User login

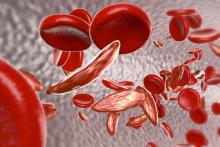

U.S. and African programs aim to improve understanding, treatment of sickle cell disease

Researchers are leading several programs designed to serve the sickle cell community in the United States and sub-Saharan Africa, officials at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) said during a recent webinar.

One program based in the United States is focused on building a registry for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) and conducting studies designed to improve SCD care. Another program involves building “an information-sharing network and patient-powered registry” in the United States.

The programs in sub-Saharan Africa were designed to establish a database of SCD patients, optimize the use of hydroxyurea in children with SCD, and aid genomic studies of SCD.

W. Keith Hoots, MD, director of the Division of Blood Diseases and Resources at NHLBI, began the webinar with an overview of the programs in sub-Saharan Africa. He described four programs with sites in nine countries (Angola, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda).

SPARCO and SADaCC

Dr. Hoots outlined the scope the Sickle Pan-African Research Consortium (SPARCO) and the Sickle Africa Data Coordinating Center (SADaCC), both part of the Sickle In Africa consortium.

A major goal of SPARCO and SADaCC is to create a Research Electronic Data Capture database that encompasses SCD patients in sub-Saharan Africa. As of April 2019, the database included 6,578 patients. The target is 13,000 patients.

Other goals of SPARCO and SADaCC are to “harmonize” SCD phenotype definitions and ontologies, create clinical guidelines for SCD management in sub-Saharan Africa, plan future cohort studies, and develop programs for newborn screening, infection prevention, and increased use of hydroxyurea.

“So far, they’re well along in establishing a registry and a database system,” Dr. Hoots said. “They’ve agreed on the database elements, phenotype definitions, and ontologies, they’ve developed some regionally appropriate clinical management guidelines, and they’ve begun skills development on the ground at all respective sites.”

REACH

Another program Dr. Hoots discussed is Realizing Effectiveness Across Continents With Hydroxyurea (REACH), a phase 1/2 pilot study of hydroxyurea in children (aged 1-10 years) with SCD in sub-Saharan Africa.

The goals of REACH are to determine the optimal dose of hydroxyurea in this population; teach African physicians how to administer hydroxyurea; assess the safety, feasibility, and benefits of hydroxyurea; study variability in response to hydroxyurea; gather data for the Research Electronic Data Capture database; and establish a research infrastructure for future collaborations.

Results from more than 600 children enrolled in REACH were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 10; 380[2]:121-31).

SickleGenAfrica

SickleGenAfrica is part of the H3Africa consortium and aims to “build capacity for genomic research in Africa,” Dr. Hoots said.

Under this program, researchers will conduct three studies to test the hypothesis that genetic variation affects the defense against hemolysis and organ damage in patients with SCD. The researchers will study existing cohorts of SCD patients including children and adults.

Other goals of SickleGenAfrica are to establish a molecular hematology and sickle cell mouse core, an SCD biorepository core, a bioinformatics core, and an administrative core for the coordination of activities. The program will also be used to train “future science leaders” in SCD research, Dr. Hoots said.

SCDIC

Cheryl Anne Boyce, PhD, chief of the Implementation Science Branch at the Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science at NHLBI, discussed the United States–based Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC).

“The goals of the consortium are to develop a registry in collaboration with other centers and the NHLBI, as well as a needs-based community assessment of the barriers to care for subjects with sickle cell disease,” Dr. Boyce said. “We also wanted to design implementation research studies that address the identified barriers to care.”

Dr. Boyce said the SCDIC’s registry is open to patients aged 15-45 years who have a confirmed SCD diagnosis, speak English, and are able to consent to and complete a survey. The registry has enrolled almost 2,400 patients from eight centers over 18 months.

The SCDIC has also performed a needs assessment that prompted the development of three implementation research studies. The first study involves using mobile health interventions to, ideally, increase patient adherence to hydroxyurea and improve provider knowledge of hydroxyurea.

With the second study, researchers aim to improve the care of SCD patients in the emergency department by using an inpatient portal. The goals of the third study are to establish a standard definition for unaffiliated patients, conduct a needs assessment for this group, and develop an intervention that can provide these patients with guideline-based SCD care.

Get Connected

Kim Smith-Whitley, MD, director of the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a board member of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA), described Get Connected, “an information-sharing network and patient-powered registry” created by SCDAA.

Dr. Smith-Whitley said one purpose of Get Connected is to provide a network that facilitates “the distribution of information related to clinical care, research, health services, health policy, and advocacy.”

The network is open to families living with SCD and sickle cell trait, SCDAA member organizations, health care providers, clinical researchers, and community-based organizations.

Get Connected also includes a registry for SCD patients that stores information on their diagnosis and treatment, as well as online communities that can be used to share information and provide psychosocial support.

Thus far, Get Connected has enrolled 6,329 individuals. This includes 5,100 children and adults with SCD, 652 children and adults with sickle cell trait, and 577 nonpatients.

The webinar presenters did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

Researchers are leading several programs designed to serve the sickle cell community in the United States and sub-Saharan Africa, officials at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) said during a recent webinar.

One program based in the United States is focused on building a registry for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) and conducting studies designed to improve SCD care. Another program involves building “an information-sharing network and patient-powered registry” in the United States.

The programs in sub-Saharan Africa were designed to establish a database of SCD patients, optimize the use of hydroxyurea in children with SCD, and aid genomic studies of SCD.

W. Keith Hoots, MD, director of the Division of Blood Diseases and Resources at NHLBI, began the webinar with an overview of the programs in sub-Saharan Africa. He described four programs with sites in nine countries (Angola, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda).

SPARCO and SADaCC

Dr. Hoots outlined the scope the Sickle Pan-African Research Consortium (SPARCO) and the Sickle Africa Data Coordinating Center (SADaCC), both part of the Sickle In Africa consortium.

A major goal of SPARCO and SADaCC is to create a Research Electronic Data Capture database that encompasses SCD patients in sub-Saharan Africa. As of April 2019, the database included 6,578 patients. The target is 13,000 patients.

Other goals of SPARCO and SADaCC are to “harmonize” SCD phenotype definitions and ontologies, create clinical guidelines for SCD management in sub-Saharan Africa, plan future cohort studies, and develop programs for newborn screening, infection prevention, and increased use of hydroxyurea.

“So far, they’re well along in establishing a registry and a database system,” Dr. Hoots said. “They’ve agreed on the database elements, phenotype definitions, and ontologies, they’ve developed some regionally appropriate clinical management guidelines, and they’ve begun skills development on the ground at all respective sites.”

REACH

Another program Dr. Hoots discussed is Realizing Effectiveness Across Continents With Hydroxyurea (REACH), a phase 1/2 pilot study of hydroxyurea in children (aged 1-10 years) with SCD in sub-Saharan Africa.

The goals of REACH are to determine the optimal dose of hydroxyurea in this population; teach African physicians how to administer hydroxyurea; assess the safety, feasibility, and benefits of hydroxyurea; study variability in response to hydroxyurea; gather data for the Research Electronic Data Capture database; and establish a research infrastructure for future collaborations.

Results from more than 600 children enrolled in REACH were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 10; 380[2]:121-31).

SickleGenAfrica

SickleGenAfrica is part of the H3Africa consortium and aims to “build capacity for genomic research in Africa,” Dr. Hoots said.

Under this program, researchers will conduct three studies to test the hypothesis that genetic variation affects the defense against hemolysis and organ damage in patients with SCD. The researchers will study existing cohorts of SCD patients including children and adults.

Other goals of SickleGenAfrica are to establish a molecular hematology and sickle cell mouse core, an SCD biorepository core, a bioinformatics core, and an administrative core for the coordination of activities. The program will also be used to train “future science leaders” in SCD research, Dr. Hoots said.

SCDIC

Cheryl Anne Boyce, PhD, chief of the Implementation Science Branch at the Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science at NHLBI, discussed the United States–based Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC).

“The goals of the consortium are to develop a registry in collaboration with other centers and the NHLBI, as well as a needs-based community assessment of the barriers to care for subjects with sickle cell disease,” Dr. Boyce said. “We also wanted to design implementation research studies that address the identified barriers to care.”

Dr. Boyce said the SCDIC’s registry is open to patients aged 15-45 years who have a confirmed SCD diagnosis, speak English, and are able to consent to and complete a survey. The registry has enrolled almost 2,400 patients from eight centers over 18 months.

The SCDIC has also performed a needs assessment that prompted the development of three implementation research studies. The first study involves using mobile health interventions to, ideally, increase patient adherence to hydroxyurea and improve provider knowledge of hydroxyurea.

With the second study, researchers aim to improve the care of SCD patients in the emergency department by using an inpatient portal. The goals of the third study are to establish a standard definition for unaffiliated patients, conduct a needs assessment for this group, and develop an intervention that can provide these patients with guideline-based SCD care.

Get Connected

Kim Smith-Whitley, MD, director of the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a board member of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA), described Get Connected, “an information-sharing network and patient-powered registry” created by SCDAA.

Dr. Smith-Whitley said one purpose of Get Connected is to provide a network that facilitates “the distribution of information related to clinical care, research, health services, health policy, and advocacy.”

The network is open to families living with SCD and sickle cell trait, SCDAA member organizations, health care providers, clinical researchers, and community-based organizations.

Get Connected also includes a registry for SCD patients that stores information on their diagnosis and treatment, as well as online communities that can be used to share information and provide psychosocial support.

Thus far, Get Connected has enrolled 6,329 individuals. This includes 5,100 children and adults with SCD, 652 children and adults with sickle cell trait, and 577 nonpatients.

The webinar presenters did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

Researchers are leading several programs designed to serve the sickle cell community in the United States and sub-Saharan Africa, officials at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) said during a recent webinar.

One program based in the United States is focused on building a registry for patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) and conducting studies designed to improve SCD care. Another program involves building “an information-sharing network and patient-powered registry” in the United States.

The programs in sub-Saharan Africa were designed to establish a database of SCD patients, optimize the use of hydroxyurea in children with SCD, and aid genomic studies of SCD.

W. Keith Hoots, MD, director of the Division of Blood Diseases and Resources at NHLBI, began the webinar with an overview of the programs in sub-Saharan Africa. He described four programs with sites in nine countries (Angola, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda).

SPARCO and SADaCC

Dr. Hoots outlined the scope the Sickle Pan-African Research Consortium (SPARCO) and the Sickle Africa Data Coordinating Center (SADaCC), both part of the Sickle In Africa consortium.

A major goal of SPARCO and SADaCC is to create a Research Electronic Data Capture database that encompasses SCD patients in sub-Saharan Africa. As of April 2019, the database included 6,578 patients. The target is 13,000 patients.

Other goals of SPARCO and SADaCC are to “harmonize” SCD phenotype definitions and ontologies, create clinical guidelines for SCD management in sub-Saharan Africa, plan future cohort studies, and develop programs for newborn screening, infection prevention, and increased use of hydroxyurea.

“So far, they’re well along in establishing a registry and a database system,” Dr. Hoots said. “They’ve agreed on the database elements, phenotype definitions, and ontologies, they’ve developed some regionally appropriate clinical management guidelines, and they’ve begun skills development on the ground at all respective sites.”

REACH

Another program Dr. Hoots discussed is Realizing Effectiveness Across Continents With Hydroxyurea (REACH), a phase 1/2 pilot study of hydroxyurea in children (aged 1-10 years) with SCD in sub-Saharan Africa.

The goals of REACH are to determine the optimal dose of hydroxyurea in this population; teach African physicians how to administer hydroxyurea; assess the safety, feasibility, and benefits of hydroxyurea; study variability in response to hydroxyurea; gather data for the Research Electronic Data Capture database; and establish a research infrastructure for future collaborations.

Results from more than 600 children enrolled in REACH were presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 10; 380[2]:121-31).

SickleGenAfrica

SickleGenAfrica is part of the H3Africa consortium and aims to “build capacity for genomic research in Africa,” Dr. Hoots said.

Under this program, researchers will conduct three studies to test the hypothesis that genetic variation affects the defense against hemolysis and organ damage in patients with SCD. The researchers will study existing cohorts of SCD patients including children and adults.

Other goals of SickleGenAfrica are to establish a molecular hematology and sickle cell mouse core, an SCD biorepository core, a bioinformatics core, and an administrative core for the coordination of activities. The program will also be used to train “future science leaders” in SCD research, Dr. Hoots said.

SCDIC

Cheryl Anne Boyce, PhD, chief of the Implementation Science Branch at the Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science at NHLBI, discussed the United States–based Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC).

“The goals of the consortium are to develop a registry in collaboration with other centers and the NHLBI, as well as a needs-based community assessment of the barriers to care for subjects with sickle cell disease,” Dr. Boyce said. “We also wanted to design implementation research studies that address the identified barriers to care.”

Dr. Boyce said the SCDIC’s registry is open to patients aged 15-45 years who have a confirmed SCD diagnosis, speak English, and are able to consent to and complete a survey. The registry has enrolled almost 2,400 patients from eight centers over 18 months.

The SCDIC has also performed a needs assessment that prompted the development of three implementation research studies. The first study involves using mobile health interventions to, ideally, increase patient adherence to hydroxyurea and improve provider knowledge of hydroxyurea.

With the second study, researchers aim to improve the care of SCD patients in the emergency department by using an inpatient portal. The goals of the third study are to establish a standard definition for unaffiliated patients, conduct a needs assessment for this group, and develop an intervention that can provide these patients with guideline-based SCD care.

Get Connected

Kim Smith-Whitley, MD, director of the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a board member of the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America (SCDAA), described Get Connected, “an information-sharing network and patient-powered registry” created by SCDAA.

Dr. Smith-Whitley said one purpose of Get Connected is to provide a network that facilitates “the distribution of information related to clinical care, research, health services, health policy, and advocacy.”

The network is open to families living with SCD and sickle cell trait, SCDAA member organizations, health care providers, clinical researchers, and community-based organizations.

Get Connected also includes a registry for SCD patients that stores information on their diagnosis and treatment, as well as online communities that can be used to share information and provide psychosocial support.

Thus far, Get Connected has enrolled 6,329 individuals. This includes 5,100 children and adults with SCD, 652 children and adults with sickle cell trait, and 577 nonpatients.

The webinar presenters did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

Pediatric HSCT recipients still risking sunburn

Young people who have received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) are more likely to wear hats, sunscreen and other sun protection, but still intentionally tan and experience sunburn at the same rate as their peers, new research suggests.

In a survey‐based, cross‐sectional cohort study, researchers compared sun-protection behaviors and sun exposure in 85 children aged 21 years and younger who had undergone HSCT and 85 age-, sex-, and skin type–matched controls. The findings were published in Pediatric Dermatology.

HSCT recipients have a higher risk of long-term complications such as skin cancer, for which sun exposure is a major modifiable environmental risk factor.

“Therefore, consistent sun avoidance and protection as well as regular dermatologic evaluations are important for HSCT recipients,” wrote Edward B. Li, PhD, from Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors.

The survey found no significant difference between the transplant and control group in the amount of intentional sun exposure, such as the amount of time spent outside on weekdays and weekends during the peak sun intensity hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. More than one in five transplant recipients (21.2%) reported spending at least 3 hours a day outside between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. on weekdays, as did 36.5% of transplant recipients on weekends.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in terms of time spent tanning, either in the sun or in a tanning bed. Additionally, a similar number of transplant recipients and controls experienced one or more red or painful sunburns in the past year (25.9% vs. 27.1%).

However, transplant patients did practice better sun protection behaviors than did the control group, with 60% reporting that they always wore sunscreen, compared with 29.4% of controls. The transplant recipients were also significantly more likely to wear sunglasses and a hat and to stay in the shade or use an umbrella.

“While these data may reflect that HSCT patients are not practicing adequate sun avoidance, it may also suggest that these long‐term survivors are able to enjoy being outdoors as much as their peers and have a similar desire to have a tanned appearance,” the researchers wrote. “While a healthy and active lifestyle should be encouraged for all children, our results emphasize the need for pediatric HSCT survivors to be educated on their increased risk for UV‐related skin cancers, counseled on avoidance of intentional tanning, and advised on the importance of sun protection behaviors in an effort to improve long-term outcomes.”

The researchers noted that transplant recipients were significantly more likely to have had a full body skin exam from a health care professional than were individuals in the control group (61.2% vs. 4.7%) and were more likely to have done a self-check or been checked by a partner in the previous year.

The study was supported by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, the Dermatology Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. One author declared a financial interest in a company developing a dermatological product. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Li EB et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 13. doi: 10.1111/pde.13984.

Young people who have received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) are more likely to wear hats, sunscreen and other sun protection, but still intentionally tan and experience sunburn at the same rate as their peers, new research suggests.

In a survey‐based, cross‐sectional cohort study, researchers compared sun-protection behaviors and sun exposure in 85 children aged 21 years and younger who had undergone HSCT and 85 age-, sex-, and skin type–matched controls. The findings were published in Pediatric Dermatology.

HSCT recipients have a higher risk of long-term complications such as skin cancer, for which sun exposure is a major modifiable environmental risk factor.

“Therefore, consistent sun avoidance and protection as well as regular dermatologic evaluations are important for HSCT recipients,” wrote Edward B. Li, PhD, from Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors.

The survey found no significant difference between the transplant and control group in the amount of intentional sun exposure, such as the amount of time spent outside on weekdays and weekends during the peak sun intensity hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. More than one in five transplant recipients (21.2%) reported spending at least 3 hours a day outside between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. on weekdays, as did 36.5% of transplant recipients on weekends.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in terms of time spent tanning, either in the sun or in a tanning bed. Additionally, a similar number of transplant recipients and controls experienced one or more red or painful sunburns in the past year (25.9% vs. 27.1%).

However, transplant patients did practice better sun protection behaviors than did the control group, with 60% reporting that they always wore sunscreen, compared with 29.4% of controls. The transplant recipients were also significantly more likely to wear sunglasses and a hat and to stay in the shade or use an umbrella.

“While these data may reflect that HSCT patients are not practicing adequate sun avoidance, it may also suggest that these long‐term survivors are able to enjoy being outdoors as much as their peers and have a similar desire to have a tanned appearance,” the researchers wrote. “While a healthy and active lifestyle should be encouraged for all children, our results emphasize the need for pediatric HSCT survivors to be educated on their increased risk for UV‐related skin cancers, counseled on avoidance of intentional tanning, and advised on the importance of sun protection behaviors in an effort to improve long-term outcomes.”

The researchers noted that transplant recipients were significantly more likely to have had a full body skin exam from a health care professional than were individuals in the control group (61.2% vs. 4.7%) and were more likely to have done a self-check or been checked by a partner in the previous year.

The study was supported by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, the Dermatology Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. One author declared a financial interest in a company developing a dermatological product. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Li EB et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 13. doi: 10.1111/pde.13984.

Young people who have received allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) are more likely to wear hats, sunscreen and other sun protection, but still intentionally tan and experience sunburn at the same rate as their peers, new research suggests.

In a survey‐based, cross‐sectional cohort study, researchers compared sun-protection behaviors and sun exposure in 85 children aged 21 years and younger who had undergone HSCT and 85 age-, sex-, and skin type–matched controls. The findings were published in Pediatric Dermatology.

HSCT recipients have a higher risk of long-term complications such as skin cancer, for which sun exposure is a major modifiable environmental risk factor.

“Therefore, consistent sun avoidance and protection as well as regular dermatologic evaluations are important for HSCT recipients,” wrote Edward B. Li, PhD, from Harvard Medical School, Boston, and coauthors.

The survey found no significant difference between the transplant and control group in the amount of intentional sun exposure, such as the amount of time spent outside on weekdays and weekends during the peak sun intensity hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. More than one in five transplant recipients (21.2%) reported spending at least 3 hours a day outside between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. on weekdays, as did 36.5% of transplant recipients on weekends.

There were also no significant differences between the two groups in terms of time spent tanning, either in the sun or in a tanning bed. Additionally, a similar number of transplant recipients and controls experienced one or more red or painful sunburns in the past year (25.9% vs. 27.1%).

However, transplant patients did practice better sun protection behaviors than did the control group, with 60% reporting that they always wore sunscreen, compared with 29.4% of controls. The transplant recipients were also significantly more likely to wear sunglasses and a hat and to stay in the shade or use an umbrella.

“While these data may reflect that HSCT patients are not practicing adequate sun avoidance, it may also suggest that these long‐term survivors are able to enjoy being outdoors as much as their peers and have a similar desire to have a tanned appearance,” the researchers wrote. “While a healthy and active lifestyle should be encouraged for all children, our results emphasize the need for pediatric HSCT survivors to be educated on their increased risk for UV‐related skin cancers, counseled on avoidance of intentional tanning, and advised on the importance of sun protection behaviors in an effort to improve long-term outcomes.”

The researchers noted that transplant recipients were significantly more likely to have had a full body skin exam from a health care professional than were individuals in the control group (61.2% vs. 4.7%) and were more likely to have done a self-check or been checked by a partner in the previous year.

The study was supported by the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, the Dermatology Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation. One author declared a financial interest in a company developing a dermatological product. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Li EB et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Aug 13. doi: 10.1111/pde.13984.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Wrong cuff size throws off pediatric BP by 5 mm Hg

NEW ORLEANS – according to investigators from Columbia University in New York.

There are five cuff sizes in pediatrics, depending on a child’s arm circumference. Ideally, it’s measured beforehand so the right cuff size is used, but that doesn’t always happen in everyday practice.

Sometimes, clinicians just estimate arm size before choosing a cuff or opt for the medium-sized cuff in most kids; other times, the correct size has gone missing, said lead investigator Ruchi Gupta Mahajan, MD, a pediatric nephrology fellow at Columbia.

For those situations, she and her colleagues wanted to quantify how much the wrong cuff size throws off blood pressure readings in children, something that’s been done before in adult medicine, but not in pediatrics.

The idea was to give clinicians a decent estimate of true blood pressure even when the cuff isn’t quite right, something that’s particularly important with an increasing emphasis on catching hypertension as early as possible in children, she said.

After her subjects sat quietly for 10 minutes, Dr. Mahajan took automated blood pressure readings on 137 children; once with the right cuff size, once with a cuff one size too small, and once with a cuff one size too big, with a minute apart between readings.

The children were aged 4-12 years old and were in the office for wellness visits. None of them had heart or kidney disease, and none were on steroids or any other medications that affect blood pressure. There were a few more boys than girls, and almost all the children were Hispanic.

Overall, systolic blood pressure was an average of 5 mm Hg less with the larger cuff and 5 mm Hg more with the smaller cuff. The finding was the same in both girls and boys, and it held across age groups and in under, over, and normal weight children.

“I was really surprised there was no difference between ages, 4-12 years of age, its just a single number: 5. [Even] if [you] don’t have the appropriate cuff size,” the finding means that it’s still possible to have a good estimate of blood pressure, Dr. Mahajan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association (AHA) Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Meanwhile, cuff size didn’t have any statistically significant effect on diastolic pressure.

There was no outside funding for the study and Dr. Mahajan reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mahajan RG et al. Joint Hypertension 2019, Abstract P182.

NEW ORLEANS – according to investigators from Columbia University in New York.

There are five cuff sizes in pediatrics, depending on a child’s arm circumference. Ideally, it’s measured beforehand so the right cuff size is used, but that doesn’t always happen in everyday practice.

Sometimes, clinicians just estimate arm size before choosing a cuff or opt for the medium-sized cuff in most kids; other times, the correct size has gone missing, said lead investigator Ruchi Gupta Mahajan, MD, a pediatric nephrology fellow at Columbia.

For those situations, she and her colleagues wanted to quantify how much the wrong cuff size throws off blood pressure readings in children, something that’s been done before in adult medicine, but not in pediatrics.

The idea was to give clinicians a decent estimate of true blood pressure even when the cuff isn’t quite right, something that’s particularly important with an increasing emphasis on catching hypertension as early as possible in children, she said.

After her subjects sat quietly for 10 minutes, Dr. Mahajan took automated blood pressure readings on 137 children; once with the right cuff size, once with a cuff one size too small, and once with a cuff one size too big, with a minute apart between readings.

The children were aged 4-12 years old and were in the office for wellness visits. None of them had heart or kidney disease, and none were on steroids or any other medications that affect blood pressure. There were a few more boys than girls, and almost all the children were Hispanic.

Overall, systolic blood pressure was an average of 5 mm Hg less with the larger cuff and 5 mm Hg more with the smaller cuff. The finding was the same in both girls and boys, and it held across age groups and in under, over, and normal weight children.

“I was really surprised there was no difference between ages, 4-12 years of age, its just a single number: 5. [Even] if [you] don’t have the appropriate cuff size,” the finding means that it’s still possible to have a good estimate of blood pressure, Dr. Mahajan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association (AHA) Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Meanwhile, cuff size didn’t have any statistically significant effect on diastolic pressure.

There was no outside funding for the study and Dr. Mahajan reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mahajan RG et al. Joint Hypertension 2019, Abstract P182.

NEW ORLEANS – according to investigators from Columbia University in New York.

There are five cuff sizes in pediatrics, depending on a child’s arm circumference. Ideally, it’s measured beforehand so the right cuff size is used, but that doesn’t always happen in everyday practice.

Sometimes, clinicians just estimate arm size before choosing a cuff or opt for the medium-sized cuff in most kids; other times, the correct size has gone missing, said lead investigator Ruchi Gupta Mahajan, MD, a pediatric nephrology fellow at Columbia.

For those situations, she and her colleagues wanted to quantify how much the wrong cuff size throws off blood pressure readings in children, something that’s been done before in adult medicine, but not in pediatrics.

The idea was to give clinicians a decent estimate of true blood pressure even when the cuff isn’t quite right, something that’s particularly important with an increasing emphasis on catching hypertension as early as possible in children, she said.

After her subjects sat quietly for 10 minutes, Dr. Mahajan took automated blood pressure readings on 137 children; once with the right cuff size, once with a cuff one size too small, and once with a cuff one size too big, with a minute apart between readings.

The children were aged 4-12 years old and were in the office for wellness visits. None of them had heart or kidney disease, and none were on steroids or any other medications that affect blood pressure. There were a few more boys than girls, and almost all the children were Hispanic.

Overall, systolic blood pressure was an average of 5 mm Hg less with the larger cuff and 5 mm Hg more with the smaller cuff. The finding was the same in both girls and boys, and it held across age groups and in under, over, and normal weight children.

“I was really surprised there was no difference between ages, 4-12 years of age, its just a single number: 5. [Even] if [you] don’t have the appropriate cuff size,” the finding means that it’s still possible to have a good estimate of blood pressure, Dr. Mahajan said at the joint scientific sessions of the American Heart Association (AHA) Council on Hypertension, AHA Council on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, and American Society of Hypertension.

Meanwhile, cuff size didn’t have any statistically significant effect on diastolic pressure.

There was no outside funding for the study and Dr. Mahajan reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Mahajan RG et al. Joint Hypertension 2019, Abstract P182.

REPORTING FROM JOINT HYPERTENSION 2019

No ‘one size fits all’ approach to managing severe pediatric psoriasis

AUSTIN, TEX. – The way Kelly M. Cordoro sees it, the most for which patient.

“You can look up the dosing and frequency of these drugs; all of that’s available,” she said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “But how do we think about which drug for which patient? What are the considerations?”

Dr. Cordoro, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, described psoriasis as an autoamplifying inflammatory cascade involving innate and adaptive immunity and noted that various components of that cascade represent treatment targets. “We don’t have a true comprehension of the pathophysiology of psoriasis, but as we learn the pathways, we’re targeting them,” she said. “You can target keratinocyte proliferation with drugs like retinoids and phototherapy. You can broadly target T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and phototherapy. The newer drugs target the cytokine milieu, including TNF [tumor necrosis factor]–alpha, IL [interleukin]–17A, IL-12, and IL-23.”

There is no one right answer for which drug to prescribe, she continued, except in the cases of certain comorbidities, contraindications, and genetic variants. “For example, if a patient has psoriatic arthritis, then you have methotrexate and all of the biologics that might be disease modifying,” she said. “If a patient has inflammatory bowel disease, it’s critical to know that IL-17 inhibitors will flare that disease, but anti-TNF and IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors are okay. If a patient has liver and kidney disease, you want to avoid methotrexate and cyclosporine. If there’s a female of childbearing potential you want to be very cautious with using retinoids. I think the harder question for us is, How about the rest of the patients?”

In addition to a drug’s mechanism of action, patient- and family-related factors play a role in deciding which agent to use. For example, does the patient prefer an oral or an injectable agent? Is the patient able to travel to a phototherapy center? Is it feasible for the family to manage visits for lab work and direct clinical monitoring? Does the family have a high level of health literacy and are you communicating with them in ways that facilitate shared decision making?

“The best way to choose a systemic therapy is to develop an individualized assessment of overall disease burden,” said Dr. Cordoro, who is also division chief of pediatric dermatology at UCSF. “Include psychological burden and subjective data in addition to objective measures like body surface area. Look for triggers. Infants are more commonly affected by viral infections and, in a subset, monogenic forms of psoriasis such as deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist [DIRA]. In general, we try to take a conservative approach in the developing child. As children hit early adolescence and become post pubertal, you have to start thinking about the psychosocial impact [of psoriasis], and we have to start treating patients with the consideration that chronic uncontrolled inflammation can potentially lead to comorbidities down the road. We see this in adults with severe psoriasis and early onset cardiovascular disease, the so-called psoriatic march from chronic inflammation to cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Cordoro advises clinicians to rethink the conventional “therapeutic ladder” concept and embrace the idea of “finding the right tool for the job right now.” If a patient presents with a flare from a known trigger such as a strep infection, “maybe you want to treat with something more conservative,” she said. “Once you treat, and if the trigger has been managed, they might be better. But some patients will need the most aggressive treatment right out of the gate.”

Tried and true systemic therapies for psoriasis include methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and phototherapy, but none is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children. “These drugs have decades of experience behind them,” Dr. Cordoro said. “Methotrexate is slow to start but has a sustained profile, so if you can get the patient to respond, that response tends to persist. Methotrexate also prevents the formation of antidrug antibodies, which is important if you are considering use of a biologic agent later on.”

Cyclosporine is best if you need a rapid rescue drug to get the disease under control before moving on to other options. “One in four patients relapse once cyclosporine is discontinued, so the benefit may not be as sustained as with methotrexate,” she said. “Acitretin is a really nice choice when you can’t or don’t want to immunosuppress the patient, and phototherapy is good if you can get it. The advantages of systemic therapies are that they’re easy on, easy off, and you can combine medications in severe situations. Almost all of these drugs can be combined with another, with few exceptions. I would caution that over immunosuppression is the biggest risk ... so this must be done carefully and only when necessary.”

Biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors and IL-12/23 inhibitors are playing an increasing role in pediatric psoriasis. They can be expensive and difficult for some insurance plans to cover, but offer the convenience of better efficacy and less frequent lab monitoring than conventional systemics. In the United States, etanercept and ustekinumab are approved for moderate to severe pediatric plaque psoriasis in patients as young as age 4 and 12 years, respectively. TNF inhibitors have accumulated the most data in children, while data are accumulating in trials of IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors, and PDE4 inhibitors.

“These drugs have reassuring safety profiles; low rates of infection and adverse reactions,” Dr. Cordoro said of biologic agents. “They’ve changed the landscape completely because now the expectation is complete or near-complete clearance. In contrast to the systemic agents, which may be started and stopped repeatedly, you need to think about continuous therapy, because these drugs are immunogenic,” she noted. “Whether antibodies against them become neutralizing or not is a different case. If a patient does have antibodies, it does not mean you have to stop the drug. Dose escalation can help. Increasing frequency of use of the drug can help, but patients will develop antibodies and it may result in loss of efficacy or reactions to the drug,” she added.

“When you’re thinking about using a biologic agent, think about patients who are chronic, moderate to severe, and who will need more long-term therapy. Most importantly, treatment should be individualized, as there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

Dr. Cordoro disclosed that she is a member of the Celgene Corporation Scientific Steering Committee.

AUSTIN, TEX. – The way Kelly M. Cordoro sees it, the most for which patient.

“You can look up the dosing and frequency of these drugs; all of that’s available,” she said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “But how do we think about which drug for which patient? What are the considerations?”

Dr. Cordoro, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, described psoriasis as an autoamplifying inflammatory cascade involving innate and adaptive immunity and noted that various components of that cascade represent treatment targets. “We don’t have a true comprehension of the pathophysiology of psoriasis, but as we learn the pathways, we’re targeting them,” she said. “You can target keratinocyte proliferation with drugs like retinoids and phototherapy. You can broadly target T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and phototherapy. The newer drugs target the cytokine milieu, including TNF [tumor necrosis factor]–alpha, IL [interleukin]–17A, IL-12, and IL-23.”

There is no one right answer for which drug to prescribe, she continued, except in the cases of certain comorbidities, contraindications, and genetic variants. “For example, if a patient has psoriatic arthritis, then you have methotrexate and all of the biologics that might be disease modifying,” she said. “If a patient has inflammatory bowel disease, it’s critical to know that IL-17 inhibitors will flare that disease, but anti-TNF and IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors are okay. If a patient has liver and kidney disease, you want to avoid methotrexate and cyclosporine. If there’s a female of childbearing potential you want to be very cautious with using retinoids. I think the harder question for us is, How about the rest of the patients?”

In addition to a drug’s mechanism of action, patient- and family-related factors play a role in deciding which agent to use. For example, does the patient prefer an oral or an injectable agent? Is the patient able to travel to a phototherapy center? Is it feasible for the family to manage visits for lab work and direct clinical monitoring? Does the family have a high level of health literacy and are you communicating with them in ways that facilitate shared decision making?

“The best way to choose a systemic therapy is to develop an individualized assessment of overall disease burden,” said Dr. Cordoro, who is also division chief of pediatric dermatology at UCSF. “Include psychological burden and subjective data in addition to objective measures like body surface area. Look for triggers. Infants are more commonly affected by viral infections and, in a subset, monogenic forms of psoriasis such as deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist [DIRA]. In general, we try to take a conservative approach in the developing child. As children hit early adolescence and become post pubertal, you have to start thinking about the psychosocial impact [of psoriasis], and we have to start treating patients with the consideration that chronic uncontrolled inflammation can potentially lead to comorbidities down the road. We see this in adults with severe psoriasis and early onset cardiovascular disease, the so-called psoriatic march from chronic inflammation to cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Cordoro advises clinicians to rethink the conventional “therapeutic ladder” concept and embrace the idea of “finding the right tool for the job right now.” If a patient presents with a flare from a known trigger such as a strep infection, “maybe you want to treat with something more conservative,” she said. “Once you treat, and if the trigger has been managed, they might be better. But some patients will need the most aggressive treatment right out of the gate.”

Tried and true systemic therapies for psoriasis include methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and phototherapy, but none is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children. “These drugs have decades of experience behind them,” Dr. Cordoro said. “Methotrexate is slow to start but has a sustained profile, so if you can get the patient to respond, that response tends to persist. Methotrexate also prevents the formation of antidrug antibodies, which is important if you are considering use of a biologic agent later on.”

Cyclosporine is best if you need a rapid rescue drug to get the disease under control before moving on to other options. “One in four patients relapse once cyclosporine is discontinued, so the benefit may not be as sustained as with methotrexate,” she said. “Acitretin is a really nice choice when you can’t or don’t want to immunosuppress the patient, and phototherapy is good if you can get it. The advantages of systemic therapies are that they’re easy on, easy off, and you can combine medications in severe situations. Almost all of these drugs can be combined with another, with few exceptions. I would caution that over immunosuppression is the biggest risk ... so this must be done carefully and only when necessary.”

Biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors and IL-12/23 inhibitors are playing an increasing role in pediatric psoriasis. They can be expensive and difficult for some insurance plans to cover, but offer the convenience of better efficacy and less frequent lab monitoring than conventional systemics. In the United States, etanercept and ustekinumab are approved for moderate to severe pediatric plaque psoriasis in patients as young as age 4 and 12 years, respectively. TNF inhibitors have accumulated the most data in children, while data are accumulating in trials of IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors, and PDE4 inhibitors.

“These drugs have reassuring safety profiles; low rates of infection and adverse reactions,” Dr. Cordoro said of biologic agents. “They’ve changed the landscape completely because now the expectation is complete or near-complete clearance. In contrast to the systemic agents, which may be started and stopped repeatedly, you need to think about continuous therapy, because these drugs are immunogenic,” she noted. “Whether antibodies against them become neutralizing or not is a different case. If a patient does have antibodies, it does not mean you have to stop the drug. Dose escalation can help. Increasing frequency of use of the drug can help, but patients will develop antibodies and it may result in loss of efficacy or reactions to the drug,” she added.

“When you’re thinking about using a biologic agent, think about patients who are chronic, moderate to severe, and who will need more long-term therapy. Most importantly, treatment should be individualized, as there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

Dr. Cordoro disclosed that she is a member of the Celgene Corporation Scientific Steering Committee.

AUSTIN, TEX. – The way Kelly M. Cordoro sees it, the most for which patient.

“You can look up the dosing and frequency of these drugs; all of that’s available,” she said at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “But how do we think about which drug for which patient? What are the considerations?”

Dr. Cordoro, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, described psoriasis as an autoamplifying inflammatory cascade involving innate and adaptive immunity and noted that various components of that cascade represent treatment targets. “We don’t have a true comprehension of the pathophysiology of psoriasis, but as we learn the pathways, we’re targeting them,” she said. “You can target keratinocyte proliferation with drugs like retinoids and phototherapy. You can broadly target T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells with methotrexate, cyclosporine, and phototherapy. The newer drugs target the cytokine milieu, including TNF [tumor necrosis factor]–alpha, IL [interleukin]–17A, IL-12, and IL-23.”

There is no one right answer for which drug to prescribe, she continued, except in the cases of certain comorbidities, contraindications, and genetic variants. “For example, if a patient has psoriatic arthritis, then you have methotrexate and all of the biologics that might be disease modifying,” she said. “If a patient has inflammatory bowel disease, it’s critical to know that IL-17 inhibitors will flare that disease, but anti-TNF and IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitors are okay. If a patient has liver and kidney disease, you want to avoid methotrexate and cyclosporine. If there’s a female of childbearing potential you want to be very cautious with using retinoids. I think the harder question for us is, How about the rest of the patients?”

In addition to a drug’s mechanism of action, patient- and family-related factors play a role in deciding which agent to use. For example, does the patient prefer an oral or an injectable agent? Is the patient able to travel to a phototherapy center? Is it feasible for the family to manage visits for lab work and direct clinical monitoring? Does the family have a high level of health literacy and are you communicating with them in ways that facilitate shared decision making?

“The best way to choose a systemic therapy is to develop an individualized assessment of overall disease burden,” said Dr. Cordoro, who is also division chief of pediatric dermatology at UCSF. “Include psychological burden and subjective data in addition to objective measures like body surface area. Look for triggers. Infants are more commonly affected by viral infections and, in a subset, monogenic forms of psoriasis such as deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist [DIRA]. In general, we try to take a conservative approach in the developing child. As children hit early adolescence and become post pubertal, you have to start thinking about the psychosocial impact [of psoriasis], and we have to start treating patients with the consideration that chronic uncontrolled inflammation can potentially lead to comorbidities down the road. We see this in adults with severe psoriasis and early onset cardiovascular disease, the so-called psoriatic march from chronic inflammation to cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Cordoro advises clinicians to rethink the conventional “therapeutic ladder” concept and embrace the idea of “finding the right tool for the job right now.” If a patient presents with a flare from a known trigger such as a strep infection, “maybe you want to treat with something more conservative,” she said. “Once you treat, and if the trigger has been managed, they might be better. But some patients will need the most aggressive treatment right out of the gate.”

Tried and true systemic therapies for psoriasis include methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, and phototherapy, but none is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children. “These drugs have decades of experience behind them,” Dr. Cordoro said. “Methotrexate is slow to start but has a sustained profile, so if you can get the patient to respond, that response tends to persist. Methotrexate also prevents the formation of antidrug antibodies, which is important if you are considering use of a biologic agent later on.”

Cyclosporine is best if you need a rapid rescue drug to get the disease under control before moving on to other options. “One in four patients relapse once cyclosporine is discontinued, so the benefit may not be as sustained as with methotrexate,” she said. “Acitretin is a really nice choice when you can’t or don’t want to immunosuppress the patient, and phototherapy is good if you can get it. The advantages of systemic therapies are that they’re easy on, easy off, and you can combine medications in severe situations. Almost all of these drugs can be combined with another, with few exceptions. I would caution that over immunosuppression is the biggest risk ... so this must be done carefully and only when necessary.”

Biologic agents such as TNF inhibitors and IL-12/23 inhibitors are playing an increasing role in pediatric psoriasis. They can be expensive and difficult for some insurance plans to cover, but offer the convenience of better efficacy and less frequent lab monitoring than conventional systemics. In the United States, etanercept and ustekinumab are approved for moderate to severe pediatric plaque psoriasis in patients as young as age 4 and 12 years, respectively. TNF inhibitors have accumulated the most data in children, while data are accumulating in trials of IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors, and PDE4 inhibitors.

“These drugs have reassuring safety profiles; low rates of infection and adverse reactions,” Dr. Cordoro said of biologic agents. “They’ve changed the landscape completely because now the expectation is complete or near-complete clearance. In contrast to the systemic agents, which may be started and stopped repeatedly, you need to think about continuous therapy, because these drugs are immunogenic,” she noted. “Whether antibodies against them become neutralizing or not is a different case. If a patient does have antibodies, it does not mean you have to stop the drug. Dose escalation can help. Increasing frequency of use of the drug can help, but patients will develop antibodies and it may result in loss of efficacy or reactions to the drug,” she added.

“When you’re thinking about using a biologic agent, think about patients who are chronic, moderate to severe, and who will need more long-term therapy. Most importantly, treatment should be individualized, as there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

Dr. Cordoro disclosed that she is a member of the Celgene Corporation Scientific Steering Committee.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SPD 2019

Vape lung disease cases exceed 400, 3 dead

Vitamin E acetate is one possible culprit in the mysterious vaping-associated lung disease that has killed three patients, sickened 450, and baffled clinicians and investigators all summer.

Another death may be linked to the disorder, officials said during a joint press briefing held by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. In all, 450 potential cases have been reported and e-cigarette use confirmed in 215. Cases have occurred in 33 states and one territory. A total of 84% of the patients reported having used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) products in e-cigarette devices.

A preliminary report on the situation by Jennifer Layden, MD, of the department of public health in Illinois and colleagues – including a preliminary case definition – was simultaneously released in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614).

No single device or substance was common to all the cases, leading officials to issue a blanket warning against e-cigarettes, especially those containing THC.

“We believe a chemical exposure is likely related, but more information is needed to determine what substances. Some labs have identified vitamin E acetate in some samples,” said Dana Meaney-Delman, MD, MPH, incident manager, CDC 2019 Lung Injury Response. “Continued investigation is needed to identify the risk associated with a specific product or substance.”

Besides vitamin E acetate, federal labs are looking at other cannabinoids, cutting agents, diluting agents, pesticides, opioids, and toxins.

Officials also issued a general warning about the products. Youths, young people, and pregnant women should never use e-cigarettes, they cautioned, and no one should buy them from a noncertified source, a street vendor, or a social contact. Even cartridges originally obtained from a certified source should never have been altered in any way.

Dr. Layden and colleagues reported that bilateral lung infiltrates was characterized in 98% of the 53 patients hospitalized with the recently reported e-cigarette–induced lung injury. Nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, weight loss, and fatigue, were present in all of the patients.

Patients may show some symptoms days or even weeks before acute respiratory failure develops, and many had sought medical help before that. All presented with bilateral lung infiltrates, part of an evolving case definition. Many complained of nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, gastrointestinal symptoms, and weight loss. Of the patients who underwent bronchoscopy, many were diagnosed as having lipoid pneumonia, a rare condition characterized by lipid-laden macrophages.

“We don’t know the significance of the lipid-containing macrophages, and we don’t know if the lipids are endogenous or exogenous,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

The incidence of such cases appears to be rising rapidly, Dr. Layden noted. An epidemiologic review of cases in Illinois found that the mean monthly rate of visits related to severe respiratory illness in June-August was twice that observed during the same months last year.

SOURCE: Layden JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 1 0.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

Vitamin E acetate is one possible culprit in the mysterious vaping-associated lung disease that has killed three patients, sickened 450, and baffled clinicians and investigators all summer.

Another death may be linked to the disorder, officials said during a joint press briefing held by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. In all, 450 potential cases have been reported and e-cigarette use confirmed in 215. Cases have occurred in 33 states and one territory. A total of 84% of the patients reported having used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) products in e-cigarette devices.

A preliminary report on the situation by Jennifer Layden, MD, of the department of public health in Illinois and colleagues – including a preliminary case definition – was simultaneously released in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614).

No single device or substance was common to all the cases, leading officials to issue a blanket warning against e-cigarettes, especially those containing THC.

“We believe a chemical exposure is likely related, but more information is needed to determine what substances. Some labs have identified vitamin E acetate in some samples,” said Dana Meaney-Delman, MD, MPH, incident manager, CDC 2019 Lung Injury Response. “Continued investigation is needed to identify the risk associated with a specific product or substance.”

Besides vitamin E acetate, federal labs are looking at other cannabinoids, cutting agents, diluting agents, pesticides, opioids, and toxins.

Officials also issued a general warning about the products. Youths, young people, and pregnant women should never use e-cigarettes, they cautioned, and no one should buy them from a noncertified source, a street vendor, or a social contact. Even cartridges originally obtained from a certified source should never have been altered in any way.

Dr. Layden and colleagues reported that bilateral lung infiltrates was characterized in 98% of the 53 patients hospitalized with the recently reported e-cigarette–induced lung injury. Nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, weight loss, and fatigue, were present in all of the patients.

Patients may show some symptoms days or even weeks before acute respiratory failure develops, and many had sought medical help before that. All presented with bilateral lung infiltrates, part of an evolving case definition. Many complained of nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, gastrointestinal symptoms, and weight loss. Of the patients who underwent bronchoscopy, many were diagnosed as having lipoid pneumonia, a rare condition characterized by lipid-laden macrophages.

“We don’t know the significance of the lipid-containing macrophages, and we don’t know if the lipids are endogenous or exogenous,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

The incidence of such cases appears to be rising rapidly, Dr. Layden noted. An epidemiologic review of cases in Illinois found that the mean monthly rate of visits related to severe respiratory illness in June-August was twice that observed during the same months last year.

SOURCE: Layden JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 1 0.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

Vitamin E acetate is one possible culprit in the mysterious vaping-associated lung disease that has killed three patients, sickened 450, and baffled clinicians and investigators all summer.

Another death may be linked to the disorder, officials said during a joint press briefing held by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. In all, 450 potential cases have been reported and e-cigarette use confirmed in 215. Cases have occurred in 33 states and one territory. A total of 84% of the patients reported having used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) products in e-cigarette devices.

A preliminary report on the situation by Jennifer Layden, MD, of the department of public health in Illinois and colleagues – including a preliminary case definition – was simultaneously released in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Sep 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911614).

No single device or substance was common to all the cases, leading officials to issue a blanket warning against e-cigarettes, especially those containing THC.

“We believe a chemical exposure is likely related, but more information is needed to determine what substances. Some labs have identified vitamin E acetate in some samples,” said Dana Meaney-Delman, MD, MPH, incident manager, CDC 2019 Lung Injury Response. “Continued investigation is needed to identify the risk associated with a specific product or substance.”

Besides vitamin E acetate, federal labs are looking at other cannabinoids, cutting agents, diluting agents, pesticides, opioids, and toxins.

Officials also issued a general warning about the products. Youths, young people, and pregnant women should never use e-cigarettes, they cautioned, and no one should buy them from a noncertified source, a street vendor, or a social contact. Even cartridges originally obtained from a certified source should never have been altered in any way.

Dr. Layden and colleagues reported that bilateral lung infiltrates was characterized in 98% of the 53 patients hospitalized with the recently reported e-cigarette–induced lung injury. Nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, weight loss, and fatigue, were present in all of the patients.

Patients may show some symptoms days or even weeks before acute respiratory failure develops, and many had sought medical help before that. All presented with bilateral lung infiltrates, part of an evolving case definition. Many complained of nonspecific constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, gastrointestinal symptoms, and weight loss. Of the patients who underwent bronchoscopy, many were diagnosed as having lipoid pneumonia, a rare condition characterized by lipid-laden macrophages.

“We don’t know the significance of the lipid-containing macrophages, and we don’t know if the lipids are endogenous or exogenous,” Dr. Meaney-Delman said.

The incidence of such cases appears to be rising rapidly, Dr. Layden noted. An epidemiologic review of cases in Illinois found that the mean monthly rate of visits related to severe respiratory illness in June-August was twice that observed during the same months last year.

SOURCE: Layden JE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 6. doi: 1 0.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

FROM A CDC TELECONFERENCE AND NEJM

8-year-old boy • palpable purpura on the legs with arthralgia • absence of coagulopathy • upper respiratory infection • Dx?

THE CASE

An 8-year-old boy presented to his family physician (FP) with pharyngitis, nasal drainage, and a dry cough of 3 days’ duration. He denied any fever, chills, vomiting, or diarrhea. He had no sick contacts or prior history of streptococcal pharyngitis, but a rapid strep test was positive. No throat culture was performed at this time. The patient was started on amoxicillin 250 mg 3 times daily for 10 days.

On Day 7 of symptoms, the patient presented to the emergency department with elbow and knee pain, as well as mild swelling and purpura of his legs of 3 days’ duration. He was normotensive and reported no abdominal pain. A laboratory workup, including a complete blood cell count and differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, comprehensive metabolic panel, creatinine kinase test, urinalysis, and chest radiograph, was normal, but his erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was mildly elevated at 22 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). The patient was discharged on acetaminophen 15 mg/kg every 4 hours as needed for pain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

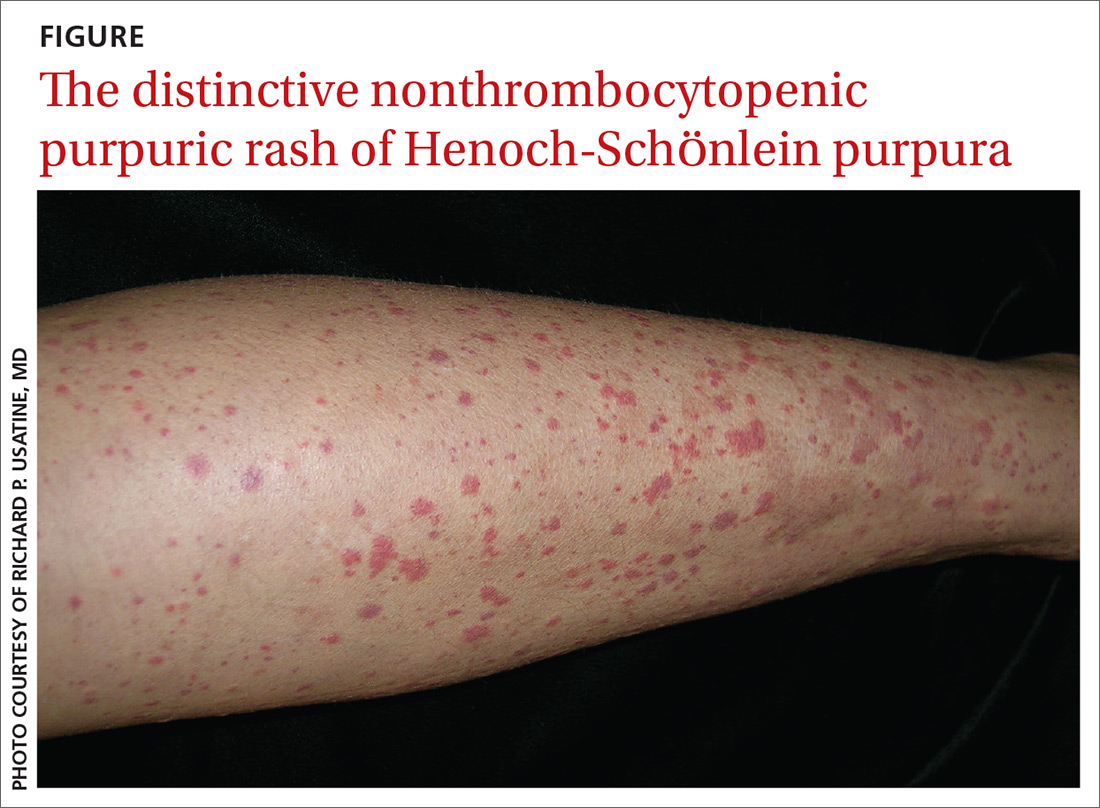

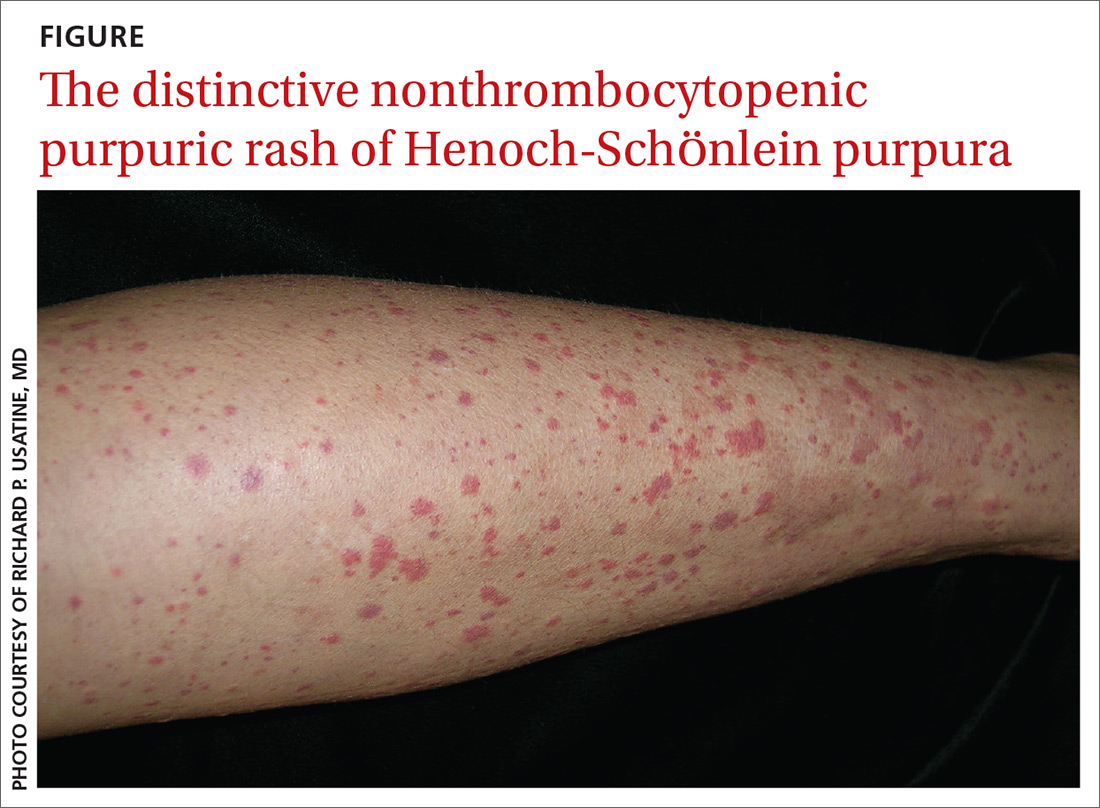

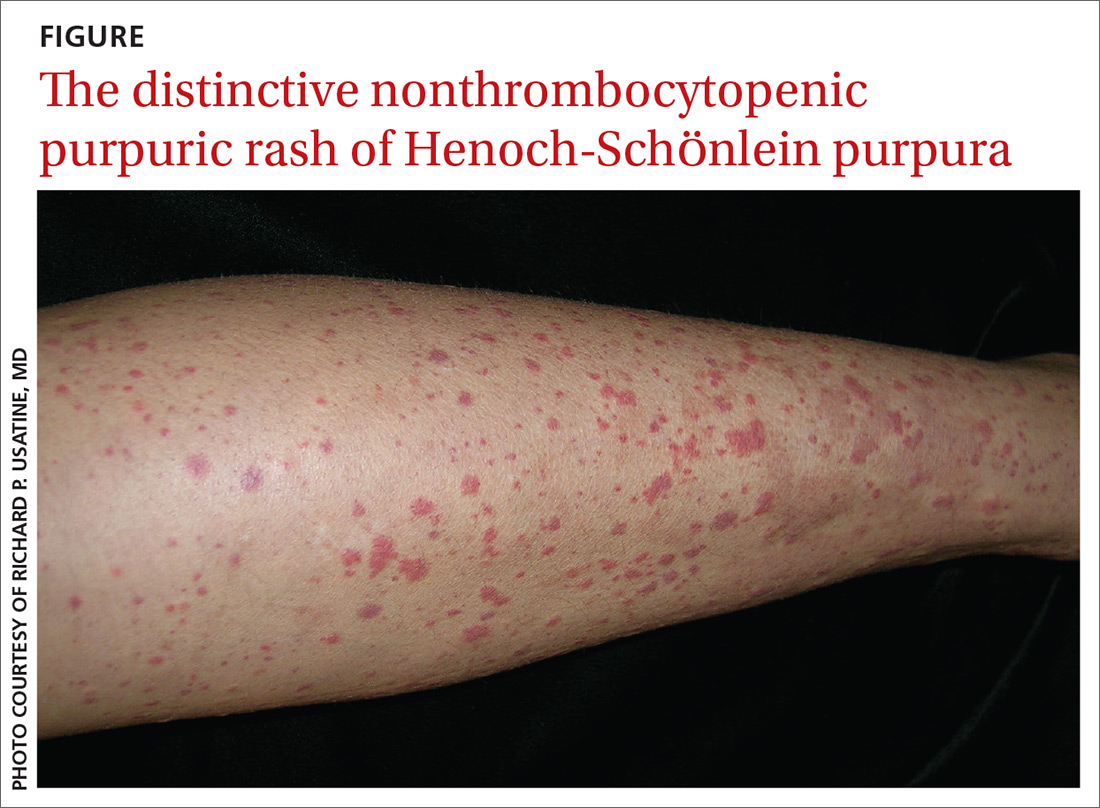

Based on the distinctive palpable purpura on the legs, arthralgia, upper respiratory infection, and lack of thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, a presumptive diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) was made.

On Day 9 of symptoms, the patient returned to his FP’s office because the arthralgia persisted in his ankles, knees, and hips. He had developed lower back pain, but the pharyngitis and upper respiratory symptoms had resolved. On physical examination, he was normotensive with a normal abdominal exam. The patient reported that it hurt to move his wrists, hands, elbows, shoulders, knees, and ankles. He also had mild swelling in his left wrist, hand, and ankle. The paraspinal muscles in the lower thoracic and lumbar back were mildly tender to palpation. A complete metabolic panel and urinalysis were normal. Dermatologic examination revealed discrete purpuric lesions ranging from 1 to 8 mm in diameter on the child’s shins, thighs, and buttocks. Urinalysis, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine kinase were normal. His ESR remained mildly elevated at 24 mm/h. Since there was no evidence of glomerulonephritis, ibuprofen 10 mg/kg every 8 hours as needed was added for pain management.

The child was brought back to his FP on Day 18 for a scheduled follow-up visit. The parents reported that his arthralgia was improved during the day, but by the evening, his knees and ankles hurt so much that they had to carry him to the bathroom. On physical examination, he still had palpable purpura of the legs. There was no swelling, but his joints were still tender to palpation. His parents were reminded to give him ibuprofen after school to control evening pain. Over the next 2 weeks, the patient showed gradual improvement, and by Day 33 the rash and all of the associated symptoms had resolved.

DISCUSSION

Clinical presentation. HSP is an IgA immune complex vasculitis in which abnormal glycosylation of IgA creates large immune complexes that are deposited in the walls of the skin capillaries and arterioles. The primary clinical finding in HSP is a distinctive nonthrombocytopenic purpuric rash that is not associated with coagulopathy and is characterized by reddish purple macules that progress to palpable purpura with petechiae (

A preceding upper respiratory infection has been found in 37% of patients,1 and in patients with renal complications, 20% to 50% have been found to have a group A Streptococcus infection.2 Other associations include food allergies, cold exposure, insect bites, and drug allergies.

Continue to: HSP vasculitis causes...

HSP vasculitis causes abdominal pain in 50% to 75% of patients due to proximal small-bowel submucosal hemorrhage and bowel wall edema.3 In children with HSP, 20% to 55% have been shown to develop renal disease,4 which can range in severity from microscopic hematuria to nephrotic syndrome.3 To ensure prompt treatment of renal manifestations, renal function should be monitored regularly via blood pressure and urinalysis during the course of HSP and after resolution. Renal disease associated with HSP can be acute or chronic.

This case was different because our patient did not exhibit all elements of the classic tetrad of HSP, which includes the characteristic rash, abdominal pain, renal involvement, and arthralgia.

Incidence. HSP is more common in children than adults, with average annual incidence rates of 20/100,000 and 70/100,000 in children in the United States and Asia, respectively.5 While 90% of HSP cases occur in children < 10 years, the peak incidence is at 6 years of age.6 Complications from HSP are more common in adults than in children.7 Caucasian and Asian populations have a 3- to 4-times higher prevalence of HSP than black populations. The male-to-female ratio is 2 to 1.6

The diagnosis of HSP is usually made clinically, based on the distinctive rash, which typically is symmetrical, involving the buttocks, lower legs, elbows, and/or knees. HSP also can be confirmed via skin biopsy and/or direct immunofluorescence, which can identify the presence of IgA in the vessel walls.

The presence of 3 or more of the following criteria also suggests HSP: palpable purpura, bowel angina, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, hematuria, ≤ 20 years of age at onset, and no medications prior to presentation of symptoms (87% of cases correctly classified). Fewer than 3 of these factors favor hypersensitivity vasculitis (74% of cases correctly classified).8

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for HSP includes polyarteritis nodosa, a vasculitis with a different characteristic rash; acute abdomen, distinguished by the absence of purpura or arthralgia; meningococcemia, in which fever and meningeal signs may occur; hypersensitivity vasculitis, which arises due to prior exposure to medications or food allergens; and thrombocytopenic purpura, which is characterized by low platelet count.9

Treatment focuses on pain management

In the absence of renal disease, HSP commonly is treated with naproxen for pain management (dosage for children < 2 years of age: 5-7 mg/kg orally every 8-12 hours; dosage for children ≥ 2 years of age, adolescents, and adults: 10-20 mg/kg/d divided into 2 doses; maximum adolescent and adult dose is 1500 mg/d for 3 days followed by a maximum of 1000 mg/d thereafter).

For patients of all ages with severe pain and those with GI effects limiting oral intake of medication, use oral prednisone (1-2 mg/kg/d [maximum dose, 60-80 mg/d]) or intravenous methylprednisolone (0.8-1.6 mg/kg/d [maximum dose, 64 mg/d). Glucocorticoids may then be tapered slowly over 4 to 8 weeks to avoid rebound since they help with inflammation but do not shorten the course of disease. Steroids can ease GI and joint symptoms in HSP but will not improve the rash.

THE TAKEAWAY

The classic tetrad of HSP includes the characteristic rash, abdominal pain, renal involvement, and arthralgia. Diagnosis usually is made clinically, but skin biopsy and direct immunofluorescence can confirm small vessel vasculitis with IgA deposits. More severe manifestations of HSP such as renal disease, hemorrhage, severe anemia, signs of intestinal obstruction, or peritonitis require rapid subspecialty referral.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rachel Bramson, MD, Department of Primary Care, Baylor Scott and White Health, University Clinic, 1700 University Drive, College Station, TX 77840; [email protected]

1. Rigante D, Castellazzi L, Bosco A, et al. Is there a crossroad between infections, genetics, and Henoch-Schönlein purpura? Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12:1016-1021.

2. LaConti JJ, Donet JA, Cho-Vega JH, et al. Henoch-Schönlein Purpura with adalimumab therapy for ulcerative colitis: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 27, 2016]. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2016;2016:2812980.

3. Trnka P. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:995-1003.

4. Audemard-Verger A, Pillebout E, Guillevin L, et al. IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Shönlein purpura) in adults: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:579-585.

5. Chen J, Mao J. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis in children: incidence, pathogenesis and management. World J Pediatr. 2015;11:29-34.

6. Michel B, Hunder G, Bloch D, et al. Hypersensitivity vasculitis and Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a comparison between the 2 disorders. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:721-728.

7. Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704.

8. Yang YH, Yu HH, Chiang BL. The diagnosis and classification of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: an updated review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:355-358.

9. Floege J, Feehally J. Treatment of IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schönlein nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:320-327.

THE CASE

An 8-year-old boy presented to his family physician (FP) with pharyngitis, nasal drainage, and a dry cough of 3 days’ duration. He denied any fever, chills, vomiting, or diarrhea. He had no sick contacts or prior history of streptococcal pharyngitis, but a rapid strep test was positive. No throat culture was performed at this time. The patient was started on amoxicillin 250 mg 3 times daily for 10 days.

On Day 7 of symptoms, the patient presented to the emergency department with elbow and knee pain, as well as mild swelling and purpura of his legs of 3 days’ duration. He was normotensive and reported no abdominal pain. A laboratory workup, including a complete blood cell count and differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, comprehensive metabolic panel, creatinine kinase test, urinalysis, and chest radiograph, was normal, but his erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was mildly elevated at 22 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). The patient was discharged on acetaminophen 15 mg/kg every 4 hours as needed for pain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the distinctive palpable purpura on the legs, arthralgia, upper respiratory infection, and lack of thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, a presumptive diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) was made.

On Day 9 of symptoms, the patient returned to his FP’s office because the arthralgia persisted in his ankles, knees, and hips. He had developed lower back pain, but the pharyngitis and upper respiratory symptoms had resolved. On physical examination, he was normotensive with a normal abdominal exam. The patient reported that it hurt to move his wrists, hands, elbows, shoulders, knees, and ankles. He also had mild swelling in his left wrist, hand, and ankle. The paraspinal muscles in the lower thoracic and lumbar back were mildly tender to palpation. A complete metabolic panel and urinalysis were normal. Dermatologic examination revealed discrete purpuric lesions ranging from 1 to 8 mm in diameter on the child’s shins, thighs, and buttocks. Urinalysis, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine kinase were normal. His ESR remained mildly elevated at 24 mm/h. Since there was no evidence of glomerulonephritis, ibuprofen 10 mg/kg every 8 hours as needed was added for pain management.