User login

14-year-old boy • aching midsternal pain following a basketball injury • worsening pain with direct pressure and when the patient sneezed • Dx?

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

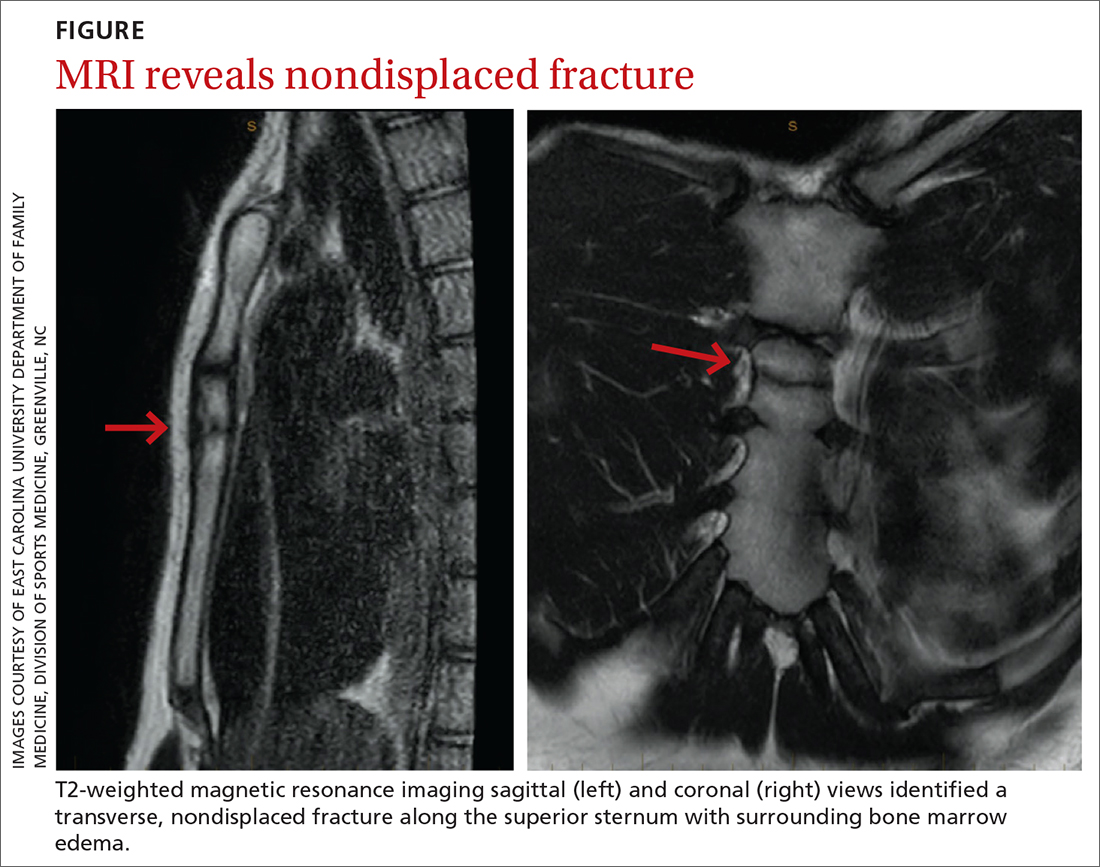

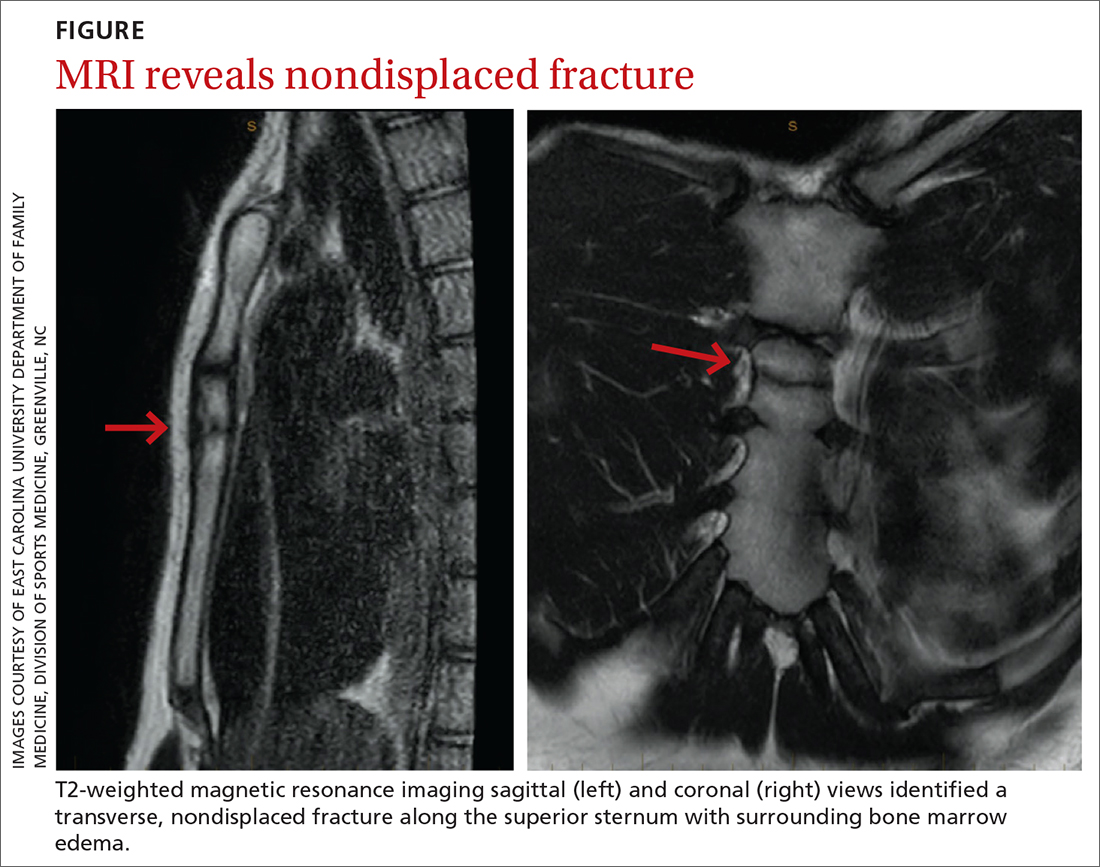

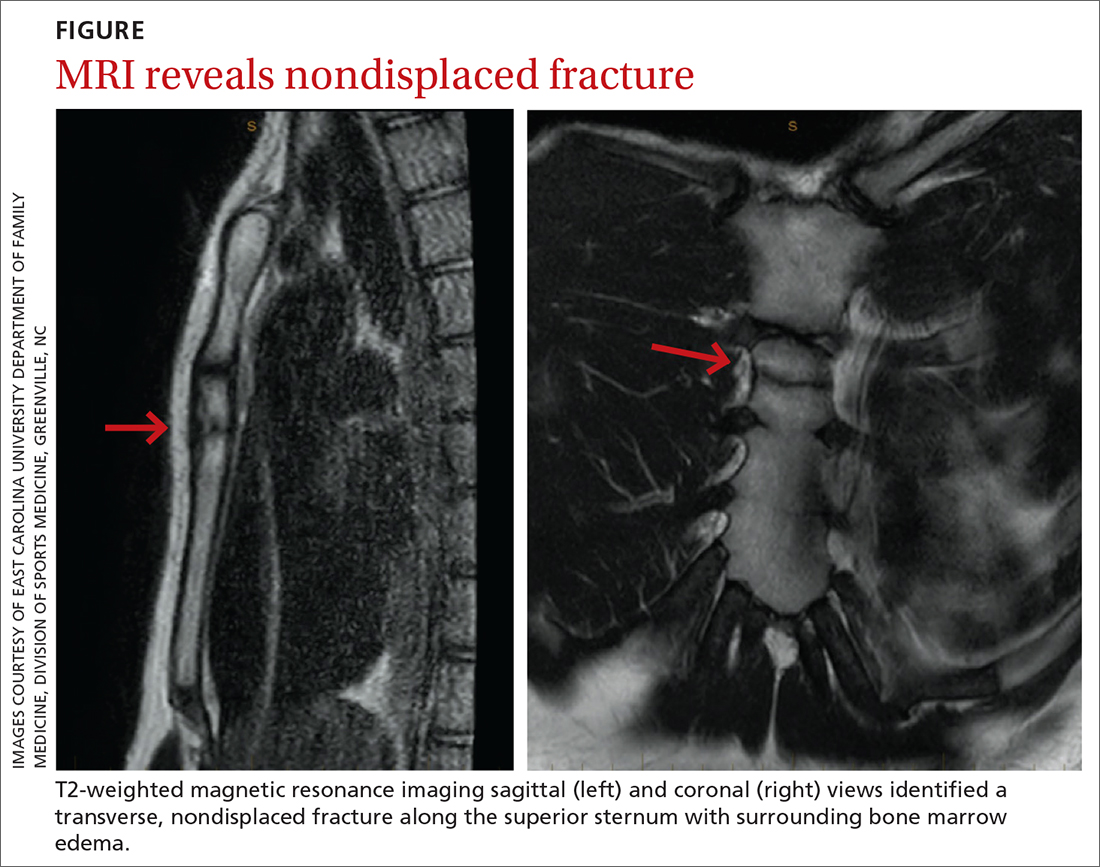

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 14-year-old boy sought care at our clinic for persistent chest pain after being hit in the chest with a teammate’s shoulder during a basketball game 3 weeks earlier. He had aching midsternal chest pain that worsened with direct pressure and when he sneezed, twisted, or bent forward. There was no bruising or swelling.

On examination, the patient demonstrated normal perfusion and normal work of breathing. He had focal tenderness with palpation at the manubrium with no noticeable step-off, and mild tenderness at the adjacent costochondral junctions and over his pectoral muscles. His sternal pain along the proximal sternum was reproducible with a weighted wall push-up. Although the patient maintained full range of motion in his upper extremities, he did have sternal pain with flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the bilateral upper extremities against resistance. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest radiographs were unremarkable.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The unremarkable chest radiographs prompted further investigation with a diagnostic ultrasound, which revealed a small cortical defect with overlying anechoic fluid collection in the area of focal tenderness. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest was performed; it revealed a transverse, nondisplaced fracture of the superior body of the sternum with surrounding bone marrow edema (FIGURE).

DISCUSSION

Fractures of the sternum comprise < 1% of traumatic fractures and have a low mortality rate (0.7%).1,2 The rarity of these fractures is attributed to the ribs’ elastic recoil, which protects the chest wall from anterior forces.1,3 These fractures are even more unusual in children due to the increased elasticity of their chest walls.4-6 Thus, it takes a significant amount of force for a child’s sternum to fracture.

While isolated sternum fractures can occur, two-thirds of sternum fractures are nonisolated and are associated with injuries to surrounding structures (including the heart, lungs, and vasculature) or fractures of the ribs and spine.2,3 Most often, these injuries are caused by significant blunt trauma to the anterior chest, rapid deceleration, or flexion-compression injury.2,3 They are typically transverse and localized, with 70% of fractures occurring in the mid-body and 17.6% at the manubriosternal joint.1,3,6

Athletes with a sternal fracture typically present as our patient did, with a history of blunt force trauma to the chest and with pain and tenderness over the anterior midline of the chest that increases with respiration or movement.1 A physical examination that includes chest palpation and auscultation of the heart and lungs must be performed to rule out damage to intrathoracic structures and assess the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary stability. An electrocardiogram should be performed to confirm that there are no cardiovascular complications.3,4

Initial imaging should include AP and lateral chest radiographs because any displacement will occur in the sagittal plane.1,2,4-6 If the radiograph shows no clear pathology, follow up with computed tomography, ultrasound, MRI, or technetium bone scans to gain additional information.1 Diagnosis of sternal fractures is especially difficult in children due to the presence of ossification centers for bone growth, which may be misinterpreted as a sternal fracture in the absence of a proper understanding of sternal development.5,6 On ultrasound, sternal fractures appear as a sharp step-off in the cortex, whereas in the absence of fracture, there is no cortical step-off and the cartilaginous plate between ossification centers appears in line with the cortex.7

Continue to: A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

A self-limiting injury that requires proper pain control

Isolated sternal fractures are typically self-limiting with a good prognosis.2 These injuries are managed supportively with rest, ice, and analgesics1; proper pain control is crucial to prevent respiratory compromise.8

Complete recovery for most patients occurs in 10 to 12 weeks.9 Recovery periods longer than 12 weeks are associated with nonisolated sternal fractures that are complicated by soft-tissue injury, injuries to the chest wall (such as sternoclavicular joint dislocation, usually from a fall on the shoulder), or fracture nonunion.1,2,5

Anterior sternoclavicular joint dislocations and stable posterior dislocations are managed with closed reduction and immobilization in a figure-of-eight brace.1 Operative management is reserved for patients with displaced fractures, sternal deformity, chest wall instability, respiratory insufficiency, uncontrolled pain, or fracture nonunion.1,3,8

A return-to-play protocol can begin once the patient is asymptomatic.1 The timeframe for a full return to play can vary from 6 weeks to 6 months, depending on the severity of the fracture.1 This process is guided by how quickly the symptoms resolve and by radiographic stability.9

Our patient was followed every 3 to 4 weeks and started physical therapy 6 weeks after his injury occurred. He was held from play for 10 weeks and gradually returned to play; he returned to full-contact activity after tolerating a practice without pain.

THE TAKEAWAY

Children typically have greater chest wall elasticity, and thus, it is unusual for them to sustain a sternal fracture. Diagnosis in children is complicated by the presence of ossification centers for bone growth on imaging. In this case, the fracture was first noticed on ultrasound and confirmed with MRI. Since these fractures can be associated with damage to surrounding structures, additional injuries should be considered when evaluating a patient with a sternum fracture.

CORRESPONDENCE

Catherine Romaine, East Carolina University, Brody School of Medicine, 600 Moye Boulevard, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected]

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

1. Alent J, Narducci DM, Moran B, et al. Sternal injuries in sport: a review of the literature. Sports Med. 2018;48:2715-2724. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0990-5

2. Khoriati A-A, Rajakulasingam R, Shah R. Sternal fractures and their management. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2013;6:113-116. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.110763

3. Athanassiadi K, Gerazounis M, Moustardas M, et al. Sternal fractures: retrospective analysis of 100 cases. World J Surg. 2002;26:1243-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6511-5

4. Ferguson LP, Wilkinson AG, Beattie TF. Fracture of the sternum in children. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:518-520. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.6.518

5. Ramgopal S, Shaffiey SA, Conti KA. Pediatric sternal fractures from a Level 1 trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:1628-1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.040

6. Sesia SB, Prüfer F, Mayr J. Sternal fracture in children: diagnosis by ultrasonography. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2017;5:e39-e42. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606197

7. Nickson C, Rippey J. Ultrasonography of sternal fractures. Australas J Ultrasound Med. 2011;14:6-11. doi: 10.1002/j.2205-0140.2011.tb00131.x

8. Bauman ZM, Yanala U, Waibel BH, et al. Sternal fixation for isolated traumatic sternal fractures improves pain and upper extremity range of motion. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48:225-230. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01568-x

9. Culp B, Hurbanek JG, Novak J, et al. Acute traumatic sternum fracture in a female college hockey player. Orthopedics. 2010;33:683. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-17

‘Sugar tax’ prevented thousands of girls becoming obese

The introduction of the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) – dubbed the ‘sugar tax’ – in England was followed by a drop in the number of older primary school girls succumbing to obesity, according to researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Bath, with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The study, published in PLOS Medicine, has led to calls to extend the levy to other unhealthy foods and drinks

Obesity has become a global public health problem, the researchers said. In England, around 10% of 4- to 5-year-old children and 20% of 10- to 11-year-olds were recorded as obese in 2020. Childhood obesity is associated with depression in children and the adults into which they maturate, as well as with serious health problems in later life including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

In the United Kingdom, young people consume significantly more added sugars than are recommended – by late adolescence, typically 70 g of added sugar per day, more than double the recommended 30g. The team said that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are the primary sources of dietary added sugars in children, with high consumption commonly observed in more deprived areas where obesity prevalence is also highest.

Protecting children from excessive sugar

The two-tier SDIL on drinks manufacturers was implemented in April 2018 and aimed to protect children from excessive sugar consumption and tackle childhood obesity by incentivizing reformulation of SSBs in the U.K. with reduced sugar content.

To assess the effects of SDIL, the researchers used data from the National Child Measurement Programme on over 1 million children at ages 4 to 5 years (reception class) and 10 to 11 years (school year 6) in state-maintained English primary schools. The surveillance program includes annual repeat cross-sectional measurements, enabling the researchers to examine trajectories in monthly prevalence of obesity from September 2013 to November 2019, 19 months after the implementation of the SDIL.

Taking account of previous trends in obesity levels, they estimated both absolute and relative changes in obesity prevalence, both overall and by sex and deprivation, and compared obesity levels after the SDIL with predicted levels had the tax not been introduced, controlling for children’s sex and the level of deprivation of their school area.

Although they found no significant association with obesity levels in reception-age children or year-6 boys, they noted an overall absolute reduction in obesity prevalence of 1.6 percentage points (PPs) (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in 10- to 11-year-old (year 6) girls. This equated to an 8% relative reduction in obesity rates compared with a counterfactual estimated from the trend prior to the SDIL announcement in March 2016, adjusted for temporal variations in obesity prevalence.

The researchers estimated that this was equivalent to preventing 5,234 cases of obesity per year in this group of year-6 girls alone.

Obesity reductions greatest in most deprived areas

Reductions were greatest in girls whose schools were in the most deprived areas, where children are known to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks. The greatest reductions in obesity were observed in the two most deprived quintiles – such that in the lowest quintile the absolute obesity prevalence reduction was 2.4 PP (95% CI, 1.6-3.2), equivalent to a 9% reduction in those living in the most deprived areas.

There are several reasons why the sugar tax did not lead to changes in levels of obesity among the younger children, the researchers said. Very young children consume fewer sugar-sweetened drinks than older children, so the soft drinks levy would have had a smaller effect. Also, fruit juices are not included in the levy, but contribute similar amounts of sugar in young children’s diets as do sugar-sweetened beverages.

Advertising may impact consumption in boys

It’s also unclear why the sugar tax might affect obesity prevalence in girls and boys differently, they said, especially since boys are higher consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages. One explanation is the possible impact of advertising – numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising than girls, both through higher levels of TV viewing and in how adverts are framed. Physical activity is often used to promote junk food and boys, compared with girls, have been shown to be more likely to believe that energy-dense junk foods depicted in adverts will boost physical performance, and so are more likely to choose energy-dense, nutrient-poor products following celebrity endorsements.

Tax ‘led to positive health impacts’

“Our findings suggest that the U.K. SDIL led to positive health impacts in the form of reduced obesity levels in girls aged 10-11 years,” the authors said. However: “Additional strategies beyond SSB taxation will be needed to reduce obesity prevalence overall, and particularly in older boys and younger children.”

Dr. Nina Rogers from the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge (England), who led the study, said: “We urgently need to find ways to tackle the increasing numbers of children living with obesity, otherwise we risk our children growing up to face significant health problems. That was one reason why the U.K.’s SDIL was introduced, and the evidence so far is promising. We’ve shown for the first time that it is likely to have helped prevent thousands of children each year becoming obese.

“It isn’t a straightforward picture, though, as it was mainly older girls who benefited. But the fact that we saw the biggest difference among girls from areas of high deprivation is important and is a step towards reducing the health inequalities they face.”

Although the researchers found an association rather than a causal link, this study adds to previous findings that the levy was associated with a substantial reduction in the amount of sugar in soft drinks.

Senior author Professor Jean Adams from the MRC Epidemiology Unit said: “We know that consuming too many sugary drinks contributes to obesity and that the U.K. soft drinks levy led to a drop in the amount of sugar in soft drinks available in the U.K., so it makes sense that we also see a drop in cases of obesity, although we only found this in girls. Children from more deprived backgrounds tend to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks, and it was among girls in this group that we saw the biggest change.”

Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, said: “The claim that the soft drink levy might have prevented 5,000 children from becoming obese is speculative because it is based on an association not actual measurements of consumption.”

He added that: “As well as continuing to discourage the consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and sweets, wider recognition should be given to foods such as biscuits [and] deep-fried foods (crisps, corn snacks, chips) that make [a] bigger contribution to excess calorie intake in children. Tackling poverty, however, is probably [the] best way to improve the diets of socially deprived children.”

Government ‘should learn from this success’

Asked to comment by this news organization, Katharine Jenner, director of the Obesity Health Alliance, said: “Government should be heartened that their soft drinks policy is already improving the health of young girls, regardless of where they live. The government should learn from this success, especially when compared with the many unsuccessful attempts to persuade industry to change their products voluntarily. They must now press ahead with policies that make it easier for everyone to eat a healthier diet, including extending the soft drinks industry levy to include other less healthy foods and drinks and measures to take junk food out of the spotlight.

“The research notes that numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising content than girls, negating the impact of the soft drinks levy [so] we need restriction on junk food marketing now, to put healthy food back in the spotlight.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research and the Medical Research Council.

A version of this article originally appeared on MedscapeUK.

The introduction of the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) – dubbed the ‘sugar tax’ – in England was followed by a drop in the number of older primary school girls succumbing to obesity, according to researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Bath, with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The study, published in PLOS Medicine, has led to calls to extend the levy to other unhealthy foods and drinks

Obesity has become a global public health problem, the researchers said. In England, around 10% of 4- to 5-year-old children and 20% of 10- to 11-year-olds were recorded as obese in 2020. Childhood obesity is associated with depression in children and the adults into which they maturate, as well as with serious health problems in later life including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

In the United Kingdom, young people consume significantly more added sugars than are recommended – by late adolescence, typically 70 g of added sugar per day, more than double the recommended 30g. The team said that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are the primary sources of dietary added sugars in children, with high consumption commonly observed in more deprived areas where obesity prevalence is also highest.

Protecting children from excessive sugar

The two-tier SDIL on drinks manufacturers was implemented in April 2018 and aimed to protect children from excessive sugar consumption and tackle childhood obesity by incentivizing reformulation of SSBs in the U.K. with reduced sugar content.

To assess the effects of SDIL, the researchers used data from the National Child Measurement Programme on over 1 million children at ages 4 to 5 years (reception class) and 10 to 11 years (school year 6) in state-maintained English primary schools. The surveillance program includes annual repeat cross-sectional measurements, enabling the researchers to examine trajectories in monthly prevalence of obesity from September 2013 to November 2019, 19 months after the implementation of the SDIL.

Taking account of previous trends in obesity levels, they estimated both absolute and relative changes in obesity prevalence, both overall and by sex and deprivation, and compared obesity levels after the SDIL with predicted levels had the tax not been introduced, controlling for children’s sex and the level of deprivation of their school area.

Although they found no significant association with obesity levels in reception-age children or year-6 boys, they noted an overall absolute reduction in obesity prevalence of 1.6 percentage points (PPs) (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in 10- to 11-year-old (year 6) girls. This equated to an 8% relative reduction in obesity rates compared with a counterfactual estimated from the trend prior to the SDIL announcement in March 2016, adjusted for temporal variations in obesity prevalence.

The researchers estimated that this was equivalent to preventing 5,234 cases of obesity per year in this group of year-6 girls alone.

Obesity reductions greatest in most deprived areas

Reductions were greatest in girls whose schools were in the most deprived areas, where children are known to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks. The greatest reductions in obesity were observed in the two most deprived quintiles – such that in the lowest quintile the absolute obesity prevalence reduction was 2.4 PP (95% CI, 1.6-3.2), equivalent to a 9% reduction in those living in the most deprived areas.

There are several reasons why the sugar tax did not lead to changes in levels of obesity among the younger children, the researchers said. Very young children consume fewer sugar-sweetened drinks than older children, so the soft drinks levy would have had a smaller effect. Also, fruit juices are not included in the levy, but contribute similar amounts of sugar in young children’s diets as do sugar-sweetened beverages.

Advertising may impact consumption in boys

It’s also unclear why the sugar tax might affect obesity prevalence in girls and boys differently, they said, especially since boys are higher consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages. One explanation is the possible impact of advertising – numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising than girls, both through higher levels of TV viewing and in how adverts are framed. Physical activity is often used to promote junk food and boys, compared with girls, have been shown to be more likely to believe that energy-dense junk foods depicted in adverts will boost physical performance, and so are more likely to choose energy-dense, nutrient-poor products following celebrity endorsements.

Tax ‘led to positive health impacts’

“Our findings suggest that the U.K. SDIL led to positive health impacts in the form of reduced obesity levels in girls aged 10-11 years,” the authors said. However: “Additional strategies beyond SSB taxation will be needed to reduce obesity prevalence overall, and particularly in older boys and younger children.”

Dr. Nina Rogers from the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge (England), who led the study, said: “We urgently need to find ways to tackle the increasing numbers of children living with obesity, otherwise we risk our children growing up to face significant health problems. That was one reason why the U.K.’s SDIL was introduced, and the evidence so far is promising. We’ve shown for the first time that it is likely to have helped prevent thousands of children each year becoming obese.

“It isn’t a straightforward picture, though, as it was mainly older girls who benefited. But the fact that we saw the biggest difference among girls from areas of high deprivation is important and is a step towards reducing the health inequalities they face.”

Although the researchers found an association rather than a causal link, this study adds to previous findings that the levy was associated with a substantial reduction in the amount of sugar in soft drinks.

Senior author Professor Jean Adams from the MRC Epidemiology Unit said: “We know that consuming too many sugary drinks contributes to obesity and that the U.K. soft drinks levy led to a drop in the amount of sugar in soft drinks available in the U.K., so it makes sense that we also see a drop in cases of obesity, although we only found this in girls. Children from more deprived backgrounds tend to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks, and it was among girls in this group that we saw the biggest change.”

Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, said: “The claim that the soft drink levy might have prevented 5,000 children from becoming obese is speculative because it is based on an association not actual measurements of consumption.”

He added that: “As well as continuing to discourage the consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and sweets, wider recognition should be given to foods such as biscuits [and] deep-fried foods (crisps, corn snacks, chips) that make [a] bigger contribution to excess calorie intake in children. Tackling poverty, however, is probably [the] best way to improve the diets of socially deprived children.”

Government ‘should learn from this success’

Asked to comment by this news organization, Katharine Jenner, director of the Obesity Health Alliance, said: “Government should be heartened that their soft drinks policy is already improving the health of young girls, regardless of where they live. The government should learn from this success, especially when compared with the many unsuccessful attempts to persuade industry to change their products voluntarily. They must now press ahead with policies that make it easier for everyone to eat a healthier diet, including extending the soft drinks industry levy to include other less healthy foods and drinks and measures to take junk food out of the spotlight.

“The research notes that numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising content than girls, negating the impact of the soft drinks levy [so] we need restriction on junk food marketing now, to put healthy food back in the spotlight.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research and the Medical Research Council.

A version of this article originally appeared on MedscapeUK.

The introduction of the soft drinks industry levy (SDIL) – dubbed the ‘sugar tax’ – in England was followed by a drop in the number of older primary school girls succumbing to obesity, according to researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford, and Bath, with colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The study, published in PLOS Medicine, has led to calls to extend the levy to other unhealthy foods and drinks

Obesity has become a global public health problem, the researchers said. In England, around 10% of 4- to 5-year-old children and 20% of 10- to 11-year-olds were recorded as obese in 2020. Childhood obesity is associated with depression in children and the adults into which they maturate, as well as with serious health problems in later life including high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

In the United Kingdom, young people consume significantly more added sugars than are recommended – by late adolescence, typically 70 g of added sugar per day, more than double the recommended 30g. The team said that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are the primary sources of dietary added sugars in children, with high consumption commonly observed in more deprived areas where obesity prevalence is also highest.

Protecting children from excessive sugar

The two-tier SDIL on drinks manufacturers was implemented in April 2018 and aimed to protect children from excessive sugar consumption and tackle childhood obesity by incentivizing reformulation of SSBs in the U.K. with reduced sugar content.

To assess the effects of SDIL, the researchers used data from the National Child Measurement Programme on over 1 million children at ages 4 to 5 years (reception class) and 10 to 11 years (school year 6) in state-maintained English primary schools. The surveillance program includes annual repeat cross-sectional measurements, enabling the researchers to examine trajectories in monthly prevalence of obesity from September 2013 to November 2019, 19 months after the implementation of the SDIL.

Taking account of previous trends in obesity levels, they estimated both absolute and relative changes in obesity prevalence, both overall and by sex and deprivation, and compared obesity levels after the SDIL with predicted levels had the tax not been introduced, controlling for children’s sex and the level of deprivation of their school area.

Although they found no significant association with obesity levels in reception-age children or year-6 boys, they noted an overall absolute reduction in obesity prevalence of 1.6 percentage points (PPs) (95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in 10- to 11-year-old (year 6) girls. This equated to an 8% relative reduction in obesity rates compared with a counterfactual estimated from the trend prior to the SDIL announcement in March 2016, adjusted for temporal variations in obesity prevalence.

The researchers estimated that this was equivalent to preventing 5,234 cases of obesity per year in this group of year-6 girls alone.

Obesity reductions greatest in most deprived areas

Reductions were greatest in girls whose schools were in the most deprived areas, where children are known to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks. The greatest reductions in obesity were observed in the two most deprived quintiles – such that in the lowest quintile the absolute obesity prevalence reduction was 2.4 PP (95% CI, 1.6-3.2), equivalent to a 9% reduction in those living in the most deprived areas.

There are several reasons why the sugar tax did not lead to changes in levels of obesity among the younger children, the researchers said. Very young children consume fewer sugar-sweetened drinks than older children, so the soft drinks levy would have had a smaller effect. Also, fruit juices are not included in the levy, but contribute similar amounts of sugar in young children’s diets as do sugar-sweetened beverages.

Advertising may impact consumption in boys

It’s also unclear why the sugar tax might affect obesity prevalence in girls and boys differently, they said, especially since boys are higher consumers of sugar-sweetened beverages. One explanation is the possible impact of advertising – numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising than girls, both through higher levels of TV viewing and in how adverts are framed. Physical activity is often used to promote junk food and boys, compared with girls, have been shown to be more likely to believe that energy-dense junk foods depicted in adverts will boost physical performance, and so are more likely to choose energy-dense, nutrient-poor products following celebrity endorsements.

Tax ‘led to positive health impacts’

“Our findings suggest that the U.K. SDIL led to positive health impacts in the form of reduced obesity levels in girls aged 10-11 years,” the authors said. However: “Additional strategies beyond SSB taxation will be needed to reduce obesity prevalence overall, and particularly in older boys and younger children.”

Dr. Nina Rogers from the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge (England), who led the study, said: “We urgently need to find ways to tackle the increasing numbers of children living with obesity, otherwise we risk our children growing up to face significant health problems. That was one reason why the U.K.’s SDIL was introduced, and the evidence so far is promising. We’ve shown for the first time that it is likely to have helped prevent thousands of children each year becoming obese.

“It isn’t a straightforward picture, though, as it was mainly older girls who benefited. But the fact that we saw the biggest difference among girls from areas of high deprivation is important and is a step towards reducing the health inequalities they face.”

Although the researchers found an association rather than a causal link, this study adds to previous findings that the levy was associated with a substantial reduction in the amount of sugar in soft drinks.

Senior author Professor Jean Adams from the MRC Epidemiology Unit said: “We know that consuming too many sugary drinks contributes to obesity and that the U.K. soft drinks levy led to a drop in the amount of sugar in soft drinks available in the U.K., so it makes sense that we also see a drop in cases of obesity, although we only found this in girls. Children from more deprived backgrounds tend to consume the largest amount of sugary drinks, and it was among girls in this group that we saw the biggest change.”

Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of nutrition and dietetics at King’s College London, said: “The claim that the soft drink levy might have prevented 5,000 children from becoming obese is speculative because it is based on an association not actual measurements of consumption.”

He added that: “As well as continuing to discourage the consumption of sugar sweetened beverages and sweets, wider recognition should be given to foods such as biscuits [and] deep-fried foods (crisps, corn snacks, chips) that make [a] bigger contribution to excess calorie intake in children. Tackling poverty, however, is probably [the] best way to improve the diets of socially deprived children.”

Government ‘should learn from this success’

Asked to comment by this news organization, Katharine Jenner, director of the Obesity Health Alliance, said: “Government should be heartened that their soft drinks policy is already improving the health of young girls, regardless of where they live. The government should learn from this success, especially when compared with the many unsuccessful attempts to persuade industry to change their products voluntarily. They must now press ahead with policies that make it easier for everyone to eat a healthier diet, including extending the soft drinks industry levy to include other less healthy foods and drinks and measures to take junk food out of the spotlight.

“The research notes that numerous studies have found that boys are often exposed to more food advertising content than girls, negating the impact of the soft drinks levy [so] we need restriction on junk food marketing now, to put healthy food back in the spotlight.”

The research was supported by the National Institute of Health and Care Research and the Medical Research Council.

A version of this article originally appeared on MedscapeUK.

Infant with red eyelid lesion

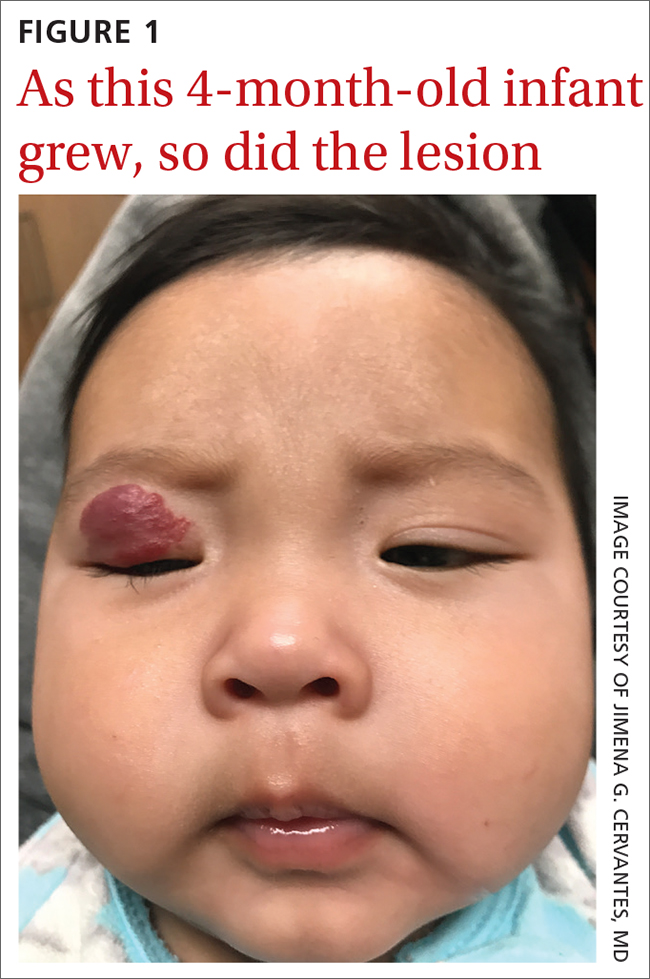

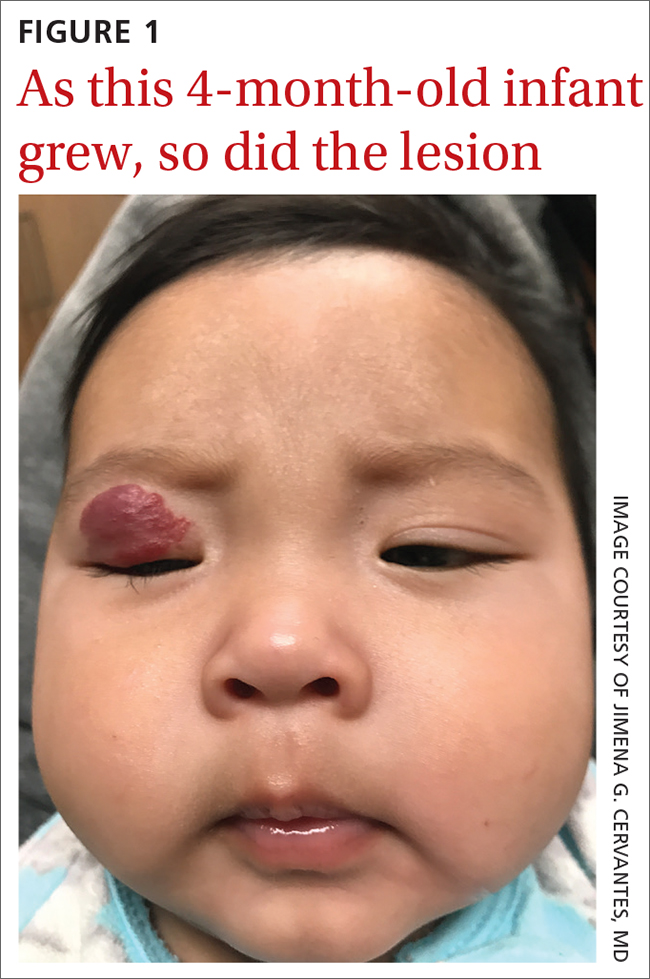

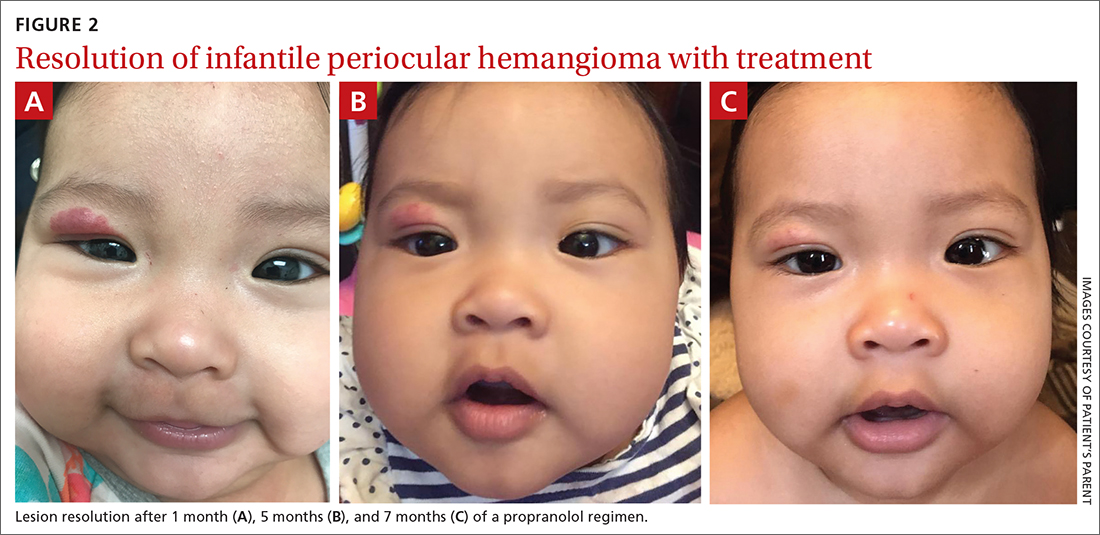

A 4-MONTH-OLD HISPANIC INFANT was brought to her pediatrician by her parents for evaluation of a dark red lesion over her right eyelid. The mother said that the lesion appeared when the child was 4 weeks old and started as a small red dot. As the baby grew, so did the red dot. The mother said the lesion appeared redder and darker when the baby got fussy and cried. The mother noted that some of the child’s eyelashes on the affected eyelid had fallen out. The infant was still able to use her eyes to follow the movements of her parents and siblings.

The mother denied any complications during pregnancy and delivered the child vaginally. No one else in the family had a similar lesion. When asked, the mother said that when her daughter was born, she was missing hair on her scalp and had dark spots on her lower backside. The mother had taken the baby to all wellness checks. The child was up to date on her vaccines, had no known drug allergies, and was otherwise healthy.

The pediatrician referred the baby to our skin clinic for further evaluation and treatment of the right eyelid lesion. Skin examination showed a 2.1-cm focal/localized, vascular, violaceous/dark red plaque over the right upper eyelid with an irregular border causing mild drooping of the right eyelid and some missing eyelashes (FIGURE 1). Multiple hyperpigmented patches on the upper and lower back were clinically consistent with Mongolian spots. Hair thinning was observed on the posterior and left posterior scalp.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infantile hemangioma

The diagnosis of an infantile hemangioma was made clinically, based on the lesion’s appearance and when it became noticeable (during the child’s first few weeks of life).

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy, and the majority are not present at birth.1,2 Infantile periocular hemangioma, which our patient had, is typically unilateral and involves the upper eyelid.1 Infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life with an area of pallor and later a faint red patch, which the mother first noted in our patient. Lesions grow rapidly in the first 3 to 6 months.2 Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or patches that may have a flat or rough surface and are sharply demarcated, while deep lesions tend to be bluish and dome shaped.1,2

Infantile hemangiomas continue to grow until 9 to 12 months of age, at which time the growth rate slows to parallel the growth of the child. Involution typically begins by the time the child is 1 year old. Most infantile hemangiomas do not improve significantly after 3.5 years of age.3

Differential includes congenital hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas

Clinical presentation, histology, and lesion evolution distinguish infantile hemangioma from other diagnoses, notably the following:

Congenital hemangiomas (CH) are fully formed vascular tumors present at birth; they occur less frequently than infantile hemangiomas. CHs are divided into 2 categories: rapidly involuting CHs and noninvoluting CHs.4

Continue to: Pyogenic granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are usually small (< 1 cm), sessile or pedunculated red papules or nodules. They are friable, bleed easily, and grow rapidly.

Capillary malformations can manifest at birth as flat, red/purple, cutaneous patches with irregular borders that are painless and can spontaneously bleed; they can be found in any part of the body but mainly occur in the cervicofacial area.5 Capillary malformations are commonly known as stork bites on the nape of the neck or angel kisses if found on the forehead. Lateral lesions, known as port wine stains, persist and do not resolve without treatment.5

Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma manifest as expanding ecchymotic firm masses with purpura and accompanying lymphedema.4 Magnetic resonance imaging, including magnetic resonance angiography, is recommended for management and treatment.4

Venous malformations can be noted at birth as a dark blue or purple discoloration and manifest as a deep mass.5 Venous malformations grow with the patient and have a rapid growth phase during puberty, pregnancy, or traumatic injury.5

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present at birth as a slight blush hypervascular lesion. AVMs can be quiescent for many years and grow with the patient. AVMs have a palpable warmth, pulse, or thrill due to high vascular flow.5

Continue to: Individualize treatment when it's needed

Individualize treatment when it’s needed

The majority of infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they can resolve spontaneously over time.2 That said, children with periocular infantile hemangiomas may require treatment because the lesions may result in amblyopia and visual impairment if not properly treated.6 Treatment should be individualized, depending on the size, rate of growth, morphology, number, and location of the lesions; existing or potential complications; benefits and adverse events associated with the treatment; age of the patient; level of parental concern; and the physician’s comfort level with the various treatment options.

Predictive factors for ocular complications in patients with periocular infantile hemangiomas are diameter > 1 cm, a deep component, and upper eyelid involvement. Patients at risk for ocular complications should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist, and treatment should be strongly considered.6 Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for high-risk and complicated infantile hemangiomas.2 This is a very safe treatment. Only rarely do the following adverse effects occur: bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, nightmares, cold hands, and hypoglycemia. If these adverse effects do occur, they are reversible with discontinuation of propranolol. Hypoglycemia can be prevented by giving propranolol during or right after feeding.

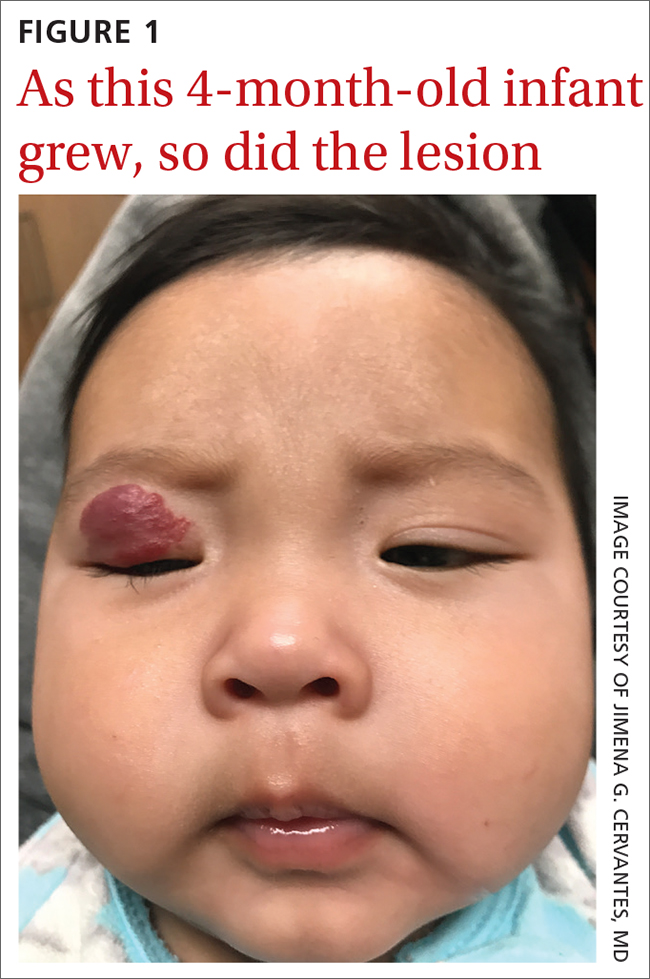

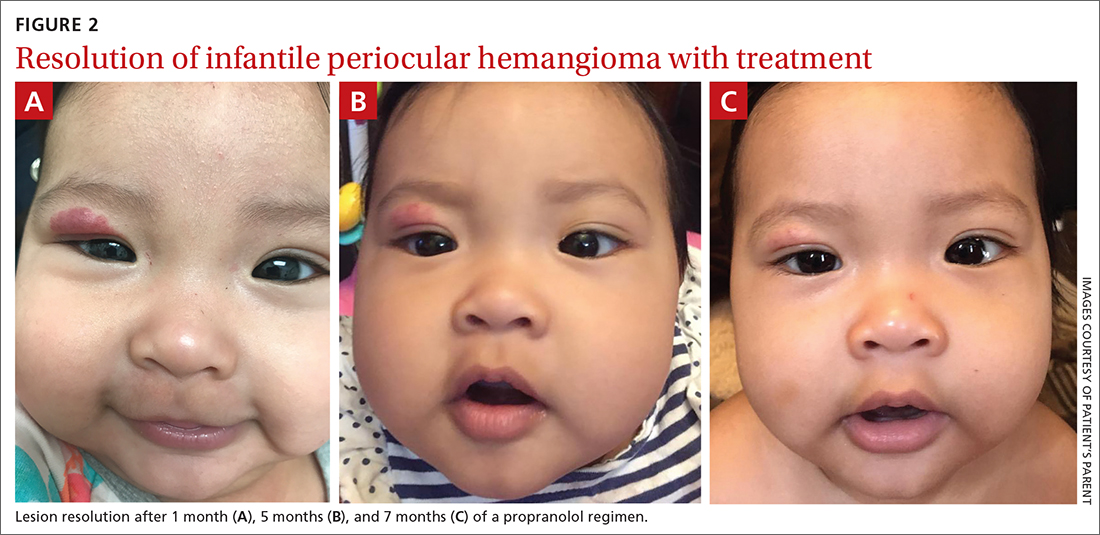

Our patient was started on propranolol 1 mg/kg/d for 1 month. The medication was administered by syringe for precise measurement. After the initial dose was tolerated, this was increased to 2 mg/kg/d for 1 month, then continued sequentially another month on 2.5 mg/kg/d, 2 months on 3 mg/kg/d, and finally 2 months on 3.4 mg/kg/d. All doses were divided twice per day between feedings.

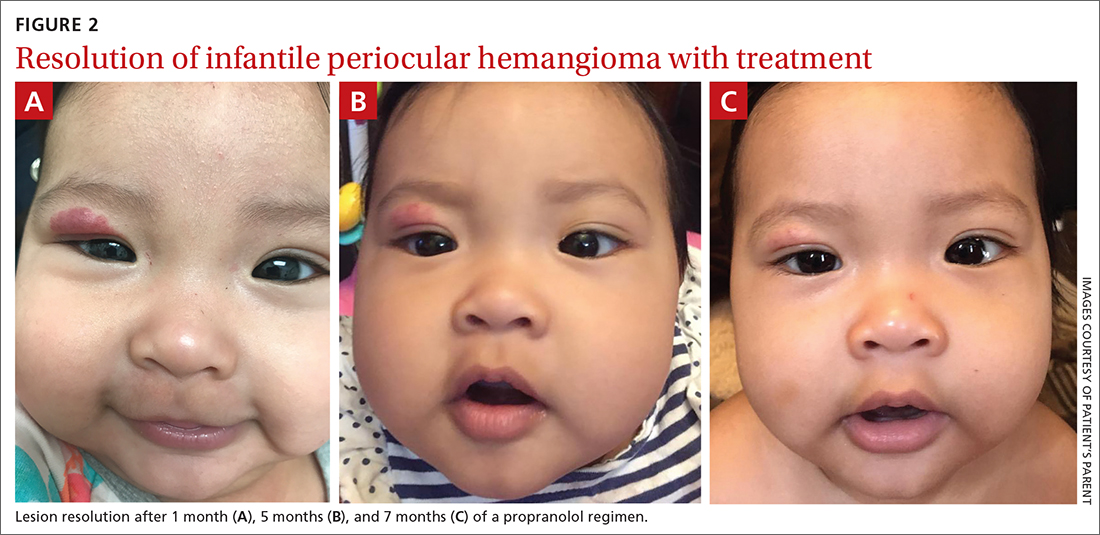

After 7 months of total treatment time (FIGURE 2), we began titrating down the patient’s dose over the next several months. After 3 months, treatment was stopped altogether. At the time treatment was completed, only a faint pink blush remained.

1. Tavakoli M, Yadegari S, Mosallaei M, et al. Infantile periocular hemangioma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:205-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_66_17

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Infantile hemangioma: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:55-69. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666200508100038

3. Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, et al. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:619-624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129

4. Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, et al. Vascular tumors in infants and adolescents. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0718-6

5. Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678

6. Samuelov L, Kinori M, Rychlik K, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications in periocular infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:458-462. doi: 10.1111/pde.13525

A 4-MONTH-OLD HISPANIC INFANT was brought to her pediatrician by her parents for evaluation of a dark red lesion over her right eyelid. The mother said that the lesion appeared when the child was 4 weeks old and started as a small red dot. As the baby grew, so did the red dot. The mother said the lesion appeared redder and darker when the baby got fussy and cried. The mother noted that some of the child’s eyelashes on the affected eyelid had fallen out. The infant was still able to use her eyes to follow the movements of her parents and siblings.

The mother denied any complications during pregnancy and delivered the child vaginally. No one else in the family had a similar lesion. When asked, the mother said that when her daughter was born, she was missing hair on her scalp and had dark spots on her lower backside. The mother had taken the baby to all wellness checks. The child was up to date on her vaccines, had no known drug allergies, and was otherwise healthy.

The pediatrician referred the baby to our skin clinic for further evaluation and treatment of the right eyelid lesion. Skin examination showed a 2.1-cm focal/localized, vascular, violaceous/dark red plaque over the right upper eyelid with an irregular border causing mild drooping of the right eyelid and some missing eyelashes (FIGURE 1). Multiple hyperpigmented patches on the upper and lower back were clinically consistent with Mongolian spots. Hair thinning was observed on the posterior and left posterior scalp.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infantile hemangioma

The diagnosis of an infantile hemangioma was made clinically, based on the lesion’s appearance and when it became noticeable (during the child’s first few weeks of life).

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy, and the majority are not present at birth.1,2 Infantile periocular hemangioma, which our patient had, is typically unilateral and involves the upper eyelid.1 Infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life with an area of pallor and later a faint red patch, which the mother first noted in our patient. Lesions grow rapidly in the first 3 to 6 months.2 Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or patches that may have a flat or rough surface and are sharply demarcated, while deep lesions tend to be bluish and dome shaped.1,2

Infantile hemangiomas continue to grow until 9 to 12 months of age, at which time the growth rate slows to parallel the growth of the child. Involution typically begins by the time the child is 1 year old. Most infantile hemangiomas do not improve significantly after 3.5 years of age.3

Differential includes congenital hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas

Clinical presentation, histology, and lesion evolution distinguish infantile hemangioma from other diagnoses, notably the following:

Congenital hemangiomas (CH) are fully formed vascular tumors present at birth; they occur less frequently than infantile hemangiomas. CHs are divided into 2 categories: rapidly involuting CHs and noninvoluting CHs.4

Continue to: Pyogenic granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are usually small (< 1 cm), sessile or pedunculated red papules or nodules. They are friable, bleed easily, and grow rapidly.

Capillary malformations can manifest at birth as flat, red/purple, cutaneous patches with irregular borders that are painless and can spontaneously bleed; they can be found in any part of the body but mainly occur in the cervicofacial area.5 Capillary malformations are commonly known as stork bites on the nape of the neck or angel kisses if found on the forehead. Lateral lesions, known as port wine stains, persist and do not resolve without treatment.5

Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma manifest as expanding ecchymotic firm masses with purpura and accompanying lymphedema.4 Magnetic resonance imaging, including magnetic resonance angiography, is recommended for management and treatment.4

Venous malformations can be noted at birth as a dark blue or purple discoloration and manifest as a deep mass.5 Venous malformations grow with the patient and have a rapid growth phase during puberty, pregnancy, or traumatic injury.5

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present at birth as a slight blush hypervascular lesion. AVMs can be quiescent for many years and grow with the patient. AVMs have a palpable warmth, pulse, or thrill due to high vascular flow.5

Continue to: Individualize treatment when it's needed

Individualize treatment when it’s needed

The majority of infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they can resolve spontaneously over time.2 That said, children with periocular infantile hemangiomas may require treatment because the lesions may result in amblyopia and visual impairment if not properly treated.6 Treatment should be individualized, depending on the size, rate of growth, morphology, number, and location of the lesions; existing or potential complications; benefits and adverse events associated with the treatment; age of the patient; level of parental concern; and the physician’s comfort level with the various treatment options.

Predictive factors for ocular complications in patients with periocular infantile hemangiomas are diameter > 1 cm, a deep component, and upper eyelid involvement. Patients at risk for ocular complications should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist, and treatment should be strongly considered.6 Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for high-risk and complicated infantile hemangiomas.2 This is a very safe treatment. Only rarely do the following adverse effects occur: bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, nightmares, cold hands, and hypoglycemia. If these adverse effects do occur, they are reversible with discontinuation of propranolol. Hypoglycemia can be prevented by giving propranolol during or right after feeding.

Our patient was started on propranolol 1 mg/kg/d for 1 month. The medication was administered by syringe for precise measurement. After the initial dose was tolerated, this was increased to 2 mg/kg/d for 1 month, then continued sequentially another month on 2.5 mg/kg/d, 2 months on 3 mg/kg/d, and finally 2 months on 3.4 mg/kg/d. All doses were divided twice per day between feedings.

After 7 months of total treatment time (FIGURE 2), we began titrating down the patient’s dose over the next several months. After 3 months, treatment was stopped altogether. At the time treatment was completed, only a faint pink blush remained.

A 4-MONTH-OLD HISPANIC INFANT was brought to her pediatrician by her parents for evaluation of a dark red lesion over her right eyelid. The mother said that the lesion appeared when the child was 4 weeks old and started as a small red dot. As the baby grew, so did the red dot. The mother said the lesion appeared redder and darker when the baby got fussy and cried. The mother noted that some of the child’s eyelashes on the affected eyelid had fallen out. The infant was still able to use her eyes to follow the movements of her parents and siblings.

The mother denied any complications during pregnancy and delivered the child vaginally. No one else in the family had a similar lesion. When asked, the mother said that when her daughter was born, she was missing hair on her scalp and had dark spots on her lower backside. The mother had taken the baby to all wellness checks. The child was up to date on her vaccines, had no known drug allergies, and was otherwise healthy.

The pediatrician referred the baby to our skin clinic for further evaluation and treatment of the right eyelid lesion. Skin examination showed a 2.1-cm focal/localized, vascular, violaceous/dark red plaque over the right upper eyelid with an irregular border causing mild drooping of the right eyelid and some missing eyelashes (FIGURE 1). Multiple hyperpigmented patches on the upper and lower back were clinically consistent with Mongolian spots. Hair thinning was observed on the posterior and left posterior scalp.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Infantile hemangioma

The diagnosis of an infantile hemangioma was made clinically, based on the lesion’s appearance and when it became noticeable (during the child’s first few weeks of life).

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy, and the majority are not present at birth.1,2 Infantile periocular hemangioma, which our patient had, is typically unilateral and involves the upper eyelid.1 Infantile hemangiomas appear in the first few weeks of life with an area of pallor and later a faint red patch, which the mother first noted in our patient. Lesions grow rapidly in the first 3 to 6 months.2 Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or patches that may have a flat or rough surface and are sharply demarcated, while deep lesions tend to be bluish and dome shaped.1,2

Infantile hemangiomas continue to grow until 9 to 12 months of age, at which time the growth rate slows to parallel the growth of the child. Involution typically begins by the time the child is 1 year old. Most infantile hemangiomas do not improve significantly after 3.5 years of age.3

Differential includes congenital hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas

Clinical presentation, histology, and lesion evolution distinguish infantile hemangioma from other diagnoses, notably the following:

Congenital hemangiomas (CH) are fully formed vascular tumors present at birth; they occur less frequently than infantile hemangiomas. CHs are divided into 2 categories: rapidly involuting CHs and noninvoluting CHs.4

Continue to: Pyogenic granulomas

Pyogenic granulomas are usually small (< 1 cm), sessile or pedunculated red papules or nodules. They are friable, bleed easily, and grow rapidly.

Capillary malformations can manifest at birth as flat, red/purple, cutaneous patches with irregular borders that are painless and can spontaneously bleed; they can be found in any part of the body but mainly occur in the cervicofacial area.5 Capillary malformations are commonly known as stork bites on the nape of the neck or angel kisses if found on the forehead. Lateral lesions, known as port wine stains, persist and do not resolve without treatment.5

Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma manifest as expanding ecchymotic firm masses with purpura and accompanying lymphedema.4 Magnetic resonance imaging, including magnetic resonance angiography, is recommended for management and treatment.4

Venous malformations can be noted at birth as a dark blue or purple discoloration and manifest as a deep mass.5 Venous malformations grow with the patient and have a rapid growth phase during puberty, pregnancy, or traumatic injury.5

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) may be present at birth as a slight blush hypervascular lesion. AVMs can be quiescent for many years and grow with the patient. AVMs have a palpable warmth, pulse, or thrill due to high vascular flow.5

Continue to: Individualize treatment when it's needed

Individualize treatment when it’s needed

The majority of infantile hemangiomas do not require treatment because they can resolve spontaneously over time.2 That said, children with periocular infantile hemangiomas may require treatment because the lesions may result in amblyopia and visual impairment if not properly treated.6 Treatment should be individualized, depending on the size, rate of growth, morphology, number, and location of the lesions; existing or potential complications; benefits and adverse events associated with the treatment; age of the patient; level of parental concern; and the physician’s comfort level with the various treatment options.

Predictive factors for ocular complications in patients with periocular infantile hemangiomas are diameter > 1 cm, a deep component, and upper eyelid involvement. Patients at risk for ocular complications should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist, and treatment should be strongly considered.6 Currently, oral propranolol is the treatment of choice for high-risk and complicated infantile hemangiomas.2 This is a very safe treatment. Only rarely do the following adverse effects occur: bronchospasm, bradycardia, hypotension, nightmares, cold hands, and hypoglycemia. If these adverse effects do occur, they are reversible with discontinuation of propranolol. Hypoglycemia can be prevented by giving propranolol during or right after feeding.

Our patient was started on propranolol 1 mg/kg/d for 1 month. The medication was administered by syringe for precise measurement. After the initial dose was tolerated, this was increased to 2 mg/kg/d for 1 month, then continued sequentially another month on 2.5 mg/kg/d, 2 months on 3 mg/kg/d, and finally 2 months on 3.4 mg/kg/d. All doses were divided twice per day between feedings.

After 7 months of total treatment time (FIGURE 2), we began titrating down the patient’s dose over the next several months. After 3 months, treatment was stopped altogether. At the time treatment was completed, only a faint pink blush remained.

1. Tavakoli M, Yadegari S, Mosallaei M, et al. Infantile periocular hemangioma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:205-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_66_17

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Infantile hemangioma: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:55-69. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666200508100038

3. Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, et al. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:619-624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129

4. Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, et al. Vascular tumors in infants and adolescents. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0718-6

5. Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678

6. Samuelov L, Kinori M, Rychlik K, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications in periocular infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:458-462. doi: 10.1111/pde.13525

1. Tavakoli M, Yadegari S, Mosallaei M, et al. Infantile periocular hemangioma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12:205-211. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_66_17

2. Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Infantile hemangioma: an updated review. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2021;17:55-69. doi: 10.2174/1573396316666200508100038

3. Couto RA, Maclellan RA, Zurakowski D, et al. Infantile hemangioma: clinical assessment of the involuting phase and implications for management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:619-624. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc129

4. Wildgruber M, Sadick M, Müller-Wille R, et al. Vascular tumors in infants and adolescents. Insights Imaging. 2019;10:30. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0718-6

5. Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations: current theory and management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678

6. Samuelov L, Kinori M, Rychlik K, et al. Risk factors for ocular complications in periocular infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:458-462. doi: 10.1111/pde.13525

Weight bias affects views of kids’ obesity recommendations

Apparently, offering children effective treatments for a chronic disease that markedly increases their risk for other chronic diseases, regularly erodes their quality of life, and is the No. 1 target of school-based bullying is wrong.

At least that’s my take watching the coverage of the recent American Academy of Pediatrics new pediatric obesity treatment guidelines that, gasp, suggest that children whose severity of obesity warrants medication or surgeries be offered medication or surgery. Because it’s wiser to not try to treat the obesity that›s contributing to a child’s type 2 diabetes, hypertension, fatty liver disease, or reduced quality of life?

The reaction isn’t surprising. Some of those who are up in arms about it have clinical or research careers dependent on championing their own favorite dietary strategies as if they are more effective and reproducible than decades of uniformly disappointing studies proving that they’re not. Others are upset because, for reasons that at times may be personal and at times may be conflicted, they believe that obesity should not be treated and/or that sustained weight loss is impossible. But overarchingly, probably the bulk of the hoopla stems from obesity being seen as a moral failing. Because the notion that those who suffer with obesity are themselves to blame has been the prevailing societal view for decades, if not centuries.

Working with families of children with obesity severe enough for them to seek help, it’s clear that if desire were sufficient to will it away, we wouldn’t need treatment guidelines let alone medications or surgery. Near uniformly, parents describe their children being bullied consequent to and being deeply self-conscious of their weight.

And what would those who think children shouldn’t be offered reproducibly effective treatment for obesity have them do about it? Many seem to think it would be preferable for kids to be placed on formal diets and, of course, that they should go out and play more. And though I’m all for encouraging the improvement of a child’s dietary quality and activity level, anyone suggesting those as panaceas for childhood obesity haven’t a clue. Not to mention the fact that, in most cases, improving overall dietary quality, something worthwhile at any weight, isn’t the dietary goal being recommended. Instead, the prescription seems to be restrictive dieting coupled with overexercising, which, unlike appropriately and thoughtfully informed and utilized medication, may increase a child’s risk of maladaptive thinking around food and fitness as well as disordered eating, not to mention challenge their self-esteem if their lifestyle results are underwhelming.

This brings us to one of the most bizarre takes on this whole business – that medications will be pushed and used when not necessary. No doubt that at times, that may occur, but the issue is that of a clinician’s overzealous prescribing and not of the treatment options or indications. Consider childhood asthma. There is no worry or uproar that children with mild asthma that isn’t having an impact on their quality of life or markedly risking their health will be placed on multiple inhaled steroids and treatments. Why? Because clinicians have been taught how to dispassionately evaluate treatment needs for asthma, monitor disease course, and not simply prescribe everything in our armamentarium.

Shocking, I know, but as is the case with every other medical condition, I think doctors are capable of learning and following an algorithm covering the indications and options for the treatment of childhood obesity.

How that looks also mirrors what’s seen with any other chronic noncommunicable disease with varied severity and impact. Doctors will evaluate each child with obesity to see whether it’s having a detrimental effect on their health or quality of life. They will monitor their patients’ obesity to see if it’s worsening and will, when necessary, undertake investigations to rule out its potential contribution to common comorbidities like type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and fatty liver disease. And, when appropriate, they will provide information on available treatment options – from lifestyle to medication to surgery and the risks, benefits, and realistic expectations associated with each – and then, without judgment, support their patients’ treatment choices because blame-free informed discussion and supportive prescription of care is, in fact, the distillation of our jobs.

If people are looking to be outraged rather than focusing their outrage on what we now need to do about childhood obesity, they should instead look to what got us here: our obesogenic environment. We and our children are swimming against a torrential current of cheap ultraprocessed calories being pushed upon us by a broken societal food culture that values convenience and simultaneously embraces the notion that knowledge is a match versus the thousands of genes and dozens of hormones that increasingly sophisticated food industry marketers and scientists prey upon. When dealing with torrential currents, we need to do more than just recommend swimming lessons.

Like asthma, which may be exacerbated by pollution in our environment both outdoors and indoors, childhood obesity is a modern-day environmentally influenced disease with varied penetrance that does not always require active treatment. Like asthma, childhood obesity is not a disease that children choose to have; it’s not a disease that can be willed away; and it’s not a disease that responds uniformly, dramatically, or enduringly to diet and exercise. Finally, literally and figuratively, like asthma, for childhood obesity, we thankfully now have a number of effective treatment options that we can offer, and it’s only our societal weight bias that leads to thinking that’s anything but great.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Apparently, offering children effective treatments for a chronic disease that markedly increases their risk for other chronic diseases, regularly erodes their quality of life, and is the No. 1 target of school-based bullying is wrong.

At least that’s my take watching the coverage of the recent American Academy of Pediatrics new pediatric obesity treatment guidelines that, gasp, suggest that children whose severity of obesity warrants medication or surgeries be offered medication or surgery. Because it’s wiser to not try to treat the obesity that›s contributing to a child’s type 2 diabetes, hypertension, fatty liver disease, or reduced quality of life?

The reaction isn’t surprising. Some of those who are up in arms about it have clinical or research careers dependent on championing their own favorite dietary strategies as if they are more effective and reproducible than decades of uniformly disappointing studies proving that they’re not. Others are upset because, for reasons that at times may be personal and at times may be conflicted, they believe that obesity should not be treated and/or that sustained weight loss is impossible. But overarchingly, probably the bulk of the hoopla stems from obesity being seen as a moral failing. Because the notion that those who suffer with obesity are themselves to blame has been the prevailing societal view for decades, if not centuries.

Working with families of children with obesity severe enough for them to seek help, it’s clear that if desire were sufficient to will it away, we wouldn’t need treatment guidelines let alone medications or surgery. Near uniformly, parents describe their children being bullied consequent to and being deeply self-conscious of their weight.