User login

Managing patients who are somatizing

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Nautical metaphors build physician resilience, beat burnout

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Linda L.M. Worley, MD, was stunned when a meeting she’d requested with her supervisor to address a shortage of beds turned into a rebuke.

“You’re on the tenure track, Linda. If you want to keep your job 6 years from now, you’d best pick up the pace. You need to see 20 private patients a week, and get moving on your research and publications,” Dr. Worley remembers the supervisor saying. At the time, she was a 32-year-old mother of two, wife, academic faculty physician, and sole attending running a general hospital consultation liaison psychiatry department and the college of medicine student mental health service. She also worked as the 24/7 on-call psychiatrist for a week at a time, said Dr. Worley, now a staff psychiatrist in the Fayetteville, Ark., Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks and chief mental health officer for South Central VA Health Care Network.

Over the decades of an academic medical career complete with tenure, and dozens of published articles and book chapters, Dr. Worley has developed a system for achieving success while avoiding burnout, based on nautical references. In a session cofacilitated by Cynthia M. Stonnington, MD, chair of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Clinic’s campus in Scottsdale, Ariz., Dr. Worley presented her tips for self-care at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“I use the nautical framework as a bio-psycho-social-spiritual model,” Dr. Worley said in an interview. “I teach it to medical students; I teach it to residents; I teach it to distressed physicians. I even teach it to patients when I am explaining a framework for a necessary treatment approach. With sailing, you have to stay in balance. That’s the same with taking good care of ourselves so we are less likely to get sick physically and mentally,” said Dr. Worley, who commutes to Nashville, Tenn., several times a year as part of her appointment as an adjunct professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University.

Her “Smooth Sailing Life” seminars have evolved over the past 20 years and are rooted in her training in psychosomatic medicine, which she said emphasizes the complexity of the entire person. “It’s about the biology and about the emotions, and the bridge between them,” according to Dr. Worley, who has a website, SmoothSailingLife.com, and is working on a book aimed at helping to meet what she said has been a steadily growing thirst for her approach to developing resilience.

“I am not studying anyone, but I am helping people to self-diagnose. I teach people how to avoid having to see a psychiatrist or a mental health provider but also to feel good about reaching out for help when necessary,” she said. “Life is far too short to suffer needlessly.”

In the interview, Dr. Worley said she adapts her presentations to the venue and the time allowed. Key aspects of her system include:

• Care for your yacht, which is the body, including the brain. “You only get one, and if you’re going to have a chance of winning the regatta, you have to take care of it. This means getting good sleep, nutrition, exercise, preventive care, rest, and rejuvenation, including vacation,” Dr. Worley said.

• Chart your course; have a navigational plan that includes your life goals and aspirations. Identify and rely upon “landmarks,” such as being a good spouse, mother, physician, or friend for the most authentic definition of personal success. “These are like buoys that keep us sailing in the right direction,” she said.

• Reef in your sails, meaning mind the “winds that come at us from every side,” she said. This includes triaging tasks and not letting perfectionism get in the way. “Perfectionists take too long to tack; they don’t know when it’s time to turn in the other direction,” she said. “If you want to finish the race, you have to do the best you can in the time you have.” This was the lesson Dr. Worley said she learned that day when she was a young physician feeling overwhelmed.

• Empty your bilge, the nautical term for removing waste water from within the hull. Dr. Worley uses this as a metaphor for identifying and expressing negative emotions of fear, anxiety, sadness, and frustration. “These vital emotions are giving us important messages. It is important to recognize that they are present. Name and accept them, and understand what they are trying to tell us. Is it a symptom of an underlying illness that needs treatment? A conflict in a relationship? A need not being met? Are you living your deepest values? Express the emotions and sort through the best response,” she said. “It’s all part of emotional intelligence.”

• Keep an even keel, which is Dr. Worley’s way of stating the importance of being connected to love and to living your deepest values. “The keel is your character, your connection to meaning, a spiritual connection. In medicine, we shy away from that. I have only lately ventured into talking about this,” she said, noting that this connection can come in numerous ways, such as meditation, and being in nature or with animals. “It’s very personal. It’s hard to quantify, but I have witnessed it and its healing power within the therapeutic alliance.”

In break-out sessions during her well-attended talk at the meeting, Dr. Worley listened as psychiatrists of all levels of experience and responsibility, ranging from medical directors to those in private community practice, shared the kinds of concerns she said she often encounters in her role as a core faculty member of the Program for Distressed Physicians at the Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health.

“Changes in medicine have been so frustrating; physicians are at their wits’ end. We don’t recruit people into medicine because they have a skill set for expressing their emotions, or taking care of themselves, or dealing with conflict,” she said. “That’s okay. They can learn it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Linda L.M. Worley, MD, was stunned when a meeting she’d requested with her supervisor to address a shortage of beds turned into a rebuke.

“You’re on the tenure track, Linda. If you want to keep your job 6 years from now, you’d best pick up the pace. You need to see 20 private patients a week, and get moving on your research and publications,” Dr. Worley remembers the supervisor saying. At the time, she was a 32-year-old mother of two, wife, academic faculty physician, and sole attending running a general hospital consultation liaison psychiatry department and the college of medicine student mental health service. She also worked as the 24/7 on-call psychiatrist for a week at a time, said Dr. Worley, now a staff psychiatrist in the Fayetteville, Ark., Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks and chief mental health officer for South Central VA Health Care Network.

Over the decades of an academic medical career complete with tenure, and dozens of published articles and book chapters, Dr. Worley has developed a system for achieving success while avoiding burnout, based on nautical references. In a session cofacilitated by Cynthia M. Stonnington, MD, chair of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Clinic’s campus in Scottsdale, Ariz., Dr. Worley presented her tips for self-care at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“I use the nautical framework as a bio-psycho-social-spiritual model,” Dr. Worley said in an interview. “I teach it to medical students; I teach it to residents; I teach it to distressed physicians. I even teach it to patients when I am explaining a framework for a necessary treatment approach. With sailing, you have to stay in balance. That’s the same with taking good care of ourselves so we are less likely to get sick physically and mentally,” said Dr. Worley, who commutes to Nashville, Tenn., several times a year as part of her appointment as an adjunct professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University.

Her “Smooth Sailing Life” seminars have evolved over the past 20 years and are rooted in her training in psychosomatic medicine, which she said emphasizes the complexity of the entire person. “It’s about the biology and about the emotions, and the bridge between them,” according to Dr. Worley, who has a website, SmoothSailingLife.com, and is working on a book aimed at helping to meet what she said has been a steadily growing thirst for her approach to developing resilience.

“I am not studying anyone, but I am helping people to self-diagnose. I teach people how to avoid having to see a psychiatrist or a mental health provider but also to feel good about reaching out for help when necessary,” she said. “Life is far too short to suffer needlessly.”

In the interview, Dr. Worley said she adapts her presentations to the venue and the time allowed. Key aspects of her system include:

• Care for your yacht, which is the body, including the brain. “You only get one, and if you’re going to have a chance of winning the regatta, you have to take care of it. This means getting good sleep, nutrition, exercise, preventive care, rest, and rejuvenation, including vacation,” Dr. Worley said.

• Chart your course; have a navigational plan that includes your life goals and aspirations. Identify and rely upon “landmarks,” such as being a good spouse, mother, physician, or friend for the most authentic definition of personal success. “These are like buoys that keep us sailing in the right direction,” she said.

• Reef in your sails, meaning mind the “winds that come at us from every side,” she said. This includes triaging tasks and not letting perfectionism get in the way. “Perfectionists take too long to tack; they don’t know when it’s time to turn in the other direction,” she said. “If you want to finish the race, you have to do the best you can in the time you have.” This was the lesson Dr. Worley said she learned that day when she was a young physician feeling overwhelmed.

• Empty your bilge, the nautical term for removing waste water from within the hull. Dr. Worley uses this as a metaphor for identifying and expressing negative emotions of fear, anxiety, sadness, and frustration. “These vital emotions are giving us important messages. It is important to recognize that they are present. Name and accept them, and understand what they are trying to tell us. Is it a symptom of an underlying illness that needs treatment? A conflict in a relationship? A need not being met? Are you living your deepest values? Express the emotions and sort through the best response,” she said. “It’s all part of emotional intelligence.”

• Keep an even keel, which is Dr. Worley’s way of stating the importance of being connected to love and to living your deepest values. “The keel is your character, your connection to meaning, a spiritual connection. In medicine, we shy away from that. I have only lately ventured into talking about this,” she said, noting that this connection can come in numerous ways, such as meditation, and being in nature or with animals. “It’s very personal. It’s hard to quantify, but I have witnessed it and its healing power within the therapeutic alliance.”

In break-out sessions during her well-attended talk at the meeting, Dr. Worley listened as psychiatrists of all levels of experience and responsibility, ranging from medical directors to those in private community practice, shared the kinds of concerns she said she often encounters in her role as a core faculty member of the Program for Distressed Physicians at the Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health.

“Changes in medicine have been so frustrating; physicians are at their wits’ end. We don’t recruit people into medicine because they have a skill set for expressing their emotions, or taking care of themselves, or dealing with conflict,” she said. “That’s okay. They can learn it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Linda L.M. Worley, MD, was stunned when a meeting she’d requested with her supervisor to address a shortage of beds turned into a rebuke.

“You’re on the tenure track, Linda. If you want to keep your job 6 years from now, you’d best pick up the pace. You need to see 20 private patients a week, and get moving on your research and publications,” Dr. Worley remembers the supervisor saying. At the time, she was a 32-year-old mother of two, wife, academic faculty physician, and sole attending running a general hospital consultation liaison psychiatry department and the college of medicine student mental health service. She also worked as the 24/7 on-call psychiatrist for a week at a time, said Dr. Worley, now a staff psychiatrist in the Fayetteville, Ark., Veterans Health Care System of the Ozarks and chief mental health officer for South Central VA Health Care Network.

Over the decades of an academic medical career complete with tenure, and dozens of published articles and book chapters, Dr. Worley has developed a system for achieving success while avoiding burnout, based on nautical references. In a session cofacilitated by Cynthia M. Stonnington, MD, chair of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Clinic’s campus in Scottsdale, Ariz., Dr. Worley presented her tips for self-care at the annual meeting of the American College of Psychiatrists.

“I use the nautical framework as a bio-psycho-social-spiritual model,” Dr. Worley said in an interview. “I teach it to medical students; I teach it to residents; I teach it to distressed physicians. I even teach it to patients when I am explaining a framework for a necessary treatment approach. With sailing, you have to stay in balance. That’s the same with taking good care of ourselves so we are less likely to get sick physically and mentally,” said Dr. Worley, who commutes to Nashville, Tenn., several times a year as part of her appointment as an adjunct professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University.

Her “Smooth Sailing Life” seminars have evolved over the past 20 years and are rooted in her training in psychosomatic medicine, which she said emphasizes the complexity of the entire person. “It’s about the biology and about the emotions, and the bridge between them,” according to Dr. Worley, who has a website, SmoothSailingLife.com, and is working on a book aimed at helping to meet what she said has been a steadily growing thirst for her approach to developing resilience.

“I am not studying anyone, but I am helping people to self-diagnose. I teach people how to avoid having to see a psychiatrist or a mental health provider but also to feel good about reaching out for help when necessary,” she said. “Life is far too short to suffer needlessly.”

In the interview, Dr. Worley said she adapts her presentations to the venue and the time allowed. Key aspects of her system include:

• Care for your yacht, which is the body, including the brain. “You only get one, and if you’re going to have a chance of winning the regatta, you have to take care of it. This means getting good sleep, nutrition, exercise, preventive care, rest, and rejuvenation, including vacation,” Dr. Worley said.

• Chart your course; have a navigational plan that includes your life goals and aspirations. Identify and rely upon “landmarks,” such as being a good spouse, mother, physician, or friend for the most authentic definition of personal success. “These are like buoys that keep us sailing in the right direction,” she said.

• Reef in your sails, meaning mind the “winds that come at us from every side,” she said. This includes triaging tasks and not letting perfectionism get in the way. “Perfectionists take too long to tack; they don’t know when it’s time to turn in the other direction,” she said. “If you want to finish the race, you have to do the best you can in the time you have.” This was the lesson Dr. Worley said she learned that day when she was a young physician feeling overwhelmed.

• Empty your bilge, the nautical term for removing waste water from within the hull. Dr. Worley uses this as a metaphor for identifying and expressing negative emotions of fear, anxiety, sadness, and frustration. “These vital emotions are giving us important messages. It is important to recognize that they are present. Name and accept them, and understand what they are trying to tell us. Is it a symptom of an underlying illness that needs treatment? A conflict in a relationship? A need not being met? Are you living your deepest values? Express the emotions and sort through the best response,” she said. “It’s all part of emotional intelligence.”

• Keep an even keel, which is Dr. Worley’s way of stating the importance of being connected to love and to living your deepest values. “The keel is your character, your connection to meaning, a spiritual connection. In medicine, we shy away from that. I have only lately ventured into talking about this,” she said, noting that this connection can come in numerous ways, such as meditation, and being in nature or with animals. “It’s very personal. It’s hard to quantify, but I have witnessed it and its healing power within the therapeutic alliance.”

In break-out sessions during her well-attended talk at the meeting, Dr. Worley listened as psychiatrists of all levels of experience and responsibility, ranging from medical directors to those in private community practice, shared the kinds of concerns she said she often encounters in her role as a core faculty member of the Program for Distressed Physicians at the Vanderbilt Center for Professional Health.

“Changes in medicine have been so frustrating; physicians are at their wits’ end. We don’t recruit people into medicine because they have a skill set for expressing their emotions, or taking care of themselves, or dealing with conflict,” she said. “That’s okay. They can learn it.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS MEETING

Valbenazine for tardive dyskinesia

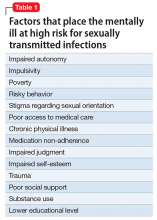

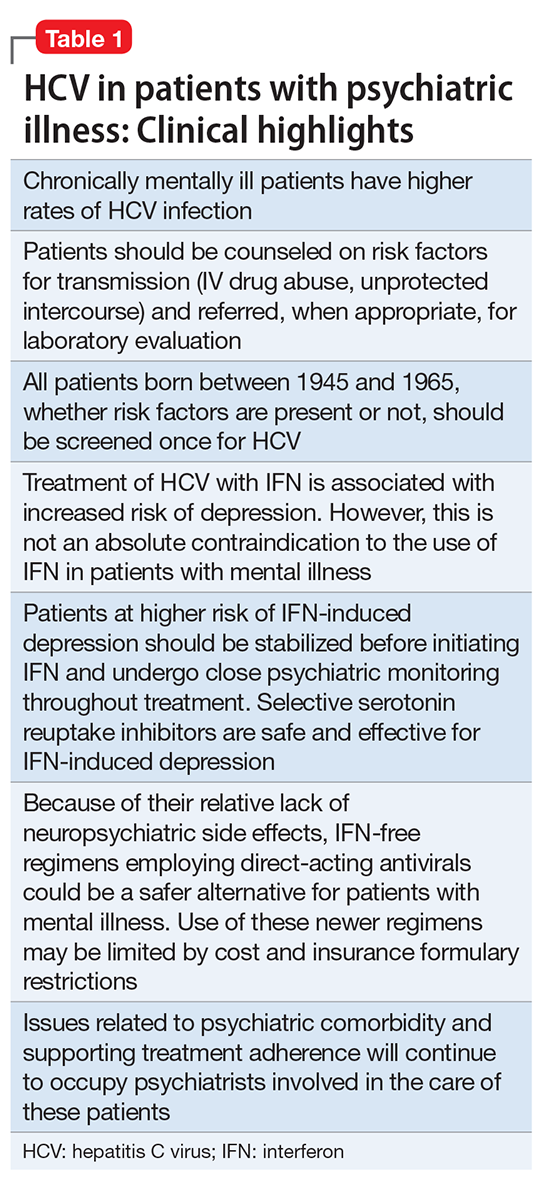

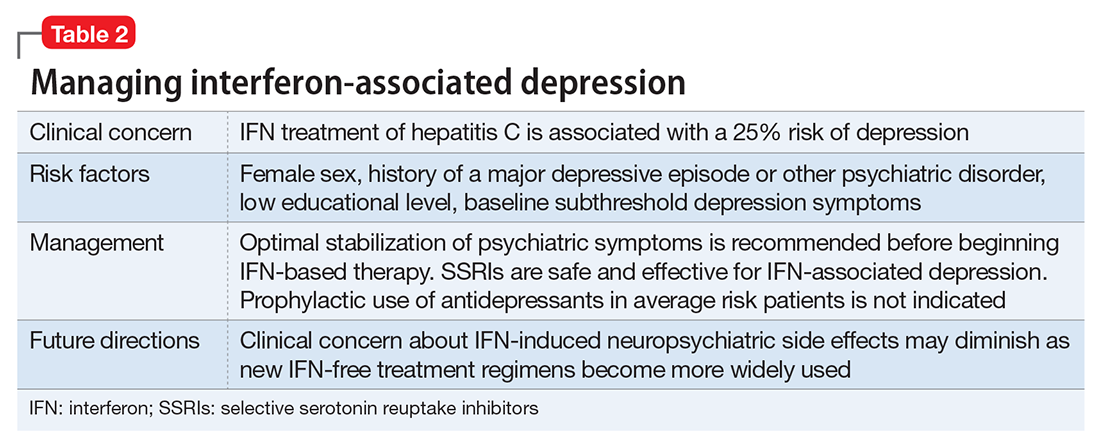

Despite improvements in the tolerability of antipsychotic medications, the development of tardive dyskinesia (TD) still is a significant area of concern; however, clinicians have had few treatment options. Valbenazine, a vesicular monoamine transport type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor, is the only FDA-approved medication for TD (Table 1).1 By modulating dopamine transport into presynaptic vesicles, synaptic dopamine release is decreased, thereby reducing the postsynaptic stimulation of D2 receptors and the severity of dyskinetic movements.

In the pivotal 6-week clinical trial, valbenazine significantly reduced TD severity as measured by Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) ratings.2 Study completion rates were high (87.6%), with only 2 dropouts because of adverse events in each of the placebo (n = 78) and 40-mg (n = 76) arms, and 3 in the 80-mg group (n = 80).

Before the development of valbenazine, tetrabenazine was the only effective option for treating TD. Despite tetrabenazine’s known efficacy for TD, it was not available in the United States until 2008 with the sole indication for movements related to Huntington’s disease. U.S. patients often were subjected to a litany of ineffective medications for TD, often at great expense. Moreover, tetrabenazine involved multiple daily dosing, required cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d, had significant tolerability issues, and a monthly cost of $8,000 to $10,000. The availability of an agent that is effective for TD and does not have tetrabenazine’s kinetic limitations, adverse effect profile, or CYP2D6 monitoring requirements represents an enormous advance in the treatment of TD.

Clinical implications

Tardive dyskinesia remains a significant public health concern because of the increasing use of antipsychotics for disorders beyond the core indication for schizophrenia. Although exposure to dopamine D2 antagonism could result in postsynaptic receptor upregulation and supersensitivity, this process best explains what underlies withdrawal dyskinesia.3 The persistence of TD symptoms in 66% to 80% of patients after discontinuing offending agents has led to hypotheses that the underlying pathophysiology of TD might best be conceptualized as a problem with neuroplasticity. As with many disorders, environmental contributions (eg, oxidative stress) and genetic predisposition might play a role beyond that related to exposure to D2 antagonism.3

There have been trials of numerous agents, but no medication has been FDA-approved for treating TD, and limited data support the efficacy of a few existing medications (clonazepam, amantadine, and ginkgo biloba extract [EGb-761]),4 albeit with small effect sizes. A medical food, consisting of branched-chain amino acids, received FDA approval for the dietary management of TD in males, but is no longer commercially available except from compounding pharmacies.5

Tetrabenazine, a molecule developed in the mid-1950s to improve on the tolerability of reserpine, was associated with significant adverse effects such as orthostasis.6 Like reserpine, tetrabenazine subsequently was found to be effective for TD7 but without the peripheral adverse effects of reserpine. However, the kinetics of tetrabenazine necessitated multiple daily doses, and required CYP2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d.8

Receptor blocking. The mechanism that differentiated reserpine’s and tetrabenazine’s clinical properties became clearer in the 1980s when researchers discovered that transporters were necessary to package neurotransmitters into the synaptic vesicles of presynaptic neurons.9 The vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) exists in 2 isoforms (VMAT1 and VMAT2) that vary in distribution, with VMAT1 expressed mainly in the peripheral nervous system and VMAT2 expressed mainly in monoaminergic cells of the central nervous system.10

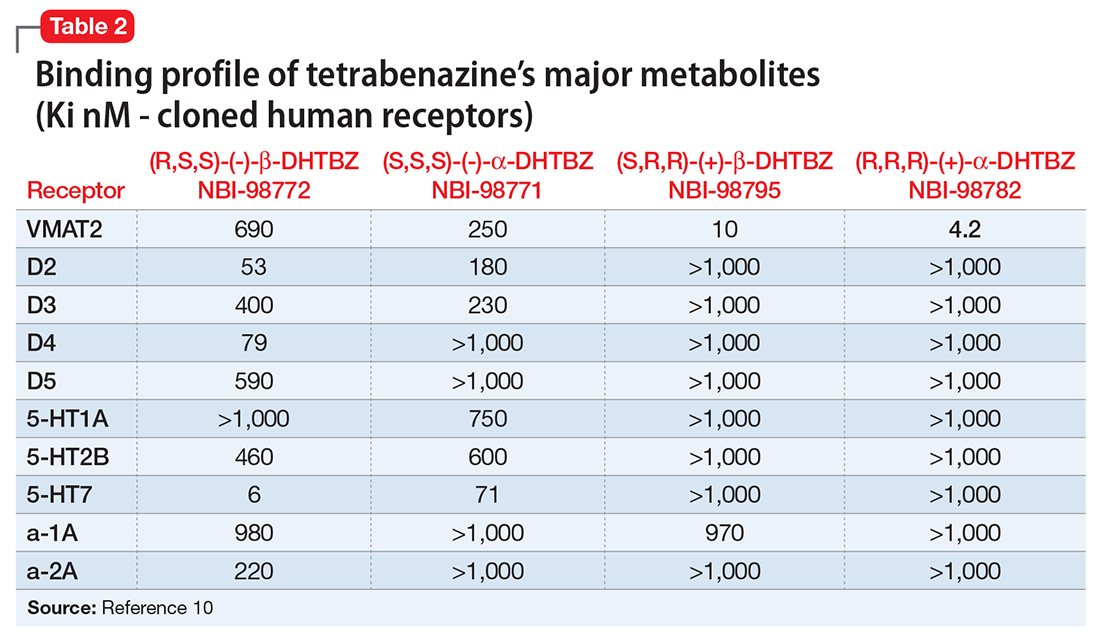

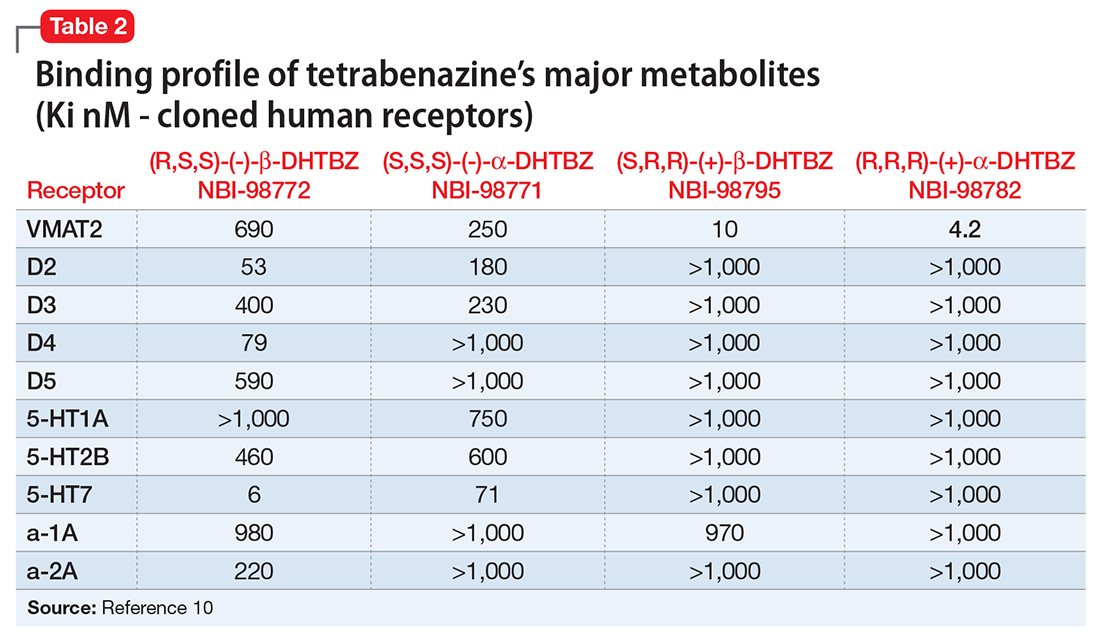

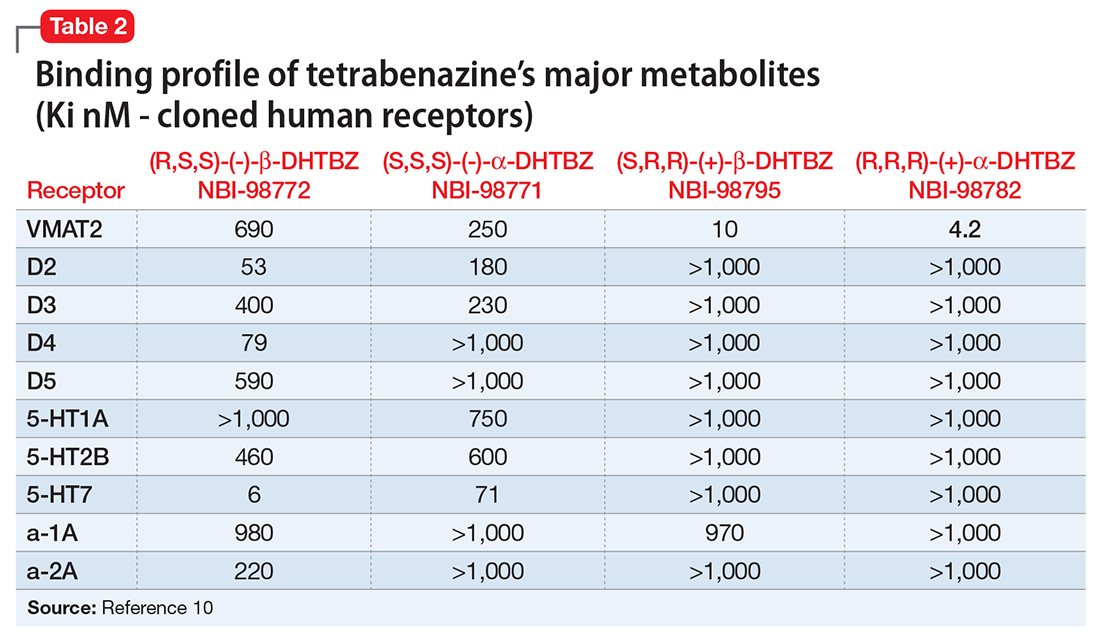

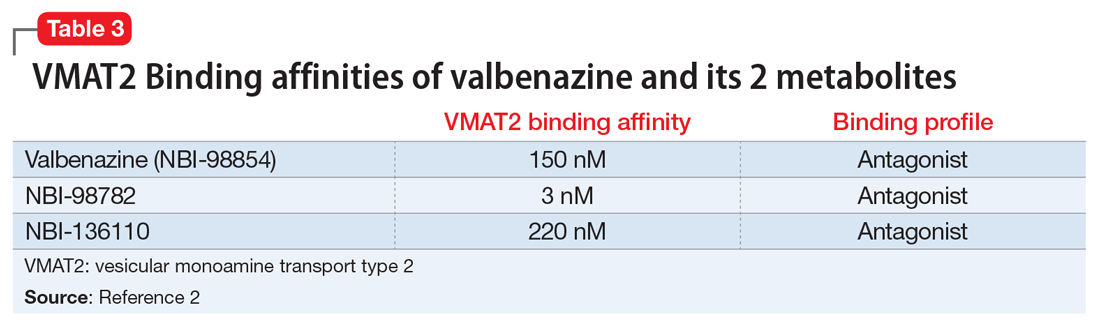

Tetrabenazine’s improved tolerability profile was related to the fact that it is a specific and reversible VMAT2 inhibitor, while reserpine is an irreversible and nonselective antagonist of both VMAT isoforms. Investigation of tetrabenazine’s metabolism revealed that it is rapidly and extensively converted into 2 isomers, α-dihydrotetrabenazine (DH-TBZ) and β-DH-TBZ. The isomeric forms of DH-TBZ have multiple chiral centers, and therefore numerous forms of which only 2 are significantly active at VMAT2.3 The α–DH-TBZ isomer is metabolized via CYP2D6 and 3A4 into inactive metabolites, while β-DH-TBZ is metabolized solely via 2D6.3 Because of the short half-life of DH-TBZ when generated from oral tetrabenazine, the existence of 2D6 polymorphisms, and the predominant activity deriving from only 2 isomers, a molecule was synthesized (valbenazine), that when metabolized would slowly be converted into the most active isomer of α–DH-TBZ designated as NBI-98782 (Table 2). This slower conversion to NBI-98782 from valbenazine (compared with its formation from oral tetrabenazine) yielded improved kinetics and permitted once-daily dosing; moreover, because the metabolism of NBI-98782 is not solely dependent on CYP2D6, the need for genotyping was removed. Neither of the 2 metabolites from valbenazine NBI-98782 and NB-136110 have significant affinity for targets other than VMAT2.11

Use in tardive dyskinesia. Recommended starting dosage is 40 mg once daily with or without food, increased to 80 mg after 1 week, based on the design and results from the phase-III clinical trial.12 The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, and only 1 phase-III trial was performed. Valbenazine produced significant improvement on the AIMS, with a mean 30% reduction in AIMS scores at the Week 6 endpoint from baseline of 10.4 ± 3.6.2 The effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 0.90) for the 80-mg dosage. Continuation of 40 mg/d may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors. Patients taking strong 3A4 inhibitors should not exceed 40 mg/d. The maximum daily dose is 40 mg for those who have moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15). Dosage adjustment is not required for mild to moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance, 30 to 90 mL/min).

Pharmacologic profile, adverse reactions

Valbenazine and its 2 metabolites lack affinity for receptors other than VMAT2, leading to an absence of orthostasis in clinical trials.1,2 In the phase-II trial, 76% of participants receiving valbenazine (n = 51) were titrated to the maximum dosage of 75 mg/d. Common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were headache (9.8% vs 4.1% placebo), fatigue (9.8% vs 4.1% placebo), and somnolence (5.9% vs 2% placebo).1 In the phase-III trial, participants were randomized 1:1:1 to valbenazine, 40 mg (n = 72), valbenazine, 80 mg (n = 79), or placebo (n = 76). In the clinical studies the most common diagnosis was schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and 40% and 85% of participants in the phase-II and phase-III studies, respectively, remained on antipsychotics.1,2 There were no adverse effects with an incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo in the phase-III trial.2

When data from all placebo-controlled studies were pooled, only 1 adverse effect occurred with an incidence ≥5% and twice that of placebo, somnolence with a rate of 10.9% for valbenazine vs 4.2% for placebo. The incidence of akathisia in the pooled analysis was 2.7% for valbenazine vs 0.5% for placebo. Importantly, in neither study was there a safety signal related to depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, or parkinsonism. There also were no clinically significant changes in measures of schizophrenia symptoms.

The mean QT prolongation for valbenazine in healthy participants was 6.7 milliseconds, with the upper bound of the double-sided 90% confidence interval reaching 8.4 milliseconds. For those taking strong 2D6 or 3A4 inhibitors, or known 2D6 poor metabolizers, the mean QT prolongation was 11.7 milliseconds (14.7 milliseconds upper bound of double-sided 90% CI). In the controlled trials, there was a dose-related increase in prolactin, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Overall, 3% of valbenazine-treated patients and 2% of placebo-treated patients discontinued because of adverse reactions.

As noted above, there were no adverse effects with an incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo in the phase-III valbenazine trial. Aggregate data across all placebo-controlled studies found that somnolence was the only adverse effect that occurred with an incidence ≥5% and twice that of placebo (10.9% for valbenazine vs 4.2% for placebo).2 As a comparsion, rates of sedation and akathisia for tetrabenazine were higher in the pivotal Huntington’s disease trial: sedation/somnolence 31% vs 3% for placebo, and akathisia 19% vs 0% for placebo.8

How it works

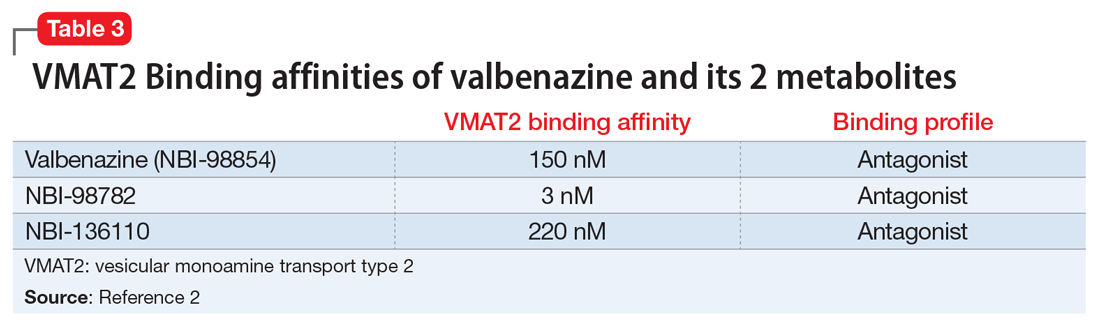

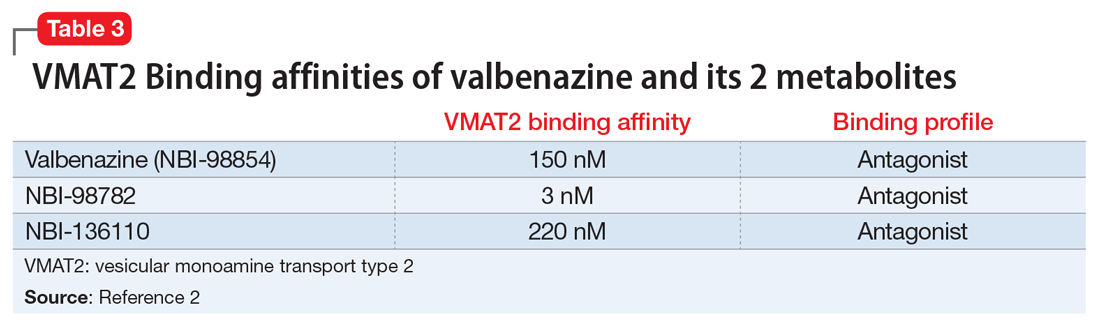

Tetrabenazine, a selective VMAT2 inhibitor, is the only agent that has demonstrated significant efficacy and tolerability for TD management; however, its complex metabolism generates numerous isomers of the metabolites α-DH-TBZ and β-DH-TBZ, of which only 2 are significantly active (Table 3). By choosing an active isomer (NBI-98782) as the metabolite of interest because of its selective and potent activity at VMAT2 and having a metabolism not solely dependent on CYP2D6, a compound was generated (valbenazine) that when metabolized slowly converts into NBI-98782.

Pharmacokinetics

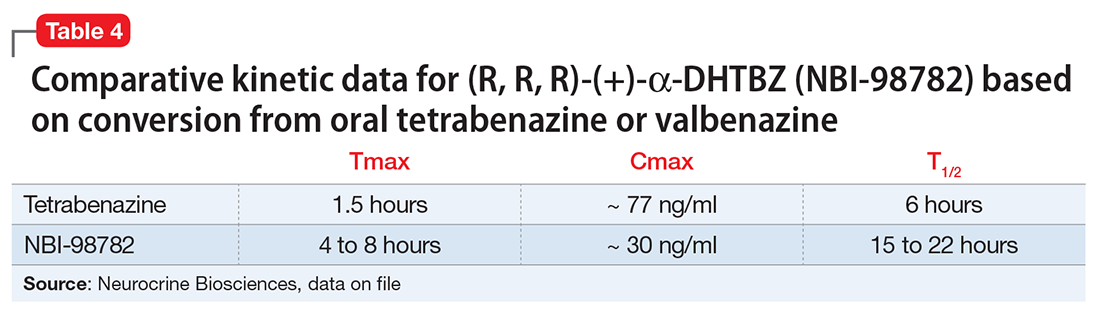

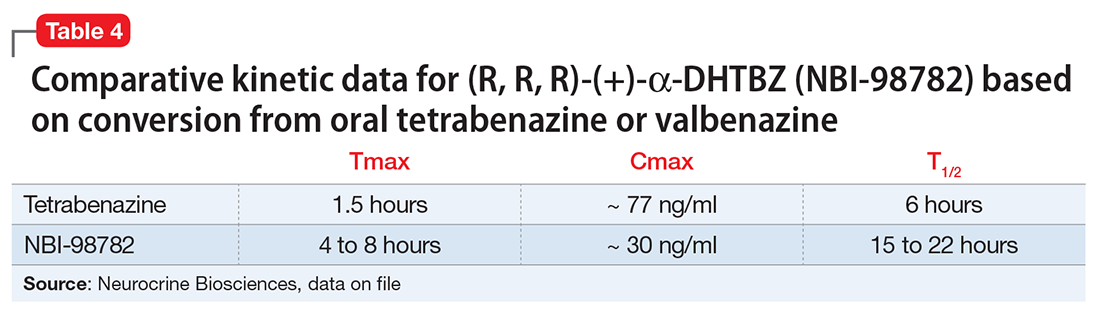

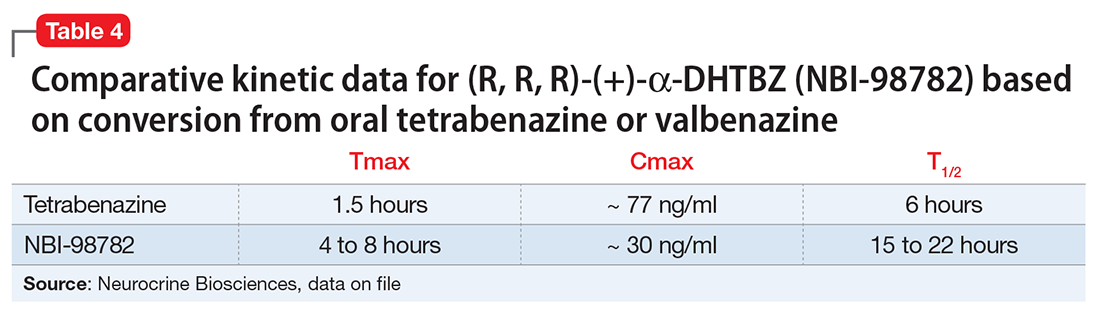

Valbenazine demonstrates dose-proportional pharmacokinetics after single oral dosages from 40 to 300 mg with no impact of food or fasting status on levels of the active metabolite. Valbenazine has a Tmax of 0.5 to 1.0 hours, with 49% oral bioavailability. The plasma half-life for valbenazine and for NBI-98782 ranges from 15 to 22 hours. The Tmax for NBI-98782 when formed from valbenazine occurs between 4 and 8 hours, with a Cmax of approximately 30 ng/mL. It should be noted that when NBI-98782 is generated from oral tetrabenazine, the mean half-life and Tmax are considerably shorter (6 hours and 1.5 hours, respectively), while the Cmax is much higher (approximately 77 ng/mL) (Table 4).

Valbenazine is metabolized through endogenous esterases to NBI-98782 and NBI-136110. NBI-98782, the active metabolite, is further metabolized through multiple CYP pathways, predominantly 3A4 and 2D6. Neither valbenazine nor its metabolites are inhibitors or inducers of major CYP enzymes. Aside from VMAT2, the results of in vitro studies suggest that valbenazine and its active metabolite are unlikely to inhibit most major drug transporters at clinically relevant concentrations. However, valbenazine increased digoxin levels because of inhibition of intestinal P-glycoprotein; therefore plasma digoxin level monitoring is recommended when these 2 are co-administered.

Efficacy

Efficacy was established in a 6-week, fixed-dosage, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adult patients with TD. Eligible participants had:

- DSM-IV diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced TD for ≥3 months before screening and moderate or severe TD, as indicated by AIMS item 8 (severity of abnormal movement), which was rated by a blinded, external reviewer using a video of the participant’s AIMS assessment at screening

- a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or mood disorder (and stable per investigator)

- Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score <50 at screening.

Exclusion criteria included clinically significant and unstable medical conditions within 1 month before screening; comorbid movement disorder (eg, parkinsonism, akathisia, truncal dystonia) that was more prominent than TD; and significant risk for active suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or violent behavior.2 Participants had a mean age of 56, 52% were male, and 65.7% of participants in the valbenazine 40-mg group had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis, as did 65.8% in both the placebo and valbenazine 80-mg arms.

Antipsychotic treatments were permitted during the trial and >85% of participants continued taking these medications during the study. Participants (N = 234) were randomly allocated in a 1:1:1 manner to valbenazine 40 mg, 80 mg, or matched placebo. The primary outcome was change in AIMS total score (items 1 to 7) assessed by central, independent raters. Baseline AIMS scores were 9.9 ± 4.3 in the placebo group, and 9.8 ± 4.1 and 10.4 ± 3.6 in the valbenazine 40-mg and 80-mg arms, respectively.2

Outcome. A fixed-sequence testing procedure to control for family-wise error rate and multiplicity was employed, and the primary endpoint was change from baseline to Week 6 in AIMS total score (items 1 to 7) for valbenazine 80 mg vs placebo. Valbenazine, 40 mg, was associated with a 1.9 point decrease in AIMS score, while valbenazine, 80 mg, was associated with a 3.2 point decrease in AIMS score, compared with 0.1 point decrease for placebo (P < .05 for valbenazine, 40 mg, P < .001 for valbenazine, 80 mg). This difference for the 40-mg dosage did not meet the prespecified analysis endpoints; however, for the 80-mg valbenazine dosage, the effect size for this difference (Cohen’s d) was large 0.90. There also were statistically significant differences between 40 mg and 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in the intent-to-treat population. Of the 79 participants, 43 taking the 80-mg dosage completed a 48-week extension. Efficacy was sustained in this group; however, when valbenazine was discontinued at Week 48, AIMS scores returned to baseline after 4 weeks.

Tolerability

Of the 234 randomized patients, 205 (87.6%) completed the 6-week trial. Discontinuations due to adverse events were low across all treatment groups: 2.6% and 2.8% in the placebo and valbenazine 40-mg arms, respectively, and 3.8% in valbenazine 80-mg cohort. There was no safety signal based on changes in depression, suicidality, parkinsonism rating, or changes in schizophrenia symptoms. Because valbenazine can cause somnolence, patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness (eg, operating a vehicle or hazardous machinery) until they know how they will be affected by valbenazine.

Valbenazine should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or with arrhythmias associated with a prolonged QT interval. For patients at increased risk of a prolonged QT interval, assess the QT interval before increasing the dosage.

Clinical considerations

Unique properties. Valbenazine is metabolized slowly to a potent, selective VMAT2 antagonist (NBI-98782) in a manner that permits once daily dosing, removes the need for CYP2D6 genotyping, and provides significant efficacy.

Why Rx? The reasons to prescribe valbenazine for TD patients include:

- currently the only agent with FDA approval for TD

- fewer tolerability issues seen with the only other effective agent, tetrabenazine

- no signal for effects on mood parameters or rates of parkinsonism

- lack of multiple daily dosing and possible need for 2D6 genotyping involved with TBZ prescribing.

Dosing

The recommended dosage of valbenazine is 80 mg/d administered as a single dose with or without food, starting at 40 mg once daily for 1 week. There is no dosage adjustment required in those with mild to moderate renal impairment; however, valbenazine is not recommended in those with severe renal impairment. The maximum dose is 40 mg/d for those who with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15) however, valbenazine is not recommended for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) because the exposure to the active metabolite is reduced by approximately 75%. The combined efficacy and tolerability of dosages >80 mg/d has not been evaluated. Adverse effects seen with tetrabenazine at higher dosages include akathisia, anxiety, insomnia, parkinsonism, fatigue, and depression.

A daily dose of 40 mg may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP 2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors.2 For those taking strong 3A4 inhibitors, the maximum daily dose is 40 mg. Concomitant use of valbenazine with strong 3A4 inducers is not recommended as the exposure to the active metabolite is reduced by approximately 75%.2 Lastly, because VMAT2 inhibition may alter synaptic levels of other monoamines, it is recommended that valbenazine not be administered with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as isocarboxazid, phenelzine, or selegiline.

Contraindications

There are no reported contraindications for valbenazine. As with most medications, there is limited available data on valbenazine use in pregnant women; however, administration of valbenazine to pregnant rats during organogenesis through lactation produced an increase in the number of stillborn pups and postnatal pup mortalities at doses under the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) using body surface area based dosing (mg/m2). Pregnant women should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus. Valbenazine and its metabolites have been detected in rat milk at concentrations higher than in plasma after oral administration of valbenazine at doses 0.1 to 1.2 times the MRHD (based on mg/m2). Based on animal findings of increased perinatal mortality in exposed fetuses and pups, woman are advised not to breastfeed during valbenazine treatment and for 5 days after the final dose. No dosage adjustment is required for geriatric patients.

1. O’Brien CF, Jimenez R, Hauser RA, et al. NBI-98854, a selective monoamine transport inhibitor for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1681-1687.

2. Ingrezza [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences Inc.; 2017.

3. Marder S, Knesevich MA, Hauser RA, et al. KINECT 3: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of valbenazine (NBI-98854) for tardive dyskinesia. Poster presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 14-18, 2016; Atlanta, GA.

4. Kazamatsuri H, Chien C, Cole JO. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia. I. Clinical efficacy of a dopamine-depleting agent, tetrabenazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;27(1):95-99.

5. Richardson MA, Bevans ML, Read LL, et al. Efficacy of the branched-chain amino acids in the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in men. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1117-1124.

6. Jankovic J, Clarence-Smith K. Tetrabenazine for the treatment of chorea and other hyperkinetic movement disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(11):1509-1523.

7. Meyer JM. Forgotten but not gone: new developments in the understanding and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(S1):13-24.

8. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

9. Quinn GP, Shore PA, Brodie BB. Biochemical and pharmacological studies of RO 1-9569 (tetrabenazine), a nonindole tranquilizing agent with reserpine-like effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959;127:103-109.

10. Scherman D, Weber MJ. Characterization of the vesicular monoamine transporter in cultured rat sympathetic neurons: persistence upon induction of cholinergic phenotypic traits. Dev Biol. 1987;119(1):68-74.

11. Erickson JD, Schafer MK, Bonner TI, et al. Distinct pharmacological properties and distribution in neurons and endocrine cells of two isoforms of the human vesicular monoamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(10):5166-5171.

12. Grigoriadis DE, Smith E, Madan A, et al. Pharmacologic characteristics of valbenazine (NBI-98854) and its metabolites. Poster presented at the U.S. Psychiatric & Mental Health Congress, October 21-24, 2016; San Antonio, TX.

Despite improvements in the tolerability of antipsychotic medications, the development of tardive dyskinesia (TD) still is a significant area of concern; however, clinicians have had few treatment options. Valbenazine, a vesicular monoamine transport type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor, is the only FDA-approved medication for TD (Table 1).1 By modulating dopamine transport into presynaptic vesicles, synaptic dopamine release is decreased, thereby reducing the postsynaptic stimulation of D2 receptors and the severity of dyskinetic movements.

In the pivotal 6-week clinical trial, valbenazine significantly reduced TD severity as measured by Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) ratings.2 Study completion rates were high (87.6%), with only 2 dropouts because of adverse events in each of the placebo (n = 78) and 40-mg (n = 76) arms, and 3 in the 80-mg group (n = 80).

Before the development of valbenazine, tetrabenazine was the only effective option for treating TD. Despite tetrabenazine’s known efficacy for TD, it was not available in the United States until 2008 with the sole indication for movements related to Huntington’s disease. U.S. patients often were subjected to a litany of ineffective medications for TD, often at great expense. Moreover, tetrabenazine involved multiple daily dosing, required cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d, had significant tolerability issues, and a monthly cost of $8,000 to $10,000. The availability of an agent that is effective for TD and does not have tetrabenazine’s kinetic limitations, adverse effect profile, or CYP2D6 monitoring requirements represents an enormous advance in the treatment of TD.

Clinical implications

Tardive dyskinesia remains a significant public health concern because of the increasing use of antipsychotics for disorders beyond the core indication for schizophrenia. Although exposure to dopamine D2 antagonism could result in postsynaptic receptor upregulation and supersensitivity, this process best explains what underlies withdrawal dyskinesia.3 The persistence of TD symptoms in 66% to 80% of patients after discontinuing offending agents has led to hypotheses that the underlying pathophysiology of TD might best be conceptualized as a problem with neuroplasticity. As with many disorders, environmental contributions (eg, oxidative stress) and genetic predisposition might play a role beyond that related to exposure to D2 antagonism.3

There have been trials of numerous agents, but no medication has been FDA-approved for treating TD, and limited data support the efficacy of a few existing medications (clonazepam, amantadine, and ginkgo biloba extract [EGb-761]),4 albeit with small effect sizes. A medical food, consisting of branched-chain amino acids, received FDA approval for the dietary management of TD in males, but is no longer commercially available except from compounding pharmacies.5

Tetrabenazine, a molecule developed in the mid-1950s to improve on the tolerability of reserpine, was associated with significant adverse effects such as orthostasis.6 Like reserpine, tetrabenazine subsequently was found to be effective for TD7 but without the peripheral adverse effects of reserpine. However, the kinetics of tetrabenazine necessitated multiple daily doses, and required CYP2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d.8

Receptor blocking. The mechanism that differentiated reserpine’s and tetrabenazine’s clinical properties became clearer in the 1980s when researchers discovered that transporters were necessary to package neurotransmitters into the synaptic vesicles of presynaptic neurons.9 The vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) exists in 2 isoforms (VMAT1 and VMAT2) that vary in distribution, with VMAT1 expressed mainly in the peripheral nervous system and VMAT2 expressed mainly in monoaminergic cells of the central nervous system.10

Tetrabenazine’s improved tolerability profile was related to the fact that it is a specific and reversible VMAT2 inhibitor, while reserpine is an irreversible and nonselective antagonist of both VMAT isoforms. Investigation of tetrabenazine’s metabolism revealed that it is rapidly and extensively converted into 2 isomers, α-dihydrotetrabenazine (DH-TBZ) and β-DH-TBZ. The isomeric forms of DH-TBZ have multiple chiral centers, and therefore numerous forms of which only 2 are significantly active at VMAT2.3 The α–DH-TBZ isomer is metabolized via CYP2D6 and 3A4 into inactive metabolites, while β-DH-TBZ is metabolized solely via 2D6.3 Because of the short half-life of DH-TBZ when generated from oral tetrabenazine, the existence of 2D6 polymorphisms, and the predominant activity deriving from only 2 isomers, a molecule was synthesized (valbenazine), that when metabolized would slowly be converted into the most active isomer of α–DH-TBZ designated as NBI-98782 (Table 2). This slower conversion to NBI-98782 from valbenazine (compared with its formation from oral tetrabenazine) yielded improved kinetics and permitted once-daily dosing; moreover, because the metabolism of NBI-98782 is not solely dependent on CYP2D6, the need for genotyping was removed. Neither of the 2 metabolites from valbenazine NBI-98782 and NB-136110 have significant affinity for targets other than VMAT2.11

Use in tardive dyskinesia. Recommended starting dosage is 40 mg once daily with or without food, increased to 80 mg after 1 week, based on the design and results from the phase-III clinical trial.12 The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, and only 1 phase-III trial was performed. Valbenazine produced significant improvement on the AIMS, with a mean 30% reduction in AIMS scores at the Week 6 endpoint from baseline of 10.4 ± 3.6.2 The effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 0.90) for the 80-mg dosage. Continuation of 40 mg/d may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors. Patients taking strong 3A4 inhibitors should not exceed 40 mg/d. The maximum daily dose is 40 mg for those who have moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15). Dosage adjustment is not required for mild to moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance, 30 to 90 mL/min).

Pharmacologic profile, adverse reactions

Valbenazine and its 2 metabolites lack affinity for receptors other than VMAT2, leading to an absence of orthostasis in clinical trials.1,2 In the phase-II trial, 76% of participants receiving valbenazine (n = 51) were titrated to the maximum dosage of 75 mg/d. Common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were headache (9.8% vs 4.1% placebo), fatigue (9.8% vs 4.1% placebo), and somnolence (5.9% vs 2% placebo).1 In the phase-III trial, participants were randomized 1:1:1 to valbenazine, 40 mg (n = 72), valbenazine, 80 mg (n = 79), or placebo (n = 76). In the clinical studies the most common diagnosis was schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and 40% and 85% of participants in the phase-II and phase-III studies, respectively, remained on antipsychotics.1,2 There were no adverse effects with an incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo in the phase-III trial.2

When data from all placebo-controlled studies were pooled, only 1 adverse effect occurred with an incidence ≥5% and twice that of placebo, somnolence with a rate of 10.9% for valbenazine vs 4.2% for placebo. The incidence of akathisia in the pooled analysis was 2.7% for valbenazine vs 0.5% for placebo. Importantly, in neither study was there a safety signal related to depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, or parkinsonism. There also were no clinically significant changes in measures of schizophrenia symptoms.

The mean QT prolongation for valbenazine in healthy participants was 6.7 milliseconds, with the upper bound of the double-sided 90% confidence interval reaching 8.4 milliseconds. For those taking strong 2D6 or 3A4 inhibitors, or known 2D6 poor metabolizers, the mean QT prolongation was 11.7 milliseconds (14.7 milliseconds upper bound of double-sided 90% CI). In the controlled trials, there was a dose-related increase in prolactin, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Overall, 3% of valbenazine-treated patients and 2% of placebo-treated patients discontinued because of adverse reactions.

As noted above, there were no adverse effects with an incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo in the phase-III valbenazine trial. Aggregate data across all placebo-controlled studies found that somnolence was the only adverse effect that occurred with an incidence ≥5% and twice that of placebo (10.9% for valbenazine vs 4.2% for placebo).2 As a comparsion, rates of sedation and akathisia for tetrabenazine were higher in the pivotal Huntington’s disease trial: sedation/somnolence 31% vs 3% for placebo, and akathisia 19% vs 0% for placebo.8

How it works

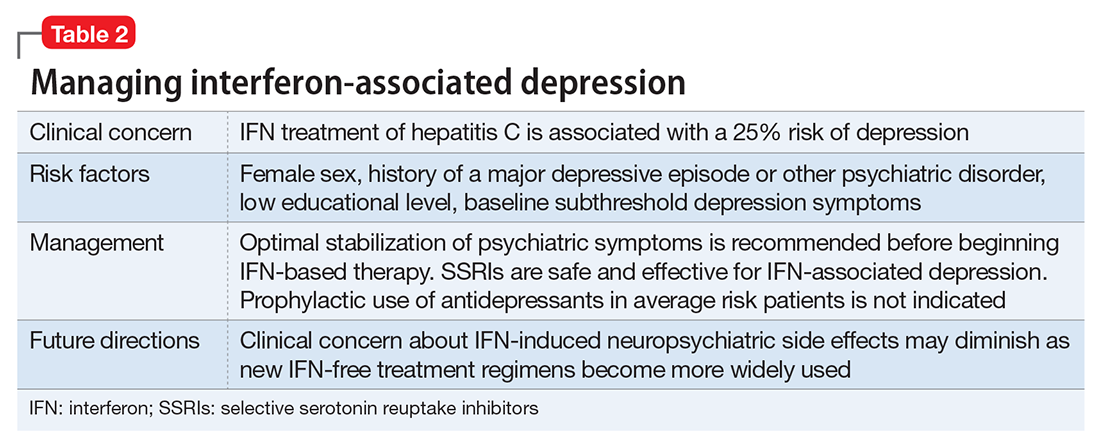

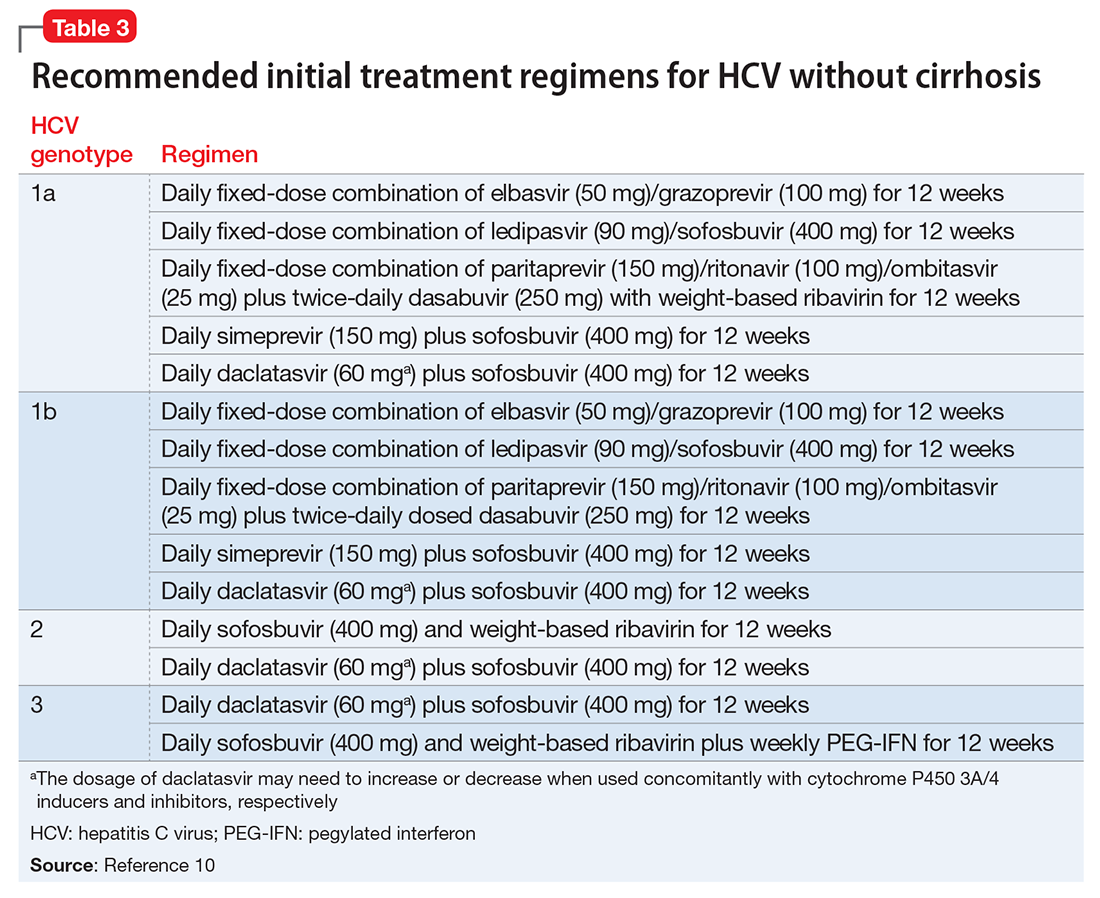

Tetrabenazine, a selective VMAT2 inhibitor, is the only agent that has demonstrated significant efficacy and tolerability for TD management; however, its complex metabolism generates numerous isomers of the metabolites α-DH-TBZ and β-DH-TBZ, of which only 2 are significantly active (Table 3). By choosing an active isomer (NBI-98782) as the metabolite of interest because of its selective and potent activity at VMAT2 and having a metabolism not solely dependent on CYP2D6, a compound was generated (valbenazine) that when metabolized slowly converts into NBI-98782.

Pharmacokinetics

Valbenazine demonstrates dose-proportional pharmacokinetics after single oral dosages from 40 to 300 mg with no impact of food or fasting status on levels of the active metabolite. Valbenazine has a Tmax of 0.5 to 1.0 hours, with 49% oral bioavailability. The plasma half-life for valbenazine and for NBI-98782 ranges from 15 to 22 hours. The Tmax for NBI-98782 when formed from valbenazine occurs between 4 and 8 hours, with a Cmax of approximately 30 ng/mL. It should be noted that when NBI-98782 is generated from oral tetrabenazine, the mean half-life and Tmax are considerably shorter (6 hours and 1.5 hours, respectively), while the Cmax is much higher (approximately 77 ng/mL) (Table 4).

Valbenazine is metabolized through endogenous esterases to NBI-98782 and NBI-136110. NBI-98782, the active metabolite, is further metabolized through multiple CYP pathways, predominantly 3A4 and 2D6. Neither valbenazine nor its metabolites are inhibitors or inducers of major CYP enzymes. Aside from VMAT2, the results of in vitro studies suggest that valbenazine and its active metabolite are unlikely to inhibit most major drug transporters at clinically relevant concentrations. However, valbenazine increased digoxin levels because of inhibition of intestinal P-glycoprotein; therefore plasma digoxin level monitoring is recommended when these 2 are co-administered.

Efficacy

Efficacy was established in a 6-week, fixed-dosage, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adult patients with TD. Eligible participants had:

- DSM-IV diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced TD for ≥3 months before screening and moderate or severe TD, as indicated by AIMS item 8 (severity of abnormal movement), which was rated by a blinded, external reviewer using a video of the participant’s AIMS assessment at screening

- a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or mood disorder (and stable per investigator)

- Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score <50 at screening.

Exclusion criteria included clinically significant and unstable medical conditions within 1 month before screening; comorbid movement disorder (eg, parkinsonism, akathisia, truncal dystonia) that was more prominent than TD; and significant risk for active suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or violent behavior.2 Participants had a mean age of 56, 52% were male, and 65.7% of participants in the valbenazine 40-mg group had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis, as did 65.8% in both the placebo and valbenazine 80-mg arms.

Antipsychotic treatments were permitted during the trial and >85% of participants continued taking these medications during the study. Participants (N = 234) were randomly allocated in a 1:1:1 manner to valbenazine 40 mg, 80 mg, or matched placebo. The primary outcome was change in AIMS total score (items 1 to 7) assessed by central, independent raters. Baseline AIMS scores were 9.9 ± 4.3 in the placebo group, and 9.8 ± 4.1 and 10.4 ± 3.6 in the valbenazine 40-mg and 80-mg arms, respectively.2

Outcome. A fixed-sequence testing procedure to control for family-wise error rate and multiplicity was employed, and the primary endpoint was change from baseline to Week 6 in AIMS total score (items 1 to 7) for valbenazine 80 mg vs placebo. Valbenazine, 40 mg, was associated with a 1.9 point decrease in AIMS score, while valbenazine, 80 mg, was associated with a 3.2 point decrease in AIMS score, compared with 0.1 point decrease for placebo (P < .05 for valbenazine, 40 mg, P < .001 for valbenazine, 80 mg). This difference for the 40-mg dosage did not meet the prespecified analysis endpoints; however, for the 80-mg valbenazine dosage, the effect size for this difference (Cohen’s d) was large 0.90. There also were statistically significant differences between 40 mg and 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in the intent-to-treat population. Of the 79 participants, 43 taking the 80-mg dosage completed a 48-week extension. Efficacy was sustained in this group; however, when valbenazine was discontinued at Week 48, AIMS scores returned to baseline after 4 weeks.

Tolerability

Of the 234 randomized patients, 205 (87.6%) completed the 6-week trial. Discontinuations due to adverse events were low across all treatment groups: 2.6% and 2.8% in the placebo and valbenazine 40-mg arms, respectively, and 3.8% in valbenazine 80-mg cohort. There was no safety signal based on changes in depression, suicidality, parkinsonism rating, or changes in schizophrenia symptoms. Because valbenazine can cause somnolence, patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness (eg, operating a vehicle or hazardous machinery) until they know how they will be affected by valbenazine.

Valbenazine should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or with arrhythmias associated with a prolonged QT interval. For patients at increased risk of a prolonged QT interval, assess the QT interval before increasing the dosage.

Clinical considerations

Unique properties. Valbenazine is metabolized slowly to a potent, selective VMAT2 antagonist (NBI-98782) in a manner that permits once daily dosing, removes the need for CYP2D6 genotyping, and provides significant efficacy.

Why Rx? The reasons to prescribe valbenazine for TD patients include:

- currently the only agent with FDA approval for TD

- fewer tolerability issues seen with the only other effective agent, tetrabenazine

- no signal for effects on mood parameters or rates of parkinsonism

- lack of multiple daily dosing and possible need for 2D6 genotyping involved with TBZ prescribing.

Dosing

The recommended dosage of valbenazine is 80 mg/d administered as a single dose with or without food, starting at 40 mg once daily for 1 week. There is no dosage adjustment required in those with mild to moderate renal impairment; however, valbenazine is not recommended in those with severe renal impairment. The maximum dose is 40 mg/d for those who with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15) however, valbenazine is not recommended for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) because the exposure to the active metabolite is reduced by approximately 75%. The combined efficacy and tolerability of dosages >80 mg/d has not been evaluated. Adverse effects seen with tetrabenazine at higher dosages include akathisia, anxiety, insomnia, parkinsonism, fatigue, and depression.

A daily dose of 40 mg may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP 2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors.2 For those taking strong 3A4 inhibitors, the maximum daily dose is 40 mg. Concomitant use of valbenazine with strong 3A4 inducers is not recommended as the exposure to the active metabolite is reduced by approximately 75%.2 Lastly, because VMAT2 inhibition may alter synaptic levels of other monoamines, it is recommended that valbenazine not be administered with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as isocarboxazid, phenelzine, or selegiline.

Contraindications

There are no reported contraindications for valbenazine. As with most medications, there is limited available data on valbenazine use in pregnant women; however, administration of valbenazine to pregnant rats during organogenesis through lactation produced an increase in the number of stillborn pups and postnatal pup mortalities at doses under the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) using body surface area based dosing (mg/m2). Pregnant women should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus. Valbenazine and its metabolites have been detected in rat milk at concentrations higher than in plasma after oral administration of valbenazine at doses 0.1 to 1.2 times the MRHD (based on mg/m2). Based on animal findings of increased perinatal mortality in exposed fetuses and pups, woman are advised not to breastfeed during valbenazine treatment and for 5 days after the final dose. No dosage adjustment is required for geriatric patients.

Despite improvements in the tolerability of antipsychotic medications, the development of tardive dyskinesia (TD) still is a significant area of concern; however, clinicians have had few treatment options. Valbenazine, a vesicular monoamine transport type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor, is the only FDA-approved medication for TD (Table 1).1 By modulating dopamine transport into presynaptic vesicles, synaptic dopamine release is decreased, thereby reducing the postsynaptic stimulation of D2 receptors and the severity of dyskinetic movements.

In the pivotal 6-week clinical trial, valbenazine significantly reduced TD severity as measured by Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) ratings.2 Study completion rates were high (87.6%), with only 2 dropouts because of adverse events in each of the placebo (n = 78) and 40-mg (n = 76) arms, and 3 in the 80-mg group (n = 80).

Before the development of valbenazine, tetrabenazine was the only effective option for treating TD. Despite tetrabenazine’s known efficacy for TD, it was not available in the United States until 2008 with the sole indication for movements related to Huntington’s disease. U.S. patients often were subjected to a litany of ineffective medications for TD, often at great expense. Moreover, tetrabenazine involved multiple daily dosing, required cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d, had significant tolerability issues, and a monthly cost of $8,000 to $10,000. The availability of an agent that is effective for TD and does not have tetrabenazine’s kinetic limitations, adverse effect profile, or CYP2D6 monitoring requirements represents an enormous advance in the treatment of TD.

Clinical implications

Tardive dyskinesia remains a significant public health concern because of the increasing use of antipsychotics for disorders beyond the core indication for schizophrenia. Although exposure to dopamine D2 antagonism could result in postsynaptic receptor upregulation and supersensitivity, this process best explains what underlies withdrawal dyskinesia.3 The persistence of TD symptoms in 66% to 80% of patients after discontinuing offending agents has led to hypotheses that the underlying pathophysiology of TD might best be conceptualized as a problem with neuroplasticity. As with many disorders, environmental contributions (eg, oxidative stress) and genetic predisposition might play a role beyond that related to exposure to D2 antagonism.3

There have been trials of numerous agents, but no medication has been FDA-approved for treating TD, and limited data support the efficacy of a few existing medications (clonazepam, amantadine, and ginkgo biloba extract [EGb-761]),4 albeit with small effect sizes. A medical food, consisting of branched-chain amino acids, received FDA approval for the dietary management of TD in males, but is no longer commercially available except from compounding pharmacies.5

Tetrabenazine, a molecule developed in the mid-1950s to improve on the tolerability of reserpine, was associated with significant adverse effects such as orthostasis.6 Like reserpine, tetrabenazine subsequently was found to be effective for TD7 but without the peripheral adverse effects of reserpine. However, the kinetics of tetrabenazine necessitated multiple daily doses, and required CYP2D6 genotyping for doses >50 mg/d.8

Receptor blocking. The mechanism that differentiated reserpine’s and tetrabenazine’s clinical properties became clearer in the 1980s when researchers discovered that transporters were necessary to package neurotransmitters into the synaptic vesicles of presynaptic neurons.9 The vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) exists in 2 isoforms (VMAT1 and VMAT2) that vary in distribution, with VMAT1 expressed mainly in the peripheral nervous system and VMAT2 expressed mainly in monoaminergic cells of the central nervous system.10

Tetrabenazine’s improved tolerability profile was related to the fact that it is a specific and reversible VMAT2 inhibitor, while reserpine is an irreversible and nonselective antagonist of both VMAT isoforms. Investigation of tetrabenazine’s metabolism revealed that it is rapidly and extensively converted into 2 isomers, α-dihydrotetrabenazine (DH-TBZ) and β-DH-TBZ. The isomeric forms of DH-TBZ have multiple chiral centers, and therefore numerous forms of which only 2 are significantly active at VMAT2.3 The α–DH-TBZ isomer is metabolized via CYP2D6 and 3A4 into inactive metabolites, while β-DH-TBZ is metabolized solely via 2D6.3 Because of the short half-life of DH-TBZ when generated from oral tetrabenazine, the existence of 2D6 polymorphisms, and the predominant activity deriving from only 2 isomers, a molecule was synthesized (valbenazine), that when metabolized would slowly be converted into the most active isomer of α–DH-TBZ designated as NBI-98782 (Table 2). This slower conversion to NBI-98782 from valbenazine (compared with its formation from oral tetrabenazine) yielded improved kinetics and permitted once-daily dosing; moreover, because the metabolism of NBI-98782 is not solely dependent on CYP2D6, the need for genotyping was removed. Neither of the 2 metabolites from valbenazine NBI-98782 and NB-136110 have significant affinity for targets other than VMAT2.11

Use in tardive dyskinesia. Recommended starting dosage is 40 mg once daily with or without food, increased to 80 mg after 1 week, based on the design and results from the phase-III clinical trial.12 The FDA granted breakthrough therapy designation for this compound, and only 1 phase-III trial was performed. Valbenazine produced significant improvement on the AIMS, with a mean 30% reduction in AIMS scores at the Week 6 endpoint from baseline of 10.4 ± 3.6.2 The effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 0.90) for the 80-mg dosage. Continuation of 40 mg/d may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors. Patients taking strong 3A4 inhibitors should not exceed 40 mg/d. The maximum daily dose is 40 mg for those who have moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15). Dosage adjustment is not required for mild to moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance, 30 to 90 mL/min).

Pharmacologic profile, adverse reactions

Valbenazine and its 2 metabolites lack affinity for receptors other than VMAT2, leading to an absence of orthostasis in clinical trials.1,2 In the phase-II trial, 76% of participants receiving valbenazine (n = 51) were titrated to the maximum dosage of 75 mg/d. Common adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were headache (9.8% vs 4.1% placebo), fatigue (9.8% vs 4.1% placebo), and somnolence (5.9% vs 2% placebo).1 In the phase-III trial, participants were randomized 1:1:1 to valbenazine, 40 mg (n = 72), valbenazine, 80 mg (n = 79), or placebo (n = 76). In the clinical studies the most common diagnosis was schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and 40% and 85% of participants in the phase-II and phase-III studies, respectively, remained on antipsychotics.1,2 There were no adverse effects with an incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo in the phase-III trial.2

When data from all placebo-controlled studies were pooled, only 1 adverse effect occurred with an incidence ≥5% and twice that of placebo, somnolence with a rate of 10.9% for valbenazine vs 4.2% for placebo. The incidence of akathisia in the pooled analysis was 2.7% for valbenazine vs 0.5% for placebo. Importantly, in neither study was there a safety signal related to depression, suicidal ideation and behavior, or parkinsonism. There also were no clinically significant changes in measures of schizophrenia symptoms.

The mean QT prolongation for valbenazine in healthy participants was 6.7 milliseconds, with the upper bound of the double-sided 90% confidence interval reaching 8.4 milliseconds. For those taking strong 2D6 or 3A4 inhibitors, or known 2D6 poor metabolizers, the mean QT prolongation was 11.7 milliseconds (14.7 milliseconds upper bound of double-sided 90% CI). In the controlled trials, there was a dose-related increase in prolactin, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Overall, 3% of valbenazine-treated patients and 2% of placebo-treated patients discontinued because of adverse reactions.

As noted above, there were no adverse effects with an incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo in the phase-III valbenazine trial. Aggregate data across all placebo-controlled studies found that somnolence was the only adverse effect that occurred with an incidence ≥5% and twice that of placebo (10.9% for valbenazine vs 4.2% for placebo).2 As a comparsion, rates of sedation and akathisia for tetrabenazine were higher in the pivotal Huntington’s disease trial: sedation/somnolence 31% vs 3% for placebo, and akathisia 19% vs 0% for placebo.8

How it works

Tetrabenazine, a selective VMAT2 inhibitor, is the only agent that has demonstrated significant efficacy and tolerability for TD management; however, its complex metabolism generates numerous isomers of the metabolites α-DH-TBZ and β-DH-TBZ, of which only 2 are significantly active (Table 3). By choosing an active isomer (NBI-98782) as the metabolite of interest because of its selective and potent activity at VMAT2 and having a metabolism not solely dependent on CYP2D6, a compound was generated (valbenazine) that when metabolized slowly converts into NBI-98782.

Pharmacokinetics

Valbenazine demonstrates dose-proportional pharmacokinetics after single oral dosages from 40 to 300 mg with no impact of food or fasting status on levels of the active metabolite. Valbenazine has a Tmax of 0.5 to 1.0 hours, with 49% oral bioavailability. The plasma half-life for valbenazine and for NBI-98782 ranges from 15 to 22 hours. The Tmax for NBI-98782 when formed from valbenazine occurs between 4 and 8 hours, with a Cmax of approximately 30 ng/mL. It should be noted that when NBI-98782 is generated from oral tetrabenazine, the mean half-life and Tmax are considerably shorter (6 hours and 1.5 hours, respectively), while the Cmax is much higher (approximately 77 ng/mL) (Table 4).

Valbenazine is metabolized through endogenous esterases to NBI-98782 and NBI-136110. NBI-98782, the active metabolite, is further metabolized through multiple CYP pathways, predominantly 3A4 and 2D6. Neither valbenazine nor its metabolites are inhibitors or inducers of major CYP enzymes. Aside from VMAT2, the results of in vitro studies suggest that valbenazine and its active metabolite are unlikely to inhibit most major drug transporters at clinically relevant concentrations. However, valbenazine increased digoxin levels because of inhibition of intestinal P-glycoprotein; therefore plasma digoxin level monitoring is recommended when these 2 are co-administered.

Efficacy

Efficacy was established in a 6-week, fixed-dosage, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adult patients with TD. Eligible participants had:

- DSM-IV diagnosis of antipsychotic-induced TD for ≥3 months before screening and moderate or severe TD, as indicated by AIMS item 8 (severity of abnormal movement), which was rated by a blinded, external reviewer using a video of the participant’s AIMS assessment at screening

- a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder or mood disorder (and stable per investigator)

- Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale score <50 at screening.

Exclusion criteria included clinically significant and unstable medical conditions within 1 month before screening; comorbid movement disorder (eg, parkinsonism, akathisia, truncal dystonia) that was more prominent than TD; and significant risk for active suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or violent behavior.2 Participants had a mean age of 56, 52% were male, and 65.7% of participants in the valbenazine 40-mg group had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis, as did 65.8% in both the placebo and valbenazine 80-mg arms.

Antipsychotic treatments were permitted during the trial and >85% of participants continued taking these medications during the study. Participants (N = 234) were randomly allocated in a 1:1:1 manner to valbenazine 40 mg, 80 mg, or matched placebo. The primary outcome was change in AIMS total score (items 1 to 7) assessed by central, independent raters. Baseline AIMS scores were 9.9 ± 4.3 in the placebo group, and 9.8 ± 4.1 and 10.4 ± 3.6 in the valbenazine 40-mg and 80-mg arms, respectively.2

Outcome. A fixed-sequence testing procedure to control for family-wise error rate and multiplicity was employed, and the primary endpoint was change from baseline to Week 6 in AIMS total score (items 1 to 7) for valbenazine 80 mg vs placebo. Valbenazine, 40 mg, was associated with a 1.9 point decrease in AIMS score, while valbenazine, 80 mg, was associated with a 3.2 point decrease in AIMS score, compared with 0.1 point decrease for placebo (P < .05 for valbenazine, 40 mg, P < .001 for valbenazine, 80 mg). This difference for the 40-mg dosage did not meet the prespecified analysis endpoints; however, for the 80-mg valbenazine dosage, the effect size for this difference (Cohen’s d) was large 0.90. There also were statistically significant differences between 40 mg and 80 mg at weeks 2, 4, and 6 in the intent-to-treat population. Of the 79 participants, 43 taking the 80-mg dosage completed a 48-week extension. Efficacy was sustained in this group; however, when valbenazine was discontinued at Week 48, AIMS scores returned to baseline after 4 weeks.

Tolerability

Of the 234 randomized patients, 205 (87.6%) completed the 6-week trial. Discontinuations due to adverse events were low across all treatment groups: 2.6% and 2.8% in the placebo and valbenazine 40-mg arms, respectively, and 3.8% in valbenazine 80-mg cohort. There was no safety signal based on changes in depression, suicidality, parkinsonism rating, or changes in schizophrenia symptoms. Because valbenazine can cause somnolence, patients should not perform activities requiring mental alertness (eg, operating a vehicle or hazardous machinery) until they know how they will be affected by valbenazine.

Valbenazine should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or with arrhythmias associated with a prolonged QT interval. For patients at increased risk of a prolonged QT interval, assess the QT interval before increasing the dosage.

Clinical considerations

Unique properties. Valbenazine is metabolized slowly to a potent, selective VMAT2 antagonist (NBI-98782) in a manner that permits once daily dosing, removes the need for CYP2D6 genotyping, and provides significant efficacy.

Why Rx? The reasons to prescribe valbenazine for TD patients include:

- currently the only agent with FDA approval for TD

- fewer tolerability issues seen with the only other effective agent, tetrabenazine

- no signal for effects on mood parameters or rates of parkinsonism

- lack of multiple daily dosing and possible need for 2D6 genotyping involved with TBZ prescribing.

Dosing

The recommended dosage of valbenazine is 80 mg/d administered as a single dose with or without food, starting at 40 mg once daily for 1 week. There is no dosage adjustment required in those with mild to moderate renal impairment; however, valbenazine is not recommended in those with severe renal impairment. The maximum dose is 40 mg/d for those who with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score, 7 to 15) however, valbenazine is not recommended for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min) because the exposure to the active metabolite is reduced by approximately 75%. The combined efficacy and tolerability of dosages >80 mg/d has not been evaluated. Adverse effects seen with tetrabenazine at higher dosages include akathisia, anxiety, insomnia, parkinsonism, fatigue, and depression.

A daily dose of 40 mg may be considered for some patients based on tolerability, including those who are known CYP 2D6 poor metabolizers, and those taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors.2 For those taking strong 3A4 inhibitors, the maximum daily dose is 40 mg. Concomitant use of valbenazine with strong 3A4 inducers is not recommended as the exposure to the active metabolite is reduced by approximately 75%.2 Lastly, because VMAT2 inhibition may alter synaptic levels of other monoamines, it is recommended that valbenazine not be administered with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, such as isocarboxazid, phenelzine, or selegiline.

Contraindications

There are no reported contraindications for valbenazine. As with most medications, there is limited available data on valbenazine use in pregnant women; however, administration of valbenazine to pregnant rats during organogenesis through lactation produced an increase in the number of stillborn pups and postnatal pup mortalities at doses under the maximum recommended human dose (MRHD) using body surface area based dosing (mg/m2). Pregnant women should be advised of the potential risk to a fetus. Valbenazine and its metabolites have been detected in rat milk at concentrations higher than in plasma after oral administration of valbenazine at doses 0.1 to 1.2 times the MRHD (based on mg/m2). Based on animal findings of increased perinatal mortality in exposed fetuses and pups, woman are advised not to breastfeed during valbenazine treatment and for 5 days after the final dose. No dosage adjustment is required for geriatric patients.

1. O’Brien CF, Jimenez R, Hauser RA, et al. NBI-98854, a selective monoamine transport inhibitor for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1681-1687.

2. Ingrezza [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences Inc.; 2017.

3. Marder S, Knesevich MA, Hauser RA, et al. KINECT 3: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of valbenazine (NBI-98854) for tardive dyskinesia. Poster presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 14-18, 2016; Atlanta, GA.

4. Kazamatsuri H, Chien C, Cole JO. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia. I. Clinical efficacy of a dopamine-depleting agent, tetrabenazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;27(1):95-99.

5. Richardson MA, Bevans ML, Read LL, et al. Efficacy of the branched-chain amino acids in the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in men. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1117-1124.

6. Jankovic J, Clarence-Smith K. Tetrabenazine for the treatment of chorea and other hyperkinetic movement disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(11):1509-1523.

7. Meyer JM. Forgotten but not gone: new developments in the understanding and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(S1):13-24.

8. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

9. Quinn GP, Shore PA, Brodie BB. Biochemical and pharmacological studies of RO 1-9569 (tetrabenazine), a nonindole tranquilizing agent with reserpine-like effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959;127:103-109.

10. Scherman D, Weber MJ. Characterization of the vesicular monoamine transporter in cultured rat sympathetic neurons: persistence upon induction of cholinergic phenotypic traits. Dev Biol. 1987;119(1):68-74.

11. Erickson JD, Schafer MK, Bonner TI, et al. Distinct pharmacological properties and distribution in neurons and endocrine cells of two isoforms of the human vesicular monoamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(10):5166-5171.

12. Grigoriadis DE, Smith E, Madan A, et al. Pharmacologic characteristics of valbenazine (NBI-98854) and its metabolites. Poster presented at the U.S. Psychiatric & Mental Health Congress, October 21-24, 2016; San Antonio, TX.

1. O’Brien CF, Jimenez R, Hauser RA, et al. NBI-98854, a selective monoamine transport inhibitor for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2015;30(12):1681-1687.

2. Ingrezza [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Neurocrine Biosciences Inc.; 2017.

3. Marder S, Knesevich MA, Hauser RA, et al. KINECT 3: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of valbenazine (NBI-98854) for tardive dyskinesia. Poster presented at the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting; May 14-18, 2016; Atlanta, GA.

4. Kazamatsuri H, Chien C, Cole JO. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia. I. Clinical efficacy of a dopamine-depleting agent, tetrabenazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;27(1):95-99.

5. Richardson MA, Bevans ML, Read LL, et al. Efficacy of the branched-chain amino acids in the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in men. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1117-1124.

6. Jankovic J, Clarence-Smith K. Tetrabenazine for the treatment of chorea and other hyperkinetic movement disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(11):1509-1523.

7. Meyer JM. Forgotten but not gone: new developments in the understanding and treatment of tardive dyskinesia. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(S1):13-24.

8. Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

9. Quinn GP, Shore PA, Brodie BB. Biochemical and pharmacological studies of RO 1-9569 (tetrabenazine), a nonindole tranquilizing agent with reserpine-like effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1959;127:103-109.

10. Scherman D, Weber MJ. Characterization of the vesicular monoamine transporter in cultured rat sympathetic neurons: persistence upon induction of cholinergic phenotypic traits. Dev Biol. 1987;119(1):68-74.

11. Erickson JD, Schafer MK, Bonner TI, et al. Distinct pharmacological properties and distribution in neurons and endocrine cells of two isoforms of the human vesicular monoamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(10):5166-5171.

12. Grigoriadis DE, Smith E, Madan A, et al. Pharmacologic characteristics of valbenazine (NBI-98854) and its metabolites. Poster presented at the U.S. Psychiatric & Mental Health Congress, October 21-24, 2016; San Antonio, TX.

People often think functional neurological symptoms are feigned

Clinicians, other caregivers, and even patients often think that functional neurological symptoms and movement disorders are feigned or somewhat amenable to the patient’s control, according to two separate survey studies published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

In the first study, Sandra M. A. van der Salm, MD, and her associates reported their assessments of clinicians’ and patients’ views about “free will” pertaining to three movement disorders: functional (“psychogenic”) movement disorders, myoclonus, and tics. They administered survey questionnaires to 39 expert clinicians, 28 patients with functional movement disorders, 15 patients with myoclonus, 17 patients with tics, and 22 healthy control subjects.