User login

Long COVID symptoms reported by 6% of pediatric patients

The prevalence of long COVID in children has been unclear, and is complicated by the lack of a consistent definition, said Anna Funk, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Calgary (Alba.), during her online presentation of the findings at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

In the several small studies conducted to date, rates range from 0% to 67% 2-4 months after infection, Dr. Funk reported.

To examine prevalence, she and her colleagues, as part of the Pediatric Emergency Research Network (PERN) global research consortium, assessed more than 10,500 children who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 when they presented to the ED at 1 of 41 study sites in 10 countries – Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the United States, plus three countries in Latin America and three in Western Europe – from March 2020 to June 15, 2021.

PERN researchers are following up with the more than 3,100 children who tested positive 14, 30, and 90 days after testing, tracking respiratory, neurologic, and psychobehavioral sequelae.

Dr. Funk presented data on the 1,884 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before Jan. 20, 2021, and who had completed 90-day follow-up; 447 of those children were hospitalized and 1,437 were not.

Symptoms were reported more often by children admitted to the hospital than not admitted (9.8% vs. 4.6%). Common persistent symptoms were respiratory in 2% of cases, systemic (such as fatigue and fever) in 2%, neurologic (such as headache, seizures, and continued loss of taste or smell) in 1%, and psychological (such as new-onset depression and anxiety) in 1%.

“This study provides the first good epidemiological data on persistent symptoms among SARS-CoV-2–infected children, regardless of severity,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease clinician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, who was not involved in the study.

And the findings show that, although severe COVID and chronic symptoms are less common in children than in adults, they are “not nonexistent and need to be taken seriously,” he said in an interview.

After adjustment for country of enrollment, children aged 10-17 years were more likely to experience persistent symptoms than children younger than 1 year (odds ratio, 2.4; P = .002).

Hospitalized children were more than twice as likely to experience persistent symptoms as nonhospitalized children (OR, 2.5; P < .001). And children who presented to the ED with at least seven symptoms were four times more likely to have long-term symptoms than those who presented with fewer symptoms (OR, 4.02; P = .01).

‘Some reassurance’

“Given that COVID is new and is known to have acute cardiac and neurologic effects, particularly in children with [multisystem inflammatory syndrome], there were initially concerns about persistent cardiovascular and neurologic effects in any infected child,” Dr. Messacar explained. “These data provide some reassurance that this is uncommon among children with mild or moderate infections who are not hospitalized.”

But “the risk is not zero,” he added. “Getting children vaccinated when it is available to them and taking precautions to prevent unvaccinated children getting COVID is the best way to reduce the risk of severe disease or persistent symptoms.”

The study was limited by its lack of data on variants, reliance on self-reported symptoms, and a population drawn solely from EDs, Dr. Funk acknowledged.

No external funding source was noted. Dr. Messacar and Dr. Funk disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The prevalence of long COVID in children has been unclear, and is complicated by the lack of a consistent definition, said Anna Funk, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Calgary (Alba.), during her online presentation of the findings at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

In the several small studies conducted to date, rates range from 0% to 67% 2-4 months after infection, Dr. Funk reported.

To examine prevalence, she and her colleagues, as part of the Pediatric Emergency Research Network (PERN) global research consortium, assessed more than 10,500 children who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 when they presented to the ED at 1 of 41 study sites in 10 countries – Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the United States, plus three countries in Latin America and three in Western Europe – from March 2020 to June 15, 2021.

PERN researchers are following up with the more than 3,100 children who tested positive 14, 30, and 90 days after testing, tracking respiratory, neurologic, and psychobehavioral sequelae.

Dr. Funk presented data on the 1,884 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before Jan. 20, 2021, and who had completed 90-day follow-up; 447 of those children were hospitalized and 1,437 were not.

Symptoms were reported more often by children admitted to the hospital than not admitted (9.8% vs. 4.6%). Common persistent symptoms were respiratory in 2% of cases, systemic (such as fatigue and fever) in 2%, neurologic (such as headache, seizures, and continued loss of taste or smell) in 1%, and psychological (such as new-onset depression and anxiety) in 1%.

“This study provides the first good epidemiological data on persistent symptoms among SARS-CoV-2–infected children, regardless of severity,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease clinician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, who was not involved in the study.

And the findings show that, although severe COVID and chronic symptoms are less common in children than in adults, they are “not nonexistent and need to be taken seriously,” he said in an interview.

After adjustment for country of enrollment, children aged 10-17 years were more likely to experience persistent symptoms than children younger than 1 year (odds ratio, 2.4; P = .002).

Hospitalized children were more than twice as likely to experience persistent symptoms as nonhospitalized children (OR, 2.5; P < .001). And children who presented to the ED with at least seven symptoms were four times more likely to have long-term symptoms than those who presented with fewer symptoms (OR, 4.02; P = .01).

‘Some reassurance’

“Given that COVID is new and is known to have acute cardiac and neurologic effects, particularly in children with [multisystem inflammatory syndrome], there were initially concerns about persistent cardiovascular and neurologic effects in any infected child,” Dr. Messacar explained. “These data provide some reassurance that this is uncommon among children with mild or moderate infections who are not hospitalized.”

But “the risk is not zero,” he added. “Getting children vaccinated when it is available to them and taking precautions to prevent unvaccinated children getting COVID is the best way to reduce the risk of severe disease or persistent symptoms.”

The study was limited by its lack of data on variants, reliance on self-reported symptoms, and a population drawn solely from EDs, Dr. Funk acknowledged.

No external funding source was noted. Dr. Messacar and Dr. Funk disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The prevalence of long COVID in children has been unclear, and is complicated by the lack of a consistent definition, said Anna Funk, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Calgary (Alba.), during her online presentation of the findings at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases.

In the several small studies conducted to date, rates range from 0% to 67% 2-4 months after infection, Dr. Funk reported.

To examine prevalence, she and her colleagues, as part of the Pediatric Emergency Research Network (PERN) global research consortium, assessed more than 10,500 children who were screened for SARS-CoV-2 when they presented to the ED at 1 of 41 study sites in 10 countries – Australia, Canada, Indonesia, the United States, plus three countries in Latin America and three in Western Europe – from March 2020 to June 15, 2021.

PERN researchers are following up with the more than 3,100 children who tested positive 14, 30, and 90 days after testing, tracking respiratory, neurologic, and psychobehavioral sequelae.

Dr. Funk presented data on the 1,884 children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 before Jan. 20, 2021, and who had completed 90-day follow-up; 447 of those children were hospitalized and 1,437 were not.

Symptoms were reported more often by children admitted to the hospital than not admitted (9.8% vs. 4.6%). Common persistent symptoms were respiratory in 2% of cases, systemic (such as fatigue and fever) in 2%, neurologic (such as headache, seizures, and continued loss of taste or smell) in 1%, and psychological (such as new-onset depression and anxiety) in 1%.

“This study provides the first good epidemiological data on persistent symptoms among SARS-CoV-2–infected children, regardless of severity,” said Kevin Messacar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease clinician and researcher at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora, who was not involved in the study.

And the findings show that, although severe COVID and chronic symptoms are less common in children than in adults, they are “not nonexistent and need to be taken seriously,” he said in an interview.

After adjustment for country of enrollment, children aged 10-17 years were more likely to experience persistent symptoms than children younger than 1 year (odds ratio, 2.4; P = .002).

Hospitalized children were more than twice as likely to experience persistent symptoms as nonhospitalized children (OR, 2.5; P < .001). And children who presented to the ED with at least seven symptoms were four times more likely to have long-term symptoms than those who presented with fewer symptoms (OR, 4.02; P = .01).

‘Some reassurance’

“Given that COVID is new and is known to have acute cardiac and neurologic effects, particularly in children with [multisystem inflammatory syndrome], there were initially concerns about persistent cardiovascular and neurologic effects in any infected child,” Dr. Messacar explained. “These data provide some reassurance that this is uncommon among children with mild or moderate infections who are not hospitalized.”

But “the risk is not zero,” he added. “Getting children vaccinated when it is available to them and taking precautions to prevent unvaccinated children getting COVID is the best way to reduce the risk of severe disease or persistent symptoms.”

The study was limited by its lack of data on variants, reliance on self-reported symptoms, and a population drawn solely from EDs, Dr. Funk acknowledged.

No external funding source was noted. Dr. Messacar and Dr. Funk disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New agents for youth-onset type 2 diabetes ‘finally in sight’

There are limited treatment options for children and youth with type 2 diabetes, but a few novel therapies beyond metformin are on the horizon, experts said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth only emerged as a well-recognized pediatric medical problem in the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century,” session chair Kenneth C. Copeland, MD, said in an interview.

“Fortunately, a number of clinical trials of antidiabetic pharmacologic agents in diabetic youth have now been completed, demonstrating both safety and efficacy, and at long last, a ... variety of agents are finally in sight,” he noted.

Type 2 diabetes in youth is profoundly different from type 2 diabetes in adults, added Dr. Copeland, pediatrics professor emeritus, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. In youth, its course is typically aggressive and refractive to treatment.

Concerted efforts at lifestyle intervention are important but insufficient, and a response to metformin, even when initiated at diagnosis, is often short lived, he added.

Because of the rapid glycemic deterioration that is typical of type 2 diabetes in youth and leads to the full array of diabetic complications, early aggressive pharmacologic treatment is indicated.

“We all look forward to this next decade ushering in new treatment options, spanning the spectrum from obesity prevention to complex pharmacologic intervention,” Dr. Copeland summarized.

Increasing prevalence of T2D in youth, limited therapies

Rates of type 2 diabetes in youth continue to increase, especially among non-White groups, and most of these individuals have less than optimal diabetes control, Elvira Isganaitis, MD, MPH, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Joslin Diabetes Center and assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told the meeting.

Although the Food and Drug Administration has approved more than 25 drugs to treat type 2 diabetes in adults, “unfortunately,” metformin is the only oral medication approved to treat the disease in a pediatric population, “and a majority of youth either do not respond to it or do not tolerate it,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Copeland observed that “the TODAY study demonstrated conclusively that, despite an often dramatic initial improvement in glycemic control upon initiation of pharmacologic and lifestyle intervention, this initial response was followed by a rapid deterioration of beta-cell function and glycemic failure, indicating that additional pharmacologic agents were sorely needed for this population.”

The RISE study also showed that, compared with adults, youth had more rapid beta-cell deterioration despite treatment.

Until the June 2019 FDA approval of the injectable glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Victoza, Novo Nordisk) for children 10 years or older, “except for insulin, metformin was the only antidiabetic medication available for use in youth, severely limiting treatment options,” he added.

Liraglutide ‘a huge breakthrough,’ other options on the horizon

The FDA approval of liraglutide was “a huge breakthrough” as the first noninsulin drug for pediatric type 2 diabetes since metformin was approved for pediatric use in 2000, Dr. Isganaitis said.

The ELLIPSE study, on which the approval was based, showed liraglutide was effective at lowering hemoglobin A1c and was generally well tolerated, although it was associated with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms.

In December 2020, the FDA also approved liraglutide (Saxenda) for the treatment of obesity in youth age 12 and older (at a dose of 3 mg as opposed to the 1.8-mg dose of liraglutide [Victoza]), “which is wonderful news considering that the majority of pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes also have obesity,” Dr. Isganaitis added.

“The results of studies of liraglutide on glycemia in diabetic youth are impressive, with both an additional benefit of weight loss and without unacceptable identified risks or side effects,” Dr. Copeland concurred.

Waiting in the wings

Dr. Isganaitis reported that a few phase 3 clinical trials of other therapies for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes are in the wings.

The 24-week phase 3 T2GO clinical trial of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (AstraZeneca) versus placebo in 72 patients with type 2 diabetes aged 10-24 years was completed in April 2020, and the data are being analyzed.

An AstraZeneca-sponsored phase 3 trial of the safety and efficacy of a weekly injection of the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (n = 82) has also been completed and data are being analyzed.

A Takeda-sponsored phase 3 pediatric study of the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitor alogliptin in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (n = 150) is estimated to be completed by February 2022.

And the phase 3 DINAMO trial, sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, which is evaluating the efficacy and safety of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (10 mg/25 mg) versus the DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin (5 mg) versus placebo over 26 weeks in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (estimated 186 participants), is expected to be completed in May 2023.

“I hope that these medications will demonstrate efficacy and allow pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes to have more treatment options,” Dr. Isganaitis concluded.

Type 2 diabetes more aggressive than type 1 diabetes in kids

According to Dr. Isganaitis, “there is a widely held misconception among the general public and even among some physicians that type 2 diabetes is somehow less worrisome or ‘milder’ than a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.”

However, the risk of complications and severe morbidity is higher with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes versus type 1 diabetes in a child, so “this condition needs to be managed intensively with a multidisciplinary team including pediatric endocrinology, nutrition [support], diabetes educators, and mental health support,” she emphasized.

Many people also believe that “type 2 diabetes in kids is a ‘lifestyle disease,’ ” she continued, “but in fact, there is a strong role for genetics.”

The ADA Presidents’ Select Abstract “paints a picture of youth-onset type 2 diabetes as a disease intermediate in extremity between monogenic diabetes [caused by mutations in a single gene] and type 2 diabetes [caused by multiple genes and lifestyle factors such as obesity], in which genetic variants in both insulin secretion and insulin response pathways are implicated.”

Along the same lines, Dr. Isganaitis presented an oral abstract at the meeting that showed that, among youth with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, those whose mothers had diabetes had faster disease progression and earlier onset of diabetes complications.

Dr. Isganaitis has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Copeland has reported serving on data monitoring committees for Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk, and on an advisory committee for a research study for Daiichi Sankyo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There are limited treatment options for children and youth with type 2 diabetes, but a few novel therapies beyond metformin are on the horizon, experts said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth only emerged as a well-recognized pediatric medical problem in the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century,” session chair Kenneth C. Copeland, MD, said in an interview.

“Fortunately, a number of clinical trials of antidiabetic pharmacologic agents in diabetic youth have now been completed, demonstrating both safety and efficacy, and at long last, a ... variety of agents are finally in sight,” he noted.

Type 2 diabetes in youth is profoundly different from type 2 diabetes in adults, added Dr. Copeland, pediatrics professor emeritus, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. In youth, its course is typically aggressive and refractive to treatment.

Concerted efforts at lifestyle intervention are important but insufficient, and a response to metformin, even when initiated at diagnosis, is often short lived, he added.

Because of the rapid glycemic deterioration that is typical of type 2 diabetes in youth and leads to the full array of diabetic complications, early aggressive pharmacologic treatment is indicated.

“We all look forward to this next decade ushering in new treatment options, spanning the spectrum from obesity prevention to complex pharmacologic intervention,” Dr. Copeland summarized.

Increasing prevalence of T2D in youth, limited therapies

Rates of type 2 diabetes in youth continue to increase, especially among non-White groups, and most of these individuals have less than optimal diabetes control, Elvira Isganaitis, MD, MPH, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Joslin Diabetes Center and assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told the meeting.

Although the Food and Drug Administration has approved more than 25 drugs to treat type 2 diabetes in adults, “unfortunately,” metformin is the only oral medication approved to treat the disease in a pediatric population, “and a majority of youth either do not respond to it or do not tolerate it,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Copeland observed that “the TODAY study demonstrated conclusively that, despite an often dramatic initial improvement in glycemic control upon initiation of pharmacologic and lifestyle intervention, this initial response was followed by a rapid deterioration of beta-cell function and glycemic failure, indicating that additional pharmacologic agents were sorely needed for this population.”

The RISE study also showed that, compared with adults, youth had more rapid beta-cell deterioration despite treatment.

Until the June 2019 FDA approval of the injectable glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Victoza, Novo Nordisk) for children 10 years or older, “except for insulin, metformin was the only antidiabetic medication available for use in youth, severely limiting treatment options,” he added.

Liraglutide ‘a huge breakthrough,’ other options on the horizon

The FDA approval of liraglutide was “a huge breakthrough” as the first noninsulin drug for pediatric type 2 diabetes since metformin was approved for pediatric use in 2000, Dr. Isganaitis said.

The ELLIPSE study, on which the approval was based, showed liraglutide was effective at lowering hemoglobin A1c and was generally well tolerated, although it was associated with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms.

In December 2020, the FDA also approved liraglutide (Saxenda) for the treatment of obesity in youth age 12 and older (at a dose of 3 mg as opposed to the 1.8-mg dose of liraglutide [Victoza]), “which is wonderful news considering that the majority of pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes also have obesity,” Dr. Isganaitis added.

“The results of studies of liraglutide on glycemia in diabetic youth are impressive, with both an additional benefit of weight loss and without unacceptable identified risks or side effects,” Dr. Copeland concurred.

Waiting in the wings

Dr. Isganaitis reported that a few phase 3 clinical trials of other therapies for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes are in the wings.

The 24-week phase 3 T2GO clinical trial of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (AstraZeneca) versus placebo in 72 patients with type 2 diabetes aged 10-24 years was completed in April 2020, and the data are being analyzed.

An AstraZeneca-sponsored phase 3 trial of the safety and efficacy of a weekly injection of the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (n = 82) has also been completed and data are being analyzed.

A Takeda-sponsored phase 3 pediatric study of the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitor alogliptin in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (n = 150) is estimated to be completed by February 2022.

And the phase 3 DINAMO trial, sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, which is evaluating the efficacy and safety of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (10 mg/25 mg) versus the DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin (5 mg) versus placebo over 26 weeks in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (estimated 186 participants), is expected to be completed in May 2023.

“I hope that these medications will demonstrate efficacy and allow pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes to have more treatment options,” Dr. Isganaitis concluded.

Type 2 diabetes more aggressive than type 1 diabetes in kids

According to Dr. Isganaitis, “there is a widely held misconception among the general public and even among some physicians that type 2 diabetes is somehow less worrisome or ‘milder’ than a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.”

However, the risk of complications and severe morbidity is higher with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes versus type 1 diabetes in a child, so “this condition needs to be managed intensively with a multidisciplinary team including pediatric endocrinology, nutrition [support], diabetes educators, and mental health support,” she emphasized.

Many people also believe that “type 2 diabetes in kids is a ‘lifestyle disease,’ ” she continued, “but in fact, there is a strong role for genetics.”

The ADA Presidents’ Select Abstract “paints a picture of youth-onset type 2 diabetes as a disease intermediate in extremity between monogenic diabetes [caused by mutations in a single gene] and type 2 diabetes [caused by multiple genes and lifestyle factors such as obesity], in which genetic variants in both insulin secretion and insulin response pathways are implicated.”

Along the same lines, Dr. Isganaitis presented an oral abstract at the meeting that showed that, among youth with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, those whose mothers had diabetes had faster disease progression and earlier onset of diabetes complications.

Dr. Isganaitis has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Copeland has reported serving on data monitoring committees for Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk, and on an advisory committee for a research study for Daiichi Sankyo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There are limited treatment options for children and youth with type 2 diabetes, but a few novel therapies beyond metformin are on the horizon, experts said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Type 2 diabetes in youth only emerged as a well-recognized pediatric medical problem in the 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century,” session chair Kenneth C. Copeland, MD, said in an interview.

“Fortunately, a number of clinical trials of antidiabetic pharmacologic agents in diabetic youth have now been completed, demonstrating both safety and efficacy, and at long last, a ... variety of agents are finally in sight,” he noted.

Type 2 diabetes in youth is profoundly different from type 2 diabetes in adults, added Dr. Copeland, pediatrics professor emeritus, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. In youth, its course is typically aggressive and refractive to treatment.

Concerted efforts at lifestyle intervention are important but insufficient, and a response to metformin, even when initiated at diagnosis, is often short lived, he added.

Because of the rapid glycemic deterioration that is typical of type 2 diabetes in youth and leads to the full array of diabetic complications, early aggressive pharmacologic treatment is indicated.

“We all look forward to this next decade ushering in new treatment options, spanning the spectrum from obesity prevention to complex pharmacologic intervention,” Dr. Copeland summarized.

Increasing prevalence of T2D in youth, limited therapies

Rates of type 2 diabetes in youth continue to increase, especially among non-White groups, and most of these individuals have less than optimal diabetes control, Elvira Isganaitis, MD, MPH, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Joslin Diabetes Center and assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told the meeting.

Although the Food and Drug Administration has approved more than 25 drugs to treat type 2 diabetes in adults, “unfortunately,” metformin is the only oral medication approved to treat the disease in a pediatric population, “and a majority of youth either do not respond to it or do not tolerate it,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Copeland observed that “the TODAY study demonstrated conclusively that, despite an often dramatic initial improvement in glycemic control upon initiation of pharmacologic and lifestyle intervention, this initial response was followed by a rapid deterioration of beta-cell function and glycemic failure, indicating that additional pharmacologic agents were sorely needed for this population.”

The RISE study also showed that, compared with adults, youth had more rapid beta-cell deterioration despite treatment.

Until the June 2019 FDA approval of the injectable glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist liraglutide (Victoza, Novo Nordisk) for children 10 years or older, “except for insulin, metformin was the only antidiabetic medication available for use in youth, severely limiting treatment options,” he added.

Liraglutide ‘a huge breakthrough,’ other options on the horizon

The FDA approval of liraglutide was “a huge breakthrough” as the first noninsulin drug for pediatric type 2 diabetes since metformin was approved for pediatric use in 2000, Dr. Isganaitis said.

The ELLIPSE study, on which the approval was based, showed liraglutide was effective at lowering hemoglobin A1c and was generally well tolerated, although it was associated with a higher incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms.

In December 2020, the FDA also approved liraglutide (Saxenda) for the treatment of obesity in youth age 12 and older (at a dose of 3 mg as opposed to the 1.8-mg dose of liraglutide [Victoza]), “which is wonderful news considering that the majority of pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes also have obesity,” Dr. Isganaitis added.

“The results of studies of liraglutide on glycemia in diabetic youth are impressive, with both an additional benefit of weight loss and without unacceptable identified risks or side effects,” Dr. Copeland concurred.

Waiting in the wings

Dr. Isganaitis reported that a few phase 3 clinical trials of other therapies for pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes are in the wings.

The 24-week phase 3 T2GO clinical trial of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin (AstraZeneca) versus placebo in 72 patients with type 2 diabetes aged 10-24 years was completed in April 2020, and the data are being analyzed.

An AstraZeneca-sponsored phase 3 trial of the safety and efficacy of a weekly injection of the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (n = 82) has also been completed and data are being analyzed.

A Takeda-sponsored phase 3 pediatric study of the dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitor alogliptin in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (n = 150) is estimated to be completed by February 2022.

And the phase 3 DINAMO trial, sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, which is evaluating the efficacy and safety of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin (10 mg/25 mg) versus the DPP-4 inhibitor linagliptin (5 mg) versus placebo over 26 weeks in 10- to 17-year-olds with type 2 diabetes (estimated 186 participants), is expected to be completed in May 2023.

“I hope that these medications will demonstrate efficacy and allow pediatric patients with type 2 diabetes to have more treatment options,” Dr. Isganaitis concluded.

Type 2 diabetes more aggressive than type 1 diabetes in kids

According to Dr. Isganaitis, “there is a widely held misconception among the general public and even among some physicians that type 2 diabetes is somehow less worrisome or ‘milder’ than a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes.”

However, the risk of complications and severe morbidity is higher with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes versus type 1 diabetes in a child, so “this condition needs to be managed intensively with a multidisciplinary team including pediatric endocrinology, nutrition [support], diabetes educators, and mental health support,” she emphasized.

Many people also believe that “type 2 diabetes in kids is a ‘lifestyle disease,’ ” she continued, “but in fact, there is a strong role for genetics.”

The ADA Presidents’ Select Abstract “paints a picture of youth-onset type 2 diabetes as a disease intermediate in extremity between monogenic diabetes [caused by mutations in a single gene] and type 2 diabetes [caused by multiple genes and lifestyle factors such as obesity], in which genetic variants in both insulin secretion and insulin response pathways are implicated.”

Along the same lines, Dr. Isganaitis presented an oral abstract at the meeting that showed that, among youth with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, those whose mothers had diabetes had faster disease progression and earlier onset of diabetes complications.

Dr. Isganaitis has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Copeland has reported serving on data monitoring committees for Boehringer Ingelheim and Novo Nordisk, and on an advisory committee for a research study for Daiichi Sankyo.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rising rates of T1D in children: Is COVID to blame?

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything about life as we know it, with widespread shutdowns across the globe. The U.S. health care system quickly adapted, pivoting to telehealth visits when able and proactively managing outpatient conditions to prevent overwhelming hospital resources and utilization. Meanwhile, at my practice, the typical rate of about one new-onset pediatric type 1 diabetes (T1D) case per week increased to about two per week.

However, the new diabetes cases continued to accumulate, and I saw more patients being diagnosed who did not have a known family history of autoimmunity. I began to ask friends at other centers whether they were noticing the same trend.

One colleague documented a 36% increase in her large center compared with the previous year. Another noted a 40% rise at his children’s hospital. We observed that there was often a respiratory illness reported several weeks before presenting with T1D. Sometimes the child was known to be COVID-positive. Sometimes the child had not been tested. Sometimes we suspected that COVID had been a preceding illness and then found negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies – but we were not certain whether the result was meaningful given the time lapsed since infection.

Soon, reports emerged of large increases in severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state at initial presentation, a trend reported in other countries.

Is COVID-19 a trigger for T1D?

There is known precedent for increased risk for T1D after viral infections in patients who are already genetically susceptible. Mechanisms of immune-mediated islet cell failure would make sense following SARS-CoV-2 infection; direct islet toxicity was noted with SARS-CoV-1 and has been suspected with SARS-CoV-2 but not proven. Some have suggested that hypercoagulability with COVID-19 may lead to ischemic damage to the pancreas.

With multiple potential pathways for islet damage, increases in insulin-dependent diabetes would logically follow. Still, whether this is the case remains unclear. There is not yet definitive evidence that there is uptake of SARS-CoV-2 via receptors in the pancreatic beta cells.

Our current understanding of T1D pathogenesis is that susceptible individuals develop autoimmunity in response to an environmental trigger, with beta-cell failure developing over months to years. Perhaps vulnerable patients with genetic risk for pancreatic autoimmunity were stressed by SARS-CoV-2 infection and were diagnosed earlier than they might have been, showing some lead-time bias. Adult patients with COVID-19 demonstrated hyperglycemia that has been reversible in some cases, like the stress hyperglycemia seen with other infections and surgery in response to proinflammatory states.

The true question seems to be whether there is a unique type of diabetes related to direct viral toxicity. Do newly diagnosed patients have measurable traditional antibodies, like anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase or anti-islet cell antibodies? Is there proof of preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection? In the new cases that I thought were unusual at first glance, I found typical pancreatic autoimmunity and negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The small cohorts reported thus far have had similar findings.

A stronger case can be made for the risk of developing diabetes (types 1 and 2) with rapid weight gain. Another marked pattern that pediatric endocrinologists have observed has been increased weight gain in children with closed schools, decreased activity, and more social isolation. I have seen weight change as great as 100 lb in a teen over the past year; 30- to 50-lb weight increases over the course of the pandemic have been common. Considering the “accelerator hypothesis” of faster onset of type 2 diabetes with rapid weight gain, implications for hastening of T1D with weight gain have also been considered. The full impact of these dramatic weight changes will take time to understand.

The true story may not emerge for years

Anecdotes and theoretical concerns may give us pause, but they are far from scientific truth. Efforts are underway to explore this perceived trend with international registries, including the CoviDIAB Registry as well as T1D Exchange. The true story may not emerge until years have passed to see the cumulative fallout of COVID-19. Regardless, these troubling observations should be considered as pandemic safeguards continue to loosen.

While pediatric mortality from COVID-19 has been relatively low (though sadly not zero), some have placed too little focus on possible morbidity. Long-term effects like long COVID and neuropsychiatric sequelae are becoming evident in all populations, including children. If a lifelong illness like diabetes can be directly linked to COVID-19, protecting children from infection with measures like masks becomes all the more crucial until vaccines are more readily available. Despite our rapid progress with understanding COVID-19 disease, there is still much left to learn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything about life as we know it, with widespread shutdowns across the globe. The U.S. health care system quickly adapted, pivoting to telehealth visits when able and proactively managing outpatient conditions to prevent overwhelming hospital resources and utilization. Meanwhile, at my practice, the typical rate of about one new-onset pediatric type 1 diabetes (T1D) case per week increased to about two per week.

However, the new diabetes cases continued to accumulate, and I saw more patients being diagnosed who did not have a known family history of autoimmunity. I began to ask friends at other centers whether they were noticing the same trend.

One colleague documented a 36% increase in her large center compared with the previous year. Another noted a 40% rise at his children’s hospital. We observed that there was often a respiratory illness reported several weeks before presenting with T1D. Sometimes the child was known to be COVID-positive. Sometimes the child had not been tested. Sometimes we suspected that COVID had been a preceding illness and then found negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies – but we were not certain whether the result was meaningful given the time lapsed since infection.

Soon, reports emerged of large increases in severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state at initial presentation, a trend reported in other countries.

Is COVID-19 a trigger for T1D?

There is known precedent for increased risk for T1D after viral infections in patients who are already genetically susceptible. Mechanisms of immune-mediated islet cell failure would make sense following SARS-CoV-2 infection; direct islet toxicity was noted with SARS-CoV-1 and has been suspected with SARS-CoV-2 but not proven. Some have suggested that hypercoagulability with COVID-19 may lead to ischemic damage to the pancreas.

With multiple potential pathways for islet damage, increases in insulin-dependent diabetes would logically follow. Still, whether this is the case remains unclear. There is not yet definitive evidence that there is uptake of SARS-CoV-2 via receptors in the pancreatic beta cells.

Our current understanding of T1D pathogenesis is that susceptible individuals develop autoimmunity in response to an environmental trigger, with beta-cell failure developing over months to years. Perhaps vulnerable patients with genetic risk for pancreatic autoimmunity were stressed by SARS-CoV-2 infection and were diagnosed earlier than they might have been, showing some lead-time bias. Adult patients with COVID-19 demonstrated hyperglycemia that has been reversible in some cases, like the stress hyperglycemia seen with other infections and surgery in response to proinflammatory states.

The true question seems to be whether there is a unique type of diabetes related to direct viral toxicity. Do newly diagnosed patients have measurable traditional antibodies, like anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase or anti-islet cell antibodies? Is there proof of preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection? In the new cases that I thought were unusual at first glance, I found typical pancreatic autoimmunity and negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The small cohorts reported thus far have had similar findings.

A stronger case can be made for the risk of developing diabetes (types 1 and 2) with rapid weight gain. Another marked pattern that pediatric endocrinologists have observed has been increased weight gain in children with closed schools, decreased activity, and more social isolation. I have seen weight change as great as 100 lb in a teen over the past year; 30- to 50-lb weight increases over the course of the pandemic have been common. Considering the “accelerator hypothesis” of faster onset of type 2 diabetes with rapid weight gain, implications for hastening of T1D with weight gain have also been considered. The full impact of these dramatic weight changes will take time to understand.

The true story may not emerge for years

Anecdotes and theoretical concerns may give us pause, but they are far from scientific truth. Efforts are underway to explore this perceived trend with international registries, including the CoviDIAB Registry as well as T1D Exchange. The true story may not emerge until years have passed to see the cumulative fallout of COVID-19. Regardless, these troubling observations should be considered as pandemic safeguards continue to loosen.

While pediatric mortality from COVID-19 has been relatively low (though sadly not zero), some have placed too little focus on possible morbidity. Long-term effects like long COVID and neuropsychiatric sequelae are becoming evident in all populations, including children. If a lifelong illness like diabetes can be directly linked to COVID-19, protecting children from infection with measures like masks becomes all the more crucial until vaccines are more readily available. Despite our rapid progress with understanding COVID-19 disease, there is still much left to learn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything about life as we know it, with widespread shutdowns across the globe. The U.S. health care system quickly adapted, pivoting to telehealth visits when able and proactively managing outpatient conditions to prevent overwhelming hospital resources and utilization. Meanwhile, at my practice, the typical rate of about one new-onset pediatric type 1 diabetes (T1D) case per week increased to about two per week.

However, the new diabetes cases continued to accumulate, and I saw more patients being diagnosed who did not have a known family history of autoimmunity. I began to ask friends at other centers whether they were noticing the same trend.

One colleague documented a 36% increase in her large center compared with the previous year. Another noted a 40% rise at his children’s hospital. We observed that there was often a respiratory illness reported several weeks before presenting with T1D. Sometimes the child was known to be COVID-positive. Sometimes the child had not been tested. Sometimes we suspected that COVID had been a preceding illness and then found negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies – but we were not certain whether the result was meaningful given the time lapsed since infection.

Soon, reports emerged of large increases in severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state at initial presentation, a trend reported in other countries.

Is COVID-19 a trigger for T1D?

There is known precedent for increased risk for T1D after viral infections in patients who are already genetically susceptible. Mechanisms of immune-mediated islet cell failure would make sense following SARS-CoV-2 infection; direct islet toxicity was noted with SARS-CoV-1 and has been suspected with SARS-CoV-2 but not proven. Some have suggested that hypercoagulability with COVID-19 may lead to ischemic damage to the pancreas.

With multiple potential pathways for islet damage, increases in insulin-dependent diabetes would logically follow. Still, whether this is the case remains unclear. There is not yet definitive evidence that there is uptake of SARS-CoV-2 via receptors in the pancreatic beta cells.

Our current understanding of T1D pathogenesis is that susceptible individuals develop autoimmunity in response to an environmental trigger, with beta-cell failure developing over months to years. Perhaps vulnerable patients with genetic risk for pancreatic autoimmunity were stressed by SARS-CoV-2 infection and were diagnosed earlier than they might have been, showing some lead-time bias. Adult patients with COVID-19 demonstrated hyperglycemia that has been reversible in some cases, like the stress hyperglycemia seen with other infections and surgery in response to proinflammatory states.

The true question seems to be whether there is a unique type of diabetes related to direct viral toxicity. Do newly diagnosed patients have measurable traditional antibodies, like anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase or anti-islet cell antibodies? Is there proof of preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection? In the new cases that I thought were unusual at first glance, I found typical pancreatic autoimmunity and negative SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The small cohorts reported thus far have had similar findings.

A stronger case can be made for the risk of developing diabetes (types 1 and 2) with rapid weight gain. Another marked pattern that pediatric endocrinologists have observed has been increased weight gain in children with closed schools, decreased activity, and more social isolation. I have seen weight change as great as 100 lb in a teen over the past year; 30- to 50-lb weight increases over the course of the pandemic have been common. Considering the “accelerator hypothesis” of faster onset of type 2 diabetes with rapid weight gain, implications for hastening of T1D with weight gain have also been considered. The full impact of these dramatic weight changes will take time to understand.

The true story may not emerge for years

Anecdotes and theoretical concerns may give us pause, but they are far from scientific truth. Efforts are underway to explore this perceived trend with international registries, including the CoviDIAB Registry as well as T1D Exchange. The true story may not emerge until years have passed to see the cumulative fallout of COVID-19. Regardless, these troubling observations should be considered as pandemic safeguards continue to loosen.

While pediatric mortality from COVID-19 has been relatively low (though sadly not zero), some have placed too little focus on possible morbidity. Long-term effects like long COVID and neuropsychiatric sequelae are becoming evident in all populations, including children. If a lifelong illness like diabetes can be directly linked to COVID-19, protecting children from infection with measures like masks becomes all the more crucial until vaccines are more readily available. Despite our rapid progress with understanding COVID-19 disease, there is still much left to learn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: New vaccinations drop as the case count rises

With only a quarter of all children aged 12-15 years fully vaccinated against COVID-19, first vaccinations continued to drop and new cases for all children rose for the second consecutive week.

Just under 25% of children aged 12-15 had completed the vaccine regimen as of July 12, and just over one-third (33.5%) had received at least one dose. Meanwhile, that age group represented 11.5% of people who initiated vaccination during the 2 weeks ending July 12, down from 12.1% a week earlier, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. The total number of new vaccinations for the week ending July 12 was just over 201,000, compared with 307,000 for the previous week.

New cases of COVID-19, however, were on the rise in children. The 19,000 new cases reported for the week ending July 8 were up from 12,000 a week earlier and 8,000 the week before that, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That report also shows that children made up 22.3% of all new cases during the week of July 2-8, compared with 16.8% the previous week, and that there were nine deaths in children that same week, the most since March. COVID-related deaths among children total 344 in the 46 jurisdictions (43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that are reporting such data by age. “It is not possible to standardize more detailed age ranges for children based on what is publicly available from the states,” the two groups noted.

Such data are available from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker, however, and they show that children aged 16-17 years, who became eligible for COVID vaccination before the younger age group, are further ahead in the process. Among the older children, almost 46% had gotten at least one dose and 37% were fully vaccinated by July 12.

With only a quarter of all children aged 12-15 years fully vaccinated against COVID-19, first vaccinations continued to drop and new cases for all children rose for the second consecutive week.

Just under 25% of children aged 12-15 had completed the vaccine regimen as of July 12, and just over one-third (33.5%) had received at least one dose. Meanwhile, that age group represented 11.5% of people who initiated vaccination during the 2 weeks ending July 12, down from 12.1% a week earlier, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. The total number of new vaccinations for the week ending July 12 was just over 201,000, compared with 307,000 for the previous week.

New cases of COVID-19, however, were on the rise in children. The 19,000 new cases reported for the week ending July 8 were up from 12,000 a week earlier and 8,000 the week before that, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That report also shows that children made up 22.3% of all new cases during the week of July 2-8, compared with 16.8% the previous week, and that there were nine deaths in children that same week, the most since March. COVID-related deaths among children total 344 in the 46 jurisdictions (43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that are reporting such data by age. “It is not possible to standardize more detailed age ranges for children based on what is publicly available from the states,” the two groups noted.

Such data are available from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker, however, and they show that children aged 16-17 years, who became eligible for COVID vaccination before the younger age group, are further ahead in the process. Among the older children, almost 46% had gotten at least one dose and 37% were fully vaccinated by July 12.

With only a quarter of all children aged 12-15 years fully vaccinated against COVID-19, first vaccinations continued to drop and new cases for all children rose for the second consecutive week.

Just under 25% of children aged 12-15 had completed the vaccine regimen as of July 12, and just over one-third (33.5%) had received at least one dose. Meanwhile, that age group represented 11.5% of people who initiated vaccination during the 2 weeks ending July 12, down from 12.1% a week earlier, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. The total number of new vaccinations for the week ending July 12 was just over 201,000, compared with 307,000 for the previous week.

New cases of COVID-19, however, were on the rise in children. The 19,000 new cases reported for the week ending July 8 were up from 12,000 a week earlier and 8,000 the week before that, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That report also shows that children made up 22.3% of all new cases during the week of July 2-8, compared with 16.8% the previous week, and that there were nine deaths in children that same week, the most since March. COVID-related deaths among children total 344 in the 46 jurisdictions (43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam) that are reporting such data by age. “It is not possible to standardize more detailed age ranges for children based on what is publicly available from the states,” the two groups noted.

Such data are available from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker, however, and they show that children aged 16-17 years, who became eligible for COVID vaccination before the younger age group, are further ahead in the process. Among the older children, almost 46% had gotten at least one dose and 37% were fully vaccinated by July 12.

Respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children

Some children are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections in the first few years of life than others. However, the factors contributing to this susceptibility are incompletely understood. The pathogenesis, development, severity, and clinical outcomes of respiratory infections are largely dependent on the resident composition of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and immune defense.1

Respiratory infections caused by bacteria and/or viruses are a leading cause of death in children in the United States and worldwide. The well-recognized, predominant causative bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu), and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). Respiratory infections caused by these pathogens result in considerable morbidity, mortality, and account for high health care costs. The clinical and laboratory group that I lead in Rochester, N.Y., has been studying acute otitis media (AOM) etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment for over 3 decades. Our research findings are likely applicable and generalizable to understanding the pathogenesis and immune response to other infectious diseases induced by pneumococcus, Hflu, and Mcat since they are also key pathogens causing sinusitis and lung infections.

Previous immunologic analysis of children with AOM by our group provided clarity in differences between infection-prone children manifest as otitis prone (OP; often referred to in our publications as stringently defined OP because of the stringent diagnostic requirement of tympanocentesis-proven etiology of infection) and non-OP children. We showed that about 90% of OP children have deficient immune responses following nasopharyngeal colonization and AOM, demonstrated by inadequate innate responses and adaptive immune responses.2 Many of these children also showed an increased propensity to viral upper respiratory infection and 30% fail to produce protective antibody responses after injection of routine pediatric vaccines.3,4

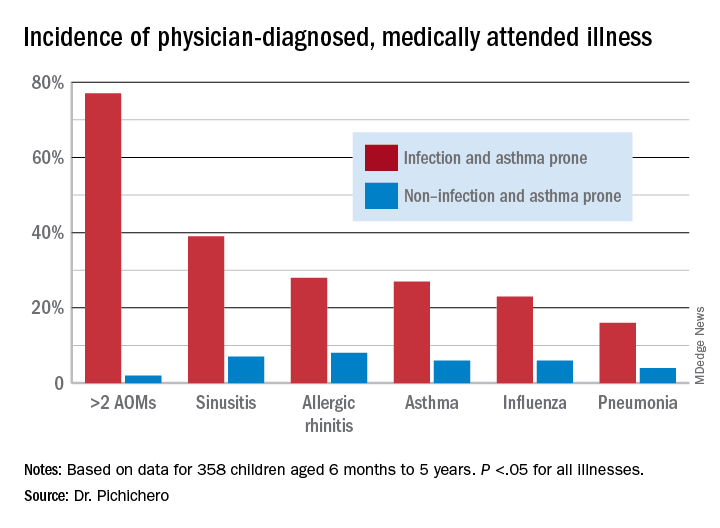

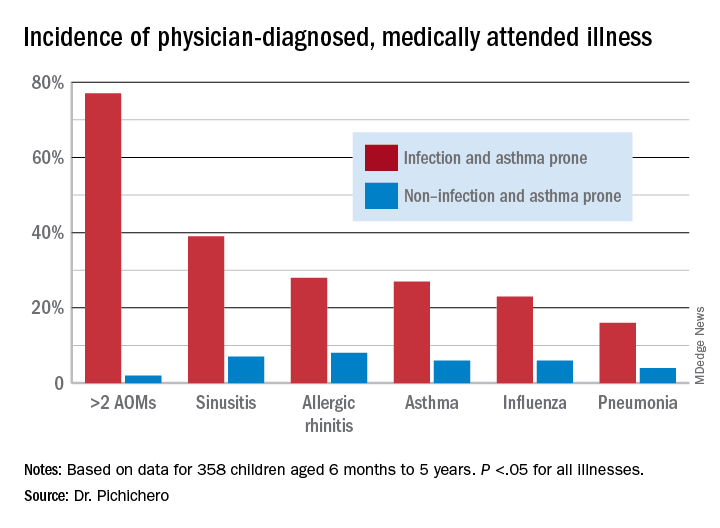

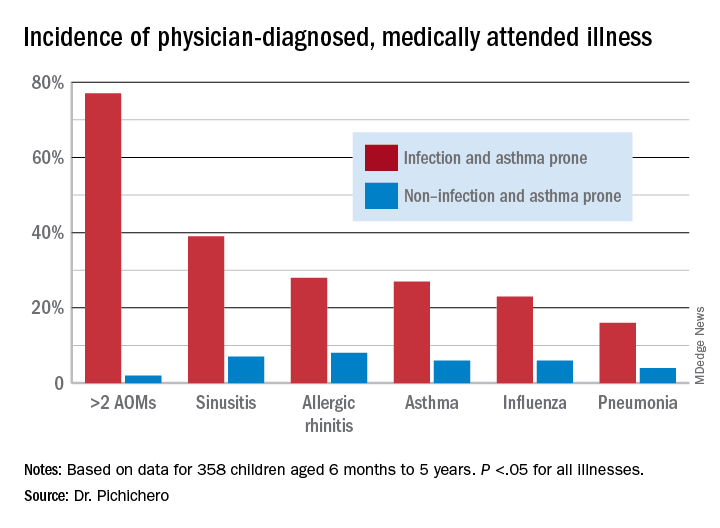

In this column, I want to share new information regarding differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children who are respiratory infection prone versus those who are non–respiratory infection prone and children with asthma versus those who do not exhibit that clinical phenotype. We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical samples collected from 358 children, aged 6 months to 5 years, from our prospectively enrolled cohort in Rochester, N.Y., to determine associations between AOM and other childhood respiratory illnesses and nasopharyngeal microbiota. In order to define subgroups of children within the cohort, we used a statistical method called unsupervised clustering analysis to see if relatively unique groups of children could be discerned. The overall cohort successfully clustered into two groups, showing marked differences in the prevalence of respiratory infections and asthma.5 We termed the two clinical phenotypes infection and asthma prone (n = 99, 28% of the children) and non–infection and asthma prone (n = 259, 72% of the children). Infection- and asthma-prone children were significantly more likely to experience recurrent AOM, influenza, sinusitis, pneumonia, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, compared with non–infection- and asthma-prone children (Figure).

The two groups did not experience significantly different rates of eczema, food allergy, skin infections, urinary tract infections, or acute gastroenteritis, suggesting a common thread involving the respiratory tract that did not cross over to the gastrointestinal, skin, or urinary tract. We found that age at first nasopharyngeal colonization with any of the three bacterial respiratory pathogens (pneumococcus, Hflu, or Mcat) was significantly associated with the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Specifically, respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children experienced colonization at a significantly earlier age than nonprone children did for all three bacteria. In an analysis of individual conditions, early Mcat colonization significantly associated with pneumonia, sinusitis, and asthma susceptibility; Hflu with pneumonia, sinusitis, influenza, and allergic rhinitis; and pneumococcus with sinusitis.

Since early colonization with the three bacterial respiratory pathogens was strongly associated with respiratory illnesses and asthma, nasopharyngeal microbiome analysis was performed on an available subset of samples. Bacterial diversity trended lower in infection- and asthma-prone children, consistent with dysbiosis in the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Nine different bacteria genera were found to be differentially abundant when comparing respiratory infection– and asthma-prone and nonprone children, pointing the way to possible interventions to make the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone child nasopharyngeal microbiome more like the nonprone child.

As I have written previously in this column, recent accumulating data have shed light on the importance of the human microbiome in modulating immune homeostasis and disease susceptibility.6 My group is working toward generating new knowledge for the long-term goal of identifying new therapeutic strategies to facilitate a protective, diverse nasopharyngeal microbiome (with appropriately tuned intranasal probiotics) to prevent respiratory pathogen colonization and/or subsequent progression to respiratory infection and asthma. Also, vaccines directed against colonization-enhancing members of the microbiome may provide a means to indirectly control respiratory pathogen nasopharyngeal colonization.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Contact him at [email protected]

References

1. Man WH et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-70.

2. Pichichero ME. J Infect. 2020;80(6):614-22.

3. Ren D et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1566-74.

4. Pichichero ME et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1163-8.

5. Chapman T et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12).

6. Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4162-5.

Some children are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections in the first few years of life than others. However, the factors contributing to this susceptibility are incompletely understood. The pathogenesis, development, severity, and clinical outcomes of respiratory infections are largely dependent on the resident composition of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and immune defense.1

Respiratory infections caused by bacteria and/or viruses are a leading cause of death in children in the United States and worldwide. The well-recognized, predominant causative bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu), and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). Respiratory infections caused by these pathogens result in considerable morbidity, mortality, and account for high health care costs. The clinical and laboratory group that I lead in Rochester, N.Y., has been studying acute otitis media (AOM) etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment for over 3 decades. Our research findings are likely applicable and generalizable to understanding the pathogenesis and immune response to other infectious diseases induced by pneumococcus, Hflu, and Mcat since they are also key pathogens causing sinusitis and lung infections.

Previous immunologic analysis of children with AOM by our group provided clarity in differences between infection-prone children manifest as otitis prone (OP; often referred to in our publications as stringently defined OP because of the stringent diagnostic requirement of tympanocentesis-proven etiology of infection) and non-OP children. We showed that about 90% of OP children have deficient immune responses following nasopharyngeal colonization and AOM, demonstrated by inadequate innate responses and adaptive immune responses.2 Many of these children also showed an increased propensity to viral upper respiratory infection and 30% fail to produce protective antibody responses after injection of routine pediatric vaccines.3,4

In this column, I want to share new information regarding differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children who are respiratory infection prone versus those who are non–respiratory infection prone and children with asthma versus those who do not exhibit that clinical phenotype. We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical samples collected from 358 children, aged 6 months to 5 years, from our prospectively enrolled cohort in Rochester, N.Y., to determine associations between AOM and other childhood respiratory illnesses and nasopharyngeal microbiota. In order to define subgroups of children within the cohort, we used a statistical method called unsupervised clustering analysis to see if relatively unique groups of children could be discerned. The overall cohort successfully clustered into two groups, showing marked differences in the prevalence of respiratory infections and asthma.5 We termed the two clinical phenotypes infection and asthma prone (n = 99, 28% of the children) and non–infection and asthma prone (n = 259, 72% of the children). Infection- and asthma-prone children were significantly more likely to experience recurrent AOM, influenza, sinusitis, pneumonia, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, compared with non–infection- and asthma-prone children (Figure).

The two groups did not experience significantly different rates of eczema, food allergy, skin infections, urinary tract infections, or acute gastroenteritis, suggesting a common thread involving the respiratory tract that did not cross over to the gastrointestinal, skin, or urinary tract. We found that age at first nasopharyngeal colonization with any of the three bacterial respiratory pathogens (pneumococcus, Hflu, or Mcat) was significantly associated with the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Specifically, respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children experienced colonization at a significantly earlier age than nonprone children did for all three bacteria. In an analysis of individual conditions, early Mcat colonization significantly associated with pneumonia, sinusitis, and asthma susceptibility; Hflu with pneumonia, sinusitis, influenza, and allergic rhinitis; and pneumococcus with sinusitis.

Since early colonization with the three bacterial respiratory pathogens was strongly associated with respiratory illnesses and asthma, nasopharyngeal microbiome analysis was performed on an available subset of samples. Bacterial diversity trended lower in infection- and asthma-prone children, consistent with dysbiosis in the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Nine different bacteria genera were found to be differentially abundant when comparing respiratory infection– and asthma-prone and nonprone children, pointing the way to possible interventions to make the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone child nasopharyngeal microbiome more like the nonprone child.

As I have written previously in this column, recent accumulating data have shed light on the importance of the human microbiome in modulating immune homeostasis and disease susceptibility.6 My group is working toward generating new knowledge for the long-term goal of identifying new therapeutic strategies to facilitate a protective, diverse nasopharyngeal microbiome (with appropriately tuned intranasal probiotics) to prevent respiratory pathogen colonization and/or subsequent progression to respiratory infection and asthma. Also, vaccines directed against colonization-enhancing members of the microbiome may provide a means to indirectly control respiratory pathogen nasopharyngeal colonization.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Contact him at [email protected]

References

1. Man WH et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-70.

2. Pichichero ME. J Infect. 2020;80(6):614-22.

3. Ren D et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1566-74.

4. Pichichero ME et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1163-8.

5. Chapman T et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12).

6. Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4162-5.

Some children are more susceptible to viral and bacterial respiratory infections in the first few years of life than others. However, the factors contributing to this susceptibility are incompletely understood. The pathogenesis, development, severity, and clinical outcomes of respiratory infections are largely dependent on the resident composition of the nasopharyngeal microbiome and immune defense.1

Respiratory infections caused by bacteria and/or viruses are a leading cause of death in children in the United States and worldwide. The well-recognized, predominant causative bacteria are Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (Hflu), and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). Respiratory infections caused by these pathogens result in considerable morbidity, mortality, and account for high health care costs. The clinical and laboratory group that I lead in Rochester, N.Y., has been studying acute otitis media (AOM) etiology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment for over 3 decades. Our research findings are likely applicable and generalizable to understanding the pathogenesis and immune response to other infectious diseases induced by pneumococcus, Hflu, and Mcat since they are also key pathogens causing sinusitis and lung infections.

Previous immunologic analysis of children with AOM by our group provided clarity in differences between infection-prone children manifest as otitis prone (OP; often referred to in our publications as stringently defined OP because of the stringent diagnostic requirement of tympanocentesis-proven etiology of infection) and non-OP children. We showed that about 90% of OP children have deficient immune responses following nasopharyngeal colonization and AOM, demonstrated by inadequate innate responses and adaptive immune responses.2 Many of these children also showed an increased propensity to viral upper respiratory infection and 30% fail to produce protective antibody responses after injection of routine pediatric vaccines.3,4

In this column, I want to share new information regarding differences in the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children who are respiratory infection prone versus those who are non–respiratory infection prone and children with asthma versus those who do not exhibit that clinical phenotype. We performed a retrospective analysis of clinical samples collected from 358 children, aged 6 months to 5 years, from our prospectively enrolled cohort in Rochester, N.Y., to determine associations between AOM and other childhood respiratory illnesses and nasopharyngeal microbiota. In order to define subgroups of children within the cohort, we used a statistical method called unsupervised clustering analysis to see if relatively unique groups of children could be discerned. The overall cohort successfully clustered into two groups, showing marked differences in the prevalence of respiratory infections and asthma.5 We termed the two clinical phenotypes infection and asthma prone (n = 99, 28% of the children) and non–infection and asthma prone (n = 259, 72% of the children). Infection- and asthma-prone children were significantly more likely to experience recurrent AOM, influenza, sinusitis, pneumonia, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, compared with non–infection- and asthma-prone children (Figure).

The two groups did not experience significantly different rates of eczema, food allergy, skin infections, urinary tract infections, or acute gastroenteritis, suggesting a common thread involving the respiratory tract that did not cross over to the gastrointestinal, skin, or urinary tract. We found that age at first nasopharyngeal colonization with any of the three bacterial respiratory pathogens (pneumococcus, Hflu, or Mcat) was significantly associated with the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Specifically, respiratory infection– and asthma-prone children experienced colonization at a significantly earlier age than nonprone children did for all three bacteria. In an analysis of individual conditions, early Mcat colonization significantly associated with pneumonia, sinusitis, and asthma susceptibility; Hflu with pneumonia, sinusitis, influenza, and allergic rhinitis; and pneumococcus with sinusitis.

Since early colonization with the three bacterial respiratory pathogens was strongly associated with respiratory illnesses and asthma, nasopharyngeal microbiome analysis was performed on an available subset of samples. Bacterial diversity trended lower in infection- and asthma-prone children, consistent with dysbiosis in the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone clinical phenotype. Nine different bacteria genera were found to be differentially abundant when comparing respiratory infection– and asthma-prone and nonprone children, pointing the way to possible interventions to make the respiratory infection– and asthma-prone child nasopharyngeal microbiome more like the nonprone child.

As I have written previously in this column, recent accumulating data have shed light on the importance of the human microbiome in modulating immune homeostasis and disease susceptibility.6 My group is working toward generating new knowledge for the long-term goal of identifying new therapeutic strategies to facilitate a protective, diverse nasopharyngeal microbiome (with appropriately tuned intranasal probiotics) to prevent respiratory pathogen colonization and/or subsequent progression to respiratory infection and asthma. Also, vaccines directed against colonization-enhancing members of the microbiome may provide a means to indirectly control respiratory pathogen nasopharyngeal colonization.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts to declare. Contact him at [email protected]

References

1. Man WH et al. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15(5):259-70.

2. Pichichero ME. J Infect. 2020;80(6):614-22.

3. Ren D et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(9):1566-74.

4. Pichichero ME et al. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(11):1163-8.

5. Chapman T et al. PLoS One. 2020 Dec 11;15(12).

6. Blaser MJ. The microbiome revolution. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4162-5.

Nadolol bests propranolol for infantile hemangioma treatment out to 52 weeks

of 71 patients showed.

“In clinical practice, we notice that nadolol works very well in terms of controlling the size and the appearance of the hemangioma,” lead study author Elena Pope, MD, MSc, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Hence, she and her colleagues were interested in comparing their clinical experience with the standard treatment with propranolol, and designed a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study, with the aim of proving that “nadolol is noninferior to propranolol, with a margin of noninferiority of 10%.”

Between 2016 and 2020, Dr. Pope and colleagues at two academic Canadian pediatric dermatology centers enrolled 71 infants aged 1-6 months with significant hemangioma that had either the potential for functional impairment or cosmetic deformity, defined as a lesion greater than 1.5 cm on the face or greater than 3 cm on another body part. Treatment consisted of oral propranolol or nadolol in escalating doses up to 2 mg/kg per day. “The blinding portion of the study was for 24 weeks with a follow-up up to 52 weeks,” said Dr. Pope, professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto and section head of pediatric dermatology at The Hospital for Sick Children, also in Toronto. “After the unblinding at 24 weeks, patients were allowed to switch their intervention if they were not happy with the results.”

Of the 71 patients, 35 received nadolol and 36 received propranolol. The two groups were similar in terms of clinical and demographic characteristics. Their mean age at enrollment was 3.15 months, 80% were female, 61% were White, 20% were Asian, and the rest were from other ethnic backgrounds.

At 24 weeks, the researchers found that the mean size involution was 97.94% in the nadolol group and 89.14% in the propranolol group (P = .005), while the mean color fading on the visual analogue scale (VAS) was 94.47% in the nadolol group and 80.54% in the propranolol group (P < .001). At 52 weeks, the mean size involution was 99.63% in the nadolol group and 93.63% in the propranolol group (P = .001), while the mean VAS color fading was 97.34% in the nadolol group and 87.23% in the propranolol group (P = .001).

According to Dr. Pope, Kaplan-Meir analysis showed that patients in the propranolol group responded slower to treatment (P = .019), while safety data was similar between the two groups. For example, between weeks 25 and 52, 84.2% of patients in the nadolol group experienced an adverse event, compared with 74.2% of patients in the propranolol group (P = .466). The most common respiratory adverse event was upper respiratory tract infection, which affected 87.5% of patients in the nadolol group, compared with 100% of patients in the propranolol group (P = 0.341).

The most common gastrointestinal adverse event was diarrhea, which affected 66.7% of patients in both groups. One patient in the propranolol group was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and fully recovered. The incident was not suspected to be related to the medication.

“We believe that this data backs up our clinical experience and it may offer an alternative treatment in other centers where patients experience propranolol unresponsiveness, side effects, or intolerance, or where a fast response is needed,” Dr. Pope said. As for the potential cost implications, “nadolol is cheaper than the Hemangiol but comparable with the compounded formulation of propranolol.”

Concern over the safety of nadolol was raised in a case report published in Pediatrics in 2020. Authors from Alberta reported the case of a 10-week-old girl who was started on nadolol for infantile hemangioma, died 7 weeks later, and was found to have an elevated postmortem cardiac blood nadolol level of 0.94 mg/L. “The infant had no bowel movements for 10 days before her death, which we hypothesize contributed to nadolol toxicity,” the authors wrote.

In a reply to the authors in the same issue of Pediatrics, Dr. Pope, Cathryn Sibbald, MD, and Erin Chung, PhD, pointed out that postmortem redistribution of medications “is complex and measured postmortem cardiac blood concentrations may be significantly higher than the true blood nadolol concentration at the time of death due to significant diffusion from the peripheral tissues.”

They added that the report did not address “other potential errors such as in compounding, dispensing, and administration of the solution,” they wrote, adding: “Finally, we are aware of a Canadian case of death in an infant receiving propranolol, although the cause of death in that case was unable to be determined (ISMP Canada 2016 Safety Bulletin).We agree with the authors that careful consideration of the risks and benefits of beta-blocker therapy should be employed, parents need to be informed when to discontinue therapy and that further research into the pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of beta-blockers are warranted.”

Following publication of the case report in Pediatrics, Dr. Pope said that the only change she made in her practice was to ask families to temporarily discontinue nadolol if their child had constipation for more than 5 days.

The study was supported by a grant from Physician Services, Inc. Dr. Pope reported having no financial disclosures.

of 71 patients showed.

“In clinical practice, we notice that nadolol works very well in terms of controlling the size and the appearance of the hemangioma,” lead study author Elena Pope, MD, MSc, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. Hence, she and her colleagues were interested in comparing their clinical experience with the standard treatment with propranolol, and designed a prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blinded study, with the aim of proving that “nadolol is noninferior to propranolol, with a margin of noninferiority of 10%.”