall survival in rural counties, compared to metro and urban counties,” Dr. Larson said.

Dr. Carroll, an associate professor of dermatology at University Hospitals of Cleveland, characterized the finding as “not what you’d expect with a higher incidence of local disease. Therefore, there is the potential for mis-staging in rural counties, where we did see that the interrogation of lymph nodes was done less frequently than in urban centers, which were more aligned with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines during this time period. Still, after correction, rural location is still associated with a higher MCC mortality. There is a need for us to further interrogate what the causes are for this disparity in care between rural and urban centers.”

The other study authors were Dustin DeMeo and Christian Scheufele, MD. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

This paradox was discovered in an analysis of data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program that primary author Bryan T. Carroll, MD, PhD, and colleagues presented during a virtual abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

“MCC is a rare and aggressive neoplasm of the skin with high mortality,” said coauthor Emma Larson, MD, a dermatology clinical research fellow at University Hospitals of Cleveland. “Previous studies have demonstrated that MCC survival is lower in low–dermatologist density areas. Associations are difficult to characterize without historical staging data aggregated from large registries. We hypothesized that decreased MCC survival is associated with rural counties.”

The researchers used 18 registries from the November 2019 SEER database to retrospectively evaluate adults who were diagnosed with MCC between 2004 and 2015 as confirmed by positive histology. Study endpoints were SEER historic stage at diagnosis and 5-year survival. MCC cases were stratified by 2013 USDA urban-rural continuum codes, which defines metropolitan counties as those with a population of 1 million or more, urban counties as those with a population of less than 1 million, and rural counties as nonmetropolitan counties not adjacent to a metropolitan area.

A total of 6,291 cases with a mean age of 75 years were included in the final analysis: 3,750 from metro areas, 2,235 from urban areas, and 306 from rural areas. A higher proportion of MCC patients from rural areas were male (69% vs. 62% from metro areas and 64% from urban areas) and white (97% vs. 95% and 96%, respectively). “This may contribute to differences in MCC care,” Dr. Larson said. “However, we also found that there is an increased incidence of locally staged disease in rural areas (51%) than in metro (44%) or urban (45%) areas (P = .02). In addition, fewer lymph node surgeries were performed in rural (50%) and urban (51%) areas than in metro areas (45%; P = .01).”

Overall survival was worse among patients in rural areas (a mean of 34 months), compared with those in urban (a mean of 41 months) and metro areas (a mean of 47 months; P = .02). “This may be due to the fact that rural counties have the higher risk factors for MCC incidence and death, but when we account for the confounders, including sex, age, race, and MCC stage, we still found a difference in overall survival in rural counties, compared to metro and urban counties,” Dr. Larson said.

Dr. Carroll, an associate professor of dermatology at University Hospitals of Cleveland, characterized the finding as “not what you’d expect with a higher incidence of local disease. Therefore, there is the potential for mis-staging in rural counties, where we did see that the interrogation of lymph nodes was done less frequently than in urban centers, which were more aligned with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines during this time period. Still, after correction, rural location is still associated with a higher MCC mortality. There is a need for us to further interrogate what the causes are for this disparity in care between rural and urban centers.”

The other study authors were Dustin DeMeo and Christian Scheufele, MD. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ASDS 2021

Multiple Lesions With Recurrent Bleeding

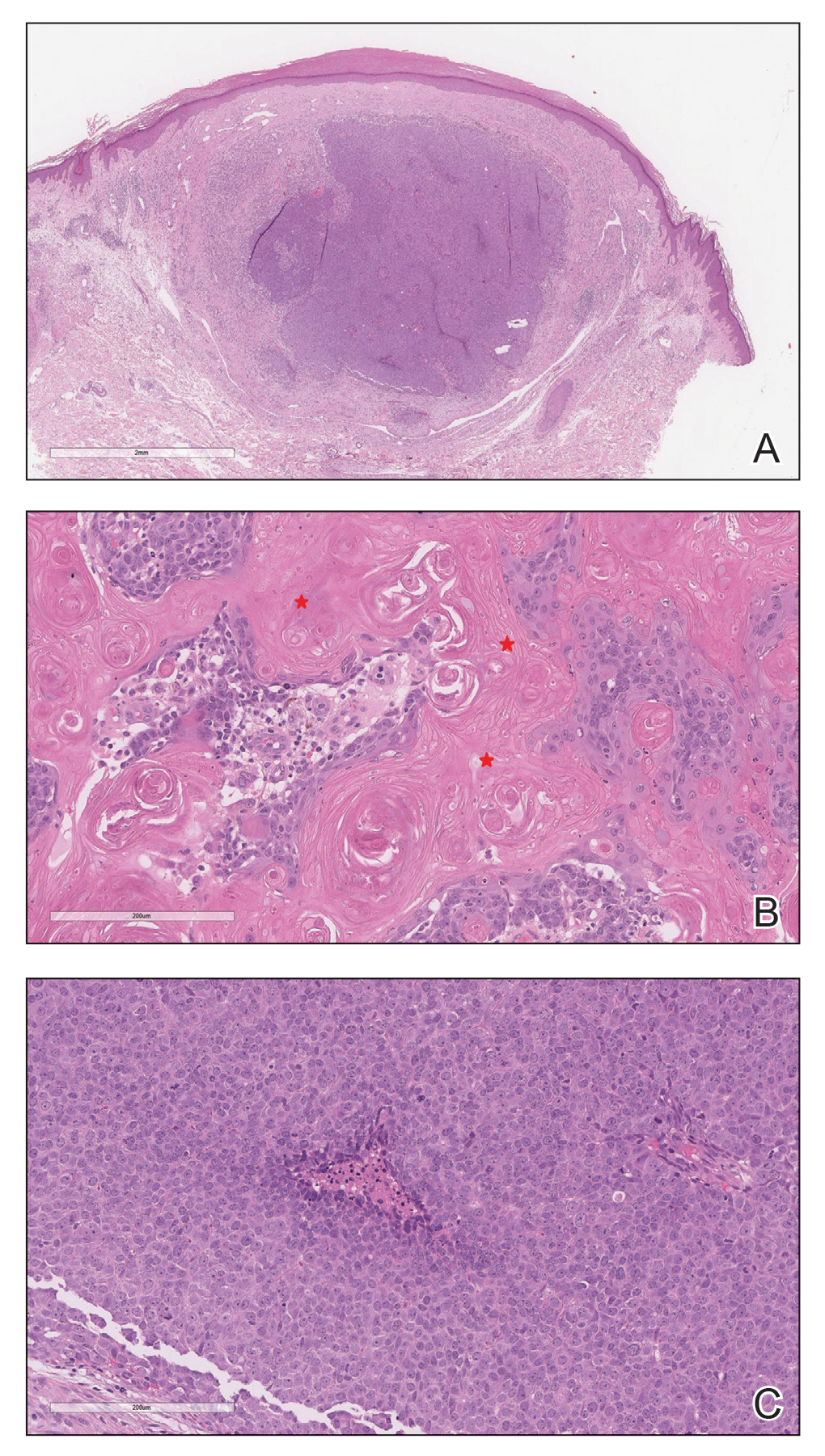

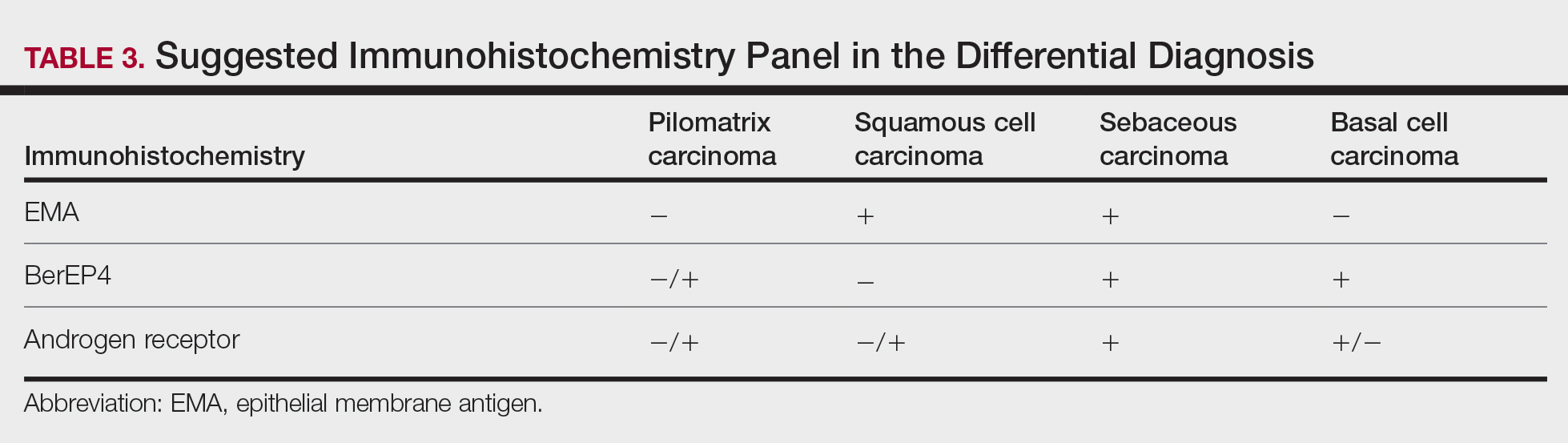

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

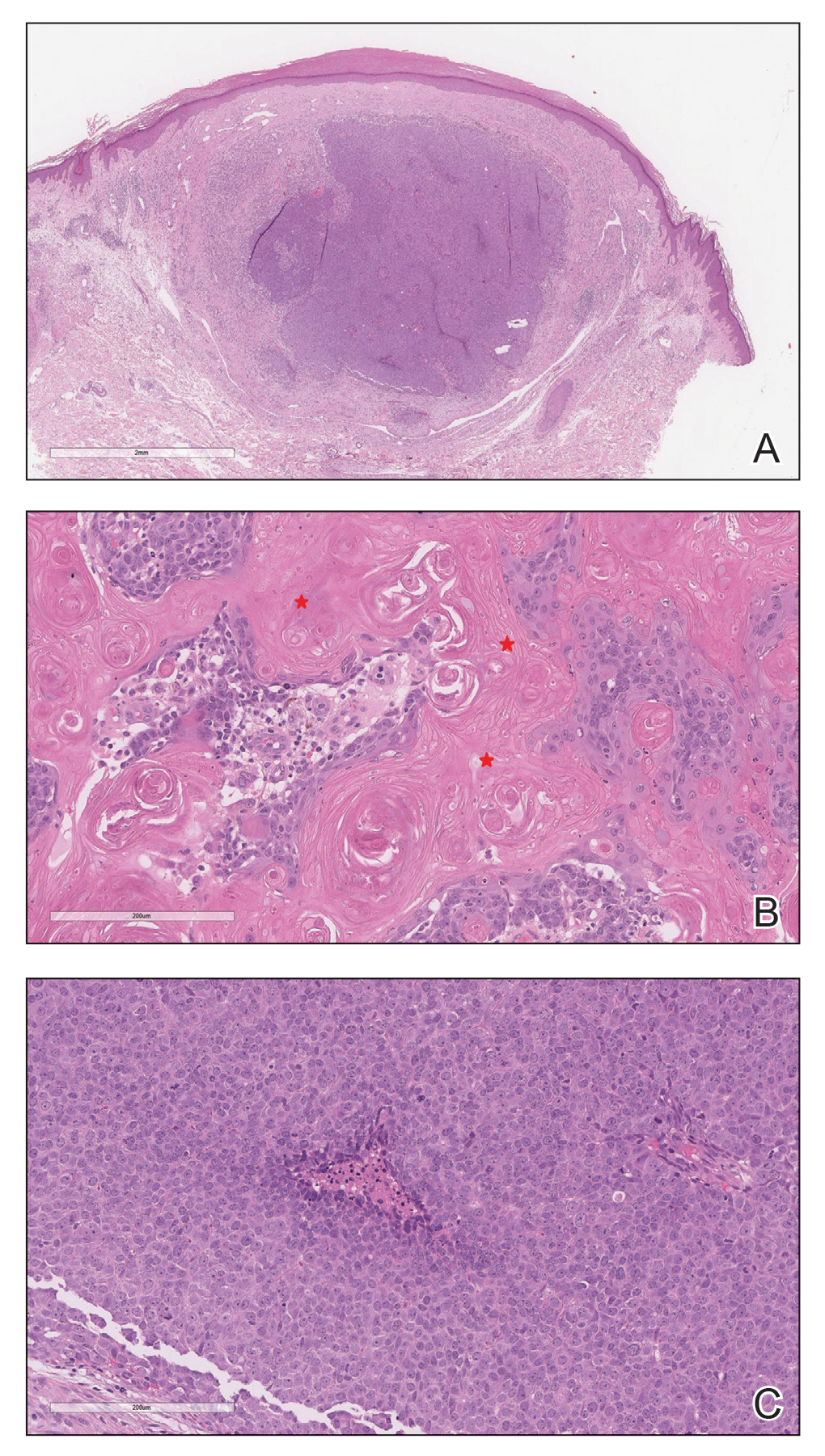

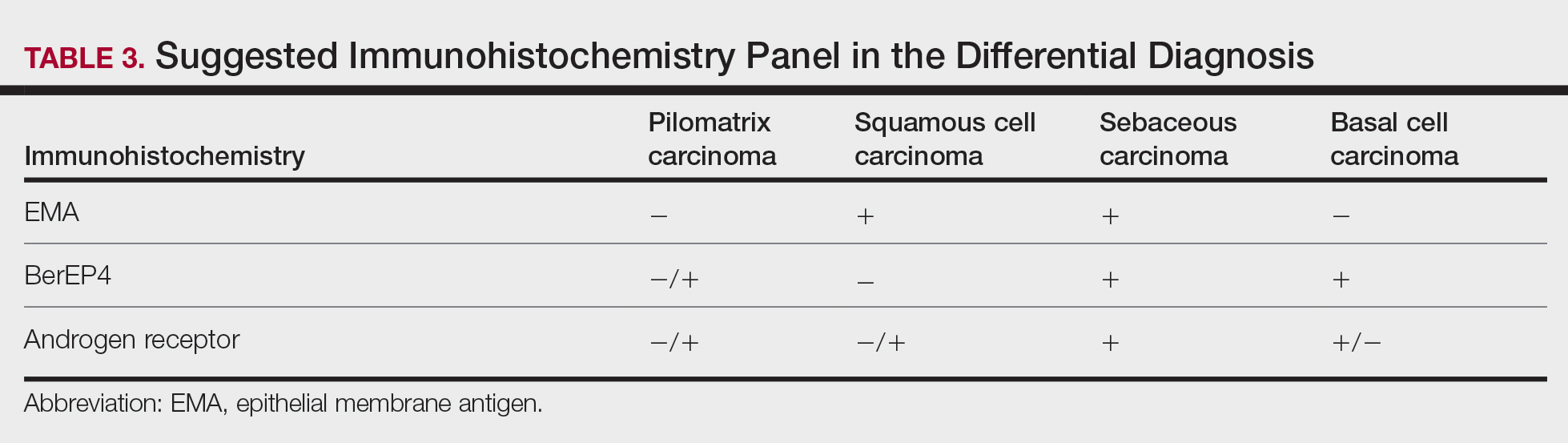

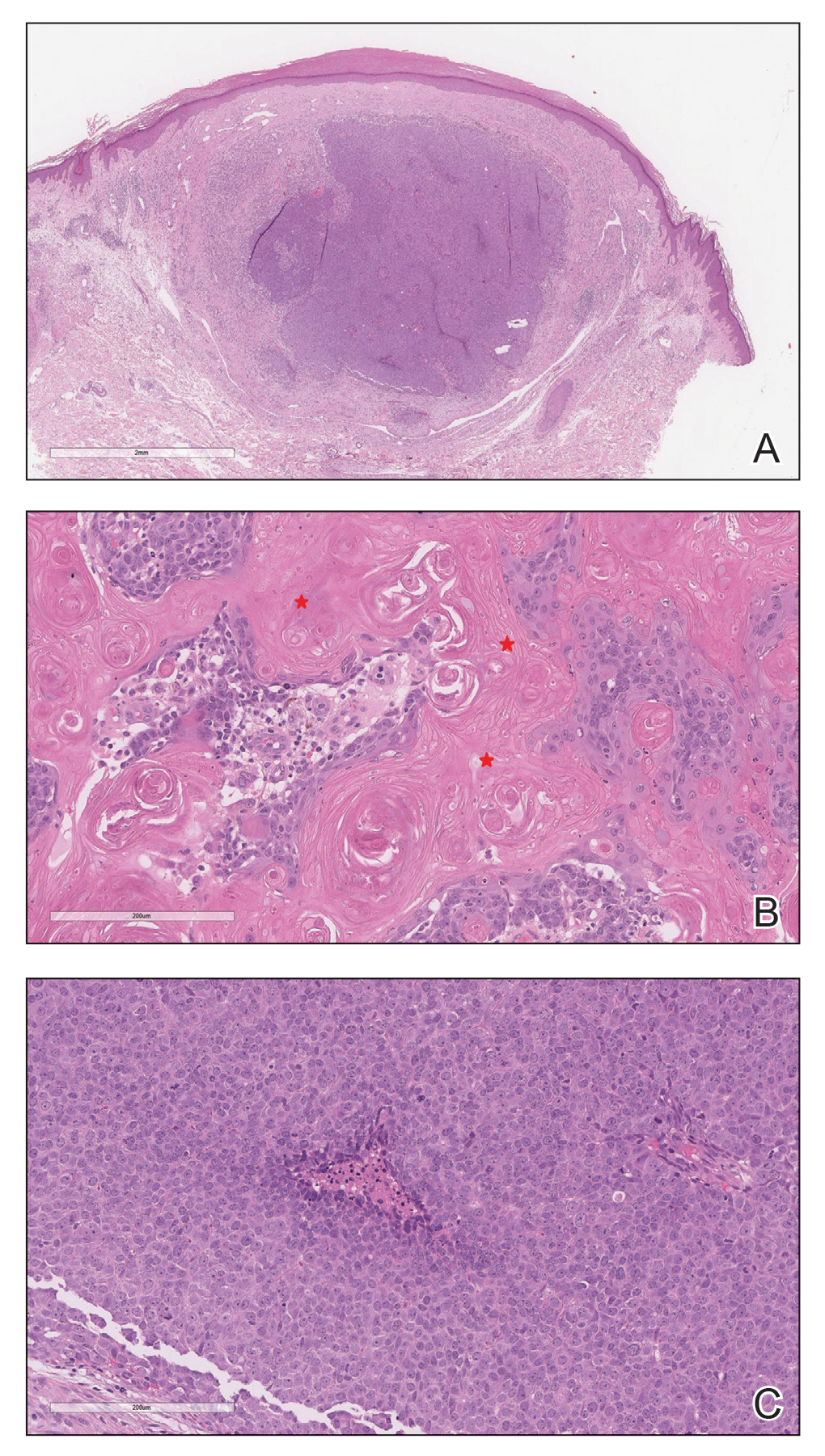

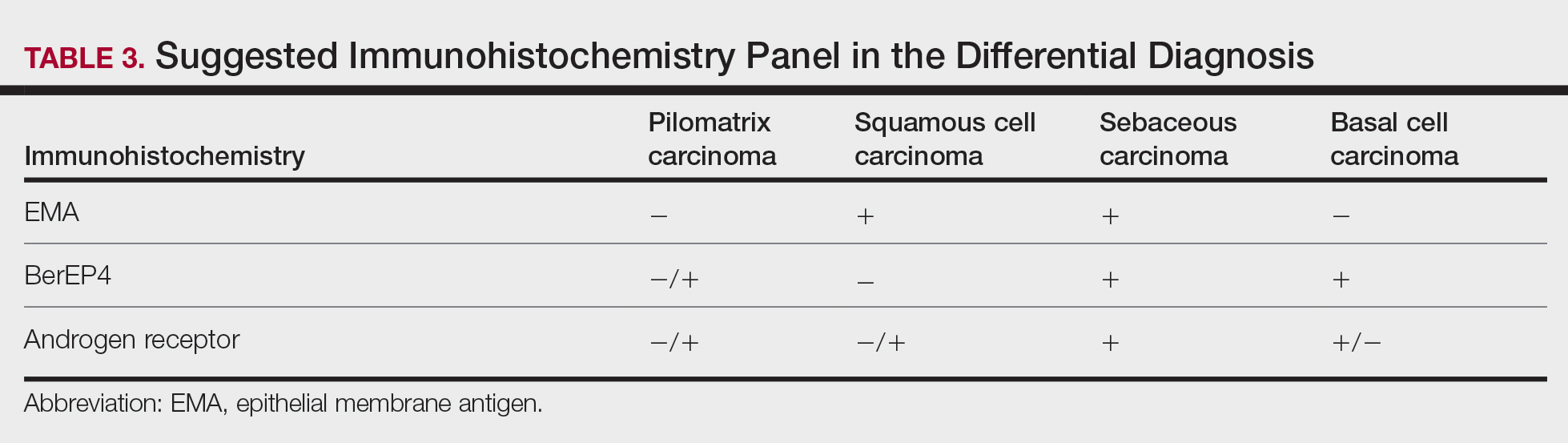

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

The Diagnosis: Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS), also known as Gorlin syndrome, is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that increases the risk for developing various carcinomas and affects multiple organ systems. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is estimated at 1 per 40,000 to 60,000 individuals with no sexual predilection.1,2 Pathogenesis of NBCCS occurs through molecular alterations in the dormant hedgehog signaling pathway, causing constitutive signaling activity and a loss of function in the tumor suppressor patched 1 gene, PTCH1. As a result, the inhibition of smoothened oncogenes is released, Gli proteins are activated, and the hedgehog signaling pathway is no longer quiescent.2 Additional loss of function in the suppressor of fused homolog protein, a negative regulator of the hedgehog pathway, allows for further tumor proliferation. The crucial role these genes play in the hedgehog signaling pathway and their mutation association with NBCCS allows for molecular confirmation in the diagnosis of NBCCS. Allelic losses at the PTCH1 gene site are thought to occur in approximately 70% of NBCCS patients.2

Diagnosis of NBCCS is based on genetic testing to examine pathogenic gene variants, notably in the PTCH1 gene, and identification of characteristic clinical findings.2 Diagnosis of NBCCS requires either 2 minor suggestive criteria and 1 major suggestive criterion, 2 major suggestive criteria and 1 minor suggestive criterion, or 1 major suggestive criterion with molecular confirmation. The presence of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) before 20 years of age or an excessive numbers of BCCs, keratocystic odontogenic tumors (KOTs), palmar or plantar pitting, and first-degree relatives with NBCCS are classified as major suggestive criteria.2 Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients typically have BCCs that crust, ulcerate, or bleed. Minor suggestive criteria for NBCCS are rib abnormalities, skeletal malformations, macrocephaly, cleft lip or palate, and desmoplastic medulloblastoma.2-4 Suppressor of fused homolog protein mutations may increase the risk for desmoplastic medulloblastoma in NBCCS patients. Our patient had 4 of the major suggestive criteria, including a history of KOTs, multiple BCCs, first-degree relatives with NBCCS, and palmar or plantar pitting (bottom quiz image), while having 1 minor suggestive criterion of frontal bossing.

Patients with NBCCS have high phenotypic variability, as their skin carcinomas do not have the classic features of pearly surfaces or corkscrew telangiectasia that typically are associated with BCCs.1 Basal cell carcinomas in NBCCS-affected individuals usually are indistinguishable from sporadic lesions that arise in sun-exposed areas, making NBCCS difficult to diagnose. These sporadic lesions often are misdiagnosed as psoriatic or eczematous lesions, and additional subsequent examination is required. The findings of multiple papules and plaques spanning the body as well as lesions with rolled borders and ulcerated bases, indicative of BCCs, aid dermatologists in distinguishing benign lesions from those of NBCCS.1

Additional differential diagnoses are required to distinguish NBCCS from other similar inherited skin disorders that are characterized by BCCs. The presence of multiple incidental BCCs early in life remains a histopathologic clue for NBCCS diagnosis, as opposed to Rombo syndrome, in which BCCs often develop in adulthood.2,4 In addition, although both Bazex syndrome and Muir-Torre syndrome are characterized by the early onset of BCCs, the lack of skeletal abnormalities and palmar and plantar pitting distinguish these entities from NBCCS.2,4 Furthermore, though psoriasis also can present on the scalp, clinical presentation often includes well-demarcated and symmetric plaques that are erythematous and silvery, all of which were not present in our patient and typically are not seen in NBCCS.5

The recommended treatment of NBCCS is vismodegib, a specific oncogene inhibitor. This medication suppresses the hedgehog signaling pathway by inhibiting smoothened oncogenes and downstream target molecules, thereby decreasing tumor proliferation.6 In doing so, vismodegib inhibits the development of new BCCs while reducing the burden of present ones. Additionally, vismodegib appears to effectively treat KOTs. If successful, this medication may be able to suppress KOTs in patients with NBCCS and thus facilitate surgery.6 Additional hedgehog inhibitors include patidegib, sonidegib, and itraconazole. Patidegib gel 2% currently is in phase 3 clinical trials for evaluation of efficacy and safety in treatment of NBCCS. Sonidegib is approved for the treatment of locally advanced BCCs in the United States and the European Union and for both locally advanced BCCs and metastatic BCCs in Switzerland and Australia.7 Further research is needed before recommending antifungal itraconazole for NBCCS clinical use.8 Other medications for localized areas include topical application of 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod.2

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

- Sangehra R, Grewal P. Gorlin syndrome presentation and the importance of differential diagnosis of skin cancer: a case report. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2018;21:222-224.

- Bresler S, Padwa B, Granter S. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome). Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:119-124.

- Fujii K, Miyashita T. Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome): update and literature review. Pediatr Int. 2014;56:667-674.

- Evans G, Farndon P. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington; 1993-2020.

- Kim WB, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278-285.

- Booms P, Harth M, Sader R, et al. Vismodegib hedgehog-signaling inhibition and treatment of basal cell carcinomas as well as keratocystic odontogenic tumors in Gorlin syndrome. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5:14-19.

- Gutzmer R, Soloon J. Hedgehog pathway inhibition for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Target Oncol. 2019;14:253-267.

- Leavitt E, Lask G, Martin S. Sonic hedgehog pathway inhibition in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:84.

A 63-year-old man with frontal bossing and a history of jaw cysts presented with numerous lesions on the scalp, trunk, and legs with recurrent bleeding. Both of his siblings had similar findings. Many lesions had been present for at least 40 years. Physical examination revealed a large, irregular, atrophic, hyperpigmented plaque on the central scalp with multiple translucent hyperpigmented papules at the periphery (top). Similar papules and plaques were present at the temples, around the waist, and on the distal lower extremities, leading to surgical excision of the largest leg lesions. In addition, there were many pinpoint pits on both palms (bottom). A biopsy was submitted for review, which confirmed basal cell carcinomas on the scalp.

AI: Skin of color underrepresented in datasets used to identify skin cancer

An in the databases, researchers in the United Kingdom report.

Out of 106,950 skin lesions documented in 21 open-access databases and 17 open-access atlases identified by David Wen, BMBCh, from the University of Oxford (England), and colleagues, 2,436 images contained information on Fitzpatrick skin type. Of these, “only 10 images were from individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type V, and only a single image was from an individual with Fitzpatrick skin type VI,” the researchers said. “The ethnicity of these individuals was either Brazilian or unknown.”

In two datasets containing 1,585 images with ethnicity data, “no images were from individuals with an African, Afro-Caribbean, or South Asian background,” Dr. Wen and colleagues noted. “Coupled with the geographical origins of datasets, there was massive under-representation of skin lesion images from darker-skinned populations.”

The results of their systematic review were presented at the National Cancer Research Institute Festival and published on Nov. 9, 2021, in The Lancet Digital Health. To the best of their knowledge, they wrote, this is “the first systematic review of publicly available skin lesion images comprising predominantly dermoscopic and macroscopic images available through open access datasets and atlases.”

Overall, 11 of 14 datasets (79%) were from North America, Europe, or Oceania among datasets with information on country of origin, the researchers said. Either dermoscopic images or macroscopic photographs were the only types of images available in 19 of 21 (91%) datasets. There was some variation in the clinical information available, with 81,662 images (76.4%) containing information on age, 82,848 images (77.5%) having information on gender, and 79,561 images having information about body site (74.4%).

The researchers explained that these datasets might be of limited use in a real-world setting where the images aren’t representative of the population. Artificial intelligence (AI) programs that train using images of patients with one skin type, for example, can potentially misdiagnose patients of another skin type, they said.

“AI programs hold a lot of potential for diagnosing skin cancer because it can look at pictures and quickly and cost-effectively evaluate any worrying spots on the skin,” Dr. Wen said in a press release from the NCRI Festival. “However, it’s important to know about the images and patients used to develop programs, as these influence which groups of people the programs will be most effective for in real-life settings. Research has shown that programs trained on images taken from people with lighter skin types only might not be as accurate for people with darker skin, and vice versa.”

There was also “limited information on who, how and why the images were taken,” Dr. Wen said in the release. “This has implications for the programs developed from these images, due to uncertainty around how they may perform in different groups of people, especially in those who aren’t well represented in datasets, such as those with darker skin. This can potentially lead to the exclusion or even harm of these groups from AI technologies.”

While there are no current guidelines for developing skin image datasets, quality standards are needed, according to the researchers.

“Ensuring equitable digital health includes building unbiased, representative datasets to ensure that the algorithms that are created benefit people of all backgrounds and skin types,” they concluded in the study.

Neil Steven, MBBS, MA, PhD, FRCP, an NCRI Skin Group member who was not involved with the research, stated in the press release that the results from the study by Dr. Wen and colleagues “raise concerns about the ability of AI to assist in skin cancer diagnosis, especially in a global context.”

“I hope this work will continue and help ensure that the progress we make in using AI in medicine will benefit all patients, recognizing that human skin color is highly diverse,” said Dr. Steven, honorary consultant in medical oncology at University Hospitals Birmingham (England) NHS Foundation Trust.

‘We need more images of everybody’

Dermatologist Adewole Adamson, MD, MPP, assistant professor in the department of internal medicine (division of dermatology) at the University of Texas at Austin, said in an interview that a “major potential downside” of algorithms not trained on diverse datasets is the potential for incorrect diagnoses.

“The harms of algorithms used for diagnostic purposes in the skin can be particularly significant because of the scalability of this technology. A lot of thought needs to be put into how these algorithms are developed and tested,” said Dr. Adamson, who reviewed the manuscript of The Lancet Digital Health study but was not involved with the research.

He referred to the results of a recently published study in JAMA Dermatology, which found that only 10% of studies used to develop or test deep-learning algorithms contained metadata on skin tone. “Furthermore, most datasets are from countries where darker skin types are not represented. [These] algorithms therefore likely underperform on people of darker skin types and thus, users should be wary,” Dr. Adamson said.

A consensus guideline should be developed for public AI algorithms, he said, which should have metadata containing information on sex, race/ethnicity, geographic location, skin type, and part of the body. “This distribution should also be reported in any publication of an algorithm so that users can see if the distribution of the population in the training data mirrors that of the population in which it is intended to be used,” he added.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was not involved with the research, said that, while this issue of underrepresentation has been known in dermatology for some time, the strength of the Lancet study is that it is a large study, with a message of “we need more images of everybody.”

“This is probably the broadest study looking at every possible accessible resource and taking an organized approach,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “But I think it also raises some important points about how we think about skin tones and how we refer to them as well with respect to misusing classification schemes that we currently have.”

While using ethnicity data and certain Fitzpatrick skin types as a proxy for darker skin is a limitation of the metadata the study authors had available, it also highlights “a broader problem with respect to lexicon regarding skin tone,” he explained.

“Skin does not have a race, it doesn’t have an ethnicity,” Dr. Friedman said.

A dataset that contains not only different skin tones but how different dermatologic conditions look across skin tones is important. “If you just look at one photo of one skin tone, you missed the fact that clinical presentations can be so polymorphic, especially because of different skin tones,” Dr. Friedman said.

“We need to keep pushing this message to ensure that images keep getting collected. We [need to] ensure that there’s quality control with these images and that we’re disseminating them in a way that everyone has access, both from self-learning, but also to teach others,” said Dr. Friedman, coeditor of a recently introduced dermatology atlas showing skin conditions in different skin tones.

Adamson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Friedman is a coeditor of a dermatology atlas supported by Allergan Aesthetics and SkinBetter Science. This study was funded by NHSX and the Health Foundation. Three authors reported being paid employees of Databiology at the time of the study. The other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An in the databases, researchers in the United Kingdom report.

Out of 106,950 skin lesions documented in 21 open-access databases and 17 open-access atlases identified by David Wen, BMBCh, from the University of Oxford (England), and colleagues, 2,436 images contained information on Fitzpatrick skin type. Of these, “only 10 images were from individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type V, and only a single image was from an individual with Fitzpatrick skin type VI,” the researchers said. “The ethnicity of these individuals was either Brazilian or unknown.”

In two datasets containing 1,585 images with ethnicity data, “no images were from individuals with an African, Afro-Caribbean, or South Asian background,” Dr. Wen and colleagues noted. “Coupled with the geographical origins of datasets, there was massive under-representation of skin lesion images from darker-skinned populations.”

The results of their systematic review were presented at the National Cancer Research Institute Festival and published on Nov. 9, 2021, in The Lancet Digital Health. To the best of their knowledge, they wrote, this is “the first systematic review of publicly available skin lesion images comprising predominantly dermoscopic and macroscopic images available through open access datasets and atlases.”

Overall, 11 of 14 datasets (79%) were from North America, Europe, or Oceania among datasets with information on country of origin, the researchers said. Either dermoscopic images or macroscopic photographs were the only types of images available in 19 of 21 (91%) datasets. There was some variation in the clinical information available, with 81,662 images (76.4%) containing information on age, 82,848 images (77.5%) having information on gender, and 79,561 images having information about body site (74.4%).

The researchers explained that these datasets might be of limited use in a real-world setting where the images aren’t representative of the population. Artificial intelligence (AI) programs that train using images of patients with one skin type, for example, can potentially misdiagnose patients of another skin type, they said.

“AI programs hold a lot of potential for diagnosing skin cancer because it can look at pictures and quickly and cost-effectively evaluate any worrying spots on the skin,” Dr. Wen said in a press release from the NCRI Festival. “However, it’s important to know about the images and patients used to develop programs, as these influence which groups of people the programs will be most effective for in real-life settings. Research has shown that programs trained on images taken from people with lighter skin types only might not be as accurate for people with darker skin, and vice versa.”

There was also “limited information on who, how and why the images were taken,” Dr. Wen said in the release. “This has implications for the programs developed from these images, due to uncertainty around how they may perform in different groups of people, especially in those who aren’t well represented in datasets, such as those with darker skin. This can potentially lead to the exclusion or even harm of these groups from AI technologies.”

While there are no current guidelines for developing skin image datasets, quality standards are needed, according to the researchers.

“Ensuring equitable digital health includes building unbiased, representative datasets to ensure that the algorithms that are created benefit people of all backgrounds and skin types,” they concluded in the study.

Neil Steven, MBBS, MA, PhD, FRCP, an NCRI Skin Group member who was not involved with the research, stated in the press release that the results from the study by Dr. Wen and colleagues “raise concerns about the ability of AI to assist in skin cancer diagnosis, especially in a global context.”

“I hope this work will continue and help ensure that the progress we make in using AI in medicine will benefit all patients, recognizing that human skin color is highly diverse,” said Dr. Steven, honorary consultant in medical oncology at University Hospitals Birmingham (England) NHS Foundation Trust.

‘We need more images of everybody’

Dermatologist Adewole Adamson, MD, MPP, assistant professor in the department of internal medicine (division of dermatology) at the University of Texas at Austin, said in an interview that a “major potential downside” of algorithms not trained on diverse datasets is the potential for incorrect diagnoses.

“The harms of algorithms used for diagnostic purposes in the skin can be particularly significant because of the scalability of this technology. A lot of thought needs to be put into how these algorithms are developed and tested,” said Dr. Adamson, who reviewed the manuscript of The Lancet Digital Health study but was not involved with the research.

He referred to the results of a recently published study in JAMA Dermatology, which found that only 10% of studies used to develop or test deep-learning algorithms contained metadata on skin tone. “Furthermore, most datasets are from countries where darker skin types are not represented. [These] algorithms therefore likely underperform on people of darker skin types and thus, users should be wary,” Dr. Adamson said.

A consensus guideline should be developed for public AI algorithms, he said, which should have metadata containing information on sex, race/ethnicity, geographic location, skin type, and part of the body. “This distribution should also be reported in any publication of an algorithm so that users can see if the distribution of the population in the training data mirrors that of the population in which it is intended to be used,” he added.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was not involved with the research, said that, while this issue of underrepresentation has been known in dermatology for some time, the strength of the Lancet study is that it is a large study, with a message of “we need more images of everybody.”

“This is probably the broadest study looking at every possible accessible resource and taking an organized approach,” Dr. Friedman said in an interview. “But I think it also raises some important points about how we think about skin tones and how we refer to them as well with respect to misusing classification schemes that we currently have.”

While using ethnicity data and certain Fitzpatrick skin types as a proxy for darker skin is a limitation of the metadata the study authors had available, it also highlights “a broader problem with respect to lexicon regarding skin tone,” he explained.

“Skin does not have a race, it doesn’t have an ethnicity,” Dr. Friedman said.

A dataset that contains not only different skin tones but how different dermatologic conditions look across skin tones is important. “If you just look at one photo of one skin tone, you missed the fact that clinical presentations can be so polymorphic, especially because of different skin tones,” Dr. Friedman said.

“We need to keep pushing this message to ensure that images keep getting collected. We [need to] ensure that there’s quality control with these images and that we’re disseminating them in a way that everyone has access, both from self-learning, but also to teach others,” said Dr. Friedman, coeditor of a recently introduced dermatology atlas showing skin conditions in different skin tones.