User login

Children born very prematurely at higher risk to struggle in secondary school

A new study of educational attainment among U.K. primary and secondary schoolchildren born prematurely now provides some reassurance about the longer-term outcomes for many of these children.

For the study, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, researchers from the University of Oxford with colleagues from the University of Leicester and City University, London, used data from 11,695 children in the population-based UK Millennium Cohort Study, which included children born in England from Sept. 1, 2000 to Aug. 31, 2001. They analyzed data on educational attainment in primary school, at age 11, for 6,950 pupils and in secondary school, at age 16, for 7,131 pupils.

Preterm birth is a known risk factor for developmental impairment, lower educational performance and reduced academic attainment, with the impact proportional to the degree of prematurity. Not every child born prematurely will experience learning or developmental challenges, but studies of children born before 34 weeks gestation have shown that they are more likely to have cognitive difficulties, particularly poorer reading and maths skills, at primary school, and to have special educational needs by the end of primary education.

Elevated risk of all preterm children in primary school

Until now, few studies have followed these children through secondary school or examined the full spectrum of gestational ages at birth. Yet as neonatal care advances and more premature babies now survive, an average primary class in the United Kingdom now includes two preterm children.

Among the primary school children overall, 17.7% had not achieved their expected level in English and mathematics at age 11. Children born very preterm, before 32 weeks or at 32-33 weeks gestation, were more than twice as likely as full term children to fail to meet these benchmarks, with adjusted relative risks of 2.06 and 2.13, respectively. Those born late preterm, at 34-36 weeks, or early term, at 37-38 weeks, were at lesser risk, with RRs of 1.18 and 1.21, respectively.

By the end of secondary school, 45.2% of pupils had not passed the benchmark of at least five General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examinations, including English and mathematics. The RR for children born very preterm, compared with full term children, was 1.26, with 60% of students in this group failing to achieve five GCSEs. However, children born at gestations between 32 and 38 weeks were not at elevated risk, compared with children born at full term.

Risk persists to secondary level only for very preterm children

A similar pattern was seen with English and mathematics analyzed separately, with no additional risk of not passing among children born at 32 weeks or above, but adjusted RRs of 1.33 for not passing English and 1.42 for not passing maths among pupils who had been born very preterm, compared with full term children.

“All children born before full term are more likely to have poorer attainment during primary school, compared with children born full term (39-41 weeks), but only children born very preterm (before 32 weeks) remain at risk of poor attainment at the end of secondary schooling,” the researchers concluded.

“Further studies are needed in order to confirm this result,” they acknowledge. They suggested their results could be explained by catch-up in academic attainment among children born moderately or late preterm or at early term. However, “very preterm children appear to be a high-risk group with persistent difficulties in terms of educational outcomes,” they said, noting that even this risk was of lower magnitude than the reduced attainment scores they found among pupils eligible for free school meals, meaning those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.

Extra educational support needed

The researchers concluded: “Children born very preterm may benefit from screening for cognitive and language difficulties prior to school entry to guide the provision of additional support during schooling.” In addition, those born very preterm “may require additional educational support throughout compulsory schooling.”

Commenting on the study, Caroline Lee-Davey, chief executive of premature baby charity Bliss, told this news organization: “Every child who is born premature is unique, and their development and achievements will be individual to them. However, these new findings are significant and add to our understanding of how prematurity is related to longer-term educational attainment, particularly for children who were born very preterm.”

“Most importantly, they highlight the need for all children who were born premature – and particularly those who were born before 32 weeks – to have access to early support. This means ensuring all eligible babies receive a follow-up check at 2 and 4 years as recommended by NICE and for early years and educational professionals to be aware of the relationship between premature birth and development.”

“We know how concerning these findings might be for families with babies and very young children right now. That’s why Bliss has developed a suite of information to support families as they make choices about their child’s education.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

A new study of educational attainment among U.K. primary and secondary schoolchildren born prematurely now provides some reassurance about the longer-term outcomes for many of these children.

For the study, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, researchers from the University of Oxford with colleagues from the University of Leicester and City University, London, used data from 11,695 children in the population-based UK Millennium Cohort Study, which included children born in England from Sept. 1, 2000 to Aug. 31, 2001. They analyzed data on educational attainment in primary school, at age 11, for 6,950 pupils and in secondary school, at age 16, for 7,131 pupils.

Preterm birth is a known risk factor for developmental impairment, lower educational performance and reduced academic attainment, with the impact proportional to the degree of prematurity. Not every child born prematurely will experience learning or developmental challenges, but studies of children born before 34 weeks gestation have shown that they are more likely to have cognitive difficulties, particularly poorer reading and maths skills, at primary school, and to have special educational needs by the end of primary education.

Elevated risk of all preterm children in primary school

Until now, few studies have followed these children through secondary school or examined the full spectrum of gestational ages at birth. Yet as neonatal care advances and more premature babies now survive, an average primary class in the United Kingdom now includes two preterm children.

Among the primary school children overall, 17.7% had not achieved their expected level in English and mathematics at age 11. Children born very preterm, before 32 weeks or at 32-33 weeks gestation, were more than twice as likely as full term children to fail to meet these benchmarks, with adjusted relative risks of 2.06 and 2.13, respectively. Those born late preterm, at 34-36 weeks, or early term, at 37-38 weeks, were at lesser risk, with RRs of 1.18 and 1.21, respectively.

By the end of secondary school, 45.2% of pupils had not passed the benchmark of at least five General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examinations, including English and mathematics. The RR for children born very preterm, compared with full term children, was 1.26, with 60% of students in this group failing to achieve five GCSEs. However, children born at gestations between 32 and 38 weeks were not at elevated risk, compared with children born at full term.

Risk persists to secondary level only for very preterm children

A similar pattern was seen with English and mathematics analyzed separately, with no additional risk of not passing among children born at 32 weeks or above, but adjusted RRs of 1.33 for not passing English and 1.42 for not passing maths among pupils who had been born very preterm, compared with full term children.

“All children born before full term are more likely to have poorer attainment during primary school, compared with children born full term (39-41 weeks), but only children born very preterm (before 32 weeks) remain at risk of poor attainment at the end of secondary schooling,” the researchers concluded.

“Further studies are needed in order to confirm this result,” they acknowledge. They suggested their results could be explained by catch-up in academic attainment among children born moderately or late preterm or at early term. However, “very preterm children appear to be a high-risk group with persistent difficulties in terms of educational outcomes,” they said, noting that even this risk was of lower magnitude than the reduced attainment scores they found among pupils eligible for free school meals, meaning those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.

Extra educational support needed

The researchers concluded: “Children born very preterm may benefit from screening for cognitive and language difficulties prior to school entry to guide the provision of additional support during schooling.” In addition, those born very preterm “may require additional educational support throughout compulsory schooling.”

Commenting on the study, Caroline Lee-Davey, chief executive of premature baby charity Bliss, told this news organization: “Every child who is born premature is unique, and their development and achievements will be individual to them. However, these new findings are significant and add to our understanding of how prematurity is related to longer-term educational attainment, particularly for children who were born very preterm.”

“Most importantly, they highlight the need for all children who were born premature – and particularly those who were born before 32 weeks – to have access to early support. This means ensuring all eligible babies receive a follow-up check at 2 and 4 years as recommended by NICE and for early years and educational professionals to be aware of the relationship between premature birth and development.”

“We know how concerning these findings might be for families with babies and very young children right now. That’s why Bliss has developed a suite of information to support families as they make choices about their child’s education.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

A new study of educational attainment among U.K. primary and secondary schoolchildren born prematurely now provides some reassurance about the longer-term outcomes for many of these children.

For the study, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, researchers from the University of Oxford with colleagues from the University of Leicester and City University, London, used data from 11,695 children in the population-based UK Millennium Cohort Study, which included children born in England from Sept. 1, 2000 to Aug. 31, 2001. They analyzed data on educational attainment in primary school, at age 11, for 6,950 pupils and in secondary school, at age 16, for 7,131 pupils.

Preterm birth is a known risk factor for developmental impairment, lower educational performance and reduced academic attainment, with the impact proportional to the degree of prematurity. Not every child born prematurely will experience learning or developmental challenges, but studies of children born before 34 weeks gestation have shown that they are more likely to have cognitive difficulties, particularly poorer reading and maths skills, at primary school, and to have special educational needs by the end of primary education.

Elevated risk of all preterm children in primary school

Until now, few studies have followed these children through secondary school or examined the full spectrum of gestational ages at birth. Yet as neonatal care advances and more premature babies now survive, an average primary class in the United Kingdom now includes two preterm children.

Among the primary school children overall, 17.7% had not achieved their expected level in English and mathematics at age 11. Children born very preterm, before 32 weeks or at 32-33 weeks gestation, were more than twice as likely as full term children to fail to meet these benchmarks, with adjusted relative risks of 2.06 and 2.13, respectively. Those born late preterm, at 34-36 weeks, or early term, at 37-38 weeks, were at lesser risk, with RRs of 1.18 and 1.21, respectively.

By the end of secondary school, 45.2% of pupils had not passed the benchmark of at least five General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examinations, including English and mathematics. The RR for children born very preterm, compared with full term children, was 1.26, with 60% of students in this group failing to achieve five GCSEs. However, children born at gestations between 32 and 38 weeks were not at elevated risk, compared with children born at full term.

Risk persists to secondary level only for very preterm children

A similar pattern was seen with English and mathematics analyzed separately, with no additional risk of not passing among children born at 32 weeks or above, but adjusted RRs of 1.33 for not passing English and 1.42 for not passing maths among pupils who had been born very preterm, compared with full term children.

“All children born before full term are more likely to have poorer attainment during primary school, compared with children born full term (39-41 weeks), but only children born very preterm (before 32 weeks) remain at risk of poor attainment at the end of secondary schooling,” the researchers concluded.

“Further studies are needed in order to confirm this result,” they acknowledge. They suggested their results could be explained by catch-up in academic attainment among children born moderately or late preterm or at early term. However, “very preterm children appear to be a high-risk group with persistent difficulties in terms of educational outcomes,” they said, noting that even this risk was of lower magnitude than the reduced attainment scores they found among pupils eligible for free school meals, meaning those from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.

Extra educational support needed

The researchers concluded: “Children born very preterm may benefit from screening for cognitive and language difficulties prior to school entry to guide the provision of additional support during schooling.” In addition, those born very preterm “may require additional educational support throughout compulsory schooling.”

Commenting on the study, Caroline Lee-Davey, chief executive of premature baby charity Bliss, told this news organization: “Every child who is born premature is unique, and their development and achievements will be individual to them. However, these new findings are significant and add to our understanding of how prematurity is related to longer-term educational attainment, particularly for children who were born very preterm.”

“Most importantly, they highlight the need for all children who were born premature – and particularly those who were born before 32 weeks – to have access to early support. This means ensuring all eligible babies receive a follow-up check at 2 and 4 years as recommended by NICE and for early years and educational professionals to be aware of the relationship between premature birth and development.”

“We know how concerning these findings might be for families with babies and very young children right now. That’s why Bliss has developed a suite of information to support families as they make choices about their child’s education.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

FROM PLOS ONE

Large study amplifies evidence of COVID vaccine safety in pregnancy

The research team wrote in the BMJ that their reassuring findings – drawn from a registry of all births in Ontario over an 8-month period – “can inform evidence-based decision-making” about COVID vaccination during pregnancy.

Previous research has found that pregnant patients are at higher risk of severe complications and death if they become infected with COVID and that vaccination before or during pregnancy prevents such outcomes and reduces the risk of newborn infection, noted Jeffrey Ecker, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

This new study “adds to a growing body of information arguing clearly and reassuringly that vaccination during pregnancy is not associated with complications during pregnancy,” said Dr. Ecker, who was not involved in the new study.

He added that it “should help obstetric providers further reassure those who are hesitant that vaccination is safe and best both for the pregnant patient and their pregnancy.”

Methods and results

For the new study, researchers tapped a provincial registry of all live and stillborn infants with a gestational age of at least 20 weeks or birth weight of at least 500 g. Unique health card numbers were used to link birth records to a database of COVID vaccinations.

Of 85,162 infants born from May through December of 2021, 43,099 (50.6%) were born to individuals who received at least one vaccine dose during pregnancy. Among those, 99.7% received an mRNA vaccine such as Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna.

Vaccination during pregnancy was not associated with greater risk of overall preterm birth (6.5% among vaccinated individuals versus 6.9% among unvaccinated; hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.08), spontaneous preterm birth (3.7% versus 4.4%; hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.03) or very preterm birth (0.59% versus 0.89%; hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.95).

Likewise, no increase was observed in the risk of an infant being small for gestational age at birth (9.1% versus 9.2%; hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.03).

The researchers observed a reduction in the risk of stillbirth, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Stillbirths occurred in 0.25% of vaccinated individuals, compared with 0.44% of unvaccinated individuals (hazard ratio, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51-0.84).

A reduced risk of stillbirth – albeit to a smaller degree – was also found in a Scandinavian registry study that included 28,506 babies born to individuals who were vaccinated during pregnancy.

“Collectively, the findings from these two studies are reassuring and are consistent with no increased risk of stillbirth after COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. In contrast, COVID-19 disease during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth,” the researchers wrote.

Findings did not vary by which mRNA vaccine a mother received, the number of doses she received, or the trimester in which a vaccine was given, the researchers reported.

Stillbirth findings will be ‘very reassuring’ for patients

The lead investigator, Deshayne Fell, PhD, said in an interview, the fact that the study comprised the entire population of pregnant people in Ontario during the study period “increases our confidence” about the validity and relevance of the findings for other geographic settings.

Dr. Fell, an associate professor in epidemiology and public health at the University of Ottawa and a scientist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, said the evaluation of stillbirth in particular, “a rare but devastating outcome,” will be “very reassuring and useful for clinical counseling.”

A limitation cited by the research team included a lack of data on vaccination prior to pregnancy.

In the new study, Dr, Ecker said, “Though the investigators were able to adjust for many variables they cannot be certain that some unmeasured variable that, accordingly, was not adjusted for does not hide a small risk. This seems very unlikely, however.”

The Canadian research team said similar studies of non-mRNA COVID vaccines “should be a research priority.” However, such studies are not underway in Canada, where only mRNA vaccines are used in pregnancy, Dr. Fell said.

This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Dr. Fell and Dr. Ecker reported no competing financial interests.

The research team wrote in the BMJ that their reassuring findings – drawn from a registry of all births in Ontario over an 8-month period – “can inform evidence-based decision-making” about COVID vaccination during pregnancy.

Previous research has found that pregnant patients are at higher risk of severe complications and death if they become infected with COVID and that vaccination before or during pregnancy prevents such outcomes and reduces the risk of newborn infection, noted Jeffrey Ecker, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

This new study “adds to a growing body of information arguing clearly and reassuringly that vaccination during pregnancy is not associated with complications during pregnancy,” said Dr. Ecker, who was not involved in the new study.

He added that it “should help obstetric providers further reassure those who are hesitant that vaccination is safe and best both for the pregnant patient and their pregnancy.”

Methods and results

For the new study, researchers tapped a provincial registry of all live and stillborn infants with a gestational age of at least 20 weeks or birth weight of at least 500 g. Unique health card numbers were used to link birth records to a database of COVID vaccinations.

Of 85,162 infants born from May through December of 2021, 43,099 (50.6%) were born to individuals who received at least one vaccine dose during pregnancy. Among those, 99.7% received an mRNA vaccine such as Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna.

Vaccination during pregnancy was not associated with greater risk of overall preterm birth (6.5% among vaccinated individuals versus 6.9% among unvaccinated; hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.08), spontaneous preterm birth (3.7% versus 4.4%; hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.03) or very preterm birth (0.59% versus 0.89%; hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.95).

Likewise, no increase was observed in the risk of an infant being small for gestational age at birth (9.1% versus 9.2%; hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.03).

The researchers observed a reduction in the risk of stillbirth, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Stillbirths occurred in 0.25% of vaccinated individuals, compared with 0.44% of unvaccinated individuals (hazard ratio, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51-0.84).

A reduced risk of stillbirth – albeit to a smaller degree – was also found in a Scandinavian registry study that included 28,506 babies born to individuals who were vaccinated during pregnancy.

“Collectively, the findings from these two studies are reassuring and are consistent with no increased risk of stillbirth after COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. In contrast, COVID-19 disease during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth,” the researchers wrote.

Findings did not vary by which mRNA vaccine a mother received, the number of doses she received, or the trimester in which a vaccine was given, the researchers reported.

Stillbirth findings will be ‘very reassuring’ for patients

The lead investigator, Deshayne Fell, PhD, said in an interview, the fact that the study comprised the entire population of pregnant people in Ontario during the study period “increases our confidence” about the validity and relevance of the findings for other geographic settings.

Dr. Fell, an associate professor in epidemiology and public health at the University of Ottawa and a scientist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, said the evaluation of stillbirth in particular, “a rare but devastating outcome,” will be “very reassuring and useful for clinical counseling.”

A limitation cited by the research team included a lack of data on vaccination prior to pregnancy.

In the new study, Dr, Ecker said, “Though the investigators were able to adjust for many variables they cannot be certain that some unmeasured variable that, accordingly, was not adjusted for does not hide a small risk. This seems very unlikely, however.”

The Canadian research team said similar studies of non-mRNA COVID vaccines “should be a research priority.” However, such studies are not underway in Canada, where only mRNA vaccines are used in pregnancy, Dr. Fell said.

This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Dr. Fell and Dr. Ecker reported no competing financial interests.

The research team wrote in the BMJ that their reassuring findings – drawn from a registry of all births in Ontario over an 8-month period – “can inform evidence-based decision-making” about COVID vaccination during pregnancy.

Previous research has found that pregnant patients are at higher risk of severe complications and death if they become infected with COVID and that vaccination before or during pregnancy prevents such outcomes and reduces the risk of newborn infection, noted Jeffrey Ecker, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

This new study “adds to a growing body of information arguing clearly and reassuringly that vaccination during pregnancy is not associated with complications during pregnancy,” said Dr. Ecker, who was not involved in the new study.

He added that it “should help obstetric providers further reassure those who are hesitant that vaccination is safe and best both for the pregnant patient and their pregnancy.”

Methods and results

For the new study, researchers tapped a provincial registry of all live and stillborn infants with a gestational age of at least 20 weeks or birth weight of at least 500 g. Unique health card numbers were used to link birth records to a database of COVID vaccinations.

Of 85,162 infants born from May through December of 2021, 43,099 (50.6%) were born to individuals who received at least one vaccine dose during pregnancy. Among those, 99.7% received an mRNA vaccine such as Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna.

Vaccination during pregnancy was not associated with greater risk of overall preterm birth (6.5% among vaccinated individuals versus 6.9% among unvaccinated; hazard ratio, 1.02; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.08), spontaneous preterm birth (3.7% versus 4.4%; hazard ratio, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.03) or very preterm birth (0.59% versus 0.89%; hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.95).

Likewise, no increase was observed in the risk of an infant being small for gestational age at birth (9.1% versus 9.2%; hazard ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.93-1.03).

The researchers observed a reduction in the risk of stillbirth, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Stillbirths occurred in 0.25% of vaccinated individuals, compared with 0.44% of unvaccinated individuals (hazard ratio, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51-0.84).

A reduced risk of stillbirth – albeit to a smaller degree – was also found in a Scandinavian registry study that included 28,506 babies born to individuals who were vaccinated during pregnancy.

“Collectively, the findings from these two studies are reassuring and are consistent with no increased risk of stillbirth after COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. In contrast, COVID-19 disease during pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth,” the researchers wrote.

Findings did not vary by which mRNA vaccine a mother received, the number of doses she received, or the trimester in which a vaccine was given, the researchers reported.

Stillbirth findings will be ‘very reassuring’ for patients

The lead investigator, Deshayne Fell, PhD, said in an interview, the fact that the study comprised the entire population of pregnant people in Ontario during the study period “increases our confidence” about the validity and relevance of the findings for other geographic settings.

Dr. Fell, an associate professor in epidemiology and public health at the University of Ottawa and a scientist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, said the evaluation of stillbirth in particular, “a rare but devastating outcome,” will be “very reassuring and useful for clinical counseling.”

A limitation cited by the research team included a lack of data on vaccination prior to pregnancy.

In the new study, Dr, Ecker said, “Though the investigators were able to adjust for many variables they cannot be certain that some unmeasured variable that, accordingly, was not adjusted for does not hide a small risk. This seems very unlikely, however.”

The Canadian research team said similar studies of non-mRNA COVID vaccines “should be a research priority.” However, such studies are not underway in Canada, where only mRNA vaccines are used in pregnancy, Dr. Fell said.

This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Dr. Fell and Dr. Ecker reported no competing financial interests.

FROM BMJ

Reliably solving complex problems

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is an engineering marvel. Costing over $10 billion, it should be. The project cost overrun was 900%. The launch was delayed by more than a decade. The Human Genome Project from 1990 to 2003 was completed slightly ahead of schedule and for less than the $4-$5 billion original estimates. This HGP success story is partly because of private entrepreneurial involvement. The Superconducting Super Collider in Texas spent $2 billion but never got off the ground. Successfully shepherding huge public projects like these involves the art of politics and management as well as science.

Whatever the earlier missteps, the JWST project is now performing above expectations. It has launched, taken up residence a million miles from Earth, deployed its mirrors (a process that had more than 300 possible single points of failure, any one of which would reduce the thing to scrap metal), and been calibrated. The JWST has even been dented by a micrometeoroid – sort of like a parking lot ding on the door of your brand new car. The first images are visually amazing and producing new scientific insights. This is a pinnacle of scientific achievement.

What characteristics enable such an achievement? How do we foster those same characteristics in the practice of medicine and medical research? Will the success of the JWST increase and restore the public’s trust in science and scientists?

After all the bickering over vaccines and masks for the past 2+ years, medical science could use a boost. The gravitas of scientists, and indeed all experts, has diminished over the 5 decades since humans walked on the moon. It has been harmed by mercenary scientists who sought to sow doubt about whether smoking caused cancer and whether fossil fuels created climate change. No proof was needed, just doubt.

The trust in science has also been harmed by the vast amount of published medical research that is wrong. An effort was made 20 years ago to rid research of the bias of taking money from drug companies. To my observation, that change produced only a small benefit that has been overwhelmed by the unintended harms. The large, well-funded academic labs of full-time researchers have been replaced with unfunded, undertrained, and inadequately supported part-time junior faculty trying to publish enough articles to be promoted. In my opinion, this change is worse than funding from Big Pharma. (Disclosure – I worked in industry prior to graduate school.)

The pressure to publish reduces skepticism, so more incorrect data are published. The small size of these amateur studies produces unconvincing conclusions that feed an industry of meta-analysis that tries to overcome the deficiencies of the individual studies. This fragmented, biased approach is not how you build, launch, deploy, and operate the JWST, which requires very high reliability.

This approach is not working well for pediatrics either. I look at the history of the recommended workup of the febrile young infant from the 1980s until today. I see constant changes to the guidelines but no real progress toward a validated, evidence-based approach. A similar history is behind treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. In the 1994 publication, there was a movement toward being less aggressive. The 2004 and 2009 editions increased the frequency of screening and phototherapy. Now, the 2022 guidelines have moved in the direction we were headed in the 1990s. The workup of infants and children with possible urinary tract infections has undergone a similar trajectory. So has the screening for neonatal herpes infections. The practice changes are more like Brownian motion than real progress. This inconsistency has led me to be skeptical of the process the American Academy of Pediatrics uses to create guidelines.

Part of solving complex problems is allowing all stakeholders’ voices to be heard. On Jan. 28, 1986, seconds after liftoff, the space shuttle Challenger exploded. In the aftermath, it was determined that some engineers had expressed concern about the very cold weather that morning. The rubber in the O-ring would not be as flexible as designed. Their objection was not listened to. The O-ring failed, the fuel tank exploded, and the ship and crew were lost. It is a lesson many engineers of my generation took to heart. Do not suppress voices.

For example, 1 year ago (September 2021), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists published a position statement, “Recognising and addressing the mental health needs of people experiencing gender dysphoria/gender incongruence.” The statement expressed concern about the marked increase in incidence of rapid-onset gender dysphoria and therefore urged more thorough assessment by psychiatry before embarking on puberty-blocking therapies. The RANZCP position is at variance with recent trends in the United States. The topic was censored at the 2021 AAP national conference. Lately, I have heard the words disinformation and homophobic used to describe my RANZCP colleagues. I have been comparing AAP, Britain’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne guidelines for 20 years. The variation is enlightening. I do not know the correct answer to treating gender dysphoria, but I know suppressing viewpoints and debate leads to exploding spaceships.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is an engineering marvel. Costing over $10 billion, it should be. The project cost overrun was 900%. The launch was delayed by more than a decade. The Human Genome Project from 1990 to 2003 was completed slightly ahead of schedule and for less than the $4-$5 billion original estimates. This HGP success story is partly because of private entrepreneurial involvement. The Superconducting Super Collider in Texas spent $2 billion but never got off the ground. Successfully shepherding huge public projects like these involves the art of politics and management as well as science.

Whatever the earlier missteps, the JWST project is now performing above expectations. It has launched, taken up residence a million miles from Earth, deployed its mirrors (a process that had more than 300 possible single points of failure, any one of which would reduce the thing to scrap metal), and been calibrated. The JWST has even been dented by a micrometeoroid – sort of like a parking lot ding on the door of your brand new car. The first images are visually amazing and producing new scientific insights. This is a pinnacle of scientific achievement.

What characteristics enable such an achievement? How do we foster those same characteristics in the practice of medicine and medical research? Will the success of the JWST increase and restore the public’s trust in science and scientists?

After all the bickering over vaccines and masks for the past 2+ years, medical science could use a boost. The gravitas of scientists, and indeed all experts, has diminished over the 5 decades since humans walked on the moon. It has been harmed by mercenary scientists who sought to sow doubt about whether smoking caused cancer and whether fossil fuels created climate change. No proof was needed, just doubt.

The trust in science has also been harmed by the vast amount of published medical research that is wrong. An effort was made 20 years ago to rid research of the bias of taking money from drug companies. To my observation, that change produced only a small benefit that has been overwhelmed by the unintended harms. The large, well-funded academic labs of full-time researchers have been replaced with unfunded, undertrained, and inadequately supported part-time junior faculty trying to publish enough articles to be promoted. In my opinion, this change is worse than funding from Big Pharma. (Disclosure – I worked in industry prior to graduate school.)

The pressure to publish reduces skepticism, so more incorrect data are published. The small size of these amateur studies produces unconvincing conclusions that feed an industry of meta-analysis that tries to overcome the deficiencies of the individual studies. This fragmented, biased approach is not how you build, launch, deploy, and operate the JWST, which requires very high reliability.

This approach is not working well for pediatrics either. I look at the history of the recommended workup of the febrile young infant from the 1980s until today. I see constant changes to the guidelines but no real progress toward a validated, evidence-based approach. A similar history is behind treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. In the 1994 publication, there was a movement toward being less aggressive. The 2004 and 2009 editions increased the frequency of screening and phototherapy. Now, the 2022 guidelines have moved in the direction we were headed in the 1990s. The workup of infants and children with possible urinary tract infections has undergone a similar trajectory. So has the screening for neonatal herpes infections. The practice changes are more like Brownian motion than real progress. This inconsistency has led me to be skeptical of the process the American Academy of Pediatrics uses to create guidelines.

Part of solving complex problems is allowing all stakeholders’ voices to be heard. On Jan. 28, 1986, seconds after liftoff, the space shuttle Challenger exploded. In the aftermath, it was determined that some engineers had expressed concern about the very cold weather that morning. The rubber in the O-ring would not be as flexible as designed. Their objection was not listened to. The O-ring failed, the fuel tank exploded, and the ship and crew were lost. It is a lesson many engineers of my generation took to heart. Do not suppress voices.

For example, 1 year ago (September 2021), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists published a position statement, “Recognising and addressing the mental health needs of people experiencing gender dysphoria/gender incongruence.” The statement expressed concern about the marked increase in incidence of rapid-onset gender dysphoria and therefore urged more thorough assessment by psychiatry before embarking on puberty-blocking therapies. The RANZCP position is at variance with recent trends in the United States. The topic was censored at the 2021 AAP national conference. Lately, I have heard the words disinformation and homophobic used to describe my RANZCP colleagues. I have been comparing AAP, Britain’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne guidelines for 20 years. The variation is enlightening. I do not know the correct answer to treating gender dysphoria, but I know suppressing viewpoints and debate leads to exploding spaceships.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is an engineering marvel. Costing over $10 billion, it should be. The project cost overrun was 900%. The launch was delayed by more than a decade. The Human Genome Project from 1990 to 2003 was completed slightly ahead of schedule and for less than the $4-$5 billion original estimates. This HGP success story is partly because of private entrepreneurial involvement. The Superconducting Super Collider in Texas spent $2 billion but never got off the ground. Successfully shepherding huge public projects like these involves the art of politics and management as well as science.

Whatever the earlier missteps, the JWST project is now performing above expectations. It has launched, taken up residence a million miles from Earth, deployed its mirrors (a process that had more than 300 possible single points of failure, any one of which would reduce the thing to scrap metal), and been calibrated. The JWST has even been dented by a micrometeoroid – sort of like a parking lot ding on the door of your brand new car. The first images are visually amazing and producing new scientific insights. This is a pinnacle of scientific achievement.

What characteristics enable such an achievement? How do we foster those same characteristics in the practice of medicine and medical research? Will the success of the JWST increase and restore the public’s trust in science and scientists?

After all the bickering over vaccines and masks for the past 2+ years, medical science could use a boost. The gravitas of scientists, and indeed all experts, has diminished over the 5 decades since humans walked on the moon. It has been harmed by mercenary scientists who sought to sow doubt about whether smoking caused cancer and whether fossil fuels created climate change. No proof was needed, just doubt.

The trust in science has also been harmed by the vast amount of published medical research that is wrong. An effort was made 20 years ago to rid research of the bias of taking money from drug companies. To my observation, that change produced only a small benefit that has been overwhelmed by the unintended harms. The large, well-funded academic labs of full-time researchers have been replaced with unfunded, undertrained, and inadequately supported part-time junior faculty trying to publish enough articles to be promoted. In my opinion, this change is worse than funding from Big Pharma. (Disclosure – I worked in industry prior to graduate school.)

The pressure to publish reduces skepticism, so more incorrect data are published. The small size of these amateur studies produces unconvincing conclusions that feed an industry of meta-analysis that tries to overcome the deficiencies of the individual studies. This fragmented, biased approach is not how you build, launch, deploy, and operate the JWST, which requires very high reliability.

This approach is not working well for pediatrics either. I look at the history of the recommended workup of the febrile young infant from the 1980s until today. I see constant changes to the guidelines but no real progress toward a validated, evidence-based approach. A similar history is behind treatment of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. In the 1994 publication, there was a movement toward being less aggressive. The 2004 and 2009 editions increased the frequency of screening and phototherapy. Now, the 2022 guidelines have moved in the direction we were headed in the 1990s. The workup of infants and children with possible urinary tract infections has undergone a similar trajectory. So has the screening for neonatal herpes infections. The practice changes are more like Brownian motion than real progress. This inconsistency has led me to be skeptical of the process the American Academy of Pediatrics uses to create guidelines.

Part of solving complex problems is allowing all stakeholders’ voices to be heard. On Jan. 28, 1986, seconds after liftoff, the space shuttle Challenger exploded. In the aftermath, it was determined that some engineers had expressed concern about the very cold weather that morning. The rubber in the O-ring would not be as flexible as designed. Their objection was not listened to. The O-ring failed, the fuel tank exploded, and the ship and crew were lost. It is a lesson many engineers of my generation took to heart. Do not suppress voices.

For example, 1 year ago (September 2021), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists published a position statement, “Recognising and addressing the mental health needs of people experiencing gender dysphoria/gender incongruence.” The statement expressed concern about the marked increase in incidence of rapid-onset gender dysphoria and therefore urged more thorough assessment by psychiatry before embarking on puberty-blocking therapies. The RANZCP position is at variance with recent trends in the United States. The topic was censored at the 2021 AAP national conference. Lately, I have heard the words disinformation and homophobic used to describe my RANZCP colleagues. I have been comparing AAP, Britain’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne guidelines for 20 years. The variation is enlightening. I do not know the correct answer to treating gender dysphoria, but I know suppressing viewpoints and debate leads to exploding spaceships.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

FDA approves first gene therapy, betibeglogene autotemcel (Zynteglo), for beta-thalassemia

Betibeglogene autotemcel, a one-time gene therapy, represents a potential cure in which functional copies of the mutated gene are inserted into patients’ hematopoietic stem cells via a replication-defective lentivirus.

“Today’s approval is an important advance in the treatment of beta-thalassemia, particularly in individuals who require ongoing red blood cell transfusions,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA press release. “Given the potential health complications associated with this serious disease, this action highlights the FDA’s continued commitment to supporting development of innovative therapies for patients who have limited treatment options.”

The approval was based on phase 3 trials, in which 89% of 41 patients aged 4-34 years who received the therapy maintained normal or near-normal hemoglobin levels and didn’t need transfusions for at least a year. The patients were as young as age 4, maker Bluebird Bio said in a press release.

FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee unanimously recommended approval in June. The gene therapy had been approved in Europe, where it carried a price tag of about $1.8 million, but Bluebird pulled it from the market in 2021 because of problems with reimbursement.

“The decision to discontinue operations in Europe resulted from prolonged negotiations with European payers and challenges to achieving appropriate value recognition and market access,” the company said in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

The projected price in the United States is even higher: $2.1 million.

But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an influential Boston-based nonprofit organization that specializes in medical cost-effectiveness analyses, concluded in June that, “given the high annual costs of standard care ... this new treatment meets commonly accepted value thresholds at an anticipated price of $2.1 million,” particularly with Bluebird’s proposal to pay back 80% of the cost if patients need a transfusion within 5 years.

The company is planning an October 2022 launch and estimates the U.S. market for betibeglogene autotemcel to be about 1,500 patients.

Adverse events in studies were “infrequent and consisted primarily of nonserious infusion-related reactions,” such as abdominal pain, hot flush, dyspnea, tachycardia, noncardiac chest pain, and cytopenias, including thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia. One case of thrombocytopenia was considered serious but resolved, according to the company.

Most of the serious adverse events were related to hematopoietic stem cell collection and the busulfan conditioning regimen. Insertional oncogenesis and/or cancer have been reported with Bluebird’s other gene therapy products, but no cases have been associated with betibeglogene autotemcel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Betibeglogene autotemcel, a one-time gene therapy, represents a potential cure in which functional copies of the mutated gene are inserted into patients’ hematopoietic stem cells via a replication-defective lentivirus.

“Today’s approval is an important advance in the treatment of beta-thalassemia, particularly in individuals who require ongoing red blood cell transfusions,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA press release. “Given the potential health complications associated with this serious disease, this action highlights the FDA’s continued commitment to supporting development of innovative therapies for patients who have limited treatment options.”

The approval was based on phase 3 trials, in which 89% of 41 patients aged 4-34 years who received the therapy maintained normal or near-normal hemoglobin levels and didn’t need transfusions for at least a year. The patients were as young as age 4, maker Bluebird Bio said in a press release.

FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee unanimously recommended approval in June. The gene therapy had been approved in Europe, where it carried a price tag of about $1.8 million, but Bluebird pulled it from the market in 2021 because of problems with reimbursement.

“The decision to discontinue operations in Europe resulted from prolonged negotiations with European payers and challenges to achieving appropriate value recognition and market access,” the company said in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

The projected price in the United States is even higher: $2.1 million.

But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an influential Boston-based nonprofit organization that specializes in medical cost-effectiveness analyses, concluded in June that, “given the high annual costs of standard care ... this new treatment meets commonly accepted value thresholds at an anticipated price of $2.1 million,” particularly with Bluebird’s proposal to pay back 80% of the cost if patients need a transfusion within 5 years.

The company is planning an October 2022 launch and estimates the U.S. market for betibeglogene autotemcel to be about 1,500 patients.

Adverse events in studies were “infrequent and consisted primarily of nonserious infusion-related reactions,” such as abdominal pain, hot flush, dyspnea, tachycardia, noncardiac chest pain, and cytopenias, including thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia. One case of thrombocytopenia was considered serious but resolved, according to the company.

Most of the serious adverse events were related to hematopoietic stem cell collection and the busulfan conditioning regimen. Insertional oncogenesis and/or cancer have been reported with Bluebird’s other gene therapy products, but no cases have been associated with betibeglogene autotemcel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Betibeglogene autotemcel, a one-time gene therapy, represents a potential cure in which functional copies of the mutated gene are inserted into patients’ hematopoietic stem cells via a replication-defective lentivirus.

“Today’s approval is an important advance in the treatment of beta-thalassemia, particularly in individuals who require ongoing red blood cell transfusions,” Peter Marks, MD, PhD, director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said in an FDA press release. “Given the potential health complications associated with this serious disease, this action highlights the FDA’s continued commitment to supporting development of innovative therapies for patients who have limited treatment options.”

The approval was based on phase 3 trials, in which 89% of 41 patients aged 4-34 years who received the therapy maintained normal or near-normal hemoglobin levels and didn’t need transfusions for at least a year. The patients were as young as age 4, maker Bluebird Bio said in a press release.

FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee unanimously recommended approval in June. The gene therapy had been approved in Europe, where it carried a price tag of about $1.8 million, but Bluebird pulled it from the market in 2021 because of problems with reimbursement.

“The decision to discontinue operations in Europe resulted from prolonged negotiations with European payers and challenges to achieving appropriate value recognition and market access,” the company said in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

The projected price in the United States is even higher: $2.1 million.

But the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, an influential Boston-based nonprofit organization that specializes in medical cost-effectiveness analyses, concluded in June that, “given the high annual costs of standard care ... this new treatment meets commonly accepted value thresholds at an anticipated price of $2.1 million,” particularly with Bluebird’s proposal to pay back 80% of the cost if patients need a transfusion within 5 years.

The company is planning an October 2022 launch and estimates the U.S. market for betibeglogene autotemcel to be about 1,500 patients.

Adverse events in studies were “infrequent and consisted primarily of nonserious infusion-related reactions,” such as abdominal pain, hot flush, dyspnea, tachycardia, noncardiac chest pain, and cytopenias, including thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and neutropenia. One case of thrombocytopenia was considered serious but resolved, according to the company.

Most of the serious adverse events were related to hematopoietic stem cell collection and the busulfan conditioning regimen. Insertional oncogenesis and/or cancer have been reported with Bluebird’s other gene therapy products, but no cases have been associated with betibeglogene autotemcel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves adalimumab-bwwd biosimilar (Hadlima) in high-concentration form

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved a citrate-free, high-concentration formulation of adalimumab-bwwd (Hadlima), the manufacturer, Samsung Bioepis, and its commercialization partner Organon said in an announcement.

Hadlima is a biosimilar of the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor reference product adalimumab (Humira).

Hadlima was first approved in July 2019 in a citrated, 50-mg/mL formulation. The new citrate-free, 100-mg/mL version will be available in prefilled syringe and autoinjector options.

The 100-mg/mL formulation is indicated for the same seven conditions as its 50-mg/mL counterpart: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The approval was based on clinical data from a randomized, single-blind, two-arm, parallel group, single-dose study that compared the pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the 100-mg/mL and 50-mg/mL formulations of Hadlima in healthy volunteers.

Both low- and high-concentration formulations of Humira are currently marketed in the United States. Organon said that it expects to market Hadlima in the United States on or after July 1, 2023, in accordance with a licensing agreement with AbbVie.

The prescribing information for Hadlima includes specific warnings and areas of concern. The drug should not be administered to individuals who are known to be hypersensitive to adalimumab. The drug may lower the ability of the immune system to fight infections and may increase risk of infections, including serious infections leading to hospitalization or death, such as tuberculosis, bacterial sepsis, invasive fungal infections (such as histoplasmosis), and infections attributable to other opportunistic pathogens.

A test for latent TB infection should be given before administration, and treatment of TB should begin before administration of Hadlima.

Patients taking Hadlima should not take a live vaccine.

The most common adverse effects (incidence > 10%) include infections (for example, upper respiratory infections, sinusitis), injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved a citrate-free, high-concentration formulation of adalimumab-bwwd (Hadlima), the manufacturer, Samsung Bioepis, and its commercialization partner Organon said in an announcement.

Hadlima is a biosimilar of the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor reference product adalimumab (Humira).

Hadlima was first approved in July 2019 in a citrated, 50-mg/mL formulation. The new citrate-free, 100-mg/mL version will be available in prefilled syringe and autoinjector options.

The 100-mg/mL formulation is indicated for the same seven conditions as its 50-mg/mL counterpart: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The approval was based on clinical data from a randomized, single-blind, two-arm, parallel group, single-dose study that compared the pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the 100-mg/mL and 50-mg/mL formulations of Hadlima in healthy volunteers.

Both low- and high-concentration formulations of Humira are currently marketed in the United States. Organon said that it expects to market Hadlima in the United States on or after July 1, 2023, in accordance with a licensing agreement with AbbVie.

The prescribing information for Hadlima includes specific warnings and areas of concern. The drug should not be administered to individuals who are known to be hypersensitive to adalimumab. The drug may lower the ability of the immune system to fight infections and may increase risk of infections, including serious infections leading to hospitalization or death, such as tuberculosis, bacterial sepsis, invasive fungal infections (such as histoplasmosis), and infections attributable to other opportunistic pathogens.

A test for latent TB infection should be given before administration, and treatment of TB should begin before administration of Hadlima.

Patients taking Hadlima should not take a live vaccine.

The most common adverse effects (incidence > 10%) include infections (for example, upper respiratory infections, sinusitis), injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration today approved a citrate-free, high-concentration formulation of adalimumab-bwwd (Hadlima), the manufacturer, Samsung Bioepis, and its commercialization partner Organon said in an announcement.

Hadlima is a biosimilar of the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor reference product adalimumab (Humira).

Hadlima was first approved in July 2019 in a citrated, 50-mg/mL formulation. The new citrate-free, 100-mg/mL version will be available in prefilled syringe and autoinjector options.

The 100-mg/mL formulation is indicated for the same seven conditions as its 50-mg/mL counterpart: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The approval was based on clinical data from a randomized, single-blind, two-arm, parallel group, single-dose study that compared the pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the 100-mg/mL and 50-mg/mL formulations of Hadlima in healthy volunteers.

Both low- and high-concentration formulations of Humira are currently marketed in the United States. Organon said that it expects to market Hadlima in the United States on or after July 1, 2023, in accordance with a licensing agreement with AbbVie.

The prescribing information for Hadlima includes specific warnings and areas of concern. The drug should not be administered to individuals who are known to be hypersensitive to adalimumab. The drug may lower the ability of the immune system to fight infections and may increase risk of infections, including serious infections leading to hospitalization or death, such as tuberculosis, bacterial sepsis, invasive fungal infections (such as histoplasmosis), and infections attributable to other opportunistic pathogens.

A test for latent TB infection should be given before administration, and treatment of TB should begin before administration of Hadlima.

Patients taking Hadlima should not take a live vaccine.

The most common adverse effects (incidence > 10%) include infections (for example, upper respiratory infections, sinusitis), injection site reactions, headache, and rash.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians at odds over gender-affirming care for trans kids

Some members of the American Academy of Pediatrics say its association leadership is blocking discussion about a resolution asking for a “rigorous systematic review” of gender-affirming care guidelines.

At issue is 2018 guidance that states children can undergo hormonal therapy after they are deemed appropriate candidates following a thorough mental health evaluation.

Critics say minors under age 18 may be getting “fast-tracked” to hormonal treatment too quickly or inappropriately and can end up regretting the decision and facing medical conditions like sterility.

Five AAP members, which has a total membership of around 67,000 pediatricians in the United States and Canada, this year penned Resolution 27, calling for a possible update of the guidelines following consultation with stakeholders that include mental health and medical clinicians, parents, and patients “with diverse views and experiences.”

Those members and others in written comments on a members-only website accuse the AAP of deliberately silencing debate on the issue and changing resolution rules. Any AAP member can submit a resolution for consideration by the group’s leadership at its annual policy meeting.

This year, the AAP sent an email to members stating it would not allow comments on resolutions that had not been “sponsored” by one of the group’s 66 chapters or 88 internal committees, councils, or sections.

That’s why comments were not allowed on Resolution 27, said Mark Del Monte, the AAP’s CEO. A second attempt to get sponsorship during the annual leadership forum, held earlier this month in Chicago, also failed, he noted. Mr. Del Monte told this news organization that changes to the resolution process are made every year and that no rule changes were directly associated with Resolution 27.

But one of the resolution’s authors said there was sponsorship when members first drafted the suggestion. Julia Mason, MD, a board member for the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine and a pediatrician in private practice in Gresham, Ore., says an AAP chapter president agreed to second Resolution 27 but backed off after attending a different AAP meeting. Dr. Mason did not name the member.

On Aug. 10, AAP President Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, wrote in a blog on the AAP website – after the AAP leadership meeting in Chicago – that the lack of sponsorship “meant no one was willing to support their proposal.”

The AAP Leadership Council’s 154 voting entities approved 48 resolutions at the meeting, all of which will be referred to the AAP Board of Directors for potential, but not definite, action as the Board only takes resolutions under advisement, Mr. Del Monte notes.

In an email allowing members to comment on a resolution (number 28) regarding education support for caring for transgender patients, 23 chose to support Resolution 27 instead.

“I am wholeheartedly in support of Resolution 27, which interestingly has been removed from the list of resolutions for member comment,” one comment read. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence-based education with regard to care for transgender individuals.”

“We don’t need a formal resolution to look at the evidence around the care of transgender young people. Evaluating the evidence behind our recommendations, which the unsponsored resolution called for, is a routine part of the Academy’s policy-writing process,” wrote Dr. Szilagyi in her blog.

Mr. Del Monte says that “the 2018 policy is under review now.”

So far, “the evidence that we have seen reinforces our policy that gender-affirming care is the correct approach,” Mr. Del Monte stresses. “It is supported by every mainstream medical society in the world and is the standard of care,” he maintains.

Among those societies is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which in the draft of its latest Standards of Care (SOC8) – the first new guidance on the issue for 10 years – reportedly lowers the age for “top surgery” to 15 years.

The final SOC8 will most likely be published to coincide with WPATH’s annual meeting in September in Montreal.

Opponents plan to protest outside the AAP’s annual meeting, in Anaheim in October, Dr. Mason says.

“I’m concerned that kids with a transient gender identity are being funneled into medicalization that does not serve them,” Dr. Mason says. “I am worried that the trans identity is valued over the possibility of desistance,” she adds, admitting that her goal is to have fewer children transition gender.

Last summer, AAP found itself in hot water on the same topic when it barred SEGM from having a booth at the AAP annual meeting in 2021, as reported by this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some members of the American Academy of Pediatrics say its association leadership is blocking discussion about a resolution asking for a “rigorous systematic review” of gender-affirming care guidelines.

At issue is 2018 guidance that states children can undergo hormonal therapy after they are deemed appropriate candidates following a thorough mental health evaluation.

Critics say minors under age 18 may be getting “fast-tracked” to hormonal treatment too quickly or inappropriately and can end up regretting the decision and facing medical conditions like sterility.

Five AAP members, which has a total membership of around 67,000 pediatricians in the United States and Canada, this year penned Resolution 27, calling for a possible update of the guidelines following consultation with stakeholders that include mental health and medical clinicians, parents, and patients “with diverse views and experiences.”

Those members and others in written comments on a members-only website accuse the AAP of deliberately silencing debate on the issue and changing resolution rules. Any AAP member can submit a resolution for consideration by the group’s leadership at its annual policy meeting.

This year, the AAP sent an email to members stating it would not allow comments on resolutions that had not been “sponsored” by one of the group’s 66 chapters or 88 internal committees, councils, or sections.

That’s why comments were not allowed on Resolution 27, said Mark Del Monte, the AAP’s CEO. A second attempt to get sponsorship during the annual leadership forum, held earlier this month in Chicago, also failed, he noted. Mr. Del Monte told this news organization that changes to the resolution process are made every year and that no rule changes were directly associated with Resolution 27.

But one of the resolution’s authors said there was sponsorship when members first drafted the suggestion. Julia Mason, MD, a board member for the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine and a pediatrician in private practice in Gresham, Ore., says an AAP chapter president agreed to second Resolution 27 but backed off after attending a different AAP meeting. Dr. Mason did not name the member.

On Aug. 10, AAP President Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, wrote in a blog on the AAP website – after the AAP leadership meeting in Chicago – that the lack of sponsorship “meant no one was willing to support their proposal.”

The AAP Leadership Council’s 154 voting entities approved 48 resolutions at the meeting, all of which will be referred to the AAP Board of Directors for potential, but not definite, action as the Board only takes resolutions under advisement, Mr. Del Monte notes.

In an email allowing members to comment on a resolution (number 28) regarding education support for caring for transgender patients, 23 chose to support Resolution 27 instead.

“I am wholeheartedly in support of Resolution 27, which interestingly has been removed from the list of resolutions for member comment,” one comment read. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence-based education with regard to care for transgender individuals.”

“We don’t need a formal resolution to look at the evidence around the care of transgender young people. Evaluating the evidence behind our recommendations, which the unsponsored resolution called for, is a routine part of the Academy’s policy-writing process,” wrote Dr. Szilagyi in her blog.

Mr. Del Monte says that “the 2018 policy is under review now.”

So far, “the evidence that we have seen reinforces our policy that gender-affirming care is the correct approach,” Mr. Del Monte stresses. “It is supported by every mainstream medical society in the world and is the standard of care,” he maintains.

Among those societies is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which in the draft of its latest Standards of Care (SOC8) – the first new guidance on the issue for 10 years – reportedly lowers the age for “top surgery” to 15 years.

The final SOC8 will most likely be published to coincide with WPATH’s annual meeting in September in Montreal.

Opponents plan to protest outside the AAP’s annual meeting, in Anaheim in October, Dr. Mason says.

“I’m concerned that kids with a transient gender identity are being funneled into medicalization that does not serve them,” Dr. Mason says. “I am worried that the trans identity is valued over the possibility of desistance,” she adds, admitting that her goal is to have fewer children transition gender.

Last summer, AAP found itself in hot water on the same topic when it barred SEGM from having a booth at the AAP annual meeting in 2021, as reported by this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some members of the American Academy of Pediatrics say its association leadership is blocking discussion about a resolution asking for a “rigorous systematic review” of gender-affirming care guidelines.

At issue is 2018 guidance that states children can undergo hormonal therapy after they are deemed appropriate candidates following a thorough mental health evaluation.

Critics say minors under age 18 may be getting “fast-tracked” to hormonal treatment too quickly or inappropriately and can end up regretting the decision and facing medical conditions like sterility.

Five AAP members, which has a total membership of around 67,000 pediatricians in the United States and Canada, this year penned Resolution 27, calling for a possible update of the guidelines following consultation with stakeholders that include mental health and medical clinicians, parents, and patients “with diverse views and experiences.”

Those members and others in written comments on a members-only website accuse the AAP of deliberately silencing debate on the issue and changing resolution rules. Any AAP member can submit a resolution for consideration by the group’s leadership at its annual policy meeting.

This year, the AAP sent an email to members stating it would not allow comments on resolutions that had not been “sponsored” by one of the group’s 66 chapters or 88 internal committees, councils, or sections.

That’s why comments were not allowed on Resolution 27, said Mark Del Monte, the AAP’s CEO. A second attempt to get sponsorship during the annual leadership forum, held earlier this month in Chicago, also failed, he noted. Mr. Del Monte told this news organization that changes to the resolution process are made every year and that no rule changes were directly associated with Resolution 27.

But one of the resolution’s authors said there was sponsorship when members first drafted the suggestion. Julia Mason, MD, a board member for the Society for Evidence-based Gender Medicine and a pediatrician in private practice in Gresham, Ore., says an AAP chapter president agreed to second Resolution 27 but backed off after attending a different AAP meeting. Dr. Mason did not name the member.

On Aug. 10, AAP President Moira Szilagyi, MD, PhD, wrote in a blog on the AAP website – after the AAP leadership meeting in Chicago – that the lack of sponsorship “meant no one was willing to support their proposal.”

The AAP Leadership Council’s 154 voting entities approved 48 resolutions at the meeting, all of which will be referred to the AAP Board of Directors for potential, but not definite, action as the Board only takes resolutions under advisement, Mr. Del Monte notes.

In an email allowing members to comment on a resolution (number 28) regarding education support for caring for transgender patients, 23 chose to support Resolution 27 instead.

“I am wholeheartedly in support of Resolution 27, which interestingly has been removed from the list of resolutions for member comment,” one comment read. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence-based education with regard to care for transgender individuals.”

“We don’t need a formal resolution to look at the evidence around the care of transgender young people. Evaluating the evidence behind our recommendations, which the unsponsored resolution called for, is a routine part of the Academy’s policy-writing process,” wrote Dr. Szilagyi in her blog.

Mr. Del Monte says that “the 2018 policy is under review now.”

So far, “the evidence that we have seen reinforces our policy that gender-affirming care is the correct approach,” Mr. Del Monte stresses. “It is supported by every mainstream medical society in the world and is the standard of care,” he maintains.

Among those societies is the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which in the draft of its latest Standards of Care (SOC8) – the first new guidance on the issue for 10 years – reportedly lowers the age for “top surgery” to 15 years.

The final SOC8 will most likely be published to coincide with WPATH’s annual meeting in September in Montreal.

Opponents plan to protest outside the AAP’s annual meeting, in Anaheim in October, Dr. Mason says.

“I’m concerned that kids with a transient gender identity are being funneled into medicalization that does not serve them,” Dr. Mason says. “I am worried that the trans identity is valued over the possibility of desistance,” she adds, admitting that her goal is to have fewer children transition gender.

Last summer, AAP found itself in hot water on the same topic when it barred SEGM from having a booth at the AAP annual meeting in 2021, as reported by this news organization.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

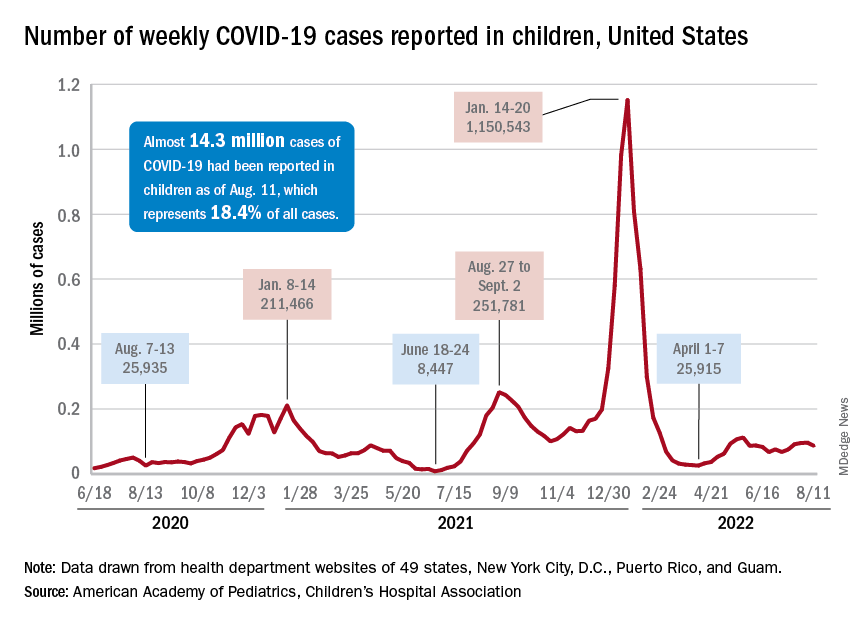

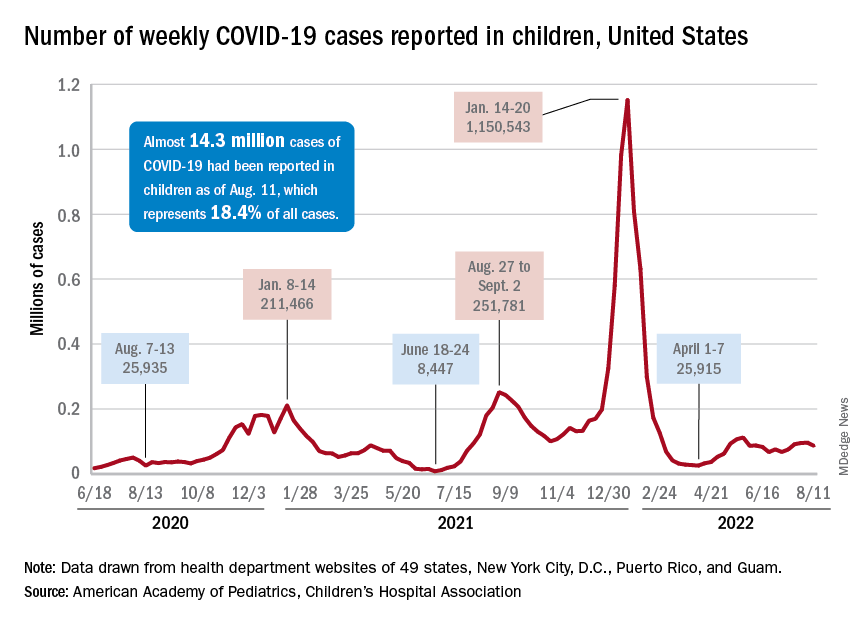

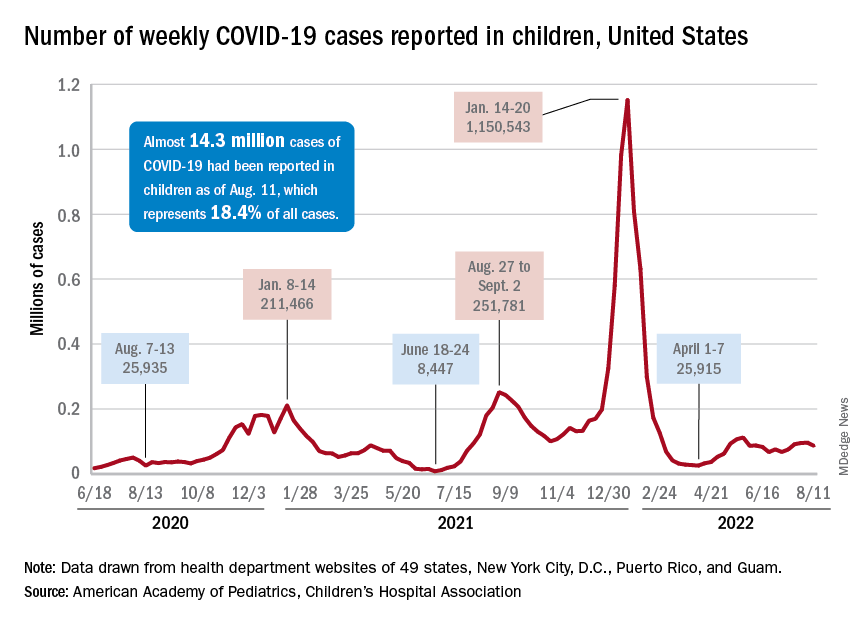

Children and COVID: ED visits and new admissions change course

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.

, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. For some historical perspective, the latest weekly count falls below last year’s Delta surge figure of 121,000 (Aug. 6-12) but above the summer 2020 total of 26,000 (Aug. 7-13).

Measures of serious illness finally head downward

The prolonged rise in ED visits and new admissions over the last 5 months, which continued even through late spring when cases were declining, seems to have peaked, CDC data suggest.

That upward trend, driven largely by continued increases among younger children, peaked in late July, when 6.7% of all ED visits for children aged 0-11 years involved diagnosed COVID-19. The corresponding peaks for older children occurred around the same time but were only about half as high: 3.4% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 3.6% for those aged 16-17, the CDC reported.

The data for new admissions present a similar scenario: an increase starting in mid-April that continued unabated into late July despite the decline in new cases. By the time admissions among children aged 0-17 years peaked at 0.46 per 100,000 population in late July, they had reached the same level seen during the Delta surge. By Aug. 7, the rate of new hospitalizations was down to 0.42 per 100,000, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The vaccine is ready for all students, but …

As children all over the country start or get ready to start a new school year, the only large-scale student vaccine mandate belongs to the District of Columbia. California has a mandate pending, but it will not go into effect until after July 1, 2023. There are, however, 20 states that have banned vaccine mandates for students, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Nonmandated vaccination of the youngest children against COVID-19 continues to be slow. In the approximately 7 weeks (June 19 to Aug. 9) since the vaccine was approved for use in children younger than 5 years, just 4.4% of that age group has received at least one dose and 0.7% are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 5-11 years, who have been vaccine-eligible since early November of last year, 37.6% have received at least one dose and 30.2% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

New child cases of COVID-19 made at least a temporary transition from slow increase to decrease, and emergency department visits and new admissions seem to be following a downward trend.