User login

ACOG supports delayed umbilical cord clamping for term infants

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that umbilical cord clamping be delayed for at least 30-60 seconds after birth in vigorous preterm and term infants.

Since early studies suggested that up to 90% of the blood transfer from the placenta to the newborn after birth happens with an infant’s first few breaths, it has become common practice to clamp the cord within 15-20 seconds after birth.

In 2012, the ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice recommended use of delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants, but found a lack of evidence in term infants. “However, more recent randomized controlled trials of term and preterm infants as well as physiologic studies of blood volume, oxygenation, and arterial pressure have evaluated the effects of immediate versus delayed umbilical cord clamping (usually defined as cord clamping at least 30-60 seconds after birth),” wrote the members of the College’s Committee on Obstetric Practice in an updated opinion released on Dec. 21.

These studies showed that around 80 mL of blood is transferred from the placenta within 1 minute of birth, which appears to be facilitated by the newborn’s initial breaths. This initial transfer of blood supplies significant quantities of iron – 40-50 mg/kg of body weight - and is associated with a lower risk of iron deficiency during the first year of life (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e5-10).

The committee cited a 2012 systematic review of the data on preterm infants that found a 39% reduction in the number of infants requiring transfusion for anemia when delayed umbilical cord clamping – defined as a delay of 30-180 seconds – was used, compared with immediate clamping. The review also noted a 41% reduction in the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage and 38% reduction in necrotizing enterocolitis, compared with immediate umbilical cord clamping.

Similarly in term infants, those who had their umbilical cord clamped early showed significantly lower hemoglobin concentrations at birth and were more likely to have iron deficiency at 3-6 months of age, compared with term infants who had delayed clamping.

The committee did note that preterm infants who experienced delayed cord clamping showed higher peak bilirubin levels, compared with early clamping. In term infants, delayed cord clamping was associated with a small increase in the incidence of jaundice requiring phototherapy, although there were no significant differences in the rates of polycythemia or jaundice overall.

“Consequently, obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers adopting delayed cord clamping in term infants should ensure that mechanisms are in place to monitor for and treat neonatal jaundice,” the committee members wrote.

With regards to maternal outcomes, there had been concerns that delayed umbilical cord clamping could increase the risk of maternal hemorrhage. But a review of five trials including more than 2,200 women found no sign of an increase in adverse events such as postpartum hemorrhage, increased blood loss at delivery, blood transfusions, or reduced postpartum hemoglobin levels.

“However, when there is increased risk of hemorrhage (e.g., placenta previa or placental abruption), the benefits of delayed umbilical cord clamping need to be balanced with the need for timely hemodynamic stabilization of the woman,” the authors wrote.

The committee found that skin-to-skin care could still take place with delayed umbilical cord clamping, as gravity was not necessary to facilitate the flow of blood from the placenta to the newborn. They also advised that early care of the newborn could still be carried out, including drying and stimulating for the first breath.

Delayed umbilical cord clamping should also not interfere with active management of the third stage of labor, including the use of uterotonic agents after delivery.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that umbilical cord clamping be delayed for at least 30-60 seconds after birth in vigorous preterm and term infants.

Since early studies suggested that up to 90% of the blood transfer from the placenta to the newborn after birth happens with an infant’s first few breaths, it has become common practice to clamp the cord within 15-20 seconds after birth.

In 2012, the ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice recommended use of delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants, but found a lack of evidence in term infants. “However, more recent randomized controlled trials of term and preterm infants as well as physiologic studies of blood volume, oxygenation, and arterial pressure have evaluated the effects of immediate versus delayed umbilical cord clamping (usually defined as cord clamping at least 30-60 seconds after birth),” wrote the members of the College’s Committee on Obstetric Practice in an updated opinion released on Dec. 21.

These studies showed that around 80 mL of blood is transferred from the placenta within 1 minute of birth, which appears to be facilitated by the newborn’s initial breaths. This initial transfer of blood supplies significant quantities of iron – 40-50 mg/kg of body weight - and is associated with a lower risk of iron deficiency during the first year of life (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e5-10).

The committee cited a 2012 systematic review of the data on preterm infants that found a 39% reduction in the number of infants requiring transfusion for anemia when delayed umbilical cord clamping – defined as a delay of 30-180 seconds – was used, compared with immediate clamping. The review also noted a 41% reduction in the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage and 38% reduction in necrotizing enterocolitis, compared with immediate umbilical cord clamping.

Similarly in term infants, those who had their umbilical cord clamped early showed significantly lower hemoglobin concentrations at birth and were more likely to have iron deficiency at 3-6 months of age, compared with term infants who had delayed clamping.

The committee did note that preterm infants who experienced delayed cord clamping showed higher peak bilirubin levels, compared with early clamping. In term infants, delayed cord clamping was associated with a small increase in the incidence of jaundice requiring phototherapy, although there were no significant differences in the rates of polycythemia or jaundice overall.

“Consequently, obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers adopting delayed cord clamping in term infants should ensure that mechanisms are in place to monitor for and treat neonatal jaundice,” the committee members wrote.

With regards to maternal outcomes, there had been concerns that delayed umbilical cord clamping could increase the risk of maternal hemorrhage. But a review of five trials including more than 2,200 women found no sign of an increase in adverse events such as postpartum hemorrhage, increased blood loss at delivery, blood transfusions, or reduced postpartum hemoglobin levels.

“However, when there is increased risk of hemorrhage (e.g., placenta previa or placental abruption), the benefits of delayed umbilical cord clamping need to be balanced with the need for timely hemodynamic stabilization of the woman,” the authors wrote.

The committee found that skin-to-skin care could still take place with delayed umbilical cord clamping, as gravity was not necessary to facilitate the flow of blood from the placenta to the newborn. They also advised that early care of the newborn could still be carried out, including drying and stimulating for the first breath.

Delayed umbilical cord clamping should also not interfere with active management of the third stage of labor, including the use of uterotonic agents after delivery.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that umbilical cord clamping be delayed for at least 30-60 seconds after birth in vigorous preterm and term infants.

Since early studies suggested that up to 90% of the blood transfer from the placenta to the newborn after birth happens with an infant’s first few breaths, it has become common practice to clamp the cord within 15-20 seconds after birth.

In 2012, the ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice recommended use of delayed umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants, but found a lack of evidence in term infants. “However, more recent randomized controlled trials of term and preterm infants as well as physiologic studies of blood volume, oxygenation, and arterial pressure have evaluated the effects of immediate versus delayed umbilical cord clamping (usually defined as cord clamping at least 30-60 seconds after birth),” wrote the members of the College’s Committee on Obstetric Practice in an updated opinion released on Dec. 21.

These studies showed that around 80 mL of blood is transferred from the placenta within 1 minute of birth, which appears to be facilitated by the newborn’s initial breaths. This initial transfer of blood supplies significant quantities of iron – 40-50 mg/kg of body weight - and is associated with a lower risk of iron deficiency during the first year of life (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:e5-10).

The committee cited a 2012 systematic review of the data on preterm infants that found a 39% reduction in the number of infants requiring transfusion for anemia when delayed umbilical cord clamping – defined as a delay of 30-180 seconds – was used, compared with immediate clamping. The review also noted a 41% reduction in the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage and 38% reduction in necrotizing enterocolitis, compared with immediate umbilical cord clamping.

Similarly in term infants, those who had their umbilical cord clamped early showed significantly lower hemoglobin concentrations at birth and were more likely to have iron deficiency at 3-6 months of age, compared with term infants who had delayed clamping.

The committee did note that preterm infants who experienced delayed cord clamping showed higher peak bilirubin levels, compared with early clamping. In term infants, delayed cord clamping was associated with a small increase in the incidence of jaundice requiring phototherapy, although there were no significant differences in the rates of polycythemia or jaundice overall.

“Consequently, obstetrician-gynecologists and other obstetric care providers adopting delayed cord clamping in term infants should ensure that mechanisms are in place to monitor for and treat neonatal jaundice,” the committee members wrote.

With regards to maternal outcomes, there had been concerns that delayed umbilical cord clamping could increase the risk of maternal hemorrhage. But a review of five trials including more than 2,200 women found no sign of an increase in adverse events such as postpartum hemorrhage, increased blood loss at delivery, blood transfusions, or reduced postpartum hemoglobin levels.

“However, when there is increased risk of hemorrhage (e.g., placenta previa or placental abruption), the benefits of delayed umbilical cord clamping need to be balanced with the need for timely hemodynamic stabilization of the woman,” the authors wrote.

The committee found that skin-to-skin care could still take place with delayed umbilical cord clamping, as gravity was not necessary to facilitate the flow of blood from the placenta to the newborn. They also advised that early care of the newborn could still be carried out, including drying and stimulating for the first breath.

Delayed umbilical cord clamping should also not interfere with active management of the third stage of labor, including the use of uterotonic agents after delivery.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

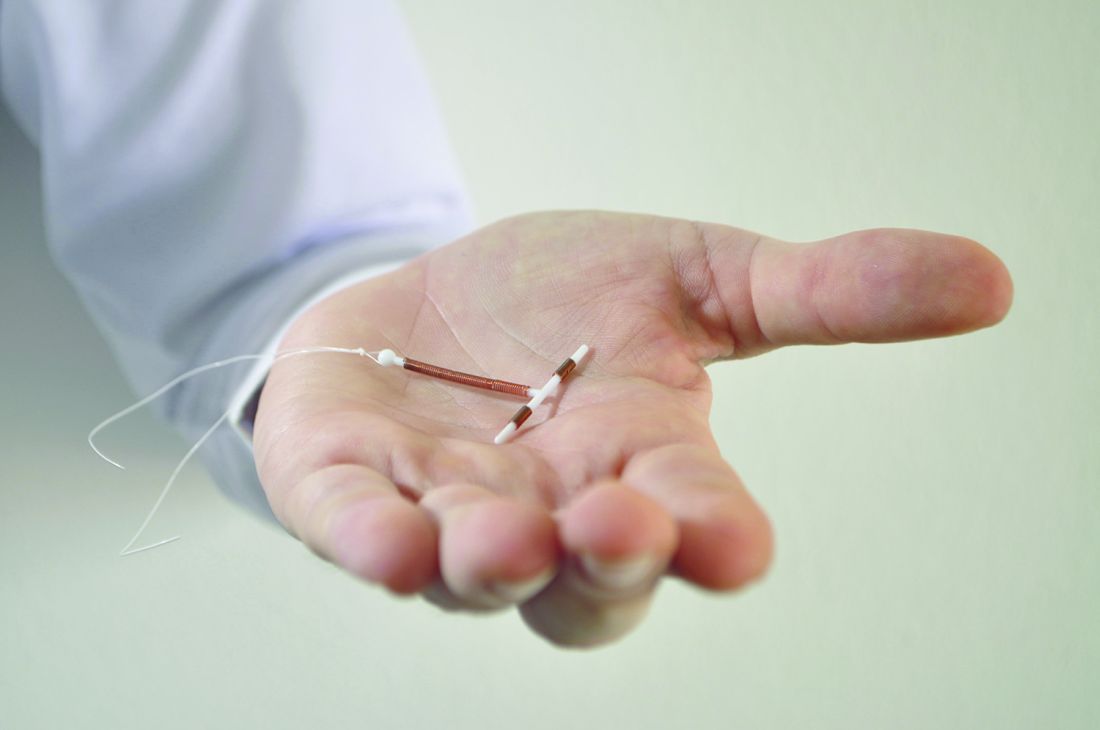

Immediate postpartum LARC requires cross-disciplinary cooperation in the hospital

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Success in establishing an immediate postpartum LARC program involves team-building across hospital disciplines.

Major finding: Factors associated with success included early coordination among financial, administrative, pharmacy, and clinical personnel.

Data source: A qualitative analysis of interviews with 32 employees (clinical and nonclinical) from 10 hospitals in Georgia.

Disclosures: Two authors disclosed relationships with LARC manufacturers.

USPSTF nixes routine genital herpes screening

Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms of this approach outweigh the benefits, according to an updated US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement published online in JAMA.

The USPSTF last addressed screening for herpes simplex virus (HSV) in a 2005 Recommendation Statement, which advised against routine screening of asymptomatic patients at that time. “A small number” of clinical trials examined the issue since then, so the group commissioned a review of the literature through October 2016 to incorporate any new findings into the update, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, chair of the USPSTF and lead author of the update, and her associates.

Dr. Feltner and her colleagues concluded that current serologic screening tests produce a high rate of false-positive results – as much as 50% – and that those in turn lead to psychosocial harms such as distress and disruption of personal relationships, as well as increased costs and potential medical harm associated with confirmatory testing and unnecessary treatment.

Given the false-positive rates of the most widely used screening tests and the 15% prevalence of genital herpes in the general population, “screening 10,000 persons would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.” Moreover, confirmatory testing is offered only at a single research laboratory, said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates on the Task Force.

Based on these findings and given the natural history and epidemiology of genital herpes, they characterized the potential benefits of routine screening as “no greater than small,” and the harms as “at least moderate” (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2525-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776).

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommend against routine HSV screening of adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, the investigators noted.

The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

It’s disappointing that the performance of screening tests hasn’t improved during the 10 years since the last USPSTF Recommendation Statement.

These findings should serve as a call to action for federal health agencies and their partners in industry to prioritize the development of better tests and stem the continuing epidemic of genital herpes.

Another important step would be to work vigorously to reduce the pervasive stigma of this disease, which also hinders management and control efforts. The public continues to harbor misperceptions about the severity of genital herpes and the availability of effective treatment, which adds to disproportionate stigmatization of those infected.

Edward W. Hook III, MD, is in the department of microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He reported ties to Hologic, Roche Molecular, Becton Dickinson, and Cepheid. Dr. Hook made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the USPSTF Recommendation Statement (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2493-4).

It’s disappointing that the performance of screening tests hasn’t improved during the 10 years since the last USPSTF Recommendation Statement.

These findings should serve as a call to action for federal health agencies and their partners in industry to prioritize the development of better tests and stem the continuing epidemic of genital herpes.

Another important step would be to work vigorously to reduce the pervasive stigma of this disease, which also hinders management and control efforts. The public continues to harbor misperceptions about the severity of genital herpes and the availability of effective treatment, which adds to disproportionate stigmatization of those infected.

Edward W. Hook III, MD, is in the department of microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He reported ties to Hologic, Roche Molecular, Becton Dickinson, and Cepheid. Dr. Hook made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the USPSTF Recommendation Statement (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2493-4).

It’s disappointing that the performance of screening tests hasn’t improved during the 10 years since the last USPSTF Recommendation Statement.

These findings should serve as a call to action for federal health agencies and their partners in industry to prioritize the development of better tests and stem the continuing epidemic of genital herpes.

Another important step would be to work vigorously to reduce the pervasive stigma of this disease, which also hinders management and control efforts. The public continues to harbor misperceptions about the severity of genital herpes and the availability of effective treatment, which adds to disproportionate stigmatization of those infected.

Edward W. Hook III, MD, is in the department of microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He reported ties to Hologic, Roche Molecular, Becton Dickinson, and Cepheid. Dr. Hook made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the USPSTF Recommendation Statement (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2493-4).

Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms of this approach outweigh the benefits, according to an updated US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement published online in JAMA.

The USPSTF last addressed screening for herpes simplex virus (HSV) in a 2005 Recommendation Statement, which advised against routine screening of asymptomatic patients at that time. “A small number” of clinical trials examined the issue since then, so the group commissioned a review of the literature through October 2016 to incorporate any new findings into the update, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, chair of the USPSTF and lead author of the update, and her associates.

Dr. Feltner and her colleagues concluded that current serologic screening tests produce a high rate of false-positive results – as much as 50% – and that those in turn lead to psychosocial harms such as distress and disruption of personal relationships, as well as increased costs and potential medical harm associated with confirmatory testing and unnecessary treatment.

Given the false-positive rates of the most widely used screening tests and the 15% prevalence of genital herpes in the general population, “screening 10,000 persons would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.” Moreover, confirmatory testing is offered only at a single research laboratory, said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates on the Task Force.

Based on these findings and given the natural history and epidemiology of genital herpes, they characterized the potential benefits of routine screening as “no greater than small,” and the harms as “at least moderate” (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2525-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776).

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommend against routine HSV screening of adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, the investigators noted.

The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms of this approach outweigh the benefits, according to an updated US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement published online in JAMA.

The USPSTF last addressed screening for herpes simplex virus (HSV) in a 2005 Recommendation Statement, which advised against routine screening of asymptomatic patients at that time. “A small number” of clinical trials examined the issue since then, so the group commissioned a review of the literature through October 2016 to incorporate any new findings into the update, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, chair of the USPSTF and lead author of the update, and her associates.

Dr. Feltner and her colleagues concluded that current serologic screening tests produce a high rate of false-positive results – as much as 50% – and that those in turn lead to psychosocial harms such as distress and disruption of personal relationships, as well as increased costs and potential medical harm associated with confirmatory testing and unnecessary treatment.

Given the false-positive rates of the most widely used screening tests and the 15% prevalence of genital herpes in the general population, “screening 10,000 persons would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.” Moreover, confirmatory testing is offered only at a single research laboratory, said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates on the Task Force.

Based on these findings and given the natural history and epidemiology of genital herpes, they characterized the potential benefits of routine screening as “no greater than small,” and the harms as “at least moderate” (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2525-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776).

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommend against routine HSV screening of adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, the investigators noted.

The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Asymptomatic adults and adolescents should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms outweigh the benefits, according to an updated USPSTF recommendation statement.

Major finding: Given the nearly 50% false-positive rate of current screening tests, screening 10,000 members of the general population would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.

Data source: A systematic review of 17 studies involving 9,736 participants regarding the accuracy, benefits, and harms of HSV screening.

Disclosures: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

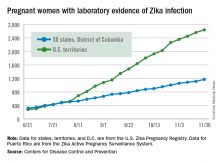

First trimester exposure raises risk of Zika-related birth defects

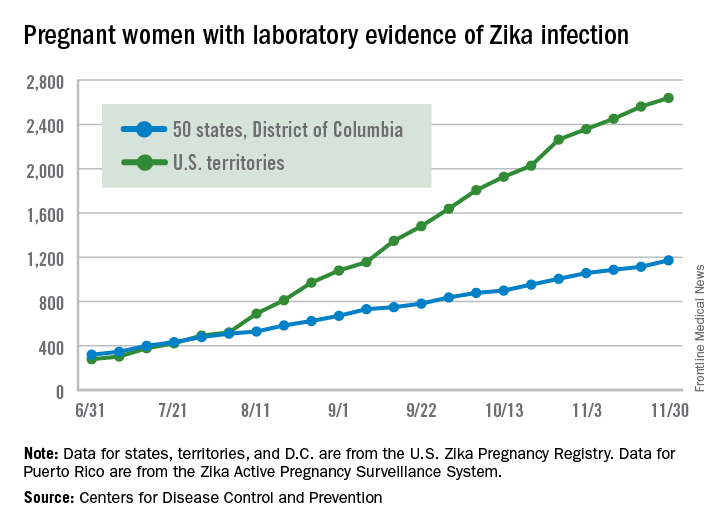

Birth defects associated with the Zika virus occurred in 11% of completed pregnancies of mothers infected with the virus during the first trimester, based on data from the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry. The findings were published online in JAMA.

Based on preliminary findings from 442 completed pregnancies, 6% of fetuses or infants of women with possible Zika infections at any point during pregnancy had evidence of Zika-associated birth defects, as did 11% of infants or fetuses of women with possible Zika infections during the first trimester only, or during the first trimester and periconceptual period (JAMA. 2016 Dec 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19006).

The researchers reviewed data from completed pregnancies in the continental U.S. and Hawaii from Jan. 15, 2016, to Sept. 22, 2016. The data were collected from state and local health departments through the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry.

Birth defects were reported in 26 cases; 16 of 271 asymptomatic women and 10 of 167 symptomatic women (approximately 6% of each group). The most common birth defects potentially associated with Zika were microcephaly and brain abnormalities (14 cases), 4 brain abnormalities without microcephaly, and 4 cases of microcephaly and no reported neuroimaging. Overall, microcephaly was present in 4% of completed pregnancies.

Other potentially Zika-related complications included intracranial calcifications, corpus callosum abnormalities, abnormal cortical formation, cerebral atrophy, ventriculomegaly, hydrocephaly, and cerebellar abnormalities, the researchers wrote.

The women ranged in age from 15 to 50 years, and the population included 395 live births (21 infants with birth defects) and 47 pregnancy losses (5 fetuses with birth defects).

“No birth defects were reported among the pregnancies with maternal symptoms or exposure only in the second trimester or third trimester,” the researchers noted, “but there are insufficient data to adequately estimate the proportion affected during these trimesters,” they wrote.

Long-term monitoring of infants with possible congenital Zika virus is essential, the researchers wrote, as some normocephalic infants develop adverse effects of the virus not present at birth.

“In addition, future observations can elucidate the possible role of Zika virus infection in other outcomes, including spontaneous abortions and stillbirths as well as other structural birth defects that are not currently part of the inclusion criteria for Zika-associated birth defects surveillance,” they noted.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Birth defects associated with the Zika virus occurred in 11% of completed pregnancies of mothers infected with the virus during the first trimester, based on data from the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry. The findings were published online in JAMA.

Based on preliminary findings from 442 completed pregnancies, 6% of fetuses or infants of women with possible Zika infections at any point during pregnancy had evidence of Zika-associated birth defects, as did 11% of infants or fetuses of women with possible Zika infections during the first trimester only, or during the first trimester and periconceptual period (JAMA. 2016 Dec 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19006).

The researchers reviewed data from completed pregnancies in the continental U.S. and Hawaii from Jan. 15, 2016, to Sept. 22, 2016. The data were collected from state and local health departments through the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry.

Birth defects were reported in 26 cases; 16 of 271 asymptomatic women and 10 of 167 symptomatic women (approximately 6% of each group). The most common birth defects potentially associated with Zika were microcephaly and brain abnormalities (14 cases), 4 brain abnormalities without microcephaly, and 4 cases of microcephaly and no reported neuroimaging. Overall, microcephaly was present in 4% of completed pregnancies.

Other potentially Zika-related complications included intracranial calcifications, corpus callosum abnormalities, abnormal cortical formation, cerebral atrophy, ventriculomegaly, hydrocephaly, and cerebellar abnormalities, the researchers wrote.

The women ranged in age from 15 to 50 years, and the population included 395 live births (21 infants with birth defects) and 47 pregnancy losses (5 fetuses with birth defects).

“No birth defects were reported among the pregnancies with maternal symptoms or exposure only in the second trimester or third trimester,” the researchers noted, “but there are insufficient data to adequately estimate the proportion affected during these trimesters,” they wrote.

Long-term monitoring of infants with possible congenital Zika virus is essential, the researchers wrote, as some normocephalic infants develop adverse effects of the virus not present at birth.

“In addition, future observations can elucidate the possible role of Zika virus infection in other outcomes, including spontaneous abortions and stillbirths as well as other structural birth defects that are not currently part of the inclusion criteria for Zika-associated birth defects surveillance,” they noted.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Birth defects associated with the Zika virus occurred in 11% of completed pregnancies of mothers infected with the virus during the first trimester, based on data from the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry. The findings were published online in JAMA.

Based on preliminary findings from 442 completed pregnancies, 6% of fetuses or infants of women with possible Zika infections at any point during pregnancy had evidence of Zika-associated birth defects, as did 11% of infants or fetuses of women with possible Zika infections during the first trimester only, or during the first trimester and periconceptual period (JAMA. 2016 Dec 13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19006).

The researchers reviewed data from completed pregnancies in the continental U.S. and Hawaii from Jan. 15, 2016, to Sept. 22, 2016. The data were collected from state and local health departments through the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry.

Birth defects were reported in 26 cases; 16 of 271 asymptomatic women and 10 of 167 symptomatic women (approximately 6% of each group). The most common birth defects potentially associated with Zika were microcephaly and brain abnormalities (14 cases), 4 brain abnormalities without microcephaly, and 4 cases of microcephaly and no reported neuroimaging. Overall, microcephaly was present in 4% of completed pregnancies.

Other potentially Zika-related complications included intracranial calcifications, corpus callosum abnormalities, abnormal cortical formation, cerebral atrophy, ventriculomegaly, hydrocephaly, and cerebellar abnormalities, the researchers wrote.

The women ranged in age from 15 to 50 years, and the population included 395 live births (21 infants with birth defects) and 47 pregnancy losses (5 fetuses with birth defects).

“No birth defects were reported among the pregnancies with maternal symptoms or exposure only in the second trimester or third trimester,” the researchers noted, “but there are insufficient data to adequately estimate the proportion affected during these trimesters,” they wrote.

Long-term monitoring of infants with possible congenital Zika virus is essential, the researchers wrote, as some normocephalic infants develop adverse effects of the virus not present at birth.

“In addition, future observations can elucidate the possible role of Zika virus infection in other outcomes, including spontaneous abortions and stillbirths as well as other structural birth defects that are not currently part of the inclusion criteria for Zika-associated birth defects surveillance,” they noted.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Approximately 6% of fetuses or infants of women with possible Zika virus infections at any point during pregnancy showed signs of Zika-related birth defects, but the number increased to 11% among women with Zika infections during the first trimester.

Data source: A review of data from 442 completed pregnancies collected via the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FDA warning: General anesthetics may damage young brains

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning that repeated or lengthy use of general anesthetic and sedation drugs during surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years or in pregnant women during their third trimester may affect the development of children’s brains.

“Recent human studies suggest that a single, relatively short exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs in infants or toddlers is unlikely to have negative effects on behavior or learning.” The studies suggesting a problem with longer or repeat exposures “had limitations, and it is unclear whether any negative effects seen in children’s learning or behavior were due to the drugs or to other factors, such as the underlying medical condition that led to the need for the surgery or procedure.” Further research is needed, the agency said.

FDA is adding its warning to the labels of 11 general anesthetics and sedatives, including desflurane, halothane, ketamine, lorazepam injection, methohexital, pentobarbital, and propofol. The drugs block N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and/or potentiate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. No specific medications have been shown to be safer than any other, the agency said.

FDA will continue to monitor the situation, and update its warning as additional information comes in. “We urge health care professionals, patients, parents, and caregivers to report side effects involving anesthetic and sedation drugs or other medicines to the FDA MedWatch program,” the FDA said.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning that repeated or lengthy use of general anesthetic and sedation drugs during surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years or in pregnant women during their third trimester may affect the development of children’s brains.

“Recent human studies suggest that a single, relatively short exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs in infants or toddlers is unlikely to have negative effects on behavior or learning.” The studies suggesting a problem with longer or repeat exposures “had limitations, and it is unclear whether any negative effects seen in children’s learning or behavior were due to the drugs or to other factors, such as the underlying medical condition that led to the need for the surgery or procedure.” Further research is needed, the agency said.

FDA is adding its warning to the labels of 11 general anesthetics and sedatives, including desflurane, halothane, ketamine, lorazepam injection, methohexital, pentobarbital, and propofol. The drugs block N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and/or potentiate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. No specific medications have been shown to be safer than any other, the agency said.

FDA will continue to monitor the situation, and update its warning as additional information comes in. “We urge health care professionals, patients, parents, and caregivers to report side effects involving anesthetic and sedation drugs or other medicines to the FDA MedWatch program,” the FDA said.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning that repeated or lengthy use of general anesthetic and sedation drugs during surgeries or procedures in children younger than 3 years or in pregnant women during their third trimester may affect the development of children’s brains.

“Recent human studies suggest that a single, relatively short exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs in infants or toddlers is unlikely to have negative effects on behavior or learning.” The studies suggesting a problem with longer or repeat exposures “had limitations, and it is unclear whether any negative effects seen in children’s learning or behavior were due to the drugs or to other factors, such as the underlying medical condition that led to the need for the surgery or procedure.” Further research is needed, the agency said.

FDA is adding its warning to the labels of 11 general anesthetics and sedatives, including desflurane, halothane, ketamine, lorazepam injection, methohexital, pentobarbital, and propofol. The drugs block N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and/or potentiate gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. No specific medications have been shown to be safer than any other, the agency said.

FDA will continue to monitor the situation, and update its warning as additional information comes in. “We urge health care professionals, patients, parents, and caregivers to report side effects involving anesthetic and sedation drugs or other medicines to the FDA MedWatch program,” the FDA said.

Is better reporting to blame for the rise maternal mortality rates?

Better surveillance could be responsible for increased rates of U.S. maternal mortality, a sign that previous estimates were too low, according to a new study.

For more than 2 decades, rates of maternal deaths have increased significantly, climbing from 7.55 per 100,000 live births in 1993 to 9.88 in 1999, and rising again to 21.5 in 2014. This means the relative risk of maternal death between 2014 and 1993 was 2.84, while it was 2.17 between 2014 and 1999.

Although rising rates of obesity and other chronic conditions are often theorized as possible factors in the spiking maternal death rates K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his colleagues suggest the more likely causes are improved maternal death surveillance and changes in how these deaths are coded.

This conclusion is based on a retrospective cohort analysis of maternal deaths and live births from 1993-2014 as recorded in the National Center for Health Statistics and the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research files of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:91-100).

Surveillance and reporting changes have been implemented across the country over the last few decades. During the 1990s, some states began including a separate question regarding pregnancy on death certificates. Starting in 2003, pregnancy was added to the standardized checklist of causes of death on certificates used nationwide, although state-by-state implementation has varied. In addition, in 1999, ICD-10 codes for underlying causes of death were introduced, including O96 and O97 for late maternal deaths, O26.8 for specified pregnancy-related conditions, and O99 for other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere.

When Dr. Joseph and his colleagues excluded from their analysis maternal deaths coded according to the new ICD-10 codes primarily related to renal disease and other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere, the increase between 1999 and 2014 was erased, dropping the relative risk to 1.09 (95% CI, 0.94-1.27).

Adjustment for improvements in surveillance also wiped out the temporal increase in maternal mortality rates for a relative risk of 1.06 for 2013 compared to 1993 (95% CI, 0.90-1.25).

“Reports of temporal increases in maternal mortality rates in the United States have led to shock and soul-searching by clinicians,” the investigators wrote. “In fact, maternal deaths from conditions historically associated with high case fatality rates including preeclampsia, eclampsia, complications of labor and delivery, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and abortion either declined substantially or remained stable between 1999 and 2014.”

The investigators did not report having any potential conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Better surveillance could be responsible for increased rates of U.S. maternal mortality, a sign that previous estimates were too low, according to a new study.

For more than 2 decades, rates of maternal deaths have increased significantly, climbing from 7.55 per 100,000 live births in 1993 to 9.88 in 1999, and rising again to 21.5 in 2014. This means the relative risk of maternal death between 2014 and 1993 was 2.84, while it was 2.17 between 2014 and 1999.

Although rising rates of obesity and other chronic conditions are often theorized as possible factors in the spiking maternal death rates K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his colleagues suggest the more likely causes are improved maternal death surveillance and changes in how these deaths are coded.

This conclusion is based on a retrospective cohort analysis of maternal deaths and live births from 1993-2014 as recorded in the National Center for Health Statistics and the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research files of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:91-100).

Surveillance and reporting changes have been implemented across the country over the last few decades. During the 1990s, some states began including a separate question regarding pregnancy on death certificates. Starting in 2003, pregnancy was added to the standardized checklist of causes of death on certificates used nationwide, although state-by-state implementation has varied. In addition, in 1999, ICD-10 codes for underlying causes of death were introduced, including O96 and O97 for late maternal deaths, O26.8 for specified pregnancy-related conditions, and O99 for other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere.

When Dr. Joseph and his colleagues excluded from their analysis maternal deaths coded according to the new ICD-10 codes primarily related to renal disease and other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere, the increase between 1999 and 2014 was erased, dropping the relative risk to 1.09 (95% CI, 0.94-1.27).

Adjustment for improvements in surveillance also wiped out the temporal increase in maternal mortality rates for a relative risk of 1.06 for 2013 compared to 1993 (95% CI, 0.90-1.25).

“Reports of temporal increases in maternal mortality rates in the United States have led to shock and soul-searching by clinicians,” the investigators wrote. “In fact, maternal deaths from conditions historically associated with high case fatality rates including preeclampsia, eclampsia, complications of labor and delivery, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and abortion either declined substantially or remained stable between 1999 and 2014.”

The investigators did not report having any potential conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Better surveillance could be responsible for increased rates of U.S. maternal mortality, a sign that previous estimates were too low, according to a new study.

For more than 2 decades, rates of maternal deaths have increased significantly, climbing from 7.55 per 100,000 live births in 1993 to 9.88 in 1999, and rising again to 21.5 in 2014. This means the relative risk of maternal death between 2014 and 1993 was 2.84, while it was 2.17 between 2014 and 1999.

Although rising rates of obesity and other chronic conditions are often theorized as possible factors in the spiking maternal death rates K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his colleagues suggest the more likely causes are improved maternal death surveillance and changes in how these deaths are coded.

This conclusion is based on a retrospective cohort analysis of maternal deaths and live births from 1993-2014 as recorded in the National Center for Health Statistics and the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research files of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:91-100).

Surveillance and reporting changes have been implemented across the country over the last few decades. During the 1990s, some states began including a separate question regarding pregnancy on death certificates. Starting in 2003, pregnancy was added to the standardized checklist of causes of death on certificates used nationwide, although state-by-state implementation has varied. In addition, in 1999, ICD-10 codes for underlying causes of death were introduced, including O96 and O97 for late maternal deaths, O26.8 for specified pregnancy-related conditions, and O99 for other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere.

When Dr. Joseph and his colleagues excluded from their analysis maternal deaths coded according to the new ICD-10 codes primarily related to renal disease and other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere, the increase between 1999 and 2014 was erased, dropping the relative risk to 1.09 (95% CI, 0.94-1.27).

Adjustment for improvements in surveillance also wiped out the temporal increase in maternal mortality rates for a relative risk of 1.06 for 2013 compared to 1993 (95% CI, 0.90-1.25).

“Reports of temporal increases in maternal mortality rates in the United States have led to shock and soul-searching by clinicians,” the investigators wrote. “In fact, maternal deaths from conditions historically associated with high case fatality rates including preeclampsia, eclampsia, complications of labor and delivery, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and abortion either declined substantially or remained stable between 1999 and 2014.”

The investigators did not report having any potential conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The relative risk for maternal death was 2.17 between 1999 and 2014, but dropped to 1.09 when certain new ICD-10 codes were excluded.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of maternal deaths recorded in federal health data from 1993-2004.

Disclosures: The investigators did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Increasing maternal vaccine uptake requires paradigm shift

ATLANTA – Both the influenza and the tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines have been recommended during pregnancy for years, but uptake remains low.

The most recent national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the Tdap vaccination rate is about 14% before pregnancy and 10% during pregnancy. For influenza, the vaccination rate among pregnant women is about 50%, with 14% of women being vaccinated in the 6 months before pregnancy and 36% during pregnancy.

To get a handle on how ob.gyn. practices approach vaccination, Dr. O’Leary and his colleagues sent out a mail and Internet survey to 482 physicians from June through September 2015 and analyzed 353 responses.

Among the responders, 92% routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received the Tdap vaccine, and 98% routinely assessed whether pregnant patients had received the influenza vaccine. But only about half of the physicians (51%) assessed Tdap vaccination in nonpregnant patients, and 82% assessed influenza vaccine status in nonpregnant patients.

For the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, ob.gyns. were more likely to ask their nonpregnant patients about the vaccine. A total of 46% of providers routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received it, while 92% assessed whether their nonpregnant patients needed or had received the HPV vaccine.

The numbers were lower when it came to actually administering the vaccines. Just over three-quarters of providers routinely administered the Tdap vaccine, and 85% routinely administered the influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients.

For their nonpregnant patients, 55% routinely administered Tdap, 70% routinely administered the flu vaccine, and 82% routinely administered the HPV vaccine.

Ob.gyns. were most likely to have standing orders in place for influenza vaccine for their pregnant patients, with 66% of providers reporting that they had these orders in place, compared with 51% for nonpregnant patients. Standing orders were less likely for Tdap vaccine administration (39% for pregnant patients and 37% for nonpregnant patients).

Barriers

Reimbursement-related issues topped the reasons that ob.gyns. found it burdensome to stock and administer vaccines. The most commonly reported barrier – cited by 54% of the respondents – was lack of adequate reimbursement for purchasing vaccines, and 30% of physicians cited this as a major barrier. Similarly, lack of adequate reimbursement for administration of the vaccine was listed as a major barrier for a quarter of the respondents and a moderate barrier by 21% of the respondents.

A quarter of physicians also cited difficulty determining if a patient’s insurance would reimburse for a vaccine as a major barrier.

Other barriers included having too little time for vaccination during visits when other preventive services took precedence, having patients who refused vaccines because of safety concerns, the burden of storing, ordering, and tracking vaccines, and difficulty determining whether a patient had already received a particular vaccine.

Fewer than 2% of ob.gyns., however, reported uncertainty about a particular vaccine’s effectiveness or safety in pregnant women as a barrier.

“Physician attitudinal barriers are nonexistent,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The perceived barriers were primarily financial, but logistical and patient attitudinal barriers were also important.”

Testing interventions

While the barriers to routine vaccine administration are clear, the solutions are less obvious. A recently reported intensive intervention to increase the uptake of maternal vaccines in ob.gyn. practices had only modest success in increasing Tdap vaccination and no significant impact on administration of the influenza vaccine.

“Immunization delivery in the ob.gyn. setting may present different challenges than more traditional settings for adult vaccination, such as family medicine or internal medicine offices,” Dr. O’Leary said.

The study involved eight ob.gyn. practices in Colorado and ran from August 2011 through March 2014, a period during which the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices recommended that Tdap vaccination be given in every pregnancy.

Four ob.gyn. practices – one rural and three urban – were randomly assigned to usual care while the other four – two rural and two urban – were randomly assigned to the intervention. The practices were balanced in terms of their number of providers, the proportion of Medicaid patients they served, the number of deliveries per month, and an immunization delivery score at baseline.

The researchers assessed receipt of influenza vaccines among women pregnant during the previous influenza season and receipt of the Tdap vaccine among women at at least 34 weeks’ gestation. There were 13,324 patients in the control arm and 12,103 patients in the intervention arm.

The multimodal intervention involved seven components:

1. Designating immunization champions at each practice.

2. Assisting with vaccine purchasing and management.

3. Historical vaccination documentation training.

4. Implementing standing orders for both vaccines.

5. Chart review and feedback.

6. Patient/staff education materials and training.

7. Frequent contact with the project team, at least once a month during the study period.

At baseline, the rate of Tdap vaccination among pregnant women was 3% in the intervention clinics and 11% in the control clinics. During year 2, following the intervention, 38% of women at the intervention clinics and 34% of the women at the control clinics had received the Tdap vaccine. Those increases translated to a four times greater likelihood of getting the Tdap vaccine among women at clinics who underwent the intervention (risk ratio, 3.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-13.3).

Influenza vaccine uptake also increased collectively at the clinics, from 19% at intervention clinics and 18% at control clinics at baseline, to 21% at intervention clinics and 25% at control clinics a year later. But there was no significant difference in uptake between the intervention and control clinics.

An additional qualitative component of the study involved hour-long interviews with staff members from six of the clinics to assess specific components of the intervention, such as implementing standing orders for each vaccine.

“Prior to establishing standing orders at practices, the responsibility for assessing immunization history and eligibility had fallen to the medical providers,” Dr. O’Leary said. “By establishing standing orders for immunizations, providers and staff reported overall improved immunization delivery to their patient population.”

But barriers existed for standing orders as well, including patient reluctance to receive the vaccine without first discussing it with her physician.

The qualitative interviews also revealed that some nurses may have felt anxious about administering vaccines to pregnant women until they received vaccine education. Overall, staff education and implementation of standing orders were well received at the intervention practices.

“Adding immunization questions to standard intake forms was an efficient and effective method to collect immunization history that fit into already established patient check-in processes,” Dr. O’Leary said.

Standing order templates could also be customized to each practice’s processes, and the process of the staff reviewing these templates often led to consensus about how to integrate the orders into routine care, according to Dr. O’Leary.

“To increase the uptake of vaccinations in pregnancy, all ob.gyns. need to stock and administer influenza and Tdap vaccines,” Dr. O’Leary said. “And if ob.gyns. are to play a significant role as vaccinators of nonpregnant women, a paradigm shift is required.”

Both studies were funded by the CDC. Dr. O’Leary reported having no relevant financial disclosures, but one of the coinvestigators in the intervention study reported financial relationships with Merck and Pfizer.

ATLANTA – Both the influenza and the tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines have been recommended during pregnancy for years, but uptake remains low.

The most recent national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the Tdap vaccination rate is about 14% before pregnancy and 10% during pregnancy. For influenza, the vaccination rate among pregnant women is about 50%, with 14% of women being vaccinated in the 6 months before pregnancy and 36% during pregnancy.

To get a handle on how ob.gyn. practices approach vaccination, Dr. O’Leary and his colleagues sent out a mail and Internet survey to 482 physicians from June through September 2015 and analyzed 353 responses.

Among the responders, 92% routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received the Tdap vaccine, and 98% routinely assessed whether pregnant patients had received the influenza vaccine. But only about half of the physicians (51%) assessed Tdap vaccination in nonpregnant patients, and 82% assessed influenza vaccine status in nonpregnant patients.

For the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, ob.gyns. were more likely to ask their nonpregnant patients about the vaccine. A total of 46% of providers routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received it, while 92% assessed whether their nonpregnant patients needed or had received the HPV vaccine.

The numbers were lower when it came to actually administering the vaccines. Just over three-quarters of providers routinely administered the Tdap vaccine, and 85% routinely administered the influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients.

For their nonpregnant patients, 55% routinely administered Tdap, 70% routinely administered the flu vaccine, and 82% routinely administered the HPV vaccine.

Ob.gyns. were most likely to have standing orders in place for influenza vaccine for their pregnant patients, with 66% of providers reporting that they had these orders in place, compared with 51% for nonpregnant patients. Standing orders were less likely for Tdap vaccine administration (39% for pregnant patients and 37% for nonpregnant patients).

Barriers

Reimbursement-related issues topped the reasons that ob.gyns. found it burdensome to stock and administer vaccines. The most commonly reported barrier – cited by 54% of the respondents – was lack of adequate reimbursement for purchasing vaccines, and 30% of physicians cited this as a major barrier. Similarly, lack of adequate reimbursement for administration of the vaccine was listed as a major barrier for a quarter of the respondents and a moderate barrier by 21% of the respondents.

A quarter of physicians also cited difficulty determining if a patient’s insurance would reimburse for a vaccine as a major barrier.

Other barriers included having too little time for vaccination during visits when other preventive services took precedence, having patients who refused vaccines because of safety concerns, the burden of storing, ordering, and tracking vaccines, and difficulty determining whether a patient had already received a particular vaccine.

Fewer than 2% of ob.gyns., however, reported uncertainty about a particular vaccine’s effectiveness or safety in pregnant women as a barrier.

“Physician attitudinal barriers are nonexistent,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The perceived barriers were primarily financial, but logistical and patient attitudinal barriers were also important.”

Testing interventions

While the barriers to routine vaccine administration are clear, the solutions are less obvious. A recently reported intensive intervention to increase the uptake of maternal vaccines in ob.gyn. practices had only modest success in increasing Tdap vaccination and no significant impact on administration of the influenza vaccine.

“Immunization delivery in the ob.gyn. setting may present different challenges than more traditional settings for adult vaccination, such as family medicine or internal medicine offices,” Dr. O’Leary said.

The study involved eight ob.gyn. practices in Colorado and ran from August 2011 through March 2014, a period during which the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices recommended that Tdap vaccination be given in every pregnancy.

Four ob.gyn. practices – one rural and three urban – were randomly assigned to usual care while the other four – two rural and two urban – were randomly assigned to the intervention. The practices were balanced in terms of their number of providers, the proportion of Medicaid patients they served, the number of deliveries per month, and an immunization delivery score at baseline.

The researchers assessed receipt of influenza vaccines among women pregnant during the previous influenza season and receipt of the Tdap vaccine among women at at least 34 weeks’ gestation. There were 13,324 patients in the control arm and 12,103 patients in the intervention arm.

The multimodal intervention involved seven components:

1. Designating immunization champions at each practice.

2. Assisting with vaccine purchasing and management.

3. Historical vaccination documentation training.

4. Implementing standing orders for both vaccines.

5. Chart review and feedback.

6. Patient/staff education materials and training.

7. Frequent contact with the project team, at least once a month during the study period.

At baseline, the rate of Tdap vaccination among pregnant women was 3% in the intervention clinics and 11% in the control clinics. During year 2, following the intervention, 38% of women at the intervention clinics and 34% of the women at the control clinics had received the Tdap vaccine. Those increases translated to a four times greater likelihood of getting the Tdap vaccine among women at clinics who underwent the intervention (risk ratio, 3.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-13.3).

Influenza vaccine uptake also increased collectively at the clinics, from 19% at intervention clinics and 18% at control clinics at baseline, to 21% at intervention clinics and 25% at control clinics a year later. But there was no significant difference in uptake between the intervention and control clinics.

An additional qualitative component of the study involved hour-long interviews with staff members from six of the clinics to assess specific components of the intervention, such as implementing standing orders for each vaccine.

“Prior to establishing standing orders at practices, the responsibility for assessing immunization history and eligibility had fallen to the medical providers,” Dr. O’Leary said. “By establishing standing orders for immunizations, providers and staff reported overall improved immunization delivery to their patient population.”

But barriers existed for standing orders as well, including patient reluctance to receive the vaccine without first discussing it with her physician.

The qualitative interviews also revealed that some nurses may have felt anxious about administering vaccines to pregnant women until they received vaccine education. Overall, staff education and implementation of standing orders were well received at the intervention practices.

“Adding immunization questions to standard intake forms was an efficient and effective method to collect immunization history that fit into already established patient check-in processes,” Dr. O’Leary said.

Standing order templates could also be customized to each practice’s processes, and the process of the staff reviewing these templates often led to consensus about how to integrate the orders into routine care, according to Dr. O’Leary.

“To increase the uptake of vaccinations in pregnancy, all ob.gyns. need to stock and administer influenza and Tdap vaccines,” Dr. O’Leary said. “And if ob.gyns. are to play a significant role as vaccinators of nonpregnant women, a paradigm shift is required.”

Both studies were funded by the CDC. Dr. O’Leary reported having no relevant financial disclosures, but one of the coinvestigators in the intervention study reported financial relationships with Merck and Pfizer.

ATLANTA – Both the influenza and the tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines have been recommended during pregnancy for years, but uptake remains low.

The most recent national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the Tdap vaccination rate is about 14% before pregnancy and 10% during pregnancy. For influenza, the vaccination rate among pregnant women is about 50%, with 14% of women being vaccinated in the 6 months before pregnancy and 36% during pregnancy.

To get a handle on how ob.gyn. practices approach vaccination, Dr. O’Leary and his colleagues sent out a mail and Internet survey to 482 physicians from June through September 2015 and analyzed 353 responses.

Among the responders, 92% routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received the Tdap vaccine, and 98% routinely assessed whether pregnant patients had received the influenza vaccine. But only about half of the physicians (51%) assessed Tdap vaccination in nonpregnant patients, and 82% assessed influenza vaccine status in nonpregnant patients.

For the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, ob.gyns. were more likely to ask their nonpregnant patients about the vaccine. A total of 46% of providers routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received it, while 92% assessed whether their nonpregnant patients needed or had received the HPV vaccine.

The numbers were lower when it came to actually administering the vaccines. Just over three-quarters of providers routinely administered the Tdap vaccine, and 85% routinely administered the influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients.

For their nonpregnant patients, 55% routinely administered Tdap, 70% routinely administered the flu vaccine, and 82% routinely administered the HPV vaccine.

Ob.gyns. were most likely to have standing orders in place for influenza vaccine for their pregnant patients, with 66% of providers reporting that they had these orders in place, compared with 51% for nonpregnant patients. Standing orders were less likely for Tdap vaccine administration (39% for pregnant patients and 37% for nonpregnant patients).

Barriers

Reimbursement-related issues topped the reasons that ob.gyns. found it burdensome to stock and administer vaccines. The most commonly reported barrier – cited by 54% of the respondents – was lack of adequate reimbursement for purchasing vaccines, and 30% of physicians cited this as a major barrier. Similarly, lack of adequate reimbursement for administration of the vaccine was listed as a major barrier for a quarter of the respondents and a moderate barrier by 21% of the respondents.

A quarter of physicians also cited difficulty determining if a patient’s insurance would reimburse for a vaccine as a major barrier.

Other barriers included having too little time for vaccination during visits when other preventive services took precedence, having patients who refused vaccines because of safety concerns, the burden of storing, ordering, and tracking vaccines, and difficulty determining whether a patient had already received a particular vaccine.

Fewer than 2% of ob.gyns., however, reported uncertainty about a particular vaccine’s effectiveness or safety in pregnant women as a barrier.

“Physician attitudinal barriers are nonexistent,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The perceived barriers were primarily financial, but logistical and patient attitudinal barriers were also important.”

Testing interventions

While the barriers to routine vaccine administration are clear, the solutions are less obvious. A recently reported intensive intervention to increase the uptake of maternal vaccines in ob.gyn. practices had only modest success in increasing Tdap vaccination and no significant impact on administration of the influenza vaccine.

“Immunization delivery in the ob.gyn. setting may present different challenges than more traditional settings for adult vaccination, such as family medicine or internal medicine offices,” Dr. O’Leary said.

The study involved eight ob.gyn. practices in Colorado and ran from August 2011 through March 2014, a period during which the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices recommended that Tdap vaccination be given in every pregnancy.

Four ob.gyn. practices – one rural and three urban – were randomly assigned to usual care while the other four – two rural and two urban – were randomly assigned to the intervention. The practices were balanced in terms of their number of providers, the proportion of Medicaid patients they served, the number of deliveries per month, and an immunization delivery score at baseline.

The researchers assessed receipt of influenza vaccines among women pregnant during the previous influenza season and receipt of the Tdap vaccine among women at at least 34 weeks’ gestation. There were 13,324 patients in the control arm and 12,103 patients in the intervention arm.

The multimodal intervention involved seven components:

1. Designating immunization champions at each practice.

2. Assisting with vaccine purchasing and management.

3. Historical vaccination documentation training.

4. Implementing standing orders for both vaccines.

5. Chart review and feedback.

6. Patient/staff education materials and training.

7. Frequent contact with the project team, at least once a month during the study period.

At baseline, the rate of Tdap vaccination among pregnant women was 3% in the intervention clinics and 11% in the control clinics. During year 2, following the intervention, 38% of women at the intervention clinics and 34% of the women at the control clinics had received the Tdap vaccine. Those increases translated to a four times greater likelihood of getting the Tdap vaccine among women at clinics who underwent the intervention (risk ratio, 3.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-13.3).

Influenza vaccine uptake also increased collectively at the clinics, from 19% at intervention clinics and 18% at control clinics at baseline, to 21% at intervention clinics and 25% at control clinics a year later. But there was no significant difference in uptake between the intervention and control clinics.