User login

Adding a Cream May Enhance Flu Vaccine Effectiveness

Can a cream help a flu vaccine work better? In a phase 1 clinical trial, researchers from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, are testing whether imiquimod cream—commonly used to treat genital warts and some skin cancers—can boost the immune response to an H5N1 flu vaccine. Studies have shown imiquimod generates significantly more robust immune responses.

Participants in the Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units trial will be given 2 intradermal doses of an H5N1 vaccine, 21 days apart. In one group, participants will have Aldara (imiquimod cream) applied to their upper arm before each vaccination; in the control group, a placebo cream will be applied.

Participants will return at regular intervals over 7 months to have blood drawn; they also will keep diaries to record symptoms.

The first participant was vaccinated in June. Early results are expected by the end of the year.

Can a cream help a flu vaccine work better? In a phase 1 clinical trial, researchers from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, are testing whether imiquimod cream—commonly used to treat genital warts and some skin cancers—can boost the immune response to an H5N1 flu vaccine. Studies have shown imiquimod generates significantly more robust immune responses.

Participants in the Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units trial will be given 2 intradermal doses of an H5N1 vaccine, 21 days apart. In one group, participants will have Aldara (imiquimod cream) applied to their upper arm before each vaccination; in the control group, a placebo cream will be applied.

Participants will return at regular intervals over 7 months to have blood drawn; they also will keep diaries to record symptoms.

The first participant was vaccinated in June. Early results are expected by the end of the year.

Can a cream help a flu vaccine work better? In a phase 1 clinical trial, researchers from Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, are testing whether imiquimod cream—commonly used to treat genital warts and some skin cancers—can boost the immune response to an H5N1 flu vaccine. Studies have shown imiquimod generates significantly more robust immune responses.

Participants in the Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units trial will be given 2 intradermal doses of an H5N1 vaccine, 21 days apart. In one group, participants will have Aldara (imiquimod cream) applied to their upper arm before each vaccination; in the control group, a placebo cream will be applied.

Participants will return at regular intervals over 7 months to have blood drawn; they also will keep diaries to record symptoms.

The first participant was vaccinated in June. Early results are expected by the end of the year.

CDC: Trivalent adjuvanted influenza vaccine aIIV3 safe in elderly adults

ATLANTA – according to an analysis of reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) during July 2016 through March 2018.

VAERS received 630 reports related to the vaccine (aIIV3; FLUAD) during the study period, of which 521 involved adults aged 65 years and older.

“Eighteen (3%) were serious reports, including two death reports (0.4%), all in adults aged [at least] 65 years,” Penina Haber and her colleagues at the Immunization Safety Office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The deaths included a 75-year-old man who died from Sjögren’s syndrome and a 65-year-old man who died from a myocardial infarction. The other serious events included five neurologic disorders (two cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome and one each of Bell’s palsy, Bickerstaff encephalitis, and lower-extremity weakness), five musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (three with shoulder pain and two with arm pain), three general disorders and administration site conditions (two cases of fever/chills and one case of cellulitis/bursitis), and one case each of a gastrointestinal disorder (acute diarrhea/gastroenteritis), an injury (a fall), and a skin/subcutaneous tissue disorder (keratosis pilaris rubra), according to the investigators.

There were no reports of anaphylaxis.

For the sake of comparison, the investigators also looked at reports associated with IIV3-HD and IIV3/IIV4 vaccines in adults aged 65 years and older during the same time period; they found that patient characteristics and reported events were similar for all the vaccines. For example, the percentages of reports involving patients aged 65 years and older were 65% or 66% for each, and those involving patients aged 75-84 years were 27%-29%. Further, 0.2%-0.6% of reports for each vaccine involved death.

The most frequently reported events for aIIV3, IIV3-HD, and IIV3/IIV4, respectively, were extremity pain (21%, 17%, and 15%, respectively), injection site erythema (18%, 19%, and 15%), and injection site pain (15%, 16%, and 16%), they said.

The aIIV3 vaccine – the first seasonal inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine produced from three influenza virus strains (two subtype A strains and one type B strain) – was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for adults aged 65 years and older. It was the first influenza vaccine containing the adjuvant MF59 – a purified oil-in-water emulsion of squalene oil added to boost immune response in that population. Its safety was assessed in 15 randomized, controlled clinical studies, and several trials in older adults supported its efficacy and safety over nonadjuvanted influenza vaccines, the investigators reported. They noted that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the vaccine as an option for routine use in adults aged 65 years and older during the 2016-2017 flu seasons.

For the 2018-2019 flu season, ACIP determined that “For persons aged ≥65 years, any age-appropriate IIV formulation (standard-dose or high-dose, trivalent or quadrivalent, unadjuvanted or adjuvanted) or RIV4 are acceptable options.”

The findings of the analysis of the 2017-2018 flu season data are consistent with prelicensure studies, Ms. Haber and her colleagues concluded, noting that data mining did not detect disproportional reporting of any unexpected adverse event.

“[There were] no safety concerns following aIIV3 when compared to the nonadjuvanted influenza vaccines (IIV3-HD or IIV3/IIV4),” they wrote, adding that the “CDC and FDA will continue to monitor and ensure the safety of aIIV3.”

Ms. Haber reported having no disclosures

SOURCE: Haber P et al. ICEID 2018, Board 320.

ATLANTA – according to an analysis of reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) during July 2016 through March 2018.

VAERS received 630 reports related to the vaccine (aIIV3; FLUAD) during the study period, of which 521 involved adults aged 65 years and older.

“Eighteen (3%) were serious reports, including two death reports (0.4%), all in adults aged [at least] 65 years,” Penina Haber and her colleagues at the Immunization Safety Office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The deaths included a 75-year-old man who died from Sjögren’s syndrome and a 65-year-old man who died from a myocardial infarction. The other serious events included five neurologic disorders (two cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome and one each of Bell’s palsy, Bickerstaff encephalitis, and lower-extremity weakness), five musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (three with shoulder pain and two with arm pain), three general disorders and administration site conditions (two cases of fever/chills and one case of cellulitis/bursitis), and one case each of a gastrointestinal disorder (acute diarrhea/gastroenteritis), an injury (a fall), and a skin/subcutaneous tissue disorder (keratosis pilaris rubra), according to the investigators.

There were no reports of anaphylaxis.

For the sake of comparison, the investigators also looked at reports associated with IIV3-HD and IIV3/IIV4 vaccines in adults aged 65 years and older during the same time period; they found that patient characteristics and reported events were similar for all the vaccines. For example, the percentages of reports involving patients aged 65 years and older were 65% or 66% for each, and those involving patients aged 75-84 years were 27%-29%. Further, 0.2%-0.6% of reports for each vaccine involved death.

The most frequently reported events for aIIV3, IIV3-HD, and IIV3/IIV4, respectively, were extremity pain (21%, 17%, and 15%, respectively), injection site erythema (18%, 19%, and 15%), and injection site pain (15%, 16%, and 16%), they said.

The aIIV3 vaccine – the first seasonal inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine produced from three influenza virus strains (two subtype A strains and one type B strain) – was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for adults aged 65 years and older. It was the first influenza vaccine containing the adjuvant MF59 – a purified oil-in-water emulsion of squalene oil added to boost immune response in that population. Its safety was assessed in 15 randomized, controlled clinical studies, and several trials in older adults supported its efficacy and safety over nonadjuvanted influenza vaccines, the investigators reported. They noted that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the vaccine as an option for routine use in adults aged 65 years and older during the 2016-2017 flu seasons.

For the 2018-2019 flu season, ACIP determined that “For persons aged ≥65 years, any age-appropriate IIV formulation (standard-dose or high-dose, trivalent or quadrivalent, unadjuvanted or adjuvanted) or RIV4 are acceptable options.”

The findings of the analysis of the 2017-2018 flu season data are consistent with prelicensure studies, Ms. Haber and her colleagues concluded, noting that data mining did not detect disproportional reporting of any unexpected adverse event.

“[There were] no safety concerns following aIIV3 when compared to the nonadjuvanted influenza vaccines (IIV3-HD or IIV3/IIV4),” they wrote, adding that the “CDC and FDA will continue to monitor and ensure the safety of aIIV3.”

Ms. Haber reported having no disclosures

SOURCE: Haber P et al. ICEID 2018, Board 320.

ATLANTA – according to an analysis of reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) during July 2016 through March 2018.

VAERS received 630 reports related to the vaccine (aIIV3; FLUAD) during the study period, of which 521 involved adults aged 65 years and older.

“Eighteen (3%) were serious reports, including two death reports (0.4%), all in adults aged [at least] 65 years,” Penina Haber and her colleagues at the Immunization Safety Office at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The deaths included a 75-year-old man who died from Sjögren’s syndrome and a 65-year-old man who died from a myocardial infarction. The other serious events included five neurologic disorders (two cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome and one each of Bell’s palsy, Bickerstaff encephalitis, and lower-extremity weakness), five musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (three with shoulder pain and two with arm pain), three general disorders and administration site conditions (two cases of fever/chills and one case of cellulitis/bursitis), and one case each of a gastrointestinal disorder (acute diarrhea/gastroenteritis), an injury (a fall), and a skin/subcutaneous tissue disorder (keratosis pilaris rubra), according to the investigators.

There were no reports of anaphylaxis.

For the sake of comparison, the investigators also looked at reports associated with IIV3-HD and IIV3/IIV4 vaccines in adults aged 65 years and older during the same time period; they found that patient characteristics and reported events were similar for all the vaccines. For example, the percentages of reports involving patients aged 65 years and older were 65% or 66% for each, and those involving patients aged 75-84 years were 27%-29%. Further, 0.2%-0.6% of reports for each vaccine involved death.

The most frequently reported events for aIIV3, IIV3-HD, and IIV3/IIV4, respectively, were extremity pain (21%, 17%, and 15%, respectively), injection site erythema (18%, 19%, and 15%), and injection site pain (15%, 16%, and 16%), they said.

The aIIV3 vaccine – the first seasonal inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine produced from three influenza virus strains (two subtype A strains and one type B strain) – was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for adults aged 65 years and older. It was the first influenza vaccine containing the adjuvant MF59 – a purified oil-in-water emulsion of squalene oil added to boost immune response in that population. Its safety was assessed in 15 randomized, controlled clinical studies, and several trials in older adults supported its efficacy and safety over nonadjuvanted influenza vaccines, the investigators reported. They noted that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the vaccine as an option for routine use in adults aged 65 years and older during the 2016-2017 flu seasons.

For the 2018-2019 flu season, ACIP determined that “For persons aged ≥65 years, any age-appropriate IIV formulation (standard-dose or high-dose, trivalent or quadrivalent, unadjuvanted or adjuvanted) or RIV4 are acceptable options.”

The findings of the analysis of the 2017-2018 flu season data are consistent with prelicensure studies, Ms. Haber and her colleagues concluded, noting that data mining did not detect disproportional reporting of any unexpected adverse event.

“[There were] no safety concerns following aIIV3 when compared to the nonadjuvanted influenza vaccines (IIV3-HD or IIV3/IIV4),” they wrote, adding that the “CDC and FDA will continue to monitor and ensure the safety of aIIV3.”

Ms. Haber reported having no disclosures

SOURCE: Haber P et al. ICEID 2018, Board 320.

REPORTING FROM ICEID 2018

Key clinical point: No new or unexpected adverse events were reported among the 630 reports related to the vaccine during the study period, of which 521 involved adults aged 65 years and older.

Major finding: Of 521 reports, 18 were serious, and there were two deaths.

Study details: A review of 521 reports to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System in 2017-2018.

Disclosures: Ms. Haber reported having no disclosures.

Source: Haber P et al. ICEID 2018, Board 320.

PCV13 moderately effective in older adults

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

ATLANTA – (IPD) caused by PCV13 vaccine serotypes in adults aged 65 years and older, according to a case-control study involving Medicare beneficiaries.

Conversely, the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) showed limited effectiveness against serotypes unique to that vaccine in the study, which included 699 cases and more than 10,000 controls, Olivia Almendares, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Vaccine efficacy against PCV13 [plus 6C type, which has cross-reactivity with serotype 6A] was 47% in those who received PCV13 vaccine only,” Ms. Almendares said in an interview, noting that efficacy was 26% against serotype 3 and 67% against other PCV13 serotypes (plus 6C). “Vaccine efficacy against PPSV23-unique types was 36% for those who received only PPSV23.”

Neither vaccine showed effectiveness against serotypes not included in the respective vaccines, she said.

The findings are timely given that the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) is reevaluating its PCV13 recommendation for adults aged 65 years and older, she added.

“Specifically, ACIP is addressing whether PCV13 should be recommended routinely for all immunocompetent adults aged 65 and older given sustained indirect effects,” she said, explaining that, in 2014 when ACIP recommended routine use of the vaccine in series with PPSV23 for adults aged 65 years and older, the committee recognized that herd immunity effects from PCV13 use in children might eventually limit the utility of this recommendation, and therefore it proposed reevaluation and revision as needed after 4 years.

For the current study, she and her colleagues linked IPD cases in persons aged 65 years and older, which were identified through Active Bacterial Core surveillance during 2015-2016, to records for Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) beneficiaries. Vaccination and medical histories were obtained through medical records, and vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the odds ratio for vaccination with PCV13 only or PPSV23 only versus neither vaccine using conditional logistic regression, with adjustment for sex and underlying medical conditions.

Of 2,246 IPD cases, 1,017 (45%) were matched to Medicare beneficiaries, and 699 were included in the analysis after those with noncontinuous enrollment in Medicare, long-term care residence, and missing census tract data were excluded. The cases were matched based on age, census tract of residence, and length of Medicare enrollment to 10,152 matched controls identified through CMS.

IPD associated with PCV13 (plus type 6C) accounted for 164 (23% of cases), of which 88 (12% of cases) involved serotype 3, and invasive pneumococcal disease associated with PPSV23 accounted for 350 cases (50%), she said.

PCV13 vaccine was given alone in 14% and 18% of cases and controls, respectively; PPSV23 alone was given in 22% and 21% of case patients and controls, respectively; and both vaccines were given in 8% of cases and controls.

Compared with controls, case patients were more likely to be of nonwhite race (16% vs. 11%), to have more than one chronic medical condition (88% vs. 58%), and to have one or more immunocompromising conditions (54% vs. 32%), she and her colleagues reported.

“PCV13 showed moderate overall effectiveness in preventing IPD caused by PCV13 (including 6C), but effectiveness may be lower for serotype 3 than for other PCV13 types,” she said.

“These results are in agreement with those from CAPiTA – a large clinical trial conducted in the Netherlands, which showed PCV13 to be effective against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older,” she noted. “Additionally, data from CDC surveillance suggest that PCV13-serotype [invasive pneumococcal disease] among children and adults aged 65 and older has declined dramatically following PCV13 introduction for children in 2010, as predicted.”

In fact, among adults aged 65 years and older, PCV13-serotype invasive pneumococcal disease declined by 40% after the vaccine was introduced in children. This corresponds to a change in the annual PCV13-serotype incidence from 14 cases per 100,000 population in 2010 to five cases per 100,000 population in 2014, she said; she added that IPD incidence plateaued in 2014-2016 with vaccine serotypes contributing to a small proportion of overall IPD burden among adults aged 65 years and older.

ACIP’s reevaluation of the PCV13 recommendation is ongoing and will be addressed at upcoming meetings.

“As part of the review process, we look at changes in disease incidence focusing primarily on invasive pneumococcal disease and noninvasive pneumonia, vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, and vaccine safety,” she said. She noted that ACIP currently has no plans to consider revising PCV13 recommendations for adults who have immunocompromising conditions, for whom PCV13 has been recommended since 2012.

Ms. Almendares reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Almendares O et al. ICEID 2018, Board 376.

REPORTING FROM ICEID 2018

Take these steps to improve your flu season preparedness

Last year’s influenza season was severe enough that hospitals around the United States set up special evaluation areas beyond their emergency departments, at times spilling over to tents or other temporary structures in what otherwise would be parking lots. The scale and potential severity of the annual epidemic can be difficult to convey to our patients, who sometimes say “just the flu” to refer to an illness responsible for more than 170 pediatric deaths in the United States this past year.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently updated its 5-year estimates of influenza-related deaths in the United States; influenza mortality ranges from about 12,000 deaths in a mild season (such as 2011-2012) to 56,000 in a more severe season (eg, 2012-2013).2

Although influenza cannot be completely prevented, the following strategies can help reduce the risk for the illness and limit its severity if contracted.

Prevention

Strategy 1: Vaccinate against influenza

While the efficacy of vaccines varies from year to year, vaccination remains the core of influenza prevention efforts. In this decade, vaccine effectiveness has ranged from 19% to 60%.3 However, models suggest that even when the vaccine is only 20% effective, vaccinating 140 million people (the average number of doses delivered annually in the United States over the past 5 seasons) prevents 21 million infections, 130,000 hospitalizations, and more than 61,000 deaths.4 In a case-control study, Flannery et al found that vaccination was 65% effective in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated death in children over 4 seasons (July 2010 through June 2014).5

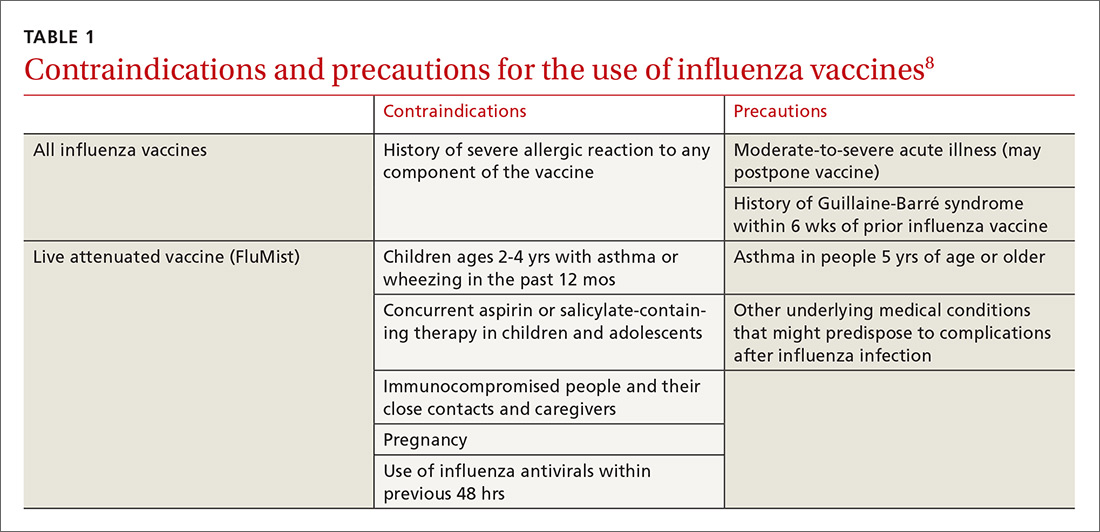

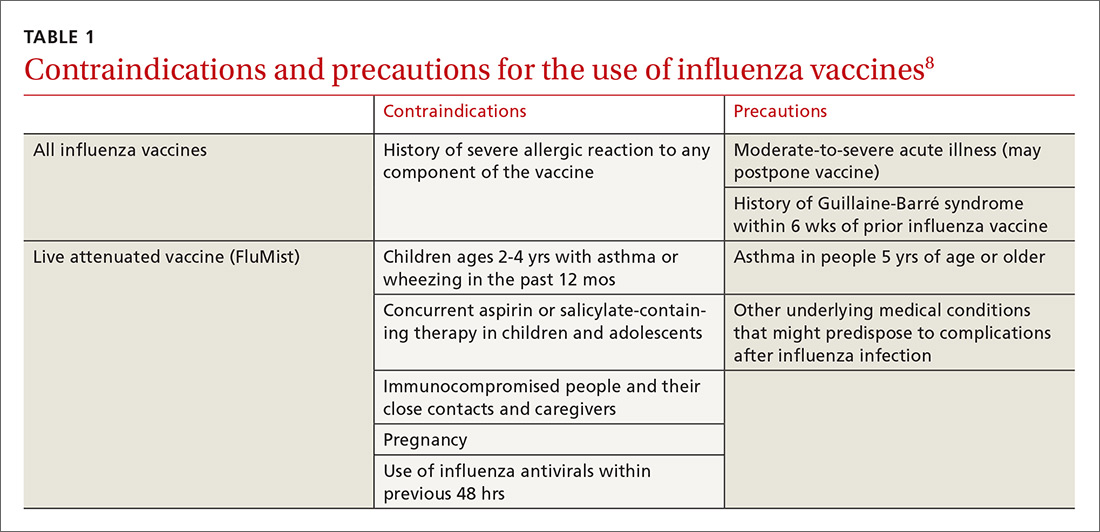

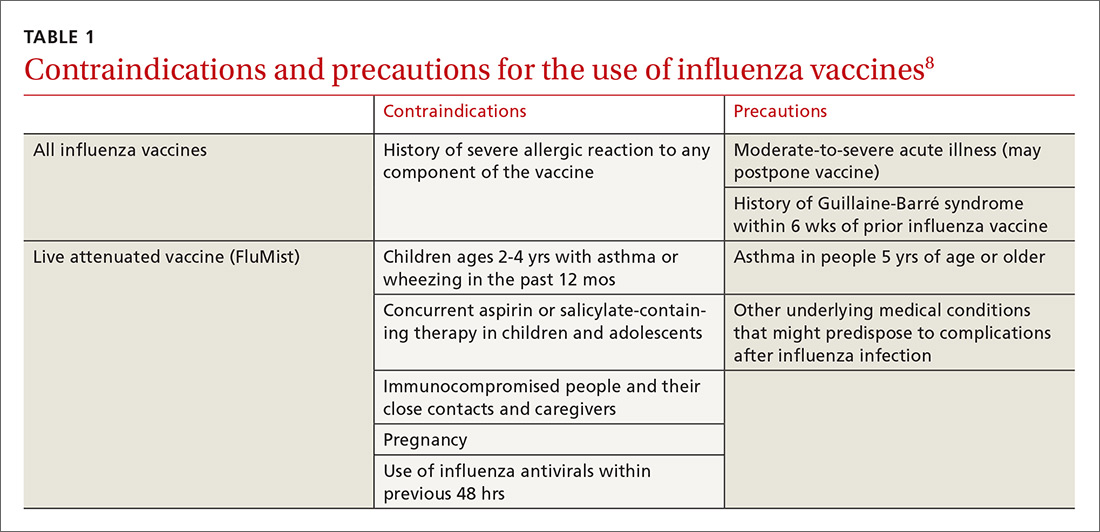

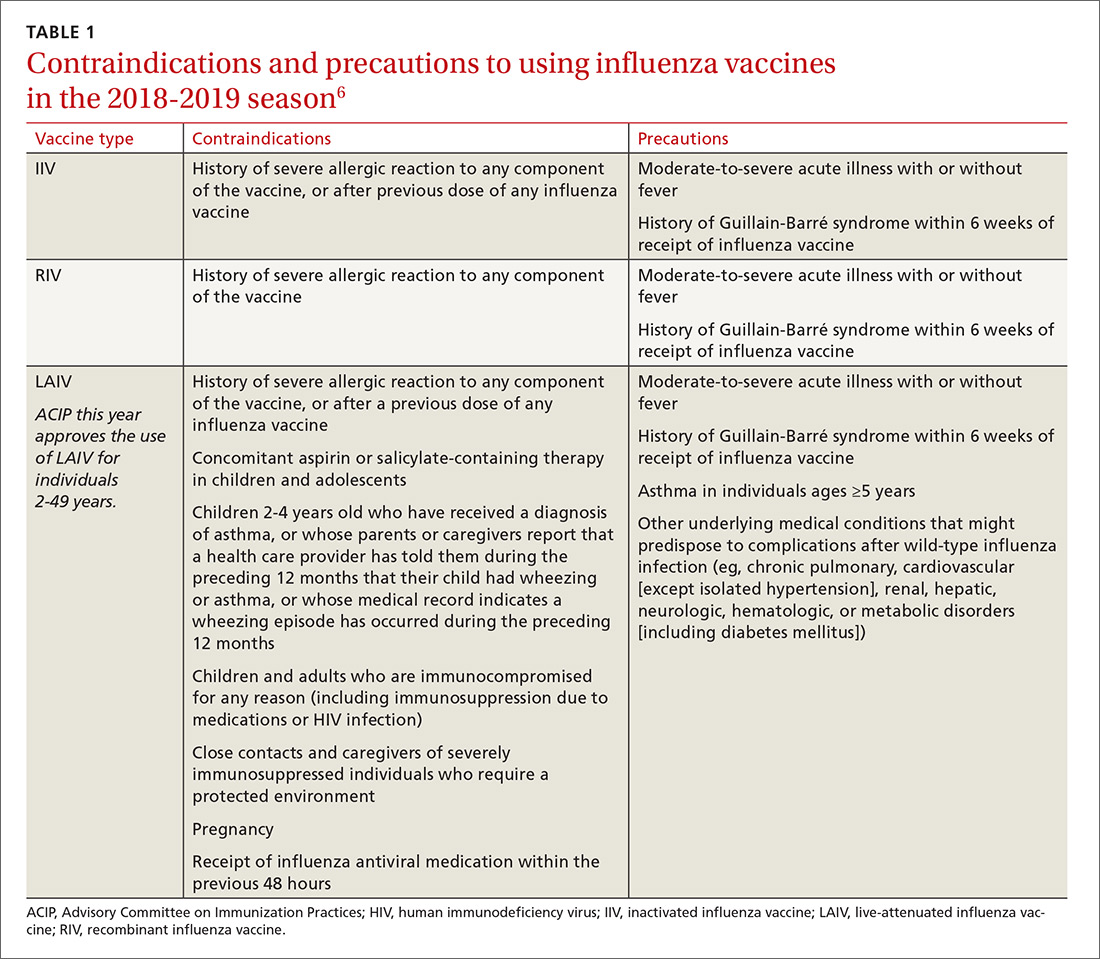

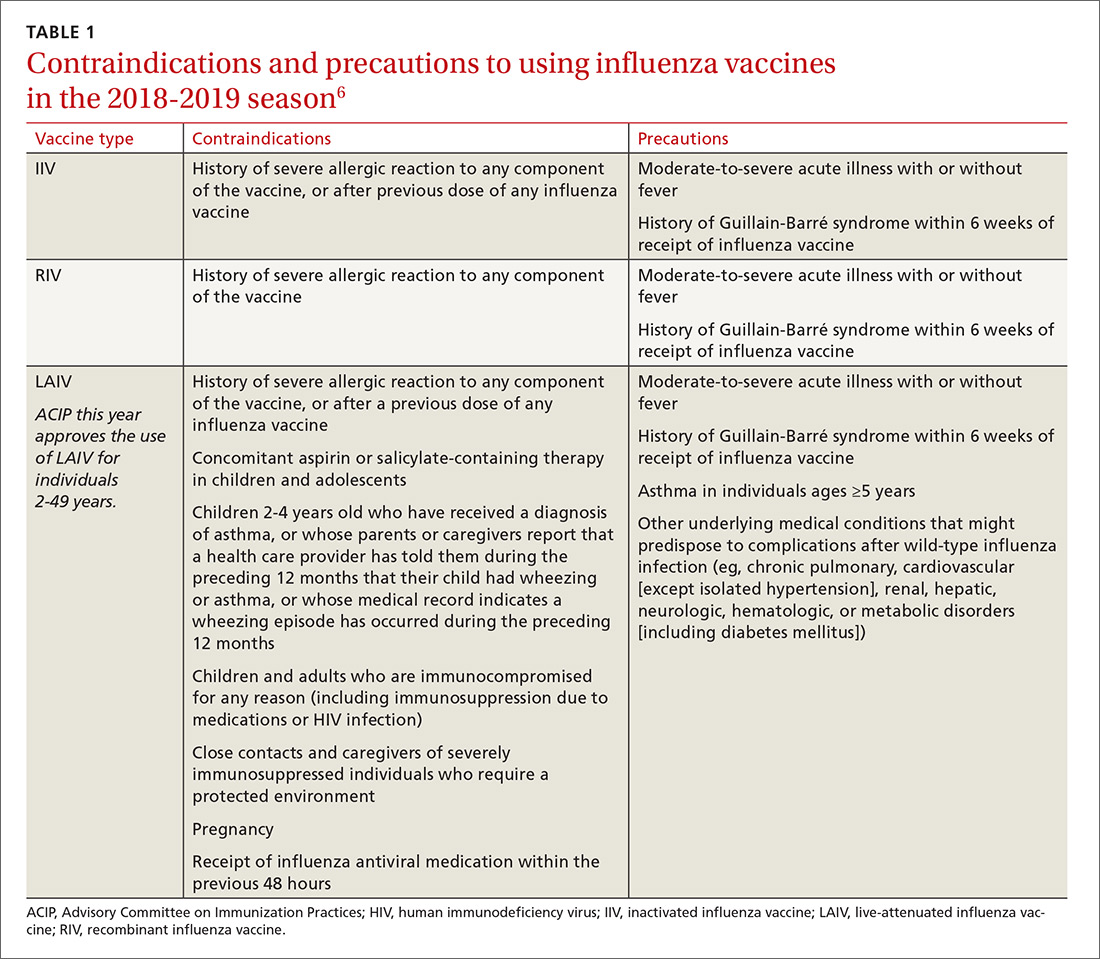

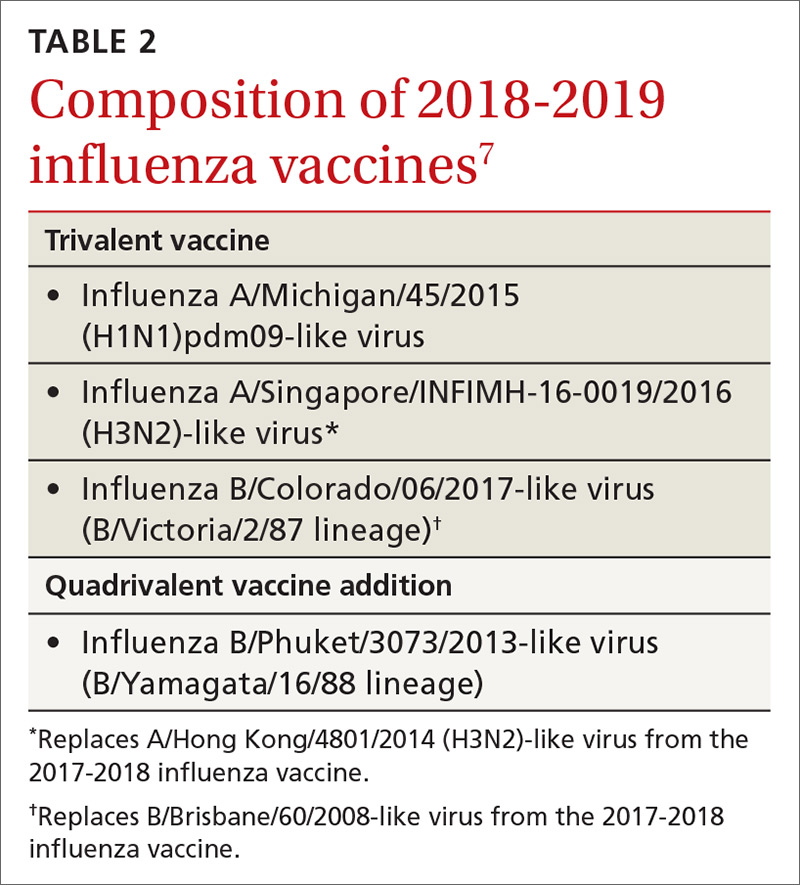

Deciding who should be vaccinated is simpler than in prior years: Rather than targeting people who are at higher risk (those ages 65 and older, or those with comorbidities), the current CDC recommendation is to vaccinate nearly everyone ages 6 months or older, with limited exceptions.6,7 (See Table 18).

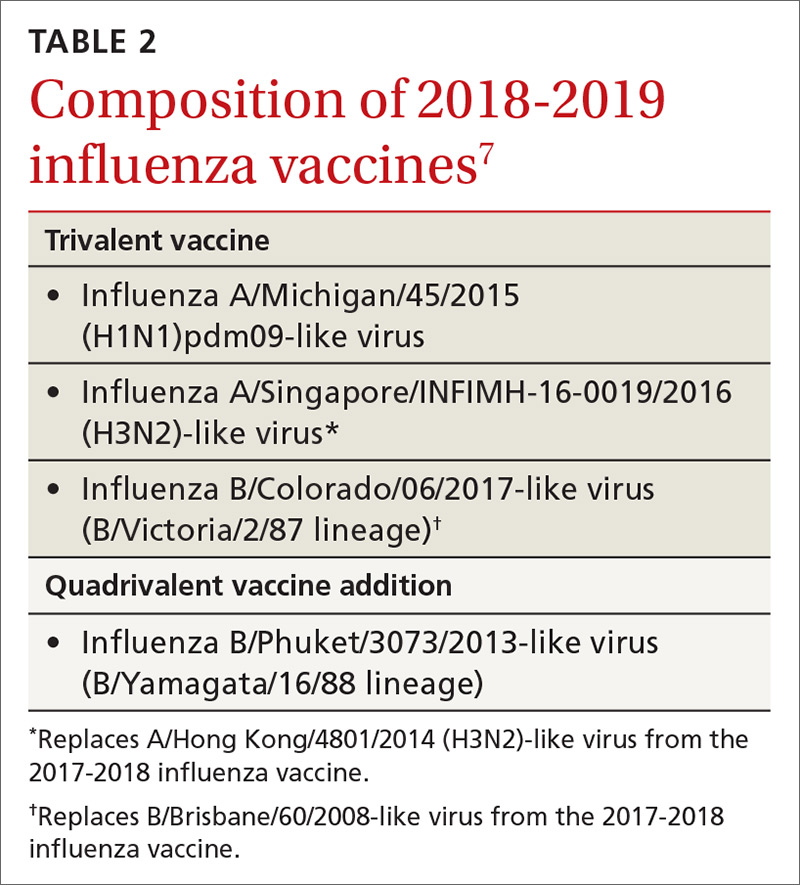

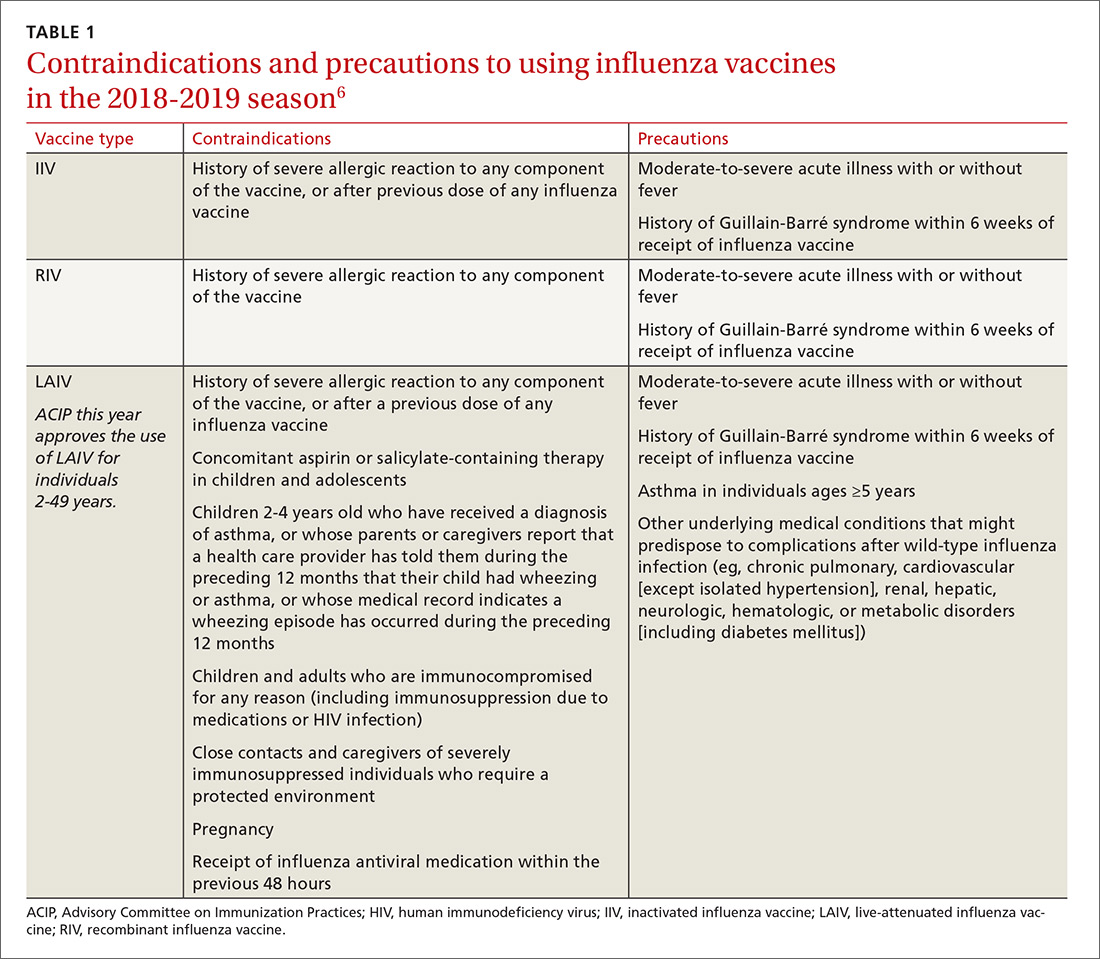

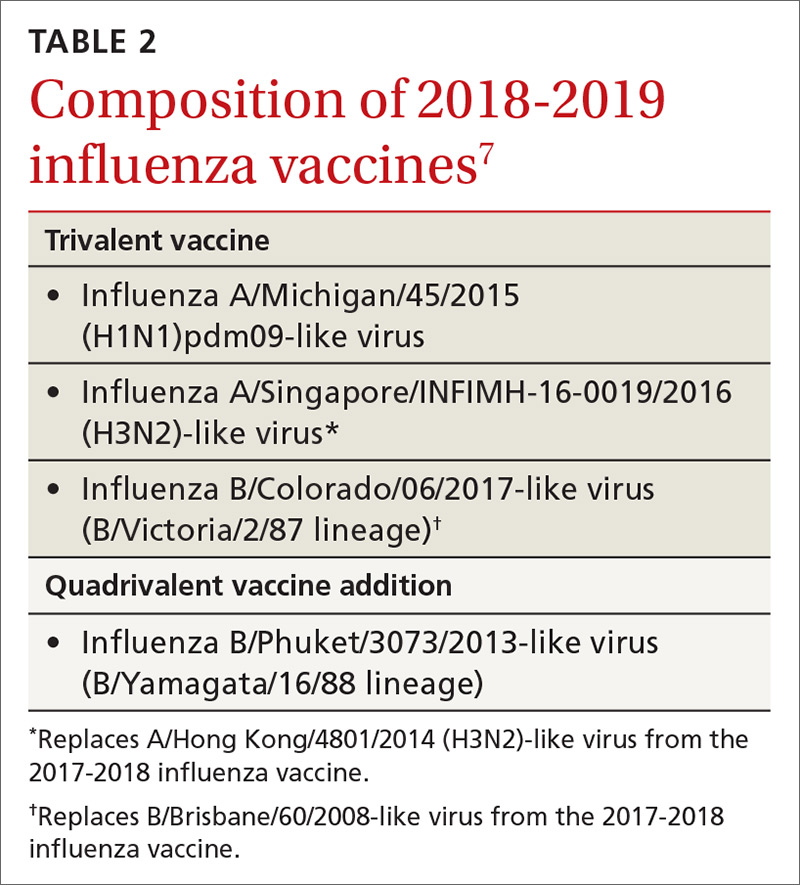

Formulations. Many types of influenza vaccine are approved for use in the United States; these differ in the number of strains included (3 or 4), the amount of antigen present for each strain, the presence of an adjuvant, the growth medium used for the virus, and the route of administration (see Table 29). The relative merits of each type are a matter of some debate. There is ongoing research into the comparative efficacy of vaccines comprised of egg- vs cell-based cultures, as well as studies comparing high-dose or adjuvant vaccines to standard-dose inactivated vaccines.

Previously, the CDC has recommended preferential use (or avoidance) of some vaccine types, based on their efficacy. For the 2018-2019 flu season, however, the CDC has rescinded its recommendation against vaccine containing live attenuated virus (LAIV; FluMist brand) and expresses no preference for any vaccine formulation for patients of appropriate age and health status.10 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), however, is recommends that LAIV be used only if patients and their families decline injectable vaccines.11

Timing. Influenza vaccines are now distributed as early as July to some locations, raising concerns about waning immunity from early vaccination (July/August) if the influenza season does not peak until February or March.8,12,13 Currently, the CDC recommends balancing the possible benefit of delayed vaccination against the risks of missed opportunities to vaccinate, a possible early season, and logistical problems related to vaccinating the same number of people in a smaller time interval. Offering vaccination by the end of October, if possible, is recommended in order for immunity to develop by mid-November.8 Note: Children ages 6 months to 8 years will need to receive their initial vaccination in 2 half-doses administered at least 28 days apart; completing their vaccination by the end of October would require starting the process weeks earlier.

[polldaddy:10124269]

Continue to: Strategy 2

Strategy 2: Make use of chemoprophylaxis

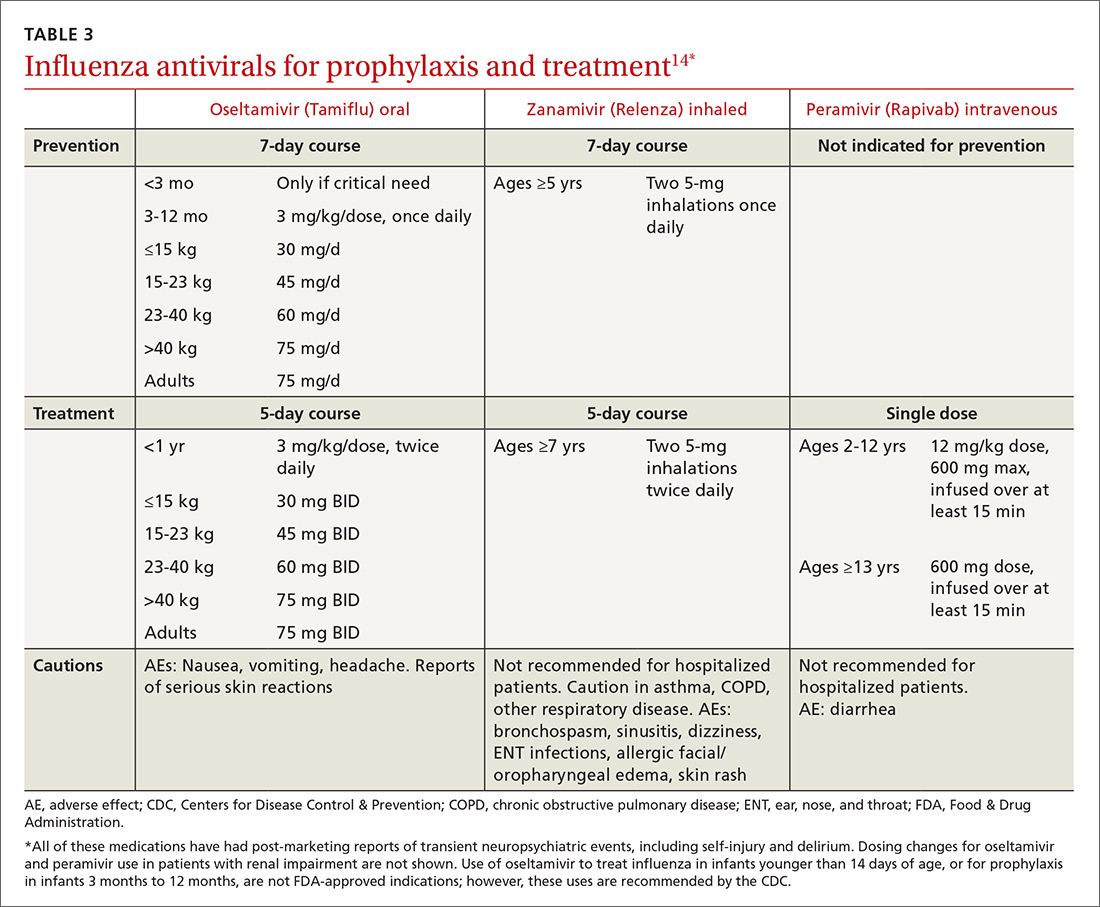

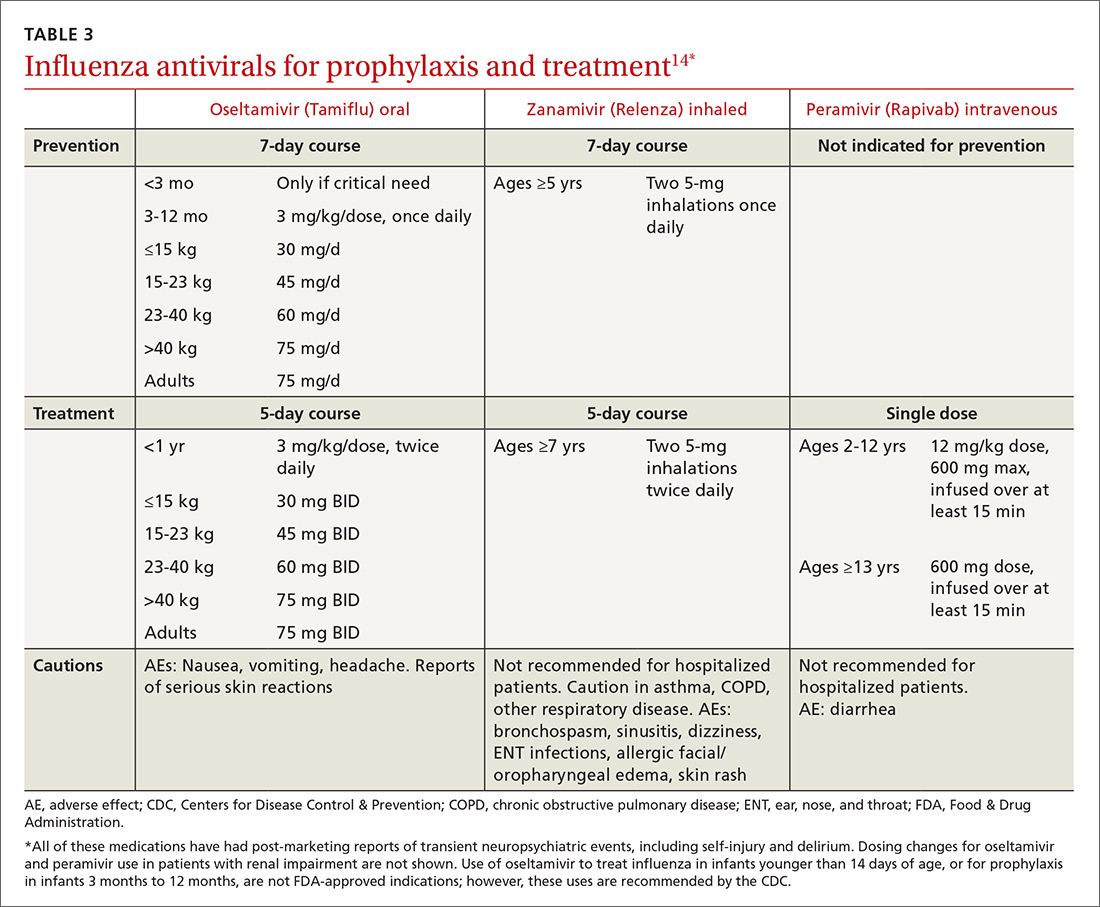

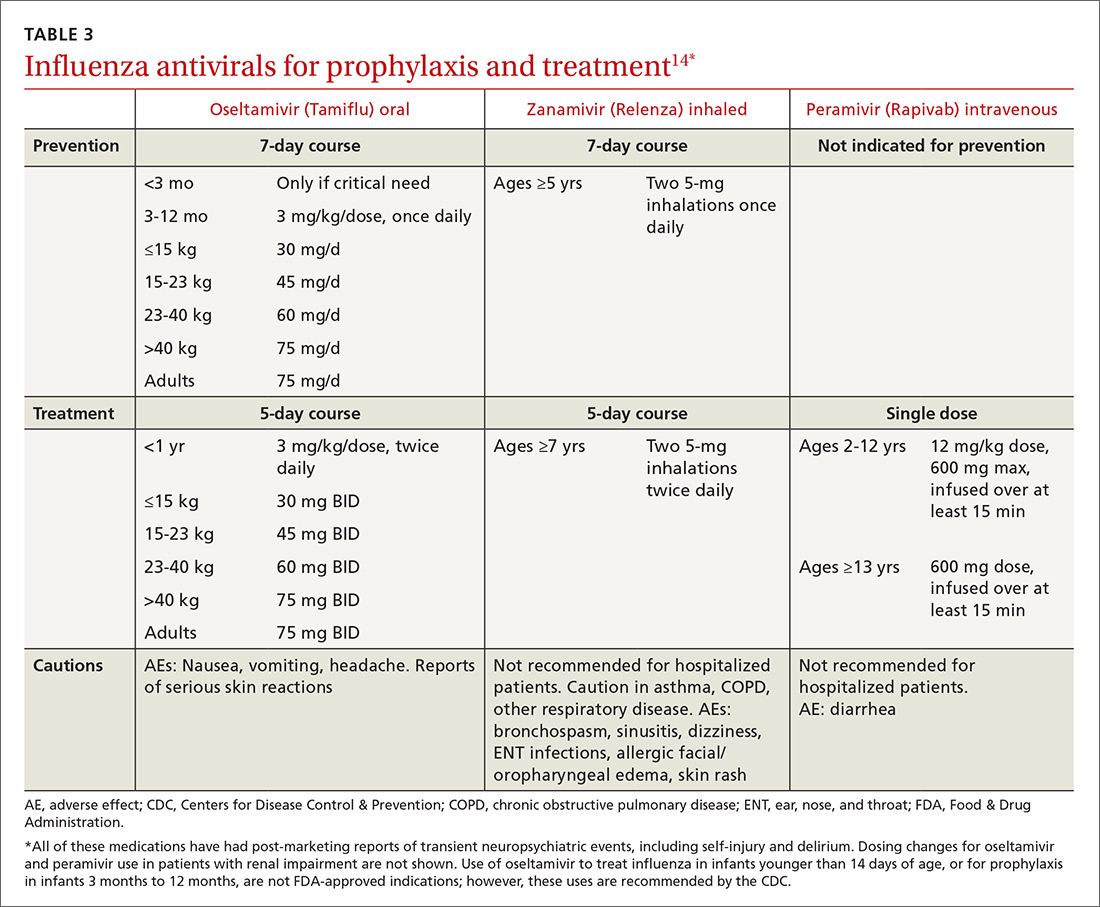

Preventive use of antiviral medication (chemoprophylaxis) may be a useful adjunct or alternative to vaccination in certain circumstances: if the patient is at high risk for complications, has been exposed to someone with influenza, has contraindications to vaccination, or received the vaccine within the past 2 weeks. The CDC also suggests that chemoprophylaxis be considered for those with immune deficiencies or who are otherwise immunosuppressed after exposure.14 Antivirals can also be used to control outbreaks in long-term care facilities; in these cases, the recommendedregimen is daily administration for at least 2 weeks, continuing until at least 7 days after the identification of the last case.14 Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are the recommended prophylactic agents; a related intravenous medication, peramivir (Rapivab), is recommend for treatment only (see Table 314).

Strategy 3: Prevent comorbidities and opportunistic infections

Morbidity associated with influenza often comes from secondary infection. Pneumonia is among the most common complications, so influenza season is a good time to ensure that patients are appropriately vaccinated against pneumococcus, as well. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar or PCV13) is recommended for children younger than 2 years of age, to be administered in a series of 4 doses: at 2, 4, 6, and 12-15 months. Vaccination with PCV13 is also recommended for those ages 65 or older, to be followed at least one year later with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax or PPSV23).15 Additional doses of PCV13, PPSV23, or both may be indicated, depending on health status.

Strategy 4: Encourage good hygiene

The availability of immunizations and antivirals does not replace good hygiene. Frequent handwashing reduces the transmission of respiratory viruses, including influenza.16 Few studies have evaluated the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, but available evidence suggests they are effective in lowering viral transmission.16

Barriers, such as masks, gloves, and gowns, are helpful for health care workers.16 Surgical masks are often considered more comfortable to wear than N95 respirators. It may therefore be welcome news that when a 2009 randomized study assessed their use by hospital-based nurses, masks were non-inferior in protecting these health care workers against influenza.17

Presenteeism, the practice of going to work while sick, should be discouraged. People at risk for influenza may wish to avoid crowds during flu season; those with symptoms should be encouraged to stay home and limit contact with others.

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment

Strategy 1: Make prompt use of antivirals

Despite available preventive measures, tens of millions of people in the United States develop influenza every year. Use of antiviral medication, begun early in the course of illness, can reduce the duration of symptoms and may reduce the risk for complications.

The neuraminidase inhibitor (NI) group of antivirals—oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir—is effective against influenza types A and B and current resistance rates are low.

The adamantine family of antivirals, amantadine and rimantadine, treat type A only. Since the circulating influenza strains in the past several seasons have demonstrated resistance >99%, these medications are not currently recommended.14

NIs reduce the duration of influenza symptoms by 10% to 20%, shortening the illness by 6 to 24 hours.18,19 In otherwise healthy patients, this benefit must be balanced against the increased risk for nausea and vomiting (oseltamivir), bronchospasm and sinusitis (zanamivir), and diarrhea (peramivir). In adults, NIs reduce the risk for lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalization. A 2015 meta-analysis by Dobson et al found a relative risk for hospitalization among those prescribed oseltamivir vs placebo of 37%.18

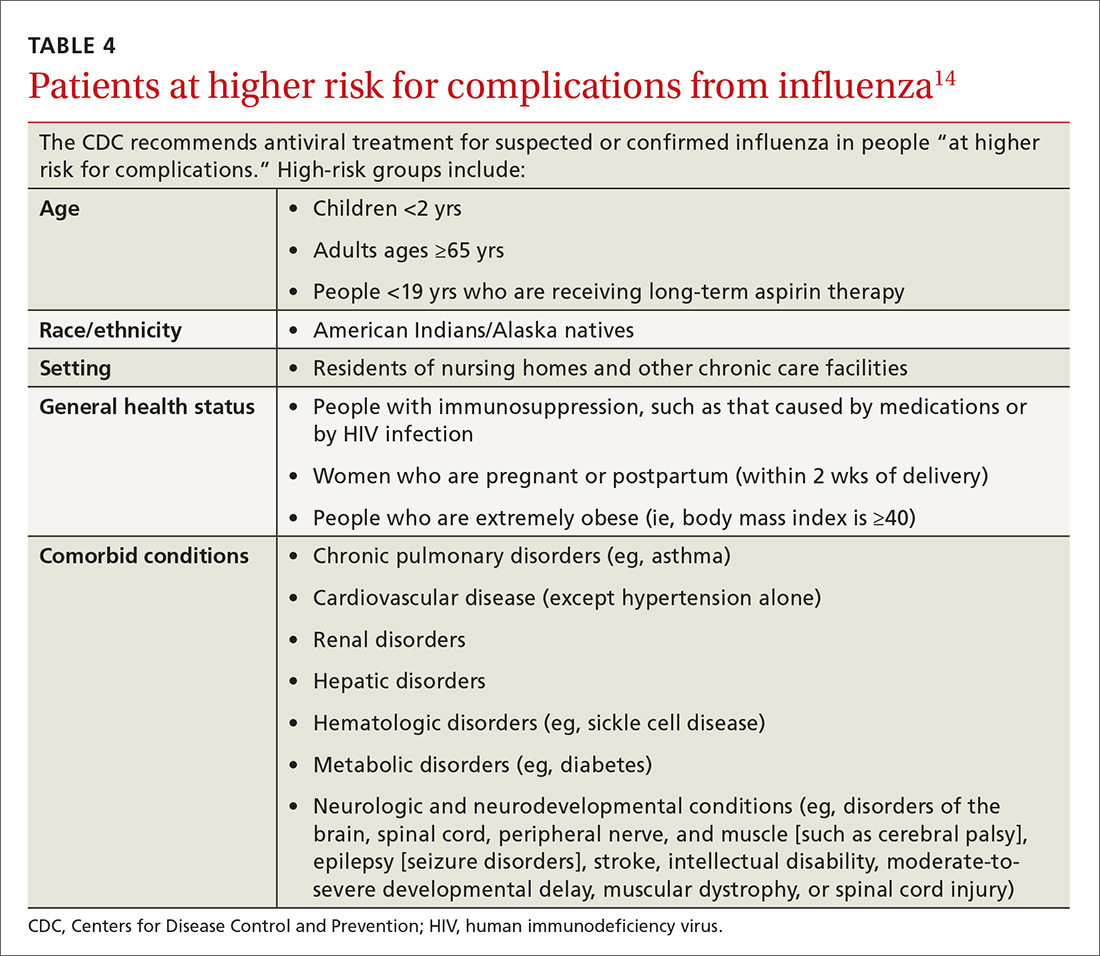

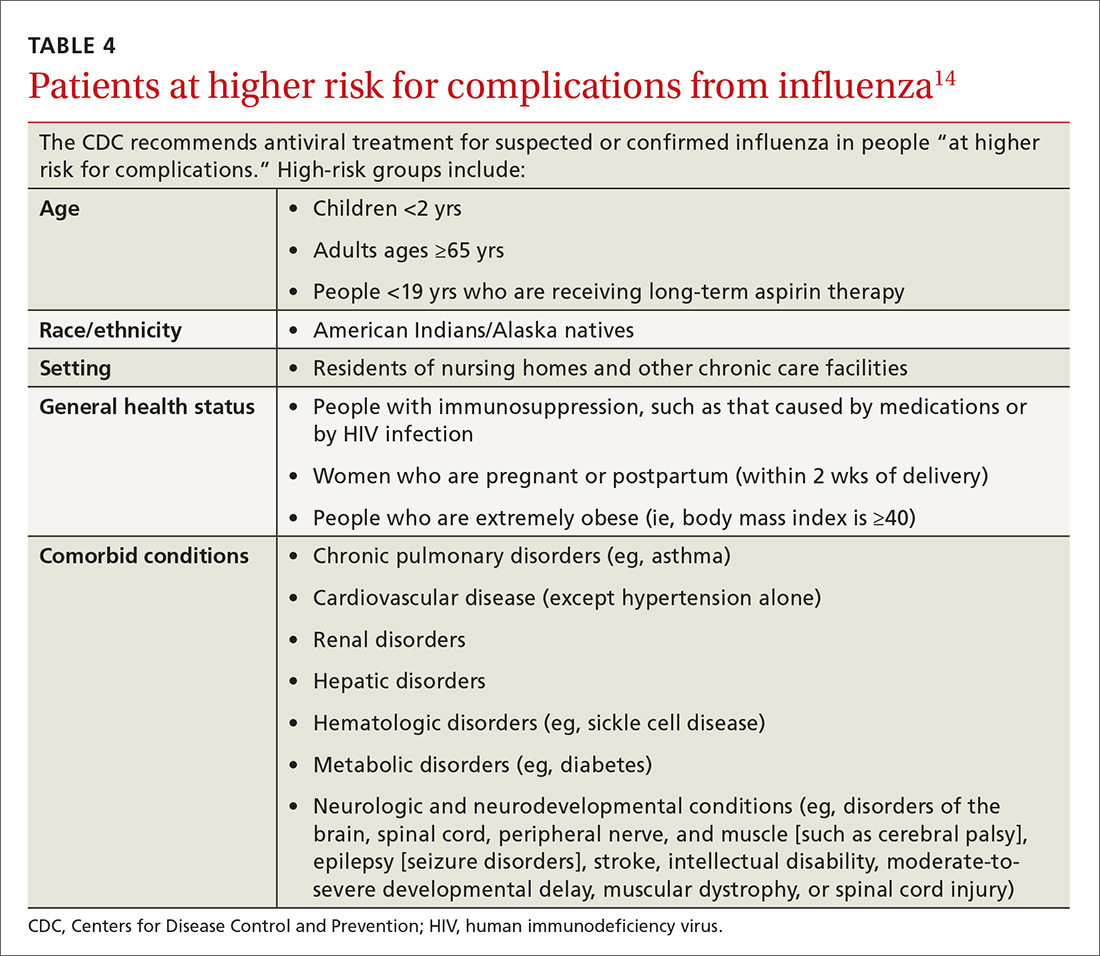

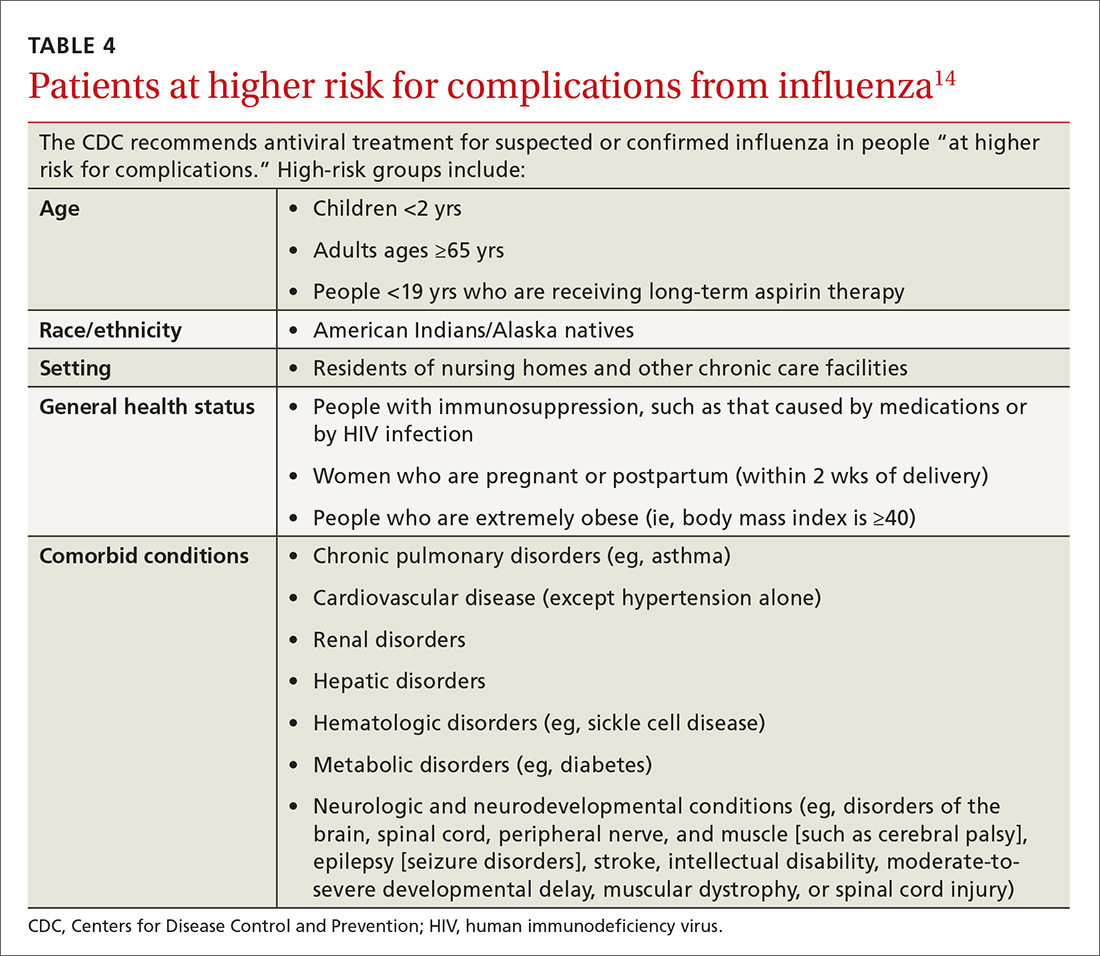

In the past, antivirals were used only in high-risk patients, such as children younger than 2 years, adults older than 65 years, and those with chronic health conditions.14 Now, antivirals are recommended for those who are at higher risk for complications (see Table 4), those with “severe, complicated, or progressive illness,” and hospitalized patients.14

Continue to: Antiviral treatment may have some value...

Antiviral treatment may have some value for hospitalized patients when started even 5 days after symptom onset. Treatment may be extended beyond the usual recommendations (5 days for oseltamivir or zanamivir) in immunosuppressed patients or the critically ill. Additionally, recent guidelines include consideration of antiviral treatment in outpatients who are at normal risk if treatment can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.14

The CDC currently recommends use of oseltamivir rather than other antivirals for most hospitalized patients, based on the availability of data on its use in this setting.14 Intravenous peramivir is recommended for patients who cannot tolerate or absorb oral medication; inhaled zanamivir or IV peramivir are preferred for patients with end-stage renal disease who are not undergoing dialysis (see Table 3).14

Strategy 2: Exercise caution when it comes to supportive care

There are other medications that may offer symptom relief or prevent complications, especially when antivirals are contraindicated or unavailable.

Corticosteroids are recommended as part of the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia,20 but their role in influenza is controversial. A 2016 Cochrane review21 found no randomized controlled trials on the topic. Although the balance of available data from observational studies indicated that use of corticosteroids was associated with increased mortality, the authors also noted that all the studies included in their meta-analysis were of “very low quality.” They concluded that “the use of steroids in influenza remains a clinical judgement call.”

Statins may be associated with improved outcomes in influenza and pneumonia. Studies thus far have given contradictory results,22,23 and a planned Cochrane review of the question has been withdrawn.24

Continue to: Over-the-counter medications...

Over-the-counter medications, such as aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen are often used to manage the fever and myalgia associated with influenza. Patients should be cautioned against using the same ingredient in multiple different branded medications. Acetaminophen, for example, is not limited to Tylenol-branded products. To avoid Reye’s syndrome, children and teens with febrile illness, such as influenza, should not use aspirin.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer L. Hamilton, MD, PhD, Drexel Family Medicine, 10 Shurs Lane, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19127; [email protected].

1. CDC. Weekly US influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Published June 8, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

2. CDC. Estimated influenza illnesses, medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths averted by vaccination in the United States. Published April 19, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/2015-16.htm. Accessed Setptember 18, 2018.

3. CDC. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2005-2018. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectiveness-studies.htm. Published February 15, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

4. Sah P, Medlock J, Fitzpatrick MC, et al. Optimizing the impact of low-efficacy influenza vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018:201802479.

5. Flannery B, Reynolds SB, Blanton L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against pediatric deaths: 2010-2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139: e20164244.

6. Kim DK, Riley LE, Hunter P. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:158–160.

7. Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:156–157.

8. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66:1-20.

9. CDC. Influenza vaccines—United States, 2017–18 influenza season. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

10. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Fry AM, et al. Update: ACIP recommendations for the use of quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4)—United States, 2018-19 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:643–645.

11. Jenco M. AAP: Give children IIV flu shot; use LAIV as last resort. AAP News. May 21, 2018. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/05/21/fluvaccine051818. Accessed August 22, 2018.

12. Glinka ER, Smith DM, Johns ST. Timing matters—influenza vaccination to HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2016;17:601-604.

13. Castilla J, Martínez-Baz I, Martínez-Artola V, et al. Decline in influenza vaccine effectiveness with time after vaccination, Navarre, Spain, season 2011/12. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20388.

14. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

15. CDC. Pneumococcal vaccination summary: who and when to vaccinate. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/who-when-to-vaccinate.html. Published February 28, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

16. Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006207.

17. Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, et al. Surgical mask vs N95 respirator for preventing influenza among health care workers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1865-1871.

18. Dobson J, Whitley RJ, Pocock S, Monto AS. Oseltamivir treatment for influenza in adults: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1729-1737.

19. Ghebrehewet S, MacPherson P, Ho A. Influenza. BMJ. 2016;355:i6258.

20. Kaysin A, Viera AJ. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:698-706.

21. Rodrigo C, Leonardi‐Bee J, Nguyen‐Van‐Tam J, et al. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD010406.

22. Brassard P, Wu JW, Ernst P, et al. The effect of statins on influenza-like illness morbidity and mortality. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:63-70.

23. Fedson DS. Treating influenza with statins and other immunomodulatory agents. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:417-435.

24. Khandaker G, Rashid H, Chow MY, et al. Statins for influenza and pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. January 9, 2017 [withdrawn].

Last year’s influenza season was severe enough that hospitals around the United States set up special evaluation areas beyond their emergency departments, at times spilling over to tents or other temporary structures in what otherwise would be parking lots. The scale and potential severity of the annual epidemic can be difficult to convey to our patients, who sometimes say “just the flu” to refer to an illness responsible for more than 170 pediatric deaths in the United States this past year.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently updated its 5-year estimates of influenza-related deaths in the United States; influenza mortality ranges from about 12,000 deaths in a mild season (such as 2011-2012) to 56,000 in a more severe season (eg, 2012-2013).2

Although influenza cannot be completely prevented, the following strategies can help reduce the risk for the illness and limit its severity if contracted.

Prevention

Strategy 1: Vaccinate against influenza

While the efficacy of vaccines varies from year to year, vaccination remains the core of influenza prevention efforts. In this decade, vaccine effectiveness has ranged from 19% to 60%.3 However, models suggest that even when the vaccine is only 20% effective, vaccinating 140 million people (the average number of doses delivered annually in the United States over the past 5 seasons) prevents 21 million infections, 130,000 hospitalizations, and more than 61,000 deaths.4 In a case-control study, Flannery et al found that vaccination was 65% effective in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated death in children over 4 seasons (July 2010 through June 2014).5

Deciding who should be vaccinated is simpler than in prior years: Rather than targeting people who are at higher risk (those ages 65 and older, or those with comorbidities), the current CDC recommendation is to vaccinate nearly everyone ages 6 months or older, with limited exceptions.6,7 (See Table 18).

Formulations. Many types of influenza vaccine are approved for use in the United States; these differ in the number of strains included (3 or 4), the amount of antigen present for each strain, the presence of an adjuvant, the growth medium used for the virus, and the route of administration (see Table 29). The relative merits of each type are a matter of some debate. There is ongoing research into the comparative efficacy of vaccines comprised of egg- vs cell-based cultures, as well as studies comparing high-dose or adjuvant vaccines to standard-dose inactivated vaccines.

Previously, the CDC has recommended preferential use (or avoidance) of some vaccine types, based on their efficacy. For the 2018-2019 flu season, however, the CDC has rescinded its recommendation against vaccine containing live attenuated virus (LAIV; FluMist brand) and expresses no preference for any vaccine formulation for patients of appropriate age and health status.10 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), however, is recommends that LAIV be used only if patients and their families decline injectable vaccines.11

Timing. Influenza vaccines are now distributed as early as July to some locations, raising concerns about waning immunity from early vaccination (July/August) if the influenza season does not peak until February or March.8,12,13 Currently, the CDC recommends balancing the possible benefit of delayed vaccination against the risks of missed opportunities to vaccinate, a possible early season, and logistical problems related to vaccinating the same number of people in a smaller time interval. Offering vaccination by the end of October, if possible, is recommended in order for immunity to develop by mid-November.8 Note: Children ages 6 months to 8 years will need to receive their initial vaccination in 2 half-doses administered at least 28 days apart; completing their vaccination by the end of October would require starting the process weeks earlier.

[polldaddy:10124269]

Continue to: Strategy 2

Strategy 2: Make use of chemoprophylaxis

Preventive use of antiviral medication (chemoprophylaxis) may be a useful adjunct or alternative to vaccination in certain circumstances: if the patient is at high risk for complications, has been exposed to someone with influenza, has contraindications to vaccination, or received the vaccine within the past 2 weeks. The CDC also suggests that chemoprophylaxis be considered for those with immune deficiencies or who are otherwise immunosuppressed after exposure.14 Antivirals can also be used to control outbreaks in long-term care facilities; in these cases, the recommendedregimen is daily administration for at least 2 weeks, continuing until at least 7 days after the identification of the last case.14 Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are the recommended prophylactic agents; a related intravenous medication, peramivir (Rapivab), is recommend for treatment only (see Table 314).

Strategy 3: Prevent comorbidities and opportunistic infections

Morbidity associated with influenza often comes from secondary infection. Pneumonia is among the most common complications, so influenza season is a good time to ensure that patients are appropriately vaccinated against pneumococcus, as well. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar or PCV13) is recommended for children younger than 2 years of age, to be administered in a series of 4 doses: at 2, 4, 6, and 12-15 months. Vaccination with PCV13 is also recommended for those ages 65 or older, to be followed at least one year later with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax or PPSV23).15 Additional doses of PCV13, PPSV23, or both may be indicated, depending on health status.

Strategy 4: Encourage good hygiene

The availability of immunizations and antivirals does not replace good hygiene. Frequent handwashing reduces the transmission of respiratory viruses, including influenza.16 Few studies have evaluated the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, but available evidence suggests they are effective in lowering viral transmission.16

Barriers, such as masks, gloves, and gowns, are helpful for health care workers.16 Surgical masks are often considered more comfortable to wear than N95 respirators. It may therefore be welcome news that when a 2009 randomized study assessed their use by hospital-based nurses, masks were non-inferior in protecting these health care workers against influenza.17

Presenteeism, the practice of going to work while sick, should be discouraged. People at risk for influenza may wish to avoid crowds during flu season; those with symptoms should be encouraged to stay home and limit contact with others.

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment

Strategy 1: Make prompt use of antivirals

Despite available preventive measures, tens of millions of people in the United States develop influenza every year. Use of antiviral medication, begun early in the course of illness, can reduce the duration of symptoms and may reduce the risk for complications.

The neuraminidase inhibitor (NI) group of antivirals—oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir—is effective against influenza types A and B and current resistance rates are low.

The adamantine family of antivirals, amantadine and rimantadine, treat type A only. Since the circulating influenza strains in the past several seasons have demonstrated resistance >99%, these medications are not currently recommended.14

NIs reduce the duration of influenza symptoms by 10% to 20%, shortening the illness by 6 to 24 hours.18,19 In otherwise healthy patients, this benefit must be balanced against the increased risk for nausea and vomiting (oseltamivir), bronchospasm and sinusitis (zanamivir), and diarrhea (peramivir). In adults, NIs reduce the risk for lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalization. A 2015 meta-analysis by Dobson et al found a relative risk for hospitalization among those prescribed oseltamivir vs placebo of 37%.18

In the past, antivirals were used only in high-risk patients, such as children younger than 2 years, adults older than 65 years, and those with chronic health conditions.14 Now, antivirals are recommended for those who are at higher risk for complications (see Table 4), those with “severe, complicated, or progressive illness,” and hospitalized patients.14

Continue to: Antiviral treatment may have some value...

Antiviral treatment may have some value for hospitalized patients when started even 5 days after symptom onset. Treatment may be extended beyond the usual recommendations (5 days for oseltamivir or zanamivir) in immunosuppressed patients or the critically ill. Additionally, recent guidelines include consideration of antiviral treatment in outpatients who are at normal risk if treatment can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.14

The CDC currently recommends use of oseltamivir rather than other antivirals for most hospitalized patients, based on the availability of data on its use in this setting.14 Intravenous peramivir is recommended for patients who cannot tolerate or absorb oral medication; inhaled zanamivir or IV peramivir are preferred for patients with end-stage renal disease who are not undergoing dialysis (see Table 3).14

Strategy 2: Exercise caution when it comes to supportive care

There are other medications that may offer symptom relief or prevent complications, especially when antivirals are contraindicated or unavailable.

Corticosteroids are recommended as part of the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia,20 but their role in influenza is controversial. A 2016 Cochrane review21 found no randomized controlled trials on the topic. Although the balance of available data from observational studies indicated that use of corticosteroids was associated with increased mortality, the authors also noted that all the studies included in their meta-analysis were of “very low quality.” They concluded that “the use of steroids in influenza remains a clinical judgement call.”

Statins may be associated with improved outcomes in influenza and pneumonia. Studies thus far have given contradictory results,22,23 and a planned Cochrane review of the question has been withdrawn.24

Continue to: Over-the-counter medications...

Over-the-counter medications, such as aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen are often used to manage the fever and myalgia associated with influenza. Patients should be cautioned against using the same ingredient in multiple different branded medications. Acetaminophen, for example, is not limited to Tylenol-branded products. To avoid Reye’s syndrome, children and teens with febrile illness, such as influenza, should not use aspirin.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer L. Hamilton, MD, PhD, Drexel Family Medicine, 10 Shurs Lane, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19127; [email protected].

Last year’s influenza season was severe enough that hospitals around the United States set up special evaluation areas beyond their emergency departments, at times spilling over to tents or other temporary structures in what otherwise would be parking lots. The scale and potential severity of the annual epidemic can be difficult to convey to our patients, who sometimes say “just the flu” to refer to an illness responsible for more than 170 pediatric deaths in the United States this past year.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently updated its 5-year estimates of influenza-related deaths in the United States; influenza mortality ranges from about 12,000 deaths in a mild season (such as 2011-2012) to 56,000 in a more severe season (eg, 2012-2013).2

Although influenza cannot be completely prevented, the following strategies can help reduce the risk for the illness and limit its severity if contracted.

Prevention

Strategy 1: Vaccinate against influenza

While the efficacy of vaccines varies from year to year, vaccination remains the core of influenza prevention efforts. In this decade, vaccine effectiveness has ranged from 19% to 60%.3 However, models suggest that even when the vaccine is only 20% effective, vaccinating 140 million people (the average number of doses delivered annually in the United States over the past 5 seasons) prevents 21 million infections, 130,000 hospitalizations, and more than 61,000 deaths.4 In a case-control study, Flannery et al found that vaccination was 65% effective in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated death in children over 4 seasons (July 2010 through June 2014).5

Deciding who should be vaccinated is simpler than in prior years: Rather than targeting people who are at higher risk (those ages 65 and older, or those with comorbidities), the current CDC recommendation is to vaccinate nearly everyone ages 6 months or older, with limited exceptions.6,7 (See Table 18).

Formulations. Many types of influenza vaccine are approved for use in the United States; these differ in the number of strains included (3 or 4), the amount of antigen present for each strain, the presence of an adjuvant, the growth medium used for the virus, and the route of administration (see Table 29). The relative merits of each type are a matter of some debate. There is ongoing research into the comparative efficacy of vaccines comprised of egg- vs cell-based cultures, as well as studies comparing high-dose or adjuvant vaccines to standard-dose inactivated vaccines.

Previously, the CDC has recommended preferential use (or avoidance) of some vaccine types, based on their efficacy. For the 2018-2019 flu season, however, the CDC has rescinded its recommendation against vaccine containing live attenuated virus (LAIV; FluMist brand) and expresses no preference for any vaccine formulation for patients of appropriate age and health status.10 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), however, is recommends that LAIV be used only if patients and their families decline injectable vaccines.11

Timing. Influenza vaccines are now distributed as early as July to some locations, raising concerns about waning immunity from early vaccination (July/August) if the influenza season does not peak until February or March.8,12,13 Currently, the CDC recommends balancing the possible benefit of delayed vaccination against the risks of missed opportunities to vaccinate, a possible early season, and logistical problems related to vaccinating the same number of people in a smaller time interval. Offering vaccination by the end of October, if possible, is recommended in order for immunity to develop by mid-November.8 Note: Children ages 6 months to 8 years will need to receive their initial vaccination in 2 half-doses administered at least 28 days apart; completing their vaccination by the end of October would require starting the process weeks earlier.

[polldaddy:10124269]

Continue to: Strategy 2

Strategy 2: Make use of chemoprophylaxis

Preventive use of antiviral medication (chemoprophylaxis) may be a useful adjunct or alternative to vaccination in certain circumstances: if the patient is at high risk for complications, has been exposed to someone with influenza, has contraindications to vaccination, or received the vaccine within the past 2 weeks. The CDC also suggests that chemoprophylaxis be considered for those with immune deficiencies or who are otherwise immunosuppressed after exposure.14 Antivirals can also be used to control outbreaks in long-term care facilities; in these cases, the recommendedregimen is daily administration for at least 2 weeks, continuing until at least 7 days after the identification of the last case.14 Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are the recommended prophylactic agents; a related intravenous medication, peramivir (Rapivab), is recommend for treatment only (see Table 314).

Strategy 3: Prevent comorbidities and opportunistic infections

Morbidity associated with influenza often comes from secondary infection. Pneumonia is among the most common complications, so influenza season is a good time to ensure that patients are appropriately vaccinated against pneumococcus, as well. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar or PCV13) is recommended for children younger than 2 years of age, to be administered in a series of 4 doses: at 2, 4, 6, and 12-15 months. Vaccination with PCV13 is also recommended for those ages 65 or older, to be followed at least one year later with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax or PPSV23).15 Additional doses of PCV13, PPSV23, or both may be indicated, depending on health status.

Strategy 4: Encourage good hygiene

The availability of immunizations and antivirals does not replace good hygiene. Frequent handwashing reduces the transmission of respiratory viruses, including influenza.16 Few studies have evaluated the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, but available evidence suggests they are effective in lowering viral transmission.16

Barriers, such as masks, gloves, and gowns, are helpful for health care workers.16 Surgical masks are often considered more comfortable to wear than N95 respirators. It may therefore be welcome news that when a 2009 randomized study assessed their use by hospital-based nurses, masks were non-inferior in protecting these health care workers against influenza.17

Presenteeism, the practice of going to work while sick, should be discouraged. People at risk for influenza may wish to avoid crowds during flu season; those with symptoms should be encouraged to stay home and limit contact with others.

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment

Strategy 1: Make prompt use of antivirals

Despite available preventive measures, tens of millions of people in the United States develop influenza every year. Use of antiviral medication, begun early in the course of illness, can reduce the duration of symptoms and may reduce the risk for complications.

The neuraminidase inhibitor (NI) group of antivirals—oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir—is effective against influenza types A and B and current resistance rates are low.

The adamantine family of antivirals, amantadine and rimantadine, treat type A only. Since the circulating influenza strains in the past several seasons have demonstrated resistance >99%, these medications are not currently recommended.14

NIs reduce the duration of influenza symptoms by 10% to 20%, shortening the illness by 6 to 24 hours.18,19 In otherwise healthy patients, this benefit must be balanced against the increased risk for nausea and vomiting (oseltamivir), bronchospasm and sinusitis (zanamivir), and diarrhea (peramivir). In adults, NIs reduce the risk for lower respiratory tract complications and hospitalization. A 2015 meta-analysis by Dobson et al found a relative risk for hospitalization among those prescribed oseltamivir vs placebo of 37%.18

In the past, antivirals were used only in high-risk patients, such as children younger than 2 years, adults older than 65 years, and those with chronic health conditions.14 Now, antivirals are recommended for those who are at higher risk for complications (see Table 4), those with “severe, complicated, or progressive illness,” and hospitalized patients.14

Continue to: Antiviral treatment may have some value...

Antiviral treatment may have some value for hospitalized patients when started even 5 days after symptom onset. Treatment may be extended beyond the usual recommendations (5 days for oseltamivir or zanamivir) in immunosuppressed patients or the critically ill. Additionally, recent guidelines include consideration of antiviral treatment in outpatients who are at normal risk if treatment can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.14

The CDC currently recommends use of oseltamivir rather than other antivirals for most hospitalized patients, based on the availability of data on its use in this setting.14 Intravenous peramivir is recommended for patients who cannot tolerate or absorb oral medication; inhaled zanamivir or IV peramivir are preferred for patients with end-stage renal disease who are not undergoing dialysis (see Table 3).14

Strategy 2: Exercise caution when it comes to supportive care

There are other medications that may offer symptom relief or prevent complications, especially when antivirals are contraindicated or unavailable.

Corticosteroids are recommended as part of the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia,20 but their role in influenza is controversial. A 2016 Cochrane review21 found no randomized controlled trials on the topic. Although the balance of available data from observational studies indicated that use of corticosteroids was associated with increased mortality, the authors also noted that all the studies included in their meta-analysis were of “very low quality.” They concluded that “the use of steroids in influenza remains a clinical judgement call.”

Statins may be associated with improved outcomes in influenza and pneumonia. Studies thus far have given contradictory results,22,23 and a planned Cochrane review of the question has been withdrawn.24

Continue to: Over-the-counter medications...

Over-the-counter medications, such as aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen are often used to manage the fever and myalgia associated with influenza. Patients should be cautioned against using the same ingredient in multiple different branded medications. Acetaminophen, for example, is not limited to Tylenol-branded products. To avoid Reye’s syndrome, children and teens with febrile illness, such as influenza, should not use aspirin.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jennifer L. Hamilton, MD, PhD, Drexel Family Medicine, 10 Shurs Lane, Suite 301, Philadelphia, PA 19127; [email protected].

1. CDC. Weekly US influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Published June 8, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

2. CDC. Estimated influenza illnesses, medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths averted by vaccination in the United States. Published April 19, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/2015-16.htm. Accessed Setptember 18, 2018.

3. CDC. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2005-2018. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectiveness-studies.htm. Published February 15, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

4. Sah P, Medlock J, Fitzpatrick MC, et al. Optimizing the impact of low-efficacy influenza vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018:201802479.

5. Flannery B, Reynolds SB, Blanton L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against pediatric deaths: 2010-2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139: e20164244.

6. Kim DK, Riley LE, Hunter P. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:158–160.

7. Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:156–157.

8. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66:1-20.

9. CDC. Influenza vaccines—United States, 2017–18 influenza season. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

10. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Fry AM, et al. Update: ACIP recommendations for the use of quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4)—United States, 2018-19 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:643–645.

11. Jenco M. AAP: Give children IIV flu shot; use LAIV as last resort. AAP News. May 21, 2018. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/05/21/fluvaccine051818. Accessed August 22, 2018.

12. Glinka ER, Smith DM, Johns ST. Timing matters—influenza vaccination to HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2016;17:601-604.

13. Castilla J, Martínez-Baz I, Martínez-Artola V, et al. Decline in influenza vaccine effectiveness with time after vaccination, Navarre, Spain, season 2011/12. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20388.

14. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

15. CDC. Pneumococcal vaccination summary: who and when to vaccinate. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/who-when-to-vaccinate.html. Published February 28, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

16. Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006207.

17. Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, et al. Surgical mask vs N95 respirator for preventing influenza among health care workers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1865-1871.

18. Dobson J, Whitley RJ, Pocock S, Monto AS. Oseltamivir treatment for influenza in adults: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1729-1737.

19. Ghebrehewet S, MacPherson P, Ho A. Influenza. BMJ. 2016;355:i6258.

20. Kaysin A, Viera AJ. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:698-706.

21. Rodrigo C, Leonardi‐Bee J, Nguyen‐Van‐Tam J, et al. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD010406.

22. Brassard P, Wu JW, Ernst P, et al. The effect of statins on influenza-like illness morbidity and mortality. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:63-70.

23. Fedson DS. Treating influenza with statins and other immunomodulatory agents. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:417-435.

24. Khandaker G, Rashid H, Chow MY, et al. Statins for influenza and pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. January 9, 2017 [withdrawn].

1. CDC. Weekly US influenza surveillance report. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm. Published June 8, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

2. CDC. Estimated influenza illnesses, medical visits, hospitalizations, and deaths averted by vaccination in the United States. Published April 19, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/disease/2015-16.htm. Accessed Setptember 18, 2018.

3. CDC. Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness, 2005-2018. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/vaccination/effectiveness-studies.htm. Published February 15, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

4. Sah P, Medlock J, Fitzpatrick MC, et al. Optimizing the impact of low-efficacy influenza vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018:201802479.

5. Flannery B, Reynolds SB, Blanton L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against pediatric deaths: 2010-2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139: e20164244.

6. Kim DK, Riley LE, Hunter P. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:158–160.

7. Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, et al. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended immunization schedule for children and adolescents aged 18 years or younger—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:156–157.

8. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2017-18 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017;66:1-20.

9. CDC. Influenza vaccines—United States, 2017–18 influenza season. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/vaccine/vaccines.htm. Published May 16, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

10. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Fry AM, et al. Update: ACIP recommendations for the use of quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4)—United States, 2018-19 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:643–645.

11. Jenco M. AAP: Give children IIV flu shot; use LAIV as last resort. AAP News. May 21, 2018. http://www.aappublications.org/news/2018/05/21/fluvaccine051818. Accessed August 22, 2018.

12. Glinka ER, Smith DM, Johns ST. Timing matters—influenza vaccination to HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2016;17:601-604.

13. Castilla J, Martínez-Baz I, Martínez-Artola V, et al. Decline in influenza vaccine effectiveness with time after vaccination, Navarre, Spain, season 2011/12. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20388.

14. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Published May 11, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

15. CDC. Pneumococcal vaccination summary: who and when to vaccinate. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/who-when-to-vaccinate.html. Published February 28, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

16. Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006207.

17. Loeb M, Dafoe N, Mahony J, et al. Surgical mask vs N95 respirator for preventing influenza among health care workers: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1865-1871.

18. Dobson J, Whitley RJ, Pocock S, Monto AS. Oseltamivir treatment for influenza in adults: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1729-1737.

19. Ghebrehewet S, MacPherson P, Ho A. Influenza. BMJ. 2016;355:i6258.

20. Kaysin A, Viera AJ. Community-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:698-706.

21. Rodrigo C, Leonardi‐Bee J, Nguyen‐Van‐Tam J, et al. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD010406.

22. Brassard P, Wu JW, Ernst P, et al. The effect of statins on influenza-like illness morbidity and mortality. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:63-70.

23. Fedson DS. Treating influenza with statins and other immunomodulatory agents. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:417-435.

24. Khandaker G, Rashid H, Chow MY, et al. Statins for influenza and pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. January 9, 2017 [withdrawn].

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend influenza vaccination for all patients at least 6 months old unless a specific contraindication exists. A

› Recommend pneumococcal vaccination to appropriate patients to reduce the risk for a common complication of influenza. A

› Encourage hygiene-based measures to limit infection, including frequent handwashing or use of a hand sanitizer. B

› Prescribe oseltamivir to hospitalized influenza patients to limit the duration and severity of infection. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Trials need standardized reporting of pediatric fever after flu vaccine

Researchers found a lower rate of pediatric fever after applying a standard definition of fever across three different clinical trials of pediatric patients receiving influenza vaccinations, according to research published in the Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal.

Investigators in future studies must adopt a standardized definition of pediatric fever after an influenza vaccination. “Our study demonstrates the variability in results which occur due to minor differences in the definition of fever, methods of analysis and reporting of results,” Jean Li-Kim-Moy, MBBS, of the University of Sydney, and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Li-Kim-Moy and colleagues analyzed pediatric datasets from three different clinical trials using trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV); the primary trial included 3,317 children aged 6-35 months who were randomized to receive Fluarix at 0.25 mL or 0.5 mL, or receive 0.25 mL of Fluzone. The other two trials studied children receiving TIV between 6 months–17 years and 3-17 years. The researchers also performed a multivariable regression analysis to determine the relationship between immunogenicity, antipyretic use, and postvaccination fever.

The primary study initially reported the fever rate 0 days–3 days after vaccination was between 6% and 7%. After reporting the rate of fever separately for each dose and changing the criteria to “defining fever as greater than or equal to 38.0°C by any route of measurement” for the primary study, the researchers found a rate of any-cause fever was 3%-4% for the first dose and 4%-5% for the second dose. The rate of vaccine-related fever in the primary study was 3% for the first dose and 3%-4% for the second dose, with researchers noting vaccine-related fever occurred significantly earlier compared with any-cause fever (mean 1 days vs. 2 days after vaccination; P equals .04).

Impact of fever, antipyretics

The researchers also performed a pooled immunogenicity analysis of 5,902 children from all three trials and found a strong association between fever after vaccination and increased geometric mean titer (GMT) ratios (1.21-1.39; P less than or equal to .01) and an association between antipyretic use and reduced GMT ratios (0.80-0.87; P less than .0006).