User login

Humeral Bone Loss in Revision Shoulder Arthroplasty

ABSTRACT

Revision shoulder arthroplasty is becoming more prevalent as the rate of primary shoulder arthroplasty in the US continues to increase. The management of proximal humeral bone loss in the revision setting presents a difficult problem without a clear solution. Different preoperative diagnoses often lead to distinctly different patterns of bone loss. Successful management of these cases requires a clear understanding of the normal anatomy of the proximal humerus, as well as structural limitations imposed by significant bone loss and the effect this loss has on component fixation. Our preferred technique differs depending on the pattern of bone loss encountered. The use of allograft-prosthetic composites, the cement-within-cement technique, and combinations of these strategies comprise the mainstay of our treatment algorithm. This article focuses on indications, surgical techniques, and some of the published outcomes using these strategies in the management of proximal humeral bone loss.

Continue to: The demand for shoulder arthroplasty...

The demand for shoulder arthroplasty (SA) has increased significantly over the past decade, with a 200% increase witnessed from 2011 to 2015.1 SA performed in patients younger than 55 years is expected to increase 333% between 2011 to 2030.2 With increasing rates of SA being performed in younger patient populations, rates of revision SA also can be expected to climb. Revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) has arisen as a viable option in these patients, and multiple studies demonstrate excellent outcomes that can be obtained with RSA.3-11

Despite significant improvements obtained in revision SA since the mainstream acceptance of RSA, bone loss remains a problematic issue. Loss of humeral bone stock, in particular, can be a challenging problem to solve with multiple clinical implications. Biomechanical studies have demonstrated that if bone loss is left unaddressed, increased bending and torsional forces on the prosthesis result, which ultimately contribute to increased micromotion and eventual component failure.12 In addition, existing challenges are associated with the lack of attachment sites for both multiple muscles and tendons. Also, there is a loss of the normal lateralized pull of the deltoid, which results in a decreased amount of force generated by this muscle.13,14 Ultimately, the increased loss of bone can lead to a devastating situation where there is not enough bone to provide adequate fixation while maintaining the appropriate humeral length necessary to achieve stability of the articulation, which will inevitably lead to instability.4,15 Therefore, techniques are needed to address proximal humeral bone loss while maintaining as much native humeral bone as possible.

PROXIMAL HUMERUS: ANATOMICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The anatomy of the proximal humerus has been studied in great detail and reported in a number of different studies.16-23 The average humeral head thickness (24 mm in men and 19 mm in women) and offset relative to the humeral shaft (2.1 mm posterior and 6.6 mm medial) act to tension the rotator cuff musculature appropriately and contribute to a wrapping effect that allows the deltoid to function more effectively.13,14 Knowledge regarding the rotator cuff footprint has advanced over the past 10 years, specifically with regard to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus.24 The current belief is that the supraspinatus has a triangular insertion onto the most anterior aspect of the greater tuberosity, with a maximum medial-to-lateral length of 6.9 mm and a maximum anterior-to-posterior width of 12.6 mm. The infraspinatus insertion has a trapezoidal insertion, with a maximum medial-to-lateral length of 10.2 mm and anterior-to-posterior width of 32.7 mm. The subscapularis, by far the largest of all the rotator cuff muscles, has a complex geometry with regard to its insertion on the lesser tuberosity, with 4 different insertion points and an overall lateral footprint measuring 37.6 mm and a medial footprint measuring 40.7 mm.25 Finally, the teres minor, with the smallest volume of all the rotator cuff muscles, inserts immediately inferior to the infraspinatus along the inferior facet of the greater tuberosity.26

Aside from the rotator cuff, there are various other muscles and tendons that insert about the proximal humerus and are essential for normal function. The deltoid, which inserts at a point approximately 6 cm from the greater tuberosity along the length of the humerus, with an insertion length between 5 cm to 7 cm,13,27 is the primary mover of the shoulder and essential for proper function after RSA.28,29 The pectoralis major tendon, which begins inserting at a point approximately 5.6 cm from the humeral head and spans a distance of 7.7 cm along the length of the humerus,30-32 is important not only for function but as an anatomical landmark in reconstruction. Lastly, the latissimus dorsi and teres major, which share a role in extension, adduction, and internal rotation of the glenohumeral joint, insert along the floor and medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus, respectively.33,34 In addition to their role in tendon transfer procedures because of treating irreparable posterosuperior cuff and subscapularis tears,35,36 it has been suggested that these tendons may play some role in glenohumeral joint stability.37

In addition to the loss of muscular attachments, the absence of proximal humeral bone stock, in and of itself, can have deleterious effects on fixation of the humeral component. RSA is a semiconstrained device, which results in increased transmission of forces to the interface between the humeral implant and its surrounding structures, including cement (when present) and the bone itself. When there is the absence of significant amounts of bone, the remaining bone must now account for an even higher proportion of these forces. A previous biomechanical study showed that cemented humeral stems demonstrated significantly increased micromotion in the presence of proximal humeral bone loss, particularly when a modular humeral component was used.12

Continue to: TYPES OF BONE LOSS

TYPES OF BONE LOSS

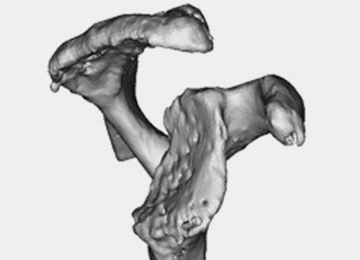

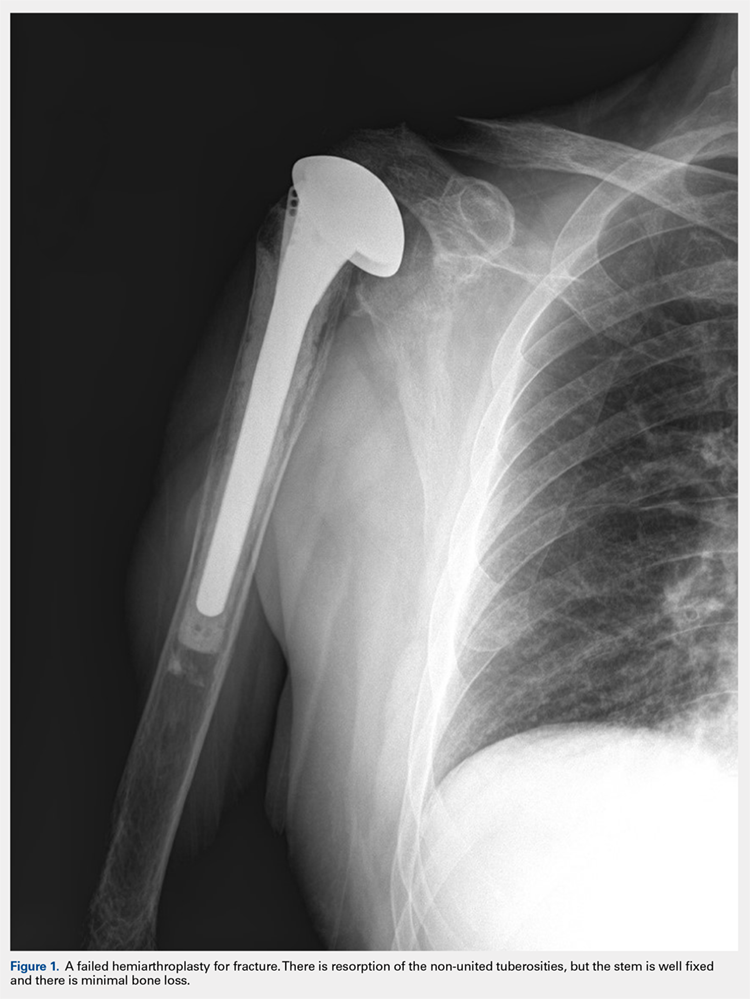

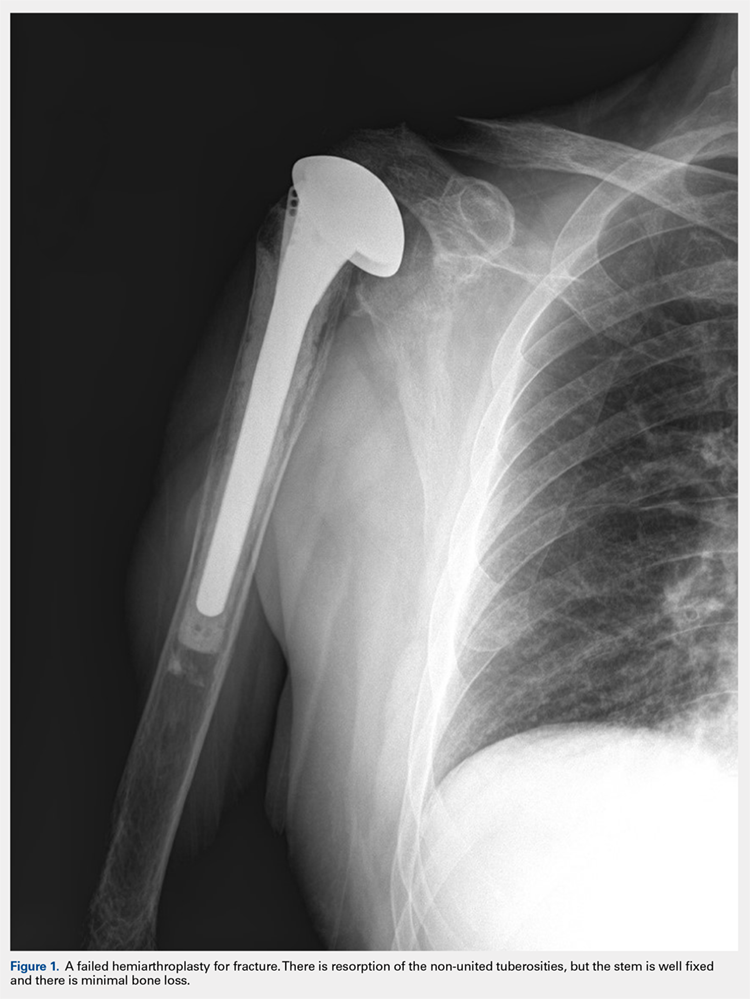

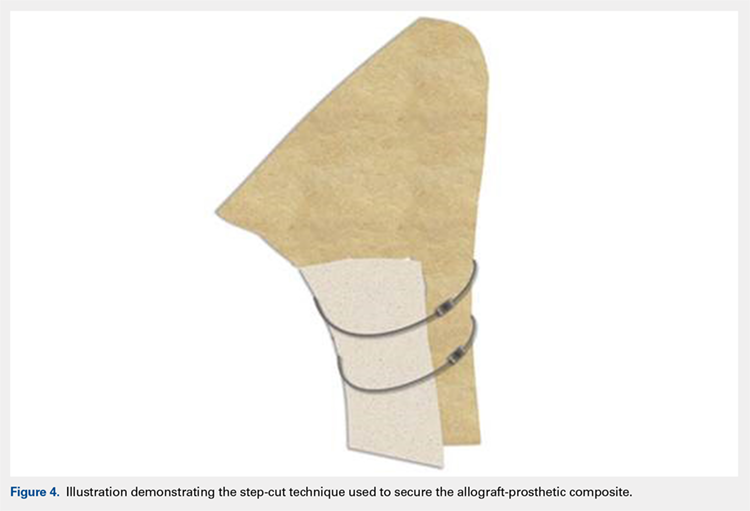

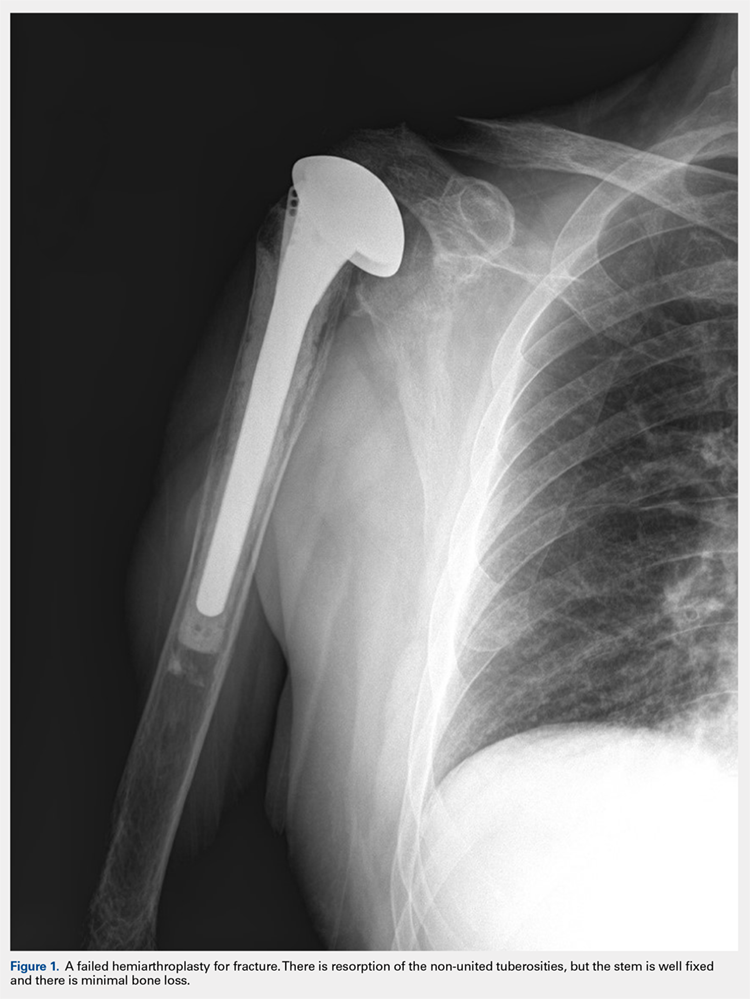

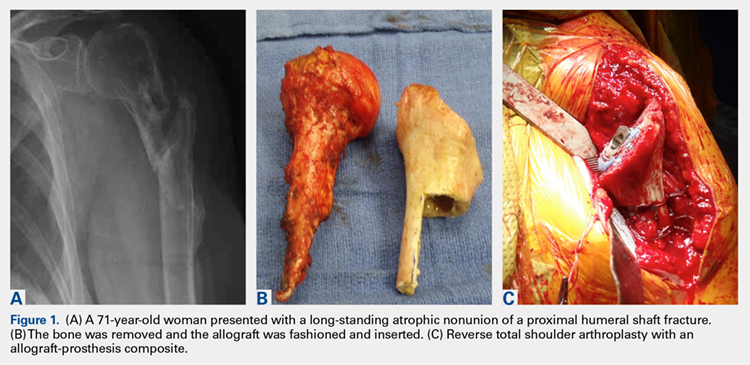

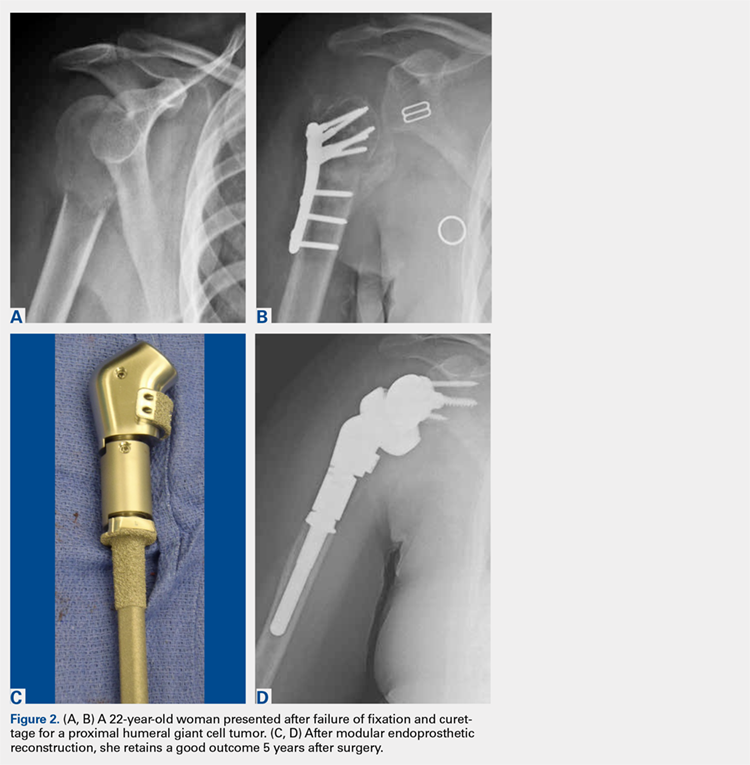

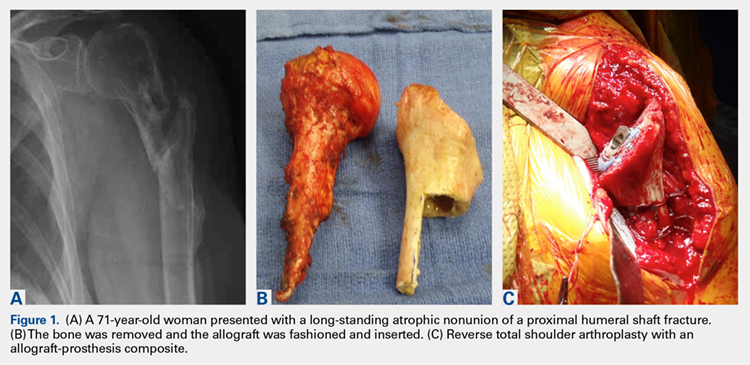

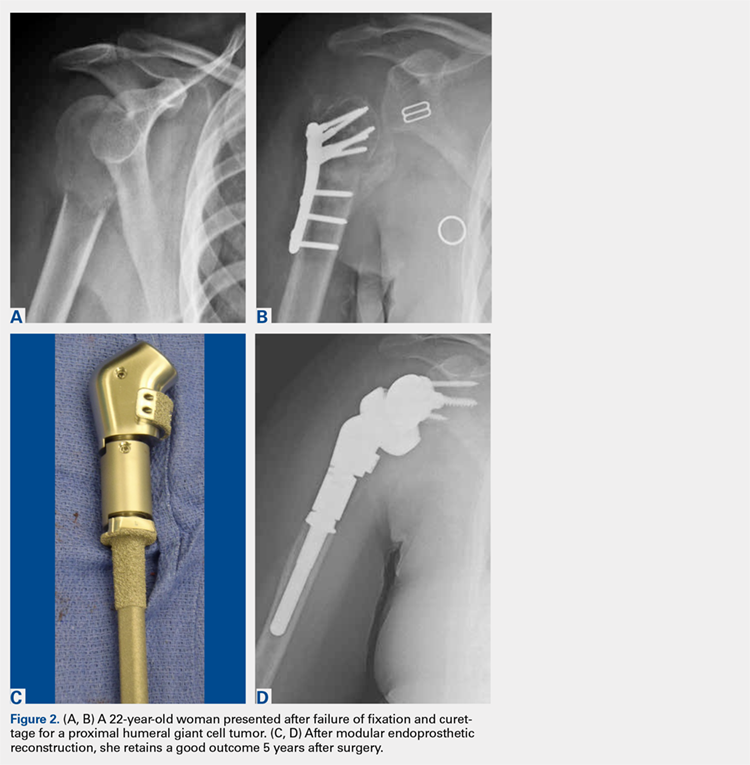

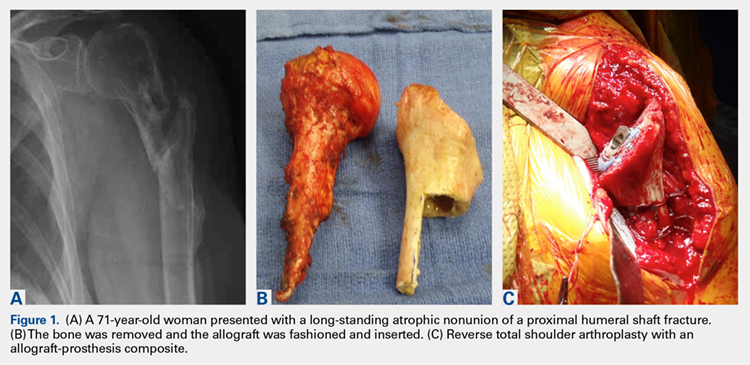

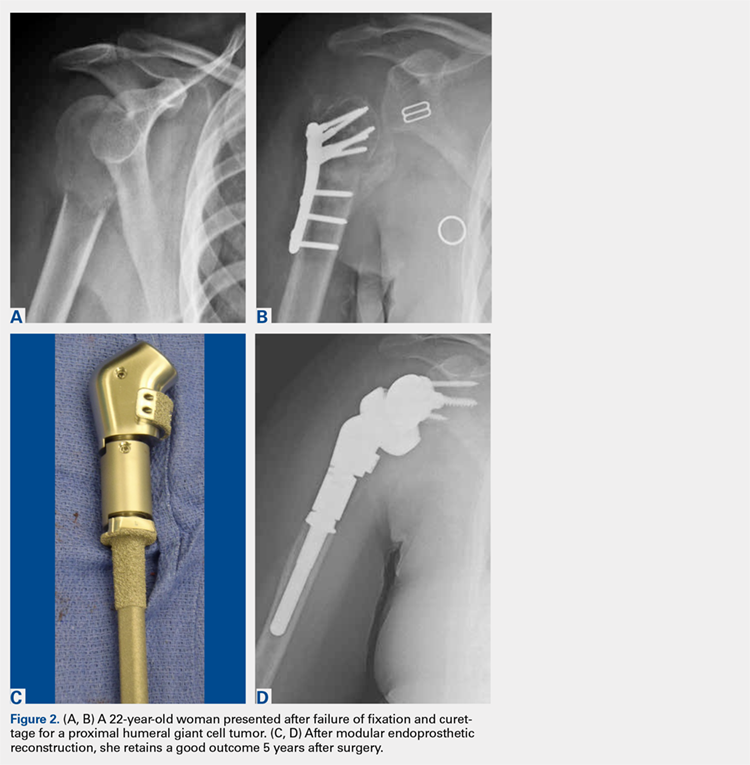

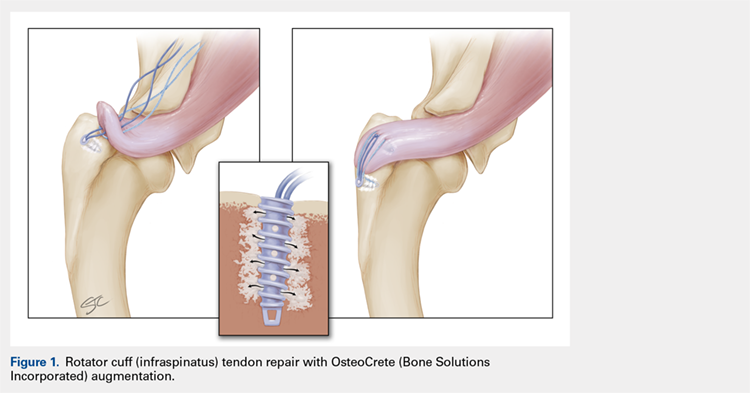

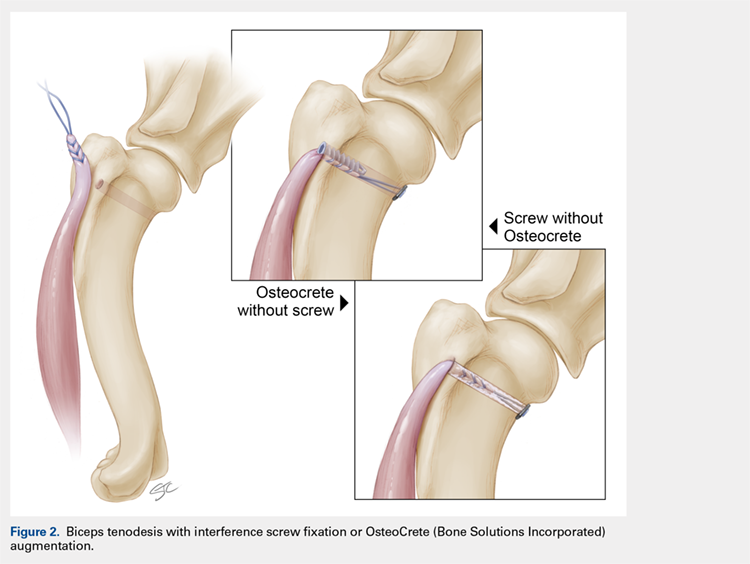

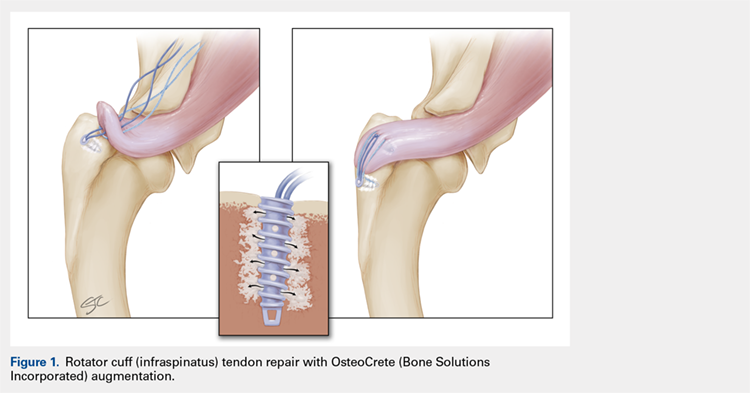

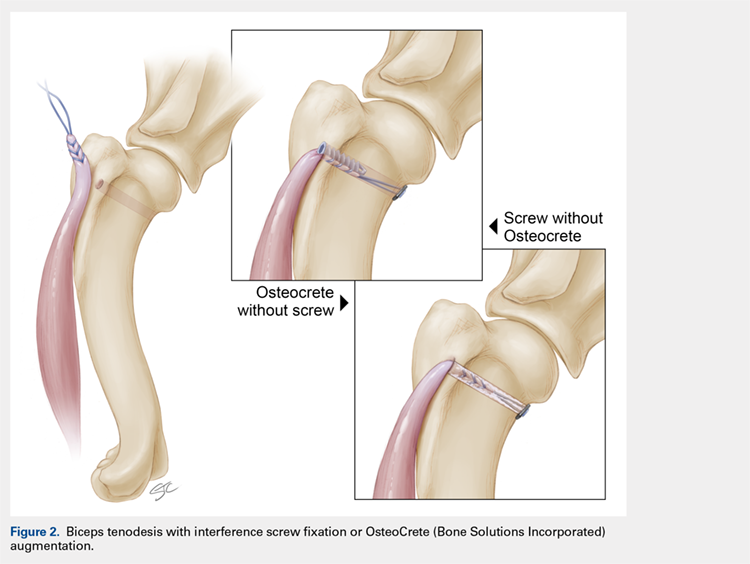

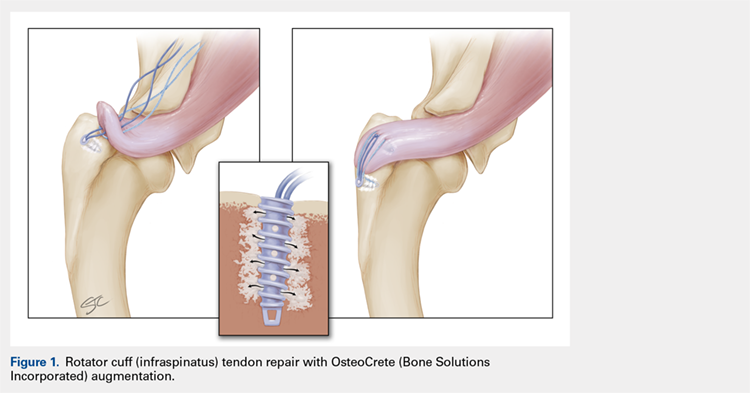

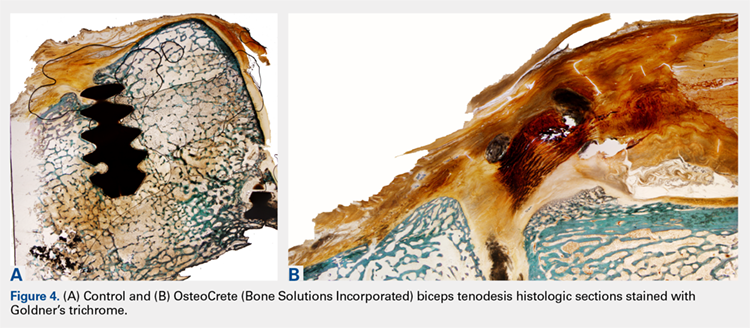

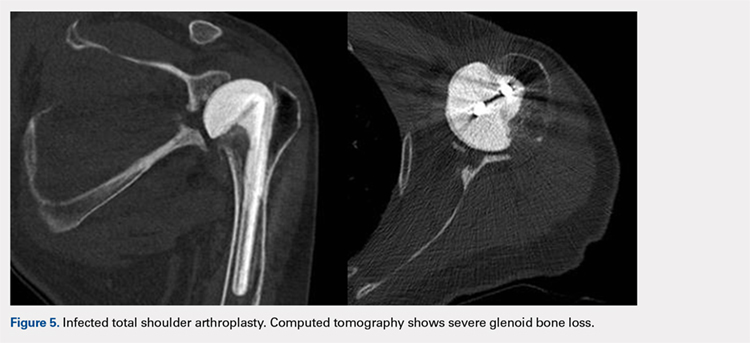

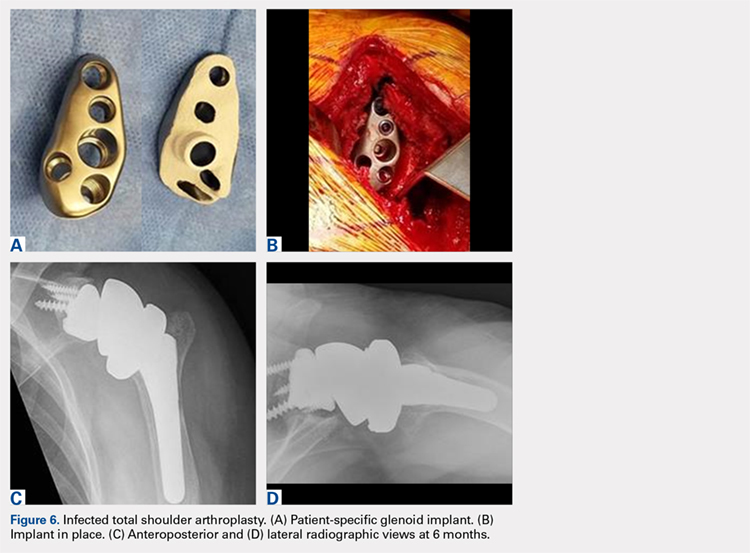

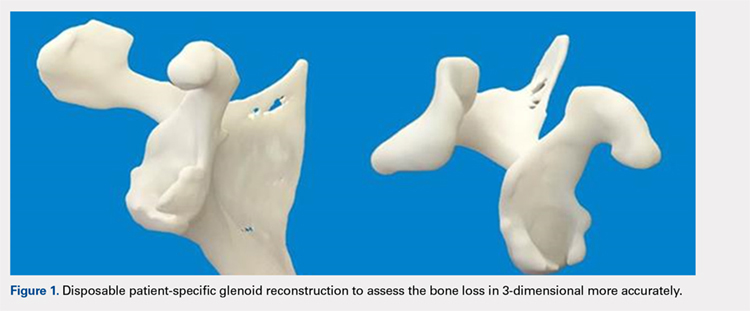

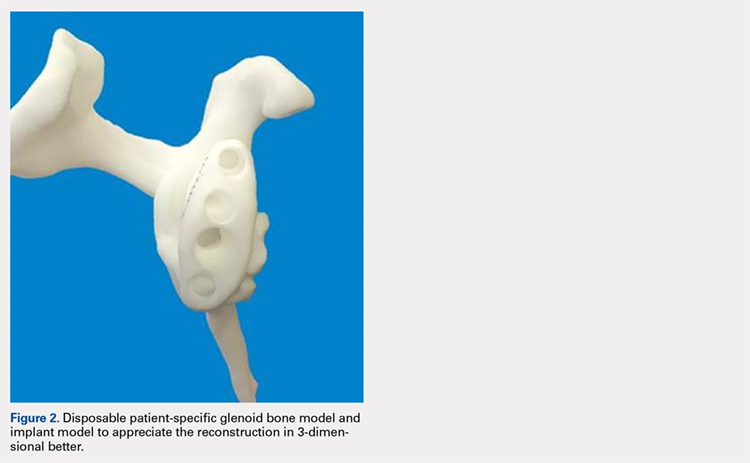

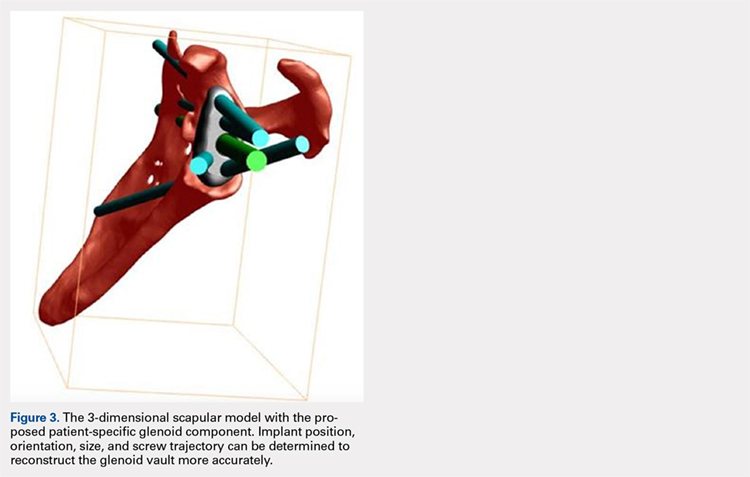

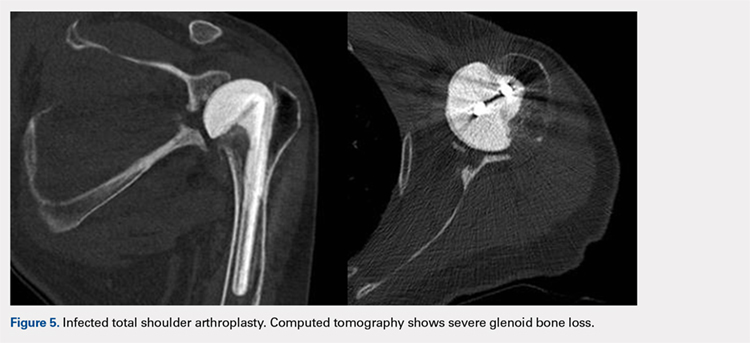

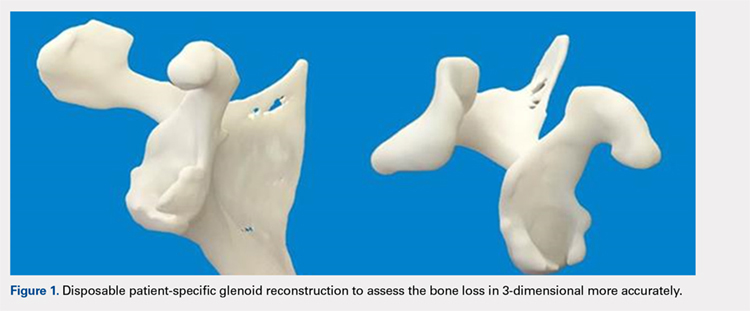

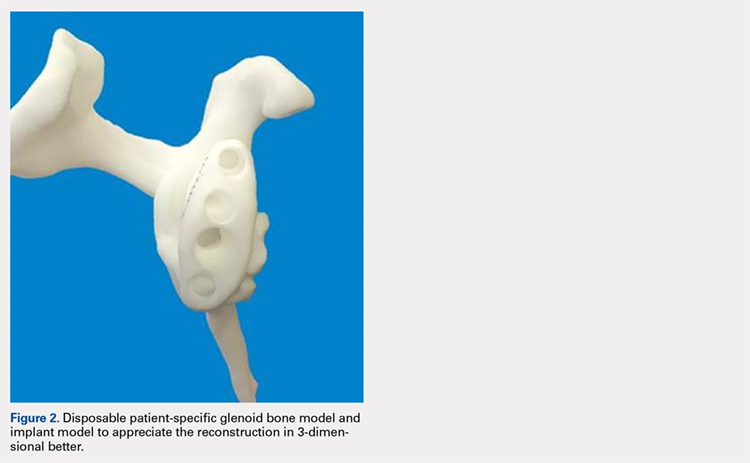

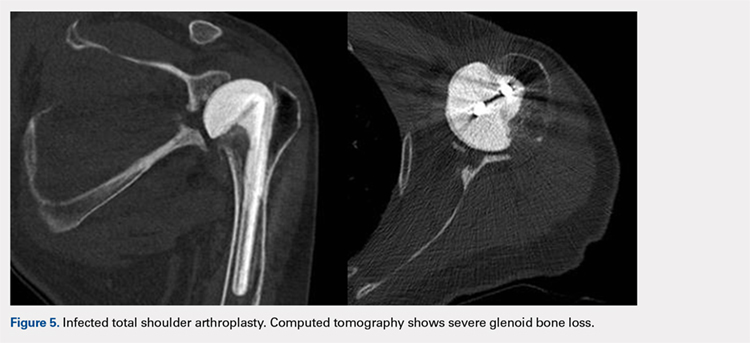

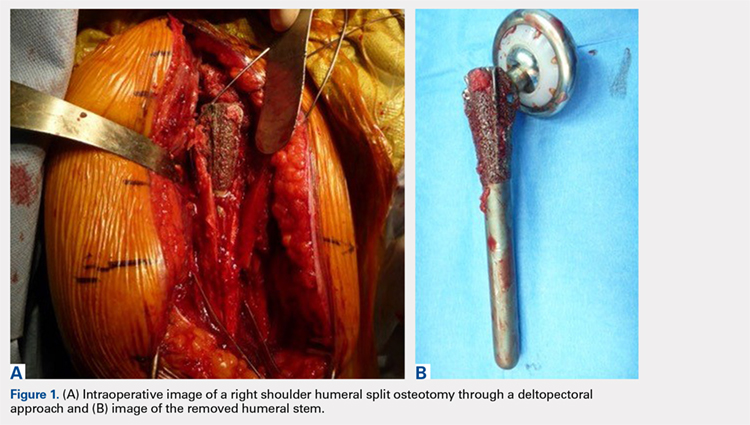

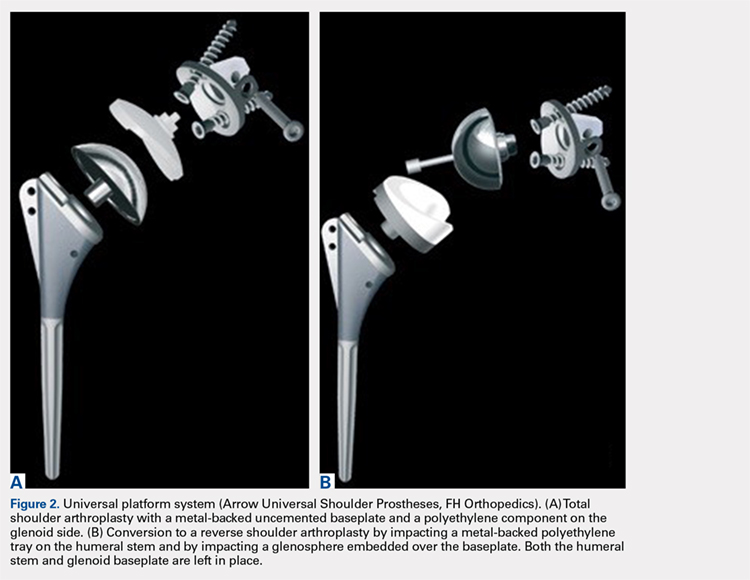

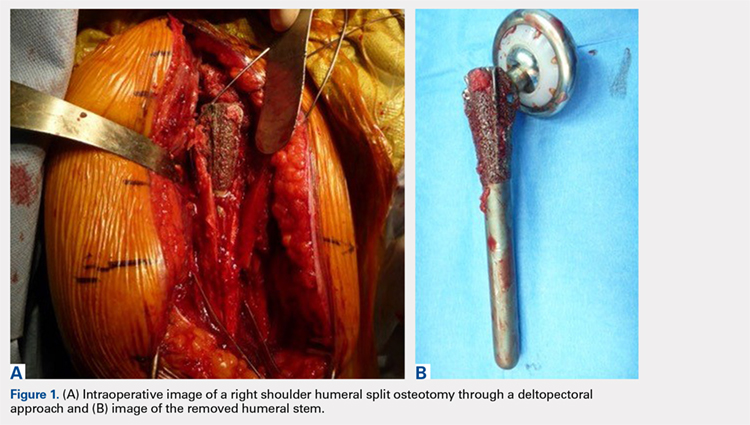

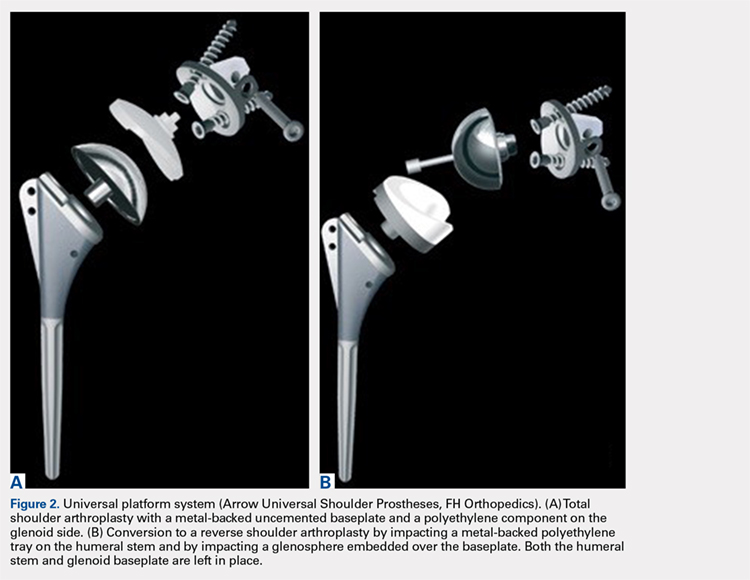

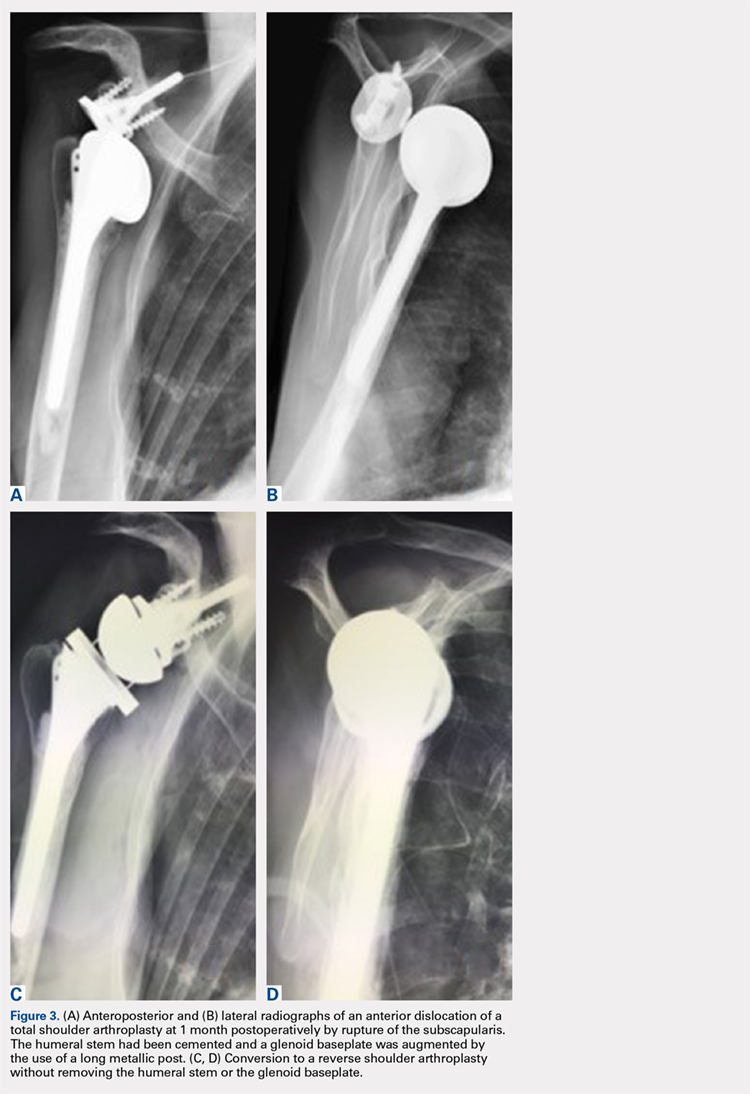

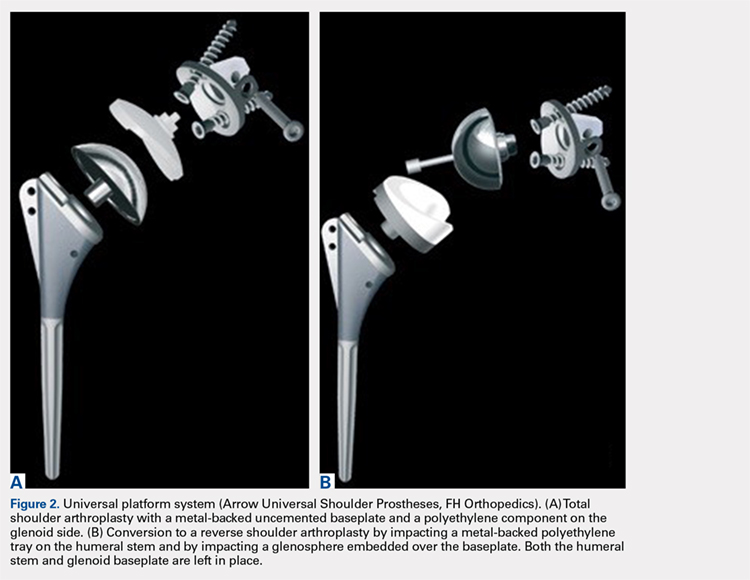

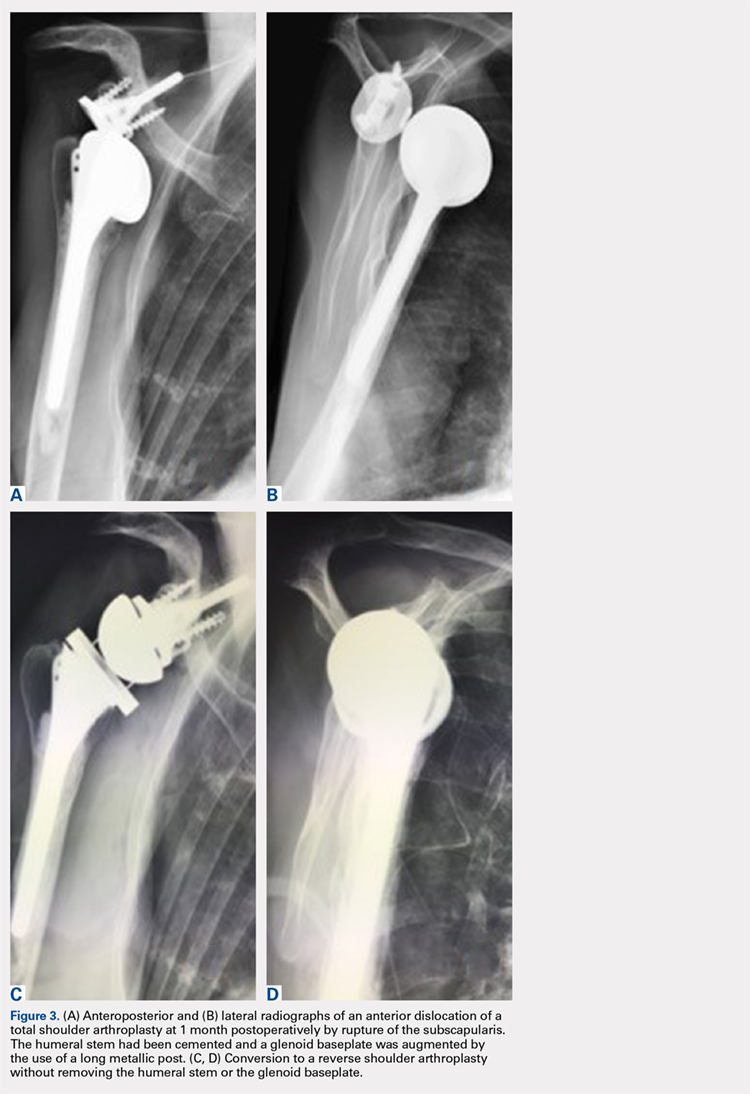

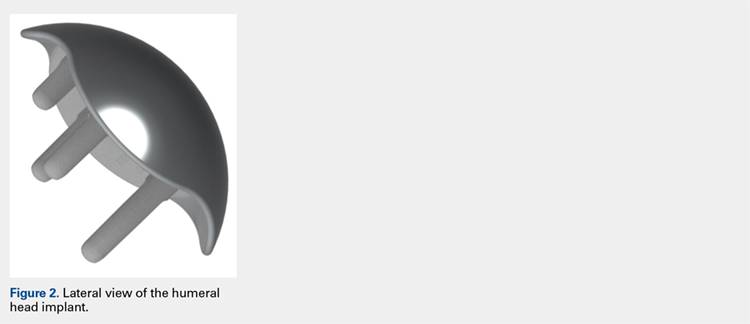

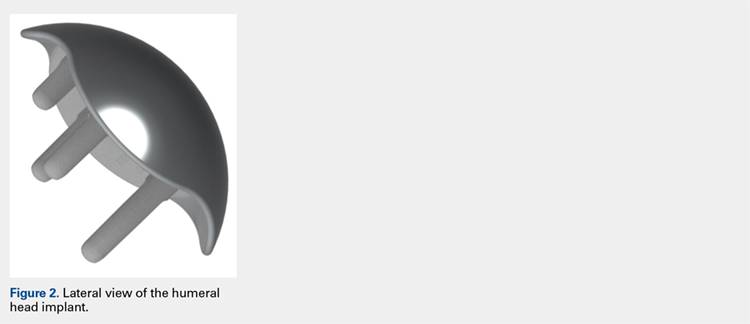

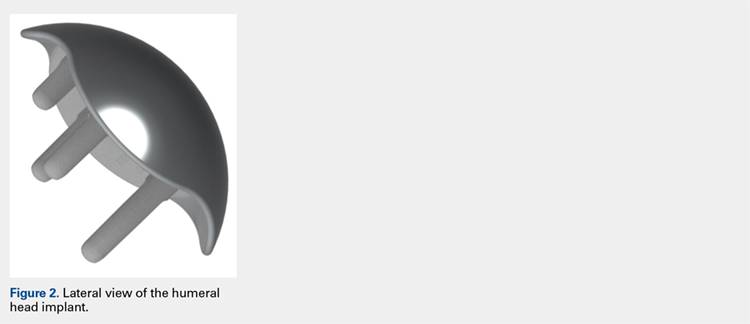

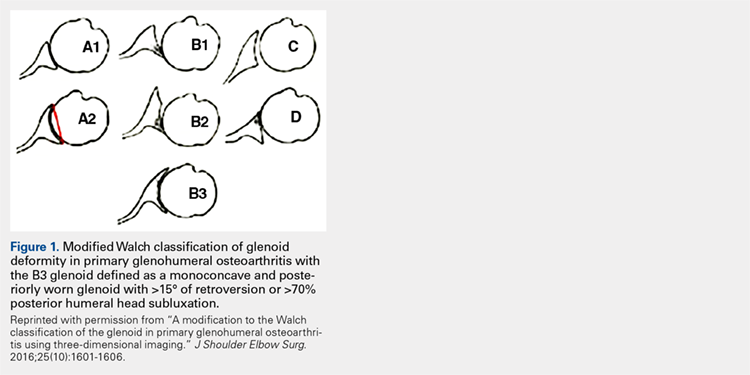

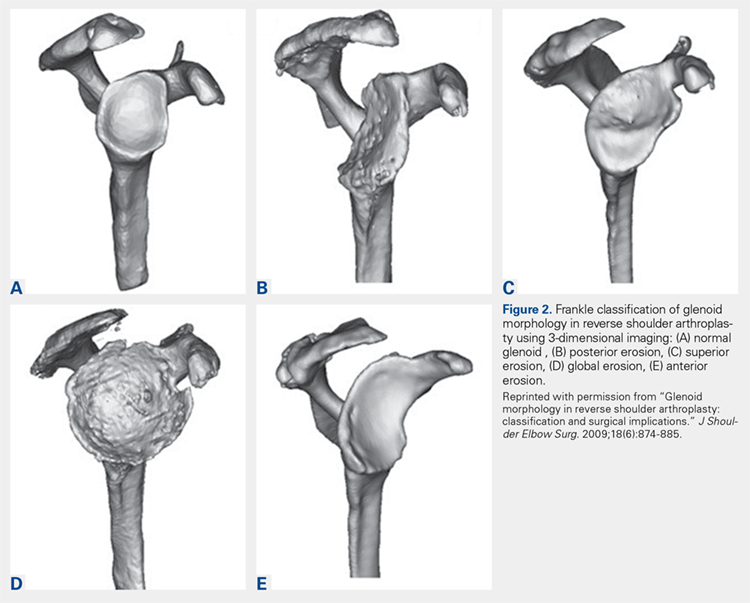

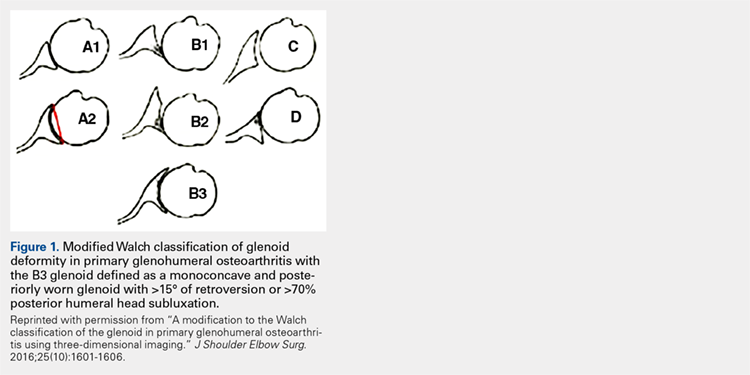

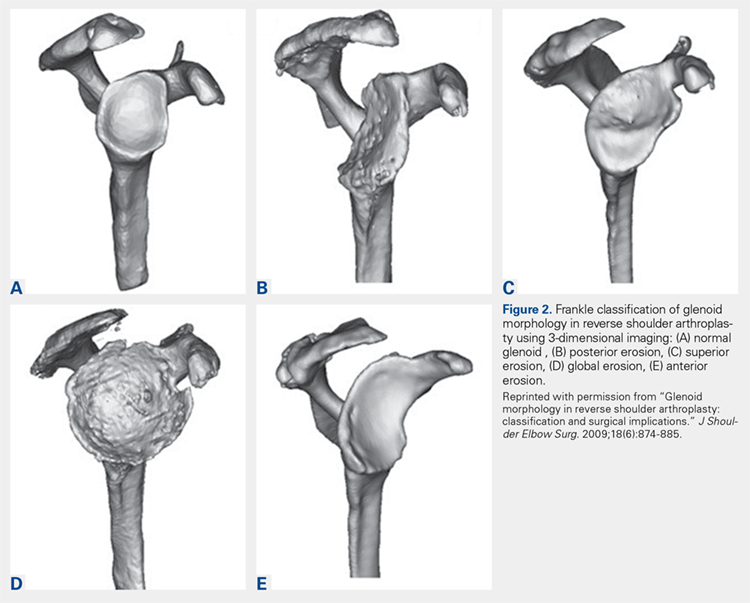

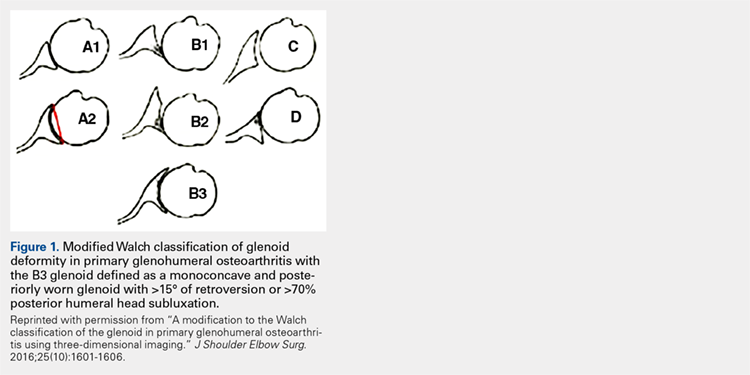

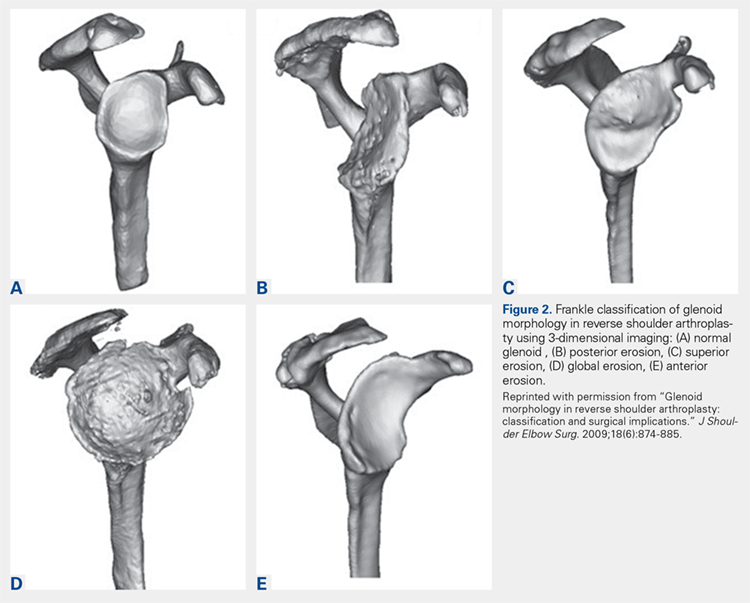

There are a variety of different etiologies of proximal humeral bone loss that result in distinctly different clinical presentations. These can be fairly mild, as is the case of isolated resorption of the greater tuberosity in a non-united proximal humerus fracture (Figure 1). Alternatively, they can be severe, as seen in a grossly loose cemented long-stemmed component that is freely mobile, creating a windshield-wiper effect throughout the length of the humerus (Figure 2). This can be somewhat deceiving, however, as the amount of bone loss, as well as the pathophysiologic process that led to the bone loss, are important factors to determine ideal reconstructive methods. In the case of a failed open reduction internal fixation, where the tuberosity has failed to unite or has been resected, there is much less of a biologic response in comparison with implant loosening associated with osteolysis. This latter condition will be associated with a much more destructive inflammatory response resulting in poor tissue quality and often dramatic thinning of the cortex. If one simply measured the distance from the most proximal remaining bone stock to the area where the greater tuberosity should be, a loose stem with subsidence and ballooning of the cortices may appear to have a similar amount of bone loss as a failed hemiarthroplasty for fracture with a well-fixed stem. However, intraoperatively, one will find that the bone that appeared to be present radiographically in the case of the loose stem is of such poor quality that it cannot reasonably provide any beneficial fixation. In light of this, different treatment modalities are recommended for different types of bone loss, and the revision surgeon must be able to anticipate this and possess a full armamentarium of options to treat these challenging cases successfully.

INDICATIONS

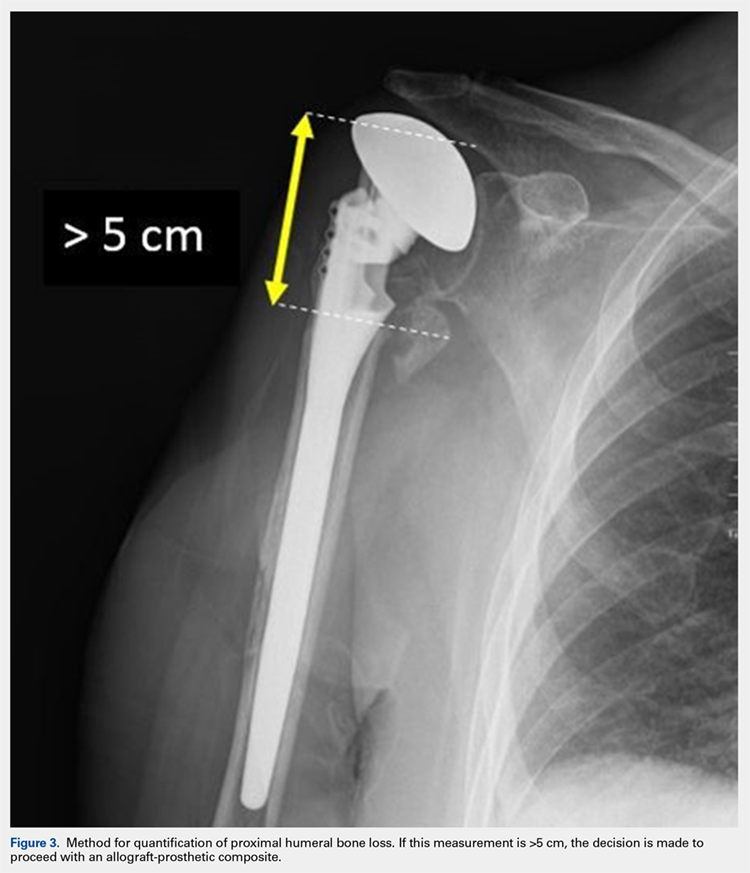

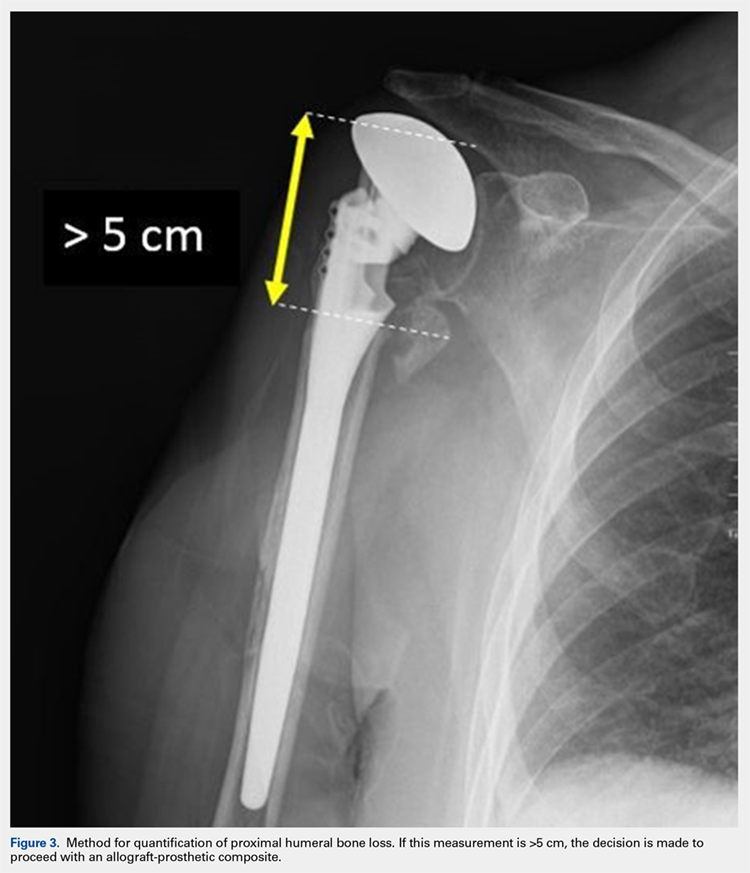

Our technique to manage proximal humeral bone loss is dependent on both the quantity of bone loss, which can be measured radiographically, as well as the anticipated inflammatory response described above. As both the destructive process and the amount of bone loss increase, the importance of more advanced reconstructive procedures that will sustain implant security and soft-tissue management becomes apparent. In the least destructive cases with <5 cm of bone loss, successful revision can typically be accomplished with stem removal and placement of a new monoblock humeral stem. In cases where more advanced destructive pathology is present, and bone loss is >5 cm, an allograft-prosthetic composite (APC) is typically used. In both scenarios, if the stem being revised is cemented and the cement mantle remains intact, and of reasonable length, consideration is given to the cement-within-cement technique. Finally, in the most destructive cases where bone loss exceeds 10 cm and a large biological response is anticipated (eg, periprosthetic fractures with humeral loosening), the use of a longer diaphyseal-incorporating APC is often necessary. This prosthetic composite can be combined with a cement-within-cement technique as well.

It is important to comment on the implications of using modular stems in this setting. With advanced bone loss, a situation is often encountered where the newly implanted stem geometry and working length may be insufficient to acquire adequate rotational stability. In this setting, if a modular junction is positioned close to the stem and cement/bone interface, it will be exposed to very high stress concentrations which can lead to component fracture38 as well as taper corrosion, also referred to as trunnionosis. This latter phenomenon, which has been well studied in the total hip arthroplasty literature with the use of modular components,39 is especially relevant given the high torsional loads imparted at the modular junction. Ultimately, high torsional loads lead to micromotion and electrochemical ion release via degradation of the passivation layer, initiating the process of mechanically assisted crevice corrosion.40 For these reasons, when a modular stem must be used in the presence of mild to moderate bone loss, using a proximal humeral allograft to protect the junction or to provide additional fixation may be implemented with a lower threshold than when using a monoblock stem.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE: ALLOGRAFT-PROSTHETIC COMPOSITES

A standard deltopectoral approach is used, taking care to preserve all viable muscular attachments to the proximal humerus. After removal of the prosthetic humeral head, the decision to proceed with removal of the stem at this juncture is based on several factors. If the remaining proximal humeral bone is so compromised that it might not be able to withstand the forces exerted upon it during retraction for glenoid exposure, the component is left in place. Additionally, if there is consideration that the glenoid-sided bone loss may be so severe that a glenoid baseplate cannot be implanted, and the stem remains well fixed, it is retained so that it can be converted to a hemiarthroplasty.

If neither of the above issues is present, the humeral stem is removed. If a well-fixed press-fit stem is in place, it is typically removed using a combination of burrs and osteotomes to disrupt the bone-implant interface, and the stem is then carefully removed using an impactor and mallet. If a cemented stem is present, the stem is removed in a similar manner, and the cement mantle is left in place if stable, in anticipation of a cement-within-cement technique. If the mantle is disrupted, standard cement removal instruments are used to remove all cement from the canal meticulously.

Continue to: Management of the glenoid...

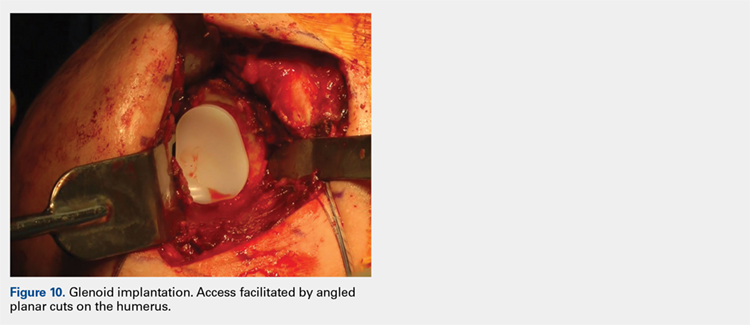

Management of the glenoid can have significant implications with regard to the humerus. Most notably, the size of the glenosphere has direct implications on the fixation of the humeral component. Use of larger diameter glenospheres result in increased contact area between the glenosphere and humerosocket, adding constraint to the articulation and further increasing the stresses at the implant-bone interface. As such, the use of larger glenospheres to prevent instability must be balanced with the resulting implications on humeral component fixation, especially in cases of severe bone loss.

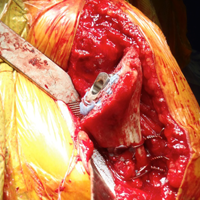

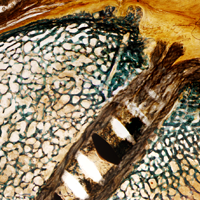

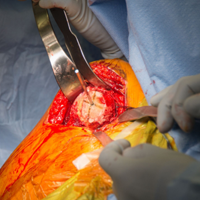

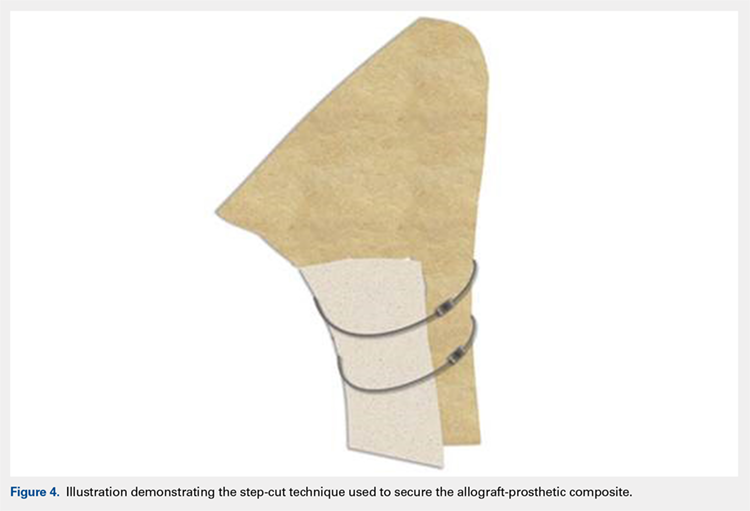

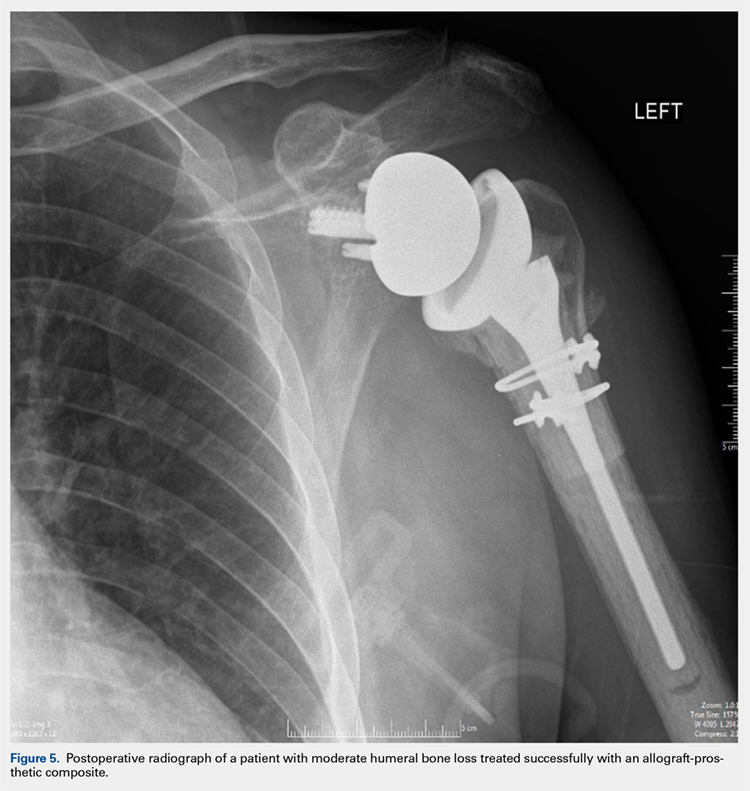

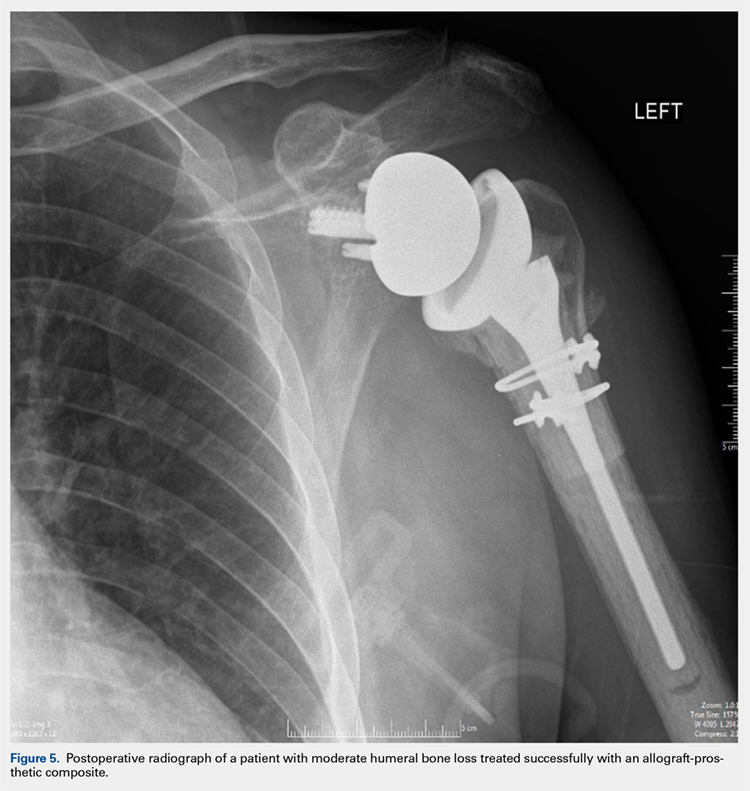

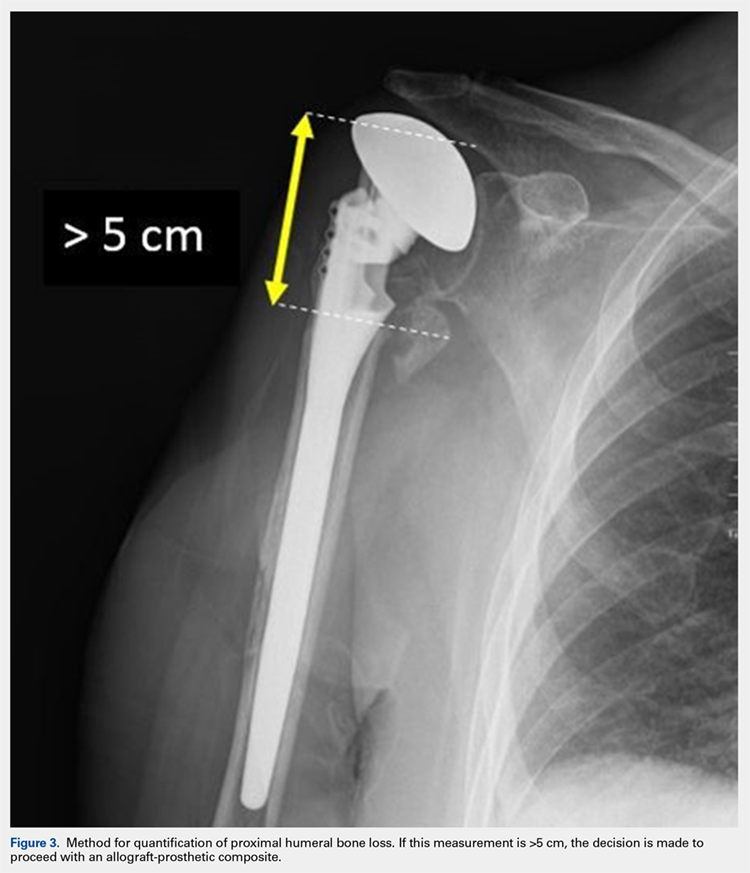

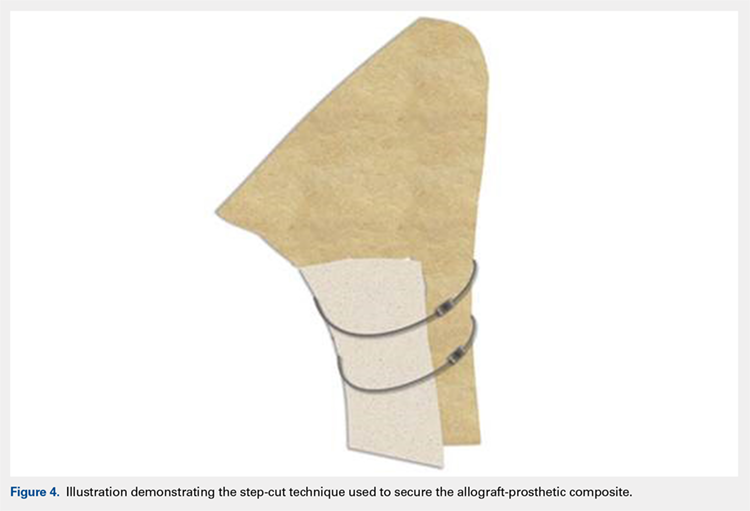

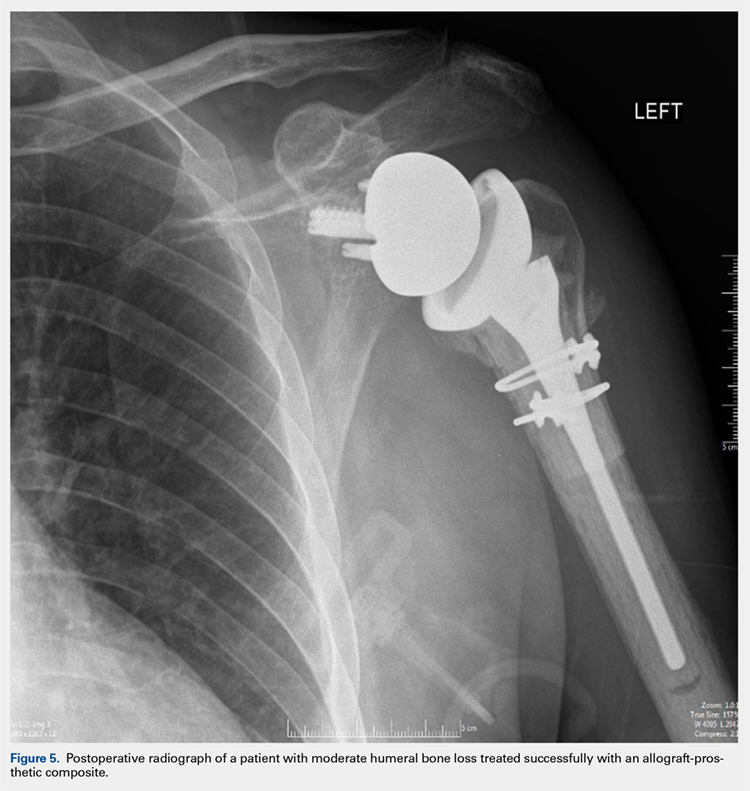

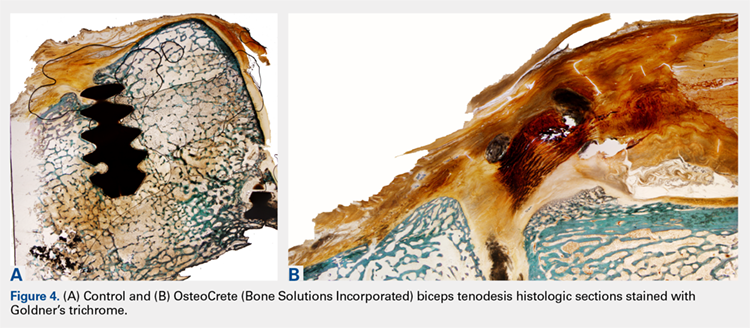

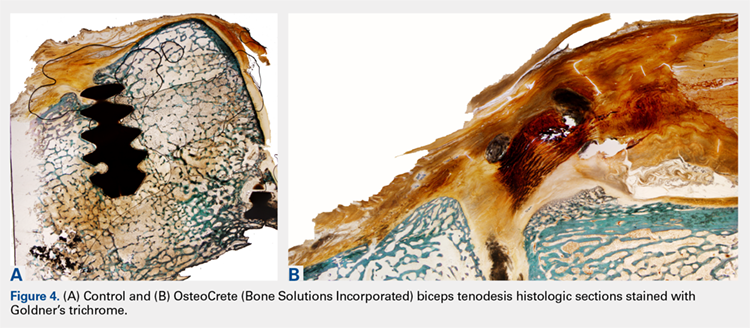

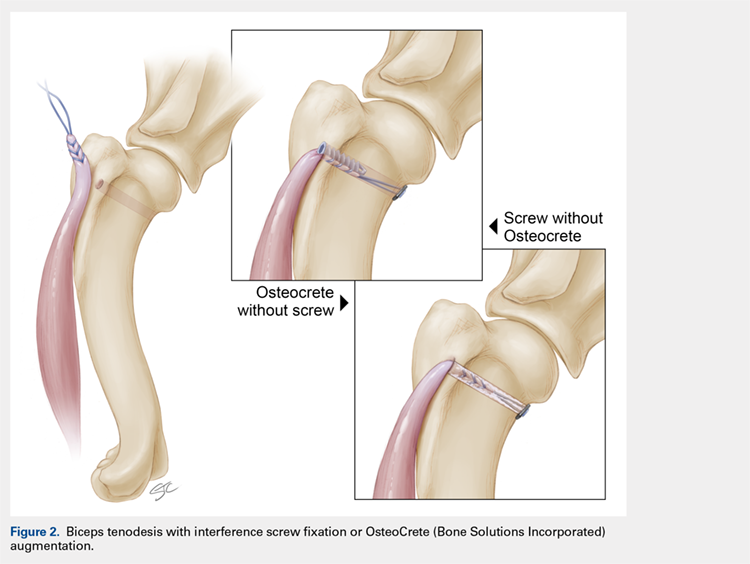

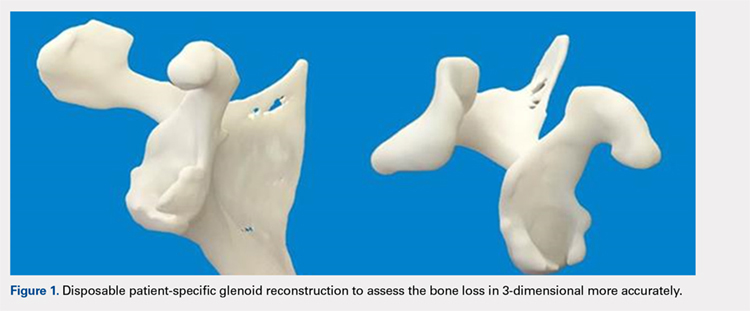

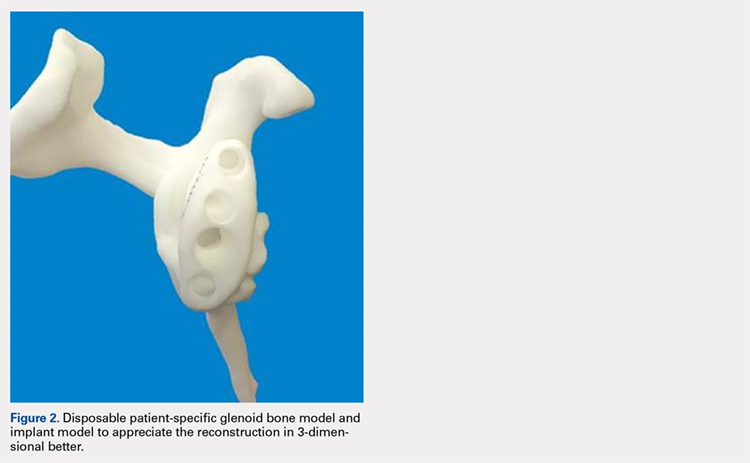

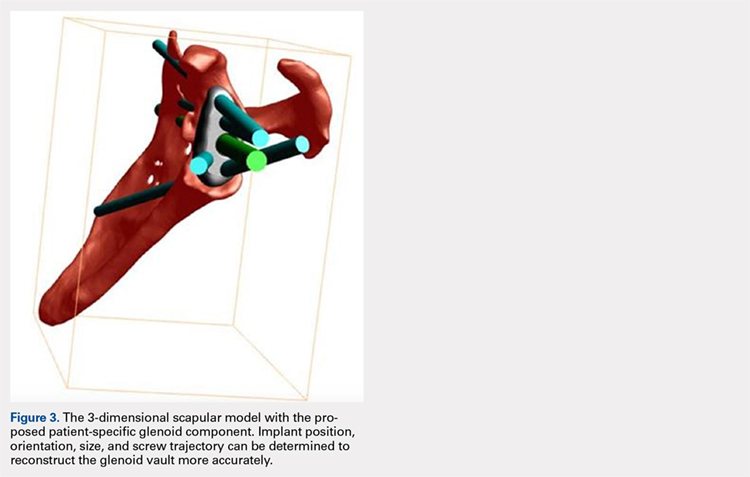

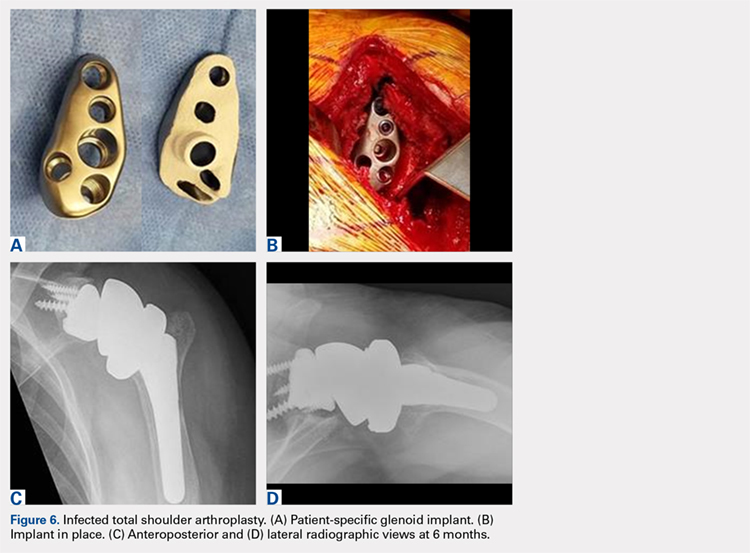

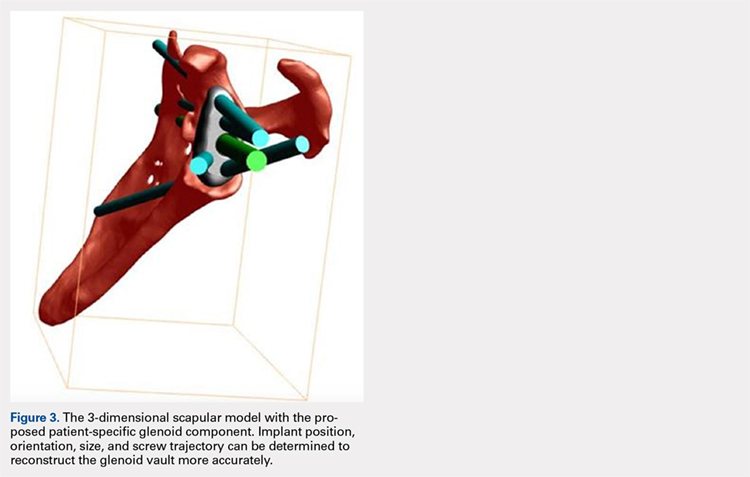

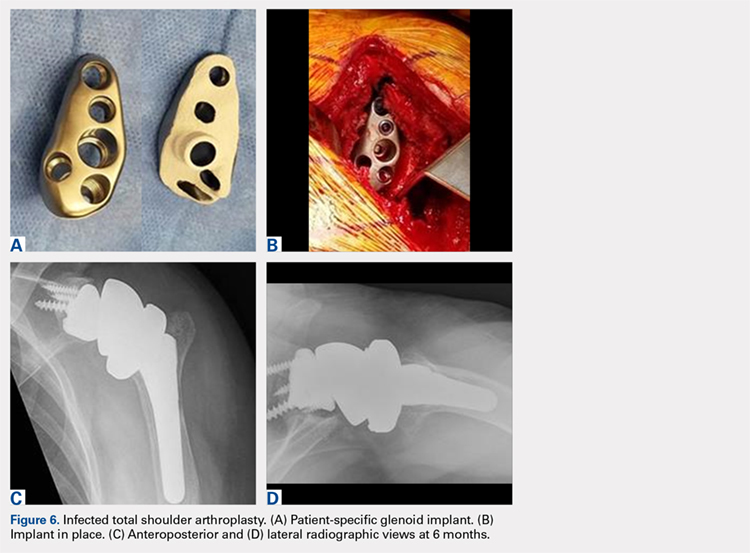

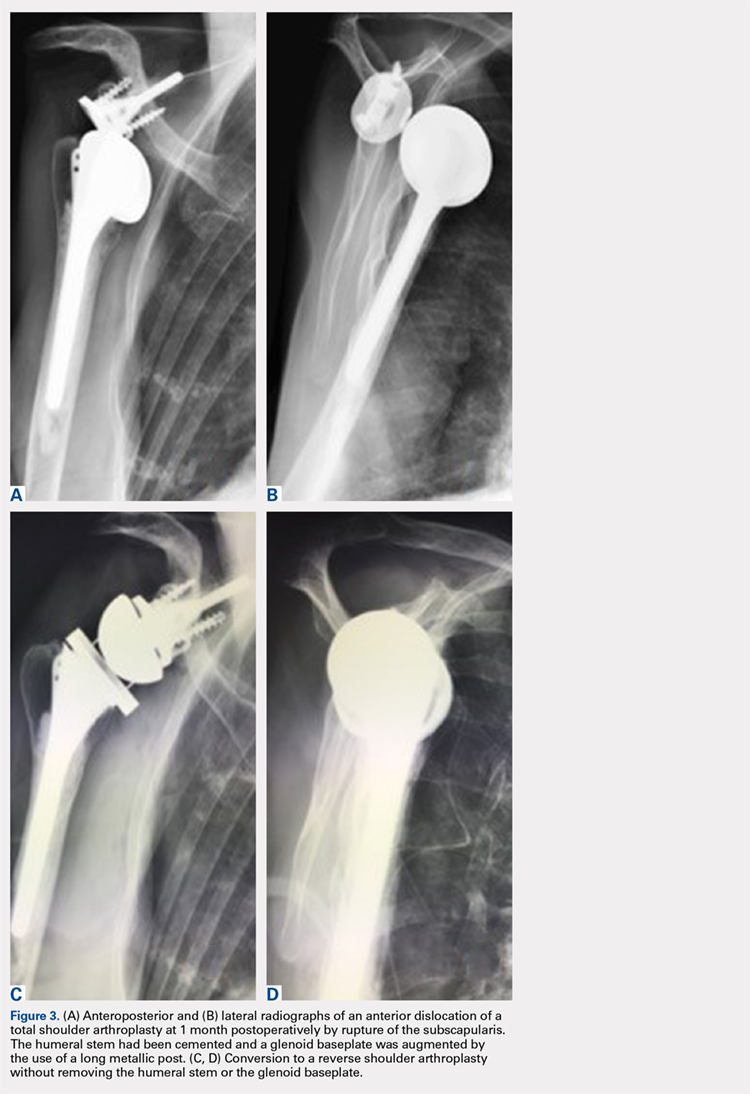

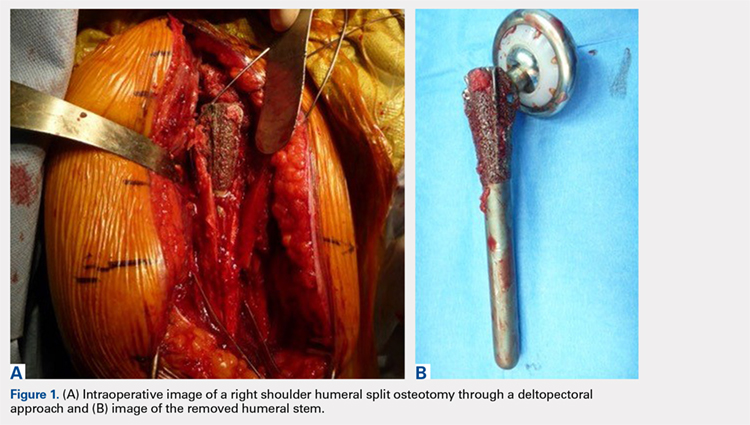

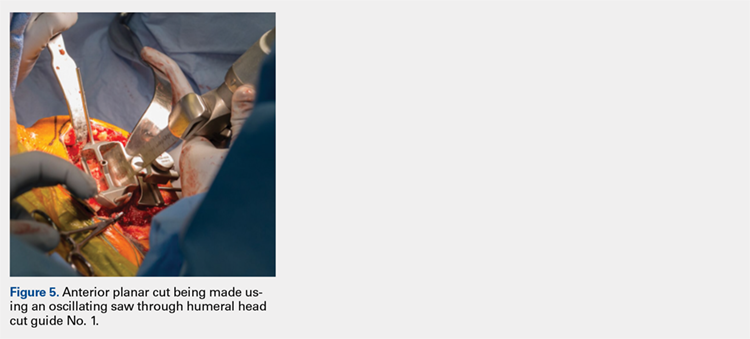

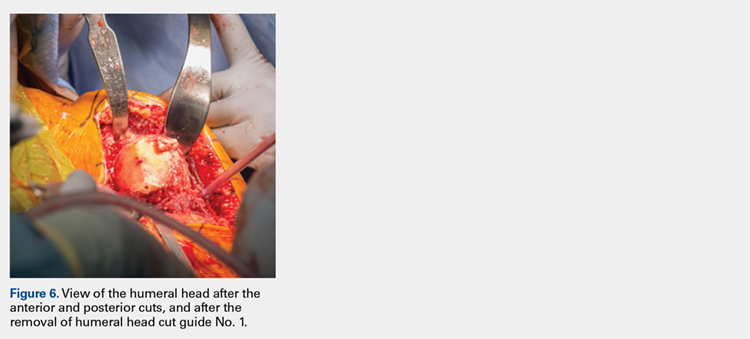

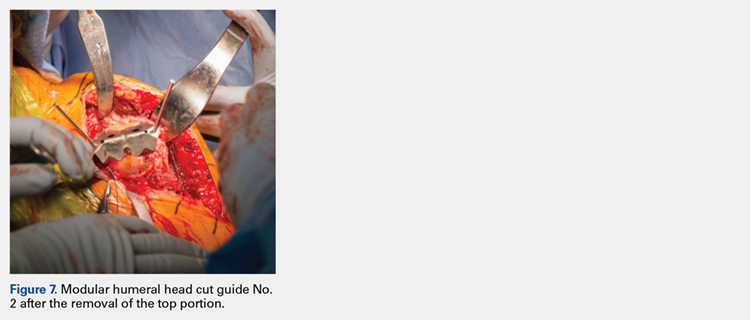

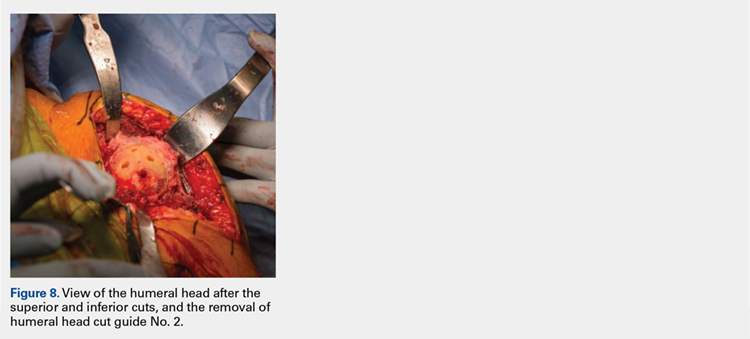

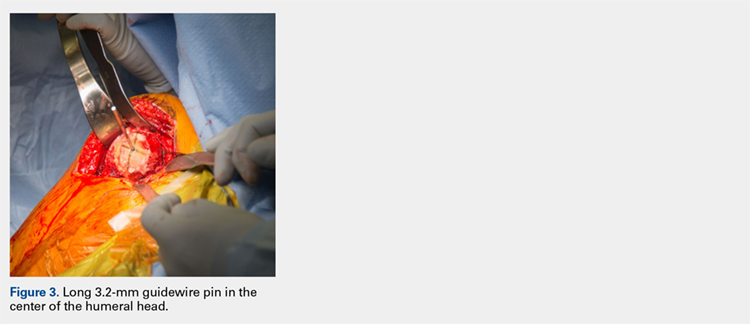

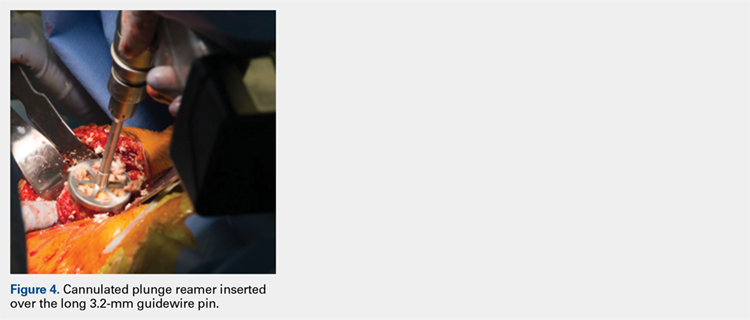

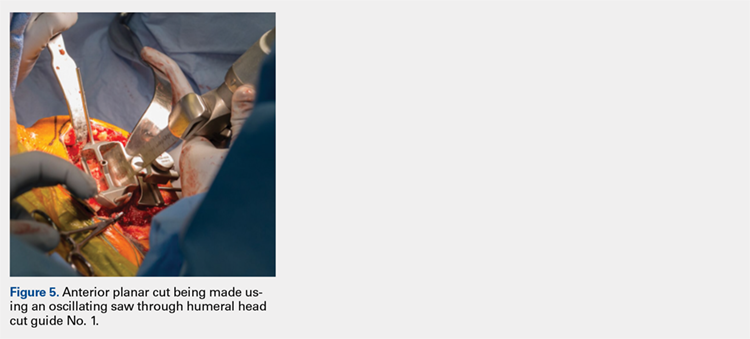

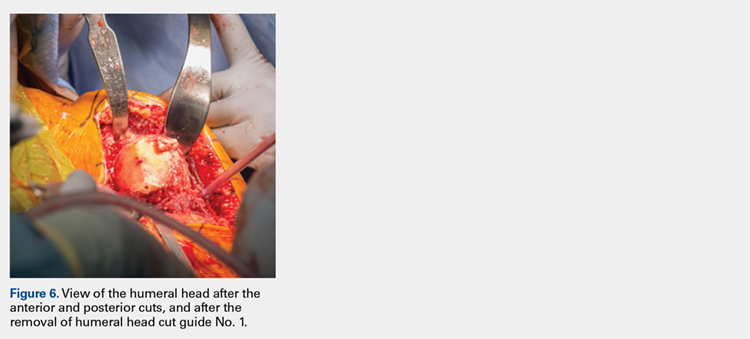

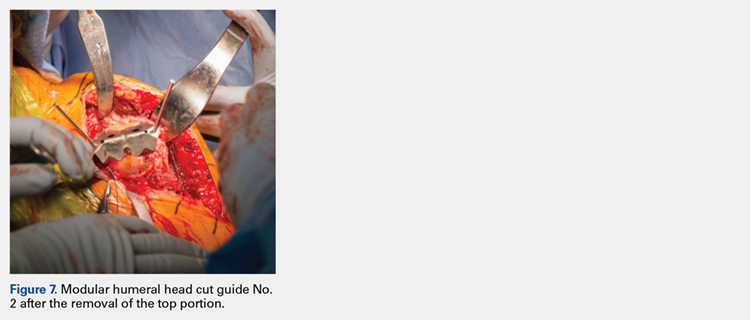

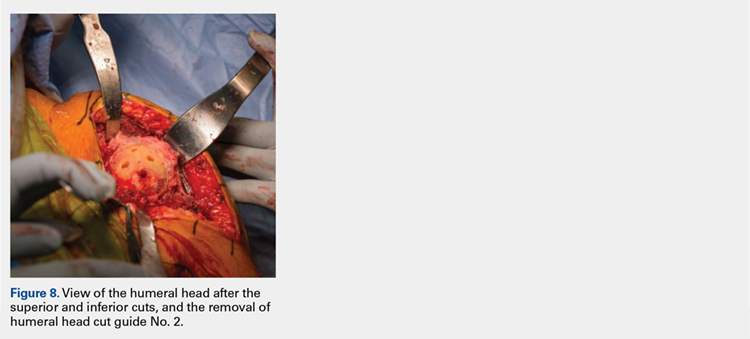

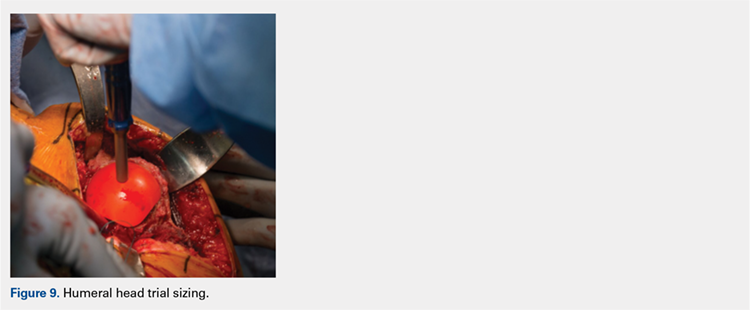

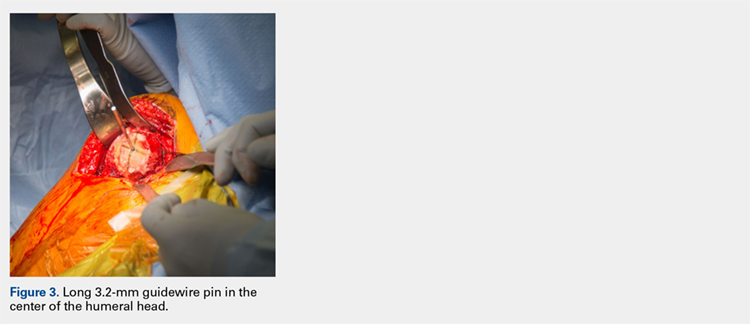

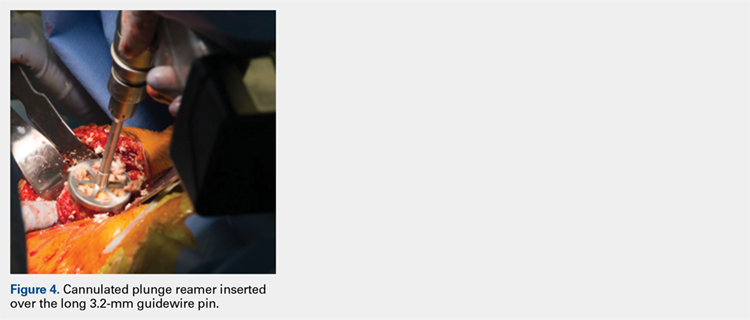

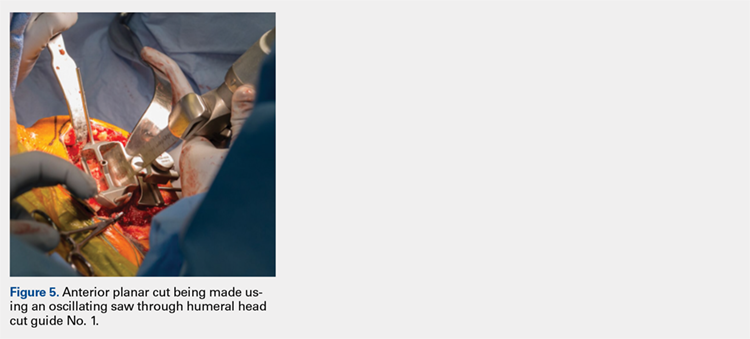

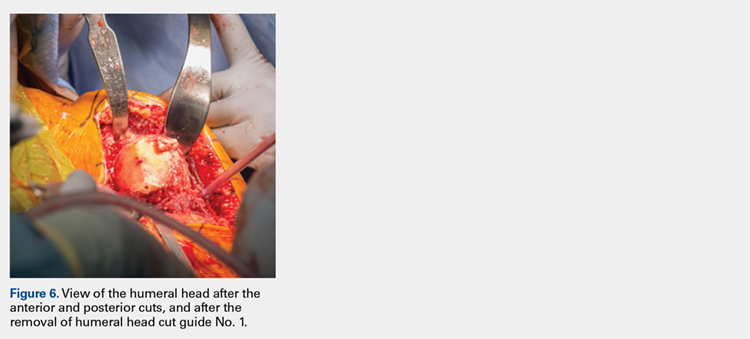

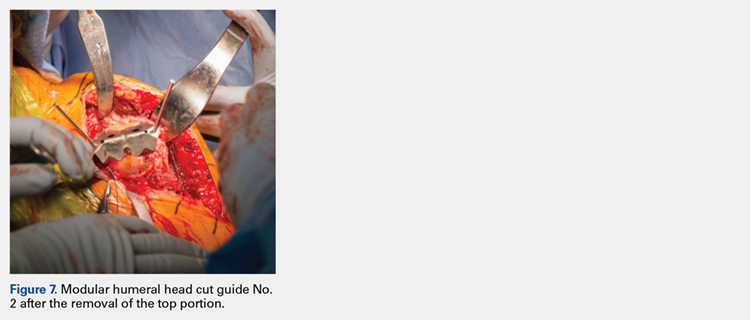

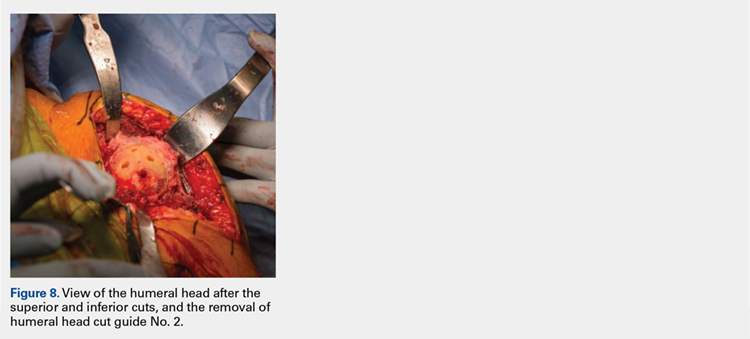

After implanting the appropriate glenosphere, attention is then turned back to the humerus. Trial implants are sequentially used to obtain adequate humeral length and stability. Once this is accomplished, the amount of humeral bone loss is quantified by measuring the distance from the superior aspect of the medial humeral tray to the medial humeral shaft. If this number is >5 cm (Figure 3), the decision is made to proceed with an APC. The allograft humeral head is cut, cancellous bone is removed, and a step-cut is performed, with the medial portion of the allograft measuring the same length as that of bone loss and the lateral plate extending an additional several centimeters distally (Figure 4). Additional soft tissue is removed from the allograft, leaving the subscapularis stump intact for later repair with the patient’s native tissue. The allograft is secured to the patient’s proximal humerus using multiple cerclage wires, and the humeral stem is cemented into place. The final construct is shown in Figure 5.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS: CASES OF ADVANCED BONE LOSS

In cases of advanced humeral bone loss, as is often seen when revising loose humeral stems, larger allografts that span a significant length of the diaphysis are often required. This type of bone loss has implications with regard to how the deltoid insertion is managed. Interestingly, even in situations when the vast majority of the remaining diaphysis consists of ectatic egg-shell bone, the deltoid tuberosity remains of fairly substantial quality due to the continued pull of the muscular insertion on this area. This fragment is isolated, carefully mobilized, and subsequently repaired back on top of the allograft using cables.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Patients are kept in a shoulder immobilizer for 6 weeks after surgery to facilitate allograft incorporation and subscapularis tendon healing. During this time, pendulum exercises are initiated. Active assisted range of motion (ROM) exercises begin after 6 weeks, consisting of supine forward elevation. A sling is given to be used in public. Light strengthening exercises begin at 3 months postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

In cases of mild to moderate proximal humeral bone loss, RSA using a long-stem humeral component without allograft augmentation is a viable option. Budge and colleagues38 demonstrated excellent results in a population of 15 patients with an average of 38 mm of proximal humeral bone loss without use of allografts. Interestingly, they noted 1 case of component fracture in a modular prosthesis and therefore concluded that monoblock humeral stems should be used in the absence of allograft augmentation.

Continue to: In more advanced cases of bone loss...

In more advanced cases of bone loss, our data shows that use of APCs can result in equally satisfactory results. In a series of 25 patients with an average bone loss of 54 mm, patients were able to achieve statistically significant improvements in pain, ROM, and function with high rates of allograft incorporation.9 Overall, a low rate of complications was noted, including 1 infection. This finding is consistent with an additional study looking specifically at factors associated with infection in revision SA, which found that the use of allografts was not associated with increased risk of infection.41

As stated previously, the size of allograft needed for the APC construct is related to the distinct pathology encountered. In our experience, we have noted that well-fixed stems can be treated with short metaphyseal APCs in 85% of cases. On the other hand, loose stems require long allografts measuring >10 cm in 90% of cases. As such, these cases typically require mobilization of the deltoid insertion as described above, and therefore it is important that the surgeon is prepared for this aspect of the procedure preoperatively.

Finally, the cement-within-cement technique, originally popularized for use in revision total hip arthroplasty, has demonstrated reliable results when utilized in revision SA.42 To date, there are no recommendations regarding the minimal length of existing cement mantle that is needed to perform this technique. In situations in which the length of the cement mantle is questionable, our preference is to combine the cement-within-cement technique with an APC when possible.

1. Day JS, Lau E, Ong KL, Williams GR, Ramsey ML, Kurtz SM. Prevalence and projections of total shoulder and elbow arthroplasty in the United States to 2015. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(8):1115-1120. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.02.009.

2. Padegimas EM, Maltenfort M, Lazarus MD, Ramsey ML, Williams GR, Namdari S. Future patient demand for shoulder arthroplasty by younger patients: national projections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):1860-1867. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4231-z.

3. Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(4):514-522. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.006.

4. Levy JC, Virani N, Pupello D, et al. Use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral arthritis and rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(2):189-195. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.

5. Melis B, Bonnevialle N, Neyton L, et al. Glenoid loosening and failure in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty: is revision with a reverse shoulder arthroplasty a reliable option? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):342-349. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.05.021.

6. Deutsch A, Abboud JA, Kelly J, et al. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty for glenoid component loosening. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):706-716. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2007.01.007.

7. Kelly JD, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1516-1525. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.021.

8. Black EM, Roberts SM, Siegel E, Yannopoulos P, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty as salvage for failed prior arthroplasty in patients 65 years of age or younger. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1036-1042. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.019.

9. Composite P, Chacon BA, Virani N, et al. Revision arthroplasty with use of a reverse shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009;1:119-127. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00094.

10. Klein SM, Dunning P, Mulieri P, Pupello D, Downes K, Frankle MA. Effects of acquired glenoid bone defects on surgical technique and clinical outcomes in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1144-1154. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00778.

11. Patel DN, Young B, Onyekwelu I, Zuckerman JD, Kwon YW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for failed shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1478-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.004.

12. Cuff D, Levy JC, Gutiérrez S, Frankle MA. Torsional stability of modular and non-modular reverse shoulder humeral components in a proximal humeral bone loss model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):646-651. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.10.026.

13. Morgan SJ, Furry K, Parekh A, Agudelo JF, Smith WR. The deltoid muscle: an anatomic description of the deltoid insertion to the proximal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(1):19-21. doi:10.1097/01.bot.0000187063.43267.18.

14. Gagey O, Hue E. Mechanics of the deltoid muscle. A new approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:250-257. doi:10.1097/00003086-200006000-00030.

15. De Wilde L, Plasschaert F. Prosthetic treatment and functional recovery of the shoulder after tumor resection 10 years ago: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):645-649. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.11.001.

16. Wataru S, Kazuomi S, Yoshikazu N, Hiroaki I, Takaharu Y, Hideki Y. Three-dimensional morphological analysis of humeral heads: a study in cadavers. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(3):392-396. doi:10.1080/00016470510030878.

17. Tillett E, Smith M, Fulcher M, Shanklin J. Anatomic determination of humeral head retroversion: the relationship of the central axis of the humeral head to the bicipital groove. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2(5):255-256. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80085-2.

18. Doyle AJ, Burks RT. Comparison of humeral head retroversion with the humeral axis/biceps groove relationship: a study in live subjects and cadavers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(5):453-457. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90193-8.

19. Johnson JW, Thostenson JD, Suva LJ, Hasan SA. Relationship of bicipital groove rotation with humeral head retroversion: a three-dimensional computed tomographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):719-724. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.00085.

20. Hromádka R, Kuběna AA, Pokorný D, Popelka S, Jahoda D, Sosna A. Lesser tuberosity is more reliable than bicipital groove when determining orientation of humeral head in primary shoulder arthroplasty. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(1):31-37. doi:10.1007/s00276-009-0543-6.

21. Hertel R, Knothe U, Ballmer FT. Geometry of the proximal humerus and implications for prosthetic design. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(4):331-338. doi:10.1067/mse.2002.124429.

22. Pearl ML. Proximal humeral anatomy in shoulder arthroplasty: Implications for prosthetic design and surgical technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(suppl 1):99-104. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.025.

23. Robertson DD, Yuan J, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL, Yamaguchi K. Three-dimensional analysis of the proximal part of the humerus: relevance to arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(11):1594-1602.

24. Mochizuki T, Sugaya H, Uomizu M, et al. Humeral insertion of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):962-969. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00427.

25. Arai R, Sugaya H, Mochizuki T, Nimura A, Moriishi J, Akita K. Subscapularis tendon tear: an anatomic and clinical investigation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):997-1004. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2008.04.076.

26. Nimura A, Kato A, Yamaguchi K, et al. The superior capsule of the shoulder joint complements the insertion of the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):867-872. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.034.

27. Rispoli DM, Athwal GS, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. The anatomy of the deltoid insertion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(3):386-390. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.10.012.

28. Schwartz DG, Kang SH, Lynch TS, et al. The anterior deltoid’s importance in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a cadaveric biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(3):357-364. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.02.002.

29. Walker M, Brooks J, Willis M, Frankle M. How reverse shoulder arthroplasty works. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2440-2451. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1892-0.

30. Torrens C, Corrales M, Melendo E, Solano A, Rodríguez-Baeza A, Cáceres E. The pectoralis major tendon as a reference for restoring humeral length and retroversion with hemiarthroplasty for fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):947-950. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.05.041.

31. Ponce BA, Thompson KJ, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Re-evaluation of pectoralis major height as an anatomic reference for humeral height in fracture hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1567-1572. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.039.

32. LaFrance R, Madsen W, Yaseen Z, Giordano B, Maloney M, Voloshin I. Relevant anatomic landmarks and measurements for biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1395-1399. doi:10.1177/0363546513482297.

33. Beck PA, Hoffer MM. Latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons: separate or conjoint tendons? J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9(3):308-309.

34. Bhatt CR, Prajapati B, Patil DS, Patel VD, Singh BGP, Mehta CD. Variation in the insertion of the latissimus dorsi & its clinical importance. J Orthop. 2013;10(1):25-28. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2013.01.002.

35. Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88(1):113-120. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00282.

36. Elhassan B, Christensen TJ, Wagner ER. Feasibility of latissimus and teres major transfer to reconstruct irreparable subscapularis tendon tear: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):492-499. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.046.

37. Pouliart N, Gagey O. Significance of the latissimus dorsi for shoulder instability. II. Its influence on dislocation behavior in a sequential cutting protocol of the glenohumeral capsule. Clin Anat. 2005;18(7):500-509. doi:10.1002/ca.20181.

38. Budge MD, Moravek JE, Zimel MN, Nolan EM, Wiater JM. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the management of failed shoulder arthroplasty with proximal humeral bone loss: is allograft augmentation necessary? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(6):739-744. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.008.

39. Weiser MC, Lavernia CJ. Trunnionosis in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(17):27-29. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00345.

40. Cohen J. Current concepts review. Corrosion of metal orthopaedic implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(10):1554.

41. Meijer ST, Paulino Pereira NR, Nota SPFT, Ferrone ML, Schwab JH, Lozano Calderón SA. Factors associated with infection after reconstructive shoulder surgery for proximal humerus tumors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(6):931-938. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.014.

42. Wagner ER, Houdek MT, Hernandez NM, Cofield RH, Sánchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW. Cement-within-cement technique in revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(8):1448-1453. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.013.

ABSTRACT

Revision shoulder arthroplasty is becoming more prevalent as the rate of primary shoulder arthroplasty in the US continues to increase. The management of proximal humeral bone loss in the revision setting presents a difficult problem without a clear solution. Different preoperative diagnoses often lead to distinctly different patterns of bone loss. Successful management of these cases requires a clear understanding of the normal anatomy of the proximal humerus, as well as structural limitations imposed by significant bone loss and the effect this loss has on component fixation. Our preferred technique differs depending on the pattern of bone loss encountered. The use of allograft-prosthetic composites, the cement-within-cement technique, and combinations of these strategies comprise the mainstay of our treatment algorithm. This article focuses on indications, surgical techniques, and some of the published outcomes using these strategies in the management of proximal humeral bone loss.

Continue to: The demand for shoulder arthroplasty...

The demand for shoulder arthroplasty (SA) has increased significantly over the past decade, with a 200% increase witnessed from 2011 to 2015.1 SA performed in patients younger than 55 years is expected to increase 333% between 2011 to 2030.2 With increasing rates of SA being performed in younger patient populations, rates of revision SA also can be expected to climb. Revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) has arisen as a viable option in these patients, and multiple studies demonstrate excellent outcomes that can be obtained with RSA.3-11

Despite significant improvements obtained in revision SA since the mainstream acceptance of RSA, bone loss remains a problematic issue. Loss of humeral bone stock, in particular, can be a challenging problem to solve with multiple clinical implications. Biomechanical studies have demonstrated that if bone loss is left unaddressed, increased bending and torsional forces on the prosthesis result, which ultimately contribute to increased micromotion and eventual component failure.12 In addition, existing challenges are associated with the lack of attachment sites for both multiple muscles and tendons. Also, there is a loss of the normal lateralized pull of the deltoid, which results in a decreased amount of force generated by this muscle.13,14 Ultimately, the increased loss of bone can lead to a devastating situation where there is not enough bone to provide adequate fixation while maintaining the appropriate humeral length necessary to achieve stability of the articulation, which will inevitably lead to instability.4,15 Therefore, techniques are needed to address proximal humeral bone loss while maintaining as much native humeral bone as possible.

PROXIMAL HUMERUS: ANATOMICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The anatomy of the proximal humerus has been studied in great detail and reported in a number of different studies.16-23 The average humeral head thickness (24 mm in men and 19 mm in women) and offset relative to the humeral shaft (2.1 mm posterior and 6.6 mm medial) act to tension the rotator cuff musculature appropriately and contribute to a wrapping effect that allows the deltoid to function more effectively.13,14 Knowledge regarding the rotator cuff footprint has advanced over the past 10 years, specifically with regard to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus.24 The current belief is that the supraspinatus has a triangular insertion onto the most anterior aspect of the greater tuberosity, with a maximum medial-to-lateral length of 6.9 mm and a maximum anterior-to-posterior width of 12.6 mm. The infraspinatus insertion has a trapezoidal insertion, with a maximum medial-to-lateral length of 10.2 mm and anterior-to-posterior width of 32.7 mm. The subscapularis, by far the largest of all the rotator cuff muscles, has a complex geometry with regard to its insertion on the lesser tuberosity, with 4 different insertion points and an overall lateral footprint measuring 37.6 mm and a medial footprint measuring 40.7 mm.25 Finally, the teres minor, with the smallest volume of all the rotator cuff muscles, inserts immediately inferior to the infraspinatus along the inferior facet of the greater tuberosity.26

Aside from the rotator cuff, there are various other muscles and tendons that insert about the proximal humerus and are essential for normal function. The deltoid, which inserts at a point approximately 6 cm from the greater tuberosity along the length of the humerus, with an insertion length between 5 cm to 7 cm,13,27 is the primary mover of the shoulder and essential for proper function after RSA.28,29 The pectoralis major tendon, which begins inserting at a point approximately 5.6 cm from the humeral head and spans a distance of 7.7 cm along the length of the humerus,30-32 is important not only for function but as an anatomical landmark in reconstruction. Lastly, the latissimus dorsi and teres major, which share a role in extension, adduction, and internal rotation of the glenohumeral joint, insert along the floor and medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus, respectively.33,34 In addition to their role in tendon transfer procedures because of treating irreparable posterosuperior cuff and subscapularis tears,35,36 it has been suggested that these tendons may play some role in glenohumeral joint stability.37

In addition to the loss of muscular attachments, the absence of proximal humeral bone stock, in and of itself, can have deleterious effects on fixation of the humeral component. RSA is a semiconstrained device, which results in increased transmission of forces to the interface between the humeral implant and its surrounding structures, including cement (when present) and the bone itself. When there is the absence of significant amounts of bone, the remaining bone must now account for an even higher proportion of these forces. A previous biomechanical study showed that cemented humeral stems demonstrated significantly increased micromotion in the presence of proximal humeral bone loss, particularly when a modular humeral component was used.12

Continue to: TYPES OF BONE LOSS

TYPES OF BONE LOSS

There are a variety of different etiologies of proximal humeral bone loss that result in distinctly different clinical presentations. These can be fairly mild, as is the case of isolated resorption of the greater tuberosity in a non-united proximal humerus fracture (Figure 1). Alternatively, they can be severe, as seen in a grossly loose cemented long-stemmed component that is freely mobile, creating a windshield-wiper effect throughout the length of the humerus (Figure 2). This can be somewhat deceiving, however, as the amount of bone loss, as well as the pathophysiologic process that led to the bone loss, are important factors to determine ideal reconstructive methods. In the case of a failed open reduction internal fixation, where the tuberosity has failed to unite or has been resected, there is much less of a biologic response in comparison with implant loosening associated with osteolysis. This latter condition will be associated with a much more destructive inflammatory response resulting in poor tissue quality and often dramatic thinning of the cortex. If one simply measured the distance from the most proximal remaining bone stock to the area where the greater tuberosity should be, a loose stem with subsidence and ballooning of the cortices may appear to have a similar amount of bone loss as a failed hemiarthroplasty for fracture with a well-fixed stem. However, intraoperatively, one will find that the bone that appeared to be present radiographically in the case of the loose stem is of such poor quality that it cannot reasonably provide any beneficial fixation. In light of this, different treatment modalities are recommended for different types of bone loss, and the revision surgeon must be able to anticipate this and possess a full armamentarium of options to treat these challenging cases successfully.

INDICATIONS

Our technique to manage proximal humeral bone loss is dependent on both the quantity of bone loss, which can be measured radiographically, as well as the anticipated inflammatory response described above. As both the destructive process and the amount of bone loss increase, the importance of more advanced reconstructive procedures that will sustain implant security and soft-tissue management becomes apparent. In the least destructive cases with <5 cm of bone loss, successful revision can typically be accomplished with stem removal and placement of a new monoblock humeral stem. In cases where more advanced destructive pathology is present, and bone loss is >5 cm, an allograft-prosthetic composite (APC) is typically used. In both scenarios, if the stem being revised is cemented and the cement mantle remains intact, and of reasonable length, consideration is given to the cement-within-cement technique. Finally, in the most destructive cases where bone loss exceeds 10 cm and a large biological response is anticipated (eg, periprosthetic fractures with humeral loosening), the use of a longer diaphyseal-incorporating APC is often necessary. This prosthetic composite can be combined with a cement-within-cement technique as well.

It is important to comment on the implications of using modular stems in this setting. With advanced bone loss, a situation is often encountered where the newly implanted stem geometry and working length may be insufficient to acquire adequate rotational stability. In this setting, if a modular junction is positioned close to the stem and cement/bone interface, it will be exposed to very high stress concentrations which can lead to component fracture38 as well as taper corrosion, also referred to as trunnionosis. This latter phenomenon, which has been well studied in the total hip arthroplasty literature with the use of modular components,39 is especially relevant given the high torsional loads imparted at the modular junction. Ultimately, high torsional loads lead to micromotion and electrochemical ion release via degradation of the passivation layer, initiating the process of mechanically assisted crevice corrosion.40 For these reasons, when a modular stem must be used in the presence of mild to moderate bone loss, using a proximal humeral allograft to protect the junction or to provide additional fixation may be implemented with a lower threshold than when using a monoblock stem.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE: ALLOGRAFT-PROSTHETIC COMPOSITES

A standard deltopectoral approach is used, taking care to preserve all viable muscular attachments to the proximal humerus. After removal of the prosthetic humeral head, the decision to proceed with removal of the stem at this juncture is based on several factors. If the remaining proximal humeral bone is so compromised that it might not be able to withstand the forces exerted upon it during retraction for glenoid exposure, the component is left in place. Additionally, if there is consideration that the glenoid-sided bone loss may be so severe that a glenoid baseplate cannot be implanted, and the stem remains well fixed, it is retained so that it can be converted to a hemiarthroplasty.

If neither of the above issues is present, the humeral stem is removed. If a well-fixed press-fit stem is in place, it is typically removed using a combination of burrs and osteotomes to disrupt the bone-implant interface, and the stem is then carefully removed using an impactor and mallet. If a cemented stem is present, the stem is removed in a similar manner, and the cement mantle is left in place if stable, in anticipation of a cement-within-cement technique. If the mantle is disrupted, standard cement removal instruments are used to remove all cement from the canal meticulously.

Continue to: Management of the glenoid...

Management of the glenoid can have significant implications with regard to the humerus. Most notably, the size of the glenosphere has direct implications on the fixation of the humeral component. Use of larger diameter glenospheres result in increased contact area between the glenosphere and humerosocket, adding constraint to the articulation and further increasing the stresses at the implant-bone interface. As such, the use of larger glenospheres to prevent instability must be balanced with the resulting implications on humeral component fixation, especially in cases of severe bone loss.

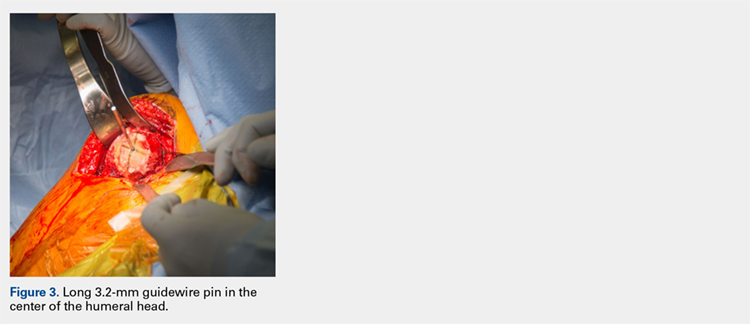

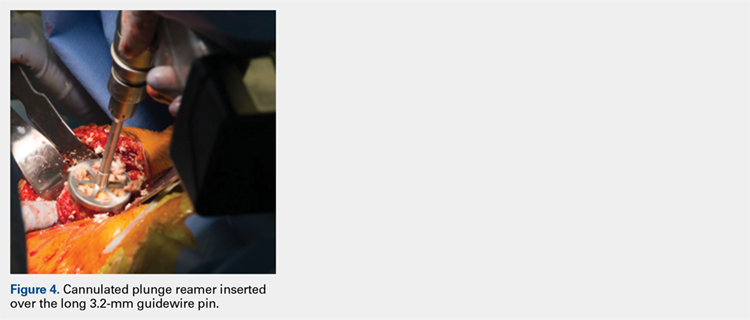

After implanting the appropriate glenosphere, attention is then turned back to the humerus. Trial implants are sequentially used to obtain adequate humeral length and stability. Once this is accomplished, the amount of humeral bone loss is quantified by measuring the distance from the superior aspect of the medial humeral tray to the medial humeral shaft. If this number is >5 cm (Figure 3), the decision is made to proceed with an APC. The allograft humeral head is cut, cancellous bone is removed, and a step-cut is performed, with the medial portion of the allograft measuring the same length as that of bone loss and the lateral plate extending an additional several centimeters distally (Figure 4). Additional soft tissue is removed from the allograft, leaving the subscapularis stump intact for later repair with the patient’s native tissue. The allograft is secured to the patient’s proximal humerus using multiple cerclage wires, and the humeral stem is cemented into place. The final construct is shown in Figure 5.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS: CASES OF ADVANCED BONE LOSS

In cases of advanced humeral bone loss, as is often seen when revising loose humeral stems, larger allografts that span a significant length of the diaphysis are often required. This type of bone loss has implications with regard to how the deltoid insertion is managed. Interestingly, even in situations when the vast majority of the remaining diaphysis consists of ectatic egg-shell bone, the deltoid tuberosity remains of fairly substantial quality due to the continued pull of the muscular insertion on this area. This fragment is isolated, carefully mobilized, and subsequently repaired back on top of the allograft using cables.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Patients are kept in a shoulder immobilizer for 6 weeks after surgery to facilitate allograft incorporation and subscapularis tendon healing. During this time, pendulum exercises are initiated. Active assisted range of motion (ROM) exercises begin after 6 weeks, consisting of supine forward elevation. A sling is given to be used in public. Light strengthening exercises begin at 3 months postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

In cases of mild to moderate proximal humeral bone loss, RSA using a long-stem humeral component without allograft augmentation is a viable option. Budge and colleagues38 demonstrated excellent results in a population of 15 patients with an average of 38 mm of proximal humeral bone loss without use of allografts. Interestingly, they noted 1 case of component fracture in a modular prosthesis and therefore concluded that monoblock humeral stems should be used in the absence of allograft augmentation.

Continue to: In more advanced cases of bone loss...

In more advanced cases of bone loss, our data shows that use of APCs can result in equally satisfactory results. In a series of 25 patients with an average bone loss of 54 mm, patients were able to achieve statistically significant improvements in pain, ROM, and function with high rates of allograft incorporation.9 Overall, a low rate of complications was noted, including 1 infection. This finding is consistent with an additional study looking specifically at factors associated with infection in revision SA, which found that the use of allografts was not associated with increased risk of infection.41

As stated previously, the size of allograft needed for the APC construct is related to the distinct pathology encountered. In our experience, we have noted that well-fixed stems can be treated with short metaphyseal APCs in 85% of cases. On the other hand, loose stems require long allografts measuring >10 cm in 90% of cases. As such, these cases typically require mobilization of the deltoid insertion as described above, and therefore it is important that the surgeon is prepared for this aspect of the procedure preoperatively.

Finally, the cement-within-cement technique, originally popularized for use in revision total hip arthroplasty, has demonstrated reliable results when utilized in revision SA.42 To date, there are no recommendations regarding the minimal length of existing cement mantle that is needed to perform this technique. In situations in which the length of the cement mantle is questionable, our preference is to combine the cement-within-cement technique with an APC when possible.

ABSTRACT

Revision shoulder arthroplasty is becoming more prevalent as the rate of primary shoulder arthroplasty in the US continues to increase. The management of proximal humeral bone loss in the revision setting presents a difficult problem without a clear solution. Different preoperative diagnoses often lead to distinctly different patterns of bone loss. Successful management of these cases requires a clear understanding of the normal anatomy of the proximal humerus, as well as structural limitations imposed by significant bone loss and the effect this loss has on component fixation. Our preferred technique differs depending on the pattern of bone loss encountered. The use of allograft-prosthetic composites, the cement-within-cement technique, and combinations of these strategies comprise the mainstay of our treatment algorithm. This article focuses on indications, surgical techniques, and some of the published outcomes using these strategies in the management of proximal humeral bone loss.

Continue to: The demand for shoulder arthroplasty...

The demand for shoulder arthroplasty (SA) has increased significantly over the past decade, with a 200% increase witnessed from 2011 to 2015.1 SA performed in patients younger than 55 years is expected to increase 333% between 2011 to 2030.2 With increasing rates of SA being performed in younger patient populations, rates of revision SA also can be expected to climb. Revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) has arisen as a viable option in these patients, and multiple studies demonstrate excellent outcomes that can be obtained with RSA.3-11

Despite significant improvements obtained in revision SA since the mainstream acceptance of RSA, bone loss remains a problematic issue. Loss of humeral bone stock, in particular, can be a challenging problem to solve with multiple clinical implications. Biomechanical studies have demonstrated that if bone loss is left unaddressed, increased bending and torsional forces on the prosthesis result, which ultimately contribute to increased micromotion and eventual component failure.12 In addition, existing challenges are associated with the lack of attachment sites for both multiple muscles and tendons. Also, there is a loss of the normal lateralized pull of the deltoid, which results in a decreased amount of force generated by this muscle.13,14 Ultimately, the increased loss of bone can lead to a devastating situation where there is not enough bone to provide adequate fixation while maintaining the appropriate humeral length necessary to achieve stability of the articulation, which will inevitably lead to instability.4,15 Therefore, techniques are needed to address proximal humeral bone loss while maintaining as much native humeral bone as possible.

PROXIMAL HUMERUS: ANATOMICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The anatomy of the proximal humerus has been studied in great detail and reported in a number of different studies.16-23 The average humeral head thickness (24 mm in men and 19 mm in women) and offset relative to the humeral shaft (2.1 mm posterior and 6.6 mm medial) act to tension the rotator cuff musculature appropriately and contribute to a wrapping effect that allows the deltoid to function more effectively.13,14 Knowledge regarding the rotator cuff footprint has advanced over the past 10 years, specifically with regard to the supraspinatus and infraspinatus.24 The current belief is that the supraspinatus has a triangular insertion onto the most anterior aspect of the greater tuberosity, with a maximum medial-to-lateral length of 6.9 mm and a maximum anterior-to-posterior width of 12.6 mm. The infraspinatus insertion has a trapezoidal insertion, with a maximum medial-to-lateral length of 10.2 mm and anterior-to-posterior width of 32.7 mm. The subscapularis, by far the largest of all the rotator cuff muscles, has a complex geometry with regard to its insertion on the lesser tuberosity, with 4 different insertion points and an overall lateral footprint measuring 37.6 mm and a medial footprint measuring 40.7 mm.25 Finally, the teres minor, with the smallest volume of all the rotator cuff muscles, inserts immediately inferior to the infraspinatus along the inferior facet of the greater tuberosity.26

Aside from the rotator cuff, there are various other muscles and tendons that insert about the proximal humerus and are essential for normal function. The deltoid, which inserts at a point approximately 6 cm from the greater tuberosity along the length of the humerus, with an insertion length between 5 cm to 7 cm,13,27 is the primary mover of the shoulder and essential for proper function after RSA.28,29 The pectoralis major tendon, which begins inserting at a point approximately 5.6 cm from the humeral head and spans a distance of 7.7 cm along the length of the humerus,30-32 is important not only for function but as an anatomical landmark in reconstruction. Lastly, the latissimus dorsi and teres major, which share a role in extension, adduction, and internal rotation of the glenohumeral joint, insert along the floor and medial lip of the intertubercular groove of the humerus, respectively.33,34 In addition to their role in tendon transfer procedures because of treating irreparable posterosuperior cuff and subscapularis tears,35,36 it has been suggested that these tendons may play some role in glenohumeral joint stability.37

In addition to the loss of muscular attachments, the absence of proximal humeral bone stock, in and of itself, can have deleterious effects on fixation of the humeral component. RSA is a semiconstrained device, which results in increased transmission of forces to the interface between the humeral implant and its surrounding structures, including cement (when present) and the bone itself. When there is the absence of significant amounts of bone, the remaining bone must now account for an even higher proportion of these forces. A previous biomechanical study showed that cemented humeral stems demonstrated significantly increased micromotion in the presence of proximal humeral bone loss, particularly when a modular humeral component was used.12

Continue to: TYPES OF BONE LOSS

TYPES OF BONE LOSS

There are a variety of different etiologies of proximal humeral bone loss that result in distinctly different clinical presentations. These can be fairly mild, as is the case of isolated resorption of the greater tuberosity in a non-united proximal humerus fracture (Figure 1). Alternatively, they can be severe, as seen in a grossly loose cemented long-stemmed component that is freely mobile, creating a windshield-wiper effect throughout the length of the humerus (Figure 2). This can be somewhat deceiving, however, as the amount of bone loss, as well as the pathophysiologic process that led to the bone loss, are important factors to determine ideal reconstructive methods. In the case of a failed open reduction internal fixation, where the tuberosity has failed to unite or has been resected, there is much less of a biologic response in comparison with implant loosening associated with osteolysis. This latter condition will be associated with a much more destructive inflammatory response resulting in poor tissue quality and often dramatic thinning of the cortex. If one simply measured the distance from the most proximal remaining bone stock to the area where the greater tuberosity should be, a loose stem with subsidence and ballooning of the cortices may appear to have a similar amount of bone loss as a failed hemiarthroplasty for fracture with a well-fixed stem. However, intraoperatively, one will find that the bone that appeared to be present radiographically in the case of the loose stem is of such poor quality that it cannot reasonably provide any beneficial fixation. In light of this, different treatment modalities are recommended for different types of bone loss, and the revision surgeon must be able to anticipate this and possess a full armamentarium of options to treat these challenging cases successfully.

INDICATIONS

Our technique to manage proximal humeral bone loss is dependent on both the quantity of bone loss, which can be measured radiographically, as well as the anticipated inflammatory response described above. As both the destructive process and the amount of bone loss increase, the importance of more advanced reconstructive procedures that will sustain implant security and soft-tissue management becomes apparent. In the least destructive cases with <5 cm of bone loss, successful revision can typically be accomplished with stem removal and placement of a new monoblock humeral stem. In cases where more advanced destructive pathology is present, and bone loss is >5 cm, an allograft-prosthetic composite (APC) is typically used. In both scenarios, if the stem being revised is cemented and the cement mantle remains intact, and of reasonable length, consideration is given to the cement-within-cement technique. Finally, in the most destructive cases where bone loss exceeds 10 cm and a large biological response is anticipated (eg, periprosthetic fractures with humeral loosening), the use of a longer diaphyseal-incorporating APC is often necessary. This prosthetic composite can be combined with a cement-within-cement technique as well.

It is important to comment on the implications of using modular stems in this setting. With advanced bone loss, a situation is often encountered where the newly implanted stem geometry and working length may be insufficient to acquire adequate rotational stability. In this setting, if a modular junction is positioned close to the stem and cement/bone interface, it will be exposed to very high stress concentrations which can lead to component fracture38 as well as taper corrosion, also referred to as trunnionosis. This latter phenomenon, which has been well studied in the total hip arthroplasty literature with the use of modular components,39 is especially relevant given the high torsional loads imparted at the modular junction. Ultimately, high torsional loads lead to micromotion and electrochemical ion release via degradation of the passivation layer, initiating the process of mechanically assisted crevice corrosion.40 For these reasons, when a modular stem must be used in the presence of mild to moderate bone loss, using a proximal humeral allograft to protect the junction or to provide additional fixation may be implemented with a lower threshold than when using a monoblock stem.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE: ALLOGRAFT-PROSTHETIC COMPOSITES

A standard deltopectoral approach is used, taking care to preserve all viable muscular attachments to the proximal humerus. After removal of the prosthetic humeral head, the decision to proceed with removal of the stem at this juncture is based on several factors. If the remaining proximal humeral bone is so compromised that it might not be able to withstand the forces exerted upon it during retraction for glenoid exposure, the component is left in place. Additionally, if there is consideration that the glenoid-sided bone loss may be so severe that a glenoid baseplate cannot be implanted, and the stem remains well fixed, it is retained so that it can be converted to a hemiarthroplasty.

If neither of the above issues is present, the humeral stem is removed. If a well-fixed press-fit stem is in place, it is typically removed using a combination of burrs and osteotomes to disrupt the bone-implant interface, and the stem is then carefully removed using an impactor and mallet. If a cemented stem is present, the stem is removed in a similar manner, and the cement mantle is left in place if stable, in anticipation of a cement-within-cement technique. If the mantle is disrupted, standard cement removal instruments are used to remove all cement from the canal meticulously.

Continue to: Management of the glenoid...

Management of the glenoid can have significant implications with regard to the humerus. Most notably, the size of the glenosphere has direct implications on the fixation of the humeral component. Use of larger diameter glenospheres result in increased contact area between the glenosphere and humerosocket, adding constraint to the articulation and further increasing the stresses at the implant-bone interface. As such, the use of larger glenospheres to prevent instability must be balanced with the resulting implications on humeral component fixation, especially in cases of severe bone loss.

After implanting the appropriate glenosphere, attention is then turned back to the humerus. Trial implants are sequentially used to obtain adequate humeral length and stability. Once this is accomplished, the amount of humeral bone loss is quantified by measuring the distance from the superior aspect of the medial humeral tray to the medial humeral shaft. If this number is >5 cm (Figure 3), the decision is made to proceed with an APC. The allograft humeral head is cut, cancellous bone is removed, and a step-cut is performed, with the medial portion of the allograft measuring the same length as that of bone loss and the lateral plate extending an additional several centimeters distally (Figure 4). Additional soft tissue is removed from the allograft, leaving the subscapularis stump intact for later repair with the patient’s native tissue. The allograft is secured to the patient’s proximal humerus using multiple cerclage wires, and the humeral stem is cemented into place. The final construct is shown in Figure 5.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS: CASES OF ADVANCED BONE LOSS

In cases of advanced humeral bone loss, as is often seen when revising loose humeral stems, larger allografts that span a significant length of the diaphysis are often required. This type of bone loss has implications with regard to how the deltoid insertion is managed. Interestingly, even in situations when the vast majority of the remaining diaphysis consists of ectatic egg-shell bone, the deltoid tuberosity remains of fairly substantial quality due to the continued pull of the muscular insertion on this area. This fragment is isolated, carefully mobilized, and subsequently repaired back on top of the allograft using cables.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Patients are kept in a shoulder immobilizer for 6 weeks after surgery to facilitate allograft incorporation and subscapularis tendon healing. During this time, pendulum exercises are initiated. Active assisted range of motion (ROM) exercises begin after 6 weeks, consisting of supine forward elevation. A sling is given to be used in public. Light strengthening exercises begin at 3 months postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

In cases of mild to moderate proximal humeral bone loss, RSA using a long-stem humeral component without allograft augmentation is a viable option. Budge and colleagues38 demonstrated excellent results in a population of 15 patients with an average of 38 mm of proximal humeral bone loss without use of allografts. Interestingly, they noted 1 case of component fracture in a modular prosthesis and therefore concluded that monoblock humeral stems should be used in the absence of allograft augmentation.

Continue to: In more advanced cases of bone loss...

In more advanced cases of bone loss, our data shows that use of APCs can result in equally satisfactory results. In a series of 25 patients with an average bone loss of 54 mm, patients were able to achieve statistically significant improvements in pain, ROM, and function with high rates of allograft incorporation.9 Overall, a low rate of complications was noted, including 1 infection. This finding is consistent with an additional study looking specifically at factors associated with infection in revision SA, which found that the use of allografts was not associated with increased risk of infection.41

As stated previously, the size of allograft needed for the APC construct is related to the distinct pathology encountered. In our experience, we have noted that well-fixed stems can be treated with short metaphyseal APCs in 85% of cases. On the other hand, loose stems require long allografts measuring >10 cm in 90% of cases. As such, these cases typically require mobilization of the deltoid insertion as described above, and therefore it is important that the surgeon is prepared for this aspect of the procedure preoperatively.

Finally, the cement-within-cement technique, originally popularized for use in revision total hip arthroplasty, has demonstrated reliable results when utilized in revision SA.42 To date, there are no recommendations regarding the minimal length of existing cement mantle that is needed to perform this technique. In situations in which the length of the cement mantle is questionable, our preference is to combine the cement-within-cement technique with an APC when possible.

1. Day JS, Lau E, Ong KL, Williams GR, Ramsey ML, Kurtz SM. Prevalence and projections of total shoulder and elbow arthroplasty in the United States to 2015. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(8):1115-1120. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.02.009.

2. Padegimas EM, Maltenfort M, Lazarus MD, Ramsey ML, Williams GR, Namdari S. Future patient demand for shoulder arthroplasty by younger patients: national projections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):1860-1867. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4231-z.

3. Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(4):514-522. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.006.

4. Levy JC, Virani N, Pupello D, et al. Use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral arthritis and rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(2):189-195. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.

5. Melis B, Bonnevialle N, Neyton L, et al. Glenoid loosening and failure in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty: is revision with a reverse shoulder arthroplasty a reliable option? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):342-349. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.05.021.

6. Deutsch A, Abboud JA, Kelly J, et al. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty for glenoid component loosening. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):706-716. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2007.01.007.

7. Kelly JD, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1516-1525. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.021.

8. Black EM, Roberts SM, Siegel E, Yannopoulos P, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty as salvage for failed prior arthroplasty in patients 65 years of age or younger. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1036-1042. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.019.

9. Composite P, Chacon BA, Virani N, et al. Revision arthroplasty with use of a reverse shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009;1:119-127. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00094.

10. Klein SM, Dunning P, Mulieri P, Pupello D, Downes K, Frankle MA. Effects of acquired glenoid bone defects on surgical technique and clinical outcomes in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1144-1154. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00778.

11. Patel DN, Young B, Onyekwelu I, Zuckerman JD, Kwon YW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for failed shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1478-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.004.

12. Cuff D, Levy JC, Gutiérrez S, Frankle MA. Torsional stability of modular and non-modular reverse shoulder humeral components in a proximal humeral bone loss model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):646-651. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.10.026.

13. Morgan SJ, Furry K, Parekh A, Agudelo JF, Smith WR. The deltoid muscle: an anatomic description of the deltoid insertion to the proximal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(1):19-21. doi:10.1097/01.bot.0000187063.43267.18.

14. Gagey O, Hue E. Mechanics of the deltoid muscle. A new approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:250-257. doi:10.1097/00003086-200006000-00030.

15. De Wilde L, Plasschaert F. Prosthetic treatment and functional recovery of the shoulder after tumor resection 10 years ago: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):645-649. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.11.001.

16. Wataru S, Kazuomi S, Yoshikazu N, Hiroaki I, Takaharu Y, Hideki Y. Three-dimensional morphological analysis of humeral heads: a study in cadavers. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(3):392-396. doi:10.1080/00016470510030878.

17. Tillett E, Smith M, Fulcher M, Shanklin J. Anatomic determination of humeral head retroversion: the relationship of the central axis of the humeral head to the bicipital groove. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2(5):255-256. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80085-2.

18. Doyle AJ, Burks RT. Comparison of humeral head retroversion with the humeral axis/biceps groove relationship: a study in live subjects and cadavers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(5):453-457. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90193-8.

19. Johnson JW, Thostenson JD, Suva LJ, Hasan SA. Relationship of bicipital groove rotation with humeral head retroversion: a three-dimensional computed tomographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):719-724. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.00085.

20. Hromádka R, Kuběna AA, Pokorný D, Popelka S, Jahoda D, Sosna A. Lesser tuberosity is more reliable than bicipital groove when determining orientation of humeral head in primary shoulder arthroplasty. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(1):31-37. doi:10.1007/s00276-009-0543-6.

21. Hertel R, Knothe U, Ballmer FT. Geometry of the proximal humerus and implications for prosthetic design. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(4):331-338. doi:10.1067/mse.2002.124429.

22. Pearl ML. Proximal humeral anatomy in shoulder arthroplasty: Implications for prosthetic design and surgical technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(suppl 1):99-104. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.025.

23. Robertson DD, Yuan J, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL, Yamaguchi K. Three-dimensional analysis of the proximal part of the humerus: relevance to arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(11):1594-1602.

24. Mochizuki T, Sugaya H, Uomizu M, et al. Humeral insertion of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):962-969. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00427.

25. Arai R, Sugaya H, Mochizuki T, Nimura A, Moriishi J, Akita K. Subscapularis tendon tear: an anatomic and clinical investigation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):997-1004. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2008.04.076.

26. Nimura A, Kato A, Yamaguchi K, et al. The superior capsule of the shoulder joint complements the insertion of the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):867-872. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.034.

27. Rispoli DM, Athwal GS, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. The anatomy of the deltoid insertion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(3):386-390. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.10.012.

28. Schwartz DG, Kang SH, Lynch TS, et al. The anterior deltoid’s importance in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a cadaveric biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(3):357-364. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.02.002.

29. Walker M, Brooks J, Willis M, Frankle M. How reverse shoulder arthroplasty works. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2440-2451. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1892-0.

30. Torrens C, Corrales M, Melendo E, Solano A, Rodríguez-Baeza A, Cáceres E. The pectoralis major tendon as a reference for restoring humeral length and retroversion with hemiarthroplasty for fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):947-950. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.05.041.

31. Ponce BA, Thompson KJ, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Re-evaluation of pectoralis major height as an anatomic reference for humeral height in fracture hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1567-1572. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.039.

32. LaFrance R, Madsen W, Yaseen Z, Giordano B, Maloney M, Voloshin I. Relevant anatomic landmarks and measurements for biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1395-1399. doi:10.1177/0363546513482297.

33. Beck PA, Hoffer MM. Latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons: separate or conjoint tendons? J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9(3):308-309.

34. Bhatt CR, Prajapati B, Patil DS, Patel VD, Singh BGP, Mehta CD. Variation in the insertion of the latissimus dorsi & its clinical importance. J Orthop. 2013;10(1):25-28. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2013.01.002.

35. Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88(1):113-120. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00282.

36. Elhassan B, Christensen TJ, Wagner ER. Feasibility of latissimus and teres major transfer to reconstruct irreparable subscapularis tendon tear: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):492-499. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.046.

37. Pouliart N, Gagey O. Significance of the latissimus dorsi for shoulder instability. II. Its influence on dislocation behavior in a sequential cutting protocol of the glenohumeral capsule. Clin Anat. 2005;18(7):500-509. doi:10.1002/ca.20181.

38. Budge MD, Moravek JE, Zimel MN, Nolan EM, Wiater JM. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the management of failed shoulder arthroplasty with proximal humeral bone loss: is allograft augmentation necessary? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(6):739-744. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.008.

39. Weiser MC, Lavernia CJ. Trunnionosis in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(17):27-29. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00345.

40. Cohen J. Current concepts review. Corrosion of metal orthopaedic implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(10):1554.

41. Meijer ST, Paulino Pereira NR, Nota SPFT, Ferrone ML, Schwab JH, Lozano Calderón SA. Factors associated with infection after reconstructive shoulder surgery for proximal humerus tumors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(6):931-938. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.014.

42. Wagner ER, Houdek MT, Hernandez NM, Cofield RH, Sánchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW. Cement-within-cement technique in revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(8):1448-1453. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.013.

1. Day JS, Lau E, Ong KL, Williams GR, Ramsey ML, Kurtz SM. Prevalence and projections of total shoulder and elbow arthroplasty in the United States to 2015. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(8):1115-1120. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.02.009.

2. Padegimas EM, Maltenfort M, Lazarus MD, Ramsey ML, Williams GR, Namdari S. Future patient demand for shoulder arthroplasty by younger patients: national projections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):1860-1867. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4231-z.

3. Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(4):514-522. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.006.

4. Levy JC, Virani N, Pupello D, et al. Use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty in patients with glenohumeral arthritis and rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(2):189-195. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B2.

5. Melis B, Bonnevialle N, Neyton L, et al. Glenoid loosening and failure in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty: is revision with a reverse shoulder arthroplasty a reliable option? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):342-349. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.05.021.

6. Deutsch A, Abboud JA, Kelly J, et al. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty for glenoid component loosening. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):706-716. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2007.01.007.

7. Kelly JD, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1516-1525. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.021.

8. Black EM, Roberts SM, Siegel E, Yannopoulos P, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty as salvage for failed prior arthroplasty in patients 65 years of age or younger. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1036-1042. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.019.

9. Composite P, Chacon BA, Virani N, et al. Revision arthroplasty with use of a reverse shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009;1:119-127. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00094.

10. Klein SM, Dunning P, Mulieri P, Pupello D, Downes K, Frankle MA. Effects of acquired glenoid bone defects on surgical technique and clinical outcomes in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1144-1154. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00778.

11. Patel DN, Young B, Onyekwelu I, Zuckerman JD, Kwon YW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for failed shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1478-1483. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.11.004.

12. Cuff D, Levy JC, Gutiérrez S, Frankle MA. Torsional stability of modular and non-modular reverse shoulder humeral components in a proximal humeral bone loss model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):646-651. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.10.026.

13. Morgan SJ, Furry K, Parekh A, Agudelo JF, Smith WR. The deltoid muscle: an anatomic description of the deltoid insertion to the proximal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(1):19-21. doi:10.1097/01.bot.0000187063.43267.18.

14. Gagey O, Hue E. Mechanics of the deltoid muscle. A new approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;375:250-257. doi:10.1097/00003086-200006000-00030.

15. De Wilde L, Plasschaert F. Prosthetic treatment and functional recovery of the shoulder after tumor resection 10 years ago: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(6):645-649. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.11.001.

16. Wataru S, Kazuomi S, Yoshikazu N, Hiroaki I, Takaharu Y, Hideki Y. Three-dimensional morphological analysis of humeral heads: a study in cadavers. Acta Orthop. 2005;76(3):392-396. doi:10.1080/00016470510030878.

17. Tillett E, Smith M, Fulcher M, Shanklin J. Anatomic determination of humeral head retroversion: the relationship of the central axis of the humeral head to the bicipital groove. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1993;2(5):255-256. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80085-2.

18. Doyle AJ, Burks RT. Comparison of humeral head retroversion with the humeral axis/biceps groove relationship: a study in live subjects and cadavers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(5):453-457. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(98)90193-8.

19. Johnson JW, Thostenson JD, Suva LJ, Hasan SA. Relationship of bicipital groove rotation with humeral head retroversion: a three-dimensional computed tomographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):719-724. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.00085.

20. Hromádka R, Kuběna AA, Pokorný D, Popelka S, Jahoda D, Sosna A. Lesser tuberosity is more reliable than bicipital groove when determining orientation of humeral head in primary shoulder arthroplasty. Surg Radiol Anat. 2010;32(1):31-37. doi:10.1007/s00276-009-0543-6.

21. Hertel R, Knothe U, Ballmer FT. Geometry of the proximal humerus and implications for prosthetic design. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(4):331-338. doi:10.1067/mse.2002.124429.

22. Pearl ML. Proximal humeral anatomy in shoulder arthroplasty: Implications for prosthetic design and surgical technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(suppl 1):99-104. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.025.

23. Robertson DD, Yuan J, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL, Yamaguchi K. Three-dimensional analysis of the proximal part of the humerus: relevance to arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(11):1594-1602.

24. Mochizuki T, Sugaya H, Uomizu M, et al. Humeral insertion of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(5):962-969. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00427.

25. Arai R, Sugaya H, Mochizuki T, Nimura A, Moriishi J, Akita K. Subscapularis tendon tear: an anatomic and clinical investigation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(9):997-1004. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2008.04.076.

26. Nimura A, Kato A, Yamaguchi K, et al. The superior capsule of the shoulder joint complements the insertion of the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):867-872. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2011.04.034.

27. Rispoli DM, Athwal GS, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. The anatomy of the deltoid insertion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(3):386-390. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.10.012.

28. Schwartz DG, Kang SH, Lynch TS, et al. The anterior deltoid’s importance in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a cadaveric biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(3):357-364. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.02.002.

29. Walker M, Brooks J, Willis M, Frankle M. How reverse shoulder arthroplasty works. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2440-2451. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1892-0.

30. Torrens C, Corrales M, Melendo E, Solano A, Rodríguez-Baeza A, Cáceres E. The pectoralis major tendon as a reference for restoring humeral length and retroversion with hemiarthroplasty for fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):947-950. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.05.041.

31. Ponce BA, Thompson KJ, Rosenzweig SD, et al. Re-evaluation of pectoralis major height as an anatomic reference for humeral height in fracture hemiarthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1567-1572. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.039.

32. LaFrance R, Madsen W, Yaseen Z, Giordano B, Maloney M, Voloshin I. Relevant anatomic landmarks and measurements for biceps tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(6):1395-1399. doi:10.1177/0363546513482297.

33. Beck PA, Hoffer MM. Latissimus dorsi and teres major tendons: separate or conjoint tendons? J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9(3):308-309.

34. Bhatt CR, Prajapati B, Patil DS, Patel VD, Singh BGP, Mehta CD. Variation in the insertion of the latissimus dorsi & its clinical importance. J Orthop. 2013;10(1):25-28. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2013.01.002.

35. Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88(1):113-120. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00282.

36. Elhassan B, Christensen TJ, Wagner ER. Feasibility of latissimus and teres major transfer to reconstruct irreparable subscapularis tendon tear: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(4):492-499. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.07.046.

37. Pouliart N, Gagey O. Significance of the latissimus dorsi for shoulder instability. II. Its influence on dislocation behavior in a sequential cutting protocol of the glenohumeral capsule. Clin Anat. 2005;18(7):500-509. doi:10.1002/ca.20181.

38. Budge MD, Moravek JE, Zimel MN, Nolan EM, Wiater JM. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for the management of failed shoulder arthroplasty with proximal humeral bone loss: is allograft augmentation necessary? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(6):739-744. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2012.08.008.

39. Weiser MC, Lavernia CJ. Trunnionosis in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(17):27-29. doi:10.2106/JBJS.17.00345.

40. Cohen J. Current concepts review. Corrosion of metal orthopaedic implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(10):1554.

41. Meijer ST, Paulino Pereira NR, Nota SPFT, Ferrone ML, Schwab JH, Lozano Calderón SA. Factors associated with infection after reconstructive shoulder surgery for proximal humerus tumors. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(6):931-938. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.014.

42. Wagner ER, Houdek MT, Hernandez NM, Cofield RH, Sánchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW. Cement-within-cement technique in revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(8):1448-1453. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2017.01.013.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Different preoperative diagnoses lead to distinct patterns of bone loss in revision shoulder arthroplasty.

- A variety of techniques should be utilized to address the specific pathologies encountered.

- Advanced proximal humeral bone loss results in limited substrate available for humeral component fixation.

- Monoblock humeral stems can be used without allografts in cases with mild humeral bone loss.

- The revision of loose humeral stems dictates the use of large diaphyseal allografts in the majority of cases.

Treating Humeral Bone Loss in Shoulder Arthroplasty: Modular Humeral Components or Allografts

ABSTRACT