User login

Reexamining the Role of Diet in Dermatology

Within the last decade, almost 3000 articles have been published on the role of diet in the prevention and management of dermatologic conditions. Patients are increasingly interested in—and employing—dietary modifications that may influence skin appearance and aid in the treatment of cutaneous disease.1 It is essential that dermatologists are familiar with existing evidence on the role of diet in dermatology to counsel patients appropriately. Herein, we discuss the compositions of several popular diets and their proposed utility for dermatologic purposes. We highlight the limited literature that exists surrounding this topic and emphasize the need for future, well-designed clinical trials that study the impact of diet on skin disease.

Ketogenic Diet

The ketogenic diet has a macronutrient profile composed of high fat, low to moderate protein, and very low carbohydrates. Nutritional ketosis occurs as the body begins to use free fatty acids (via beta oxidation) as the primary metabolite driving cellular metabolism. It has been suggested that the ketogenic diet may impart beneficial effects on skin disease; however, limited literature exists on the role of nutritional ketosis in the treatment of dermatologic conditions.

Mechanistically, the ketogenic diet decreases the secretion of insulin and insulinlike growth factor 1, resulting in a reduction of circulating androgens and increased activity of the retinoid X receptor.2 In acne vulgaris, it has been suggested that the ketogenic diet may be beneficial in decreasing androgen-induced sebum production and the overproliferation of keratinocytes.2-7 The ketogenic diet is one of the most rapidly effective dietary strategies for normalizing both insulin and androgens, thus it may theoretically be useful for other metabolic and hormone-dependent skin diseases, such as hidradenitis suppurativa.8,9

The cutaneous manifestations associated with chronic hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia are numerous and include acanthosis nigricans, acrochordons, diabetic dermopathy, scleredema diabeticorum, bullosis diabeticorum, keratosis pilaris, and generalized granuloma annulare. There also is an increased risk for bacterial and fungal skin infections associated with hyperglycemic states.10 The ketogenic diet is an effective nonpharmacologic tool for normalizing serum insulin and glucose levels in most patients and may have utility in the aforementioned conditions.11,12 In addition to improving insulin sensitivity, it has been used as a dietary strategy for weight loss.11-15 Because obesity and metabolic syndrome are highly correlated with common skin conditions such as psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and androgenetic alopecia, there may be a role for employing the ketogenic diet in these patient populations.16,17

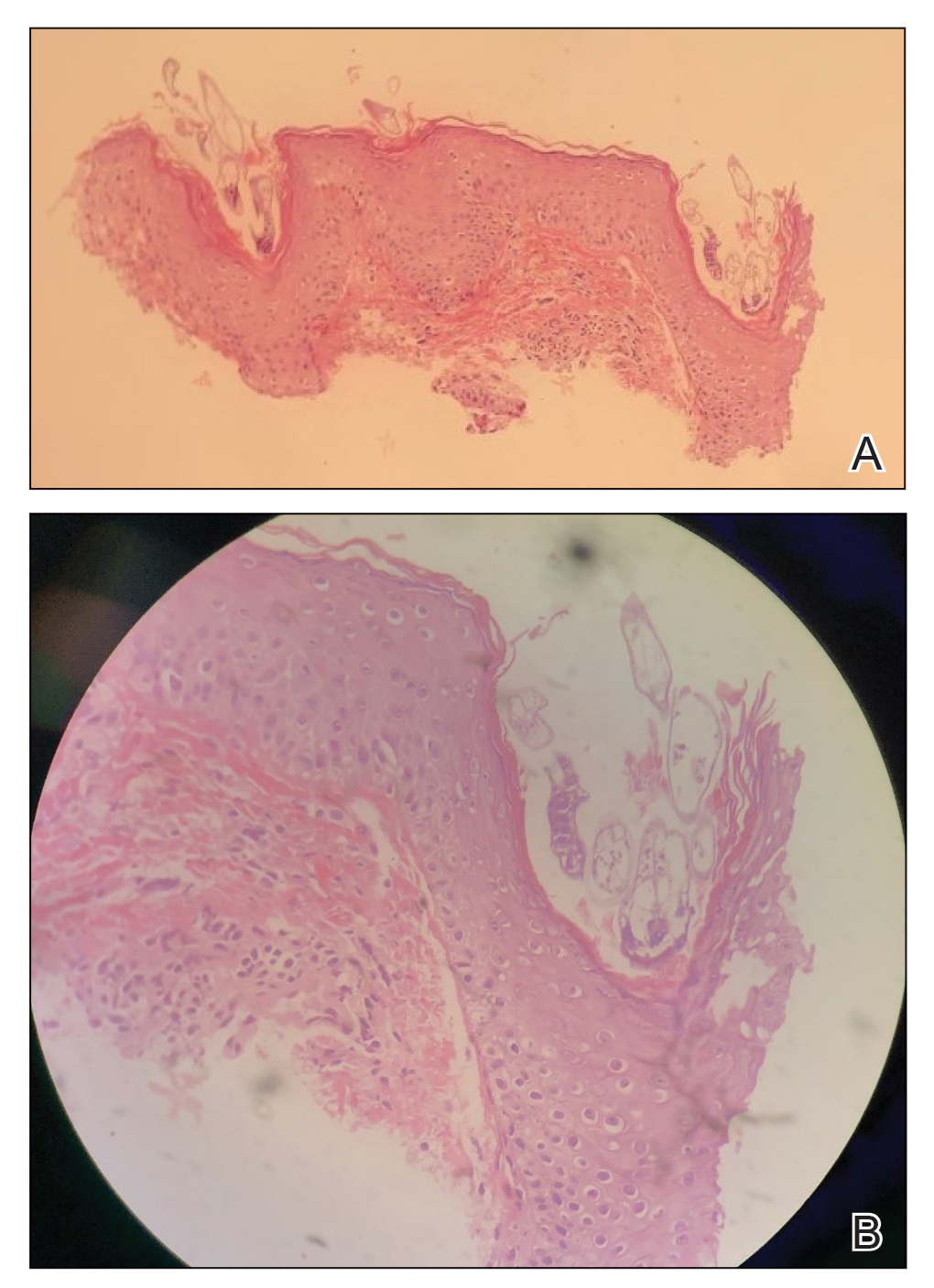

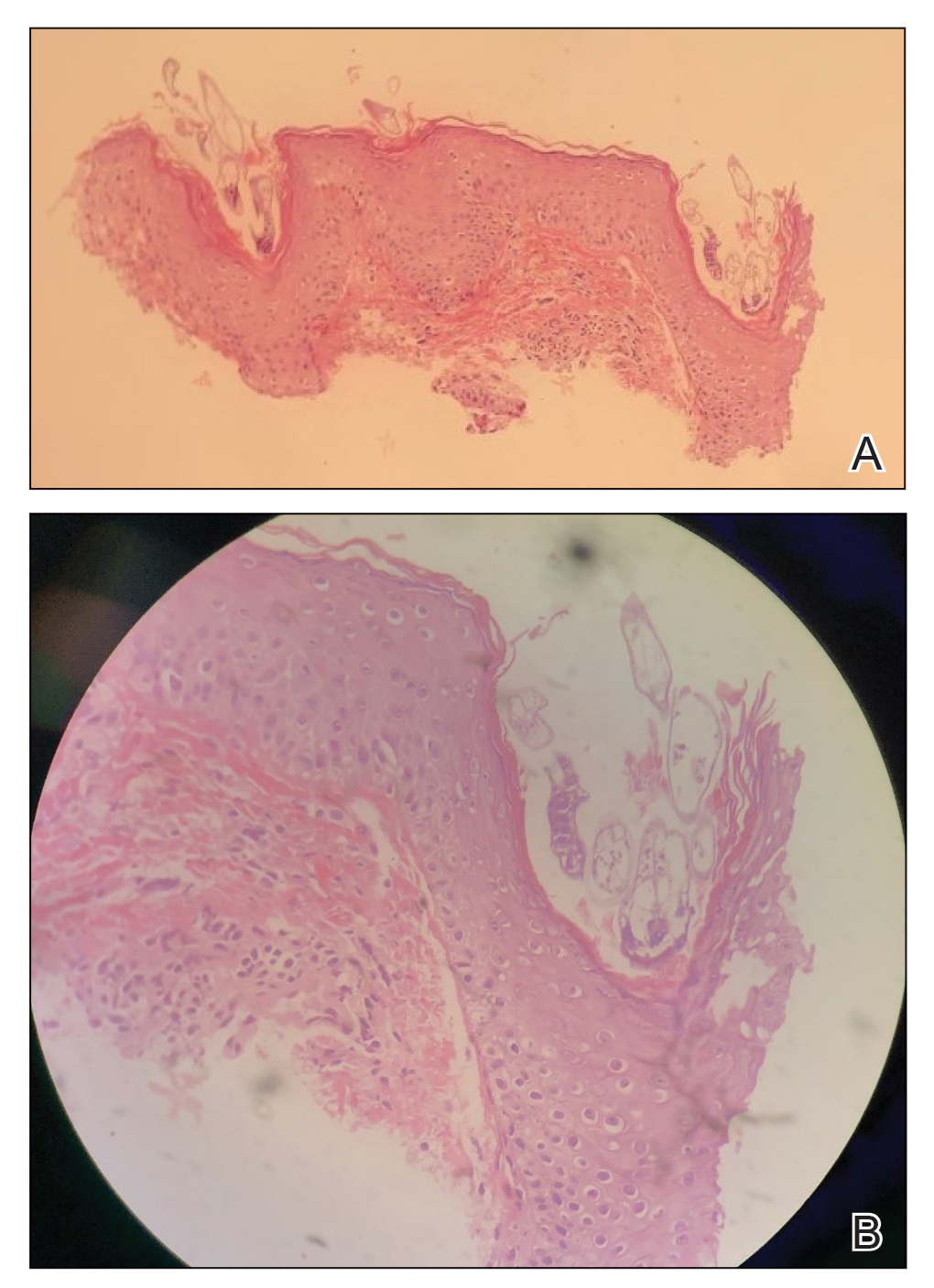

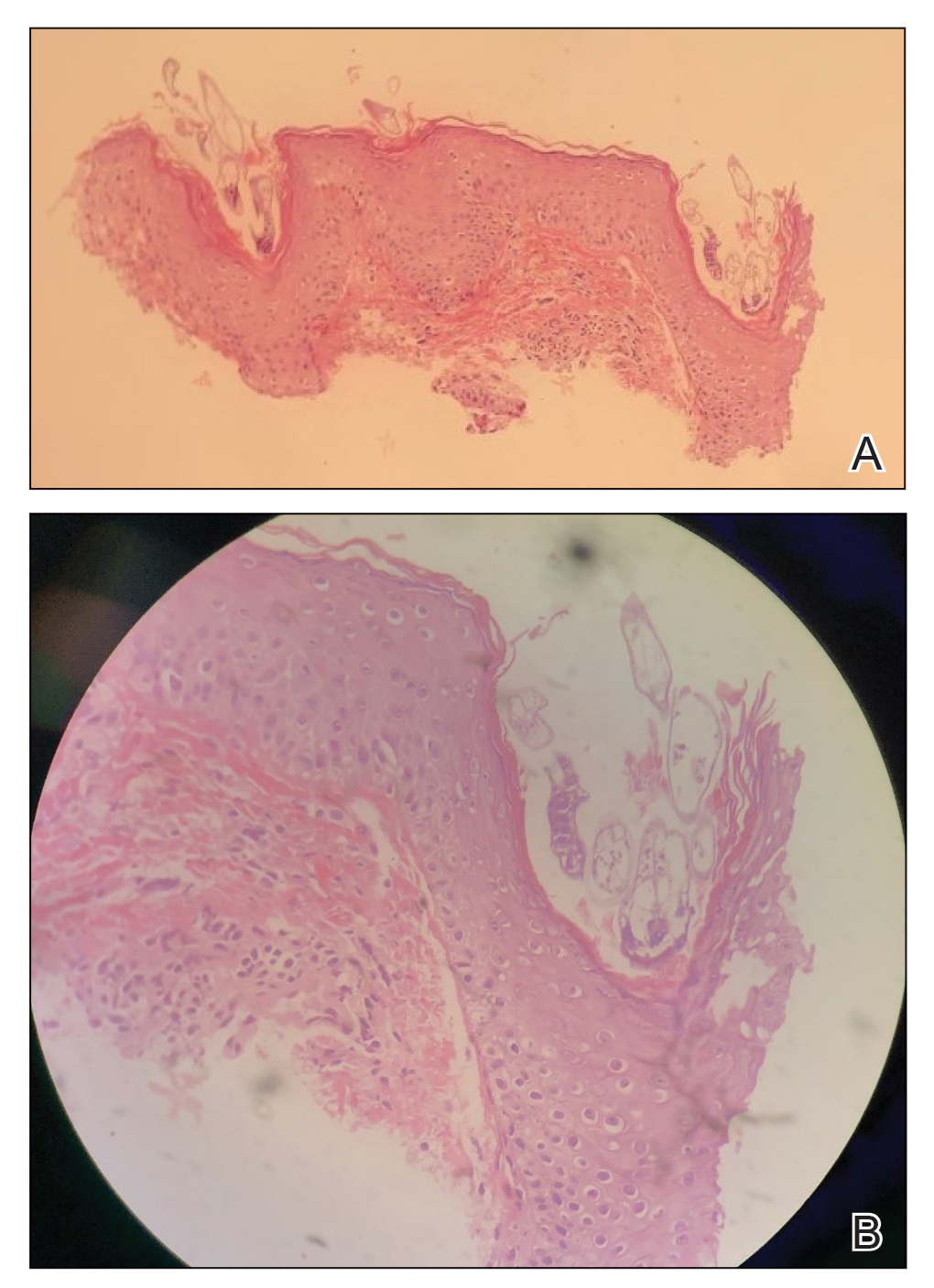

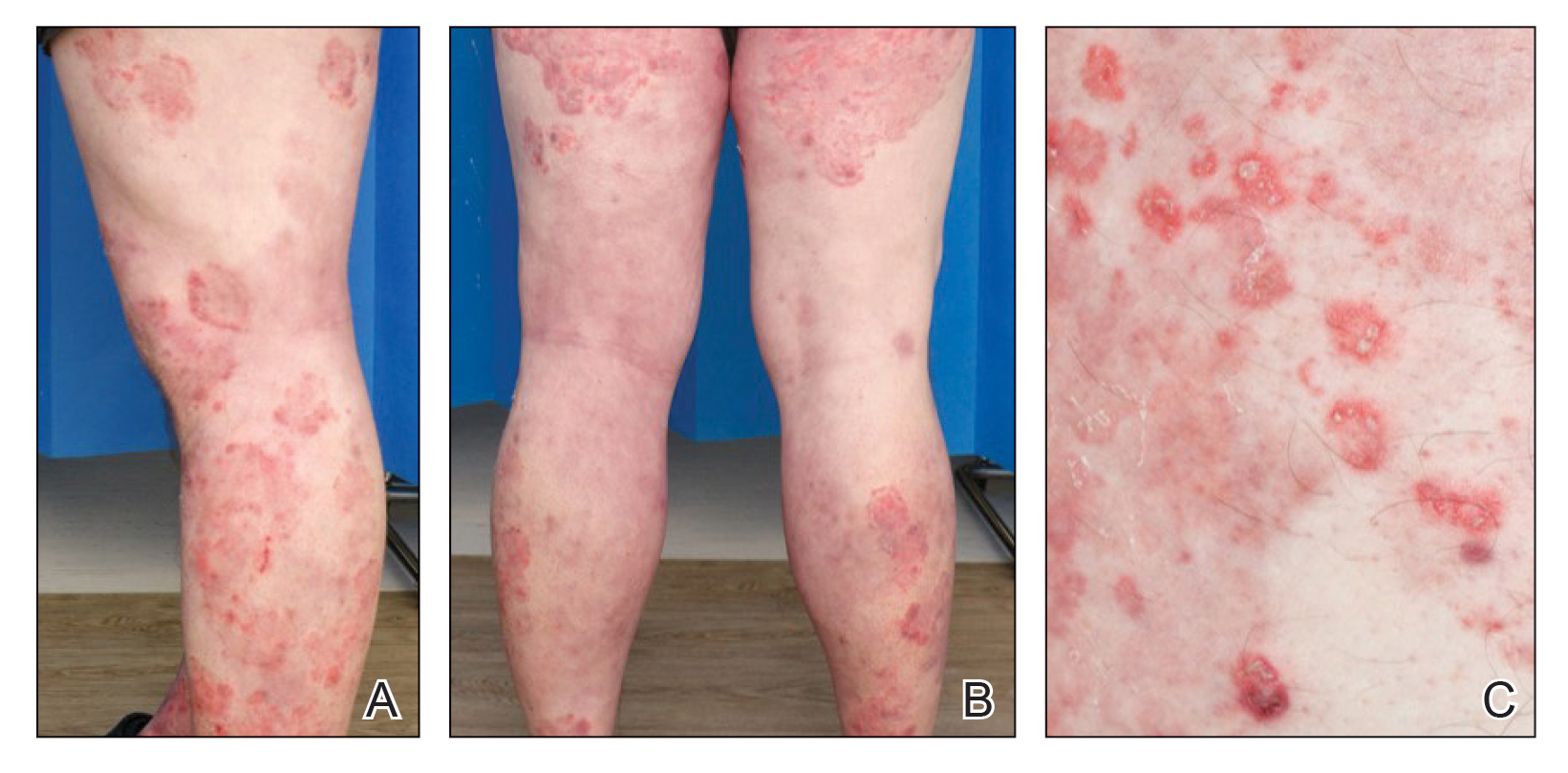

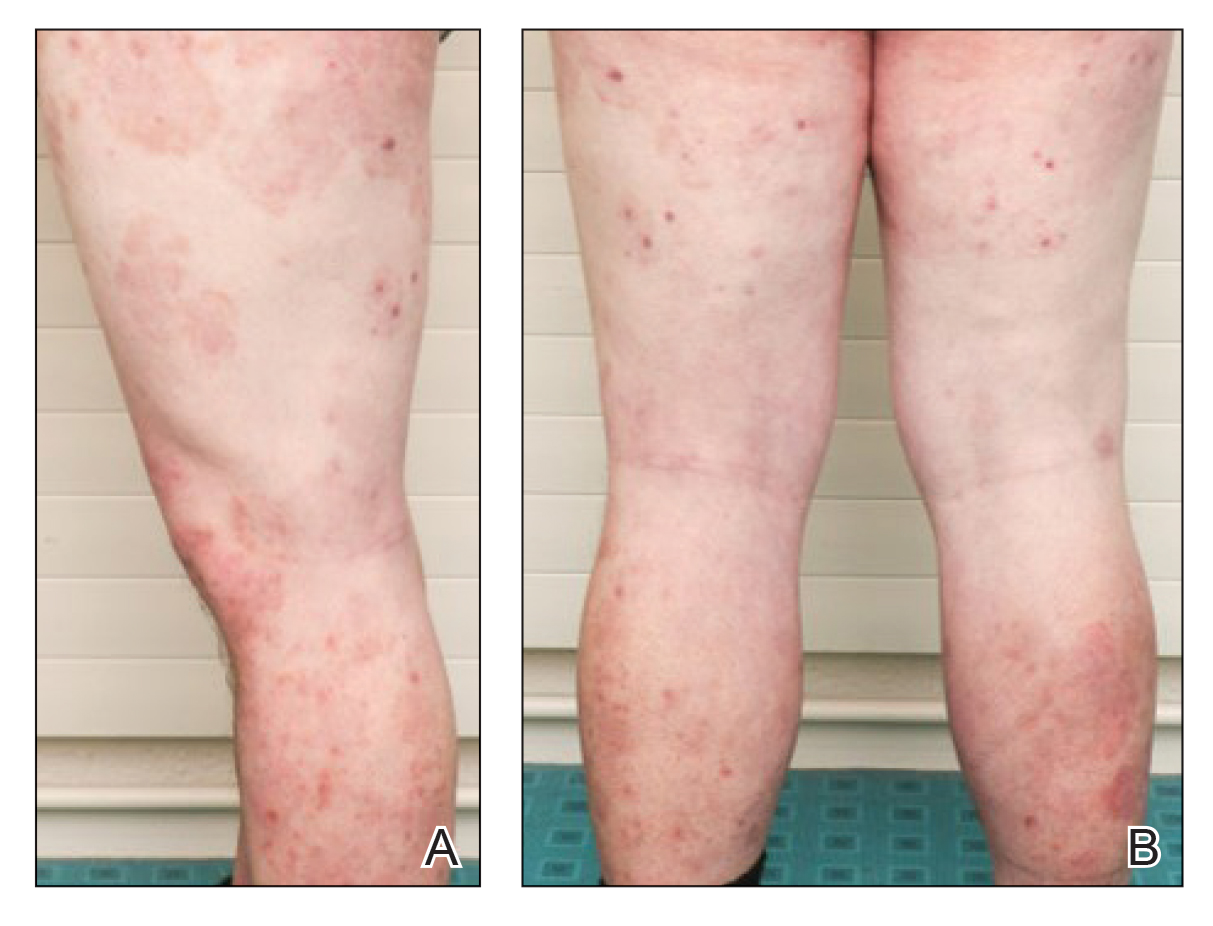

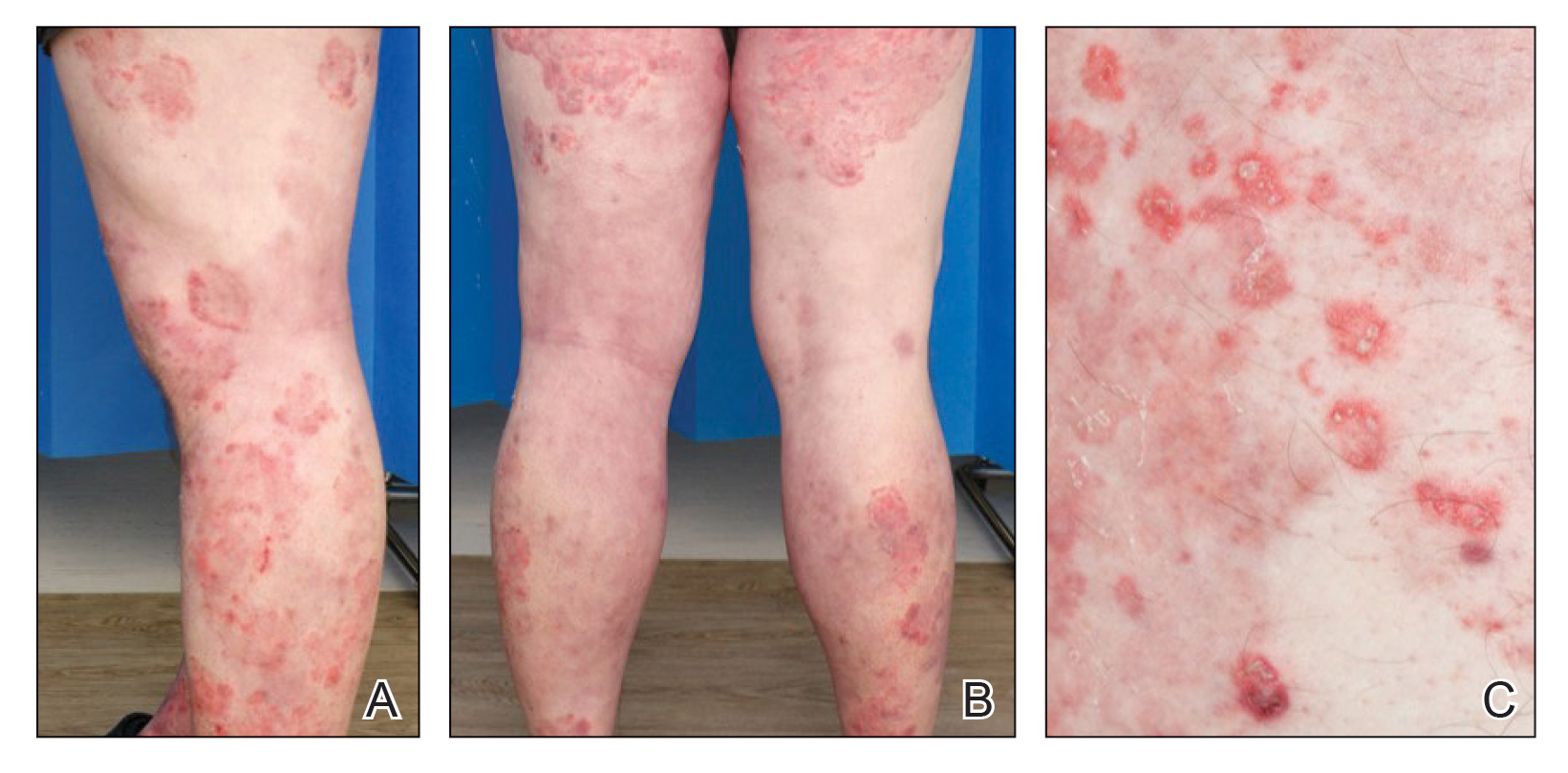

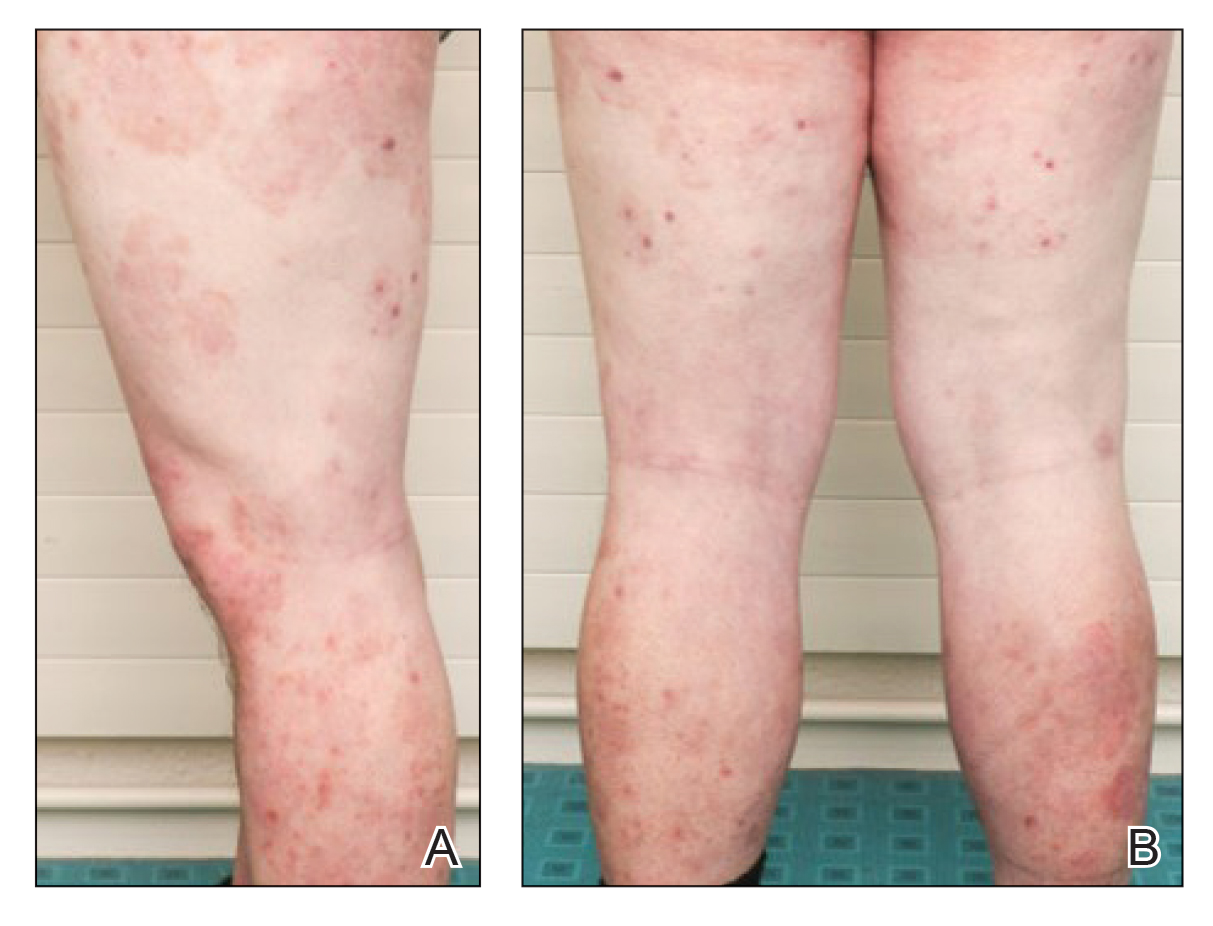

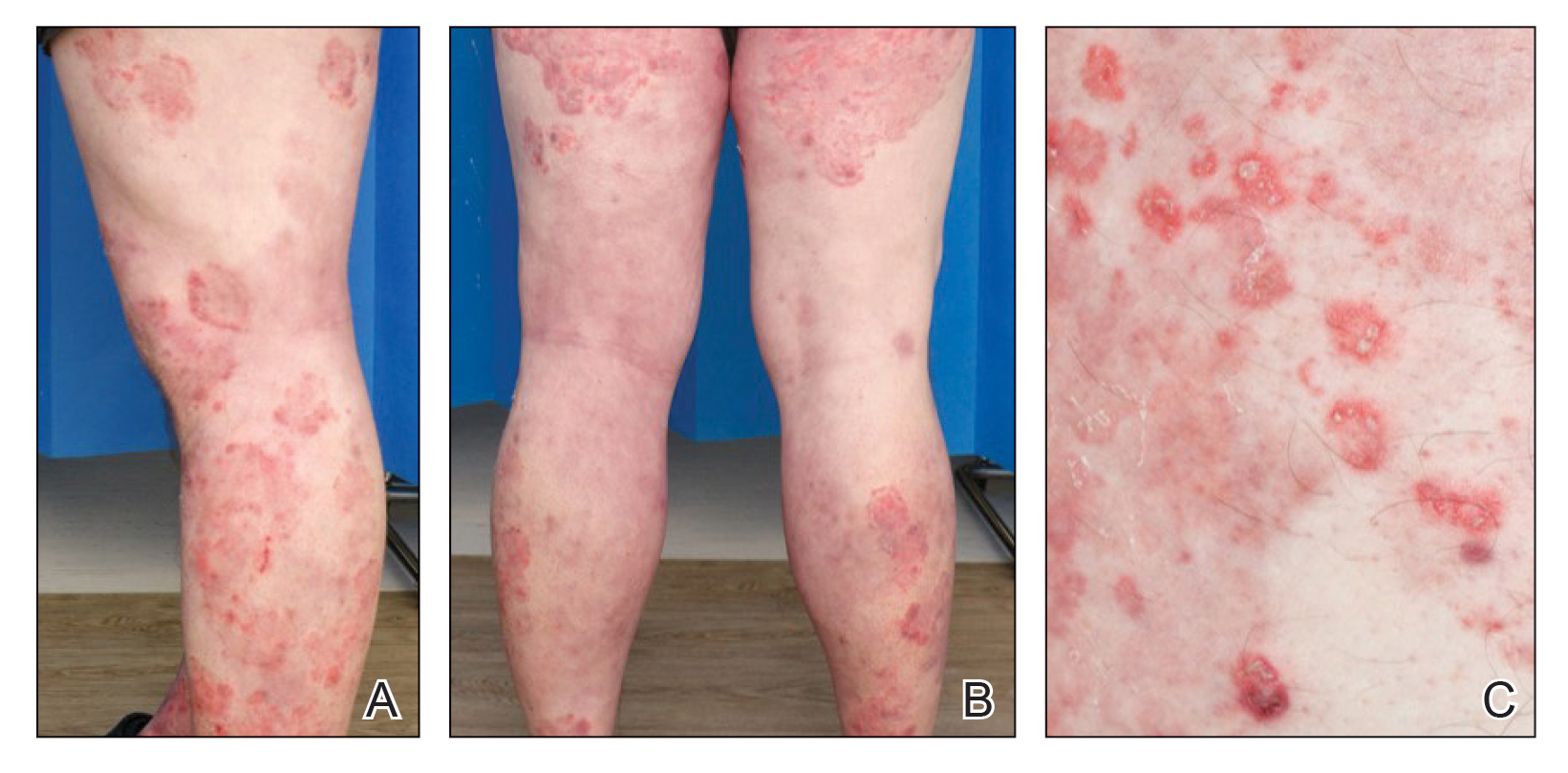

Although robust clinical studies on ketogenic diets in skin disease are lacking, a recent single-arm, open-label clinical trial observed benefit in all 37 drug-naïve, overweight patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who underwent a ketogenic weight loss protocol. Significant reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score and dermatology life quality index score were reported (P<.001).18 Another study of 30 patients with psoriasis found that a 4-week, low-calorie, ketogenic diet resulted in 50% improvement of PASI scores, 10% weight loss, and a reduction in the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-2.19 Despite these results, it is a challenge to tease out if the specific dietary intervention or its associated weight loss was the main driver in these reported improvements in skin disease.

There is mixed evidence on the anti-inflammatory nature of the ketogenic diet, likely due to wide variation in the composition of foods included in individual diets. In many instances, the ketogenic diet is thought to possess considerable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities. Ketones are known activators of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 pathway, which upregulates the production of glutathione, a major endogenous intracellular antioxidant.20 Additionally, dietary compounds from foods that are encouraged while on the ketogenic diet, such as sulforaphane from broccoli, also are independent activators of nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2.21 Ketones are efficiently utilized by mitochondria, which also may result in the decreased production of reactive oxygen species and lower oxidative stress.22 Moreover, the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate has demonstrated the ability to reduce proinflammatory IL-1β levels via suppression of nucleotide-binding domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activity.23,24 The activity of IL-1β is known to be elevated in many dermatologic conditions, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Schnitzler syndrome, hidradenitis suppurativa, Behçet disease, and other autoinflammatory syndromes.25 Ketones also have been shown to inhibit the nuclear factor–κB proinflammatory signaling pathway.22,26,27 Overexpression of IL-1β and aberrant activation of nuclear factor–κB are implicated in a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and oncologic cutaneous pathologies. The ketogenic diet may prove to be an effective adjunctive treatment for dermatologists to consider in select patient populations.23,24,28-30

For patients with keratinocyte carcinomas, the ketogenic diet may offer the aforementioned anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, as well as suppression of the mechanistic target of rapamycin, a major regulator of cell metabolism and proliferation.31,32 Inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamycin activity has been shown to slow tumor growth and reduce the development of squamous cell carcinoma.25,33,34 The ketogenic diet also may exploit the preferential utilization of glucose exhibited by many types of cancer cells, thereby “starving” the tumor of its primary fuel source.35,36 In vitro and animal studies in a variety of cancer types have demonstrated that a ketogenic metabolic state—achieved through the ketogenic diet or fasting—can sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapy and radiation while conferring a protective effect to normal cells.37-40 This recently described phenomenon is known as differential stress resistance, but it has not been studied in keratinocyte malignancies or melanoma to date. Importantly, some basal cell carcinomas and BRAF V600E–mutated melanomas have worsened while on the ketogenic diet, suggesting more data is needed before it can be recommended for all cancer patients.41,42 Furthermore, other skin conditions such as prurigo pigmentosa have been associated with initiation of the ketogenic diet.43

Low FODMAP Diet

Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed, osmotically active, and rapidly fermented by intestinal bacteria.44 The low FODMAP diet has been shown to be efficacious for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and some cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).44-49 A low FODMAP diet may have potential implications for several dermatologic conditions.

Rosacea has been associated with various gastrointestinal tract disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, SIBO, and IBD.50-54 A single study found that patients with rosacea had a 13-fold increased risk for SIBO.55,56 Treatment of 40 patients with SIBO using rifaximin resulted in complete resolution of rosacea in all patients, with no relapse after a 3-year follow-up period.55 Psoriasis also has been associated with SIBO and IBD.57,58 One small study found that eradication of SIBO in psoriatic patients resulted in improved PASI scores and colorimetric values.59

Although the long-term health consequences of the low FODMAP diet are unknown, further research on such dietary interventions for inflammatory skin conditions is warranted given the mounting evidence of a gut-skin connection and the role of the intestinal microbiome in skin health.50,51

Gluten-Free Diet

Gluten is a protein found in a variety of grains. Although the role of gluten in the pathogenesis of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis is indisputable, the deleterious effects of gluten outside of the context of these diseases remain controversial. There may be a compelling case for eliminating gluten in psoriasis patients with seropositivity for celiac disease. A recent systematic review found a 2.2-fold increased risk for celiac disease in psoriasis patients.60 Antigliadin antibody titers also were found to be positively correlated with psoriatic disease severity.61 In addition, one open-label study found a reduction in PASI scores in 73% of patients with antigliadin antibodies after 3 months on a gluten-free diet compared to those without antibodies; however, the study only included 22 patients.62 Several other small studies have yielded similar results63,64; however, antigliadin antibodies are neither the most sensitive nor specific markers of celiac disease, and additional testing should be completed in any patient who may carry this diagnosis. A survey study by the National Psoriasis Foundation found that the dietary change associated with the greatest skin improvement was removal of gluten and nightshade vegetables in approximately 50% of the 1200 psoriasis patients that responded.65 Case reports of various dermatologic conditions including sarcoidosis, vitiligo, alopecia areata, lichen planus, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and aphthous ulcerations have reportedly improved with a gluten-free diet; however, this should not be used as primary therapy in patients without celiac disease.66-71 Because gluten-free diets can be expensive and challenging to follow, a formal assessment for celiac disease should be considered before recommendation of this dietary intervention.

Low Histamine Diet

Histamine is a biogenic amine produced by the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine.72 It is found in several foods in varying amounts. Because bacteria can convert histidine into histamine, many fermented and aged foods such as kimchi, sauerkraut, cheese, and red wine contain high levels of histamine. Individuals who have decreased activity of diamine oxidase (DAO), an enzyme that degrades histamine, may be more susceptible to histamine intolerance.72 The symptoms of histamine intolerance are numerous and include gastrointestinal tract distress, rhinorrhea and nasal congestion, headache, urticaria, flushing, and pruritus. Histamine intolerance can mimic an IgE-mediated food allergy; however, allergy testing is negative in these patients. Unfortunately, there is no laboratory test for histamine intolerance; a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge is considered the gold-standard test.72

As it pertains to dermatology, a low histamine diet may play a role in the treatment of certain patients with atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria. One study reported that 17 of 54 (31.5%) atopic patients had higher basal levels of serum histamine compared to controls.73 Another study found that a histamine-free diet led to improvement in both histamine intolerance symptoms and atopic dermatitis disease severity (SCORing atopic dermatitis) in patients with low DAO activity.74 In chronic spontaneous urticaria, a recent systematic review found that in 223 patients placed on a low histamine diet for 3 to 4 weeks, 12% and 44% achieved complete and partial remission, respectively.75 Although treatment response based on a patient’s DAO activity level has not been correlated, a diet low in histamine may prove useful for patients with persistent atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria who have negative food allergy tests and report exacerbation of symptoms after ingestion of histamine-rich foods.76,77

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet has been touted as one of the healthiest diets to date, and large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated its effectiveness in weight loss, improving insulin sensitivity, and reducing inflammatory cytokine profiles.78,79 A major criticism of the Mediterranean diet is that it has considerable ambiguity and lacks a precise definition due to the variability of what is consumed in different Mediterranean regions. Generally, the diet emphasizes high consumption of colorful fruits and vegetables, aromatic herbs and spices, olive oil, nuts, and seafood, as well as modest amounts of dairy, eggs, and red meat.80 The anti-inflammatory effects of this diet largely have been attributed to its abundance of polyphenols, carotenoids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).80,81 Examples of polyphenols include resveratrol in red grapes, quercetin in apples and red onions, and curcumin in turmeric, while examples of carotenoids include lycopene in tomatoes and zeaxanthin in dark leafy greens. Oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid present in high concentrations in olive oil, while eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are omega-3 PUFAs predominantly found in fish.82

Unfortunately, rigorous clinical trials regarding the Mediterranean diet as it pertains to dermatology have not been undertaken. Numerous observational studies in patients with psoriasis have suggested that close adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with improvement in PASI scores.83-86 The National Psoriasis Foundation now recommends a trial of the Mediterranean diet in some patients with psoriasis, emphasizing increased dietary intake of olive oil, fish, and vegetables.87 Adherence to a Mediterranean diet also has been inversely correlated to the severity of acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa88,89; however, these studies failed to account for the multifactorial risk factors associated with these conditions. Mediterranean diets also may impart a chemopreventive effect, supported by a number of in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrating the inhibition and/or reversal of cutaneous DNA damage induced by UV radiation through supplementation with various phytonutrients and omega-3 PUFAs.81,90-92 Although small case-control studies have found a decreased risk of basal cell carcinoma in those who closely adhered to a Mediterranean diet, more rigorous clinical research is needed.93

Whole-Food, Plant-Based Diet

A whole-food, plant-based (WFPB) diet is another popular dietary approach that consists of eating fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and grains in their whole natural form.94 This diet discourages all animal products, including red meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs. It is similar to a vegan diet except that it eliminates all highly refined carbohydrates, vegetable oils, and other processed foods.94 Randomized clinical studies have demonstrated the WFPB diet to be effective in the treatment of obesity and metabolic syndrome.95,96

A WFPB diet has been shown to increase the antioxidant capacity of cells, lengthen telomeres, and reduce formation of advanced glycation end products.94,97,98 These benefits may help combat accelerated skin aging, including increased skin permeability, reduced elasticity and hydration, decreased angiogenesis, impaired immune function, and decreased vitamin D synthesis. Accelerated skin aging can result in delayed wound healing and susceptibility to skin tears and ecchymoses and also may promote the development of cutaneous malignancies.99 There remains a lack of clinical data studying a properly formulated WFPB diet in the dermatologic setting.

Paleolithic Diet

The paleolithic (Paleo) diet is an increasingly popular way of eating that attempts to mirror what our ancestors may have consumed between 10,000 and 2.5 million years ago.100 It is similar to the Mediterranean diet but excludes grains, dairy, legumes, and nightshade vegetables. It also calls for elimination of highly processed sugars and oils as well as chemical food additives and preservatives. There is a strict variation of the diet for individuals with autoimmune disease that also excludes eggs, nuts, and seeds, as these can be inflammatory or immunogenic in some patients.100-106 Other variations of the diet exist, including the ketogenic Paleo diet, pegan (Paleo vegan) diet, and lacto-Paleo diet.100 An often cited criticism of the Paleo diet is the low intake of calcium and risk for osteoporosis; however, consumption of calcium-rich foods or a calcium supplement can address this concern.107

Although small clinical studies have found the Paleo diet to be beneficial for various autoimmune diseases, clinical data evaluating the utility of the diet for cutaneous disease is lacking.108,109 Numerous randomized trials have demonstrated the Paleo diet to be effective for weight loss and improving insulin sensitivity and lipid levels.110-116 Thus, the Paleo diet may theoretically serve as a viable adjunct dietary approach to the treatment of cutaneous diseases associated with obesity and metabolic derangement.117

Carnivore Diet

Arguably the most controversial and radical diet is the carnivore diet. As the name implies, the carnivore diet is based on consuming solely animal products. A properly structured carnivore diet emphasizes a “nose-to-tail” eating approach where all parts of the animal including the muscle meats, organs, and fat are consumed. Proponents of the diet cite anthropologic evidence from fossil-stable carbon-13/carbon-12 isotope analyses, craniodental features, and numerous other adaptations that indicate increased consumption of meat during human evolution.118-122 Notably, many early humans ate a carnivore diet, but life span was very short at this time, suggesting the diet may not be as beneficial as has been suggested.

Despite the abundance of anecdotal evidence supporting its use for a variety of chronic conditions, including cutaneous autoimmune disease, there is a virtual absence of high-quality research on the carnivore diet.123-125

The purported benefits of the carnivore diet may be attributed to the consumption of organ meats that contain highly bioavailable essential vitamins and minerals, such as iron, zinc, copper, selenium, thiamine, niacin, folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin K, and choline.126-128 Other dietary compounds that have demonstrated benefit for skin health and are predominantly found in animal foods include carnosine, carnitine, creatine, taurine, coenzyme Q10, and collagen.129-134 Nevertheless, there is no data to recommend the elimination of antioxidant- and micronutrient-dense plant-based foods. Rigorous clinical research evaluating the efficacy and safety of the carnivore diet in dermatologic patients is needed. A carnivore diet should not be undertaken without the assistance of a dietician who can ensure adequate micronutrient and macronutrient support.

Final Thoughts

The adjunctive role of diet in the treatment of skin disease is expanding and becoming more widely accepted among dermatologists. Unfortunately, there remains a lack of randomized controlled trials confirming the efficacy of various dietary interventions in the dermatologic setting. Although evidence-based dietary recommendations currently are limited, it is important for dermatologists to be aware of the varied and nuanced dietary interventions employed by patients.

Ultimately, dietary recommendations must be personalized, considering a patient’s comorbidities, personal beliefs and preferences, and nutrigenetics. The emerging field of dermatonutrigenomics—the study of how dietary compounds interact with one’s genes to influence skin health—may allow for precise dietary recommendations to be made in dermatologic practice. Direct-to-consumer genetic tests targeted toward dermatology patients are already on the market, but their clinical utility awaits validation.1 Because nutritional science is a constantly evolving field, becoming familiar with these popular diets will serve both dermatologists and their patients well.

- Jaros J, Katta R, Shi VY. Dermatonutrigenomics: past, present, and future. Dermatology. 2019;235:164-166.

- Paoli A, Grimaldi K, Toniolo L, et al. Nutrition and acne: therapeutic potential of ketogenic diets. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:111-117.

- Melnik BC, Schmitz G. Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, hyperglycaemic food and milk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:833-841.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:247-256.

- Smith R, Mann N, Mäkeläinen H, et al. A pilot study to determine the short-term effects of a low glycemic load diet on hormonal markers of acne: a nonrandomized, parallel, controlled feeding trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:718-726.

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. The effect of a low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglycerides. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;50:41-52.

- Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, et al. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:241-246.

- Khandalavala BN, Do MV. Finasteride in hidradenitis suppurativa: a "male" therapy for a predominantly "female" disease. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:44.

- Nikolakis G, Karagiannidis I, Vaiopoulos AG, et al. Endocrinological mechanisms in the pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa [in German]. Hautarzt. 2020;71:762-771.

- Karadag AS, Ozlu E, Lavery MJ. Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes mellitus and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatology. 2018;36:89-93.

- Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:969-977.

- Anton SD, Hida A, Heekin K, et al. Effects of popular diets without specific calorie targets on weight loss outcomes: systematic review of findings from clinical trials. Nutrients. 2017;9:822.

- Castellana M, Conte E, Cignarelli A, et al. Efficacy and safety of very low calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) in patients with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2020;21:5-16.

- Paoli A, Mancin L, Giacona MC, et al. Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Transl Med. 2020;18:104.

- Dashti HM, Mathew TC, Hussein T, et al. Long-term effects of a ketogenic diet in obese patients. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2004;9:200-205.

- Lian N, Chen M. Metabolic syndrome and skin disease: potential connection and risk. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2019;2:89-93.

- Hu Y, Zhu Y, Lian N, et al. Metabolic syndrome and skin diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:788.

- Castaldo G, Rastrelli L, Galdo G, et al. Aggressive weight-loss program with a ketogenic induction phase for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a proof-of-concept, single-arm, open-label clinical trial. Nutrition. 2020;74:110757.

- Castaldo G, Pagano I, Grimaldi M, et al. Effect of very-low-calorie ketogenic diet on psoriasis patients: a nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabolomic study. J Proteome Res. 2021;20:1509-1521.

- Milder J, Liang L-P, Patel M. Acute oxidative stress and systemic Nrf2 activation by the ketogenic diet. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:238-244.

- Kubo E, Chhunchha B, Singh P, et al. Sulforaphane reactivates cellular antioxidant defense by inducing Nrf2/ARE/Prdx6 activity during aging and oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14130.

- Pinto A, Bonucci A, Maggi E, et al. Anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of ketogenic diet: new perspectives for neuroprotection in Alzheimer's disease. Antioxidants (Basel). 2018;7:63.

- Youm Y-H, Nguyen KY, Grant RW, et al. The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat Med. 2015;21:263-269.

- Kelley N, Jeltema D, Duan Y, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome: an overview of mechanisms of activation and regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3328.

- Fomin DA, McDaniel B, Crane J. The promising potential role of ketones in inflammatory dermatologic disease: a new frontier in treatment research. J Dermatol Treat. 2017;28:484-487.

- Rahman M, Muhammad S, Khan MA, et al. The β-hydroxybutyrate receptor HCA 2 activates a neuroprotective subset of macrophages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:1-11.

- Lu Y, Yang YY, Zhou MW, et al. Ketogenic diet attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation after spinal cord injury by activating Nrf2 and suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathways. Neurosci Lett. 2018;683:13-18.

- Hamarsheh S, Zeiser R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation in cancer: a double-edged sword. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1444.

- Bell S, Degitz K, Quirling M, et al. Involvement of NF-κB signalling in skin physiology and disease. Cell Signal. 2003;15:1-7.

- Goldminz AM, Au SC, Kim N, et al. NF-κB: an essential transcription factor in psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;69:89-94.

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589.

- McDaniel S, Rensing N, Yamada K, et al. The ketogenic diet inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. Epilepsia. 2011;52:E7-E11.

- Alter M, Satzger I, Schrem H, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer is reduced after switch of immunosuppression to mTOR-inhibitors in organ transplant recipients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:480-488.

- Feldmeyer L, Hofbauer GF, Böni T, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors slow skin carcinogenesis, but impair wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:422-424.

- Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:211-218.

- Li W. "Warburg effect" and mitochondrial metabolism in skin cancer.J Carcinogene Mutagene. 2012:S4.

- Naveed S, Aslam M, Ahmad A. Starvation based differential chemotherapy: a novel approach for cancer treatment. Oman Med J. 2014;29:391-398.

- Raffaghello L, Lee C, Safdie FM, et al. Starvation-dependent differential stress resistance protects normal but not cancer cells against high-dose chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8215-8220.

- Buono R, Longo VD. Starvation, stress resistance, and cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29:271-280.

- de Groot S, Pijl H, van der Hoeven JJM, et al. Effects of short-term fasting on cancer treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:209.

- Hosseini M, Kasraian Z, Rezvani HR. Energy metabolism in skin cancers: a therapeutic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2017;1858:712-722.

- Feichtinger RG, Lang R, Geilberger R, et al. Melanoma tumors exhibit a variable but distinct metabolic signature. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:204-207.

- Alshaya MA, Turkmani MG, Alissa AM. Prurigo pigmentosa following ketogenic diet and bariatric surgery: a growing association. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:504-507.

- Bellini M, Tonarelli S, Nagy AG, et al. Low FODMAP diet: evidence, doubts, and hopes. Nutrients. 2020;12:148.

- Kwiatkowski L, Rice E, Langland J. Integrative treatment of chronic abdominal bloating and pain associated with overgrowth of small intestinal bacteria: a case report. Altern Ther Health Med. 2017;23:56-61.

- Hubkova T. No more pain in the gut: lifestyle medicine approach to irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2017;11:223-226.

- Schumann D, Klose P, Lauche R, et al. Low fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyol diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2018;45:24-31.

- Cox SR, Prince AC, Myers CE, et al. Fermentable carbohydrates [FODMAPs] exacerbate functional gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, re-challenge trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1420-1429.

- Damas OM, Garces L, Abreu MT. Diet as adjunctive treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: review and update of the latest literature. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17:313-325.

- Wang FY, Chi CC. Rosacea, germs, and bowels: a review on gastrointestinal comorbidities and gut-skin axis of rosacea. Adv Ther. 2021;38:1415-1424.

- Daou H, Paradiso M, Hennessy K, et al. Rosacea and the microbiome: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1-12.

- Weinstock LB, Steinhoff M. Rosacea and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: prevalence and response to rifaximin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:875-876.

- Wu CY, Chang YT, Juan CK, et al. Risk of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with rosacea: results from a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:911-917.

- Egeberg A, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP, et al. Rosacea and gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:100-106.

- Drago F, De Col E, Agnoletti AF, et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: a 3-year follow-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:E113-E115.

- Parodi A, Paolino S, Greco A, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in rosacea: clinical effectiveness of its eradication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:759-764.

- Ojetti V, De Simone C, Aguilar Sanchez J, et al. Malabsorption in psoriatic patients: cause or consequence? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1267-1271.

- Kim M, Choi KH, Hwang SW, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased risk of inflammatory skin diseases: a population-based cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:40-48.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Indemini E, et al. Psoriasis and small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:112-113.

- Acharya P, Mathur M. Association between psoriasis and celiac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1376-1385.

- Bhatia BK, Millsop JW, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part II: celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:350-358.

- Michaëlsson G, Gerdén B, Hagforsen E, et al. Psoriasis patients with antibodies to gliadin can be improved by a gluten-free diet. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:44-51.

- Kolchak NA, Tetarnikova MK, Theodoropoulou MS, et al. Prevalence of antigliadin IgA antibodies in psoriasis vulgaris and response of seropositive patients to a gluten-free diet. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:13-19.

- De Bastiani R, Gabrielli M, Lora L, et al. Association between coeliac disease and psoriasis: Italian primary care multicentre study. Dermatology. 2015;230:156-160.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Loche F, Bazex J. Celiac disease associated with cutaneous sarcoidosic granuloma [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 1997;18:975-978.

- Rodríguez-García C, González-Hernández S, Pérez-Robayna N, et al. Repigmentation of vitiligo lesions in a child with celiac disease after a gluten-free diet. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:209-210.

- Wijarnpreecha K, Panjawatanan P, Corral JE, et al. Celiac disease and risk of sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Evid Based Med. 2019;12:194-199.

- Rodrigo L, Beteta-Gorriti V, Alvarez N, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations associated with celiac disease. Nutrients. 2018;10:800.

- Song MS, Farber D, Bitton A, et al. Dermatomyositis associated with celiac disease: response to a gluten-free diet. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:433-435.

- Egan CA, Smith EP, Taylor TB, et al. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis responsive to a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1927-1929.

- Comas-Basté O, Sánchez-Pérez S, Veciana-Nogués MT, et al. Histamine intolerance: the current state of the art. Biomolecules. 2020;10:1181.

- Ring J. Plasma histamine concentrations in atopic eczema. Clin Allergy. 1983;13:545-552.

- Maintz L, Benfadal S, Allam JP, et al. Evidence for a reduced histamine degradation capacity in a subgroup of patients with atopic eczema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1106-1112.

- Cornillier H, Giraudeau B, Samimi M, et al. Effect of diet in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:127-132.

- Son JH, Chung BY, Kim HO, et al. A histamine-free diet is helpful for treatment of adult patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:164-172.

- Wagner N, Dirk D, Peveling-Oberhag A, et al. A popular myth - low-histamine diet improves chronic spontaneous urticaria - fact or fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:650-655.

- Esposito K, Marfella R, Ciotola M, et al. Effect of a Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1440-1446.

- Steffen LM, Van Horn L, Daviglus ML, et al. A modified Mediterranean diet score is associated with a lower risk of incident metabolic syndrome over 25 years among young adults: the CARDIA (coronary artery risk development in young adults) study. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1654-1661.

- Bower A, Marquez S, de Mejia EG. The health benefits of selected culinary herbs and spices found in the traditional Mediterranean diet. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:2728-2746.

- Bosch R, Philips N, Suárez-Pérez JA, et al. Mechanisms of photoaging and cutaneous photocarcinogenesis, and photoprotective strategies with phytochemicals. Antioxidants (Basel). 2015;4:248-268.

- Katsimbri P, Korakas E, Kountouri A, et al. The effect of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacity of diet on psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis phenotype: nutrition as therapeutic tool? Antioxidants. 2021;10:157.

- Molina-Leyva A, Cuenca-Barrales C, Vega-Castillo JJ, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet in Spanish patients with psoriasis: cardiovascular benefits? Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:E12810.

- Barrea L, Balato N, Di Somma C, et al. Nutrition and psoriasis: is there any association between the severity of the disease and adherence to the Mediterranean diet? J Transl Med. 2015;13:1-10.

- Phan C, Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Association between Mediterranean anti-inflammatory dietary profile and severity of psoriasis: results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1017-1024.

- Korovesi A, Dalamaga M, Kotopouli M, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is independently associated with psoriasis risk, severity, and quality of life: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E164-E165.

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934-950.

- Skroza N, Tolino E, Semyonov L, et al. Mediterranean diet and familial dysmetabolism as factors influencing the development of acne. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:466-474.

- Barrea L, Fabbrocini G, Annunziata G, et al. Role of nutrition and adherence to the Mediterranean diet in the multidisciplinary approach of hidradenitis suppurativa: evaluation of nutritional status and its association with severity of disease. Nutrients. 2018;11:57.

- Nichols JA, Katiyar SK. Skin photoprotection by natural polyphenols: anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and DNA repair mechanisms. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:71-83.

- Huang T-H, Wang P-W, Yang S-C, et al. Cosmetic and therapeutic applications of fish oil's fatty acids on the skin. Mar Drugs. 2018;16:256.

- Rizwan M, Rodriguez-Blanco I, Harbottle A, et al. Tomato paste rich in lycopene protects against cutaneous photodamage in humans in vivo: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:154-162.

- Leone A, Martínez-González M, Martin-Gorgojo A, et al. Mediterranean diet, dietary approaches to stop hypertension, and pro-vegetarian dietary pattern in relation to the risk of basal cell carcinoma: a nested case-control study within the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112:364-372.

- Solway J, McBride M, Haq F, et al. Diet and dermatology: the role of a whole-food, plant-based diet in preventing and reversing skin aging--a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:38-43.

- Greger M. A whole food plant-based diet is effective for weight loss: the evidence. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14:500-510.

- Wright N, Wilson L, Smith M, et al. The BROAD study: a randomised controlled trial using a whole food plant-based diet in the community for obesity, ischaemic heart disease or diabetes. Nutr Diabetes. 2017;7:E256.

- Ornish D, Lin J, Chan JM, et al. Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1112-1120.

- Ornish D, Lin J, Daubenmier J, et al. Increased telomerase activity and comprehensive lifestyle changes: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1048-1057.

- Zouboulis CC, Makrantonaki E. Clinical aspects and molecular diagnostics of skin aging. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:3-14.

- Gupta L, Khandelwal D, Lal PR, et al. Palaeolithic diet in diabesity and endocrinopathies--a vegan's perspective. Eur Endocrinol. 2019;15:77-82.

- Chassaing B, Van de Wiele T, De Bodt J, et al. Dietary emulsifiers directly alter human microbiota composition and gene expression ex vivo potentiating intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2017;66:1414-1427.

- Thorburn Alison N, Macia L, Mackay Charles R. Diet, metabolites, and "Western lifestyle" inflammatory diseases. Immunity. 2014;40:833-842.

- Katta R, Schlichte M. Diet and dermatitis: food triggers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:30-36.

- Dhar S, Srinivas SM. Food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:645-648.

- Birmingham N, Thanesvorakul S, Gangur V. Relative immunogenicity of commonly allergenic foods versus rarely allergenic and nonallergenic foods in mice. J Food Prot. 2002;65:1988-1991.

- Yu W, Freeland DMH, Nadeau KC. Food allergy: immune mechanisms, diagnosis and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:751-765.

- Kowalski LM, Bujko J. Evaluation of biological and clinical potential of paleolithic diet [in Polish]. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2012;63:9-15.

- Lee JE, Titcomb TJ, Bisht B, et al. A modified MCT-based ketogenic diet increases plasma β-hydroxybutyrate but has less effect on fatigue and quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis compared to a modified paleolithic diet: a waitlist-controlled, randomized pilot study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2021;40:13-25.

- Abbott RD, Sadowski A, Alt AG. Efficacy of the autoimmune protocol diet as part of a multi-disciplinary, supported lifestyle intervention for Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Cureus. 2019;11:E4556.

- Lindeberg S, Jönsson T, Granfeldt Y, et al. A palaeolithic diet improves glucose tolerance more than a Mediterranean-like diet in individuals with ischaemic heart disease. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1795-1807.

- Jönsson T, Granfeldt Y, Ahrén B, et al. Beneficial effects of a paleolithic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a randomized cross-over pilot study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:35.

- Boers I, Muskiet FAJ, Berkelaar E, et al. Favourable effects of consuming a palaeolithic-type diet on characteristics of the metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled pilot-study. Lipids Health Dis. 2014;13:160.

- Ghaedi E, Mohammadi M, Mohammadi H, et al. Effects of a paleolithic diet on cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:634-646.

- Mellberg C, Sandberg S, Ryberg M, et al. Long-term effects of a palaeolithic-type diet in obese postmenopausal women: a 2-year randomized trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:350-357.

- Pastore RL, Brooks JT, Carbone JW. Paleolithic nutrition improves plasma lipid concentrations of hypercholesterolemic adults to a greater extent than traditional heart-healthy dietary recommendations. Nutr Res. 2015;35:474-479.

- Otten J, Stomby A, Waling M, et al. Benefits of a paleolithic diet with and without supervised exercise on fat mass, insulin sensitivity, and glycemic control: a randomized controlled trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33:E2828.

- Stefanadi EC, Dimitrakakis G, Antoniou C-K, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the skin: a more than superficial association. reviewing the association between skin diseases and metabolic syndrome and a clinical decision algorithm for high risk patients. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10:9.

- Mann N. Meat in the human diet: an anthropological perspective. Nutr Dietetics. 2007;64(suppl 4):S102-S107.

- Bramble DM, Lieberman DE. Endurance running and the evolution of Homo. Nature. 2004;432:345-352.

- Kuhn JE. Throwing, the shoulder, and human evolution. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2016;45:110-114.

- Kobayashi H, Kohshima S. Unique morphology of the human eye and its adaptive meaning: comparative studies on external morphology of the primate eye. J Hum Evol. 2001;40:419-435.

- Cordain L, Eaton SB, Miller JB, et al. The paradoxical nature of hunter-gatherer diets: meat-based, yet non-atherogenic. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(suppl 1):S42-S52.

- McClellan WS, Du Bois EF. Clinical calorimetry: XLV. prolonged meat diets with a study of kidney function and ketosis. J Biol Chem. 1930;87:651-668.

- O'Hearn A. Can a carnivore diet provide all essential nutrients? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2020;27:312-316.

- O'Hearn LA. A survey of improvements experienced on a carnivore diet compared to only carbohydrate restriction. Open Science Forum website. Published February 12, 2019. Accessed May 17, 2021. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/5FU4D

- Williams P. Nutritional composition of red meat. Nutrition & Dietetics. 2007;64(suppl 4):S113-S119.

- Biel W, Czerniawska-Piątkowska E, Kowalczyk A. Offal chemical composition from veal, beef, and lamb maintained in organic production systems. Animals (Basel). 2019;9:489.

- Elmadfa I, Meyer AL. The role of the status of selected micronutrients in shaping the immune function. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019;19:1100-1115.

- Babizhayev M. Treatment of skin aging and photoaging with innovative oral dosage forms of nonhydrolized carnosine and carcinine. Int J Clin Derm Res. 2017;5:116-143.

- Danby FW. Nutrition and aging skin: sugar and glycation. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:409-411.

- Siefken W, Carstensen S, Springmann G, et al. Role of taurine accumulation in keratinocyte hydration. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:354-361.

- Vollmer DL, West VA, Lephart ED. Enhancing skin health: by oral administration of natural compounds and minerals with implications to the dermal microbiome. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3059.

- Fischer F, Achterberg V, März A, et al. Folic acid and creatineimprove the firmness of human skin in vivo. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:15-23.

- Blatt T, Lenz H, Weber T. Topical application of creatine is multibeneficial for human skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:P32.

Within the last decade, almost 3000 articles have been published on the role of diet in the prevention and management of dermatologic conditions. Patients are increasingly interested in—and employing—dietary modifications that may influence skin appearance and aid in the treatment of cutaneous disease.1 It is essential that dermatologists are familiar with existing evidence on the role of diet in dermatology to counsel patients appropriately. Herein, we discuss the compositions of several popular diets and their proposed utility for dermatologic purposes. We highlight the limited literature that exists surrounding this topic and emphasize the need for future, well-designed clinical trials that study the impact of diet on skin disease.

Ketogenic Diet

The ketogenic diet has a macronutrient profile composed of high fat, low to moderate protein, and very low carbohydrates. Nutritional ketosis occurs as the body begins to use free fatty acids (via beta oxidation) as the primary metabolite driving cellular metabolism. It has been suggested that the ketogenic diet may impart beneficial effects on skin disease; however, limited literature exists on the role of nutritional ketosis in the treatment of dermatologic conditions.

Mechanistically, the ketogenic diet decreases the secretion of insulin and insulinlike growth factor 1, resulting in a reduction of circulating androgens and increased activity of the retinoid X receptor.2 In acne vulgaris, it has been suggested that the ketogenic diet may be beneficial in decreasing androgen-induced sebum production and the overproliferation of keratinocytes.2-7 The ketogenic diet is one of the most rapidly effective dietary strategies for normalizing both insulin and androgens, thus it may theoretically be useful for other metabolic and hormone-dependent skin diseases, such as hidradenitis suppurativa.8,9

The cutaneous manifestations associated with chronic hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia are numerous and include acanthosis nigricans, acrochordons, diabetic dermopathy, scleredema diabeticorum, bullosis diabeticorum, keratosis pilaris, and generalized granuloma annulare. There also is an increased risk for bacterial and fungal skin infections associated with hyperglycemic states.10 The ketogenic diet is an effective nonpharmacologic tool for normalizing serum insulin and glucose levels in most patients and may have utility in the aforementioned conditions.11,12 In addition to improving insulin sensitivity, it has been used as a dietary strategy for weight loss.11-15 Because obesity and metabolic syndrome are highly correlated with common skin conditions such as psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and androgenetic alopecia, there may be a role for employing the ketogenic diet in these patient populations.16,17

Although robust clinical studies on ketogenic diets in skin disease are lacking, a recent single-arm, open-label clinical trial observed benefit in all 37 drug-naïve, overweight patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who underwent a ketogenic weight loss protocol. Significant reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score and dermatology life quality index score were reported (P<.001).18 Another study of 30 patients with psoriasis found that a 4-week, low-calorie, ketogenic diet resulted in 50% improvement of PASI scores, 10% weight loss, and a reduction in the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-2.19 Despite these results, it is a challenge to tease out if the specific dietary intervention or its associated weight loss was the main driver in these reported improvements in skin disease.

There is mixed evidence on the anti-inflammatory nature of the ketogenic diet, likely due to wide variation in the composition of foods included in individual diets. In many instances, the ketogenic diet is thought to possess considerable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities. Ketones are known activators of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 pathway, which upregulates the production of glutathione, a major endogenous intracellular antioxidant.20 Additionally, dietary compounds from foods that are encouraged while on the ketogenic diet, such as sulforaphane from broccoli, also are independent activators of nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2.21 Ketones are efficiently utilized by mitochondria, which also may result in the decreased production of reactive oxygen species and lower oxidative stress.22 Moreover, the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate has demonstrated the ability to reduce proinflammatory IL-1β levels via suppression of nucleotide-binding domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activity.23,24 The activity of IL-1β is known to be elevated in many dermatologic conditions, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Schnitzler syndrome, hidradenitis suppurativa, Behçet disease, and other autoinflammatory syndromes.25 Ketones also have been shown to inhibit the nuclear factor–κB proinflammatory signaling pathway.22,26,27 Overexpression of IL-1β and aberrant activation of nuclear factor–κB are implicated in a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and oncologic cutaneous pathologies. The ketogenic diet may prove to be an effective adjunctive treatment for dermatologists to consider in select patient populations.23,24,28-30

For patients with keratinocyte carcinomas, the ketogenic diet may offer the aforementioned anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, as well as suppression of the mechanistic target of rapamycin, a major regulator of cell metabolism and proliferation.31,32 Inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamycin activity has been shown to slow tumor growth and reduce the development of squamous cell carcinoma.25,33,34 The ketogenic diet also may exploit the preferential utilization of glucose exhibited by many types of cancer cells, thereby “starving” the tumor of its primary fuel source.35,36 In vitro and animal studies in a variety of cancer types have demonstrated that a ketogenic metabolic state—achieved through the ketogenic diet or fasting—can sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapy and radiation while conferring a protective effect to normal cells.37-40 This recently described phenomenon is known as differential stress resistance, but it has not been studied in keratinocyte malignancies or melanoma to date. Importantly, some basal cell carcinomas and BRAF V600E–mutated melanomas have worsened while on the ketogenic diet, suggesting more data is needed before it can be recommended for all cancer patients.41,42 Furthermore, other skin conditions such as prurigo pigmentosa have been associated with initiation of the ketogenic diet.43

Low FODMAP Diet

Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed, osmotically active, and rapidly fermented by intestinal bacteria.44 The low FODMAP diet has been shown to be efficacious for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and some cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).44-49 A low FODMAP diet may have potential implications for several dermatologic conditions.

Rosacea has been associated with various gastrointestinal tract disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, SIBO, and IBD.50-54 A single study found that patients with rosacea had a 13-fold increased risk for SIBO.55,56 Treatment of 40 patients with SIBO using rifaximin resulted in complete resolution of rosacea in all patients, with no relapse after a 3-year follow-up period.55 Psoriasis also has been associated with SIBO and IBD.57,58 One small study found that eradication of SIBO in psoriatic patients resulted in improved PASI scores and colorimetric values.59

Although the long-term health consequences of the low FODMAP diet are unknown, further research on such dietary interventions for inflammatory skin conditions is warranted given the mounting evidence of a gut-skin connection and the role of the intestinal microbiome in skin health.50,51

Gluten-Free Diet

Gluten is a protein found in a variety of grains. Although the role of gluten in the pathogenesis of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis is indisputable, the deleterious effects of gluten outside of the context of these diseases remain controversial. There may be a compelling case for eliminating gluten in psoriasis patients with seropositivity for celiac disease. A recent systematic review found a 2.2-fold increased risk for celiac disease in psoriasis patients.60 Antigliadin antibody titers also were found to be positively correlated with psoriatic disease severity.61 In addition, one open-label study found a reduction in PASI scores in 73% of patients with antigliadin antibodies after 3 months on a gluten-free diet compared to those without antibodies; however, the study only included 22 patients.62 Several other small studies have yielded similar results63,64; however, antigliadin antibodies are neither the most sensitive nor specific markers of celiac disease, and additional testing should be completed in any patient who may carry this diagnosis. A survey study by the National Psoriasis Foundation found that the dietary change associated with the greatest skin improvement was removal of gluten and nightshade vegetables in approximately 50% of the 1200 psoriasis patients that responded.65 Case reports of various dermatologic conditions including sarcoidosis, vitiligo, alopecia areata, lichen planus, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and aphthous ulcerations have reportedly improved with a gluten-free diet; however, this should not be used as primary therapy in patients without celiac disease.66-71 Because gluten-free diets can be expensive and challenging to follow, a formal assessment for celiac disease should be considered before recommendation of this dietary intervention.

Low Histamine Diet

Histamine is a biogenic amine produced by the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine.72 It is found in several foods in varying amounts. Because bacteria can convert histidine into histamine, many fermented and aged foods such as kimchi, sauerkraut, cheese, and red wine contain high levels of histamine. Individuals who have decreased activity of diamine oxidase (DAO), an enzyme that degrades histamine, may be more susceptible to histamine intolerance.72 The symptoms of histamine intolerance are numerous and include gastrointestinal tract distress, rhinorrhea and nasal congestion, headache, urticaria, flushing, and pruritus. Histamine intolerance can mimic an IgE-mediated food allergy; however, allergy testing is negative in these patients. Unfortunately, there is no laboratory test for histamine intolerance; a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge is considered the gold-standard test.72

As it pertains to dermatology, a low histamine diet may play a role in the treatment of certain patients with atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria. One study reported that 17 of 54 (31.5%) atopic patients had higher basal levels of serum histamine compared to controls.73 Another study found that a histamine-free diet led to improvement in both histamine intolerance symptoms and atopic dermatitis disease severity (SCORing atopic dermatitis) in patients with low DAO activity.74 In chronic spontaneous urticaria, a recent systematic review found that in 223 patients placed on a low histamine diet for 3 to 4 weeks, 12% and 44% achieved complete and partial remission, respectively.75 Although treatment response based on a patient’s DAO activity level has not been correlated, a diet low in histamine may prove useful for patients with persistent atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria who have negative food allergy tests and report exacerbation of symptoms after ingestion of histamine-rich foods.76,77

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet has been touted as one of the healthiest diets to date, and large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated its effectiveness in weight loss, improving insulin sensitivity, and reducing inflammatory cytokine profiles.78,79 A major criticism of the Mediterranean diet is that it has considerable ambiguity and lacks a precise definition due to the variability of what is consumed in different Mediterranean regions. Generally, the diet emphasizes high consumption of colorful fruits and vegetables, aromatic herbs and spices, olive oil, nuts, and seafood, as well as modest amounts of dairy, eggs, and red meat.80 The anti-inflammatory effects of this diet largely have been attributed to its abundance of polyphenols, carotenoids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).80,81 Examples of polyphenols include resveratrol in red grapes, quercetin in apples and red onions, and curcumin in turmeric, while examples of carotenoids include lycopene in tomatoes and zeaxanthin in dark leafy greens. Oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid present in high concentrations in olive oil, while eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are omega-3 PUFAs predominantly found in fish.82

Unfortunately, rigorous clinical trials regarding the Mediterranean diet as it pertains to dermatology have not been undertaken. Numerous observational studies in patients with psoriasis have suggested that close adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with improvement in PASI scores.83-86 The National Psoriasis Foundation now recommends a trial of the Mediterranean diet in some patients with psoriasis, emphasizing increased dietary intake of olive oil, fish, and vegetables.87 Adherence to a Mediterranean diet also has been inversely correlated to the severity of acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa88,89; however, these studies failed to account for the multifactorial risk factors associated with these conditions. Mediterranean diets also may impart a chemopreventive effect, supported by a number of in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrating the inhibition and/or reversal of cutaneous DNA damage induced by UV radiation through supplementation with various phytonutrients and omega-3 PUFAs.81,90-92 Although small case-control studies have found a decreased risk of basal cell carcinoma in those who closely adhered to a Mediterranean diet, more rigorous clinical research is needed.93

Whole-Food, Plant-Based Diet

A whole-food, plant-based (WFPB) diet is another popular dietary approach that consists of eating fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and grains in their whole natural form.94 This diet discourages all animal products, including red meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs. It is similar to a vegan diet except that it eliminates all highly refined carbohydrates, vegetable oils, and other processed foods.94 Randomized clinical studies have demonstrated the WFPB diet to be effective in the treatment of obesity and metabolic syndrome.95,96

A WFPB diet has been shown to increase the antioxidant capacity of cells, lengthen telomeres, and reduce formation of advanced glycation end products.94,97,98 These benefits may help combat accelerated skin aging, including increased skin permeability, reduced elasticity and hydration, decreased angiogenesis, impaired immune function, and decreased vitamin D synthesis. Accelerated skin aging can result in delayed wound healing and susceptibility to skin tears and ecchymoses and also may promote the development of cutaneous malignancies.99 There remains a lack of clinical data studying a properly formulated WFPB diet in the dermatologic setting.

Paleolithic Diet

The paleolithic (Paleo) diet is an increasingly popular way of eating that attempts to mirror what our ancestors may have consumed between 10,000 and 2.5 million years ago.100 It is similar to the Mediterranean diet but excludes grains, dairy, legumes, and nightshade vegetables. It also calls for elimination of highly processed sugars and oils as well as chemical food additives and preservatives. There is a strict variation of the diet for individuals with autoimmune disease that also excludes eggs, nuts, and seeds, as these can be inflammatory or immunogenic in some patients.100-106 Other variations of the diet exist, including the ketogenic Paleo diet, pegan (Paleo vegan) diet, and lacto-Paleo diet.100 An often cited criticism of the Paleo diet is the low intake of calcium and risk for osteoporosis; however, consumption of calcium-rich foods or a calcium supplement can address this concern.107

Although small clinical studies have found the Paleo diet to be beneficial for various autoimmune diseases, clinical data evaluating the utility of the diet for cutaneous disease is lacking.108,109 Numerous randomized trials have demonstrated the Paleo diet to be effective for weight loss and improving insulin sensitivity and lipid levels.110-116 Thus, the Paleo diet may theoretically serve as a viable adjunct dietary approach to the treatment of cutaneous diseases associated with obesity and metabolic derangement.117

Carnivore Diet

Arguably the most controversial and radical diet is the carnivore diet. As the name implies, the carnivore diet is based on consuming solely animal products. A properly structured carnivore diet emphasizes a “nose-to-tail” eating approach where all parts of the animal including the muscle meats, organs, and fat are consumed. Proponents of the diet cite anthropologic evidence from fossil-stable carbon-13/carbon-12 isotope analyses, craniodental features, and numerous other adaptations that indicate increased consumption of meat during human evolution.118-122 Notably, many early humans ate a carnivore diet, but life span was very short at this time, suggesting the diet may not be as beneficial as has been suggested.

Despite the abundance of anecdotal evidence supporting its use for a variety of chronic conditions, including cutaneous autoimmune disease, there is a virtual absence of high-quality research on the carnivore diet.123-125

The purported benefits of the carnivore diet may be attributed to the consumption of organ meats that contain highly bioavailable essential vitamins and minerals, such as iron, zinc, copper, selenium, thiamine, niacin, folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin K, and choline.126-128 Other dietary compounds that have demonstrated benefit for skin health and are predominantly found in animal foods include carnosine, carnitine, creatine, taurine, coenzyme Q10, and collagen.129-134 Nevertheless, there is no data to recommend the elimination of antioxidant- and micronutrient-dense plant-based foods. Rigorous clinical research evaluating the efficacy and safety of the carnivore diet in dermatologic patients is needed. A carnivore diet should not be undertaken without the assistance of a dietician who can ensure adequate micronutrient and macronutrient support.

Final Thoughts

The adjunctive role of diet in the treatment of skin disease is expanding and becoming more widely accepted among dermatologists. Unfortunately, there remains a lack of randomized controlled trials confirming the efficacy of various dietary interventions in the dermatologic setting. Although evidence-based dietary recommendations currently are limited, it is important for dermatologists to be aware of the varied and nuanced dietary interventions employed by patients.

Ultimately, dietary recommendations must be personalized, considering a patient’s comorbidities, personal beliefs and preferences, and nutrigenetics. The emerging field of dermatonutrigenomics—the study of how dietary compounds interact with one’s genes to influence skin health—may allow for precise dietary recommendations to be made in dermatologic practice. Direct-to-consumer genetic tests targeted toward dermatology patients are already on the market, but their clinical utility awaits validation.1 Because nutritional science is a constantly evolving field, becoming familiar with these popular diets will serve both dermatologists and their patients well.

Within the last decade, almost 3000 articles have been published on the role of diet in the prevention and management of dermatologic conditions. Patients are increasingly interested in—and employing—dietary modifications that may influence skin appearance and aid in the treatment of cutaneous disease.1 It is essential that dermatologists are familiar with existing evidence on the role of diet in dermatology to counsel patients appropriately. Herein, we discuss the compositions of several popular diets and their proposed utility for dermatologic purposes. We highlight the limited literature that exists surrounding this topic and emphasize the need for future, well-designed clinical trials that study the impact of diet on skin disease.

Ketogenic Diet

The ketogenic diet has a macronutrient profile composed of high fat, low to moderate protein, and very low carbohydrates. Nutritional ketosis occurs as the body begins to use free fatty acids (via beta oxidation) as the primary metabolite driving cellular metabolism. It has been suggested that the ketogenic diet may impart beneficial effects on skin disease; however, limited literature exists on the role of nutritional ketosis in the treatment of dermatologic conditions.

Mechanistically, the ketogenic diet decreases the secretion of insulin and insulinlike growth factor 1, resulting in a reduction of circulating androgens and increased activity of the retinoid X receptor.2 In acne vulgaris, it has been suggested that the ketogenic diet may be beneficial in decreasing androgen-induced sebum production and the overproliferation of keratinocytes.2-7 The ketogenic diet is one of the most rapidly effective dietary strategies for normalizing both insulin and androgens, thus it may theoretically be useful for other metabolic and hormone-dependent skin diseases, such as hidradenitis suppurativa.8,9

The cutaneous manifestations associated with chronic hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia are numerous and include acanthosis nigricans, acrochordons, diabetic dermopathy, scleredema diabeticorum, bullosis diabeticorum, keratosis pilaris, and generalized granuloma annulare. There also is an increased risk for bacterial and fungal skin infections associated with hyperglycemic states.10 The ketogenic diet is an effective nonpharmacologic tool for normalizing serum insulin and glucose levels in most patients and may have utility in the aforementioned conditions.11,12 In addition to improving insulin sensitivity, it has been used as a dietary strategy for weight loss.11-15 Because obesity and metabolic syndrome are highly correlated with common skin conditions such as psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and androgenetic alopecia, there may be a role for employing the ketogenic diet in these patient populations.16,17

Although robust clinical studies on ketogenic diets in skin disease are lacking, a recent single-arm, open-label clinical trial observed benefit in all 37 drug-naïve, overweight patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who underwent a ketogenic weight loss protocol. Significant reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) score and dermatology life quality index score were reported (P<.001).18 Another study of 30 patients with psoriasis found that a 4-week, low-calorie, ketogenic diet resulted in 50% improvement of PASI scores, 10% weight loss, and a reduction in the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-2.19 Despite these results, it is a challenge to tease out if the specific dietary intervention or its associated weight loss was the main driver in these reported improvements in skin disease.

There is mixed evidence on the anti-inflammatory nature of the ketogenic diet, likely due to wide variation in the composition of foods included in individual diets. In many instances, the ketogenic diet is thought to possess considerable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capabilities. Ketones are known activators of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 pathway, which upregulates the production of glutathione, a major endogenous intracellular antioxidant.20 Additionally, dietary compounds from foods that are encouraged while on the ketogenic diet, such as sulforaphane from broccoli, also are independent activators of nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2.21 Ketones are efficiently utilized by mitochondria, which also may result in the decreased production of reactive oxygen species and lower oxidative stress.22 Moreover, the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate has demonstrated the ability to reduce proinflammatory IL-1β levels via suppression of nucleotide-binding domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome activity.23,24 The activity of IL-1β is known to be elevated in many dermatologic conditions, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis, relapsing polychondritis, Schnitzler syndrome, hidradenitis suppurativa, Behçet disease, and other autoinflammatory syndromes.25 Ketones also have been shown to inhibit the nuclear factor–κB proinflammatory signaling pathway.22,26,27 Overexpression of IL-1β and aberrant activation of nuclear factor–κB are implicated in a variety of inflammatory, autoimmune, and oncologic cutaneous pathologies. The ketogenic diet may prove to be an effective adjunctive treatment for dermatologists to consider in select patient populations.23,24,28-30

For patients with keratinocyte carcinomas, the ketogenic diet may offer the aforementioned anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, as well as suppression of the mechanistic target of rapamycin, a major regulator of cell metabolism and proliferation.31,32 Inhibition of mechanistic target of rapamycin activity has been shown to slow tumor growth and reduce the development of squamous cell carcinoma.25,33,34 The ketogenic diet also may exploit the preferential utilization of glucose exhibited by many types of cancer cells, thereby “starving” the tumor of its primary fuel source.35,36 In vitro and animal studies in a variety of cancer types have demonstrated that a ketogenic metabolic state—achieved through the ketogenic diet or fasting—can sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapy and radiation while conferring a protective effect to normal cells.37-40 This recently described phenomenon is known as differential stress resistance, but it has not been studied in keratinocyte malignancies or melanoma to date. Importantly, some basal cell carcinomas and BRAF V600E–mutated melanomas have worsened while on the ketogenic diet, suggesting more data is needed before it can be recommended for all cancer patients.41,42 Furthermore, other skin conditions such as prurigo pigmentosa have been associated with initiation of the ketogenic diet.43

Low FODMAP Diet

Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) are short-chain carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed, osmotically active, and rapidly fermented by intestinal bacteria.44 The low FODMAP diet has been shown to be efficacious for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and some cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).44-49 A low FODMAP diet may have potential implications for several dermatologic conditions.

Rosacea has been associated with various gastrointestinal tract disorders including irritable bowel syndrome, SIBO, and IBD.50-54 A single study found that patients with rosacea had a 13-fold increased risk for SIBO.55,56 Treatment of 40 patients with SIBO using rifaximin resulted in complete resolution of rosacea in all patients, with no relapse after a 3-year follow-up period.55 Psoriasis also has been associated with SIBO and IBD.57,58 One small study found that eradication of SIBO in psoriatic patients resulted in improved PASI scores and colorimetric values.59

Although the long-term health consequences of the low FODMAP diet are unknown, further research on such dietary interventions for inflammatory skin conditions is warranted given the mounting evidence of a gut-skin connection and the role of the intestinal microbiome in skin health.50,51

Gluten-Free Diet

Gluten is a protein found in a variety of grains. Although the role of gluten in the pathogenesis of celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis is indisputable, the deleterious effects of gluten outside of the context of these diseases remain controversial. There may be a compelling case for eliminating gluten in psoriasis patients with seropositivity for celiac disease. A recent systematic review found a 2.2-fold increased risk for celiac disease in psoriasis patients.60 Antigliadin antibody titers also were found to be positively correlated with psoriatic disease severity.61 In addition, one open-label study found a reduction in PASI scores in 73% of patients with antigliadin antibodies after 3 months on a gluten-free diet compared to those without antibodies; however, the study only included 22 patients.62 Several other small studies have yielded similar results63,64; however, antigliadin antibodies are neither the most sensitive nor specific markers of celiac disease, and additional testing should be completed in any patient who may carry this diagnosis. A survey study by the National Psoriasis Foundation found that the dietary change associated with the greatest skin improvement was removal of gluten and nightshade vegetables in approximately 50% of the 1200 psoriasis patients that responded.65 Case reports of various dermatologic conditions including sarcoidosis, vitiligo, alopecia areata, lichen planus, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, linear IgA bullous dermatosis, and aphthous ulcerations have reportedly improved with a gluten-free diet; however, this should not be used as primary therapy in patients without celiac disease.66-71 Because gluten-free diets can be expensive and challenging to follow, a formal assessment for celiac disease should be considered before recommendation of this dietary intervention.

Low Histamine Diet

Histamine is a biogenic amine produced by the decarboxylation of the amino acid histidine.72 It is found in several foods in varying amounts. Because bacteria can convert histidine into histamine, many fermented and aged foods such as kimchi, sauerkraut, cheese, and red wine contain high levels of histamine. Individuals who have decreased activity of diamine oxidase (DAO), an enzyme that degrades histamine, may be more susceptible to histamine intolerance.72 The symptoms of histamine intolerance are numerous and include gastrointestinal tract distress, rhinorrhea and nasal congestion, headache, urticaria, flushing, and pruritus. Histamine intolerance can mimic an IgE-mediated food allergy; however, allergy testing is negative in these patients. Unfortunately, there is no laboratory test for histamine intolerance; a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge is considered the gold-standard test.72

As it pertains to dermatology, a low histamine diet may play a role in the treatment of certain patients with atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria. One study reported that 17 of 54 (31.5%) atopic patients had higher basal levels of serum histamine compared to controls.73 Another study found that a histamine-free diet led to improvement in both histamine intolerance symptoms and atopic dermatitis disease severity (SCORing atopic dermatitis) in patients with low DAO activity.74 In chronic spontaneous urticaria, a recent systematic review found that in 223 patients placed on a low histamine diet for 3 to 4 weeks, 12% and 44% achieved complete and partial remission, respectively.75 Although treatment response based on a patient’s DAO activity level has not been correlated, a diet low in histamine may prove useful for patients with persistent atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria who have negative food allergy tests and report exacerbation of symptoms after ingestion of histamine-rich foods.76,77

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet has been touted as one of the healthiest diets to date, and large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated its effectiveness in weight loss, improving insulin sensitivity, and reducing inflammatory cytokine profiles.78,79 A major criticism of the Mediterranean diet is that it has considerable ambiguity and lacks a precise definition due to the variability of what is consumed in different Mediterranean regions. Generally, the diet emphasizes high consumption of colorful fruits and vegetables, aromatic herbs and spices, olive oil, nuts, and seafood, as well as modest amounts of dairy, eggs, and red meat.80 The anti-inflammatory effects of this diet largely have been attributed to its abundance of polyphenols, carotenoids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).80,81 Examples of polyphenols include resveratrol in red grapes, quercetin in apples and red onions, and curcumin in turmeric, while examples of carotenoids include lycopene in tomatoes and zeaxanthin in dark leafy greens. Oleic acid is a monounsaturated fatty acid present in high concentrations in olive oil, while eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid are omega-3 PUFAs predominantly found in fish.82

Unfortunately, rigorous clinical trials regarding the Mediterranean diet as it pertains to dermatology have not been undertaken. Numerous observational studies in patients with psoriasis have suggested that close adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with improvement in PASI scores.83-86 The National Psoriasis Foundation now recommends a trial of the Mediterranean diet in some patients with psoriasis, emphasizing increased dietary intake of olive oil, fish, and vegetables.87 Adherence to a Mediterranean diet also has been inversely correlated to the severity of acne vulgaris and hidradenitis suppurativa88,89; however, these studies failed to account for the multifactorial risk factors associated with these conditions. Mediterranean diets also may impart a chemopreventive effect, supported by a number of in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrating the inhibition and/or reversal of cutaneous DNA damage induced by UV radiation through supplementation with various phytonutrients and omega-3 PUFAs.81,90-92 Although small case-control studies have found a decreased risk of basal cell carcinoma in those who closely adhered to a Mediterranean diet, more rigorous clinical research is needed.93

Whole-Food, Plant-Based Diet

A whole-food, plant-based (WFPB) diet is another popular dietary approach that consists of eating fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, and grains in their whole natural form.94 This diet discourages all animal products, including red meat, seafood, dairy, and eggs. It is similar to a vegan diet except that it eliminates all highly refined carbohydrates, vegetable oils, and other processed foods.94 Randomized clinical studies have demonstrated the WFPB diet to be effective in the treatment of obesity and metabolic syndrome.95,96