User login

What’s Eating You? The South African Fattail Scorpion Revisited

Identification

The South African fattail scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus)(Figure) is one of the most poisonous scorpions in southern Africa.1 A member of the Buthidae scorpion family, it can grow as long as 15 cm and is dark brown-black with lighter red-brown pincers. Similar to other fattail scorpions, it has slender pincers (pedipalps) and a thick square tail (the telson). Parabuthus transvaalicus inhabits hot dry deserts, scrublands, and semiarid regions.1,2 It also is popular in exotic pet collections, the most common source of stings in the United States.

Stings and Envenomation

Scorpions with thicker tails generally have more potent venom than those with slender tails and thick pincers. Venom is injected by a stinger at the tip of the telson1; P transvaalicus also can spray venom as far as 3 m.1,2 Venom is not known to cause toxicity through skin contact but could represent a hazard if sprayed in the eye.

Scorpion toxins are a group of complex neurotoxins that act on sodium channels, either retarding inactivation (α toxin) or enhancing activation (β toxin), causing massive depolarization of excitable cells.1,3 The toxin causes neurons to fire repetitively.4 Neurotransmitters—noradrenaline, adrenaline, and acetylcholine—cause the observed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and skeletal muscle effects.1

Incidence

Worldwide, more than 1.2 million individuals are stung by a scorpion annually, causing more than 3250 deaths a year.5 Adults are stung more often, but children experience more severe envenomation, are more likely to develop severe illness requiring intensive supportive care, and have a higher mortality.4

As many as one-third of patients stung by a Parabuthus scorpion develop neuromuscular toxicity, which can be life-threatening.6 In a study of 277 envenomations by P transvaalicus, 10% of patients developed severe symptoms and 5 died. Children younger than 10 years and adults older than 50 years are at greatest risk for

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of scorpion envenomation varies with the species involved, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s weight and baseline health.1 Scorpion envenomation is divided into 4 grades based on the severity of a sting:

• Grade I: pain and paresthesia at the envenomation site; usually, no local inflammation

• Grade II: local symptoms as well as more remote pain and paresthesia; pain can radiate up the affected limb

• Grade III: cranial nerve or somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction; either presentation can have associated autonomic dysfunction

• Grade IV: both cranial nerve and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction, with associated auto-nomic dysfunction

The initial symptom of a scorpion sting is intense burning pain. The sting site might be unimpressive, with only a mild local reaction. Symptoms usually progress to maximum severity within 5 hours.1 Muscle pain, cramps, and weakness are prominent. The patient might have difficulty walking and swallowing, with increased salivation and drooling, and visual disturbance with abnormal eye movements. Pulse, blood pressure, and temperature often are elevated. The patient might be hyperreflexic with clonus.1,6

Symptoms of increased sympathetic activity are hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, perspiration, hyperglycemia, and restlessness.1,2 Parasympathetic effects are increased salivation, hypotension, bradycardia, and gastric distension. Skeletal muscle effects include tremors and involuntary muscle movement, which can be severe. Cranial nerve dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, drooling, abnormal eye movements, blurred vision, slurred speech, and tongue fasciculations. Subsequent development of muscle weakness, bulbar paralysis, and difficulty breathing may be caused by depletion of neurotransmitters after prolonged excessive neuronal activity.1

Distinctive Signs in Younger Patients

A child who is stung by a scorpion might have symptoms similar to those seen in an adult victim but can also experience an extreme form of restlessness that indicates severe envenomation characterized by inability to lay still, violent muscle twitching, and uncontrollable flailing of extremities. The child might have facial grimacing, with lip-smacking and chewing motions. In addition, bulbar paralysis and respiratory distress are more likely in children who have been stung than in adults.1,2

Management

Treatment of a P transvaalicus sting is directed at “scorpionism,” envenomation that is associated with systemic symptoms that can be life-threatening. Treatment comprises support of vital functions, symptomatic measures, and injection of antivenin.8

Support of Vital Functions

In adults, systemic symptoms can be delayed as long as 8 hours after the sting. However, most severe cases usually are evident within 60 minutes; infants can reach grade IV as quickly as 15 to 30 minutes.9,10 Loss of pharyngeal reflexes and development of respiratory distress are ominous warning signs requiring immediate respiratory support. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death.1 An asymptomatic child should be admitted to a hospital for observation for a minimum of 12 hours if the species of scorpion was not identified.2

Pain Relief

Most patients cannot tolerate an ice pack because of severe hyperesthesia. Infiltration of the local sting site with an anesthetic generally is safe and can provide some local pain relief. Intravenous fentanyl has been used in closely monitored patients because the drug is not associated with histamine release. Medications that cause release of histamine, such as morphine, can exacerbate or confuse the clinical picture.

Antivenin

Scorpion antivenin contains purified IgG fragments; allergic reactions are now rare. The sooner antivenin is administered, the greater the benefit. When administered early, it can prevent many of the most serious complications.7 In a randomized, double-blind study of critically ill children with clinically significant signs of scorpion envenomation, intravenous administration of scorpion-specific fragment antigen-binding 2 (F[(ab’]2) antivenin resulted in resolution of clinical symptoms within 4 hours.11

When managing grade III or IV scorpion envenomation, all patients should be admitted to a medical facility equipped to provide intensive supportive care; consider consultation with a regional poison control center. The World Health Organization maintains an international poison control center (at https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/en/) with regional telephone numbers; alternatively, in the United States, call the nationwide telephone number of the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222).

The World Health Organization has identified declining production of antivenin as a crisis.12

Resolution

Symptoms of envenomation typically resolve 9 to 30 hours after a sting in a patient with grade III or IV envenomation not treated with antivenin.4 However, pain and paresthesia occasionally last as long as 2 weeks. In rare cases, more long-term sequelae of burning paresthesia persist for months.4

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to be aware of the potential for life-threatening envenomation by certain scorpion species native to southern Africa. In the United States, stings of these species most often are seen in patients with a pet collection, but late sequelae also can be seen in travelers returning from an endemic region. The site of a sting often appears unimpressive initially, but severe hyperesthesia is common. Patients with cardiac, neurologic, or respiratory symptoms require intensive supportive care. Proper care can be lifesaving.

- Müller GJ, Modler H, Wium CA, et al. Scorpion sting in southern Africa: diagnosis and management. Continuing Medical Education. 2012;30:356-361.

- Müller GJ. Scorpionism in South Africa. a report of 42 serious scorpion envenomations. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:405-411.

- Quintero-Hernández V, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Gurrola GB, et al. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon. 2013;76:328-342.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop. 2008;107:71-79.

- Bergman NJ. Clinical description of Parabuthus transvaalicus scorpionism in Zimbabwe. Toxicon. 1997;35:759-771.

- Chippaux JP. Emerging options for the management of scorpion stings. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:165-173.

- Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:504-518.

- Amaral CF, Rezende NA. Both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary oedema after scorpion envenoming. Toxicon. 1997;35:997-998.

- Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:163-167.

- Boyer LV, Theodorou AA, Berg RA, et al; Arizona Envenomation Investigators. antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

- Theakston RD, Warrell DA, Griffiths E. Report of a WHO workshop on the standardization and control of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:541-557.

Identification

The South African fattail scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus)(Figure) is one of the most poisonous scorpions in southern Africa.1 A member of the Buthidae scorpion family, it can grow as long as 15 cm and is dark brown-black with lighter red-brown pincers. Similar to other fattail scorpions, it has slender pincers (pedipalps) and a thick square tail (the telson). Parabuthus transvaalicus inhabits hot dry deserts, scrublands, and semiarid regions.1,2 It also is popular in exotic pet collections, the most common source of stings in the United States.

Stings and Envenomation

Scorpions with thicker tails generally have more potent venom than those with slender tails and thick pincers. Venom is injected by a stinger at the tip of the telson1; P transvaalicus also can spray venom as far as 3 m.1,2 Venom is not known to cause toxicity through skin contact but could represent a hazard if sprayed in the eye.

Scorpion toxins are a group of complex neurotoxins that act on sodium channels, either retarding inactivation (α toxin) or enhancing activation (β toxin), causing massive depolarization of excitable cells.1,3 The toxin causes neurons to fire repetitively.4 Neurotransmitters—noradrenaline, adrenaline, and acetylcholine—cause the observed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and skeletal muscle effects.1

Incidence

Worldwide, more than 1.2 million individuals are stung by a scorpion annually, causing more than 3250 deaths a year.5 Adults are stung more often, but children experience more severe envenomation, are more likely to develop severe illness requiring intensive supportive care, and have a higher mortality.4

As many as one-third of patients stung by a Parabuthus scorpion develop neuromuscular toxicity, which can be life-threatening.6 In a study of 277 envenomations by P transvaalicus, 10% of patients developed severe symptoms and 5 died. Children younger than 10 years and adults older than 50 years are at greatest risk for

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of scorpion envenomation varies with the species involved, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s weight and baseline health.1 Scorpion envenomation is divided into 4 grades based on the severity of a sting:

• Grade I: pain and paresthesia at the envenomation site; usually, no local inflammation

• Grade II: local symptoms as well as more remote pain and paresthesia; pain can radiate up the affected limb

• Grade III: cranial nerve or somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction; either presentation can have associated autonomic dysfunction

• Grade IV: both cranial nerve and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction, with associated auto-nomic dysfunction

The initial symptom of a scorpion sting is intense burning pain. The sting site might be unimpressive, with only a mild local reaction. Symptoms usually progress to maximum severity within 5 hours.1 Muscle pain, cramps, and weakness are prominent. The patient might have difficulty walking and swallowing, with increased salivation and drooling, and visual disturbance with abnormal eye movements. Pulse, blood pressure, and temperature often are elevated. The patient might be hyperreflexic with clonus.1,6

Symptoms of increased sympathetic activity are hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, perspiration, hyperglycemia, and restlessness.1,2 Parasympathetic effects are increased salivation, hypotension, bradycardia, and gastric distension. Skeletal muscle effects include tremors and involuntary muscle movement, which can be severe. Cranial nerve dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, drooling, abnormal eye movements, blurred vision, slurred speech, and tongue fasciculations. Subsequent development of muscle weakness, bulbar paralysis, and difficulty breathing may be caused by depletion of neurotransmitters after prolonged excessive neuronal activity.1

Distinctive Signs in Younger Patients

A child who is stung by a scorpion might have symptoms similar to those seen in an adult victim but can also experience an extreme form of restlessness that indicates severe envenomation characterized by inability to lay still, violent muscle twitching, and uncontrollable flailing of extremities. The child might have facial grimacing, with lip-smacking and chewing motions. In addition, bulbar paralysis and respiratory distress are more likely in children who have been stung than in adults.1,2

Management

Treatment of a P transvaalicus sting is directed at “scorpionism,” envenomation that is associated with systemic symptoms that can be life-threatening. Treatment comprises support of vital functions, symptomatic measures, and injection of antivenin.8

Support of Vital Functions

In adults, systemic symptoms can be delayed as long as 8 hours after the sting. However, most severe cases usually are evident within 60 minutes; infants can reach grade IV as quickly as 15 to 30 minutes.9,10 Loss of pharyngeal reflexes and development of respiratory distress are ominous warning signs requiring immediate respiratory support. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death.1 An asymptomatic child should be admitted to a hospital for observation for a minimum of 12 hours if the species of scorpion was not identified.2

Pain Relief

Most patients cannot tolerate an ice pack because of severe hyperesthesia. Infiltration of the local sting site with an anesthetic generally is safe and can provide some local pain relief. Intravenous fentanyl has been used in closely monitored patients because the drug is not associated with histamine release. Medications that cause release of histamine, such as morphine, can exacerbate or confuse the clinical picture.

Antivenin

Scorpion antivenin contains purified IgG fragments; allergic reactions are now rare. The sooner antivenin is administered, the greater the benefit. When administered early, it can prevent many of the most serious complications.7 In a randomized, double-blind study of critically ill children with clinically significant signs of scorpion envenomation, intravenous administration of scorpion-specific fragment antigen-binding 2 (F[(ab’]2) antivenin resulted in resolution of clinical symptoms within 4 hours.11

When managing grade III or IV scorpion envenomation, all patients should be admitted to a medical facility equipped to provide intensive supportive care; consider consultation with a regional poison control center. The World Health Organization maintains an international poison control center (at https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/en/) with regional telephone numbers; alternatively, in the United States, call the nationwide telephone number of the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222).

The World Health Organization has identified declining production of antivenin as a crisis.12

Resolution

Symptoms of envenomation typically resolve 9 to 30 hours after a sting in a patient with grade III or IV envenomation not treated with antivenin.4 However, pain and paresthesia occasionally last as long as 2 weeks. In rare cases, more long-term sequelae of burning paresthesia persist for months.4

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to be aware of the potential for life-threatening envenomation by certain scorpion species native to southern Africa. In the United States, stings of these species most often are seen in patients with a pet collection, but late sequelae also can be seen in travelers returning from an endemic region. The site of a sting often appears unimpressive initially, but severe hyperesthesia is common. Patients with cardiac, neurologic, or respiratory symptoms require intensive supportive care. Proper care can be lifesaving.

Identification

The South African fattail scorpion (Parabuthus transvaalicus)(Figure) is one of the most poisonous scorpions in southern Africa.1 A member of the Buthidae scorpion family, it can grow as long as 15 cm and is dark brown-black with lighter red-brown pincers. Similar to other fattail scorpions, it has slender pincers (pedipalps) and a thick square tail (the telson). Parabuthus transvaalicus inhabits hot dry deserts, scrublands, and semiarid regions.1,2 It also is popular in exotic pet collections, the most common source of stings in the United States.

Stings and Envenomation

Scorpions with thicker tails generally have more potent venom than those with slender tails and thick pincers. Venom is injected by a stinger at the tip of the telson1; P transvaalicus also can spray venom as far as 3 m.1,2 Venom is not known to cause toxicity through skin contact but could represent a hazard if sprayed in the eye.

Scorpion toxins are a group of complex neurotoxins that act on sodium channels, either retarding inactivation (α toxin) or enhancing activation (β toxin), causing massive depolarization of excitable cells.1,3 The toxin causes neurons to fire repetitively.4 Neurotransmitters—noradrenaline, adrenaline, and acetylcholine—cause the observed sympathetic, parasympathetic, and skeletal muscle effects.1

Incidence

Worldwide, more than 1.2 million individuals are stung by a scorpion annually, causing more than 3250 deaths a year.5 Adults are stung more often, but children experience more severe envenomation, are more likely to develop severe illness requiring intensive supportive care, and have a higher mortality.4

As many as one-third of patients stung by a Parabuthus scorpion develop neuromuscular toxicity, which can be life-threatening.6 In a study of 277 envenomations by P transvaalicus, 10% of patients developed severe symptoms and 5 died. Children younger than 10 years and adults older than 50 years are at greatest risk for

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of scorpion envenomation varies with the species involved, the amount of venom injected, and the victim’s weight and baseline health.1 Scorpion envenomation is divided into 4 grades based on the severity of a sting:

• Grade I: pain and paresthesia at the envenomation site; usually, no local inflammation

• Grade II: local symptoms as well as more remote pain and paresthesia; pain can radiate up the affected limb

• Grade III: cranial nerve or somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction; either presentation can have associated autonomic dysfunction

• Grade IV: both cranial nerve and somatic skeletal neuromuscular dysfunction, with associated auto-nomic dysfunction

The initial symptom of a scorpion sting is intense burning pain. The sting site might be unimpressive, with only a mild local reaction. Symptoms usually progress to maximum severity within 5 hours.1 Muscle pain, cramps, and weakness are prominent. The patient might have difficulty walking and swallowing, with increased salivation and drooling, and visual disturbance with abnormal eye movements. Pulse, blood pressure, and temperature often are elevated. The patient might be hyperreflexic with clonus.1,6

Symptoms of increased sympathetic activity are hypertension, tachycardia, cardiac dysrhythmia, perspiration, hyperglycemia, and restlessness.1,2 Parasympathetic effects are increased salivation, hypotension, bradycardia, and gastric distension. Skeletal muscle effects include tremors and involuntary muscle movement, which can be severe. Cranial nerve dysfunction may manifest as dysphagia, drooling, abnormal eye movements, blurred vision, slurred speech, and tongue fasciculations. Subsequent development of muscle weakness, bulbar paralysis, and difficulty breathing may be caused by depletion of neurotransmitters after prolonged excessive neuronal activity.1

Distinctive Signs in Younger Patients

A child who is stung by a scorpion might have symptoms similar to those seen in an adult victim but can also experience an extreme form of restlessness that indicates severe envenomation characterized by inability to lay still, violent muscle twitching, and uncontrollable flailing of extremities. The child might have facial grimacing, with lip-smacking and chewing motions. In addition, bulbar paralysis and respiratory distress are more likely in children who have been stung than in adults.1,2

Management

Treatment of a P transvaalicus sting is directed at “scorpionism,” envenomation that is associated with systemic symptoms that can be life-threatening. Treatment comprises support of vital functions, symptomatic measures, and injection of antivenin.8

Support of Vital Functions

In adults, systemic symptoms can be delayed as long as 8 hours after the sting. However, most severe cases usually are evident within 60 minutes; infants can reach grade IV as quickly as 15 to 30 minutes.9,10 Loss of pharyngeal reflexes and development of respiratory distress are ominous warning signs requiring immediate respiratory support. Respiratory failure is the most common cause of death.1 An asymptomatic child should be admitted to a hospital for observation for a minimum of 12 hours if the species of scorpion was not identified.2

Pain Relief

Most patients cannot tolerate an ice pack because of severe hyperesthesia. Infiltration of the local sting site with an anesthetic generally is safe and can provide some local pain relief. Intravenous fentanyl has been used in closely monitored patients because the drug is not associated with histamine release. Medications that cause release of histamine, such as morphine, can exacerbate or confuse the clinical picture.

Antivenin

Scorpion antivenin contains purified IgG fragments; allergic reactions are now rare. The sooner antivenin is administered, the greater the benefit. When administered early, it can prevent many of the most serious complications.7 In a randomized, double-blind study of critically ill children with clinically significant signs of scorpion envenomation, intravenous administration of scorpion-specific fragment antigen-binding 2 (F[(ab’]2) antivenin resulted in resolution of clinical symptoms within 4 hours.11

When managing grade III or IV scorpion envenomation, all patients should be admitted to a medical facility equipped to provide intensive supportive care; consider consultation with a regional poison control center. The World Health Organization maintains an international poison control center (at https://www.who.int/ipcs/poisons/centre/en/) with regional telephone numbers; alternatively, in the United States, call the nationwide telephone number of the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222).

The World Health Organization has identified declining production of antivenin as a crisis.12

Resolution

Symptoms of envenomation typically resolve 9 to 30 hours after a sting in a patient with grade III or IV envenomation not treated with antivenin.4 However, pain and paresthesia occasionally last as long as 2 weeks. In rare cases, more long-term sequelae of burning paresthesia persist for months.4

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to be aware of the potential for life-threatening envenomation by certain scorpion species native to southern Africa. In the United States, stings of these species most often are seen in patients with a pet collection, but late sequelae also can be seen in travelers returning from an endemic region. The site of a sting often appears unimpressive initially, but severe hyperesthesia is common. Patients with cardiac, neurologic, or respiratory symptoms require intensive supportive care. Proper care can be lifesaving.

- Müller GJ, Modler H, Wium CA, et al. Scorpion sting in southern Africa: diagnosis and management. Continuing Medical Education. 2012;30:356-361.

- Müller GJ. Scorpionism in South Africa. a report of 42 serious scorpion envenomations. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:405-411.

- Quintero-Hernández V, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Gurrola GB, et al. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon. 2013;76:328-342.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop. 2008;107:71-79.

- Bergman NJ. Clinical description of Parabuthus transvaalicus scorpionism in Zimbabwe. Toxicon. 1997;35:759-771.

- Chippaux JP. Emerging options for the management of scorpion stings. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:165-173.

- Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:504-518.

- Amaral CF, Rezende NA. Both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary oedema after scorpion envenoming. Toxicon. 1997;35:997-998.

- Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:163-167.

- Boyer LV, Theodorou AA, Berg RA, et al; Arizona Envenomation Investigators. antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

- Theakston RD, Warrell DA, Griffiths E. Report of a WHO workshop on the standardization and control of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:541-557.

- Müller GJ, Modler H, Wium CA, et al. Scorpion sting in southern Africa: diagnosis and management. Continuing Medical Education. 2012;30:356-361.

- Müller GJ. Scorpionism in South Africa. a report of 42 serious scorpion envenomations. S Afr Med J. 1993;83:405-411.

- Quintero-Hernández V, Jiménez-Vargas JM, Gurrola GB, et al. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon. 2013;76:328-342.

- LoVecchio F, McBride C. Scorpion envenomations in young children in central Arizona. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:937-940.

- Chippaux JP, Goyffon M. Epidemiology of scorpionism: a global appraisal. Acta Trop. 2008;107:71-79.

- Bergman NJ. Clinical description of Parabuthus transvaalicus scorpionism in Zimbabwe. Toxicon. 1997;35:759-771.

- Chippaux JP. Emerging options for the management of scorpion stings. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2012;6:165-173.

- Santos MS, Silva CG, Neto BS, et al. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of scorpionism in the world: a systematic review. Wilderness Environ Med. 2016;27:504-518.

- Amaral CF, Rezende NA. Both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary oedema after scorpion envenoming. Toxicon. 1997;35:997-998.

- Bergman NJ. Scorpion sting in Zimbabwe. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:163-167.

- Boyer LV, Theodorou AA, Berg RA, et al; Arizona Envenomation Investigators. antivenom for critically ill children with neurotoxicity from scorpion stings. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2090-2098.

- Theakston RD, Warrell DA, Griffiths E. Report of a WHO workshop on the standardization and control of antivenoms. Toxicon. 2003;41:541-557.

Practice Points

- Exotic and dangerous pets are becoming more popular. Scorpion stings cause potentially life-threatening neurotoxicity, with children particularly susceptible.

- Fattail scorpions are particularly dangerous and physicians should be aware that their stings may be encountered worldwide.

- Symptoms present 1 to 8 hours after envenomation, with severe cases showing hyperreflexia, clonus, difficulty swallowing, and respiratory distress. The sting site may be unimpressive.

Liraglutide ‘option’ for treating pediatric type 2 diabetes

BARCELONA – The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) liraglutide added onto metformin with or without basal insulin effectively reduced hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose levels in children with type 2 diabetes in the 52-week ELLIPSE study.

The primary endpoint of the trial, which was the mean change in HbA1c from baseline to 26 weeks, was met, with a greater percentage point decrease with liraglutide (Victoza) than placebo (–0.64 vs. +0.42), with an estimated treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). At the end of the study, the percentage point changes were –0.50 and +0.80, with a between-group difference of –1.30 in favor of liraglutide.

“Those of us working in pediatric practice are seeing an increasing demand for our clinical services in children with type 2 diabetes,” study investigator Timothy Barrett, PhD, MBBS, observed at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. This reflects the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes in this age group and is most likely linked to the rising rates of obesity and overweight that have been reported widely in young people in recent years, he added.

“Unfortunately, we look with envy upon our adult physician colleagues, and the range of treatments they have available to treat type 2 diabetes in adults.” In pediatrics, the only licensed treatments that have been available until recently were metformin and insulin, with the latter being an “illogical treatment to treat those with obesity-related diabetes.” The study’s findings, however, support liraglutide as another option to consider, said Dr. Barrett, a pediatric endocrinologist and professor of pediatrics and child health based at the University of Birmingham, England.

“Liraglutide at doses of up to 1.8 mg/day when added to metformin, and basal insulin if required, does seem to offer an additional treatment option for children and young people with type 2 diabetes who require improved glycemic control after they’ve reached a maximum dose of metformin,” he said.

ELLIPSE (Evaluation of Liraglutide in Pediatrics with Diabetes) was a multicenter, randomized, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of liraglutide as an add-on treatment to metformin, with or without basal insulin, in 134 overweight or obese children and adolescents (aged 10-17) with type 2 diabetes.

For inclusion, patients had to be able to complete the trial before their 18th birthday, and have an HbA1c of at least 7% if being treated with diet and exercise, or 6.5% or higher if already being treated with metformin, with or without insulin. Body mass index had to be above the 85the percentile for their age and sex.

Of 307 children and adolescents screened at 84 centers in 25 countries, 135 were randomized and 134 were treated between 2012 and 2018. Screening took place over a period of 2 weeks, after which time those eligible for the trial underwent a 3- to 4-week period where their dose of metformin was titrated if needed followed by an 8-week maintenance period. Only after that was randomization to liraglutide or placebo done, with the GLP-1R started at a subcutaneous dose of 0.6 mg and titrated up to 1.2 or 1.8 mg over 3 days to achieve a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of less than 6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL). However, not all patients were escalated to the top dose, Dr. Barrett noted.

The mean age of patients in the trial was 14.5 years; about 60% of patients were female. The duration of diabetes was about 1.9 years and the average body weight and BMI a respective 91 kg and 33 kg/m2.

Over the course of the study, FPG fell by 1.06 mmol/L at week 26 and 1.03 mmol/L at week 52 in the liraglutide group but rose in the placebo group by 0.80 and 0.78 mmol/L, respectively. The estimated treatment difference was –1.88 (P = .002) and –1.81 at 26 an 52 weeks, respectively.

What was “a really gratifying to see,” said Dr. Barrett, was that the proportion of children and young people achieving a glycemic target of an HbA1c of less than 7% by the end of the double-blind treatment period was significantly higher in the liraglutide than placebo group, at 63.7% and 36.5%, respectively.

Most of the adverse effects seen in the study were gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, in about 20% of liraglutide-treated patients, compared with roughly 10% of placebo-treated patients. “This is really reflected in the adult studies as well, and many of these were thankfully transient.”

As for hypoglycemia, Dr. Barrett reported that there was a higher rate in liraglutide- than placebo-treated patients (45.5% vs. 25% for any event), although there were no severe episodes in the liraglutide group and one in the placebo group. Almost a third (31%) of hypoglycemic episodes were asymptomatic, versus 17.6% for the placebo group.

“This is the first successfully completed phase 3 trial showing efficacy of a noninsulin agent, in this case, for children who do not get managed solely on metformin monotherapy,” Dr. Barrett said.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved liraglutide for use in pediatric patients 10 years or older with type 2 diabetes, based in part on results of the ELLIPSE results, Novo Nordisk announced in June. The trial results were published prior to the EASD meeting (Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15;381:637-46).

Novo Nordisk initiated and funded the trial, and most of the investigators reported receiving funds from the company outside the submitted work. Dr Barrett disclosed being a consultant to and/or receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk and Servier.

SOURCE: Barrett T et al. EASD 2019. Abstract 84.

BARCELONA – The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) liraglutide added onto metformin with or without basal insulin effectively reduced hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose levels in children with type 2 diabetes in the 52-week ELLIPSE study.

The primary endpoint of the trial, which was the mean change in HbA1c from baseline to 26 weeks, was met, with a greater percentage point decrease with liraglutide (Victoza) than placebo (–0.64 vs. +0.42), with an estimated treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). At the end of the study, the percentage point changes were –0.50 and +0.80, with a between-group difference of –1.30 in favor of liraglutide.

“Those of us working in pediatric practice are seeing an increasing demand for our clinical services in children with type 2 diabetes,” study investigator Timothy Barrett, PhD, MBBS, observed at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. This reflects the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes in this age group and is most likely linked to the rising rates of obesity and overweight that have been reported widely in young people in recent years, he added.

“Unfortunately, we look with envy upon our adult physician colleagues, and the range of treatments they have available to treat type 2 diabetes in adults.” In pediatrics, the only licensed treatments that have been available until recently were metformin and insulin, with the latter being an “illogical treatment to treat those with obesity-related diabetes.” The study’s findings, however, support liraglutide as another option to consider, said Dr. Barrett, a pediatric endocrinologist and professor of pediatrics and child health based at the University of Birmingham, England.

“Liraglutide at doses of up to 1.8 mg/day when added to metformin, and basal insulin if required, does seem to offer an additional treatment option for children and young people with type 2 diabetes who require improved glycemic control after they’ve reached a maximum dose of metformin,” he said.

ELLIPSE (Evaluation of Liraglutide in Pediatrics with Diabetes) was a multicenter, randomized, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of liraglutide as an add-on treatment to metformin, with or without basal insulin, in 134 overweight or obese children and adolescents (aged 10-17) with type 2 diabetes.

For inclusion, patients had to be able to complete the trial before their 18th birthday, and have an HbA1c of at least 7% if being treated with diet and exercise, or 6.5% or higher if already being treated with metformin, with or without insulin. Body mass index had to be above the 85the percentile for their age and sex.

Of 307 children and adolescents screened at 84 centers in 25 countries, 135 were randomized and 134 were treated between 2012 and 2018. Screening took place over a period of 2 weeks, after which time those eligible for the trial underwent a 3- to 4-week period where their dose of metformin was titrated if needed followed by an 8-week maintenance period. Only after that was randomization to liraglutide or placebo done, with the GLP-1R started at a subcutaneous dose of 0.6 mg and titrated up to 1.2 or 1.8 mg over 3 days to achieve a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of less than 6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL). However, not all patients were escalated to the top dose, Dr. Barrett noted.

The mean age of patients in the trial was 14.5 years; about 60% of patients were female. The duration of diabetes was about 1.9 years and the average body weight and BMI a respective 91 kg and 33 kg/m2.

Over the course of the study, FPG fell by 1.06 mmol/L at week 26 and 1.03 mmol/L at week 52 in the liraglutide group but rose in the placebo group by 0.80 and 0.78 mmol/L, respectively. The estimated treatment difference was –1.88 (P = .002) and –1.81 at 26 an 52 weeks, respectively.

What was “a really gratifying to see,” said Dr. Barrett, was that the proportion of children and young people achieving a glycemic target of an HbA1c of less than 7% by the end of the double-blind treatment period was significantly higher in the liraglutide than placebo group, at 63.7% and 36.5%, respectively.

Most of the adverse effects seen in the study were gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, in about 20% of liraglutide-treated patients, compared with roughly 10% of placebo-treated patients. “This is really reflected in the adult studies as well, and many of these were thankfully transient.”

As for hypoglycemia, Dr. Barrett reported that there was a higher rate in liraglutide- than placebo-treated patients (45.5% vs. 25% for any event), although there were no severe episodes in the liraglutide group and one in the placebo group. Almost a third (31%) of hypoglycemic episodes were asymptomatic, versus 17.6% for the placebo group.

“This is the first successfully completed phase 3 trial showing efficacy of a noninsulin agent, in this case, for children who do not get managed solely on metformin monotherapy,” Dr. Barrett said.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved liraglutide for use in pediatric patients 10 years or older with type 2 diabetes, based in part on results of the ELLIPSE results, Novo Nordisk announced in June. The trial results were published prior to the EASD meeting (Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15;381:637-46).

Novo Nordisk initiated and funded the trial, and most of the investigators reported receiving funds from the company outside the submitted work. Dr Barrett disclosed being a consultant to and/or receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk and Servier.

SOURCE: Barrett T et al. EASD 2019. Abstract 84.

BARCELONA – The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) liraglutide added onto metformin with or without basal insulin effectively reduced hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose levels in children with type 2 diabetes in the 52-week ELLIPSE study.

The primary endpoint of the trial, which was the mean change in HbA1c from baseline to 26 weeks, was met, with a greater percentage point decrease with liraglutide (Victoza) than placebo (–0.64 vs. +0.42), with an estimated treatment difference of –1.06 percentage points (P less than .001). At the end of the study, the percentage point changes were –0.50 and +0.80, with a between-group difference of –1.30 in favor of liraglutide.

“Those of us working in pediatric practice are seeing an increasing demand for our clinical services in children with type 2 diabetes,” study investigator Timothy Barrett, PhD, MBBS, observed at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. This reflects the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes in this age group and is most likely linked to the rising rates of obesity and overweight that have been reported widely in young people in recent years, he added.

“Unfortunately, we look with envy upon our adult physician colleagues, and the range of treatments they have available to treat type 2 diabetes in adults.” In pediatrics, the only licensed treatments that have been available until recently were metformin and insulin, with the latter being an “illogical treatment to treat those with obesity-related diabetes.” The study’s findings, however, support liraglutide as another option to consider, said Dr. Barrett, a pediatric endocrinologist and professor of pediatrics and child health based at the University of Birmingham, England.

“Liraglutide at doses of up to 1.8 mg/day when added to metformin, and basal insulin if required, does seem to offer an additional treatment option for children and young people with type 2 diabetes who require improved glycemic control after they’ve reached a maximum dose of metformin,” he said.

ELLIPSE (Evaluation of Liraglutide in Pediatrics with Diabetes) was a multicenter, randomized, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of liraglutide as an add-on treatment to metformin, with or without basal insulin, in 134 overweight or obese children and adolescents (aged 10-17) with type 2 diabetes.

For inclusion, patients had to be able to complete the trial before their 18th birthday, and have an HbA1c of at least 7% if being treated with diet and exercise, or 6.5% or higher if already being treated with metformin, with or without insulin. Body mass index had to be above the 85the percentile for their age and sex.

Of 307 children and adolescents screened at 84 centers in 25 countries, 135 were randomized and 134 were treated between 2012 and 2018. Screening took place over a period of 2 weeks, after which time those eligible for the trial underwent a 3- to 4-week period where their dose of metformin was titrated if needed followed by an 8-week maintenance period. Only after that was randomization to liraglutide or placebo done, with the GLP-1R started at a subcutaneous dose of 0.6 mg and titrated up to 1.2 or 1.8 mg over 3 days to achieve a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of less than 6.1 mmol/L (110 mg/dL). However, not all patients were escalated to the top dose, Dr. Barrett noted.

The mean age of patients in the trial was 14.5 years; about 60% of patients were female. The duration of diabetes was about 1.9 years and the average body weight and BMI a respective 91 kg and 33 kg/m2.

Over the course of the study, FPG fell by 1.06 mmol/L at week 26 and 1.03 mmol/L at week 52 in the liraglutide group but rose in the placebo group by 0.80 and 0.78 mmol/L, respectively. The estimated treatment difference was –1.88 (P = .002) and –1.81 at 26 an 52 weeks, respectively.

What was “a really gratifying to see,” said Dr. Barrett, was that the proportion of children and young people achieving a glycemic target of an HbA1c of less than 7% by the end of the double-blind treatment period was significantly higher in the liraglutide than placebo group, at 63.7% and 36.5%, respectively.

Most of the adverse effects seen in the study were gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, in about 20% of liraglutide-treated patients, compared with roughly 10% of placebo-treated patients. “This is really reflected in the adult studies as well, and many of these were thankfully transient.”

As for hypoglycemia, Dr. Barrett reported that there was a higher rate in liraglutide- than placebo-treated patients (45.5% vs. 25% for any event), although there were no severe episodes in the liraglutide group and one in the placebo group. Almost a third (31%) of hypoglycemic episodes were asymptomatic, versus 17.6% for the placebo group.

“This is the first successfully completed phase 3 trial showing efficacy of a noninsulin agent, in this case, for children who do not get managed solely on metformin monotherapy,” Dr. Barrett said.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved liraglutide for use in pediatric patients 10 years or older with type 2 diabetes, based in part on results of the ELLIPSE results, Novo Nordisk announced in June. The trial results were published prior to the EASD meeting (Tamborlane WV et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Aug 15;381:637-46).

Novo Nordisk initiated and funded the trial, and most of the investigators reported receiving funds from the company outside the submitted work. Dr Barrett disclosed being a consultant to and/or receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk and Servier.

SOURCE: Barrett T et al. EASD 2019. Abstract 84.

REPORTING FROM EASD 2019

High maternal lead levels linked to children’s obesity

Children born to mothers with high blood levels of lead have an increased risk of being overweight or obese, particularly if their mothers are also overweight, according to new research.

Adequate maternal plasma levels of folate, however, mitigated this risk.

“When considered simultaneously, maternal lead exposure, rather than early childhood lead exposure, contributed to overweight/obesity risk in a dose-response fashion across multiple developmental stages (preschool age, school age and early adolescence) and amplified intergenerational overweight/obesity risk (additively with maternal overweight/obesity),” Guoying Wang, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and associates, reported in JAMA Network Open.

“These findings support the hypothesis that the obesity epidemic could be related to environmental chemical exposures in utero and raise the possibility that optimal maternal folate supplementation may help counteract the adverse effects of environmental lead exposure,” the authors wrote.

The prospective urban, low-income cohort study, which ran from 2002 to 2013, involved 1,442 mother-child pairs who joined the study when the children were born and attended follow-up visits at Boston Medical Center. The mean age of the mothers was 29 years, and the children were, on average, 8 years old at follow-up. Half the children were male; 67% of mothers were black, and 20% were Latina.

The researchers collected maternal blood samples within 24-72 hours after birth to measure red blood cell lead levels and plasma folate levels. Children’s whole-blood lead levels were measured during the first lead screening of their well child visits, at a median 10 months of age. Researchers tracked children’s body mass index Z-score and defined overweight/obesity as exceeding the 85th national percentile for their age and sex.

Detectable lead was present in all the mothers’ blood samples. The median maternal red blood cell lead level was 2.5 mcg/dL, although black mothers tended to have higher lead exposure than that of other racial groups. Median maternal plasma folate level was 32 nmol/L. Children’s blood lead levels were a median 1.4 mcg/dL, and their median BMI Z-score was 0.78.

Children whose mothers had red blood cell lead levels of 5.0 mcg/dL or greater (16%) had 65% greater odds of being overweight or obese compared with children whose mothers’ lead level was less than 2 mcg/dL, after adjustment for maternal education, race/ethnicity, smoking status, parity, diabetes, hypertensive disorder, preterm birth, fetal growth, and breastfeeding status (odds ratio [OR], 1.65; 95% confidence internal [CI], 1.18-2.32). Only 5.2% of children had whole-blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL or greater.

“Mothers with the highest red blood cell lead levels were older and multiparous, were more likely to be black and nonsmokers, had lower plasma folate levels and were more likely to have prepregnancy overweight/obesity and diabetes,” the authors reported.

The dose-response association did not lose significance when the researchers adjusted for children’s blood lead levels, maternal age, cesarean delivery, term births only, and black race. Nor did it change in a subset of children when the researchers adjusted for children’s physical activity.

The strength of the association increased when mothers also had a BMI greater than the average/healthy range. Children were more than four times more likely to be overweight or obese if their mothers were overweight or obese and had lead levels greater than 5.0 mcg/dL, compared with nonoverweight mothers with levels below 2 mcg/dL (OR, 4.24; 95% CI, 2.64-6.82).

Among children whose mothers were overweight/obese and had high blood lead levels, however, high folate levels appeared protective against obesity. These children had a 41% lower risk of being overweight or obese, compared with others in their group, if their mothers had plasma folate levels of at least 20 nmol/L (OR, 0.59 CI, 0.36-0.95; P = .03).

According to an invited commentary, “approximately 140,000 new chemicals and pesticides have appeared since 1950,” with “universal human exposure to approximately 5,000 of those,” wrote Marco Sanchez-Guerra, PhD, of the National Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City, and coauthors Andres Cardenas, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, and Citlalli Osorio-Yáñez, PhD, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City. Yet fewer than half of those chemicals have been tested for safety or toxic effect, the editorialists wrote, and scientists know little of their potential reproductive harm.

Dr. Sanchez-Guerra, Dr. Cardenas, and Dr. Osorio-Yáñez agreed with the study authors that elevated lead exposures, especially from gasoline before lead was removed in the United States in 1975, may partly explain the current epidemic of obesity.

“Identifying preventable prenatal causes of obesity is a cornerstone in the fight against the obesity epidemic,” the editorialists said. While most recommendations center on changes to diet and physical activity, environmental factors during pregnancy could be involved in childhood obesity as well.

“The study by Wang et al. opens the door to new questions about whether adequate folate intake might modify the adverse effects of other chemical exposures,” they continued, noting other research suggesting a protective effect from folate against health effects of air pollution exposure. “These efforts could yield substantial public health benefits and represent novel tools in fighting the obesity epidemic,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Neither the study authors nor the editorialists had industry financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Wang G et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912343. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12343; Sanchez-Guerra M et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912334. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12334.

Children born to mothers with high blood levels of lead have an increased risk of being overweight or obese, particularly if their mothers are also overweight, according to new research.

Adequate maternal plasma levels of folate, however, mitigated this risk.

“When considered simultaneously, maternal lead exposure, rather than early childhood lead exposure, contributed to overweight/obesity risk in a dose-response fashion across multiple developmental stages (preschool age, school age and early adolescence) and amplified intergenerational overweight/obesity risk (additively with maternal overweight/obesity),” Guoying Wang, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and associates, reported in JAMA Network Open.

“These findings support the hypothesis that the obesity epidemic could be related to environmental chemical exposures in utero and raise the possibility that optimal maternal folate supplementation may help counteract the adverse effects of environmental lead exposure,” the authors wrote.

The prospective urban, low-income cohort study, which ran from 2002 to 2013, involved 1,442 mother-child pairs who joined the study when the children were born and attended follow-up visits at Boston Medical Center. The mean age of the mothers was 29 years, and the children were, on average, 8 years old at follow-up. Half the children were male; 67% of mothers were black, and 20% were Latina.

The researchers collected maternal blood samples within 24-72 hours after birth to measure red blood cell lead levels and plasma folate levels. Children’s whole-blood lead levels were measured during the first lead screening of their well child visits, at a median 10 months of age. Researchers tracked children’s body mass index Z-score and defined overweight/obesity as exceeding the 85th national percentile for their age and sex.

Detectable lead was present in all the mothers’ blood samples. The median maternal red blood cell lead level was 2.5 mcg/dL, although black mothers tended to have higher lead exposure than that of other racial groups. Median maternal plasma folate level was 32 nmol/L. Children’s blood lead levels were a median 1.4 mcg/dL, and their median BMI Z-score was 0.78.

Children whose mothers had red blood cell lead levels of 5.0 mcg/dL or greater (16%) had 65% greater odds of being overweight or obese compared with children whose mothers’ lead level was less than 2 mcg/dL, after adjustment for maternal education, race/ethnicity, smoking status, parity, diabetes, hypertensive disorder, preterm birth, fetal growth, and breastfeeding status (odds ratio [OR], 1.65; 95% confidence internal [CI], 1.18-2.32). Only 5.2% of children had whole-blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL or greater.

“Mothers with the highest red blood cell lead levels were older and multiparous, were more likely to be black and nonsmokers, had lower plasma folate levels and were more likely to have prepregnancy overweight/obesity and diabetes,” the authors reported.

The dose-response association did not lose significance when the researchers adjusted for children’s blood lead levels, maternal age, cesarean delivery, term births only, and black race. Nor did it change in a subset of children when the researchers adjusted for children’s physical activity.

The strength of the association increased when mothers also had a BMI greater than the average/healthy range. Children were more than four times more likely to be overweight or obese if their mothers were overweight or obese and had lead levels greater than 5.0 mcg/dL, compared with nonoverweight mothers with levels below 2 mcg/dL (OR, 4.24; 95% CI, 2.64-6.82).

Among children whose mothers were overweight/obese and had high blood lead levels, however, high folate levels appeared protective against obesity. These children had a 41% lower risk of being overweight or obese, compared with others in their group, if their mothers had plasma folate levels of at least 20 nmol/L (OR, 0.59 CI, 0.36-0.95; P = .03).

According to an invited commentary, “approximately 140,000 new chemicals and pesticides have appeared since 1950,” with “universal human exposure to approximately 5,000 of those,” wrote Marco Sanchez-Guerra, PhD, of the National Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City, and coauthors Andres Cardenas, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, and Citlalli Osorio-Yáñez, PhD, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City. Yet fewer than half of those chemicals have been tested for safety or toxic effect, the editorialists wrote, and scientists know little of their potential reproductive harm.

Dr. Sanchez-Guerra, Dr. Cardenas, and Dr. Osorio-Yáñez agreed with the study authors that elevated lead exposures, especially from gasoline before lead was removed in the United States in 1975, may partly explain the current epidemic of obesity.

“Identifying preventable prenatal causes of obesity is a cornerstone in the fight against the obesity epidemic,” the editorialists said. While most recommendations center on changes to diet and physical activity, environmental factors during pregnancy could be involved in childhood obesity as well.

“The study by Wang et al. opens the door to new questions about whether adequate folate intake might modify the adverse effects of other chemical exposures,” they continued, noting other research suggesting a protective effect from folate against health effects of air pollution exposure. “These efforts could yield substantial public health benefits and represent novel tools in fighting the obesity epidemic,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Neither the study authors nor the editorialists had industry financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Wang G et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912343. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12343; Sanchez-Guerra M et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912334. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12334.

Children born to mothers with high blood levels of lead have an increased risk of being overweight or obese, particularly if their mothers are also overweight, according to new research.

Adequate maternal plasma levels of folate, however, mitigated this risk.

“When considered simultaneously, maternal lead exposure, rather than early childhood lead exposure, contributed to overweight/obesity risk in a dose-response fashion across multiple developmental stages (preschool age, school age and early adolescence) and amplified intergenerational overweight/obesity risk (additively with maternal overweight/obesity),” Guoying Wang, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and associates, reported in JAMA Network Open.

“These findings support the hypothesis that the obesity epidemic could be related to environmental chemical exposures in utero and raise the possibility that optimal maternal folate supplementation may help counteract the adverse effects of environmental lead exposure,” the authors wrote.

The prospective urban, low-income cohort study, which ran from 2002 to 2013, involved 1,442 mother-child pairs who joined the study when the children were born and attended follow-up visits at Boston Medical Center. The mean age of the mothers was 29 years, and the children were, on average, 8 years old at follow-up. Half the children were male; 67% of mothers were black, and 20% were Latina.

The researchers collected maternal blood samples within 24-72 hours after birth to measure red blood cell lead levels and plasma folate levels. Children’s whole-blood lead levels were measured during the first lead screening of their well child visits, at a median 10 months of age. Researchers tracked children’s body mass index Z-score and defined overweight/obesity as exceeding the 85th national percentile for their age and sex.

Detectable lead was present in all the mothers’ blood samples. The median maternal red blood cell lead level was 2.5 mcg/dL, although black mothers tended to have higher lead exposure than that of other racial groups. Median maternal plasma folate level was 32 nmol/L. Children’s blood lead levels were a median 1.4 mcg/dL, and their median BMI Z-score was 0.78.

Children whose mothers had red blood cell lead levels of 5.0 mcg/dL or greater (16%) had 65% greater odds of being overweight or obese compared with children whose mothers’ lead level was less than 2 mcg/dL, after adjustment for maternal education, race/ethnicity, smoking status, parity, diabetes, hypertensive disorder, preterm birth, fetal growth, and breastfeeding status (odds ratio [OR], 1.65; 95% confidence internal [CI], 1.18-2.32). Only 5.2% of children had whole-blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL or greater.

“Mothers with the highest red blood cell lead levels were older and multiparous, were more likely to be black and nonsmokers, had lower plasma folate levels and were more likely to have prepregnancy overweight/obesity and diabetes,” the authors reported.

The dose-response association did not lose significance when the researchers adjusted for children’s blood lead levels, maternal age, cesarean delivery, term births only, and black race. Nor did it change in a subset of children when the researchers adjusted for children’s physical activity.

The strength of the association increased when mothers also had a BMI greater than the average/healthy range. Children were more than four times more likely to be overweight or obese if their mothers were overweight or obese and had lead levels greater than 5.0 mcg/dL, compared with nonoverweight mothers with levels below 2 mcg/dL (OR, 4.24; 95% CI, 2.64-6.82).

Among children whose mothers were overweight/obese and had high blood lead levels, however, high folate levels appeared protective against obesity. These children had a 41% lower risk of being overweight or obese, compared with others in their group, if their mothers had plasma folate levels of at least 20 nmol/L (OR, 0.59 CI, 0.36-0.95; P = .03).

According to an invited commentary, “approximately 140,000 new chemicals and pesticides have appeared since 1950,” with “universal human exposure to approximately 5,000 of those,” wrote Marco Sanchez-Guerra, PhD, of the National Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City, and coauthors Andres Cardenas, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley, and Citlalli Osorio-Yáñez, PhD, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City. Yet fewer than half of those chemicals have been tested for safety or toxic effect, the editorialists wrote, and scientists know little of their potential reproductive harm.

Dr. Sanchez-Guerra, Dr. Cardenas, and Dr. Osorio-Yáñez agreed with the study authors that elevated lead exposures, especially from gasoline before lead was removed in the United States in 1975, may partly explain the current epidemic of obesity.

“Identifying preventable prenatal causes of obesity is a cornerstone in the fight against the obesity epidemic,” the editorialists said. While most recommendations center on changes to diet and physical activity, environmental factors during pregnancy could be involved in childhood obesity as well.

“The study by Wang et al. opens the door to new questions about whether adequate folate intake might modify the adverse effects of other chemical exposures,” they continued, noting other research suggesting a protective effect from folate against health effects of air pollution exposure. “These efforts could yield substantial public health benefits and represent novel tools in fighting the obesity epidemic,” they concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Neither the study authors nor the editorialists had industry financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Wang G et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912343. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12343; Sanchez-Guerra M et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1912334. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12334.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Higher teen pregnancy risk in girls with ADHD

Teenage girls with ADHD may be at greater risk of pregnancy than their unaffected peers, which suggests they may benefit from targeted interventions to prevent teen pregnancy.

A Swedish nationwide cohort study published in JAMA Network Open examined data from 384,103 nulliparous women and girls who gave birth between 2007-2014, of whom, 6,410 (1.7%) had received treatment for ADHD.

While the overall rate of teenage births was 3%, the rate among women and girls with ADHD was 15.3%, which represents a greater than sixfold higher odds of giving birth below the age of 20 years (odds ratio, 6.23; 95% confidence interval, 5.80-6.68).

“Becoming a mother at such early age is associated with long-term adverse outcomes for both women and their children,” wrote Charlotte Skoglund, PhD, of the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and coauthors. “Consequently, our findings argue for an improvement in the standard of care for women and girls with ADHD, including active efforts to prevent teenage pregnancies and address comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions.”

The study also found women and girls with ADHD were significantly more likely to be underweight (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.49) or have a body mass index greater than 40 kg/m2 (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.60-2.52) when compared with those without ADHD.

They were also six times more likely to smoke, were nearly seven times more likely to continue smoking into their third trimester of pregnancy, and had a 20-fold higher odds of alcohol and substance use disorder. Among individuals who had been diagnosed with ADHD, 7.6% continued to use stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medication during pregnancy, and 16.4% used antidepressants during pregnancy.

Psychiatric comorbidities were also significantly more common among individuals with ADHD in the year preceding pregnancy, compared with those without ADHD. The authors saw a 17-fold higher odds of receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, nearly 8-fold higher odds of a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, and 22-fold higher odds of being diagnosed with emotionally unstable personality disorder among women and girls with ADHD versus those without.

The authors commented that antenatal care should focus on trying to reduce such obstetric risk factors in these women, but also pointed out that ADHD in women and girls was still underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Commenting on the association between ADHD and teenage pregnancy, the authors noted that women and girls with ADHD may be less likely to receive adequate contraceptive counseling and less likely to access, respond to, and act on counseling. They may also experience more adverse effects from hormonal contraceptives.

While Swedish youth clinics enable easier and low-cost access to counseling and contraception, the authors called for greater collaboration between psychiatric care clinics and specialized youth clinics to provide adequate care for women and girls with ADHD.

Three authors declared advisory board positions, grants, personal fees, and speakers’ fees from the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Skoglund C et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12463

Teenage girls with ADHD may be at greater risk of pregnancy than their unaffected peers, which suggests they may benefit from targeted interventions to prevent teen pregnancy.

A Swedish nationwide cohort study published in JAMA Network Open examined data from 384,103 nulliparous women and girls who gave birth between 2007-2014, of whom, 6,410 (1.7%) had received treatment for ADHD.

While the overall rate of teenage births was 3%, the rate among women and girls with ADHD was 15.3%, which represents a greater than sixfold higher odds of giving birth below the age of 20 years (odds ratio, 6.23; 95% confidence interval, 5.80-6.68).

“Becoming a mother at such early age is associated with long-term adverse outcomes for both women and their children,” wrote Charlotte Skoglund, PhD, of the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and coauthors. “Consequently, our findings argue for an improvement in the standard of care for women and girls with ADHD, including active efforts to prevent teenage pregnancies and address comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions.”

The study also found women and girls with ADHD were significantly more likely to be underweight (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.49) or have a body mass index greater than 40 kg/m2 (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.60-2.52) when compared with those without ADHD.

They were also six times more likely to smoke, were nearly seven times more likely to continue smoking into their third trimester of pregnancy, and had a 20-fold higher odds of alcohol and substance use disorder. Among individuals who had been diagnosed with ADHD, 7.6% continued to use stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medication during pregnancy, and 16.4% used antidepressants during pregnancy.

Psychiatric comorbidities were also significantly more common among individuals with ADHD in the year preceding pregnancy, compared with those without ADHD. The authors saw a 17-fold higher odds of receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, nearly 8-fold higher odds of a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, and 22-fold higher odds of being diagnosed with emotionally unstable personality disorder among women and girls with ADHD versus those without.

The authors commented that antenatal care should focus on trying to reduce such obstetric risk factors in these women, but also pointed out that ADHD in women and girls was still underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Commenting on the association between ADHD and teenage pregnancy, the authors noted that women and girls with ADHD may be less likely to receive adequate contraceptive counseling and less likely to access, respond to, and act on counseling. They may also experience more adverse effects from hormonal contraceptives.

While Swedish youth clinics enable easier and low-cost access to counseling and contraception, the authors called for greater collaboration between psychiatric care clinics and specialized youth clinics to provide adequate care for women and girls with ADHD.

Three authors declared advisory board positions, grants, personal fees, and speakers’ fees from the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Skoglund C et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12463

Teenage girls with ADHD may be at greater risk of pregnancy than their unaffected peers, which suggests they may benefit from targeted interventions to prevent teen pregnancy.

A Swedish nationwide cohort study published in JAMA Network Open examined data from 384,103 nulliparous women and girls who gave birth between 2007-2014, of whom, 6,410 (1.7%) had received treatment for ADHD.

While the overall rate of teenage births was 3%, the rate among women and girls with ADHD was 15.3%, which represents a greater than sixfold higher odds of giving birth below the age of 20 years (odds ratio, 6.23; 95% confidence interval, 5.80-6.68).

“Becoming a mother at such early age is associated with long-term adverse outcomes for both women and their children,” wrote Charlotte Skoglund, PhD, of the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and coauthors. “Consequently, our findings argue for an improvement in the standard of care for women and girls with ADHD, including active efforts to prevent teenage pregnancies and address comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions.”

The study also found women and girls with ADHD were significantly more likely to be underweight (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.12-1.49) or have a body mass index greater than 40 kg/m2 (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.60-2.52) when compared with those without ADHD.

They were also six times more likely to smoke, were nearly seven times more likely to continue smoking into their third trimester of pregnancy, and had a 20-fold higher odds of alcohol and substance use disorder. Among individuals who had been diagnosed with ADHD, 7.6% continued to use stimulant and nonstimulant ADHD medication during pregnancy, and 16.4% used antidepressants during pregnancy.

Psychiatric comorbidities were also significantly more common among individuals with ADHD in the year preceding pregnancy, compared with those without ADHD. The authors saw a 17-fold higher odds of receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, nearly 8-fold higher odds of a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder, and 22-fold higher odds of being diagnosed with emotionally unstable personality disorder among women and girls with ADHD versus those without.

The authors commented that antenatal care should focus on trying to reduce such obstetric risk factors in these women, but also pointed out that ADHD in women and girls was still underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Commenting on the association between ADHD and teenage pregnancy, the authors noted that women and girls with ADHD may be less likely to receive adequate contraceptive counseling and less likely to access, respond to, and act on counseling. They may also experience more adverse effects from hormonal contraceptives.

While Swedish youth clinics enable easier and low-cost access to counseling and contraception, the authors called for greater collaboration between psychiatric care clinics and specialized youth clinics to provide adequate care for women and girls with ADHD.

Three authors declared advisory board positions, grants, personal fees, and speakers’ fees from the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Skoglund C et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Oct 2. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12463

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

NICUs admitting more normal-weight newborns

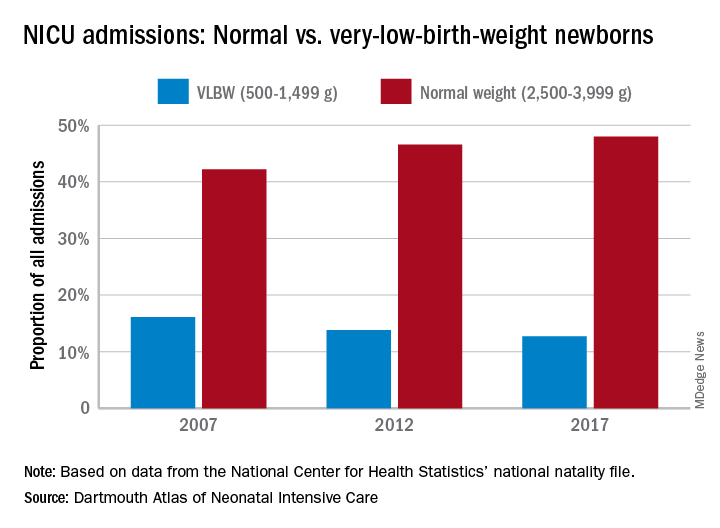

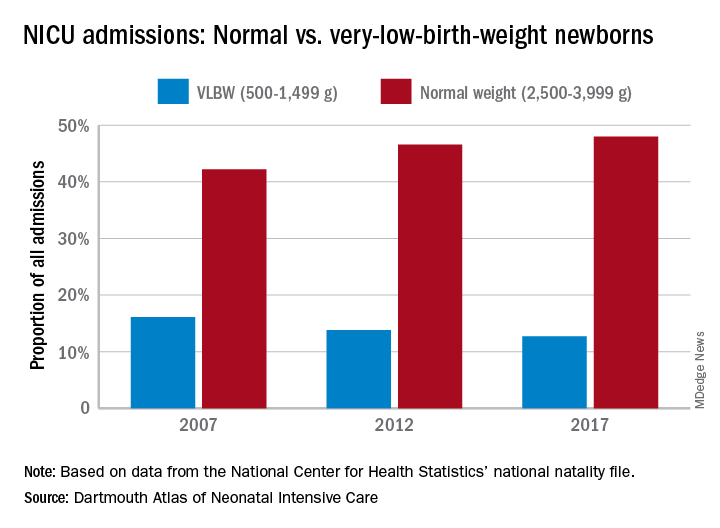

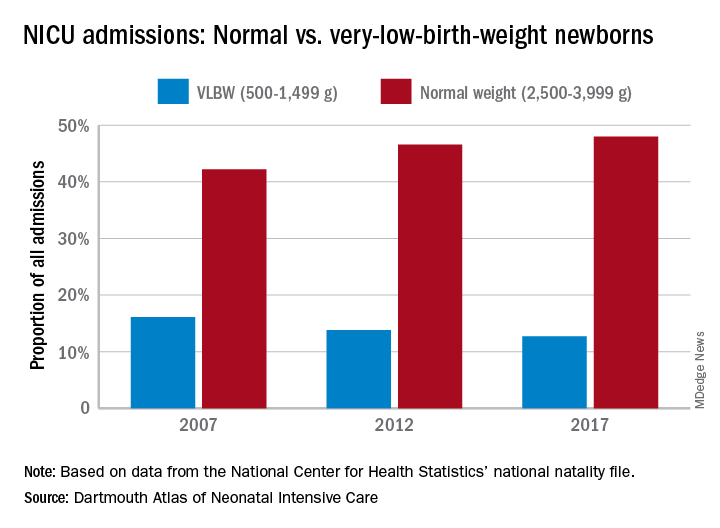

Almost half of the newborns admitted to U.S. neonatal intensive care units in 2017 were of normal birth weight, according to a new report from the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice.

The proportion of NICU admissions involving normal-weight (2,500-3,999 g) newborns increased from 42% in 2007 to 48% in 2017, investigators said in the Dartmouth Atlas of Neonatal Intensive Care. Over that same period, admissions of very-low-birth-weight (500-1,499 g) babies dropped from 16% to 13% of the total.

Those changes were part of a larger, longer-term trend. “The expansion of NICUs and beds in recent decades has been associated with changes in the newborn population receiving NICU care,” the investigators said in the report.

The number of NICU beds increased by 65% from 1995 to 2013, and the number of neonatologists rose by 75% from 1996 to 2013. “At the same time, ” they said in a written statement.

The increases in NICU and neonatologist supply, however, did not always follow the need for such care. Areas of the country with high rates of newborn prematurity, or of risk factors such as low maternal education levels or high cesarean section rates, do not have higher supplies of NICU beds or neonatologists, the researchers noted.

“We should not spare a dollar in providing the best care for newborns. But spending more doesn’t help infants if they could receive the care they need in a maternity unit or home with their mothers. It is very troubling that such a valuable and expensive health care resource is not distributed where it is needed,” said principal author David C. Goodman, MD, of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice in Lebanon, N.H.

Almost half of the newborns admitted to U.S. neonatal intensive care units in 2017 were of normal birth weight, according to a new report from the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice.

The proportion of NICU admissions involving normal-weight (2,500-3,999 g) newborns increased from 42% in 2007 to 48% in 2017, investigators said in the Dartmouth Atlas of Neonatal Intensive Care. Over that same period, admissions of very-low-birth-weight (500-1,499 g) babies dropped from 16% to 13% of the total.

Those changes were part of a larger, longer-term trend. “The expansion of NICUs and beds in recent decades has been associated with changes in the newborn population receiving NICU care,” the investigators said in the report.

The number of NICU beds increased by 65% from 1995 to 2013, and the number of neonatologists rose by 75% from 1996 to 2013. “At the same time, ” they said in a written statement.

The increases in NICU and neonatologist supply, however, did not always follow the need for such care. Areas of the country with high rates of newborn prematurity, or of risk factors such as low maternal education levels or high cesarean section rates, do not have higher supplies of NICU beds or neonatologists, the researchers noted.

“We should not spare a dollar in providing the best care for newborns. But spending more doesn’t help infants if they could receive the care they need in a maternity unit or home with their mothers. It is very troubling that such a valuable and expensive health care resource is not distributed where it is needed,” said principal author David C. Goodman, MD, of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice in Lebanon, N.H.

Almost half of the newborns admitted to U.S. neonatal intensive care units in 2017 were of normal birth weight, according to a new report from the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice.

The proportion of NICU admissions involving normal-weight (2,500-3,999 g) newborns increased from 42% in 2007 to 48% in 2017, investigators said in the Dartmouth Atlas of Neonatal Intensive Care. Over that same period, admissions of very-low-birth-weight (500-1,499 g) babies dropped from 16% to 13% of the total.

Those changes were part of a larger, longer-term trend. “The expansion of NICUs and beds in recent decades has been associated with changes in the newborn population receiving NICU care,” the investigators said in the report.

The number of NICU beds increased by 65% from 1995 to 2013, and the number of neonatologists rose by 75% from 1996 to 2013. “At the same time, ” they said in a written statement.

The increases in NICU and neonatologist supply, however, did not always follow the need for such care. Areas of the country with high rates of newborn prematurity, or of risk factors such as low maternal education levels or high cesarean section rates, do not have higher supplies of NICU beds or neonatologists, the researchers noted.