User login

The X-waiver is dead

In 2016, when Erin Schanning lost her brother Ethan to an overdose, she wanted to know what could have been done to have helped him. Ethan, who had struggled with opioids since getting a prescription for the drugs after a dental procedure in middle school, had tried dozens of treatments. But at the age of 30, he was gone.

“After my brother died, I started researching and was surprised to learn that there were many evidence-based ways to treat substance use disorder that he hadn’t had access to, even though he had doggedly pursued treatment,” Ms. Schanning told me in an interview. One of those treatments, buprenorphine, is one of the most effective tools that health care providers have to treat opioid use disorder. A partial opioid agonist, it reduces cravings and prevents overdose, decreasing mortality more effectively than almost any medication for any disease. Yet most providers have never prescribed it.

That may be about to change. The special license to prescribe the medication, commonly known as the “X-waiver,” was officially eliminated as part of the passage of the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act. Immediately, following the passage of the Act, any provider with a DEA license became eligible to prescribe buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder, and limits on the number of patients they could treat were eliminated.

Previously, buprenorphine, which has a better safety profile than almost any other prescription opioid because of its ceiling effect on respiratory depression, nonetheless required providers to obtain a special license to prescribe it, and – prior to an executive order from the Biden administration – 8 to 24 hours of training to do so. This led to a misconception that buprenorphine was dangerous, and created barriers for treatment during the worst overdose crisis in our country’s history. More than 110,00 overdose deaths occurred in 2021, representing a 468% increase in the last 2 decades.

Along with the MAT Act, the Medication Access and Training Expansion Act was passed in the same spending bill, requiring all prescribers who obtain a DEA license to do 8 hours of training on the treatment of substance use disorders. According to the Act, addiction specialty societies will have a role in creating trainings. Medical schools and residencies will also be able to fulfill this requirement with a “comprehensive” curriculum that covers all approved medications for the treatment of substance use disorders.

The DEA has not yet confirmed what training will be accepted, according to the Chief Medical Officer of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Neeraj Gandotra, MD, who spoke to me in an interview. However, it is required to do so by April 5, 2023. Dr. Gandotra also emphasized that state and local laws, as well as insurance requirements, remain in place, and may place other constraints on prescribing. According to the Act, this new rule will be in effect by June 2023.

As an addiction medicine specialist and longtime buprenorphine prescriber, I am excited about these changes but wary of lingering resistance among health care providers. Will providers who have chosen not to get an X-waiver now look for another reason to not treat patients with substance use disorders?

Ms. Schanning remains hopeful. “I’m incredibly optimistic that health care providers are going to learn about buprenorphine and prescribe it to patients, and that patients are going to start asking about this medication,” she told me. “Seven in 10 providers say that they do feel an obligation to treat their patients with [opioid use disorder], but the federal government has made it very difficult to do so.”

Now with the X-waiver gone, providers and patients may be able to push for a long overdue shift in how we treat and conceptualize substance use disorders, she noted.

“Health care providers need to recognize substance use disorder as a medical condition that deserves treatment, and to speak about it like a medical condition,” Ms. Schanning said, by, for instance, moving away from using words such as “abuse” and “clean” and, instead, talking about treatable substance use disorders that can improve with evidence-based care, such as buprenorphine and methadone. “We also need to share stories of success and hope with people,” she added. “Once you’ve seen how someone can be transformed by treatment, it’s really difficult to say that substance use disorder is a character flaw, or their fault.”

A patient-centered approach

Over the past decade of practicing medicine, I have experienced this transformation personally. In residency, I believed that people had to be ready for help, to stop using, to change. I failed to recognize that many of those same people were asking me for help, and I wasn’t offering what they needed. The person who had to change was me.

As I moved toward a patient-centered approach, lowering barriers to starting and remaining in treatment, and collaborating with teams that could meet people wherever they might be, addictions became the most rewarding part of my practice.

I have never had more people thank me spontaneously and deeply for the care I provide. Plus, I have never seen a more profound change in the students I work with than when they witness someone with a substance use disorder offered treatment that works.

The X-waiver was not the only barrier to care, and the overdose crisis is not slowing down. But maybe with a new tool widely accessible, more of us will be ready to help.

Dr. Poorman is board certified in internal medicine and addiction medicine, assistant professor of medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, and provides primary care and addiction services in Chicago. Her views do not necessarily reflect the views of her employer. She has reported no relevant disclosures, and she serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

In 2016, when Erin Schanning lost her brother Ethan to an overdose, she wanted to know what could have been done to have helped him. Ethan, who had struggled with opioids since getting a prescription for the drugs after a dental procedure in middle school, had tried dozens of treatments. But at the age of 30, he was gone.

“After my brother died, I started researching and was surprised to learn that there were many evidence-based ways to treat substance use disorder that he hadn’t had access to, even though he had doggedly pursued treatment,” Ms. Schanning told me in an interview. One of those treatments, buprenorphine, is one of the most effective tools that health care providers have to treat opioid use disorder. A partial opioid agonist, it reduces cravings and prevents overdose, decreasing mortality more effectively than almost any medication for any disease. Yet most providers have never prescribed it.

That may be about to change. The special license to prescribe the medication, commonly known as the “X-waiver,” was officially eliminated as part of the passage of the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act. Immediately, following the passage of the Act, any provider with a DEA license became eligible to prescribe buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder, and limits on the number of patients they could treat were eliminated.

Previously, buprenorphine, which has a better safety profile than almost any other prescription opioid because of its ceiling effect on respiratory depression, nonetheless required providers to obtain a special license to prescribe it, and – prior to an executive order from the Biden administration – 8 to 24 hours of training to do so. This led to a misconception that buprenorphine was dangerous, and created barriers for treatment during the worst overdose crisis in our country’s history. More than 110,00 overdose deaths occurred in 2021, representing a 468% increase in the last 2 decades.

Along with the MAT Act, the Medication Access and Training Expansion Act was passed in the same spending bill, requiring all prescribers who obtain a DEA license to do 8 hours of training on the treatment of substance use disorders. According to the Act, addiction specialty societies will have a role in creating trainings. Medical schools and residencies will also be able to fulfill this requirement with a “comprehensive” curriculum that covers all approved medications for the treatment of substance use disorders.

The DEA has not yet confirmed what training will be accepted, according to the Chief Medical Officer of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Neeraj Gandotra, MD, who spoke to me in an interview. However, it is required to do so by April 5, 2023. Dr. Gandotra also emphasized that state and local laws, as well as insurance requirements, remain in place, and may place other constraints on prescribing. According to the Act, this new rule will be in effect by June 2023.

As an addiction medicine specialist and longtime buprenorphine prescriber, I am excited about these changes but wary of lingering resistance among health care providers. Will providers who have chosen not to get an X-waiver now look for another reason to not treat patients with substance use disorders?

Ms. Schanning remains hopeful. “I’m incredibly optimistic that health care providers are going to learn about buprenorphine and prescribe it to patients, and that patients are going to start asking about this medication,” she told me. “Seven in 10 providers say that they do feel an obligation to treat their patients with [opioid use disorder], but the federal government has made it very difficult to do so.”

Now with the X-waiver gone, providers and patients may be able to push for a long overdue shift in how we treat and conceptualize substance use disorders, she noted.

“Health care providers need to recognize substance use disorder as a medical condition that deserves treatment, and to speak about it like a medical condition,” Ms. Schanning said, by, for instance, moving away from using words such as “abuse” and “clean” and, instead, talking about treatable substance use disorders that can improve with evidence-based care, such as buprenorphine and methadone. “We also need to share stories of success and hope with people,” she added. “Once you’ve seen how someone can be transformed by treatment, it’s really difficult to say that substance use disorder is a character flaw, or their fault.”

A patient-centered approach

Over the past decade of practicing medicine, I have experienced this transformation personally. In residency, I believed that people had to be ready for help, to stop using, to change. I failed to recognize that many of those same people were asking me for help, and I wasn’t offering what they needed. The person who had to change was me.

As I moved toward a patient-centered approach, lowering barriers to starting and remaining in treatment, and collaborating with teams that could meet people wherever they might be, addictions became the most rewarding part of my practice.

I have never had more people thank me spontaneously and deeply for the care I provide. Plus, I have never seen a more profound change in the students I work with than when they witness someone with a substance use disorder offered treatment that works.

The X-waiver was not the only barrier to care, and the overdose crisis is not slowing down. But maybe with a new tool widely accessible, more of us will be ready to help.

Dr. Poorman is board certified in internal medicine and addiction medicine, assistant professor of medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, and provides primary care and addiction services in Chicago. Her views do not necessarily reflect the views of her employer. She has reported no relevant disclosures, and she serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

In 2016, when Erin Schanning lost her brother Ethan to an overdose, she wanted to know what could have been done to have helped him. Ethan, who had struggled with opioids since getting a prescription for the drugs after a dental procedure in middle school, had tried dozens of treatments. But at the age of 30, he was gone.

“After my brother died, I started researching and was surprised to learn that there were many evidence-based ways to treat substance use disorder that he hadn’t had access to, even though he had doggedly pursued treatment,” Ms. Schanning told me in an interview. One of those treatments, buprenorphine, is one of the most effective tools that health care providers have to treat opioid use disorder. A partial opioid agonist, it reduces cravings and prevents overdose, decreasing mortality more effectively than almost any medication for any disease. Yet most providers have never prescribed it.

That may be about to change. The special license to prescribe the medication, commonly known as the “X-waiver,” was officially eliminated as part of the passage of the Mainstreaming Addiction Treatment (MAT) Act. Immediately, following the passage of the Act, any provider with a DEA license became eligible to prescribe buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder, and limits on the number of patients they could treat were eliminated.

Previously, buprenorphine, which has a better safety profile than almost any other prescription opioid because of its ceiling effect on respiratory depression, nonetheless required providers to obtain a special license to prescribe it, and – prior to an executive order from the Biden administration – 8 to 24 hours of training to do so. This led to a misconception that buprenorphine was dangerous, and created barriers for treatment during the worst overdose crisis in our country’s history. More than 110,00 overdose deaths occurred in 2021, representing a 468% increase in the last 2 decades.

Along with the MAT Act, the Medication Access and Training Expansion Act was passed in the same spending bill, requiring all prescribers who obtain a DEA license to do 8 hours of training on the treatment of substance use disorders. According to the Act, addiction specialty societies will have a role in creating trainings. Medical schools and residencies will also be able to fulfill this requirement with a “comprehensive” curriculum that covers all approved medications for the treatment of substance use disorders.

The DEA has not yet confirmed what training will be accepted, according to the Chief Medical Officer of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Neeraj Gandotra, MD, who spoke to me in an interview. However, it is required to do so by April 5, 2023. Dr. Gandotra also emphasized that state and local laws, as well as insurance requirements, remain in place, and may place other constraints on prescribing. According to the Act, this new rule will be in effect by June 2023.

As an addiction medicine specialist and longtime buprenorphine prescriber, I am excited about these changes but wary of lingering resistance among health care providers. Will providers who have chosen not to get an X-waiver now look for another reason to not treat patients with substance use disorders?

Ms. Schanning remains hopeful. “I’m incredibly optimistic that health care providers are going to learn about buprenorphine and prescribe it to patients, and that patients are going to start asking about this medication,” she told me. “Seven in 10 providers say that they do feel an obligation to treat their patients with [opioid use disorder], but the federal government has made it very difficult to do so.”

Now with the X-waiver gone, providers and patients may be able to push for a long overdue shift in how we treat and conceptualize substance use disorders, she noted.

“Health care providers need to recognize substance use disorder as a medical condition that deserves treatment, and to speak about it like a medical condition,” Ms. Schanning said, by, for instance, moving away from using words such as “abuse” and “clean” and, instead, talking about treatable substance use disorders that can improve with evidence-based care, such as buprenorphine and methadone. “We also need to share stories of success and hope with people,” she added. “Once you’ve seen how someone can be transformed by treatment, it’s really difficult to say that substance use disorder is a character flaw, or their fault.”

A patient-centered approach

Over the past decade of practicing medicine, I have experienced this transformation personally. In residency, I believed that people had to be ready for help, to stop using, to change. I failed to recognize that many of those same people were asking me for help, and I wasn’t offering what they needed. The person who had to change was me.

As I moved toward a patient-centered approach, lowering barriers to starting and remaining in treatment, and collaborating with teams that could meet people wherever they might be, addictions became the most rewarding part of my practice.

I have never had more people thank me spontaneously and deeply for the care I provide. Plus, I have never seen a more profound change in the students I work with than when they witness someone with a substance use disorder offered treatment that works.

The X-waiver was not the only barrier to care, and the overdose crisis is not slowing down. But maybe with a new tool widely accessible, more of us will be ready to help.

Dr. Poorman is board certified in internal medicine and addiction medicine, assistant professor of medicine, University of Illinois at Chicago, and provides primary care and addiction services in Chicago. Her views do not necessarily reflect the views of her employer. She has reported no relevant disclosures, and she serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

Incorporating medication abortion into your ObGyn practice: Why and how

The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision on June 24, 2022, which nullified the federal protections of Roe v Wade, resulted in the swift and devastating dissolution of access to abortion care for hundreds of thousands of patients in the United States.1 Within days of the decision, 11 states in the South and Midwest implemented complete or 6-week abortion bans that, in part, led to the closure of over half the abortion clinics in these states.2 Abortion bans, severe restrictions, and clinic closures affect all patients and magnify existing health care inequities.

Medication abortion is becoming increasingly popular; as of 2020, approximately 50% of US abortions were performed using this method.3 Through a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, medication abortion induces the physiologic process and symptoms similar to those of a miscarriage. Notably, this regimen is also the most effective medical management method for a missed abortion in the first trimester, and therefore, should already be incorporated into any general ObGyn practice.4

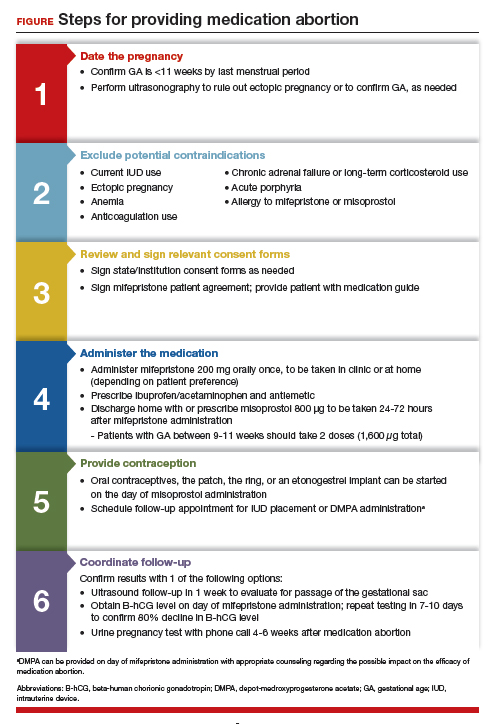

Although a recent study found that 97% of ObGyn physicians report encountering patients who seek an abortion, only 15% to 25% of them reported providing abortion services.5,6 Given our expertise, ObGyns are well-positioned to incorporate medication abortion into our practices. For those ObGyn providers who practice in states without extreme abortion bans, this article provides guidance on how to incorporate medication abortion into your practice (FIGURE). Several states now have early gestational limits on abortion, and the abortion-dedicated clinics that remain open are over capacity. Therefore, by incorporating medication abortion into your practice you can contribute to timely abortion access for your patients.

Medication abortion: The process

Determine your ability and patient’s eligibility

Abortion-specific laws for your state have now become the first determinant of your ability to provide medication abortion to your patients. The Guttmacher Institute is one reliable source of specific state laws that your practice can reference and is updated regularly.7

From a practice perspective, most ObGyn physicians already have the technical capabilities in place to provide medication abortion. First, you must be able to accurately determine the patient’s gestational age by their last menstrual period, which is often confirmed through ultrasonography.

Medication abortion is safe and routinely used in many practices up to 77 days, or 11 weeks, of gestation. Authors of a recent retrospective cohort study found that medication abortion also may be initiated for a pregnancy of unknown location in patients who are asymptomatic and determined to have low risk for an ectopic pregnancy. In this study, initiation of medication abortion on the day of presentation, with concurrent evaluation for ectopic pregnancy, was associated with a shorter time to a completed abortion, but a lower rate of successful medication abortion when compared with patients who delayed the initiation of medication abortion until a clear intrauterine pregnancy was diagnosed.8

Few medical contraindications exist for patients who seek a medication abortion. These contraindications include allergy to or medication interaction with mifepristone or misoprostol, chronic adrenal failure or long-term corticosteroid therapy, acute porphyria, anemia or the use of anticoagulation therapy, or current intrauterine device (IUD) use.

Continue to: Gather consents and administer treatment...

Gather consents and administer treatment

Historically, mifepristone has been dispensed directly at an ObGyn physician’s office. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations requiring this were lifted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as of December 2021, the inperson dispensing requirement was permanently removed.9 To provide mifepristone in a medical practice under current guidelines, a confidential prescriber agreement must be completed once by one person on behalf of the practice. Then each patient must read the manufacturer’s medication guide and sign the patient agreement form as part of the consent process (available on the FDA’s website).10 These agreement forms must be filled out by a physician and each patient if your practice uses mifepristone for any pregnancy indication, including induction of labor or medical management of miscarriage. Given the multiple evidence-based indications for mifepristone in pregnancy, it is hoped that these agreement forms will become a routine part of most ObGyn practices. Other consent requirements vary by state.

After signing consent forms, patients receive and often immediately take mifepristone 200 mg orally. Mifepristone is a progesterone receptor antagonist that sensitizes the uterine myometrium to the effects of prostaglandin.11 Rarely, patients may experience symptoms of bleeding or cramping after mifepristone administration alone.

Patients are discharged home with ibuprofen and an antiemetic for symptom relief to be taken around the time of administration of misoprostol. Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin that causes uterine cramping and expulsion of the pregnancy typically within 4 hours of administration. Patients leave with the pills of misoprostol 800 μg (4 tablets, 200 µg each), which they self-administer buccally 24-48 hours after mifepristone administration. A prescription for misoprostol can be given instead of the actual pills, but geographic distance to the pharmacy and other potential barriers should be considered when evaluating the feasibility and convenience of providing pharmacy-dispensed misoprostol.

We instruct patients to place 2 tablets buccally between each gum and cheek, dosing all 4 tablets at the same time. Patients are instructed to let the tablets dissolve buccally and, after 30 minutes, to swallow the tablets with water. Administration of an automatic second dose of misoprostol 3-6 hours after the first dose for pregnancies between 9-11 weeks of gestation is recommended to increase success rate at these later gestational ages.12,13 Several different routes of administration, including buccal, vaginal, and sublingual, have been used for first trimester medication abortion with misoprostol.

Follow up and confirm the results

Patients can safely follow up after their medication abortion in several ways. In our practice, patients are offered 3 possible options.

- The first is ultrasound follow-up, whereby the patient returns to the clinic 1 week after their medication abortion for a pelvic ultrasound to confirm the gestational sac has passed.

- The second method is to test beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (B-hCG) levels. Patients interested in this option have a baseline B-hCG drawn on the day of presentation and follow up 7-10 days later for a repeat B-hCG test. An 80% drop in B-hCG level is consistent with a successful medication abortion.

- The third option, a phone checklist that is usually combined with a urine pregnancy test 4-6 weeks after a medication abortion, is an effective patient-centered approach. The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent compulsory shift to providing medical care via telemedicine highlighted the safety, acceptability, and patient preference for the provision of medication abortion using telehealth platforms.14

Outcomes and complications

Medication abortion using a combined regimen of mifepristone followed by misoprostol is approximately 95% effective at complete expulsion of the pregnancy.15,16 Complications after a first trimester medication abortion are rare. In a retrospective cohort study of 54,911 abortions, the most common complication was incomplete abortion.17 Symptoms concerning for incomplete abortion included persistent heavy vaginal bleeding and pelvic cramping. An incomplete or failed abortion should be managed with an additional dose of misoprostol or dilation and evacuation. Other possible complications such as infection are also rare, and prophylactic antibiotics are not encouraged.18

Future fertility and pregnancy implications

Patients should be counseled that a medication abortion is not associated with infertility or increased risk for adverse outcomes in future pregnancies.19 Contraceptive counseling should be provided to all interested patients at the time of a medication abortion and ideally provided to the patient on the day of their visit. Oral contraceptives, the patch, and the ring can be started on the day of misoprostol administration.20 The optimal timing of IUD insertion has been examined in 2 randomized control trials. Results indicated a higher uptake in the group of patients who received their IUD approximately 1 week after medication abortion versus delaying placement for several weeks, with no difference in IUD expulsion rates.21,22 Patients interested in depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injection should be counseled on the theoretical decreased efficacy of medication abortion in the setting of concurrent DMPA administration. If possible, a follow-up plan should be made so that the patient can receive DMPA, if desired, at a later date.23 The etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon), however, can be placed on the day of mifepristone administration and does not affect the efficacy of a medication abortion.24,25

Summary

During this critical time for reproductive health care, it is essential that ObGyns consider how their professional position and expertise can assist with the provision of medication abortions. Most ObGyn practices already have the resources in place to effectively care for patients before, during, and after a medication abortion. Integrating abortion health care into your practice promotes patient-centered care, continuity, and patient satisfaction. Furthermore, by improving abortion referrals or offering information on safe, self-procured abortion, you can contribute to destigmatizing abortion care, while playing an integral role in connecting your patients with the care they need and desire. ●

- Jones RK, Philbin J, Kirstein M, et al. Long-term decline in US abortions reverses, showing rising need for abortion as Supreme Court is poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. Guttmacher Institute. August 30, 2022. https://www.gut. Accessed November 2, 2022. tmacher.org/article/2022/06 /long-term-decline-us-abortions-reverses-showing-rising -need-abortion-supreme-court.

- Kirstein M, Jones RK, Philbin J. One month post-roe: at least 43 abortion clinics across 11 states have stopped offering abortion care. Guttmacher Institute. September 5, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2022/07/one-month -post-roe-least-43-abortion-clinics-across-11-states-have -stopped-offering. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Jones RK, Nash E, Cross L, et al. Medication abortion now accounts for more than half of all US abortions. Guttmacher Institute. September 12, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org /article/2022/02/medication-abortion-now-accounts-more-half-all-us-abortions. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170. doi:10.1056/ nejmoa1715726.

- Stulberg DB, Dude AM, Dahlquist I, Curlin, FA. Abortion provision among practicing obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:609-614. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31822ad973.

- Daniel S, Schulkin J, Grossman D. Obstetrician-gynecologist willingness to provide medication abortion with removal of the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone. Contraception. 2021;104:73-76. doi:10.1016/j. contraception.2021.03.026.

- Guttmacher Institute. State legislation tracker. Updated October 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Goldberg AB, Fulcher IR, Fortin J, et al. Mifepristone and misoprostol for undesired pregnancy of unknown location. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:771-780. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000004756.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Understanding the practical implications of the FDA’s December 2021 mifepristone REMS decision: a Q&A with Dr. Nisha Verma and Vanessa Wellbery. March 28, 2022. https:// www.acog.org/news/news-articles/2022/03/understanding -the-practical-implications-of-the-fdas-december-2021 -mifepristone-rems-decision. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information. December 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/ drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ifeprex-mifepristone-information. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Cadepond F, Ulmann A, Baulieu EE. Ru486 (mifepristone): mechanisms of action and clinical uses. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:129-156. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.129.

- Ashok PW, Templeton A, Wagaarachchi PT, Flett GMM. Factors affecting the outcome of early medical abortion: a review of 4132 consecutive cases. BJOG. 2002;109:1281-1289. doi:10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02156.x.

- Coyaji K, Krishna U, Ambardekar S, et al. Are two doses of misoprostol after mifepristone for early abortion better than one? BJOG. 2007;114:271-278. doi:10.1111/j.14710528.2006.01208.x.

- Aiken A, Lohr PA, Lord J, et al. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of no‐test medical abortion (termination of pregnancy) provided via telemedicine: a national cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1464-1474. doi:10.1111/14710528.16668.

- Schaff EA, Eisinger SH, Stadalius LS, et al. Low-dose mifepristone 200 mg and vaginal misoprostol for abortion. Contraception. 1999;59:1-6. doi:10.1016/s00107824(98)00150-4.

- Schaff EA, Fielding SL, Westhoff C. Randomized trial of oral versus vaginal misoprostol at one day after mifepristone for early medical abortion. Contraception. 2001;64:81-85. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00229-3.

- Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:175-183. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000000603.

- Shannon C, Brothers LP, Philip NM, Winikoff B. Infection after medical abortion: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2004;70:183-190. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.009.

- Virk J, Zhang J, Olsen J. Medical abortion and the risk of subsequent adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:648-653. doi:10.1056/nejmoa070445.

- Mittal S. Contraception after medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:56-60. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.006.

- Shimoni N, Davis A, Ramos ME, et al. Timing of copper intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:623-628. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31822ade67.

- Sääv I, Stephansson O, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Early versus delayed insertion of intrauterine contraception after medical abortion—a randomized controlled trial. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e48948. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048948.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Louie KS, et al. Effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection timing on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:739-745. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001627.

- Hognert H, Kopp Kallner H, Cameron S, et al. Immediate versus delayed insertion of an etonogestrel releasing implant at medical abortion—a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2484-2490. doi:10.1093/humrep/ dew238.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Tan Y-L, et al. Effect of immediate compared with delayed insertion of etonogestrel implants on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:306-312. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000001274.

The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision on June 24, 2022, which nullified the federal protections of Roe v Wade, resulted in the swift and devastating dissolution of access to abortion care for hundreds of thousands of patients in the United States.1 Within days of the decision, 11 states in the South and Midwest implemented complete or 6-week abortion bans that, in part, led to the closure of over half the abortion clinics in these states.2 Abortion bans, severe restrictions, and clinic closures affect all patients and magnify existing health care inequities.

Medication abortion is becoming increasingly popular; as of 2020, approximately 50% of US abortions were performed using this method.3 Through a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, medication abortion induces the physiologic process and symptoms similar to those of a miscarriage. Notably, this regimen is also the most effective medical management method for a missed abortion in the first trimester, and therefore, should already be incorporated into any general ObGyn practice.4

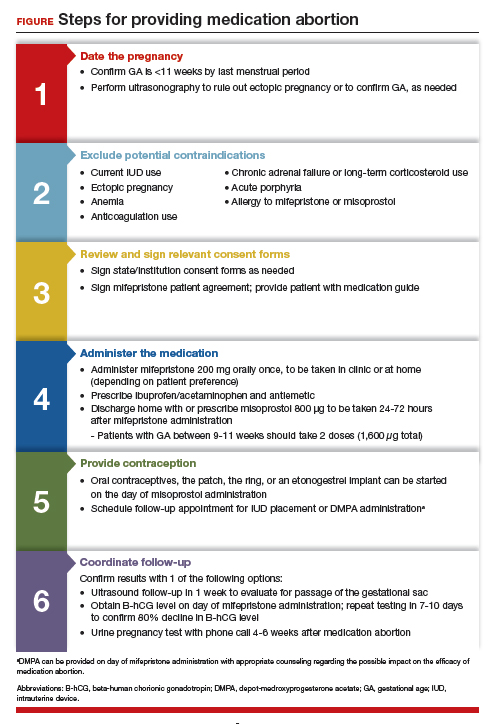

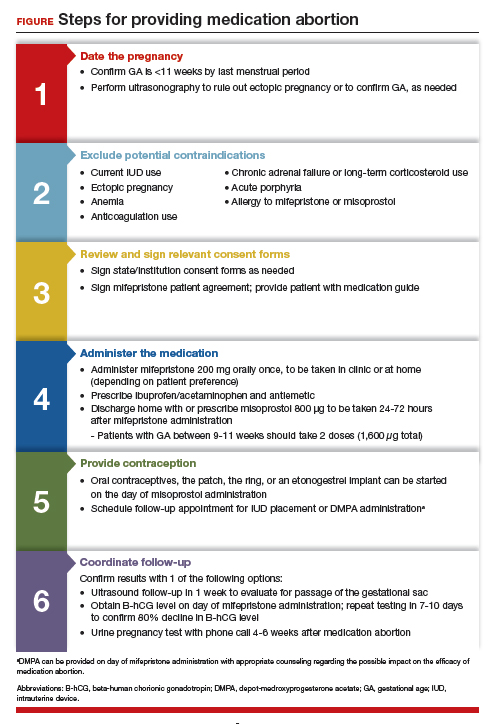

Although a recent study found that 97% of ObGyn physicians report encountering patients who seek an abortion, only 15% to 25% of them reported providing abortion services.5,6 Given our expertise, ObGyns are well-positioned to incorporate medication abortion into our practices. For those ObGyn providers who practice in states without extreme abortion bans, this article provides guidance on how to incorporate medication abortion into your practice (FIGURE). Several states now have early gestational limits on abortion, and the abortion-dedicated clinics that remain open are over capacity. Therefore, by incorporating medication abortion into your practice you can contribute to timely abortion access for your patients.

Medication abortion: The process

Determine your ability and patient’s eligibility

Abortion-specific laws for your state have now become the first determinant of your ability to provide medication abortion to your patients. The Guttmacher Institute is one reliable source of specific state laws that your practice can reference and is updated regularly.7

From a practice perspective, most ObGyn physicians already have the technical capabilities in place to provide medication abortion. First, you must be able to accurately determine the patient’s gestational age by their last menstrual period, which is often confirmed through ultrasonography.

Medication abortion is safe and routinely used in many practices up to 77 days, or 11 weeks, of gestation. Authors of a recent retrospective cohort study found that medication abortion also may be initiated for a pregnancy of unknown location in patients who are asymptomatic and determined to have low risk for an ectopic pregnancy. In this study, initiation of medication abortion on the day of presentation, with concurrent evaluation for ectopic pregnancy, was associated with a shorter time to a completed abortion, but a lower rate of successful medication abortion when compared with patients who delayed the initiation of medication abortion until a clear intrauterine pregnancy was diagnosed.8

Few medical contraindications exist for patients who seek a medication abortion. These contraindications include allergy to or medication interaction with mifepristone or misoprostol, chronic adrenal failure or long-term corticosteroid therapy, acute porphyria, anemia or the use of anticoagulation therapy, or current intrauterine device (IUD) use.

Continue to: Gather consents and administer treatment...

Gather consents and administer treatment

Historically, mifepristone has been dispensed directly at an ObGyn physician’s office. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations requiring this were lifted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as of December 2021, the inperson dispensing requirement was permanently removed.9 To provide mifepristone in a medical practice under current guidelines, a confidential prescriber agreement must be completed once by one person on behalf of the practice. Then each patient must read the manufacturer’s medication guide and sign the patient agreement form as part of the consent process (available on the FDA’s website).10 These agreement forms must be filled out by a physician and each patient if your practice uses mifepristone for any pregnancy indication, including induction of labor or medical management of miscarriage. Given the multiple evidence-based indications for mifepristone in pregnancy, it is hoped that these agreement forms will become a routine part of most ObGyn practices. Other consent requirements vary by state.

After signing consent forms, patients receive and often immediately take mifepristone 200 mg orally. Mifepristone is a progesterone receptor antagonist that sensitizes the uterine myometrium to the effects of prostaglandin.11 Rarely, patients may experience symptoms of bleeding or cramping after mifepristone administration alone.

Patients are discharged home with ibuprofen and an antiemetic for symptom relief to be taken around the time of administration of misoprostol. Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin that causes uterine cramping and expulsion of the pregnancy typically within 4 hours of administration. Patients leave with the pills of misoprostol 800 μg (4 tablets, 200 µg each), which they self-administer buccally 24-48 hours after mifepristone administration. A prescription for misoprostol can be given instead of the actual pills, but geographic distance to the pharmacy and other potential barriers should be considered when evaluating the feasibility and convenience of providing pharmacy-dispensed misoprostol.

We instruct patients to place 2 tablets buccally between each gum and cheek, dosing all 4 tablets at the same time. Patients are instructed to let the tablets dissolve buccally and, after 30 minutes, to swallow the tablets with water. Administration of an automatic second dose of misoprostol 3-6 hours after the first dose for pregnancies between 9-11 weeks of gestation is recommended to increase success rate at these later gestational ages.12,13 Several different routes of administration, including buccal, vaginal, and sublingual, have been used for first trimester medication abortion with misoprostol.

Follow up and confirm the results

Patients can safely follow up after their medication abortion in several ways. In our practice, patients are offered 3 possible options.

- The first is ultrasound follow-up, whereby the patient returns to the clinic 1 week after their medication abortion for a pelvic ultrasound to confirm the gestational sac has passed.

- The second method is to test beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (B-hCG) levels. Patients interested in this option have a baseline B-hCG drawn on the day of presentation and follow up 7-10 days later for a repeat B-hCG test. An 80% drop in B-hCG level is consistent with a successful medication abortion.

- The third option, a phone checklist that is usually combined with a urine pregnancy test 4-6 weeks after a medication abortion, is an effective patient-centered approach. The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent compulsory shift to providing medical care via telemedicine highlighted the safety, acceptability, and patient preference for the provision of medication abortion using telehealth platforms.14

Outcomes and complications

Medication abortion using a combined regimen of mifepristone followed by misoprostol is approximately 95% effective at complete expulsion of the pregnancy.15,16 Complications after a first trimester medication abortion are rare. In a retrospective cohort study of 54,911 abortions, the most common complication was incomplete abortion.17 Symptoms concerning for incomplete abortion included persistent heavy vaginal bleeding and pelvic cramping. An incomplete or failed abortion should be managed with an additional dose of misoprostol or dilation and evacuation. Other possible complications such as infection are also rare, and prophylactic antibiotics are not encouraged.18

Future fertility and pregnancy implications

Patients should be counseled that a medication abortion is not associated with infertility or increased risk for adverse outcomes in future pregnancies.19 Contraceptive counseling should be provided to all interested patients at the time of a medication abortion and ideally provided to the patient on the day of their visit. Oral contraceptives, the patch, and the ring can be started on the day of misoprostol administration.20 The optimal timing of IUD insertion has been examined in 2 randomized control trials. Results indicated a higher uptake in the group of patients who received their IUD approximately 1 week after medication abortion versus delaying placement for several weeks, with no difference in IUD expulsion rates.21,22 Patients interested in depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injection should be counseled on the theoretical decreased efficacy of medication abortion in the setting of concurrent DMPA administration. If possible, a follow-up plan should be made so that the patient can receive DMPA, if desired, at a later date.23 The etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon), however, can be placed on the day of mifepristone administration and does not affect the efficacy of a medication abortion.24,25

Summary

During this critical time for reproductive health care, it is essential that ObGyns consider how their professional position and expertise can assist with the provision of medication abortions. Most ObGyn practices already have the resources in place to effectively care for patients before, during, and after a medication abortion. Integrating abortion health care into your practice promotes patient-centered care, continuity, and patient satisfaction. Furthermore, by improving abortion referrals or offering information on safe, self-procured abortion, you can contribute to destigmatizing abortion care, while playing an integral role in connecting your patients with the care they need and desire. ●

The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision on June 24, 2022, which nullified the federal protections of Roe v Wade, resulted in the swift and devastating dissolution of access to abortion care for hundreds of thousands of patients in the United States.1 Within days of the decision, 11 states in the South and Midwest implemented complete or 6-week abortion bans that, in part, led to the closure of over half the abortion clinics in these states.2 Abortion bans, severe restrictions, and clinic closures affect all patients and magnify existing health care inequities.

Medication abortion is becoming increasingly popular; as of 2020, approximately 50% of US abortions were performed using this method.3 Through a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, medication abortion induces the physiologic process and symptoms similar to those of a miscarriage. Notably, this regimen is also the most effective medical management method for a missed abortion in the first trimester, and therefore, should already be incorporated into any general ObGyn practice.4

Although a recent study found that 97% of ObGyn physicians report encountering patients who seek an abortion, only 15% to 25% of them reported providing abortion services.5,6 Given our expertise, ObGyns are well-positioned to incorporate medication abortion into our practices. For those ObGyn providers who practice in states without extreme abortion bans, this article provides guidance on how to incorporate medication abortion into your practice (FIGURE). Several states now have early gestational limits on abortion, and the abortion-dedicated clinics that remain open are over capacity. Therefore, by incorporating medication abortion into your practice you can contribute to timely abortion access for your patients.

Medication abortion: The process

Determine your ability and patient’s eligibility

Abortion-specific laws for your state have now become the first determinant of your ability to provide medication abortion to your patients. The Guttmacher Institute is one reliable source of specific state laws that your practice can reference and is updated regularly.7

From a practice perspective, most ObGyn physicians already have the technical capabilities in place to provide medication abortion. First, you must be able to accurately determine the patient’s gestational age by their last menstrual period, which is often confirmed through ultrasonography.

Medication abortion is safe and routinely used in many practices up to 77 days, or 11 weeks, of gestation. Authors of a recent retrospective cohort study found that medication abortion also may be initiated for a pregnancy of unknown location in patients who are asymptomatic and determined to have low risk for an ectopic pregnancy. In this study, initiation of medication abortion on the day of presentation, with concurrent evaluation for ectopic pregnancy, was associated with a shorter time to a completed abortion, but a lower rate of successful medication abortion when compared with patients who delayed the initiation of medication abortion until a clear intrauterine pregnancy was diagnosed.8

Few medical contraindications exist for patients who seek a medication abortion. These contraindications include allergy to or medication interaction with mifepristone or misoprostol, chronic adrenal failure or long-term corticosteroid therapy, acute porphyria, anemia or the use of anticoagulation therapy, or current intrauterine device (IUD) use.

Continue to: Gather consents and administer treatment...

Gather consents and administer treatment

Historically, mifepristone has been dispensed directly at an ObGyn physician’s office. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations requiring this were lifted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as of December 2021, the inperson dispensing requirement was permanently removed.9 To provide mifepristone in a medical practice under current guidelines, a confidential prescriber agreement must be completed once by one person on behalf of the practice. Then each patient must read the manufacturer’s medication guide and sign the patient agreement form as part of the consent process (available on the FDA’s website).10 These agreement forms must be filled out by a physician and each patient if your practice uses mifepristone for any pregnancy indication, including induction of labor or medical management of miscarriage. Given the multiple evidence-based indications for mifepristone in pregnancy, it is hoped that these agreement forms will become a routine part of most ObGyn practices. Other consent requirements vary by state.

After signing consent forms, patients receive and often immediately take mifepristone 200 mg orally. Mifepristone is a progesterone receptor antagonist that sensitizes the uterine myometrium to the effects of prostaglandin.11 Rarely, patients may experience symptoms of bleeding or cramping after mifepristone administration alone.

Patients are discharged home with ibuprofen and an antiemetic for symptom relief to be taken around the time of administration of misoprostol. Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin that causes uterine cramping and expulsion of the pregnancy typically within 4 hours of administration. Patients leave with the pills of misoprostol 800 μg (4 tablets, 200 µg each), which they self-administer buccally 24-48 hours after mifepristone administration. A prescription for misoprostol can be given instead of the actual pills, but geographic distance to the pharmacy and other potential barriers should be considered when evaluating the feasibility and convenience of providing pharmacy-dispensed misoprostol.

We instruct patients to place 2 tablets buccally between each gum and cheek, dosing all 4 tablets at the same time. Patients are instructed to let the tablets dissolve buccally and, after 30 minutes, to swallow the tablets with water. Administration of an automatic second dose of misoprostol 3-6 hours after the first dose for pregnancies between 9-11 weeks of gestation is recommended to increase success rate at these later gestational ages.12,13 Several different routes of administration, including buccal, vaginal, and sublingual, have been used for first trimester medication abortion with misoprostol.

Follow up and confirm the results

Patients can safely follow up after their medication abortion in several ways. In our practice, patients are offered 3 possible options.

- The first is ultrasound follow-up, whereby the patient returns to the clinic 1 week after their medication abortion for a pelvic ultrasound to confirm the gestational sac has passed.

- The second method is to test beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (B-hCG) levels. Patients interested in this option have a baseline B-hCG drawn on the day of presentation and follow up 7-10 days later for a repeat B-hCG test. An 80% drop in B-hCG level is consistent with a successful medication abortion.

- The third option, a phone checklist that is usually combined with a urine pregnancy test 4-6 weeks after a medication abortion, is an effective patient-centered approach. The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent compulsory shift to providing medical care via telemedicine highlighted the safety, acceptability, and patient preference for the provision of medication abortion using telehealth platforms.14

Outcomes and complications

Medication abortion using a combined regimen of mifepristone followed by misoprostol is approximately 95% effective at complete expulsion of the pregnancy.15,16 Complications after a first trimester medication abortion are rare. In a retrospective cohort study of 54,911 abortions, the most common complication was incomplete abortion.17 Symptoms concerning for incomplete abortion included persistent heavy vaginal bleeding and pelvic cramping. An incomplete or failed abortion should be managed with an additional dose of misoprostol or dilation and evacuation. Other possible complications such as infection are also rare, and prophylactic antibiotics are not encouraged.18

Future fertility and pregnancy implications

Patients should be counseled that a medication abortion is not associated with infertility or increased risk for adverse outcomes in future pregnancies.19 Contraceptive counseling should be provided to all interested patients at the time of a medication abortion and ideally provided to the patient on the day of their visit. Oral contraceptives, the patch, and the ring can be started on the day of misoprostol administration.20 The optimal timing of IUD insertion has been examined in 2 randomized control trials. Results indicated a higher uptake in the group of patients who received their IUD approximately 1 week after medication abortion versus delaying placement for several weeks, with no difference in IUD expulsion rates.21,22 Patients interested in depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injection should be counseled on the theoretical decreased efficacy of medication abortion in the setting of concurrent DMPA administration. If possible, a follow-up plan should be made so that the patient can receive DMPA, if desired, at a later date.23 The etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon), however, can be placed on the day of mifepristone administration and does not affect the efficacy of a medication abortion.24,25

Summary

During this critical time for reproductive health care, it is essential that ObGyns consider how their professional position and expertise can assist with the provision of medication abortions. Most ObGyn practices already have the resources in place to effectively care for patients before, during, and after a medication abortion. Integrating abortion health care into your practice promotes patient-centered care, continuity, and patient satisfaction. Furthermore, by improving abortion referrals or offering information on safe, self-procured abortion, you can contribute to destigmatizing abortion care, while playing an integral role in connecting your patients with the care they need and desire. ●

- Jones RK, Philbin J, Kirstein M, et al. Long-term decline in US abortions reverses, showing rising need for abortion as Supreme Court is poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. Guttmacher Institute. August 30, 2022. https://www.gut. Accessed November 2, 2022. tmacher.org/article/2022/06 /long-term-decline-us-abortions-reverses-showing-rising -need-abortion-supreme-court.

- Kirstein M, Jones RK, Philbin J. One month post-roe: at least 43 abortion clinics across 11 states have stopped offering abortion care. Guttmacher Institute. September 5, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2022/07/one-month -post-roe-least-43-abortion-clinics-across-11-states-have -stopped-offering. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Jones RK, Nash E, Cross L, et al. Medication abortion now accounts for more than half of all US abortions. Guttmacher Institute. September 12, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org /article/2022/02/medication-abortion-now-accounts-more-half-all-us-abortions. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170. doi:10.1056/ nejmoa1715726.

- Stulberg DB, Dude AM, Dahlquist I, Curlin, FA. Abortion provision among practicing obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:609-614. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31822ad973.

- Daniel S, Schulkin J, Grossman D. Obstetrician-gynecologist willingness to provide medication abortion with removal of the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone. Contraception. 2021;104:73-76. doi:10.1016/j. contraception.2021.03.026.

- Guttmacher Institute. State legislation tracker. Updated October 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Goldberg AB, Fulcher IR, Fortin J, et al. Mifepristone and misoprostol for undesired pregnancy of unknown location. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:771-780. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000004756.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Understanding the practical implications of the FDA’s December 2021 mifepristone REMS decision: a Q&A with Dr. Nisha Verma and Vanessa Wellbery. March 28, 2022. https:// www.acog.org/news/news-articles/2022/03/understanding -the-practical-implications-of-the-fdas-december-2021 -mifepristone-rems-decision. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information. December 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/ drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ifeprex-mifepristone-information. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Cadepond F, Ulmann A, Baulieu EE. Ru486 (mifepristone): mechanisms of action and clinical uses. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:129-156. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.129.

- Ashok PW, Templeton A, Wagaarachchi PT, Flett GMM. Factors affecting the outcome of early medical abortion: a review of 4132 consecutive cases. BJOG. 2002;109:1281-1289. doi:10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02156.x.

- Coyaji K, Krishna U, Ambardekar S, et al. Are two doses of misoprostol after mifepristone for early abortion better than one? BJOG. 2007;114:271-278. doi:10.1111/j.14710528.2006.01208.x.

- Aiken A, Lohr PA, Lord J, et al. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of no‐test medical abortion (termination of pregnancy) provided via telemedicine: a national cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1464-1474. doi:10.1111/14710528.16668.

- Schaff EA, Eisinger SH, Stadalius LS, et al. Low-dose mifepristone 200 mg and vaginal misoprostol for abortion. Contraception. 1999;59:1-6. doi:10.1016/s00107824(98)00150-4.

- Schaff EA, Fielding SL, Westhoff C. Randomized trial of oral versus vaginal misoprostol at one day after mifepristone for early medical abortion. Contraception. 2001;64:81-85. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00229-3.

- Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:175-183. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000000603.

- Shannon C, Brothers LP, Philip NM, Winikoff B. Infection after medical abortion: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2004;70:183-190. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.009.

- Virk J, Zhang J, Olsen J. Medical abortion and the risk of subsequent adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:648-653. doi:10.1056/nejmoa070445.

- Mittal S. Contraception after medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:56-60. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.006.

- Shimoni N, Davis A, Ramos ME, et al. Timing of copper intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:623-628. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31822ade67.

- Sääv I, Stephansson O, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Early versus delayed insertion of intrauterine contraception after medical abortion—a randomized controlled trial. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e48948. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048948.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Louie KS, et al. Effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection timing on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:739-745. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001627.

- Hognert H, Kopp Kallner H, Cameron S, et al. Immediate versus delayed insertion of an etonogestrel releasing implant at medical abortion—a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2484-2490. doi:10.1093/humrep/ dew238.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Tan Y-L, et al. Effect of immediate compared with delayed insertion of etonogestrel implants on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:306-312. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000001274.

- Jones RK, Philbin J, Kirstein M, et al. Long-term decline in US abortions reverses, showing rising need for abortion as Supreme Court is poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. Guttmacher Institute. August 30, 2022. https://www.gut. Accessed November 2, 2022. tmacher.org/article/2022/06 /long-term-decline-us-abortions-reverses-showing-rising -need-abortion-supreme-court.

- Kirstein M, Jones RK, Philbin J. One month post-roe: at least 43 abortion clinics across 11 states have stopped offering abortion care. Guttmacher Institute. September 5, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2022/07/one-month -post-roe-least-43-abortion-clinics-across-11-states-have -stopped-offering. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Jones RK, Nash E, Cross L, et al. Medication abortion now accounts for more than half of all US abortions. Guttmacher Institute. September 12, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org /article/2022/02/medication-abortion-now-accounts-more-half-all-us-abortions. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, et al. Mifepristone pretreatment for the medical management of early pregnancy loss. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2161-2170. doi:10.1056/ nejmoa1715726.

- Stulberg DB, Dude AM, Dahlquist I, Curlin, FA. Abortion provision among practicing obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:609-614. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31822ad973.

- Daniel S, Schulkin J, Grossman D. Obstetrician-gynecologist willingness to provide medication abortion with removal of the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone. Contraception. 2021;104:73-76. doi:10.1016/j. contraception.2021.03.026.

- Guttmacher Institute. State legislation tracker. Updated October 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Goldberg AB, Fulcher IR, Fortin J, et al. Mifepristone and misoprostol for undesired pregnancy of unknown location. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:771-780. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000004756.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Understanding the practical implications of the FDA’s December 2021 mifepristone REMS decision: a Q&A with Dr. Nisha Verma and Vanessa Wellbery. March 28, 2022. https:// www.acog.org/news/news-articles/2022/03/understanding -the-practical-implications-of-the-fdas-december-2021 -mifepristone-rems-decision. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mifeprex (mifepristone) information. December 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/ drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/ifeprex-mifepristone-information. Accessed November 2, 2022.

- Cadepond F, Ulmann A, Baulieu EE. Ru486 (mifepristone): mechanisms of action and clinical uses. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:129-156. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.129.

- Ashok PW, Templeton A, Wagaarachchi PT, Flett GMM. Factors affecting the outcome of early medical abortion: a review of 4132 consecutive cases. BJOG. 2002;109:1281-1289. doi:10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02156.x.

- Coyaji K, Krishna U, Ambardekar S, et al. Are two doses of misoprostol after mifepristone for early abortion better than one? BJOG. 2007;114:271-278. doi:10.1111/j.14710528.2006.01208.x.

- Aiken A, Lohr PA, Lord J, et al. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of no‐test medical abortion (termination of pregnancy) provided via telemedicine: a national cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1464-1474. doi:10.1111/14710528.16668.

- Schaff EA, Eisinger SH, Stadalius LS, et al. Low-dose mifepristone 200 mg and vaginal misoprostol for abortion. Contraception. 1999;59:1-6. doi:10.1016/s00107824(98)00150-4.

- Schaff EA, Fielding SL, Westhoff C. Randomized trial of oral versus vaginal misoprostol at one day after mifepristone for early medical abortion. Contraception. 2001;64:81-85. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00229-3.

- Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:175-183. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000000603.

- Shannon C, Brothers LP, Philip NM, Winikoff B. Infection after medical abortion: a review of the literature. Contraception. 2004;70:183-190. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.009.

- Virk J, Zhang J, Olsen J. Medical abortion and the risk of subsequent adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:648-653. doi:10.1056/nejmoa070445.

- Mittal S. Contraception after medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:56-60. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.006.

- Shimoni N, Davis A, Ramos ME, et al. Timing of copper intrauterine device insertion after medical abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:623-628. doi:10.1097/aog.0b013e31822ade67.

- Sääv I, Stephansson O, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Early versus delayed insertion of intrauterine contraception after medical abortion—a randomized controlled trial. PloS ONE. 2012;7:e48948. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048948.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Louie KS, et al. Effects of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection timing on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:739-745. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001627.

- Hognert H, Kopp Kallner H, Cameron S, et al. Immediate versus delayed insertion of an etonogestrel releasing implant at medical abortion—a randomized controlled equivalence trial. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2484-2490. doi:10.1093/humrep/ dew238.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Tan Y-L, et al. Effect of immediate compared with delayed insertion of etonogestrel implants on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:306-312. doi:10.1097/ aog.0000000000001274.

Buprenorphine linked with lower risk for neonatal harms than methadone

Using buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy was linked with a lower risk of neonatal side effects than using methadone, but the risk of adverse maternal outcomes was similar between the two treatments, according to new research.

Elizabeth A. Suarez, PhD, MPH, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, led the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Opioid use disorder in pregnant women has increased steadily in the United States since 2000, the authors write. As of 2017, about 8.2 per 1,000 deliveries were estimated to be affected by the disorder. The numbers were particularly high in people insured by Medicaid. In that group, an estimated 14.6 per 1,000 deliveries were affected.

Researchers studied pregnant women enrolled in public insurance programs in the United States from 2000 through 2018 in a dataset of 2,548,372 pregnancies that ended in live births. They analyzed outcomes in those who received buprenorphine as compared with those who received methadone.

They looked at different periods of exposure to the two medications: early pregnancy (through gestational week 19); late pregnancy (week 20 through the day before delivery); and the 30 days before delivery.

Highlighted differences in infants included:

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 52% of the infants who were exposed to buprenorphine in the 30 days before delivery as compared with 69.2% of those exposed to methadone (adjusted relative risk, 0.73).

- Preterm birth in 14.4% of infants exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and in 24.9% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 0.58).

- Small size for gestational age in 12.1% (buprenorphine) and 15.3% (methadone) (ARR, 0.72).

- Low birth weight in 8.3% (buprenorphine) and 14.9% (methadone) (ARR, 0.56).

- Delivery by cesarean section occurred in 33.6% of pregnant women exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and 33.1% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 1.02.).

Severe maternal complications developed in 3.3% of the women exposed to buprenorphine and 3.5% of those on methadone (ARR, 0.91.) Exposures in late pregnancy and early pregnancy yielded similar results, the authors say.

Michael Caucci, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. who also runs the Women’s Mental Health Clinic at the university, said this paper supports preliminary findings from the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER) study that suggested infants exposed to buprenorphine (compared with methadone) appeared to have lower rates of neonatal complications.

“It also supports buprenorphine as a relatively safe option for treatment of opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” said Dr. Caucci, who was not part of the study by Dr. Suarez and associates. “Reducing the fear of harming the fetus or neonate will help eliminate this barrier to perinatal substance use disorder treatment.”

But he cautions against concluding that, because buprenorphine has lower risks of fetal/neonatal complications, it is safer and therefore better than methadone in pregnancy.

“Some women do not tolerate buprenorphine and do much better on methadone, Dr. Caucci said. “Current recommendations are that both buprenorphine and methadone are relatively safe options for treatment of OUD [opioid use disorder] in pregnancy.”

Among the differences between the treatments is that while methadone is administered daily during in-person visits to federally regulated opioid treatment programs, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers, which allows patients to administer buprenorphine themselves.

Dr. Caucci said he was intrigued by the finding that there was no difference in pregnancy, neonatal, and maternal outcomes depending on the time of exposure to the agents.

“I would have expected higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or poor fetal growth in those exposed later in pregnancy vs. those with early exposure,” he said.

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Caucci reports no relevant financial relationships. The authors’ disclosures are available with the full text.

Using buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy was linked with a lower risk of neonatal side effects than using methadone, but the risk of adverse maternal outcomes was similar between the two treatments, according to new research.

Elizabeth A. Suarez, PhD, MPH, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, led the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Opioid use disorder in pregnant women has increased steadily in the United States since 2000, the authors write. As of 2017, about 8.2 per 1,000 deliveries were estimated to be affected by the disorder. The numbers were particularly high in people insured by Medicaid. In that group, an estimated 14.6 per 1,000 deliveries were affected.

Researchers studied pregnant women enrolled in public insurance programs in the United States from 2000 through 2018 in a dataset of 2,548,372 pregnancies that ended in live births. They analyzed outcomes in those who received buprenorphine as compared with those who received methadone.

They looked at different periods of exposure to the two medications: early pregnancy (through gestational week 19); late pregnancy (week 20 through the day before delivery); and the 30 days before delivery.

Highlighted differences in infants included:

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 52% of the infants who were exposed to buprenorphine in the 30 days before delivery as compared with 69.2% of those exposed to methadone (adjusted relative risk, 0.73).

- Preterm birth in 14.4% of infants exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and in 24.9% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 0.58).

- Small size for gestational age in 12.1% (buprenorphine) and 15.3% (methadone) (ARR, 0.72).

- Low birth weight in 8.3% (buprenorphine) and 14.9% (methadone) (ARR, 0.56).

- Delivery by cesarean section occurred in 33.6% of pregnant women exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and 33.1% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 1.02.).

Severe maternal complications developed in 3.3% of the women exposed to buprenorphine and 3.5% of those on methadone (ARR, 0.91.) Exposures in late pregnancy and early pregnancy yielded similar results, the authors say.

Michael Caucci, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. who also runs the Women’s Mental Health Clinic at the university, said this paper supports preliminary findings from the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER) study that suggested infants exposed to buprenorphine (compared with methadone) appeared to have lower rates of neonatal complications.

“It also supports buprenorphine as a relatively safe option for treatment of opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” said Dr. Caucci, who was not part of the study by Dr. Suarez and associates. “Reducing the fear of harming the fetus or neonate will help eliminate this barrier to perinatal substance use disorder treatment.”

But he cautions against concluding that, because buprenorphine has lower risks of fetal/neonatal complications, it is safer and therefore better than methadone in pregnancy.

“Some women do not tolerate buprenorphine and do much better on methadone, Dr. Caucci said. “Current recommendations are that both buprenorphine and methadone are relatively safe options for treatment of OUD [opioid use disorder] in pregnancy.”

Among the differences between the treatments is that while methadone is administered daily during in-person visits to federally regulated opioid treatment programs, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers, which allows patients to administer buprenorphine themselves.

Dr. Caucci said he was intrigued by the finding that there was no difference in pregnancy, neonatal, and maternal outcomes depending on the time of exposure to the agents.

“I would have expected higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or poor fetal growth in those exposed later in pregnancy vs. those with early exposure,” he said.

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Caucci reports no relevant financial relationships. The authors’ disclosures are available with the full text.

Using buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy was linked with a lower risk of neonatal side effects than using methadone, but the risk of adverse maternal outcomes was similar between the two treatments, according to new research.

Elizabeth A. Suarez, PhD, MPH, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, led the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Opioid use disorder in pregnant women has increased steadily in the United States since 2000, the authors write. As of 2017, about 8.2 per 1,000 deliveries were estimated to be affected by the disorder. The numbers were particularly high in people insured by Medicaid. In that group, an estimated 14.6 per 1,000 deliveries were affected.

Researchers studied pregnant women enrolled in public insurance programs in the United States from 2000 through 2018 in a dataset of 2,548,372 pregnancies that ended in live births. They analyzed outcomes in those who received buprenorphine as compared with those who received methadone.

They looked at different periods of exposure to the two medications: early pregnancy (through gestational week 19); late pregnancy (week 20 through the day before delivery); and the 30 days before delivery.

Highlighted differences in infants included:

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome in 52% of the infants who were exposed to buprenorphine in the 30 days before delivery as compared with 69.2% of those exposed to methadone (adjusted relative risk, 0.73).

- Preterm birth in 14.4% of infants exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and in 24.9% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 0.58).

- Small size for gestational age in 12.1% (buprenorphine) and 15.3% (methadone) (ARR, 0.72).

- Low birth weight in 8.3% (buprenorphine) and 14.9% (methadone) (ARR, 0.56).

- Delivery by cesarean section occurred in 33.6% of pregnant women exposed to buprenorphine in early pregnancy and 33.1% of those exposed to methadone (ARR, 1.02.).

Severe maternal complications developed in 3.3% of the women exposed to buprenorphine and 3.5% of those on methadone (ARR, 0.91.) Exposures in late pregnancy and early pregnancy yielded similar results, the authors say.

Michael Caucci, MD, of the department of psychiatry at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn. who also runs the Women’s Mental Health Clinic at the university, said this paper supports preliminary findings from the Maternal Opioid Treatment: Human Experimental Research (MOTHER) study that suggested infants exposed to buprenorphine (compared with methadone) appeared to have lower rates of neonatal complications.

“It also supports buprenorphine as a relatively safe option for treatment of opioid use disorder during pregnancy,” said Dr. Caucci, who was not part of the study by Dr. Suarez and associates. “Reducing the fear of harming the fetus or neonate will help eliminate this barrier to perinatal substance use disorder treatment.”

But he cautions against concluding that, because buprenorphine has lower risks of fetal/neonatal complications, it is safer and therefore better than methadone in pregnancy.

“Some women do not tolerate buprenorphine and do much better on methadone, Dr. Caucci said. “Current recommendations are that both buprenorphine and methadone are relatively safe options for treatment of OUD [opioid use disorder] in pregnancy.”

Among the differences between the treatments is that while methadone is administered daily during in-person visits to federally regulated opioid treatment programs, buprenorphine can be prescribed by approved providers, which allows patients to administer buprenorphine themselves.

Dr. Caucci said he was intrigued by the finding that there was no difference in pregnancy, neonatal, and maternal outcomes depending on the time of exposure to the agents.

“I would have expected higher rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) or poor fetal growth in those exposed later in pregnancy vs. those with early exposure,” he said.

The work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Caucci reports no relevant financial relationships. The authors’ disclosures are available with the full text.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

HCV reinfection uncommon among people who inject drugs

The findings, which are based on prospective data from 13 countries, including the United States, and were published in Annals of Internal Medicine (2022 Aug 8. doi: 10.7326/M21-4119), should encourage physicians to treat HCV in people with a history of injection drug use, said lead author Jason Grebely, PhD. They should also pressure payers to lift reimbursement restrictions on the same population.

“Direct-acting antiviral medications for HCV infection are safe and effective among people receiving OAT and people with recent injecting-drug use,” the investigators wrote. “Concerns remain, however, that HCV reinfection may reduce the benefits of cure among people who inject drugs and compromise HCV elimination efforts.”

They explored these concerns through a 3-year extension of the phase 3 CO-STAR trial that evaluated elbasvir and grazoprevir in people consistently taking OAT. Participants in the CO-STAR trial, which had a 96% sustained virologic response rate among those who completed therapy, could elect to participate in the present study, offering a prospective look at long-term reinfection.