User login

LMWH doesn’t reduce late pregnancy loss in women with thrombophilias

Prophylactic-dose low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), with or without aspirin, did not reduce the risk of pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss, based on a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest study published to date that evaluates LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and previous pregnancy loss,” Dr. Leslie Skeith, of the University of Ottawa, and her colleagues wrote in Blood (2016 Mar 31;127[13]:1650-55). A recent Cochrane Review (2014 Jul 4;7:CD004734) similarly found no difference in live birth rates in women with or without inherited thrombophilia treated with LMWH and aspirin, compared with women given no treatment. Additionally, the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction [EAGeR] trial found no difference in live birth rates in women with previous pregnancy loss given aspirin or placebo (Lancet. 2014;384[9937]:29-36).

Based on a literature search, 8 publications and 483 participants met eligibility criteria as randomized, controlled trials for the meta-analysis. Four trials included an LMWH-plus-aspirin arm, and five trials included an LMWH-only arm. The control groups included four trials with an aspirin arm, and five trials with a placebo or no-treatment arm. The data indicated no difference in the treated groups and controls (relative risk of 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-1.19; P = .28).

As there is the potential for adverse side effects and significant cost with LMWH, the researchers advise against the use of LMWH to prevent recurrent and prior late pregnancy loss (greater than 10 weeks gestation) in women with inherited thrombophilia (Grade 1B, strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence) and suggest against LMWH to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior recurrent early (less than 10 weeks) pregnancy loss. (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence.)

Given that the analysis included just 66 women with thrombophilia and prior recurrent early pregnancy loss, the researchers could not exclude a beneficial effect of LMWH in this subgroup. An ongoing randomized controlled trial, ALIFE2 (Netherlands Trial Registration Identifier: NTR3361), “is evaluating LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of two or more miscarriages and/or intrauterine fetal death, which we hope will provide definitive answers to this question,” the researchers wrote.

They also suggest not testing for inherited thrombophilia in women with prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence).

The study was supported by a series of university and institutional investigator research awards. Dr. Skeith received a Thrombosis Canada CanVECTOR Research Fellowship award.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Prophylactic-dose low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), with or without aspirin, did not reduce the risk of pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss, based on a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest study published to date that evaluates LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and previous pregnancy loss,” Dr. Leslie Skeith, of the University of Ottawa, and her colleagues wrote in Blood (2016 Mar 31;127[13]:1650-55). A recent Cochrane Review (2014 Jul 4;7:CD004734) similarly found no difference in live birth rates in women with or without inherited thrombophilia treated with LMWH and aspirin, compared with women given no treatment. Additionally, the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction [EAGeR] trial found no difference in live birth rates in women with previous pregnancy loss given aspirin or placebo (Lancet. 2014;384[9937]:29-36).

Based on a literature search, 8 publications and 483 participants met eligibility criteria as randomized, controlled trials for the meta-analysis. Four trials included an LMWH-plus-aspirin arm, and five trials included an LMWH-only arm. The control groups included four trials with an aspirin arm, and five trials with a placebo or no-treatment arm. The data indicated no difference in the treated groups and controls (relative risk of 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-1.19; P = .28).

As there is the potential for adverse side effects and significant cost with LMWH, the researchers advise against the use of LMWH to prevent recurrent and prior late pregnancy loss (greater than 10 weeks gestation) in women with inherited thrombophilia (Grade 1B, strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence) and suggest against LMWH to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior recurrent early (less than 10 weeks) pregnancy loss. (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence.)

Given that the analysis included just 66 women with thrombophilia and prior recurrent early pregnancy loss, the researchers could not exclude a beneficial effect of LMWH in this subgroup. An ongoing randomized controlled trial, ALIFE2 (Netherlands Trial Registration Identifier: NTR3361), “is evaluating LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of two or more miscarriages and/or intrauterine fetal death, which we hope will provide definitive answers to this question,” the researchers wrote.

They also suggest not testing for inherited thrombophilia in women with prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence).

The study was supported by a series of university and institutional investigator research awards. Dr. Skeith received a Thrombosis Canada CanVECTOR Research Fellowship award.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Prophylactic-dose low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), with or without aspirin, did not reduce the risk of pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss, based on a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest study published to date that evaluates LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and previous pregnancy loss,” Dr. Leslie Skeith, of the University of Ottawa, and her colleagues wrote in Blood (2016 Mar 31;127[13]:1650-55). A recent Cochrane Review (2014 Jul 4;7:CD004734) similarly found no difference in live birth rates in women with or without inherited thrombophilia treated with LMWH and aspirin, compared with women given no treatment. Additionally, the Effects of Aspirin in Gestation and Reproduction [EAGeR] trial found no difference in live birth rates in women with previous pregnancy loss given aspirin or placebo (Lancet. 2014;384[9937]:29-36).

Based on a literature search, 8 publications and 483 participants met eligibility criteria as randomized, controlled trials for the meta-analysis. Four trials included an LMWH-plus-aspirin arm, and five trials included an LMWH-only arm. The control groups included four trials with an aspirin arm, and five trials with a placebo or no-treatment arm. The data indicated no difference in the treated groups and controls (relative risk of 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-1.19; P = .28).

As there is the potential for adverse side effects and significant cost with LMWH, the researchers advise against the use of LMWH to prevent recurrent and prior late pregnancy loss (greater than 10 weeks gestation) in women with inherited thrombophilia (Grade 1B, strong recommendation with moderate-quality evidence) and suggest against LMWH to prevent recurrent pregnancy loss in women with inherited thrombophilia and prior recurrent early (less than 10 weeks) pregnancy loss. (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence.)

Given that the analysis included just 66 women with thrombophilia and prior recurrent early pregnancy loss, the researchers could not exclude a beneficial effect of LMWH in this subgroup. An ongoing randomized controlled trial, ALIFE2 (Netherlands Trial Registration Identifier: NTR3361), “is evaluating LMWH in women with inherited thrombophilia and a history of two or more miscarriages and/or intrauterine fetal death, which we hope will provide definitive answers to this question,” the researchers wrote.

They also suggest not testing for inherited thrombophilia in women with prior late or recurrent early pregnancy loss (Grade 2B, weak recommendation with moderate-quality evidence).

The study was supported by a series of university and institutional investigator research awards. Dr. Skeith received a Thrombosis Canada CanVECTOR Research Fellowship award.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: Given the potential for adverse side effects and significant cost, the researchers advise against the use of LMWH to prevent recurrent and prior late pregnancy loss (greater than 10 weeks gestation) in women with inherited thrombophilia.

Major finding: The data indicated no difference in the treated groups and controls (relative risk of 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.55-1.19; P = .28).

Data source: Based on a literature search, 8 publications and 483 participants met eligibility criteria as randomized, controlled trials for the meta-analysis.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a series of university and institutional investigator research awards. Dr. Skeith received a Thrombosis Canada CanVECTOR Research Fellowship award.

Intractable shoulder dystocia: A posterior axilla maneuver may save the day

Shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable obstetric emergency that challenges all obstetricians and midwives. In response to a shoulder dystocia emergency, most clinicians implement a sequence of well-practiced steps that begin with early recognition of the problem, clear communication of the emergency with delivery room staff, and a call for help to available clinicians. Management steps may include:

- instructing the mother to stop pushing and moving the mother's buttocks to the edge of the bed

- ensuring there is not a tight nuchal cord

- committing to avoiding the use of excessive force on the fetal head and neck

- considering performing an episiotomy

- performing the McRoberts maneuver combined with suprapubic pressure

- using a rotational maneuver, such as the Woods maneuver or the Rubin maneuver

- delivering the posterior arm

- considering the Gaskin all-four maneuver.

When initial management steps are not enoughIf this sequence of steps does not result in successful vaginal delivery, additional options include: clavicle fracture, cephalic replacement followed by cesarean delivery (Zavanelli maneuver), symphysiotomy, or fundal pressure combined with a rotational maneuver. Another simple intervention that is not discussed widely in medical textbooks or taught during training is the posterior axilla maneuver.

Posterior axilla maneuversVarying posterior axilla maneuvers have been described by many expert obstetricians, including Willughby (17th Century),1 Holman (1963),2 Schramm (1983),3 Menticoglou (2006),4 and Hofmeyr and Cluver (2009, 2015).5−7

Willughby maneuverPercival Willughby’s (1596−1685) description of a posterior axilla maneuver was brief1:

After the head is born, if the child through the greatness of the shoulders, should stick at the neck, let the midwife put her fingers under the child's armpit and give it a nudge, thrusting it to the other side with her finger, drawing the child or she may quickly bring forth the shoulders, without offering to put it forth by her hands clasped about the neck, which might endanger the breaking of the neck.

Holman maneuverHolman described a maneuver with the following steps2:

- perform an episiotomy

- place a finger in the posterior axilla and draw the posterior shoulder down along the pelvic axis

- simultaneously have an assistant perform suprapubic pressure and

- if necessary, insert two supinated fingers under the pubic arch and press and rock the anterior shoulder, tilting the anterior shoulder toward the hollow of the sacrum while simultaneously gently pulling the posterior axilla along the pelvic axis.

Schramm maneuverSchramm, working with a population enriched with women with diabetes, frequently encountered shoulder dystocia and recommended3:

If the posterior axilla can be reached—in other words, if the posterior shoulder is engaged—in my experience it can always be delivered by rotating it to the anterior position while at the same time applying traction....I normally place 1 or 2 fingers of my right hand in the posterior axilla and “scruff” the neck with my left hand, applying both rotation and traction. Because this grip is somewhat insecure, the resultant tractive force is limited and I consider this manoeuvre to be the most effective and least traumatic method of relieving moderate to severe obstruction.

Practice your shoulder dystocia maneuvers using simulation

Obstetric emergencies trigger a rush of adrenaline and great stress for the obstetrician and delivery room team. This may adversely impact motor performance, decision making, and communication skills.1 Low- and high-fidelity simulation exercises create an environment in which the obstetrics team can practice the sequence of maneuvers and seamless teamwork needed to successfully resolve a shoulder dystocia.2,3 Implementing a shoulder dystocia protocol and practicing the protocol using team-based simulation may help to reduce the adverse outcomes of shoulder dystocia.3,4

Reference

1. Wetzel CM, Kneebone RL, Woloshynowych M, et al. The effects of stress on surgical performance. Am J Surg. 2006;191(1):5−10.

2. Crofts JF, Fox R, Ellis D, Winter C, Hinshaw K, Draycott TJ. Observations from 450 shoulder dystocia simulations. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):906−912.

3. Draycott TJ, Crofts JF, Ash JP, et al. Improving neonatal outcome through practical shoulder dystocia training. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):14−20.

4. Grobman WA, Miller D, Burke C, Hornbogen A, Tam K, Costello R. Outcomes associated with introduction of a shoulder dystocia protocol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(6):513−517.

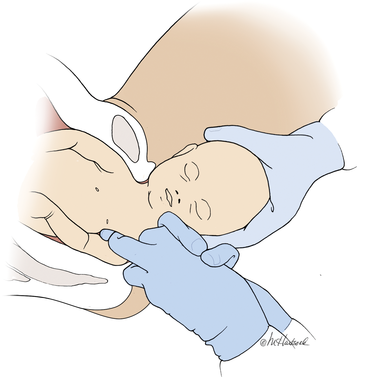

Manipulation of the posterior axilla |

|

The right and left third fingers are locked into the posterior axilla, one finger from the front and one from the back of the fetus. Gentle downward guidance is provided by the fingers to draw the posterior shoulder down and out along the curve of the sacrum, thus releasing the anterior shoulder.4 In this drawing, an assistant gently holds the head up. |

Menticoglou maneuverMenticoglou noted that delivery of the posterior arm generally resolves almost all cases of shoulder dystocia. However, if the posterior arm is extended and trapped between the fetus and maternal pelvic side-wall, it may be difficult to deliver the posterior arm. In these cases he recommended having an assistant gently hold, not pull, the fetal head upward and, at the same time, having the obstetrician get on one knee, placing the middle fingers of both hands into the posterior axilla of the fetus.4

The right middle finger is placed into the axilla from the left side of the maternal pelvis, and the left middle finger is placed into the axilla from the right side of the maternal pelvis, resulting in the two middle fingers overlapping in the fetal axilla (FIGURE).4 Gentle force is then used to pull the posterior shoulder and arm downward and outward along the curve of the sacrum. Once the shoulder has emerged from the pelvis, the posterior arm is delivered. Alternatively, if the posterior shoulder is brought well down into the pelvis, another attempt can be made at delivering the posterior arm.4

My preferred approach. The Menticoglou maneuver is my preferred posterior axilla maneuver because it can be accomplished rapidly; requires no equipment, such as a sling catheter; and the obstetrician has good tactile feedback throughout the application of gentle force.

Hofmeyr-Cluver maneuverIn cases of difficult shoulder dystocia, Dr. William Smellie (1762)8 recommended placing one or two fingers in the anterior or posterior fetal axilla and gentling pulling on the axilla to deliver the body. If the axillae were too high to reach, he recommended using a blunt hook in the axilla to draw forth the impacted child. He advised caution when using a blunt hook because the fetus might be injured or lacerated.

Instead of using a hook, Hofmeyr and Cluver5−7 have recommended using a catheter sling to deliver the posterior shoulder. In this maneuver, a loop of a suction catheter or firm urinary catheter is placed over the obstetrician’s index finger and the loop is pushed through the posterior axilla, back to front, with guidance from the index finger. The index finger of the opposite hand is used to catch the loop and pull the catheter through, creating a single-stranded sling that is positioned in the axilla. Gentle force is then applied to the sling in the axis of the pelvis to deliver the posterior shoulder.

“If the posterior arm does not follow it is then swept out easily because room has been created by delivering the posterior shoulder. If the aforementioned procedure fails, the sling can be used to rotate the shoulder. To perform a rotational maneuver, sling traction is directed laterally towards the side of the baby’s back then anteriorly while digital pressure is applied behind the anterior shoulder to assist rotation.”7

Use ACOG’s checklist for documenting a shoulder dystocia

Following the resolution of a shoulder dystocia, it is important to gather all the necessary facts to complete a detailed medical record entry describing the situation and interventions used. The checklist from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) helps you to prepare a standardized medical record entry that is comprehensive.

My experience is that “free form” medical record entries describing the events at a shoulder dystocia event are generally not optimally organized, creating future problems when the case is reviewed.

ACOG obstetric checklists are available for download at http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications, or use your web browser to search for “ACOG Shoulder Dystocia checklist.”

With scant literature, know the benefits and risksThe world’s literature on posterior axilla maneuvers to resolve shoulder dystocia consists of case series and individual case reports.2−7 Hence, the quality of the data supporting this intervention is not optimal, and risks associated with the maneuver are not well characterized. Application of a controlled and gentle force to the posterior axilla may cause fracture of the fetal humerus5 or dislocation of the fetal shoulder. The posterior axilla maneuver also may increase the risk of a maternal third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration.

As a general rule, as the number of maneuvers used to resolve a difficult shoulder dystocia increase, the risk of neonatal injury increases.9 Since the posterior axilla maneuver typically is only attempted after multiple previous maneuvers have failed, the risk of fetal injury is increased. However, as time passes and a shoulder dystocia remains unresolved for 4 or 5 minutes, the risk of neurologic injury and fetal death increases.10

In resolving a shoulder dystocia, speed and skill are essential. A posterior axilla maneuver can be performed more rapidly than a Zavanelli maneuver or a symphysiotomy. Although manipulation of the posterior axilla and arm may cause a fracture of the humerus, this complication is a modest price to pay for preventing permanent fetal brain injury or fetal death.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Willughby P. Observations in midwifery. New York, NY: MW Books; 1972:312−313.

- Holman MS. A new manoeuvre for delivery of an impacted shoulder based on a mechanical analysis. S Afr Med J. 1963;37:247−249.

- Schramm M. Impacted shoulders—a personal experience. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;23(1):28−31.

- Menticoglou SM. A modified technique to deliver the posterior arm in severe shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 pt 2):755−757.

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction: a technique for intractable shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):486–488.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Cluver CA. Posterior axilla sling traction for intractable shoulder dystocia. BJOG. 2009;116(13):1818−1820.

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction for shoulder dystocia: case review and a new method for shoulder rotation with the sling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):784.e1−e7.

- Smellie W. A treatise on the theory and practice of midwifery. 4th ed. London, England; 1762:226−227.

- Hoffman MK, Bailit JL, Branch DW, et al; Consortium on Safe Labor. A comparison of obstetric maneuvers for the acute management of shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1272−1278.

- Lerner H, Durlacher K, Smith S, Hamilton E. Relationship between head-to-body delivery interval in shoulder dystocia and neonatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):318−322.

Shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable obstetric emergency that challenges all obstetricians and midwives. In response to a shoulder dystocia emergency, most clinicians implement a sequence of well-practiced steps that begin with early recognition of the problem, clear communication of the emergency with delivery room staff, and a call for help to available clinicians. Management steps may include:

- instructing the mother to stop pushing and moving the mother's buttocks to the edge of the bed

- ensuring there is not a tight nuchal cord

- committing to avoiding the use of excessive force on the fetal head and neck

- considering performing an episiotomy

- performing the McRoberts maneuver combined with suprapubic pressure

- using a rotational maneuver, such as the Woods maneuver or the Rubin maneuver

- delivering the posterior arm

- considering the Gaskin all-four maneuver.

When initial management steps are not enoughIf this sequence of steps does not result in successful vaginal delivery, additional options include: clavicle fracture, cephalic replacement followed by cesarean delivery (Zavanelli maneuver), symphysiotomy, or fundal pressure combined with a rotational maneuver. Another simple intervention that is not discussed widely in medical textbooks or taught during training is the posterior axilla maneuver.

Posterior axilla maneuversVarying posterior axilla maneuvers have been described by many expert obstetricians, including Willughby (17th Century),1 Holman (1963),2 Schramm (1983),3 Menticoglou (2006),4 and Hofmeyr and Cluver (2009, 2015).5−7

Willughby maneuverPercival Willughby’s (1596−1685) description of a posterior axilla maneuver was brief1:

After the head is born, if the child through the greatness of the shoulders, should stick at the neck, let the midwife put her fingers under the child's armpit and give it a nudge, thrusting it to the other side with her finger, drawing the child or she may quickly bring forth the shoulders, without offering to put it forth by her hands clasped about the neck, which might endanger the breaking of the neck.

Holman maneuverHolman described a maneuver with the following steps2:

- perform an episiotomy

- place a finger in the posterior axilla and draw the posterior shoulder down along the pelvic axis

- simultaneously have an assistant perform suprapubic pressure and

- if necessary, insert two supinated fingers under the pubic arch and press and rock the anterior shoulder, tilting the anterior shoulder toward the hollow of the sacrum while simultaneously gently pulling the posterior axilla along the pelvic axis.

Schramm maneuverSchramm, working with a population enriched with women with diabetes, frequently encountered shoulder dystocia and recommended3:

If the posterior axilla can be reached—in other words, if the posterior shoulder is engaged—in my experience it can always be delivered by rotating it to the anterior position while at the same time applying traction....I normally place 1 or 2 fingers of my right hand in the posterior axilla and “scruff” the neck with my left hand, applying both rotation and traction. Because this grip is somewhat insecure, the resultant tractive force is limited and I consider this manoeuvre to be the most effective and least traumatic method of relieving moderate to severe obstruction.

Practice your shoulder dystocia maneuvers using simulation

Obstetric emergencies trigger a rush of adrenaline and great stress for the obstetrician and delivery room team. This may adversely impact motor performance, decision making, and communication skills.1 Low- and high-fidelity simulation exercises create an environment in which the obstetrics team can practice the sequence of maneuvers and seamless teamwork needed to successfully resolve a shoulder dystocia.2,3 Implementing a shoulder dystocia protocol and practicing the protocol using team-based simulation may help to reduce the adverse outcomes of shoulder dystocia.3,4

Reference

1. Wetzel CM, Kneebone RL, Woloshynowych M, et al. The effects of stress on surgical performance. Am J Surg. 2006;191(1):5−10.

2. Crofts JF, Fox R, Ellis D, Winter C, Hinshaw K, Draycott TJ. Observations from 450 shoulder dystocia simulations. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):906−912.

3. Draycott TJ, Crofts JF, Ash JP, et al. Improving neonatal outcome through practical shoulder dystocia training. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):14−20.

4. Grobman WA, Miller D, Burke C, Hornbogen A, Tam K, Costello R. Outcomes associated with introduction of a shoulder dystocia protocol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(6):513−517.

Manipulation of the posterior axilla |

|

The right and left third fingers are locked into the posterior axilla, one finger from the front and one from the back of the fetus. Gentle downward guidance is provided by the fingers to draw the posterior shoulder down and out along the curve of the sacrum, thus releasing the anterior shoulder.4 In this drawing, an assistant gently holds the head up. |

Menticoglou maneuverMenticoglou noted that delivery of the posterior arm generally resolves almost all cases of shoulder dystocia. However, if the posterior arm is extended and trapped between the fetus and maternal pelvic side-wall, it may be difficult to deliver the posterior arm. In these cases he recommended having an assistant gently hold, not pull, the fetal head upward and, at the same time, having the obstetrician get on one knee, placing the middle fingers of both hands into the posterior axilla of the fetus.4

The right middle finger is placed into the axilla from the left side of the maternal pelvis, and the left middle finger is placed into the axilla from the right side of the maternal pelvis, resulting in the two middle fingers overlapping in the fetal axilla (FIGURE).4 Gentle force is then used to pull the posterior shoulder and arm downward and outward along the curve of the sacrum. Once the shoulder has emerged from the pelvis, the posterior arm is delivered. Alternatively, if the posterior shoulder is brought well down into the pelvis, another attempt can be made at delivering the posterior arm.4

My preferred approach. The Menticoglou maneuver is my preferred posterior axilla maneuver because it can be accomplished rapidly; requires no equipment, such as a sling catheter; and the obstetrician has good tactile feedback throughout the application of gentle force.

Hofmeyr-Cluver maneuverIn cases of difficult shoulder dystocia, Dr. William Smellie (1762)8 recommended placing one or two fingers in the anterior or posterior fetal axilla and gentling pulling on the axilla to deliver the body. If the axillae were too high to reach, he recommended using a blunt hook in the axilla to draw forth the impacted child. He advised caution when using a blunt hook because the fetus might be injured or lacerated.

Instead of using a hook, Hofmeyr and Cluver5−7 have recommended using a catheter sling to deliver the posterior shoulder. In this maneuver, a loop of a suction catheter or firm urinary catheter is placed over the obstetrician’s index finger and the loop is pushed through the posterior axilla, back to front, with guidance from the index finger. The index finger of the opposite hand is used to catch the loop and pull the catheter through, creating a single-stranded sling that is positioned in the axilla. Gentle force is then applied to the sling in the axis of the pelvis to deliver the posterior shoulder.

“If the posterior arm does not follow it is then swept out easily because room has been created by delivering the posterior shoulder. If the aforementioned procedure fails, the sling can be used to rotate the shoulder. To perform a rotational maneuver, sling traction is directed laterally towards the side of the baby’s back then anteriorly while digital pressure is applied behind the anterior shoulder to assist rotation.”7

Use ACOG’s checklist for documenting a shoulder dystocia

Following the resolution of a shoulder dystocia, it is important to gather all the necessary facts to complete a detailed medical record entry describing the situation and interventions used. The checklist from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) helps you to prepare a standardized medical record entry that is comprehensive.

My experience is that “free form” medical record entries describing the events at a shoulder dystocia event are generally not optimally organized, creating future problems when the case is reviewed.

ACOG obstetric checklists are available for download at http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications, or use your web browser to search for “ACOG Shoulder Dystocia checklist.”

With scant literature, know the benefits and risksThe world’s literature on posterior axilla maneuvers to resolve shoulder dystocia consists of case series and individual case reports.2−7 Hence, the quality of the data supporting this intervention is not optimal, and risks associated with the maneuver are not well characterized. Application of a controlled and gentle force to the posterior axilla may cause fracture of the fetal humerus5 or dislocation of the fetal shoulder. The posterior axilla maneuver also may increase the risk of a maternal third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration.

As a general rule, as the number of maneuvers used to resolve a difficult shoulder dystocia increase, the risk of neonatal injury increases.9 Since the posterior axilla maneuver typically is only attempted after multiple previous maneuvers have failed, the risk of fetal injury is increased. However, as time passes and a shoulder dystocia remains unresolved for 4 or 5 minutes, the risk of neurologic injury and fetal death increases.10

In resolving a shoulder dystocia, speed and skill are essential. A posterior axilla maneuver can be performed more rapidly than a Zavanelli maneuver or a symphysiotomy. Although manipulation of the posterior axilla and arm may cause a fracture of the humerus, this complication is a modest price to pay for preventing permanent fetal brain injury or fetal death.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Shoulder dystocia is an unpredictable obstetric emergency that challenges all obstetricians and midwives. In response to a shoulder dystocia emergency, most clinicians implement a sequence of well-practiced steps that begin with early recognition of the problem, clear communication of the emergency with delivery room staff, and a call for help to available clinicians. Management steps may include:

- instructing the mother to stop pushing and moving the mother's buttocks to the edge of the bed

- ensuring there is not a tight nuchal cord

- committing to avoiding the use of excessive force on the fetal head and neck

- considering performing an episiotomy

- performing the McRoberts maneuver combined with suprapubic pressure

- using a rotational maneuver, such as the Woods maneuver or the Rubin maneuver

- delivering the posterior arm

- considering the Gaskin all-four maneuver.

When initial management steps are not enoughIf this sequence of steps does not result in successful vaginal delivery, additional options include: clavicle fracture, cephalic replacement followed by cesarean delivery (Zavanelli maneuver), symphysiotomy, or fundal pressure combined with a rotational maneuver. Another simple intervention that is not discussed widely in medical textbooks or taught during training is the posterior axilla maneuver.

Posterior axilla maneuversVarying posterior axilla maneuvers have been described by many expert obstetricians, including Willughby (17th Century),1 Holman (1963),2 Schramm (1983),3 Menticoglou (2006),4 and Hofmeyr and Cluver (2009, 2015).5−7

Willughby maneuverPercival Willughby’s (1596−1685) description of a posterior axilla maneuver was brief1:

After the head is born, if the child through the greatness of the shoulders, should stick at the neck, let the midwife put her fingers under the child's armpit and give it a nudge, thrusting it to the other side with her finger, drawing the child or she may quickly bring forth the shoulders, without offering to put it forth by her hands clasped about the neck, which might endanger the breaking of the neck.

Holman maneuverHolman described a maneuver with the following steps2:

- perform an episiotomy

- place a finger in the posterior axilla and draw the posterior shoulder down along the pelvic axis

- simultaneously have an assistant perform suprapubic pressure and

- if necessary, insert two supinated fingers under the pubic arch and press and rock the anterior shoulder, tilting the anterior shoulder toward the hollow of the sacrum while simultaneously gently pulling the posterior axilla along the pelvic axis.

Schramm maneuverSchramm, working with a population enriched with women with diabetes, frequently encountered shoulder dystocia and recommended3:

If the posterior axilla can be reached—in other words, if the posterior shoulder is engaged—in my experience it can always be delivered by rotating it to the anterior position while at the same time applying traction....I normally place 1 or 2 fingers of my right hand in the posterior axilla and “scruff” the neck with my left hand, applying both rotation and traction. Because this grip is somewhat insecure, the resultant tractive force is limited and I consider this manoeuvre to be the most effective and least traumatic method of relieving moderate to severe obstruction.

Practice your shoulder dystocia maneuvers using simulation

Obstetric emergencies trigger a rush of adrenaline and great stress for the obstetrician and delivery room team. This may adversely impact motor performance, decision making, and communication skills.1 Low- and high-fidelity simulation exercises create an environment in which the obstetrics team can practice the sequence of maneuvers and seamless teamwork needed to successfully resolve a shoulder dystocia.2,3 Implementing a shoulder dystocia protocol and practicing the protocol using team-based simulation may help to reduce the adverse outcomes of shoulder dystocia.3,4

Reference

1. Wetzel CM, Kneebone RL, Woloshynowych M, et al. The effects of stress on surgical performance. Am J Surg. 2006;191(1):5−10.

2. Crofts JF, Fox R, Ellis D, Winter C, Hinshaw K, Draycott TJ. Observations from 450 shoulder dystocia simulations. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):906−912.

3. Draycott TJ, Crofts JF, Ash JP, et al. Improving neonatal outcome through practical shoulder dystocia training. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):14−20.

4. Grobman WA, Miller D, Burke C, Hornbogen A, Tam K, Costello R. Outcomes associated with introduction of a shoulder dystocia protocol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(6):513−517.

Manipulation of the posterior axilla |

|

The right and left third fingers are locked into the posterior axilla, one finger from the front and one from the back of the fetus. Gentle downward guidance is provided by the fingers to draw the posterior shoulder down and out along the curve of the sacrum, thus releasing the anterior shoulder.4 In this drawing, an assistant gently holds the head up. |

Menticoglou maneuverMenticoglou noted that delivery of the posterior arm generally resolves almost all cases of shoulder dystocia. However, if the posterior arm is extended and trapped between the fetus and maternal pelvic side-wall, it may be difficult to deliver the posterior arm. In these cases he recommended having an assistant gently hold, not pull, the fetal head upward and, at the same time, having the obstetrician get on one knee, placing the middle fingers of both hands into the posterior axilla of the fetus.4

The right middle finger is placed into the axilla from the left side of the maternal pelvis, and the left middle finger is placed into the axilla from the right side of the maternal pelvis, resulting in the two middle fingers overlapping in the fetal axilla (FIGURE).4 Gentle force is then used to pull the posterior shoulder and arm downward and outward along the curve of the sacrum. Once the shoulder has emerged from the pelvis, the posterior arm is delivered. Alternatively, if the posterior shoulder is brought well down into the pelvis, another attempt can be made at delivering the posterior arm.4

My preferred approach. The Menticoglou maneuver is my preferred posterior axilla maneuver because it can be accomplished rapidly; requires no equipment, such as a sling catheter; and the obstetrician has good tactile feedback throughout the application of gentle force.

Hofmeyr-Cluver maneuverIn cases of difficult shoulder dystocia, Dr. William Smellie (1762)8 recommended placing one or two fingers in the anterior or posterior fetal axilla and gentling pulling on the axilla to deliver the body. If the axillae were too high to reach, he recommended using a blunt hook in the axilla to draw forth the impacted child. He advised caution when using a blunt hook because the fetus might be injured or lacerated.

Instead of using a hook, Hofmeyr and Cluver5−7 have recommended using a catheter sling to deliver the posterior shoulder. In this maneuver, a loop of a suction catheter or firm urinary catheter is placed over the obstetrician’s index finger and the loop is pushed through the posterior axilla, back to front, with guidance from the index finger. The index finger of the opposite hand is used to catch the loop and pull the catheter through, creating a single-stranded sling that is positioned in the axilla. Gentle force is then applied to the sling in the axis of the pelvis to deliver the posterior shoulder.

“If the posterior arm does not follow it is then swept out easily because room has been created by delivering the posterior shoulder. If the aforementioned procedure fails, the sling can be used to rotate the shoulder. To perform a rotational maneuver, sling traction is directed laterally towards the side of the baby’s back then anteriorly while digital pressure is applied behind the anterior shoulder to assist rotation.”7

Use ACOG’s checklist for documenting a shoulder dystocia

Following the resolution of a shoulder dystocia, it is important to gather all the necessary facts to complete a detailed medical record entry describing the situation and interventions used. The checklist from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) helps you to prepare a standardized medical record entry that is comprehensive.

My experience is that “free form” medical record entries describing the events at a shoulder dystocia event are generally not optimally organized, creating future problems when the case is reviewed.

ACOG obstetric checklists are available for download at http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications, or use your web browser to search for “ACOG Shoulder Dystocia checklist.”

With scant literature, know the benefits and risksThe world’s literature on posterior axilla maneuvers to resolve shoulder dystocia consists of case series and individual case reports.2−7 Hence, the quality of the data supporting this intervention is not optimal, and risks associated with the maneuver are not well characterized. Application of a controlled and gentle force to the posterior axilla may cause fracture of the fetal humerus5 or dislocation of the fetal shoulder. The posterior axilla maneuver also may increase the risk of a maternal third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration.

As a general rule, as the number of maneuvers used to resolve a difficult shoulder dystocia increase, the risk of neonatal injury increases.9 Since the posterior axilla maneuver typically is only attempted after multiple previous maneuvers have failed, the risk of fetal injury is increased. However, as time passes and a shoulder dystocia remains unresolved for 4 or 5 minutes, the risk of neurologic injury and fetal death increases.10

In resolving a shoulder dystocia, speed and skill are essential. A posterior axilla maneuver can be performed more rapidly than a Zavanelli maneuver or a symphysiotomy. Although manipulation of the posterior axilla and arm may cause a fracture of the humerus, this complication is a modest price to pay for preventing permanent fetal brain injury or fetal death.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Willughby P. Observations in midwifery. New York, NY: MW Books; 1972:312−313.

- Holman MS. A new manoeuvre for delivery of an impacted shoulder based on a mechanical analysis. S Afr Med J. 1963;37:247−249.

- Schramm M. Impacted shoulders—a personal experience. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;23(1):28−31.

- Menticoglou SM. A modified technique to deliver the posterior arm in severe shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 pt 2):755−757.

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction: a technique for intractable shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):486–488.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Cluver CA. Posterior axilla sling traction for intractable shoulder dystocia. BJOG. 2009;116(13):1818−1820.

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction for shoulder dystocia: case review and a new method for shoulder rotation with the sling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):784.e1−e7.

- Smellie W. A treatise on the theory and practice of midwifery. 4th ed. London, England; 1762:226−227.

- Hoffman MK, Bailit JL, Branch DW, et al; Consortium on Safe Labor. A comparison of obstetric maneuvers for the acute management of shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1272−1278.

- Lerner H, Durlacher K, Smith S, Hamilton E. Relationship between head-to-body delivery interval in shoulder dystocia and neonatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):318−322.

- Willughby P. Observations in midwifery. New York, NY: MW Books; 1972:312−313.

- Holman MS. A new manoeuvre for delivery of an impacted shoulder based on a mechanical analysis. S Afr Med J. 1963;37:247−249.

- Schramm M. Impacted shoulders—a personal experience. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;23(1):28−31.

- Menticoglou SM. A modified technique to deliver the posterior arm in severe shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(3 pt 2):755−757.

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction: a technique for intractable shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):486–488.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Cluver CA. Posterior axilla sling traction for intractable shoulder dystocia. BJOG. 2009;116(13):1818−1820.

- Cluver CA, Hofmeyr GJ. Posterior axilla sling traction for shoulder dystocia: case review and a new method for shoulder rotation with the sling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(6):784.e1−e7.

- Smellie W. A treatise on the theory and practice of midwifery. 4th ed. London, England; 1762:226−227.

- Hoffman MK, Bailit JL, Branch DW, et al; Consortium on Safe Labor. A comparison of obstetric maneuvers for the acute management of shoulder dystocia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1272−1278.

- Lerner H, Durlacher K, Smith S, Hamilton E. Relationship between head-to-body delivery interval in shoulder dystocia and neonatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):318−322.

In this article

- Menticoglou maneuver

- Importance of simulation

Reader reactions to the problem of inadequate contraception for high-risk women

“Contraception as a vital sign”

In his recent Editorial Dr. Barbieri asked for ideas to improve contraception counseling for women with medical problems that put them at risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. His idea of “contraception status as a vital sign” is applied in our very large group practice in Northern California using the electronic health record (EHR).

Over 10 years ago, I attempted to put a hard stop in the EHR to require documentation that women of reproductive age be evaluated for contraception. This scheme seemed to be too cumbersome and was rejected at the time.

The idea was not abandoned, however. Medical assistants must now document a means of contraception for each woman of reproductive age. This does not guarantee that a physician will look at the information, but it is a step in the right direction.

My hope is that someday we will have automatic contraception as a vital sign documentation for all reproductive-age women, including “children” who are documented as menstruating. In the meantime, thank you for highlighting this critical issue.

Tia Will, MD

Sacramento, California

Reduce reimbursement when standard of care is not met

When I read Dr. Barbieri’s Editorial, I was surprised that he avoided the elephant in the room: the current political climate of denying contraception to women, including the defunding of Planned Parenthood and the Supreme Court decision to allow corporations to deny contraceptive coverage for religious issues.

Although I am not currently involved in women’s health, I do work under the auspices of a large Catholic health care system in the United States. Here, all employees are prohibited from providing contraceptive procedures, prescriptions, or even counseling unless it is a Natural Family Planning/ Fertility Awareness Method. These employees also are not provided individual contraceptive health coverage by their employer; this coverage is provided by the federal government thanks to the Affordable Care Act.

Contraception is part of the standard of care for women. However, many women are denied this standard of care due to “religious” reasons, which I suspect may be partially financial and/or political in nature.

This issue must therefore be addressed by political and financial means. My recommendation is for legislation that mandates lower reimbursement rates for health care systems and providers that refuse to offer full contraceptive options to women. If they do not provide full care, they do not get full payment for services. The money saved by reduced reimbursements could then fund federal women’s health clinics in areas dominated by “religious” health care systems that would guarantee full reproductive health options to all.

Name and practice location withheld

Remove Medicaid barriers to postpartum sterilization

An issue not addressed in Dr. Barbieri’s Editorial is that of women who, after appropriate and extensive counseling by a physician and with a full understanding of the reproductive implications and the possible adverse effect of additional pregnancies on their health and life, decide for permanent contraception. A woman’s opportunity to obtain postpartum or interval contraceptive procedure varies by her insurance coverage, which is indirectly associated with her ethnicity or race.

In 1979, Medicaid Title XIX imposed a 30-day interval between the signing of the sterilization informed consent by the patient and the performance of the procedure. These regulations are still in effect today. What was instituted to protect vulnerable populations from coerced methods in the 1970s represents an anachronistic and archaic approach in the 21st Century. This regulation discriminates against low-income and minority women whose health care is covered by public insurance yet who are frequently at highest risk for unintended and possible risky pregnancy or abortion. In simple words, this imposition violates the standards of justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence as it treats publicly insured women differently from privately insured women.

The American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists1 state that this regulation must be revised and charged practitioners to develop policies and procedures to ensure all women who desire postpartum sterilization can receive it. It is incumbent upon all women’s health care physicians to see that this barrier is removed.

Federico G. Mariona, MD, MHSA

Dearborn, Michigan

Reference

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 530: access to postpartum sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):212–215.

Educate the sexual partners of at-risk women

It always strikes me how little emphasis is placed on including the sexual partners of women with serious medical problems in the dialogue about responsibility for at-risk pregnancy. As advocates for women’s health, we should educate the couple about vasectomy and liberally provide referrals. Community outreach to help men understand how they can protect their partner from potentially dangerous unwanted pregnancy is extremely important and not stressed enough. Vasectomy is a quick, safe procedure performed in a physician’s office under local anesthesia. Why should any woman who has already risked her life carrying and delivering a baby be required to bear the contraceptive burden when there is a safe and convenient alternative?

Emily Gubert, MD

East Islip, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Will, Mariona, and Gubert and the anonymous author for their wonderful recommendations on approaches to help improve contraceptive care for women. I agree with Dr. Will that the EHR is a valuable tool to advance contraceptive care. The anonymous author and Dr. Mariona make the critically important point that all women should have access to desired contraception without any barriers based on institutional beliefs or government regulations. The patient’s needs should be prioritized in all medical decision making. I agree with Dr. Gubert that including the male partner in the care process is an important part of effective contraception for women. I enthusiastically agree with her that the best permanent contraceptive for a stable couple is vasectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“Contraception as a vital sign”

In his recent Editorial Dr. Barbieri asked for ideas to improve contraception counseling for women with medical problems that put them at risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. His idea of “contraception status as a vital sign” is applied in our very large group practice in Northern California using the electronic health record (EHR).

Over 10 years ago, I attempted to put a hard stop in the EHR to require documentation that women of reproductive age be evaluated for contraception. This scheme seemed to be too cumbersome and was rejected at the time.

The idea was not abandoned, however. Medical assistants must now document a means of contraception for each woman of reproductive age. This does not guarantee that a physician will look at the information, but it is a step in the right direction.

My hope is that someday we will have automatic contraception as a vital sign documentation for all reproductive-age women, including “children” who are documented as menstruating. In the meantime, thank you for highlighting this critical issue.

Tia Will, MD

Sacramento, California

Reduce reimbursement when standard of care is not met

When I read Dr. Barbieri’s Editorial, I was surprised that he avoided the elephant in the room: the current political climate of denying contraception to women, including the defunding of Planned Parenthood and the Supreme Court decision to allow corporations to deny contraceptive coverage for religious issues.

Although I am not currently involved in women’s health, I do work under the auspices of a large Catholic health care system in the United States. Here, all employees are prohibited from providing contraceptive procedures, prescriptions, or even counseling unless it is a Natural Family Planning/ Fertility Awareness Method. These employees also are not provided individual contraceptive health coverage by their employer; this coverage is provided by the federal government thanks to the Affordable Care Act.

Contraception is part of the standard of care for women. However, many women are denied this standard of care due to “religious” reasons, which I suspect may be partially financial and/or political in nature.

This issue must therefore be addressed by political and financial means. My recommendation is for legislation that mandates lower reimbursement rates for health care systems and providers that refuse to offer full contraceptive options to women. If they do not provide full care, they do not get full payment for services. The money saved by reduced reimbursements could then fund federal women’s health clinics in areas dominated by “religious” health care systems that would guarantee full reproductive health options to all.

Name and practice location withheld

Remove Medicaid barriers to postpartum sterilization

An issue not addressed in Dr. Barbieri’s Editorial is that of women who, after appropriate and extensive counseling by a physician and with a full understanding of the reproductive implications and the possible adverse effect of additional pregnancies on their health and life, decide for permanent contraception. A woman’s opportunity to obtain postpartum or interval contraceptive procedure varies by her insurance coverage, which is indirectly associated with her ethnicity or race.

In 1979, Medicaid Title XIX imposed a 30-day interval between the signing of the sterilization informed consent by the patient and the performance of the procedure. These regulations are still in effect today. What was instituted to protect vulnerable populations from coerced methods in the 1970s represents an anachronistic and archaic approach in the 21st Century. This regulation discriminates against low-income and minority women whose health care is covered by public insurance yet who are frequently at highest risk for unintended and possible risky pregnancy or abortion. In simple words, this imposition violates the standards of justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence as it treats publicly insured women differently from privately insured women.

The American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists1 state that this regulation must be revised and charged practitioners to develop policies and procedures to ensure all women who desire postpartum sterilization can receive it. It is incumbent upon all women’s health care physicians to see that this barrier is removed.

Federico G. Mariona, MD, MHSA

Dearborn, Michigan

Reference

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 530: access to postpartum sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):212–215.

Educate the sexual partners of at-risk women

It always strikes me how little emphasis is placed on including the sexual partners of women with serious medical problems in the dialogue about responsibility for at-risk pregnancy. As advocates for women’s health, we should educate the couple about vasectomy and liberally provide referrals. Community outreach to help men understand how they can protect their partner from potentially dangerous unwanted pregnancy is extremely important and not stressed enough. Vasectomy is a quick, safe procedure performed in a physician’s office under local anesthesia. Why should any woman who has already risked her life carrying and delivering a baby be required to bear the contraceptive burden when there is a safe and convenient alternative?

Emily Gubert, MD

East Islip, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Will, Mariona, and Gubert and the anonymous author for their wonderful recommendations on approaches to help improve contraceptive care for women. I agree with Dr. Will that the EHR is a valuable tool to advance contraceptive care. The anonymous author and Dr. Mariona make the critically important point that all women should have access to desired contraception without any barriers based on institutional beliefs or government regulations. The patient’s needs should be prioritized in all medical decision making. I agree with Dr. Gubert that including the male partner in the care process is an important part of effective contraception for women. I enthusiastically agree with her that the best permanent contraceptive for a stable couple is vasectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“Contraception as a vital sign”

In his recent Editorial Dr. Barbieri asked for ideas to improve contraception counseling for women with medical problems that put them at risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. His idea of “contraception status as a vital sign” is applied in our very large group practice in Northern California using the electronic health record (EHR).

Over 10 years ago, I attempted to put a hard stop in the EHR to require documentation that women of reproductive age be evaluated for contraception. This scheme seemed to be too cumbersome and was rejected at the time.

The idea was not abandoned, however. Medical assistants must now document a means of contraception for each woman of reproductive age. This does not guarantee that a physician will look at the information, but it is a step in the right direction.

My hope is that someday we will have automatic contraception as a vital sign documentation for all reproductive-age women, including “children” who are documented as menstruating. In the meantime, thank you for highlighting this critical issue.

Tia Will, MD

Sacramento, California

Reduce reimbursement when standard of care is not met

When I read Dr. Barbieri’s Editorial, I was surprised that he avoided the elephant in the room: the current political climate of denying contraception to women, including the defunding of Planned Parenthood and the Supreme Court decision to allow corporations to deny contraceptive coverage for religious issues.

Although I am not currently involved in women’s health, I do work under the auspices of a large Catholic health care system in the United States. Here, all employees are prohibited from providing contraceptive procedures, prescriptions, or even counseling unless it is a Natural Family Planning/ Fertility Awareness Method. These employees also are not provided individual contraceptive health coverage by their employer; this coverage is provided by the federal government thanks to the Affordable Care Act.

Contraception is part of the standard of care for women. However, many women are denied this standard of care due to “religious” reasons, which I suspect may be partially financial and/or political in nature.

This issue must therefore be addressed by political and financial means. My recommendation is for legislation that mandates lower reimbursement rates for health care systems and providers that refuse to offer full contraceptive options to women. If they do not provide full care, they do not get full payment for services. The money saved by reduced reimbursements could then fund federal women’s health clinics in areas dominated by “religious” health care systems that would guarantee full reproductive health options to all.

Name and practice location withheld

Remove Medicaid barriers to postpartum sterilization

An issue not addressed in Dr. Barbieri’s Editorial is that of women who, after appropriate and extensive counseling by a physician and with a full understanding of the reproductive implications and the possible adverse effect of additional pregnancies on their health and life, decide for permanent contraception. A woman’s opportunity to obtain postpartum or interval contraceptive procedure varies by her insurance coverage, which is indirectly associated with her ethnicity or race.

In 1979, Medicaid Title XIX imposed a 30-day interval between the signing of the sterilization informed consent by the patient and the performance of the procedure. These regulations are still in effect today. What was instituted to protect vulnerable populations from coerced methods in the 1970s represents an anachronistic and archaic approach in the 21st Century. This regulation discriminates against low-income and minority women whose health care is covered by public insurance yet who are frequently at highest risk for unintended and possible risky pregnancy or abortion. In simple words, this imposition violates the standards of justice, beneficence, and nonmaleficence as it treats publicly insured women differently from privately insured women.

The American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists1 state that this regulation must be revised and charged practitioners to develop policies and procedures to ensure all women who desire postpartum sterilization can receive it. It is incumbent upon all women’s health care physicians to see that this barrier is removed.

Federico G. Mariona, MD, MHSA

Dearborn, Michigan

Reference

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 530: access to postpartum sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):212–215.

Educate the sexual partners of at-risk women

It always strikes me how little emphasis is placed on including the sexual partners of women with serious medical problems in the dialogue about responsibility for at-risk pregnancy. As advocates for women’s health, we should educate the couple about vasectomy and liberally provide referrals. Community outreach to help men understand how they can protect their partner from potentially dangerous unwanted pregnancy is extremely important and not stressed enough. Vasectomy is a quick, safe procedure performed in a physician’s office under local anesthesia. Why should any woman who has already risked her life carrying and delivering a baby be required to bear the contraceptive burden when there is a safe and convenient alternative?

Emily Gubert, MD

East Islip, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Drs. Will, Mariona, and Gubert and the anonymous author for their wonderful recommendations on approaches to help improve contraceptive care for women. I agree with Dr. Will that the EHR is a valuable tool to advance contraceptive care. The anonymous author and Dr. Mariona make the critically important point that all women should have access to desired contraception without any barriers based on institutional beliefs or government regulations. The patient’s needs should be prioritized in all medical decision making. I agree with Dr. Gubert that including the male partner in the care process is an important part of effective contraception for women. I enthusiastically agree with her that the best permanent contraceptive for a stable couple is vasectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Do antidepressants really cause autism?

Presently it seems that anything a pregnant woman ingests can be correlated with a teratology or an unfortunate neurobehavioral outcome. In an era when up to 15% of pregnant women are taking antidepressant therapy, antidepressants are obvious drugs to be correlated with an untoward fetal outcome, despite the fact that untreated maternal depression itself is significantly worse.1

A recent retrospective secondary end point study by Boukhris and colleagues on antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children is an example of correlation without substantive evidence of causation. Although this study received media attention,2 it is a “data-dredge” study. While the authors correctly note that the database is derived from a prospective registry-based population-based cohort study (the Quebec Pregnancy/Children Cohort), their study’s design more closely resembles a post hoc nested case-control study.

Details of the study

Researchers evaluated data from 145,456 singleton full-term infants born alive between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2009, with antidepressant exposure during pregnancy defined according to trimester and specific antidepressant classes. Children were considered as having autism if they had received at least 1 autism diagnosis between their date of birth and the last date of follow-up.

We perceive several problems in the study’s design and the authors’ conclusions.

Shortcomings of study design

The study results are based on a post hoc analysis. Autism spectrum disorder was not the primary end point of interest in this database. Accordingly, in a secondary end point study, the risk for bias and confounding is substantial. This study design cannot prove causation.3–5

Exposure is defined by number of antidepressant prescriptions filled. No data regarding adherence (true exposure) are provided. Many women will not take antidepressant drugs as prescribed during pregnancy. It has been reported that antidepressants dispensed to pregnant women during the last 2 trimesters of pregnancy were taken by only 55% of the women.6

The specific antidepressant agents and dosages used were not identified, and the study provided no good sense of duration of use. Is it biologically plausible, therefore, to suggest that all antidepressants—with their disparate structures and mechanisms, in all doses, and for various durations of use—have a uniform effect on fetal neurodevelopment?

Notably, in another prescription drug study of 668,468 pregnancies in 2013, investigators found no significant association between prenatal exposure to antidepressants and ASD.7

Some data suggest that ASD and depression may share preexisting risk factors.8 The increased risk for ASD proposed by Boukhris and colleagues’ study cannot likely be separated from the well-described genetic risk of ASD that might be shared with that of depression.9,10

The stated hazard ratios (HRs) are all <2.2. Given this study’s design, it is plausible that various biases and confounders account for these findings. True significance of these HRs are suspect unless they exceed 3.0, and there is a greater probability of avoiding a type I error when the risk ratios are greater than 4 to 5.3,4

What this evidence means for practice

In this registry-based study of an ongoing population-based cohort, the authors suggest a sensational 87% increased risk of ASD with use of antidepressants during pregnancy. While technically correct, the absolute risk (if real) is really less than 1%. Using sound epidemiologic principles, we would advise against speculating on a number needed to harm based on this study design. Such a projection would require a prospective randomized trial.

—Robert P. Kauffman, MD; Teresa Baker, MD; and Thomas W. Hale, PhD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dawson AL, Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, et al. Antidepressant prescription claims among reproductive-aged women with private employer-sponsored insurance--United States 2008 -2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):41–46.

- Cha AE. Maternal exposure to anti-depressant SSRIs linked to autism in children. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2015/12/14/maternal-exposure-to-anti-depressant-ssris-linked-to-autism-in-children/. Published December 17, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2017.

- Taubes G. Epidemiology faces its limits. Science. 1995;269(5221):164–169.

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. False alarms and pseudo-epidemics: the limitations of observational epidemiology. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):920–927.

- Smith GD, Ebrahim S. Data dredging, bias, and confounding: they can all get you into the BMJ and the Friday papers. BMJ. 2002;325(7378):1437–1438.

- Källén B, Nilsson E, Olausson PO. Antidepressant use during pregnancy: comparison of data obtained from a prescription register and from antenatal care records. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(8):839–845.

- Sørensen MJ, Grønborg TK, Christensen J, et al. Antidepressant exposure in pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:449–459.

- King BH. Assessing risk of autism spectrum disorder in children after antidepressant use during pregnancy. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(2):111–112.

- Daniels JL, Forssen U, Hultman CM, et al. Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1357–e1362.

- Lugnegård T, Hallerbäck MU, Gillberg C. Psychiatric comorbidity in young adults with a clinical diagnosis of Asperger syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32(5):1910–1917.

Presently it seems that anything a pregnant woman ingests can be correlated with a teratology or an unfortunate neurobehavioral outcome. In an era when up to 15% of pregnant women are taking antidepressant therapy, antidepressants are obvious drugs to be correlated with an untoward fetal outcome, despite the fact that untreated maternal depression itself is significantly worse.1

A recent retrospective secondary end point study by Boukhris and colleagues on antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children is an example of correlation without substantive evidence of causation. Although this study received media attention,2 it is a “data-dredge” study. While the authors correctly note that the database is derived from a prospective registry-based population-based cohort study (the Quebec Pregnancy/Children Cohort), their study’s design more closely resembles a post hoc nested case-control study.

Details of the study

Researchers evaluated data from 145,456 singleton full-term infants born alive between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2009, with antidepressant exposure during pregnancy defined according to trimester and specific antidepressant classes. Children were considered as having autism if they had received at least 1 autism diagnosis between their date of birth and the last date of follow-up.

We perceive several problems in the study’s design and the authors’ conclusions.

Shortcomings of study design

The study results are based on a post hoc analysis. Autism spectrum disorder was not the primary end point of interest in this database. Accordingly, in a secondary end point study, the risk for bias and confounding is substantial. This study design cannot prove causation.3–5

Exposure is defined by number of antidepressant prescriptions filled. No data regarding adherence (true exposure) are provided. Many women will not take antidepressant drugs as prescribed during pregnancy. It has been reported that antidepressants dispensed to pregnant women during the last 2 trimesters of pregnancy were taken by only 55% of the women.6

The specific antidepressant agents and dosages used were not identified, and the study provided no good sense of duration of use. Is it biologically plausible, therefore, to suggest that all antidepressants—with their disparate structures and mechanisms, in all doses, and for various durations of use—have a uniform effect on fetal neurodevelopment?

Notably, in another prescription drug study of 668,468 pregnancies in 2013, investigators found no significant association between prenatal exposure to antidepressants and ASD.7

Some data suggest that ASD and depression may share preexisting risk factors.8 The increased risk for ASD proposed by Boukhris and colleagues’ study cannot likely be separated from the well-described genetic risk of ASD that might be shared with that of depression.9,10

The stated hazard ratios (HRs) are all <2.2. Given this study’s design, it is plausible that various biases and confounders account for these findings. True significance of these HRs are suspect unless they exceed 3.0, and there is a greater probability of avoiding a type I error when the risk ratios are greater than 4 to 5.3,4

What this evidence means for practice

In this registry-based study of an ongoing population-based cohort, the authors suggest a sensational 87% increased risk of ASD with use of antidepressants during pregnancy. While technically correct, the absolute risk (if real) is really less than 1%. Using sound epidemiologic principles, we would advise against speculating on a number needed to harm based on this study design. Such a projection would require a prospective randomized trial.

—Robert P. Kauffman, MD; Teresa Baker, MD; and Thomas W. Hale, PhD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Presently it seems that anything a pregnant woman ingests can be correlated with a teratology or an unfortunate neurobehavioral outcome. In an era when up to 15% of pregnant women are taking antidepressant therapy, antidepressants are obvious drugs to be correlated with an untoward fetal outcome, despite the fact that untreated maternal depression itself is significantly worse.1

A recent retrospective secondary end point study by Boukhris and colleagues on antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children is an example of correlation without substantive evidence of causation. Although this study received media attention,2 it is a “data-dredge” study. While the authors correctly note that the database is derived from a prospective registry-based population-based cohort study (the Quebec Pregnancy/Children Cohort), their study’s design more closely resembles a post hoc nested case-control study.

Details of the study

Researchers evaluated data from 145,456 singleton full-term infants born alive between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2009, with antidepressant exposure during pregnancy defined according to trimester and specific antidepressant classes. Children were considered as having autism if they had received at least 1 autism diagnosis between their date of birth and the last date of follow-up.

We perceive several problems in the study’s design and the authors’ conclusions.

Shortcomings of study design

The study results are based on a post hoc analysis. Autism spectrum disorder was not the primary end point of interest in this database. Accordingly, in a secondary end point study, the risk for bias and confounding is substantial. This study design cannot prove causation.3–5

Exposure is defined by number of antidepressant prescriptions filled. No data regarding adherence (true exposure) are provided. Many women will not take antidepressant drugs as prescribed during pregnancy. It has been reported that antidepressants dispensed to pregnant women during the last 2 trimesters of pregnancy were taken by only 55% of the women.6

The specific antidepressant agents and dosages used were not identified, and the study provided no good sense of duration of use. Is it biologically plausible, therefore, to suggest that all antidepressants—with their disparate structures and mechanisms, in all doses, and for various durations of use—have a uniform effect on fetal neurodevelopment?

Notably, in another prescription drug study of 668,468 pregnancies in 2013, investigators found no significant association between prenatal exposure to antidepressants and ASD.7

Some data suggest that ASD and depression may share preexisting risk factors.8 The increased risk for ASD proposed by Boukhris and colleagues’ study cannot likely be separated from the well-described genetic risk of ASD that might be shared with that of depression.9,10

The stated hazard ratios (HRs) are all <2.2. Given this study’s design, it is plausible that various biases and confounders account for these findings. True significance of these HRs are suspect unless they exceed 3.0, and there is a greater probability of avoiding a type I error when the risk ratios are greater than 4 to 5.3,4

What this evidence means for practice

In this registry-based study of an ongoing population-based cohort, the authors suggest a sensational 87% increased risk of ASD with use of antidepressants during pregnancy. While technically correct, the absolute risk (if real) is really less than 1%. Using sound epidemiologic principles, we would advise against speculating on a number needed to harm based on this study design. Such a projection would require a prospective randomized trial.

—Robert P. Kauffman, MD; Teresa Baker, MD; and Thomas W. Hale, PhD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dawson AL, Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, et al. Antidepressant prescription claims among reproductive-aged women with private employer-sponsored insurance--United States 2008 -2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):41–46.

- Cha AE. Maternal exposure to anti-depressant SSRIs linked to autism in children. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/to-your-health/wp/2015/12/14/maternal-exposure-to-anti-depressant-ssris-linked-to-autism-in-children/. Published December 17, 2015. Accessed March 13, 2017.

- Taubes G. Epidemiology faces its limits. Science. 1995;269(5221):164–169.