User login

Biomarker-based score predicts poor outcomes after acute ischemic stroke

PHILADELPHIA – A prognostic score for acute ischemic stroke that incorporates copeptin levels, age, recanalization, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score has been externally validated and accurately predicts unfavorable outcome, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Although the four-item score could not be validated for mortality prediction, it had reasonable accuracy for predicting unfavorable functional outcome, defined as disability or mortality 3 months after ischemic stroke, Gian Marco De Marchis, MD, of the department of neurology and the stroke center at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), said in a presentation.

“The use of a biomarker increases prognostic accuracy, allowing us to personalize prognosis in the frame of individualized, precision medicine,” Dr. De Marchis said.

Copeptin has been linked to disability and mortality at 3 months in two independent, large cohort studies of patients with ischemic stroke, he said.

The four-item prognostic score devised by Dr. De Marchis and his coinvestigators, which they call the CoRisk score, was developed based on a derivation cohort of 319 acute ischemic stroke patients and a validation cohort including another 783 patients in the Copeptin for Risk Stratification in Acute Stroke Patients (CoRisk) Study.

Diagnostic accuracy was 82% for the endpoint of unfavorable functional outcome at 3 months, according to Dr. De Marchis.

“The observed outcomes matched well with the expected outcomes,” he said in his presentation.

Further analyses demonstrated that the addition of copeptin indeed contributed to the diagnostic accuracy of the score, improving the classification for 46%; in other words, about half of the patients were reclassified based on addition of the biomarker data.

By contrast, the score is not well suited to predict mortality alone at 3 months, the results of the analyses showed.

The algorithm used to calculate the score based on its four variables is somewhat complex, but available as a free app and online calculator, Dr. De Marchis said.

Dr. De Marchis and his coauthors had nothing to disclose related to their study. A full report on the study was published ahead of print on March 1 in Neurology.

SOURCE: De Marchis GM et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S47.001.

PHILADELPHIA – A prognostic score for acute ischemic stroke that incorporates copeptin levels, age, recanalization, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score has been externally validated and accurately predicts unfavorable outcome, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Although the four-item score could not be validated for mortality prediction, it had reasonable accuracy for predicting unfavorable functional outcome, defined as disability or mortality 3 months after ischemic stroke, Gian Marco De Marchis, MD, of the department of neurology and the stroke center at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), said in a presentation.

“The use of a biomarker increases prognostic accuracy, allowing us to personalize prognosis in the frame of individualized, precision medicine,” Dr. De Marchis said.

Copeptin has been linked to disability and mortality at 3 months in two independent, large cohort studies of patients with ischemic stroke, he said.

The four-item prognostic score devised by Dr. De Marchis and his coinvestigators, which they call the CoRisk score, was developed based on a derivation cohort of 319 acute ischemic stroke patients and a validation cohort including another 783 patients in the Copeptin for Risk Stratification in Acute Stroke Patients (CoRisk) Study.

Diagnostic accuracy was 82% for the endpoint of unfavorable functional outcome at 3 months, according to Dr. De Marchis.

“The observed outcomes matched well with the expected outcomes,” he said in his presentation.

Further analyses demonstrated that the addition of copeptin indeed contributed to the diagnostic accuracy of the score, improving the classification for 46%; in other words, about half of the patients were reclassified based on addition of the biomarker data.

By contrast, the score is not well suited to predict mortality alone at 3 months, the results of the analyses showed.

The algorithm used to calculate the score based on its four variables is somewhat complex, but available as a free app and online calculator, Dr. De Marchis said.

Dr. De Marchis and his coauthors had nothing to disclose related to their study. A full report on the study was published ahead of print on March 1 in Neurology.

SOURCE: De Marchis GM et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S47.001.

PHILADELPHIA – A prognostic score for acute ischemic stroke that incorporates copeptin levels, age, recanalization, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score has been externally validated and accurately predicts unfavorable outcome, according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Although the four-item score could not be validated for mortality prediction, it had reasonable accuracy for predicting unfavorable functional outcome, defined as disability or mortality 3 months after ischemic stroke, Gian Marco De Marchis, MD, of the department of neurology and the stroke center at University Hospital Basel (Switzerland), said in a presentation.

“The use of a biomarker increases prognostic accuracy, allowing us to personalize prognosis in the frame of individualized, precision medicine,” Dr. De Marchis said.

Copeptin has been linked to disability and mortality at 3 months in two independent, large cohort studies of patients with ischemic stroke, he said.

The four-item prognostic score devised by Dr. De Marchis and his coinvestigators, which they call the CoRisk score, was developed based on a derivation cohort of 319 acute ischemic stroke patients and a validation cohort including another 783 patients in the Copeptin for Risk Stratification in Acute Stroke Patients (CoRisk) Study.

Diagnostic accuracy was 82% for the endpoint of unfavorable functional outcome at 3 months, according to Dr. De Marchis.

“The observed outcomes matched well with the expected outcomes,” he said in his presentation.

Further analyses demonstrated that the addition of copeptin indeed contributed to the diagnostic accuracy of the score, improving the classification for 46%; in other words, about half of the patients were reclassified based on addition of the biomarker data.

By contrast, the score is not well suited to predict mortality alone at 3 months, the results of the analyses showed.

The algorithm used to calculate the score based on its four variables is somewhat complex, but available as a free app and online calculator, Dr. De Marchis said.

Dr. De Marchis and his coauthors had nothing to disclose related to their study. A full report on the study was published ahead of print on March 1 in Neurology.

SOURCE: De Marchis GM et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S47.001.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2019

Perplexing text messages may be the sole sign of stroke

PHILADELPHIA – described at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The phenomenon, dubbed “dystextia” and characterized by confusing interpersonal electronic communications, is not new but is increasingly relevant to clinical practice now that smartphones are essentially ubiquitous, said the case report authors.

In fact, time to intervention may be positively impacted if access to a patient’s texts and emails can be obtained, said lead author Taylor R. Anderson, a medical student at Wayne State University, Detroit.

The findings sparked interest in further research into the underlying causes and implications of dystextia: “It will be interesting to see if there are specific regions of the brain that are responsible for texting, and how they relate to other forms of communication such as handwriting and typing,” the authors said in their poster presentation.

Mr. Anderson and colleagues described two patients evaluated at Ascension St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit who had stroke presenting as difficulty in typing text messages.

One case was a 43-year-old woman who experienced headache consistent with her usual migraine and spelling errors in her texts and posts on Facebook. She had visuospatial anomalies and left facial droop on evaluation. A brain MRI revealed acute embolic infarcts in the parietal and right frontal lobes, according to Mr. Anderson and coauthors.

The second case was a 66-year-old woman who had difficulty writing texts and typed notes. A head CT done in an urgent care facility showed a left frontal subacute infarct, which, according to the authors, was likely related to risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

These cases show that dystextia can arise after lesions in either hemisphere, the authors said. However, they emphasized that both cases involved the dominant cerebral hemisphere, while by contrast, there have not been previous reports of dystextia due to nondominant hemispheric infarct.

It stands to reason that stroke would affect the ability to text, a multipurpose task that involves use of motor, language, and vision skills, the authors said. Strokes could affect not only skills needed to type, read, and express thoughts, but also visuospatial memory mapping to letters on the device’s keyboard, they noted.

The left frontal and superior parietal regions have been implicated in handwriting in neuroimaging experiments, the authors said, while the operculum and left second frontal convolution are involved in typing.

The authors had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Anderson T et al. AAN 2019. Abstract P5.3-062.

PHILADELPHIA – described at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The phenomenon, dubbed “dystextia” and characterized by confusing interpersonal electronic communications, is not new but is increasingly relevant to clinical practice now that smartphones are essentially ubiquitous, said the case report authors.

In fact, time to intervention may be positively impacted if access to a patient’s texts and emails can be obtained, said lead author Taylor R. Anderson, a medical student at Wayne State University, Detroit.

The findings sparked interest in further research into the underlying causes and implications of dystextia: “It will be interesting to see if there are specific regions of the brain that are responsible for texting, and how they relate to other forms of communication such as handwriting and typing,” the authors said in their poster presentation.

Mr. Anderson and colleagues described two patients evaluated at Ascension St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit who had stroke presenting as difficulty in typing text messages.

One case was a 43-year-old woman who experienced headache consistent with her usual migraine and spelling errors in her texts and posts on Facebook. She had visuospatial anomalies and left facial droop on evaluation. A brain MRI revealed acute embolic infarcts in the parietal and right frontal lobes, according to Mr. Anderson and coauthors.

The second case was a 66-year-old woman who had difficulty writing texts and typed notes. A head CT done in an urgent care facility showed a left frontal subacute infarct, which, according to the authors, was likely related to risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

These cases show that dystextia can arise after lesions in either hemisphere, the authors said. However, they emphasized that both cases involved the dominant cerebral hemisphere, while by contrast, there have not been previous reports of dystextia due to nondominant hemispheric infarct.

It stands to reason that stroke would affect the ability to text, a multipurpose task that involves use of motor, language, and vision skills, the authors said. Strokes could affect not only skills needed to type, read, and express thoughts, but also visuospatial memory mapping to letters on the device’s keyboard, they noted.

The left frontal and superior parietal regions have been implicated in handwriting in neuroimaging experiments, the authors said, while the operculum and left second frontal convolution are involved in typing.

The authors had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Anderson T et al. AAN 2019. Abstract P5.3-062.

PHILADELPHIA – described at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The phenomenon, dubbed “dystextia” and characterized by confusing interpersonal electronic communications, is not new but is increasingly relevant to clinical practice now that smartphones are essentially ubiquitous, said the case report authors.

In fact, time to intervention may be positively impacted if access to a patient’s texts and emails can be obtained, said lead author Taylor R. Anderson, a medical student at Wayne State University, Detroit.

The findings sparked interest in further research into the underlying causes and implications of dystextia: “It will be interesting to see if there are specific regions of the brain that are responsible for texting, and how they relate to other forms of communication such as handwriting and typing,” the authors said in their poster presentation.

Mr. Anderson and colleagues described two patients evaluated at Ascension St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit who had stroke presenting as difficulty in typing text messages.

One case was a 43-year-old woman who experienced headache consistent with her usual migraine and spelling errors in her texts and posts on Facebook. She had visuospatial anomalies and left facial droop on evaluation. A brain MRI revealed acute embolic infarcts in the parietal and right frontal lobes, according to Mr. Anderson and coauthors.

The second case was a 66-year-old woman who had difficulty writing texts and typed notes. A head CT done in an urgent care facility showed a left frontal subacute infarct, which, according to the authors, was likely related to risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

These cases show that dystextia can arise after lesions in either hemisphere, the authors said. However, they emphasized that both cases involved the dominant cerebral hemisphere, while by contrast, there have not been previous reports of dystextia due to nondominant hemispheric infarct.

It stands to reason that stroke would affect the ability to text, a multipurpose task that involves use of motor, language, and vision skills, the authors said. Strokes could affect not only skills needed to type, read, and express thoughts, but also visuospatial memory mapping to letters on the device’s keyboard, they noted.

The left frontal and superior parietal regions have been implicated in handwriting in neuroimaging experiments, the authors said, while the operculum and left second frontal convolution are involved in typing.

The authors had nothing to disclose.

SOURCE: Anderson T et al. AAN 2019. Abstract P5.3-062.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2019

Single-center study outlines stroke risk, DOAC type in nonvalvular AFib patients

PHILADELPHIA – A disproportionate number of breakthrough strokes were observed among patients receiving rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in a stroke unit, according to a small, single-center, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The researchers reviewed all patients presenting to a tertiary care stroke unit in Australia from January 2015 to June 2018.

A total of 56 patients (median age was 74 years; 61% were male) had received direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy and then had an ischemic stroke. Of those patients, 37 (66%) had strokes while receiving the treatment; 14 patients (25%) had a stroke after recently stopping a DOAC, often prior to a medical procedure; and 5 patients (9%) were not adherent to their DOAC regimen.

Of the 37 patients who had strokes during DOAC treatment, 48% were on rivaroxaban, 9% were on dabigatran, and 9% were on apixaban, Fiona Chan, MD, of The Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and coinvestigators reported in a poster presentation.

While these findings need to be replicated in a larger study, they do “raise concern for inadequate stroke prevention within this cohort,” they said.

Moreover, the findings illustrate the importance of bridging anticoagulation prior to procedures, when appropriate, to minimize stroke risk, they added, as 25% of the strokes had occurred in patients who recently stopped the DOACs due to procedures.

To determine which DOAC was most often associated with breakthrough ischemic strokes in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, the investigators compared the proportion of DOACs prescribed in Australia to the proportion of observed strokes in their cohort.

Despite accounting for about 51% of Australian DOAC prescriptions, rivaroxaban represented nearly 73% of breakthrough strokes among the patients who had strokes while receiving the treatment (P = .001), the investigators reported.

Conversely, apixaban accounted for about 35% of prescriptions but 14% of the breakthrough strokes (P = .0007), while dabigatran accounted for 14% of prescriptions and 14% of the strokes (P = 0.99), the investigators said in their poster.

One limitation of this retrospective study is that the patient cohort came from a single specialized center, and may not reflect the true incidence of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation across Australia, the researchers noted.

Dr. Chan and coinvestigators reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chan F et al. AAN 2019. P1.3-001.

PHILADELPHIA – A disproportionate number of breakthrough strokes were observed among patients receiving rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in a stroke unit, according to a small, single-center, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The researchers reviewed all patients presenting to a tertiary care stroke unit in Australia from January 2015 to June 2018.

A total of 56 patients (median age was 74 years; 61% were male) had received direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy and then had an ischemic stroke. Of those patients, 37 (66%) had strokes while receiving the treatment; 14 patients (25%) had a stroke after recently stopping a DOAC, often prior to a medical procedure; and 5 patients (9%) were not adherent to their DOAC regimen.

Of the 37 patients who had strokes during DOAC treatment, 48% were on rivaroxaban, 9% were on dabigatran, and 9% were on apixaban, Fiona Chan, MD, of The Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and coinvestigators reported in a poster presentation.

While these findings need to be replicated in a larger study, they do “raise concern for inadequate stroke prevention within this cohort,” they said.

Moreover, the findings illustrate the importance of bridging anticoagulation prior to procedures, when appropriate, to minimize stroke risk, they added, as 25% of the strokes had occurred in patients who recently stopped the DOACs due to procedures.

To determine which DOAC was most often associated with breakthrough ischemic strokes in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, the investigators compared the proportion of DOACs prescribed in Australia to the proportion of observed strokes in their cohort.

Despite accounting for about 51% of Australian DOAC prescriptions, rivaroxaban represented nearly 73% of breakthrough strokes among the patients who had strokes while receiving the treatment (P = .001), the investigators reported.

Conversely, apixaban accounted for about 35% of prescriptions but 14% of the breakthrough strokes (P = .0007), while dabigatran accounted for 14% of prescriptions and 14% of the strokes (P = 0.99), the investigators said in their poster.

One limitation of this retrospective study is that the patient cohort came from a single specialized center, and may not reflect the true incidence of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation across Australia, the researchers noted.

Dr. Chan and coinvestigators reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chan F et al. AAN 2019. P1.3-001.

PHILADELPHIA – A disproportionate number of breakthrough strokes were observed among patients receiving rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in a stroke unit, according to a small, single-center, retrospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The researchers reviewed all patients presenting to a tertiary care stroke unit in Australia from January 2015 to June 2018.

A total of 56 patients (median age was 74 years; 61% were male) had received direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) therapy and then had an ischemic stroke. Of those patients, 37 (66%) had strokes while receiving the treatment; 14 patients (25%) had a stroke after recently stopping a DOAC, often prior to a medical procedure; and 5 patients (9%) were not adherent to their DOAC regimen.

Of the 37 patients who had strokes during DOAC treatment, 48% were on rivaroxaban, 9% were on dabigatran, and 9% were on apixaban, Fiona Chan, MD, of The Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and coinvestigators reported in a poster presentation.

While these findings need to be replicated in a larger study, they do “raise concern for inadequate stroke prevention within this cohort,” they said.

Moreover, the findings illustrate the importance of bridging anticoagulation prior to procedures, when appropriate, to minimize stroke risk, they added, as 25% of the strokes had occurred in patients who recently stopped the DOACs due to procedures.

To determine which DOAC was most often associated with breakthrough ischemic strokes in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, the investigators compared the proportion of DOACs prescribed in Australia to the proportion of observed strokes in their cohort.

Despite accounting for about 51% of Australian DOAC prescriptions, rivaroxaban represented nearly 73% of breakthrough strokes among the patients who had strokes while receiving the treatment (P = .001), the investigators reported.

Conversely, apixaban accounted for about 35% of prescriptions but 14% of the breakthrough strokes (P = .0007), while dabigatran accounted for 14% of prescriptions and 14% of the strokes (P = 0.99), the investigators said in their poster.

One limitation of this retrospective study is that the patient cohort came from a single specialized center, and may not reflect the true incidence of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation across Australia, the researchers noted.

Dr. Chan and coinvestigators reported that they had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Chan F et al. AAN 2019. P1.3-001.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2019

Key clinical point: Rivaroxaban was associated with a disproportionate number of breakthrough strokes among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with direct oral anticoagulants at one stroke unit in Australia.

Major finding: Despite accounting for about 51% of Australian DOAC prescriptions, rivaroxaban represented nearly 73% of breakthrough strokes among the patients who had strokes while receiving treatment (P = .001).

Study details: Retrospective study of 56 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation reporting to a tertiary care stroke unit in Australia.

Disclosures: The authors reported no financial disclosures.

Source: Chan F et al. AAN 019. Poster P1.3-001.

Depressive symptoms are associated with stroke risk

PHILADELPHIA – according to preliminary data from a prospective cohort study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Prior research has found that depression may increase the likelihood of hypertension, cardiac morbidity and mortality, and stroke mortality. How depression affects the risk of incident stroke, however, “is underexplored, especially among Latinos and African Americans,” said study author Marialaura Simonetto, MD, of the University of Miami and associates.

To assess the relationship between depressive symptoms and risk of incident ischemic stroke, the researchers analyzed data from more than 1,100 participants in the MRI substudy of the Northern Manhattan Study. The cohort includes older adults who were clinically stroke free at baseline.

Researchers assessed depressive symptoms at baseline using the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D). Scores range from 0-60, and they considered CES-D scores of 16 or greater to be elevated.

The investigators used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios of incident ischemic stroke after adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, years of education, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, diabetes, and hypertension.

In all, 1,104 participants were included in the analysis. Participants had an average age of 70 years, 61% were women, and 69% were Hispanic. At baseline, 198 participants (18%) had elevated depressive symptoms.

During 14 years of follow-up, 101 participants had incident strokes, 87 of which were ischemic strokes. In adjusted models, participants with elevated depressive symptoms had a significantly greater risk of ischemic stroke (HR, 1.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.88). “Every 5-point increase in CES-D score conferred a 12% greater risk of ischemic stroke,” the researchers reported.

“Depression is common and often goes untreated,” Dr. Simonetto said in a news release. “If people with depression are at elevated risk of stroke, early detection and treatment will be even more important.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Simonetto reported no disclosures. Coauthors disclosed personal compensation and research support from pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

SOURCE: Simonetto M et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S1.003.

PHILADELPHIA – according to preliminary data from a prospective cohort study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Prior research has found that depression may increase the likelihood of hypertension, cardiac morbidity and mortality, and stroke mortality. How depression affects the risk of incident stroke, however, “is underexplored, especially among Latinos and African Americans,” said study author Marialaura Simonetto, MD, of the University of Miami and associates.

To assess the relationship between depressive symptoms and risk of incident ischemic stroke, the researchers analyzed data from more than 1,100 participants in the MRI substudy of the Northern Manhattan Study. The cohort includes older adults who were clinically stroke free at baseline.

Researchers assessed depressive symptoms at baseline using the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D). Scores range from 0-60, and they considered CES-D scores of 16 or greater to be elevated.

The investigators used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios of incident ischemic stroke after adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, years of education, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, diabetes, and hypertension.

In all, 1,104 participants were included in the analysis. Participants had an average age of 70 years, 61% were women, and 69% were Hispanic. At baseline, 198 participants (18%) had elevated depressive symptoms.

During 14 years of follow-up, 101 participants had incident strokes, 87 of which were ischemic strokes. In adjusted models, participants with elevated depressive symptoms had a significantly greater risk of ischemic stroke (HR, 1.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.88). “Every 5-point increase in CES-D score conferred a 12% greater risk of ischemic stroke,” the researchers reported.

“Depression is common and often goes untreated,” Dr. Simonetto said in a news release. “If people with depression are at elevated risk of stroke, early detection and treatment will be even more important.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Simonetto reported no disclosures. Coauthors disclosed personal compensation and research support from pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

SOURCE: Simonetto M et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S1.003.

PHILADELPHIA – according to preliminary data from a prospective cohort study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Prior research has found that depression may increase the likelihood of hypertension, cardiac morbidity and mortality, and stroke mortality. How depression affects the risk of incident stroke, however, “is underexplored, especially among Latinos and African Americans,” said study author Marialaura Simonetto, MD, of the University of Miami and associates.

To assess the relationship between depressive symptoms and risk of incident ischemic stroke, the researchers analyzed data from more than 1,100 participants in the MRI substudy of the Northern Manhattan Study. The cohort includes older adults who were clinically stroke free at baseline.

Researchers assessed depressive symptoms at baseline using the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D). Scores range from 0-60, and they considered CES-D scores of 16 or greater to be elevated.

The investigators used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios of incident ischemic stroke after adjusting for age, sex, race, ethnicity, years of education, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, diabetes, and hypertension.

In all, 1,104 participants were included in the analysis. Participants had an average age of 70 years, 61% were women, and 69% were Hispanic. At baseline, 198 participants (18%) had elevated depressive symptoms.

During 14 years of follow-up, 101 participants had incident strokes, 87 of which were ischemic strokes. In adjusted models, participants with elevated depressive symptoms had a significantly greater risk of ischemic stroke (HR, 1.75; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-2.88). “Every 5-point increase in CES-D score conferred a 12% greater risk of ischemic stroke,” the researchers reported.

“Depression is common and often goes untreated,” Dr. Simonetto said in a news release. “If people with depression are at elevated risk of stroke, early detection and treatment will be even more important.”

The study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Simonetto reported no disclosures. Coauthors disclosed personal compensation and research support from pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

SOURCE: Simonetto M et al. AAN 2019, Abstract S1.003.

REPORTING FROM AAN 2019

Poststroke hemorrhage risk higher with clopidogrel/aspirin than aspirin

A secondary analysis of the POINT randomized, clinical trial found that the risk of major hemorrhage associated with clopidogrel plus aspirin was higher than that with placebo plus aspirin (0.9% vs. 0.2%; hazard ratio, 3.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.44-8.85; P = .003). The study, which was published in JAMA Neurology, randomized nearly 4,900 patients at centers worldwide and concluded that overall the risk for hemorrhage was low with either treatment, although it did also find higher risk of minor hemorrhage with the combination than aspirin alone.

We previously covered results from POINT when they were presented at the World Stroke Congress, which can be found below.

SOURCE: Tillman H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 29. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0932.

A secondary analysis of the POINT randomized, clinical trial found that the risk of major hemorrhage associated with clopidogrel plus aspirin was higher than that with placebo plus aspirin (0.9% vs. 0.2%; hazard ratio, 3.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.44-8.85; P = .003). The study, which was published in JAMA Neurology, randomized nearly 4,900 patients at centers worldwide and concluded that overall the risk for hemorrhage was low with either treatment, although it did also find higher risk of minor hemorrhage with the combination than aspirin alone.

We previously covered results from POINT when they were presented at the World Stroke Congress, which can be found below.

SOURCE: Tillman H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 29. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0932.

A secondary analysis of the POINT randomized, clinical trial found that the risk of major hemorrhage associated with clopidogrel plus aspirin was higher than that with placebo plus aspirin (0.9% vs. 0.2%; hazard ratio, 3.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.44-8.85; P = .003). The study, which was published in JAMA Neurology, randomized nearly 4,900 patients at centers worldwide and concluded that overall the risk for hemorrhage was low with either treatment, although it did also find higher risk of minor hemorrhage with the combination than aspirin alone.

We previously covered results from POINT when they were presented at the World Stroke Congress, which can be found below.

SOURCE: Tillman H et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 29. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0932.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Long-term antibiotic use may heighten stroke, CHD risk

, according to a study in the European Heart Journal.

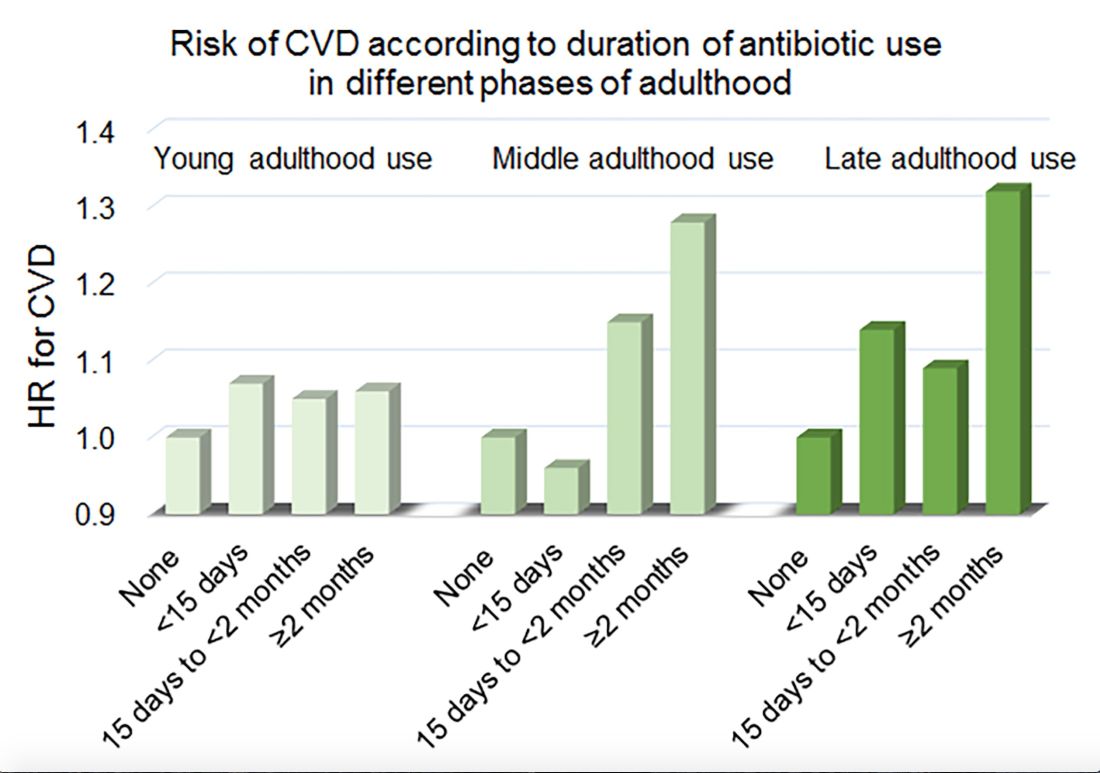

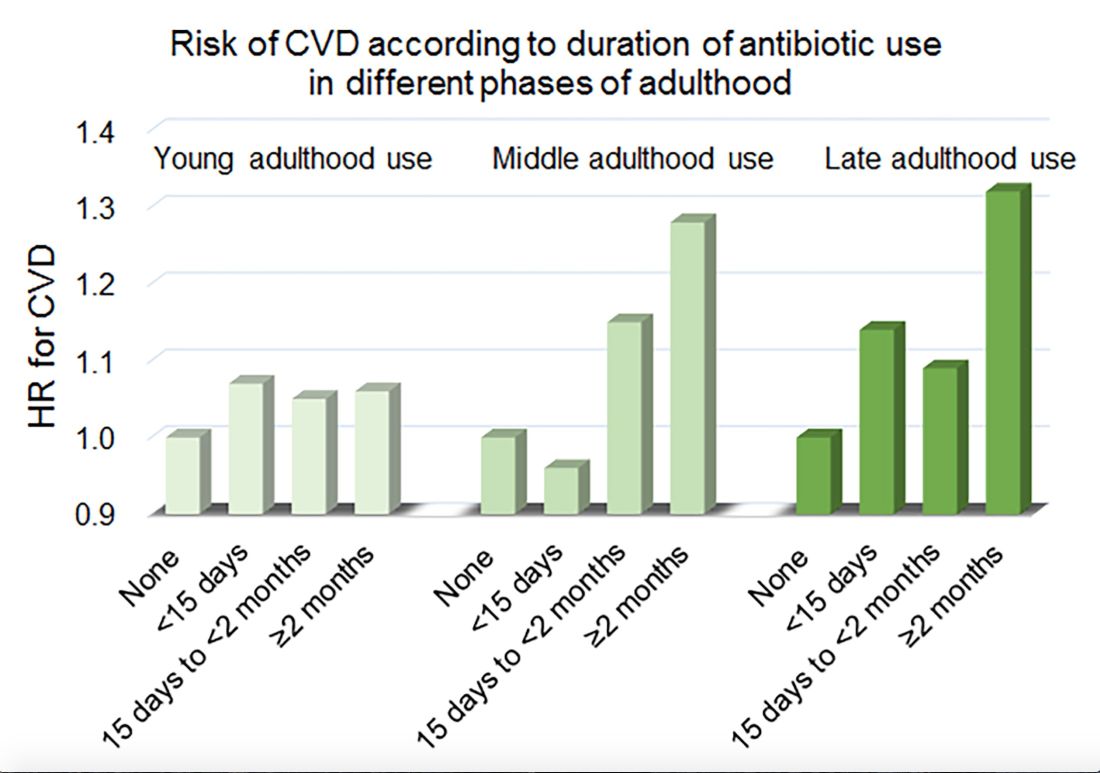

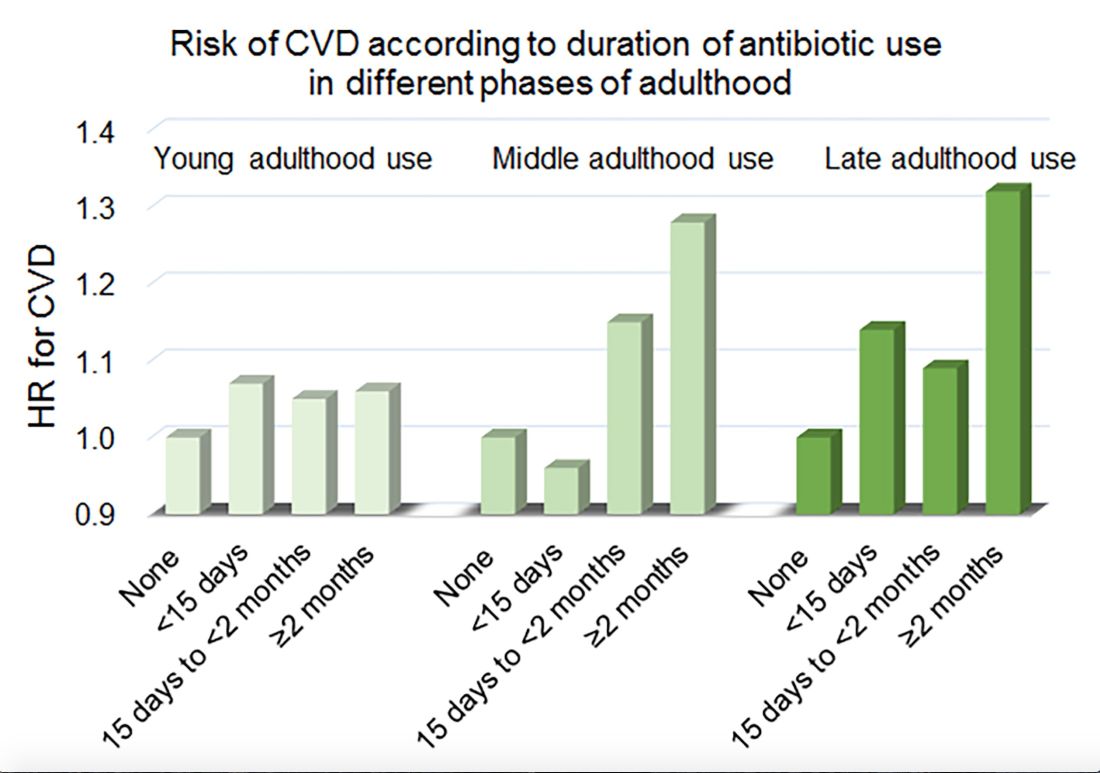

Women in the Nurses’ Health Study who used antibiotics for 2 or more months between ages 40 and 59 years or at age 60 years and older had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with those who did not use antibiotics. Antibiotic use between 20 and 39 years old was not significantly related to cardiovascular disease.

Prior research has found that antibiotics may have long-lasting effects on gut microbiota and relate to cardiovascular disease risk.

“Antibiotic use is the most critical factor in altering the balance of microorganisms in the gut,” said lead investigator Lu Qi, MD, PhD, in a news release. “Previous studies have shown a link between alterations in the microbiotic environment of the gut and inflammation and narrowing of the blood vessels, stroke, and heart disease,” said Dr. Qi, who is the director of the Tulane University Obesity Research Center in New Orleans and an adjunct professor of nutrition at Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

To evaluate associations between life stage, antibiotic exposure, and subsequent cardiovascular disease, researchers analyzed data from 36,429 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were at least 60 years old and had no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer when they completed a 2004 questionnaire about antibiotic usage during young, middle, and late adulthood. The questionnaire asked participants to indicate the total time using antibiotics with eight categories ranging from none to 5 or more years.

The researchers defined incident cardiovascular disease as a composite endpoint of coronary heart disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease) and stroke (nonfatal or fatal). They calculated person-years of follow-up from the questionnaire return date until date of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, death, or end of follow-up in 2012.

Women with longer duration of antibiotic use were more likely to use other medications and have unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles, including family history of myocardial infarction and higher body mass index. Antibiotics most often were used to treat respiratory infections. During an average follow-up of 7.6 years, 1,056 participants developed cardiovascular disease.

In a multivariable model that adjusted for demographics, diet, lifestyle, reason for antibiotic use, medications, overweight status, and other factors, long-term antibiotic use – 2 months or more – in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Although antibiotic use was self-reported, which could lead to misclassification, the participants were health professionals, which may mitigate this limitation, the authors noted. Whether these findings apply to men and other populations requires further study, they said.

Because of the study’s observational design, the results “cannot show that antibiotics cause heart disease and stroke, only that there is a link between them,” Dr. Qi said. “It’s possible that women who reported more antibiotic use might be sicker in other ways that we were unable to measure, or there may be other factors that could affect the results that we have not been able take account of.”

“Our study suggests that antibiotics should be used only when they are absolutely needed,” he concluded. “Considering the potentially cumulative adverse effects, the shorter time of antibiotic use the better.”

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

, according to a study in the European Heart Journal.

Women in the Nurses’ Health Study who used antibiotics for 2 or more months between ages 40 and 59 years or at age 60 years and older had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with those who did not use antibiotics. Antibiotic use between 20 and 39 years old was not significantly related to cardiovascular disease.

Prior research has found that antibiotics may have long-lasting effects on gut microbiota and relate to cardiovascular disease risk.

“Antibiotic use is the most critical factor in altering the balance of microorganisms in the gut,” said lead investigator Lu Qi, MD, PhD, in a news release. “Previous studies have shown a link between alterations in the microbiotic environment of the gut and inflammation and narrowing of the blood vessels, stroke, and heart disease,” said Dr. Qi, who is the director of the Tulane University Obesity Research Center in New Orleans and an adjunct professor of nutrition at Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

To evaluate associations between life stage, antibiotic exposure, and subsequent cardiovascular disease, researchers analyzed data from 36,429 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were at least 60 years old and had no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer when they completed a 2004 questionnaire about antibiotic usage during young, middle, and late adulthood. The questionnaire asked participants to indicate the total time using antibiotics with eight categories ranging from none to 5 or more years.

The researchers defined incident cardiovascular disease as a composite endpoint of coronary heart disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease) and stroke (nonfatal or fatal). They calculated person-years of follow-up from the questionnaire return date until date of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, death, or end of follow-up in 2012.

Women with longer duration of antibiotic use were more likely to use other medications and have unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles, including family history of myocardial infarction and higher body mass index. Antibiotics most often were used to treat respiratory infections. During an average follow-up of 7.6 years, 1,056 participants developed cardiovascular disease.

In a multivariable model that adjusted for demographics, diet, lifestyle, reason for antibiotic use, medications, overweight status, and other factors, long-term antibiotic use – 2 months or more – in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Although antibiotic use was self-reported, which could lead to misclassification, the participants were health professionals, which may mitigate this limitation, the authors noted. Whether these findings apply to men and other populations requires further study, they said.

Because of the study’s observational design, the results “cannot show that antibiotics cause heart disease and stroke, only that there is a link between them,” Dr. Qi said. “It’s possible that women who reported more antibiotic use might be sicker in other ways that we were unable to measure, or there may be other factors that could affect the results that we have not been able take account of.”

“Our study suggests that antibiotics should be used only when they are absolutely needed,” he concluded. “Considering the potentially cumulative adverse effects, the shorter time of antibiotic use the better.”

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

, according to a study in the European Heart Journal.

Women in the Nurses’ Health Study who used antibiotics for 2 or more months between ages 40 and 59 years or at age 60 years and older had a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease, compared with those who did not use antibiotics. Antibiotic use between 20 and 39 years old was not significantly related to cardiovascular disease.

Prior research has found that antibiotics may have long-lasting effects on gut microbiota and relate to cardiovascular disease risk.

“Antibiotic use is the most critical factor in altering the balance of microorganisms in the gut,” said lead investigator Lu Qi, MD, PhD, in a news release. “Previous studies have shown a link between alterations in the microbiotic environment of the gut and inflammation and narrowing of the blood vessels, stroke, and heart disease,” said Dr. Qi, who is the director of the Tulane University Obesity Research Center in New Orleans and an adjunct professor of nutrition at Harvard T.C. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

To evaluate associations between life stage, antibiotic exposure, and subsequent cardiovascular disease, researchers analyzed data from 36,429 participants in the Nurses’ Health Study. The women were at least 60 years old and had no history of cardiovascular disease or cancer when they completed a 2004 questionnaire about antibiotic usage during young, middle, and late adulthood. The questionnaire asked participants to indicate the total time using antibiotics with eight categories ranging from none to 5 or more years.

The researchers defined incident cardiovascular disease as a composite endpoint of coronary heart disease (nonfatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease) and stroke (nonfatal or fatal). They calculated person-years of follow-up from the questionnaire return date until date of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, death, or end of follow-up in 2012.

Women with longer duration of antibiotic use were more likely to use other medications and have unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles, including family history of myocardial infarction and higher body mass index. Antibiotics most often were used to treat respiratory infections. During an average follow-up of 7.6 years, 1,056 participants developed cardiovascular disease.

In a multivariable model that adjusted for demographics, diet, lifestyle, reason for antibiotic use, medications, overweight status, and other factors, long-term antibiotic use – 2 months or more – in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Although antibiotic use was self-reported, which could lead to misclassification, the participants were health professionals, which may mitigate this limitation, the authors noted. Whether these findings apply to men and other populations requires further study, they said.

Because of the study’s observational design, the results “cannot show that antibiotics cause heart disease and stroke, only that there is a link between them,” Dr. Qi said. “It’s possible that women who reported more antibiotic use might be sicker in other ways that we were unable to measure, or there may be other factors that could affect the results that we have not been able take account of.”

“Our study suggests that antibiotics should be used only when they are absolutely needed,” he concluded. “Considering the potentially cumulative adverse effects, the shorter time of antibiotic use the better.”

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

FROM THE EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

Key clinical point: Among middle-aged and older women, 2 or more months’ exposure to antibiotics is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease or stroke.

Major finding: Long-term antibiotic use in late adulthood was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease (hazard ratio, 1.32), as was long-term antibiotic use in middle adulthood (HR, 1.28).

Study details: An analysis of data from nearly 36,500 women in the Nurses’ Health Study.

Disclosures: The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants, the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center, and the United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation. One author received support from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The authors had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Heianza Y et al. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz231.

Does BMI affect outcomes after ischemic stroke?

according to research that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“One possible explanation is that people who are overweight or obese may have a nutritional reserve that may help them survive during prolonged illness,” said Zuolu Liu, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, in a press release. “More research is needed to investigate the relationship between BMI and stroke.”

The obesity paradox was first noted when studies suggested that being overweight improved survival in patients with kidney disease or heart disease. Investigators previously examined whether the obesity paradox is observed in stroke, but their studies were underpowered and produced ambiguous results.

Dr. Liu and colleagues sought to evaluate the relationship between BMI and 90-day outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. They examined data for all participants in the FAST-MAG trial, which studied whether prehospital treatment with magnesium improved disability outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. Dr. Liu and colleagues focused on the outcomes of death, disability or death (that is, modified Rankin Scale score of 2-6), and low stroke-related quality of life (that is, Stroke Impact Scale score less than 70). They analyzed potential relationships with BMI univariately and in multivariate models that adjusted for 12 prognostic variables, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking.

Dr. Liu’s group included 1,033 participants in its study. The population’s mean age was 71 years, and 45.1% of the population was female. Mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 10.6, and mean BMI was 27.5 kg/m2.

The investigators found an inverse association between the risk of death and BMI. Adjusted odds ratios for mortality were 1.67 for underweight participants, 0.85 for overweight participants, 0.54 for obese participants, and 0.38 for severely obese participants, compared with participants of normal weight. Similarly, the risk of disability had a U-shaped relationship with BMI. Odds ratios for disability or death were 1.19 for underweight participants, 0.78 for overweight participants, 0.72 for obese participants, and 0.96 for severely obese participants, compared with participants of normal weight. This relationship was attenuated after adjustment for other prognostic factors, however. Dr. Liu’s group did not find a significant association between BMI and low stroke-related quality of life.

The study was limited by the fact that all participants were from Southern California, which potentially reduced the generalizability of the results. The racial and ethnic composition of the study population, however, is similar to that of the national population, said the researchers.

No study sponsor was reported.

SOURCE: Liu Z et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.3-01.

according to research that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“One possible explanation is that people who are overweight or obese may have a nutritional reserve that may help them survive during prolonged illness,” said Zuolu Liu, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, in a press release. “More research is needed to investigate the relationship between BMI and stroke.”

The obesity paradox was first noted when studies suggested that being overweight improved survival in patients with kidney disease or heart disease. Investigators previously examined whether the obesity paradox is observed in stroke, but their studies were underpowered and produced ambiguous results.

Dr. Liu and colleagues sought to evaluate the relationship between BMI and 90-day outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. They examined data for all participants in the FAST-MAG trial, which studied whether prehospital treatment with magnesium improved disability outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. Dr. Liu and colleagues focused on the outcomes of death, disability or death (that is, modified Rankin Scale score of 2-6), and low stroke-related quality of life (that is, Stroke Impact Scale score less than 70). They analyzed potential relationships with BMI univariately and in multivariate models that adjusted for 12 prognostic variables, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking.

Dr. Liu’s group included 1,033 participants in its study. The population’s mean age was 71 years, and 45.1% of the population was female. Mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 10.6, and mean BMI was 27.5 kg/m2.

The investigators found an inverse association between the risk of death and BMI. Adjusted odds ratios for mortality were 1.67 for underweight participants, 0.85 for overweight participants, 0.54 for obese participants, and 0.38 for severely obese participants, compared with participants of normal weight. Similarly, the risk of disability had a U-shaped relationship with BMI. Odds ratios for disability or death were 1.19 for underweight participants, 0.78 for overweight participants, 0.72 for obese participants, and 0.96 for severely obese participants, compared with participants of normal weight. This relationship was attenuated after adjustment for other prognostic factors, however. Dr. Liu’s group did not find a significant association between BMI and low stroke-related quality of life.

The study was limited by the fact that all participants were from Southern California, which potentially reduced the generalizability of the results. The racial and ethnic composition of the study population, however, is similar to that of the national population, said the researchers.

No study sponsor was reported.

SOURCE: Liu Z et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.3-01.

according to research that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

“One possible explanation is that people who are overweight or obese may have a nutritional reserve that may help them survive during prolonged illness,” said Zuolu Liu, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, in a press release. “More research is needed to investigate the relationship between BMI and stroke.”

The obesity paradox was first noted when studies suggested that being overweight improved survival in patients with kidney disease or heart disease. Investigators previously examined whether the obesity paradox is observed in stroke, but their studies were underpowered and produced ambiguous results.

Dr. Liu and colleagues sought to evaluate the relationship between BMI and 90-day outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. They examined data for all participants in the FAST-MAG trial, which studied whether prehospital treatment with magnesium improved disability outcomes of acute ischemic stroke. Dr. Liu and colleagues focused on the outcomes of death, disability or death (that is, modified Rankin Scale score of 2-6), and low stroke-related quality of life (that is, Stroke Impact Scale score less than 70). They analyzed potential relationships with BMI univariately and in multivariate models that adjusted for 12 prognostic variables, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking.

Dr. Liu’s group included 1,033 participants in its study. The population’s mean age was 71 years, and 45.1% of the population was female. Mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was 10.6, and mean BMI was 27.5 kg/m2.

The investigators found an inverse association between the risk of death and BMI. Adjusted odds ratios for mortality were 1.67 for underweight participants, 0.85 for overweight participants, 0.54 for obese participants, and 0.38 for severely obese participants, compared with participants of normal weight. Similarly, the risk of disability had a U-shaped relationship with BMI. Odds ratios for disability or death were 1.19 for underweight participants, 0.78 for overweight participants, 0.72 for obese participants, and 0.96 for severely obese participants, compared with participants of normal weight. This relationship was attenuated after adjustment for other prognostic factors, however. Dr. Liu’s group did not find a significant association between BMI and low stroke-related quality of life.

The study was limited by the fact that all participants were from Southern California, which potentially reduced the generalizability of the results. The racial and ethnic composition of the study population, however, is similar to that of the national population, said the researchers.

No study sponsor was reported.

SOURCE: Liu Z et al. AAN 2019, Abstract P3.3-01.

FROM AAN 2019

Few stroke patients undergo osteoporosis screening, treatment

Although stroke is a risk factor for osteoporosis, falls, and fractures, very few people who have experienced a recent stroke are either screened for osteoporosis or treated, research suggests.

Writing in Stroke, researchers presented an analysis of Ontario registry data from 16,581 patients who were aged 65 years or older and presented with stroke between 2003 and 2013.

Overall, just 5.1% of patients underwent bone mineral density testing. Of the 1,577 patients who had experienced a prior fracture, 71 (4.7%) had bone mineral density testing, and only 2.9% of those who had not had prior bone mineral density testing were tested after their stroke. Bone mineral density testing was more likely in patients who were younger, who were female, and who experienced a low-trauma fracture in the year after their stroke.

In total, 15.5% of patients were prescribed osteoporosis drugs in the first year after their stroke. However, only 7.8% of those who had fractures before the stroke and 14.8% of those with fractures after the stroke received osteoporosis treatment after the stroke. Patients who were female, had prior osteoporosis, had experienced prior fracture, had previously undergone bone mineral density testing, or had experienced a fracture or fall after their stroke were more likely to receive osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.

The authors found that the neither the severity of stroke nor the presence of other comorbidities was associated with an increased likelihood of screening or treatment of osteoporosis after the stroke.

Stroke is associated with up to a fourfold increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, compared with healthy controls, most probably because of reduced mobility and an increased risk of falls, wrote Eshita Kapoor of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and her coauthors.

“Screening and treatment may be particularly low poststroke because of under-recognition of osteoporosis as a consequence of stroke, a selective focus on the management of cardiovascular risk and stroke recovery, or factors such as dysphagia precluding use of oral bisphosphonates,” the authors wrote.

While the association is noted in U.S. stroke guidelines, there are few recommendations for treatment aside from fall prevention strategies, which the authors noted was a missed opportunity for prevention.

“Use of a risk prediction score to identify those at particularly high short-term risk of fractures after stroke may help to prioritize patients for osteoporosis testing and treatment,” they suggested.

The study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and was supported by ICES (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. One author declared consultancies for the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Kapoor E et al. Stroke. 2019 April 25. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024685

Although stroke is a risk factor for osteoporosis, falls, and fractures, very few people who have experienced a recent stroke are either screened for osteoporosis or treated, research suggests.

Writing in Stroke, researchers presented an analysis of Ontario registry data from 16,581 patients who were aged 65 years or older and presented with stroke between 2003 and 2013.

Overall, just 5.1% of patients underwent bone mineral density testing. Of the 1,577 patients who had experienced a prior fracture, 71 (4.7%) had bone mineral density testing, and only 2.9% of those who had not had prior bone mineral density testing were tested after their stroke. Bone mineral density testing was more likely in patients who were younger, who were female, and who experienced a low-trauma fracture in the year after their stroke.

In total, 15.5% of patients were prescribed osteoporosis drugs in the first year after their stroke. However, only 7.8% of those who had fractures before the stroke and 14.8% of those with fractures after the stroke received osteoporosis treatment after the stroke. Patients who were female, had prior osteoporosis, had experienced prior fracture, had previously undergone bone mineral density testing, or had experienced a fracture or fall after their stroke were more likely to receive osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.

The authors found that the neither the severity of stroke nor the presence of other comorbidities was associated with an increased likelihood of screening or treatment of osteoporosis after the stroke.

Stroke is associated with up to a fourfold increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, compared with healthy controls, most probably because of reduced mobility and an increased risk of falls, wrote Eshita Kapoor of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and her coauthors.

“Screening and treatment may be particularly low poststroke because of under-recognition of osteoporosis as a consequence of stroke, a selective focus on the management of cardiovascular risk and stroke recovery, or factors such as dysphagia precluding use of oral bisphosphonates,” the authors wrote.

While the association is noted in U.S. stroke guidelines, there are few recommendations for treatment aside from fall prevention strategies, which the authors noted was a missed opportunity for prevention.

“Use of a risk prediction score to identify those at particularly high short-term risk of fractures after stroke may help to prioritize patients for osteoporosis testing and treatment,” they suggested.

The study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and was supported by ICES (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. One author declared consultancies for the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Kapoor E et al. Stroke. 2019 April 25. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024685

Although stroke is a risk factor for osteoporosis, falls, and fractures, very few people who have experienced a recent stroke are either screened for osteoporosis or treated, research suggests.

Writing in Stroke, researchers presented an analysis of Ontario registry data from 16,581 patients who were aged 65 years or older and presented with stroke between 2003 and 2013.

Overall, just 5.1% of patients underwent bone mineral density testing. Of the 1,577 patients who had experienced a prior fracture, 71 (4.7%) had bone mineral density testing, and only 2.9% of those who had not had prior bone mineral density testing were tested after their stroke. Bone mineral density testing was more likely in patients who were younger, who were female, and who experienced a low-trauma fracture in the year after their stroke.

In total, 15.5% of patients were prescribed osteoporosis drugs in the first year after their stroke. However, only 7.8% of those who had fractures before the stroke and 14.8% of those with fractures after the stroke received osteoporosis treatment after the stroke. Patients who were female, had prior osteoporosis, had experienced prior fracture, had previously undergone bone mineral density testing, or had experienced a fracture or fall after their stroke were more likely to receive osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.

The authors found that the neither the severity of stroke nor the presence of other comorbidities was associated with an increased likelihood of screening or treatment of osteoporosis after the stroke.

Stroke is associated with up to a fourfold increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, compared with healthy controls, most probably because of reduced mobility and an increased risk of falls, wrote Eshita Kapoor of the department of medicine at the University of Toronto and her coauthors.

“Screening and treatment may be particularly low poststroke because of under-recognition of osteoporosis as a consequence of stroke, a selective focus on the management of cardiovascular risk and stroke recovery, or factors such as dysphagia precluding use of oral bisphosphonates,” the authors wrote.

While the association is noted in U.S. stroke guidelines, there are few recommendations for treatment aside from fall prevention strategies, which the authors noted was a missed opportunity for prevention.

“Use of a risk prediction score to identify those at particularly high short-term risk of fractures after stroke may help to prioritize patients for osteoporosis testing and treatment,” they suggested.

The study was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and was supported by ICES (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. One author declared consultancies for the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Kapoor E et al. Stroke. 2019 April 25. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.024685

FROM STROKE

Low LDL cholesterol may increase women’s risk of hemorrhagic stroke

, according to research published in Neurology.

“Women with very low LDL cholesterol or low triglycerides should be monitored by their doctors for other stroke risk factors that can be modified, like high blood pressure and smoking, in order to reduce their risk of hemorrhagic stroke,” said Pamela M. Rist, ScD, instructor in epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Additional research is needed to determine how to lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women with very low LDL and low triglycerides.”

Several meta-analyses have indicated that LDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Because lipid-lowering treatments are used to prevent cardiovascular disease, this potential association has implications for clinical practice. Most of the studies included in these meta-analyses had low numbers of events among women, which prevented researchers from stratifying their results by sex. Because women are at greater risk of stroke than men, Dr. Rist and her colleagues sought to evaluate the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

An analysis of the Women’s Health Study

The investigators examined data from the Women’s Health Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among female American health professionals aged 45 years or older. The study ended in March 2004, but follow-up is ongoing. At regular intervals, the women complete a questionnaire about disease outcomes, including stroke. Some participants agreed to provide a fasting venous blood sample before randomization. With the subjects’ permission, a committee of physicians examined medical records for women who reported a stroke on a follow-up questionnaire.

Dr. Rist and her colleagues analyzed 27,937 samples for levels of LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. They assigned each sample to one of five cholesterol level categories that were based on Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Cox proportional hazards models enabled the researchers to calculate the hazard ratio of incident hemorrhagic stroke events. They adjusted their results for covariates such as age, smoking status, menopausal status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

A U-shaped association

Women in the lowest category of LDL cholesterol level (less than 70 mg/dL) were younger, less likely to have a history of hypertension, and less likely to use cholesterol-lowering drugs than women in the reference group (100.0-129.9 mg/dL). Women with the lowest LDL cholesterol level were more likely to consume alcohol, have a normal weight, engage in physical activity, and be premenopausal than women in the reference group. The investigators confirmed 137 incident hemorrhagic stroke events during a mean 19.3 years of follow-up.

After data adjustment, the researchers found that women with the lowest level of LDL cholesterol had 2.17 times the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with participants in the reference group. They found a trend toward increased risk among women with an LDL cholesterol level of 160 mg/dL or higher, but the result was not statistically significant. The highest risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) was among women with an LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL (relative risk, 2.32), followed by women with a level of 160 mg/dL or higher (RR, 1.71).

In addition, after multivariable adjustment, women in the lowest quartile of triglycerides (less than or equal to 74 mg/dL for fasting and less than or equal to 85 mg/dL for nonfasting) had a significantly increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with women in the highest quartile (RR, 2.00). Low triglyceride levels were associated with an increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, but not with an increased risk of ICH. Neither HDL cholesterol nor total cholesterol was associated with risk of hemorrhagic stroke, the researchers wrote.

Mechanism of increased risk unclear

The researchers do not yet know how low triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. One hypothesis is that low cholesterol promotes necrosis of the arterial medial layer’s smooth muscle cells. This impaired endothelium might be more susceptible to microaneurysms, which are common in patients with ICH, said the researchers.

The prospective design and the large sample size were two of the study’s strengths, but the study had important weaknesses as well, the researchers wrote. For example, few women were premenopausal at baseline, so the investigators could not evaluate whether menopausal status modifies the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, lipid levels were measured only at baseline, which prevented an analysis of whether change in lipid levels over time modifies the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Dr. Rist reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Rist PM et al. Neurology. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007454.

, according to research published in Neurology.

“Women with very low LDL cholesterol or low triglycerides should be monitored by their doctors for other stroke risk factors that can be modified, like high blood pressure and smoking, in order to reduce their risk of hemorrhagic stroke,” said Pamela M. Rist, ScD, instructor in epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Additional research is needed to determine how to lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women with very low LDL and low triglycerides.”

Several meta-analyses have indicated that LDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Because lipid-lowering treatments are used to prevent cardiovascular disease, this potential association has implications for clinical practice. Most of the studies included in these meta-analyses had low numbers of events among women, which prevented researchers from stratifying their results by sex. Because women are at greater risk of stroke than men, Dr. Rist and her colleagues sought to evaluate the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

An analysis of the Women’s Health Study

The investigators examined data from the Women’s Health Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among female American health professionals aged 45 years or older. The study ended in March 2004, but follow-up is ongoing. At regular intervals, the women complete a questionnaire about disease outcomes, including stroke. Some participants agreed to provide a fasting venous blood sample before randomization. With the subjects’ permission, a committee of physicians examined medical records for women who reported a stroke on a follow-up questionnaire.

Dr. Rist and her colleagues analyzed 27,937 samples for levels of LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. They assigned each sample to one of five cholesterol level categories that were based on Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Cox proportional hazards models enabled the researchers to calculate the hazard ratio of incident hemorrhagic stroke events. They adjusted their results for covariates such as age, smoking status, menopausal status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

A U-shaped association

Women in the lowest category of LDL cholesterol level (less than 70 mg/dL) were younger, less likely to have a history of hypertension, and less likely to use cholesterol-lowering drugs than women in the reference group (100.0-129.9 mg/dL). Women with the lowest LDL cholesterol level were more likely to consume alcohol, have a normal weight, engage in physical activity, and be premenopausal than women in the reference group. The investigators confirmed 137 incident hemorrhagic stroke events during a mean 19.3 years of follow-up.

After data adjustment, the researchers found that women with the lowest level of LDL cholesterol had 2.17 times the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with participants in the reference group. They found a trend toward increased risk among women with an LDL cholesterol level of 160 mg/dL or higher, but the result was not statistically significant. The highest risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) was among women with an LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL (relative risk, 2.32), followed by women with a level of 160 mg/dL or higher (RR, 1.71).

In addition, after multivariable adjustment, women in the lowest quartile of triglycerides (less than or equal to 74 mg/dL for fasting and less than or equal to 85 mg/dL for nonfasting) had a significantly increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with women in the highest quartile (RR, 2.00). Low triglyceride levels were associated with an increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, but not with an increased risk of ICH. Neither HDL cholesterol nor total cholesterol was associated with risk of hemorrhagic stroke, the researchers wrote.

Mechanism of increased risk unclear

The researchers do not yet know how low triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. One hypothesis is that low cholesterol promotes necrosis of the arterial medial layer’s smooth muscle cells. This impaired endothelium might be more susceptible to microaneurysms, which are common in patients with ICH, said the researchers.

The prospective design and the large sample size were two of the study’s strengths, but the study had important weaknesses as well, the researchers wrote. For example, few women were premenopausal at baseline, so the investigators could not evaluate whether menopausal status modifies the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In addition, lipid levels were measured only at baseline, which prevented an analysis of whether change in lipid levels over time modifies the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Dr. Rist reported receiving a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Rist PM et al. Neurology. 2019 April 10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007454.

, according to research published in Neurology.

“Women with very low LDL cholesterol or low triglycerides should be monitored by their doctors for other stroke risk factors that can be modified, like high blood pressure and smoking, in order to reduce their risk of hemorrhagic stroke,” said Pamela M. Rist, ScD, instructor in epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Additional research is needed to determine how to lower the risk of hemorrhagic stroke in women with very low LDL and low triglycerides.”

Several meta-analyses have indicated that LDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Because lipid-lowering treatments are used to prevent cardiovascular disease, this potential association has implications for clinical practice. Most of the studies included in these meta-analyses had low numbers of events among women, which prevented researchers from stratifying their results by sex. Because women are at greater risk of stroke than men, Dr. Rist and her colleagues sought to evaluate the association between lipid levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

An analysis of the Women’s Health Study

The investigators examined data from the Women’s Health Study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose aspirin and vitamin E for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer among female American health professionals aged 45 years or older. The study ended in March 2004, but follow-up is ongoing. At regular intervals, the women complete a questionnaire about disease outcomes, including stroke. Some participants agreed to provide a fasting venous blood sample before randomization. With the subjects’ permission, a committee of physicians examined medical records for women who reported a stroke on a follow-up questionnaire.

Dr. Rist and her colleagues analyzed 27,937 samples for levels of LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. They assigned each sample to one of five cholesterol level categories that were based on Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Cox proportional hazards models enabled the researchers to calculate the hazard ratio of incident hemorrhagic stroke events. They adjusted their results for covariates such as age, smoking status, menopausal status, body mass index, and alcohol consumption.

A U-shaped association

Women in the lowest category of LDL cholesterol level (less than 70 mg/dL) were younger, less likely to have a history of hypertension, and less likely to use cholesterol-lowering drugs than women in the reference group (100.0-129.9 mg/dL). Women with the lowest LDL cholesterol level were more likely to consume alcohol, have a normal weight, engage in physical activity, and be premenopausal than women in the reference group. The investigators confirmed 137 incident hemorrhagic stroke events during a mean 19.3 years of follow-up.

After data adjustment, the researchers found that women with the lowest level of LDL cholesterol had 2.17 times the risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with participants in the reference group. They found a trend toward increased risk among women with an LDL cholesterol level of 160 mg/dL or higher, but the result was not statistically significant. The highest risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) was among women with an LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL (relative risk, 2.32), followed by women with a level of 160 mg/dL or higher (RR, 1.71).

In addition, after multivariable adjustment, women in the lowest quartile of triglycerides (less than or equal to 74 mg/dL for fasting and less than or equal to 85 mg/dL for nonfasting) had a significantly increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke, compared with women in the highest quartile (RR, 2.00). Low triglyceride levels were associated with an increased risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage, but not with an increased risk of ICH. Neither HDL cholesterol nor total cholesterol was associated with risk of hemorrhagic stroke, the researchers wrote.

Mechanism of increased risk unclear

The researchers do not yet know how low triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. One hypothesis is that low cholesterol promotes necrosis of the arterial medial layer’s smooth muscle cells. This impaired endothelium might be more susceptible to microaneurysms, which are common in patients with ICH, said the researchers.