User login

The COVID-19 push to evolve

Has anyone else noticed how slow it has been on your pediatric floors? Well, you are not alone.

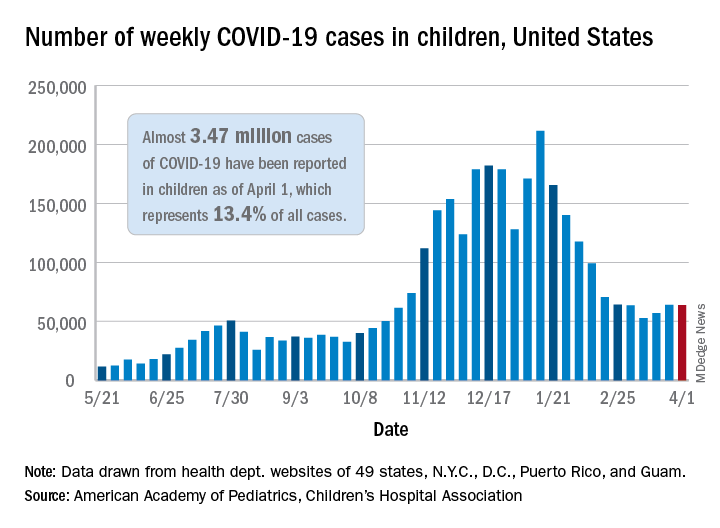

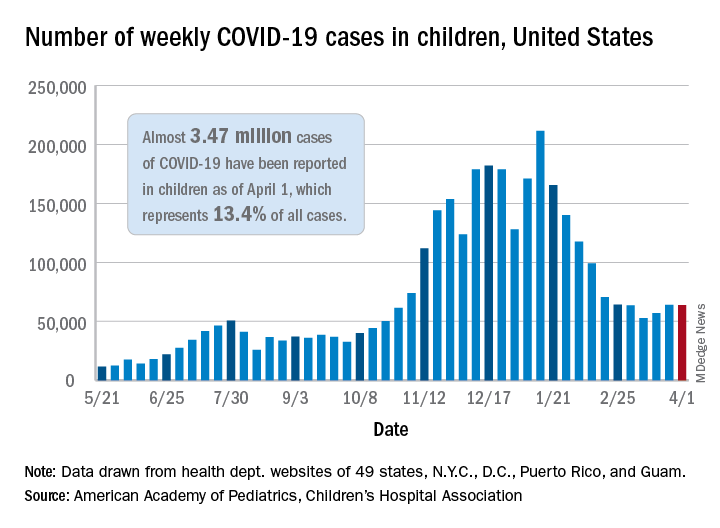

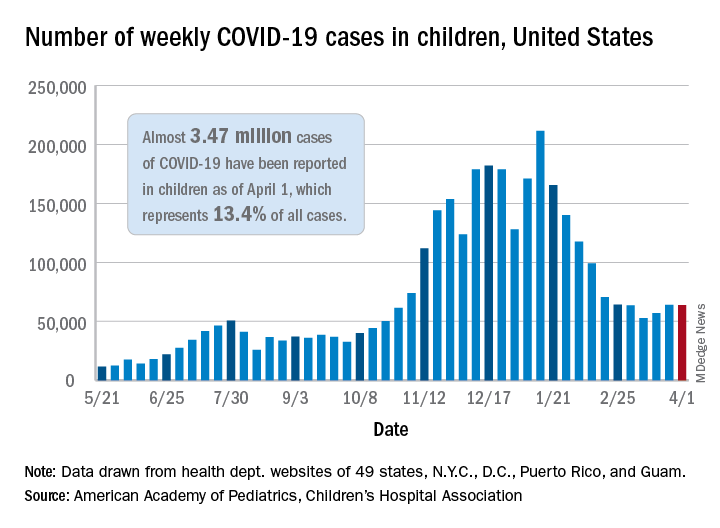

The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on health care volumes, with pediatric volumes decreasing across the nation. A Children’s Hospital Association CEO survey, currently unpublished, noted a 10%-20% decline in inpatient admissions and a 30%-50% decline in pediatric ED visits this past year. Even our usual respiratory surge has been disrupted. The rate of influenza tracked by the CDC is around 1%, compared with the usual seasonal flu baseline national rate of 2.6%. These COVID-related declines have occurred amidst the backdrop of already-decreasing inpatient admissions because of the great work of the pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) community in reducing unnecessary admissions and lengths of stay.

For many hospitals, several factors related to the pandemic have raised significant financial concerns. According to Becker Hospital Review, as of August 2020 over 500 hospitals had furloughed workers. While 26 of those hospitals had brought back workers by December 2020, many did not. Similar financial concerns were noted in a Kaufmann Hall report from January 2021, which showed a median drop of 55% in operating margins. The CARES Act helped reduce some of the detrimental impact on operating margins, but it did not diminish the added burden of personal protective equipment expenses, longer length of stay for COVID patients, and a reimbursement shift to more government payors and uninsured caused by pandemic-forced job losses.

COVID’s impact specific to pediatric hospital medicine has been substantial. A recent unpublished survey by the PHM Economics Research Collaborative (PERC) demonstrated how COVID has affected pediatric hospital medicine programs. Forty-five unique PHM programs from over 21 states responded, with 98% reporting a decrease in pediatric inpatient admissions as well as ED visits. About 11% reported temporary unit closures, while 51% of all programs reported staffing restrictions ranging from hiring freezes to downsizing the number of hospitalists in the group. Salaries decreased in 26% of reporting programs, and 20%-56% described reduced benefits, ranging from less CME/vacation time and stipends to retirement benefits. The three most frequent benefit losses included annual salary increases, educational stipends, and bonuses.

Community hospitals felt the palpable, financial strain of decreasing pediatric admissions well before the pandemic. Hospitals like MedStar Franklin Square Hospital in Baltimore and Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Mass., had decided to close their pediatrics units before COVID hit. In a 2014 unpublished survey of 349 community PHM (CPHM) programs, 57% of respondents felt that finances and justification for a pediatric program were primary concerns.

Responding to financial stressors is not a novel challenge for CPHM programs. To keep these vital pediatric programs in place despite lower inpatient volumes, those of us in CPHM have learned many lessons over the years on how to adapt. Such adaptations have included diversification in procedures and multifloor coverage in the hospital. Voiding cystourethrogram catheterizations and circumcisions are now more commonly performed by CPHM providers, who may also cover multiple areas of the hospital, including the ED, NICU, and well-newborn nursery. Comanagement of subspecialty or surgical patients is yet another example of such diversification.

Furthermore, the PERC survey showed that some PHM programs temporarily covered pediatric ICUs and step-down units and began doing ED and urgent care coverage as primary providers Most programs reported no change in newborn visits while 16% reported an increase in newborn volume and 14% reported a decrease in newborn volume. My own health system was one of the groups that had an increase in newborn volume. This was caused by community pediatricians who had stopped coming in to see their own newborns. This coverage adjustment has yet to return to baseline and will likely become permanent.

There was a 11% increase from prepandemic baselines (from 9% to 20%) in programs doing telemedicine. Most respondents stated that they will continue to offer telemedicine with an additional 25% of programs considering starting. There was also a slight increase during the pandemic of coverage of mental health units (from 11% to 13%), which may have led 11% of respondents to consider the addition of this service. The survey also noted that about 28% of PHM programs performed circumcisions, frenectomies, and sedation prepandemic, and 14%-18% are considering adding these services.

Overall, the financial stressors are improving, but our need to adapt in PHM is more pressing than ever. The pandemic has given us the push for evolution and some opportunities that did not exist before. One is the use of telemedicine to expand our subspecialty support to community hospitals, as well as to children’s hospitals in areas where subspecialists are in short supply. These telemedicine consults are being reimbursed for the first time, which allows more access to these services.

With the pandemic, many hospitals are moving to single room occupancy models. Construction to add more beds is costly, and unnecessary if we can utilize community hospitals to keep appropriate patients in their home communities. The opportunity to partner with community hospital programs to provide telemedicine support should not be overlooked. This is also an opportunity for academic referral centers to have more open beds for critical care and highly specialized patients.

Another opportunity is to expand scope by changing age limits, as 18% of respondents to the PERC survey reported that they had started to care for adults since the pandemic. The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN) has been a valuable resource for education on caring for adults, guidance on which patient populations are appropriate, and the resources needed to do this. While caring for older adults, even in their 90s, was a pandemic-related phenomenon, there is an opportunity to see if the age limit we care for should be raised to 21, or even 25, as some CPHM programs had been doing prepandemic.

Along with the expansion of age limits, there are many other areas of opportunity highlighted within the PERC survey. These include expanding coverage within pediatric ICUs, EDs, and urgent care areas, along with coverage of well newborns that were previously covered by community pediatricians. Also, the increase of mental health admissions is another area where PHM programs might expand their services.

While I hope the financial stressors improve, hope is not a plan and therefore we need to think and prepare for what the post-COVID future may look like. Some have predicted a rebound pediatric respiratory surge next year as the masks come off and children return to in-person learning and daycare. This may be true, but we would be foolish not to use lessons from the pandemic as well as the past to consider options in our toolkit to become more financially stable. POPCoRN, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ listserv and subcommittees, have been a source of collaboration and shared knowledge during a time when we have needed to quickly respond to ever-changing information. These networks and information sharing should be leveraged once the dust settles for us to prepare for future challenges.

New innovations may arise as we look at how we address the growing need for mental health services and incorporate new procedures, like point of care ultrasound. As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.” It is time for us to evolve.

Dr. Dias is a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in the division of pediatric hospital medicine. She has practiced community pediatric hospital medicine for over 21 years in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. She is the chair of the Education Working Group for the AAP’s section on hospital medicine’s subcommittee on community hospitalists as well as the cochair of the Community Hospital Operations Group of the POPCoRN network.

Has anyone else noticed how slow it has been on your pediatric floors? Well, you are not alone.

The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on health care volumes, with pediatric volumes decreasing across the nation. A Children’s Hospital Association CEO survey, currently unpublished, noted a 10%-20% decline in inpatient admissions and a 30%-50% decline in pediatric ED visits this past year. Even our usual respiratory surge has been disrupted. The rate of influenza tracked by the CDC is around 1%, compared with the usual seasonal flu baseline national rate of 2.6%. These COVID-related declines have occurred amidst the backdrop of already-decreasing inpatient admissions because of the great work of the pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) community in reducing unnecessary admissions and lengths of stay.

For many hospitals, several factors related to the pandemic have raised significant financial concerns. According to Becker Hospital Review, as of August 2020 over 500 hospitals had furloughed workers. While 26 of those hospitals had brought back workers by December 2020, many did not. Similar financial concerns were noted in a Kaufmann Hall report from January 2021, which showed a median drop of 55% in operating margins. The CARES Act helped reduce some of the detrimental impact on operating margins, but it did not diminish the added burden of personal protective equipment expenses, longer length of stay for COVID patients, and a reimbursement shift to more government payors and uninsured caused by pandemic-forced job losses.

COVID’s impact specific to pediatric hospital medicine has been substantial. A recent unpublished survey by the PHM Economics Research Collaborative (PERC) demonstrated how COVID has affected pediatric hospital medicine programs. Forty-five unique PHM programs from over 21 states responded, with 98% reporting a decrease in pediatric inpatient admissions as well as ED visits. About 11% reported temporary unit closures, while 51% of all programs reported staffing restrictions ranging from hiring freezes to downsizing the number of hospitalists in the group. Salaries decreased in 26% of reporting programs, and 20%-56% described reduced benefits, ranging from less CME/vacation time and stipends to retirement benefits. The three most frequent benefit losses included annual salary increases, educational stipends, and bonuses.

Community hospitals felt the palpable, financial strain of decreasing pediatric admissions well before the pandemic. Hospitals like MedStar Franklin Square Hospital in Baltimore and Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Mass., had decided to close their pediatrics units before COVID hit. In a 2014 unpublished survey of 349 community PHM (CPHM) programs, 57% of respondents felt that finances and justification for a pediatric program were primary concerns.

Responding to financial stressors is not a novel challenge for CPHM programs. To keep these vital pediatric programs in place despite lower inpatient volumes, those of us in CPHM have learned many lessons over the years on how to adapt. Such adaptations have included diversification in procedures and multifloor coverage in the hospital. Voiding cystourethrogram catheterizations and circumcisions are now more commonly performed by CPHM providers, who may also cover multiple areas of the hospital, including the ED, NICU, and well-newborn nursery. Comanagement of subspecialty or surgical patients is yet another example of such diversification.

Furthermore, the PERC survey showed that some PHM programs temporarily covered pediatric ICUs and step-down units and began doing ED and urgent care coverage as primary providers Most programs reported no change in newborn visits while 16% reported an increase in newborn volume and 14% reported a decrease in newborn volume. My own health system was one of the groups that had an increase in newborn volume. This was caused by community pediatricians who had stopped coming in to see their own newborns. This coverage adjustment has yet to return to baseline and will likely become permanent.

There was a 11% increase from prepandemic baselines (from 9% to 20%) in programs doing telemedicine. Most respondents stated that they will continue to offer telemedicine with an additional 25% of programs considering starting. There was also a slight increase during the pandemic of coverage of mental health units (from 11% to 13%), which may have led 11% of respondents to consider the addition of this service. The survey also noted that about 28% of PHM programs performed circumcisions, frenectomies, and sedation prepandemic, and 14%-18% are considering adding these services.

Overall, the financial stressors are improving, but our need to adapt in PHM is more pressing than ever. The pandemic has given us the push for evolution and some opportunities that did not exist before. One is the use of telemedicine to expand our subspecialty support to community hospitals, as well as to children’s hospitals in areas where subspecialists are in short supply. These telemedicine consults are being reimbursed for the first time, which allows more access to these services.

With the pandemic, many hospitals are moving to single room occupancy models. Construction to add more beds is costly, and unnecessary if we can utilize community hospitals to keep appropriate patients in their home communities. The opportunity to partner with community hospital programs to provide telemedicine support should not be overlooked. This is also an opportunity for academic referral centers to have more open beds for critical care and highly specialized patients.

Another opportunity is to expand scope by changing age limits, as 18% of respondents to the PERC survey reported that they had started to care for adults since the pandemic. The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN) has been a valuable resource for education on caring for adults, guidance on which patient populations are appropriate, and the resources needed to do this. While caring for older adults, even in their 90s, was a pandemic-related phenomenon, there is an opportunity to see if the age limit we care for should be raised to 21, or even 25, as some CPHM programs had been doing prepandemic.

Along with the expansion of age limits, there are many other areas of opportunity highlighted within the PERC survey. These include expanding coverage within pediatric ICUs, EDs, and urgent care areas, along with coverage of well newborns that were previously covered by community pediatricians. Also, the increase of mental health admissions is another area where PHM programs might expand their services.

While I hope the financial stressors improve, hope is not a plan and therefore we need to think and prepare for what the post-COVID future may look like. Some have predicted a rebound pediatric respiratory surge next year as the masks come off and children return to in-person learning and daycare. This may be true, but we would be foolish not to use lessons from the pandemic as well as the past to consider options in our toolkit to become more financially stable. POPCoRN, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ listserv and subcommittees, have been a source of collaboration and shared knowledge during a time when we have needed to quickly respond to ever-changing information. These networks and information sharing should be leveraged once the dust settles for us to prepare for future challenges.

New innovations may arise as we look at how we address the growing need for mental health services and incorporate new procedures, like point of care ultrasound. As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.” It is time for us to evolve.

Dr. Dias is a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in the division of pediatric hospital medicine. She has practiced community pediatric hospital medicine for over 21 years in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. She is the chair of the Education Working Group for the AAP’s section on hospital medicine’s subcommittee on community hospitalists as well as the cochair of the Community Hospital Operations Group of the POPCoRN network.

Has anyone else noticed how slow it has been on your pediatric floors? Well, you are not alone.

The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on health care volumes, with pediatric volumes decreasing across the nation. A Children’s Hospital Association CEO survey, currently unpublished, noted a 10%-20% decline in inpatient admissions and a 30%-50% decline in pediatric ED visits this past year. Even our usual respiratory surge has been disrupted. The rate of influenza tracked by the CDC is around 1%, compared with the usual seasonal flu baseline national rate of 2.6%. These COVID-related declines have occurred amidst the backdrop of already-decreasing inpatient admissions because of the great work of the pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) community in reducing unnecessary admissions and lengths of stay.

For many hospitals, several factors related to the pandemic have raised significant financial concerns. According to Becker Hospital Review, as of August 2020 over 500 hospitals had furloughed workers. While 26 of those hospitals had brought back workers by December 2020, many did not. Similar financial concerns were noted in a Kaufmann Hall report from January 2021, which showed a median drop of 55% in operating margins. The CARES Act helped reduce some of the detrimental impact on operating margins, but it did not diminish the added burden of personal protective equipment expenses, longer length of stay for COVID patients, and a reimbursement shift to more government payors and uninsured caused by pandemic-forced job losses.

COVID’s impact specific to pediatric hospital medicine has been substantial. A recent unpublished survey by the PHM Economics Research Collaborative (PERC) demonstrated how COVID has affected pediatric hospital medicine programs. Forty-five unique PHM programs from over 21 states responded, with 98% reporting a decrease in pediatric inpatient admissions as well as ED visits. About 11% reported temporary unit closures, while 51% of all programs reported staffing restrictions ranging from hiring freezes to downsizing the number of hospitalists in the group. Salaries decreased in 26% of reporting programs, and 20%-56% described reduced benefits, ranging from less CME/vacation time and stipends to retirement benefits. The three most frequent benefit losses included annual salary increases, educational stipends, and bonuses.

Community hospitals felt the palpable, financial strain of decreasing pediatric admissions well before the pandemic. Hospitals like MedStar Franklin Square Hospital in Baltimore and Harrington Hospital in Southbridge, Mass., had decided to close their pediatrics units before COVID hit. In a 2014 unpublished survey of 349 community PHM (CPHM) programs, 57% of respondents felt that finances and justification for a pediatric program were primary concerns.

Responding to financial stressors is not a novel challenge for CPHM programs. To keep these vital pediatric programs in place despite lower inpatient volumes, those of us in CPHM have learned many lessons over the years on how to adapt. Such adaptations have included diversification in procedures and multifloor coverage in the hospital. Voiding cystourethrogram catheterizations and circumcisions are now more commonly performed by CPHM providers, who may also cover multiple areas of the hospital, including the ED, NICU, and well-newborn nursery. Comanagement of subspecialty or surgical patients is yet another example of such diversification.

Furthermore, the PERC survey showed that some PHM programs temporarily covered pediatric ICUs and step-down units and began doing ED and urgent care coverage as primary providers Most programs reported no change in newborn visits while 16% reported an increase in newborn volume and 14% reported a decrease in newborn volume. My own health system was one of the groups that had an increase in newborn volume. This was caused by community pediatricians who had stopped coming in to see their own newborns. This coverage adjustment has yet to return to baseline and will likely become permanent.

There was a 11% increase from prepandemic baselines (from 9% to 20%) in programs doing telemedicine. Most respondents stated that they will continue to offer telemedicine with an additional 25% of programs considering starting. There was also a slight increase during the pandemic of coverage of mental health units (from 11% to 13%), which may have led 11% of respondents to consider the addition of this service. The survey also noted that about 28% of PHM programs performed circumcisions, frenectomies, and sedation prepandemic, and 14%-18% are considering adding these services.

Overall, the financial stressors are improving, but our need to adapt in PHM is more pressing than ever. The pandemic has given us the push for evolution and some opportunities that did not exist before. One is the use of telemedicine to expand our subspecialty support to community hospitals, as well as to children’s hospitals in areas where subspecialists are in short supply. These telemedicine consults are being reimbursed for the first time, which allows more access to these services.

With the pandemic, many hospitals are moving to single room occupancy models. Construction to add more beds is costly, and unnecessary if we can utilize community hospitals to keep appropriate patients in their home communities. The opportunity to partner with community hospital programs to provide telemedicine support should not be overlooked. This is also an opportunity for academic referral centers to have more open beds for critical care and highly specialized patients.

Another opportunity is to expand scope by changing age limits, as 18% of respondents to the PERC survey reported that they had started to care for adults since the pandemic. The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN) has been a valuable resource for education on caring for adults, guidance on which patient populations are appropriate, and the resources needed to do this. While caring for older adults, even in their 90s, was a pandemic-related phenomenon, there is an opportunity to see if the age limit we care for should be raised to 21, or even 25, as some CPHM programs had been doing prepandemic.

Along with the expansion of age limits, there are many other areas of opportunity highlighted within the PERC survey. These include expanding coverage within pediatric ICUs, EDs, and urgent care areas, along with coverage of well newborns that were previously covered by community pediatricians. Also, the increase of mental health admissions is another area where PHM programs might expand their services.

While I hope the financial stressors improve, hope is not a plan and therefore we need to think and prepare for what the post-COVID future may look like. Some have predicted a rebound pediatric respiratory surge next year as the masks come off and children return to in-person learning and daycare. This may be true, but we would be foolish not to use lessons from the pandemic as well as the past to consider options in our toolkit to become more financially stable. POPCoRN, as well as the American Academy of Pediatrics’ listserv and subcommittees, have been a source of collaboration and shared knowledge during a time when we have needed to quickly respond to ever-changing information. These networks and information sharing should be leveraged once the dust settles for us to prepare for future challenges.

New innovations may arise as we look at how we address the growing need for mental health services and incorporate new procedures, like point of care ultrasound. As Charles Darwin said: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.” It is time for us to evolve.

Dr. Dias is a clinical associate professor of pediatrics at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in the division of pediatric hospital medicine. She has practiced community pediatric hospital medicine for over 21 years in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. She is the chair of the Education Working Group for the AAP’s section on hospital medicine’s subcommittee on community hospitalists as well as the cochair of the Community Hospital Operations Group of the POPCoRN network.

Cardiovascular risks elevated in transgender youth

Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors are increased among transgender youths, compared with youths who are not transgender. Elevations in lipid levels and body mass index (BMI) also occur in adult transgender patients, new research shows.

“This is the first study of its size in the United States of which we are aware that looks at the odds of youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria having medical diagnoses that relate to overall metabolic and cardiovascular health,” first author Anna Valentine, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said in a press statement.

Although previous studies have shown that among transgender adults, BMI is higher and there is an increased risk for cardiovascular events, such as stroke or heart attack, compared with nontransgender people, research on adolescent transgender patients has been lacking.

With a recent survey showing that nearly 2% of adolescents identify as transgender, interest in health outcomes among younger patients is high.

To investigate, Dr. Valentine, and colleagues evaluated data from the PEDSnet pediatric database on 4,177 youths who had received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. The participants had been enrolled at six sites from 2009 to 2019. The researchers compared these patients in a ratio of 1:4 with 16,664 control persons who had not been diagnosed with gender dysphoria. They reported their findings as a poster at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

For the propensity-score analysis, participants were matched according to year of birth, age at last visit, site, race, ethnicity, insurance status, and duration in the database.

In both the transgender and control groups, about 66% were female at birth, 73% were White, and 9% Hispanic. For both groups, the average age was 16.2 years at the last visit. The average duration in the database was 7 years.

Study didn’t distinguish between those receiving and those not receiving gender-affirming hormones

In the retrospective study, among those who identified as transgender, the rates of diagnoses of dyslipidemia (odds ratio, 1.6; P < .0001) and metabolic syndrome (OR, 1.9; P = .0086) were significantly higher, compared with those without gender dysphoria.

Among the transgender male patients (born female) but not transgender female patients (born male), rates of diagnoses of overweight/obesity (OR, 1.7; P < .0001) and polycystic ovary syndrome were higher (OR, 1.9, P = .0006), compared with controls.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy, such as with testosterone or estradiol, is among the suspected culprits for the cardiovascular effects. However, importantly, this study did not differentiate between patients who had received estradiol or testosterone for gender affirmation and those who had not, Dr. Valentine said.

“We don’t know [whether gender-affirming hormone therapy is a cause], as we have not looked at this yet,” she said in an interview. “We are looking at that in our next analyses and will be including that in our future publication.

“We’ll also be looking at the relationship between having overweight/obesity and the other diagnoses that influence cardiovascular health (high blood pressure, liver dysfunction, and abnormal cholesterol), as that could certainly be playing a role as well,” she said.

For many transgender patients, gender-affirming hormone therapy is lifelong. One question that needs to be evaluated concerns whether the dose of such therapy has a role on cardiovascular effects and if so, whether adjustments could be made without compromising the therapeutic effect, Dr. Valentine noted.

“This is an important question, and future research is needed to evaluate whether doses [of gender-affirming hormones] are related to cardiometabolic outcomes,” she said.

Potential confounders in the study include the fact that rates of overweight and obesity are higher among youths with gender dysphoria. This can in itself can increase the risk for other disorders, Dr. Valentine noted.

Furthermore, rates of mental health comorbidities are higher among youths with gender dysphoria. One consequence of this may be that they engage in less physical activity, she said.

Hormone therapy, health care disparities, or both could explain risk

In commenting on the study, Joshua D. Safer, MD, executive director of the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, the Mount Sinai Health System, New York, said that although similar cardiovascular effects are known to occur in transgender adults as well, they may or may not be hormone related. Other factors can increase the risk.

“With transgender adults, any differences in lipids or cardiac risk factors relative to cisgender people might be attributable either to hormone therapy or to health care disparities,” he said in an interview.

“The data are mixed. It may be that most differences relate to lack of access to care and to mistreatment by society,” he said. “Even studies that focus on hormones see a worsened situation for trans women versus trans men.”

Other recent research that shows potential cardiovascular effects among adult transgender men includes a study of more than 1,000 transgender men (born female) who received testosterone. That study, which was also presented at the ENDO meeting and was reported by this news organization, found an increased risk for high hematocrit levels, which could lead to a thrombotic event.

However, a study published in Pediatrics, which was also reported by this news organization, that included 611 transgender youths who had taken gender-affirming hormone therapy for more than a year found no increased risk for thrombosis, even in the presence of thrombosis risk factors, including obesity, tobacco use, and family history of thrombosis. However, the senior author of that study pointed out that the duration of follow-up in that study was relatively short, which may have been why they did not find an increased risk for thrombosis.

Dr. Safer noted that transgender youths and adults alike face a host of cultural factors that could play a role in increased cardiovascular risks.

“For adults, the major candidate explanations for worse BMI and cardiac risk factors are societal mistreatment, and for trans women specifically, progestins. For youth, the major candidate explanations are societal mistreatment and lack of access to athletics,” he said.

The authors and Dr. Safer disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors are increased among transgender youths, compared with youths who are not transgender. Elevations in lipid levels and body mass index (BMI) also occur in adult transgender patients, new research shows.

“This is the first study of its size in the United States of which we are aware that looks at the odds of youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria having medical diagnoses that relate to overall metabolic and cardiovascular health,” first author Anna Valentine, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said in a press statement.

Although previous studies have shown that among transgender adults, BMI is higher and there is an increased risk for cardiovascular events, such as stroke or heart attack, compared with nontransgender people, research on adolescent transgender patients has been lacking.

With a recent survey showing that nearly 2% of adolescents identify as transgender, interest in health outcomes among younger patients is high.

To investigate, Dr. Valentine, and colleagues evaluated data from the PEDSnet pediatric database on 4,177 youths who had received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. The participants had been enrolled at six sites from 2009 to 2019. The researchers compared these patients in a ratio of 1:4 with 16,664 control persons who had not been diagnosed with gender dysphoria. They reported their findings as a poster at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

For the propensity-score analysis, participants were matched according to year of birth, age at last visit, site, race, ethnicity, insurance status, and duration in the database.

In both the transgender and control groups, about 66% were female at birth, 73% were White, and 9% Hispanic. For both groups, the average age was 16.2 years at the last visit. The average duration in the database was 7 years.

Study didn’t distinguish between those receiving and those not receiving gender-affirming hormones

In the retrospective study, among those who identified as transgender, the rates of diagnoses of dyslipidemia (odds ratio, 1.6; P < .0001) and metabolic syndrome (OR, 1.9; P = .0086) were significantly higher, compared with those without gender dysphoria.

Among the transgender male patients (born female) but not transgender female patients (born male), rates of diagnoses of overweight/obesity (OR, 1.7; P < .0001) and polycystic ovary syndrome were higher (OR, 1.9, P = .0006), compared with controls.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy, such as with testosterone or estradiol, is among the suspected culprits for the cardiovascular effects. However, importantly, this study did not differentiate between patients who had received estradiol or testosterone for gender affirmation and those who had not, Dr. Valentine said.

“We don’t know [whether gender-affirming hormone therapy is a cause], as we have not looked at this yet,” she said in an interview. “We are looking at that in our next analyses and will be including that in our future publication.

“We’ll also be looking at the relationship between having overweight/obesity and the other diagnoses that influence cardiovascular health (high blood pressure, liver dysfunction, and abnormal cholesterol), as that could certainly be playing a role as well,” she said.

For many transgender patients, gender-affirming hormone therapy is lifelong. One question that needs to be evaluated concerns whether the dose of such therapy has a role on cardiovascular effects and if so, whether adjustments could be made without compromising the therapeutic effect, Dr. Valentine noted.

“This is an important question, and future research is needed to evaluate whether doses [of gender-affirming hormones] are related to cardiometabolic outcomes,” she said.

Potential confounders in the study include the fact that rates of overweight and obesity are higher among youths with gender dysphoria. This can in itself can increase the risk for other disorders, Dr. Valentine noted.

Furthermore, rates of mental health comorbidities are higher among youths with gender dysphoria. One consequence of this may be that they engage in less physical activity, she said.

Hormone therapy, health care disparities, or both could explain risk

In commenting on the study, Joshua D. Safer, MD, executive director of the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, the Mount Sinai Health System, New York, said that although similar cardiovascular effects are known to occur in transgender adults as well, they may or may not be hormone related. Other factors can increase the risk.

“With transgender adults, any differences in lipids or cardiac risk factors relative to cisgender people might be attributable either to hormone therapy or to health care disparities,” he said in an interview.

“The data are mixed. It may be that most differences relate to lack of access to care and to mistreatment by society,” he said. “Even studies that focus on hormones see a worsened situation for trans women versus trans men.”

Other recent research that shows potential cardiovascular effects among adult transgender men includes a study of more than 1,000 transgender men (born female) who received testosterone. That study, which was also presented at the ENDO meeting and was reported by this news organization, found an increased risk for high hematocrit levels, which could lead to a thrombotic event.

However, a study published in Pediatrics, which was also reported by this news organization, that included 611 transgender youths who had taken gender-affirming hormone therapy for more than a year found no increased risk for thrombosis, even in the presence of thrombosis risk factors, including obesity, tobacco use, and family history of thrombosis. However, the senior author of that study pointed out that the duration of follow-up in that study was relatively short, which may have been why they did not find an increased risk for thrombosis.

Dr. Safer noted that transgender youths and adults alike face a host of cultural factors that could play a role in increased cardiovascular risks.

“For adults, the major candidate explanations for worse BMI and cardiac risk factors are societal mistreatment, and for trans women specifically, progestins. For youth, the major candidate explanations are societal mistreatment and lack of access to athletics,” he said.

The authors and Dr. Safer disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors are increased among transgender youths, compared with youths who are not transgender. Elevations in lipid levels and body mass index (BMI) also occur in adult transgender patients, new research shows.

“This is the first study of its size in the United States of which we are aware that looks at the odds of youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria having medical diagnoses that relate to overall metabolic and cardiovascular health,” first author Anna Valentine, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, said in a press statement.

Although previous studies have shown that among transgender adults, BMI is higher and there is an increased risk for cardiovascular events, such as stroke or heart attack, compared with nontransgender people, research on adolescent transgender patients has been lacking.

With a recent survey showing that nearly 2% of adolescents identify as transgender, interest in health outcomes among younger patients is high.

To investigate, Dr. Valentine, and colleagues evaluated data from the PEDSnet pediatric database on 4,177 youths who had received a diagnosis of gender dysphoria. The participants had been enrolled at six sites from 2009 to 2019. The researchers compared these patients in a ratio of 1:4 with 16,664 control persons who had not been diagnosed with gender dysphoria. They reported their findings as a poster at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

For the propensity-score analysis, participants were matched according to year of birth, age at last visit, site, race, ethnicity, insurance status, and duration in the database.

In both the transgender and control groups, about 66% were female at birth, 73% were White, and 9% Hispanic. For both groups, the average age was 16.2 years at the last visit. The average duration in the database was 7 years.

Study didn’t distinguish between those receiving and those not receiving gender-affirming hormones

In the retrospective study, among those who identified as transgender, the rates of diagnoses of dyslipidemia (odds ratio, 1.6; P < .0001) and metabolic syndrome (OR, 1.9; P = .0086) were significantly higher, compared with those without gender dysphoria.

Among the transgender male patients (born female) but not transgender female patients (born male), rates of diagnoses of overweight/obesity (OR, 1.7; P < .0001) and polycystic ovary syndrome were higher (OR, 1.9, P = .0006), compared with controls.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy, such as with testosterone or estradiol, is among the suspected culprits for the cardiovascular effects. However, importantly, this study did not differentiate between patients who had received estradiol or testosterone for gender affirmation and those who had not, Dr. Valentine said.

“We don’t know [whether gender-affirming hormone therapy is a cause], as we have not looked at this yet,” she said in an interview. “We are looking at that in our next analyses and will be including that in our future publication.

“We’ll also be looking at the relationship between having overweight/obesity and the other diagnoses that influence cardiovascular health (high blood pressure, liver dysfunction, and abnormal cholesterol), as that could certainly be playing a role as well,” she said.

For many transgender patients, gender-affirming hormone therapy is lifelong. One question that needs to be evaluated concerns whether the dose of such therapy has a role on cardiovascular effects and if so, whether adjustments could be made without compromising the therapeutic effect, Dr. Valentine noted.

“This is an important question, and future research is needed to evaluate whether doses [of gender-affirming hormones] are related to cardiometabolic outcomes,” she said.

Potential confounders in the study include the fact that rates of overweight and obesity are higher among youths with gender dysphoria. This can in itself can increase the risk for other disorders, Dr. Valentine noted.

Furthermore, rates of mental health comorbidities are higher among youths with gender dysphoria. One consequence of this may be that they engage in less physical activity, she said.

Hormone therapy, health care disparities, or both could explain risk

In commenting on the study, Joshua D. Safer, MD, executive director of the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, the Mount Sinai Health System, New York, said that although similar cardiovascular effects are known to occur in transgender adults as well, they may or may not be hormone related. Other factors can increase the risk.

“With transgender adults, any differences in lipids or cardiac risk factors relative to cisgender people might be attributable either to hormone therapy or to health care disparities,” he said in an interview.

“The data are mixed. It may be that most differences relate to lack of access to care and to mistreatment by society,” he said. “Even studies that focus on hormones see a worsened situation for trans women versus trans men.”

Other recent research that shows potential cardiovascular effects among adult transgender men includes a study of more than 1,000 transgender men (born female) who received testosterone. That study, which was also presented at the ENDO meeting and was reported by this news organization, found an increased risk for high hematocrit levels, which could lead to a thrombotic event.

However, a study published in Pediatrics, which was also reported by this news organization, that included 611 transgender youths who had taken gender-affirming hormone therapy for more than a year found no increased risk for thrombosis, even in the presence of thrombosis risk factors, including obesity, tobacco use, and family history of thrombosis. However, the senior author of that study pointed out that the duration of follow-up in that study was relatively short, which may have been why they did not find an increased risk for thrombosis.

Dr. Safer noted that transgender youths and adults alike face a host of cultural factors that could play a role in increased cardiovascular risks.

“For adults, the major candidate explanations for worse BMI and cardiac risk factors are societal mistreatment, and for trans women specifically, progestins. For youth, the major candidate explanations are societal mistreatment and lack of access to athletics,” he said.

The authors and Dr. Safer disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA clears nonstimulant for ADHD in children aged 6 years and up

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the nonstimulant medication viloxazine extended-release capsules (Qelbree, Supernus Pharmaceuticals) for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 6-17 years, the company has announced.

Viloxazine (formerly SPN-812) is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Capsules may be swallowed whole or opened and the entire contents sprinkled onto applesauce, as needed.

The approval of viloxazine is supported by data from four phase 3 clinical trials involving more than 1,000 pediatric patients aged 6-17 years, the company said.

In one randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study that included more than 400 children, viloxazine reduced symptoms of ADHD as soon as 1 week after dosing and was well tolerated.

As reported by this news organization, the study was published last July in Clinical Therapeutics.

In addition to its fast onset of action, the fact that it was effective for both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive clusters of symptoms is “impressive,” study investigator Andrew Cutler, MD, clinical associate professor of psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y., said in an interview.

Also noteworthy was the improvement in measures of quality of life and function, “especially function in the areas of school, home life, family relations, and peer relationships, which can be really disrupted with ADHD,” Dr. Cutler said.

The prescribing label for viloxazine includes a boxed warning regarding the potential for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in some children with ADHD treated with the drug, especially within the first few months of treatment or when the dose is changed.

In clinical trials, higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior were reported in pediatric patients treated with viloxazine than in patients treated with placebo. Patients taking viloxazine should be closely monitored for any new or sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

Viloxazine has shown promise in a phase 3 trial involving adults with ADHD.

The company plans to submit a supplemental new drug application to the FDA for viloxazine in adults later this year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the nonstimulant medication viloxazine extended-release capsules (Qelbree, Supernus Pharmaceuticals) for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 6-17 years, the company has announced.

Viloxazine (formerly SPN-812) is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Capsules may be swallowed whole or opened and the entire contents sprinkled onto applesauce, as needed.

The approval of viloxazine is supported by data from four phase 3 clinical trials involving more than 1,000 pediatric patients aged 6-17 years, the company said.

In one randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study that included more than 400 children, viloxazine reduced symptoms of ADHD as soon as 1 week after dosing and was well tolerated.

As reported by this news organization, the study was published last July in Clinical Therapeutics.

In addition to its fast onset of action, the fact that it was effective for both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive clusters of symptoms is “impressive,” study investigator Andrew Cutler, MD, clinical associate professor of psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y., said in an interview.

Also noteworthy was the improvement in measures of quality of life and function, “especially function in the areas of school, home life, family relations, and peer relationships, which can be really disrupted with ADHD,” Dr. Cutler said.

The prescribing label for viloxazine includes a boxed warning regarding the potential for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in some children with ADHD treated with the drug, especially within the first few months of treatment or when the dose is changed.

In clinical trials, higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior were reported in pediatric patients treated with viloxazine than in patients treated with placebo. Patients taking viloxazine should be closely monitored for any new or sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

Viloxazine has shown promise in a phase 3 trial involving adults with ADHD.

The company plans to submit a supplemental new drug application to the FDA for viloxazine in adults later this year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the nonstimulant medication viloxazine extended-release capsules (Qelbree, Supernus Pharmaceuticals) for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 6-17 years, the company has announced.

Viloxazine (formerly SPN-812) is a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Capsules may be swallowed whole or opened and the entire contents sprinkled onto applesauce, as needed.

The approval of viloxazine is supported by data from four phase 3 clinical trials involving more than 1,000 pediatric patients aged 6-17 years, the company said.

In one randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study that included more than 400 children, viloxazine reduced symptoms of ADHD as soon as 1 week after dosing and was well tolerated.

As reported by this news organization, the study was published last July in Clinical Therapeutics.

In addition to its fast onset of action, the fact that it was effective for both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive clusters of symptoms is “impressive,” study investigator Andrew Cutler, MD, clinical associate professor of psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y., said in an interview.

Also noteworthy was the improvement in measures of quality of life and function, “especially function in the areas of school, home life, family relations, and peer relationships, which can be really disrupted with ADHD,” Dr. Cutler said.

The prescribing label for viloxazine includes a boxed warning regarding the potential for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in some children with ADHD treated with the drug, especially within the first few months of treatment or when the dose is changed.

In clinical trials, higher rates of suicidal thoughts and behavior were reported in pediatric patients treated with viloxazine than in patients treated with placebo. Patients taking viloxazine should be closely monitored for any new or sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

Viloxazine has shown promise in a phase 3 trial involving adults with ADHD.

The company plans to submit a supplemental new drug application to the FDA for viloxazine in adults later this year.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers stress importance of second COVID-19 vaccine dose for infliximab users

Patients being treated with infliximab had weakened immune responses to the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford/AstraZeneca) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccines, compared with patients on vedolizumab (Entyvio), although a very significant number of patients from both groups seroconverted after their second dose, according to a new U.K. study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“Antibody testing and adapted vaccine schedules should be considered to protect these at-risk patients,” Nicholas A. Kennedy, PhD, MBBS, of the University of Exeter (England) and colleagues wrote in a preprint published March 29 on MedRxiv.

Infliximab is an anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) monoclonal antibody that’s approved to treat adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis, whereas vedolizumab, a gut selective anti-integrin alpha4beta7 monoclonal antibody that is not associated with impaired systemic immune responses, is approved to treat Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in adults.

A previous study from Kennedy and colleagues revealed that IBD patients on infliximab showed a weakened COVID-19 antibody response compared with patients on vedolizumab. To determine if treatment with anti-TNF drugs impacted the efficacy of the first shot of these two-dose COVID-19 vaccines, the researchers used data from the CLARITY IBD study to assess 865 infliximab- and 428 vedolizumab-treated participants without evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection who had received uninterrupted biologic therapy since being recruited between Sept. 22 and Dec. 23, 2020.

In the 3-10 weeks after initial vaccination, geometric mean concentrations for SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike protein receptor-binding protein antibodies were lower in patients on infliximab, compared with patients on vedolizumab for both the Pfizer (6.0 U/mL [5.9] versus 28.8 U/mL [5.4], P < .0001) and AstraZeneca (4.7 U/mL [4.9] versus 13.8 U/mL [5.9]; P < .0001) vaccines. The researchers’ multivariable models reinforced those findings, with antibody concentrations lower in infliximab-treated patients for both the Pfizer (fold change, 0.29; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.40; P < .0001) and AstraZeneca (FC, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.30-0.51; P < .0001) vaccines.

After second doses of the two-dose Pfizer vaccine, 85% of patients on infliximab and 86% of patients on vedolizumab seroconverted (P = .68); similarly high seroconversion rates were seen in patients who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 prior to receiving either vaccine. Several patient characteristics were associated with lower antibody concentrations regardless of vaccine type: being 60 years or older, use of immunomodulators, having Crohn’s disease, and being a smoker. Alternatively, non-White ethnicity was associated with higher antibody concentrations.

Evidence has ‘unclear clinical significance’

“These data, which require peer review, do not change my opinion on the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients taking TNF inhibitors such as infliximab as monotherapy for the treatment of psoriatic disease,” Joel M. Gelfand MD, director of the psoriasis and phototherapy treatment center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“First, two peer-reviewed studies found good antibody response in patients on TNF inhibitors receiving COVID-19 vaccines (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220289; 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220272). Second, antibody responses were robust in the small cohort that received the second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. We already know that, for the two messenger RNA-based vaccines available under emergency use authorization in the U.S., a second dose is required for optimal efficacy. Thus, evidence of a reduced antibody response after just one dose is of unclear clinical significance. Third, antibody responses are only a surrogate marker, and a low antibody response doesn’t necessarily mean the patient will not be protected by the vaccine.”

Focus on the second dose of a two-dose regimen

“Tell me about the response in people who got both doses of a vaccine that you’re supposed to get both doses of,” Jeffrey Curtis, MD, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “The number of patients in that subset was small [n = 27] but in my opinion that’s the most clinically relevant analysis and the one that patients and clinicians want answered.”

He also emphasized the uncertainty around what ‘protection’ means in these early days of studying COVID-19 vaccine responses. “You can define seroprotection or seroconversion as some absolute level of an antibody response, but if you want to say ‘Mrs. Smith, your antibody level was X,’ on whatever arbitrary scale with whoever’s arbitrary lab test, nobody actually knows that Mrs. Smith is now protected from SARS-CoV-2, or how protected,” he said.

“What is not terribly controversial is: If you can’t detect antibodies, the vaccine didn’t ‘take,’ if you will. But if I tell you that the mean antibody level was X with one drug and then 2X with another drug, does that mean that you’re twice as protected? We don’t know that. I’m fearful that people are looking at these studies and thinking that more is better. It might be, but we don’t know that to be true.”

Debating the cause of weakened immune responses

“The biological plausibility of being on an anti-TNF affecting your immune reaction to a messenger RNA or even a replication-deficient viral vector vaccine doesn’t make sense,” David T. Rubin, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and chair of the National Scientific Advisory Committee of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, said in an interview.

“I’m sure immunologists may differ with me on this, but given what we have come to appreciate about these vaccine mechanisms, this finding doesn’t make intuitive sense. So we need to make sure that, when this happens, we look to the next studies and try to understand, was there any other confounder that may have resulted in these findings that was not adequately adjusted for or addressed in some other way?

“When you have a study of this size, you argue, ‘Because it’s so large, any effect that was seen must be real,’ ” he added. “Alternatively, to have a study of this size, by its very nature you are limited in being able to control for certain other factors or differences between the groups.”

That said, he commended the authors for their study and acknowledged the potential questions it raises about the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine. “If you only get one and you’re on infliximab, this study implies that maybe that’s not enough,” he said. “Despite the fact that Johnson & Johnson was approved as a single dose, it may be necessary to think about it as the first of two, or maybe it’s not the preferred vaccine in this group of patients.”

The study was supported by the Royal Devon and Exeter and Hull University Hospital Foundation NHS Trusts and unrestricted educational grants from Biogen (Switzerland), Celltrion Healthcare (South Korea), Galapagos NV (Belgium), and F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Switzerland). The authors acknowledged numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from various pharmaceutical companies.

Patients being treated with infliximab had weakened immune responses to the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford/AstraZeneca) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccines, compared with patients on vedolizumab (Entyvio), although a very significant number of patients from both groups seroconverted after their second dose, according to a new U.K. study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“Antibody testing and adapted vaccine schedules should be considered to protect these at-risk patients,” Nicholas A. Kennedy, PhD, MBBS, of the University of Exeter (England) and colleagues wrote in a preprint published March 29 on MedRxiv.

Infliximab is an anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) monoclonal antibody that’s approved to treat adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis, whereas vedolizumab, a gut selective anti-integrin alpha4beta7 monoclonal antibody that is not associated with impaired systemic immune responses, is approved to treat Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in adults.

A previous study from Kennedy and colleagues revealed that IBD patients on infliximab showed a weakened COVID-19 antibody response compared with patients on vedolizumab. To determine if treatment with anti-TNF drugs impacted the efficacy of the first shot of these two-dose COVID-19 vaccines, the researchers used data from the CLARITY IBD study to assess 865 infliximab- and 428 vedolizumab-treated participants without evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection who had received uninterrupted biologic therapy since being recruited between Sept. 22 and Dec. 23, 2020.

In the 3-10 weeks after initial vaccination, geometric mean concentrations for SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike protein receptor-binding protein antibodies were lower in patients on infliximab, compared with patients on vedolizumab for both the Pfizer (6.0 U/mL [5.9] versus 28.8 U/mL [5.4], P < .0001) and AstraZeneca (4.7 U/mL [4.9] versus 13.8 U/mL [5.9]; P < .0001) vaccines. The researchers’ multivariable models reinforced those findings, with antibody concentrations lower in infliximab-treated patients for both the Pfizer (fold change, 0.29; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.40; P < .0001) and AstraZeneca (FC, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.30-0.51; P < .0001) vaccines.

After second doses of the two-dose Pfizer vaccine, 85% of patients on infliximab and 86% of patients on vedolizumab seroconverted (P = .68); similarly high seroconversion rates were seen in patients who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 prior to receiving either vaccine. Several patient characteristics were associated with lower antibody concentrations regardless of vaccine type: being 60 years or older, use of immunomodulators, having Crohn’s disease, and being a smoker. Alternatively, non-White ethnicity was associated with higher antibody concentrations.

Evidence has ‘unclear clinical significance’

“These data, which require peer review, do not change my opinion on the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients taking TNF inhibitors such as infliximab as monotherapy for the treatment of psoriatic disease,” Joel M. Gelfand MD, director of the psoriasis and phototherapy treatment center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“First, two peer-reviewed studies found good antibody response in patients on TNF inhibitors receiving COVID-19 vaccines (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220289; 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220272). Second, antibody responses were robust in the small cohort that received the second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. We already know that, for the two messenger RNA-based vaccines available under emergency use authorization in the U.S., a second dose is required for optimal efficacy. Thus, evidence of a reduced antibody response after just one dose is of unclear clinical significance. Third, antibody responses are only a surrogate marker, and a low antibody response doesn’t necessarily mean the patient will not be protected by the vaccine.”

Focus on the second dose of a two-dose regimen

“Tell me about the response in people who got both doses of a vaccine that you’re supposed to get both doses of,” Jeffrey Curtis, MD, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “The number of patients in that subset was small [n = 27] but in my opinion that’s the most clinically relevant analysis and the one that patients and clinicians want answered.”

He also emphasized the uncertainty around what ‘protection’ means in these early days of studying COVID-19 vaccine responses. “You can define seroprotection or seroconversion as some absolute level of an antibody response, but if you want to say ‘Mrs. Smith, your antibody level was X,’ on whatever arbitrary scale with whoever’s arbitrary lab test, nobody actually knows that Mrs. Smith is now protected from SARS-CoV-2, or how protected,” he said.

“What is not terribly controversial is: If you can’t detect antibodies, the vaccine didn’t ‘take,’ if you will. But if I tell you that the mean antibody level was X with one drug and then 2X with another drug, does that mean that you’re twice as protected? We don’t know that. I’m fearful that people are looking at these studies and thinking that more is better. It might be, but we don’t know that to be true.”

Debating the cause of weakened immune responses

“The biological plausibility of being on an anti-TNF affecting your immune reaction to a messenger RNA or even a replication-deficient viral vector vaccine doesn’t make sense,” David T. Rubin, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and chair of the National Scientific Advisory Committee of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, said in an interview.

“I’m sure immunologists may differ with me on this, but given what we have come to appreciate about these vaccine mechanisms, this finding doesn’t make intuitive sense. So we need to make sure that, when this happens, we look to the next studies and try to understand, was there any other confounder that may have resulted in these findings that was not adequately adjusted for or addressed in some other way?

“When you have a study of this size, you argue, ‘Because it’s so large, any effect that was seen must be real,’ ” he added. “Alternatively, to have a study of this size, by its very nature you are limited in being able to control for certain other factors or differences between the groups.”

That said, he commended the authors for their study and acknowledged the potential questions it raises about the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine. “If you only get one and you’re on infliximab, this study implies that maybe that’s not enough,” he said. “Despite the fact that Johnson & Johnson was approved as a single dose, it may be necessary to think about it as the first of two, or maybe it’s not the preferred vaccine in this group of patients.”

The study was supported by the Royal Devon and Exeter and Hull University Hospital Foundation NHS Trusts and unrestricted educational grants from Biogen (Switzerland), Celltrion Healthcare (South Korea), Galapagos NV (Belgium), and F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Switzerland). The authors acknowledged numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from various pharmaceutical companies.

Patients being treated with infliximab had weakened immune responses to the first dose of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford/AstraZeneca) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) vaccines, compared with patients on vedolizumab (Entyvio), although a very significant number of patients from both groups seroconverted after their second dose, according to a new U.K. study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“Antibody testing and adapted vaccine schedules should be considered to protect these at-risk patients,” Nicholas A. Kennedy, PhD, MBBS, of the University of Exeter (England) and colleagues wrote in a preprint published March 29 on MedRxiv.

Infliximab is an anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) monoclonal antibody that’s approved to treat adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and plaque psoriasis, whereas vedolizumab, a gut selective anti-integrin alpha4beta7 monoclonal antibody that is not associated with impaired systemic immune responses, is approved to treat Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in adults.

A previous study from Kennedy and colleagues revealed that IBD patients on infliximab showed a weakened COVID-19 antibody response compared with patients on vedolizumab. To determine if treatment with anti-TNF drugs impacted the efficacy of the first shot of these two-dose COVID-19 vaccines, the researchers used data from the CLARITY IBD study to assess 865 infliximab- and 428 vedolizumab-treated participants without evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection who had received uninterrupted biologic therapy since being recruited between Sept. 22 and Dec. 23, 2020.

In the 3-10 weeks after initial vaccination, geometric mean concentrations for SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike protein receptor-binding protein antibodies were lower in patients on infliximab, compared with patients on vedolizumab for both the Pfizer (6.0 U/mL [5.9] versus 28.8 U/mL [5.4], P < .0001) and AstraZeneca (4.7 U/mL [4.9] versus 13.8 U/mL [5.9]; P < .0001) vaccines. The researchers’ multivariable models reinforced those findings, with antibody concentrations lower in infliximab-treated patients for both the Pfizer (fold change, 0.29; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.40; P < .0001) and AstraZeneca (FC, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.30-0.51; P < .0001) vaccines.

After second doses of the two-dose Pfizer vaccine, 85% of patients on infliximab and 86% of patients on vedolizumab seroconverted (P = .68); similarly high seroconversion rates were seen in patients who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 prior to receiving either vaccine. Several patient characteristics were associated with lower antibody concentrations regardless of vaccine type: being 60 years or older, use of immunomodulators, having Crohn’s disease, and being a smoker. Alternatively, non-White ethnicity was associated with higher antibody concentrations.

Evidence has ‘unclear clinical significance’

“These data, which require peer review, do not change my opinion on the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines in patients taking TNF inhibitors such as infliximab as monotherapy for the treatment of psoriatic disease,” Joel M. Gelfand MD, director of the psoriasis and phototherapy treatment center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“First, two peer-reviewed studies found good antibody response in patients on TNF inhibitors receiving COVID-19 vaccines (doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220289; 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220272). Second, antibody responses were robust in the small cohort that received the second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. We already know that, for the two messenger RNA-based vaccines available under emergency use authorization in the U.S., a second dose is required for optimal efficacy. Thus, evidence of a reduced antibody response after just one dose is of unclear clinical significance. Third, antibody responses are only a surrogate marker, and a low antibody response doesn’t necessarily mean the patient will not be protected by the vaccine.”

Focus on the second dose of a two-dose regimen

“Tell me about the response in people who got both doses of a vaccine that you’re supposed to get both doses of,” Jeffrey Curtis, MD, professor of medicine in the division of clinical immunology and rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in an interview. “The number of patients in that subset was small [n = 27] but in my opinion that’s the most clinically relevant analysis and the one that patients and clinicians want answered.”

He also emphasized the uncertainty around what ‘protection’ means in these early days of studying COVID-19 vaccine responses. “You can define seroprotection or seroconversion as some absolute level of an antibody response, but if you want to say ‘Mrs. Smith, your antibody level was X,’ on whatever arbitrary scale with whoever’s arbitrary lab test, nobody actually knows that Mrs. Smith is now protected from SARS-CoV-2, or how protected,” he said.

“What is not terribly controversial is: If you can’t detect antibodies, the vaccine didn’t ‘take,’ if you will. But if I tell you that the mean antibody level was X with one drug and then 2X with another drug, does that mean that you’re twice as protected? We don’t know that. I’m fearful that people are looking at these studies and thinking that more is better. It might be, but we don’t know that to be true.”

Debating the cause of weakened immune responses

“The biological plausibility of being on an anti-TNF affecting your immune reaction to a messenger RNA or even a replication-deficient viral vector vaccine doesn’t make sense,” David T. Rubin, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and chair of the National Scientific Advisory Committee of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, said in an interview.

“I’m sure immunologists may differ with me on this, but given what we have come to appreciate about these vaccine mechanisms, this finding doesn’t make intuitive sense. So we need to make sure that, when this happens, we look to the next studies and try to understand, was there any other confounder that may have resulted in these findings that was not adequately adjusted for or addressed in some other way?

“When you have a study of this size, you argue, ‘Because it’s so large, any effect that was seen must be real,’ ” he added. “Alternatively, to have a study of this size, by its very nature you are limited in being able to control for certain other factors or differences between the groups.”

That said, he commended the authors for their study and acknowledged the potential questions it raises about the single-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine. “If you only get one and you’re on infliximab, this study implies that maybe that’s not enough,” he said. “Despite the fact that Johnson & Johnson was approved as a single dose, it may be necessary to think about it as the first of two, or maybe it’s not the preferred vaccine in this group of patients.”

The study was supported by the Royal Devon and Exeter and Hull University Hospital Foundation NHS Trusts and unrestricted educational grants from Biogen (Switzerland), Celltrion Healthcare (South Korea), Galapagos NV (Belgium), and F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Switzerland). The authors acknowledged numerous potential conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM MEDRXIV

Hyperphagia, anxiety eased with carbetocin in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome

Children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) who received three daily, intranasal doses of carbetocin, an investigational, long-acting oxytocin analogue, had significant improvement in hyperphagia and anxiety during 8 weeks on treatment, compared with placebo in a multicenter, phase 3 trial with 119 patients.

The treatment also appeared safe during up to 56 additional weeks on active treatment, with no serious adverse effects nor “unexpected” events, and once completing the study about 95% of enrolled patients opted to remain on active treatment, Cheri L. Deal, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Based on “the significant results for the placebo-controlled period, as well as for those finishing the 56-week extension, we may well have a new armament for helping these kids and their families deal with the unrelenting hunger of patients with PWS as well as some of the behavioral symptoms,” Dr. Deal, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at the Sainte-Justine Mother-Child University of Montreal Hospital, said in an interview. No treatment currently has labeling for addressing the hyperphagia or anxiety that is characteristic and often problematic for children and adolescents with PWS, an autosomal dominant genetic disease with an incidence of about 1 in 15,000 births and an estimated U.S. prevalence of about 9,000 cases, or about 1 case for every 37,000 people.

‘Gorgeous’ safety

“The results looked pretty positive, and we’re encouraged by what appears to be a good safety profile, so overall I think the PWS community is very excited by the results and is very interested in getting access to this drug,” commented Theresa V. Strong, PhD, director of research programs for the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research in Walnut, Calif., a group not involved with the study. Currently, “we have no effective treatments for these difficult behaviors” of hyperphagia and anxiety. Surveys and studies run by the foundation have documented that hyperphagia and anxiety “were the two most important symptoms that families would like to see treated,” Dr. Strong added in an interview.

PWS “is complex and affects almost every aspect of the lives of affected people and their families. Any treatment that can chip away at some of the problems these patients have can be a huge benefit to the patients and their families,” said Jennifer L. Miller, MD, a professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and a coinvestigator on the study.

But the finding that carbetocin appeared to address, at least in part, this unmet need while compiling a safety record that Dr. Miller called “gorgeous” and “remarkable,” also came with a few limitations.

Fewer patients than planned, and muddled outcomes

The CARE-PWS trial aimed to enroll 175 patients, but fell short once the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Plus the trial had two prespecified primary endpoints – improvements in a measure of hyperphagia, and in a measure of obsessive and compulsive behaviors – specifically in the 40 patients who received the higher of the two dosages studied, 9.6 mg t.i.d. intranasally. Neither endpoint showed significant improvement among the patients on this dosage, compared with the 40 patients who received placebo, although both outcomes trended in the right direction in the actively treated patients.

The study’s positive results came in a secondary treatment group, 39 patients who received 3.2 mg t.i.d., also intranasally. This subgroup had significant benefit, compared with placebo, for reducing hyperphagia symptoms as measured on the Hyperphagia Questionnaire for Clinical Trials (HQ-CT) Total Score. After the first 8 weeks on treatment, patients on the lower carbetocin dosage had an average reduction in their HQ-CT score of greater than 5 points, more than double the reduction seen among control patients who received placebo.

Those on the 3.2-mg t.i.d. dosage also showed significant improvements, compared with placebo, for anxiety, measured by the PWS Anxiety and Distress Questionnaire Total Score, as well as on measures of clinical global impression of severity, and of clinical global impression of change. Like the higher-dosage patients the lower-dosage subgroup did not show a significant difference compared with placebo for the other primary endpoint, change in obsessive and compulsive behaviors as measured by the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Total Score, although also like the higher dosage the effect from the lower dosage trended toward benefit.