User login

Colorectal cancer screening, 2021: An update

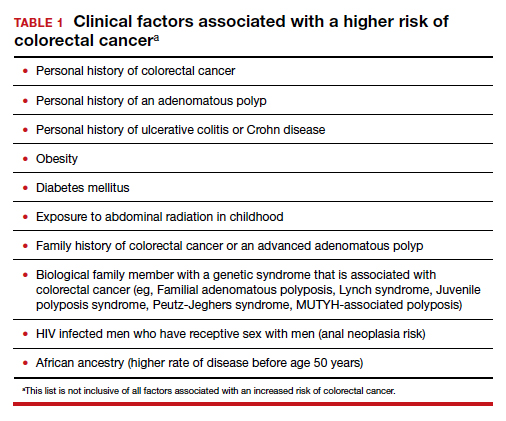

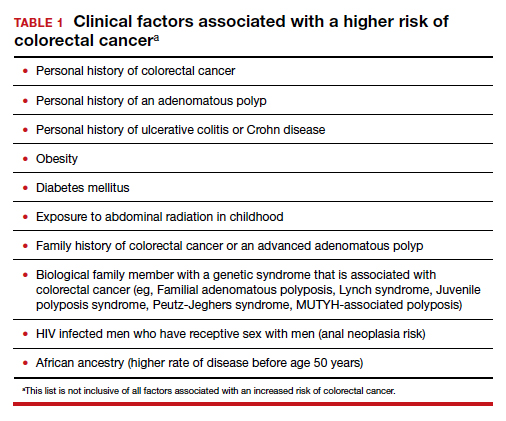

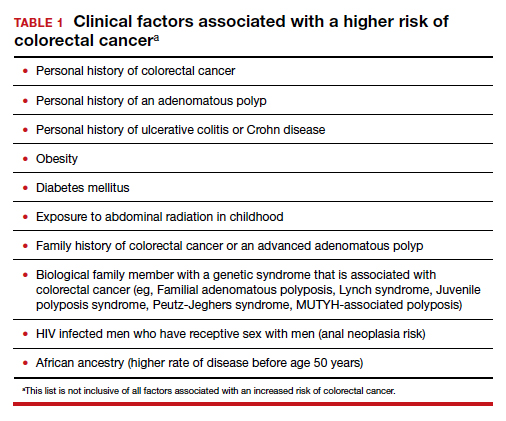

Colorectal cancer is a common disease that has a very lengthy natural history of progression from small (<8 mm) to large (≥8 mm) polyps, then to dysplasia, and eventually to invasive cancer. It is estimated that this progression takes 10 years.1 The long natural history from preneoplasia to cancer makes colorectal cancer an ideal target for screening. Screening for colorectal cancer is divided into two clinical pathways, screening for people at average risk and for those at high risk. Clinical factors that increase the risk of colorectal cancer are listed in TABLE 1. This editorial is focused on the clinical approach to screening for people at average risk for colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death

The top 6 causes of cancer death in the United States are2:

- lung cancer (23% of cancer deaths)

- colon and rectum (9%)

- pancreas (8%)

- female breast (7%)

- prostate (5%)

- liver/bile ducts (5%).

In 2020 it is estimated that 147,950 people were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, including 17,930 people less than 50 years of age.3 In 2020, it is also estimated that 53,200 people in the United States died of colorectal cancer, including 3,640 people younger than age 50.3 By contrast, the American Cancer Society estimates that, in 2021, cervical cancer will be diagnosed in 14,480 women and 4,290 women with the disease will die.4

According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study, among people 50 to 64 years of age, 63% report being up to date with colorectal cancer screening—leaving a full one-third not up to date with their screening.5 Among people aged 65 to 75, 79% report being up to date with colorectal cancer screening. Among those aged 50 to 64, those with health insurance were more likely to be up to date with screening than people without insurance—67% versus 33%, respectively. People with a household income greater than $75,000 and less than $35,000 reported up-to-date screening rates of 71% and 55%, respectively. Among people aged 50 to 64, non-Hispanic White and Black people reported similar rates of being up to date with colorectal screening (66% and 65%, respectively). Hispanic people, however, reported a significantly lower rate of being up to date with colorectal cancer screening (51%).5

A weakness of this CDC study is that the response rate from the surveyed population was less than 50%, raising questions about validity and generalizability of the reported results. Of note, other studies report that Black men may have lower rates of colorectal cancer screening than non-Black men.6 These data show that focused interventions to improve colorectal cancer screening are required for people 50 to 64 years of age, particularly among underinsured and some minority populations.

Continue to: Inequitable health outcomes for colorectal cancer...

Inequitable health outcomes for colorectal cancer

The purpose of screening for cancer is to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) national reporting system, from 2014 to 2018 colorectal death rates per 100,000 adults were 18 for Black adults; 15.1 for American Indian/Alaska native adults; 13.6 for White non-Hispanic adults; 10.9 for White, Hispanic adults; and 9.4 for Asian/Pacific Islander adults.7 Lack of access to and a lower utilization rate of high-quality colon cancer screening modalities, for example colonoscopy, and a lower rate of optimal colon cancer treatment may account for the higher colorectal death rate among Black adults.8,9

Colorectal cancer screening should begin at age 45

In 2015 the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) published data showing that the benefit of initiating screening for colorectal cancer at 45 years of age outweighed the additional cost.10 In 2018, the American Cancer Society recommended that screening for colorectal cancer should begin at age 45.11 In 2021, after resisting the change for many years, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also recommended that screening for colorectal cancer should begin at 45.7 The new recommendation is based on statistical models that showed a significant increase in life-years gained at a small incremental cost. The USPSTF also recommended that clinicians and patients could consider discontinuing colorectal cancer screening at 75 years of age because the net benefit of continuing screening after age 75 is minimal.

Prior to 2021 the USPSTF recommended that screening be initiated at age 50. However, from 2010 to 2020 there was a significant increase in the percentage of new cases of colorectal cancer detected in people younger than 50. In 2010, colon and rectal cancer among people under 50 years of age accounted for 5% and 9% of all cases, respectively.12 In 2020, colon and rectal cancer in people younger than age 50 accounted for 11% and 15% of all cases, respectively.3

Options for colon cancer screening

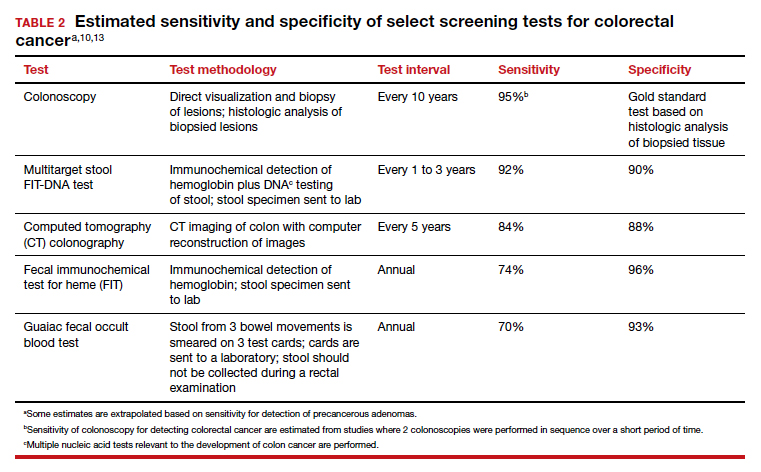

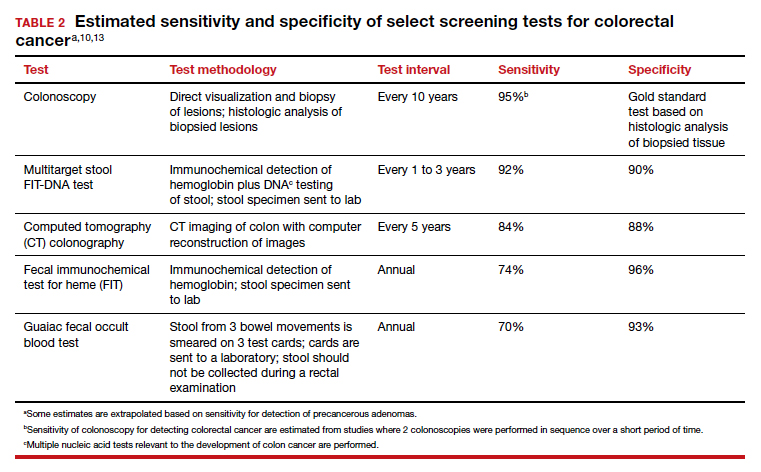

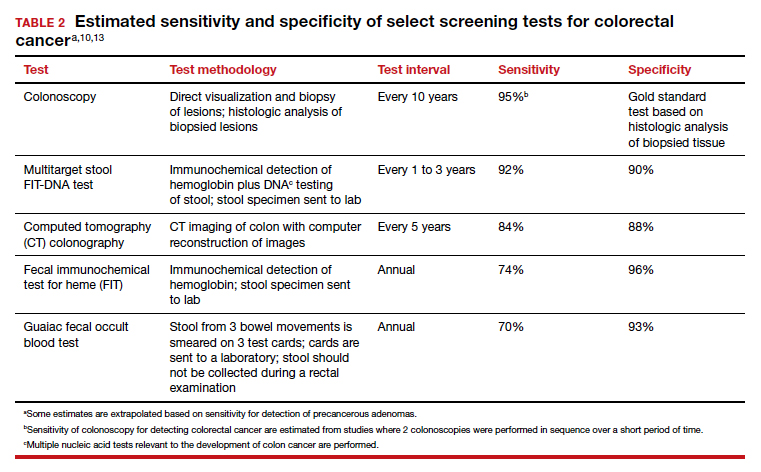

There are many options for colorectal cancer screening (TABLE 2).10,13 Experts conclude that the best colorectal cancer screening test is the test that the patient will complete. Among options for screening, colonoscopy and the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard) have greater sensitivity for detecting colorectal precancer and cancer lesions compared with fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), computed tomography colonography imaging (CTC), and stool guaiac testing (see TABLE 1).

In my practice, I suggest patients use either colonoscopy (every 10 years) or the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (every 1 to 3 years) for screening. Most of my patients select colonoscopy, but some prefer the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test because they fear the pre-colonoscopy bowel preparation and the risk of bowel perforation with colonoscopy. Most colonoscopy procedures are performed with sedation, requiring an adult to take responsibility for transporting the patient to their residence, adding complexity to the performance of colonoscopy. These two tests are discussed in more detail below.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy occupies a unique position among the options for colorectal cancer screening because it is both a screening test and the gold standard for diagnosis, based on histologic analysis of the polypoid tissue biopsied at the time of colonoscopy. For all other screening tests, if the test yields an abnormal result, it is necessary to perform a colonoscopy. Colonoscopy screening offers the advantage of “one and done for 10 years.” In my practice it is much easier to manage a test that is performed every 10 years than a test that should be performed annually.

Colonoscopy also accounts for most of the harms of colorectal screening because of serious procedure complications, including bowel perforation (1 in 2,000 cases) and major bleeding (1 in 500 cases).7

Continue to: Multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard)...

Multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard)

The multitarget stool FIT-DNA test is a remarkable innovation in cancer screening combining 3 independent biomarkers associated with precancerous lesions and colorectal cancer.14 The 3 test components include14:

- a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for hemoglobin (which uses antibodies to detect hemoglobin)

- a test for epigenetic changes in the methylation pattern of promoter DNA, including the promoter regions on the N-Myc Downstream-Regulated Gene 4 (NDRG4) and Bone Morphogenetic Protein 3 (BMP3) genes

- a test for 7 gene mutations in the V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS).

In addition, the amount of the beta-actin DNA present in the stool specimen is assessed and used as a quantitative control for the total amount of DNA in the specimen.

In one large clinical study, 9,989 people at average risk for colorectal cancer were screened with both a multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and a stool FIT test.15 Positive test results triggered a referral for colonoscopy. Among this cohort, 1% of participants were diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 7.6% with a precancerous lesion. The sensitivity of the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and the FIT test for detecting colorectal cancer was 92.3% and 73.8%, respectively. The sensitivities of the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and the FIT test for detecting precancerous lesions were 42.4% and 23.8%, respectively. The specificity of the FIT-DNA and FIT tests for detecting any cancer or precancerous lesion was 90% and 96.4%, respectively.15 The FIT test is less expensive than the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test. Eligible patients can order the FIT test through a Quest website.16 In June 2021 the published cost was $89 for the test plus a $6 physician fee. Most insurers will reimburse the expense of the test for eligible patients.

The multitarget stool FIT-DNA test should be performed every 1 to 3 years. Unlike colonoscopy or CT colonography, the stool is collected at home and sent to a testing laboratory, saving the patient time and travel costs. A disadvantage of the test is that it is more expensive than FIT or guaiac testing. Eligible patients can request a test kit by completing a telemedicine visit through the Cologuard website.17 One website lists the cost of a Cologuard test at $599.18 This test is eligible for reimbursement by most insurers.

Ensure patients are informed of needed screening

Most obstetrician-gynecologists have many women in their practice who are aged 45 to 64, a key target group for colorectal cancer screening. The American Cancer Society and the USPSTF strongly recommend that people in this age range be screened for colorectal cancer. Given that one-third of people these ages have not been screened, obstetrician-gynecologists can play an important role in reducing the health burden of the second most common cause of cancer death by ensuring that their patients are up to date with colorectal screening. ●

- Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening, clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. An update on cancer deaths in the United States. Accessed July 14, 2021.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145-164. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601.

- American Cancer Society website. Key statistics for cervical cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed July 14, 2021.

- Joseph DA, King JB, Dowling NF, et al. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use, United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:253-259.

- Rogers CR, Matthews P, Xu L, et al. Interventions for increasing colorectal cancer screening uptake among African-American men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238354.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238.

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:354-367. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029.

- Rutter CM, Knudsen AB, Lin JS, et al. Black and White differences in colorectal cancer screening and screening outcomes: a narrative review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:3-12. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1537.

- Zauber A, Knudsen A, Rutter CM, et al; Writing Committee of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) Colorectal Cancer Working Group. Evaluating the benefits and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: a collaborative modeling approach. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05203-EF-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2015. file:///C:/Users/loconnor/Downloads/cisnet-draft-modeling-report.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- American Cancer Society website. Cancer screening guidelines by age. . Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17-22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756.

- Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2595. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828.

- FDA summary of safety and effectiveness data. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/P130017B.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Mulitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1287-1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194.

- FIT colorectal cancer screening. Quest Diagnostics website. https://questdirect.questdiagnostics.com/products/fit-colorectal-cancer-screening/d41c67cb-a16d-4ad6-82b9-1a77d32daf41?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=71700000081635378&utm_content=58700006943838348&utm_term=p62498361603&gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgZLq9NOI8QIVufvjBx0slQWPEAAYAiAAEgKHqfD_BwE. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Request Cologuard without leaving your home. Cologuard website. https://www.cologuard.com/how-to-get-cologuard?gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgZLq9NOI8QIVufvjBx0slQWPEAAYASAAEgKHIfD_BwE. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Cologuard. Colonoscopy Assist website. https: //colonoscopyassist.com/Cologuard.html. Accessed July 15, 2021.

Colorectal cancer is a common disease that has a very lengthy natural history of progression from small (<8 mm) to large (≥8 mm) polyps, then to dysplasia, and eventually to invasive cancer. It is estimated that this progression takes 10 years.1 The long natural history from preneoplasia to cancer makes colorectal cancer an ideal target for screening. Screening for colorectal cancer is divided into two clinical pathways, screening for people at average risk and for those at high risk. Clinical factors that increase the risk of colorectal cancer are listed in TABLE 1. This editorial is focused on the clinical approach to screening for people at average risk for colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death

The top 6 causes of cancer death in the United States are2:

- lung cancer (23% of cancer deaths)

- colon and rectum (9%)

- pancreas (8%)

- female breast (7%)

- prostate (5%)

- liver/bile ducts (5%).

In 2020 it is estimated that 147,950 people were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, including 17,930 people less than 50 years of age.3 In 2020, it is also estimated that 53,200 people in the United States died of colorectal cancer, including 3,640 people younger than age 50.3 By contrast, the American Cancer Society estimates that, in 2021, cervical cancer will be diagnosed in 14,480 women and 4,290 women with the disease will die.4

According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study, among people 50 to 64 years of age, 63% report being up to date with colorectal cancer screening—leaving a full one-third not up to date with their screening.5 Among people aged 65 to 75, 79% report being up to date with colorectal cancer screening. Among those aged 50 to 64, those with health insurance were more likely to be up to date with screening than people without insurance—67% versus 33%, respectively. People with a household income greater than $75,000 and less than $35,000 reported up-to-date screening rates of 71% and 55%, respectively. Among people aged 50 to 64, non-Hispanic White and Black people reported similar rates of being up to date with colorectal screening (66% and 65%, respectively). Hispanic people, however, reported a significantly lower rate of being up to date with colorectal cancer screening (51%).5

A weakness of this CDC study is that the response rate from the surveyed population was less than 50%, raising questions about validity and generalizability of the reported results. Of note, other studies report that Black men may have lower rates of colorectal cancer screening than non-Black men.6 These data show that focused interventions to improve colorectal cancer screening are required for people 50 to 64 years of age, particularly among underinsured and some minority populations.

Continue to: Inequitable health outcomes for colorectal cancer...

Inequitable health outcomes for colorectal cancer

The purpose of screening for cancer is to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) national reporting system, from 2014 to 2018 colorectal death rates per 100,000 adults were 18 for Black adults; 15.1 for American Indian/Alaska native adults; 13.6 for White non-Hispanic adults; 10.9 for White, Hispanic adults; and 9.4 for Asian/Pacific Islander adults.7 Lack of access to and a lower utilization rate of high-quality colon cancer screening modalities, for example colonoscopy, and a lower rate of optimal colon cancer treatment may account for the higher colorectal death rate among Black adults.8,9

Colorectal cancer screening should begin at age 45

In 2015 the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) published data showing that the benefit of initiating screening for colorectal cancer at 45 years of age outweighed the additional cost.10 In 2018, the American Cancer Society recommended that screening for colorectal cancer should begin at age 45.11 In 2021, after resisting the change for many years, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also recommended that screening for colorectal cancer should begin at 45.7 The new recommendation is based on statistical models that showed a significant increase in life-years gained at a small incremental cost. The USPSTF also recommended that clinicians and patients could consider discontinuing colorectal cancer screening at 75 years of age because the net benefit of continuing screening after age 75 is minimal.

Prior to 2021 the USPSTF recommended that screening be initiated at age 50. However, from 2010 to 2020 there was a significant increase in the percentage of new cases of colorectal cancer detected in people younger than 50. In 2010, colon and rectal cancer among people under 50 years of age accounted for 5% and 9% of all cases, respectively.12 In 2020, colon and rectal cancer in people younger than age 50 accounted for 11% and 15% of all cases, respectively.3

Options for colon cancer screening

There are many options for colorectal cancer screening (TABLE 2).10,13 Experts conclude that the best colorectal cancer screening test is the test that the patient will complete. Among options for screening, colonoscopy and the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard) have greater sensitivity for detecting colorectal precancer and cancer lesions compared with fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), computed tomography colonography imaging (CTC), and stool guaiac testing (see TABLE 1).

In my practice, I suggest patients use either colonoscopy (every 10 years) or the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (every 1 to 3 years) for screening. Most of my patients select colonoscopy, but some prefer the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test because they fear the pre-colonoscopy bowel preparation and the risk of bowel perforation with colonoscopy. Most colonoscopy procedures are performed with sedation, requiring an adult to take responsibility for transporting the patient to their residence, adding complexity to the performance of colonoscopy. These two tests are discussed in more detail below.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy occupies a unique position among the options for colorectal cancer screening because it is both a screening test and the gold standard for diagnosis, based on histologic analysis of the polypoid tissue biopsied at the time of colonoscopy. For all other screening tests, if the test yields an abnormal result, it is necessary to perform a colonoscopy. Colonoscopy screening offers the advantage of “one and done for 10 years.” In my practice it is much easier to manage a test that is performed every 10 years than a test that should be performed annually.

Colonoscopy also accounts for most of the harms of colorectal screening because of serious procedure complications, including bowel perforation (1 in 2,000 cases) and major bleeding (1 in 500 cases).7

Continue to: Multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard)...

Multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard)

The multitarget stool FIT-DNA test is a remarkable innovation in cancer screening combining 3 independent biomarkers associated with precancerous lesions and colorectal cancer.14 The 3 test components include14:

- a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for hemoglobin (which uses antibodies to detect hemoglobin)

- a test for epigenetic changes in the methylation pattern of promoter DNA, including the promoter regions on the N-Myc Downstream-Regulated Gene 4 (NDRG4) and Bone Morphogenetic Protein 3 (BMP3) genes

- a test for 7 gene mutations in the V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS).

In addition, the amount of the beta-actin DNA present in the stool specimen is assessed and used as a quantitative control for the total amount of DNA in the specimen.

In one large clinical study, 9,989 people at average risk for colorectal cancer were screened with both a multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and a stool FIT test.15 Positive test results triggered a referral for colonoscopy. Among this cohort, 1% of participants were diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 7.6% with a precancerous lesion. The sensitivity of the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and the FIT test for detecting colorectal cancer was 92.3% and 73.8%, respectively. The sensitivities of the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and the FIT test for detecting precancerous lesions were 42.4% and 23.8%, respectively. The specificity of the FIT-DNA and FIT tests for detecting any cancer or precancerous lesion was 90% and 96.4%, respectively.15 The FIT test is less expensive than the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test. Eligible patients can order the FIT test through a Quest website.16 In June 2021 the published cost was $89 for the test plus a $6 physician fee. Most insurers will reimburse the expense of the test for eligible patients.

The multitarget stool FIT-DNA test should be performed every 1 to 3 years. Unlike colonoscopy or CT colonography, the stool is collected at home and sent to a testing laboratory, saving the patient time and travel costs. A disadvantage of the test is that it is more expensive than FIT or guaiac testing. Eligible patients can request a test kit by completing a telemedicine visit through the Cologuard website.17 One website lists the cost of a Cologuard test at $599.18 This test is eligible for reimbursement by most insurers.

Ensure patients are informed of needed screening

Most obstetrician-gynecologists have many women in their practice who are aged 45 to 64, a key target group for colorectal cancer screening. The American Cancer Society and the USPSTF strongly recommend that people in this age range be screened for colorectal cancer. Given that one-third of people these ages have not been screened, obstetrician-gynecologists can play an important role in reducing the health burden of the second most common cause of cancer death by ensuring that their patients are up to date with colorectal screening. ●

Colorectal cancer is a common disease that has a very lengthy natural history of progression from small (<8 mm) to large (≥8 mm) polyps, then to dysplasia, and eventually to invasive cancer. It is estimated that this progression takes 10 years.1 The long natural history from preneoplasia to cancer makes colorectal cancer an ideal target for screening. Screening for colorectal cancer is divided into two clinical pathways, screening for people at average risk and for those at high risk. Clinical factors that increase the risk of colorectal cancer are listed in TABLE 1. This editorial is focused on the clinical approach to screening for people at average risk for colorectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death

The top 6 causes of cancer death in the United States are2:

- lung cancer (23% of cancer deaths)

- colon and rectum (9%)

- pancreas (8%)

- female breast (7%)

- prostate (5%)

- liver/bile ducts (5%).

In 2020 it is estimated that 147,950 people were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, including 17,930 people less than 50 years of age.3 In 2020, it is also estimated that 53,200 people in the United States died of colorectal cancer, including 3,640 people younger than age 50.3 By contrast, the American Cancer Society estimates that, in 2021, cervical cancer will be diagnosed in 14,480 women and 4,290 women with the disease will die.4

According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study, among people 50 to 64 years of age, 63% report being up to date with colorectal cancer screening—leaving a full one-third not up to date with their screening.5 Among people aged 65 to 75, 79% report being up to date with colorectal cancer screening. Among those aged 50 to 64, those with health insurance were more likely to be up to date with screening than people without insurance—67% versus 33%, respectively. People with a household income greater than $75,000 and less than $35,000 reported up-to-date screening rates of 71% and 55%, respectively. Among people aged 50 to 64, non-Hispanic White and Black people reported similar rates of being up to date with colorectal screening (66% and 65%, respectively). Hispanic people, however, reported a significantly lower rate of being up to date with colorectal cancer screening (51%).5

A weakness of this CDC study is that the response rate from the surveyed population was less than 50%, raising questions about validity and generalizability of the reported results. Of note, other studies report that Black men may have lower rates of colorectal cancer screening than non-Black men.6 These data show that focused interventions to improve colorectal cancer screening are required for people 50 to 64 years of age, particularly among underinsured and some minority populations.

Continue to: Inequitable health outcomes for colorectal cancer...

Inequitable health outcomes for colorectal cancer

The purpose of screening for cancer is to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) national reporting system, from 2014 to 2018 colorectal death rates per 100,000 adults were 18 for Black adults; 15.1 for American Indian/Alaska native adults; 13.6 for White non-Hispanic adults; 10.9 for White, Hispanic adults; and 9.4 for Asian/Pacific Islander adults.7 Lack of access to and a lower utilization rate of high-quality colon cancer screening modalities, for example colonoscopy, and a lower rate of optimal colon cancer treatment may account for the higher colorectal death rate among Black adults.8,9

Colorectal cancer screening should begin at age 45

In 2015 the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) published data showing that the benefit of initiating screening for colorectal cancer at 45 years of age outweighed the additional cost.10 In 2018, the American Cancer Society recommended that screening for colorectal cancer should begin at age 45.11 In 2021, after resisting the change for many years, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) also recommended that screening for colorectal cancer should begin at 45.7 The new recommendation is based on statistical models that showed a significant increase in life-years gained at a small incremental cost. The USPSTF also recommended that clinicians and patients could consider discontinuing colorectal cancer screening at 75 years of age because the net benefit of continuing screening after age 75 is minimal.

Prior to 2021 the USPSTF recommended that screening be initiated at age 50. However, from 2010 to 2020 there was a significant increase in the percentage of new cases of colorectal cancer detected in people younger than 50. In 2010, colon and rectal cancer among people under 50 years of age accounted for 5% and 9% of all cases, respectively.12 In 2020, colon and rectal cancer in people younger than age 50 accounted for 11% and 15% of all cases, respectively.3

Options for colon cancer screening

There are many options for colorectal cancer screening (TABLE 2).10,13 Experts conclude that the best colorectal cancer screening test is the test that the patient will complete. Among options for screening, colonoscopy and the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard) have greater sensitivity for detecting colorectal precancer and cancer lesions compared with fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), computed tomography colonography imaging (CTC), and stool guaiac testing (see TABLE 1).

In my practice, I suggest patients use either colonoscopy (every 10 years) or the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (every 1 to 3 years) for screening. Most of my patients select colonoscopy, but some prefer the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test because they fear the pre-colonoscopy bowel preparation and the risk of bowel perforation with colonoscopy. Most colonoscopy procedures are performed with sedation, requiring an adult to take responsibility for transporting the patient to their residence, adding complexity to the performance of colonoscopy. These two tests are discussed in more detail below.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy occupies a unique position among the options for colorectal cancer screening because it is both a screening test and the gold standard for diagnosis, based on histologic analysis of the polypoid tissue biopsied at the time of colonoscopy. For all other screening tests, if the test yields an abnormal result, it is necessary to perform a colonoscopy. Colonoscopy screening offers the advantage of “one and done for 10 years.” In my practice it is much easier to manage a test that is performed every 10 years than a test that should be performed annually.

Colonoscopy also accounts for most of the harms of colorectal screening because of serious procedure complications, including bowel perforation (1 in 2,000 cases) and major bleeding (1 in 500 cases).7

Continue to: Multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard)...

Multitarget stool FIT-DNA test (Cologuard)

The multitarget stool FIT-DNA test is a remarkable innovation in cancer screening combining 3 independent biomarkers associated with precancerous lesions and colorectal cancer.14 The 3 test components include14:

- a fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for hemoglobin (which uses antibodies to detect hemoglobin)

- a test for epigenetic changes in the methylation pattern of promoter DNA, including the promoter regions on the N-Myc Downstream-Regulated Gene 4 (NDRG4) and Bone Morphogenetic Protein 3 (BMP3) genes

- a test for 7 gene mutations in the V-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS).

In addition, the amount of the beta-actin DNA present in the stool specimen is assessed and used as a quantitative control for the total amount of DNA in the specimen.

In one large clinical study, 9,989 people at average risk for colorectal cancer were screened with both a multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and a stool FIT test.15 Positive test results triggered a referral for colonoscopy. Among this cohort, 1% of participants were diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 7.6% with a precancerous lesion. The sensitivity of the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and the FIT test for detecting colorectal cancer was 92.3% and 73.8%, respectively. The sensitivities of the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test and the FIT test for detecting precancerous lesions were 42.4% and 23.8%, respectively. The specificity of the FIT-DNA and FIT tests for detecting any cancer or precancerous lesion was 90% and 96.4%, respectively.15 The FIT test is less expensive than the multitarget stool FIT-DNA test. Eligible patients can order the FIT test through a Quest website.16 In June 2021 the published cost was $89 for the test plus a $6 physician fee. Most insurers will reimburse the expense of the test for eligible patients.

The multitarget stool FIT-DNA test should be performed every 1 to 3 years. Unlike colonoscopy or CT colonography, the stool is collected at home and sent to a testing laboratory, saving the patient time and travel costs. A disadvantage of the test is that it is more expensive than FIT or guaiac testing. Eligible patients can request a test kit by completing a telemedicine visit through the Cologuard website.17 One website lists the cost of a Cologuard test at $599.18 This test is eligible for reimbursement by most insurers.

Ensure patients are informed of needed screening

Most obstetrician-gynecologists have many women in their practice who are aged 45 to 64, a key target group for colorectal cancer screening. The American Cancer Society and the USPSTF strongly recommend that people in this age range be screened for colorectal cancer. Given that one-third of people these ages have not been screened, obstetrician-gynecologists can play an important role in reducing the health burden of the second most common cause of cancer death by ensuring that their patients are up to date with colorectal screening. ●

- Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening, clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. An update on cancer deaths in the United States. Accessed July 14, 2021.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145-164. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601.

- American Cancer Society website. Key statistics for cervical cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed July 14, 2021.

- Joseph DA, King JB, Dowling NF, et al. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use, United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:253-259.

- Rogers CR, Matthews P, Xu L, et al. Interventions for increasing colorectal cancer screening uptake among African-American men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238354.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238.

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:354-367. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029.

- Rutter CM, Knudsen AB, Lin JS, et al. Black and White differences in colorectal cancer screening and screening outcomes: a narrative review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:3-12. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1537.

- Zauber A, Knudsen A, Rutter CM, et al; Writing Committee of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) Colorectal Cancer Working Group. Evaluating the benefits and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: a collaborative modeling approach. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05203-EF-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2015. file:///C:/Users/loconnor/Downloads/cisnet-draft-modeling-report.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- American Cancer Society website. Cancer screening guidelines by age. . Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17-22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756.

- Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2595. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828.

- FDA summary of safety and effectiveness data. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/P130017B.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Mulitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1287-1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194.

- FIT colorectal cancer screening. Quest Diagnostics website. https://questdirect.questdiagnostics.com/products/fit-colorectal-cancer-screening/d41c67cb-a16d-4ad6-82b9-1a77d32daf41?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=71700000081635378&utm_content=58700006943838348&utm_term=p62498361603&gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgZLq9NOI8QIVufvjBx0slQWPEAAYAiAAEgKHqfD_BwE. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Request Cologuard without leaving your home. Cologuard website. https://www.cologuard.com/how-to-get-cologuard?gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgZLq9NOI8QIVufvjBx0slQWPEAAYASAAEgKHIfD_BwE. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Cologuard. Colonoscopy Assist website. https: //colonoscopyassist.com/Cologuard.html. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al. Colorectal cancer screening, clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.agast970594.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. An update on cancer deaths in the United States. Accessed July 14, 2021.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145-164. doi: 10.3322/caac.21601.

- American Cancer Society website. Key statistics for cervical cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed July 14, 2021.

- Joseph DA, King JB, Dowling NF, et al. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening test use, United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:253-259.

- Rogers CR, Matthews P, Xu L, et al. Interventions for increasing colorectal cancer screening uptake among African-American men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0238354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238354.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238.

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:354-367. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029.

- Rutter CM, Knudsen AB, Lin JS, et al. Black and White differences in colorectal cancer screening and screening outcomes: a narrative review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:3-12. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1537.

- Zauber A, Knudsen A, Rutter CM, et al; Writing Committee of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) Colorectal Cancer Working Group. Evaluating the benefits and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: a collaborative modeling approach. AHRQ Publication No. 14-05203-EF-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2015. file:///C:/Users/loconnor/Downloads/cisnet-draft-modeling-report.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- American Cancer Society website. Cancer screening guidelines by age. . Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17-22. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756.

- Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2595. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828.

- FDA summary of safety and effectiveness data. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf13/P130017B.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Mulitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1287-1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311194.

- FIT colorectal cancer screening. Quest Diagnostics website. https://questdirect.questdiagnostics.com/products/fit-colorectal-cancer-screening/d41c67cb-a16d-4ad6-82b9-1a77d32daf41?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=71700000081635378&utm_content=58700006943838348&utm_term=p62498361603&gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgZLq9NOI8QIVufvjBx0slQWPEAAYAiAAEgKHqfD_BwE. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Request Cologuard without leaving your home. Cologuard website. https://www.cologuard.com/how-to-get-cologuard?gclsrc=aw.ds&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIgZLq9NOI8QIVufvjBx0slQWPEAAYASAAEgKHIfD_BwE. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- Cologuard. Colonoscopy Assist website. https: //colonoscopyassist.com/Cologuard.html. Accessed July 15, 2021.

One center’s experience delivering monochorionic twins

Between 2005 and 2021, mode of delivery of diamniotic twins at this practice did not significantly differ by chorionicity, researchers affiliated with Maternal Fetal Medicine Associates and the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study supports a recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that vaginal delivery “is a reasonable option in well selected diamniotic twin pregnancies, irrespective of chorionicity, and should be considered, provided that an experienced obstetrician is available,” said Iris Krishna, MD, assistant professor of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

The experience at this practice, however, may not apply to many practices in the United States, said Dr. Krishna, who was not involved in the study.

Of 1,121 diamniotic twin pregnancies included in the analysis, 202 (18%) were monochorionic. The cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different between groups: 61% for monochorionic and 63% for dichorionic pregnancies.

Among women with planned vaginal delivery (101 monochorionic pregnancies and 422 dichorionic pregnancies), the cesarean delivery rate likewise did not significantly differ by chorionicity. Twenty-two percent of the monochorionic pregnancies and 21% of the dichorionic pregnancies in this subgroup had a cesarean delivery.

Among patients with a vaginal delivery of twin A, chorionicity was not associated with mode of delivery for twin B. Combined vaginal-cesarean deliveries occurred less than 1% of the time, and breech extraction of twin B occurred approximately 75% of the time, regardless of chorionicity.

The researchers also compared neonatal outcomes for monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancies at or after 34 weeks of gestation, based on the intended mode of delivery (95 women with planned vaginal delivery and 68 with planned cesarean delivery). Neonatal outcomes generally were similar, although the incidence of mechanical ventilation was less common in cases with planned vaginal delivery (7% vs. 21%).

“Our data affirm that an attempt at a vaginal birth for twin pregnancies, without contraindications to vaginal delivery and regardless of chorionicity, is reasonable and achievable,” wrote study author Henry N. Lesser, MD, with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore, and colleagues.

The patients with planned cesarean delivery had a contraindication to vaginal delivery or otherwise chose to have a cesarean delivery. The researchers excluded from their analysis pregnancies with intrauterine fetal demise of either twin before labor or planned cesarean delivery.

The study’s reliance on data from a single practice decreases its external validity, the researchers noted. Induction of labor at this center typically occurs at 37 weeks’ gestation for monochorionic twins and at 38 weeks for dichorionic twins, and “senior personnel experienced in intrauterine twin manipulation are always present at delivery,” the study authors said.

The study describes “the experience of a single site with skilled obstetricians following a standardized approach to management of diamniotic twin deliveries,” Dr. Krishna said. “Findings may not be generalizable to many U.S. practices as obstetrics and gynecology residents often lack training in breech extraction or internal podalic version of the second twin. This underscores the importance of a concerted effort by skilled senior physicians to train junior physicians in vaginal delivery of the second twin to improve overall outcomes amongst women with diamniotic twin gestations.”

Michael F. Greene, MD, professor emeritus of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, agreed that the findings are not generalizable to the national population. Approximately 10% of the patients in the study had prepregnancy obesity, whereas doctors practicing in other areas likely encounter higher rates, Dr. Greene said in an interview.

He also wondered about other data points that could be of interest but were not reported, such as the racial or ethnic distribution of the patients, rates of birth defects, the use of instruments to aid delivery, and neonatal outcomes for the dichorionic twins.

Monochorionic pregnancies entail a risk of twin-twin transfusion syndrome and other complications, including an increased likelihood of birth defects.

Dr. Greene is an associate editor with the New England Journal of Medicine, which in 2013 published results from the Twin Birth Study, an international trial where women with dichorionic or monochorionic twins were randomly assigned to planned vaginal delivery or planned cesarean delivery. Outcomes did not significantly differ between groups. In the trial, the rate of cesarean delivery in the group with planned vaginal delivery was 43.8%, and Dr. Greene discussed the implications of the study in an accompanying editorial.

Since then, the obstetrics and gynecology community “has been focusing in recent years on trying to avoid the first cesarean section” when it is safe to do so, Dr. Greene said. “That has become almost a bumper sticker in modern obstetrics.”

And patients should know that it is an option, Dr. Krishna added.

“Women with monochorionic-diamniotic twins should be counseled that with an experienced obstetrician that an attempt at vaginal delivery is not associated with adverse neonatal outcomes when compared with planned cesarean delivery,” Dr. Krishna said.

A study coauthor disclosed serving on the speakers bureau for Natera and Hologic. Dr. Krishna is a member of the editorial advisory board for Ob.Gyn. News.

Between 2005 and 2021, mode of delivery of diamniotic twins at this practice did not significantly differ by chorionicity, researchers affiliated with Maternal Fetal Medicine Associates and the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study supports a recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that vaginal delivery “is a reasonable option in well selected diamniotic twin pregnancies, irrespective of chorionicity, and should be considered, provided that an experienced obstetrician is available,” said Iris Krishna, MD, assistant professor of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

The experience at this practice, however, may not apply to many practices in the United States, said Dr. Krishna, who was not involved in the study.

Of 1,121 diamniotic twin pregnancies included in the analysis, 202 (18%) were monochorionic. The cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different between groups: 61% for monochorionic and 63% for dichorionic pregnancies.

Among women with planned vaginal delivery (101 monochorionic pregnancies and 422 dichorionic pregnancies), the cesarean delivery rate likewise did not significantly differ by chorionicity. Twenty-two percent of the monochorionic pregnancies and 21% of the dichorionic pregnancies in this subgroup had a cesarean delivery.

Among patients with a vaginal delivery of twin A, chorionicity was not associated with mode of delivery for twin B. Combined vaginal-cesarean deliveries occurred less than 1% of the time, and breech extraction of twin B occurred approximately 75% of the time, regardless of chorionicity.

The researchers also compared neonatal outcomes for monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancies at or after 34 weeks of gestation, based on the intended mode of delivery (95 women with planned vaginal delivery and 68 with planned cesarean delivery). Neonatal outcomes generally were similar, although the incidence of mechanical ventilation was less common in cases with planned vaginal delivery (7% vs. 21%).

“Our data affirm that an attempt at a vaginal birth for twin pregnancies, without contraindications to vaginal delivery and regardless of chorionicity, is reasonable and achievable,” wrote study author Henry N. Lesser, MD, with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore, and colleagues.

The patients with planned cesarean delivery had a contraindication to vaginal delivery or otherwise chose to have a cesarean delivery. The researchers excluded from their analysis pregnancies with intrauterine fetal demise of either twin before labor or planned cesarean delivery.

The study’s reliance on data from a single practice decreases its external validity, the researchers noted. Induction of labor at this center typically occurs at 37 weeks’ gestation for monochorionic twins and at 38 weeks for dichorionic twins, and “senior personnel experienced in intrauterine twin manipulation are always present at delivery,” the study authors said.

The study describes “the experience of a single site with skilled obstetricians following a standardized approach to management of diamniotic twin deliveries,” Dr. Krishna said. “Findings may not be generalizable to many U.S. practices as obstetrics and gynecology residents often lack training in breech extraction or internal podalic version of the second twin. This underscores the importance of a concerted effort by skilled senior physicians to train junior physicians in vaginal delivery of the second twin to improve overall outcomes amongst women with diamniotic twin gestations.”

Michael F. Greene, MD, professor emeritus of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, agreed that the findings are not generalizable to the national population. Approximately 10% of the patients in the study had prepregnancy obesity, whereas doctors practicing in other areas likely encounter higher rates, Dr. Greene said in an interview.

He also wondered about other data points that could be of interest but were not reported, such as the racial or ethnic distribution of the patients, rates of birth defects, the use of instruments to aid delivery, and neonatal outcomes for the dichorionic twins.

Monochorionic pregnancies entail a risk of twin-twin transfusion syndrome and other complications, including an increased likelihood of birth defects.

Dr. Greene is an associate editor with the New England Journal of Medicine, which in 2013 published results from the Twin Birth Study, an international trial where women with dichorionic or monochorionic twins were randomly assigned to planned vaginal delivery or planned cesarean delivery. Outcomes did not significantly differ between groups. In the trial, the rate of cesarean delivery in the group with planned vaginal delivery was 43.8%, and Dr. Greene discussed the implications of the study in an accompanying editorial.

Since then, the obstetrics and gynecology community “has been focusing in recent years on trying to avoid the first cesarean section” when it is safe to do so, Dr. Greene said. “That has become almost a bumper sticker in modern obstetrics.”

And patients should know that it is an option, Dr. Krishna added.

“Women with monochorionic-diamniotic twins should be counseled that with an experienced obstetrician that an attempt at vaginal delivery is not associated with adverse neonatal outcomes when compared with planned cesarean delivery,” Dr. Krishna said.

A study coauthor disclosed serving on the speakers bureau for Natera and Hologic. Dr. Krishna is a member of the editorial advisory board for Ob.Gyn. News.

Between 2005 and 2021, mode of delivery of diamniotic twins at this practice did not significantly differ by chorionicity, researchers affiliated with Maternal Fetal Medicine Associates and the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive science at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York reported in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study supports a recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that vaginal delivery “is a reasonable option in well selected diamniotic twin pregnancies, irrespective of chorionicity, and should be considered, provided that an experienced obstetrician is available,” said Iris Krishna, MD, assistant professor of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

The experience at this practice, however, may not apply to many practices in the United States, said Dr. Krishna, who was not involved in the study.

Of 1,121 diamniotic twin pregnancies included in the analysis, 202 (18%) were monochorionic. The cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different between groups: 61% for monochorionic and 63% for dichorionic pregnancies.

Among women with planned vaginal delivery (101 monochorionic pregnancies and 422 dichorionic pregnancies), the cesarean delivery rate likewise did not significantly differ by chorionicity. Twenty-two percent of the monochorionic pregnancies and 21% of the dichorionic pregnancies in this subgroup had a cesarean delivery.

Among patients with a vaginal delivery of twin A, chorionicity was not associated with mode of delivery for twin B. Combined vaginal-cesarean deliveries occurred less than 1% of the time, and breech extraction of twin B occurred approximately 75% of the time, regardless of chorionicity.

The researchers also compared neonatal outcomes for monochorionic-diamniotic twin pregnancies at or after 34 weeks of gestation, based on the intended mode of delivery (95 women with planned vaginal delivery and 68 with planned cesarean delivery). Neonatal outcomes generally were similar, although the incidence of mechanical ventilation was less common in cases with planned vaginal delivery (7% vs. 21%).

“Our data affirm that an attempt at a vaginal birth for twin pregnancies, without contraindications to vaginal delivery and regardless of chorionicity, is reasonable and achievable,” wrote study author Henry N. Lesser, MD, with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore, and colleagues.

The patients with planned cesarean delivery had a contraindication to vaginal delivery or otherwise chose to have a cesarean delivery. The researchers excluded from their analysis pregnancies with intrauterine fetal demise of either twin before labor or planned cesarean delivery.

The study’s reliance on data from a single practice decreases its external validity, the researchers noted. Induction of labor at this center typically occurs at 37 weeks’ gestation for monochorionic twins and at 38 weeks for dichorionic twins, and “senior personnel experienced in intrauterine twin manipulation are always present at delivery,” the study authors said.

The study describes “the experience of a single site with skilled obstetricians following a standardized approach to management of diamniotic twin deliveries,” Dr. Krishna said. “Findings may not be generalizable to many U.S. practices as obstetrics and gynecology residents often lack training in breech extraction or internal podalic version of the second twin. This underscores the importance of a concerted effort by skilled senior physicians to train junior physicians in vaginal delivery of the second twin to improve overall outcomes amongst women with diamniotic twin gestations.”

Michael F. Greene, MD, professor emeritus of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, agreed that the findings are not generalizable to the national population. Approximately 10% of the patients in the study had prepregnancy obesity, whereas doctors practicing in other areas likely encounter higher rates, Dr. Greene said in an interview.

He also wondered about other data points that could be of interest but were not reported, such as the racial or ethnic distribution of the patients, rates of birth defects, the use of instruments to aid delivery, and neonatal outcomes for the dichorionic twins.

Monochorionic pregnancies entail a risk of twin-twin transfusion syndrome and other complications, including an increased likelihood of birth defects.

Dr. Greene is an associate editor with the New England Journal of Medicine, which in 2013 published results from the Twin Birth Study, an international trial where women with dichorionic or monochorionic twins were randomly assigned to planned vaginal delivery or planned cesarean delivery. Outcomes did not significantly differ between groups. In the trial, the rate of cesarean delivery in the group with planned vaginal delivery was 43.8%, and Dr. Greene discussed the implications of the study in an accompanying editorial.

Since then, the obstetrics and gynecology community “has been focusing in recent years on trying to avoid the first cesarean section” when it is safe to do so, Dr. Greene said. “That has become almost a bumper sticker in modern obstetrics.”

And patients should know that it is an option, Dr. Krishna added.

“Women with monochorionic-diamniotic twins should be counseled that with an experienced obstetrician that an attempt at vaginal delivery is not associated with adverse neonatal outcomes when compared with planned cesarean delivery,” Dr. Krishna said.

A study coauthor disclosed serving on the speakers bureau for Natera and Hologic. Dr. Krishna is a member of the editorial advisory board for Ob.Gyn. News.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Specific COVID-19 antibodies found in breast milk of vaccinated women

The breast milk of women who had received Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine contained specific antibodies against the infectious disease, new research found.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions among individuals who are breastfeeding, both because of the possibility of viral transmission to infants during breastfeeding and, more recently, of the potential risks and benefits of vaccination in this specific population,” researchers wrote.

In August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and most recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommended that pregnant people receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

The study, published Aug. 11 in JAMA Network Open, adds to a growing collection of research that has found COVID-19 antibodies in the breast milk of women who were vaccinated against or have been infected with the illness.

Study author Erika Esteve-Palau, MD, PhD, and her colleagues collected blood and milk samples from 33 people who were on average 37 years old and who were on average 17.5 months post partum to examine the correlation of the levels of immunoglobulin G antibodies against the spike protein (S1 subunit) and against the nucleocapsid (NC) of SARS-CoV-2.

Blood and milk samples were taken from each study participant at three time points – 2 weeks after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, 2 weeks after receiving the second dose, and 4 weeks after the second dose. No participants had confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection prior to vaccination or during the study period.

Researchers found that, after the second dose of the vaccine, IgG(S1) levels in breast milk increased and were positively associated with corresponding levels in the blood samples. The median range of IgG(S1) levels for serum-milk pairs at each time point were 519 to 1 arbitrary units (AU) per mL 2 weeks after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, 8,644 to 78 AU/mL 2 weeks after receiving the second dose, and 12,478 to 50.4 AU/mL 4 weeks after receiving the second dose.

Lisette D. Tanner, MD, MPH, FACOG, who was not involved in the study, said she was not surprised by the findings as previous studies have shown the passage of antibodies in breast milk in vaccinated women. One 2021 study published in JAMA found SARS-CoV-2–specific IgA and IgG antibodies in breast milk for 6 weeks after vaccination. IgA secretion was evident as early as 2 weeks after vaccination followed by a spike in IgG after 4 weeks (a week after the second vaccine). Meanwhile, another 2021 study published in mBio found that breast milk produced by parents with COVID-19 is a source of SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG antibodies and can neutralize COVID-19 activity.

“While the data from this and other studies is promising in regards to the passage of antibodies, it is currently unclear what the long-term effects for children will be,” said Dr. Tanner of the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, Atlanta. “It is not yet known what level of antibodies is necessary to convey protection to either neonates or children. This is an active area of investigation at multiple institutions.”

Dr. Tanner said she wished the study “evaluated neonatal cord blood or serum levels to better understand the immune response mounted by the children of women who received vaccination.”

Researchers of the current study said larger prospective studies are needed to confirm the safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in individuals who are breastfeeding and further assess the association of vaccination with infants’ health and SARS-CoV-2–specific immunity.

Dr. Palau and Dr. Tanner had no relevant financial disclosures.

The breast milk of women who had received Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine contained specific antibodies against the infectious disease, new research found.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions among individuals who are breastfeeding, both because of the possibility of viral transmission to infants during breastfeeding and, more recently, of the potential risks and benefits of vaccination in this specific population,” researchers wrote.

In August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and most recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommended that pregnant people receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

The study, published Aug. 11 in JAMA Network Open, adds to a growing collection of research that has found COVID-19 antibodies in the breast milk of women who were vaccinated against or have been infected with the illness.

Study author Erika Esteve-Palau, MD, PhD, and her colleagues collected blood and milk samples from 33 people who were on average 37 years old and who were on average 17.5 months post partum to examine the correlation of the levels of immunoglobulin G antibodies against the spike protein (S1 subunit) and against the nucleocapsid (NC) of SARS-CoV-2.

Blood and milk samples were taken from each study participant at three time points – 2 weeks after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, 2 weeks after receiving the second dose, and 4 weeks after the second dose. No participants had confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection prior to vaccination or during the study period.

Researchers found that, after the second dose of the vaccine, IgG(S1) levels in breast milk increased and were positively associated with corresponding levels in the blood samples. The median range of IgG(S1) levels for serum-milk pairs at each time point were 519 to 1 arbitrary units (AU) per mL 2 weeks after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, 8,644 to 78 AU/mL 2 weeks after receiving the second dose, and 12,478 to 50.4 AU/mL 4 weeks after receiving the second dose.

Lisette D. Tanner, MD, MPH, FACOG, who was not involved in the study, said she was not surprised by the findings as previous studies have shown the passage of antibodies in breast milk in vaccinated women. One 2021 study published in JAMA found SARS-CoV-2–specific IgA and IgG antibodies in breast milk for 6 weeks after vaccination. IgA secretion was evident as early as 2 weeks after vaccination followed by a spike in IgG after 4 weeks (a week after the second vaccine). Meanwhile, another 2021 study published in mBio found that breast milk produced by parents with COVID-19 is a source of SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG antibodies and can neutralize COVID-19 activity.

“While the data from this and other studies is promising in regards to the passage of antibodies, it is currently unclear what the long-term effects for children will be,” said Dr. Tanner of the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, Atlanta. “It is not yet known what level of antibodies is necessary to convey protection to either neonates or children. This is an active area of investigation at multiple institutions.”

Dr. Tanner said she wished the study “evaluated neonatal cord blood or serum levels to better understand the immune response mounted by the children of women who received vaccination.”

Researchers of the current study said larger prospective studies are needed to confirm the safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in individuals who are breastfeeding and further assess the association of vaccination with infants’ health and SARS-CoV-2–specific immunity.

Dr. Palau and Dr. Tanner had no relevant financial disclosures.

The breast milk of women who had received Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine contained specific antibodies against the infectious disease, new research found.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has raised questions among individuals who are breastfeeding, both because of the possibility of viral transmission to infants during breastfeeding and, more recently, of the potential risks and benefits of vaccination in this specific population,” researchers wrote.

In August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and most recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recommended that pregnant people receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

The study, published Aug. 11 in JAMA Network Open, adds to a growing collection of research that has found COVID-19 antibodies in the breast milk of women who were vaccinated against or have been infected with the illness.

Study author Erika Esteve-Palau, MD, PhD, and her colleagues collected blood and milk samples from 33 people who were on average 37 years old and who were on average 17.5 months post partum to examine the correlation of the levels of immunoglobulin G antibodies against the spike protein (S1 subunit) and against the nucleocapsid (NC) of SARS-CoV-2.

Blood and milk samples were taken from each study participant at three time points – 2 weeks after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, 2 weeks after receiving the second dose, and 4 weeks after the second dose. No participants had confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection prior to vaccination or during the study period.

Researchers found that, after the second dose of the vaccine, IgG(S1) levels in breast milk increased and were positively associated with corresponding levels in the blood samples. The median range of IgG(S1) levels for serum-milk pairs at each time point were 519 to 1 arbitrary units (AU) per mL 2 weeks after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, 8,644 to 78 AU/mL 2 weeks after receiving the second dose, and 12,478 to 50.4 AU/mL 4 weeks after receiving the second dose.

Lisette D. Tanner, MD, MPH, FACOG, who was not involved in the study, said she was not surprised by the findings as previous studies have shown the passage of antibodies in breast milk in vaccinated women. One 2021 study published in JAMA found SARS-CoV-2–specific IgA and IgG antibodies in breast milk for 6 weeks after vaccination. IgA secretion was evident as early as 2 weeks after vaccination followed by a spike in IgG after 4 weeks (a week after the second vaccine). Meanwhile, another 2021 study published in mBio found that breast milk produced by parents with COVID-19 is a source of SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG antibodies and can neutralize COVID-19 activity.

“While the data from this and other studies is promising in regards to the passage of antibodies, it is currently unclear what the long-term effects for children will be,” said Dr. Tanner of the department of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, Atlanta. “It is not yet known what level of antibodies is necessary to convey protection to either neonates or children. This is an active area of investigation at multiple institutions.”

Dr. Tanner said she wished the study “evaluated neonatal cord blood or serum levels to better understand the immune response mounted by the children of women who received vaccination.”

Researchers of the current study said larger prospective studies are needed to confirm the safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in individuals who are breastfeeding and further assess the association of vaccination with infants’ health and SARS-CoV-2–specific immunity.

Dr. Palau and Dr. Tanner had no relevant financial disclosures.

JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Task force affirms routine gestational diabetes testing

Asymptomatic pregnant women with no previous diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 weeks’ gestation or later, according to an updated recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Pregnant individuals who develop gestational diabetes are at increased risk for complications including preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, as well as negative long-term outcomes for themselves and their children, wrote lead author Karina W. Davidson, PhD, of Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. The statement was published online in JAMA.

The B recommendation and I statement reflect “moderate certainty” that current evidence supports the recommendation in terms of harms versus benefits, and is consistent with the 2014 USPSTF recommendation.

The statement calls for a one-time screening using a glucose tolerance test at or after 24 weeks’ gestation. Although most screening in the United States takes place prior to 28 weeks’ gestation, it can be performed later in patients who begin prenatal care after 28 weeks’ gestation, according to the statement. Data on the harms and benefits of gestational diabetes screening prior to 24 weeks’ gestation are limited, the authors noted. Gestational diabetes was defined as diabetes that develops during pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes.

To update the 2014 recommendation, the USPSTF commissioned a systematic review. In 45 prospective studies on the accuracy of gestational diabetes screening, several tests, included oral glucose challenge test, oral glucose tolerance test, and fasting plasma glucose using either a one- or two-step approach were accurate detectors of gestational diabetes; therefore, the USPSTF does not recommend a specific test.

In 13 trials on the impact of treating gestational diabetes on intermediate and health outcomes, treatment was associated with a reduced risk of outcomes, including primary cesarean delivery (but not total cesarean delivery) and preterm delivery, but not with a reduced risk of outcomes including preeclampsia, emergency cesarean delivery, induction of labor, or maternal birth trauma.

The task force also reviewed seven studies of harms associated with screening for gestational diabetes, including three on psychosocial harms, three on hospital experiences, and one of the odds of cesarean delivery after a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. No increase in anxiety or depression occurred following a positive diagnosis or false-positive test result, but data suggested that a gestational diabetes diagnosis may be associated with higher rates of cesarean delivery.

A total of 13 trials evaluated the harms associated with treatment of gestational diabetes, and found no association between treatment and increased risk of several outcomes including severe maternal hypoglycemia, low birth weight, and small for gestational age, and no effect was noted on the number of cesarean deliveries.

Evidence gaps that require additional research include randomized, controlled trials on the effects of gestational diabetes screening on health outcomes, as well as benefits versus harms of screening for pregnant individuals prior to 24 weeks, and studies on the effects of screening in subpopulations of race/ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic factors, according to the task force. Additional research also is needed in areas of maternal health outcomes, long-term outcomes, and the effect on outcomes of one-step versus two-step screening, the USPSTF said.

However, “screening for and detecting gestational diabetes provides a potential opportunity to control blood glucose levels (through lifestyle changes, pharmacological interventions, or both) and reduce the risk of macrosomia and LGA [large for gestational age] infants,” the task force wrote. “In turn, this can prevent associated complications such as primary cesarean delivery, shoulder dystocia, and [neonatal] ICU admissions.”

Support screening with counseling on risk reduction

The USPSTF recommendation is important at this time because “the prevalence of gestational diabetes is increasing secondary to rising rates of obesity,” Iris Krishna, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“In 2014, based on a systematic review of literature, the USPSTF recommended screening all asymptomatic pregnant women for gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM] starting at 24 weeks’ gestation. The recommended gestational age for screening coincides with increasing insulin resistance during pregnancy with advancing gestational age,” Dr. Krishna said.

“An updated systematic review by the USPSTF concluded that existing literature continues to affirm current recommendations of universal screening for GDM at 24 weeks gestation or later. There continues, however, to be no consensus on the optimal approach to screening,” she noted.

“Screening can be performed as a two-step or one-step approach,” said Dr. Krishna. “The two-step approach is commonly used in the United States, and all pregnant women are first screened with a 50-gram oral glucose solution followed by a diagnostic test if they have a positive initial screening.

“Women with risk factors for diabetes, such as prior GDM, obesity, strong family history of diabetes, or history of fetal macrosomia, should be screened early in pregnancy for GDM and have the GDM screen repeated at 24 weeks’ gestation or later if normal in early pregnancy,” Dr. Krishna said. “Pregnant women should be counseled on the importance of diet and exercise and appropriate weight gain in pregnancy to reduce the risk of GDM. Overall, timely diagnosis of gestational diabetes is crucial to improving maternal and fetal pregnancy outcomes.”

The full recommendation statement is also available on the USPSTF website. The research was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Krishna had no disclosures, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Ob.Gyn News.

Asymptomatic pregnant women with no previous diagnosis of type 1 or 2 diabetes should be screened for gestational diabetes at 24 weeks’ gestation or later, according to an updated recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Pregnant individuals who develop gestational diabetes are at increased risk for complications including preeclampsia, fetal macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycemia, as well as negative long-term outcomes for themselves and their children, wrote lead author Karina W. Davidson, PhD, of Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, N.Y., and colleagues. The statement was published online in JAMA.

The B recommendation and I statement reflect “moderate certainty” that current evidence supports the recommendation in terms of harms versus benefits, and is consistent with the 2014 USPSTF recommendation.

The statement calls for a one-time screening using a glucose tolerance test at or after 24 weeks’ gestation. Although most screening in the United States takes place prior to 28 weeks’ gestation, it can be performed later in patients who begin prenatal care after 28 weeks’ gestation, according to the statement. Data on the harms and benefits of gestational diabetes screening prior to 24 weeks’ gestation are limited, the authors noted. Gestational diabetes was defined as diabetes that develops during pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes.

To update the 2014 recommendation, the USPSTF commissioned a systematic review. In 45 prospective studies on the accuracy of gestational diabetes screening, several tests, included oral glucose challenge test, oral glucose tolerance test, and fasting plasma glucose using either a one- or two-step approach were accurate detectors of gestational diabetes; therefore, the USPSTF does not recommend a specific test.

In 13 trials on the impact of treating gestational diabetes on intermediate and health outcomes, treatment was associated with a reduced risk of outcomes, including primary cesarean delivery (but not total cesarean delivery) and preterm delivery, but not with a reduced risk of outcomes including preeclampsia, emergency cesarean delivery, induction of labor, or maternal birth trauma.

The task force also reviewed seven studies of harms associated with screening for gestational diabetes, including three on psychosocial harms, three on hospital experiences, and one of the odds of cesarean delivery after a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. No increase in anxiety or depression occurred following a positive diagnosis or false-positive test result, but data suggested that a gestational diabetes diagnosis may be associated with higher rates of cesarean delivery.

A total of 13 trials evaluated the harms associated with treatment of gestational diabetes, and found no association between treatment and increased risk of several outcomes including severe maternal hypoglycemia, low birth weight, and small for gestational age, and no effect was noted on the number of cesarean deliveries.