User login

What are your weaknesses?

In a video posted to TikTok by the comedian Will Flanary, MD, better known to his followers as Dr. Glaucomflecken, he imitates a neurosurgical residency interview. With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Dr. Glaucomflecken poses as the attending, asking: “What are your weaknesses?”

The residency applicant answers without hesitation: “My physiological need for sleep.” “What are your strengths?” The resident replies with the hard, steely stare of the determined and uninitiated: “My desire to eliminate my physiological need for sleep.”

If you follow Dr. Glaucomflecken on Twitter, you might know the skit I’m referencing. For many physicians and physicians-in-training, what makes the satire successful is its reflection of reality.

Many things have changed in medicine since his time, but the tired trope of the sleepless surgeon hangs on. Undaunted, I spent my second and third year of medical school accumulating accolades, conducting research, and connecting with mentors with the singular goal of joining the surgical ranks.

Midway through my third year, I completed a month-long surgical subinternship designed to give students a taste of what life would look like as an intern. I loved the operating room; it felt like the difference between being on dry land and being underwater. There were fewer distractions – your patient in the spotlight while everything else receded to the shadows.

However, as the month wore on, something stronger took hold. I couldn’t keep my eyes open in the darkened operating rooms and had to decline stools, fearing that I would fall asleep if I sat down.

On early morning prerounds, it’s 4:50 a.m. when I glance at the clock and pull back the curtain, already apologizing. My patient rolls over, flashing a wry smile. “Do you ever go home?” I’ve seen residents respond to this exact question in various ways. I live here. Yes. No. Soon. Not enough. My partner doesn’t think so.

There are days and, yes, years when we are led to believe this is what we live for: to be constantly available to our patients. It feels like a hollow victory when the patient, 2 days out from a total colectomy, begins to worry about your personal life. I ask her how she slept (not enough), any fevers (no), vomiting (no), urinating (I pause – she has a catheter).

My favorite part of these early morning rounds is the pause in my scripted litany of questions to listen to heart and lungs. It never fails to feel sacred: Patients become so quiet and still that I can’t help but think they have faith in me. Without prompting, she slides the back of her hospital gown forward like a curtain, already taking deep breaths so I can hear her lungs.

I look outside. The streetlights are still on, and from the seventh-floor window, I can watch staff making their way through the sliding double-doors, just beyond the yellowed pools of streetlight. I smile. I love medicine. I’m so tired.

For many in medicine, we are treated, and thus behave, as though our ability to manipulate physiology should also apply within the borders of our bodies: commanding less sleep, food, or bathroom breaks.

It places health care workers solidly in the realm of superhuman, living beyond one’s corporeal needs. The pandemic only heightened this misappropriation – adding hero and setting out a pedestal for health care workers to make their ungainly ascent. This kind of unsolicited admiration implicitly implies inhumanness, an otherness.

What would it look like if we started treating ourselves less like physicians and more like patients? I wish I was offering a solution, but really this is just a story.

To students rising through the ranks of medical training, identify what it is you need early and often. I can count on one hand how many physicians I’ve seen take a lunch break – even 10 minutes. Embrace hard work and self-preservation equally. My hope is that if enough of us take this path, it just might become a matter of course.

Dr. Meffert is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Washington. Dr. Meffert disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a video posted to TikTok by the comedian Will Flanary, MD, better known to his followers as Dr. Glaucomflecken, he imitates a neurosurgical residency interview. With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Dr. Glaucomflecken poses as the attending, asking: “What are your weaknesses?”

The residency applicant answers without hesitation: “My physiological need for sleep.” “What are your strengths?” The resident replies with the hard, steely stare of the determined and uninitiated: “My desire to eliminate my physiological need for sleep.”

If you follow Dr. Glaucomflecken on Twitter, you might know the skit I’m referencing. For many physicians and physicians-in-training, what makes the satire successful is its reflection of reality.

Many things have changed in medicine since his time, but the tired trope of the sleepless surgeon hangs on. Undaunted, I spent my second and third year of medical school accumulating accolades, conducting research, and connecting with mentors with the singular goal of joining the surgical ranks.

Midway through my third year, I completed a month-long surgical subinternship designed to give students a taste of what life would look like as an intern. I loved the operating room; it felt like the difference between being on dry land and being underwater. There were fewer distractions – your patient in the spotlight while everything else receded to the shadows.

However, as the month wore on, something stronger took hold. I couldn’t keep my eyes open in the darkened operating rooms and had to decline stools, fearing that I would fall asleep if I sat down.

On early morning prerounds, it’s 4:50 a.m. when I glance at the clock and pull back the curtain, already apologizing. My patient rolls over, flashing a wry smile. “Do you ever go home?” I’ve seen residents respond to this exact question in various ways. I live here. Yes. No. Soon. Not enough. My partner doesn’t think so.

There are days and, yes, years when we are led to believe this is what we live for: to be constantly available to our patients. It feels like a hollow victory when the patient, 2 days out from a total colectomy, begins to worry about your personal life. I ask her how she slept (not enough), any fevers (no), vomiting (no), urinating (I pause – she has a catheter).

My favorite part of these early morning rounds is the pause in my scripted litany of questions to listen to heart and lungs. It never fails to feel sacred: Patients become so quiet and still that I can’t help but think they have faith in me. Without prompting, she slides the back of her hospital gown forward like a curtain, already taking deep breaths so I can hear her lungs.

I look outside. The streetlights are still on, and from the seventh-floor window, I can watch staff making their way through the sliding double-doors, just beyond the yellowed pools of streetlight. I smile. I love medicine. I’m so tired.

For many in medicine, we are treated, and thus behave, as though our ability to manipulate physiology should also apply within the borders of our bodies: commanding less sleep, food, or bathroom breaks.

It places health care workers solidly in the realm of superhuman, living beyond one’s corporeal needs. The pandemic only heightened this misappropriation – adding hero and setting out a pedestal for health care workers to make their ungainly ascent. This kind of unsolicited admiration implicitly implies inhumanness, an otherness.

What would it look like if we started treating ourselves less like physicians and more like patients? I wish I was offering a solution, but really this is just a story.

To students rising through the ranks of medical training, identify what it is you need early and often. I can count on one hand how many physicians I’ve seen take a lunch break – even 10 minutes. Embrace hard work and self-preservation equally. My hope is that if enough of us take this path, it just might become a matter of course.

Dr. Meffert is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Washington. Dr. Meffert disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a video posted to TikTok by the comedian Will Flanary, MD, better known to his followers as Dr. Glaucomflecken, he imitates a neurosurgical residency interview. With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Dr. Glaucomflecken poses as the attending, asking: “What are your weaknesses?”

The residency applicant answers without hesitation: “My physiological need for sleep.” “What are your strengths?” The resident replies with the hard, steely stare of the determined and uninitiated: “My desire to eliminate my physiological need for sleep.”

If you follow Dr. Glaucomflecken on Twitter, you might know the skit I’m referencing. For many physicians and physicians-in-training, what makes the satire successful is its reflection of reality.

Many things have changed in medicine since his time, but the tired trope of the sleepless surgeon hangs on. Undaunted, I spent my second and third year of medical school accumulating accolades, conducting research, and connecting with mentors with the singular goal of joining the surgical ranks.

Midway through my third year, I completed a month-long surgical subinternship designed to give students a taste of what life would look like as an intern. I loved the operating room; it felt like the difference between being on dry land and being underwater. There were fewer distractions – your patient in the spotlight while everything else receded to the shadows.

However, as the month wore on, something stronger took hold. I couldn’t keep my eyes open in the darkened operating rooms and had to decline stools, fearing that I would fall asleep if I sat down.

On early morning prerounds, it’s 4:50 a.m. when I glance at the clock and pull back the curtain, already apologizing. My patient rolls over, flashing a wry smile. “Do you ever go home?” I’ve seen residents respond to this exact question in various ways. I live here. Yes. No. Soon. Not enough. My partner doesn’t think so.

There are days and, yes, years when we are led to believe this is what we live for: to be constantly available to our patients. It feels like a hollow victory when the patient, 2 days out from a total colectomy, begins to worry about your personal life. I ask her how she slept (not enough), any fevers (no), vomiting (no), urinating (I pause – she has a catheter).

My favorite part of these early morning rounds is the pause in my scripted litany of questions to listen to heart and lungs. It never fails to feel sacred: Patients become so quiet and still that I can’t help but think they have faith in me. Without prompting, she slides the back of her hospital gown forward like a curtain, already taking deep breaths so I can hear her lungs.

I look outside. The streetlights are still on, and from the seventh-floor window, I can watch staff making their way through the sliding double-doors, just beyond the yellowed pools of streetlight. I smile. I love medicine. I’m so tired.

For many in medicine, we are treated, and thus behave, as though our ability to manipulate physiology should also apply within the borders of our bodies: commanding less sleep, food, or bathroom breaks.

It places health care workers solidly in the realm of superhuman, living beyond one’s corporeal needs. The pandemic only heightened this misappropriation – adding hero and setting out a pedestal for health care workers to make their ungainly ascent. This kind of unsolicited admiration implicitly implies inhumanness, an otherness.

What would it look like if we started treating ourselves less like physicians and more like patients? I wish I was offering a solution, but really this is just a story.

To students rising through the ranks of medical training, identify what it is you need early and often. I can count on one hand how many physicians I’ve seen take a lunch break – even 10 minutes. Embrace hard work and self-preservation equally. My hope is that if enough of us take this path, it just might become a matter of course.

Dr. Meffert is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Washington. Dr. Meffert disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The testing we order should help, not hurt

Ordering and interpreting tests is at the heart of what we do as family physicians. Ordering tests judiciously and interpreting them accurately is not easy. The Choosing Wisely campaign1 has focused our attention on the need to think carefully before ordering tests, whether they be laboratory tests or imaging. Before ordering any test, one should always ask: Is the result of this test going to help me make better decisions about managing this patient?

I would like to highlight and expand on 2 problematic issues Kaminski and Venkat raise in their excellent article on testing in this issue of JFP.2

First, they advise us to know the pretest probability of a disease before we order a test. If we order a test on a patient for whom the probability of disease is very low, a positive result is likely to be a false-positive and mislead us into thinking the patient has the disease when he does not. If we order a test for a patient with a high probability of disease and the result is negative, there is great danger of a false-negative. We might think the patient does not have the disease, but she does.

There is a deeper problem here, however. Primary care physicians are notorious for overestimating disease probability. In a recent study, primary care clinicians overestimated the pretest probability of disease 2- to 10-fold in scenarios involving 4 common diagnoses: breast cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), pneumonia, and urinary tract infection.3 Even after receiving a negative test result, clinicians still overestimated the chance of disease in all the scenarios. For example, when presented with a 43-year-old premenopausal woman with atypical chest pain and a normal electrocardiogram, clinicians’ average estimate of the probability of CAD was 10%—considerably higher than true estimates of 1% to 4.4%.3

To improve your accuracy in judging pretest probabilities, see the diagnostic test calculators in Essential Evidence Plus (www.essentialevidenceplus.com/).

Secondly, Kaminski and Venkat advise us to try to avoid the testing cascade.2 The associated dangers to patients are considerable. For a cautionary tale, I recommend you read the essay by Michael B. Rothberg, MD, MPH, called “The $50,000 Physical”.4 Dr. Rothberg describes the testing cascade his 85-year-old father experienced, which led to a liver biopsy that nearly killed him from post-biopsy bleeding. Always remember: Testing is a double-edged sword. It can help—or harm—your patients.

1. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. Accessed June 30, 2022. www.choosingwisely.org/

2. Kaminski M, Venkat N. A judicious approach to ordering lab tests. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:245-250. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0444

3. Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Owczarzak J, et al. Accuracy of practitioner estimates of probability of diagnosis before and after testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:747-755. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0269

4. Rothberg MB. The $50 000 physical. JAMA. 2020;323:1682-1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2866

Ordering and interpreting tests is at the heart of what we do as family physicians. Ordering tests judiciously and interpreting them accurately is not easy. The Choosing Wisely campaign1 has focused our attention on the need to think carefully before ordering tests, whether they be laboratory tests or imaging. Before ordering any test, one should always ask: Is the result of this test going to help me make better decisions about managing this patient?

I would like to highlight and expand on 2 problematic issues Kaminski and Venkat raise in their excellent article on testing in this issue of JFP.2

First, they advise us to know the pretest probability of a disease before we order a test. If we order a test on a patient for whom the probability of disease is very low, a positive result is likely to be a false-positive and mislead us into thinking the patient has the disease when he does not. If we order a test for a patient with a high probability of disease and the result is negative, there is great danger of a false-negative. We might think the patient does not have the disease, but she does.

There is a deeper problem here, however. Primary care physicians are notorious for overestimating disease probability. In a recent study, primary care clinicians overestimated the pretest probability of disease 2- to 10-fold in scenarios involving 4 common diagnoses: breast cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), pneumonia, and urinary tract infection.3 Even after receiving a negative test result, clinicians still overestimated the chance of disease in all the scenarios. For example, when presented with a 43-year-old premenopausal woman with atypical chest pain and a normal electrocardiogram, clinicians’ average estimate of the probability of CAD was 10%—considerably higher than true estimates of 1% to 4.4%.3

To improve your accuracy in judging pretest probabilities, see the diagnostic test calculators in Essential Evidence Plus (www.essentialevidenceplus.com/).

Secondly, Kaminski and Venkat advise us to try to avoid the testing cascade.2 The associated dangers to patients are considerable. For a cautionary tale, I recommend you read the essay by Michael B. Rothberg, MD, MPH, called “The $50,000 Physical”.4 Dr. Rothberg describes the testing cascade his 85-year-old father experienced, which led to a liver biopsy that nearly killed him from post-biopsy bleeding. Always remember: Testing is a double-edged sword. It can help—or harm—your patients.

Ordering and interpreting tests is at the heart of what we do as family physicians. Ordering tests judiciously and interpreting them accurately is not easy. The Choosing Wisely campaign1 has focused our attention on the need to think carefully before ordering tests, whether they be laboratory tests or imaging. Before ordering any test, one should always ask: Is the result of this test going to help me make better decisions about managing this patient?

I would like to highlight and expand on 2 problematic issues Kaminski and Venkat raise in their excellent article on testing in this issue of JFP.2

First, they advise us to know the pretest probability of a disease before we order a test. If we order a test on a patient for whom the probability of disease is very low, a positive result is likely to be a false-positive and mislead us into thinking the patient has the disease when he does not. If we order a test for a patient with a high probability of disease and the result is negative, there is great danger of a false-negative. We might think the patient does not have the disease, but she does.

There is a deeper problem here, however. Primary care physicians are notorious for overestimating disease probability. In a recent study, primary care clinicians overestimated the pretest probability of disease 2- to 10-fold in scenarios involving 4 common diagnoses: breast cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), pneumonia, and urinary tract infection.3 Even after receiving a negative test result, clinicians still overestimated the chance of disease in all the scenarios. For example, when presented with a 43-year-old premenopausal woman with atypical chest pain and a normal electrocardiogram, clinicians’ average estimate of the probability of CAD was 10%—considerably higher than true estimates of 1% to 4.4%.3

To improve your accuracy in judging pretest probabilities, see the diagnostic test calculators in Essential Evidence Plus (www.essentialevidenceplus.com/).

Secondly, Kaminski and Venkat advise us to try to avoid the testing cascade.2 The associated dangers to patients are considerable. For a cautionary tale, I recommend you read the essay by Michael B. Rothberg, MD, MPH, called “The $50,000 Physical”.4 Dr. Rothberg describes the testing cascade his 85-year-old father experienced, which led to a liver biopsy that nearly killed him from post-biopsy bleeding. Always remember: Testing is a double-edged sword. It can help—or harm—your patients.

1. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. Accessed June 30, 2022. www.choosingwisely.org/

2. Kaminski M, Venkat N. A judicious approach to ordering lab tests. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:245-250. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0444

3. Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Owczarzak J, et al. Accuracy of practitioner estimates of probability of diagnosis before and after testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:747-755. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0269

4. Rothberg MB. The $50 000 physical. JAMA. 2020;323:1682-1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2866

1. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. Accessed June 30, 2022. www.choosingwisely.org/

2. Kaminski M, Venkat N. A judicious approach to ordering lab tests. J Fam Pract. 2022;71:245-250. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0444

3. Morgan DJ, Pineles L, Owczarzak J, et al. Accuracy of practitioner estimates of probability of diagnosis before and after testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:747-755. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0269

4. Rothberg MB. The $50 000 physical. JAMA. 2020;323:1682-1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2866

A judicious approach to ordering lab tests

CASE

A 35-year-old man arrives for an annual wellness visit with no specific complaints and no significant personal or family history. His normal exam includes a blood pressure of 110/74 mm Hg and a body mass index (BMI) of 23.6. You order “routine labs” for prevention, which include a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), fasting lipid profile, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and 25(OH) vitamin D tests. Are you practicing value-based laboratory testing?

The answer to this question appears in the Case discussion at the end of the article.

Value-based care, including care provided through laboratory testing, can achieve the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim of improving population health, improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction), and reducing cost: Value = (Quality x Patient experience) / Cost.1

As quality and patient experience rise and cost falls, the value of care increases. Unnecessary lab testing, however, can negatively impact this equation:

- Error introduced by unnecessary testing can adversely affect quality.

- Patients experience inconvenience and sometimes cascades of testing, in addition to financial responsibility, from unnecessary testing.

- Low-value testing also contributes to work burden and provider burnout by requiring additional review and follow-up.

Rising health care costs are approaching 18% of the US gross domestic product, driven in large part by a wasteful and inefficient care delivery system.2 One review of “waste domains” identified by the Institute of Medicine estimates that approximately one-quarter of health care costs represent waste, including overtreatment, breakdowns of care coordination, and pricing that fails to correlate to the level of care received.3 High-volume, low-cost testing contributes more to total cost than low-volume, high-cost tests.4

Provider and system factors that contribute to ongoing waste

A lack of awareness of waste and how to reduce it contribute to the problem, as does an underappreciation of the harmful effects caused by incidental abnormal results.

Provider intolerance of diagnostic uncertainty often leads to ordering even more tests.

Continue to: Also, a hope of avoiding...

Also, a hope of avoiding missed diagnoses and potential lawsuits leads to defensive practice and more testing. In addition, patients and family members can exert pressure based on a belief that more testing represents better care. Of course, financial revenues from testing may come into play, with few disincentives to forgo testing. Something that also comes into play is that evidence-based guidance on cost-effective laboratory testing may be lacking, or there may be a lack of knowledge on how to access existing evidence.

Automated systems can facilitate wasteful laboratory testing, and the heavy testing practices of hospitals and specialists may be inappropriately applied to outpatient primary care.

Factors affecting the cost of laboratory testing

Laboratory test results drive 70% of today’s medical decisions.5 Negotiated insurance payment for tests is usually much less than the direct out-of-pocket costs charged to the patient. Without insurance, lab tests can cost patients between $100 and $1000.6 If multiple tests are ordered, the costs could likely be many thousands of dollars.

Actual costs typically vary by the testing facility, the patient’s health plan, and location in the United States; hospital-based testing tends to be the most expensive. Insurers will pay for lab tests with appropriate indications that are covered in the contract with the provider.6

Choosing Wisely initiative weighs in on lab testing

Choosing Wisely, a prominent initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, promotes appropriate resource utilization through educational campaigns that detail how to avoid unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures.7 Recommendations are based largely on specialty society consensus and disease-oriented evidence. Choosing Wisely recommendations advise against the following7:

- performing laboratory blood testing unless clinically indicated or necessary for diagnosis or management, in order to avoid iatrogenic anemia. (American Academy of Family Physicians; Society for the Advancement of Patient Blood Management)

- requesting just a serum creatinine to test adult patients with diabetes and/or hypertension for chronic kidney disease. Use the kidney profile: serum creatinine with estimated glomerular filtration rate and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio. (American Society for Clinical Pathology)

- routinely screening for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen test. It should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making with the patient. (American Academy of Family Physicians; American Urological Association)

- screening for genital herpes simplex virus infectionFrutiger LT Std in asymptomatic adults, including pregnant women. (American Academy of Family Physicians)

- performing preoperative medical tests for eye surgery unless there are specific medical indications. (American Academy of Ophthalmology)

Sequential steps to takefor value-based lab ordering

Ask the question: “How will ordering this specific test change the management of my patient?” From there, take sequential steps using sound, evidence-based pathways. Morgan and colleagues8 outline the following practical approaches to rational test ordering:

- Perform a thorough clinical assessment.

- Consider the probability and implications of a positive test result.

- Practice patient-centered communication: address the patient’s concerns and discuss the risks and benefits of tests and how they will influence management.

- Follow clinical guidelines when available.

- Avoid ordering tests to reassure the patient; unnecessary tests with insignificant results do little to reduce patient anxieties.

- Avoid letting uncertainty drive unnecessary testing. Watchful waiting can allow time for the illness to resolve or declare itself.

Let’s consider this approach in the context of 4 areas: preventive care, diagnostic evaluation, ongoing management of chronic conditions, and preoperative testing.

Continue to: Preventive guidance from the USPSTF

Preventive guidance from the USPSTF

An independent volunteer panel of 16 national experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine develop recommendations for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).9 These guidelines are based on evidence and are updated as new evidence surfaces. Thirteen recommendations, some of which advise avoiding preventive procedures that could cause harm to patients, cover laboratory tests used in screening for conditions such as hyperlipidemia10 and prostate cancer.11 We review the ones pertinent to our patient later at the end of the Case.

While the target audience for USPSTF recommendations is clinicians who provide preventive care, the recommendations are widely followed by policymakers, managed care organizations, public and private payers, quality improvement organizations, research institutions, and patients.

Take a critical look at how you approach the diagnostic evaluation

To reduce unnecessary testing in the diagnostic evaluation of patients, first consider pretest probability, test sensitivity and specificity, narrowly out-of-range tests, habitually paired tests, and repetitive laboratory testing.

Pretest probability, and test sensitivity and specificity. Pretest probability is the estimated chance that the patient has the disease before the test result is known. In a patient with low pretest probability of a disease, the ability to conclusively arrive at the diagnosis with one positive result is limited. Similarly, for tests in patients with high pretest probability of disease, a negative test cannot be used to firmly rule out a diagnosis.12

Reliability also depends on test sensitivity (the proportion of true positive results) and specificity (the proportion of true negative results). A test with high sensitivity but low specificity will generate more false-positive results, with potential harm to patients who do not have a disease.

The pretest probability along with test sensitivity and specificity help a clinician to interpret a test result, and even decide whether to order the test at all. For example, the anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 86%13; it will always be positive in a patient with SLE. But when applied to individuals with low likelihood of SLE, false-positives are more common; the ANA is falsely positive in up to 14% of healthy individuals, depending on the population studied.13

Ordering a test may be unnecessary if the results will not change the treatment plan. For example, in a female patient with classic symptoms of an uncomplicated urinary tract infection, a urine culture and even a urinalysis may not change treatment.

Continue to: Narrowly out-of-range tests

Narrowly out-of-range tests. Test results that fall just outside the “normal” range may be of questionable significance. When an asymptomatic patient has mildly elevated liver enzymes, should additional tests be ordered to avoid missing a treatable disorder? In these scenarios, a history, including possible contributing factors such as alcohol or substance misuse, must be paired with the clinical presentation to assess pre-test probability of a particular condition.14 Repeating a narrowly out-of-range test is an option in patients when follow-up is possible. Alternatively, you could pursue watchful waiting and monitor a minor abnormality over time while being vigilant for clinical changes. This whole-patient approach will guide the decision of whether to order additional testing.

Habitually paired tests. Reflexively ordering tests together often contributes to unnecessary testing. Examples of commonly paired tests are serum lipase with amylase, C-reactive protein (CRP) with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and TSH with free T4 to monitor patients with treated hypothyroidism. These tests add minimal value together and can be decoupled.15-17 Evidence supports ordering serum lipase alone, CRP instead of ESR, and TSH alone for monitoring thyroid status.

Some commonly paired tests may not even be necessary for diagnosis. The well-established Rotterdam Criteria for diagnosing polycystic ovary syndrome specify clinical features and ovarian ultrasound for diagnosis.18 They do not require measurement of commonly ordered follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone for diagnosis.

Serial rather than parallel testing, a “2-step approach,” is a strategy made easier with the advent of the electronic medical record (EMR) and computerized lab systems.8 These records and lab systems allow providers to order reflex tests, and to add on additional tests, if necessary, to an existing blood specimen.

Repetitive laboratory testing. Repetitive inpatient laboratory testing in patients who are clinically stable is wasteful and potentially harmful. Interventions involving physician education alone show mixed results, but combining education with clinician audit and feedback, along with EMR-enabled restrictive ordering, have resulted in significant and sustained reductions in repetitive laboratory testing.19

Continue to: Ongoing management of chronic conditions

Ongoing management of chronic conditions

Evidence-based guidelines support choices of tests and testing intervals for ongoing management of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Diabetes. Guidelines also define quality standards that are applied to value-based contracts. For example, the American Diabetes Association recommends assessing A1C every 6 months in patients whose type 2 diabetes is under stable control.20

Hyperlipidemia. For patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia, 2018 clinical practice guidelines published by multiple specialty societies recommend assessing adherence and response to lifestyle changes and LDL-C–lowering medications with repeat lipid measurement 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation or dose adjustment, repeated every 3 to 12 months as needed.21

Hypertension. With a new diagnosis of hypertension, guidelines advise an initial assessment for comorbidities and end-organ damage with an electrocardiogram, urinalysis, glucose level, blood count, electrolytes, creatinine, calcium, lipids, and urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. For ongoing monitoring, guidelines recommend assessment for end-organ damage through regular measurements of creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, and urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio. Initiation and alteration of medications should prompt appropriate additional lab follow-up—eg, a measurement of serum potassium after starting a diuretic.22

Preoperative testing

Preoperative testing is overused in low-risk, ambulatory surgery. And testing, even with abnormal results, does not affect postoperative outcomes.23

Continue to: The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System

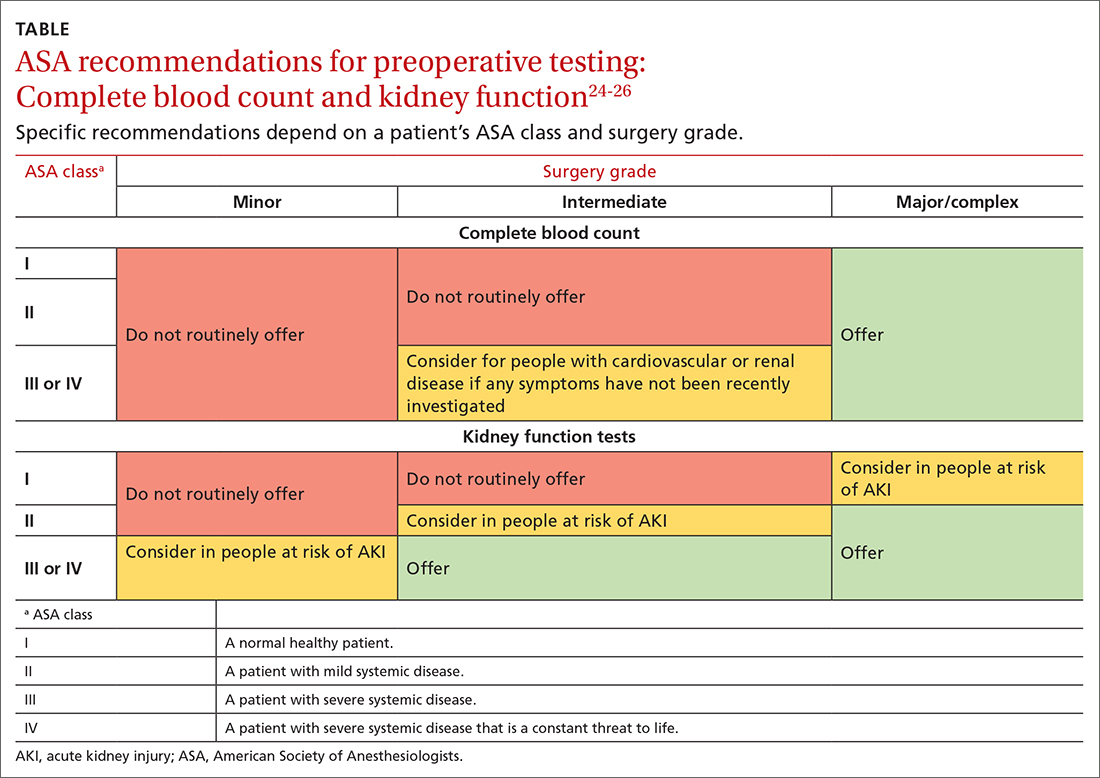

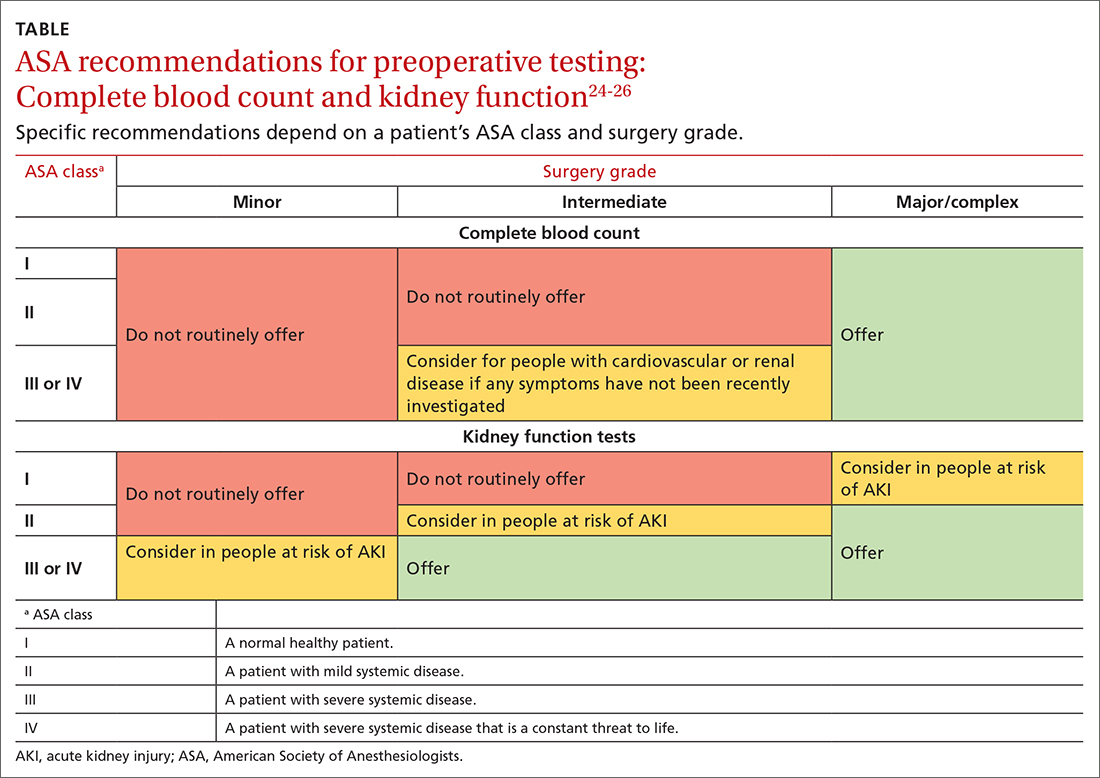

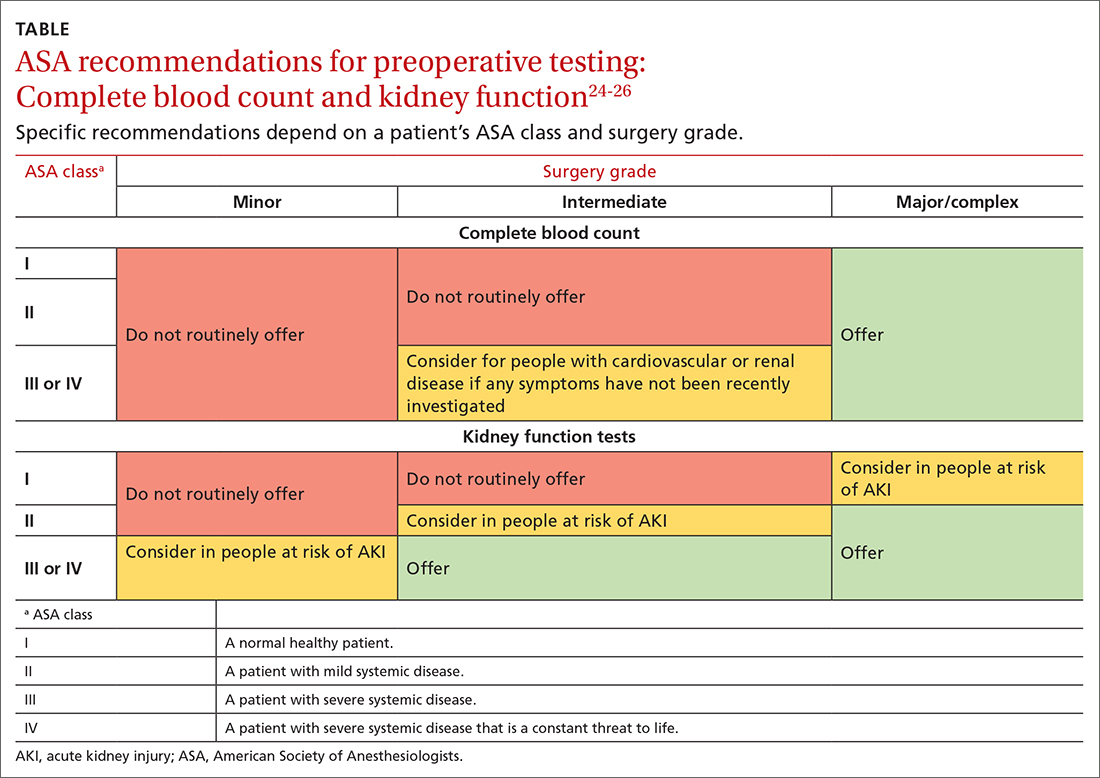

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System, which has been in use for more than 60 years, considers the patient’s physical status (ASA grades I-VI),24 and when paired with surgery grades of minor, intermediate, and major/complex, can help assess preoperative risk and guide preoperative testing (TABLE).24-26

Preoperative medical testing did not reduce the risk of medical adverse events during or after cataract surgery when compared with selective or no testing.27 Unnecessary preoperative testing can lead to a nonproductive cascade of additional investigations. In a 2018 study of Medicare beneficiaries, unnecessary routine preoperative testing and testing sequelae for cataract surgery was calculated to cost Medicare up to $45.4 million annually.28

CASE

You would not be practicing value-based laboratory testing, according to the USPSTF, if you ordered a CMP, fasting lipid profile, and TSH and 25(OH) vitamin D tests for this healthy 35-year-old man whose family history, blood pressure, and BMI do not put him at elevated risk. Universal lipid screening (Grade Ba) is recommended for all adults ages 40 to 75. Thyroid screening tests and measurement of 25(OH) vitamin D level (I statementsa) are not recommended. The USPSTF has not evaluated chemistry panels for screening.

The USPSTF would recommend the following actions for this patient:

- Screen for HIV (ages 15 to 65 years; and younger or older if patient is at risk). (A recommendationa,29)

- Screen for hepatitis C virus (in those ages 18 to 79). (B recommendation30)

The following USPSTF recommendations might have come into play if this patient had certain risk factors, or if the patient had been a woman:

- Screen for diabetes if the patient is overweight or obese (B recommendation).

- Screen for hepatitis B in adults at risk (B recommendation).

- Screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia in women at risk (B recommendation). Such screening has an “I”statement for screening men at risk.

Continue to: As noted, costs of laboratory...

As noted, costs of laboratory testing vary widely, depending upon what tests are ordered, what type of insurance the patient has, and which tests the patient’s insurance covers. Who performs the testing also factors into the cost. Payers negotiate reduced fees for commercial lab testing, but potential out-of-pocket costs to patients are much higher.

For our healthy 35-year-old man, the cost of the initially proposed testing (CMP, lipid panel, TSH, and 25[OH] vitamin D level) ranges from a negotiated payer cost of $85 to potential patient out-of-pocket cost of more than $400.6

Insurance would cover the USPSTF-recommended testing (HIV and hepatitis C screening tests), which might incur only a patient co-pay, and cost the system about $65.

The USPSTF home page, found at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ includes recommendations that can be sorted for your patients. A web and mobile device application is also available through the website.

a USPSTF grade definitions:

A: There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. Offer service.

B: There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate, or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. Offer service.

C: There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. Offer service selectively.

D: There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. Don’t offer service.

I: Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mitchell Kaminski, MD, MBA, 901 Walnut Street, 10th Floor, Jefferson College of Population Health, Philadelphia, PA 19107; [email protected]

1. IHI. What is the Triple Aim? Accessed June 20, 2022. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/TripleAim/Pages/Overview.aspx#:~:text=It%20is%20IHI’s%20belief%20that,capita%20cost%20of%20health%20care

2. Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024-1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150

3. Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322:1501-1509. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.13978

4. Mafi JN, Russell K, Bortz BA, et al. Low-cost, high-volume health services contribute the most to unnecessary health spending. Health Aff. 2017;36:1701-1704. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0385

5. CDC. Strengthening clinical laboratories. 2018. Accessed June 2020, 2022. www.cdc.gov/csels/dls/strengthening-clinical-labs.html

6. Vuong KT. How much do lab tests cost without insurance in 2022? Accessed May 11, 2022. www.talktomira.com/post/how-much-do-lab-test-cost-without-insurance

7. Choosing Wisely: Promoting conversations between providers and patients. Accessed June 20, 2022. www.choosingwisely.org

8. Morgan S, van Driel M, Coleman J, et al. Rational test ordering in family medicine. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:535-537.

9. US Preventive Services Taskforce. Screening for glaucoma and impaired vision. Accessed June 20, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf

10. Arnold MJ, O’Malley PG, Downs JR. Key recommendations on managing dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction: stopping where the evidence does. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103:455-458.

11. Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Reconsidering prostate cancer mortality—the future of PSA screening. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1557-1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms1914228

12. American Society for Microbiology. Why pretest and posttest probability matter in the time of COVID-19. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://asm.org/Articles/2020/June/Why-Pretest-and-Posttest-Probability-Matter-in-the

13. Slater CA, Davis RB, Shmerling RH. Antinuclear antibody testing. A study of clinical utility. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1421-1425.

14. Aragon G, Younossi ZM. When and how to evaluate mildly elevated liver enzymes in apparently healthy patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77:195-204. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09064

15. Ismail OZ, Bhayana V. Lipase or amylase for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis? Clin Biochem. 2017;50:1275-1280. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.07.003.

16. Gottheil S, Khemani E, Copley K, et al. Reducing inappropriate ESR testing with computerized clinical decision support. BMJ Quality Improvement Reports, 2016;5:u211376.w4582. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u211376.w4582

17. Schneider C, Feller M, Bauer DC, et al. Initial evaluation of thyroid dysfunction - are simultaneous TSH and fT4 tests necessary? PloS One. 2018;13:e0196631–e0196631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196631

18. Williams T, Mortada R, Porter S. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:106-113.

19. Eaton KP, Levy K, Soong C et.al. Evidence-Based Guidelines to Eliminate Repetitive Laboratory Testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1833-1839. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5152

20. ADA. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:S73-S84. doi: 10.2337/dc21-S006

21. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/ AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082-e1143. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

22. Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334-1357. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026.

23. Benarroch-Gampel J, Sheffield KM, Duncan CB, et al. Preoperative laboratory testing in patients undergoing elective, low-risk ambulatory surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;256:518-528. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318265bcdb

24. ASA. ASA physical status classification system. Accessed June 22,2022. www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/asa-physical-status-classification-system

25. NLM. Preoperative tests (update): routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. Accessed June 22, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK367919/

26. ASA. American Society of Anesthesiologists releases list of commonly used tests and treatments to question-AS PART OF CHOOSING WISELY® CAMPAIGN. Accessed June 22, 2022. www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2013/10/choosing-wisely

27. Keay L, Lindsley K, Tielsch J, et al. Routine preoperative medical testing for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD007293. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007293.pub4

28. Chen CL, Clay TH, McLeod S, et al. A revised estimate of costs associated with routine preoperative testing in Medicare cataract patients with a procedure-specific indicator. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:231-238. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.6372

29. USPSTF. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: screening. Accessed May 16, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-screening

30. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed June 20, 2022. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

CASE

A 35-year-old man arrives for an annual wellness visit with no specific complaints and no significant personal or family history. His normal exam includes a blood pressure of 110/74 mm Hg and a body mass index (BMI) of 23.6. You order “routine labs” for prevention, which include a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), fasting lipid profile, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and 25(OH) vitamin D tests. Are you practicing value-based laboratory testing?

The answer to this question appears in the Case discussion at the end of the article.

Value-based care, including care provided through laboratory testing, can achieve the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim of improving population health, improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction), and reducing cost: Value = (Quality x Patient experience) / Cost.1

As quality and patient experience rise and cost falls, the value of care increases. Unnecessary lab testing, however, can negatively impact this equation:

- Error introduced by unnecessary testing can adversely affect quality.

- Patients experience inconvenience and sometimes cascades of testing, in addition to financial responsibility, from unnecessary testing.

- Low-value testing also contributes to work burden and provider burnout by requiring additional review and follow-up.

Rising health care costs are approaching 18% of the US gross domestic product, driven in large part by a wasteful and inefficient care delivery system.2 One review of “waste domains” identified by the Institute of Medicine estimates that approximately one-quarter of health care costs represent waste, including overtreatment, breakdowns of care coordination, and pricing that fails to correlate to the level of care received.3 High-volume, low-cost testing contributes more to total cost than low-volume, high-cost tests.4

Provider and system factors that contribute to ongoing waste

A lack of awareness of waste and how to reduce it contribute to the problem, as does an underappreciation of the harmful effects caused by incidental abnormal results.

Provider intolerance of diagnostic uncertainty often leads to ordering even more tests.

Continue to: Also, a hope of avoiding...

Also, a hope of avoiding missed diagnoses and potential lawsuits leads to defensive practice and more testing. In addition, patients and family members can exert pressure based on a belief that more testing represents better care. Of course, financial revenues from testing may come into play, with few disincentives to forgo testing. Something that also comes into play is that evidence-based guidance on cost-effective laboratory testing may be lacking, or there may be a lack of knowledge on how to access existing evidence.

Automated systems can facilitate wasteful laboratory testing, and the heavy testing practices of hospitals and specialists may be inappropriately applied to outpatient primary care.

Factors affecting the cost of laboratory testing

Laboratory test results drive 70% of today’s medical decisions.5 Negotiated insurance payment for tests is usually much less than the direct out-of-pocket costs charged to the patient. Without insurance, lab tests can cost patients between $100 and $1000.6 If multiple tests are ordered, the costs could likely be many thousands of dollars.

Actual costs typically vary by the testing facility, the patient’s health plan, and location in the United States; hospital-based testing tends to be the most expensive. Insurers will pay for lab tests with appropriate indications that are covered in the contract with the provider.6

Choosing Wisely initiative weighs in on lab testing

Choosing Wisely, a prominent initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, promotes appropriate resource utilization through educational campaigns that detail how to avoid unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures.7 Recommendations are based largely on specialty society consensus and disease-oriented evidence. Choosing Wisely recommendations advise against the following7:

- performing laboratory blood testing unless clinically indicated or necessary for diagnosis or management, in order to avoid iatrogenic anemia. (American Academy of Family Physicians; Society for the Advancement of Patient Blood Management)

- requesting just a serum creatinine to test adult patients with diabetes and/or hypertension for chronic kidney disease. Use the kidney profile: serum creatinine with estimated glomerular filtration rate and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio. (American Society for Clinical Pathology)

- routinely screening for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen test. It should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making with the patient. (American Academy of Family Physicians; American Urological Association)

- screening for genital herpes simplex virus infectionFrutiger LT Std in asymptomatic adults, including pregnant women. (American Academy of Family Physicians)

- performing preoperative medical tests for eye surgery unless there are specific medical indications. (American Academy of Ophthalmology)

Sequential steps to takefor value-based lab ordering

Ask the question: “How will ordering this specific test change the management of my patient?” From there, take sequential steps using sound, evidence-based pathways. Morgan and colleagues8 outline the following practical approaches to rational test ordering:

- Perform a thorough clinical assessment.

- Consider the probability and implications of a positive test result.

- Practice patient-centered communication: address the patient’s concerns and discuss the risks and benefits of tests and how they will influence management.

- Follow clinical guidelines when available.

- Avoid ordering tests to reassure the patient; unnecessary tests with insignificant results do little to reduce patient anxieties.

- Avoid letting uncertainty drive unnecessary testing. Watchful waiting can allow time for the illness to resolve or declare itself.

Let’s consider this approach in the context of 4 areas: preventive care, diagnostic evaluation, ongoing management of chronic conditions, and preoperative testing.

Continue to: Preventive guidance from the USPSTF

Preventive guidance from the USPSTF

An independent volunteer panel of 16 national experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine develop recommendations for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).9 These guidelines are based on evidence and are updated as new evidence surfaces. Thirteen recommendations, some of which advise avoiding preventive procedures that could cause harm to patients, cover laboratory tests used in screening for conditions such as hyperlipidemia10 and prostate cancer.11 We review the ones pertinent to our patient later at the end of the Case.

While the target audience for USPSTF recommendations is clinicians who provide preventive care, the recommendations are widely followed by policymakers, managed care organizations, public and private payers, quality improvement organizations, research institutions, and patients.

Take a critical look at how you approach the diagnostic evaluation

To reduce unnecessary testing in the diagnostic evaluation of patients, first consider pretest probability, test sensitivity and specificity, narrowly out-of-range tests, habitually paired tests, and repetitive laboratory testing.

Pretest probability, and test sensitivity and specificity. Pretest probability is the estimated chance that the patient has the disease before the test result is known. In a patient with low pretest probability of a disease, the ability to conclusively arrive at the diagnosis with one positive result is limited. Similarly, for tests in patients with high pretest probability of disease, a negative test cannot be used to firmly rule out a diagnosis.12

Reliability also depends on test sensitivity (the proportion of true positive results) and specificity (the proportion of true negative results). A test with high sensitivity but low specificity will generate more false-positive results, with potential harm to patients who do not have a disease.

The pretest probability along with test sensitivity and specificity help a clinician to interpret a test result, and even decide whether to order the test at all. For example, the anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 86%13; it will always be positive in a patient with SLE. But when applied to individuals with low likelihood of SLE, false-positives are more common; the ANA is falsely positive in up to 14% of healthy individuals, depending on the population studied.13

Ordering a test may be unnecessary if the results will not change the treatment plan. For example, in a female patient with classic symptoms of an uncomplicated urinary tract infection, a urine culture and even a urinalysis may not change treatment.

Continue to: Narrowly out-of-range tests

Narrowly out-of-range tests. Test results that fall just outside the “normal” range may be of questionable significance. When an asymptomatic patient has mildly elevated liver enzymes, should additional tests be ordered to avoid missing a treatable disorder? In these scenarios, a history, including possible contributing factors such as alcohol or substance misuse, must be paired with the clinical presentation to assess pre-test probability of a particular condition.14 Repeating a narrowly out-of-range test is an option in patients when follow-up is possible. Alternatively, you could pursue watchful waiting and monitor a minor abnormality over time while being vigilant for clinical changes. This whole-patient approach will guide the decision of whether to order additional testing.

Habitually paired tests. Reflexively ordering tests together often contributes to unnecessary testing. Examples of commonly paired tests are serum lipase with amylase, C-reactive protein (CRP) with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and TSH with free T4 to monitor patients with treated hypothyroidism. These tests add minimal value together and can be decoupled.15-17 Evidence supports ordering serum lipase alone, CRP instead of ESR, and TSH alone for monitoring thyroid status.

Some commonly paired tests may not even be necessary for diagnosis. The well-established Rotterdam Criteria for diagnosing polycystic ovary syndrome specify clinical features and ovarian ultrasound for diagnosis.18 They do not require measurement of commonly ordered follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone for diagnosis.

Serial rather than parallel testing, a “2-step approach,” is a strategy made easier with the advent of the electronic medical record (EMR) and computerized lab systems.8 These records and lab systems allow providers to order reflex tests, and to add on additional tests, if necessary, to an existing blood specimen.

Repetitive laboratory testing. Repetitive inpatient laboratory testing in patients who are clinically stable is wasteful and potentially harmful. Interventions involving physician education alone show mixed results, but combining education with clinician audit and feedback, along with EMR-enabled restrictive ordering, have resulted in significant and sustained reductions in repetitive laboratory testing.19

Continue to: Ongoing management of chronic conditions

Ongoing management of chronic conditions

Evidence-based guidelines support choices of tests and testing intervals for ongoing management of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Diabetes. Guidelines also define quality standards that are applied to value-based contracts. For example, the American Diabetes Association recommends assessing A1C every 6 months in patients whose type 2 diabetes is under stable control.20

Hyperlipidemia. For patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia, 2018 clinical practice guidelines published by multiple specialty societies recommend assessing adherence and response to lifestyle changes and LDL-C–lowering medications with repeat lipid measurement 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation or dose adjustment, repeated every 3 to 12 months as needed.21

Hypertension. With a new diagnosis of hypertension, guidelines advise an initial assessment for comorbidities and end-organ damage with an electrocardiogram, urinalysis, glucose level, blood count, electrolytes, creatinine, calcium, lipids, and urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. For ongoing monitoring, guidelines recommend assessment for end-organ damage through regular measurements of creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, and urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio. Initiation and alteration of medications should prompt appropriate additional lab follow-up—eg, a measurement of serum potassium after starting a diuretic.22

Preoperative testing

Preoperative testing is overused in low-risk, ambulatory surgery. And testing, even with abnormal results, does not affect postoperative outcomes.23

Continue to: The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System, which has been in use for more than 60 years, considers the patient’s physical status (ASA grades I-VI),24 and when paired with surgery grades of minor, intermediate, and major/complex, can help assess preoperative risk and guide preoperative testing (TABLE).24-26

Preoperative medical testing did not reduce the risk of medical adverse events during or after cataract surgery when compared with selective or no testing.27 Unnecessary preoperative testing can lead to a nonproductive cascade of additional investigations. In a 2018 study of Medicare beneficiaries, unnecessary routine preoperative testing and testing sequelae for cataract surgery was calculated to cost Medicare up to $45.4 million annually.28

CASE

You would not be practicing value-based laboratory testing, according to the USPSTF, if you ordered a CMP, fasting lipid profile, and TSH and 25(OH) vitamin D tests for this healthy 35-year-old man whose family history, blood pressure, and BMI do not put him at elevated risk. Universal lipid screening (Grade Ba) is recommended for all adults ages 40 to 75. Thyroid screening tests and measurement of 25(OH) vitamin D level (I statementsa) are not recommended. The USPSTF has not evaluated chemistry panels for screening.

The USPSTF would recommend the following actions for this patient:

- Screen for HIV (ages 15 to 65 years; and younger or older if patient is at risk). (A recommendationa,29)

- Screen for hepatitis C virus (in those ages 18 to 79). (B recommendation30)

The following USPSTF recommendations might have come into play if this patient had certain risk factors, or if the patient had been a woman:

- Screen for diabetes if the patient is overweight or obese (B recommendation).

- Screen for hepatitis B in adults at risk (B recommendation).

- Screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia in women at risk (B recommendation). Such screening has an “I”statement for screening men at risk.

Continue to: As noted, costs of laboratory...

As noted, costs of laboratory testing vary widely, depending upon what tests are ordered, what type of insurance the patient has, and which tests the patient’s insurance covers. Who performs the testing also factors into the cost. Payers negotiate reduced fees for commercial lab testing, but potential out-of-pocket costs to patients are much higher.

For our healthy 35-year-old man, the cost of the initially proposed testing (CMP, lipid panel, TSH, and 25[OH] vitamin D level) ranges from a negotiated payer cost of $85 to potential patient out-of-pocket cost of more than $400.6

Insurance would cover the USPSTF-recommended testing (HIV and hepatitis C screening tests), which might incur only a patient co-pay, and cost the system about $65.

The USPSTF home page, found at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ includes recommendations that can be sorted for your patients. A web and mobile device application is also available through the website.

a USPSTF grade definitions:

A: There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. Offer service.

B: There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate, or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. Offer service.

C: There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. Offer service selectively.

D: There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. Don’t offer service.

I: Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mitchell Kaminski, MD, MBA, 901 Walnut Street, 10th Floor, Jefferson College of Population Health, Philadelphia, PA 19107; [email protected]

CASE

A 35-year-old man arrives for an annual wellness visit with no specific complaints and no significant personal or family history. His normal exam includes a blood pressure of 110/74 mm Hg and a body mass index (BMI) of 23.6. You order “routine labs” for prevention, which include a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), fasting lipid profile, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and 25(OH) vitamin D tests. Are you practicing value-based laboratory testing?

The answer to this question appears in the Case discussion at the end of the article.

Value-based care, including care provided through laboratory testing, can achieve the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim of improving population health, improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction), and reducing cost: Value = (Quality x Patient experience) / Cost.1

As quality and patient experience rise and cost falls, the value of care increases. Unnecessary lab testing, however, can negatively impact this equation:

- Error introduced by unnecessary testing can adversely affect quality.

- Patients experience inconvenience and sometimes cascades of testing, in addition to financial responsibility, from unnecessary testing.

- Low-value testing also contributes to work burden and provider burnout by requiring additional review and follow-up.

Rising health care costs are approaching 18% of the US gross domestic product, driven in large part by a wasteful and inefficient care delivery system.2 One review of “waste domains” identified by the Institute of Medicine estimates that approximately one-quarter of health care costs represent waste, including overtreatment, breakdowns of care coordination, and pricing that fails to correlate to the level of care received.3 High-volume, low-cost testing contributes more to total cost than low-volume, high-cost tests.4

Provider and system factors that contribute to ongoing waste

A lack of awareness of waste and how to reduce it contribute to the problem, as does an underappreciation of the harmful effects caused by incidental abnormal results.

Provider intolerance of diagnostic uncertainty often leads to ordering even more tests.

Continue to: Also, a hope of avoiding...

Also, a hope of avoiding missed diagnoses and potential lawsuits leads to defensive practice and more testing. In addition, patients and family members can exert pressure based on a belief that more testing represents better care. Of course, financial revenues from testing may come into play, with few disincentives to forgo testing. Something that also comes into play is that evidence-based guidance on cost-effective laboratory testing may be lacking, or there may be a lack of knowledge on how to access existing evidence.

Automated systems can facilitate wasteful laboratory testing, and the heavy testing practices of hospitals and specialists may be inappropriately applied to outpatient primary care.

Factors affecting the cost of laboratory testing

Laboratory test results drive 70% of today’s medical decisions.5 Negotiated insurance payment for tests is usually much less than the direct out-of-pocket costs charged to the patient. Without insurance, lab tests can cost patients between $100 and $1000.6 If multiple tests are ordered, the costs could likely be many thousands of dollars.

Actual costs typically vary by the testing facility, the patient’s health plan, and location in the United States; hospital-based testing tends to be the most expensive. Insurers will pay for lab tests with appropriate indications that are covered in the contract with the provider.6

Choosing Wisely initiative weighs in on lab testing

Choosing Wisely, a prominent initiative of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, promotes appropriate resource utilization through educational campaigns that detail how to avoid unnecessary medical tests, treatments, and procedures.7 Recommendations are based largely on specialty society consensus and disease-oriented evidence. Choosing Wisely recommendations advise against the following7:

- performing laboratory blood testing unless clinically indicated or necessary for diagnosis or management, in order to avoid iatrogenic anemia. (American Academy of Family Physicians; Society for the Advancement of Patient Blood Management)

- requesting just a serum creatinine to test adult patients with diabetes and/or hypertension for chronic kidney disease. Use the kidney profile: serum creatinine with estimated glomerular filtration rate and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio. (American Society for Clinical Pathology)

- routinely screening for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen test. It should be performed only after engaging in shared decision-making with the patient. (American Academy of Family Physicians; American Urological Association)

- screening for genital herpes simplex virus infectionFrutiger LT Std in asymptomatic adults, including pregnant women. (American Academy of Family Physicians)

- performing preoperative medical tests for eye surgery unless there are specific medical indications. (American Academy of Ophthalmology)

Sequential steps to takefor value-based lab ordering

Ask the question: “How will ordering this specific test change the management of my patient?” From there, take sequential steps using sound, evidence-based pathways. Morgan and colleagues8 outline the following practical approaches to rational test ordering:

- Perform a thorough clinical assessment.

- Consider the probability and implications of a positive test result.

- Practice patient-centered communication: address the patient’s concerns and discuss the risks and benefits of tests and how they will influence management.

- Follow clinical guidelines when available.

- Avoid ordering tests to reassure the patient; unnecessary tests with insignificant results do little to reduce patient anxieties.

- Avoid letting uncertainty drive unnecessary testing. Watchful waiting can allow time for the illness to resolve or declare itself.

Let’s consider this approach in the context of 4 areas: preventive care, diagnostic evaluation, ongoing management of chronic conditions, and preoperative testing.

Continue to: Preventive guidance from the USPSTF

Preventive guidance from the USPSTF

An independent volunteer panel of 16 national experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine develop recommendations for the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).9 These guidelines are based on evidence and are updated as new evidence surfaces. Thirteen recommendations, some of which advise avoiding preventive procedures that could cause harm to patients, cover laboratory tests used in screening for conditions such as hyperlipidemia10 and prostate cancer.11 We review the ones pertinent to our patient later at the end of the Case.

While the target audience for USPSTF recommendations is clinicians who provide preventive care, the recommendations are widely followed by policymakers, managed care organizations, public and private payers, quality improvement organizations, research institutions, and patients.

Take a critical look at how you approach the diagnostic evaluation

To reduce unnecessary testing in the diagnostic evaluation of patients, first consider pretest probability, test sensitivity and specificity, narrowly out-of-range tests, habitually paired tests, and repetitive laboratory testing.

Pretest probability, and test sensitivity and specificity. Pretest probability is the estimated chance that the patient has the disease before the test result is known. In a patient with low pretest probability of a disease, the ability to conclusively arrive at the diagnosis with one positive result is limited. Similarly, for tests in patients with high pretest probability of disease, a negative test cannot be used to firmly rule out a diagnosis.12

Reliability also depends on test sensitivity (the proportion of true positive results) and specificity (the proportion of true negative results). A test with high sensitivity but low specificity will generate more false-positive results, with potential harm to patients who do not have a disease.

The pretest probability along with test sensitivity and specificity help a clinician to interpret a test result, and even decide whether to order the test at all. For example, the anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 86%13; it will always be positive in a patient with SLE. But when applied to individuals with low likelihood of SLE, false-positives are more common; the ANA is falsely positive in up to 14% of healthy individuals, depending on the population studied.13

Ordering a test may be unnecessary if the results will not change the treatment plan. For example, in a female patient with classic symptoms of an uncomplicated urinary tract infection, a urine culture and even a urinalysis may not change treatment.

Continue to: Narrowly out-of-range tests

Narrowly out-of-range tests. Test results that fall just outside the “normal” range may be of questionable significance. When an asymptomatic patient has mildly elevated liver enzymes, should additional tests be ordered to avoid missing a treatable disorder? In these scenarios, a history, including possible contributing factors such as alcohol or substance misuse, must be paired with the clinical presentation to assess pre-test probability of a particular condition.14 Repeating a narrowly out-of-range test is an option in patients when follow-up is possible. Alternatively, you could pursue watchful waiting and monitor a minor abnormality over time while being vigilant for clinical changes. This whole-patient approach will guide the decision of whether to order additional testing.

Habitually paired tests. Reflexively ordering tests together often contributes to unnecessary testing. Examples of commonly paired tests are serum lipase with amylase, C-reactive protein (CRP) with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and TSH with free T4 to monitor patients with treated hypothyroidism. These tests add minimal value together and can be decoupled.15-17 Evidence supports ordering serum lipase alone, CRP instead of ESR, and TSH alone for monitoring thyroid status.

Some commonly paired tests may not even be necessary for diagnosis. The well-established Rotterdam Criteria for diagnosing polycystic ovary syndrome specify clinical features and ovarian ultrasound for diagnosis.18 They do not require measurement of commonly ordered follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone for diagnosis.

Serial rather than parallel testing, a “2-step approach,” is a strategy made easier with the advent of the electronic medical record (EMR) and computerized lab systems.8 These records and lab systems allow providers to order reflex tests, and to add on additional tests, if necessary, to an existing blood specimen.

Repetitive laboratory testing. Repetitive inpatient laboratory testing in patients who are clinically stable is wasteful and potentially harmful. Interventions involving physician education alone show mixed results, but combining education with clinician audit and feedback, along with EMR-enabled restrictive ordering, have resulted in significant and sustained reductions in repetitive laboratory testing.19

Continue to: Ongoing management of chronic conditions

Ongoing management of chronic conditions

Evidence-based guidelines support choices of tests and testing intervals for ongoing management of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Diabetes. Guidelines also define quality standards that are applied to value-based contracts. For example, the American Diabetes Association recommends assessing A1C every 6 months in patients whose type 2 diabetes is under stable control.20

Hyperlipidemia. For patients diagnosed with hyperlipidemia, 2018 clinical practice guidelines published by multiple specialty societies recommend assessing adherence and response to lifestyle changes and LDL-C–lowering medications with repeat lipid measurement 4 to 12 weeks after statin initiation or dose adjustment, repeated every 3 to 12 months as needed.21

Hypertension. With a new diagnosis of hypertension, guidelines advise an initial assessment for comorbidities and end-organ damage with an electrocardiogram, urinalysis, glucose level, blood count, electrolytes, creatinine, calcium, lipids, and urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. For ongoing monitoring, guidelines recommend assessment for end-organ damage through regular measurements of creatinine, glomerular filtration rate, and urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio. Initiation and alteration of medications should prompt appropriate additional lab follow-up—eg, a measurement of serum potassium after starting a diuretic.22

Preoperative testing

Preoperative testing is overused in low-risk, ambulatory surgery. And testing, even with abnormal results, does not affect postoperative outcomes.23

Continue to: The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System, which has been in use for more than 60 years, considers the patient’s physical status (ASA grades I-VI),24 and when paired with surgery grades of minor, intermediate, and major/complex, can help assess preoperative risk and guide preoperative testing (TABLE).24-26

Preoperative medical testing did not reduce the risk of medical adverse events during or after cataract surgery when compared with selective or no testing.27 Unnecessary preoperative testing can lead to a nonproductive cascade of additional investigations. In a 2018 study of Medicare beneficiaries, unnecessary routine preoperative testing and testing sequelae for cataract surgery was calculated to cost Medicare up to $45.4 million annually.28

CASE

You would not be practicing value-based laboratory testing, according to the USPSTF, if you ordered a CMP, fasting lipid profile, and TSH and 25(OH) vitamin D tests for this healthy 35-year-old man whose family history, blood pressure, and BMI do not put him at elevated risk. Universal lipid screening (Grade Ba) is recommended for all adults ages 40 to 75. Thyroid screening tests and measurement of 25(OH) vitamin D level (I statementsa) are not recommended. The USPSTF has not evaluated chemistry panels for screening.

The USPSTF would recommend the following actions for this patient:

- Screen for HIV (ages 15 to 65 years; and younger or older if patient is at risk). (A recommendationa,29)

- Screen for hepatitis C virus (in those ages 18 to 79). (B recommendation30)

The following USPSTF recommendations might have come into play if this patient had certain risk factors, or if the patient had been a woman:

- Screen for diabetes if the patient is overweight or obese (B recommendation).

- Screen for hepatitis B in adults at risk (B recommendation).

- Screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia in women at risk (B recommendation). Such screening has an “I”statement for screening men at risk.

Continue to: As noted, costs of laboratory...

As noted, costs of laboratory testing vary widely, depending upon what tests are ordered, what type of insurance the patient has, and which tests the patient’s insurance covers. Who performs the testing also factors into the cost. Payers negotiate reduced fees for commercial lab testing, but potential out-of-pocket costs to patients are much higher.

For our healthy 35-year-old man, the cost of the initially proposed testing (CMP, lipid panel, TSH, and 25[OH] vitamin D level) ranges from a negotiated payer cost of $85 to potential patient out-of-pocket cost of more than $400.6

Insurance would cover the USPSTF-recommended testing (HIV and hepatitis C screening tests), which might incur only a patient co-pay, and cost the system about $65.

The USPSTF home page, found at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ includes recommendations that can be sorted for your patients. A web and mobile device application is also available through the website.

a USPSTF grade definitions:

A: There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. Offer service.

B: There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate, or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. Offer service.

C: There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. Offer service selectively.

D: There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. Don’t offer service.

I: Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mitchell Kaminski, MD, MBA, 901 Walnut Street, 10th Floor, Jefferson College of Population Health, Philadelphia, PA 19107; [email protected]

1. IHI. What is the Triple Aim? Accessed June 20, 2022. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/TripleAim/Pages/Overview.aspx#:~:text=It%20is%20IHI’s%20belief%20that,capita%20cost%20of%20health%20care