User login

Is hepatitis C an STI?

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

A 32-year-old woman had sex with a man she met while on vacation 6 weeks ago. She was intoxicated at the time and does not know much about the person. She recalls having engaged in vaginal intercourse without a condom. She does not have any symptoms.

She previously received baseline lab testing per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines 2 years ago with a negative HIV test and negative hepatitis C test. She asks for testing for STIs. What would you recommend?

A. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus

B. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex virus

C. HIV, hepatitis C, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

D. HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia

E. Gonorrhea and chlamydia

HIV risk estimate

The most practical answer is E, check for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Many protocols in place for evaluating people for STIs will test for hepatitis C as well as HIV with single exposures. In this column, we will look at the lack of evidence of heterosexual sexual transmission of hepatitis C.

In regards to HIV risk, the estimated risk of transmission male to female from an HIV-infected individual is 0.08% per sexual encounter.1 The prevalence in the United States – where HIV occurs in about 0.5% of the adult population – was used to estimate the risk of a person with unknown HIV status acquiring HIV. The calculated risk from one sexual encounter would be 0.0004 (1 in 250,000).

Studies of hepatitis C transmission

Tahan and colleagues did a prospective study of 600 heterosexual couples where one partner had hepatitis C and the other didn’t. Over a mean of 3 years of follow-up, none of the seronegative spouses developed hepatitis C.2

Terrault and colleagues completed a cross-sectional study of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–positive individuals and their monogamous heterosexual partners to evaluate risk of sexual transmission of HCV.3 Based on 8,377 person-years of follow-up, the estimated maximum transmission rate was 0.07%/year, which was about 1/190,000 sexual contacts. No specific sexual practices were associated with transmission. The authors of this study concurred with CDC recommendations that persons with HCV infection in long-term monogamous relationships need not change their sexual practices.4

Vandelli and colleagues followed 776 heterosexual partners of HCV-infected individuals over 10 years.5 None of the couples reported condom use. Over the follow up period, three HCV infections occurred, but based on discordance of the typing of viral isolates, sexual transmission was excluded.

Jin and colleagues completed a systematic review of studies looking at possible sexual transmission of HCV in gay and bisexual men.6 HIV-positive men had a HCV incidence of 6.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 0.4 per 1000 person-years in HIV-negative men. The authors discussed several possible causes for increased transmission risk in HIV-infected individuals including coexisting STIs and higher HCV viral load in semen of HIV-infected individuals, as well as lower immunity.

Summary

In hepatitis C–discordant heterosexual couples, hepatitis C does not appear to be sexually transmitted.

The risk of sexual transmission of hepatitis C to non–HIV-infected individuals appears to be exceedingly low.

Many thanks to Hunter Handsfield, MD, for suggesting this topic and sharing supporting articles.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

1. Boily MC et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Feb;9(2):118-29.

2. Tahan V et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:821-4.

3. Terrault NA et al. Hepatology. 2013;57:881-9

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47:1-38.

5. Vandelli C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:855-9.

6. Jin F et al. Sexual Health.2017;14:28-41.

Tuberculosis: The disease that changed world history

Almost forgotten today, tuberculosis is still one of the deadliest infectious diseases in the world. In an interview with Coliquio, Ronald D. Gerste, MD, PhD, an ophthalmologist and historian, looked back on this disease’s eventful history, which encompasses outstanding discoveries and catastrophic failures in diagnosis and treatment from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Under different names, TB has affected mankind for millennia. One of these names was the “aesthetic disease,” because it led to weight loss and pallor in the younger patients that it often affected. This was considered the ideal of beauty in the Victorian era. Many celebrities suffered from the disease, including poets and artists such as Friedrich Schiller, Lord Byron, and the Bronte family. As recently as the early 1990s, the disease almost changed world history, because Nelson Mandela became ill before the negotiations that led to the end of apartheid in South Africa.

Today, the global community is still not on track to meet its self-imposed targets for controlling the infectious disease, as reported by the World Health Organization on World TB Day in late March. Children and young people are the leading victims. In 2020 alone, 1.1 million children and adolescents under age 15 years were infected with TB, and 226,000 died of the disease, according to the WHO.

Q: Nelson Mandela was ill with tuberculosis during his imprisonment. How did the disease manifest itself in the future Nobel Peace Prize winner, and what is known about the treatment?

Ronald D. Gerste: Nelson Mandela contracted tuberculosis in 1988. At that time, he was 70 years old and had been in prison for 26 years. The disease presented in him with the almost classic symptom: He was coughing up blood and was also increasingly fatigued and losing weight. After doctors initially suspected a viral infection, but then TB was proven, he was treated with medication, and fluid was also drained from his lungs. [Mr.] Mandela was hospitalized for six weeks at Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town, the second largest hospital in South Africa. The therapy worked well, but [Mr.] Mandela’s lungs remained damaged. He was subsequently prone to pneumonia and was repeatedly hospitalized for pneumonia in 2012 and 2013.

Q: Mandela was lucky that the treatment worked for him. A few years later, the first antibiotic-resistant pathogen strains developed. How did medical research respond to this development?

Gerste: The emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR) strains of the pathogen prompted the WHO to declare a “global health emergency” in 1993. Three years later, World TB Day was proclaimed to raise awareness of the threat posed by this disease, which has been known since ancient times. It always takes place on March 24, the day in 1882 when Robert Koch gave his famous lecture in Berlin in which he announced the discovery of the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Medical research has introduced new drugs into TB therapy, such as bedaquiline and delamanid. But MDR tuberculosis therapy remains a global challenge and has diminished hopes of eradicating tuberculosis, as we did with smallpox some 40 years ago. Today, only 56% of all MDR-TB patients worldwide are successfully treated.

Q: As already mentioned, the TB pathogen was discovered by Robert Koch. How did this come about?

Gerste: Along with cholera, TB was a great epidemic of the 19th century. For an ambitious researcher like Robert Koch, who had made a name for himself with the discovery of anthrax in 1876, there was no more rewarding goal than to find the cause of this infectious disease, which claimed the lives of many famous people such as Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Schiller, as well as many whose names are forgotten today.

[Dr.] Koch worked with his cultures for several years; the method of staining with methylene blue that was developed by the young Paul Ehrlich represented a breakthrough. To this method, [Dr.] Koch added a second, brownish dye. After countless experiments, this allowed slightly curved bacilli to be identified in tuberculous material under the microscope.

On the evening of March 24, 1882, [Dr.] Koch gave a lecture at the Institute of Physiology in Berlin with the title “Etiology of TB,” which sounded less than sensational on the invitations. One or two dozen participants had been expected, but more than one hundred came; numerous listeners had to make do with standing room behind the rows of chairs in the lecture hall. After a rather dry presentation ([Dr.] Koch was not a great orator nor a self-promoter), he presented his results to those present.

His assistants had set up a series of microscopes in the lecture hall through which everyone could get a glimpse of this enemy of humanity: the tubercle bacillus. When [Dr.] Koch had finished his remarks, there was silence in the hall. There was no burst of applause; the audience was too deeply aware that they had witnessed a historic moment. Paul Ehrlich later said that this evening had been the most significant scientific experience of his life. Over the next few weeks, the newspapers made a national hero out of Robert Koch, and the Emperor appointed him a Privy Councilor of the Government. The country doctor from Pomerania was now the figurehead of science in the young German Empire.

Q: Shortly after his discovery, [Dr.] Koch advertised a vaccination against TB with the active ingredient tuberculin. Was he able to convince with that too?

Gerste: No, this was the big flop, almost the disaster of a remarkable scientific career. The preparation of attenuated tubercle bacilli with water and glycerin not only did not prevent infection at all, it proved fatal for numerous users. However, tuberculin has survived in a modified form: as a tuberculin test, in which a characteristic skin rash indicates that a tested person has already had contact with the Mycobacterium.

Q: How have diagnostic options and treatment of the disease evolved since Robert Koch’s lifetime?

Gerste: A very decisive advance was made in diagnostics. With the rather accidental discovery of the rays soon named after him by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in the last days of 1895, it became possible to visualize the lung changes that tuberculosis caused in an unexpected way on living patients; the serial examinations for TB by X-rays were the logical consequence. Both scientists received Nobel Prizes, which were still new at the time, within a few years of each other: [Dr.] Röntgen in 1901 for physics, and [Dr]. Koch in 1905 for medicine and physiology.

Effective drugs were practically unavailable toward the end of the 19th century. For those who could afford it, however, a whole new world of (hoped-for or perceived) healing from “consumption” opened up: the sanatorium, located high in the mountains, surrounded by “fresh air.” The most famous of these climatic health resorts is probably Davos. It is no disrespect to the Swiss Confederation, which I hold in high esteem, to point out that Switzerland owes its high status as a tourist destination and thus its prosperity in part to TB.

Q: Things were quite different in earlier times. Until 250 years ago, the hopes of many patients rested on the medieval healing method of the “royal touch.” What’s that all about?

Gerste: In the Middle Ages, a “healing method” emerged from which not only lepers and other seriously ill people but also those suffering from consumption expected to be saved: the “royal touch,” which was first described by the Frankish king Clovis in 496. This ceremony was based on the idea that the king or queen, anointed by God, could improve or even cure the ailment of a sick person through a brief touch.

With the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, this act, during which thousands often gathered in front of the ruler’s residence, was practiced on a large scale. The sufferers passed by the anointed ruler as if in a procession and were briefly touched by him or her. The extremely few “successes” were of course exploited by royal propaganda to proclaim the blessing that the reign of the king or queen meant for the country. But on those who nevertheless fell victim to TB or another ailment, the chroniclers remained silent.

Charles II of England, who ruled from 1660 to 1685 during the Restoration after the English Civil War, is said to have touched 92,102 sick people during this period, according to contemporary counts. The record for a single day’s performance is probably held by Louis XVI of France, who is said to have touched a total of 2,400 sufferers on June 14, 1775. Some of them may have stood and cheered in the Paris crowd 18 years later as the king climbed the steps to the guillotine.

Q: Another invention associated with TB diagnosis is the stethoscope. How did it come about?

Gerste: A young physician named René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec had already experienced the importance of diagnosing TB in his student years. His teacher in Paris was Xavier Bichat, considered the founder of histology, who died of TB in [Dr.] Laënnec’s second year at the age of only 30. [Dr.] Laënnec was a devotee of auscultation and made it work with a massively overweight patient by rolling up a sheet of paper, then placing this on the woman’s thorax to listen to her heart sounds. He developed the idea further and built a hollow wooden tube with a metal earpiece. In 1818, he presented the device at the meeting of the Academy of Sciences in Paris; he called it a stethoscope. He used his new instrument primarily to auscultate the lungs of patients with TB and distinguished the sounds of TB cavities from those of other lung diseases such as pneumonia and emphysema.

Q: Back to the present day: The WHO wants to eradicate TB once and for all. What are the hopes and fears in the fight against this disease?

Gerste: There is no doubt that we are currently taking a step backwards in these efforts, and this is not only due to multiresistant pathogens. Especially in poorer countries particularly affected by TB, treatment and screening programs have been disrupted by lockdown measures targeting COVID-19. The WHO suspects that in the first pandemic year, 2020, about half a million additional people may have died from TB because they never received a diagnosis.

Dr. Gerste, born in 1957, is a physician and historian. Dr. Gerste has lived for many years as a correspondent and book author in Washington, D.C., where he writes primarily for the New Journal of Zürich, the FAS, Back Then, the German Medical Journal, and other academic journals.

This article was translated from Coliquio.

Almost forgotten today, tuberculosis is still one of the deadliest infectious diseases in the world. In an interview with Coliquio, Ronald D. Gerste, MD, PhD, an ophthalmologist and historian, looked back on this disease’s eventful history, which encompasses outstanding discoveries and catastrophic failures in diagnosis and treatment from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Under different names, TB has affected mankind for millennia. One of these names was the “aesthetic disease,” because it led to weight loss and pallor in the younger patients that it often affected. This was considered the ideal of beauty in the Victorian era. Many celebrities suffered from the disease, including poets and artists such as Friedrich Schiller, Lord Byron, and the Bronte family. As recently as the early 1990s, the disease almost changed world history, because Nelson Mandela became ill before the negotiations that led to the end of apartheid in South Africa.

Today, the global community is still not on track to meet its self-imposed targets for controlling the infectious disease, as reported by the World Health Organization on World TB Day in late March. Children and young people are the leading victims. In 2020 alone, 1.1 million children and adolescents under age 15 years were infected with TB, and 226,000 died of the disease, according to the WHO.

Q: Nelson Mandela was ill with tuberculosis during his imprisonment. How did the disease manifest itself in the future Nobel Peace Prize winner, and what is known about the treatment?

Ronald D. Gerste: Nelson Mandela contracted tuberculosis in 1988. At that time, he was 70 years old and had been in prison for 26 years. The disease presented in him with the almost classic symptom: He was coughing up blood and was also increasingly fatigued and losing weight. After doctors initially suspected a viral infection, but then TB was proven, he was treated with medication, and fluid was also drained from his lungs. [Mr.] Mandela was hospitalized for six weeks at Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town, the second largest hospital in South Africa. The therapy worked well, but [Mr.] Mandela’s lungs remained damaged. He was subsequently prone to pneumonia and was repeatedly hospitalized for pneumonia in 2012 and 2013.

Q: Mandela was lucky that the treatment worked for him. A few years later, the first antibiotic-resistant pathogen strains developed. How did medical research respond to this development?

Gerste: The emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR) strains of the pathogen prompted the WHO to declare a “global health emergency” in 1993. Three years later, World TB Day was proclaimed to raise awareness of the threat posed by this disease, which has been known since ancient times. It always takes place on March 24, the day in 1882 when Robert Koch gave his famous lecture in Berlin in which he announced the discovery of the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Medical research has introduced new drugs into TB therapy, such as bedaquiline and delamanid. But MDR tuberculosis therapy remains a global challenge and has diminished hopes of eradicating tuberculosis, as we did with smallpox some 40 years ago. Today, only 56% of all MDR-TB patients worldwide are successfully treated.

Q: As already mentioned, the TB pathogen was discovered by Robert Koch. How did this come about?

Gerste: Along with cholera, TB was a great epidemic of the 19th century. For an ambitious researcher like Robert Koch, who had made a name for himself with the discovery of anthrax in 1876, there was no more rewarding goal than to find the cause of this infectious disease, which claimed the lives of many famous people such as Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Schiller, as well as many whose names are forgotten today.

[Dr.] Koch worked with his cultures for several years; the method of staining with methylene blue that was developed by the young Paul Ehrlich represented a breakthrough. To this method, [Dr.] Koch added a second, brownish dye. After countless experiments, this allowed slightly curved bacilli to be identified in tuberculous material under the microscope.

On the evening of March 24, 1882, [Dr.] Koch gave a lecture at the Institute of Physiology in Berlin with the title “Etiology of TB,” which sounded less than sensational on the invitations. One or two dozen participants had been expected, but more than one hundred came; numerous listeners had to make do with standing room behind the rows of chairs in the lecture hall. After a rather dry presentation ([Dr.] Koch was not a great orator nor a self-promoter), he presented his results to those present.

His assistants had set up a series of microscopes in the lecture hall through which everyone could get a glimpse of this enemy of humanity: the tubercle bacillus. When [Dr.] Koch had finished his remarks, there was silence in the hall. There was no burst of applause; the audience was too deeply aware that they had witnessed a historic moment. Paul Ehrlich later said that this evening had been the most significant scientific experience of his life. Over the next few weeks, the newspapers made a national hero out of Robert Koch, and the Emperor appointed him a Privy Councilor of the Government. The country doctor from Pomerania was now the figurehead of science in the young German Empire.

Q: Shortly after his discovery, [Dr.] Koch advertised a vaccination against TB with the active ingredient tuberculin. Was he able to convince with that too?

Gerste: No, this was the big flop, almost the disaster of a remarkable scientific career. The preparation of attenuated tubercle bacilli with water and glycerin not only did not prevent infection at all, it proved fatal for numerous users. However, tuberculin has survived in a modified form: as a tuberculin test, in which a characteristic skin rash indicates that a tested person has already had contact with the Mycobacterium.

Q: How have diagnostic options and treatment of the disease evolved since Robert Koch’s lifetime?

Gerste: A very decisive advance was made in diagnostics. With the rather accidental discovery of the rays soon named after him by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in the last days of 1895, it became possible to visualize the lung changes that tuberculosis caused in an unexpected way on living patients; the serial examinations for TB by X-rays were the logical consequence. Both scientists received Nobel Prizes, which were still new at the time, within a few years of each other: [Dr.] Röntgen in 1901 for physics, and [Dr]. Koch in 1905 for medicine and physiology.

Effective drugs were practically unavailable toward the end of the 19th century. For those who could afford it, however, a whole new world of (hoped-for or perceived) healing from “consumption” opened up: the sanatorium, located high in the mountains, surrounded by “fresh air.” The most famous of these climatic health resorts is probably Davos. It is no disrespect to the Swiss Confederation, which I hold in high esteem, to point out that Switzerland owes its high status as a tourist destination and thus its prosperity in part to TB.

Q: Things were quite different in earlier times. Until 250 years ago, the hopes of many patients rested on the medieval healing method of the “royal touch.” What’s that all about?

Gerste: In the Middle Ages, a “healing method” emerged from which not only lepers and other seriously ill people but also those suffering from consumption expected to be saved: the “royal touch,” which was first described by the Frankish king Clovis in 496. This ceremony was based on the idea that the king or queen, anointed by God, could improve or even cure the ailment of a sick person through a brief touch.

With the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, this act, during which thousands often gathered in front of the ruler’s residence, was practiced on a large scale. The sufferers passed by the anointed ruler as if in a procession and were briefly touched by him or her. The extremely few “successes” were of course exploited by royal propaganda to proclaim the blessing that the reign of the king or queen meant for the country. But on those who nevertheless fell victim to TB or another ailment, the chroniclers remained silent.

Charles II of England, who ruled from 1660 to 1685 during the Restoration after the English Civil War, is said to have touched 92,102 sick people during this period, according to contemporary counts. The record for a single day’s performance is probably held by Louis XVI of France, who is said to have touched a total of 2,400 sufferers on June 14, 1775. Some of them may have stood and cheered in the Paris crowd 18 years later as the king climbed the steps to the guillotine.

Q: Another invention associated with TB diagnosis is the stethoscope. How did it come about?

Gerste: A young physician named René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec had already experienced the importance of diagnosing TB in his student years. His teacher in Paris was Xavier Bichat, considered the founder of histology, who died of TB in [Dr.] Laënnec’s second year at the age of only 30. [Dr.] Laënnec was a devotee of auscultation and made it work with a massively overweight patient by rolling up a sheet of paper, then placing this on the woman’s thorax to listen to her heart sounds. He developed the idea further and built a hollow wooden tube with a metal earpiece. In 1818, he presented the device at the meeting of the Academy of Sciences in Paris; he called it a stethoscope. He used his new instrument primarily to auscultate the lungs of patients with TB and distinguished the sounds of TB cavities from those of other lung diseases such as pneumonia and emphysema.

Q: Back to the present day: The WHO wants to eradicate TB once and for all. What are the hopes and fears in the fight against this disease?

Gerste: There is no doubt that we are currently taking a step backwards in these efforts, and this is not only due to multiresistant pathogens. Especially in poorer countries particularly affected by TB, treatment and screening programs have been disrupted by lockdown measures targeting COVID-19. The WHO suspects that in the first pandemic year, 2020, about half a million additional people may have died from TB because they never received a diagnosis.

Dr. Gerste, born in 1957, is a physician and historian. Dr. Gerste has lived for many years as a correspondent and book author in Washington, D.C., where he writes primarily for the New Journal of Zürich, the FAS, Back Then, the German Medical Journal, and other academic journals.

This article was translated from Coliquio.

Almost forgotten today, tuberculosis is still one of the deadliest infectious diseases in the world. In an interview with Coliquio, Ronald D. Gerste, MD, PhD, an ophthalmologist and historian, looked back on this disease’s eventful history, which encompasses outstanding discoveries and catastrophic failures in diagnosis and treatment from the Middle Ages to the present day.

Under different names, TB has affected mankind for millennia. One of these names was the “aesthetic disease,” because it led to weight loss and pallor in the younger patients that it often affected. This was considered the ideal of beauty in the Victorian era. Many celebrities suffered from the disease, including poets and artists such as Friedrich Schiller, Lord Byron, and the Bronte family. As recently as the early 1990s, the disease almost changed world history, because Nelson Mandela became ill before the negotiations that led to the end of apartheid in South Africa.

Today, the global community is still not on track to meet its self-imposed targets for controlling the infectious disease, as reported by the World Health Organization on World TB Day in late March. Children and young people are the leading victims. In 2020 alone, 1.1 million children and adolescents under age 15 years were infected with TB, and 226,000 died of the disease, according to the WHO.

Q: Nelson Mandela was ill with tuberculosis during his imprisonment. How did the disease manifest itself in the future Nobel Peace Prize winner, and what is known about the treatment?

Ronald D. Gerste: Nelson Mandela contracted tuberculosis in 1988. At that time, he was 70 years old and had been in prison for 26 years. The disease presented in him with the almost classic symptom: He was coughing up blood and was also increasingly fatigued and losing weight. After doctors initially suspected a viral infection, but then TB was proven, he was treated with medication, and fluid was also drained from his lungs. [Mr.] Mandela was hospitalized for six weeks at Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town, the second largest hospital in South Africa. The therapy worked well, but [Mr.] Mandela’s lungs remained damaged. He was subsequently prone to pneumonia and was repeatedly hospitalized for pneumonia in 2012 and 2013.

Q: Mandela was lucky that the treatment worked for him. A few years later, the first antibiotic-resistant pathogen strains developed. How did medical research respond to this development?

Gerste: The emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR) strains of the pathogen prompted the WHO to declare a “global health emergency” in 1993. Three years later, World TB Day was proclaimed to raise awareness of the threat posed by this disease, which has been known since ancient times. It always takes place on March 24, the day in 1882 when Robert Koch gave his famous lecture in Berlin in which he announced the discovery of the pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Medical research has introduced new drugs into TB therapy, such as bedaquiline and delamanid. But MDR tuberculosis therapy remains a global challenge and has diminished hopes of eradicating tuberculosis, as we did with smallpox some 40 years ago. Today, only 56% of all MDR-TB patients worldwide are successfully treated.

Q: As already mentioned, the TB pathogen was discovered by Robert Koch. How did this come about?

Gerste: Along with cholera, TB was a great epidemic of the 19th century. For an ambitious researcher like Robert Koch, who had made a name for himself with the discovery of anthrax in 1876, there was no more rewarding goal than to find the cause of this infectious disease, which claimed the lives of many famous people such as Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Schiller, as well as many whose names are forgotten today.

[Dr.] Koch worked with his cultures for several years; the method of staining with methylene blue that was developed by the young Paul Ehrlich represented a breakthrough. To this method, [Dr.] Koch added a second, brownish dye. After countless experiments, this allowed slightly curved bacilli to be identified in tuberculous material under the microscope.

On the evening of March 24, 1882, [Dr.] Koch gave a lecture at the Institute of Physiology in Berlin with the title “Etiology of TB,” which sounded less than sensational on the invitations. One or two dozen participants had been expected, but more than one hundred came; numerous listeners had to make do with standing room behind the rows of chairs in the lecture hall. After a rather dry presentation ([Dr.] Koch was not a great orator nor a self-promoter), he presented his results to those present.

His assistants had set up a series of microscopes in the lecture hall through which everyone could get a glimpse of this enemy of humanity: the tubercle bacillus. When [Dr.] Koch had finished his remarks, there was silence in the hall. There was no burst of applause; the audience was too deeply aware that they had witnessed a historic moment. Paul Ehrlich later said that this evening had been the most significant scientific experience of his life. Over the next few weeks, the newspapers made a national hero out of Robert Koch, and the Emperor appointed him a Privy Councilor of the Government. The country doctor from Pomerania was now the figurehead of science in the young German Empire.

Q: Shortly after his discovery, [Dr.] Koch advertised a vaccination against TB with the active ingredient tuberculin. Was he able to convince with that too?

Gerste: No, this was the big flop, almost the disaster of a remarkable scientific career. The preparation of attenuated tubercle bacilli with water and glycerin not only did not prevent infection at all, it proved fatal for numerous users. However, tuberculin has survived in a modified form: as a tuberculin test, in which a characteristic skin rash indicates that a tested person has already had contact with the Mycobacterium.

Q: How have diagnostic options and treatment of the disease evolved since Robert Koch’s lifetime?

Gerste: A very decisive advance was made in diagnostics. With the rather accidental discovery of the rays soon named after him by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen in the last days of 1895, it became possible to visualize the lung changes that tuberculosis caused in an unexpected way on living patients; the serial examinations for TB by X-rays were the logical consequence. Both scientists received Nobel Prizes, which were still new at the time, within a few years of each other: [Dr.] Röntgen in 1901 for physics, and [Dr]. Koch in 1905 for medicine and physiology.

Effective drugs were practically unavailable toward the end of the 19th century. For those who could afford it, however, a whole new world of (hoped-for or perceived) healing from “consumption” opened up: the sanatorium, located high in the mountains, surrounded by “fresh air.” The most famous of these climatic health resorts is probably Davos. It is no disrespect to the Swiss Confederation, which I hold in high esteem, to point out that Switzerland owes its high status as a tourist destination and thus its prosperity in part to TB.

Q: Things were quite different in earlier times. Until 250 years ago, the hopes of many patients rested on the medieval healing method of the “royal touch.” What’s that all about?

Gerste: In the Middle Ages, a “healing method” emerged from which not only lepers and other seriously ill people but also those suffering from consumption expected to be saved: the “royal touch,” which was first described by the Frankish king Clovis in 496. This ceremony was based on the idea that the king or queen, anointed by God, could improve or even cure the ailment of a sick person through a brief touch.

With the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, this act, during which thousands often gathered in front of the ruler’s residence, was practiced on a large scale. The sufferers passed by the anointed ruler as if in a procession and were briefly touched by him or her. The extremely few “successes” were of course exploited by royal propaganda to proclaim the blessing that the reign of the king or queen meant for the country. But on those who nevertheless fell victim to TB or another ailment, the chroniclers remained silent.

Charles II of England, who ruled from 1660 to 1685 during the Restoration after the English Civil War, is said to have touched 92,102 sick people during this period, according to contemporary counts. The record for a single day’s performance is probably held by Louis XVI of France, who is said to have touched a total of 2,400 sufferers on June 14, 1775. Some of them may have stood and cheered in the Paris crowd 18 years later as the king climbed the steps to the guillotine.

Q: Another invention associated with TB diagnosis is the stethoscope. How did it come about?

Gerste: A young physician named René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec had already experienced the importance of diagnosing TB in his student years. His teacher in Paris was Xavier Bichat, considered the founder of histology, who died of TB in [Dr.] Laënnec’s second year at the age of only 30. [Dr.] Laënnec was a devotee of auscultation and made it work with a massively overweight patient by rolling up a sheet of paper, then placing this on the woman’s thorax to listen to her heart sounds. He developed the idea further and built a hollow wooden tube with a metal earpiece. In 1818, he presented the device at the meeting of the Academy of Sciences in Paris; he called it a stethoscope. He used his new instrument primarily to auscultate the lungs of patients with TB and distinguished the sounds of TB cavities from those of other lung diseases such as pneumonia and emphysema.

Q: Back to the present day: The WHO wants to eradicate TB once and for all. What are the hopes and fears in the fight against this disease?

Gerste: There is no doubt that we are currently taking a step backwards in these efforts, and this is not only due to multiresistant pathogens. Especially in poorer countries particularly affected by TB, treatment and screening programs have been disrupted by lockdown measures targeting COVID-19. The WHO suspects that in the first pandemic year, 2020, about half a million additional people may have died from TB because they never received a diagnosis.

Dr. Gerste, born in 1957, is a physician and historian. Dr. Gerste has lived for many years as a correspondent and book author in Washington, D.C., where he writes primarily for the New Journal of Zürich, the FAS, Back Then, the German Medical Journal, and other academic journals.

This article was translated from Coliquio.

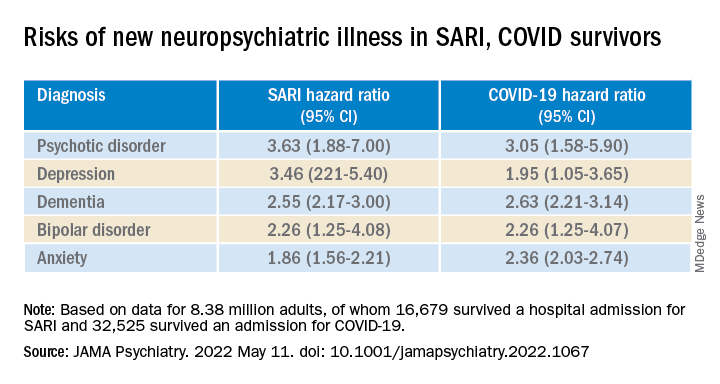

Neuropsychiatric risks of COVID-19: New data

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

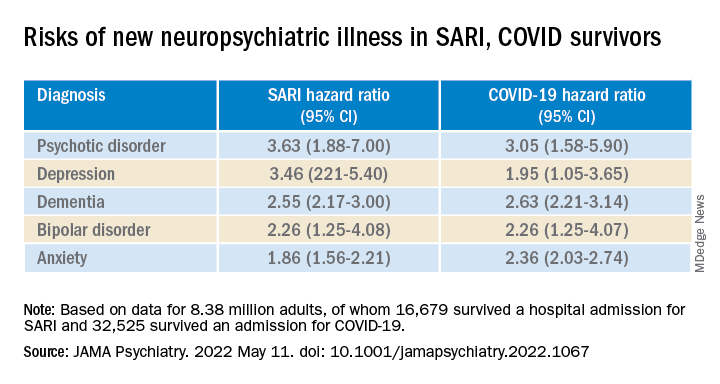

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

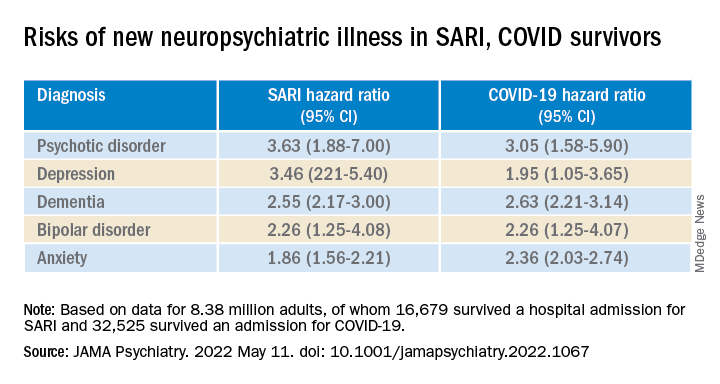

The neuropsychiatric ramifications of severe COVID-19 infection appear to be no different than for other severe acute respiratory infections (SARI).

This suggests that disease severity, rather than pathogen, is the most relevant factor in new-onset neuropsychiatric illness, the investigators note.

The risk of new-onset neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection are “substantial, but similar to those after other severe respiratory infections,” study investigator Peter Watkinson, MD, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, and John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Significant mental health burden

Research has shown a significant burden of neuropsychological illness after severe COVID-19 infection. However, it’s unclear how this risk compares to SARI.

To investigate, Dr. Watkinson and colleagues evaluated electronic health record data on more than 8.3 million adults, including 16,679 (0.02%) who survived a hospital admission for SARI and 32,525 (0.03%) who survived a hospital stay for COVID-19.

Compared with the remaining population, risks of new anxiety disorder, dementia, psychotic disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder diagnoses were significantly and similarly increased in adults surviving hospitalization for either COVID-19 or SARI.

Compared with the wider population, survivors of severe SARI or COVID-19 were also at increased risk of starting treatment with antidepressants, hypnotics/anxiolytics, or antipsychotics.

When comparing survivors of SARI hospitalization to survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization, no significant differences were observed in the postdischarge rates of new-onset anxiety disorder, dementia, depression, or bipolar affective disorder.

The SARI and COVID groups also did not differ in terms of their postdischarge risks of antidepressant or hypnotic/anxiolytic use, but the COVID survivors had a 20% lower risk of starting an antipsychotic.

“In this cohort study, SARI were found to be associated with significant postacute neuropsychiatric morbidity, for which COVID-19 is not distinctly different,” Dr. Watkinson and colleagues write.

“These results may help refine our understanding of the post–severe COVID-19 phenotype and may inform post-discharge support for patients requiring hospital-based and intensive care for SARI regardless of causative pathogen,” they write.

Caveats, cautionary notes

Kevin McConway, PhD, emeritus professor of applied statistics at the Open University in Milton Keynes, England, described the study as “impressive.” However, he pointed out that the study’s observational design is a limitation.

“One can never be absolutely certain about the interpretation of findings of an observational study. What the research can’t tell us is what caused the increased psychiatric risks for people hospitalized with COVID-19 or some other serious respiratory disease,” Dr. McConway said.

“It can’t tell us what might happen in the future, when, we all hope, many fewer are being hospitalized with COVID-19 than was the case in those first two waves, and the current backlog of provision of some health services has decreased,” he added.

“So we can’t just say that, in general, serious COVID-19 has much the same neuropsychiatric consequences as other very serious respiratory illness. Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t,” Dr. McConway cautioned.

Max Taquet, PhD, with the University of Oxford, noted that the study is limited to hospitalized adult patients, leaving open the question of risk in nonhospitalized individuals – which is the overwhelming majority of patients with COVID-19 – or in children.

Whether the neuropsychiatric risks have remained the same since the emergence of the Omicron variant also remains “an open question since all patients in this study were diagnosed before July 2021,” Dr. Taquet said in statement.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the John Fell Oxford University Press Research Fund, the Oxford Wellcome Institutional Strategic Support Fund and Cancer Research UK, through the Cancer Research UK Oxford Centre. Dr. Watkinson disclosed grants from the National Institute for Health Research and Sensyne Health outside the submitted work; and serving as chief medical officer for Sensyne Health prior to this work, as well as holding shares in the company. Dr. McConway is a trustee of the UK Science Media Centre and a member of its advisory committee. His comments were provided in his capacity as an independent professional statistician. Dr. Taquet has worked on similar studies trying to identify, quantify, and specify the neurological and psychiatric consequences of COVID-19.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Most COVID-19 survivors return to work within 2 years

The burden of persistent COVID-19 symptoms appeared to improve over time, but a higher percentage of former patients reported poor health, compared with the general population. This suggests that some patients need more time to completely recover from COVID-19, wrote the authors of the new study, which was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Previous research has shown that the health effects of COVID-19 last for up to a year, but data from longer-term studies are limited, said Lixue Huang, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, one of the study authors, and colleagues.

Methods and results

In the new study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,192 adult patients who were discharged from the hospital after surviving COVID-19 between Jan. 7, 2020, and May 29, 2020. The researchers measured the participants’ health outcomes at 6 months, 12 months, and 2 years after their onset of symptoms. A community-based dataset of 3,383 adults with no history of COVID-19 served as controls to measure the recovery of the COVID-19 patients. The median age of the patients at the time of hospital discharge was 57 years, and 46% were women. The median follow-up time after the onset of symptoms was 185 days, 349 days, and 685 days for the 6-month, 12-month, and 2-year visits, respectively. The researchers measured health outcomes using a 6-min walking distance (6MWD) test, laboratory tests, and questionnaires about symptoms, mental health, health-related quality of life, returning to work, and health care use since leaving the hospital.

Overall, the proportion of COVID-19 survivors with at least one symptom decreased from 68% at 6 months to 55% at 2 years (P < .0001). The most frequent symptoms were fatigue and muscle weakness, reported by approximately one-third of the patients (31%); sleep problems also were reported by 31% of the patients.

The proportion of individuals with poor results on the 6MWD decreased continuously over time, not only in COVID-19 survivors overall, but also in three subgroups of varying initial disease severity. Of the 494 survivors who reported working before becoming ill, 438 (89%) had returned to their original jobs 2 years later. The most common reasons for not returning to work were decreased physical function, unwillingness to return, and unemployment, the researchers noted.

However, at 2 years, COVID-19 survivors reported more pain and discomfort, as well as more anxiety and depression, compared with the controls (23% vs. 5% and 12% vs. 5%, respectively).

In addition, significantly more survivors who needed high levels of respiratory support while hospitalized had lung diffusion impairment (65%), reduced residual volume (62%), and total lung capacity (39%), compared with matched controls (36%, 20%, and 6%, respectively) at 2 years.

Long-COVID concerns

Approximately half of the survivors had symptoms of long COVID at 2 years. These individuals were more likely to report pain or discomfort or anxiety or depression, as well as mobility problems, compared to survivors without long COVID. Participants with long-COVID symptoms were more than twice as likely to have an outpatient clinic visit (odds ratio, 2.82), and not quite twice as likely to be rehospitalized (OR, 1.64).

“We found that [health-related quality of life], exercise capacity, and mental health continued to improve throughout the 2 years regardless of initial disease severity, but about half still had symptomatic sequelae at 2 years,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

Findings can inform doctor-patient discussions

“We are increasingly recognizing that the health effects of COVID-19 may persist beyond acute illness, therefore this is a timely study to assess the long-term impact of COVID-19 with a long follow-up period,” said Suman Pal, MD, an internal medicine physician at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in an interview.

The findings are consistent with the existing literature, said Dr. Pal, who was not involved in the study. The data from the study “can help clinicians have discussions regarding expected recovery and long-term prognosis for patients with COVID-19,” he noted.

What patients should know is that “studies such as this can help COVID-19 survivors understand and monitor persistent symptoms they may experience, and bring them to the attention of their clinicians,” said Dr. Pal.

However, “As a single-center study with high attrition of subjects during the study period, the findings may not be generalizable,” Dr. Pal emphasized. “Larger-scale studies and patient registries distributed over different geographical areas and time periods will help obtain a better understanding of the nature and prevalence of long COVID,” he said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of formerly hospitalized controls with respiratory infections other than COVID-19 to determine which outcomes are COVID-19 specific, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of data from only patients at a single center, and from the early stages of the pandemic, as well as the use of self-reports for comorbidities and health outcomes, they said.

However, the results represent the longest-known published longitudinal follow-up of patients who recovered from acute COVID-19, the researchers emphasized. Study strengths included the large sample size, longitudinal design, and long-term follow-up with non-COVID controls to determine outcomes. The researchers noted their plans to conduct annual follow-ups in the current study population. They added that more research is needed to explore rehabilitation programs to promote recovery for COVID-19 survivors and to reduce the effects of long COVID.

The study was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, National Key Research and Development Program of China, National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, China Evergrande Group, Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical, Ping An Insurance (Group), and New Sunshine Charity Foundation. The researchers and Dr. Pal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

This article was updated on 5/16/2022.

The burden of persistent COVID-19 symptoms appeared to improve over time, but a higher percentage of former patients reported poor health, compared with the general population. This suggests that some patients need more time to completely recover from COVID-19, wrote the authors of the new study, which was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Previous research has shown that the health effects of COVID-19 last for up to a year, but data from longer-term studies are limited, said Lixue Huang, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, one of the study authors, and colleagues.

Methods and results

In the new study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,192 adult patients who were discharged from the hospital after surviving COVID-19 between Jan. 7, 2020, and May 29, 2020. The researchers measured the participants’ health outcomes at 6 months, 12 months, and 2 years after their onset of symptoms. A community-based dataset of 3,383 adults with no history of COVID-19 served as controls to measure the recovery of the COVID-19 patients. The median age of the patients at the time of hospital discharge was 57 years, and 46% were women. The median follow-up time after the onset of symptoms was 185 days, 349 days, and 685 days for the 6-month, 12-month, and 2-year visits, respectively. The researchers measured health outcomes using a 6-min walking distance (6MWD) test, laboratory tests, and questionnaires about symptoms, mental health, health-related quality of life, returning to work, and health care use since leaving the hospital.

Overall, the proportion of COVID-19 survivors with at least one symptom decreased from 68% at 6 months to 55% at 2 years (P < .0001). The most frequent symptoms were fatigue and muscle weakness, reported by approximately one-third of the patients (31%); sleep problems also were reported by 31% of the patients.

The proportion of individuals with poor results on the 6MWD decreased continuously over time, not only in COVID-19 survivors overall, but also in three subgroups of varying initial disease severity. Of the 494 survivors who reported working before becoming ill, 438 (89%) had returned to their original jobs 2 years later. The most common reasons for not returning to work were decreased physical function, unwillingness to return, and unemployment, the researchers noted.

However, at 2 years, COVID-19 survivors reported more pain and discomfort, as well as more anxiety and depression, compared with the controls (23% vs. 5% and 12% vs. 5%, respectively).

In addition, significantly more survivors who needed high levels of respiratory support while hospitalized had lung diffusion impairment (65%), reduced residual volume (62%), and total lung capacity (39%), compared with matched controls (36%, 20%, and 6%, respectively) at 2 years.

Long-COVID concerns

Approximately half of the survivors had symptoms of long COVID at 2 years. These individuals were more likely to report pain or discomfort or anxiety or depression, as well as mobility problems, compared to survivors without long COVID. Participants with long-COVID symptoms were more than twice as likely to have an outpatient clinic visit (odds ratio, 2.82), and not quite twice as likely to be rehospitalized (OR, 1.64).

“We found that [health-related quality of life], exercise capacity, and mental health continued to improve throughout the 2 years regardless of initial disease severity, but about half still had symptomatic sequelae at 2 years,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

Findings can inform doctor-patient discussions

“We are increasingly recognizing that the health effects of COVID-19 may persist beyond acute illness, therefore this is a timely study to assess the long-term impact of COVID-19 with a long follow-up period,” said Suman Pal, MD, an internal medicine physician at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in an interview.

The findings are consistent with the existing literature, said Dr. Pal, who was not involved in the study. The data from the study “can help clinicians have discussions regarding expected recovery and long-term prognosis for patients with COVID-19,” he noted.

What patients should know is that “studies such as this can help COVID-19 survivors understand and monitor persistent symptoms they may experience, and bring them to the attention of their clinicians,” said Dr. Pal.

However, “As a single-center study with high attrition of subjects during the study period, the findings may not be generalizable,” Dr. Pal emphasized. “Larger-scale studies and patient registries distributed over different geographical areas and time periods will help obtain a better understanding of the nature and prevalence of long COVID,” he said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of formerly hospitalized controls with respiratory infections other than COVID-19 to determine which outcomes are COVID-19 specific, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of data from only patients at a single center, and from the early stages of the pandemic, as well as the use of self-reports for comorbidities and health outcomes, they said.

However, the results represent the longest-known published longitudinal follow-up of patients who recovered from acute COVID-19, the researchers emphasized. Study strengths included the large sample size, longitudinal design, and long-term follow-up with non-COVID controls to determine outcomes. The researchers noted their plans to conduct annual follow-ups in the current study population. They added that more research is needed to explore rehabilitation programs to promote recovery for COVID-19 survivors and to reduce the effects of long COVID.

The study was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, National Key Research and Development Program of China, National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, China Evergrande Group, Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical, Ping An Insurance (Group), and New Sunshine Charity Foundation. The researchers and Dr. Pal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

This article was updated on 5/16/2022.

The burden of persistent COVID-19 symptoms appeared to improve over time, but a higher percentage of former patients reported poor health, compared with the general population. This suggests that some patients need more time to completely recover from COVID-19, wrote the authors of the new study, which was published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Previous research has shown that the health effects of COVID-19 last for up to a year, but data from longer-term studies are limited, said Lixue Huang, MD, of Capital Medical University, Beijing, one of the study authors, and colleagues.

Methods and results

In the new study, the researchers reviewed data from 1,192 adult patients who were discharged from the hospital after surviving COVID-19 between Jan. 7, 2020, and May 29, 2020. The researchers measured the participants’ health outcomes at 6 months, 12 months, and 2 years after their onset of symptoms. A community-based dataset of 3,383 adults with no history of COVID-19 served as controls to measure the recovery of the COVID-19 patients. The median age of the patients at the time of hospital discharge was 57 years, and 46% were women. The median follow-up time after the onset of symptoms was 185 days, 349 days, and 685 days for the 6-month, 12-month, and 2-year visits, respectively. The researchers measured health outcomes using a 6-min walking distance (6MWD) test, laboratory tests, and questionnaires about symptoms, mental health, health-related quality of life, returning to work, and health care use since leaving the hospital.

Overall, the proportion of COVID-19 survivors with at least one symptom decreased from 68% at 6 months to 55% at 2 years (P < .0001). The most frequent symptoms were fatigue and muscle weakness, reported by approximately one-third of the patients (31%); sleep problems also were reported by 31% of the patients.

The proportion of individuals with poor results on the 6MWD decreased continuously over time, not only in COVID-19 survivors overall, but also in three subgroups of varying initial disease severity. Of the 494 survivors who reported working before becoming ill, 438 (89%) had returned to their original jobs 2 years later. The most common reasons for not returning to work were decreased physical function, unwillingness to return, and unemployment, the researchers noted.

However, at 2 years, COVID-19 survivors reported more pain and discomfort, as well as more anxiety and depression, compared with the controls (23% vs. 5% and 12% vs. 5%, respectively).

In addition, significantly more survivors who needed high levels of respiratory support while hospitalized had lung diffusion impairment (65%), reduced residual volume (62%), and total lung capacity (39%), compared with matched controls (36%, 20%, and 6%, respectively) at 2 years.

Long-COVID concerns

Approximately half of the survivors had symptoms of long COVID at 2 years. These individuals were more likely to report pain or discomfort or anxiety or depression, as well as mobility problems, compared to survivors without long COVID. Participants with long-COVID symptoms were more than twice as likely to have an outpatient clinic visit (odds ratio, 2.82), and not quite twice as likely to be rehospitalized (OR, 1.64).

“We found that [health-related quality of life], exercise capacity, and mental health continued to improve throughout the 2 years regardless of initial disease severity, but about half still had symptomatic sequelae at 2 years,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

Findings can inform doctor-patient discussions

“We are increasingly recognizing that the health effects of COVID-19 may persist beyond acute illness, therefore this is a timely study to assess the long-term impact of COVID-19 with a long follow-up period,” said Suman Pal, MD, an internal medicine physician at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, in an interview.

The findings are consistent with the existing literature, said Dr. Pal, who was not involved in the study. The data from the study “can help clinicians have discussions regarding expected recovery and long-term prognosis for patients with COVID-19,” he noted.

What patients should know is that “studies such as this can help COVID-19 survivors understand and monitor persistent symptoms they may experience, and bring them to the attention of their clinicians,” said Dr. Pal.

However, “As a single-center study with high attrition of subjects during the study period, the findings may not be generalizable,” Dr. Pal emphasized. “Larger-scale studies and patient registries distributed over different geographical areas and time periods will help obtain a better understanding of the nature and prevalence of long COVID,” he said.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of formerly hospitalized controls with respiratory infections other than COVID-19 to determine which outcomes are COVID-19 specific, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of data from only patients at a single center, and from the early stages of the pandemic, as well as the use of self-reports for comorbidities and health outcomes, they said.

However, the results represent the longest-known published longitudinal follow-up of patients who recovered from acute COVID-19, the researchers emphasized. Study strengths included the large sample size, longitudinal design, and long-term follow-up with non-COVID controls to determine outcomes. The researchers noted their plans to conduct annual follow-ups in the current study population. They added that more research is needed to explore rehabilitation programs to promote recovery for COVID-19 survivors and to reduce the effects of long COVID.

The study was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, National Key Research and Development Program of China, National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Major Projects of National Science and Technology on New Drug Creation and Development of Pulmonary Tuberculosis, China Evergrande Group, Jack Ma Foundation, Sino Biopharmaceutical, Ping An Insurance (Group), and New Sunshine Charity Foundation. The researchers and Dr. Pal had no financial conflicts to disclose.

This article was updated on 5/16/2022.

FROM THE LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease can be challenging to treat

Living in coastal areas of Florida and California has great appeal for many, with the warm, sunny climate and nearby fresh water and salt water.

But, unknown to many, those balmy coasts also carry the risk of infection from nontuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria (NTM). Unlike its relative, tuberculosis, NTM is not transmitted from person to person, with one exception: patients with cystic fibrosis.

It is estimated that there were 181,000 people with NTM lung disease in the U.S. in 2015, and according to one study, the incidence is increasing by 8.2% annually among those aged 65 years and older. But NTM doesn’t only affect the elderly; it’s estimated that 31% of all NTM patients are younger than 65 years.