User login

Antimicrobial use varies across hospital units

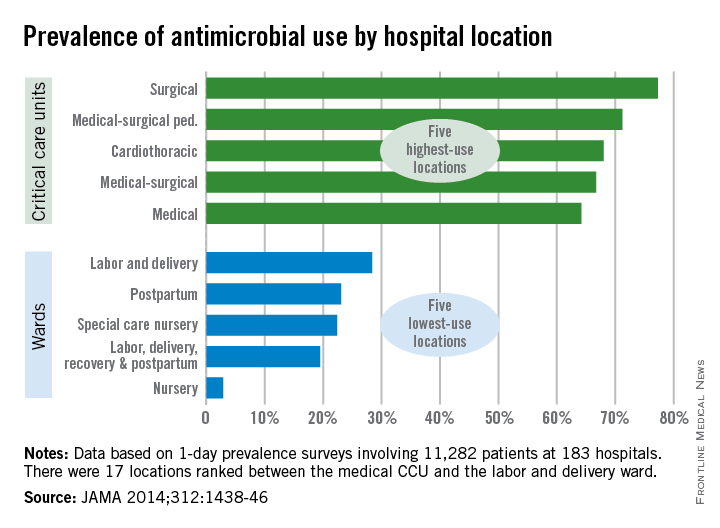

Patients in surgical critical care units were most likely to receive antimicrobial medication, while those in nursery wards were least likely to receive it, according to a recent study.

Nearly 78% of patients who used a surgical critical care unit (CCU) received antimicrobials in 2011, with 71% of patients in medical-surgical pediatric CCUs receiving antimicrobials and patients in cardiothoracic CCUs receiving antimicrobials at a 68% rate, according to Dr. Shelley S. Magill of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates (JAMA 2014;312:1438-46).

With only 3% of patients receiving antimicrobials, nursery wards had the lowest rate of medication, with labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum wards giving antimicrobials to 20% of patients and 22% of patients receiving antimicrobials in special care nurseries, they reported.

Of the 5,635 patients who received antimicrobials, 4,278 received them for the treatment of infection. Lower respiratory tract infections were the most commonly treated type of infection, with 35% of patients receiving antimicrobials. Urinary tract and skin and soft tissue infections also were commonly treated with antimicrobials at a rate of 22% and 16%, respectively.

Overall (including prophylaxis,noninfection-related reasons, and undocumented rationale), vancomycin was the most commonly received antimicrobial, followed by cefazolin and ceftriaxone, according to Dr. Magill and her associates.

The study used data collected during 1-day prevalence surveys at 183 U.S. acute care hospitals and involving 11,282 patients.

Patients in surgical critical care units were most likely to receive antimicrobial medication, while those in nursery wards were least likely to receive it, according to a recent study.

Nearly 78% of patients who used a surgical critical care unit (CCU) received antimicrobials in 2011, with 71% of patients in medical-surgical pediatric CCUs receiving antimicrobials and patients in cardiothoracic CCUs receiving antimicrobials at a 68% rate, according to Dr. Shelley S. Magill of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates (JAMA 2014;312:1438-46).

With only 3% of patients receiving antimicrobials, nursery wards had the lowest rate of medication, with labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum wards giving antimicrobials to 20% of patients and 22% of patients receiving antimicrobials in special care nurseries, they reported.

Of the 5,635 patients who received antimicrobials, 4,278 received them for the treatment of infection. Lower respiratory tract infections were the most commonly treated type of infection, with 35% of patients receiving antimicrobials. Urinary tract and skin and soft tissue infections also were commonly treated with antimicrobials at a rate of 22% and 16%, respectively.

Overall (including prophylaxis,noninfection-related reasons, and undocumented rationale), vancomycin was the most commonly received antimicrobial, followed by cefazolin and ceftriaxone, according to Dr. Magill and her associates.

The study used data collected during 1-day prevalence surveys at 183 U.S. acute care hospitals and involving 11,282 patients.

Patients in surgical critical care units were most likely to receive antimicrobial medication, while those in nursery wards were least likely to receive it, according to a recent study.

Nearly 78% of patients who used a surgical critical care unit (CCU) received antimicrobials in 2011, with 71% of patients in medical-surgical pediatric CCUs receiving antimicrobials and patients in cardiothoracic CCUs receiving antimicrobials at a 68% rate, according to Dr. Shelley S. Magill of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates (JAMA 2014;312:1438-46).

With only 3% of patients receiving antimicrobials, nursery wards had the lowest rate of medication, with labor, delivery, recovery, and postpartum wards giving antimicrobials to 20% of patients and 22% of patients receiving antimicrobials in special care nurseries, they reported.

Of the 5,635 patients who received antimicrobials, 4,278 received them for the treatment of infection. Lower respiratory tract infections were the most commonly treated type of infection, with 35% of patients receiving antimicrobials. Urinary tract and skin and soft tissue infections also were commonly treated with antimicrobials at a rate of 22% and 16%, respectively.

Overall (including prophylaxis,noninfection-related reasons, and undocumented rationale), vancomycin was the most commonly received antimicrobial, followed by cefazolin and ceftriaxone, according to Dr. Magill and her associates.

The study used data collected during 1-day prevalence surveys at 183 U.S. acute care hospitals and involving 11,282 patients.

FROM JAMA

VIDEO: Mayo Clinic app shortened hospitalizations

The Mayo Clinic handed iPads with an app called “myCare” to patients scheduled for surgery and showed that its use significantly reduced postsurgical length of stay, the total cost of care, and the need for home health care or skilled nursing care at discharge.

A study of 150 patients was so successful that the software, developed initially as an external software program for testing, is now being rebuilt into the institution’s systems so that it has a home in clinicians’ workflow, Dr. David J. Cook said at the Health 2.0 fall conference.

Dr. Cook, chair of cardiovascular anesthesiology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., describes the app in detail in this video interview. The app provides patients a customized plan of care including what they can expect daily, just-in-time education, self-assessment tools, and more. Results are transmitted wirelessly to a dashboard, where clinicians can track a patient’s progress, facilitating earlier intervention when needed.

Other investigators at the Mayo Clinic developed a separate online and smartphone-based app to help with rehabilitation of patients hospitalized after a heart attack and stent placement. The app functioned as a self-monitoring system that allowed patients to enter vital signs and to access educational content about steps they could take to reduce their risk of another heart attack.

During a 90-day study, 20% of 25 patients using the app were rehospitalized or admitted to an emergency department, compared with 60% of 19 patients in a control group who received conventional cardiac rehabilitation care without the app. The investigators reported the data at the American College of Cardiology earlier this year.

“We hope a tool like this will help us extend the reach of cardiac rehabilitation to all heart patients, but in particular, it could help patients in rural and underserved populations who might not be able to attend cardiac rehabilitation sessions,” Dr. R. Jay Widmer said in a statement released by the Mayo Clinic.

These and dozens of other apps and technological tools are being developed and tested is a systematic fashion through the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation. In the video, Dr. Cook also describes the Center’s activities and previews another innovative tool in development.

Dr. Cook reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The Mayo Clinic handed iPads with an app called “myCare” to patients scheduled for surgery and showed that its use significantly reduced postsurgical length of stay, the total cost of care, and the need for home health care or skilled nursing care at discharge.

A study of 150 patients was so successful that the software, developed initially as an external software program for testing, is now being rebuilt into the institution’s systems so that it has a home in clinicians’ workflow, Dr. David J. Cook said at the Health 2.0 fall conference.

Dr. Cook, chair of cardiovascular anesthesiology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., describes the app in detail in this video interview. The app provides patients a customized plan of care including what they can expect daily, just-in-time education, self-assessment tools, and more. Results are transmitted wirelessly to a dashboard, where clinicians can track a patient’s progress, facilitating earlier intervention when needed.

Other investigators at the Mayo Clinic developed a separate online and smartphone-based app to help with rehabilitation of patients hospitalized after a heart attack and stent placement. The app functioned as a self-monitoring system that allowed patients to enter vital signs and to access educational content about steps they could take to reduce their risk of another heart attack.

During a 90-day study, 20% of 25 patients using the app were rehospitalized or admitted to an emergency department, compared with 60% of 19 patients in a control group who received conventional cardiac rehabilitation care without the app. The investigators reported the data at the American College of Cardiology earlier this year.

“We hope a tool like this will help us extend the reach of cardiac rehabilitation to all heart patients, but in particular, it could help patients in rural and underserved populations who might not be able to attend cardiac rehabilitation sessions,” Dr. R. Jay Widmer said in a statement released by the Mayo Clinic.

These and dozens of other apps and technological tools are being developed and tested is a systematic fashion through the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation. In the video, Dr. Cook also describes the Center’s activities and previews another innovative tool in development.

Dr. Cook reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The Mayo Clinic handed iPads with an app called “myCare” to patients scheduled for surgery and showed that its use significantly reduced postsurgical length of stay, the total cost of care, and the need for home health care or skilled nursing care at discharge.

A study of 150 patients was so successful that the software, developed initially as an external software program for testing, is now being rebuilt into the institution’s systems so that it has a home in clinicians’ workflow, Dr. David J. Cook said at the Health 2.0 fall conference.

Dr. Cook, chair of cardiovascular anesthesiology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., describes the app in detail in this video interview. The app provides patients a customized plan of care including what they can expect daily, just-in-time education, self-assessment tools, and more. Results are transmitted wirelessly to a dashboard, where clinicians can track a patient’s progress, facilitating earlier intervention when needed.

Other investigators at the Mayo Clinic developed a separate online and smartphone-based app to help with rehabilitation of patients hospitalized after a heart attack and stent placement. The app functioned as a self-monitoring system that allowed patients to enter vital signs and to access educational content about steps they could take to reduce their risk of another heart attack.

During a 90-day study, 20% of 25 patients using the app were rehospitalized or admitted to an emergency department, compared with 60% of 19 patients in a control group who received conventional cardiac rehabilitation care without the app. The investigators reported the data at the American College of Cardiology earlier this year.

“We hope a tool like this will help us extend the reach of cardiac rehabilitation to all heart patients, but in particular, it could help patients in rural and underserved populations who might not be able to attend cardiac rehabilitation sessions,” Dr. R. Jay Widmer said in a statement released by the Mayo Clinic.

These and dozens of other apps and technological tools are being developed and tested is a systematic fashion through the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Innovation. In the video, Dr. Cook also describes the Center’s activities and previews another innovative tool in development.

Dr. Cook reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT HEALTH 2.0

Fenoldopam missed renal endpoint, caused hypotension in cardiac surgery patients

In its largest randomized controlled trial to date, fenoldopam did not lessen the need for dialysis after cardiac surgery and caused significantly more hypotension than did placebo, investigators reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Acute kidney injury is a common complication of cardiac surgery, and no drugs are known to effectively treat it, said Dr. Tiziana Bove of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan. “Given the cost of fenoldopam, the lack of effectiveness, and the increased incidence of hypotension, the use of this agent for renal protection in these patients is not justified,” said Dr. Bove and her associates.

The findings were published in JAMA simultaneously with the presentation at the congress ( 2014 Sept 29 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13573]).

Fenoldopam is a selective dopamine receptor D1 agonist and vasodilator. For the study, 667 patients who had developed early acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery received either an intravenous continuous infusion of fenoldopam at a starting dose of 0.1 mcg/kg per minute or placebo, the investigators said. Rates of dialysis and 30-day mortality were similar between the two groups. In all, 20% of the treatment group received renal replacement therapy, compared with 18% of the placebo group, and 30-day mortality rates were 23% and 22%, respectively, they said. Furthermore, hypotension developed in 26% of treated patients, compared with 15% of the placebo group (P = .001), the researchers said. The study was stopped for futility after an interim analysis, the researchers noted.The Italian Ministry of Health funded the study. Teva supplied the study drug. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

In its largest randomized controlled trial to date, fenoldopam did not lessen the need for dialysis after cardiac surgery and caused significantly more hypotension than did placebo, investigators reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Acute kidney injury is a common complication of cardiac surgery, and no drugs are known to effectively treat it, said Dr. Tiziana Bove of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan. “Given the cost of fenoldopam, the lack of effectiveness, and the increased incidence of hypotension, the use of this agent for renal protection in these patients is not justified,” said Dr. Bove and her associates.

The findings were published in JAMA simultaneously with the presentation at the congress ( 2014 Sept 29 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13573]).

Fenoldopam is a selective dopamine receptor D1 agonist and vasodilator. For the study, 667 patients who had developed early acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery received either an intravenous continuous infusion of fenoldopam at a starting dose of 0.1 mcg/kg per minute or placebo, the investigators said. Rates of dialysis and 30-day mortality were similar between the two groups. In all, 20% of the treatment group received renal replacement therapy, compared with 18% of the placebo group, and 30-day mortality rates were 23% and 22%, respectively, they said. Furthermore, hypotension developed in 26% of treated patients, compared with 15% of the placebo group (P = .001), the researchers said. The study was stopped for futility after an interim analysis, the researchers noted.The Italian Ministry of Health funded the study. Teva supplied the study drug. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

In its largest randomized controlled trial to date, fenoldopam did not lessen the need for dialysis after cardiac surgery and caused significantly more hypotension than did placebo, investigators reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine.

Acute kidney injury is a common complication of cardiac surgery, and no drugs are known to effectively treat it, said Dr. Tiziana Bove of IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan. “Given the cost of fenoldopam, the lack of effectiveness, and the increased incidence of hypotension, the use of this agent for renal protection in these patients is not justified,” said Dr. Bove and her associates.

The findings were published in JAMA simultaneously with the presentation at the congress ( 2014 Sept 29 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13573]).

Fenoldopam is a selective dopamine receptor D1 agonist and vasodilator. For the study, 667 patients who had developed early acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery received either an intravenous continuous infusion of fenoldopam at a starting dose of 0.1 mcg/kg per minute or placebo, the investigators said. Rates of dialysis and 30-day mortality were similar between the two groups. In all, 20% of the treatment group received renal replacement therapy, compared with 18% of the placebo group, and 30-day mortality rates were 23% and 22%, respectively, they said. Furthermore, hypotension developed in 26% of treated patients, compared with 15% of the placebo group (P = .001), the researchers said. The study was stopped for futility after an interim analysis, the researchers noted.The Italian Ministry of Health funded the study. Teva supplied the study drug. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Fenoldopam did not lessen early kidney injury after cardiac surgery and caused hypotension.

Major finding: Fenoldopam did not reduce the rate of dialysis or 30-day mortality after cardiac surgery, and 26% of treated patients developed hypotension compared with 15% of the placebo group (P = .001).

Data source: Randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial of 667 patients with early acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery.

Disclosures: The Italian Ministry of Health funded the study. Teva supplied the study drug. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Death by discontinuity of care

The story

SJ was a 66-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who was recently status post laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileoanal J pouch and diverting ileostomy 2 weeks ago at Hospital A. At the time of her surgical discharge, she was tolerating an oral diet, but over the next 2 weeks her oral intake declined, she reported feeling light-headed with movement, and she had an increase in abdominal pain despite oral analgesia. SJ was at her surgical follow-up appointment when she passed out in the waiting room. She awoke spontaneously, but she was hypotensive and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room of Hospital B. On examination SJ was very orthostatic. She had blood drawn, and she had an ECG, an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed. Her ECG and abdominal imaging were unremarkable. She was found to have an elevated lipase (910 U/dL) and low hemoglobin (9.9 mg/dL), although her anemia was not significantly different from 2 weeks ago. SJ was sent from Hospital B to Hospital C and admitted by Dr. Hospitalist 1 (nighttime, weekend coverage) for dehydration and possible pancreatitis. Dr. Hospitalist 1 initiated intravenous fluids and ordered an ultrasound of the abdomen. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were ordered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

The following morning, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 2 (daytime, weekend coverage). On examination, SJ was noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema. She remained orthostatic despite several liters of saline. Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a CT scan of the chest with a PE protocol along with ultrasonography of the legs. SJ’s morning hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL and Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a blood transfusion. The results of the imaging returned the next day and both the CT and lower extremity ultrasounds were normal. However, the abdominal ultrasound ordered by Dr. Hospitalist 1 incidentally identified an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) with a small amount of adherent clot.

The next day, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 3 (daytime, weekday attending). SJ’s hemoglobin was now 10.4 mg/dL and her lipase was normal. Dr. Hospitalist 3 documented that SJ was doing “better,” and that the plan was to wean IV fluids, work with physical therapy, and discharge soon. But SJ continued to complain of abdominal tightness, burning in her legs, and light-headedness with activity. On hospital day 4, Dr. Hospitalist 3 ordered oral antibiotics for possible leg cellulitis. On hospital day 5, SJ passed out briefly during physical therapy and Dr. Hospitalist 3 increased her IV fluids. Over the next 3 days, Dr. Hospitalist 3 stopped and restarted the IV fluids several times.

On hospital day 8, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 4 (daytime, weekend coverage). SJ remained orthostatic. Dr. Hospitalist 4 ordered a CT of the abdomen to evaluate the IVCF, which identified thrombus material within the IVCF and the entire caudal vena cava, iliac, and femoral vessels. Full-dose anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. On hospital day 10, SJ collapsed in physical therapy and lost her pulse. A full code blue response, including systemic TPA administration, failed to revive her and she was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and determined pulmonary embolism as the cause of death.

Complaint

SJ’s husband had difficulty reconciling the fact that SJ died so recently after her surgical discharge and that she had been considered “well on her way” to a full recovery. The case was referred to an attorney and subsequent review supported medical negligence and a complaint was filed. The complaint alleged that the Hospitalists (specifically 1, 2, and 3) failed to recognize SJ’s increased risk for thrombosis, failed to diagnose her IVC obstruction, and failed to initiate appropriate treatment in the form of therapeutic anticoagulation. Had the standard of care been followed, the complaint alleged, SJ would not have died.

Scientific principles

Inferior vena cava obstruction has been reported in 3%-30% of patients following IVC filter placement related to new local thrombus formation, thrombogenicity of the device, trapped embolus, or extension of a more distal DVT cephalad. Patients with inferior vena caval thrombosis (IVCT) may present with a spectrum of signs and symptoms and this variability is a significant part of the challenge of diagnosis. The classic presentation of IVCT includes bilateral lower extremity edema with dilated, visible superficial abdominal veins.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The Hospitalists defended themselves by providing reasonable alternatives to the actual diagnosis. SJ had a new ileostomy and orthostasis is common in such patients. Yet SJ did not have documented high stoma outputs and her electrolytes and renal function were inconsistent with hypovolemia.

Defense experts also pointed to SJ’s anemia and orthostasis and opined that anticoagulation would be contraindicated until hemorrhage could be ruled out. Yet SJ’s anemia was not significantly different from her surgical discharge and SJ was on anticoagulant DVT prophylaxis her entire surgical hospitalization with even lower levels of hemoglobin.

Plaintiff experts asserted that the Hospitalists should have contacted SJ’s colorectal surgeon if they were reluctant to use anticoagulants to further inform the risks and benefits. Ultimately, the defense had little explanation for the Hospitalists’ collective failure to follow-up on the abdominal ultrasound that demonstrated a small amount of adherent clot.

Conclusion

SJ was at two different hospitals and had four different Hospitalist s in 10 days.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 never saw the radiology films from Hospital B that showed an IVCF. When Dr. Hospitalist 2 began caring for SJ, he was unaware that SJ even had an IVCF or that she had a prior history of PE. Over the weekend, Dr. Hospitalist 2 did not access the labs from Hospital A to see if SJ’s anemia was new or not. Dr. Hospitalist 3 did not know that Dr. Hospitalist 1 ordered an abdominal ultrasound on admission and because the result was not flagged as “abnormal” the small adherent clot on the IVCF was not integrated into SJ’s clinical presentation.

All Hospitalist groups struggle to provide continuity in a system of discontinuity. In this case, important details were missed and it led to a delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount on behalf of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at eHospitalist news.com/Lessons.

The story

SJ was a 66-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who was recently status post laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileoanal J pouch and diverting ileostomy 2 weeks ago at Hospital A. At the time of her surgical discharge, she was tolerating an oral diet, but over the next 2 weeks her oral intake declined, she reported feeling light-headed with movement, and she had an increase in abdominal pain despite oral analgesia. SJ was at her surgical follow-up appointment when she passed out in the waiting room. She awoke spontaneously, but she was hypotensive and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room of Hospital B. On examination SJ was very orthostatic. She had blood drawn, and she had an ECG, an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed. Her ECG and abdominal imaging were unremarkable. She was found to have an elevated lipase (910 U/dL) and low hemoglobin (9.9 mg/dL), although her anemia was not significantly different from 2 weeks ago. SJ was sent from Hospital B to Hospital C and admitted by Dr. Hospitalist 1 (nighttime, weekend coverage) for dehydration and possible pancreatitis. Dr. Hospitalist 1 initiated intravenous fluids and ordered an ultrasound of the abdomen. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were ordered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

The following morning, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 2 (daytime, weekend coverage). On examination, SJ was noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema. She remained orthostatic despite several liters of saline. Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a CT scan of the chest with a PE protocol along with ultrasonography of the legs. SJ’s morning hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL and Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a blood transfusion. The results of the imaging returned the next day and both the CT and lower extremity ultrasounds were normal. However, the abdominal ultrasound ordered by Dr. Hospitalist 1 incidentally identified an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) with a small amount of adherent clot.

The next day, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 3 (daytime, weekday attending). SJ’s hemoglobin was now 10.4 mg/dL and her lipase was normal. Dr. Hospitalist 3 documented that SJ was doing “better,” and that the plan was to wean IV fluids, work with physical therapy, and discharge soon. But SJ continued to complain of abdominal tightness, burning in her legs, and light-headedness with activity. On hospital day 4, Dr. Hospitalist 3 ordered oral antibiotics for possible leg cellulitis. On hospital day 5, SJ passed out briefly during physical therapy and Dr. Hospitalist 3 increased her IV fluids. Over the next 3 days, Dr. Hospitalist 3 stopped and restarted the IV fluids several times.

On hospital day 8, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 4 (daytime, weekend coverage). SJ remained orthostatic. Dr. Hospitalist 4 ordered a CT of the abdomen to evaluate the IVCF, which identified thrombus material within the IVCF and the entire caudal vena cava, iliac, and femoral vessels. Full-dose anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. On hospital day 10, SJ collapsed in physical therapy and lost her pulse. A full code blue response, including systemic TPA administration, failed to revive her and she was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and determined pulmonary embolism as the cause of death.

Complaint

SJ’s husband had difficulty reconciling the fact that SJ died so recently after her surgical discharge and that she had been considered “well on her way” to a full recovery. The case was referred to an attorney and subsequent review supported medical negligence and a complaint was filed. The complaint alleged that the Hospitalists (specifically 1, 2, and 3) failed to recognize SJ’s increased risk for thrombosis, failed to diagnose her IVC obstruction, and failed to initiate appropriate treatment in the form of therapeutic anticoagulation. Had the standard of care been followed, the complaint alleged, SJ would not have died.

Scientific principles

Inferior vena cava obstruction has been reported in 3%-30% of patients following IVC filter placement related to new local thrombus formation, thrombogenicity of the device, trapped embolus, or extension of a more distal DVT cephalad. Patients with inferior vena caval thrombosis (IVCT) may present with a spectrum of signs and symptoms and this variability is a significant part of the challenge of diagnosis. The classic presentation of IVCT includes bilateral lower extremity edema with dilated, visible superficial abdominal veins.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The Hospitalists defended themselves by providing reasonable alternatives to the actual diagnosis. SJ had a new ileostomy and orthostasis is common in such patients. Yet SJ did not have documented high stoma outputs and her electrolytes and renal function were inconsistent with hypovolemia.

Defense experts also pointed to SJ’s anemia and orthostasis and opined that anticoagulation would be contraindicated until hemorrhage could be ruled out. Yet SJ’s anemia was not significantly different from her surgical discharge and SJ was on anticoagulant DVT prophylaxis her entire surgical hospitalization with even lower levels of hemoglobin.

Plaintiff experts asserted that the Hospitalists should have contacted SJ’s colorectal surgeon if they were reluctant to use anticoagulants to further inform the risks and benefits. Ultimately, the defense had little explanation for the Hospitalists’ collective failure to follow-up on the abdominal ultrasound that demonstrated a small amount of adherent clot.

Conclusion

SJ was at two different hospitals and had four different Hospitalist s in 10 days.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 never saw the radiology films from Hospital B that showed an IVCF. When Dr. Hospitalist 2 began caring for SJ, he was unaware that SJ even had an IVCF or that she had a prior history of PE. Over the weekend, Dr. Hospitalist 2 did not access the labs from Hospital A to see if SJ’s anemia was new or not. Dr. Hospitalist 3 did not know that Dr. Hospitalist 1 ordered an abdominal ultrasound on admission and because the result was not flagged as “abnormal” the small adherent clot on the IVCF was not integrated into SJ’s clinical presentation.

All Hospitalist groups struggle to provide continuity in a system of discontinuity. In this case, important details were missed and it led to a delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount on behalf of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at eHospitalist news.com/Lessons.

The story

SJ was a 66-year-old woman with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who was recently status post laparoscopic proctocolectomy with ileoanal J pouch and diverting ileostomy 2 weeks ago at Hospital A. At the time of her surgical discharge, she was tolerating an oral diet, but over the next 2 weeks her oral intake declined, she reported feeling light-headed with movement, and she had an increase in abdominal pain despite oral analgesia. SJ was at her surgical follow-up appointment when she passed out in the waiting room. She awoke spontaneously, but she was hypotensive and was taken by ambulance to the emergency room of Hospital B. On examination SJ was very orthostatic. She had blood drawn, and she had an ECG, an abdominal radiograph, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed. Her ECG and abdominal imaging were unremarkable. She was found to have an elevated lipase (910 U/dL) and low hemoglobin (9.9 mg/dL), although her anemia was not significantly different from 2 weeks ago. SJ was sent from Hospital B to Hospital C and admitted by Dr. Hospitalist 1 (nighttime, weekend coverage) for dehydration and possible pancreatitis. Dr. Hospitalist 1 initiated intravenous fluids and ordered an ultrasound of the abdomen. Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were ordered for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis.

The following morning, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 2 (daytime, weekend coverage). On examination, SJ was noted to have bilateral lower extremity edema. She remained orthostatic despite several liters of saline. Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a CT scan of the chest with a PE protocol along with ultrasonography of the legs. SJ’s morning hemoglobin was 8.4 mg/dL and Dr. Hospitalist 2 ordered a blood transfusion. The results of the imaging returned the next day and both the CT and lower extremity ultrasounds were normal. However, the abdominal ultrasound ordered by Dr. Hospitalist 1 incidentally identified an inferior vena cava filter (IVCF) with a small amount of adherent clot.

The next day, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 3 (daytime, weekday attending). SJ’s hemoglobin was now 10.4 mg/dL and her lipase was normal. Dr. Hospitalist 3 documented that SJ was doing “better,” and that the plan was to wean IV fluids, work with physical therapy, and discharge soon. But SJ continued to complain of abdominal tightness, burning in her legs, and light-headedness with activity. On hospital day 4, Dr. Hospitalist 3 ordered oral antibiotics for possible leg cellulitis. On hospital day 5, SJ passed out briefly during physical therapy and Dr. Hospitalist 3 increased her IV fluids. Over the next 3 days, Dr. Hospitalist 3 stopped and restarted the IV fluids several times.

On hospital day 8, SJ was seen by Dr. Hospitalist 4 (daytime, weekend coverage). SJ remained orthostatic. Dr. Hospitalist 4 ordered a CT of the abdomen to evaluate the IVCF, which identified thrombus material within the IVCF and the entire caudal vena cava, iliac, and femoral vessels. Full-dose anticoagulation was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin. On hospital day 10, SJ collapsed in physical therapy and lost her pulse. A full code blue response, including systemic TPA administration, failed to revive her and she was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and determined pulmonary embolism as the cause of death.

Complaint

SJ’s husband had difficulty reconciling the fact that SJ died so recently after her surgical discharge and that she had been considered “well on her way” to a full recovery. The case was referred to an attorney and subsequent review supported medical negligence and a complaint was filed. The complaint alleged that the Hospitalists (specifically 1, 2, and 3) failed to recognize SJ’s increased risk for thrombosis, failed to diagnose her IVC obstruction, and failed to initiate appropriate treatment in the form of therapeutic anticoagulation. Had the standard of care been followed, the complaint alleged, SJ would not have died.

Scientific principles

Inferior vena cava obstruction has been reported in 3%-30% of patients following IVC filter placement related to new local thrombus formation, thrombogenicity of the device, trapped embolus, or extension of a more distal DVT cephalad. Patients with inferior vena caval thrombosis (IVCT) may present with a spectrum of signs and symptoms and this variability is a significant part of the challenge of diagnosis. The classic presentation of IVCT includes bilateral lower extremity edema with dilated, visible superficial abdominal veins.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The Hospitalists defended themselves by providing reasonable alternatives to the actual diagnosis. SJ had a new ileostomy and orthostasis is common in such patients. Yet SJ did not have documented high stoma outputs and her electrolytes and renal function were inconsistent with hypovolemia.

Defense experts also pointed to SJ’s anemia and orthostasis and opined that anticoagulation would be contraindicated until hemorrhage could be ruled out. Yet SJ’s anemia was not significantly different from her surgical discharge and SJ was on anticoagulant DVT prophylaxis her entire surgical hospitalization with even lower levels of hemoglobin.

Plaintiff experts asserted that the Hospitalists should have contacted SJ’s colorectal surgeon if they were reluctant to use anticoagulants to further inform the risks and benefits. Ultimately, the defense had little explanation for the Hospitalists’ collective failure to follow-up on the abdominal ultrasound that demonstrated a small amount of adherent clot.

Conclusion

SJ was at two different hospitals and had four different Hospitalist s in 10 days.

Dr. Hospitalist 1 never saw the radiology films from Hospital B that showed an IVCF. When Dr. Hospitalist 2 began caring for SJ, he was unaware that SJ even had an IVCF or that she had a prior history of PE. Over the weekend, Dr. Hospitalist 2 did not access the labs from Hospital A to see if SJ’s anemia was new or not. Dr. Hospitalist 3 did not know that Dr. Hospitalist 1 ordered an abdominal ultrasound on admission and because the result was not flagged as “abnormal” the small adherent clot on the IVCF was not integrated into SJ’s clinical presentation.

All Hospitalist groups struggle to provide continuity in a system of discontinuity. In this case, important details were missed and it led to a delay in diagnosis and ultimately treatment.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount on behalf of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read past columns at eHospitalist news.com/Lessons.

Postoperative complications increase risk of death in CRC patients

Patients who develop infectious complications after undergoing curative surgery for colorectal cancer face a significantly increased risk of death, results from a large retrospective study showed.

“The association of postoperative complications with long-term survival after major surgery has been suggested by several studies in mixed populations and is to some degree expected and intuitive,” authors led by Dr. Avo Artinyan, of the surgery department at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wrote online Sept. 1 in Annals of Surgery. “It has been difficult, however, to determine a specific cause-effect relationship, particularly because this association is noted even in patients who suffer late mortality, that is, those who presumably recover from postoperative complications.”

In an effort to investigate the effect of postoperative complications on long-term survival after colorectal cancer resection, the researchers evaluated the records of 12,075 patients from the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Central Cancer Registry databases who underwent resection for nonmetastatic colorectal cancer from 1999 to 2009 (Ann. Surg. 2014 Sept. 1 [doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000854]). They categorized patients by presence of any complication within 30 days and by type of complication (infectious vs. noninfectious); excluded patients who died within 90 days of the procedure; and performed univariate and multivariate analyses adjusted for patient, disease, and treatment factors.

The average age of the cohort was 69 years, 98% were men, more than two-thirds (69%) had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification score of 3, and 61% had stage 1 or 2 disease. Dr. Artinyan and his associates found that the overall morbidity and infectious complication rates were 27.8% and 22.5%, respectively.

Compared with patients who had no postoperative complications, those who did were older and had lower postoperative serum albumin, worse functional status, and higher ASA scores (P less than .001). Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of any complication was associated with a 24% increased hazard of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P less that .001). When the analysis was limited to the type of complication, patients with infectious complications (in particular, surgical site infections) had an increased hazard of death (HR, 1.31), predominately those with severe infections (HR, 1.41).

“To our knowledge, this is the largest single study to examine the association of postoperative complications with long-term survival for CRC,” the authors wrote. “Similar to other groups, we have demonstrated that postoperative complications occur in a significant proportion of patients after CRC resection and that most patients with postoperative morbidity have at least one infectious complication.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the potential for selection bias. “Additional limitations include the absence of margin data – which may have a considerable impact on both the risk of organ-space infections and disease recurrence – and the inability to calculate cancer-specific survival and other cancer-specific outcomes,” they wrote.

“Overall all-cause survival, however, is still a commonly used and useful outcome measure, and we have attempted to mitigate the effect of early non–cancer-related mortality with the exclusion of early deaths.”

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

Patients who develop infectious complications after undergoing curative surgery for colorectal cancer face a significantly increased risk of death, results from a large retrospective study showed.

“The association of postoperative complications with long-term survival after major surgery has been suggested by several studies in mixed populations and is to some degree expected and intuitive,” authors led by Dr. Avo Artinyan, of the surgery department at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wrote online Sept. 1 in Annals of Surgery. “It has been difficult, however, to determine a specific cause-effect relationship, particularly because this association is noted even in patients who suffer late mortality, that is, those who presumably recover from postoperative complications.”

In an effort to investigate the effect of postoperative complications on long-term survival after colorectal cancer resection, the researchers evaluated the records of 12,075 patients from the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Central Cancer Registry databases who underwent resection for nonmetastatic colorectal cancer from 1999 to 2009 (Ann. Surg. 2014 Sept. 1 [doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000854]). They categorized patients by presence of any complication within 30 days and by type of complication (infectious vs. noninfectious); excluded patients who died within 90 days of the procedure; and performed univariate and multivariate analyses adjusted for patient, disease, and treatment factors.

The average age of the cohort was 69 years, 98% were men, more than two-thirds (69%) had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification score of 3, and 61% had stage 1 or 2 disease. Dr. Artinyan and his associates found that the overall morbidity and infectious complication rates were 27.8% and 22.5%, respectively.

Compared with patients who had no postoperative complications, those who did were older and had lower postoperative serum albumin, worse functional status, and higher ASA scores (P less than .001). Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of any complication was associated with a 24% increased hazard of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P less that .001). When the analysis was limited to the type of complication, patients with infectious complications (in particular, surgical site infections) had an increased hazard of death (HR, 1.31), predominately those with severe infections (HR, 1.41).

“To our knowledge, this is the largest single study to examine the association of postoperative complications with long-term survival for CRC,” the authors wrote. “Similar to other groups, we have demonstrated that postoperative complications occur in a significant proportion of patients after CRC resection and that most patients with postoperative morbidity have at least one infectious complication.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the potential for selection bias. “Additional limitations include the absence of margin data – which may have a considerable impact on both the risk of organ-space infections and disease recurrence – and the inability to calculate cancer-specific survival and other cancer-specific outcomes,” they wrote.

“Overall all-cause survival, however, is still a commonly used and useful outcome measure, and we have attempted to mitigate the effect of early non–cancer-related mortality with the exclusion of early deaths.”

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

Patients who develop infectious complications after undergoing curative surgery for colorectal cancer face a significantly increased risk of death, results from a large retrospective study showed.

“The association of postoperative complications with long-term survival after major surgery has been suggested by several studies in mixed populations and is to some degree expected and intuitive,” authors led by Dr. Avo Artinyan, of the surgery department at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, wrote online Sept. 1 in Annals of Surgery. “It has been difficult, however, to determine a specific cause-effect relationship, particularly because this association is noted even in patients who suffer late mortality, that is, those who presumably recover from postoperative complications.”

In an effort to investigate the effect of postoperative complications on long-term survival after colorectal cancer resection, the researchers evaluated the records of 12,075 patients from the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Central Cancer Registry databases who underwent resection for nonmetastatic colorectal cancer from 1999 to 2009 (Ann. Surg. 2014 Sept. 1 [doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000854]). They categorized patients by presence of any complication within 30 days and by type of complication (infectious vs. noninfectious); excluded patients who died within 90 days of the procedure; and performed univariate and multivariate analyses adjusted for patient, disease, and treatment factors.

The average age of the cohort was 69 years, 98% were men, more than two-thirds (69%) had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification score of 3, and 61% had stage 1 or 2 disease. Dr. Artinyan and his associates found that the overall morbidity and infectious complication rates were 27.8% and 22.5%, respectively.

Compared with patients who had no postoperative complications, those who did were older and had lower postoperative serum albumin, worse functional status, and higher ASA scores (P less than .001). Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of any complication was associated with a 24% increased hazard of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P less that .001). When the analysis was limited to the type of complication, patients with infectious complications (in particular, surgical site infections) had an increased hazard of death (HR, 1.31), predominately those with severe infections (HR, 1.41).

“To our knowledge, this is the largest single study to examine the association of postoperative complications with long-term survival for CRC,” the authors wrote. “Similar to other groups, we have demonstrated that postoperative complications occur in a significant proportion of patients after CRC resection and that most patients with postoperative morbidity have at least one infectious complication.”

They acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective design and the potential for selection bias. “Additional limitations include the absence of margin data – which may have a considerable impact on both the risk of organ-space infections and disease recurrence – and the inability to calculate cancer-specific survival and other cancer-specific outcomes,” they wrote.

“Overall all-cause survival, however, is still a commonly used and useful outcome measure, and we have attempted to mitigate the effect of early non–cancer-related mortality with the exclusion of early deaths.”

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

FROM ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Postoperative complications after colorectal cancer surgery are associated with decreased long-term survival.

Major finding: The presence of any complication after CRC surgery was associated with a 24% increased hazard of death (hazard ratio, 1.24; P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective evaluation of 12,075 patients who underwent resection for nonmetastatic CRC from 1999-2009.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Resistant infection risk grows by 1% for each day of hospitalization

WASHINGTON – Length of stay seemed to have the greatest impact on contracting multidrug-resistant strains of gram-negative organisms, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization. Each day of hospitalization increased the likelihood of contracting an infection with a gram-negative, multidrug-resistant organism by 1%, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization, said John A. Bosso, Pharm.D.

Researchers led by Dr. Bosso, a professor in the College of Pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, analyzed 949 incidents of documented gram-negative infection during 1998-2014. The study is the first to quantify the potential risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant infection based on length of stay.

We caught up with Dr. Bosso, who presented his findings at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2014, and asked how health care providers and clinicians can mitigate the risks to patient health. Dr. Bosso said clinicians should be sure to identify which patients are most likely to contract a serious infection, advise patients on the risks associated with long hospital stays, and encourage patients to do their part in getting out of the hospital as quickly as possible.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Length of stay seemed to have the greatest impact on contracting multidrug-resistant strains of gram-negative organisms, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization. Each day of hospitalization increased the likelihood of contracting an infection with a gram-negative, multidrug-resistant organism by 1%, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization, said John A. Bosso, Pharm.D.

Researchers led by Dr. Bosso, a professor in the College of Pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, analyzed 949 incidents of documented gram-negative infection during 1998-2014. The study is the first to quantify the potential risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant infection based on length of stay.

We caught up with Dr. Bosso, who presented his findings at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2014, and asked how health care providers and clinicians can mitigate the risks to patient health. Dr. Bosso said clinicians should be sure to identify which patients are most likely to contract a serious infection, advise patients on the risks associated with long hospital stays, and encourage patients to do their part in getting out of the hospital as quickly as possible.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Length of stay seemed to have the greatest impact on contracting multidrug-resistant strains of gram-negative organisms, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization. Each day of hospitalization increased the likelihood of contracting an infection with a gram-negative, multidrug-resistant organism by 1%, with risk maximizing at 10 days of hospitalization, said John A. Bosso, Pharm.D.

Researchers led by Dr. Bosso, a professor in the College of Pharmacy at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, analyzed 949 incidents of documented gram-negative infection during 1998-2014. The study is the first to quantify the potential risk of contracting a multidrug-resistant infection based on length of stay.

We caught up with Dr. Bosso, who presented his findings at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2014, and asked how health care providers and clinicians can mitigate the risks to patient health. Dr. Bosso said clinicians should be sure to identify which patients are most likely to contract a serious infection, advise patients on the risks associated with long hospital stays, and encourage patients to do their part in getting out of the hospital as quickly as possible.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ICAAC 2014

High-dose statins don’t prevent postop AF

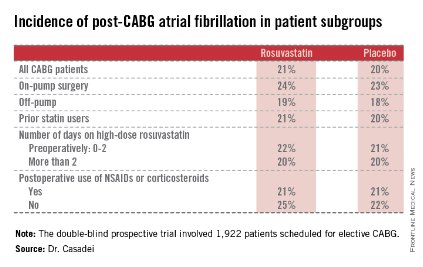

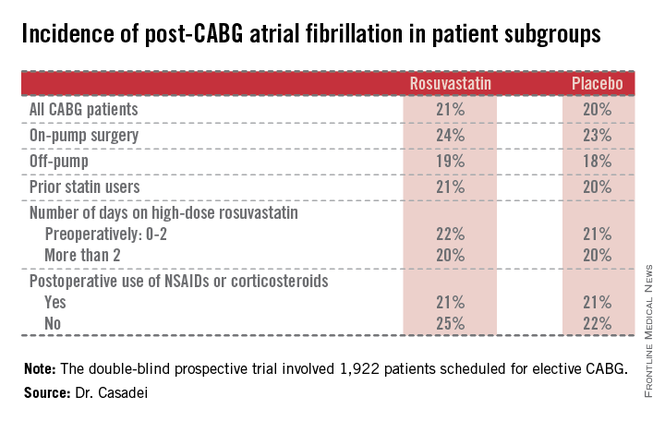

BARCELONA – Intensive perioperative statin therapy in patients undergoing CABG surgery doesn’t protect against postop atrial fibrillation or myocardial injury, according to a large randomized clinical trial hailed as the "definitive" study addressing this issue.

"There are many reasons why these patients should be put on statin treatment, but the prevention of postop complications is not one of them," Dr. Barbara Casadei said in presenting the findings of the Statin Therapy in Cardiac Surgery (STICS) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The STICS results are at odds with conventional wisdom. ESC guidelines give a favorable class IIa, level of evidence B recommendation that "statins should be considered for prevention of new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting, either isolated or in combination with valvular interventions."

"STICS was a very carefully conducted, large scale, robust study that I think has definitely closed the door on this issue," commented Dr. Keith A.A. Fox, professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh and chair of the scientific and clinical program committee at ESC Congress 2014.

STICS was a double-blind prospective trial in which 1,922 patients scheduled for elective CABG were randomized to 20 mg per day of rosuvastatin (Crestor) or placebo starting up to 8 days prior to surgery and continued for 5 days postop. All participants were in sinus rhythm preoperatively, with no history of AF, said Dr. Casadei, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, England.

The two coprimary endpoints in STICS were the incidence of new-onset AF during 5 days of postop Holter monitoring, and evidence of postop myocardial injury as demonstrated in serial troponin I assays.

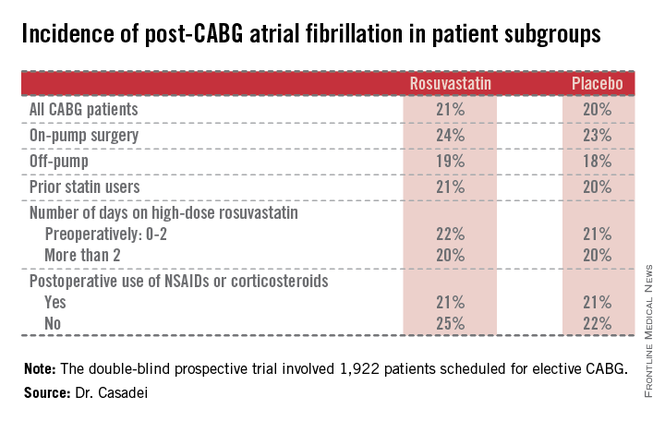

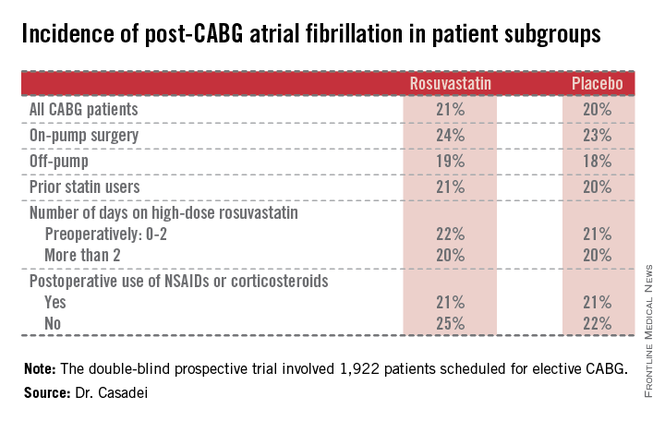

Postop AF occurred in 21% of those given high-intensity therapy with rosuvastatin and 20% of placebo-treated controls. There was no subgroup where rosuvastatin was protective (see graphic).

Troponin I measurements obtained 6, 24, 48, and 120 hours postop showed areas under the curve that were superimposable in the two study groups, meaning perioperative high-dose statin therapy provided absolutely no protection against postop cardiac muscle injury.

Mean hospital length of stay and ICU time didn’t differ between the two groups, either.

The impetus for conducting STICS was recognition that the guidelines’ endorsement of perioperative high-dose statin therapy in conjunction with cardiac surgery was based upon a series of small randomized trials with serious limitations. Although the results of a meta-analysis of the 14 prior trials looked impressive at first glance – a 17% incidence of postop AF in statin-treated patients, compared with 30% in controls, for a near-halving of the risk of this important complication – these 14 studies totaled 1,300 patients, and there were many methodologic shortcomings.

The STICS researchers hypothesized that a large, well-designed trial – bigger than all previous studies combined – would shore up the previously shaky supporting evidence and perhaps provide grounds for statins to win a new indication from regulatory agencies. Post-CABG AF is associated with a doubled risk of stroke and mortality, and excess hospital costs of $8,000-$18,000 dollars per patient.

Discussant Dr. Paulus Kirchhof, a member of the task force that developed the current ESC guidelines (Europace 2010;12:1360-420), said those guidelines now clearly need to be revisited. Beyond that, he added, STICS provides important new contributions in understanding the pathophysiology of AF.

"We know that AF is caused by several vicious circles, and we believe that inflammation could influence those and cause AF. And we also thought that postop AF was the condition where inflammation plays the biggest role. Based upon the negative results with this anti-inflammatory intervention, I think we have to question this concept a bit," said Dr. Kirchhof, professor of cardiovascular sciences at the University of Birmingham, England.

Dr. Casadei countered that she’s not ready to write off postop inflammation entirely as a major trigger of new-onset AF following CABG.

"The inflammation is there. We know from experimental work in animals that there is a strong association between inflammation and postop atrial fibrillation, but whether the association is causal, I think, is still debated. However, it may be that the anti-inflammatory effect of statins is not sufficiently strong to actually prevent this complication," she said.

Discussant Dr. Steven Nissen praised STICS as "an outstanding trial."

"I also think there’s a terribly important lesson here, which is the power of self-delusion in medicine. When we base our guidelines on small, poorly controlled trials, we are often making mistakes. This is one of countless examples where when someone finally does a careful, thoughtful trial, we find out that something that people believe just isn’t true. We can’t cut corners with evidence. We need good randomized trials," declared Dr. Nissen, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

The STICS trial was funded primarily by the British Heart Foundation, the Oxford Biomedical Research Center, and the UK Medical Research Council. In addition, Dr. Casadei reported receiving an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca in conjunction with the trial.

|

| Dr. Hiren Shah |

There are two key lessons from the results of the STICS trial. First, extrapolation of results from biochemical pathways and measured cellular markers does not always translate into meaningful clinical outcomes. Thus, it has long been known from several large trials that statin therapy effectively and rapidly lowers CRP levels both in hyper- and normocholesterolemic patients and that statins are effective in decreasing systemic inflammation. It has also been known that inflammation contributes to the development and maintenance of AF, so it was postulated that by improving endothelial nitric oxide availability, reducing inflammation, and decreasing oxidative stress, and through neurohormonal activation, statins would reduce the incidence of post-op AF. This link was so strong that clinical guidelines adopted limited data from small trials to make treatment recommendations.

This leads us to consider the second key lesson from this study. Trials with small sample size, even when combined across many other trials (1,300 patients were involved across 14 trials in this case), do not always yield reliable results, especially when they have significant limitations, notably not always being blind and having been performed in statin-naive patients only. The large, randomized, and well-designed STICS trial puts to rest an important issue, given the high prevalence of AF after cardiac surgery, which is associated with a longer length of stay, an increased risk of stroke, higher mortality, and greater costs, and should prompt us to consider further evaluation of different strategies to reduce this significant complication.

Dr. Hiren Shah is medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago and an adviser to Hospitalist News. He is the national chair of the Clinician Committee for ACP’s Initiative on Stroke Prevention and Atrial Fibrillation and is the lead physician for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s National Atrial Fibrillation Initiative.

|

| Dr. Hiren Shah |

There are two key lessons from the results of the STICS trial. First, extrapolation of results from biochemical pathways and measured cellular markers does not always translate into meaningful clinical outcomes. Thus, it has long been known from several large trials that statin therapy effectively and rapidly lowers CRP levels both in hyper- and normocholesterolemic patients and that statins are effective in decreasing systemic inflammation. It has also been known that inflammation contributes to the development and maintenance of AF, so it was postulated that by improving endothelial nitric oxide availability, reducing inflammation, and decreasing oxidative stress, and through neurohormonal activation, statins would reduce the incidence of post-op AF. This link was so strong that clinical guidelines adopted limited data from small trials to make treatment recommendations.

This leads us to consider the second key lesson from this study. Trials with small sample size, even when combined across many other trials (1,300 patients were involved across 14 trials in this case), do not always yield reliable results, especially when they have significant limitations, notably not always being blind and having been performed in statin-naive patients only. The large, randomized, and well-designed STICS trial puts to rest an important issue, given the high prevalence of AF after cardiac surgery, which is associated with a longer length of stay, an increased risk of stroke, higher mortality, and greater costs, and should prompt us to consider further evaluation of different strategies to reduce this significant complication.

Dr. Hiren Shah is medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago and an adviser to Hospitalist News. He is the national chair of the Clinician Committee for ACP’s Initiative on Stroke Prevention and Atrial Fibrillation and is the lead physician for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s National Atrial Fibrillation Initiative.

|

| Dr. Hiren Shah |

There are two key lessons from the results of the STICS trial. First, extrapolation of results from biochemical pathways and measured cellular markers does not always translate into meaningful clinical outcomes. Thus, it has long been known from several large trials that statin therapy effectively and rapidly lowers CRP levels both in hyper- and normocholesterolemic patients and that statins are effective in decreasing systemic inflammation. It has also been known that inflammation contributes to the development and maintenance of AF, so it was postulated that by improving endothelial nitric oxide availability, reducing inflammation, and decreasing oxidative stress, and through neurohormonal activation, statins would reduce the incidence of post-op AF. This link was so strong that clinical guidelines adopted limited data from small trials to make treatment recommendations.

This leads us to consider the second key lesson from this study. Trials with small sample size, even when combined across many other trials (1,300 patients were involved across 14 trials in this case), do not always yield reliable results, especially when they have significant limitations, notably not always being blind and having been performed in statin-naive patients only. The large, randomized, and well-designed STICS trial puts to rest an important issue, given the high prevalence of AF after cardiac surgery, which is associated with a longer length of stay, an increased risk of stroke, higher mortality, and greater costs, and should prompt us to consider further evaluation of different strategies to reduce this significant complication.

Dr. Hiren Shah is medical director of the medicine and cardiac telemetry hospitalist unit at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago and an adviser to Hospitalist News. He is the national chair of the Clinician Committee for ACP’s Initiative on Stroke Prevention and Atrial Fibrillation and is the lead physician for the Society of Hospital Medicine’s National Atrial Fibrillation Initiative.

BARCELONA – Intensive perioperative statin therapy in patients undergoing CABG surgery doesn’t protect against postop atrial fibrillation or myocardial injury, according to a large randomized clinical trial hailed as the "definitive" study addressing this issue.

"There are many reasons why these patients should be put on statin treatment, but the prevention of postop complications is not one of them," Dr. Barbara Casadei said in presenting the findings of the Statin Therapy in Cardiac Surgery (STICS) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The STICS results are at odds with conventional wisdom. ESC guidelines give a favorable class IIa, level of evidence B recommendation that "statins should be considered for prevention of new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting, either isolated or in combination with valvular interventions."

"STICS was a very carefully conducted, large scale, robust study that I think has definitely closed the door on this issue," commented Dr. Keith A.A. Fox, professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh and chair of the scientific and clinical program committee at ESC Congress 2014.

STICS was a double-blind prospective trial in which 1,922 patients scheduled for elective CABG were randomized to 20 mg per day of rosuvastatin (Crestor) or placebo starting up to 8 days prior to surgery and continued for 5 days postop. All participants were in sinus rhythm preoperatively, with no history of AF, said Dr. Casadei, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, England.

The two coprimary endpoints in STICS were the incidence of new-onset AF during 5 days of postop Holter monitoring, and evidence of postop myocardial injury as demonstrated in serial troponin I assays.

Postop AF occurred in 21% of those given high-intensity therapy with rosuvastatin and 20% of placebo-treated controls. There was no subgroup where rosuvastatin was protective (see graphic).

Troponin I measurements obtained 6, 24, 48, and 120 hours postop showed areas under the curve that were superimposable in the two study groups, meaning perioperative high-dose statin therapy provided absolutely no protection against postop cardiac muscle injury.

Mean hospital length of stay and ICU time didn’t differ between the two groups, either.

The impetus for conducting STICS was recognition that the guidelines’ endorsement of perioperative high-dose statin therapy in conjunction with cardiac surgery was based upon a series of small randomized trials with serious limitations. Although the results of a meta-analysis of the 14 prior trials looked impressive at first glance – a 17% incidence of postop AF in statin-treated patients, compared with 30% in controls, for a near-halving of the risk of this important complication – these 14 studies totaled 1,300 patients, and there were many methodologic shortcomings.

The STICS researchers hypothesized that a large, well-designed trial – bigger than all previous studies combined – would shore up the previously shaky supporting evidence and perhaps provide grounds for statins to win a new indication from regulatory agencies. Post-CABG AF is associated with a doubled risk of stroke and mortality, and excess hospital costs of $8,000-$18,000 dollars per patient.

Discussant Dr. Paulus Kirchhof, a member of the task force that developed the current ESC guidelines (Europace 2010;12:1360-420), said those guidelines now clearly need to be revisited. Beyond that, he added, STICS provides important new contributions in understanding the pathophysiology of AF.

"We know that AF is caused by several vicious circles, and we believe that inflammation could influence those and cause AF. And we also thought that postop AF was the condition where inflammation plays the biggest role. Based upon the negative results with this anti-inflammatory intervention, I think we have to question this concept a bit," said Dr. Kirchhof, professor of cardiovascular sciences at the University of Birmingham, England.

Dr. Casadei countered that she’s not ready to write off postop inflammation entirely as a major trigger of new-onset AF following CABG.

"The inflammation is there. We know from experimental work in animals that there is a strong association between inflammation and postop atrial fibrillation, but whether the association is causal, I think, is still debated. However, it may be that the anti-inflammatory effect of statins is not sufficiently strong to actually prevent this complication," she said.

Discussant Dr. Steven Nissen praised STICS as "an outstanding trial."

"I also think there’s a terribly important lesson here, which is the power of self-delusion in medicine. When we base our guidelines on small, poorly controlled trials, we are often making mistakes. This is one of countless examples where when someone finally does a careful, thoughtful trial, we find out that something that people believe just isn’t true. We can’t cut corners with evidence. We need good randomized trials," declared Dr. Nissen, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

The STICS trial was funded primarily by the British Heart Foundation, the Oxford Biomedical Research Center, and the UK Medical Research Council. In addition, Dr. Casadei reported receiving an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca in conjunction with the trial.

BARCELONA – Intensive perioperative statin therapy in patients undergoing CABG surgery doesn’t protect against postop atrial fibrillation or myocardial injury, according to a large randomized clinical trial hailed as the "definitive" study addressing this issue.

"There are many reasons why these patients should be put on statin treatment, but the prevention of postop complications is not one of them," Dr. Barbara Casadei said in presenting the findings of the Statin Therapy in Cardiac Surgery (STICS) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The STICS results are at odds with conventional wisdom. ESC guidelines give a favorable class IIa, level of evidence B recommendation that "statins should be considered for prevention of new-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting, either isolated or in combination with valvular interventions."

"STICS was a very carefully conducted, large scale, robust study that I think has definitely closed the door on this issue," commented Dr. Keith A.A. Fox, professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh and chair of the scientific and clinical program committee at ESC Congress 2014.

STICS was a double-blind prospective trial in which 1,922 patients scheduled for elective CABG were randomized to 20 mg per day of rosuvastatin (Crestor) or placebo starting up to 8 days prior to surgery and continued for 5 days postop. All participants were in sinus rhythm preoperatively, with no history of AF, said Dr. Casadei, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, England.

The two coprimary endpoints in STICS were the incidence of new-onset AF during 5 days of postop Holter monitoring, and evidence of postop myocardial injury as demonstrated in serial troponin I assays.

Postop AF occurred in 21% of those given high-intensity therapy with rosuvastatin and 20% of placebo-treated controls. There was no subgroup where rosuvastatin was protective (see graphic).

Troponin I measurements obtained 6, 24, 48, and 120 hours postop showed areas under the curve that were superimposable in the two study groups, meaning perioperative high-dose statin therapy provided absolutely no protection against postop cardiac muscle injury.

Mean hospital length of stay and ICU time didn’t differ between the two groups, either.

The impetus for conducting STICS was recognition that the guidelines’ endorsement of perioperative high-dose statin therapy in conjunction with cardiac surgery was based upon a series of small randomized trials with serious limitations. Although the results of a meta-analysis of the 14 prior trials looked impressive at first glance – a 17% incidence of postop AF in statin-treated patients, compared with 30% in controls, for a near-halving of the risk of this important complication – these 14 studies totaled 1,300 patients, and there were many methodologic shortcomings.

The STICS researchers hypothesized that a large, well-designed trial – bigger than all previous studies combined – would shore up the previously shaky supporting evidence and perhaps provide grounds for statins to win a new indication from regulatory agencies. Post-CABG AF is associated with a doubled risk of stroke and mortality, and excess hospital costs of $8,000-$18,000 dollars per patient.

Discussant Dr. Paulus Kirchhof, a member of the task force that developed the current ESC guidelines (Europace 2010;12:1360-420), said those guidelines now clearly need to be revisited. Beyond that, he added, STICS provides important new contributions in understanding the pathophysiology of AF.

"We know that AF is caused by several vicious circles, and we believe that inflammation could influence those and cause AF. And we also thought that postop AF was the condition where inflammation plays the biggest role. Based upon the negative results with this anti-inflammatory intervention, I think we have to question this concept a bit," said Dr. Kirchhof, professor of cardiovascular sciences at the University of Birmingham, England.

Dr. Casadei countered that she’s not ready to write off postop inflammation entirely as a major trigger of new-onset AF following CABG.

"The inflammation is there. We know from experimental work in animals that there is a strong association between inflammation and postop atrial fibrillation, but whether the association is causal, I think, is still debated. However, it may be that the anti-inflammatory effect of statins is not sufficiently strong to actually prevent this complication," she said.

Discussant Dr. Steven Nissen praised STICS as "an outstanding trial."

"I also think there’s a terribly important lesson here, which is the power of self-delusion in medicine. When we base our guidelines on small, poorly controlled trials, we are often making mistakes. This is one of countless examples where when someone finally does a careful, thoughtful trial, we find out that something that people believe just isn’t true. We can’t cut corners with evidence. We need good randomized trials," declared Dr. Nissen, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

The STICS trial was funded primarily by the British Heart Foundation, the Oxford Biomedical Research Center, and the UK Medical Research Council. In addition, Dr. Casadei reported receiving an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca in conjunction with the trial.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2014

Key clinical point: Perioperative statin therapy in patients undergoing CABG failed to protect against new-onset postop atrial fibrillation.

Major finding: The incidence of postop atrial fibrillation within 5 days post-CABG was 21% in patients randomized to 20 mg/day of rosuvastatin and 20% in placebo-treated controls.

Data source: The multicenter STICS trial included 1,922 randomized patients scheduled for elective CABG.

Disclosures: STICS was funded by the British Heart Foundation, the Oxford Biomedical Research Center, and the UK Medical Research Council. The presenter reported having received a research grant from AstraZeneca.

COPPS-2 curtails colchicine enthusiasm in cardiac surgery

Patients undergoing cardiac surgery who took colchicine had significantly less postpericardiotomy syndrome than did those on placebo, but this protective effect did not extend to postoperative atrial fibrillation and pericardial or pleural effusions in the double-blind COPPS-2 trial.

The failure of colchicine to prevent postoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) was probably due to more frequent adverse events (36 vs. 21 with placebo), especially gastrointestinal intolerance (26 vs. 12), and drug discontinuation (39 vs. 32), since a prespecified on-treatment analysis showed a significant reduction in AF in patients tolerating the drug, Dr. Massimo Imazio reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The high rate of adverse effects is a reason for concern and suggests that colchicine should be considered only in well-selected patients," Dr. Imazio and his associates wrote in an article on COPPS-2 simultaneously published online (JAMA 2014 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.11026]).

Colchicine has been a promising strategy for postpericardiotomy syndrome prevention, besting methylprednisolone and aspirin in a large meta-analysis (Am. J. Cardiol. 2011;108:575-9).

In the largest trial, COPPS (Colchicine for the Prevention of the Postpericardiotomy Syndrome), Dr. Imazio reported that colchicine significantly reduced the incidence of postpericardiotomy syndrome (8.9% vs. 21.1%), postoperative pericardial effusions (relative risk reduction, 43.9%), and pleural effusions (RRR, 52.3%) at 12 months, compared with placebo (Am. Heart J. 2011;162:527-32 and Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:2749-54). Colchicine was given for 1 month, beginning on the third postoperative day with a 1-mg twice-daily loading dose.