User login

FUO, pneumonia often distinguishes influenza from RSV in hospitalized young children

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – as the cause of hospitalization in infants and young children, Cihan Papan, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

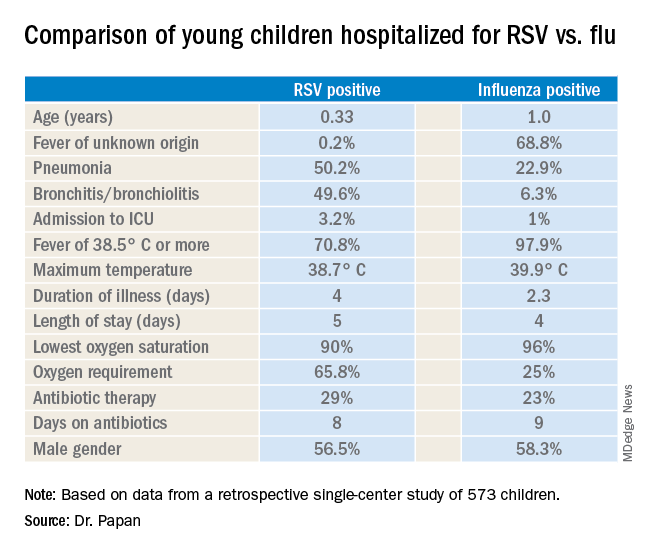

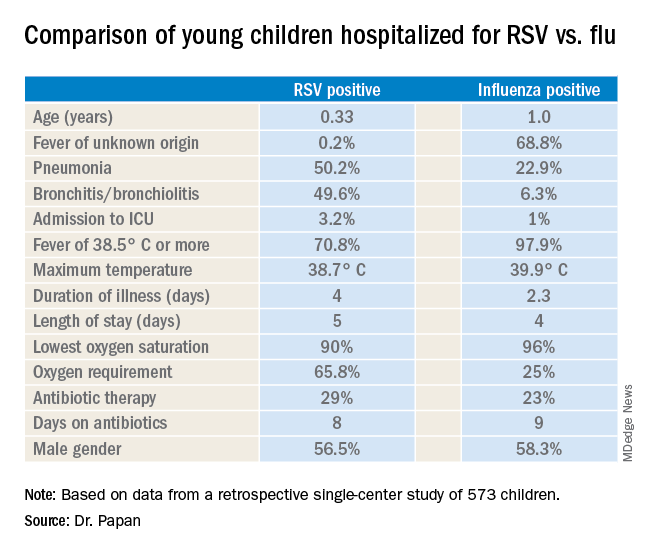

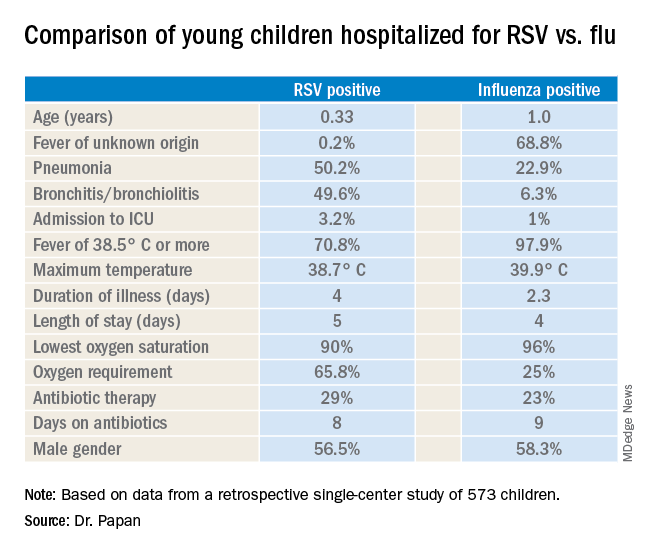

Dr. Papan, a pediatrician at University Children’s Hospital Mannheim (Germany) and Heidelberg (Germany) University, presented a retrospective single-center study of all 573 children aged under 2 years hospitalized over the course of several seasons for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or influenza as confirmed by rapid antigen testing. Even though these are two of the leading causes of hospitalization among young children, there is surprisingly sparse data comparing the two in terms of disease severity and hospital resource utilization, including antibiotic consumption. That information gap provided the basis for this study.

There were 476 children with confirmed RSV, 96 with influenza, and 1 RSV/influenza coinfection. Notably, even though the RSV group had lower temperatures and C-reactive protein levels, they were nevertheless more likely to be treated with antibiotics, by a margin of 29% to 23%.

“These findings open new possibilities for antimicrobial stewardship in these groups of virally infected children,” observed Dr. Papan.

Fever of unknown origin was present in 68.8% of the influenza-positive patients, compared with just 0.2% of the RSV-positive children. In contrast, 50.2% of the RSV group had pneumonia and 49.6% had bronchitis or bronchiolitis, versus just 22.9% and 6.3% of the influenza patients, respectively. A larger proportion of the young children with RSV infection presented in a severely ill–looking condition. Children with RSV infection also were significantly younger.

Dr. Papan reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – as the cause of hospitalization in infants and young children, Cihan Papan, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Papan, a pediatrician at University Children’s Hospital Mannheim (Germany) and Heidelberg (Germany) University, presented a retrospective single-center study of all 573 children aged under 2 years hospitalized over the course of several seasons for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or influenza as confirmed by rapid antigen testing. Even though these are two of the leading causes of hospitalization among young children, there is surprisingly sparse data comparing the two in terms of disease severity and hospital resource utilization, including antibiotic consumption. That information gap provided the basis for this study.

There were 476 children with confirmed RSV, 96 with influenza, and 1 RSV/influenza coinfection. Notably, even though the RSV group had lower temperatures and C-reactive protein levels, they were nevertheless more likely to be treated with antibiotics, by a margin of 29% to 23%.

“These findings open new possibilities for antimicrobial stewardship in these groups of virally infected children,” observed Dr. Papan.

Fever of unknown origin was present in 68.8% of the influenza-positive patients, compared with just 0.2% of the RSV-positive children. In contrast, 50.2% of the RSV group had pneumonia and 49.6% had bronchitis or bronchiolitis, versus just 22.9% and 6.3% of the influenza patients, respectively. A larger proportion of the young children with RSV infection presented in a severely ill–looking condition. Children with RSV infection also were significantly younger.

Dr. Papan reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – as the cause of hospitalization in infants and young children, Cihan Papan, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Papan, a pediatrician at University Children’s Hospital Mannheim (Germany) and Heidelberg (Germany) University, presented a retrospective single-center study of all 573 children aged under 2 years hospitalized over the course of several seasons for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or influenza as confirmed by rapid antigen testing. Even though these are two of the leading causes of hospitalization among young children, there is surprisingly sparse data comparing the two in terms of disease severity and hospital resource utilization, including antibiotic consumption. That information gap provided the basis for this study.

There were 476 children with confirmed RSV, 96 with influenza, and 1 RSV/influenza coinfection. Notably, even though the RSV group had lower temperatures and C-reactive protein levels, they were nevertheless more likely to be treated with antibiotics, by a margin of 29% to 23%.

“These findings open new possibilities for antimicrobial stewardship in these groups of virally infected children,” observed Dr. Papan.

Fever of unknown origin was present in 68.8% of the influenza-positive patients, compared with just 0.2% of the RSV-positive children. In contrast, 50.2% of the RSV group had pneumonia and 49.6% had bronchitis or bronchiolitis, versus just 22.9% and 6.3% of the influenza patients, respectively. A larger proportion of the young children with RSV infection presented in a severely ill–looking condition. Children with RSV infection also were significantly younger.

Dr. Papan reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Treating children with Kawasaki disease and coronary enlargement

IVIG plus steroids or infliximab, or IVIG alone?

Clinical question

Does use of corticosteroids or infliximab in addition to intravenous immunoglobulin improve cardiac outcomes in children with Kawasaki disease and enlarged coronary arteries?

Background

Kawasaki disease is a medium-vessel vasculitis primarily of young children. While the underlying cause remains unknown, treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) substantially lowers the risk of coronary artery aneurysms (CAA), the most serious sequelae of Kawasaki disease. Recent studies have suggested that – in cases of high-risk or treatment-resistant Kawasaki disease – using an immunomodulator, such as a corticosteroid or a TNF-alpha blocker, may improve outcomes, though these studies involved relatively small and homogeneous patient populations. It is unknown if these medications could prevent progression of CAA.

Study design

Retrospective multicenter study.

Setting

Two freestanding children’s hospitals and one mother-child hospital.

Synopsis

The study identified 121 children diagnosed with Kawasaki disease with CAA (z score 2.5-10) from 2008 through 2017 treated at the three study hospitals. Children with giant CAA at the time of diagnosis (z score greater than 10) or significant preexisting congenital heart disease were excluded.

All study hospitals had protocols for treatment of Kawasaki disease: Center 1 used IVIG and corticosteroids, Center 2 used IVIG and infliximab, and Center 3 used IVIG alone. Patients at all centers also received aspirin. Center 1 used methylprednisolone IV initially, changing to oral prednisolone after clinical improvement. The researchers reviewed the charts of each patient and classified them as having complete or incomplete Kawasaki disease. They assigned z scores for CAA size based on both initial and follow-up echocardiograms. The primary outcome was change in z score of CAA over the first year.

The population of patients treated at each center was significantly different. Center 1 reported older patients (median age 2.6 vs. 2.0 and 1.1), as well as a higher rate of male patients (83% vs. 77% and 58%). However, there was no difference in baseline z scores between centers. Patients who initially received IVIG and corticosteroids were less likely to require additional therapy because of persistent fever versus those receiving IVIG only, or IVIG and infliximab (0% vs. 21% vs. 14%, P = .03).

Patients receiving IVIG and corticosteroids, or IVIG and infliximab, were less likely to have progression of CAA size, with 23% and 24% having an increase in z score of more than 1 versus 58% of those who received IVIG alone. No group had significant differences in maximum z score, the rate of giant aneurysms, or the rate of regression of CAA.

Bottom line

Using IVIG + corticosteroids or IVIG + infliximab versus IVIG alone for children with Kawasaki disease with coronary artery aneurysms decreases the rate of aneurysm enlargement.

Citation

Dionne A et al. Treatment intensification in patients with Kawasaki disease and coronary aneurysm at diagnosis. Pediatrics. May 2019:e20183341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3341.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

IVIG plus steroids or infliximab, or IVIG alone?

IVIG plus steroids or infliximab, or IVIG alone?

Clinical question

Does use of corticosteroids or infliximab in addition to intravenous immunoglobulin improve cardiac outcomes in children with Kawasaki disease and enlarged coronary arteries?

Background

Kawasaki disease is a medium-vessel vasculitis primarily of young children. While the underlying cause remains unknown, treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) substantially lowers the risk of coronary artery aneurysms (CAA), the most serious sequelae of Kawasaki disease. Recent studies have suggested that – in cases of high-risk or treatment-resistant Kawasaki disease – using an immunomodulator, such as a corticosteroid or a TNF-alpha blocker, may improve outcomes, though these studies involved relatively small and homogeneous patient populations. It is unknown if these medications could prevent progression of CAA.

Study design

Retrospective multicenter study.

Setting

Two freestanding children’s hospitals and one mother-child hospital.

Synopsis

The study identified 121 children diagnosed with Kawasaki disease with CAA (z score 2.5-10) from 2008 through 2017 treated at the three study hospitals. Children with giant CAA at the time of diagnosis (z score greater than 10) or significant preexisting congenital heart disease were excluded.

All study hospitals had protocols for treatment of Kawasaki disease: Center 1 used IVIG and corticosteroids, Center 2 used IVIG and infliximab, and Center 3 used IVIG alone. Patients at all centers also received aspirin. Center 1 used methylprednisolone IV initially, changing to oral prednisolone after clinical improvement. The researchers reviewed the charts of each patient and classified them as having complete or incomplete Kawasaki disease. They assigned z scores for CAA size based on both initial and follow-up echocardiograms. The primary outcome was change in z score of CAA over the first year.

The population of patients treated at each center was significantly different. Center 1 reported older patients (median age 2.6 vs. 2.0 and 1.1), as well as a higher rate of male patients (83% vs. 77% and 58%). However, there was no difference in baseline z scores between centers. Patients who initially received IVIG and corticosteroids were less likely to require additional therapy because of persistent fever versus those receiving IVIG only, or IVIG and infliximab (0% vs. 21% vs. 14%, P = .03).

Patients receiving IVIG and corticosteroids, or IVIG and infliximab, were less likely to have progression of CAA size, with 23% and 24% having an increase in z score of more than 1 versus 58% of those who received IVIG alone. No group had significant differences in maximum z score, the rate of giant aneurysms, or the rate of regression of CAA.

Bottom line

Using IVIG + corticosteroids or IVIG + infliximab versus IVIG alone for children with Kawasaki disease with coronary artery aneurysms decreases the rate of aneurysm enlargement.

Citation

Dionne A et al. Treatment intensification in patients with Kawasaki disease and coronary aneurysm at diagnosis. Pediatrics. May 2019:e20183341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3341.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Clinical question

Does use of corticosteroids or infliximab in addition to intravenous immunoglobulin improve cardiac outcomes in children with Kawasaki disease and enlarged coronary arteries?

Background

Kawasaki disease is a medium-vessel vasculitis primarily of young children. While the underlying cause remains unknown, treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) substantially lowers the risk of coronary artery aneurysms (CAA), the most serious sequelae of Kawasaki disease. Recent studies have suggested that – in cases of high-risk or treatment-resistant Kawasaki disease – using an immunomodulator, such as a corticosteroid or a TNF-alpha blocker, may improve outcomes, though these studies involved relatively small and homogeneous patient populations. It is unknown if these medications could prevent progression of CAA.

Study design

Retrospective multicenter study.

Setting

Two freestanding children’s hospitals and one mother-child hospital.

Synopsis

The study identified 121 children diagnosed with Kawasaki disease with CAA (z score 2.5-10) from 2008 through 2017 treated at the three study hospitals. Children with giant CAA at the time of diagnosis (z score greater than 10) or significant preexisting congenital heart disease were excluded.

All study hospitals had protocols for treatment of Kawasaki disease: Center 1 used IVIG and corticosteroids, Center 2 used IVIG and infliximab, and Center 3 used IVIG alone. Patients at all centers also received aspirin. Center 1 used methylprednisolone IV initially, changing to oral prednisolone after clinical improvement. The researchers reviewed the charts of each patient and classified them as having complete or incomplete Kawasaki disease. They assigned z scores for CAA size based on both initial and follow-up echocardiograms. The primary outcome was change in z score of CAA over the first year.

The population of patients treated at each center was significantly different. Center 1 reported older patients (median age 2.6 vs. 2.0 and 1.1), as well as a higher rate of male patients (83% vs. 77% and 58%). However, there was no difference in baseline z scores between centers. Patients who initially received IVIG and corticosteroids were less likely to require additional therapy because of persistent fever versus those receiving IVIG only, or IVIG and infliximab (0% vs. 21% vs. 14%, P = .03).

Patients receiving IVIG and corticosteroids, or IVIG and infliximab, were less likely to have progression of CAA size, with 23% and 24% having an increase in z score of more than 1 versus 58% of those who received IVIG alone. No group had significant differences in maximum z score, the rate of giant aneurysms, or the rate of regression of CAA.

Bottom line

Using IVIG + corticosteroids or IVIG + infliximab versus IVIG alone for children with Kawasaki disease with coronary artery aneurysms decreases the rate of aneurysm enlargement.

Citation

Dionne A et al. Treatment intensification in patients with Kawasaki disease and coronary aneurysm at diagnosis. Pediatrics. May 2019:e20183341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3341.

Dr. Stubblefield is a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

No teen herd immunity for 4CMenB in landmark trial

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – The 4CMenB vaccine didn’t affect carriage of disease-causing genogroups of Neisseria meningitidis in adolescents in the landmark Australian cluster-randomized trial of herd immunity known as the “B Part of It” study, Helen S. Marshall, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This was the largest-ever randomized trial of adolescents vaccinated against meningococcal disease, and the message, albeit somewhat disappointing, is clear: “MenB [Meningococcal serogroup B] vaccine programs should be designed to provide direct protection for those at highest risk of disease,” declared Dr. Marshall, professor of vaccinology and deputy director of the Robinson Research Institute at the University of Adelaide.

In other words, Youths in the age groups at highest risk of disease – infants and adolescents – need to routinely receive the vaccine.

The B Part of It study, whose sheer scope and rigor drew the attention of infectious disease clinical trialists the world over, randomized nearly 35,000 students at all high schools in the state of South Australia – whether urban, rural, or remote – to two doses of the 4CMenB vaccine known as Bexsero or to a nonvaccinated control group. This massive trial entailed training more than 250 nurses in the study procedures and involved 3,100 miles of travel to transport oropharyngeal swab samples obtained from students in outlying areas for centralized laboratory analysis using real-time polymerase chain reaction with meningococcal genotyping, culture for N. meningitidis, and whole-genome sequencing. Samples were obtained on day 1 of the study and 12 months later.

The investigators created widespread regional enthusiasm for this project through adept use of social media and other methods. As a result, 99.5% of students randomized to the intervention arm received one dose, while 97% got two doses. A gratifying unintended consequence of the study was that parents who’d never previously vaccinated their children enrolled them in B Part of It, Dr. Marshall noted.

The impetus for B Part of It was that, while the Australian national health insurance program covers a single dose of meningococcal conjugate MenACWY vaccine given at age 12 months and 14-19 years, MenB vaccine isn’t covered because of uncertainties about cost effectiveness and the vaccine’s impact on meningococcal carriage and herd immunity. B Part of It was designed to resolve those uncertainties.

South Australia has the highest rate of invasive meningococcal disease in the country, and more than 80% of cases there are caused by meningococcal serogroup B. Moreover, 75% of group B cases in South Australia involve the nasty hypervirulent New Zealand strain known as CC 41/44.

The primary outcome in B Part of It was the difference in carriage of the major disease-causing serotypes – groups A, B, C, W, X, and Y – between vaccinated and unvaccinated students at the 1-year follow-up mark. The carriage prevalence of all N. meningitidis in the vaccinated students went from 2.8% at baseline to 4.0% at 12 months, and similarly from 2.6% to 4.7% in unvaccinated controls. More importantly, the prevalence of disease-causing genotypes rose from 1.3% at baseline to 2.4% at follow-up in the vaccinated subjects, with a near-identical pattern seen in controls, where the prevalence rose from 1.4% to 2.4%. In an as-treated analysis, the rate of acquisition of carriage of disease-causing genotypes was identical at 2.0% in both study arms.

The 4CMenB vaccine proved reassuringly safe and effective in preventing meningococcal disease in vaccinated teens. With more than 58,000 doses of the vaccine given in the study, no new safety concerns or signals emerged. And the observed number of cases of invasive meningococcal disease in South Australian adolescent vaccine recipients to date has been significantly lower than expected.

Secondary and exploratory outcomes

Independent risk factors associated with N. meningitidis carriage in the study participants at the 1-year mark included smoking cigarettes or hookah, intimate kissing within the last week, and being in grades 11-12, as opposed to grade 10.

The vaccine had no significant impact on the carriage rate of the hypervirulent New Zealand serogroup B strain. Nor was there a vaccine impact on carriage density, as Mark McMillan, MD, reported elsewhere at ESPID 2019. But while the 4CMenB vaccine had minimal impact upon N. meningitidis carriage density, it was associated with a significant 41% increase in the likelihood of cleared carriage of disease-causing strains at 12 months, added Dr. McMillan, Dr. Marshall’s coinvestigator at University of Adelaide.

What’s next

The ongoing B Part of It School Leaver study is assessing carriage prevalence in vaccinated versus unvaccinated high schoolers in their first year after graduating.

In addition, the B Part of It investigators plan to prospectively study the impact of the 4CMen B vaccine on N. gonorrhoeae disease in an effort to confirm the intriguing findings of an earlier large, retrospective New Zealand case-control study. The Kiwis found that recipients of an outer membrane vesicle MenB vaccine had an adjusted 31% reduction in the risk of gonorrhea. This was the first-ever report of any vaccine effectiveness against this major global public health problem, in which antibiotic resistance is a growing concern (Lancet. 2017 Sep 30;390[10102]:1603-10). Dr. Marshall reported receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, which markets Bexsero and was the major financial supporter of the B Part of It study.

But wait a minute...

Following Dr. Marshall’s report on the B Part of It study, outgoing ESPID president Adam Finn, MD, PhD, presented longitudinal data that he believes raise the possibility that protein-antigen vaccines such as Bexsero, which promote naturally acquired mucosal immunity, may impact on transmission population wide without reliably preventing acquisition. This would stand in stark contrast to conjugate meningococcus vaccines, which have a well-established massive impact on carriage and acquisition of N. meningitidis.

It may be that in studying throat carriage rates once in individuals immunized 12 months earlier, as in the B Part of It study, investigators are not asking the right question, proposed Dr. Finn, professor of pediatrics at the University of Bristol (England).

His research team has been obtaining throat swabs at monthly intervals in a population of 917 high schoolers aged 16-17 years. In 416 of the students, they also have collected saliva samples weekly both before and after immunization with 4CMenB vaccine, analyzing the samples for N. meningitidis by polymerase chain reaction. This is a novel method of studying meningococcal carriage they have found to be both reliable and far more acceptable to patients than oropharyngeal swabbing, which adolescents balk at if asked to do with any frequency (PLoS One. 2019 Feb 11;14[2]:e0209905).

Dr. Finn said that their findings, which need confirmation, suggest that N. meningitidis carriage is usually brief and dynamic. They also have found that carriage density varies markedly from month to month.

“We see much higher-density carriage in the adolescent population in the early months of the year in conjunction, we think, with viral infection with influenza and so forth,” he said, adding that this could have clinical implications. “It feels sort of intuitive that someone walking around with 1,000 or 10,000 times as many meningococci in their throat is more likely to be more infectious to people around them with a very small number, although this hasn’t been formally proven.”

He hopes that the Be on the TEAM (Teenagers Against Meningitis) study will help provide answers. The study is randomizing 24,000 U.K. high school students to vaccination with the meningococcal B protein–antigen vaccines Bexsero or Trumenba or to no vaccine in order to learn if there are significant herd immunity effects.

Dr. Finn’s meningococcal carriage research is funded by the Meningitis Research Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Marshall reported receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, the major sponsor of the B Part of It study.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – The 4CMenB vaccine didn’t affect carriage of disease-causing genogroups of Neisseria meningitidis in adolescents in the landmark Australian cluster-randomized trial of herd immunity known as the “B Part of It” study, Helen S. Marshall, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This was the largest-ever randomized trial of adolescents vaccinated against meningococcal disease, and the message, albeit somewhat disappointing, is clear: “MenB [Meningococcal serogroup B] vaccine programs should be designed to provide direct protection for those at highest risk of disease,” declared Dr. Marshall, professor of vaccinology and deputy director of the Robinson Research Institute at the University of Adelaide.

In other words, Youths in the age groups at highest risk of disease – infants and adolescents – need to routinely receive the vaccine.

The B Part of It study, whose sheer scope and rigor drew the attention of infectious disease clinical trialists the world over, randomized nearly 35,000 students at all high schools in the state of South Australia – whether urban, rural, or remote – to two doses of the 4CMenB vaccine known as Bexsero or to a nonvaccinated control group. This massive trial entailed training more than 250 nurses in the study procedures and involved 3,100 miles of travel to transport oropharyngeal swab samples obtained from students in outlying areas for centralized laboratory analysis using real-time polymerase chain reaction with meningococcal genotyping, culture for N. meningitidis, and whole-genome sequencing. Samples were obtained on day 1 of the study and 12 months later.

The investigators created widespread regional enthusiasm for this project through adept use of social media and other methods. As a result, 99.5% of students randomized to the intervention arm received one dose, while 97% got two doses. A gratifying unintended consequence of the study was that parents who’d never previously vaccinated their children enrolled them in B Part of It, Dr. Marshall noted.

The impetus for B Part of It was that, while the Australian national health insurance program covers a single dose of meningococcal conjugate MenACWY vaccine given at age 12 months and 14-19 years, MenB vaccine isn’t covered because of uncertainties about cost effectiveness and the vaccine’s impact on meningococcal carriage and herd immunity. B Part of It was designed to resolve those uncertainties.

South Australia has the highest rate of invasive meningococcal disease in the country, and more than 80% of cases there are caused by meningococcal serogroup B. Moreover, 75% of group B cases in South Australia involve the nasty hypervirulent New Zealand strain known as CC 41/44.

The primary outcome in B Part of It was the difference in carriage of the major disease-causing serotypes – groups A, B, C, W, X, and Y – between vaccinated and unvaccinated students at the 1-year follow-up mark. The carriage prevalence of all N. meningitidis in the vaccinated students went from 2.8% at baseline to 4.0% at 12 months, and similarly from 2.6% to 4.7% in unvaccinated controls. More importantly, the prevalence of disease-causing genotypes rose from 1.3% at baseline to 2.4% at follow-up in the vaccinated subjects, with a near-identical pattern seen in controls, where the prevalence rose from 1.4% to 2.4%. In an as-treated analysis, the rate of acquisition of carriage of disease-causing genotypes was identical at 2.0% in both study arms.

The 4CMenB vaccine proved reassuringly safe and effective in preventing meningococcal disease in vaccinated teens. With more than 58,000 doses of the vaccine given in the study, no new safety concerns or signals emerged. And the observed number of cases of invasive meningococcal disease in South Australian adolescent vaccine recipients to date has been significantly lower than expected.

Secondary and exploratory outcomes

Independent risk factors associated with N. meningitidis carriage in the study participants at the 1-year mark included smoking cigarettes or hookah, intimate kissing within the last week, and being in grades 11-12, as opposed to grade 10.

The vaccine had no significant impact on the carriage rate of the hypervirulent New Zealand serogroup B strain. Nor was there a vaccine impact on carriage density, as Mark McMillan, MD, reported elsewhere at ESPID 2019. But while the 4CMenB vaccine had minimal impact upon N. meningitidis carriage density, it was associated with a significant 41% increase in the likelihood of cleared carriage of disease-causing strains at 12 months, added Dr. McMillan, Dr. Marshall’s coinvestigator at University of Adelaide.

What’s next

The ongoing B Part of It School Leaver study is assessing carriage prevalence in vaccinated versus unvaccinated high schoolers in their first year after graduating.

In addition, the B Part of It investigators plan to prospectively study the impact of the 4CMen B vaccine on N. gonorrhoeae disease in an effort to confirm the intriguing findings of an earlier large, retrospective New Zealand case-control study. The Kiwis found that recipients of an outer membrane vesicle MenB vaccine had an adjusted 31% reduction in the risk of gonorrhea. This was the first-ever report of any vaccine effectiveness against this major global public health problem, in which antibiotic resistance is a growing concern (Lancet. 2017 Sep 30;390[10102]:1603-10). Dr. Marshall reported receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, which markets Bexsero and was the major financial supporter of the B Part of It study.

But wait a minute...

Following Dr. Marshall’s report on the B Part of It study, outgoing ESPID president Adam Finn, MD, PhD, presented longitudinal data that he believes raise the possibility that protein-antigen vaccines such as Bexsero, which promote naturally acquired mucosal immunity, may impact on transmission population wide without reliably preventing acquisition. This would stand in stark contrast to conjugate meningococcus vaccines, which have a well-established massive impact on carriage and acquisition of N. meningitidis.

It may be that in studying throat carriage rates once in individuals immunized 12 months earlier, as in the B Part of It study, investigators are not asking the right question, proposed Dr. Finn, professor of pediatrics at the University of Bristol (England).

His research team has been obtaining throat swabs at monthly intervals in a population of 917 high schoolers aged 16-17 years. In 416 of the students, they also have collected saliva samples weekly both before and after immunization with 4CMenB vaccine, analyzing the samples for N. meningitidis by polymerase chain reaction. This is a novel method of studying meningococcal carriage they have found to be both reliable and far more acceptable to patients than oropharyngeal swabbing, which adolescents balk at if asked to do with any frequency (PLoS One. 2019 Feb 11;14[2]:e0209905).

Dr. Finn said that their findings, which need confirmation, suggest that N. meningitidis carriage is usually brief and dynamic. They also have found that carriage density varies markedly from month to month.

“We see much higher-density carriage in the adolescent population in the early months of the year in conjunction, we think, with viral infection with influenza and so forth,” he said, adding that this could have clinical implications. “It feels sort of intuitive that someone walking around with 1,000 or 10,000 times as many meningococci in their throat is more likely to be more infectious to people around them with a very small number, although this hasn’t been formally proven.”

He hopes that the Be on the TEAM (Teenagers Against Meningitis) study will help provide answers. The study is randomizing 24,000 U.K. high school students to vaccination with the meningococcal B protein–antigen vaccines Bexsero or Trumenba or to no vaccine in order to learn if there are significant herd immunity effects.

Dr. Finn’s meningococcal carriage research is funded by the Meningitis Research Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Marshall reported receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, the major sponsor of the B Part of It study.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – The 4CMenB vaccine didn’t affect carriage of disease-causing genogroups of Neisseria meningitidis in adolescents in the landmark Australian cluster-randomized trial of herd immunity known as the “B Part of It” study, Helen S. Marshall, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

This was the largest-ever randomized trial of adolescents vaccinated against meningococcal disease, and the message, albeit somewhat disappointing, is clear: “MenB [Meningococcal serogroup B] vaccine programs should be designed to provide direct protection for those at highest risk of disease,” declared Dr. Marshall, professor of vaccinology and deputy director of the Robinson Research Institute at the University of Adelaide.

In other words, Youths in the age groups at highest risk of disease – infants and adolescents – need to routinely receive the vaccine.

The B Part of It study, whose sheer scope and rigor drew the attention of infectious disease clinical trialists the world over, randomized nearly 35,000 students at all high schools in the state of South Australia – whether urban, rural, or remote – to two doses of the 4CMenB vaccine known as Bexsero or to a nonvaccinated control group. This massive trial entailed training more than 250 nurses in the study procedures and involved 3,100 miles of travel to transport oropharyngeal swab samples obtained from students in outlying areas for centralized laboratory analysis using real-time polymerase chain reaction with meningococcal genotyping, culture for N. meningitidis, and whole-genome sequencing. Samples were obtained on day 1 of the study and 12 months later.

The investigators created widespread regional enthusiasm for this project through adept use of social media and other methods. As a result, 99.5% of students randomized to the intervention arm received one dose, while 97% got two doses. A gratifying unintended consequence of the study was that parents who’d never previously vaccinated their children enrolled them in B Part of It, Dr. Marshall noted.

The impetus for B Part of It was that, while the Australian national health insurance program covers a single dose of meningococcal conjugate MenACWY vaccine given at age 12 months and 14-19 years, MenB vaccine isn’t covered because of uncertainties about cost effectiveness and the vaccine’s impact on meningococcal carriage and herd immunity. B Part of It was designed to resolve those uncertainties.

South Australia has the highest rate of invasive meningococcal disease in the country, and more than 80% of cases there are caused by meningococcal serogroup B. Moreover, 75% of group B cases in South Australia involve the nasty hypervirulent New Zealand strain known as CC 41/44.

The primary outcome in B Part of It was the difference in carriage of the major disease-causing serotypes – groups A, B, C, W, X, and Y – between vaccinated and unvaccinated students at the 1-year follow-up mark. The carriage prevalence of all N. meningitidis in the vaccinated students went from 2.8% at baseline to 4.0% at 12 months, and similarly from 2.6% to 4.7% in unvaccinated controls. More importantly, the prevalence of disease-causing genotypes rose from 1.3% at baseline to 2.4% at follow-up in the vaccinated subjects, with a near-identical pattern seen in controls, where the prevalence rose from 1.4% to 2.4%. In an as-treated analysis, the rate of acquisition of carriage of disease-causing genotypes was identical at 2.0% in both study arms.

The 4CMenB vaccine proved reassuringly safe and effective in preventing meningococcal disease in vaccinated teens. With more than 58,000 doses of the vaccine given in the study, no new safety concerns or signals emerged. And the observed number of cases of invasive meningococcal disease in South Australian adolescent vaccine recipients to date has been significantly lower than expected.

Secondary and exploratory outcomes

Independent risk factors associated with N. meningitidis carriage in the study participants at the 1-year mark included smoking cigarettes or hookah, intimate kissing within the last week, and being in grades 11-12, as opposed to grade 10.

The vaccine had no significant impact on the carriage rate of the hypervirulent New Zealand serogroup B strain. Nor was there a vaccine impact on carriage density, as Mark McMillan, MD, reported elsewhere at ESPID 2019. But while the 4CMenB vaccine had minimal impact upon N. meningitidis carriage density, it was associated with a significant 41% increase in the likelihood of cleared carriage of disease-causing strains at 12 months, added Dr. McMillan, Dr. Marshall’s coinvestigator at University of Adelaide.

What’s next

The ongoing B Part of It School Leaver study is assessing carriage prevalence in vaccinated versus unvaccinated high schoolers in their first year after graduating.

In addition, the B Part of It investigators plan to prospectively study the impact of the 4CMen B vaccine on N. gonorrhoeae disease in an effort to confirm the intriguing findings of an earlier large, retrospective New Zealand case-control study. The Kiwis found that recipients of an outer membrane vesicle MenB vaccine had an adjusted 31% reduction in the risk of gonorrhea. This was the first-ever report of any vaccine effectiveness against this major global public health problem, in which antibiotic resistance is a growing concern (Lancet. 2017 Sep 30;390[10102]:1603-10). Dr. Marshall reported receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, which markets Bexsero and was the major financial supporter of the B Part of It study.

But wait a minute...

Following Dr. Marshall’s report on the B Part of It study, outgoing ESPID president Adam Finn, MD, PhD, presented longitudinal data that he believes raise the possibility that protein-antigen vaccines such as Bexsero, which promote naturally acquired mucosal immunity, may impact on transmission population wide without reliably preventing acquisition. This would stand in stark contrast to conjugate meningococcus vaccines, which have a well-established massive impact on carriage and acquisition of N. meningitidis.

It may be that in studying throat carriage rates once in individuals immunized 12 months earlier, as in the B Part of It study, investigators are not asking the right question, proposed Dr. Finn, professor of pediatrics at the University of Bristol (England).

His research team has been obtaining throat swabs at monthly intervals in a population of 917 high schoolers aged 16-17 years. In 416 of the students, they also have collected saliva samples weekly both before and after immunization with 4CMenB vaccine, analyzing the samples for N. meningitidis by polymerase chain reaction. This is a novel method of studying meningococcal carriage they have found to be both reliable and far more acceptable to patients than oropharyngeal swabbing, which adolescents balk at if asked to do with any frequency (PLoS One. 2019 Feb 11;14[2]:e0209905).

Dr. Finn said that their findings, which need confirmation, suggest that N. meningitidis carriage is usually brief and dynamic. They also have found that carriage density varies markedly from month to month.

“We see much higher-density carriage in the adolescent population in the early months of the year in conjunction, we think, with viral infection with influenza and so forth,” he said, adding that this could have clinical implications. “It feels sort of intuitive that someone walking around with 1,000 or 10,000 times as many meningococci in their throat is more likely to be more infectious to people around them with a very small number, although this hasn’t been formally proven.”

He hopes that the Be on the TEAM (Teenagers Against Meningitis) study will help provide answers. The study is randomizing 24,000 U.K. high school students to vaccination with the meningococcal B protein–antigen vaccines Bexsero or Trumenba or to no vaccine in order to learn if there are significant herd immunity effects.

Dr. Finn’s meningococcal carriage research is funded by the Meningitis Research Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Marshall reported receiving research funding from GlaxoSmithKline, the major sponsor of the B Part of It study.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

Erythematous Papules and Pustules on the Nose

The Diagnosis: Granulosis Rubra Nasi

A history of prominent nasal sweating was later elicited and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with granulosis rubra nasi. She was instructed to continue daily use of topical pimecrolimus with the addition of topical atropine, resulting in complete resolution of the eruption at 6-week follow-up (Figure, A). She was then maintained on topical atropine monotherapy, only noting recurrence with cessation of the atropine (Figure, B).

Other successful treatment regimens of granulosis rubra nasi include injection of botulinum toxin into the nose,1 monotherapy with topical tacrolimus,2 topical indomethacin, steroids, and cryotherapy, among other modalities.1 Topical atropine and pimecrolimus were selected as first-line agents for treating our pediatric patient due to tolerability and their anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic properties.

Granulosis rubra nasi is a form of focal hyperhidrosis that presents as erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles of the midface, especially the nose.3 It is a fairly rare condition that can mimic many other common clinical entities, including comedonal acne, nevus comedonicus, periorificial dermatitis, and tinea faciei, but is resistant to treatments aimed at these disorders. It was first described as a "peculiar disease of the skin of the nose in children" in a case report by Jadassohn4 in 1901. It is most common in children aged 7 to 12 years and typically resolves at puberty; adults rarely are affected. Although the etiology has not yet been elucidated, autosomal-dominant transmission has been described, and the cutaneous changes are hypothesized to be secondary to hyperhidrosis.5 This postulation is further corroborated by a case report of a pheochromocytoma-associated granulosis rubra nasi that resolved with surgical excision of the pheochromocytoma.6 It is not uncommon for patients to have concomitant palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and acrocyanosis.5 Histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis, but when performed, it discloses a mononuclear cellular infiltrate surrounding eccrine sweat ducts, blood vessels, and lymphatics without other abnormalities of the epidermis or pilosebaceous unit.1-3,7

- Grazziotin TC, Buffon RB, Da Silva Manzoni AP, et al. Treatment of granulosis rubra nasi with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1298-1299.

- Kumar P, Gosai A, Mondal AK, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi: a rare condition treated successfully with topical tacrolimus. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:E5.

- Sargunam C, Thomas J, Ahmed NA. Granulosis rubra nasi. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:208-209.

- Jadassohn J. Ueber eine eigenartige erkrankung der nasenhaut bei kindern. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;58:145-158.

- Hellier FF. Granulosis rubra nasi in a mother and daughter. Br Med J. 1937;2:1068.

- Heid E, Samain F, Jelen G, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi and pheochromocytoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:106-108.

- Akhdari N. Granulosis rubra nasi. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:396.

The Diagnosis: Granulosis Rubra Nasi

A history of prominent nasal sweating was later elicited and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with granulosis rubra nasi. She was instructed to continue daily use of topical pimecrolimus with the addition of topical atropine, resulting in complete resolution of the eruption at 6-week follow-up (Figure, A). She was then maintained on topical atropine monotherapy, only noting recurrence with cessation of the atropine (Figure, B).

Other successful treatment regimens of granulosis rubra nasi include injection of botulinum toxin into the nose,1 monotherapy with topical tacrolimus,2 topical indomethacin, steroids, and cryotherapy, among other modalities.1 Topical atropine and pimecrolimus were selected as first-line agents for treating our pediatric patient due to tolerability and their anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic properties.

Granulosis rubra nasi is a form of focal hyperhidrosis that presents as erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles of the midface, especially the nose.3 It is a fairly rare condition that can mimic many other common clinical entities, including comedonal acne, nevus comedonicus, periorificial dermatitis, and tinea faciei, but is resistant to treatments aimed at these disorders. It was first described as a "peculiar disease of the skin of the nose in children" in a case report by Jadassohn4 in 1901. It is most common in children aged 7 to 12 years and typically resolves at puberty; adults rarely are affected. Although the etiology has not yet been elucidated, autosomal-dominant transmission has been described, and the cutaneous changes are hypothesized to be secondary to hyperhidrosis.5 This postulation is further corroborated by a case report of a pheochromocytoma-associated granulosis rubra nasi that resolved with surgical excision of the pheochromocytoma.6 It is not uncommon for patients to have concomitant palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and acrocyanosis.5 Histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis, but when performed, it discloses a mononuclear cellular infiltrate surrounding eccrine sweat ducts, blood vessels, and lymphatics without other abnormalities of the epidermis or pilosebaceous unit.1-3,7

The Diagnosis: Granulosis Rubra Nasi

A history of prominent nasal sweating was later elicited and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with granulosis rubra nasi. She was instructed to continue daily use of topical pimecrolimus with the addition of topical atropine, resulting in complete resolution of the eruption at 6-week follow-up (Figure, A). She was then maintained on topical atropine monotherapy, only noting recurrence with cessation of the atropine (Figure, B).

Other successful treatment regimens of granulosis rubra nasi include injection of botulinum toxin into the nose,1 monotherapy with topical tacrolimus,2 topical indomethacin, steroids, and cryotherapy, among other modalities.1 Topical atropine and pimecrolimus were selected as first-line agents for treating our pediatric patient due to tolerability and their anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic properties.

Granulosis rubra nasi is a form of focal hyperhidrosis that presents as erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles of the midface, especially the nose.3 It is a fairly rare condition that can mimic many other common clinical entities, including comedonal acne, nevus comedonicus, periorificial dermatitis, and tinea faciei, but is resistant to treatments aimed at these disorders. It was first described as a "peculiar disease of the skin of the nose in children" in a case report by Jadassohn4 in 1901. It is most common in children aged 7 to 12 years and typically resolves at puberty; adults rarely are affected. Although the etiology has not yet been elucidated, autosomal-dominant transmission has been described, and the cutaneous changes are hypothesized to be secondary to hyperhidrosis.5 This postulation is further corroborated by a case report of a pheochromocytoma-associated granulosis rubra nasi that resolved with surgical excision of the pheochromocytoma.6 It is not uncommon for patients to have concomitant palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and acrocyanosis.5 Histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis, but when performed, it discloses a mononuclear cellular infiltrate surrounding eccrine sweat ducts, blood vessels, and lymphatics without other abnormalities of the epidermis or pilosebaceous unit.1-3,7

- Grazziotin TC, Buffon RB, Da Silva Manzoni AP, et al. Treatment of granulosis rubra nasi with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1298-1299.

- Kumar P, Gosai A, Mondal AK, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi: a rare condition treated successfully with topical tacrolimus. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:E5.

- Sargunam C, Thomas J, Ahmed NA. Granulosis rubra nasi. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:208-209.

- Jadassohn J. Ueber eine eigenartige erkrankung der nasenhaut bei kindern. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;58:145-158.

- Hellier FF. Granulosis rubra nasi in a mother and daughter. Br Med J. 1937;2:1068.

- Heid E, Samain F, Jelen G, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi and pheochromocytoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:106-108.

- Akhdari N. Granulosis rubra nasi. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:396.

- Grazziotin TC, Buffon RB, Da Silva Manzoni AP, et al. Treatment of granulosis rubra nasi with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1298-1299.

- Kumar P, Gosai A, Mondal AK, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi: a rare condition treated successfully with topical tacrolimus. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:E5.

- Sargunam C, Thomas J, Ahmed NA. Granulosis rubra nasi. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:208-209.

- Jadassohn J. Ueber eine eigenartige erkrankung der nasenhaut bei kindern. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;58:145-158.

- Hellier FF. Granulosis rubra nasi in a mother and daughter. Br Med J. 1937;2:1068.

- Heid E, Samain F, Jelen G, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi and pheochromocytoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:106-108.

- Akhdari N. Granulosis rubra nasi. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:396.

A healthy 9-year-old girl presented with a 2-year history of erythematous papules and pustules on the nose. There was no involvement of the rest of the face or body. At the time of presentation, she had been treated with several topical therapies including steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antibiotics, and retinoids without improvement. A potassium hydroxide preparation from a pustule was performed and revealed only normal keratinocytes.

Short-term parenteral antibiotics effective for bacteremic UTI in young infants

according to a study.

While previous studies have shown short-term parenteral antibiotic therapy to be safe and equally effective in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), short-term therapy safety in bacteremic UTI had not been established, Sanyukta Desai, MD, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and associates wrote in Pediatrics.

“As a result, infants with bacteremic UTI often receive prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics, which can lead to long hospitalizations and increased costs,” they said.

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, Dr. Desai and associates analyzed a group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to a group of 11 participating EDs between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016, if they had a UTI caused by a bacterial pathogen. Half of the infants were administered parenteral antibiotics for 7 days or less before being switched to oral antibiotics, and the rest were given parenteral antibiotics for more than 7 days before switching to oral. Infants were more likely to receive long-term parenteral treatment if they were ill appearing and had growth of a non–Escherichia coli organism.

Six infants (two in the short-term group, four in the long-term group) had a recurrent UTI, each one diagnosed between 15 and 30 days after discharge; the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 3% (95% confidence interval, –5.8 to 12.7). Two of the infants in the long-term group with a recurrent UTI had a different organism than during the index infection. When comparing only the infants with growth of the same pathogen that caused the index UTI, the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 0.2% (95% CI, –7.8 to 8.3).

A total of 15 infants (6 in the short-term group, 9 in the long-term group) had 30-day all-cause reutilization, with no significant difference between groups (adjusted risk difference, 3%; 95% CI, –14.6 to 20.4).

Mean length of stay was significantly longer in the long-term treatment group, compared with the short-term group (11 days vs. 5 days; adjusted mean difference, 6 days; 95% CI, 4.0-8.8).

No infants experienced a serious adverse event such as ICU readmission, need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor use, or signs of neurologic sequelae within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization, the investigators noted. Peripherally inserted central catheters were required in 13 infants; of these, 1 infant had to revisit an ED because of a related mechanical complication.

“Researchers in future prospective studies should seek to establish the bioavailability and optimal dosing of oral antibiotics in young infants and assess if there are particular subpopulations of infants with bacteremic UTI who may benefit from longer courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy,” Dr. Desai and associates concluded.

In a related editorial, Natalia V. Leva, MD, and Hillary L. Copp, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that the study represents a “critical piece of a complicated puzzle that not only includes minimum duration of parenteral antibiotic treatment but also involves bioavailability of antimicrobial agents in infants and total treatment duration, which includes parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.”

The question that remains is how long a duration of parenteral antibiotic is necessary, Dr. Leva and Dr. Copp wrote. “Desai et al. used a relatively arbitrary cutoff of 7 days on the basis of the distribution of antibiotic course among their patient population; however, this is likely more a reflection of clinical practice than it is evidence based.” They concluded that this study provided evidence that a “short course of parenteral antibiotics in infants [aged 60 days or younger] with bacteremic UTI is safe and effective. Although the current study does not address total duration of antibiotics [parenteral and oral], it does shine a light on where we should focus future research endeavors.”

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant. The editorialists had no relevant conflicts of interest and received no external funding.

SOURCEs: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844; Leva et al. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1611.

according to a study.

While previous studies have shown short-term parenteral antibiotic therapy to be safe and equally effective in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), short-term therapy safety in bacteremic UTI had not been established, Sanyukta Desai, MD, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and associates wrote in Pediatrics.

“As a result, infants with bacteremic UTI often receive prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics, which can lead to long hospitalizations and increased costs,” they said.

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, Dr. Desai and associates analyzed a group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to a group of 11 participating EDs between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016, if they had a UTI caused by a bacterial pathogen. Half of the infants were administered parenteral antibiotics for 7 days or less before being switched to oral antibiotics, and the rest were given parenteral antibiotics for more than 7 days before switching to oral. Infants were more likely to receive long-term parenteral treatment if they were ill appearing and had growth of a non–Escherichia coli organism.

Six infants (two in the short-term group, four in the long-term group) had a recurrent UTI, each one diagnosed between 15 and 30 days after discharge; the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 3% (95% confidence interval, –5.8 to 12.7). Two of the infants in the long-term group with a recurrent UTI had a different organism than during the index infection. When comparing only the infants with growth of the same pathogen that caused the index UTI, the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 0.2% (95% CI, –7.8 to 8.3).

A total of 15 infants (6 in the short-term group, 9 in the long-term group) had 30-day all-cause reutilization, with no significant difference between groups (adjusted risk difference, 3%; 95% CI, –14.6 to 20.4).

Mean length of stay was significantly longer in the long-term treatment group, compared with the short-term group (11 days vs. 5 days; adjusted mean difference, 6 days; 95% CI, 4.0-8.8).

No infants experienced a serious adverse event such as ICU readmission, need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor use, or signs of neurologic sequelae within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization, the investigators noted. Peripherally inserted central catheters were required in 13 infants; of these, 1 infant had to revisit an ED because of a related mechanical complication.

“Researchers in future prospective studies should seek to establish the bioavailability and optimal dosing of oral antibiotics in young infants and assess if there are particular subpopulations of infants with bacteremic UTI who may benefit from longer courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy,” Dr. Desai and associates concluded.

In a related editorial, Natalia V. Leva, MD, and Hillary L. Copp, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that the study represents a “critical piece of a complicated puzzle that not only includes minimum duration of parenteral antibiotic treatment but also involves bioavailability of antimicrobial agents in infants and total treatment duration, which includes parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.”

The question that remains is how long a duration of parenteral antibiotic is necessary, Dr. Leva and Dr. Copp wrote. “Desai et al. used a relatively arbitrary cutoff of 7 days on the basis of the distribution of antibiotic course among their patient population; however, this is likely more a reflection of clinical practice than it is evidence based.” They concluded that this study provided evidence that a “short course of parenteral antibiotics in infants [aged 60 days or younger] with bacteremic UTI is safe and effective. Although the current study does not address total duration of antibiotics [parenteral and oral], it does shine a light on where we should focus future research endeavors.”

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant. The editorialists had no relevant conflicts of interest and received no external funding.

SOURCEs: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844; Leva et al. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1611.

according to a study.

While previous studies have shown short-term parenteral antibiotic therapy to be safe and equally effective in uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs), short-term therapy safety in bacteremic UTI had not been established, Sanyukta Desai, MD, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and associates wrote in Pediatrics.

“As a result, infants with bacteremic UTI often receive prolonged courses of parenteral antibiotics, which can lead to long hospitalizations and increased costs,” they said.

In a multicenter, retrospective cohort study, Dr. Desai and associates analyzed a group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to a group of 11 participating EDs between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2016, if they had a UTI caused by a bacterial pathogen. Half of the infants were administered parenteral antibiotics for 7 days or less before being switched to oral antibiotics, and the rest were given parenteral antibiotics for more than 7 days before switching to oral. Infants were more likely to receive long-term parenteral treatment if they were ill appearing and had growth of a non–Escherichia coli organism.

Six infants (two in the short-term group, four in the long-term group) had a recurrent UTI, each one diagnosed between 15 and 30 days after discharge; the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 3% (95% confidence interval, –5.8 to 12.7). Two of the infants in the long-term group with a recurrent UTI had a different organism than during the index infection. When comparing only the infants with growth of the same pathogen that caused the index UTI, the adjusted risk difference between the two groups was 0.2% (95% CI, –7.8 to 8.3).

A total of 15 infants (6 in the short-term group, 9 in the long-term group) had 30-day all-cause reutilization, with no significant difference between groups (adjusted risk difference, 3%; 95% CI, –14.6 to 20.4).

Mean length of stay was significantly longer in the long-term treatment group, compared with the short-term group (11 days vs. 5 days; adjusted mean difference, 6 days; 95% CI, 4.0-8.8).

No infants experienced a serious adverse event such as ICU readmission, need for mechanical ventilation or vasopressor use, or signs of neurologic sequelae within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization, the investigators noted. Peripherally inserted central catheters were required in 13 infants; of these, 1 infant had to revisit an ED because of a related mechanical complication.

“Researchers in future prospective studies should seek to establish the bioavailability and optimal dosing of oral antibiotics in young infants and assess if there are particular subpopulations of infants with bacteremic UTI who may benefit from longer courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy,” Dr. Desai and associates concluded.

In a related editorial, Natalia V. Leva, MD, and Hillary L. Copp, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, noted that the study represents a “critical piece of a complicated puzzle that not only includes minimum duration of parenteral antibiotic treatment but also involves bioavailability of antimicrobial agents in infants and total treatment duration, which includes parenteral and oral antibiotic therapy.”

The question that remains is how long a duration of parenteral antibiotic is necessary, Dr. Leva and Dr. Copp wrote. “Desai et al. used a relatively arbitrary cutoff of 7 days on the basis of the distribution of antibiotic course among their patient population; however, this is likely more a reflection of clinical practice than it is evidence based.” They concluded that this study provided evidence that a “short course of parenteral antibiotics in infants [aged 60 days or younger] with bacteremic UTI is safe and effective. Although the current study does not address total duration of antibiotics [parenteral and oral], it does shine a light on where we should focus future research endeavors.”

The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant. The editorialists had no relevant conflicts of interest and received no external funding.

SOURCEs: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844; Leva et al. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1611.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Urinary tract infection (UTI) recurrence and hospital reutilization was similar in infants with bacteremic UTIs, regardless of parenteral antibiotic treatment duration of 7 days or less or greater than 7 days prior to oral antibiotics.

Major finding: The adjusted risk difference for both infection recurrence and hospital reutilization was 3% and was nonsignificant in both cases.

Study details: A group of 115 infants aged 60 days or younger who were admitted to an ED with a bacteremic UTI.

Disclosures: The study authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest. The funding of the study was supported in part by a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant and an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant.

Source: Desai S et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3844.

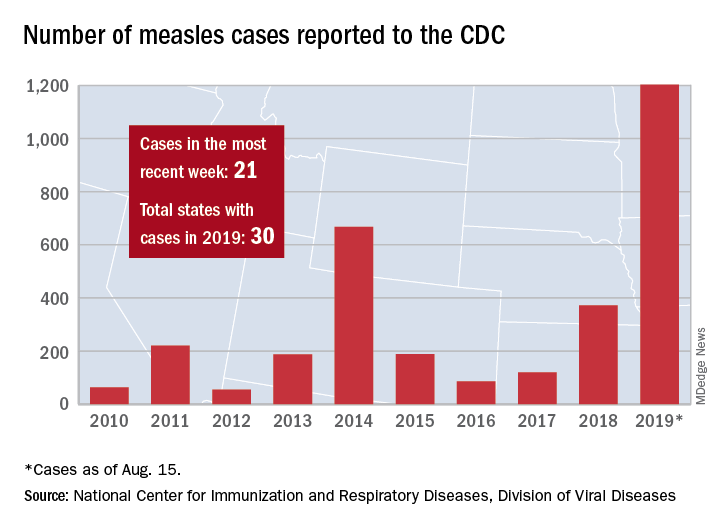

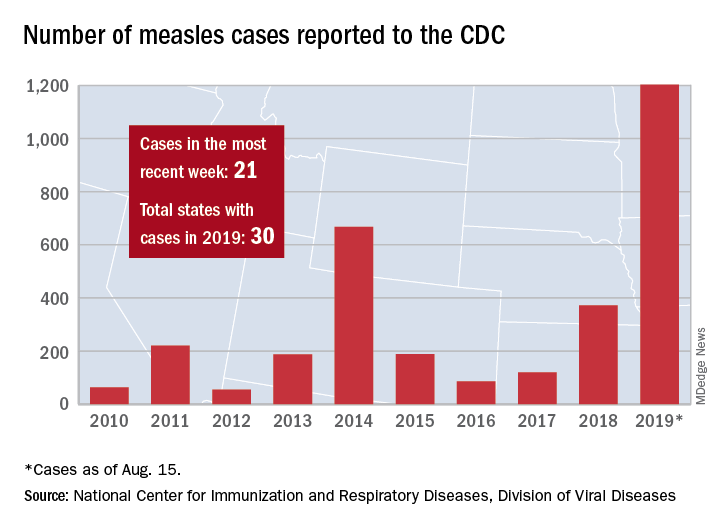

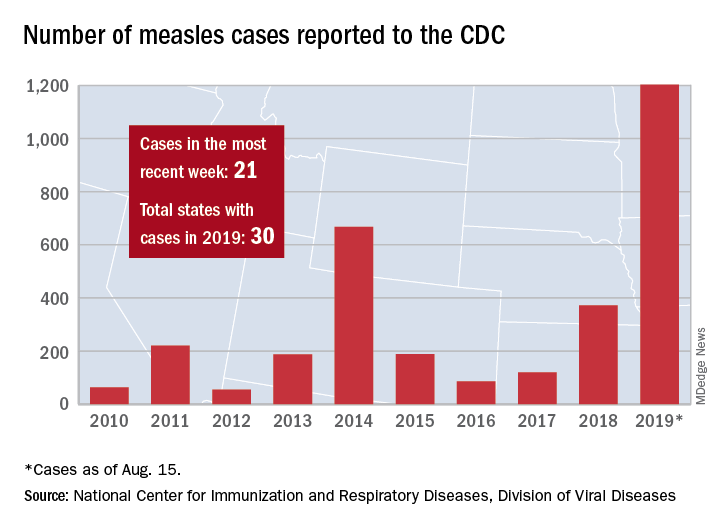

New measles outbreak reported in western N.Y.

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

A new measles outbreak in western New York has affected five people within a Mennonite community, according to the New York State Department of Health.

The five cases in Wyoming County, located east of Buffalo, were reported Aug. 8 and no further cases have been confirmed as of Aug. 16, the county health department said on its website.

Those five cases, along with six new cases in Rockland County, N.Y., and 10 more around the country, brought the total for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s latest reporting week to 21 and the total for the year to 1,203, the CDC said Aug. 19.

Along with Wyoming County and Rockland County (296 cases since Sept. 2018), the CDC currently is tracking outbreaks in New York City (653 cases since Sept. 2018), Washington state (85 cases in 2019; 13 in the current outbreak), California (65 cases in 2019; 5 in the current outbreak), and Texas (21 cases in 2019; 6 in the current outbreak).

“More than 75% of the cases this year are linked to outbreaks in New York and New York City,” the CDC said on its website, while also noting that “124 of the people who got measles this year were hospitalized, and 64 reported having complications, including pneumonia and encephalitis.”

Fluoride exposure during pregnancy tied to lower IQ score in children

with boys having a lower mean score than girls, according to a recent prospective, multicenter birth cohort study.

“These findings were observed at fluoride levels typically found in white North American women,” wrote Rivka Green, York University, Toronto, and colleagues. “This indicates the possible need to reduce fluoride intake during pregnancy.”

This study confirms findings in a 2017 study suggesting a relationship between maternal fluoride levels and children’s later cognitive scores.

Ms. Green and colleagues evaluated 512 mother-child pairs in the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) cohort from six Canadian cities. The children were born between 2008 and 2012, underwent neurodevelopmental testing between 3 and 4 years, and were assessed using the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition. Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) test.

Of these, 400 mother-child pairs had data on fluoride intake, IQ, and complete covariate data; 141 of these mothers lived in areas with fluoridated tap water, while 228 mothers lived in areas without fluoridated tap water. Maternal urinary fluoride adjusted for specific gravity (MUFSG) was averaged across three trimesters of data, and the estimated fluoride level was obtained through self-reported exposure by women included in the study.

The researchers found mothers living in areas with fluoridated water had significantly higher MUFSG levels (0.69 mg/L), compared with women in areas without fluoridated water (0.40 mg/L; P equals .001). The median estimated fluoride intake was significantly higher among women living in areas with fluoridated water (0.93 mg per day) than in women who did not live in areas with fluoridated water (0.30 mg per day; P less than .001).

Overall, children scored a mean 107.16 (range, 52-143) on the IQ test, and girls had significantly higher mean IQ scores than did boys (109.56 vs. 104.61; P = .001). After adjusting for covariates of maternal age, race, parity, smoking, and alcohol status during pregnancy, child gender, gestational age, and birth weight, the researchers found a significant interaction between MUFSG and the child’s gender (P = .02), and a 1-mg/L MUFSG increase was associated with a decrease in 4.49 IQ points in boys (95% confidence interval, −8.38 to −0.60) but not girls. There also was an association between 1-mg higher daily intake of maternal fluoride intake and decreased IQ score in both boys and girls (−3.66; 95% CI, −7.16 to −0.15 ; P = .04).

Ms. Green and her colleagues acknowledged several limitations with the study, such as the short half-life of urinary fluoride and the potential inaccuracy of maternal urinary samples at predicting fetal exposure to fluoride, the self-reported nature of estimated fluoride consumption, lack of availability of maternal IQ data, and not including postnatal exposure and consumption of fluoride.

In a related editorial, David C. Bellinger, PhD, MSc, referred to a previous prospective study in Mexico City by Bashash et al. that found a maternal fluoride level of 0.9 mg/L was associated with a decrease in cognitive scores in children at 4 years and between 6 years and 12 years (Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(9):097017. doi: 10.1289/EHP655), and noted the effect sizes seen in the Mexico City study were similar to those reported by Green et al. “If the effect sizes reported by Green et al. and others are valid, the total cognitive loss at the population level that might be associated with children’s prenatal exposure to fluoride could be substantial,” he said.

The study raises many questions, including whether there is a concentration where neurotoxicity risk is negligible, if gender plays a role (there was no gender risk difference in Bashash et al.), whether other developmental domains are affected apart from IQ, and if postnatal exposure carries a risk, Dr. Bellinger said. “The findings of Green et al. and others indicate that a dispassionate and tempered discussion of fluoride’s potential neurotoxicity is warranted, including consideration of what additional research is needed to reach more definitive conclusions about the implications, if any, for public health,” he said.

Dimitri A. Christakis, MD, MPH, editor of JAMA Pediatrics and director of the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, said in an editor’s note that it was not an easy decision to publish the article because of the potential implications of the findings.

“The mission of the journal is to ensure that child health is optimized by bringing the best available evidence to the fore,” he said. “Publishing it serves as testament to the fact that JAMA Pediatrics is committed to disseminating the best science based entirely on the rigor of the methods and the soundness of the hypotheses tested, regardless of how contentious the results may be.”

However, “scientific inquiry is an iterative process,” Dr. Christakis said, and rarely does a single study provide “definitive evidence.

“We hope that purveyors and consumers of these findings are mindful of that as the implications of this study are debated in the public arena.”

This study was funded in a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Science, and the MIREC Study was funded by Chemicals Management Plan at Health Canada, the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Dr. Bruce Lanphear reported being an unpaid expert witness for an upcoming case involving the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and water fluoridation. Dr. Richard Hornung reported receiving personal fees from York University. Dr. E. Angeles Martinez-Mier reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr. Bellinger reported no relevant conflicts of interest with regard to his editorial.

SOURCEs: Green R et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1729; Bellinger. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/ jamapediatrics.2019.1728.

with boys having a lower mean score than girls, according to a recent prospective, multicenter birth cohort study.

“These findings were observed at fluoride levels typically found in white North American women,” wrote Rivka Green, York University, Toronto, and colleagues. “This indicates the possible need to reduce fluoride intake during pregnancy.”

This study confirms findings in a 2017 study suggesting a relationship between maternal fluoride levels and children’s later cognitive scores.

Ms. Green and colleagues evaluated 512 mother-child pairs in the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) cohort from six Canadian cities. The children were born between 2008 and 2012, underwent neurodevelopmental testing between 3 and 4 years, and were assessed using the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Third Edition. Full Scale IQ (FSIQ) test.

Of these, 400 mother-child pairs had data on fluoride intake, IQ, and complete covariate data; 141 of these mothers lived in areas with fluoridated tap water, while 228 mothers lived in areas without fluoridated tap water. Maternal urinary fluoride adjusted for specific gravity (MUFSG) was averaged across three trimesters of data, and the estimated fluoride level was obtained through self-reported exposure by women included in the study.

The researchers found mothers living in areas with fluoridated water had significantly higher MUFSG levels (0.69 mg/L), compared with women in areas without fluoridated water (0.40 mg/L; P equals .001). The median estimated fluoride intake was significantly higher among women living in areas with fluoridated water (0.93 mg per day) than in women who did not live in areas with fluoridated water (0.30 mg per day; P less than .001).

Overall, children scored a mean 107.16 (range, 52-143) on the IQ test, and girls had significantly higher mean IQ scores than did boys (109.56 vs. 104.61; P = .001). After adjusting for covariates of maternal age, race, parity, smoking, and alcohol status during pregnancy, child gender, gestational age, and birth weight, the researchers found a significant interaction between MUFSG and the child’s gender (P = .02), and a 1-mg/L MUFSG increase was associated with a decrease in 4.49 IQ points in boys (95% confidence interval, −8.38 to −0.60) but not girls. There also was an association between 1-mg higher daily intake of maternal fluoride intake and decreased IQ score in both boys and girls (−3.66; 95% CI, −7.16 to −0.15 ; P = .04).

Ms. Green and her colleagues acknowledged several limitations with the study, such as the short half-life of urinary fluoride and the potential inaccuracy of maternal urinary samples at predicting fetal exposure to fluoride, the self-reported nature of estimated fluoride consumption, lack of availability of maternal IQ data, and not including postnatal exposure and consumption of fluoride.

In a related editorial, David C. Bellinger, PhD, MSc, referred to a previous prospective study in Mexico City by Bashash et al. that found a maternal fluoride level of 0.9 mg/L was associated with a decrease in cognitive scores in children at 4 years and between 6 years and 12 years (Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125(9):097017. doi: 10.1289/EHP655), and noted the effect sizes seen in the Mexico City study were similar to those reported by Green et al. “If the effect sizes reported by Green et al. and others are valid, the total cognitive loss at the population level that might be associated with children’s prenatal exposure to fluoride could be substantial,” he said.

The study raises many questions, including whether there is a concentration where neurotoxicity risk is negligible, if gender plays a role (there was no gender risk difference in Bashash et al.), whether other developmental domains are affected apart from IQ, and if postnatal exposure carries a risk, Dr. Bellinger said. “The findings of Green et al. and others indicate that a dispassionate and tempered discussion of fluoride’s potential neurotoxicity is warranted, including consideration of what additional research is needed to reach more definitive conclusions about the implications, if any, for public health,” he said.