User login

FDA’s new labeling rule: clinical implications

As reviewed in a previous column, in December 2014, the Food and Drug Administration released the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR), which will go into effect on June 30, 2015. This replaces and addresses the limitations of the system that has been in place for more than 30 years, which ascribed a pregnancy risk category of A,B,C,D, or X to drugs, with the purpose of informing the clinician and patient about the reproductive safety of medications during pregnancy. Though well intentioned, criticisms of this system have been abundant.

The system certainly simplified the interaction between physicians and patients, who presumably would be reassured that the risk of a certain medicine had been quantified by a regulatory body and therefore could be used as a basis for making a decision about whether or not to take a medicine during pregnancy. While the purpose of the labeling system was to provide some overarching guidance about available reproductive safety information of a medicine, it was ultimately used by clinicians and patients either to somehow garner reassurance about a medicine, or to heighten concern about a medicine.

From the outset, the system could not take into account the accruing reproductive safety information regarding compounds across therapeutic categories, and as a result, the risk category could be inadvertently reassuring or even misleading to patients with respect to medicines they might decide to stop or to continue.

With the older labeling system, some medicines are in the same category, despite very different amounts of reproductive safety information available on the drugs. In the 1990s, there were more reproductive safety data available on certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), compared with others, but now the amount of such data available across SSRIs is fairly consistent. Yet SSRI labels have not been updated with the abundance of new reproductive safety information that has become available.

Almost 10 years ago, paroxetine (Paxil) was switched from a category C to D, when first-trimester exposure was linked to an increased risk of birth defects, particularly heart defects. But it was not switched back to category C when data became available that did not support that level of concern. Because of some of its side effects, paroxetine may not be considered by many to be a first-line treatment for major depression, but it certainly would not be absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy as might be presumed by the assignment of a category D label.

Lithium and sodium valproate provide another example of the limitations of the old system, which will be addressed in the new system. While the teratogenicity of both agents has been well described, the absolute risk of malformations with fetal exposure to lithium is approximately 0.05%- 0.1%, but the risk of neural tube defects with sodium valproate is estimated at 8%. Complicating the issue further, in 2013, the FDA announced that sodium valproate had been changed from a category D to X for migraine prevention, but retained the category D classification for other indications.

Placing lithium in category D suggests a relative contraindication and yet discontinuing that medication during pregnancy can put the mother and her baby at risk, given the data supporting the rapid onset of relapse in women who stop mood stabilizers during pregnancy.

For women maintained on lithium for recurrent or brittle bipolar disorder, the drug would certainly not be contraindicated and may afford critical emotional well-being and protection from relapse during pregnancy; the clinical scenario of discontinuation of lithium proximate to or during pregnancy and subsequent relapse of underlying illness is a serious clinical matter frequently demanding urgent intervention.

Still another example of the incomplete informative value of the older system is found in the assignment of atypical antipsychotics into different risk categories. Lurasidone (Latuda), approved in 2010, is in category B, but other atypical antipsychotics are in category C. One might assume that this implies that there are more reproductive safety data available on lurasidone supporting safety, but in fact, reproductive safety data for this molecule are extremely limited, and the absence of adverse event information resulted in a category B. This is a great example of the clinical maxim that incomplete or sparse data is just that; it does not imply safety, it implies that we do not know a lot about the safety of a medication.

If the old system of pregnancy labeling was arbitrary, the PLLR will be more descriptive. Safety information during pregnancy and lactation in the drug label will appear in a section on pregnancy, reformatted to include a risk summary, clinical considerations, and data subsections, as well as a section on lactation, and a section on females and males of reproductive potential.

Ongoing revision of the label as information becomes outdated is a requirement, and manufacturers will be obligated to include information on whether there is a pregnancy registry for the given drug. The goal of the PLLR is thus to provide the patient and clinician with information which addresses both sides of the risk-benefit decision for a given medicine – risks of fetal drug exposure and the risk of untreated illness for the woman and baby, a factor that is not addressed at all with the current system.

Certainly, the new label system will be a charge to industry to establish, support, and encourage enrollment in well-designed pregnancy registries across therapeutic areas to provide ample amounts of good quality data that can then be used by patients along with their physicians to make the most appropriate clinical decisions.

Much of the currently available reproductive safety information on drugs is derived from spontaneous reports, where there has been inconsistent information and variable levels of scrutiny with respect to outcomes assessment, and from small, underpowered cohort studies or large administrative databases. Postmarketing surveillance efforts have been rather modest and have not been a priority for manufacturers in most cases. Hopefully, this will change as pregnancy registries become part of routine postmarketing surveillance.

The new system will not be a panacea, and I expect there will be growing pains, considering the huge challenge of reducing the available data of varying quality into distinct paragraphs. It may also be difficult to synthesize the volume of data and the nuanced differences between certain studies into a paragraph on risk assessment. The task will be simpler for some agents and more challenging for others where the data are less consistent. Questions also remain as to how data will be revised over time.

But despite these challenges, the new system represents a monumental change, and in my mind, will bring a focus to the importance of the issue of quantifying reproductive safety of medications used by women either planning to get pregnant or who are pregnant or breastfeeding, across therapeutic areas. Of particular importance, the new system will hopefully lead to more discussion between physician and patient about what is and is not known about the reproductive safety of a medication, versus a cursory reference to some previously assigned category label.

Our group has shown that when it comes to making decisions about using medication during pregnancy, even when given the same information, women will make different decisions. This is critical since people make personal decisions about the use of these medications in collaboration with their doctors on a case-by-case basis, based on personal preference, available information, and clinical conditions across a spectrum of severity.

As the FDA requirements shift from the arbitrary category label assignment to a more descriptive explanation of risk, based on available data, an important question will be what mechanism will be used by regulators collaborating with industry to update labels with the growing amounts of information on reproductive safety, particularly if there is a commitment from industry to enhance postmarketing surveillance with more pregnancy registries.

Better data can catalyze thoughtful discussions between doctor and patient regarding decisions to use or defer treatment with a given medicine. One might wonder if the new system will open a Pandora’s box. But I believe in this case, opening Pandora’s box would be welcome because it will hopefully lead to a more careful examination of the available information regarding reproductive safety and more informed decisions on the part of patients.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information about reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of antidepressant medications and is the principal investigator of the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics, which receives support from the manufacturers of those drugs. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected]. Scan this QR code or go to obgynnews.com to view similar columns.

As reviewed in a previous column, in December 2014, the Food and Drug Administration released the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR), which will go into effect on June 30, 2015. This replaces and addresses the limitations of the system that has been in place for more than 30 years, which ascribed a pregnancy risk category of A,B,C,D, or X to drugs, with the purpose of informing the clinician and patient about the reproductive safety of medications during pregnancy. Though well intentioned, criticisms of this system have been abundant.

The system certainly simplified the interaction between physicians and patients, who presumably would be reassured that the risk of a certain medicine had been quantified by a regulatory body and therefore could be used as a basis for making a decision about whether or not to take a medicine during pregnancy. While the purpose of the labeling system was to provide some overarching guidance about available reproductive safety information of a medicine, it was ultimately used by clinicians and patients either to somehow garner reassurance about a medicine, or to heighten concern about a medicine.

From the outset, the system could not take into account the accruing reproductive safety information regarding compounds across therapeutic categories, and as a result, the risk category could be inadvertently reassuring or even misleading to patients with respect to medicines they might decide to stop or to continue.

With the older labeling system, some medicines are in the same category, despite very different amounts of reproductive safety information available on the drugs. In the 1990s, there were more reproductive safety data available on certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), compared with others, but now the amount of such data available across SSRIs is fairly consistent. Yet SSRI labels have not been updated with the abundance of new reproductive safety information that has become available.

Almost 10 years ago, paroxetine (Paxil) was switched from a category C to D, when first-trimester exposure was linked to an increased risk of birth defects, particularly heart defects. But it was not switched back to category C when data became available that did not support that level of concern. Because of some of its side effects, paroxetine may not be considered by many to be a first-line treatment for major depression, but it certainly would not be absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy as might be presumed by the assignment of a category D label.

Lithium and sodium valproate provide another example of the limitations of the old system, which will be addressed in the new system. While the teratogenicity of both agents has been well described, the absolute risk of malformations with fetal exposure to lithium is approximately 0.05%- 0.1%, but the risk of neural tube defects with sodium valproate is estimated at 8%. Complicating the issue further, in 2013, the FDA announced that sodium valproate had been changed from a category D to X for migraine prevention, but retained the category D classification for other indications.

Placing lithium in category D suggests a relative contraindication and yet discontinuing that medication during pregnancy can put the mother and her baby at risk, given the data supporting the rapid onset of relapse in women who stop mood stabilizers during pregnancy.

For women maintained on lithium for recurrent or brittle bipolar disorder, the drug would certainly not be contraindicated and may afford critical emotional well-being and protection from relapse during pregnancy; the clinical scenario of discontinuation of lithium proximate to or during pregnancy and subsequent relapse of underlying illness is a serious clinical matter frequently demanding urgent intervention.

Still another example of the incomplete informative value of the older system is found in the assignment of atypical antipsychotics into different risk categories. Lurasidone (Latuda), approved in 2010, is in category B, but other atypical antipsychotics are in category C. One might assume that this implies that there are more reproductive safety data available on lurasidone supporting safety, but in fact, reproductive safety data for this molecule are extremely limited, and the absence of adverse event information resulted in a category B. This is a great example of the clinical maxim that incomplete or sparse data is just that; it does not imply safety, it implies that we do not know a lot about the safety of a medication.

If the old system of pregnancy labeling was arbitrary, the PLLR will be more descriptive. Safety information during pregnancy and lactation in the drug label will appear in a section on pregnancy, reformatted to include a risk summary, clinical considerations, and data subsections, as well as a section on lactation, and a section on females and males of reproductive potential.

Ongoing revision of the label as information becomes outdated is a requirement, and manufacturers will be obligated to include information on whether there is a pregnancy registry for the given drug. The goal of the PLLR is thus to provide the patient and clinician with information which addresses both sides of the risk-benefit decision for a given medicine – risks of fetal drug exposure and the risk of untreated illness for the woman and baby, a factor that is not addressed at all with the current system.

Certainly, the new label system will be a charge to industry to establish, support, and encourage enrollment in well-designed pregnancy registries across therapeutic areas to provide ample amounts of good quality data that can then be used by patients along with their physicians to make the most appropriate clinical decisions.

Much of the currently available reproductive safety information on drugs is derived from spontaneous reports, where there has been inconsistent information and variable levels of scrutiny with respect to outcomes assessment, and from small, underpowered cohort studies or large administrative databases. Postmarketing surveillance efforts have been rather modest and have not been a priority for manufacturers in most cases. Hopefully, this will change as pregnancy registries become part of routine postmarketing surveillance.

The new system will not be a panacea, and I expect there will be growing pains, considering the huge challenge of reducing the available data of varying quality into distinct paragraphs. It may also be difficult to synthesize the volume of data and the nuanced differences between certain studies into a paragraph on risk assessment. The task will be simpler for some agents and more challenging for others where the data are less consistent. Questions also remain as to how data will be revised over time.

But despite these challenges, the new system represents a monumental change, and in my mind, will bring a focus to the importance of the issue of quantifying reproductive safety of medications used by women either planning to get pregnant or who are pregnant or breastfeeding, across therapeutic areas. Of particular importance, the new system will hopefully lead to more discussion between physician and patient about what is and is not known about the reproductive safety of a medication, versus a cursory reference to some previously assigned category label.

Our group has shown that when it comes to making decisions about using medication during pregnancy, even when given the same information, women will make different decisions. This is critical since people make personal decisions about the use of these medications in collaboration with their doctors on a case-by-case basis, based on personal preference, available information, and clinical conditions across a spectrum of severity.

As the FDA requirements shift from the arbitrary category label assignment to a more descriptive explanation of risk, based on available data, an important question will be what mechanism will be used by regulators collaborating with industry to update labels with the growing amounts of information on reproductive safety, particularly if there is a commitment from industry to enhance postmarketing surveillance with more pregnancy registries.

Better data can catalyze thoughtful discussions between doctor and patient regarding decisions to use or defer treatment with a given medicine. One might wonder if the new system will open a Pandora’s box. But I believe in this case, opening Pandora’s box would be welcome because it will hopefully lead to a more careful examination of the available information regarding reproductive safety and more informed decisions on the part of patients.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information about reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of antidepressant medications and is the principal investigator of the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics, which receives support from the manufacturers of those drugs. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected]. Scan this QR code or go to obgynnews.com to view similar columns.

As reviewed in a previous column, in December 2014, the Food and Drug Administration released the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR), which will go into effect on June 30, 2015. This replaces and addresses the limitations of the system that has been in place for more than 30 years, which ascribed a pregnancy risk category of A,B,C,D, or X to drugs, with the purpose of informing the clinician and patient about the reproductive safety of medications during pregnancy. Though well intentioned, criticisms of this system have been abundant.

The system certainly simplified the interaction between physicians and patients, who presumably would be reassured that the risk of a certain medicine had been quantified by a regulatory body and therefore could be used as a basis for making a decision about whether or not to take a medicine during pregnancy. While the purpose of the labeling system was to provide some overarching guidance about available reproductive safety information of a medicine, it was ultimately used by clinicians and patients either to somehow garner reassurance about a medicine, or to heighten concern about a medicine.

From the outset, the system could not take into account the accruing reproductive safety information regarding compounds across therapeutic categories, and as a result, the risk category could be inadvertently reassuring or even misleading to patients with respect to medicines they might decide to stop or to continue.

With the older labeling system, some medicines are in the same category, despite very different amounts of reproductive safety information available on the drugs. In the 1990s, there were more reproductive safety data available on certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), compared with others, but now the amount of such data available across SSRIs is fairly consistent. Yet SSRI labels have not been updated with the abundance of new reproductive safety information that has become available.

Almost 10 years ago, paroxetine (Paxil) was switched from a category C to D, when first-trimester exposure was linked to an increased risk of birth defects, particularly heart defects. But it was not switched back to category C when data became available that did not support that level of concern. Because of some of its side effects, paroxetine may not be considered by many to be a first-line treatment for major depression, but it certainly would not be absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy as might be presumed by the assignment of a category D label.

Lithium and sodium valproate provide another example of the limitations of the old system, which will be addressed in the new system. While the teratogenicity of both agents has been well described, the absolute risk of malformations with fetal exposure to lithium is approximately 0.05%- 0.1%, but the risk of neural tube defects with sodium valproate is estimated at 8%. Complicating the issue further, in 2013, the FDA announced that sodium valproate had been changed from a category D to X for migraine prevention, but retained the category D classification for other indications.

Placing lithium in category D suggests a relative contraindication and yet discontinuing that medication during pregnancy can put the mother and her baby at risk, given the data supporting the rapid onset of relapse in women who stop mood stabilizers during pregnancy.

For women maintained on lithium for recurrent or brittle bipolar disorder, the drug would certainly not be contraindicated and may afford critical emotional well-being and protection from relapse during pregnancy; the clinical scenario of discontinuation of lithium proximate to or during pregnancy and subsequent relapse of underlying illness is a serious clinical matter frequently demanding urgent intervention.

Still another example of the incomplete informative value of the older system is found in the assignment of atypical antipsychotics into different risk categories. Lurasidone (Latuda), approved in 2010, is in category B, but other atypical antipsychotics are in category C. One might assume that this implies that there are more reproductive safety data available on lurasidone supporting safety, but in fact, reproductive safety data for this molecule are extremely limited, and the absence of adverse event information resulted in a category B. This is a great example of the clinical maxim that incomplete or sparse data is just that; it does not imply safety, it implies that we do not know a lot about the safety of a medication.

If the old system of pregnancy labeling was arbitrary, the PLLR will be more descriptive. Safety information during pregnancy and lactation in the drug label will appear in a section on pregnancy, reformatted to include a risk summary, clinical considerations, and data subsections, as well as a section on lactation, and a section on females and males of reproductive potential.

Ongoing revision of the label as information becomes outdated is a requirement, and manufacturers will be obligated to include information on whether there is a pregnancy registry for the given drug. The goal of the PLLR is thus to provide the patient and clinician with information which addresses both sides of the risk-benefit decision for a given medicine – risks of fetal drug exposure and the risk of untreated illness for the woman and baby, a factor that is not addressed at all with the current system.

Certainly, the new label system will be a charge to industry to establish, support, and encourage enrollment in well-designed pregnancy registries across therapeutic areas to provide ample amounts of good quality data that can then be used by patients along with their physicians to make the most appropriate clinical decisions.

Much of the currently available reproductive safety information on drugs is derived from spontaneous reports, where there has been inconsistent information and variable levels of scrutiny with respect to outcomes assessment, and from small, underpowered cohort studies or large administrative databases. Postmarketing surveillance efforts have been rather modest and have not been a priority for manufacturers in most cases. Hopefully, this will change as pregnancy registries become part of routine postmarketing surveillance.

The new system will not be a panacea, and I expect there will be growing pains, considering the huge challenge of reducing the available data of varying quality into distinct paragraphs. It may also be difficult to synthesize the volume of data and the nuanced differences between certain studies into a paragraph on risk assessment. The task will be simpler for some agents and more challenging for others where the data are less consistent. Questions also remain as to how data will be revised over time.

But despite these challenges, the new system represents a monumental change, and in my mind, will bring a focus to the importance of the issue of quantifying reproductive safety of medications used by women either planning to get pregnant or who are pregnant or breastfeeding, across therapeutic areas. Of particular importance, the new system will hopefully lead to more discussion between physician and patient about what is and is not known about the reproductive safety of a medication, versus a cursory reference to some previously assigned category label.

Our group has shown that when it comes to making decisions about using medication during pregnancy, even when given the same information, women will make different decisions. This is critical since people make personal decisions about the use of these medications in collaboration with their doctors on a case-by-case basis, based on personal preference, available information, and clinical conditions across a spectrum of severity.

As the FDA requirements shift from the arbitrary category label assignment to a more descriptive explanation of risk, based on available data, an important question will be what mechanism will be used by regulators collaborating with industry to update labels with the growing amounts of information on reproductive safety, particularly if there is a commitment from industry to enhance postmarketing surveillance with more pregnancy registries.

Better data can catalyze thoughtful discussions between doctor and patient regarding decisions to use or defer treatment with a given medicine. One might wonder if the new system will open a Pandora’s box. But I believe in this case, opening Pandora’s box would be welcome because it will hopefully lead to a more careful examination of the available information regarding reproductive safety and more informed decisions on the part of patients.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information about reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of antidepressant medications and is the principal investigator of the National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics, which receives support from the manufacturers of those drugs. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected]. Scan this QR code or go to obgynnews.com to view similar columns.

Dr. Robert L. Barbieri's Editors Picks for January 2015

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here for the rest of January 2015 issue.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here for the rest of January 2015 issue.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Click here for the rest of January 2015 issue.

ACOG, SMFM propose definitions for maternal care sites

In a first-time consensus document, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have proposed a new classification system for maternal care facilities that includes minimum standards for each level of care.

Implementing these definitions nationally could help decrease maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, improve regional availability of care for high-risk pregnant women, and enhance the collection of related data, according to the two organizations. The consensus document appears in the February issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:502-15).

The classification of maternal facilities mirrors the model already in use for neonatal care facilities and comes as U.S. maternal mortality rates have climbed. The United States now ranks 60th in the world for maternal mortality, the document notes.

“It is essential to remember that, when we are addressing obstetrical outcomes, we have two very important patients: mother and child,” Dr. Sarah J. Kilpatrick, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and lead author of the document, said in a statement. “Our goal for these consensus recommendations is to create a system for maternal care that complements and supplements the current neonatal framework in order to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality across the country.”

The consensus document defines five categories of maternal care centers:

Level 1 (basic care) facilities have the same capacities as birth centers but also can perform common emergency procedures, such as unplanned cesarean deliveries and massive transfusions. They must have the appropriate blood products and analgesia and anesthesia services. Unlike birth centers, level 1 facilities can readily handle term deliveries of twins, preeclampsia at term that is not severe, and uncomplicated cesarean deliveries. Managers of these facilities are able to create formal protocols for transferring high-risk patients, as well as education and quality improvement programs.

Level 2 (specialty care) facilities are able to handle moderately complex cases, such as severe preeclampsia or placental previa without prior uterine surgery. These facilities have an attending ob.gyn. available at all times, plus in-person or remote access to a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist. They also have basic ultrasound equipment, equipment for obese women such as bariatric beds, and CT scanning equipment. They ideally have MRI scanning and interpretation, according to the consensus document.

Level 3 (subspecialty care) facilities meet level 2 criteria and also have continuous, on-site intensive care, maternal-fetal medicine services that are led by a maternal-fetal subspecialist, and advanced imaging and ventilator equipment. These facilities may act as regional referral centers and are appropriate for women with suspected placenta accreta or placenta previa with prior uterine surgery, suspected placenta percreta, adult respiratory syndrome, or severe eclampsia at less than 34 weeks’ gestation.

Level 4 (regional perinatal health care) facilities offer medical and surgical care for the most critical cases, including severe pulmonary hypertension; liver failure; and conditions that require organ transplantation, neurosurgery, or cardiac surgery. These facilities have continuously available maternal-fetal medicine care teams that are highly experienced in handling pregnant and postpartum women in critical condition. Level 4 facilities also coordinate referral and transport, provide outreach education for local facilities and providers, and help collect and analyze regional data for quality improvement programs.

Leaders at these facilities should understand their sites’ capabilities and limitations and have a “well-defined threshold for transferring women to health care facilities that offer a higher level of care,” ACOG and SMFM wrote. The organizations also called on state and regional authorities to partner with maternal care facilities to coordinate a system of care.

The new consensus statement does not address high-risk neonatal care, but such care must be coordinated with maternal care, ACOG and SMFM officials wrote.

Several groups endorsed the consensus definitions, including the American Association of Birth Centers; the American College of Nurse-Midwives; the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; and the Commission for the Accreditation of Birth Centers. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a first-time consensus document, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have proposed a new classification system for maternal care facilities that includes minimum standards for each level of care.

Implementing these definitions nationally could help decrease maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, improve regional availability of care for high-risk pregnant women, and enhance the collection of related data, according to the two organizations. The consensus document appears in the February issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:502-15).

The classification of maternal facilities mirrors the model already in use for neonatal care facilities and comes as U.S. maternal mortality rates have climbed. The United States now ranks 60th in the world for maternal mortality, the document notes.

“It is essential to remember that, when we are addressing obstetrical outcomes, we have two very important patients: mother and child,” Dr. Sarah J. Kilpatrick, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and lead author of the document, said in a statement. “Our goal for these consensus recommendations is to create a system for maternal care that complements and supplements the current neonatal framework in order to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality across the country.”

The consensus document defines five categories of maternal care centers:

Level 1 (basic care) facilities have the same capacities as birth centers but also can perform common emergency procedures, such as unplanned cesarean deliveries and massive transfusions. They must have the appropriate blood products and analgesia and anesthesia services. Unlike birth centers, level 1 facilities can readily handle term deliveries of twins, preeclampsia at term that is not severe, and uncomplicated cesarean deliveries. Managers of these facilities are able to create formal protocols for transferring high-risk patients, as well as education and quality improvement programs.

Level 2 (specialty care) facilities are able to handle moderately complex cases, such as severe preeclampsia or placental previa without prior uterine surgery. These facilities have an attending ob.gyn. available at all times, plus in-person or remote access to a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist. They also have basic ultrasound equipment, equipment for obese women such as bariatric beds, and CT scanning equipment. They ideally have MRI scanning and interpretation, according to the consensus document.

Level 3 (subspecialty care) facilities meet level 2 criteria and also have continuous, on-site intensive care, maternal-fetal medicine services that are led by a maternal-fetal subspecialist, and advanced imaging and ventilator equipment. These facilities may act as regional referral centers and are appropriate for women with suspected placenta accreta or placenta previa with prior uterine surgery, suspected placenta percreta, adult respiratory syndrome, or severe eclampsia at less than 34 weeks’ gestation.

Level 4 (regional perinatal health care) facilities offer medical and surgical care for the most critical cases, including severe pulmonary hypertension; liver failure; and conditions that require organ transplantation, neurosurgery, or cardiac surgery. These facilities have continuously available maternal-fetal medicine care teams that are highly experienced in handling pregnant and postpartum women in critical condition. Level 4 facilities also coordinate referral and transport, provide outreach education for local facilities and providers, and help collect and analyze regional data for quality improvement programs.

Leaders at these facilities should understand their sites’ capabilities and limitations and have a “well-defined threshold for transferring women to health care facilities that offer a higher level of care,” ACOG and SMFM wrote. The organizations also called on state and regional authorities to partner with maternal care facilities to coordinate a system of care.

The new consensus statement does not address high-risk neonatal care, but such care must be coordinated with maternal care, ACOG and SMFM officials wrote.

Several groups endorsed the consensus definitions, including the American Association of Birth Centers; the American College of Nurse-Midwives; the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; and the Commission for the Accreditation of Birth Centers. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a first-time consensus document, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have proposed a new classification system for maternal care facilities that includes minimum standards for each level of care.

Implementing these definitions nationally could help decrease maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, improve regional availability of care for high-risk pregnant women, and enhance the collection of related data, according to the two organizations. The consensus document appears in the February issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:502-15).

The classification of maternal facilities mirrors the model already in use for neonatal care facilities and comes as U.S. maternal mortality rates have climbed. The United States now ranks 60th in the world for maternal mortality, the document notes.

“It is essential to remember that, when we are addressing obstetrical outcomes, we have two very important patients: mother and child,” Dr. Sarah J. Kilpatrick, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles and lead author of the document, said in a statement. “Our goal for these consensus recommendations is to create a system for maternal care that complements and supplements the current neonatal framework in order to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality across the country.”

The consensus document defines five categories of maternal care centers:

Level 1 (basic care) facilities have the same capacities as birth centers but also can perform common emergency procedures, such as unplanned cesarean deliveries and massive transfusions. They must have the appropriate blood products and analgesia and anesthesia services. Unlike birth centers, level 1 facilities can readily handle term deliveries of twins, preeclampsia at term that is not severe, and uncomplicated cesarean deliveries. Managers of these facilities are able to create formal protocols for transferring high-risk patients, as well as education and quality improvement programs.

Level 2 (specialty care) facilities are able to handle moderately complex cases, such as severe preeclampsia or placental previa without prior uterine surgery. These facilities have an attending ob.gyn. available at all times, plus in-person or remote access to a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist. They also have basic ultrasound equipment, equipment for obese women such as bariatric beds, and CT scanning equipment. They ideally have MRI scanning and interpretation, according to the consensus document.

Level 3 (subspecialty care) facilities meet level 2 criteria and also have continuous, on-site intensive care, maternal-fetal medicine services that are led by a maternal-fetal subspecialist, and advanced imaging and ventilator equipment. These facilities may act as regional referral centers and are appropriate for women with suspected placenta accreta or placenta previa with prior uterine surgery, suspected placenta percreta, adult respiratory syndrome, or severe eclampsia at less than 34 weeks’ gestation.

Level 4 (regional perinatal health care) facilities offer medical and surgical care for the most critical cases, including severe pulmonary hypertension; liver failure; and conditions that require organ transplantation, neurosurgery, or cardiac surgery. These facilities have continuously available maternal-fetal medicine care teams that are highly experienced in handling pregnant and postpartum women in critical condition. Level 4 facilities also coordinate referral and transport, provide outreach education for local facilities and providers, and help collect and analyze regional data for quality improvement programs.

Leaders at these facilities should understand their sites’ capabilities and limitations and have a “well-defined threshold for transferring women to health care facilities that offer a higher level of care,” ACOG and SMFM wrote. The organizations also called on state and regional authorities to partner with maternal care facilities to coordinate a system of care.

The new consensus statement does not address high-risk neonatal care, but such care must be coordinated with maternal care, ACOG and SMFM officials wrote.

Several groups endorsed the consensus definitions, including the American Association of Birth Centers; the American College of Nurse-Midwives; the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses; and the Commission for the Accreditation of Birth Centers. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

CDC: Opioid use high among reproductive age women

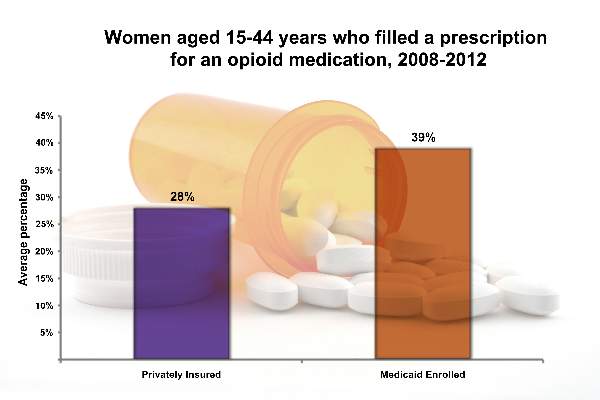

Nearly 40% of a reproductive age women enrolled in Medicaid and nearly 30% of those with private insurance filled an opioid prescription between 2008 and 2012, rising concerns that opioid use by women during their peak reproductive years may lead to an increase in birth defects, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Many women of reproductive age are taking these medicines and may not know they are pregnant and therefore may be unknowingly exposing their unborn child,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a statement. “That’s why it’s critical for health care professionals to take a thorough health assessment before prescribing these medicines to women of reproductive age.”

Using claims data, CDC researchers analyzed opioid prescriptions for between 400,000 and 800,000 Medicaid-enrolled women aged 15-44 years, and between 4.4 and 6.6 million privately insured women in the same age range for each year during 2008-2012. The findings were published on Jan. 22 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2015;64:37-41).

From 2008 to 2012, 39.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women of reproductive age filled an opioid prescription at an outpatient pharmacy, compared with 27.7% among privately-insured women. The year with the highest rate of claims was 2009, with 41.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women and 29.1% of privately insured women filling opioid prescriptions.

The highest subset of opioid prescriptions was in the 30-34 year-old age group for privately insured women (30.9%), and in the 40-44 year-old age group for Medicaid-enrolled women (52.5%).

From 2009 to 2012, there appeared to be a drop in the frequency of opioid use by women of reproductive age, regardless of insurance type, but the researchers urged caution in drawing conclusions about changes over time.

“The apparent decline might indicate improvements in opioid prescribing practices; however, given the potential changes in the composition of the sample used for the privately insured claims data and in the states included in the Medicaid sample each year, this conclusion cannot be drawn from these data,” the researchers wrote.

The most commonly prescribed opioid groups were hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone. On average, over the course of the study period, hydrocodone was prescribed 17.5% of the time, followed by codeine (6.9%) and then oxycodone (5.5%) for privately insured women. For women with Medicaid coverage, the rates were higher across the board: 25% for hydrocodone, 9.4% for codeine, and 13.0% for oxycodone.

Nearly 40% of a reproductive age women enrolled in Medicaid and nearly 30% of those with private insurance filled an opioid prescription between 2008 and 2012, rising concerns that opioid use by women during their peak reproductive years may lead to an increase in birth defects, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Many women of reproductive age are taking these medicines and may not know they are pregnant and therefore may be unknowingly exposing their unborn child,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a statement. “That’s why it’s critical for health care professionals to take a thorough health assessment before prescribing these medicines to women of reproductive age.”

Using claims data, CDC researchers analyzed opioid prescriptions for between 400,000 and 800,000 Medicaid-enrolled women aged 15-44 years, and between 4.4 and 6.6 million privately insured women in the same age range for each year during 2008-2012. The findings were published on Jan. 22 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2015;64:37-41).

From 2008 to 2012, 39.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women of reproductive age filled an opioid prescription at an outpatient pharmacy, compared with 27.7% among privately-insured women. The year with the highest rate of claims was 2009, with 41.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women and 29.1% of privately insured women filling opioid prescriptions.

The highest subset of opioid prescriptions was in the 30-34 year-old age group for privately insured women (30.9%), and in the 40-44 year-old age group for Medicaid-enrolled women (52.5%).

From 2009 to 2012, there appeared to be a drop in the frequency of opioid use by women of reproductive age, regardless of insurance type, but the researchers urged caution in drawing conclusions about changes over time.

“The apparent decline might indicate improvements in opioid prescribing practices; however, given the potential changes in the composition of the sample used for the privately insured claims data and in the states included in the Medicaid sample each year, this conclusion cannot be drawn from these data,” the researchers wrote.

The most commonly prescribed opioid groups were hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone. On average, over the course of the study period, hydrocodone was prescribed 17.5% of the time, followed by codeine (6.9%) and then oxycodone (5.5%) for privately insured women. For women with Medicaid coverage, the rates were higher across the board: 25% for hydrocodone, 9.4% for codeine, and 13.0% for oxycodone.

Nearly 40% of a reproductive age women enrolled in Medicaid and nearly 30% of those with private insurance filled an opioid prescription between 2008 and 2012, rising concerns that opioid use by women during their peak reproductive years may lead to an increase in birth defects, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Many women of reproductive age are taking these medicines and may not know they are pregnant and therefore may be unknowingly exposing their unborn child,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a statement. “That’s why it’s critical for health care professionals to take a thorough health assessment before prescribing these medicines to women of reproductive age.”

Using claims data, CDC researchers analyzed opioid prescriptions for between 400,000 and 800,000 Medicaid-enrolled women aged 15-44 years, and between 4.4 and 6.6 million privately insured women in the same age range for each year during 2008-2012. The findings were published on Jan. 22 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2015;64:37-41).

From 2008 to 2012, 39.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women of reproductive age filled an opioid prescription at an outpatient pharmacy, compared with 27.7% among privately-insured women. The year with the highest rate of claims was 2009, with 41.4% of Medicaid-enrolled women and 29.1% of privately insured women filling opioid prescriptions.

The highest subset of opioid prescriptions was in the 30-34 year-old age group for privately insured women (30.9%), and in the 40-44 year-old age group for Medicaid-enrolled women (52.5%).

From 2009 to 2012, there appeared to be a drop in the frequency of opioid use by women of reproductive age, regardless of insurance type, but the researchers urged caution in drawing conclusions about changes over time.

“The apparent decline might indicate improvements in opioid prescribing practices; however, given the potential changes in the composition of the sample used for the privately insured claims data and in the states included in the Medicaid sample each year, this conclusion cannot be drawn from these data,” the researchers wrote.

The most commonly prescribed opioid groups were hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone. On average, over the course of the study period, hydrocodone was prescribed 17.5% of the time, followed by codeine (6.9%) and then oxycodone (5.5%) for privately insured women. For women with Medicaid coverage, the rates were higher across the board: 25% for hydrocodone, 9.4% for codeine, and 13.0% for oxycodone.

FROM THE MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Folic acid fortification leads to bigger drops in neural tube defects

Mandatory folic acid fortification of grain products has resulted in 1,326 fewer neural tube defects among U.S. births each year, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This estimate is one-third higher than previous calculations, which estimated that fortification averted 1,000 neural tube-affected pregnancies a year.

“Factors that could have helped contribute to the difference include a gradual increase in the number of annual live births in the United States during the postfortification period and data variations caused by differences in surveillance methodology,” Jennifer Williams of the CDC and her colleagues wrote in the Jan. 16 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Insufficient folic acid intake increases the risk of neural tube defects, which can lead to conditions such as anencephaly and spina bifida. To address folic acid deficiencies in women, the United States mandated in 1998 that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with 140 mcg of folic acid per 100 g.

From 1995-1996 to the postfortification period of 1999-2011, incidence of anencephaly and spina bifida declined 28% overall, with declines in neural tube defects seen for white, black, and Hispanic pregnancies. But the rates of neural tube defects were the highest among Hispanic women, potentially due to genetic factors or to insufficient folic acid intake. One strategy to reduce rates among Hispanic women would be to fortify corn masa flour, thereby averting an estimated 40 additional neural tube defects a year, the researchers wrote (MMWR 2015;64:1-5).

The drop in neural tube defects carries a financial benefit, as well. Anencephaly, which is always fatal, costs an estimated $5,415 per case, and spina bifida costs an estimated $560,000 over a lifetime. Overall, the averted cases represent about $508 million in annual savings.

In addition to fortification, the CDC recommends that all women of childbearing age take 400 mcg of folic acid daily if they might become pregnant. Women with a previous neural tube defect–affected pregnancy are recommended to take a higher dose of 4 mg/day, beginning at least 4 weeks before conception and continuing through the first trimester.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Mandatory folic acid fortification of grain products has resulted in 1,326 fewer neural tube defects among U.S. births each year, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This estimate is one-third higher than previous calculations, which estimated that fortification averted 1,000 neural tube-affected pregnancies a year.

“Factors that could have helped contribute to the difference include a gradual increase in the number of annual live births in the United States during the postfortification period and data variations caused by differences in surveillance methodology,” Jennifer Williams of the CDC and her colleagues wrote in the Jan. 16 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Insufficient folic acid intake increases the risk of neural tube defects, which can lead to conditions such as anencephaly and spina bifida. To address folic acid deficiencies in women, the United States mandated in 1998 that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with 140 mcg of folic acid per 100 g.

From 1995-1996 to the postfortification period of 1999-2011, incidence of anencephaly and spina bifida declined 28% overall, with declines in neural tube defects seen for white, black, and Hispanic pregnancies. But the rates of neural tube defects were the highest among Hispanic women, potentially due to genetic factors or to insufficient folic acid intake. One strategy to reduce rates among Hispanic women would be to fortify corn masa flour, thereby averting an estimated 40 additional neural tube defects a year, the researchers wrote (MMWR 2015;64:1-5).

The drop in neural tube defects carries a financial benefit, as well. Anencephaly, which is always fatal, costs an estimated $5,415 per case, and spina bifida costs an estimated $560,000 over a lifetime. Overall, the averted cases represent about $508 million in annual savings.

In addition to fortification, the CDC recommends that all women of childbearing age take 400 mcg of folic acid daily if they might become pregnant. Women with a previous neural tube defect–affected pregnancy are recommended to take a higher dose of 4 mg/day, beginning at least 4 weeks before conception and continuing through the first trimester.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Mandatory folic acid fortification of grain products has resulted in 1,326 fewer neural tube defects among U.S. births each year, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This estimate is one-third higher than previous calculations, which estimated that fortification averted 1,000 neural tube-affected pregnancies a year.

“Factors that could have helped contribute to the difference include a gradual increase in the number of annual live births in the United States during the postfortification period and data variations caused by differences in surveillance methodology,” Jennifer Williams of the CDC and her colleagues wrote in the Jan. 16 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Insufficient folic acid intake increases the risk of neural tube defects, which can lead to conditions such as anencephaly and spina bifida. To address folic acid deficiencies in women, the United States mandated in 1998 that all enriched cereal grain products be fortified with 140 mcg of folic acid per 100 g.

From 1995-1996 to the postfortification period of 1999-2011, incidence of anencephaly and spina bifida declined 28% overall, with declines in neural tube defects seen for white, black, and Hispanic pregnancies. But the rates of neural tube defects were the highest among Hispanic women, potentially due to genetic factors or to insufficient folic acid intake. One strategy to reduce rates among Hispanic women would be to fortify corn masa flour, thereby averting an estimated 40 additional neural tube defects a year, the researchers wrote (MMWR 2015;64:1-5).

The drop in neural tube defects carries a financial benefit, as well. Anencephaly, which is always fatal, costs an estimated $5,415 per case, and spina bifida costs an estimated $560,000 over a lifetime. Overall, the averted cases represent about $508 million in annual savings.

In addition to fortification, the CDC recommends that all women of childbearing age take 400 mcg of folic acid daily if they might become pregnant. Women with a previous neural tube defect–affected pregnancy are recommended to take a higher dose of 4 mg/day, beginning at least 4 weeks before conception and continuing through the first trimester.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Key clinical point: Women of childbearing age should take 400 mcg of folic acid daily if they might become pregnant. Women with a previous neural tube defect–affected pregnancy should take 4 mg/day of folic acid.

Major finding: Approximately 1,326 fewer babies with neural tube defects have been born annually since mandatory folic acid fortification in grain products began.

Data source: Data analysis from 19 U.S. population-based birth defects surveillance programs from 1999 to 2011.

Disclosures: No external funding was noted. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

2015 Update on obstetrics

Over the past year, much attention has been devoted to labor curves. Is the original Friedman labor curve, which dates to the 1950s, still applicable today? Or do contemporary women labor differently? And if we update our approach to labor management, can we reduce the rate of primary cesarean?

In this Update, we explore these questions, as well as two others:

- How do we minimize infectious morbidity in pregnancy?

- How much prenatal screening is too much?

Is adherence to new labor curves the best way to reduce the rate of primary cesarean?

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 1: Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):693–711.

Cohen WR, Friedman EA. Perils of the new labor management guidelines [published online ahead of print September 16, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.008.

In 2012, the cesarean delivery rate in the United States remained at 32.8%, a high percentage when one considers the increased risks that major abdominal surgery poses in both the short and long term (blood loss, transfusion, infection, venous thromboembolism, abnormal placentation, hysterectomy).1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have made it a priority to reduce the cesarean delivery rate, focusing their efforts on the primary cesarean. In March 2014, they jointly issued guidelines on the “Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery,” highlighting labor dystocia as a top cause.

When contemporary data from the Consortium on Safe Labor were applied to the original Friedman labor curve, investigators found that the active phase of labor may be slower than previously thought.2 The maximum slope for the rate of cervical change was not observed until 6 cm of dilation. This finding potentially changes the point at which arrest of the active phase may be declared. The maximum duration of augmentation with oxytocin also has been extended, based on studies that demonstrated increased vaginal delivery rates.

The Consortium on Safe Labor proposed that, by subjecting a contemporary population to decades-old standards, we have been intervening with primary cesarean too early in the treatment of labor dystocia.

What the guidelines say

The new recommendations from ACOG-SMFM suggest that arrest of the active phase of labor can be declared only when the patient is dilated at least 6 cm with ruptured membranes after either 4 hours of adequate uterine contractions or at least 6 hours of oxytocin administration with inadequate uterine contractions or no cervical change.

Although the recommendations state that there is no maximum duration of the second stage of labor, we may increase the vaginal delivery rate by increasing the duration of pushing to 2 hours for a multiparous patient and 3 hours for a nulliparous patient (with an additional hour when an epidural is given).

Are the recommendations ready for prime time?

In response to the recommendations, Cohen and Friedman (author of the original labor curve) published “Perils of the new labor management guidelines,” cited above. In this commentary, they caution against universal acceptance of the guidelines without further validation. They argue that the analytical method used—and not labor itself—has changed, with possible selection biases and unadjusted confounders altering the shape of the dilatation curve. Cohen and Friedman suggest that serial evaluation of the patient is preferable to an arbitrary cutoff of 6 cm.

They also criticize other aspects of the guidelines, focusing on universal use of intrauterine pressure catheters, amniotomy, and a specific duration of pushing without consideration of descent. A “one size fits all” approach may incur risk to both the mother and the fetus without proven benefit, they contend. Clinical judgment and continuous evaluation of the likelihood and safety of vaginal delivery also are encouraged rather than a reliance on labor curves in isolation.

They urge further validation before adoption of the recommendations. “If we direct our clinical and basic science investigations to the goal of practicing obstetrics in a manner that optimizes maternal and newborn outcomes, the ideal cesarean delivery rate, whatever it may be, will follow,” they write.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Proceed with caution when applying labor curves to patients. Use clinical judgment in conjunction with any new guidelines.

Be vigilant for infectious threats to your obstetric population

Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM, Callaghan WM, Meaney-Delman D, Rasmussen SA. What obstetrician-gynecologists should know about Ebola: a perspective from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):1005–1010.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 614: Management of pregnant women with presumptive exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1241–1244.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 608: Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):648–651.

We no longer consider pregnancy an immunosuppressed state but, rather, a more immune-modulated system. However, there is no question that the unique physiologic state of pregnancy places a woman and her fetus at increased risk for infection. This was devastatingly obvious during the H1N1 epidemic of 2009 and was reemphasized during a 2014 outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes. We are reminded again during the largest Ebola virus outbreak in history in West Africa, where women have been disproportionately affected.

No neonates have survived Ebola

Although Ebola infections in the United States have been very few, vigilance for people at risk of infection and preparedness to act in the case of infection are vitally important.

The Ebola virus is thought to be spread to humans through contact with infected fruit bats or primates. Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with blood or body fluids (urine, feces, sweat, saliva, breast milk, vomit, semen) of an infected person or contaminated objects (needles, syringes). The incubation period is 2 to 21 days (average, 8–10 days).

Infected people become contagious only upon the appearance of fever and symptoms, which include headache, muscle pain, fatigue, weakness, diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, bleeding, and bruising. The differential diagnosis includes malaria, typhoid, Lassa fever, meningococcal disease, influenza, and Marburg virus.

Treatment of Ebola is supportive care and isolation (standard, contact, and droplet precautions). Prevention is through infection-control precautions and isolation and testing of those exposed, with monitoring for 21 days.

Although pregnant women are not thought to be more susceptible to infection, they are at increased risk of severe illness and mortality, as well as spontaneous abortion and pregnancy-related hemorrhage. No neonates of women infected with Ebola have survived to date.

The CDC recommends that physicians screen patients who have traveled to West Africa and those with fevers and implement appropriate isolation and infection-control precautions. Many hospitals have developed Ebola task forces with this in mind.

Updated information is available at www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/index.html.

Pregnant women are highly susceptible to Listeriosis

A nationwide food recall in mid-2014 prompted significant media attention to L monocytogenes, particularly its effect on pregnant women, who have an incidence of Listerial infection 13 times higher than the general population. Although maternal illness is relatively mild, ranging from a complete lack of symptoms to febrile diarrhea, there is an increased risk to the fetus or neonate of loss, preterm labor, neonatal sepsis, meningitis, and death. The perinatal mortality rate is 29%.

The mainstay of prevention during pregnancy is improved food safety and handling, as well as counseling of pregnant women to avoid unpasteurized soft cheeses, raw milk, and unwashed fruits and vegetables, and to avoid or heat thoroughly lunch meats and hot dogs.

When a pregnant woman is exposed to Listeria, management depends on the clinical scenario, as outlined by ACOG:

- Asymptomatic pregnant women do not require testing, treatment, or fetal surveillance. Any development of symptoms within 2 months may justify further evaluation, however.

- Pregnant women with mild gastro-intestinal or flulike symptoms but no fever also can be managed expectantly. Blood cultures may be appropriate; if positive, antibiotic therapy should be initiated.

- A febrile pregnant woman should have blood cultures assessed and be started on antibiotics. The preferred regimen is intravenous ampicillin 6 g/day with or without gentamicin for 14 days. If delivery occurs, placental cultures may be assessed. Listeriosis also can be diagnosed by amniocentesis. Stool cultures are not recommended.

Influenza is largely preventable

It is important to remember that one of the most dangerous viruses for pregnant women can be prevented. However, only 38% to 52% of women who should have received the influenza vaccine around the time of pregnancy actually did so between 2009 and 2013, according to the ACOG Committee Opinion cited above. Pregnant and postpartum women are at increased risk of serious illness, prolonged hospitalization, and death from influenza infection.

The vaccine is safe and effective. Not only does it prevent maternal morbidity and mortality, but it reduces neonatal complications. Inactivated vaccine is recommended for all pregnant women at any gestational age during the flu season.

Because many women are hesitant to accept the vaccine, accurate education is essential to dispel misconceptions about it and its components. It has been shown that if an obstetric clinician recommends the vaccine and makes it available, pregnant patients are five to 50 times more likely to receive it. As obstetricians, we are compelled to make this a priority in our practice.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Be alert and ready to act if an infectious threat is noted in your obstetric population. Get your flu shot. Give it to your obstetric patients. And don’t forget that ACOG also supports the administration of one dose of the tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccine during each pregnancy.

How much prenatal screening is too much?

Goetzinger KR, Odibo AO. Screening for abnormal placentation and adverse pregnancy outcomes with maternal serum biomarkers in the second trimester. Prenatal Diagn. 2014;34(7):635–641.

D’Antonio F, Rijo C, Thilaganathan B, et al. Association between first-trimester maternal serum pregnancy associated plasma protein-A and obstetric complications. Prenatal Diagn. 2013;33(9):839–847.

Dugoff L; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. First- and second-trimester maternal serum markers for aneuploidy and adverse obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):1052–1061.

Martin A, Krishna I, Martina B, et al. Can the quantity of cell-free fetal DNA predict preeclampsia: a systematic review. Prenatal Diagn. 2014;34(7): 685–691.

Audibert F, Boucoiran I, An N, et al. Screening for preeclampsia using first-trimester serum markers and uterine artery Doppler in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):383.e1–e8.

Myatt L, Clifton RG, Roberts JM, et al. First-trimester prediction of preeclampsia in nulliparous women at low risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(6):1234–1242.

The placenta of a normal pregnancy secretes small amounts of a variety of biomarkers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin, unconjugated estriol, inhibin A, pregnancy-associated placental protein A (PAPP-A), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase, and placental growth factor.

The association between abnormal maternal serum biomarkers and abnormal pregnancy outcomes has been known since the 1970s, when elevated AFP was noted in pregnancies with fetal open neural tube defects. Shortly thereafter, low levels of AFP were associated with fetuses with trisomy 21.

One theory is that the abnormality in pregnancy leads to abnormal regulation at the level of the fetal-placental interface and over- or under-secretion of the various biomarkers. An offshoot of this theory is the idea that abnormal placentation (ie, preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction, accreta) also may be reflected in elevated or suppressed secretion of placental biomarkers, which could be used to screen for these conditions during pregnancy.

PAPP-A is a placental serum marker that is a component of first-trimester genetic screening. It is a marker of placental function, and low levels have been associated with fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and fetal loss. Another first-trimester marker associated with adverse outcomes is cell-free fetal DNA. This DNA, found in the maternal blood, is a product of placental apoptosis, and elevated levels have been demonstrated in women who develop preeclampsia.

Although many of the biomarkers listed here are not available specifically as a clinical screening test in the United States, the link to common genetic screens makes it tempting to try to add prediction of preeclampsia and other information to an existing test. If specific numbers are reported on the genetic screen for the different markers, that information is already there, and some companies may flag abnormally high or low levels.

However, although the association between abnormal pregnancy outcomes and abnormal biomarkers is well established in the literature, the clinical predictive value is not—nor is there always an effective intervention available. One could argue that low-dose aspirin, which is already recommended for patients with a prior delivery before 34 weeks due to preeclampsia, or more than one prior pregnancy with preeclampsia, could be recommended for patients identified on early screens to be at increased risk for preeclampsia. This approach should be tested in randomized clinical trials before universal adoption.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Although it is tempting to use associations to predict adverse events, the clinical value of doing so has not yet been proven. Exercise caution before potentially causing concern for both you and your patient.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2012. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62(9):1–67.

2. Zhang J, Landy HJ, Branch DW, et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Consortium on Safe Labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1281–1287.

Over the past year, much attention has been devoted to labor curves. Is the original Friedman labor curve, which dates to the 1950s, still applicable today? Or do contemporary women labor differently? And if we update our approach to labor management, can we reduce the rate of primary cesarean?

In this Update, we explore these questions, as well as two others:

- How do we minimize infectious morbidity in pregnancy?

- How much prenatal screening is too much?

Is adherence to new labor curves the best way to reduce the rate of primary cesarean?

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetric Care Consensus No. 1: Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):693–711.

Cohen WR, Friedman EA. Perils of the new labor management guidelines [published online ahead of print September 16, 2014]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.008.

In 2012, the cesarean delivery rate in the United States remained at 32.8%, a high percentage when one considers the increased risks that major abdominal surgery poses in both the short and long term (blood loss, transfusion, infection, venous thromboembolism, abnormal placentation, hysterectomy).1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have made it a priority to reduce the cesarean delivery rate, focusing their efforts on the primary cesarean. In March 2014, they jointly issued guidelines on the “Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery,” highlighting labor dystocia as a top cause.

When contemporary data from the Consortium on Safe Labor were applied to the original Friedman labor curve, investigators found that the active phase of labor may be slower than previously thought.2 The maximum slope for the rate of cervical change was not observed until 6 cm of dilation. This finding potentially changes the point at which arrest of the active phase may be declared. The maximum duration of augmentation with oxytocin also has been extended, based on studies that demonstrated increased vaginal delivery rates.

The Consortium on Safe Labor proposed that, by subjecting a contemporary population to decades-old standards, we have been intervening with primary cesarean too early in the treatment of labor dystocia.

What the guidelines say

The new recommendations from ACOG-SMFM suggest that arrest of the active phase of labor can be declared only when the patient is dilated at least 6 cm with ruptured membranes after either 4 hours of adequate uterine contractions or at least 6 hours of oxytocin administration with inadequate uterine contractions or no cervical change.

Although the recommendations state that there is no maximum duration of the second stage of labor, we may increase the vaginal delivery rate by increasing the duration of pushing to 2 hours for a multiparous patient and 3 hours for a nulliparous patient (with an additional hour when an epidural is given).

Are the recommendations ready for prime time?

In response to the recommendations, Cohen and Friedman (author of the original labor curve) published “Perils of the new labor management guidelines,” cited above. In this commentary, they caution against universal acceptance of the guidelines without further validation. They argue that the analytical method used—and not labor itself—has changed, with possible selection biases and unadjusted confounders altering the shape of the dilatation curve. Cohen and Friedman suggest that serial evaluation of the patient is preferable to an arbitrary cutoff of 6 cm.

They also criticize other aspects of the guidelines, focusing on universal use of intrauterine pressure catheters, amniotomy, and a specific duration of pushing without consideration of descent. A “one size fits all” approach may incur risk to both the mother and the fetus without proven benefit, they contend. Clinical judgment and continuous evaluation of the likelihood and safety of vaginal delivery also are encouraged rather than a reliance on labor curves in isolation.

They urge further validation before adoption of the recommendations. “If we direct our clinical and basic science investigations to the goal of practicing obstetrics in a manner that optimizes maternal and newborn outcomes, the ideal cesarean delivery rate, whatever it may be, will follow,” they write.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Proceed with caution when applying labor curves to patients. Use clinical judgment in conjunction with any new guidelines.

Be vigilant for infectious threats to your obstetric population

Jamieson DJ, Uyeki TM, Callaghan WM, Meaney-Delman D, Rasmussen SA. What obstetrician-gynecologists should know about Ebola: a perspective from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):1005–1010.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 614: Management of pregnant women with presumptive exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1241–1244.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 608: Influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):648–651.

We no longer consider pregnancy an immunosuppressed state but, rather, a more immune-modulated system. However, there is no question that the unique physiologic state of pregnancy places a woman and her fetus at increased risk for infection. This was devastatingly obvious during the H1N1 epidemic of 2009 and was reemphasized during a 2014 outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes. We are reminded again during the largest Ebola virus outbreak in history in West Africa, where women have been disproportionately affected.

No neonates have survived Ebola

Although Ebola infections in the United States have been very few, vigilance for people at risk of infection and preparedness to act in the case of infection are vitally important.

The Ebola virus is thought to be spread to humans through contact with infected fruit bats or primates. Human-to-human transmission occurs through direct contact with blood or body fluids (urine, feces, sweat, saliva, breast milk, vomit, semen) of an infected person or contaminated objects (needles, syringes). The incubation period is 2 to 21 days (average, 8–10 days).