User login

Weight-based teasing may mean further weight gain in children

according to Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and her associates.

The investigators conducted a longitudinal, observational study of 110 children who were either in the 85th body mass index (BMI) percentile or greater or had two parents with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2. Children were recruited between July 12, 1996, and July 6, 2009, administered the Perception of Teasing Scale at baseline and during follow-up, and followed for up to 15 years. Children were aged a mean of 12 years at baseline, and attended an average of nine visits.

At baseline, 53% of children were overweight, with overweight being more common in girls and in non-Hispanic whites. A total of 62% of children who were overweight at baseline reported at least one incidence of weight-based teasing (WBT), compared with 21% of children at risk. WBT at baseline was associated with BMI throughout the study (P less than .001). In addition, children who reported more WBT showed a steeper gain in BMI (P = .007). Overall, children who reported high levels of WBT had 33% greater gains in BMI per year than those with no WBT.

Fat mass was associated with WBT in a similar manner, but to an increased extent, as children who reported high levels of WBT gained 91% more fat per year than those with no WBT.

“As adolescence marks a critical period for the study of weight gain, it will be important to further explore the effects of WBT and weight‐related pressures on indices of weight and health throughout development and to identify both risk and protective factors. The present findings ... may provide a foundation upon which to initiate clinical pediatric interventions to determine whether reducing WBT affects weight and fat gain trajectory,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schvey NA et al. Pediatr Obes. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12538.

according to Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and her associates.

The investigators conducted a longitudinal, observational study of 110 children who were either in the 85th body mass index (BMI) percentile or greater or had two parents with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2. Children were recruited between July 12, 1996, and July 6, 2009, administered the Perception of Teasing Scale at baseline and during follow-up, and followed for up to 15 years. Children were aged a mean of 12 years at baseline, and attended an average of nine visits.

At baseline, 53% of children were overweight, with overweight being more common in girls and in non-Hispanic whites. A total of 62% of children who were overweight at baseline reported at least one incidence of weight-based teasing (WBT), compared with 21% of children at risk. WBT at baseline was associated with BMI throughout the study (P less than .001). In addition, children who reported more WBT showed a steeper gain in BMI (P = .007). Overall, children who reported high levels of WBT had 33% greater gains in BMI per year than those with no WBT.

Fat mass was associated with WBT in a similar manner, but to an increased extent, as children who reported high levels of WBT gained 91% more fat per year than those with no WBT.

“As adolescence marks a critical period for the study of weight gain, it will be important to further explore the effects of WBT and weight‐related pressures on indices of weight and health throughout development and to identify both risk and protective factors. The present findings ... may provide a foundation upon which to initiate clinical pediatric interventions to determine whether reducing WBT affects weight and fat gain trajectory,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schvey NA et al. Pediatr Obes. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12538.

according to Natasha A. Schvey, PhD, of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., and her associates.

The investigators conducted a longitudinal, observational study of 110 children who were either in the 85th body mass index (BMI) percentile or greater or had two parents with a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2. Children were recruited between July 12, 1996, and July 6, 2009, administered the Perception of Teasing Scale at baseline and during follow-up, and followed for up to 15 years. Children were aged a mean of 12 years at baseline, and attended an average of nine visits.

At baseline, 53% of children were overweight, with overweight being more common in girls and in non-Hispanic whites. A total of 62% of children who were overweight at baseline reported at least one incidence of weight-based teasing (WBT), compared with 21% of children at risk. WBT at baseline was associated with BMI throughout the study (P less than .001). In addition, children who reported more WBT showed a steeper gain in BMI (P = .007). Overall, children who reported high levels of WBT had 33% greater gains in BMI per year than those with no WBT.

Fat mass was associated with WBT in a similar manner, but to an increased extent, as children who reported high levels of WBT gained 91% more fat per year than those with no WBT.

“As adolescence marks a critical period for the study of weight gain, it will be important to further explore the effects of WBT and weight‐related pressures on indices of weight and health throughout development and to identify both risk and protective factors. The present findings ... may provide a foundation upon which to initiate clinical pediatric interventions to determine whether reducing WBT affects weight and fat gain trajectory,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Schvey NA et al. Pediatr Obes. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12538.

FROM PEDIATRIC OBESITY

Children’s anxiety during asthma exacerbations linked to better outcomes

BALTIMORE – according to new research.

“When kids are anxious specifically during their asthma attacks, that can be a good thing because it means that they’re more vigilant,” lead author Jonathan M. Feldman, PhD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Children’s Hospital at Montefiore and of Yeshiva University in the New York said in an interview. “They may be more likely to react during the early stages of an attack, and they may be more likely to be using self-management strategies at home and using their controller medications on a daily basis.”

He said pediatric providers can ask their patients with asthma how they feel during asthma attacks, such as whether they ever feel scared or worried.

“If a kid says no, not at all, then I would be concerned as a provider because they may not be paying attention to their asthma symptoms and they may not be taking it seriously,” Dr. Feldman said.

Past research has suggested that “illness-specific panic-fear” – the amount of anxiety someone experiences during asthma exacerbations – helps adults develop adaptive asthma management strategies, so Dr. Feldman and his colleagues examined the phenomenon as a potential protective factor in children. They shared their findings at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The research focused on Puerto Rican (n = 79) and Mexican (n = 188) children because of the substantial disparity in asthma prevalence and control between these two different Latino populations. Puerto Rican children have the highest asthma prevalence and morbidity among American children, whereas Mexican children have the lowest rates.

The 267 participants, aged 5-12 years, included 110 children from two inner-city hospitals in the New York and 157 children from two school-based health clinics and a Breathmobile in Phoenix. Nearly all the Arizona children were Mexican, and most (71%) of the Bronx children were Puerto Rican.

The authors collected the following measures at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months follow-up: spirometry (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]), Childhood Asthma Control Test (CACT) for children 5-11 years old, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) for 12-year-olds, adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and acute health care utilizations (clinic sick visits, ED visits, and hospitalizations).

The authors also queried patients on four illness-specific panic-fear measures from the Childhood Asthma Symptoms Checklist: how often they felt frightened, panicky, afraid of being alone, and afraid of dying during an asthma attack (Likert 1-5 scale).

Mexican children reported higher levels of illness-specific panic-fear at the start of the study. They also tended to have lower severity of asthma, better asthma control, and better adherence to ICS, compared with Puerto Rican children.

Also at baseline, the Mexican children’s caregivers tended to be younger, poorer, and more likely to be married and to speak Spanish. The Puerto Rican caregivers, on the other hand, had a higher educational level, including 61% high school graduates, and had more depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

One-year data revealed several links between baseline reports of panic-fear and better outcomes. Mexican children who reported experiencing panic-fear at baseline were more likely to have higher FEV1 measures at 1 year of follow-up than were those who didn’t experience panic-fear (P = .02). Similarly, Puerto Rican children initially reporting panic-fear had better asthma control at 1 year, compared with those who didn’t report panic-fear (P = .007).

The researchers reported their effect sizes in terms of predicted variance in a model that accounted for the child’s age, sex, asthma duration, asthma severity, social support, acculturation, health care provider relationship, and number of family members with asthma. The model also factored in the caregiver’s age, sex, marital status, poverty level, education, and depressive symptoms.

For example, in their model, experiencing panic-fear accounted for 67% of the variance in FEV1 levels in Mexican children and 53% of the variance in asthma control in Puerto Rican children.

Less acute health care utilization also was associated with children’s baseline levels of illness-specific panic-fear. In the model, 12% of the variance in acute health care utilization among Mexican children (P = .03) and 41% of the variance among Puerto Rican children (P = .02) was explained by child-reported panic-fear. No association was seen with medication adherence.

Although caregivers’ reports of children feeling panic-fear were linked to better FEV1 outcomes in Mexican children (P = .02), the association was only slightly significant in Puerto Rican children (P = .05). Caregiver reports of children’s panic-fear were not associated with asthma control, acute health care utilization, or medication adherence.

“Providers should be aware that anxiety focused on asthma may be beneficial and facilitate adaptive asthma management strategies,” the authors concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to new research.

“When kids are anxious specifically during their asthma attacks, that can be a good thing because it means that they’re more vigilant,” lead author Jonathan M. Feldman, PhD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Children’s Hospital at Montefiore and of Yeshiva University in the New York said in an interview. “They may be more likely to react during the early stages of an attack, and they may be more likely to be using self-management strategies at home and using their controller medications on a daily basis.”

He said pediatric providers can ask their patients with asthma how they feel during asthma attacks, such as whether they ever feel scared or worried.

“If a kid says no, not at all, then I would be concerned as a provider because they may not be paying attention to their asthma symptoms and they may not be taking it seriously,” Dr. Feldman said.

Past research has suggested that “illness-specific panic-fear” – the amount of anxiety someone experiences during asthma exacerbations – helps adults develop adaptive asthma management strategies, so Dr. Feldman and his colleagues examined the phenomenon as a potential protective factor in children. They shared their findings at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The research focused on Puerto Rican (n = 79) and Mexican (n = 188) children because of the substantial disparity in asthma prevalence and control between these two different Latino populations. Puerto Rican children have the highest asthma prevalence and morbidity among American children, whereas Mexican children have the lowest rates.

The 267 participants, aged 5-12 years, included 110 children from two inner-city hospitals in the New York and 157 children from two school-based health clinics and a Breathmobile in Phoenix. Nearly all the Arizona children were Mexican, and most (71%) of the Bronx children were Puerto Rican.

The authors collected the following measures at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months follow-up: spirometry (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]), Childhood Asthma Control Test (CACT) for children 5-11 years old, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) for 12-year-olds, adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and acute health care utilizations (clinic sick visits, ED visits, and hospitalizations).

The authors also queried patients on four illness-specific panic-fear measures from the Childhood Asthma Symptoms Checklist: how often they felt frightened, panicky, afraid of being alone, and afraid of dying during an asthma attack (Likert 1-5 scale).

Mexican children reported higher levels of illness-specific panic-fear at the start of the study. They also tended to have lower severity of asthma, better asthma control, and better adherence to ICS, compared with Puerto Rican children.

Also at baseline, the Mexican children’s caregivers tended to be younger, poorer, and more likely to be married and to speak Spanish. The Puerto Rican caregivers, on the other hand, had a higher educational level, including 61% high school graduates, and had more depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

One-year data revealed several links between baseline reports of panic-fear and better outcomes. Mexican children who reported experiencing panic-fear at baseline were more likely to have higher FEV1 measures at 1 year of follow-up than were those who didn’t experience panic-fear (P = .02). Similarly, Puerto Rican children initially reporting panic-fear had better asthma control at 1 year, compared with those who didn’t report panic-fear (P = .007).

The researchers reported their effect sizes in terms of predicted variance in a model that accounted for the child’s age, sex, asthma duration, asthma severity, social support, acculturation, health care provider relationship, and number of family members with asthma. The model also factored in the caregiver’s age, sex, marital status, poverty level, education, and depressive symptoms.

For example, in their model, experiencing panic-fear accounted for 67% of the variance in FEV1 levels in Mexican children and 53% of the variance in asthma control in Puerto Rican children.

Less acute health care utilization also was associated with children’s baseline levels of illness-specific panic-fear. In the model, 12% of the variance in acute health care utilization among Mexican children (P = .03) and 41% of the variance among Puerto Rican children (P = .02) was explained by child-reported panic-fear. No association was seen with medication adherence.

Although caregivers’ reports of children feeling panic-fear were linked to better FEV1 outcomes in Mexican children (P = .02), the association was only slightly significant in Puerto Rican children (P = .05). Caregiver reports of children’s panic-fear were not associated with asthma control, acute health care utilization, or medication adherence.

“Providers should be aware that anxiety focused on asthma may be beneficial and facilitate adaptive asthma management strategies,” the authors concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to new research.

“When kids are anxious specifically during their asthma attacks, that can be a good thing because it means that they’re more vigilant,” lead author Jonathan M. Feldman, PhD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Children’s Hospital at Montefiore and of Yeshiva University in the New York said in an interview. “They may be more likely to react during the early stages of an attack, and they may be more likely to be using self-management strategies at home and using their controller medications on a daily basis.”

He said pediatric providers can ask their patients with asthma how they feel during asthma attacks, such as whether they ever feel scared or worried.

“If a kid says no, not at all, then I would be concerned as a provider because they may not be paying attention to their asthma symptoms and they may not be taking it seriously,” Dr. Feldman said.

Past research has suggested that “illness-specific panic-fear” – the amount of anxiety someone experiences during asthma exacerbations – helps adults develop adaptive asthma management strategies, so Dr. Feldman and his colleagues examined the phenomenon as a potential protective factor in children. They shared their findings at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The research focused on Puerto Rican (n = 79) and Mexican (n = 188) children because of the substantial disparity in asthma prevalence and control between these two different Latino populations. Puerto Rican children have the highest asthma prevalence and morbidity among American children, whereas Mexican children have the lowest rates.

The 267 participants, aged 5-12 years, included 110 children from two inner-city hospitals in the New York and 157 children from two school-based health clinics and a Breathmobile in Phoenix. Nearly all the Arizona children were Mexican, and most (71%) of the Bronx children were Puerto Rican.

The authors collected the following measures at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months follow-up: spirometry (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]), Childhood Asthma Control Test (CACT) for children 5-11 years old, the Asthma Control Test (ACT) for 12-year-olds, adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and acute health care utilizations (clinic sick visits, ED visits, and hospitalizations).

The authors also queried patients on four illness-specific panic-fear measures from the Childhood Asthma Symptoms Checklist: how often they felt frightened, panicky, afraid of being alone, and afraid of dying during an asthma attack (Likert 1-5 scale).

Mexican children reported higher levels of illness-specific panic-fear at the start of the study. They also tended to have lower severity of asthma, better asthma control, and better adherence to ICS, compared with Puerto Rican children.

Also at baseline, the Mexican children’s caregivers tended to be younger, poorer, and more likely to be married and to speak Spanish. The Puerto Rican caregivers, on the other hand, had a higher educational level, including 61% high school graduates, and had more depressive symptoms on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

One-year data revealed several links between baseline reports of panic-fear and better outcomes. Mexican children who reported experiencing panic-fear at baseline were more likely to have higher FEV1 measures at 1 year of follow-up than were those who didn’t experience panic-fear (P = .02). Similarly, Puerto Rican children initially reporting panic-fear had better asthma control at 1 year, compared with those who didn’t report panic-fear (P = .007).

The researchers reported their effect sizes in terms of predicted variance in a model that accounted for the child’s age, sex, asthma duration, asthma severity, social support, acculturation, health care provider relationship, and number of family members with asthma. The model also factored in the caregiver’s age, sex, marital status, poverty level, education, and depressive symptoms.

For example, in their model, experiencing panic-fear accounted for 67% of the variance in FEV1 levels in Mexican children and 53% of the variance in asthma control in Puerto Rican children.

Less acute health care utilization also was associated with children’s baseline levels of illness-specific panic-fear. In the model, 12% of the variance in acute health care utilization among Mexican children (P = .03) and 41% of the variance among Puerto Rican children (P = .02) was explained by child-reported panic-fear. No association was seen with medication adherence.

Although caregivers’ reports of children feeling panic-fear were linked to better FEV1 outcomes in Mexican children (P = .02), the association was only slightly significant in Puerto Rican children (P = .05). Caregiver reports of children’s panic-fear were not associated with asthma control, acute health care utilization, or medication adherence.

“Providers should be aware that anxiety focused on asthma may be beneficial and facilitate adaptive asthma management strategies,” the authors concluded.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Some Brits snuff out TORCH screen to raise awareness of congenital syphilis

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Pediatricians in the south of England are so concerned about the recent national increase in the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and its ramifications for neonates that they’ve ditched the traditional TORCH newborn screen because the acronym doesn’t specifically remind clinicians to think about congenital syphilis, Mildred A. Iro, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“ explained Dr. Iro of the University of Southampton (England).

She highlighted salient features of three recent cases of congenital syphilis managed at Southampton Children’s Hospital.

“The key message that we’d like to share is that we just need to be more aware about congenital syphilis. Retest mothers if their risk factor status changes, and test suspected infants and children,” Dr. Iro said.

As a practical matter, however, even though current guidelines recommend retesting mothers whose risk factor status becomes heightened following an initial negative syphilis serology result early in pregnancy, clinicians often are unaware that a mother’s risk status has changed. And retesting all mothers during pregnancy isn’t attractive from a cost-benefit standpoint. This makes scrupulous screening of newborns all the more important. And yet TORCH, which stands for Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes infections, isn’t an acronym that promotes awareness of congenital syphilis, a disease which occupies an obscure position in TORCH under the “O” for “Other” heading. That’s why the term “congenital infection screen” has become the new norm in the south of England, she explained.

However, one pediatrician who didn’t consider congenital infection screen to be an improvement in terminology over TORCH had an alternative suggestion, which struck a favorable chord with his fellow audience members: Simply change the acronym to TORCHS, with the S standing for syphilis.

Dr. Iro noted that two of the three affected children were diagnosed at age 7-8 weeks. The third wasn’t diagnosed until age 15 months, when the mother tested positive for syphilis in a subsequent pregnancy. As is typical of the disease known as “the great masquerader,” while all three of the affected children were unwell early in infancy, they presented with a wide range of symptoms. Among the more prominent features were prolonged irritability, respiratory distress, odd rashes, anemia, hepatomegaly, and tachypnea. One infant had reduced movement and pain in one arm.

All three children underwent extensive testing. None had neurosyphilis. All achieved good outcomes on standard guideline-directed therapy.

As for the mothers, they were aged 19, 21, and 23 years when diagnosed with syphilis. All were Caucasian, and antenatal blood testing was negative in all three. None were retested during pregnancy, even though two of them had a male partner or former partner who was positive for syphilis, and the partner of the third disclosed to her that he had sex with men.

At diagnosis, all three women had a strongly positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, a high rapid plasma reagin, and a positive syphilis IgM assay.

Dr. Iro reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Pediatricians in the south of England are so concerned about the recent national increase in the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and its ramifications for neonates that they’ve ditched the traditional TORCH newborn screen because the acronym doesn’t specifically remind clinicians to think about congenital syphilis, Mildred A. Iro, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“ explained Dr. Iro of the University of Southampton (England).

She highlighted salient features of three recent cases of congenital syphilis managed at Southampton Children’s Hospital.

“The key message that we’d like to share is that we just need to be more aware about congenital syphilis. Retest mothers if their risk factor status changes, and test suspected infants and children,” Dr. Iro said.

As a practical matter, however, even though current guidelines recommend retesting mothers whose risk factor status becomes heightened following an initial negative syphilis serology result early in pregnancy, clinicians often are unaware that a mother’s risk status has changed. And retesting all mothers during pregnancy isn’t attractive from a cost-benefit standpoint. This makes scrupulous screening of newborns all the more important. And yet TORCH, which stands for Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes infections, isn’t an acronym that promotes awareness of congenital syphilis, a disease which occupies an obscure position in TORCH under the “O” for “Other” heading. That’s why the term “congenital infection screen” has become the new norm in the south of England, she explained.

However, one pediatrician who didn’t consider congenital infection screen to be an improvement in terminology over TORCH had an alternative suggestion, which struck a favorable chord with his fellow audience members: Simply change the acronym to TORCHS, with the S standing for syphilis.

Dr. Iro noted that two of the three affected children were diagnosed at age 7-8 weeks. The third wasn’t diagnosed until age 15 months, when the mother tested positive for syphilis in a subsequent pregnancy. As is typical of the disease known as “the great masquerader,” while all three of the affected children were unwell early in infancy, they presented with a wide range of symptoms. Among the more prominent features were prolonged irritability, respiratory distress, odd rashes, anemia, hepatomegaly, and tachypnea. One infant had reduced movement and pain in one arm.

All three children underwent extensive testing. None had neurosyphilis. All achieved good outcomes on standard guideline-directed therapy.

As for the mothers, they were aged 19, 21, and 23 years when diagnosed with syphilis. All were Caucasian, and antenatal blood testing was negative in all three. None were retested during pregnancy, even though two of them had a male partner or former partner who was positive for syphilis, and the partner of the third disclosed to her that he had sex with men.

At diagnosis, all three women had a strongly positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, a high rapid plasma reagin, and a positive syphilis IgM assay.

Dr. Iro reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Pediatricians in the south of England are so concerned about the recent national increase in the diagnosis of syphilis in adults and its ramifications for neonates that they’ve ditched the traditional TORCH newborn screen because the acronym doesn’t specifically remind clinicians to think about congenital syphilis, Mildred A. Iro, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“ explained Dr. Iro of the University of Southampton (England).

She highlighted salient features of three recent cases of congenital syphilis managed at Southampton Children’s Hospital.

“The key message that we’d like to share is that we just need to be more aware about congenital syphilis. Retest mothers if their risk factor status changes, and test suspected infants and children,” Dr. Iro said.

As a practical matter, however, even though current guidelines recommend retesting mothers whose risk factor status becomes heightened following an initial negative syphilis serology result early in pregnancy, clinicians often are unaware that a mother’s risk status has changed. And retesting all mothers during pregnancy isn’t attractive from a cost-benefit standpoint. This makes scrupulous screening of newborns all the more important. And yet TORCH, which stands for Toxoplasmosis, Other, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpes infections, isn’t an acronym that promotes awareness of congenital syphilis, a disease which occupies an obscure position in TORCH under the “O” for “Other” heading. That’s why the term “congenital infection screen” has become the new norm in the south of England, she explained.

However, one pediatrician who didn’t consider congenital infection screen to be an improvement in terminology over TORCH had an alternative suggestion, which struck a favorable chord with his fellow audience members: Simply change the acronym to TORCHS, with the S standing for syphilis.

Dr. Iro noted that two of the three affected children were diagnosed at age 7-8 weeks. The third wasn’t diagnosed until age 15 months, when the mother tested positive for syphilis in a subsequent pregnancy. As is typical of the disease known as “the great masquerader,” while all three of the affected children were unwell early in infancy, they presented with a wide range of symptoms. Among the more prominent features were prolonged irritability, respiratory distress, odd rashes, anemia, hepatomegaly, and tachypnea. One infant had reduced movement and pain in one arm.

All three children underwent extensive testing. None had neurosyphilis. All achieved good outcomes on standard guideline-directed therapy.

As for the mothers, they were aged 19, 21, and 23 years when diagnosed with syphilis. All were Caucasian, and antenatal blood testing was negative in all three. None were retested during pregnancy, even though two of them had a male partner or former partner who was positive for syphilis, and the partner of the third disclosed to her that he had sex with men.

At diagnosis, all three women had a strongly positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, a high rapid plasma reagin, and a positive syphilis IgM assay.

Dr. Iro reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

A longing for belonging

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

As I watched my grandson and his team warm up for their Saturday morning lacrosse game, a long parade of mostly purple-shirted adults and children of all ages began to weave its way around the periphery of the athletic field complex. A quick reading of the hand-lettered and machine-printed shirts made it clear that I was watching a charity walk for cystic fibrosis. There must have been several hundred walkers strolling by, laughing and chatting with one another. It lent a festive atmosphere to the park. I suspect that for most of the participants this was not their first fundraising event for cystic fibrosis.

The motley mix of marchers probably included several handfuls of parents of children with cystic fibrosis. I wonder how many of those parents realized how fortunate they were. Cystic fibrosis isn’t a great diagnosis. But at least it is a diagnosis, and with the diagnosis comes a community.

Reading a front-page article on DNA testing in a recent Wall Street Journal issue had primed me to reconsider how even an unfortunate diagnosis can be extremely valuable for a family (“The Unfulfilled Promise of DNA Testing,” by Amy Dockser Marcus, May 18, 2019).The focus of the article was on the confusion and disappointment that are the predictable consequences of our current inability to accurately correlate genetic code “mistakes” with phenotypic abnormalities. Of course there have been a few successes, but we aren’t even close to the promise that many have predicted in the wake of sequencing the human genome. The family featured in the article has a ridden roller coaster ride through two failed attributions of genetic syndromes that appeared to provide their now 8-year-old daughter with a diagnosis for her epilepsy and developmental delay.

In each case, the mother had searched out other families with children who shared the same genetic code errors. She formed support groups and created foundations to promote research for these rare disorders only to learn that her daughter didn’t really fit into the phenotype exhibited by the other children. As the article indicates this mother had “found a genetic home, only to feel that she no longer belonged.” She had made “intense friendships” and for “2 years, the community was her main emotional support.” Since the second diagnosis has evaporated, she has struggled with whether to remain with that community, having already left one behind. She has been encouraged to stay involved by another mother whose son does have the diagnosis. Understandably, she is still seeking the correct diagnosis, and I suspect will form or join a new community when she finds it.

We all want to belong to a community. And with that ticket comes the opportunity to share the frustrations and difficulties unique to children with that diagnosis, and the comfort that there are other people who look, behave, and feel the way we do. We hear repeatedly about the value of diversity and how wonderful it is to be all inclusive. And certainly we should continue to be as accepting as we can of people who are different. But the truth is that we will always fall short because we seem to be hardwired to notice what is different. And the power of the longing to belong is often stronger than our will to be inclusive.

The revolution that resulted in the disappearance of the label “mental retardation” and the widespread adoption of the diagnosis of autism are examples of how a community can form around a diagnosis. But not every child who is labeled as autistic will actually fit the diagnosis. Yet even a less-than-perfect attribution can provide a place where a family and a patient can feel that they belong.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Trial matches pediatric cancer patients to targeted therapies

Researchers have found they can screen pediatric cancer patients for genetic alterations and match those patients to appropriate targeted therapies.

Thus far, 24% of the patients screened have been matched and assigned to a treatment, and 10% have been enrolled on treatment protocols.

The patients were screened and matched as part of the National Cancer Institute–Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial.

Results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Donald Williams Parsons, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex., presented some results at a press briefing in advance of the meeting. “[T]he last 10 years have been an incredible time in terms of learning more about the genetics and underlying molecular basis of both adult and pediatric cancers,” Dr. Parsons said.

He pointed out, however, that it is not yet known if this information will be useful in guiding the treatment of pediatric cancers. Specifically, how many pediatric patients can be matched to targeted therapies, and how effective will those therapies be?

The Pediatric MATCH trial (NCT03155620) was developed to answer these questions. Researchers plan to enroll at least 1,000 patients in this trial. Patients are eligible if they are 1-21 years of age and have refractory or recurrent solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or histiocytic disorders.

After patients are enrolled in the trial, their tumor samples undergo DNA and RNA sequencing, and the results are used to match each patient to a targeted therapy. At present, the trial can match patients to one of 10 drugs:

- larotrectinib (targeting NTRK fusions).

- erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1/2/3/4).

- tazemetostat (targeting EZH2 or members of the SWI/SNF complex).

- LY3023414 (targeting the PI3K/MTOR pathway).

- selumetinib (targeting the MAPK pathway).

- ensartinib (targeting ALK or ROS1).

- vemurafenib (targeting BRAF V600 mutations).

- olaparib (targeting defects in DNA damage repair).

- palbociclib (targeting alterations in cell cycle genes).

- ulixertinib (targeting MAPK pathway mutations).

Early results

From July 2017 through December 2018, 422 patients were enrolled in the trial. The patients had more than 60 different diagnoses, including brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, renal and liver cancers, and other malignancies.

The researchers received tumor samples from 390 patients, attempted sequencing of 370 samples (95%), and completed sequencing of 357 samples (92%).

A treatment target was found in 112 (29%) patients, 95 (24%) of those patients were assigned to a treatment, and 39 (10%) were enrolled in a protocol. The median turnaround time from sample receipt to treatment assignment was 15 days.

“In addition to the sequencing being successful, the patients are being matched to the different treatments,” Dr. Parsons said. He added that the study is ongoing, so more of the matched and assigned patients will be enrolled in protocols in the future.

Dr. Parsons also presented results by tumor type. A targetable alteration was identified in 26% (67/255) of all non–central nervous system solid tumors, 13% (10/75) of osteosarcomas, 50% (18/36) of rhabdomyosarcomas, 21% (7/33) of Ewing sarcomas, 25% (9/36) of other sarcomas, 19% (5/26) of renal cancers, 16% (3/19) of carcinomas, 44% (8/18) of neuroblastomas, 43% (3/7) of liver cancers, and 29% (4/14) of “other” tumors.

Drilling down further, Dr. Parsons presented details on specific alterations in one cancer type: astrocytomas. Targetable alterations were found in 74% (29/39) of astrocytomas. This includes NF1 mutations (18%), BRAF V600E (15%), FGFR1 fusions/mutations (10%), BRAF fusions (10%), PIK3CA mutations (8%), NRAS/KRAS mutations (5%), and other alterations.

“Pretty remarkably, in this one diagnosis, there are patients who have been matched to nine of the ten different treatment arms,” Dr. Parsons said. “This study is allowing us to evaluate targeted therapies – specific types of investigational drugs – in patients with many different cancer types, some common, some very rare. So, hopefully, we can study these agents and identify signals of activity where some of these drugs may work for our patients.”

The Pediatric MATCH trial is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Parsons has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property related to genes discovered through sequencing of several adult cancer types.

SOURCE: Parsons DW et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 10011.

Researchers have found they can screen pediatric cancer patients for genetic alterations and match those patients to appropriate targeted therapies.

Thus far, 24% of the patients screened have been matched and assigned to a treatment, and 10% have been enrolled on treatment protocols.

The patients were screened and matched as part of the National Cancer Institute–Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial.

Results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Donald Williams Parsons, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex., presented some results at a press briefing in advance of the meeting. “[T]he last 10 years have been an incredible time in terms of learning more about the genetics and underlying molecular basis of both adult and pediatric cancers,” Dr. Parsons said.

He pointed out, however, that it is not yet known if this information will be useful in guiding the treatment of pediatric cancers. Specifically, how many pediatric patients can be matched to targeted therapies, and how effective will those therapies be?

The Pediatric MATCH trial (NCT03155620) was developed to answer these questions. Researchers plan to enroll at least 1,000 patients in this trial. Patients are eligible if they are 1-21 years of age and have refractory or recurrent solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or histiocytic disorders.

After patients are enrolled in the trial, their tumor samples undergo DNA and RNA sequencing, and the results are used to match each patient to a targeted therapy. At present, the trial can match patients to one of 10 drugs:

- larotrectinib (targeting NTRK fusions).

- erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1/2/3/4).

- tazemetostat (targeting EZH2 or members of the SWI/SNF complex).

- LY3023414 (targeting the PI3K/MTOR pathway).

- selumetinib (targeting the MAPK pathway).

- ensartinib (targeting ALK or ROS1).

- vemurafenib (targeting BRAF V600 mutations).

- olaparib (targeting defects in DNA damage repair).

- palbociclib (targeting alterations in cell cycle genes).

- ulixertinib (targeting MAPK pathway mutations).

Early results

From July 2017 through December 2018, 422 patients were enrolled in the trial. The patients had more than 60 different diagnoses, including brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, renal and liver cancers, and other malignancies.

The researchers received tumor samples from 390 patients, attempted sequencing of 370 samples (95%), and completed sequencing of 357 samples (92%).

A treatment target was found in 112 (29%) patients, 95 (24%) of those patients were assigned to a treatment, and 39 (10%) were enrolled in a protocol. The median turnaround time from sample receipt to treatment assignment was 15 days.

“In addition to the sequencing being successful, the patients are being matched to the different treatments,” Dr. Parsons said. He added that the study is ongoing, so more of the matched and assigned patients will be enrolled in protocols in the future.

Dr. Parsons also presented results by tumor type. A targetable alteration was identified in 26% (67/255) of all non–central nervous system solid tumors, 13% (10/75) of osteosarcomas, 50% (18/36) of rhabdomyosarcomas, 21% (7/33) of Ewing sarcomas, 25% (9/36) of other sarcomas, 19% (5/26) of renal cancers, 16% (3/19) of carcinomas, 44% (8/18) of neuroblastomas, 43% (3/7) of liver cancers, and 29% (4/14) of “other” tumors.

Drilling down further, Dr. Parsons presented details on specific alterations in one cancer type: astrocytomas. Targetable alterations were found in 74% (29/39) of astrocytomas. This includes NF1 mutations (18%), BRAF V600E (15%), FGFR1 fusions/mutations (10%), BRAF fusions (10%), PIK3CA mutations (8%), NRAS/KRAS mutations (5%), and other alterations.

“Pretty remarkably, in this one diagnosis, there are patients who have been matched to nine of the ten different treatment arms,” Dr. Parsons said. “This study is allowing us to evaluate targeted therapies – specific types of investigational drugs – in patients with many different cancer types, some common, some very rare. So, hopefully, we can study these agents and identify signals of activity where some of these drugs may work for our patients.”

The Pediatric MATCH trial is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Parsons has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property related to genes discovered through sequencing of several adult cancer types.

SOURCE: Parsons DW et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 10011.

Researchers have found they can screen pediatric cancer patients for genetic alterations and match those patients to appropriate targeted therapies.

Thus far, 24% of the patients screened have been matched and assigned to a treatment, and 10% have been enrolled on treatment protocols.

The patients were screened and matched as part of the National Cancer Institute–Children’s Oncology Group Pediatric MATCH (Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice) trial.

Results from this trial are scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Donald Williams Parsons, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex., presented some results at a press briefing in advance of the meeting. “[T]he last 10 years have been an incredible time in terms of learning more about the genetics and underlying molecular basis of both adult and pediatric cancers,” Dr. Parsons said.

He pointed out, however, that it is not yet known if this information will be useful in guiding the treatment of pediatric cancers. Specifically, how many pediatric patients can be matched to targeted therapies, and how effective will those therapies be?

The Pediatric MATCH trial (NCT03155620) was developed to answer these questions. Researchers plan to enroll at least 1,000 patients in this trial. Patients are eligible if they are 1-21 years of age and have refractory or recurrent solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, or histiocytic disorders.

After patients are enrolled in the trial, their tumor samples undergo DNA and RNA sequencing, and the results are used to match each patient to a targeted therapy. At present, the trial can match patients to one of 10 drugs:

- larotrectinib (targeting NTRK fusions).

- erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1/2/3/4).

- tazemetostat (targeting EZH2 or members of the SWI/SNF complex).

- LY3023414 (targeting the PI3K/MTOR pathway).

- selumetinib (targeting the MAPK pathway).

- ensartinib (targeting ALK or ROS1).

- vemurafenib (targeting BRAF V600 mutations).

- olaparib (targeting defects in DNA damage repair).

- palbociclib (targeting alterations in cell cycle genes).

- ulixertinib (targeting MAPK pathway mutations).

Early results

From July 2017 through December 2018, 422 patients were enrolled in the trial. The patients had more than 60 different diagnoses, including brain tumors, sarcomas, neuroblastoma, renal and liver cancers, and other malignancies.

The researchers received tumor samples from 390 patients, attempted sequencing of 370 samples (95%), and completed sequencing of 357 samples (92%).

A treatment target was found in 112 (29%) patients, 95 (24%) of those patients were assigned to a treatment, and 39 (10%) were enrolled in a protocol. The median turnaround time from sample receipt to treatment assignment was 15 days.

“In addition to the sequencing being successful, the patients are being matched to the different treatments,” Dr. Parsons said. He added that the study is ongoing, so more of the matched and assigned patients will be enrolled in protocols in the future.

Dr. Parsons also presented results by tumor type. A targetable alteration was identified in 26% (67/255) of all non–central nervous system solid tumors, 13% (10/75) of osteosarcomas, 50% (18/36) of rhabdomyosarcomas, 21% (7/33) of Ewing sarcomas, 25% (9/36) of other sarcomas, 19% (5/26) of renal cancers, 16% (3/19) of carcinomas, 44% (8/18) of neuroblastomas, 43% (3/7) of liver cancers, and 29% (4/14) of “other” tumors.

Drilling down further, Dr. Parsons presented details on specific alterations in one cancer type: astrocytomas. Targetable alterations were found in 74% (29/39) of astrocytomas. This includes NF1 mutations (18%), BRAF V600E (15%), FGFR1 fusions/mutations (10%), BRAF fusions (10%), PIK3CA mutations (8%), NRAS/KRAS mutations (5%), and other alterations.

“Pretty remarkably, in this one diagnosis, there are patients who have been matched to nine of the ten different treatment arms,” Dr. Parsons said. “This study is allowing us to evaluate targeted therapies – specific types of investigational drugs – in patients with many different cancer types, some common, some very rare. So, hopefully, we can study these agents and identify signals of activity where some of these drugs may work for our patients.”

The Pediatric MATCH trial is sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Parsons has patents, royalties, and other intellectual property related to genes discovered through sequencing of several adult cancer types.

SOURCE: Parsons DW et al. ASCO 2019, Abstract 10011.

REPORTING FROM ASCO 2019

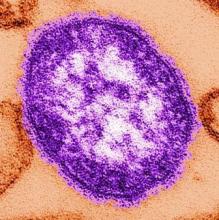

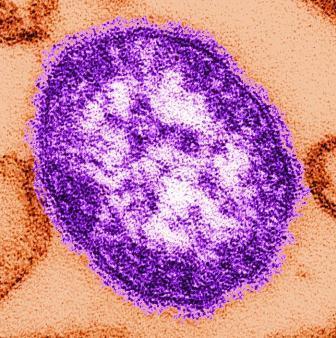

Measles cases now at highest level since 1992

With 971 cases of measles reported after just 5 months of 2019, the United States has hit another dubious milestone by surpassing the 963 cases reported in the preelimination year of 1994, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That leaves 1992, when there were 2,237 cases reported, as the next big obstacle on measles’ current path of distinction, the CDC data show. Only 312 cases were reported in 1993.

“Outbreaks in New York City and Rockland County, New York have continued for nearly 8 months. That loss would be a huge blow for the nation and erase the hard work done by all levels of public health,” the CDC said May 30.

The CDC defines measles elimination as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a specific geographic area” and notes that “measles is no longer endemic [constantly present] in the United States.”

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated. Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease that vaccination prevents,” CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

With 971 cases of measles reported after just 5 months of 2019, the United States has hit another dubious milestone by surpassing the 963 cases reported in the preelimination year of 1994, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That leaves 1992, when there were 2,237 cases reported, as the next big obstacle on measles’ current path of distinction, the CDC data show. Only 312 cases were reported in 1993.

“Outbreaks in New York City and Rockland County, New York have continued for nearly 8 months. That loss would be a huge blow for the nation and erase the hard work done by all levels of public health,” the CDC said May 30.

The CDC defines measles elimination as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a specific geographic area” and notes that “measles is no longer endemic [constantly present] in the United States.”

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated. Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease that vaccination prevents,” CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

With 971 cases of measles reported after just 5 months of 2019, the United States has hit another dubious milestone by surpassing the 963 cases reported in the preelimination year of 1994, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That leaves 1992, when there were 2,237 cases reported, as the next big obstacle on measles’ current path of distinction, the CDC data show. Only 312 cases were reported in 1993.

“Outbreaks in New York City and Rockland County, New York have continued for nearly 8 months. That loss would be a huge blow for the nation and erase the hard work done by all levels of public health,” the CDC said May 30.

The CDC defines measles elimination as “the absence of continuous disease transmission for 12 months or more in a specific geographic area” and notes that “measles is no longer endemic [constantly present] in the United States.”

“Measles is preventable and the way to end this outbreak is to ensure that all children and adults who can get vaccinated, do get vaccinated. Again, I want to reassure parents that vaccines are safe, they do not cause autism. The greater danger is the disease that vaccination prevents,” CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, said in a statement.

C-section linked to serious infection in preschoolers

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.

The association between C-section and infection-related hospitalization was persistent throughout the preschool years. For example, the increased risk associated with elective C-section was 16% during age 0-3 months, 20% during months 4-6, 14% in months 7-12, 13% during ages 1-2 years, and 11% among 2- to 5-year-olds, he continued.

The increased risk of severe preschool infection was highest for upper and lower respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections, which involve the organ systems most likely to experience direct inoculation of the maternal microbiome, he noted.

Because the investigators recognized that the study results were potentially vulnerable to confounding by indication – that is, that the reason for doing a C-section might itself confer increased risk of subsequent preschool infection-related hospitalization – they repeated their analysis in a predefined low-risk subpopulation. The results closely mirrored those in the overall study population: an 8% increased risk in the emergency C-section group and a 14% increased risk with elective C-section.

Results of this large multinational study should provide further support for ongoing research aimed at supporting the infant microbiome after delivery by C-section via vaginal microbial transfer and other methods, he observed.

Dr. Burgner reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was cosponsored by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Danish Council for Independent Research, and nonprofit foundations.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.

The association between C-section and infection-related hospitalization was persistent throughout the preschool years. For example, the increased risk associated with elective C-section was 16% during age 0-3 months, 20% during months 4-6, 14% in months 7-12, 13% during ages 1-2 years, and 11% among 2- to 5-year-olds, he continued.

The increased risk of severe preschool infection was highest for upper and lower respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections, which involve the organ systems most likely to experience direct inoculation of the maternal microbiome, he noted.

Because the investigators recognized that the study results were potentially vulnerable to confounding by indication – that is, that the reason for doing a C-section might itself confer increased risk of subsequent preschool infection-related hospitalization – they repeated their analysis in a predefined low-risk subpopulation. The results closely mirrored those in the overall study population: an 8% increased risk in the emergency C-section group and a 14% increased risk with elective C-section.

Results of this large multinational study should provide further support for ongoing research aimed at supporting the infant microbiome after delivery by C-section via vaginal microbial transfer and other methods, he observed.

Dr. Burgner reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was cosponsored by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Danish Council for Independent Research, and nonprofit foundations.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Delivery by C-section – especially when elective – carries a significantly higher hospitalization risk for severe infection in the first 5 years of life than vaginal delivery in a study of nearly 7.3 million singleton deliveries in four asset-rich countries, David Burgner, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“This is something that obstetricians might need to consider when discussing with the family the pros and cons for an elective C-section, particularly one that isn’t otherwise indicated for the baby or the mother,” said Dr. Burgner of the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Melbourne.

He presented an observational study of 7.29 million singleton births in Denmark, Great Britain, Scotland, and two Australian states during 1996-2015. C-section rates ranged from a low of 17.5% in Denmark to 29.4% in Western Australia, all of which are greater than the 10%-15% rate endorsed by the World Health Organization. Elective C-section rates varied by country from 39% to 57%. Of note, pediatric hospital care in all four countries is free, so economic considerations didn’t drive admission.

The impetus for this international collaboration was to gain new insight into the differential susceptibility to childhood infection, he explained.

“We know from our clinical practice that pretty much all of the children are exposed to pretty much all potentially serious pathogens during early life. And yet it’s only a minority that develop severe infection. It’s an extremely interesting scientific question and an extremely important clinical question as to what’s driving that differential susceptibility,” according to the pediatric infectious disease specialist.

There are a number of established risk factors for infection-related hospitalization in children, including parental smoking, maternal antibiotic exposure during pregnancy, and growth measurements at birth. Dr. Burgner and coinvestigators hypothesized that another important risk factor is the nature of the microbiome transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. This postnatal microbiome varies depending upon mode of delivery: Vaginal delivery transmits the maternal enteric microbiome, which they reasoned might be through direct immunomodulation that sets up protective immune responses early in life, especially against respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections. In contrast, delivery by C-section causes the baby to pick up the maternal skin and hospital environment microbiomes, but not the maternal enteric microbiome.

Thus, the investigators hypothesized that C-section poses a greater risk of infection-related hospitalization during the first 5 years of life than does vaginal delivery, and that elective C-section poses a higher risk than does emergency C-section because it is more likely to involve rupture of membranes.

The center-specific rates of C-section and infection-related pediatric infection, when combined into a meta-analysis, bore out the study hypothesis. Emergency C-section was associated with a 9% greater risk of infection-related hospitalization through 5 years of age than was vaginal delivery, while elective C-section was associated with a 13% increased risk, both of which were statistically significant and clinically important.

“We were quite taken with these results. We think they provide evidence that C-section is consistently associated with infection-related hospitalization. It’s an association study that can’t prove causality, but the results implicate the postnatal microbiome as the most plausible explanation in terms of what’s driving this association,” according to Dr. Burgner.

The association between C-section and infection-related hospitalization was persistent throughout the preschool years. For example, the increased risk associated with elective C-section was 16% during age 0-3 months, 20% during months 4-6, 14% in months 7-12, 13% during ages 1-2 years, and 11% among 2- to 5-year-olds, he continued.

The increased risk of severe preschool infection was highest for upper and lower respiratory tract and gastrointestinal infections, which involve the organ systems most likely to experience direct inoculation of the maternal microbiome, he noted.

Because the investigators recognized that the study results were potentially vulnerable to confounding by indication – that is, that the reason for doing a C-section might itself confer increased risk of subsequent preschool infection-related hospitalization – they repeated their analysis in a predefined low-risk subpopulation. The results closely mirrored those in the overall study population: an 8% increased risk in the emergency C-section group and a 14% increased risk with elective C-section.

Results of this large multinational study should provide further support for ongoing research aimed at supporting the infant microbiome after delivery by C-section via vaginal microbial transfer and other methods, he observed.

Dr. Burgner reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was cosponsored by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Danish Council for Independent Research, and nonprofit foundations.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

CPAP for infants with OSA is effective with high adherence

DALLAS – ), according to a study.

“Positive airway pressure is a common treatment for OSA in children,” wrote Christopher Cielo, DO, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Sleep Center, and his colleagues. But the authors note that treating infants with CPAP can be more challenging because infants have less consolidated sleep, may have greater medical complexity, and have smaller faces that make mask fit, titration, and adherence difficult.

The researchers therefore compared use of CPAP for OSA on 32 infants who began the therapy before age 6 months and 102 school-age children who began the therapy between ages 5 and 10 years, all treated at a single sleep center between March 2013 and September 2018.

Only one of the infants (mean age 3 months) had obesity, compared with 37.3% of the school-age children (mean age 7.7 years), but more of the infants (50%) had a craniofacial abnormality compared with the older children (8.9%) (P less than .001).

None of the infants had had an adenotonsillectomy, whereas the majority of the older children (80.4%) had (P less than .001). Rates of neurological abnormality and genetic syndromes (including Down syndrome) were similar between the groups.