User login

Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation

Throwing and batting each require repetitive motions that can result in injuries unique to baseball. Fortuantely, advances in operative and nonoperative treatments have allowed players to return to competition after sustaining what previously would have been considered a career-ending injury. Once a player has been deemed ready to return to throwing or hitting, a comprehensive, multiphased approach to rehabilitation is necessary to reintroduce the athlete back to baseball activities and avoid re-injury. This article reviews the biomechanics of both throwing and hitting, and outlines the phases of rehabilitation necessary to allow the athlete to return to competition.

Throwing

Biomechanical Overview

The overhead throwing motion is complex and involves full body coordination from the initial force generation through the follow-through phase of throwing. The “kinetic chain”—the concept that movements in the body are connected through segments culminating with the highest energy in the final segment—is paramount to achieving the force and energy needed for throwing.1-8 The kinetic chain begins in the lower body and trunk and transmits the energy distally to the shoulder, elbow, and hand, ending with kinetic energy transfer to the ball.3-5,7 The progression of motion through the kinetic chain during throwing includes stride, pelvis rotation, upper torso rotation, elbow extension, shoulder internal rotation, and wrist flexion. Disruptions in this chain due to muscle imbalance or weakness can lead to injury downstream, particularly in the upper extremity.3,7,9

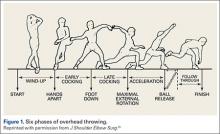

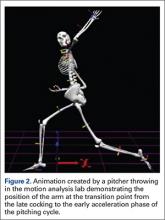

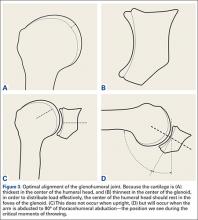

The importance of the kinetic chain can be highlighted in the 6 phases of throwing motion. These include wind-up, early arm cocking, late arm cocking, arm acceleration, arm deceleration, and follow-through (Figure 1).1,2,9,10

The wind-up phase starts with initiation of motion and ends with maximal knee lift of the lead leg; its objective is to place the body in an optimal stance to throw.3-5,7 There are minimal forces, torques, and muscle activity in the upper extremity during this phase, but up to 50% of throw speed is created through stride and trunk rotation.6 During the early cocking phase, the thrower keeps his stance foot planted and drives his lead leg towards the target, while bringing both arms into abduction. This is coupled with internal rotation of the stance hip, external rotation of the lead hip, and external rotation of the throwing shoulder. This creates linear velocity by maximizing the length of the elastic components of the body. Elbow, wrist, and finger extensors are also contracting during this phase to control elbow flexion and wrist hyperextension.3

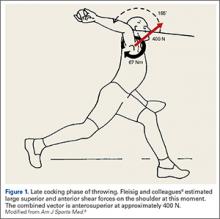

The late cocking phase begins when the lead foot contacts the ground and ends with maximum shoulder external rotation.3-5 Lead foot contact is followed by quadriceps contraction to decelerate and stabilize the lead leg. This is followed by rotation of the pelvis and upper torso. The result is energy transfer to the throwing arm with a shear force across the anterior shoulder of 400 N.4 The shoulder stays in 90° of abduction, 15° of horizontal adduction, and externally rotates to between 150° and 180°. This produces a maximum horizontal adduction moment of 100 N.m and internal rotation torque of 70 N.m.4 Simultaneously, the elbow generates maximum flexion and a 65 N.m varus torque.7 Forces about the elbow are generated to resist the large angular velocity experienced (up to 3000°/second). This places an extreme amount of valgus stress along the medial elbow, particularly on the ulnar collateral ligament. The shoulder girdle and rotator cuff muscles simultaneously act to stabilize the scapula and glenohumeral joint.

The arm acceleration phase is from maximal shoulder external rotation until ball release.3-5 In this phase, the thrower flexes his trunk from an extended position, returning to neutral by the time of ball release while the lead leg straightens. The shoulder stays abducted at 90° throughout while the rotator cuff internal rotators and scapular stabilizers contract to explosively internally rotate the shoulder, creating a maximal internal rotation velocity greater than 7000°/second by ball release.1,4,7 The elbow also begins to extend, reaching maximum velocity during mid-acceleration phase from a combination of triceps contraction and torque generated from rotation at the shoulder and upper trunk.3 Finally, the wrist flexors contract to move the wrist to a neutral position from hyperextension as the ball is released.

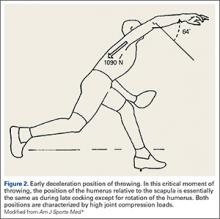

During arm deceleration, the shoulder achieves maximum internal rotation until reaching a neutral position and horizontally adducts across the body. This is controlled by contraction of the shoulder girdle musculature; the teres minor has the highest activity.3,4 The greatest forces produced during the throwing motion act at the shoulder and elbow during deceleration and can contribute to injury.2 These include compressive forces of greater than 1000 N, posterior shear forces of 400 N, and inferior shear forces of 300 N.4,7

The final phase, the follow-through phase, starts at shoulder maximum internal rotation and ends when the arm assumes a balanced position across the trunk. Lower extremity extension and trunk flexion help distribute forces throughout the body, taking stress away from the throwing arm. The posterior shoulder musculature and scapular protractors contribute to continued deceleration and muscle firing returns to resting levels. This complex motion of throwing fueled by the kinetic chain lasts less than 2 seconds and can result in ball release speeds as high as 100 miles per hour.3,4

Return to Throwing: Principles

Nonoperative and postoperative rehabilitation programs allow restoration of motion, strength, static and dynamic stability, and neuromuscular control. The initiation of an interval throwing program (ITP) is based on the assumption that tissue healing is complete and a complete physical examination has been conducted to the treating physician’s approval.11 An ITP progressively applies forces along the kinetic chain in a controlled manner through graduated throwing distances, while minimizing the risk of re-injury.

Reinold and colleagues12 described guidelines that were used in the development of the ITP.12 These factors include: (1) The act of throwing a baseball involves the transfer of energy from the feet up to the hand and therefore careful attention must be paid along the entire kinetic chain; (2) gradual progression of interval throwing decreases the chance for re-injury; (3) proper warm-up; and (4) proper throwing mechanics minimizes the chance of re-injury.

Variability. Unlike traditional rehabilitation programs that advance an athlete based on a specific timetable, the ITP requires that each level or phase to be completed pain-free or without complications prior to starting the next level. Therefore, an ITP can be used for overhead athletes of varying skill levels because progression will be different from one athlete to another. It is also important to have the athlete adhere strictly to the program, as over-eagerness to complete the ITP as quickly as possible can increase the chance of re-injury and thus slow the rehabilitation process.12

Warm-up. An adequate warm-up is recommended prior to initiating ITP. An athlete should jog or cycle to develop a light sweat and then progress to stretching and flexibility exercises. As emphasized before, throwing involves nearly all the muscles in the body. Therefore, all muscle groups should be stretched beginning with the legs and working distally along the kinetic chain.

Mechanics. Analysis, correction, and maintenance of proper throwing mechanics is essential throughout the early phases of rehabilitation and ITP. Improper pitching mechanics places increased stress on the throwing arm, potentially leading to re-injury. Therefore, it would be valuable to have a pitching coach available to emphasize proper mechanics throughout the rehabilitation process.

The Interval Throwing Program

For a PDF patient handout that summarizes the phases of this program, see Appendix 1.

Phase 1. We have adopted the ITP as described by Reinold and colleagues.12 Phase begins with the overhead athlete throwing on flat ground. He or she begins tossing from 45 feet and gradually progresses to 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 feet.

As discussed earlier, it is critical to use proper mechanics throughout the ITP. The “crow hop” method simulates a throwing act and helps maintain proper pitching mechanics. Crow hop has 3 components: hop, skip, and throw. Using this technique, the pitcher begins warm-up throws at a comfortable distance (generally 30 feet) and then progresses to the distance as indicated on the ITP. The athlete will then need to perform each step 2 times, with 1 day of rest between steps, before advancing to the next step. The ball should be thrown with an arc and have only enough momentum to reach the desired distance.

For example, Step 1 calls for the athlete to perform 2 sets of 25 throws at 45 feet, with adequate rest (5 minutes) between sets. This step will be repeated following 1 day of rest. If the athlete demonstrates the ability to throw at the prescribed distance without pain, he or she can progress to Step 2, which calls for 3 sets of 25 throws at 45 feet. If pain is present at any step, the thrower returns to the previous asymptomatic step and can progress once he is pain-free.

Positional players are instructed to complete Phase 1 prior to starting position-specific drills. Pitchers, on the other hand, are instructed to stop once they reach and complete 120 feet. They will then progress to tossing at progressive distances of 60, 90, and 120 feet, followed by throwing at 60 feet 6 inches with normal pitching mechanics, initiating straight line throws with little to no arc.

Phase II (Throwing off the Mound). Once a pitcher completes Phase 1 without pain or complications, he is ready to begin throwing off the mound. The same principle remains in Phase 2: pitchers must complete each step pain-free before advancing to the next stage. Pitchers should first throw fastballs at 50% effort and progress to 75% and 100% effort. Because athletes often find it difficult to gauge their own effort, it is important to emphasize the importance of strictly adhering to the program. Fleisig and colleagues13 studied healthy pitchers’ ability to estimate their throwing effort. When targeting 50% effort, athletes generated ball speeds of 85% with forces and torque approaching 75% of maximum. A radar gun may be valuable in guiding effort control.

As the player advances through Phase 2, he will increase the volume of pitches as well as the effort in a gradual manner. The player may introduce breaking ball pitches once he demonstrates the ability to throw light batting practice. Phase 2 concludes with the pitcher throwing simulated games, progressing by 15 throws per workout.

Hitting

Biomechanics Overview

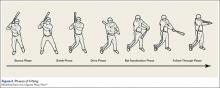

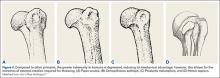

The mechanics of hitting a baseball can be broken down into 6 phases: the preparatory phase, stance phase, stride phase, drive phase, bat acceleration phase, and follow-through phase.14 While progressing through a return-to-play protocol, it is important to understand and teach the player proper swing mechanics during each phase in order to minimize the risk of re-injury (Figure 2).

The preparatory phase occurs as the player positions himself into the batter’s box. This phase is highly individualized, depending on each player’s personal preference. Though significant variability in approach exists, there are 3 basic stances a player can take in preparation to bat. In the closed stance, the batter’s front foot is positioned closer to the plate than the back foot. A more popular stance is the open stance, where the player’s back foot is placed closer to the plate than the front foot. The square batting stance is the most common stance. This stance is where both feet are in line with the pitcher and parallel with the edge of the batter’s box. Most authors agree that the square stance is the optimal position because it provides batters the best opportunity to hit pitches anywhere in the strike zone and limits compensatory or extra motion to their swing.15

Once the player begins the swing, he has entered the loading period, which is divided into the stance, stride, and drive phases. The loading period, also known as coiling or triggering, begins as the athlete eccentrically stretches agonist muscles and rotates the body away from the incoming ball. The elastic energy stored during this stretching is released during the concentric contraction of the same muscles and transferred through the entire kinetic chain as different segments of the body are rotated; it culminates in effort directed at hitting the baseball.16

In each phase of the loading period, certain critical motions should be monitored and corrected in order to return the player to his previous level of competition. Stride length has been shown to be critical in the timing of a batter’s swing. A short stride length can cause early initiation of the swing, while a longer stride can produce delayed activation of hip rotation. As the player enters the drive phase, he should have increased elbow flexion in the back elbow compared to the front elbow. The bat should be placed at a position approximately 45° in the frontal plane, and the bat should bisect the batter’s helmet. The back elbow should be down, both upper extremities should be positioned close to the hitter’s body, and the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands should align on the handle of the bat. Athletic trainers and coaches should be aware that subtle compensations due to deficits during these movements could cause injury during the swing by disrupting the body’s natural motion.

The bat acceleration phase occurs from maximal bat loading through striking the ball. In this time, the linear force that has been exerted by the player must be transferred into rotational force through the trunk and upper extremities. When the lead leg contacts the ground, the player has created a closed kinetic chain, where the elastic energy gathered during the loading period is used to produce segmental rotation beginning in the hips and rising through the trunk and out to the arms and hands, finally producing contact with the baseball.16 To produce effective bat velocity, each segment must rotate in a sequential manner. If the upper extremities reach peak velocity before any lower segment, then the player has lost the ability to efficiently transfer kinetic energy up the kinetic chain.

Finally, the follow-through phase occurs after contact with the baseball and ends with complete deceleration, completing the swing. In order to achieve optimal effort, full hip rotation is needed, which is aided by rotation of the trail foot. Both hips and back laces should face the pitcher upon completion of the swing producing maximum power output.15

Return to Hitting: Principles

As with the initiation of the ITP, an interval hitting protocol (IHP) is designed to begin only after the player has been assessed on impairment measures, physical performance measures, and self-assessment.17 The player should have minimum to no pain, have no tenderness to palpation, and show adequate range of motion and strength to meet the demands of performing a full hitting cycle.12 It is recommended that before beginning a return-to-play protocol, the involved extremity should be at least 80% as strong as the uninvolved extremity.18 Physical measures challenging an athlete’s ability to perform tasks specific to hitting a baseball must also be considered through standardized examinations of the involved area.19 Finally, the athlete’s self-perception of functional abilities must be taken into account. This gives a subjective account of what the hitter perceives they are able to perform, providing useful insight into whether they are mentally prepared to participate in the protocol.

Like the ITP, progression through the IHP is also based on the player’s level of pain and soreness rather than following a specific timetable (Table). The program features a 1 day on, 1 day off schedule during which the player completes 1 step per day. The athlete must remain pain-free to progress to the next step and monitor his level of soreness during their workout. If pain or soreness persists, the player should rest for 2 days and be reevaluated upon return.17

The same principles of proper warm-up and mechanics apply in the IHP. An athlete should jog or cycle for a minimum of 10 minutes and perform stretching exercises focused on both upper and lower extremity muscles, as batting involves whole body movement. As the athlete progresses through the IHP, having a hitting coach to analyze, correct and maintain proper swing mechanics is valuable in enhancing performance as well as decreasing risk of re-injury.

The Interval Hitting Program

For a PDF patient handout that summarizes the phases of this program, see Appendix 2.

Phase 1 (Dry Swings). Only the most basic fundamentals are stressed during this phase. The player should focus on properly moving from one phase of the swing to the next, without the goal of hitting the baseball. Trainers should measure critical points in the swing and correct deficits early.

Phase 2 (Batting Off a Tee). In this phase, the player is reintroduced to batting at low intensity with a fixed position target. The initial steps have the batter swing in a position of greatest comfort and natural movement, while the final steps in this phase test the athlete’s range of motion and confidence in the previous, healed injury.

Phase 3 (Soft Toss). As the player progresses to this phase, a baseball with trajectory is used to simulate differences in placement of pitches used during a game. As the hitter is able to pick up differences in target position, his performance and confidence should both increase.20 The coach should sit about 30 feet away, facing the hitter at an angle of 45°, and toss the ball in an underhand motion.

Phase 4 (Simulated Hitting). In this phase, the player and coach should focus on the timing of sequential body movements in order to elicit proper loading and force production. With the randomized pitch delivery and increased velocity, the hitter will practice against pitches similar to those delivered in competition.

Conclusion

Interval throwing and hitting programs are designed to allow the athlete to return to competition through a gradual, stepwise program. This permits the player to prepare his body for the unique stresses associated with throwing and hitting. The medical personnel should familiarize themselves with the philosophy of the interval throwing and hitting programs and individualize them to each athlete. Emphasis on proper warm-up, mechanics, and effort control is paramount in expediting return to play while preventing re-injury.

1. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402-408.

2. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

3. Fleisig GS, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of overhand throwing with implications for injuries. Sports Med Auckl NZ. 1996;21(6):421-437.

4. Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: Biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(2):265-275.

5. Kaczmarek PK, Lubiatowski P, Cisowski P, et al. Shoulder problems in overhead sports. Part I - biomechanics of throwing. Pol Orthop Traumatol. 2014;79:50-58.

6. Toyoshima S, Hoshikawa T, Miyashita M, Oguri T. Contribution of the body parts to throwing performance. Biomech IV. 1974;5:169-174.

7. Weber AE, Kontaxis A, O’Brien SJ, Bedi A. The biomechanics of throwing: simplified and cogent. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2014;22(2):72-79.

8. Werner SL, Fleisig GS, Dillman CJ, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of the elbow during baseball pitching. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(6):274-278.

9. Chang ES, Greco NJ, McClincy MP, Bradley JP. Posterior shoulder instability in overhead athletes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):179-187.

10. Digiovine NM, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J. An electromyographic analysis of the upper extremity in pitching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(1):15-25.

11. Axe M, Hurd W, Snyder-Mackler L. Data-based interval throwing programs for baseball players. Sports Health. 2009;1(2):145-153.

12. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Reed J, Crenshaw K, Andrews JR. Interval sport programs: guidelines for baseball, tennis, and golf. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(6):293-298.

13. Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR, Lemak LF. Kinematic and kinetic comparison of full and partial effort baseball pitching. Conference proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Biomechanics; 1996:151-152.

14. Fleisig GS, Hsu WK, Fortenbaugh D, Cordover A, Press JM. Trunk axial rotation in baseball pitching and batting. Sports Biomech. 2013;12(4):324-333.

15. Monti R. Return to hitting: an interval hitting progression and overview of hitting mechanics following injury. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(7):1059-1073.

16. Welch CM, Banks SA, Cook FF, Draovitch P. Hitting a baseball: a biomechanical description. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22(5):193-201.

17. Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Konin JG, Strube MJ. Development of a distance-based interval throwing program for Little League-aged athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(5):594-602.

18. Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Proposed practice guidelines for nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation of physically active individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(4):194-203.

19. Hegedus EJ, McDonough S, Bleakley C, Cook CE, Baxter GD. Clinician-friendly lower extremity physical performance measures in athletes: a systematic review of measurement properties and correlation with injury, part 1. The tests for knee function including the hop tests. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(10):642-648.

20. Higuchi T, Nagami T, Morohoshi J, Nakata H, Kanosue K. Disturbance in hitting accuracy by professional and collegiate baseball players due to intentional change of target position. Percept Mot Skills. 2013;116(2):627-639.

Throwing and batting each require repetitive motions that can result in injuries unique to baseball. Fortuantely, advances in operative and nonoperative treatments have allowed players to return to competition after sustaining what previously would have been considered a career-ending injury. Once a player has been deemed ready to return to throwing or hitting, a comprehensive, multiphased approach to rehabilitation is necessary to reintroduce the athlete back to baseball activities and avoid re-injury. This article reviews the biomechanics of both throwing and hitting, and outlines the phases of rehabilitation necessary to allow the athlete to return to competition.

Throwing

Biomechanical Overview

The overhead throwing motion is complex and involves full body coordination from the initial force generation through the follow-through phase of throwing. The “kinetic chain”—the concept that movements in the body are connected through segments culminating with the highest energy in the final segment—is paramount to achieving the force and energy needed for throwing.1-8 The kinetic chain begins in the lower body and trunk and transmits the energy distally to the shoulder, elbow, and hand, ending with kinetic energy transfer to the ball.3-5,7 The progression of motion through the kinetic chain during throwing includes stride, pelvis rotation, upper torso rotation, elbow extension, shoulder internal rotation, and wrist flexion. Disruptions in this chain due to muscle imbalance or weakness can lead to injury downstream, particularly in the upper extremity.3,7,9

The importance of the kinetic chain can be highlighted in the 6 phases of throwing motion. These include wind-up, early arm cocking, late arm cocking, arm acceleration, arm deceleration, and follow-through (Figure 1).1,2,9,10

The wind-up phase starts with initiation of motion and ends with maximal knee lift of the lead leg; its objective is to place the body in an optimal stance to throw.3-5,7 There are minimal forces, torques, and muscle activity in the upper extremity during this phase, but up to 50% of throw speed is created through stride and trunk rotation.6 During the early cocking phase, the thrower keeps his stance foot planted and drives his lead leg towards the target, while bringing both arms into abduction. This is coupled with internal rotation of the stance hip, external rotation of the lead hip, and external rotation of the throwing shoulder. This creates linear velocity by maximizing the length of the elastic components of the body. Elbow, wrist, and finger extensors are also contracting during this phase to control elbow flexion and wrist hyperextension.3

The late cocking phase begins when the lead foot contacts the ground and ends with maximum shoulder external rotation.3-5 Lead foot contact is followed by quadriceps contraction to decelerate and stabilize the lead leg. This is followed by rotation of the pelvis and upper torso. The result is energy transfer to the throwing arm with a shear force across the anterior shoulder of 400 N.4 The shoulder stays in 90° of abduction, 15° of horizontal adduction, and externally rotates to between 150° and 180°. This produces a maximum horizontal adduction moment of 100 N.m and internal rotation torque of 70 N.m.4 Simultaneously, the elbow generates maximum flexion and a 65 N.m varus torque.7 Forces about the elbow are generated to resist the large angular velocity experienced (up to 3000°/second). This places an extreme amount of valgus stress along the medial elbow, particularly on the ulnar collateral ligament. The shoulder girdle and rotator cuff muscles simultaneously act to stabilize the scapula and glenohumeral joint.

The arm acceleration phase is from maximal shoulder external rotation until ball release.3-5 In this phase, the thrower flexes his trunk from an extended position, returning to neutral by the time of ball release while the lead leg straightens. The shoulder stays abducted at 90° throughout while the rotator cuff internal rotators and scapular stabilizers contract to explosively internally rotate the shoulder, creating a maximal internal rotation velocity greater than 7000°/second by ball release.1,4,7 The elbow also begins to extend, reaching maximum velocity during mid-acceleration phase from a combination of triceps contraction and torque generated from rotation at the shoulder and upper trunk.3 Finally, the wrist flexors contract to move the wrist to a neutral position from hyperextension as the ball is released.

During arm deceleration, the shoulder achieves maximum internal rotation until reaching a neutral position and horizontally adducts across the body. This is controlled by contraction of the shoulder girdle musculature; the teres minor has the highest activity.3,4 The greatest forces produced during the throwing motion act at the shoulder and elbow during deceleration and can contribute to injury.2 These include compressive forces of greater than 1000 N, posterior shear forces of 400 N, and inferior shear forces of 300 N.4,7

The final phase, the follow-through phase, starts at shoulder maximum internal rotation and ends when the arm assumes a balanced position across the trunk. Lower extremity extension and trunk flexion help distribute forces throughout the body, taking stress away from the throwing arm. The posterior shoulder musculature and scapular protractors contribute to continued deceleration and muscle firing returns to resting levels. This complex motion of throwing fueled by the kinetic chain lasts less than 2 seconds and can result in ball release speeds as high as 100 miles per hour.3,4

Return to Throwing: Principles

Nonoperative and postoperative rehabilitation programs allow restoration of motion, strength, static and dynamic stability, and neuromuscular control. The initiation of an interval throwing program (ITP) is based on the assumption that tissue healing is complete and a complete physical examination has been conducted to the treating physician’s approval.11 An ITP progressively applies forces along the kinetic chain in a controlled manner through graduated throwing distances, while minimizing the risk of re-injury.

Reinold and colleagues12 described guidelines that were used in the development of the ITP.12 These factors include: (1) The act of throwing a baseball involves the transfer of energy from the feet up to the hand and therefore careful attention must be paid along the entire kinetic chain; (2) gradual progression of interval throwing decreases the chance for re-injury; (3) proper warm-up; and (4) proper throwing mechanics minimizes the chance of re-injury.

Variability. Unlike traditional rehabilitation programs that advance an athlete based on a specific timetable, the ITP requires that each level or phase to be completed pain-free or without complications prior to starting the next level. Therefore, an ITP can be used for overhead athletes of varying skill levels because progression will be different from one athlete to another. It is also important to have the athlete adhere strictly to the program, as over-eagerness to complete the ITP as quickly as possible can increase the chance of re-injury and thus slow the rehabilitation process.12

Warm-up. An adequate warm-up is recommended prior to initiating ITP. An athlete should jog or cycle to develop a light sweat and then progress to stretching and flexibility exercises. As emphasized before, throwing involves nearly all the muscles in the body. Therefore, all muscle groups should be stretched beginning with the legs and working distally along the kinetic chain.

Mechanics. Analysis, correction, and maintenance of proper throwing mechanics is essential throughout the early phases of rehabilitation and ITP. Improper pitching mechanics places increased stress on the throwing arm, potentially leading to re-injury. Therefore, it would be valuable to have a pitching coach available to emphasize proper mechanics throughout the rehabilitation process.

The Interval Throwing Program

For a PDF patient handout that summarizes the phases of this program, see Appendix 1.

Phase 1. We have adopted the ITP as described by Reinold and colleagues.12 Phase begins with the overhead athlete throwing on flat ground. He or she begins tossing from 45 feet and gradually progresses to 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 feet.

As discussed earlier, it is critical to use proper mechanics throughout the ITP. The “crow hop” method simulates a throwing act and helps maintain proper pitching mechanics. Crow hop has 3 components: hop, skip, and throw. Using this technique, the pitcher begins warm-up throws at a comfortable distance (generally 30 feet) and then progresses to the distance as indicated on the ITP. The athlete will then need to perform each step 2 times, with 1 day of rest between steps, before advancing to the next step. The ball should be thrown with an arc and have only enough momentum to reach the desired distance.

For example, Step 1 calls for the athlete to perform 2 sets of 25 throws at 45 feet, with adequate rest (5 minutes) between sets. This step will be repeated following 1 day of rest. If the athlete demonstrates the ability to throw at the prescribed distance without pain, he or she can progress to Step 2, which calls for 3 sets of 25 throws at 45 feet. If pain is present at any step, the thrower returns to the previous asymptomatic step and can progress once he is pain-free.

Positional players are instructed to complete Phase 1 prior to starting position-specific drills. Pitchers, on the other hand, are instructed to stop once they reach and complete 120 feet. They will then progress to tossing at progressive distances of 60, 90, and 120 feet, followed by throwing at 60 feet 6 inches with normal pitching mechanics, initiating straight line throws with little to no arc.

Phase II (Throwing off the Mound). Once a pitcher completes Phase 1 without pain or complications, he is ready to begin throwing off the mound. The same principle remains in Phase 2: pitchers must complete each step pain-free before advancing to the next stage. Pitchers should first throw fastballs at 50% effort and progress to 75% and 100% effort. Because athletes often find it difficult to gauge their own effort, it is important to emphasize the importance of strictly adhering to the program. Fleisig and colleagues13 studied healthy pitchers’ ability to estimate their throwing effort. When targeting 50% effort, athletes generated ball speeds of 85% with forces and torque approaching 75% of maximum. A radar gun may be valuable in guiding effort control.

As the player advances through Phase 2, he will increase the volume of pitches as well as the effort in a gradual manner. The player may introduce breaking ball pitches once he demonstrates the ability to throw light batting practice. Phase 2 concludes with the pitcher throwing simulated games, progressing by 15 throws per workout.

Hitting

Biomechanics Overview

The mechanics of hitting a baseball can be broken down into 6 phases: the preparatory phase, stance phase, stride phase, drive phase, bat acceleration phase, and follow-through phase.14 While progressing through a return-to-play protocol, it is important to understand and teach the player proper swing mechanics during each phase in order to minimize the risk of re-injury (Figure 2).

The preparatory phase occurs as the player positions himself into the batter’s box. This phase is highly individualized, depending on each player’s personal preference. Though significant variability in approach exists, there are 3 basic stances a player can take in preparation to bat. In the closed stance, the batter’s front foot is positioned closer to the plate than the back foot. A more popular stance is the open stance, where the player’s back foot is placed closer to the plate than the front foot. The square batting stance is the most common stance. This stance is where both feet are in line with the pitcher and parallel with the edge of the batter’s box. Most authors agree that the square stance is the optimal position because it provides batters the best opportunity to hit pitches anywhere in the strike zone and limits compensatory or extra motion to their swing.15

Once the player begins the swing, he has entered the loading period, which is divided into the stance, stride, and drive phases. The loading period, also known as coiling or triggering, begins as the athlete eccentrically stretches agonist muscles and rotates the body away from the incoming ball. The elastic energy stored during this stretching is released during the concentric contraction of the same muscles and transferred through the entire kinetic chain as different segments of the body are rotated; it culminates in effort directed at hitting the baseball.16

In each phase of the loading period, certain critical motions should be monitored and corrected in order to return the player to his previous level of competition. Stride length has been shown to be critical in the timing of a batter’s swing. A short stride length can cause early initiation of the swing, while a longer stride can produce delayed activation of hip rotation. As the player enters the drive phase, he should have increased elbow flexion in the back elbow compared to the front elbow. The bat should be placed at a position approximately 45° in the frontal plane, and the bat should bisect the batter’s helmet. The back elbow should be down, both upper extremities should be positioned close to the hitter’s body, and the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands should align on the handle of the bat. Athletic trainers and coaches should be aware that subtle compensations due to deficits during these movements could cause injury during the swing by disrupting the body’s natural motion.

The bat acceleration phase occurs from maximal bat loading through striking the ball. In this time, the linear force that has been exerted by the player must be transferred into rotational force through the trunk and upper extremities. When the lead leg contacts the ground, the player has created a closed kinetic chain, where the elastic energy gathered during the loading period is used to produce segmental rotation beginning in the hips and rising through the trunk and out to the arms and hands, finally producing contact with the baseball.16 To produce effective bat velocity, each segment must rotate in a sequential manner. If the upper extremities reach peak velocity before any lower segment, then the player has lost the ability to efficiently transfer kinetic energy up the kinetic chain.

Finally, the follow-through phase occurs after contact with the baseball and ends with complete deceleration, completing the swing. In order to achieve optimal effort, full hip rotation is needed, which is aided by rotation of the trail foot. Both hips and back laces should face the pitcher upon completion of the swing producing maximum power output.15

Return to Hitting: Principles

As with the initiation of the ITP, an interval hitting protocol (IHP) is designed to begin only after the player has been assessed on impairment measures, physical performance measures, and self-assessment.17 The player should have minimum to no pain, have no tenderness to palpation, and show adequate range of motion and strength to meet the demands of performing a full hitting cycle.12 It is recommended that before beginning a return-to-play protocol, the involved extremity should be at least 80% as strong as the uninvolved extremity.18 Physical measures challenging an athlete’s ability to perform tasks specific to hitting a baseball must also be considered through standardized examinations of the involved area.19 Finally, the athlete’s self-perception of functional abilities must be taken into account. This gives a subjective account of what the hitter perceives they are able to perform, providing useful insight into whether they are mentally prepared to participate in the protocol.

Like the ITP, progression through the IHP is also based on the player’s level of pain and soreness rather than following a specific timetable (Table). The program features a 1 day on, 1 day off schedule during which the player completes 1 step per day. The athlete must remain pain-free to progress to the next step and monitor his level of soreness during their workout. If pain or soreness persists, the player should rest for 2 days and be reevaluated upon return.17

The same principles of proper warm-up and mechanics apply in the IHP. An athlete should jog or cycle for a minimum of 10 minutes and perform stretching exercises focused on both upper and lower extremity muscles, as batting involves whole body movement. As the athlete progresses through the IHP, having a hitting coach to analyze, correct and maintain proper swing mechanics is valuable in enhancing performance as well as decreasing risk of re-injury.

The Interval Hitting Program

For a PDF patient handout that summarizes the phases of this program, see Appendix 2.

Phase 1 (Dry Swings). Only the most basic fundamentals are stressed during this phase. The player should focus on properly moving from one phase of the swing to the next, without the goal of hitting the baseball. Trainers should measure critical points in the swing and correct deficits early.

Phase 2 (Batting Off a Tee). In this phase, the player is reintroduced to batting at low intensity with a fixed position target. The initial steps have the batter swing in a position of greatest comfort and natural movement, while the final steps in this phase test the athlete’s range of motion and confidence in the previous, healed injury.

Phase 3 (Soft Toss). As the player progresses to this phase, a baseball with trajectory is used to simulate differences in placement of pitches used during a game. As the hitter is able to pick up differences in target position, his performance and confidence should both increase.20 The coach should sit about 30 feet away, facing the hitter at an angle of 45°, and toss the ball in an underhand motion.

Phase 4 (Simulated Hitting). In this phase, the player and coach should focus on the timing of sequential body movements in order to elicit proper loading and force production. With the randomized pitch delivery and increased velocity, the hitter will practice against pitches similar to those delivered in competition.

Conclusion

Interval throwing and hitting programs are designed to allow the athlete to return to competition through a gradual, stepwise program. This permits the player to prepare his body for the unique stresses associated with throwing and hitting. The medical personnel should familiarize themselves with the philosophy of the interval throwing and hitting programs and individualize them to each athlete. Emphasis on proper warm-up, mechanics, and effort control is paramount in expediting return to play while preventing re-injury.

Throwing and batting each require repetitive motions that can result in injuries unique to baseball. Fortuantely, advances in operative and nonoperative treatments have allowed players to return to competition after sustaining what previously would have been considered a career-ending injury. Once a player has been deemed ready to return to throwing or hitting, a comprehensive, multiphased approach to rehabilitation is necessary to reintroduce the athlete back to baseball activities and avoid re-injury. This article reviews the biomechanics of both throwing and hitting, and outlines the phases of rehabilitation necessary to allow the athlete to return to competition.

Throwing

Biomechanical Overview

The overhead throwing motion is complex and involves full body coordination from the initial force generation through the follow-through phase of throwing. The “kinetic chain”—the concept that movements in the body are connected through segments culminating with the highest energy in the final segment—is paramount to achieving the force and energy needed for throwing.1-8 The kinetic chain begins in the lower body and trunk and transmits the energy distally to the shoulder, elbow, and hand, ending with kinetic energy transfer to the ball.3-5,7 The progression of motion through the kinetic chain during throwing includes stride, pelvis rotation, upper torso rotation, elbow extension, shoulder internal rotation, and wrist flexion. Disruptions in this chain due to muscle imbalance or weakness can lead to injury downstream, particularly in the upper extremity.3,7,9

The importance of the kinetic chain can be highlighted in the 6 phases of throwing motion. These include wind-up, early arm cocking, late arm cocking, arm acceleration, arm deceleration, and follow-through (Figure 1).1,2,9,10

The wind-up phase starts with initiation of motion and ends with maximal knee lift of the lead leg; its objective is to place the body in an optimal stance to throw.3-5,7 There are minimal forces, torques, and muscle activity in the upper extremity during this phase, but up to 50% of throw speed is created through stride and trunk rotation.6 During the early cocking phase, the thrower keeps his stance foot planted and drives his lead leg towards the target, while bringing both arms into abduction. This is coupled with internal rotation of the stance hip, external rotation of the lead hip, and external rotation of the throwing shoulder. This creates linear velocity by maximizing the length of the elastic components of the body. Elbow, wrist, and finger extensors are also contracting during this phase to control elbow flexion and wrist hyperextension.3

The late cocking phase begins when the lead foot contacts the ground and ends with maximum shoulder external rotation.3-5 Lead foot contact is followed by quadriceps contraction to decelerate and stabilize the lead leg. This is followed by rotation of the pelvis and upper torso. The result is energy transfer to the throwing arm with a shear force across the anterior shoulder of 400 N.4 The shoulder stays in 90° of abduction, 15° of horizontal adduction, and externally rotates to between 150° and 180°. This produces a maximum horizontal adduction moment of 100 N.m and internal rotation torque of 70 N.m.4 Simultaneously, the elbow generates maximum flexion and a 65 N.m varus torque.7 Forces about the elbow are generated to resist the large angular velocity experienced (up to 3000°/second). This places an extreme amount of valgus stress along the medial elbow, particularly on the ulnar collateral ligament. The shoulder girdle and rotator cuff muscles simultaneously act to stabilize the scapula and glenohumeral joint.

The arm acceleration phase is from maximal shoulder external rotation until ball release.3-5 In this phase, the thrower flexes his trunk from an extended position, returning to neutral by the time of ball release while the lead leg straightens. The shoulder stays abducted at 90° throughout while the rotator cuff internal rotators and scapular stabilizers contract to explosively internally rotate the shoulder, creating a maximal internal rotation velocity greater than 7000°/second by ball release.1,4,7 The elbow also begins to extend, reaching maximum velocity during mid-acceleration phase from a combination of triceps contraction and torque generated from rotation at the shoulder and upper trunk.3 Finally, the wrist flexors contract to move the wrist to a neutral position from hyperextension as the ball is released.

During arm deceleration, the shoulder achieves maximum internal rotation until reaching a neutral position and horizontally adducts across the body. This is controlled by contraction of the shoulder girdle musculature; the teres minor has the highest activity.3,4 The greatest forces produced during the throwing motion act at the shoulder and elbow during deceleration and can contribute to injury.2 These include compressive forces of greater than 1000 N, posterior shear forces of 400 N, and inferior shear forces of 300 N.4,7

The final phase, the follow-through phase, starts at shoulder maximum internal rotation and ends when the arm assumes a balanced position across the trunk. Lower extremity extension and trunk flexion help distribute forces throughout the body, taking stress away from the throwing arm. The posterior shoulder musculature and scapular protractors contribute to continued deceleration and muscle firing returns to resting levels. This complex motion of throwing fueled by the kinetic chain lasts less than 2 seconds and can result in ball release speeds as high as 100 miles per hour.3,4

Return to Throwing: Principles

Nonoperative and postoperative rehabilitation programs allow restoration of motion, strength, static and dynamic stability, and neuromuscular control. The initiation of an interval throwing program (ITP) is based on the assumption that tissue healing is complete and a complete physical examination has been conducted to the treating physician’s approval.11 An ITP progressively applies forces along the kinetic chain in a controlled manner through graduated throwing distances, while minimizing the risk of re-injury.

Reinold and colleagues12 described guidelines that were used in the development of the ITP.12 These factors include: (1) The act of throwing a baseball involves the transfer of energy from the feet up to the hand and therefore careful attention must be paid along the entire kinetic chain; (2) gradual progression of interval throwing decreases the chance for re-injury; (3) proper warm-up; and (4) proper throwing mechanics minimizes the chance of re-injury.

Variability. Unlike traditional rehabilitation programs that advance an athlete based on a specific timetable, the ITP requires that each level or phase to be completed pain-free or without complications prior to starting the next level. Therefore, an ITP can be used for overhead athletes of varying skill levels because progression will be different from one athlete to another. It is also important to have the athlete adhere strictly to the program, as over-eagerness to complete the ITP as quickly as possible can increase the chance of re-injury and thus slow the rehabilitation process.12

Warm-up. An adequate warm-up is recommended prior to initiating ITP. An athlete should jog or cycle to develop a light sweat and then progress to stretching and flexibility exercises. As emphasized before, throwing involves nearly all the muscles in the body. Therefore, all muscle groups should be stretched beginning with the legs and working distally along the kinetic chain.

Mechanics. Analysis, correction, and maintenance of proper throwing mechanics is essential throughout the early phases of rehabilitation and ITP. Improper pitching mechanics places increased stress on the throwing arm, potentially leading to re-injury. Therefore, it would be valuable to have a pitching coach available to emphasize proper mechanics throughout the rehabilitation process.

The Interval Throwing Program

For a PDF patient handout that summarizes the phases of this program, see Appendix 1.

Phase 1. We have adopted the ITP as described by Reinold and colleagues.12 Phase begins with the overhead athlete throwing on flat ground. He or she begins tossing from 45 feet and gradually progresses to 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 feet.

As discussed earlier, it is critical to use proper mechanics throughout the ITP. The “crow hop” method simulates a throwing act and helps maintain proper pitching mechanics. Crow hop has 3 components: hop, skip, and throw. Using this technique, the pitcher begins warm-up throws at a comfortable distance (generally 30 feet) and then progresses to the distance as indicated on the ITP. The athlete will then need to perform each step 2 times, with 1 day of rest between steps, before advancing to the next step. The ball should be thrown with an arc and have only enough momentum to reach the desired distance.

For example, Step 1 calls for the athlete to perform 2 sets of 25 throws at 45 feet, with adequate rest (5 minutes) between sets. This step will be repeated following 1 day of rest. If the athlete demonstrates the ability to throw at the prescribed distance without pain, he or she can progress to Step 2, which calls for 3 sets of 25 throws at 45 feet. If pain is present at any step, the thrower returns to the previous asymptomatic step and can progress once he is pain-free.

Positional players are instructed to complete Phase 1 prior to starting position-specific drills. Pitchers, on the other hand, are instructed to stop once they reach and complete 120 feet. They will then progress to tossing at progressive distances of 60, 90, and 120 feet, followed by throwing at 60 feet 6 inches with normal pitching mechanics, initiating straight line throws with little to no arc.

Phase II (Throwing off the Mound). Once a pitcher completes Phase 1 without pain or complications, he is ready to begin throwing off the mound. The same principle remains in Phase 2: pitchers must complete each step pain-free before advancing to the next stage. Pitchers should first throw fastballs at 50% effort and progress to 75% and 100% effort. Because athletes often find it difficult to gauge their own effort, it is important to emphasize the importance of strictly adhering to the program. Fleisig and colleagues13 studied healthy pitchers’ ability to estimate their throwing effort. When targeting 50% effort, athletes generated ball speeds of 85% with forces and torque approaching 75% of maximum. A radar gun may be valuable in guiding effort control.

As the player advances through Phase 2, he will increase the volume of pitches as well as the effort in a gradual manner. The player may introduce breaking ball pitches once he demonstrates the ability to throw light batting practice. Phase 2 concludes with the pitcher throwing simulated games, progressing by 15 throws per workout.

Hitting

Biomechanics Overview

The mechanics of hitting a baseball can be broken down into 6 phases: the preparatory phase, stance phase, stride phase, drive phase, bat acceleration phase, and follow-through phase.14 While progressing through a return-to-play protocol, it is important to understand and teach the player proper swing mechanics during each phase in order to minimize the risk of re-injury (Figure 2).

The preparatory phase occurs as the player positions himself into the batter’s box. This phase is highly individualized, depending on each player’s personal preference. Though significant variability in approach exists, there are 3 basic stances a player can take in preparation to bat. In the closed stance, the batter’s front foot is positioned closer to the plate than the back foot. A more popular stance is the open stance, where the player’s back foot is placed closer to the plate than the front foot. The square batting stance is the most common stance. This stance is where both feet are in line with the pitcher and parallel with the edge of the batter’s box. Most authors agree that the square stance is the optimal position because it provides batters the best opportunity to hit pitches anywhere in the strike zone and limits compensatory or extra motion to their swing.15

Once the player begins the swing, he has entered the loading period, which is divided into the stance, stride, and drive phases. The loading period, also known as coiling or triggering, begins as the athlete eccentrically stretches agonist muscles and rotates the body away from the incoming ball. The elastic energy stored during this stretching is released during the concentric contraction of the same muscles and transferred through the entire kinetic chain as different segments of the body are rotated; it culminates in effort directed at hitting the baseball.16

In each phase of the loading period, certain critical motions should be monitored and corrected in order to return the player to his previous level of competition. Stride length has been shown to be critical in the timing of a batter’s swing. A short stride length can cause early initiation of the swing, while a longer stride can produce delayed activation of hip rotation. As the player enters the drive phase, he should have increased elbow flexion in the back elbow compared to the front elbow. The bat should be placed at a position approximately 45° in the frontal plane, and the bat should bisect the batter’s helmet. The back elbow should be down, both upper extremities should be positioned close to the hitter’s body, and the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands should align on the handle of the bat. Athletic trainers and coaches should be aware that subtle compensations due to deficits during these movements could cause injury during the swing by disrupting the body’s natural motion.

The bat acceleration phase occurs from maximal bat loading through striking the ball. In this time, the linear force that has been exerted by the player must be transferred into rotational force through the trunk and upper extremities. When the lead leg contacts the ground, the player has created a closed kinetic chain, where the elastic energy gathered during the loading period is used to produce segmental rotation beginning in the hips and rising through the trunk and out to the arms and hands, finally producing contact with the baseball.16 To produce effective bat velocity, each segment must rotate in a sequential manner. If the upper extremities reach peak velocity before any lower segment, then the player has lost the ability to efficiently transfer kinetic energy up the kinetic chain.

Finally, the follow-through phase occurs after contact with the baseball and ends with complete deceleration, completing the swing. In order to achieve optimal effort, full hip rotation is needed, which is aided by rotation of the trail foot. Both hips and back laces should face the pitcher upon completion of the swing producing maximum power output.15

Return to Hitting: Principles

As with the initiation of the ITP, an interval hitting protocol (IHP) is designed to begin only after the player has been assessed on impairment measures, physical performance measures, and self-assessment.17 The player should have minimum to no pain, have no tenderness to palpation, and show adequate range of motion and strength to meet the demands of performing a full hitting cycle.12 It is recommended that before beginning a return-to-play protocol, the involved extremity should be at least 80% as strong as the uninvolved extremity.18 Physical measures challenging an athlete’s ability to perform tasks specific to hitting a baseball must also be considered through standardized examinations of the involved area.19 Finally, the athlete’s self-perception of functional abilities must be taken into account. This gives a subjective account of what the hitter perceives they are able to perform, providing useful insight into whether they are mentally prepared to participate in the protocol.

Like the ITP, progression through the IHP is also based on the player’s level of pain and soreness rather than following a specific timetable (Table). The program features a 1 day on, 1 day off schedule during which the player completes 1 step per day. The athlete must remain pain-free to progress to the next step and monitor his level of soreness during their workout. If pain or soreness persists, the player should rest for 2 days and be reevaluated upon return.17

The same principles of proper warm-up and mechanics apply in the IHP. An athlete should jog or cycle for a minimum of 10 minutes and perform stretching exercises focused on both upper and lower extremity muscles, as batting involves whole body movement. As the athlete progresses through the IHP, having a hitting coach to analyze, correct and maintain proper swing mechanics is valuable in enhancing performance as well as decreasing risk of re-injury.

The Interval Hitting Program

For a PDF patient handout that summarizes the phases of this program, see Appendix 2.

Phase 1 (Dry Swings). Only the most basic fundamentals are stressed during this phase. The player should focus on properly moving from one phase of the swing to the next, without the goal of hitting the baseball. Trainers should measure critical points in the swing and correct deficits early.

Phase 2 (Batting Off a Tee). In this phase, the player is reintroduced to batting at low intensity with a fixed position target. The initial steps have the batter swing in a position of greatest comfort and natural movement, while the final steps in this phase test the athlete’s range of motion and confidence in the previous, healed injury.

Phase 3 (Soft Toss). As the player progresses to this phase, a baseball with trajectory is used to simulate differences in placement of pitches used during a game. As the hitter is able to pick up differences in target position, his performance and confidence should both increase.20 The coach should sit about 30 feet away, facing the hitter at an angle of 45°, and toss the ball in an underhand motion.

Phase 4 (Simulated Hitting). In this phase, the player and coach should focus on the timing of sequential body movements in order to elicit proper loading and force production. With the randomized pitch delivery and increased velocity, the hitter will practice against pitches similar to those delivered in competition.

Conclusion

Interval throwing and hitting programs are designed to allow the athlete to return to competition through a gradual, stepwise program. This permits the player to prepare his body for the unique stresses associated with throwing and hitting. The medical personnel should familiarize themselves with the philosophy of the interval throwing and hitting programs and individualize them to each athlete. Emphasis on proper warm-up, mechanics, and effort control is paramount in expediting return to play while preventing re-injury.

1. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402-408.

2. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

3. Fleisig GS, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of overhand throwing with implications for injuries. Sports Med Auckl NZ. 1996;21(6):421-437.

4. Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: Biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(2):265-275.

5. Kaczmarek PK, Lubiatowski P, Cisowski P, et al. Shoulder problems in overhead sports. Part I - biomechanics of throwing. Pol Orthop Traumatol. 2014;79:50-58.

6. Toyoshima S, Hoshikawa T, Miyashita M, Oguri T. Contribution of the body parts to throwing performance. Biomech IV. 1974;5:169-174.

7. Weber AE, Kontaxis A, O’Brien SJ, Bedi A. The biomechanics of throwing: simplified and cogent. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2014;22(2):72-79.

8. Werner SL, Fleisig GS, Dillman CJ, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of the elbow during baseball pitching. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(6):274-278.

9. Chang ES, Greco NJ, McClincy MP, Bradley JP. Posterior shoulder instability in overhead athletes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):179-187.

10. Digiovine NM, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J. An electromyographic analysis of the upper extremity in pitching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(1):15-25.

11. Axe M, Hurd W, Snyder-Mackler L. Data-based interval throwing programs for baseball players. Sports Health. 2009;1(2):145-153.

12. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Reed J, Crenshaw K, Andrews JR. Interval sport programs: guidelines for baseball, tennis, and golf. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(6):293-298.

13. Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR, Lemak LF. Kinematic and kinetic comparison of full and partial effort baseball pitching. Conference proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Biomechanics; 1996:151-152.

14. Fleisig GS, Hsu WK, Fortenbaugh D, Cordover A, Press JM. Trunk axial rotation in baseball pitching and batting. Sports Biomech. 2013;12(4):324-333.

15. Monti R. Return to hitting: an interval hitting progression and overview of hitting mechanics following injury. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(7):1059-1073.

16. Welch CM, Banks SA, Cook FF, Draovitch P. Hitting a baseball: a biomechanical description. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22(5):193-201.

17. Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Konin JG, Strube MJ. Development of a distance-based interval throwing program for Little League-aged athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(5):594-602.

18. Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Proposed practice guidelines for nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation of physically active individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(4):194-203.

19. Hegedus EJ, McDonough S, Bleakley C, Cook CE, Baxter GD. Clinician-friendly lower extremity physical performance measures in athletes: a systematic review of measurement properties and correlation with injury, part 1. The tests for knee function including the hop tests. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(10):642-648.

20. Higuchi T, Nagami T, Morohoshi J, Nakata H, Kanosue K. Disturbance in hitting accuracy by professional and collegiate baseball players due to intentional change of target position. Percept Mot Skills. 2013;116(2):627-639.

1. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402-408.

2. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

3. Fleisig GS, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of overhand throwing with implications for injuries. Sports Med Auckl NZ. 1996;21(6):421-437.

4. Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: Biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(2):265-275.

5. Kaczmarek PK, Lubiatowski P, Cisowski P, et al. Shoulder problems in overhead sports. Part I - biomechanics of throwing. Pol Orthop Traumatol. 2014;79:50-58.

6. Toyoshima S, Hoshikawa T, Miyashita M, Oguri T. Contribution of the body parts to throwing performance. Biomech IV. 1974;5:169-174.

7. Weber AE, Kontaxis A, O’Brien SJ, Bedi A. The biomechanics of throwing: simplified and cogent. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2014;22(2):72-79.

8. Werner SL, Fleisig GS, Dillman CJ, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of the elbow during baseball pitching. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(6):274-278.

9. Chang ES, Greco NJ, McClincy MP, Bradley JP. Posterior shoulder instability in overhead athletes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(1):179-187.

10. Digiovine NM, Jobe FW, Pink M, Perry J. An electromyographic analysis of the upper extremity in pitching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(1):15-25.

11. Axe M, Hurd W, Snyder-Mackler L. Data-based interval throwing programs for baseball players. Sports Health. 2009;1(2):145-153.

12. Reinold MM, Wilk KE, Reed J, Crenshaw K, Andrews JR. Interval sport programs: guidelines for baseball, tennis, and golf. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(6):293-298.

13. Fleisig GS, Zheng N, Barrentine SW, Escamilla RF, Andrews JR, Lemak LF. Kinematic and kinetic comparison of full and partial effort baseball pitching. Conference proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Biomechanics; 1996:151-152.

14. Fleisig GS, Hsu WK, Fortenbaugh D, Cordover A, Press JM. Trunk axial rotation in baseball pitching and batting. Sports Biomech. 2013;12(4):324-333.

15. Monti R. Return to hitting: an interval hitting progression and overview of hitting mechanics following injury. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10(7):1059-1073.

16. Welch CM, Banks SA, Cook FF, Draovitch P. Hitting a baseball: a biomechanical description. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22(5):193-201.

17. Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Konin JG, Strube MJ. Development of a distance-based interval throwing program for Little League-aged athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(5):594-602.

18. Fitzgerald GK, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Proposed practice guidelines for nonoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation of physically active individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30(4):194-203.

19. Hegedus EJ, McDonough S, Bleakley C, Cook CE, Baxter GD. Clinician-friendly lower extremity physical performance measures in athletes: a systematic review of measurement properties and correlation with injury, part 1. The tests for knee function including the hop tests. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(10):642-648.

20. Higuchi T, Nagami T, Morohoshi J, Nakata H, Kanosue K. Disturbance in hitting accuracy by professional and collegiate baseball players due to intentional change of target position. Percept Mot Skills. 2013;116(2):627-639.

Predicting and Preventing Injury in Major League Baseball

Major league baseball (MLB) is one of the most popular sports in the United States, with an average annual viewership of 11 million for the All-Star game and almost 14 million for the World Series.1 MLB has an average annual revenue of almost $10 billion, while the net worth of all 30 MLB teams combined is estimated at $36 billion; an increase of 48% from 1 year ago.2 As the sport continues to grow in popularity and receives more social media coverage, several issues, specifically injuries to its players, have come to the forefront of the news. Injuries to MLB players, specifically pitchers, have become a significant concern in recent years. The active and extended rosters in MLB include 750 and 1200 athletes, respectively, with approximately 360 active spots taken up by pitchers.3 Hence, MLB employs a large number of elite athletes within its organization. It is important to understand not only what injuries are occurring in these athletes, but also how these injuries may be prevented.

Epidemiology

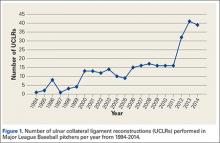

Injuries to MLB players, specifically pitchers, have increased over the past several years.4 Between 2005 and 2008, there was an overall increase of 37% in total number of injuries, with more injuries occurring in pitchers than any other position.5 While position players are more likely to sustain an injury to the lower extremity, pitchers are more likely to sustain an injury to the upper extremity.5 The month with the most injuries to MLB players was April, while the fewest number of injuries occurred in September.5 One injury that has been in the spotlight due to its dramatically increasing incidence is tear of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL). Several studies have shown that the number of pitchers undergoing ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction (UCLR), commonly known as Tommy John surgery, has significantly increased over the past 20 years (Figure 1).4,6 Between 25% to 33% of all MLB pitchers have undergone UCLR.

While the number of primary UCLR in MLB pitchers has become a significant concern, an even more pressing concern is the number of pitchers undergoing revision UCLR, as this number has increased over the past several years.7 Currently, there is some debate as to how to best address the UCL during primary UCLR (graft type, exposure, treatment of the ulnar nerve, and graft fixation methods) because no study has shown one fixation method or graft type to be superior to others. Similarly, no study has definitively proven how to best manage the ulnar nerve (transpose in all patients, only transpose if preoperative symptoms of numbness/tingling, subluxation, etc. exist). Unfortunately, the results following revision UCLR are inferior to those following primary UCLR.4,7,8 Hence, given this information, it is imperative to both determine and implement strategies aimed at minimizing the need for revision.

Risk Factors for Injury

Although MLB has received more media attention than lower levels of baseball competition, there is relatively sparse evidence surrounding injury risk factors among MLB players. The majority of studies performed have evaluated risk factors for injury in younger baseball athletes (adolescent, high school, and college). The number of athletes at these lower levels sustaining injuries has increased over the past several years as well.9 Several large prospective studies have evaluated risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball players. The risk factors include pitching year-round, pitching more than 100 innings per year, high pitch counts, pitching for multiple teams, geography, pitching on consecutive days, pitching while fatigued, breaking pitches, higher elbow valgus torque, pitching with higher velocity, pitching with supraspinatus weakness, and pitching with a glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD).10-17 The large majority of these risk factors are essentially part of a pitcher’s cumulative work, which consists of number of games pitched, total pitches thrown, total innings pitched, innings pitched per game, and pitches thrown per game. One prior study has evaluated cumulative work as a predictor for injury in MLB pitchers.18 While there were several issues with the study methodology, the authors found no correlation between a MLB pitcher’s cumulative work and risk for injury.

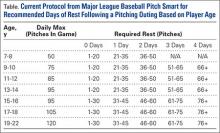

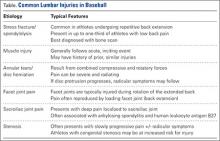

Given our current understanding of repetitive microtrauma as the pathophysiology behind these injuries, it remains unclear why cumulative work would be predictive of injury in youth pitchers but not in MLB pitchers.16 Several potential reasons exist as to why cumulative work may relate to risk of injury in youth pitchers and not MLB pitchers. Achieving MLB status may infer the element of natural selection based on technique and talent that supersedes the effect of “cumulative trauma” in many players. In MLB pitchers, cumulative work is closely monitored. In addition, these players are only playing for a single team and are not pitching competitively year-round, while many youth players play for multiple teams and may pitch year-round. To combat youth injuries, MLB Pitch Smart has developed recommendations on pitch counts and days of rest for pitchers of all age groups (Table).19 While data do not yet exist to clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of these guidelines, given the risk factors previously mentioned, it seems that these recommendations will show some reduction in youth injuries in years to come.

Some studies have evaluated anatomic variation among pitchers as a risk factor for injury. Polster and colleagues20 performed computed tomography (CT) scans with 3-dimensional reconstructions on the humeri of both the throwing and non-throwing arms of 25 MLB pitchers to determine if humeral torsion was related to the incidence and severity of upper extremity injuries in these athletes. The authors defined a severe injury as those which kept the player out for >30 days. Overall, 11 pitchers were injured during the 2-year study period. There was a strong inverse relationship between torsion and injury severity such that lower degrees of dominant humeral torsion correlated with higher injury severity (P = .005). However, neither throwing arm humeral torsion nor the difference in torsion between throwing and non-throwing humeri were predictive of overall injury incidence. While this is a nonmodifiable risk factor, it is important to understand how the pitcher’s anatomy plays a role in risk of injury.20 Understanding nonmodifiable risk factors may be helpful in the future to risk stratify, prognosticate, and modulate modifiable risk factors such as cumulative work.

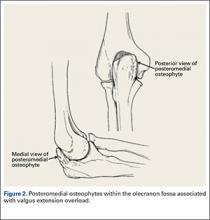

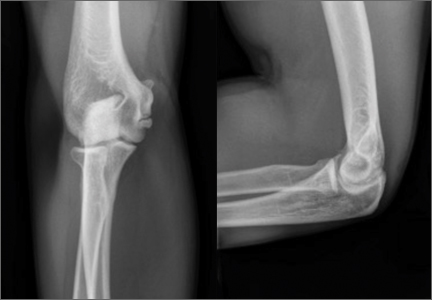

Elbow

Injuries to the elbow have become more common in recent years amongst MLB players, although the literature regarding risk factors for elbow injuries is sparse.4,6 Wilk and colleagues21 performed a prospective study to determine if deficits in glenohumeral passive range of motion (ROM) increased the risk of elbow injury in MLB pitchers. Between 2005-2012, the authors measured passive shoulder ROM of both the throwing and non-throwing shoulder of 296 major and minor league pitchers and followed them for a median of 53.4 months. In total, 38 players suffered 49 elbow injuries and required 8 surgeries, accounting for a total of 2551 days spent on the disabled list (DL). GIRD and external rotation insufficiency were not correlated with elbow injuries. However, pitchers with deficits of >5° in total rotation between the throwing and non-throwing shoulders had a 2.6 times greater risk for injury (P = .007) and pitchers with deficits of ≥5° in flexion of the throwing shoulder compared to the non-throwing shoulder had a 2.8 times greater risk for injury (P = .008).21 Prior studies have demonstrated trends towards increased elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers with an increase in both elbow valgus torque as well as shoulder external rotation torque; maximum pitch velocity was also shown to be an independent risk factor for elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers.10,11 These injuries typically occur during the late cocking/early acceleration phase of the pitching cycle, when the shoulder and elbow experience the most significant force of any point in time during a pitch (Figure 2).17 At our institution, there are several ongoing studies to determine the relative contributions of pitch velocity, number, and type to elbow injury rates. Prospective studies are also ongoing at other institutions.

Shoulder

Shoulder injuries are one of the most common injuries seen in MLB players, specifically pitchers. Similar to the prior study, Wilk and colleagues22 recently performed a prospective study to determine if passive ROM of the glenohumeral joint in MLB pitchers was predictive of shoulder injury or shoulder surgery. As in the previous study, the authors’ measured passive shoulder ROM of the throwing and non-throwing shoulder of 296 major and minor league pitchers during spring training between 2005-2012 and obtained an average follow-up of 48.4 months. The authors found a total of 75 shoulder injuries and 20 surgeries among 51 pitchers (17%) that resulted in 5570 days on the DL. While total rotation deficit, GIRD, and flexion deficit had no relation to shoulder injury or surgery, pitchers with <5° greater external rotation in the throwing shoulder compared to the non-throwing shoulder were more than 2 times more likely to be placed on the DL for a shoulder injury (P = .014) and were 4 times more likely to require shoulder surgery (P = .009).22 The authors concluded that an insufficient side-to-side difference in external rotation of the throwing shoulder increased a pitcher’s likelihood of shoulder injury as well as surgery.

Other

One area that has not received as much attention as repetitive use injuries of the shoulder and elbow is acute collision injuries. Collision injuries include concussions, hyperextension injuries to the knees, shoulder dislocations, fractures of the foot and ankle, and others.23 Catchers and base runners during scoring plays are at a high risk for collision injury. Recent evidence has shown that catchers average approximately 2.75 collision injuries per 1000 athletic exposures (AE), accounting for an average of 39.1 days on the DL per collision injury.23 However, despite these collision injuries, catchers spend more time on the DL from non-collision injuries (specifically shoulder injuries requiring surgical intervention), as studies have shown 19 different non-collision injuries that accounted for >100 days on the DL for catchers compared to no collision injuries that caused a catcher to be on the DL for >100 days.23 The position of catcher is not an independent risk factor for sustaining an injury in MLB players.5

Preventative Measures