User login

Is your office ready for a case of measles?

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

It’s a typically busy Friday and the doctor is running 20 minutes behind schedule. He enters the next exam room and the sight of the patient makes him forget the apology he had prepared.

The 10 month old looks miserable. Red eyes. Snot dripping from his nose. A red rash that extends from his face and involves most of the chest, arms, and upper thighs.

“When did this start?” he asks the mother as he searches for a surgical mask in the cabinet next to the exam table.

“Two days after we returned from our vacation in France,” the worried young woman replies. “Do you think it could be measles?”

Between Jan. 1 and Aug. 8, 2019, 1,182 cases of measles had been confirmed in the United States. That’s more than three times the number of cases reported in all of 2018, and the highest number of cases reported in a single year in more than a quarter century. While 75% of the cases this year have been linked to outbreaks in New York, individuals from 30 states have been affected.

Given the widespread nature of the outbreak, With measles in particular, time is limited to deliver effective postexposure prophylaxis and prevent the spread of measles in the community, making it difficult to develop a plan on the fly.

Schedule strategically. You don’t want a patient with measles hanging out in your waiting room. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, measures to prevent the transmission of contagious infectious agents in ambulatory facilities begin at the time the visit is scheduled. When there is measles transmission in the community, consider using a standardized script when scheduling patients that includes questions about fever, rash, other symptoms typical for measles, and possible exposures. Some offices will have procedures in place that can be adapted to care for patients with suspected measles. When a patient presents for suspected chicken pox, do you advise them to come at the end of the day to minimize exposures? Enter through a side door? Perform a car visit?

Triage promptly. Mask patients with fever and rash, move to a private room, and close the door.

Once measles is suspected, only health care personnel who are immune to measles should enter the exam room. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, presumptive evidence of measles immunity in health care providers is written documentation of vaccination with two doses of live measles or MMR vaccine administered at least 28 days apart, laboratory evidence of immunity (that is, positive measles IgG), laboratory confirmation of disease, or birth before 1957.

Even though health care providers born before 1957 are presumed to have had the disease at some point and have traditionally been considered immune, the CDC suggests that health care facilities consider giving these individuals two doses of MMR vaccine unless they have prior laboratory confirmation of disease immunity. Do you know who in your office is immune or would you need to scramble if you had an exposure?

When measles is suspected, health care personnel should wear an N-95 if they have been fit tested and the appropriate mask is available. Practically, most ambulatory offices do not stock N-95 masks and the next best choice is a regular surgical mask.

Order the recommended tests to confirm the diagnosis, but do not wait for the results to confirm the diagnosis. The CDC recommends testing serum for IgM antibodies and sending a throat or nasopharyngeal swab to look for the virus by polymerase chain reaction testing. Measles virus also is shed in the urine so collecting a urine specimen for testing may increase the chances of finding the virus. Depending on where you practice, the tests may take 3 days or more to result. Contact your local health department as soon as you consider a measles diagnosis.

Discharge patients home or transferred to a higher level of care if this is necessary as quickly as possible. Fortunately, most patients with measles do not require hospitalization. Do not send patients to the hospital simply for the purpose of laboratory testing if this can be accomplished quickly in your office or for evaluation by other providers. This just creates the potential for more exposures. If a patient does require higher-level care, provider-to-provider communication about the suspected diagnosis and the need for airborne isolation should take place.

Keep the door closed. Once a patient with suspected measles is discharged from a regular exam room, the door should remain closed, and it should not be used for at least 1 hour. Remember that infectious virus can remain in the air for 1-2 hours after a patient leaves an area. The same is true for the waiting room.

Develop the exposure list. In general, patients and family members who were in the waiting room at the same time as the index patient and up to 1-2 hours after the index patient left are considered exposed. Measles is highly contagious and 9 out of 10 susceptible people who are exposed will develop disease. How many infants aged less than 1 year might be in your waiting room at any given time? How many immunocompromised patients or family members? Public health authorities can help determine who needs prophylaxis.

Don’t get anxious and start testing everyone for measles, especially patients who lack typical signs and symptoms or exposures. Ordering a test in a patient who has a low likelihood of measles is more likely to result in a false-positive test than a true-positive test. False-positive measles IgM tests can be seen with some viral infections, including parvovirus and Epstein-Barr. Some rheumatologic disorders also can contribute to false-positive tests.

Review your office procedure for vaccine counseling. The 10 month old with measles in the opening vignette should have been given an MMR vaccine before travel. The vaccine is recommended for infants aged 6-11 months who are traveling outside the United States, but it doesn’t count toward the vaccine series. Reimmunize young travelers at 12-15 months and again at 4-6 years. The CDC has developed a toolkit that contains resources for taking to parents about vaccines. It is available at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/toolkit/healthcare-providers.html.

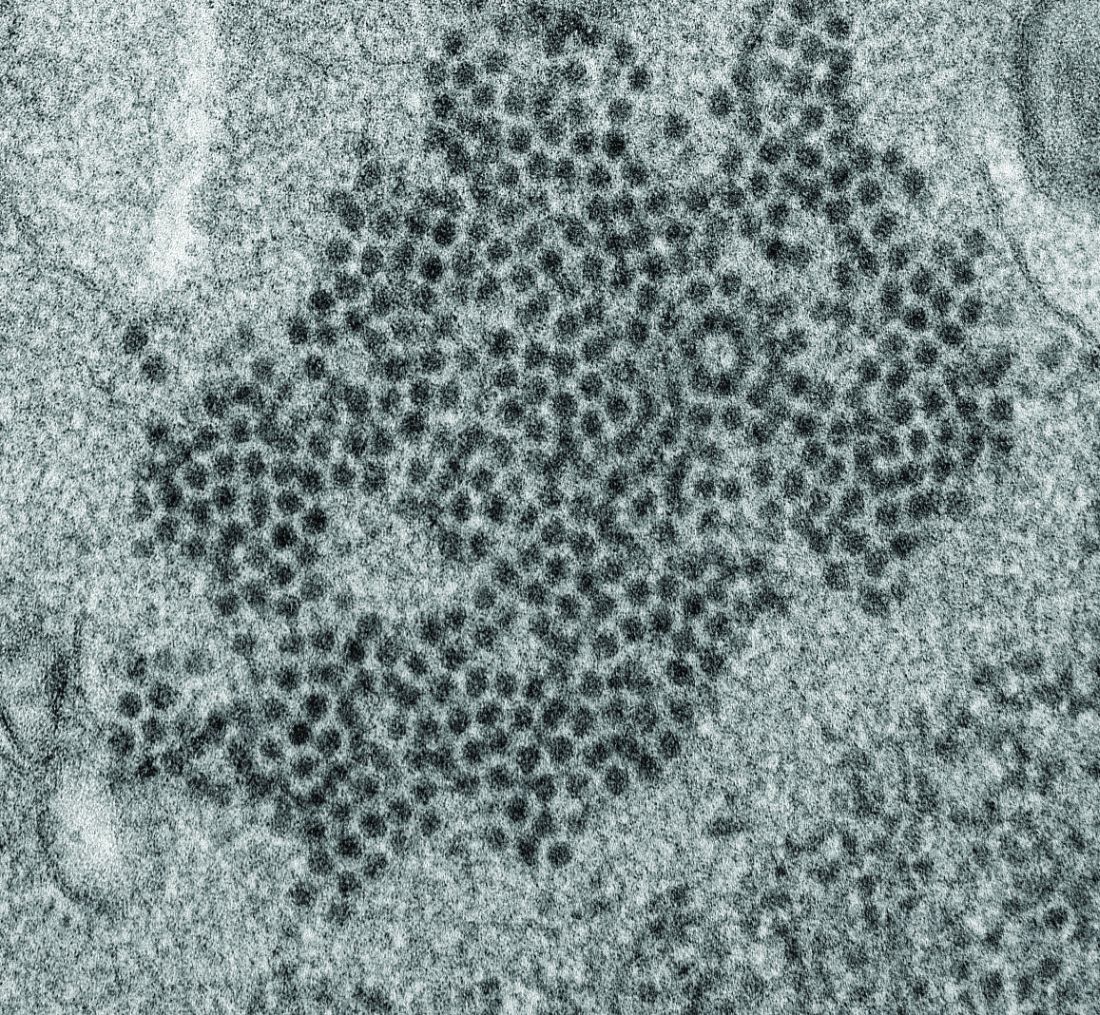

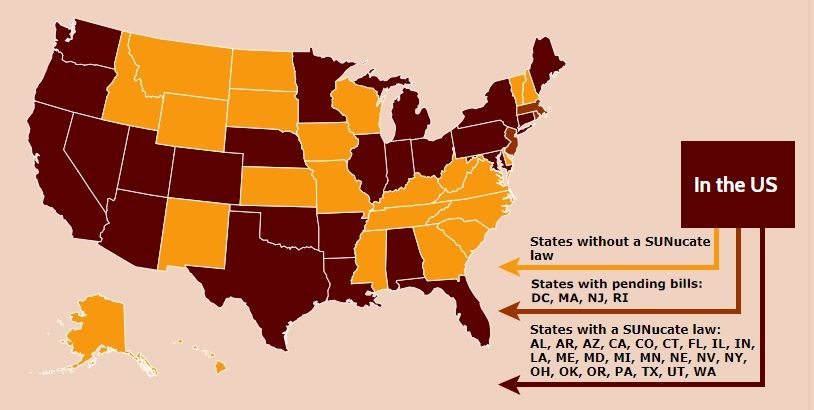

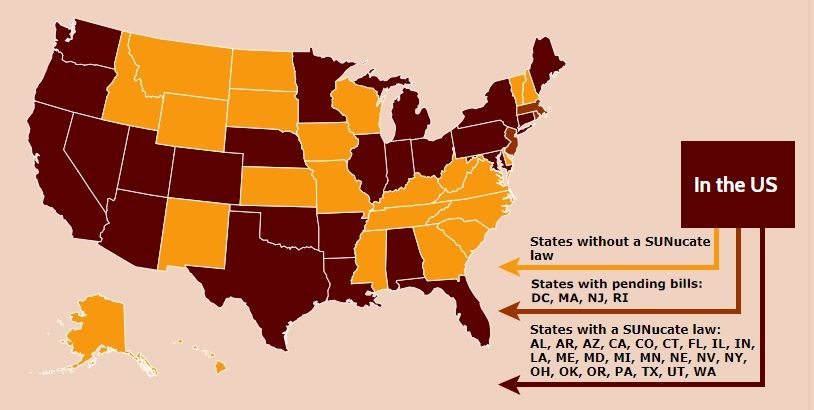

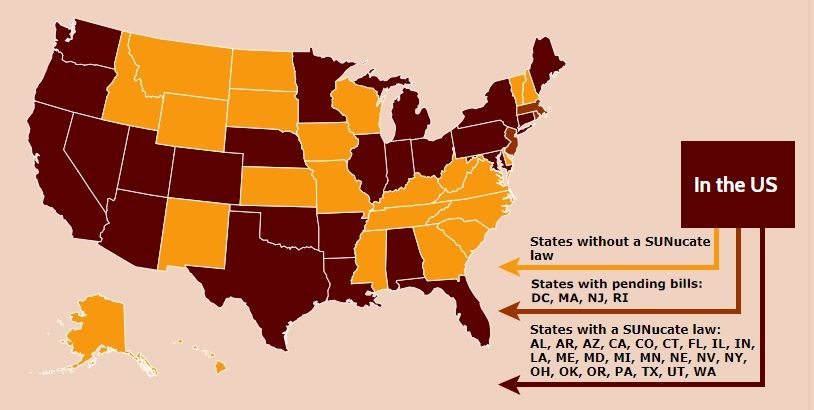

Nebraska issues SUNucate-based guidance for schools

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.

Nebraska’s Department of Education recommended in a guidance that children be allowed to possess and use sunscreen products in school and at school-sponsored events, according to an Aug. 2 release from the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The department’s guidance is based on model legislation developed by the SUNucate Coalition, which was created by the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association and “works to address barriers to sunscreen use in school and camps and promote sun-safe behavior.” The coalition was created in 2016 because of reports that some U.S. schools had banned sunscreen products as part of broader medication bans because of these products’ classification as an over-the-counter medication.

Twenty-three other states have moved to lift such bans; these states were joined by Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, and now Nebraska in 2019 alone. The District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island are expected to follow suit.

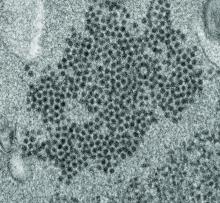

‘Substantial burden’ of enterovirus meningitis in young infants

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – A prospective international surveillance study has provided new insights into the surprisingly substantial clinical burden of viral meningitis caused by enteroviruses and human parechoviruses in young infants, Seilesh Kadambari, MBBS, PhD, said in his ESPID Young Investigator Award Lecture at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This comprehensive study captured all cases of laboratory-confirmed enterovirus (EV) and human parechovirus (HPeV) meningitis in infants less than 90 days old seen by pediatricians in the United Kingdom and Ireland during a 13-month period starting in July 2014, a time free of outbreaks. Dr. Kadambari, a pediatrician at the University of Oxford (England), was first author of the study. It was for this project, as well as his earlier studies shedding light on congenital viral infections, that he received the Young Investigator honor.

Among the key findings of the U.K./Ireland surveillance study: The incidence of EV/HPeV meningitis was more than twice that of bacterial meningitis in the same age group and more than fivefold higher than that of group B streptococcal meningitis, the No. 1 cause of bacterial meningitis in early infancy. Moreover, more than one-half of infants with EV/HPeV meningitis had low levels of inflammatory markers and no cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, which underscores the importance of routinely testing the cerebrospinal fluid for viral causes of meningitis in such patients using modern molecular tools such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction, according to Dr. Kadambari.

“Also, not a single one of the patients with EV/HPeV meningitis had a secondary bacterial infection – and that has important implications for management of our antibiotic stewardship programs,” he observed.

The study (Arch Dis Child. 2019 Jun;104(6):552-7) identified 668 cases of EV meningitis and 35 of HPeV meningitis, for an incidence of 0.79 and 0.04 per 1,000 live births, respectively. The most common clinical presentations were those generally seen in meningitis: fever, irritability, and reduced feeding. Circulatory shock was present in 43% of the infants with HPeV and 27% of the infants with EV infections.

Of infants with EV meningitis, 11% required admission to an intensive care unit, as did 23% of those with HPeV meningitis. Two babies with EV meningitis died and four others had continued neurologic complications at 12 months of follow-up. In contrast, all infants with HPeV survived without long-term sequelae.

Reassuringly, none of the 189 infants who underwent formal hearing testing had sensorineural hearing loss.

The surveillance study data have played an influential role in evidence-based guidelines for EV diagnosis and characterization published by the European Society of Clinical Virology (J Clin Virol. 2018 Apr;101:11-7).

An earlier study led by Dr. Kadambari documented a hefty sevenfold increase in the rate of laboratory-confirmed viral meningo-encephalitis in England and Wales during 2004-2013 across all age groups (J Infect. 2014 Oct;69[4]:326-32).

He attributed this increase to improved diagnosis of viral forms of meningitis through greater use of polymerase chain reaction. The study, based upon National Health Service hospital records, showed that more than 90% of all cases of viral meningo-encephalitis in infants less than 90 days old were caused by EV, a finding that prompted the subsequent prospective U.K./Ireland surveillance study.

Dr. Kadambari closed by noting the past decade had seen a greatly improved ability to diagnose congenital viral infections, but those improvements are not good enough.

“In the decade ahead, we hope to improve the management of this poorly understood group of infections,” the pediatrician promised.

Planned efforts include a cost-effectiveness analysis of a cytomegalovirus vaccine, an ESPID-funded research project aimed at identifying which EV/HPeV strains are most responsible for outbreaks and isolated severe disease, and gaining insight into the host-immunity factors associated with a proclivity to develop EV/HPeV meningitis in early infancy.

Dr. Kadambari reported having no financial conflicts regarding his studies, which was funded largely by Public Health England and university grants.

SOURCE: Kadambari S et al. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:552-7.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

A 2-month-old infant with a scalp rash that appeared after birth

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

With the perinatal history of prolonged labor and prolonged rupture of membranes, the diagnosis of halo scalp ring was made. This occurs secondary to prolonged pressure of the baby’s scalp with the mother’s pelvic bones, uterus, or cervical area, which causes decreased blood flow to the area, secondary ischemic damage, and in some cases scarring and hair loss.1

The degree of involvement is variable as some babies have mild alopecia and others have severe full-thickness necrosis and scarring. These lesions also can present with associated caput succedaneum and scalp molding, but these were not seen in our patient. Predisposing factors for halo scalp ring include caput succedaneum, prolonged or difficult labor, premature or prolonged rupture of membranes, vaginal delivery, vertex presentation, first delivery, as well as prematurity.2 On physical examination, a semicircular patch of alopecia with associated scarring, crusting, or erythema can be seen in some more severe cases.

The differential diagnosis includes aplasia cutis. In aplasia cutis, there is congenital loss of skin on the affected areas. The scalp usually is affected, but these lesions can occur in any other part of the body. Most patients with aplasia cutis have no other findings, but there are cases that can be associated with other cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or central nervous system abnormalities. Neonatal lupus also can present with scarring lesions on the scalp, but they usually present a little after birth, mainly affecting the face. The mothers of this children usually have a diagnosis of connective tissue disease and may have positive antibodies to Sjögren’s syndrome antibody A, Sjögren’s syndrome antibody B, or antiribonucleoprotein antibody. Seborrheic dermatitis does not cause scarring alopecia. The lesions present as waxy scaly plaques on the scalp, erythematous waxy plaques behind the ears, face, and folds. Some patients can have hair loss secondary to the inflammation, but the hair grows back once the inflammation is controlled. Dissecting cellulitis is a type of scarring alopecia seen in pubescent and adult individuals. No cases of neonatal dissecting cellulitis have been described.

Halo scalp ring is not associated with any other systemic symptoms or syndromes. Extensive imaging and systemic work-up are not required unless the baby presents with other neurologic symptoms. The areas can be treated with petrolatum and observation as most lesions resolve.

In cases of extensive areas of scarring alopecia, referral to a plastic surgeon can be made to consider tissue expanders or scar revision prior to the child starting school if the lesions are causing psychological stressors.

The true prevalence of this condition is unknown. We believe halo ring alopecia is sometimes not diagnosed, and as lesions tend to resolve, most cases go unreported.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):673.

2. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009 Nov-Dec;26(6):706-8.

3. Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15;22(11).pii:13030/qt7rt592tz.

A 2-month-old male is referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of persistent seborrheic dermatitis. The mother reports that he presented with a rash on his scalp a few days after birth. She has been treating the crusted areas with clotrimazole and hydrocortisone and has noted improvement on the crusting, but now is worried that there is some scarring. The affected areas are not bleeding or tender. There are no other rashes elsewhere in the body.

He was born at 36 weeks from a 35-year-old gravida 1 para 0 woman with adequate prenatal care. The mother was diagnosed with preeclampsia and was induced. She had a prolonged labor and had premature rupture of membranes. The baby was delivered via cesarean section because of failure to progress and fetal distress; forceps, vacuum, and a scalp probe were not used during delivery. He was admitted to the neonatal unit for 5 days for sepsis work-up and respiratory distress. No intubation was needed.

Besides the preeclampsia, the mother denied any other medical conditions and was not taking any medications. He has met all developmental milestones for his age. He has no history of seizures.

On physical exam, there are semicircular patches of alopecia on the scalp. Some areas have pink, rubbery plaques with loss of hair follicles. On the frontal scalp, there are waxy plaques.

There is a blanchable violaceous patch on the occiput and there are some erythematous papules on the cheeks.

How to nearly eliminate CLABSIs in children’s hospitals

SEATTLE – Levine Children’s Hospital, in Charlotte, N.C., dropped its central line–associated bloodstream infection rate from 1.13 per 1,000 line days to 0.67 in just a few months, with a mix of common sense steps and public accountability.

Levine Children’s was at about the 50th percentile for CLABSIs, compared with other children’s hospitals, but dropped to the 10th percentile after the changes. There were 21 CLABSIs in 2017, but only 12 in 2018. The hospital went 6 straight months without a CLABSI after the changes were made. The efforts saved about $300,000 and 63 patient days.

“We really had great success,” said Kayla S. Koch, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s, who presented the findings at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Hospital units had been working to reduce CLABSIs, but they were each doing their own thing. “Many of our units were already dabbling, so we just sort of brought them together. We standardized the process and got everyone on the same page,” said copresenter Ketan P. Nadkarni, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s.

It wasn’t hard to get buy-in. “I don’t think the units were aware that everyone was doing it differently,” and were on board once the problem was explained. Also, using the same approach throughout the hospital made it easier for nurses and physicians moving between units, he said.

Each morning, the nurse supervisor and patient nurse would partner up at the bedside to check that central venous lines were set up correctly. They examined the alcohol disinfectant caps to make sure they were clean; determined that children were getting chlorhexidine gluconate baths; checked the dressings for bleeding and soiling; noted in the electronic medical record why the patient had a central line; and discussed with hospitalists if it were still needed. Problems were addressed immediately.

These quality processes were all tracked on wall racks placed in plain sight on each unit, including the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Each central line patient had a card that listed what needed to be done, with a green stripe on one side and a red stripe on the other. If everything was done right, the green side faced out; if even one thing was done wrong, the red side was displayed, for all to see. It brought accountability to the process, the presenters said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The wall rack also had the central line audit schedule, plus diagrams that showed every failed item, the reason for it, and the unit’s compliance rate. Anyone walking by could see at a glance how the unit was doing that day and overall.

The number of dressing options was reduced from 10 to 2, a SorbaView SHIELD and a Tegaderm-like dressing, which made it easier to standardize the efforts. A protocol also was put in place to reinforce oozing dressings, instead of automatically changing them. “We were doing too many changes,” Dr. Koch said.

Compliance with the bundle was almost 90%. Staff “really got into it, and it was great to see,” she said.

The “initial success was almost unexpected, and so dramatic.” The goal now is to sustain the improvements, and roll them out to radiology and other places were central lines are placed, Dr. Nadkarni said.

There was no external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Levine Children’s Hospital, in Charlotte, N.C., dropped its central line–associated bloodstream infection rate from 1.13 per 1,000 line days to 0.67 in just a few months, with a mix of common sense steps and public accountability.

Levine Children’s was at about the 50th percentile for CLABSIs, compared with other children’s hospitals, but dropped to the 10th percentile after the changes. There were 21 CLABSIs in 2017, but only 12 in 2018. The hospital went 6 straight months without a CLABSI after the changes were made. The efforts saved about $300,000 and 63 patient days.

“We really had great success,” said Kayla S. Koch, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s, who presented the findings at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Hospital units had been working to reduce CLABSIs, but they were each doing their own thing. “Many of our units were already dabbling, so we just sort of brought them together. We standardized the process and got everyone on the same page,” said copresenter Ketan P. Nadkarni, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s.

It wasn’t hard to get buy-in. “I don’t think the units were aware that everyone was doing it differently,” and were on board once the problem was explained. Also, using the same approach throughout the hospital made it easier for nurses and physicians moving between units, he said.

Each morning, the nurse supervisor and patient nurse would partner up at the bedside to check that central venous lines were set up correctly. They examined the alcohol disinfectant caps to make sure they were clean; determined that children were getting chlorhexidine gluconate baths; checked the dressings for bleeding and soiling; noted in the electronic medical record why the patient had a central line; and discussed with hospitalists if it were still needed. Problems were addressed immediately.

These quality processes were all tracked on wall racks placed in plain sight on each unit, including the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Each central line patient had a card that listed what needed to be done, with a green stripe on one side and a red stripe on the other. If everything was done right, the green side faced out; if even one thing was done wrong, the red side was displayed, for all to see. It brought accountability to the process, the presenters said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The wall rack also had the central line audit schedule, plus diagrams that showed every failed item, the reason for it, and the unit’s compliance rate. Anyone walking by could see at a glance how the unit was doing that day and overall.

The number of dressing options was reduced from 10 to 2, a SorbaView SHIELD and a Tegaderm-like dressing, which made it easier to standardize the efforts. A protocol also was put in place to reinforce oozing dressings, instead of automatically changing them. “We were doing too many changes,” Dr. Koch said.

Compliance with the bundle was almost 90%. Staff “really got into it, and it was great to see,” she said.

The “initial success was almost unexpected, and so dramatic.” The goal now is to sustain the improvements, and roll them out to radiology and other places were central lines are placed, Dr. Nadkarni said.

There was no external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

SEATTLE – Levine Children’s Hospital, in Charlotte, N.C., dropped its central line–associated bloodstream infection rate from 1.13 per 1,000 line days to 0.67 in just a few months, with a mix of common sense steps and public accountability.

Levine Children’s was at about the 50th percentile for CLABSIs, compared with other children’s hospitals, but dropped to the 10th percentile after the changes. There were 21 CLABSIs in 2017, but only 12 in 2018. The hospital went 6 straight months without a CLABSI after the changes were made. The efforts saved about $300,000 and 63 patient days.

“We really had great success,” said Kayla S. Koch, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s, who presented the findings at Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Hospital units had been working to reduce CLABSIs, but they were each doing their own thing. “Many of our units were already dabbling, so we just sort of brought them together. We standardized the process and got everyone on the same page,” said copresenter Ketan P. Nadkarni, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at Levine Children’s.

It wasn’t hard to get buy-in. “I don’t think the units were aware that everyone was doing it differently,” and were on board once the problem was explained. Also, using the same approach throughout the hospital made it easier for nurses and physicians moving between units, he said.

Each morning, the nurse supervisor and patient nurse would partner up at the bedside to check that central venous lines were set up correctly. They examined the alcohol disinfectant caps to make sure they were clean; determined that children were getting chlorhexidine gluconate baths; checked the dressings for bleeding and soiling; noted in the electronic medical record why the patient had a central line; and discussed with hospitalists if it were still needed. Problems were addressed immediately.

These quality processes were all tracked on wall racks placed in plain sight on each unit, including the neonatal and pediatric ICUs. Each central line patient had a card that listed what needed to be done, with a green stripe on one side and a red stripe on the other. If everything was done right, the green side faced out; if even one thing was done wrong, the red side was displayed, for all to see. It brought accountability to the process, the presenters said at the meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The wall rack also had the central line audit schedule, plus diagrams that showed every failed item, the reason for it, and the unit’s compliance rate. Anyone walking by could see at a glance how the unit was doing that day and overall.

The number of dressing options was reduced from 10 to 2, a SorbaView SHIELD and a Tegaderm-like dressing, which made it easier to standardize the efforts. A protocol also was put in place to reinforce oozing dressings, instead of automatically changing them. “We were doing too many changes,” Dr. Koch said.

Compliance with the bundle was almost 90%. Staff “really got into it, and it was great to see,” she said.

The “initial success was almost unexpected, and so dramatic.” The goal now is to sustain the improvements, and roll them out to radiology and other places were central lines are placed, Dr. Nadkarni said.

There was no external funding, and the investigators had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2019

Maternal factors impact childhood skin microbiota

Bacteria on children’s skin was similar to their mothers’ and affected by factors that included method of delivery and breastfeeding in a study of 154 children aged 10 years and younger.

Understanding the wrote Ting Zhu of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, the researchers compared the skin microbiota of the 158 children aged 1-10 years and 50 mothers using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing after collecting study samples from three skin areas: face, calf, and ventral forearm. The samples were pooled into 36 groups based on age, gender, and skin site.

“We observed significant differences in alpha diversity and the most prevalent taxa and identified factors that contributed to variation at each site,” the authors reported.

Overall, the “alpha diversity” – a measure of microbial diversity used in microbiome studies – of the skin microbiome increased with age, with the highest alpha diversity seen in the 10-year-olds (n = 28), notably on the face, but differences in alpha diversity between skin sites were seen only in the 1-year-olds (n = 26). Overall, the most commonly identified bacterial phyla at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%). In the three sites, the genera with high relative abundance (over 3%) included Streptococcus (13%), Enhydrobacter (6%), and Propionibacterium (5%). Of these, Streptococcus and Granulicatella showed negative linear correlations with age.

The researchers found significant differences between the bacterial communities of 10-year-olds delivered by Cesarean section and those delivered vaginally, particularly in the facial samples; however the difference wasn’t observed among face samples taken from 1-year-olds, according to the authors. They found significant variation in bacteria in calf samples based on whether the children were fed breast milk, formula, or a combination.

When the researchers examined the correlations between mother/child pairs, they found that the relative abundance of most bacteria in the children were more similar to their mothers than to unrelated adults, and they found the strongest correlations for the genera Deinococcus, Microbacterium, Chryseobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enhydrobacter. The relationships between the bacterial communities of mothers and children may be influenced by the shared living environment, topical products, and daily diet, they noted.

The study findings were limited by not controlling for certain variables, including daily diet, choice of topical products, bathing habits, and daily variation in environmental factors, the researchers wrote. However, the results show “that the skin microbiome is strongly affected by the surrounding microenvironment and that the alpha diversity of the skin microbiome increases during childhood,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

Bacteria on children’s skin was similar to their mothers’ and affected by factors that included method of delivery and breastfeeding in a study of 154 children aged 10 years and younger.

Understanding the wrote Ting Zhu of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, the researchers compared the skin microbiota of the 158 children aged 1-10 years and 50 mothers using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing after collecting study samples from three skin areas: face, calf, and ventral forearm. The samples were pooled into 36 groups based on age, gender, and skin site.

“We observed significant differences in alpha diversity and the most prevalent taxa and identified factors that contributed to variation at each site,” the authors reported.

Overall, the “alpha diversity” – a measure of microbial diversity used in microbiome studies – of the skin microbiome increased with age, with the highest alpha diversity seen in the 10-year-olds (n = 28), notably on the face, but differences in alpha diversity between skin sites were seen only in the 1-year-olds (n = 26). Overall, the most commonly identified bacterial phyla at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%). In the three sites, the genera with high relative abundance (over 3%) included Streptococcus (13%), Enhydrobacter (6%), and Propionibacterium (5%). Of these, Streptococcus and Granulicatella showed negative linear correlations with age.

The researchers found significant differences between the bacterial communities of 10-year-olds delivered by Cesarean section and those delivered vaginally, particularly in the facial samples; however the difference wasn’t observed among face samples taken from 1-year-olds, according to the authors. They found significant variation in bacteria in calf samples based on whether the children were fed breast milk, formula, or a combination.

When the researchers examined the correlations between mother/child pairs, they found that the relative abundance of most bacteria in the children were more similar to their mothers than to unrelated adults, and they found the strongest correlations for the genera Deinococcus, Microbacterium, Chryseobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enhydrobacter. The relationships between the bacterial communities of mothers and children may be influenced by the shared living environment, topical products, and daily diet, they noted.

The study findings were limited by not controlling for certain variables, including daily diet, choice of topical products, bathing habits, and daily variation in environmental factors, the researchers wrote. However, the results show “that the skin microbiome is strongly affected by the surrounding microenvironment and that the alpha diversity of the skin microbiome increases during childhood,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

Bacteria on children’s skin was similar to their mothers’ and affected by factors that included method of delivery and breastfeeding in a study of 154 children aged 10 years and younger.

Understanding the wrote Ting Zhu of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, the researchers compared the skin microbiota of the 158 children aged 1-10 years and 50 mothers using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing after collecting study samples from three skin areas: face, calf, and ventral forearm. The samples were pooled into 36 groups based on age, gender, and skin site.

“We observed significant differences in alpha diversity and the most prevalent taxa and identified factors that contributed to variation at each site,” the authors reported.

Overall, the “alpha diversity” – a measure of microbial diversity used in microbiome studies – of the skin microbiome increased with age, with the highest alpha diversity seen in the 10-year-olds (n = 28), notably on the face, but differences in alpha diversity between skin sites were seen only in the 1-year-olds (n = 26). Overall, the most commonly identified bacterial phyla at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%). In the three sites, the genera with high relative abundance (over 3%) included Streptococcus (13%), Enhydrobacter (6%), and Propionibacterium (5%). Of these, Streptococcus and Granulicatella showed negative linear correlations with age.

The researchers found significant differences between the bacterial communities of 10-year-olds delivered by Cesarean section and those delivered vaginally, particularly in the facial samples; however the difference wasn’t observed among face samples taken from 1-year-olds, according to the authors. They found significant variation in bacteria in calf samples based on whether the children were fed breast milk, formula, or a combination.

When the researchers examined the correlations between mother/child pairs, they found that the relative abundance of most bacteria in the children were more similar to their mothers than to unrelated adults, and they found the strongest correlations for the genera Deinococcus, Microbacterium, Chryseobacterium, Klebsiella, and Enhydrobacter. The relationships between the bacterial communities of mothers and children may be influenced by the shared living environment, topical products, and daily diet, they noted.

The study findings were limited by not controlling for certain variables, including daily diet, choice of topical products, bathing habits, and daily variation in environmental factors, the researchers wrote. However, the results show “that the skin microbiome is strongly affected by the surrounding microenvironment and that the alpha diversity of the skin microbiome increases during childhood,” they concluded.

The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Age, skin site, and maternal factors including delivery method and breastfeeding impact the bacterial makeup of children’s skin.

Major finding: The most common bacteria at all skin sites in children were Proteobacteria (42%), Firmicutes (25%), Actinobacteria (13%), and Bacteroidetes (11%).

Study details: The data come from 158 children aged 10 years and younger and included 474 skin samples.

Disclosures: The study was fully funded by Johnson & Johnson International, and several coauthors are employees of that company. Lead author Ms. Zhu had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Zhu T et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 August 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.018.

Possible role of enterovirus infection in acute flaccid myelitis cases detected

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

FROM MBIO

Key clinical point:

Major finding: EV peptide antibodies were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), significantly higher than in controls.

Study details: A peptide microarray analysis was performed on CSF and sera from 14 AFM patients, as well as three control groups of 5 pediatric and adult patients with a non-AFM CNS diseases, 10 children with Kawasaki disease, and 10 adult patients with non-AFM CNS diseases.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

Bisphosphonates improve BMD in pediatric rheumatic disease

Prophylactic treatment with bisphosphonates could significantly improve bone mineral density (BMD) in children and adolescents receiving steroids for chronic rheumatic disease, a study has found.

A paper published in EClinicalMedicine reported the outcomes of a multicenter, double-dummy, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 217 patients who were receiving steroid therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis, or juvenile vasculitis. The patients were randomized to risedronate, alfacalcidol, or placebo, and all of the participants received 500 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D daily.

Lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD increased in all groups, but the greatest increase was seen in patients treated with risedronate.

After 1 year, lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD had increased in all groups, compared with baseline, but the greatest increase was seen in patients who had been treated with risedronate.

The lumbar spine areal BMD z score remained the same in the placebo group (−1.15 to −1.13), decreased from −0.96 to −1.00 in the alfacalcidol group, and increased from −0.99 to −0.75 in the risedronate group.

The change in z scores was significantly different between placebo and risedronate groups, and between risedronate and alfacalcidol groups, but not between placebo and alfacalcidol.

“The acquisition of adequate peak bone mass is not only important for the young person in reducing fracture risk but also has significant implications for the development of osteoporosis in later life, if peak bone mass is suboptimal,” wrote Madeleine Rooney, MBBCH, from the Queens University of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and associates.

There were no significant differences between the three groups in fracture rates. However, researchers were also able to compare Genant scores for vertebral fractures in 187 patients with pre- and posttreatment lateral spinal x-rays. That showed that the 54 patients in the placebo arm and 52 patients in the alfacalcidol arm had no change in their baseline Genant score of 0 (normal). However, although all 53 patients in the risedronate group had a Genant score of 0 at baseline, at 1-year follow-up, 2 patients had a Genant score of 1 (mild fracture), and 1 patient had a score of 3 (severe fracture).

In biochemical parameters, researchers saw a drop in parathyroid hormone in the placebo and alfacalcidol groups, but a rise in the risedronate group. However, the authors were not able to see any changes in bone markers that might have indicated which patients responded better to treatment.