User login

Commentary to "Patient-Specific Imaging and Missed Tumors: A Catastrophic Outcome"

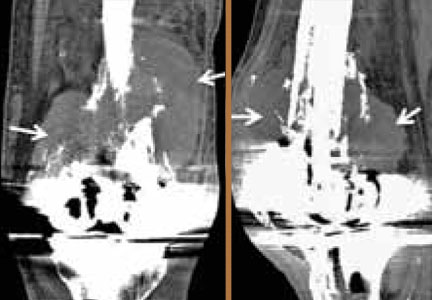

The idiom “penny wise, pound foolish” certainly applies in this report of 2 cases of missed bone tumors that were present but not recognized on preoperative imaging prior to placement of patient-specific knee arthroplasties. The case report appeared in the December 2013 issue of The American Journal of Orthopedics. The term “non-diagnostic imaging,” itself a paradox, used in the context of preoperative imaging performed solely for the purpose of component templating for patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) and not intended to be diagnostic in purpose, would be anathematic to most radiologists and should be discarded as a concept.

Bearing in mind the costs incurred by the patient undergoing a total knee arthroplasty (TKA), such as professional consultation, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging, customized manufacture of the components, surgery and associated costs, and postoperative rehabilitation, the fee for a formal report by a musculoskeletal radiologist is comparatively minuscule. As correctly pointed out by the authors, the price associated with bypassing any assessment and missing malignant disease is far greater.

It is well recognized that unreported radiologic examinations can lead to misdiagnosis, compromised patient care, and liability concerns. As PSI is relatively new and has good potential to increase the accuracy, precision and efficiency of TKA, it is even more vital that this promising technology not be marred by disrepute due to possible devastating outcomes resulting from lack of a radiologic report. From the professional point of view of a radiologist, the issuance of a formal report is part and parcel of any radiological examination. I would argue that obtaining radiologic images without an accompanying report constitutes an incomplete study, and will not be in the best interest of patients.

Let the lessons learned from these 2 cases be a springboard to establish protocols for proper utilization of technologies involved in PSI for TKA and other orthopedic procedures. It is imperative to put into place mandatory reporting of all diagnostic images obtained for preoperative evaluation, particularly those that are meant to be sent directly to implant manufacturers for component design.

Menge TJ, Hartley KG, Holt GE. Patient-Specific Imaging and Missed Tumors: A Catastrophic Outcome. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(12):553-556.

The idiom “penny wise, pound foolish” certainly applies in this report of 2 cases of missed bone tumors that were present but not recognized on preoperative imaging prior to placement of patient-specific knee arthroplasties. The case report appeared in the December 2013 issue of The American Journal of Orthopedics. The term “non-diagnostic imaging,” itself a paradox, used in the context of preoperative imaging performed solely for the purpose of component templating for patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) and not intended to be diagnostic in purpose, would be anathematic to most radiologists and should be discarded as a concept.

Bearing in mind the costs incurred by the patient undergoing a total knee arthroplasty (TKA), such as professional consultation, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging, customized manufacture of the components, surgery and associated costs, and postoperative rehabilitation, the fee for a formal report by a musculoskeletal radiologist is comparatively minuscule. As correctly pointed out by the authors, the price associated with bypassing any assessment and missing malignant disease is far greater.

It is well recognized that unreported radiologic examinations can lead to misdiagnosis, compromised patient care, and liability concerns. As PSI is relatively new and has good potential to increase the accuracy, precision and efficiency of TKA, it is even more vital that this promising technology not be marred by disrepute due to possible devastating outcomes resulting from lack of a radiologic report. From the professional point of view of a radiologist, the issuance of a formal report is part and parcel of any radiological examination. I would argue that obtaining radiologic images without an accompanying report constitutes an incomplete study, and will not be in the best interest of patients.

Let the lessons learned from these 2 cases be a springboard to establish protocols for proper utilization of technologies involved in PSI for TKA and other orthopedic procedures. It is imperative to put into place mandatory reporting of all diagnostic images obtained for preoperative evaluation, particularly those that are meant to be sent directly to implant manufacturers for component design.

Menge TJ, Hartley KG, Holt GE. Patient-Specific Imaging and Missed Tumors: A Catastrophic Outcome. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(12):553-556.

The idiom “penny wise, pound foolish” certainly applies in this report of 2 cases of missed bone tumors that were present but not recognized on preoperative imaging prior to placement of patient-specific knee arthroplasties. The case report appeared in the December 2013 issue of The American Journal of Orthopedics. The term “non-diagnostic imaging,” itself a paradox, used in the context of preoperative imaging performed solely for the purpose of component templating for patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) and not intended to be diagnostic in purpose, would be anathematic to most radiologists and should be discarded as a concept.

Bearing in mind the costs incurred by the patient undergoing a total knee arthroplasty (TKA), such as professional consultation, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging, customized manufacture of the components, surgery and associated costs, and postoperative rehabilitation, the fee for a formal report by a musculoskeletal radiologist is comparatively minuscule. As correctly pointed out by the authors, the price associated with bypassing any assessment and missing malignant disease is far greater.

It is well recognized that unreported radiologic examinations can lead to misdiagnosis, compromised patient care, and liability concerns. As PSI is relatively new and has good potential to increase the accuracy, precision and efficiency of TKA, it is even more vital that this promising technology not be marred by disrepute due to possible devastating outcomes resulting from lack of a radiologic report. From the professional point of view of a radiologist, the issuance of a formal report is part and parcel of any radiological examination. I would argue that obtaining radiologic images without an accompanying report constitutes an incomplete study, and will not be in the best interest of patients.

Let the lessons learned from these 2 cases be a springboard to establish protocols for proper utilization of technologies involved in PSI for TKA and other orthopedic procedures. It is imperative to put into place mandatory reporting of all diagnostic images obtained for preoperative evaluation, particularly those that are meant to be sent directly to implant manufacturers for component design.

Menge TJ, Hartley KG, Holt GE. Patient-Specific Imaging and Missed Tumors: A Catastrophic Outcome. Am J Orthop. 2013;42(12):553-556.

Will the New Milestone Requirements Improve Residency Training?

Patient-Specific Imaging and Missed Tumors: A Catastrophic Outcome

Accuracy and Safety of the Placement of Thoracic and Lumbar Pedicle Screws Using the O-arm Intraoperative Computed Tomography System and Stealth Stereotactic Guidance

Navigation in Total Knee Arthroplasty: Truth, Myths, and Controversies

The overall success of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) depends on proper implant choice, meticulous surgical technique, appropriate patient selection, and

effective postoperative rehabilitation. Inappropriate technique leads to suboptimal placement of implants in coronal, sagittal, or axial planes.1-3 This results in eccentric prosthetic loading, which may contribute to accelerated polyethylene wear, early component loosening, higher rates of revision surgery, and unsatisfactory clinical outcomes. The need to optimize component positioning during TKA stimulated the development of computer-assisted navigation in TKA in the late 1990’s. Proponents of this technology believe that it helps to reduce outliers, improves coronal, sagittal, and rotational alignment, and optimizes flexion and extension gap-balancing. This is believed to result in improved implant survival and better functional outcomes. However, despite these postulated advantages, less than 5% of surgeons in the United States currently use navigation during TKA perhaps due to concerns of costs, increased operating time, learn- ing curve issues, and lack of improvement in functional outcomes at mid-term follow-up.

Navigated TKA, due to its accuracy and low margins of error, has the potential to reduce component malalignment to within 1o to 2o of neutral mechanical axis.4 However, others have reported that alignment of the femoral and tibial components achieved with computer navigation is not different than TKA using conventional techniques.5-12 This lack of improvement reported in these studies may be due to a number of potential sources of errors, which can be either surgeon- or device-related. These errors may pre-dispose to discrepancies between alignments calculated by the computer and the actual position of the implants. Apart from software- and hardware-related calibration issues, the majority of inaccuracies, which are often surgeon-related, result from registration of anatomical landmarks, pin array movements after registration, incorrect bone cuts despite accurate jig placement, and incorrect placement of final components during cementation. Of these surgeon-related factors, variability in the identification of the anatomical landmarks appears to be critical and occurs due to anatomical variations or from inaccurate recognition of intraoperative bony landmarks. A recent study found that registration of the distal femoral epicondyles was more likely to be inaccurate than other anatomical landmarks, as it was found that a small change of 2 mm in the sagittal plane can lead to a 1o change in the femoral component rotation.13

Nevertheless, the general consensus from recent high- level evidence (Level I and II) suggests that navigated TKA leads to improved coronal-alignment outcomes and reduced numbers of outliers.14-18 In a recent systematic review of 27 randomized controlled trials of 2541 patients, Hetaimish and colleagues19 compared the alignment outcomes of navigated with conventional TKA. The authors found that the navigated cohort had a significantly lower risk of producing a mechanical axis deviation of greater than 3o, compared with conventional TKA (relative risk [RR] = 0.37; P<.001). The femoral and tibial, coronal and sagittal malalignment (>3o) were also found to be significantly lower with navigated TKA, compared with conventional techniques. However, no substantial differences were found in the rotation alignment of the femoral component between the 2 comparison cohorts (navigated group, 18.8%; conventional group, 14.5%).

Advocates of navigation believe that improved component alignment would lead to better functional outcomes and lower revision rates.20,21 However, at short- to mid-term follow-up, most studies have failed to show any substantial benefits in terms of functional outcomes, revision rates, patient satisfaction, or patient-perceived quality-of-life, when comparing computer-assisted navigation to conventional techniques.11,22-25 Recent systematic reviews by Zamora et al24 and Burnett et al25 found no significant differences in the functional outcomes between navigated and conventional TKA (P>.05). This lack of the expected improvement in functional outcomes reported in various studies with navigation could be due to variability in registration of anatomical landmarks leading to errors in the rotational axis, or a lack of complete understanding of the interplay of alignment, ligament balance, in vivo joint loading and kinematics. In a report from the Mayo Clinic,26 the authors believed that there may be little practical value in relying on a mechanical alignment of ±3o from neutral as an isolated variable in predicting the longevity of modern TKA. In addition, they suggested that factors apart from mechanical alignment may have a more profound impact on implant durability.

Several studies27-31 that compared the joint line changes or ligament balance between navigated and conventional TKA, report no substantial differences in the maintenance of the joint line, quality of life, and functional outcomes. Despite claims of decreased blood loss, length-of stay, cardiac complications, and lower risks of fat embolism with computer-assisted navigation by some authors, other reports have failed to demonstrate any substantial advantages, therefore, it is controversial if any clear benefit exists.6,32-34 It is postulated that the high initial institutional costs of navigation can even out in the long run if the goals of improved survivorship and functional outcomes are achieved.35 However, as mid-term follow-up studies have failed to show a survival or functional benefit, the purported costs savings from computer navigation may not be accurate. Navigated TKA has been reported to increase operative time by about 15 to 20 minutes, compared with conventional TKA. Although, this increases operative time, it has not been reported to increase the risk of deep prosthetic joint infections.

Navigation provides some benefits in terms of radiological alignment. However, the clinical advantages are yet to be defined. Currently, there are many unanswered ques- tions concerning alignment in TKA, such as having a more individual approach based on the patients’ own anatomic variations including considerations about the presence of constitutional varus in patients. Navigation may have a role when TKA is performed for complex deformities, fractures, or in the presence of retained implants that prevent the use of conventional guides. Nevertheless, one should always keep in mind cost considerations. This has been true with any technological advancement we have had in the past and will be of concern in the future as well, especially with rising healthcare costs. When analyzing costs with naviga- tion, one must take in to account not only the overall costs of technology, but also the added costs of training, increased operating room times, and disposables when performing these procedures. Although we are advocates of change and are excited about this technology, the cost-benefit ratio for computer navigated TKA needs to be reconciled.

The overall success of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) depends on proper implant choice, meticulous surgical technique, appropriate patient selection, and

effective postoperative rehabilitation. Inappropriate technique leads to suboptimal placement of implants in coronal, sagittal, or axial planes.1-3 This results in eccentric prosthetic loading, which may contribute to accelerated polyethylene wear, early component loosening, higher rates of revision surgery, and unsatisfactory clinical outcomes. The need to optimize component positioning during TKA stimulated the development of computer-assisted navigation in TKA in the late 1990’s. Proponents of this technology believe that it helps to reduce outliers, improves coronal, sagittal, and rotational alignment, and optimizes flexion and extension gap-balancing. This is believed to result in improved implant survival and better functional outcomes. However, despite these postulated advantages, less than 5% of surgeons in the United States currently use navigation during TKA perhaps due to concerns of costs, increased operating time, learn- ing curve issues, and lack of improvement in functional outcomes at mid-term follow-up.

Navigated TKA, due to its accuracy and low margins of error, has the potential to reduce component malalignment to within 1o to 2o of neutral mechanical axis.4 However, others have reported that alignment of the femoral and tibial components achieved with computer navigation is not different than TKA using conventional techniques.5-12 This lack of improvement reported in these studies may be due to a number of potential sources of errors, which can be either surgeon- or device-related. These errors may pre-dispose to discrepancies between alignments calculated by the computer and the actual position of the implants. Apart from software- and hardware-related calibration issues, the majority of inaccuracies, which are often surgeon-related, result from registration of anatomical landmarks, pin array movements after registration, incorrect bone cuts despite accurate jig placement, and incorrect placement of final components during cementation. Of these surgeon-related factors, variability in the identification of the anatomical landmarks appears to be critical and occurs due to anatomical variations or from inaccurate recognition of intraoperative bony landmarks. A recent study found that registration of the distal femoral epicondyles was more likely to be inaccurate than other anatomical landmarks, as it was found that a small change of 2 mm in the sagittal plane can lead to a 1o change in the femoral component rotation.13

Nevertheless, the general consensus from recent high- level evidence (Level I and II) suggests that navigated TKA leads to improved coronal-alignment outcomes and reduced numbers of outliers.14-18 In a recent systematic review of 27 randomized controlled trials of 2541 patients, Hetaimish and colleagues19 compared the alignment outcomes of navigated with conventional TKA. The authors found that the navigated cohort had a significantly lower risk of producing a mechanical axis deviation of greater than 3o, compared with conventional TKA (relative risk [RR] = 0.37; P<.001). The femoral and tibial, coronal and sagittal malalignment (>3o) were also found to be significantly lower with navigated TKA, compared with conventional techniques. However, no substantial differences were found in the rotation alignment of the femoral component between the 2 comparison cohorts (navigated group, 18.8%; conventional group, 14.5%).

Advocates of navigation believe that improved component alignment would lead to better functional outcomes and lower revision rates.20,21 However, at short- to mid-term follow-up, most studies have failed to show any substantial benefits in terms of functional outcomes, revision rates, patient satisfaction, or patient-perceived quality-of-life, when comparing computer-assisted navigation to conventional techniques.11,22-25 Recent systematic reviews by Zamora et al24 and Burnett et al25 found no significant differences in the functional outcomes between navigated and conventional TKA (P>.05). This lack of the expected improvement in functional outcomes reported in various studies with navigation could be due to variability in registration of anatomical landmarks leading to errors in the rotational axis, or a lack of complete understanding of the interplay of alignment, ligament balance, in vivo joint loading and kinematics. In a report from the Mayo Clinic,26 the authors believed that there may be little practical value in relying on a mechanical alignment of ±3o from neutral as an isolated variable in predicting the longevity of modern TKA. In addition, they suggested that factors apart from mechanical alignment may have a more profound impact on implant durability.

Several studies27-31 that compared the joint line changes or ligament balance between navigated and conventional TKA, report no substantial differences in the maintenance of the joint line, quality of life, and functional outcomes. Despite claims of decreased blood loss, length-of stay, cardiac complications, and lower risks of fat embolism with computer-assisted navigation by some authors, other reports have failed to demonstrate any substantial advantages, therefore, it is controversial if any clear benefit exists.6,32-34 It is postulated that the high initial institutional costs of navigation can even out in the long run if the goals of improved survivorship and functional outcomes are achieved.35 However, as mid-term follow-up studies have failed to show a survival or functional benefit, the purported costs savings from computer navigation may not be accurate. Navigated TKA has been reported to increase operative time by about 15 to 20 minutes, compared with conventional TKA. Although, this increases operative time, it has not been reported to increase the risk of deep prosthetic joint infections.

Navigation provides some benefits in terms of radiological alignment. However, the clinical advantages are yet to be defined. Currently, there are many unanswered ques- tions concerning alignment in TKA, such as having a more individual approach based on the patients’ own anatomic variations including considerations about the presence of constitutional varus in patients. Navigation may have a role when TKA is performed for complex deformities, fractures, or in the presence of retained implants that prevent the use of conventional guides. Nevertheless, one should always keep in mind cost considerations. This has been true with any technological advancement we have had in the past and will be of concern in the future as well, especially with rising healthcare costs. When analyzing costs with naviga- tion, one must take in to account not only the overall costs of technology, but also the added costs of training, increased operating room times, and disposables when performing these procedures. Although we are advocates of change and are excited about this technology, the cost-benefit ratio for computer navigated TKA needs to be reconciled.

The overall success of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) depends on proper implant choice, meticulous surgical technique, appropriate patient selection, and

effective postoperative rehabilitation. Inappropriate technique leads to suboptimal placement of implants in coronal, sagittal, or axial planes.1-3 This results in eccentric prosthetic loading, which may contribute to accelerated polyethylene wear, early component loosening, higher rates of revision surgery, and unsatisfactory clinical outcomes. The need to optimize component positioning during TKA stimulated the development of computer-assisted navigation in TKA in the late 1990’s. Proponents of this technology believe that it helps to reduce outliers, improves coronal, sagittal, and rotational alignment, and optimizes flexion and extension gap-balancing. This is believed to result in improved implant survival and better functional outcomes. However, despite these postulated advantages, less than 5% of surgeons in the United States currently use navigation during TKA perhaps due to concerns of costs, increased operating time, learn- ing curve issues, and lack of improvement in functional outcomes at mid-term follow-up.

Navigated TKA, due to its accuracy and low margins of error, has the potential to reduce component malalignment to within 1o to 2o of neutral mechanical axis.4 However, others have reported that alignment of the femoral and tibial components achieved with computer navigation is not different than TKA using conventional techniques.5-12 This lack of improvement reported in these studies may be due to a number of potential sources of errors, which can be either surgeon- or device-related. These errors may pre-dispose to discrepancies between alignments calculated by the computer and the actual position of the implants. Apart from software- and hardware-related calibration issues, the majority of inaccuracies, which are often surgeon-related, result from registration of anatomical landmarks, pin array movements after registration, incorrect bone cuts despite accurate jig placement, and incorrect placement of final components during cementation. Of these surgeon-related factors, variability in the identification of the anatomical landmarks appears to be critical and occurs due to anatomical variations or from inaccurate recognition of intraoperative bony landmarks. A recent study found that registration of the distal femoral epicondyles was more likely to be inaccurate than other anatomical landmarks, as it was found that a small change of 2 mm in the sagittal plane can lead to a 1o change in the femoral component rotation.13

Nevertheless, the general consensus from recent high- level evidence (Level I and II) suggests that navigated TKA leads to improved coronal-alignment outcomes and reduced numbers of outliers.14-18 In a recent systematic review of 27 randomized controlled trials of 2541 patients, Hetaimish and colleagues19 compared the alignment outcomes of navigated with conventional TKA. The authors found that the navigated cohort had a significantly lower risk of producing a mechanical axis deviation of greater than 3o, compared with conventional TKA (relative risk [RR] = 0.37; P<.001). The femoral and tibial, coronal and sagittal malalignment (>3o) were also found to be significantly lower with navigated TKA, compared with conventional techniques. However, no substantial differences were found in the rotation alignment of the femoral component between the 2 comparison cohorts (navigated group, 18.8%; conventional group, 14.5%).

Advocates of navigation believe that improved component alignment would lead to better functional outcomes and lower revision rates.20,21 However, at short- to mid-term follow-up, most studies have failed to show any substantial benefits in terms of functional outcomes, revision rates, patient satisfaction, or patient-perceived quality-of-life, when comparing computer-assisted navigation to conventional techniques.11,22-25 Recent systematic reviews by Zamora et al24 and Burnett et al25 found no significant differences in the functional outcomes between navigated and conventional TKA (P>.05). This lack of the expected improvement in functional outcomes reported in various studies with navigation could be due to variability in registration of anatomical landmarks leading to errors in the rotational axis, or a lack of complete understanding of the interplay of alignment, ligament balance, in vivo joint loading and kinematics. In a report from the Mayo Clinic,26 the authors believed that there may be little practical value in relying on a mechanical alignment of ±3o from neutral as an isolated variable in predicting the longevity of modern TKA. In addition, they suggested that factors apart from mechanical alignment may have a more profound impact on implant durability.

Several studies27-31 that compared the joint line changes or ligament balance between navigated and conventional TKA, report no substantial differences in the maintenance of the joint line, quality of life, and functional outcomes. Despite claims of decreased blood loss, length-of stay, cardiac complications, and lower risks of fat embolism with computer-assisted navigation by some authors, other reports have failed to demonstrate any substantial advantages, therefore, it is controversial if any clear benefit exists.6,32-34 It is postulated that the high initial institutional costs of navigation can even out in the long run if the goals of improved survivorship and functional outcomes are achieved.35 However, as mid-term follow-up studies have failed to show a survival or functional benefit, the purported costs savings from computer navigation may not be accurate. Navigated TKA has been reported to increase operative time by about 15 to 20 minutes, compared with conventional TKA. Although, this increases operative time, it has not been reported to increase the risk of deep prosthetic joint infections.

Navigation provides some benefits in terms of radiological alignment. However, the clinical advantages are yet to be defined. Currently, there are many unanswered ques- tions concerning alignment in TKA, such as having a more individual approach based on the patients’ own anatomic variations including considerations about the presence of constitutional varus in patients. Navigation may have a role when TKA is performed for complex deformities, fractures, or in the presence of retained implants that prevent the use of conventional guides. Nevertheless, one should always keep in mind cost considerations. This has been true with any technological advancement we have had in the past and will be of concern in the future as well, especially with rising healthcare costs. When analyzing costs with naviga- tion, one must take in to account not only the overall costs of technology, but also the added costs of training, increased operating room times, and disposables when performing these procedures. Although we are advocates of change and are excited about this technology, the cost-benefit ratio for computer navigated TKA needs to be reconciled.