User login

Faster enteral feeding does not up adverse outcomes risk in preterm infants

including moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability and necrotizing enterocolitis, according to recent research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although some data have shown rapidly increasing the speed of enteral-feeding volumes for preterm infants can raise the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, these data are from observational case-control and uncontrolled studies, said Jon Dorling, MD, of the division of neonatal–perinatal medicine at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., and colleagues in their study.

Dr. Doring and colleagues randomized 2,804 infants who were either very preterm or with a very low birth weight to receive daily milk increments at different volumes until the infants reached full feeding volume. Infants in the faster-increment group received daily milk at 30 mL per kg of body weight, while the slower-increment group received 18 mL per kg of body weight each day. The researchers analyzed infant survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability, with secondary outcomes of sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and cerebral palsy at 24 months.

Overall, the researchers had information on the primary outcome for 87.4% of infants in the faster-increment group and 88.7% of infants in the slower-increment group. They found that 65.5% of infants in the faster-increment group and 68.1% of infants in the slower-increment group achieved an outcome of survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months (adjusted risk ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.92-1.01; P equals .16). Secondary outcomes showed similar rates of adverse outcomes in the two groups, with 29.8% of infants in the faster-increment group and 31.1% of infants in the slower-increment group developing late-onset sepsis (aRR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07). Infants in the faster-increment group also had a similar rate of necrotizing enterocolitis (5.0%), compared with infants in the slower-increment group (5.6%) (aRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.68-1.16). Motor impairment was higher among infants in the faster-increment group (7.5%), compared with the slow-increment group (5.0%).

In the faster-increment group, the median number of days to reach full milk-feeding volumes was 7 vs. 10 in the slower-increment group.

“Although these feeding outcomes seem to favor faster increments, the risk of moderate or severe motor impairment was unexpectedly higher in the faster-increment group than in the slower-increment group,” the researchers said. “This observation is unexplained, and there were not more cases of late-onset sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis in the faster-increment group.”

It is possible that it is a chance finding, since it was one of multiple secondary outcomes assessed, but biologically plausible explanations include increased cardiorespiratory events from pressure on the diaphragm or inability to absorb enteral nutrition,” they added.

The researchers said one potential limitation of the study was that it was unblinded.

This study was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme of the National Institute for Health Research. The authors reported various relationships with Baxter Bioscience, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Danone Early Life Nutrition, Fresenius Kabi USA LLC, National Institute for Health Research, Nestle Nutrition Institute, Nutrina, Medical Research Council, and Prolacta Biosciences in the form of consultancies, grants, travel reimbursement, board memberships, and editorial board appointments.

SOURCE: Doring J et al. N Eng J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816654.

including moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability and necrotizing enterocolitis, according to recent research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although some data have shown rapidly increasing the speed of enteral-feeding volumes for preterm infants can raise the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, these data are from observational case-control and uncontrolled studies, said Jon Dorling, MD, of the division of neonatal–perinatal medicine at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., and colleagues in their study.

Dr. Doring and colleagues randomized 2,804 infants who were either very preterm or with a very low birth weight to receive daily milk increments at different volumes until the infants reached full feeding volume. Infants in the faster-increment group received daily milk at 30 mL per kg of body weight, while the slower-increment group received 18 mL per kg of body weight each day. The researchers analyzed infant survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability, with secondary outcomes of sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and cerebral palsy at 24 months.

Overall, the researchers had information on the primary outcome for 87.4% of infants in the faster-increment group and 88.7% of infants in the slower-increment group. They found that 65.5% of infants in the faster-increment group and 68.1% of infants in the slower-increment group achieved an outcome of survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months (adjusted risk ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.92-1.01; P equals .16). Secondary outcomes showed similar rates of adverse outcomes in the two groups, with 29.8% of infants in the faster-increment group and 31.1% of infants in the slower-increment group developing late-onset sepsis (aRR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07). Infants in the faster-increment group also had a similar rate of necrotizing enterocolitis (5.0%), compared with infants in the slower-increment group (5.6%) (aRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.68-1.16). Motor impairment was higher among infants in the faster-increment group (7.5%), compared with the slow-increment group (5.0%).

In the faster-increment group, the median number of days to reach full milk-feeding volumes was 7 vs. 10 in the slower-increment group.

“Although these feeding outcomes seem to favor faster increments, the risk of moderate or severe motor impairment was unexpectedly higher in the faster-increment group than in the slower-increment group,” the researchers said. “This observation is unexplained, and there were not more cases of late-onset sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis in the faster-increment group.”

It is possible that it is a chance finding, since it was one of multiple secondary outcomes assessed, but biologically plausible explanations include increased cardiorespiratory events from pressure on the diaphragm or inability to absorb enteral nutrition,” they added.

The researchers said one potential limitation of the study was that it was unblinded.

This study was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme of the National Institute for Health Research. The authors reported various relationships with Baxter Bioscience, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Danone Early Life Nutrition, Fresenius Kabi USA LLC, National Institute for Health Research, Nestle Nutrition Institute, Nutrina, Medical Research Council, and Prolacta Biosciences in the form of consultancies, grants, travel reimbursement, board memberships, and editorial board appointments.

SOURCE: Doring J et al. N Eng J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816654.

including moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability and necrotizing enterocolitis, according to recent research published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Although some data have shown rapidly increasing the speed of enteral-feeding volumes for preterm infants can raise the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, these data are from observational case-control and uncontrolled studies, said Jon Dorling, MD, of the division of neonatal–perinatal medicine at Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., and colleagues in their study.

Dr. Doring and colleagues randomized 2,804 infants who were either very preterm or with a very low birth weight to receive daily milk increments at different volumes until the infants reached full feeding volume. Infants in the faster-increment group received daily milk at 30 mL per kg of body weight, while the slower-increment group received 18 mL per kg of body weight each day. The researchers analyzed infant survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability, with secondary outcomes of sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis, and cerebral palsy at 24 months.

Overall, the researchers had information on the primary outcome for 87.4% of infants in the faster-increment group and 88.7% of infants in the slower-increment group. They found that 65.5% of infants in the faster-increment group and 68.1% of infants in the slower-increment group achieved an outcome of survival without moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability at 24 months (adjusted risk ratio, 0.96; 95% confidence interval, 0.92-1.01; P equals .16). Secondary outcomes showed similar rates of adverse outcomes in the two groups, with 29.8% of infants in the faster-increment group and 31.1% of infants in the slower-increment group developing late-onset sepsis (aRR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07). Infants in the faster-increment group also had a similar rate of necrotizing enterocolitis (5.0%), compared with infants in the slower-increment group (5.6%) (aRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.68-1.16). Motor impairment was higher among infants in the faster-increment group (7.5%), compared with the slow-increment group (5.0%).

In the faster-increment group, the median number of days to reach full milk-feeding volumes was 7 vs. 10 in the slower-increment group.

“Although these feeding outcomes seem to favor faster increments, the risk of moderate or severe motor impairment was unexpectedly higher in the faster-increment group than in the slower-increment group,” the researchers said. “This observation is unexplained, and there were not more cases of late-onset sepsis or necrotizing enterocolitis in the faster-increment group.”

It is possible that it is a chance finding, since it was one of multiple secondary outcomes assessed, but biologically plausible explanations include increased cardiorespiratory events from pressure on the diaphragm or inability to absorb enteral nutrition,” they added.

The researchers said one potential limitation of the study was that it was unblinded.

This study was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme of the National Institute for Health Research. The authors reported various relationships with Baxter Bioscience, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Danone Early Life Nutrition, Fresenius Kabi USA LLC, National Institute for Health Research, Nestle Nutrition Institute, Nutrina, Medical Research Council, and Prolacta Biosciences in the form of consultancies, grants, travel reimbursement, board memberships, and editorial board appointments.

SOURCE: Doring J et al. N Eng J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816654.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Congenital syphilis continues to rise at an alarming rate

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

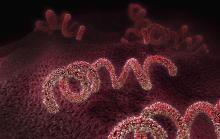

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One-year data support dupilumab’s efficacy and safety in adolescents with AD

A study of and continued evidence of efficacy for up to 52 weeks, reported the authors of the study, published online Oct. 9 in the British Journal of Dermatology.

The phase 2a open-label, ascending-dose cohort study of dupilumab in 40 adolescents with moderate to severe AD was followed by a 48-week phase 3 open-label extension study in 36 of those participants. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13.

In the phase 2a study, participants were treated with a single subcutaneous dose of dupilumab – either 2 mg/kg or 4 mg/kg – and had 8 weeks of pharmacokinetic sampling. They subsequently received that same dose weekly for 4 weeks, with an 8-week-long safety follow-up period. Those who participated in the open-label extension continued their weekly dose to a maximum of 300 mg. per kg

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (a primary endpoint) seen in both the phase 2a and phase 3 studies were nasopharyngitis and exacerbation of AD – in the phase 2a study, exacerbations were seen in the period when patients weren’t taking the treatment. In the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, the incidence of skin infections was 29% and 42%, respectively, and the incidence of injection site reactions – which were mostly mild – were 18% and 11%, respectively. Researchers also noted conjunctivitis in 18% and 16% of the patients in the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, respectively, but none of the cases were considered serious and all resolved over the course of the study. In the phase 2a study, 50% of patients on the 2-mg/kg dose and 65% of those on the 4-mg/kg dose experienced an adverse event, while in the open-label extension all reported at least one adverse event.

There was one case of suicidal behavior and one case of systemic or severe hypersensitivity reported in the 2-mg/kg groups, both of which were considered adverse events of special interest. There were no deaths.

However none of the serious adverse events – which included infected AD, palpitations, patent ductus arteriosus, and food allergy – were linked to the study treatment, and no adverse events led to study discontinuation, the authors reported.

By week 12, 70% of participants in the 2-mg/kg group and 75% in the 4-mg/kg group had achieved a 50% or greater improvement in their Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores, which was a secondary outcome. By week 52, that had increased to 100% and 89% respectively.

More than half the patients (55%) in the 2-mg/kg group, and 40% of those in the 4-mg/kg group achieved a 75% or more improvement in their EASI scores by week 12, which increased to 88% and 78%, respectively, by week 52 in the open label phase.

“The results from these studies support use of dupilumab for the long-term management of moderate to severe AD in adolescents,” wrote Michael J. Cork, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Sheffield, England, and coauthors. No new safety signals were identified, “compared with the known safety profile of dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe AD,” and “the PK profile was characterized by nonlinear, target-mediated kinetics, consistent with the profile in adults with moderate to severe AD,” they added.

Dupilumab was approved in the United States in March 2019 for adolescents with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.

The study was sponsored by dupilumab manufacturers Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which market dupilumab as Dupixent in the United States. Dr. Cork disclosures included those related to Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron; other authors included employees of the companies.

SOURCE: Cork M et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18476.

A study of and continued evidence of efficacy for up to 52 weeks, reported the authors of the study, published online Oct. 9 in the British Journal of Dermatology.

The phase 2a open-label, ascending-dose cohort study of dupilumab in 40 adolescents with moderate to severe AD was followed by a 48-week phase 3 open-label extension study in 36 of those participants. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13.

In the phase 2a study, participants were treated with a single subcutaneous dose of dupilumab – either 2 mg/kg or 4 mg/kg – and had 8 weeks of pharmacokinetic sampling. They subsequently received that same dose weekly for 4 weeks, with an 8-week-long safety follow-up period. Those who participated in the open-label extension continued their weekly dose to a maximum of 300 mg. per kg

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (a primary endpoint) seen in both the phase 2a and phase 3 studies were nasopharyngitis and exacerbation of AD – in the phase 2a study, exacerbations were seen in the period when patients weren’t taking the treatment. In the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, the incidence of skin infections was 29% and 42%, respectively, and the incidence of injection site reactions – which were mostly mild – were 18% and 11%, respectively. Researchers also noted conjunctivitis in 18% and 16% of the patients in the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, respectively, but none of the cases were considered serious and all resolved over the course of the study. In the phase 2a study, 50% of patients on the 2-mg/kg dose and 65% of those on the 4-mg/kg dose experienced an adverse event, while in the open-label extension all reported at least one adverse event.

There was one case of suicidal behavior and one case of systemic or severe hypersensitivity reported in the 2-mg/kg groups, both of which were considered adverse events of special interest. There were no deaths.

However none of the serious adverse events – which included infected AD, palpitations, patent ductus arteriosus, and food allergy – were linked to the study treatment, and no adverse events led to study discontinuation, the authors reported.

By week 12, 70% of participants in the 2-mg/kg group and 75% in the 4-mg/kg group had achieved a 50% or greater improvement in their Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores, which was a secondary outcome. By week 52, that had increased to 100% and 89% respectively.

More than half the patients (55%) in the 2-mg/kg group, and 40% of those in the 4-mg/kg group achieved a 75% or more improvement in their EASI scores by week 12, which increased to 88% and 78%, respectively, by week 52 in the open label phase.

“The results from these studies support use of dupilumab for the long-term management of moderate to severe AD in adolescents,” wrote Michael J. Cork, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Sheffield, England, and coauthors. No new safety signals were identified, “compared with the known safety profile of dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe AD,” and “the PK profile was characterized by nonlinear, target-mediated kinetics, consistent with the profile in adults with moderate to severe AD,” they added.

Dupilumab was approved in the United States in March 2019 for adolescents with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.

The study was sponsored by dupilumab manufacturers Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which market dupilumab as Dupixent in the United States. Dr. Cork disclosures included those related to Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron; other authors included employees of the companies.

SOURCE: Cork M et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18476.

A study of and continued evidence of efficacy for up to 52 weeks, reported the authors of the study, published online Oct. 9 in the British Journal of Dermatology.

The phase 2a open-label, ascending-dose cohort study of dupilumab in 40 adolescents with moderate to severe AD was followed by a 48-week phase 3 open-label extension study in 36 of those participants. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13.

In the phase 2a study, participants were treated with a single subcutaneous dose of dupilumab – either 2 mg/kg or 4 mg/kg – and had 8 weeks of pharmacokinetic sampling. They subsequently received that same dose weekly for 4 weeks, with an 8-week-long safety follow-up period. Those who participated in the open-label extension continued their weekly dose to a maximum of 300 mg. per kg

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (a primary endpoint) seen in both the phase 2a and phase 3 studies were nasopharyngitis and exacerbation of AD – in the phase 2a study, exacerbations were seen in the period when patients weren’t taking the treatment. In the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, the incidence of skin infections was 29% and 42%, respectively, and the incidence of injection site reactions – which were mostly mild – were 18% and 11%, respectively. Researchers also noted conjunctivitis in 18% and 16% of the patients in the 2-mg and 4-mg groups, respectively, but none of the cases were considered serious and all resolved over the course of the study. In the phase 2a study, 50% of patients on the 2-mg/kg dose and 65% of those on the 4-mg/kg dose experienced an adverse event, while in the open-label extension all reported at least one adverse event.

There was one case of suicidal behavior and one case of systemic or severe hypersensitivity reported in the 2-mg/kg groups, both of which were considered adverse events of special interest. There were no deaths.

However none of the serious adverse events – which included infected AD, palpitations, patent ductus arteriosus, and food allergy – were linked to the study treatment, and no adverse events led to study discontinuation, the authors reported.

By week 12, 70% of participants in the 2-mg/kg group and 75% in the 4-mg/kg group had achieved a 50% or greater improvement in their Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) scores, which was a secondary outcome. By week 52, that had increased to 100% and 89% respectively.

More than half the patients (55%) in the 2-mg/kg group, and 40% of those in the 4-mg/kg group achieved a 75% or more improvement in their EASI scores by week 12, which increased to 88% and 78%, respectively, by week 52 in the open label phase.

“The results from these studies support use of dupilumab for the long-term management of moderate to severe AD in adolescents,” wrote Michael J. Cork, MD, professor of dermatology, University of Sheffield, England, and coauthors. No new safety signals were identified, “compared with the known safety profile of dupilumab in adults with moderate to severe AD,” and “the PK profile was characterized by nonlinear, target-mediated kinetics, consistent with the profile in adults with moderate to severe AD,” they added.

Dupilumab was approved in the United States in March 2019 for adolescents with moderate to severe AD whose disease is not adequately controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.

The study was sponsored by dupilumab manufacturers Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, which market dupilumab as Dupixent in the United States. Dr. Cork disclosures included those related to Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron; other authors included employees of the companies.

SOURCE: Cork M et al. Br J Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18476.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Dysregulated sleep is common in children with eosinophilic esophagitis

, Rasintra Siriwat, MD, and colleagues have ascertained.

Children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) also were found to have a high prevalence of atopic diseases, including allergic rhinitis and eczema – findings that could be driving the breathing problems, said Dr. Siriwat, a neurology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthors.

The retrospective study comprised 81 children with a diagnosis of EoE who were referred to sleep clinics. In this group, 46 of the children had active EoE (having gastrointestinal symptoms, including feeding difficulties, dysphagia, reflux, nausea/vomiting, or epigastric pain at presentation). The other 35 had an EoE diagnosis but no symptoms on presentation and were categorized as having inactive EoE. Most were male (71.6%) and white (92.5%). The mean age in the cohort was 10 years and the mean body mass index for all subjects was 22 kg/m2. A control group of 192 children without an EoE diagnosis who had overnight polysomnography were included in the analysis.

Allergic-type comorbidities were common among those with active EoE, including allergic rhinitis (55.5%), food allergy (39.5%), and eczema (26%). In addition, a quarter had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 22% an autism spectrum disorder, 21% a neurological disease, and 29% a psychiatric disorder.

Several sleep complaints were common in the entire EoE cohort, including snoring (76.5 %), restless sleep (66.6%), legs jerking or leg discomfort (43.2%), and daytime sleepiness (58%).

All children underwent an overnight polysomnography. Compared with controls, the children with EoE had significantly higher non-REM2 sleep, significantly lower non-REM3 sleep, lower REM, increased periodic leg movement disorder, and increased arousal index.

“Of note, we found a much higher percentage of [periodic leg movement disorder] in active EoE compared to inactive EoE,” the authors said.

The most common sleep diagnosis for the children with EoE was sleep-disordered breathing. Of 62 children with EoE and sleep disordered breathing, 37% had obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Two patients had central sleep apnea and five had nocturnal hypoventilation. Children with EoE also reported parasomnia symptoms such as sleep talking (35.8%), sleepwalking (16%), bruxism (23.4%), night terrors (28.4%), and nocturnal enuresis (21.2%).

Of the 59 children with leg movement, 20 had periodic limb movement disorder and 5 were diagnosed with restless leg syndrome. Two were diagnosed with narcolepsy and three with hypersomnia. Four children had a circadian rhythm disorder.

“Notably, the majority of children with EoE had symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing, and more than one-third of total subjects were diagnosed with OSA,” the authors noted. “However, most of them were mild-moderate OSA. It should be noted that the prevalence of OSA in the pediatric population is 1%-5% mostly between the ages of 2-8 years, while the mean age of our subjects was 10 years old. The high prevalence of mild-moderate OSA in the EoE population might be explained by the relationship between EoE and atopic disease.”

Dr. Siriwat had no financial disclosures. The study was supported by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Fund.

SOURCE: Siriwat R et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.08.018.

, Rasintra Siriwat, MD, and colleagues have ascertained.

Children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) also were found to have a high prevalence of atopic diseases, including allergic rhinitis and eczema – findings that could be driving the breathing problems, said Dr. Siriwat, a neurology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthors.

The retrospective study comprised 81 children with a diagnosis of EoE who were referred to sleep clinics. In this group, 46 of the children had active EoE (having gastrointestinal symptoms, including feeding difficulties, dysphagia, reflux, nausea/vomiting, or epigastric pain at presentation). The other 35 had an EoE diagnosis but no symptoms on presentation and were categorized as having inactive EoE. Most were male (71.6%) and white (92.5%). The mean age in the cohort was 10 years and the mean body mass index for all subjects was 22 kg/m2. A control group of 192 children without an EoE diagnosis who had overnight polysomnography were included in the analysis.

Allergic-type comorbidities were common among those with active EoE, including allergic rhinitis (55.5%), food allergy (39.5%), and eczema (26%). In addition, a quarter had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 22% an autism spectrum disorder, 21% a neurological disease, and 29% a psychiatric disorder.

Several sleep complaints were common in the entire EoE cohort, including snoring (76.5 %), restless sleep (66.6%), legs jerking or leg discomfort (43.2%), and daytime sleepiness (58%).

All children underwent an overnight polysomnography. Compared with controls, the children with EoE had significantly higher non-REM2 sleep, significantly lower non-REM3 sleep, lower REM, increased periodic leg movement disorder, and increased arousal index.

“Of note, we found a much higher percentage of [periodic leg movement disorder] in active EoE compared to inactive EoE,” the authors said.

The most common sleep diagnosis for the children with EoE was sleep-disordered breathing. Of 62 children with EoE and sleep disordered breathing, 37% had obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Two patients had central sleep apnea and five had nocturnal hypoventilation. Children with EoE also reported parasomnia symptoms such as sleep talking (35.8%), sleepwalking (16%), bruxism (23.4%), night terrors (28.4%), and nocturnal enuresis (21.2%).

Of the 59 children with leg movement, 20 had periodic limb movement disorder and 5 were diagnosed with restless leg syndrome. Two were diagnosed with narcolepsy and three with hypersomnia. Four children had a circadian rhythm disorder.

“Notably, the majority of children with EoE had symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing, and more than one-third of total subjects were diagnosed with OSA,” the authors noted. “However, most of them were mild-moderate OSA. It should be noted that the prevalence of OSA in the pediatric population is 1%-5% mostly between the ages of 2-8 years, while the mean age of our subjects was 10 years old. The high prevalence of mild-moderate OSA in the EoE population might be explained by the relationship between EoE and atopic disease.”

Dr. Siriwat had no financial disclosures. The study was supported by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Fund.

SOURCE: Siriwat R et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.08.018.

, Rasintra Siriwat, MD, and colleagues have ascertained.

Children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) also were found to have a high prevalence of atopic diseases, including allergic rhinitis and eczema – findings that could be driving the breathing problems, said Dr. Siriwat, a neurology fellow at the Cleveland Clinic, and coauthors.

The retrospective study comprised 81 children with a diagnosis of EoE who were referred to sleep clinics. In this group, 46 of the children had active EoE (having gastrointestinal symptoms, including feeding difficulties, dysphagia, reflux, nausea/vomiting, or epigastric pain at presentation). The other 35 had an EoE diagnosis but no symptoms on presentation and were categorized as having inactive EoE. Most were male (71.6%) and white (92.5%). The mean age in the cohort was 10 years and the mean body mass index for all subjects was 22 kg/m2. A control group of 192 children without an EoE diagnosis who had overnight polysomnography were included in the analysis.

Allergic-type comorbidities were common among those with active EoE, including allergic rhinitis (55.5%), food allergy (39.5%), and eczema (26%). In addition, a quarter had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 22% an autism spectrum disorder, 21% a neurological disease, and 29% a psychiatric disorder.

Several sleep complaints were common in the entire EoE cohort, including snoring (76.5 %), restless sleep (66.6%), legs jerking or leg discomfort (43.2%), and daytime sleepiness (58%).

All children underwent an overnight polysomnography. Compared with controls, the children with EoE had significantly higher non-REM2 sleep, significantly lower non-REM3 sleep, lower REM, increased periodic leg movement disorder, and increased arousal index.

“Of note, we found a much higher percentage of [periodic leg movement disorder] in active EoE compared to inactive EoE,” the authors said.

The most common sleep diagnosis for the children with EoE was sleep-disordered breathing. Of 62 children with EoE and sleep disordered breathing, 37% had obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Two patients had central sleep apnea and five had nocturnal hypoventilation. Children with EoE also reported parasomnia symptoms such as sleep talking (35.8%), sleepwalking (16%), bruxism (23.4%), night terrors (28.4%), and nocturnal enuresis (21.2%).

Of the 59 children with leg movement, 20 had periodic limb movement disorder and 5 were diagnosed with restless leg syndrome. Two were diagnosed with narcolepsy and three with hypersomnia. Four children had a circadian rhythm disorder.

“Notably, the majority of children with EoE had symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing, and more than one-third of total subjects were diagnosed with OSA,” the authors noted. “However, most of them were mild-moderate OSA. It should be noted that the prevalence of OSA in the pediatric population is 1%-5% mostly between the ages of 2-8 years, while the mean age of our subjects was 10 years old. The high prevalence of mild-moderate OSA in the EoE population might be explained by the relationship between EoE and atopic disease.”

Dr. Siriwat had no financial disclosures. The study was supported by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Fund.

SOURCE: Siriwat R et al. Sleep Med. 2019 Sep 11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.08.018.

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

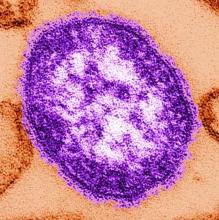

Interventions significantly improve NICU immunization rates

according to a study in Pediatrics.

Investigators led by Raymond C. Stetson, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., identified three root causes of underimmunization in a NICU at Mayo Clinic: providers’ lack of knowledge about recommended immunization schedules; immunizations not being ordered when they were due; and parental hesitancy toward vaccination. They addressed these causes with the following five phases of intervention: an intranet resource educating providers about vaccine schedules and dosing intervals; a spreadsheet-based checklist to track and flag immunization status; an intranet resource aimed at discussion with vaccine-hesitant parents; education about safety in providing immunization and review of material from the first three interventions; and education about documentation, including parental consent.

Over the project period, 1,242 infants were discharged or transferred from the NICU. The study included a 6-month “improve phase,” during which interventions were implemented, and a “control phase,” during which the ongoing effects after implementation were observed. At baseline, the rate of fully immunized infants in the NICU was only 56% by time of discharge or transfer, but during the combined improve and control phases, it was 93% with a P value of less than .001.

One of the limitations of the study is that the first three interventions were introduced simultaneously, which makes it hard to determine how much effect each might have had.

“Infants treated in NICUs represent a vulnerable population with the potential for high morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable infections,” the investigators wrote. “Our [quality improvement] effort, and others, demonstrate that this population is at risk for underimmunization and that immunization rates can be improved with a small number of interventions. Additionally, we were able to significantly decrease the number of days that immunizations were delayed compared to the routine infant vaccination schedule.”

There was no external funding for the study. One of the coauthors is on safety committees of vaccine studies for Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stetson R et al. Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0337.

according to a study in Pediatrics.

Investigators led by Raymond C. Stetson, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., identified three root causes of underimmunization in a NICU at Mayo Clinic: providers’ lack of knowledge about recommended immunization schedules; immunizations not being ordered when they were due; and parental hesitancy toward vaccination. They addressed these causes with the following five phases of intervention: an intranet resource educating providers about vaccine schedules and dosing intervals; a spreadsheet-based checklist to track and flag immunization status; an intranet resource aimed at discussion with vaccine-hesitant parents; education about safety in providing immunization and review of material from the first three interventions; and education about documentation, including parental consent.

Over the project period, 1,242 infants were discharged or transferred from the NICU. The study included a 6-month “improve phase,” during which interventions were implemented, and a “control phase,” during which the ongoing effects after implementation were observed. At baseline, the rate of fully immunized infants in the NICU was only 56% by time of discharge or transfer, but during the combined improve and control phases, it was 93% with a P value of less than .001.

One of the limitations of the study is that the first three interventions were introduced simultaneously, which makes it hard to determine how much effect each might have had.

“Infants treated in NICUs represent a vulnerable population with the potential for high morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable infections,” the investigators wrote. “Our [quality improvement] effort, and others, demonstrate that this population is at risk for underimmunization and that immunization rates can be improved with a small number of interventions. Additionally, we were able to significantly decrease the number of days that immunizations were delayed compared to the routine infant vaccination schedule.”

There was no external funding for the study. One of the coauthors is on safety committees of vaccine studies for Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stetson R et al. Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0337.

according to a study in Pediatrics.

Investigators led by Raymond C. Stetson, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., identified three root causes of underimmunization in a NICU at Mayo Clinic: providers’ lack of knowledge about recommended immunization schedules; immunizations not being ordered when they were due; and parental hesitancy toward vaccination. They addressed these causes with the following five phases of intervention: an intranet resource educating providers about vaccine schedules and dosing intervals; a spreadsheet-based checklist to track and flag immunization status; an intranet resource aimed at discussion with vaccine-hesitant parents; education about safety in providing immunization and review of material from the first three interventions; and education about documentation, including parental consent.

Over the project period, 1,242 infants were discharged or transferred from the NICU. The study included a 6-month “improve phase,” during which interventions were implemented, and a “control phase,” during which the ongoing effects after implementation were observed. At baseline, the rate of fully immunized infants in the NICU was only 56% by time of discharge or transfer, but during the combined improve and control phases, it was 93% with a P value of less than .001.

One of the limitations of the study is that the first three interventions were introduced simultaneously, which makes it hard to determine how much effect each might have had.

“Infants treated in NICUs represent a vulnerable population with the potential for high morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable infections,” the investigators wrote. “Our [quality improvement] effort, and others, demonstrate that this population is at risk for underimmunization and that immunization rates can be improved with a small number of interventions. Additionally, we were able to significantly decrease the number of days that immunizations were delayed compared to the routine infant vaccination schedule.”

There was no external funding for the study. One of the coauthors is on safety committees of vaccine studies for Merck. The other authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stetson R et al. Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0337.

FROM PEDIATRICS

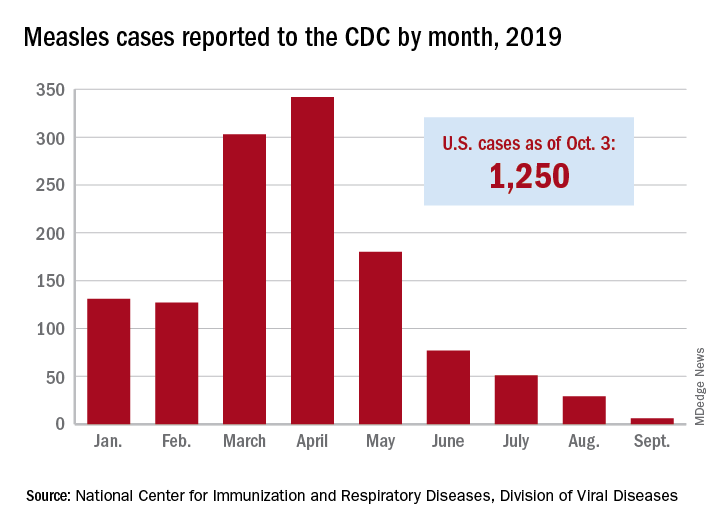

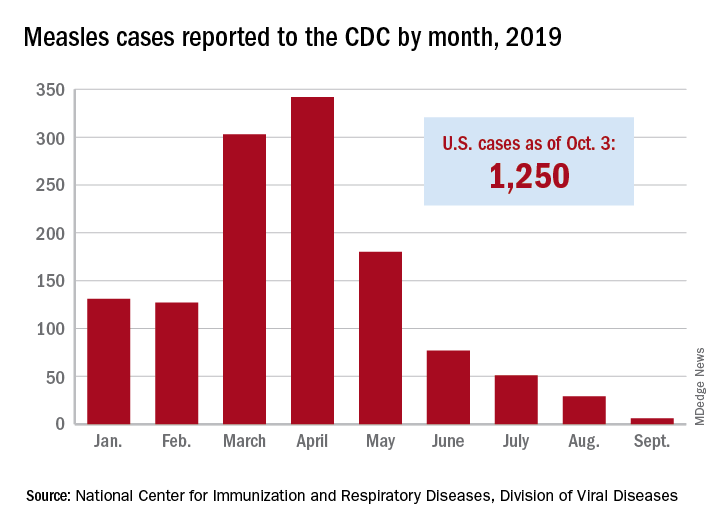

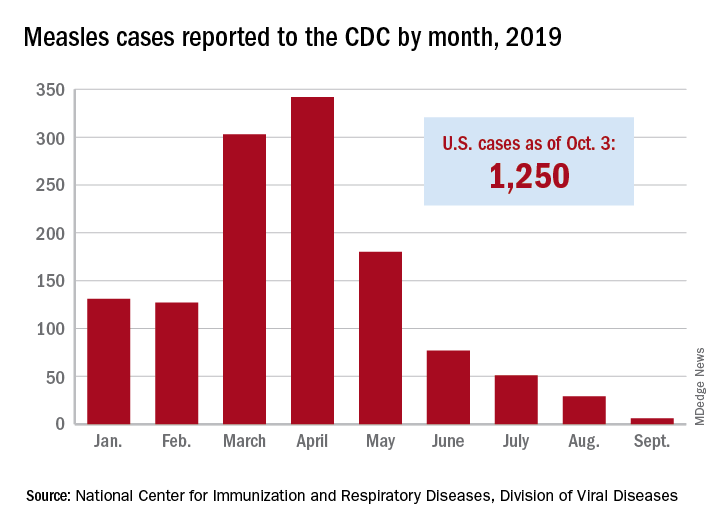

New York declares end to 2018 measles outbreak

New York State has reported the end of all active measles cases related to the initial outbreak in 2018, but the state is now responding to new, unrelated cases in four counties, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases – two in Nassau County and one each in Monroe, Putnam, and Rockland counties – are “related to measles exposures from international travel but not affiliated with the 2018 outbreak,” the New York State Department of Health said in a written statement. Officials in Rockland County had declared its 2018 measles outbreak, which involved 312 cases in 2018 and 2019, over on Sept. 25.

. Of those cases, 1,163 (93%) were associated with 22 outbreaks, with the two largest occurring in New York City and Rockland County. “These two almost year-long outbreaks placed the United States at risk for losing measles elimination status,” the CDC said in a separate report, but “robust responses … ended transmission before the 1-year mark.”

New York State has reported the end of all active measles cases related to the initial outbreak in 2018, but the state is now responding to new, unrelated cases in four counties, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases – two in Nassau County and one each in Monroe, Putnam, and Rockland counties – are “related to measles exposures from international travel but not affiliated with the 2018 outbreak,” the New York State Department of Health said in a written statement. Officials in Rockland County had declared its 2018 measles outbreak, which involved 312 cases in 2018 and 2019, over on Sept. 25.

. Of those cases, 1,163 (93%) were associated with 22 outbreaks, with the two largest occurring in New York City and Rockland County. “These two almost year-long outbreaks placed the United States at risk for losing measles elimination status,” the CDC said in a separate report, but “robust responses … ended transmission before the 1-year mark.”

New York State has reported the end of all active measles cases related to the initial outbreak in 2018, but the state is now responding to new, unrelated cases in four counties, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases – two in Nassau County and one each in Monroe, Putnam, and Rockland counties – are “related to measles exposures from international travel but not affiliated with the 2018 outbreak,” the New York State Department of Health said in a written statement. Officials in Rockland County had declared its 2018 measles outbreak, which involved 312 cases in 2018 and 2019, over on Sept. 25.

. Of those cases, 1,163 (93%) were associated with 22 outbreaks, with the two largest occurring in New York City and Rockland County. “These two almost year-long outbreaks placed the United States at risk for losing measles elimination status,” the CDC said in a separate report, but “robust responses … ended transmission before the 1-year mark.”

Viral cause of acute flaccid myelitis eludes detection

A study of 305 cases of acute flaccid myelitis has found further evidence of a viral etiology but is yet to identify a single pathogen as the primary cause.

Writing in Pediatrics, researchers published an analysis of patients presenting with acute flaccid limb weakness from January 2015 to December 2017 across 43 states.

A total of 25 cases were judged as probable for acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) because they met clinical criteria and had a white blood cell count above 5 cells per mm3 in cerebrospinal fluid, while 193 were judged as confirmed cases based on the additional presence of spinal cord gray matter lesions on MRI.

Overall, 83% of patients had experienced fever, cough, runny nose, vomiting, and/or diarrhea for a median of 5 days before limb weakness began. Two-thirds of patients had experienced a respiratory illness, 62% had experienced a fever, and 29% had experienced gastrointestinal illness.

Overall, 47% of the 193 patients who had specimens tested at a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or non-CDC laboratory had a pathogen found at any site, 10% had a pathogen detected from a sterile site such as cerebrospinal fluid or sera, and 42% had a pathogen detected from a nonsterile site.

Among 72 patients who had serum specimens tested at the CDC, 2 were positive for enteroviruses. Among the 90 patients who had upper respiratory specimens tested, 36% were positive for either enteroviruses or rhinoviruses.

A number of stool specimens were also tested; 15% were positive for enteroviruses or rhinoviruses and one was positive for parechovirus.

Cerebrospinal fluid was tested in 170 patients, of which 4 were positive for enteroviruses. The testing also found adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and mycoplasma in six patients. Sera testing of 123 patients found 9 were positive for enteroviruses, West Nile virus, mycoplasma, and coxsackievirus B.

“In our summary of national AFM surveillance from 2015 to 2017, we demonstrate that cases were widely distributed across the United States, the majority of cases occurred in late summer or fall, children were predominantly affected, there is a spectrum of clinical severity, and no single pathogen was identified as the primary cause of AFM,” wrote Tracy Ayers, PhD, from the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, and coauthors. “We conclude that symptoms of a viral syndrome within the week before limb weakness, detection of viral pathogens from sterile and nonsterile sites from almost half of patients, and seasonality of AFM incidence, particularly during the 2016 peak year, strongly suggest a viral etiology, including [enteroviruses].”

The authors of an accompanying editorial noted that the clinical syndrome of acute flaccid paralysis caused by myelitis in the gray matter of the spinal cord has previously been associated with a range of viruses, including poliovirus, enteroviruses, and flaviviruses, so a single etiology to explain all cases would not be expected.

“The central question remains: What is driving seasonal biennial nationwide outbreaks of AFM since 2014?” wrote Kevin Messaca, MD, and colleagues from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Two authors declared consultancies, grants, and research contracts with the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared. One editorial author declared funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Ayers T et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Oct 7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1619.

*Updated 10/14/2019.

A study of 305 cases of acute flaccid myelitis has found further evidence of a viral etiology but is yet to identify a single pathogen as the primary cause.

Writing in Pediatrics, researchers published an analysis of patients presenting with acute flaccid limb weakness from January 2015 to December 2017 across 43 states.

A total of 25 cases were judged as probable for acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) because they met clinical criteria and had a white blood cell count above 5 cells per mm3 in cerebrospinal fluid, while 193 were judged as confirmed cases based on the additional presence of spinal cord gray matter lesions on MRI.

Overall, 83% of patients had experienced fever, cough, runny nose, vomiting, and/or diarrhea for a median of 5 days before limb weakness began. Two-thirds of patients had experienced a respiratory illness, 62% had experienced a fever, and 29% had experienced gastrointestinal illness.

Overall, 47% of the 193 patients who had specimens tested at a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or non-CDC laboratory had a pathogen found at any site, 10% had a pathogen detected from a sterile site such as cerebrospinal fluid or sera, and 42% had a pathogen detected from a nonsterile site.

Among 72 patients who had serum specimens tested at the CDC, 2 were positive for enteroviruses. Among the 90 patients who had upper respiratory specimens tested, 36% were positive for either enteroviruses or rhinoviruses.

A number of stool specimens were also tested; 15% were positive for enteroviruses or rhinoviruses and one was positive for parechovirus.

Cerebrospinal fluid was tested in 170 patients, of which 4 were positive for enteroviruses. The testing also found adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and mycoplasma in six patients. Sera testing of 123 patients found 9 were positive for enteroviruses, West Nile virus, mycoplasma, and coxsackievirus B.

“In our summary of national AFM surveillance from 2015 to 2017, we demonstrate that cases were widely distributed across the United States, the majority of cases occurred in late summer or fall, children were predominantly affected, there is a spectrum of clinical severity, and no single pathogen was identified as the primary cause of AFM,” wrote Tracy Ayers, PhD, from the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, and coauthors. “We conclude that symptoms of a viral syndrome within the week before limb weakness, detection of viral pathogens from sterile and nonsterile sites from almost half of patients, and seasonality of AFM incidence, particularly during the 2016 peak year, strongly suggest a viral etiology, including [enteroviruses].”

The authors of an accompanying editorial noted that the clinical syndrome of acute flaccid paralysis caused by myelitis in the gray matter of the spinal cord has previously been associated with a range of viruses, including poliovirus, enteroviruses, and flaviviruses, so a single etiology to explain all cases would not be expected.

“The central question remains: What is driving seasonal biennial nationwide outbreaks of AFM since 2014?” wrote Kevin Messaca, MD, and colleagues from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

Two authors declared consultancies, grants, and research contracts with the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared. One editorial author declared funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCE: Ayers T et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Oct 7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1619.

*Updated 10/14/2019.

A study of 305 cases of acute flaccid myelitis has found further evidence of a viral etiology but is yet to identify a single pathogen as the primary cause.

Writing in Pediatrics, researchers published an analysis of patients presenting with acute flaccid limb weakness from January 2015 to December 2017 across 43 states.

A total of 25 cases were judged as probable for acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) because they met clinical criteria and had a white blood cell count above 5 cells per mm3 in cerebrospinal fluid, while 193 were judged as confirmed cases based on the additional presence of spinal cord gray matter lesions on MRI.

Overall, 83% of patients had experienced fever, cough, runny nose, vomiting, and/or diarrhea for a median of 5 days before limb weakness began. Two-thirds of patients had experienced a respiratory illness, 62% had experienced a fever, and 29% had experienced gastrointestinal illness.

Overall, 47% of the 193 patients who had specimens tested at a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or non-CDC laboratory had a pathogen found at any site, 10% had a pathogen detected from a sterile site such as cerebrospinal fluid or sera, and 42% had a pathogen detected from a nonsterile site.

Among 72 patients who had serum specimens tested at the CDC, 2 were positive for enteroviruses. Among the 90 patients who had upper respiratory specimens tested, 36% were positive for either enteroviruses or rhinoviruses.

A number of stool specimens were also tested; 15% were positive for enteroviruses or rhinoviruses and one was positive for parechovirus.

Cerebrospinal fluid was tested in 170 patients, of which 4 were positive for enteroviruses. The testing also found adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and mycoplasma in six patients. Sera testing of 123 patients found 9 were positive for enteroviruses, West Nile virus, mycoplasma, and coxsackievirus B.