User login

Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines

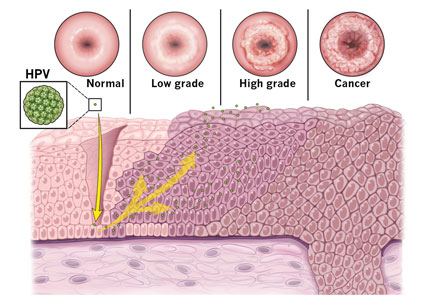

About 12% of women worldwide are infected with human papillomavirus (HPV).1 Persistent HPV infection with high-risk strains such as HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 cause nearly all cases of cervical cancer and some anal, vaginal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.2 An estimated 13,000 cases of invasive cervical cancer will be diagnosed this year in the United States alone.3

Up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. A number of changes have been made to the vaccination schedule within the past few years—patients younger than 15 need only 2 rather than 3 doses, and the vaccine itself can be used in adults up to age 45.

Vaccination and routine cervical cancer screening are both necessary to prevent this disease3 along with effective family and patient counseling. Here, we discuss the most up-to-date HPV vaccination recommendations, current cervical cancer screening guidelines, counseling techniques that increase vaccination acceptance rates, and follow-up protocols for abnormal cervical cancer screening results.

TYPES OF HPV VACCINES

HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts.4 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 HPV vaccines:

- Gardasil 9 targets HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 along with 31, 33, 45, 52, 58—these cause 90% of cervical cancer cases and most cases of genital warts5—making it the most effective vaccine available; Gardasil 9 is the only HPV vaccine currently available in the United States

- The bivalent vaccine (Cervarix) targeted HPV 16 and 18 only, and was discontinued in the United States in 2016

- The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil) targeted HPV 16 and 18 as well as 6 and 11, which cause most cases of genital warts; the last available doses in the United States expired in May 2017; it has been replaced by Gardasil 9.

The incidence of cervical cancer in the United States dropped 29% among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 when HPV vaccination first started to 2011–2014.6

VACCINE DOSING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

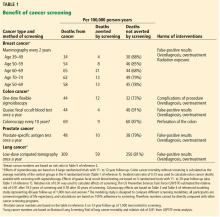

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) revised its HPV vaccine schedule in 2016, when it decreased the necessary doses from 3 to 2 for patients under age 15 and addressed the needs of special patient populations.7 In late 2018, the FDA approved the use of the vaccine in men and women up to age 45. However, no change in guidelines have yet been made (Table 1).

In females, the ACIP recommends starting HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12, but it can be given as early as age 9. A 2-dose schedule is recommended for the 9-valent vaccine before the patient’s 15th birthday (the second dose 6 to 12 months after the first).7 For females who initiate HPV vaccination between ages 15 and 45, a 3-dose schedule is necessary (at 0, 1 to 2, and 6 months).7,8

The change to a 2-dose schedule was prompted by an evaluation of girls ages 9 to 13 randomized to receive either a 2- or 3-dose schedule. Antibody responses with a 2-dose schedule were not inferior to those of young women (ages 16 to 26) who received all 3 doses.9 The geometric mean titer ratios remained noninferior throughout the study period of 36 months.

However, a loss of noninferiority was noted for HPV-18 by 24 months and for HPV-6 by 36 months.9 Thus, further studies are needed to understand the duration of protection with a 2-dose schedule. Nevertheless, decreasing the number of doses makes it a more convenient and cost-effective option for many families.

The recommendations are the same for males except for one notable difference: in males ages 21 to 26, vaccination is not routinely recommended by the ACIP, but rather it is considered a “permissive use” recommendation: ie, the vaccine should be offered and final decisions on administration be made after individualized discussion with the patient.10 Permissive-use status also means the vaccine may not be covered by health insurance. Even though the vaccine is now available to men and women until age 45, many insurance plans do not cover it after age 26.

Children of either sex with a history of sexual abuse should receive their first vaccine dose beginning at age 9.7

Immunocompromised patients should follow the 3-dose schedule regardless of their sex or the age when vaccination was initiated.10

For transgender patients and for men not previously vaccinated who have sex with men, the 3-dose schedule vaccine should be given by the age of 26 (this is a routine recommendation, not a permissive one).8

CHALLENGES OF VACCINATION

Effective patient and family counseling is important. Even though the first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, only 34.9% of US adolescents were fully vaccinated by 2015. This was in part because providers did not recommend it, were unfamiliar with it, or had concerns about its safety,11,12 and in part because some parents refused it.

The physician must address any myths regarding HPV vaccination and ensure that parents and patients understand that HPV vaccine is safe and effective. Studies have shown that with high-quality recommendations (ie, the care provider strongly endorses the HPV vaccine, encourages same-day vaccination, and discusses cancer prevention), patients are 9 times more likely to start the HPV vaccination schedule and 3 times more likely to follow through with subsequent doses.13

Providing good family and patient education does not necessarily require spending more counseling time. A recent study showed that spending less time discussing the HPV vaccine can lead to better vaccine coverage.14 The study compared parent HPV vaccine counseling techniques and found that simply informing patients and their families that the HPV vaccine was due was associated with a higher vaccine acceptance rate than inviting conversations about it.14 When providers announced that the vaccine was due, assuming the parents were ready to vaccinate, there was a 5.4% increase in HPV vaccination coverage.14

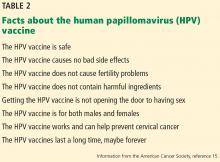

Conversely, physicians who engaged parents in open-ended discussions about the HPV vaccine did not improve HPV vaccination coverage.14 The authors suggested that providers approach HPV vaccination as if they were counseling patients and families about the need to avoid second-hand smoke or the need to use car seats. If parents or patients resist the presumptive announcement approach, expanded counseling and shared decision-making are appropriate. This includes addressing misconceptions that parents and patients may have about the HPV vaccine. The American Cancer Society lists 8 facts to reference (Table 2).15

SECONDARY PREVENTION: CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Since the introduction of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test, US cervical cancer incidence rates have decreased by more than 60%.16 Because almost all cervical cancer is preventable with proper screening, all women ages 21 to 65 should be screened.

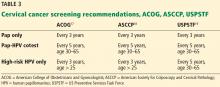

Currently, there are 3 options available for cervical cancer screening: the Pap-only test, the Pap-HPV cotest, and the high-risk HPV-only test (Table 3). The latter 2 options detect high-risk HPV genotypes.

Several organizations have screening algorithms that recommend when to use these tests, but the 3 that shape today’s standard of care in cervical cancer screening come from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17–19

Pap-only testing is performed every 3 years to screen for cervical neoplasia that might indicate premalignancy.

Pap-HPV cotesting is performed every 5 years in women older than 30 with past normal screening. Until 2018, all 3 organizations recommended cotesting as the preferred screening algorithm for women ages 30 to 65.17–19 Patients with a history of abnormal test results require more frequent testing as recommended by the ASCCP.18

The high-risk HPV-only test utilizes real-time polymerase chain reaction to detect HPV 16, HPV 18, and 12 other HPV genotypes. Only 2 tests are approved by the FDA as stand-alone cervical cancer screening tests—the Roche Cobas HPV test approved in 2014 and the Becton Dickinson Onclarity HPV assay approved in 2018. Other HPV tests that are used in a cotesting strategy should not be used for high-risk HPV-only testing because their performance characteristics may differ.

In 2015, the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) study showed that 1 round of high-risk HPV-only screening for women older than 25 was more sensitive than Pap-only or cotesting for stage 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or more severe disease (after 3 years of follow-up).20 Current guidelines from ASCCP18 and ACOG17 state that the high-risk HPV test can be repeated every 3 years (when used to screen by itself) if the woman is older than 25 and has had a normal test result.

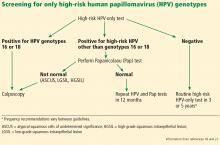

If the HPV test result is positive for high-risk HPV 16 or 18 genotypes, then immediate colposcopy is indicated; women who test positive for one of the other 12 high-risk subtypes will need to undergo a Pap test to determine the appropriate follow-up (Figure 1).18,21

In 2018, the USPSTF updated its recommendations, noting that for women age 30 to 65, Pap-only testing every 3 years, cotesting every 5 years, or high-risk HPV-only testing every 5 years are all appropriate screening strategies, with the Pap-only or high-risk HPV-only screenings being preferred.19 This is in contrast to ACOG and ASCCP recommendations for cotesting every 5 years, with alternative options of Pap-only or HPV-only testing being done every 3 years.17,18

Is there a best screening protocol?

The USPSTF reviewed large randomized and observational studies to summarize the effectiveness of the 3 screening strategies and commissioned a decision analysis model to compare the risks, benefits, and costs of the 3 screening algorithms. The guideline statement notes both cotesting and high-risk HPV testing offer similar cancer detection rates: each prevents 1 additional cancer per 1,000 women screened as opposed to Pap-only testing.19

Also, tests that incorporate high-risk HPV screening may offer better detection of cervical adenocarcinoma (which has a worse prognosis than the more common squamous cell carcinoma type). However, both HPV-based screening strategies are more likely to require additional colposcopies for follow-up than Pap-only screening (1,630 colposcopies required for each cancer prevented with high-risk HPV alone, 1,635 with cotesting). Colposcopy is a simple office procedure that causes minimal discomfort to the patient.

The USPSTF guideline also differs in the recommended frequency of high-risk HPV-only testing; a high-risk HPV result should be repeated every 5 years if normal (as opposed to every 3 years as recommended by ACOG and ASCCP).19 The 5-year recommendation is based on analysis modeling, which suggests that performing high-risk HPV-only testing more frequently is unlikely to improve detection rates but will increase the number of screening tests and colposcopies.19

No trial has directly compared cotesting with high-risk HPV testing for more than 2 rounds of screening. The updated USPSTF recommendations are based on modeling estimates and expert opinion, which assesses cost and benefit vs harm in the long term. Also, no high-risk HPV test is currently FDA-approved for every-5-year screening when used by itself.

All 3 cervical cancer screening methods provide highly effective cancer prevention, so it is important for providers to choose the strategy that best fits their practice. The most critical aspect of screening is getting all women screened, no matter which method is used.

It is critical to remember that the screening intervals are intended for patients without symptoms. Those who have new concerns such as bleeding should have a diagnostic Pap done to evaluate their symptoms.

Follow-up of abnormal results

Regardless of the pathway chosen, appropriate follow-up of any abnormal test result is critical to the early detection of cancer. Established follow-up guidelines exist,22,23 but accessing this information can be difficult for the busy clinician. The ASCCP has a mobile phone application that outlines the action steps corresponding to the patient’s age and results of any combination of Pap or HPV testing. The app also includes the best screening algorithms for a particular patient.24

All guidelines agree that cervical cancer screening should start at age 21, regardless of HPV vaccination status or age of sexual initiation.17,18,25 Screening can be discontinued at age 65 for women with normal screening results in the prior decade (3 consecutive negative Pap results or 2 consecutive negative cotest results).23

For women who have had a total hysterectomy and no history of cervical neoplasia, screening should be stopped immediately after the procedure. However, several high-risk groups of women will need continued screening past the age of 65, or after a hysterectomy.

For a woman with a history of stage 2 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or higher grade lesions, routine screening is continued for an additional 20 years, even if she is over age 65. Pap-only testing every 3 years is acceptable, because the role of HPV testing is unclear after hysterectomy.23 Prior guidelines suggested annual screening in these patients, so the change to every 3 years is notable. Many gynecologic oncologists will recommend that women with a history of cervical cancer continue annual screening indefinitely.

Within the first 2 to 3 years after treatment for high-grade dysplastic changes, annual follow-up is done by the gynecologic oncology team. Providers who offer follow-up during this time frame should keep in communication with the oncology team to ensure appropriate, individualized care. These recommendations are based on expert opinion, so variations in clinical practice may be seen.

Women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus can have Pap-only testing every 3 years, after a series of 3 normal annual Pap results.26 But screening does not stop at age 65.23,26 For patients who are immunosuppressed or have a history of diethylstilbestrol exposure, screening should be done annually indefinitely.23

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010; 202(12):1789–1799. doi:10.1086/657321

- de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(6):607–615. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for cervical cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JME, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(49):1405–1408. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Supplemental information and guidance for vaccination providers regarding use of 9-valent HPV vaccine Information for persons who started an HPV vaccination series with quadrivalent or bivalent HPV vaccine. www.cdc.gov/hpv/downloads/9vhpv-guidance.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309(17):1793–1802. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1625

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR-05):1–30. pmid:25167164

- Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, Kadono M, Daley EM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: what are the reasons for nonvaccination among US adolescents? J Adolesc Health 2017; 61(3):288–293. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.015

- Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(33):850–858. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a4

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine 2016; 34(9):1187–1192. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2017; 139(1):e20161764. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764

- American Cancer Society. HPV vaccine facts. www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/infectious-agents/hpv/hpv-vaccine-facts-and-fears.html. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- National Cancer Institute; Chasan R, Manrow R. Cervical cancer. https://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/viewfactsheet.aspx?csid=76. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Frequently asked questions. Cervical cancer screening. www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Cervical-Cancer-Screening. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 2012; 137(4):516–542. doi:10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018; 320(7):674–686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 136(2):189–197. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.076

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125(2):330–337. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121(4):829–846. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128(4):e111–e130. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708

- ASCCP. Mobile app. http://www.asccp.org/store-detail2/asccp-mobile-app. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- USPSTF. Draft recommendation: cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Masur H, Brooks JT, Benson CA, Holmes KK, Pau AK, Kaplan JE; National Institutes of Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(9):1308–1311. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu094

About 12% of women worldwide are infected with human papillomavirus (HPV).1 Persistent HPV infection with high-risk strains such as HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 cause nearly all cases of cervical cancer and some anal, vaginal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.2 An estimated 13,000 cases of invasive cervical cancer will be diagnosed this year in the United States alone.3

Up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. A number of changes have been made to the vaccination schedule within the past few years—patients younger than 15 need only 2 rather than 3 doses, and the vaccine itself can be used in adults up to age 45.

Vaccination and routine cervical cancer screening are both necessary to prevent this disease3 along with effective family and patient counseling. Here, we discuss the most up-to-date HPV vaccination recommendations, current cervical cancer screening guidelines, counseling techniques that increase vaccination acceptance rates, and follow-up protocols for abnormal cervical cancer screening results.

TYPES OF HPV VACCINES

HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts.4 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 HPV vaccines:

- Gardasil 9 targets HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 along with 31, 33, 45, 52, 58—these cause 90% of cervical cancer cases and most cases of genital warts5—making it the most effective vaccine available; Gardasil 9 is the only HPV vaccine currently available in the United States

- The bivalent vaccine (Cervarix) targeted HPV 16 and 18 only, and was discontinued in the United States in 2016

- The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil) targeted HPV 16 and 18 as well as 6 and 11, which cause most cases of genital warts; the last available doses in the United States expired in May 2017; it has been replaced by Gardasil 9.

The incidence of cervical cancer in the United States dropped 29% among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 when HPV vaccination first started to 2011–2014.6

VACCINE DOSING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) revised its HPV vaccine schedule in 2016, when it decreased the necessary doses from 3 to 2 for patients under age 15 and addressed the needs of special patient populations.7 In late 2018, the FDA approved the use of the vaccine in men and women up to age 45. However, no change in guidelines have yet been made (Table 1).

In females, the ACIP recommends starting HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12, but it can be given as early as age 9. A 2-dose schedule is recommended for the 9-valent vaccine before the patient’s 15th birthday (the second dose 6 to 12 months after the first).7 For females who initiate HPV vaccination between ages 15 and 45, a 3-dose schedule is necessary (at 0, 1 to 2, and 6 months).7,8

The change to a 2-dose schedule was prompted by an evaluation of girls ages 9 to 13 randomized to receive either a 2- or 3-dose schedule. Antibody responses with a 2-dose schedule were not inferior to those of young women (ages 16 to 26) who received all 3 doses.9 The geometric mean titer ratios remained noninferior throughout the study period of 36 months.

However, a loss of noninferiority was noted for HPV-18 by 24 months and for HPV-6 by 36 months.9 Thus, further studies are needed to understand the duration of protection with a 2-dose schedule. Nevertheless, decreasing the number of doses makes it a more convenient and cost-effective option for many families.

The recommendations are the same for males except for one notable difference: in males ages 21 to 26, vaccination is not routinely recommended by the ACIP, but rather it is considered a “permissive use” recommendation: ie, the vaccine should be offered and final decisions on administration be made after individualized discussion with the patient.10 Permissive-use status also means the vaccine may not be covered by health insurance. Even though the vaccine is now available to men and women until age 45, many insurance plans do not cover it after age 26.

Children of either sex with a history of sexual abuse should receive their first vaccine dose beginning at age 9.7

Immunocompromised patients should follow the 3-dose schedule regardless of their sex or the age when vaccination was initiated.10

For transgender patients and for men not previously vaccinated who have sex with men, the 3-dose schedule vaccine should be given by the age of 26 (this is a routine recommendation, not a permissive one).8

CHALLENGES OF VACCINATION

Effective patient and family counseling is important. Even though the first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, only 34.9% of US adolescents were fully vaccinated by 2015. This was in part because providers did not recommend it, were unfamiliar with it, or had concerns about its safety,11,12 and in part because some parents refused it.

The physician must address any myths regarding HPV vaccination and ensure that parents and patients understand that HPV vaccine is safe and effective. Studies have shown that with high-quality recommendations (ie, the care provider strongly endorses the HPV vaccine, encourages same-day vaccination, and discusses cancer prevention), patients are 9 times more likely to start the HPV vaccination schedule and 3 times more likely to follow through with subsequent doses.13

Providing good family and patient education does not necessarily require spending more counseling time. A recent study showed that spending less time discussing the HPV vaccine can lead to better vaccine coverage.14 The study compared parent HPV vaccine counseling techniques and found that simply informing patients and their families that the HPV vaccine was due was associated with a higher vaccine acceptance rate than inviting conversations about it.14 When providers announced that the vaccine was due, assuming the parents were ready to vaccinate, there was a 5.4% increase in HPV vaccination coverage.14

Conversely, physicians who engaged parents in open-ended discussions about the HPV vaccine did not improve HPV vaccination coverage.14 The authors suggested that providers approach HPV vaccination as if they were counseling patients and families about the need to avoid second-hand smoke or the need to use car seats. If parents or patients resist the presumptive announcement approach, expanded counseling and shared decision-making are appropriate. This includes addressing misconceptions that parents and patients may have about the HPV vaccine. The American Cancer Society lists 8 facts to reference (Table 2).15

SECONDARY PREVENTION: CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Since the introduction of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test, US cervical cancer incidence rates have decreased by more than 60%.16 Because almost all cervical cancer is preventable with proper screening, all women ages 21 to 65 should be screened.

Currently, there are 3 options available for cervical cancer screening: the Pap-only test, the Pap-HPV cotest, and the high-risk HPV-only test (Table 3). The latter 2 options detect high-risk HPV genotypes.

Several organizations have screening algorithms that recommend when to use these tests, but the 3 that shape today’s standard of care in cervical cancer screening come from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17–19

Pap-only testing is performed every 3 years to screen for cervical neoplasia that might indicate premalignancy.

Pap-HPV cotesting is performed every 5 years in women older than 30 with past normal screening. Until 2018, all 3 organizations recommended cotesting as the preferred screening algorithm for women ages 30 to 65.17–19 Patients with a history of abnormal test results require more frequent testing as recommended by the ASCCP.18

The high-risk HPV-only test utilizes real-time polymerase chain reaction to detect HPV 16, HPV 18, and 12 other HPV genotypes. Only 2 tests are approved by the FDA as stand-alone cervical cancer screening tests—the Roche Cobas HPV test approved in 2014 and the Becton Dickinson Onclarity HPV assay approved in 2018. Other HPV tests that are used in a cotesting strategy should not be used for high-risk HPV-only testing because their performance characteristics may differ.

In 2015, the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) study showed that 1 round of high-risk HPV-only screening for women older than 25 was more sensitive than Pap-only or cotesting for stage 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or more severe disease (after 3 years of follow-up).20 Current guidelines from ASCCP18 and ACOG17 state that the high-risk HPV test can be repeated every 3 years (when used to screen by itself) if the woman is older than 25 and has had a normal test result.

If the HPV test result is positive for high-risk HPV 16 or 18 genotypes, then immediate colposcopy is indicated; women who test positive for one of the other 12 high-risk subtypes will need to undergo a Pap test to determine the appropriate follow-up (Figure 1).18,21

In 2018, the USPSTF updated its recommendations, noting that for women age 30 to 65, Pap-only testing every 3 years, cotesting every 5 years, or high-risk HPV-only testing every 5 years are all appropriate screening strategies, with the Pap-only or high-risk HPV-only screenings being preferred.19 This is in contrast to ACOG and ASCCP recommendations for cotesting every 5 years, with alternative options of Pap-only or HPV-only testing being done every 3 years.17,18

Is there a best screening protocol?

The USPSTF reviewed large randomized and observational studies to summarize the effectiveness of the 3 screening strategies and commissioned a decision analysis model to compare the risks, benefits, and costs of the 3 screening algorithms. The guideline statement notes both cotesting and high-risk HPV testing offer similar cancer detection rates: each prevents 1 additional cancer per 1,000 women screened as opposed to Pap-only testing.19

Also, tests that incorporate high-risk HPV screening may offer better detection of cervical adenocarcinoma (which has a worse prognosis than the more common squamous cell carcinoma type). However, both HPV-based screening strategies are more likely to require additional colposcopies for follow-up than Pap-only screening (1,630 colposcopies required for each cancer prevented with high-risk HPV alone, 1,635 with cotesting). Colposcopy is a simple office procedure that causes minimal discomfort to the patient.

The USPSTF guideline also differs in the recommended frequency of high-risk HPV-only testing; a high-risk HPV result should be repeated every 5 years if normal (as opposed to every 3 years as recommended by ACOG and ASCCP).19 The 5-year recommendation is based on analysis modeling, which suggests that performing high-risk HPV-only testing more frequently is unlikely to improve detection rates but will increase the number of screening tests and colposcopies.19

No trial has directly compared cotesting with high-risk HPV testing for more than 2 rounds of screening. The updated USPSTF recommendations are based on modeling estimates and expert opinion, which assesses cost and benefit vs harm in the long term. Also, no high-risk HPV test is currently FDA-approved for every-5-year screening when used by itself.

All 3 cervical cancer screening methods provide highly effective cancer prevention, so it is important for providers to choose the strategy that best fits their practice. The most critical aspect of screening is getting all women screened, no matter which method is used.

It is critical to remember that the screening intervals are intended for patients without symptoms. Those who have new concerns such as bleeding should have a diagnostic Pap done to evaluate their symptoms.

Follow-up of abnormal results

Regardless of the pathway chosen, appropriate follow-up of any abnormal test result is critical to the early detection of cancer. Established follow-up guidelines exist,22,23 but accessing this information can be difficult for the busy clinician. The ASCCP has a mobile phone application that outlines the action steps corresponding to the patient’s age and results of any combination of Pap or HPV testing. The app also includes the best screening algorithms for a particular patient.24

All guidelines agree that cervical cancer screening should start at age 21, regardless of HPV vaccination status or age of sexual initiation.17,18,25 Screening can be discontinued at age 65 for women with normal screening results in the prior decade (3 consecutive negative Pap results or 2 consecutive negative cotest results).23

For women who have had a total hysterectomy and no history of cervical neoplasia, screening should be stopped immediately after the procedure. However, several high-risk groups of women will need continued screening past the age of 65, or after a hysterectomy.

For a woman with a history of stage 2 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or higher grade lesions, routine screening is continued for an additional 20 years, even if she is over age 65. Pap-only testing every 3 years is acceptable, because the role of HPV testing is unclear after hysterectomy.23 Prior guidelines suggested annual screening in these patients, so the change to every 3 years is notable. Many gynecologic oncologists will recommend that women with a history of cervical cancer continue annual screening indefinitely.

Within the first 2 to 3 years after treatment for high-grade dysplastic changes, annual follow-up is done by the gynecologic oncology team. Providers who offer follow-up during this time frame should keep in communication with the oncology team to ensure appropriate, individualized care. These recommendations are based on expert opinion, so variations in clinical practice may be seen.

Women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus can have Pap-only testing every 3 years, after a series of 3 normal annual Pap results.26 But screening does not stop at age 65.23,26 For patients who are immunosuppressed or have a history of diethylstilbestrol exposure, screening should be done annually indefinitely.23

About 12% of women worldwide are infected with human papillomavirus (HPV).1 Persistent HPV infection with high-risk strains such as HPV 6, 11, 16, and 18 cause nearly all cases of cervical cancer and some anal, vaginal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.2 An estimated 13,000 cases of invasive cervical cancer will be diagnosed this year in the United States alone.3

Up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. A number of changes have been made to the vaccination schedule within the past few years—patients younger than 15 need only 2 rather than 3 doses, and the vaccine itself can be used in adults up to age 45.

Vaccination and routine cervical cancer screening are both necessary to prevent this disease3 along with effective family and patient counseling. Here, we discuss the most up-to-date HPV vaccination recommendations, current cervical cancer screening guidelines, counseling techniques that increase vaccination acceptance rates, and follow-up protocols for abnormal cervical cancer screening results.

TYPES OF HPV VACCINES

HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts.4 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 HPV vaccines:

- Gardasil 9 targets HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 along with 31, 33, 45, 52, 58—these cause 90% of cervical cancer cases and most cases of genital warts5—making it the most effective vaccine available; Gardasil 9 is the only HPV vaccine currently available in the United States

- The bivalent vaccine (Cervarix) targeted HPV 16 and 18 only, and was discontinued in the United States in 2016

- The quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil) targeted HPV 16 and 18 as well as 6 and 11, which cause most cases of genital warts; the last available doses in the United States expired in May 2017; it has been replaced by Gardasil 9.

The incidence of cervical cancer in the United States dropped 29% among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 when HPV vaccination first started to 2011–2014.6

VACCINE DOSING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) revised its HPV vaccine schedule in 2016, when it decreased the necessary doses from 3 to 2 for patients under age 15 and addressed the needs of special patient populations.7 In late 2018, the FDA approved the use of the vaccine in men and women up to age 45. However, no change in guidelines have yet been made (Table 1).

In females, the ACIP recommends starting HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12, but it can be given as early as age 9. A 2-dose schedule is recommended for the 9-valent vaccine before the patient’s 15th birthday (the second dose 6 to 12 months after the first).7 For females who initiate HPV vaccination between ages 15 and 45, a 3-dose schedule is necessary (at 0, 1 to 2, and 6 months).7,8

The change to a 2-dose schedule was prompted by an evaluation of girls ages 9 to 13 randomized to receive either a 2- or 3-dose schedule. Antibody responses with a 2-dose schedule were not inferior to those of young women (ages 16 to 26) who received all 3 doses.9 The geometric mean titer ratios remained noninferior throughout the study period of 36 months.

However, a loss of noninferiority was noted for HPV-18 by 24 months and for HPV-6 by 36 months.9 Thus, further studies are needed to understand the duration of protection with a 2-dose schedule. Nevertheless, decreasing the number of doses makes it a more convenient and cost-effective option for many families.

The recommendations are the same for males except for one notable difference: in males ages 21 to 26, vaccination is not routinely recommended by the ACIP, but rather it is considered a “permissive use” recommendation: ie, the vaccine should be offered and final decisions on administration be made after individualized discussion with the patient.10 Permissive-use status also means the vaccine may not be covered by health insurance. Even though the vaccine is now available to men and women until age 45, many insurance plans do not cover it after age 26.

Children of either sex with a history of sexual abuse should receive their first vaccine dose beginning at age 9.7

Immunocompromised patients should follow the 3-dose schedule regardless of their sex or the age when vaccination was initiated.10

For transgender patients and for men not previously vaccinated who have sex with men, the 3-dose schedule vaccine should be given by the age of 26 (this is a routine recommendation, not a permissive one).8

CHALLENGES OF VACCINATION

Effective patient and family counseling is important. Even though the first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, only 34.9% of US adolescents were fully vaccinated by 2015. This was in part because providers did not recommend it, were unfamiliar with it, or had concerns about its safety,11,12 and in part because some parents refused it.

The physician must address any myths regarding HPV vaccination and ensure that parents and patients understand that HPV vaccine is safe and effective. Studies have shown that with high-quality recommendations (ie, the care provider strongly endorses the HPV vaccine, encourages same-day vaccination, and discusses cancer prevention), patients are 9 times more likely to start the HPV vaccination schedule and 3 times more likely to follow through with subsequent doses.13

Providing good family and patient education does not necessarily require spending more counseling time. A recent study showed that spending less time discussing the HPV vaccine can lead to better vaccine coverage.14 The study compared parent HPV vaccine counseling techniques and found that simply informing patients and their families that the HPV vaccine was due was associated with a higher vaccine acceptance rate than inviting conversations about it.14 When providers announced that the vaccine was due, assuming the parents were ready to vaccinate, there was a 5.4% increase in HPV vaccination coverage.14

Conversely, physicians who engaged parents in open-ended discussions about the HPV vaccine did not improve HPV vaccination coverage.14 The authors suggested that providers approach HPV vaccination as if they were counseling patients and families about the need to avoid second-hand smoke or the need to use car seats. If parents or patients resist the presumptive announcement approach, expanded counseling and shared decision-making are appropriate. This includes addressing misconceptions that parents and patients may have about the HPV vaccine. The American Cancer Society lists 8 facts to reference (Table 2).15

SECONDARY PREVENTION: CERVICAL CANCER SCREENING

Since the introduction of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test, US cervical cancer incidence rates have decreased by more than 60%.16 Because almost all cervical cancer is preventable with proper screening, all women ages 21 to 65 should be screened.

Currently, there are 3 options available for cervical cancer screening: the Pap-only test, the Pap-HPV cotest, and the high-risk HPV-only test (Table 3). The latter 2 options detect high-risk HPV genotypes.

Several organizations have screening algorithms that recommend when to use these tests, but the 3 that shape today’s standard of care in cervical cancer screening come from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP), and US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17–19

Pap-only testing is performed every 3 years to screen for cervical neoplasia that might indicate premalignancy.

Pap-HPV cotesting is performed every 5 years in women older than 30 with past normal screening. Until 2018, all 3 organizations recommended cotesting as the preferred screening algorithm for women ages 30 to 65.17–19 Patients with a history of abnormal test results require more frequent testing as recommended by the ASCCP.18

The high-risk HPV-only test utilizes real-time polymerase chain reaction to detect HPV 16, HPV 18, and 12 other HPV genotypes. Only 2 tests are approved by the FDA as stand-alone cervical cancer screening tests—the Roche Cobas HPV test approved in 2014 and the Becton Dickinson Onclarity HPV assay approved in 2018. Other HPV tests that are used in a cotesting strategy should not be used for high-risk HPV-only testing because their performance characteristics may differ.

In 2015, the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) study showed that 1 round of high-risk HPV-only screening for women older than 25 was more sensitive than Pap-only or cotesting for stage 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or more severe disease (after 3 years of follow-up).20 Current guidelines from ASCCP18 and ACOG17 state that the high-risk HPV test can be repeated every 3 years (when used to screen by itself) if the woman is older than 25 and has had a normal test result.

If the HPV test result is positive for high-risk HPV 16 or 18 genotypes, then immediate colposcopy is indicated; women who test positive for one of the other 12 high-risk subtypes will need to undergo a Pap test to determine the appropriate follow-up (Figure 1).18,21

In 2018, the USPSTF updated its recommendations, noting that for women age 30 to 65, Pap-only testing every 3 years, cotesting every 5 years, or high-risk HPV-only testing every 5 years are all appropriate screening strategies, with the Pap-only or high-risk HPV-only screenings being preferred.19 This is in contrast to ACOG and ASCCP recommendations for cotesting every 5 years, with alternative options of Pap-only or HPV-only testing being done every 3 years.17,18

Is there a best screening protocol?

The USPSTF reviewed large randomized and observational studies to summarize the effectiveness of the 3 screening strategies and commissioned a decision analysis model to compare the risks, benefits, and costs of the 3 screening algorithms. The guideline statement notes both cotesting and high-risk HPV testing offer similar cancer detection rates: each prevents 1 additional cancer per 1,000 women screened as opposed to Pap-only testing.19

Also, tests that incorporate high-risk HPV screening may offer better detection of cervical adenocarcinoma (which has a worse prognosis than the more common squamous cell carcinoma type). However, both HPV-based screening strategies are more likely to require additional colposcopies for follow-up than Pap-only screening (1,630 colposcopies required for each cancer prevented with high-risk HPV alone, 1,635 with cotesting). Colposcopy is a simple office procedure that causes minimal discomfort to the patient.

The USPSTF guideline also differs in the recommended frequency of high-risk HPV-only testing; a high-risk HPV result should be repeated every 5 years if normal (as opposed to every 3 years as recommended by ACOG and ASCCP).19 The 5-year recommendation is based on analysis modeling, which suggests that performing high-risk HPV-only testing more frequently is unlikely to improve detection rates but will increase the number of screening tests and colposcopies.19

No trial has directly compared cotesting with high-risk HPV testing for more than 2 rounds of screening. The updated USPSTF recommendations are based on modeling estimates and expert opinion, which assesses cost and benefit vs harm in the long term. Also, no high-risk HPV test is currently FDA-approved for every-5-year screening when used by itself.

All 3 cervical cancer screening methods provide highly effective cancer prevention, so it is important for providers to choose the strategy that best fits their practice. The most critical aspect of screening is getting all women screened, no matter which method is used.

It is critical to remember that the screening intervals are intended for patients without symptoms. Those who have new concerns such as bleeding should have a diagnostic Pap done to evaluate their symptoms.

Follow-up of abnormal results

Regardless of the pathway chosen, appropriate follow-up of any abnormal test result is critical to the early detection of cancer. Established follow-up guidelines exist,22,23 but accessing this information can be difficult for the busy clinician. The ASCCP has a mobile phone application that outlines the action steps corresponding to the patient’s age and results of any combination of Pap or HPV testing. The app also includes the best screening algorithms for a particular patient.24

All guidelines agree that cervical cancer screening should start at age 21, regardless of HPV vaccination status or age of sexual initiation.17,18,25 Screening can be discontinued at age 65 for women with normal screening results in the prior decade (3 consecutive negative Pap results or 2 consecutive negative cotest results).23

For women who have had a total hysterectomy and no history of cervical neoplasia, screening should be stopped immediately after the procedure. However, several high-risk groups of women will need continued screening past the age of 65, or after a hysterectomy.

For a woman with a history of stage 2 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or higher grade lesions, routine screening is continued for an additional 20 years, even if she is over age 65. Pap-only testing every 3 years is acceptable, because the role of HPV testing is unclear after hysterectomy.23 Prior guidelines suggested annual screening in these patients, so the change to every 3 years is notable. Many gynecologic oncologists will recommend that women with a history of cervical cancer continue annual screening indefinitely.

Within the first 2 to 3 years after treatment for high-grade dysplastic changes, annual follow-up is done by the gynecologic oncology team. Providers who offer follow-up during this time frame should keep in communication with the oncology team to ensure appropriate, individualized care. These recommendations are based on expert opinion, so variations in clinical practice may be seen.

Women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus can have Pap-only testing every 3 years, after a series of 3 normal annual Pap results.26 But screening does not stop at age 65.23,26 For patients who are immunosuppressed or have a history of diethylstilbestrol exposure, screening should be done annually indefinitely.23

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010; 202(12):1789–1799. doi:10.1086/657321

- de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(6):607–615. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for cervical cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JME, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(49):1405–1408. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Supplemental information and guidance for vaccination providers regarding use of 9-valent HPV vaccine Information for persons who started an HPV vaccination series with quadrivalent or bivalent HPV vaccine. www.cdc.gov/hpv/downloads/9vhpv-guidance.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309(17):1793–1802. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1625

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR-05):1–30. pmid:25167164

- Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, Kadono M, Daley EM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: what are the reasons for nonvaccination among US adolescents? J Adolesc Health 2017; 61(3):288–293. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.015

- Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(33):850–858. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a4

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine 2016; 34(9):1187–1192. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2017; 139(1):e20161764. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764

- American Cancer Society. HPV vaccine facts. www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/infectious-agents/hpv/hpv-vaccine-facts-and-fears.html. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- National Cancer Institute; Chasan R, Manrow R. Cervical cancer. https://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/viewfactsheet.aspx?csid=76. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Frequently asked questions. Cervical cancer screening. www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Cervical-Cancer-Screening. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 2012; 137(4):516–542. doi:10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018; 320(7):674–686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 136(2):189–197. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.076

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125(2):330–337. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121(4):829–846. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128(4):e111–e130. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708

- ASCCP. Mobile app. http://www.asccp.org/store-detail2/asccp-mobile-app. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- USPSTF. Draft recommendation: cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Masur H, Brooks JT, Benson CA, Holmes KK, Pau AK, Kaplan JE; National Institutes of Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(9):1308–1311. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu094

- Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010; 202(12):1789–1799. doi:10.1086/657321

- de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(6):607–615. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for cervical cancer. www.cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JME, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(49):1405–1408. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Supplemental information and guidance for vaccination providers regarding use of 9-valent HPV vaccine Information for persons who started an HPV vaccination series with quadrivalent or bivalent HPV vaccine. www.cdc.gov/hpv/downloads/9vhpv-guidance.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Dobson SR, McNeil S, Dionne M, et al. Immunogenicity of 2 doses of HPV vaccine in younger adolescents vs 3 doses in young women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 309(17):1793–1802. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1625

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR-05):1–30. pmid:25167164

- Thompson EL, Rosen BL, Vamos CA, Kadono M, Daley EM. Human papillomavirus vaccination: what are the reasons for nonvaccination among US adolescents? J Adolesc Health 2017; 61(3):288–293. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.015

- Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65(33):850–858. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6533a4

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine 2016; 34(9):1187–1192. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2017; 139(1):e20161764. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764

- American Cancer Society. HPV vaccine facts. www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/infectious-agents/hpv/hpv-vaccine-facts-and-fears.html. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- National Cancer Institute; Chasan R, Manrow R. Cervical cancer. https://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/viewfactsheet.aspx?csid=76. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Frequently asked questions. Cervical cancer screening. www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Cervical-Cancer-Screening. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol 2012; 137(4):516–542. doi:10.1309/AJCPTGD94EVRSJCG

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018; 320(7):674–686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 136(2):189–197. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.076

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 125(2):330–337. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000669

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121(4):829–846. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 128(4):e111–e130. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708

- ASCCP. Mobile app. http://www.asccp.org/store-detail2/asccp-mobile-app. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- USPSTF. Draft recommendation: cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement/cervical-cancer-screening2. Accessed February 14, 2019.

- Masur H, Brooks JT, Benson CA, Holmes KK, Pau AK, Kaplan JE; National Institutes of Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: Updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(9):1308–1311. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu094

KEY POINTS

- Immunization against HPV can prevent up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases.

- Gardasil 9 is the only HPV vaccine currently available in the United States and is now approved for use in males and females between the ages of 9 and 45.

- In girls and boys younger than 15, a 2-dose schedule is recommended; patients ages 15 through 45 require 3 doses.

- Vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions.

- Regular cervical cancer screening is an important preventive tool and should be performed using the Papanicolaou (Pap) test, the high-risk HPV-only test, or the Pap-HPV cotest.

Cancer screening: A modest proposal for prevention

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old, a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled, and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee, or ragout.

—Jonathan Swift, A Modest Proposal1

Large-scale cancer screening programs have the unintended consequences of false-positive results and overdiagnosis, leading to anxiety and overtreatment. The magnitude of these harms continues to be clarified after decades of screening.

Recognizing the trade-off between benefits and harms, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has changed several of its recommendations in recent years. Breast cancer screening recommendations have gone from yearly mammograms starting at age 40 to biennial mammograms starting at age 50 for women at average risk.2 Prostate cancer screening is no longer recommended for men age 70 and older, and even for men between 55 and 69, screening is now an individual decision.3

Newer screening programs are targeting high-risk groups rather than the general population, with the aim of increasing the likelihood of benefits and limiting the harms. For example, lung cancer screening is recommended only for current smokers or smokers who have quit within the past 15 years, are between 55 and 80, and have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history.4

The movement toward less-frequent screening and screening in a narrower population has evoked strong reactions from advocates of cancer screening. One professor of radiology writes, “It borders on unethical to suggest that the benefit of having your life saved by screening and living another 40 years can be balanced against the ‘harm’ of being recalled for additional mammographic views for what proves to not be a cancer.”5 Another notes, “It does not make any sense to throw away the lives saved by screening to avoid over-treating a small number of cancers.”6 Both of these authors defend the position that the goal of screening is to minimize cause-specific mortality, irrespective of overdiagnosis, overtreatment, or false-positive results. In other words, harm should have little to no weight in screening recommendations.

Although the debate on cancer screening is moving toward a more balanced discussion of benefits and harms, many patients are still subjected to screening that is more aggressive than the USPSTF recommends, which may be due to an underlying belief that no harm is greater than the benefit of saving a life.

IS MORE-AGGRESSIVE SCREENING THE ANSWER?

One may wonder if more-aggressive screening could prevent deaths that occur despite standard screening. For example, more-frequent screening or use of additional screening methods such as ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging has been suggested for patients at high risk of breast cancer.

A MODEST PROPOSAL

If one holds the view that benefits alone should be considered when writing recommendations about screening, the logical conclusion extends beyond screening. We would therefore like to propose a different approach to reducing cancer deaths in the general population:

Why not just remove everybody’s breasts, prostate gland, and colon before cancer arises?

TO CUT IS TO PREVENT

Currently, we offer prophylactic surgery to patients at high risk of cancer. For example, women with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations are offered prophylactic mastectomy as one of several options for reducing risk of breast cancer. In 2013, the first case of prophylactic prostatectomy was performed in a man who had a BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation. Total colectomy is considered in men and women who have hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, instead of segmental resection, to prevent future cancer.

If prophylactic surgery were extended to the general population, it would greatly reduce the number of cancer deaths. Assuming that removing an organ almost always precludes development of cancer, we may predict that prophylactic mastectomy, prostatectomy, or colectomy would save the lives of most of the patients who are still dying of cancer of these organs. The effectiveness rates would approach, but not reach 100%; such is the case with prophylactic mastectomy.

Consider prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening. Even using the favorable estimate of the impact of PSA screening, arising from the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer trial, 27 men have to be diagnosed, most undergoing local therapy (the trial was conducted before active surveillance became routine), to avert 1 death from prostate cancer over 13 years.9

Contrast this “number needed to diagnose” with the number needed to treat for a strategy of routine prostate removal at age 45 or 50. Given that the lifetime risk of death from prostate cancer approaches 3%, and few cases arise before this age, a prophylactic surgical strategy would avert 1 death per 33 operations. If proponents of screening are willing to accept a number needed to diagnose of 27 over a 13-year interval, they may be willing to consider a number needed to treat of 33 over a lifetime.

There may be harms such as perioperative and postoperative complications. Mastectomy could lead to emotional stress from altered body image. Prostatectomy can have long-term complications such as urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Nevertheless, prophylactic organ removal would save far more lives than current screening practices. It also could decrease mental burden, as patients could rest assured that they will never develop cancer, whereas screening often involves ambiguous test results, follow-up tests, and interventions, increasing patient anxiety.

FINDING THE BALANCE BETWEEN BENEFITS AND HARMS

In truth, we do not really advocate universal mastectomy, prostatectomy, and colectomy to prevent cancer, no more than Swift1 really wanted to eat the children of Ireland to alleviate poverty and famine in that country. Rather, we use it as an extreme proposal to highlight the scope and depth of harms that inevitably arise from screening.

If proponents of aggressive screening believe that the goal is to reduce cause-specific mortality as much as possible, giving little weight or consideration to overdiagnosis and overtreatment, then they ought to embrace universal prophylactic surgery as well. Recognition of this logical consequence reminds us that we must make screening recommendations that balance benefits and harms.

Considering an extreme perspective can help in recognizing our bias toward saving lives from cancer and discounting the harms. Aggravating this bias, it is impossible to know whether an individual patient has avoided fatal cancer or undergone unnecessary treatment. Moreover, changing practice is more difficult if it involves rolling back interventions that were once the standard.

Balancing benefits and harms is especially difficult when trying to compare the benefit of preventing a single cancer death against a harm that is less serious but more common. Medicine has always involved difficult trade-offs, as seen in cost-benefit analysis of new treatments or balancing quality of life with quantity of life in a single patient. In addition, each individual may place different values on benefits of screening and avoiding possible harms.

There is an undeniable trade-off with screening, and we must make a conscious decision on where to draw the line when harms outweigh the benefits. We must proceed with caution when subjecting large numbers of men and women to the possibility of psychological burden and decreased quality of life.

Given the growing appreciation of the harms of screening, it is likely that future guidance will continue to move toward less- frequent screening or focusing resources on high-risk populations, where the absolute magnitude of benefit is greater. Cancer screening is also likely to become an individual decision based on personal values and informed decisions.

- Swift J. A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland, from Being a Burden on Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick. Dublin: S. Harding, 1729.

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Humphrey L, et al. Screening for breast cancer: a systematic review to update the 2009 US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343819. Accessed February 13, 2019.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018; 319(18):1901–1913. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3710

- Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer: systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK154610. Accessed February 13, 2019.

- Kopans DB. A review of: “Tipping the balance of benefits and harms to favor screening mammography starting at age 40 years.” www.sbi-online.org/Portals/0/downloads/documents/pdfs/A%20review%20of%20Tipping%20the%20Balance%20of%20Benefits%20and%20Harms%20to%20Favor%20Screening%20Mammography%20Starting%20at%20Age%2040%20Years%20-%20Kopans.pdf. Accessed February 13, 2019.

- Yaffe M, Gordon, P. Routine mammograms do save lives: U of T expert. U of T News. www.utoronto.ca/news/routine-mammograms-do-save-lives-u-t-expert. Accessed February 13, 2019.

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016; 315(23):2576–2594. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.3332

- Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2016; 315(23):2595–2609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6828

- Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al; ERSPC Investigators. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014; 384(9959):2027–2035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0

I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old, a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled, and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee, or ragout.

—Jonathan Swift, A Modest Proposal1

Large-scale cancer screening programs have the unintended consequences of false-positive results and overdiagnosis, leading to anxiety and overtreatment. The magnitude of these harms continues to be clarified after decades of screening.

Recognizing the trade-off between benefits and harms, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has changed several of its recommendations in recent years. Breast cancer screening recommendations have gone from yearly mammograms starting at age 40 to biennial mammograms starting at age 50 for women at average risk.2 Prostate cancer screening is no longer recommended for men age 70 and older, and even for men between 55 and 69, screening is now an individual decision.3

Newer screening programs are targeting high-risk groups rather than the general population, with the aim of increasing the likelihood of benefits and limiting the harms. For example, lung cancer screening is recommended only for current smokers or smokers who have quit within the past 15 years, are between 55 and 80, and have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history.4

The movement toward less-frequent screening and screening in a narrower population has evoked strong reactions from advocates of cancer screening. One professor of radiology writes, “It borders on unethical to suggest that the benefit of having your life saved by screening and living another 40 years can be balanced against the ‘harm’ of being recalled for additional mammographic views for what proves to not be a cancer.”5 Another notes, “It does not make any sense to throw away the lives saved by screening to avoid over-treating a small number of cancers.”6 Both of these authors defend the position that the goal of screening is to minimize cause-specific mortality, irrespective of overdiagnosis, overtreatment, or false-positive results. In other words, harm should have little to no weight in screening recommendations.

Although the debate on cancer screening is moving toward a more balanced discussion of benefits and harms, many patients are still subjected to screening that is more aggressive than the USPSTF recommends, which may be due to an underlying belief that no harm is greater than the benefit of saving a life.

IS MORE-AGGRESSIVE SCREENING THE ANSWER?

One may wonder if more-aggressive screening could prevent deaths that occur despite standard screening. For example, more-frequent screening or use of additional screening methods such as ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging has been suggested for patients at high risk of breast cancer.

A MODEST PROPOSAL

If one holds the view that benefits alone should be considered when writing recommendations about screening, the logical conclusion extends beyond screening. We would therefore like to propose a different approach to reducing cancer deaths in the general population:

Why not just remove everybody’s breasts, prostate gland, and colon before cancer arises?

TO CUT IS TO PREVENT

Currently, we offer prophylactic surgery to patients at high risk of cancer. For example, women with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations are offered prophylactic mastectomy as one of several options for reducing risk of breast cancer. In 2013, the first case of prophylactic prostatectomy was performed in a man who had a BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation. Total colectomy is considered in men and women who have hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, instead of segmental resection, to prevent future cancer.

If prophylactic surgery were extended to the general population, it would greatly reduce the number of cancer deaths. Assuming that removing an organ almost always precludes development of cancer, we may predict that prophylactic mastectomy, prostatectomy, or colectomy would save the lives of most of the patients who are still dying of cancer of these organs. The effectiveness rates would approach, but not reach 100%; such is the case with prophylactic mastectomy.

Consider prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening. Even using the favorable estimate of the impact of PSA screening, arising from the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer trial, 27 men have to be diagnosed, most undergoing local therapy (the trial was conducted before active surveillance became routine), to avert 1 death from prostate cancer over 13 years.9

Contrast this “number needed to diagnose” with the number needed to treat for a strategy of routine prostate removal at age 45 or 50. Given that the lifetime risk of death from prostate cancer approaches 3%, and few cases arise before this age, a prophylactic surgical strategy would avert 1 death per 33 operations. If proponents of screening are willing to accept a number needed to diagnose of 27 over a 13-year interval, they may be willing to consider a number needed to treat of 33 over a lifetime.

There may be harms such as perioperative and postoperative complications. Mastectomy could lead to emotional stress from altered body image. Prostatectomy can have long-term complications such as urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Nevertheless, prophylactic organ removal would save far more lives than current screening practices. It also could decrease mental burden, as patients could rest assured that they will never develop cancer, whereas screening often involves ambiguous test results, follow-up tests, and interventions, increasing patient anxiety.

FINDING THE BALANCE BETWEEN BENEFITS AND HARMS

In truth, we do not really advocate universal mastectomy, prostatectomy, and colectomy to prevent cancer, no more than Swift1 really wanted to eat the children of Ireland to alleviate poverty and famine in that country. Rather, we use it as an extreme proposal to highlight the scope and depth of harms that inevitably arise from screening.