User login

SVS Members: Pay Your Dues!

By renewing your membership, you continue to support the critical work the Society does throughout the year, and you contribute directly to the ongoing improvement of vascular health. Renewing will also provide you continued access to all membership benefits, including access to peer-reviewed journals, your members-only community on SVSConnect, and discounts on meetings and educational products.

Avoid a lapse in your SVS membership and loss of benefits. Pay your open invoice online by logging on to your SVS member page. Pay your dues here.

By renewing your membership, you continue to support the critical work the Society does throughout the year, and you contribute directly to the ongoing improvement of vascular health. Renewing will also provide you continued access to all membership benefits, including access to peer-reviewed journals, your members-only community on SVSConnect, and discounts on meetings and educational products.

Avoid a lapse in your SVS membership and loss of benefits. Pay your open invoice online by logging on to your SVS member page. Pay your dues here.

By renewing your membership, you continue to support the critical work the Society does throughout the year, and you contribute directly to the ongoing improvement of vascular health. Renewing will also provide you continued access to all membership benefits, including access to peer-reviewed journals, your members-only community on SVSConnect, and discounts on meetings and educational products.

Avoid a lapse in your SVS membership and loss of benefits. Pay your open invoice online by logging on to your SVS member page. Pay your dues here.

SVS-SCVS-VESS Leadership Development Program Coming in 2020

Based on member needs assessment, SVS members have been asking for a more comprehensive, vascular surgery-specific leadership development program. The SVS, working in collaboration with the VESS and SCVS, is pleased to announce a unique program opportunity for vascular surgeons 5-10 years post-training. The focus of the program will be on the development of leadership skills identified by members as most relevant to accelerating their leadership efforts at their home institution or practice, society or community. Be on the lookout for the program application, and all the details, next week. Completed applications will be due November 22nd. There will be a limit of 20 vascular surgeons selected in the first program cohort.

Based on member needs assessment, SVS members have been asking for a more comprehensive, vascular surgery-specific leadership development program. The SVS, working in collaboration with the VESS and SCVS, is pleased to announce a unique program opportunity for vascular surgeons 5-10 years post-training. The focus of the program will be on the development of leadership skills identified by members as most relevant to accelerating their leadership efforts at their home institution or practice, society or community. Be on the lookout for the program application, and all the details, next week. Completed applications will be due November 22nd. There will be a limit of 20 vascular surgeons selected in the first program cohort.

Based on member needs assessment, SVS members have been asking for a more comprehensive, vascular surgery-specific leadership development program. The SVS, working in collaboration with the VESS and SCVS, is pleased to announce a unique program opportunity for vascular surgeons 5-10 years post-training. The focus of the program will be on the development of leadership skills identified by members as most relevant to accelerating their leadership efforts at their home institution or practice, society or community. Be on the lookout for the program application, and all the details, next week. Completed applications will be due November 22nd. There will be a limit of 20 vascular surgeons selected in the first program cohort.

The effect of smoking lingers

Lung function appears to continue to decline even decades after smoking cessation, according to new data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Pooled Cohort Study. Compared with never-smokers, former smokers had a decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) about 20% as severe as current smokers, but nevertheless higher than never-smokers. Low-intensity smokers also fared worse than never-smokers, suggesting that no amount of smoke exposure should be considered safe.

The increased decline occurred even decades after smoking cessation, according to the study published in Lancet Respiratory Medicine, which was led by Elizabeth Oelsner, MD, MPH, of Columbia University, New York. Smoking prevalence has decreased from 42% to 16% in the past 50 years, and many smokers report that they smoke fewer cigarettes per day, from an average of 21 to 14, according to the authors. Despite those trends, the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has continued to increase, and is now the third-leading cause of death worldwide.

A meta-analysis of 47 studies and 88,887 adults found no association between smoking and FEV1 decline, but many of the studies were small or focused on nonrepresentative populations, and they used variably standardized spirometry.

The study pooled data from nine individual U.S. cohorts, with 25,352 participants recruited during 1983-2016. Subjects included those who underwent at least two prebronchodilator spirometry tests following American Thoracic Society standards. After adjustment, former smokers had increased FEV1 decline of 1.82 mL/year (P less than .0001), compared with never-smokers. Current smokers had an increased decline of 9.21 mL/year (P less than .0001).

Even after decades of abstinence, the effects of smoking appeared to linger: 20-30 years later, FEV1 loss was accelerated by 2.50 mL/year (P less than .0001), and by 0.93 mL/year (P = .0104) after 30 years, compared with never-smokers.

Even low-intensity smokers (cumulative less than 10 pack-years) had an significantly accelerated FEV1 decline (0.87 mL; P = .0153).

The researchers also found a relationship between FEV1 decline and intensity of current smoking: Those smoking fewer than 5 cigarettes per day had a lower decline than those smoking 30 or more (7.65 mL; 95% confidence interval, 6.21-9.09 vs. 11.24 mL; 95% CI, 9.86-12.62).

The study is limited by the fact that smoking status and daily tobacco reporting were self-reported, which could result in information bias.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The authors report personal fees, consultancy fees, or grants from a wide variety of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Oelsner EC et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30276-0.

It is unclear whether the small increase in FEV1 decline (1.82 mL) seen among former smokers is clinically significant, though it suggests lasting damage from smoking. The increased decline in low-intensity smokers is an important observation confirming accumulating evidence that no amount of smoking is free of harm. This is a key message because some physicians and members of the public believe that low-intensity smoking and use of low-dose tobacco products can reduce or eliminate risk, according to Yunus Çolak, MD, and Peter Lange, MD, in their accompanying commentary (Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Oct 9. doi. org/10.1016/S2213-2600[19]30349-2). “More information is needed to manage patients with COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in an era with decreasing smoking prevalence and an increasing proportion of smokers with low,” they added. “We should begin by questioning the arbitrary cutoff of 10 pack-years of cumulated tobacco exposure, which is currently the rule in most clinical trials of COPD. Additionally, we should not promote low-intensity smoking and use of low-dose tobacco products as a means of harm reduction but instead promote early smoking cessation,” they concluded.

Dr. Çolak and Dr. Lange are at the University of Copenhagen. The remarks are from their online commentary to the article. The reported receiving fees and grants from a variety of pharmaceutical companies.

It is unclear whether the small increase in FEV1 decline (1.82 mL) seen among former smokers is clinically significant, though it suggests lasting damage from smoking. The increased decline in low-intensity smokers is an important observation confirming accumulating evidence that no amount of smoking is free of harm. This is a key message because some physicians and members of the public believe that low-intensity smoking and use of low-dose tobacco products can reduce or eliminate risk, according to Yunus Çolak, MD, and Peter Lange, MD, in their accompanying commentary (Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Oct 9. doi. org/10.1016/S2213-2600[19]30349-2). “More information is needed to manage patients with COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in an era with decreasing smoking prevalence and an increasing proportion of smokers with low,” they added. “We should begin by questioning the arbitrary cutoff of 10 pack-years of cumulated tobacco exposure, which is currently the rule in most clinical trials of COPD. Additionally, we should not promote low-intensity smoking and use of low-dose tobacco products as a means of harm reduction but instead promote early smoking cessation,” they concluded.

Dr. Çolak and Dr. Lange are at the University of Copenhagen. The remarks are from their online commentary to the article. The reported receiving fees and grants from a variety of pharmaceutical companies.

It is unclear whether the small increase in FEV1 decline (1.82 mL) seen among former smokers is clinically significant, though it suggests lasting damage from smoking. The increased decline in low-intensity smokers is an important observation confirming accumulating evidence that no amount of smoking is free of harm. This is a key message because some physicians and members of the public believe that low-intensity smoking and use of low-dose tobacco products can reduce or eliminate risk, according to Yunus Çolak, MD, and Peter Lange, MD, in their accompanying commentary (Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Oct 9. doi. org/10.1016/S2213-2600[19]30349-2). “More information is needed to manage patients with COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in an era with decreasing smoking prevalence and an increasing proportion of smokers with low,” they added. “We should begin by questioning the arbitrary cutoff of 10 pack-years of cumulated tobacco exposure, which is currently the rule in most clinical trials of COPD. Additionally, we should not promote low-intensity smoking and use of low-dose tobacco products as a means of harm reduction but instead promote early smoking cessation,” they concluded.

Dr. Çolak and Dr. Lange are at the University of Copenhagen. The remarks are from their online commentary to the article. The reported receiving fees and grants from a variety of pharmaceutical companies.

Lung function appears to continue to decline even decades after smoking cessation, according to new data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Pooled Cohort Study. Compared with never-smokers, former smokers had a decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) about 20% as severe as current smokers, but nevertheless higher than never-smokers. Low-intensity smokers also fared worse than never-smokers, suggesting that no amount of smoke exposure should be considered safe.

The increased decline occurred even decades after smoking cessation, according to the study published in Lancet Respiratory Medicine, which was led by Elizabeth Oelsner, MD, MPH, of Columbia University, New York. Smoking prevalence has decreased from 42% to 16% in the past 50 years, and many smokers report that they smoke fewer cigarettes per day, from an average of 21 to 14, according to the authors. Despite those trends, the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has continued to increase, and is now the third-leading cause of death worldwide.

A meta-analysis of 47 studies and 88,887 adults found no association between smoking and FEV1 decline, but many of the studies were small or focused on nonrepresentative populations, and they used variably standardized spirometry.

The study pooled data from nine individual U.S. cohorts, with 25,352 participants recruited during 1983-2016. Subjects included those who underwent at least two prebronchodilator spirometry tests following American Thoracic Society standards. After adjustment, former smokers had increased FEV1 decline of 1.82 mL/year (P less than .0001), compared with never-smokers. Current smokers had an increased decline of 9.21 mL/year (P less than .0001).

Even after decades of abstinence, the effects of smoking appeared to linger: 20-30 years later, FEV1 loss was accelerated by 2.50 mL/year (P less than .0001), and by 0.93 mL/year (P = .0104) after 30 years, compared with never-smokers.

Even low-intensity smokers (cumulative less than 10 pack-years) had an significantly accelerated FEV1 decline (0.87 mL; P = .0153).

The researchers also found a relationship between FEV1 decline and intensity of current smoking: Those smoking fewer than 5 cigarettes per day had a lower decline than those smoking 30 or more (7.65 mL; 95% confidence interval, 6.21-9.09 vs. 11.24 mL; 95% CI, 9.86-12.62).

The study is limited by the fact that smoking status and daily tobacco reporting were self-reported, which could result in information bias.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The authors report personal fees, consultancy fees, or grants from a wide variety of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Oelsner EC et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30276-0.

Lung function appears to continue to decline even decades after smoking cessation, according to new data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Pooled Cohort Study. Compared with never-smokers, former smokers had a decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) about 20% as severe as current smokers, but nevertheless higher than never-smokers. Low-intensity smokers also fared worse than never-smokers, suggesting that no amount of smoke exposure should be considered safe.

The increased decline occurred even decades after smoking cessation, according to the study published in Lancet Respiratory Medicine, which was led by Elizabeth Oelsner, MD, MPH, of Columbia University, New York. Smoking prevalence has decreased from 42% to 16% in the past 50 years, and many smokers report that they smoke fewer cigarettes per day, from an average of 21 to 14, according to the authors. Despite those trends, the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has continued to increase, and is now the third-leading cause of death worldwide.

A meta-analysis of 47 studies and 88,887 adults found no association between smoking and FEV1 decline, but many of the studies were small or focused on nonrepresentative populations, and they used variably standardized spirometry.

The study pooled data from nine individual U.S. cohorts, with 25,352 participants recruited during 1983-2016. Subjects included those who underwent at least two prebronchodilator spirometry tests following American Thoracic Society standards. After adjustment, former smokers had increased FEV1 decline of 1.82 mL/year (P less than .0001), compared with never-smokers. Current smokers had an increased decline of 9.21 mL/year (P less than .0001).

Even after decades of abstinence, the effects of smoking appeared to linger: 20-30 years later, FEV1 loss was accelerated by 2.50 mL/year (P less than .0001), and by 0.93 mL/year (P = .0104) after 30 years, compared with never-smokers.

Even low-intensity smokers (cumulative less than 10 pack-years) had an significantly accelerated FEV1 decline (0.87 mL; P = .0153).

The researchers also found a relationship between FEV1 decline and intensity of current smoking: Those smoking fewer than 5 cigarettes per day had a lower decline than those smoking 30 or more (7.65 mL; 95% confidence interval, 6.21-9.09 vs. 11.24 mL; 95% CI, 9.86-12.62).

The study is limited by the fact that smoking status and daily tobacco reporting were self-reported, which could result in information bias.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The authors report personal fees, consultancy fees, or grants from a wide variety of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Oelsner EC et al. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30276-0.

REPORTING FROM LANCET RESPIRATORY MEDICINE

Duloxetine ‘sprinkle’ launches for patients with difficulty swallowing

Drizalma Sprinkle (duloxetine delayed-release capsule) has launched for the treatment of various neuropsychiatric and pain disorders in patients with difficulty swallowing, according to a release from Sun Pharma. It can be swallowed whole, sprinkled on applesauce, or administered via nasogastric tube.

Difficulty swallowing affects approximately 30%-35% of long-term care residents, but the main alternative – crushing tablets – introduces risks of its own to the administration process.

This sprinkle is indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults, generalized anxiety disorder in patients aged 7 years and older, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain in adults, and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for these indications July 19, 2019.

It carries a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The most common adverse reactions (5% or more of treated participants and twice the incidence with placebo) were nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, decreased appetite, and hyperhidrosis. The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

[email protected]

Drizalma Sprinkle (duloxetine delayed-release capsule) has launched for the treatment of various neuropsychiatric and pain disorders in patients with difficulty swallowing, according to a release from Sun Pharma. It can be swallowed whole, sprinkled on applesauce, or administered via nasogastric tube.

Difficulty swallowing affects approximately 30%-35% of long-term care residents, but the main alternative – crushing tablets – introduces risks of its own to the administration process.

This sprinkle is indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults, generalized anxiety disorder in patients aged 7 years and older, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain in adults, and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for these indications July 19, 2019.

It carries a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The most common adverse reactions (5% or more of treated participants and twice the incidence with placebo) were nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, decreased appetite, and hyperhidrosis. The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

[email protected]

Drizalma Sprinkle (duloxetine delayed-release capsule) has launched for the treatment of various neuropsychiatric and pain disorders in patients with difficulty swallowing, according to a release from Sun Pharma. It can be swallowed whole, sprinkled on applesauce, or administered via nasogastric tube.

Difficulty swallowing affects approximately 30%-35% of long-term care residents, but the main alternative – crushing tablets – introduces risks of its own to the administration process.

This sprinkle is indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults, generalized anxiety disorder in patients aged 7 years and older, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain in adults, and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for these indications July 19, 2019.

It carries a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The most common adverse reactions (5% or more of treated participants and twice the incidence with placebo) were nausea, dry mouth, somnolence, constipation, decreased appetite, and hyperhidrosis. The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

[email protected]

Obesity ups type 2 diabetes risk far more than lifestyle, genetics

BARCELONA – Obesity, more so than having a poor lifestyle, significantly raised the odds of developing type 2 diabetes, independent of individuals’ genetic susceptibility, according to data from a Danish population-based, case-cohort study.

In fact, having a body mass index (BMI) of more than 30 kg/m2 was linked with a 480% risk of incident type 2 diabetes, compared with being of normal weight (BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2). The 95% confidence interval was 5.16-6.55. Being overweight (BMI, 25-29.9 kg/m2) also carried a 100% increased risk of type 2 diabetes (hazard ratio, 2.37; 95% CI, 2.15-2.62).

Having an unfavorable lifestyle – which was defined as having no or only one of several healthy-living characteristics, from not smoking and moderating alcohol use to eating a well-balanced, nutritious diet and exercising regularly – increased the risk of diabetes by 18%, compared with having a favorable lifestyle (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30).

Individuals with a high genetic risk score (GRS) had a 100% increased risk of developing the disease versus those with a low GRS (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3).

“High genetic risk, obesity, and [an] unfavorable lifestyle increase the individual-level risk of incident type 2 diabetes,” Hermina Jakupovic and associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Their results suggest that “the effect of obesity on type 2 diabetes risk is dominant over other risk factors, highlighting the importance of weight management in type 2 diabetes prevention.”

Ms. Jakupovic, a PhD student at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen, and coauthors examined data on 9,555 participants of the Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort, a large, prospective study that has been running since the early 1990s.

Around half of the study sample were women and the mean age was 52 years. Just over one-fifth (22.8%) were obese, 43% were overweight, and the remaining 35.2% were of normal weight. A quarter (25.4%) had an unfavorable lifestyle, 40% a favorable lifestyle, and the remainder an “intermediate” lifestyle. Over a follow-up of almost 15 years, nearly half (49.5%) developed type 2 diabetes.

Genetic risk was assessed by a GRS comprising 193 genetic variants known to be strongly associated with type 2 diabetes, Ms. Jakupovic explained, adding that, using the GRS, patients were categorized into being at low (the lowest 20%), intermediate (middle 60%) and high risk (top 20%) of type 2 diabetes.

Considering individuals’ GRS and lifestyle score together showed an increasing risk of developing type 2 diabetes from the low GRS/favorable-lifestyle category (HR, 1.0; reference) upward to the high GRS/unfavorable lifestyle (HR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.76-2.81).

The Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort is supported by the Danish Cancer Society. The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is an independent research center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Ms. Jakupovic and associates are funded either directly or indirectly by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

SOURCE: Jakupovic H et al. EASD 2019, Abstract 376.

BARCELONA – Obesity, more so than having a poor lifestyle, significantly raised the odds of developing type 2 diabetes, independent of individuals’ genetic susceptibility, according to data from a Danish population-based, case-cohort study.

In fact, having a body mass index (BMI) of more than 30 kg/m2 was linked with a 480% risk of incident type 2 diabetes, compared with being of normal weight (BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2). The 95% confidence interval was 5.16-6.55. Being overweight (BMI, 25-29.9 kg/m2) also carried a 100% increased risk of type 2 diabetes (hazard ratio, 2.37; 95% CI, 2.15-2.62).

Having an unfavorable lifestyle – which was defined as having no or only one of several healthy-living characteristics, from not smoking and moderating alcohol use to eating a well-balanced, nutritious diet and exercising regularly – increased the risk of diabetes by 18%, compared with having a favorable lifestyle (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30).

Individuals with a high genetic risk score (GRS) had a 100% increased risk of developing the disease versus those with a low GRS (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3).

“High genetic risk, obesity, and [an] unfavorable lifestyle increase the individual-level risk of incident type 2 diabetes,” Hermina Jakupovic and associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Their results suggest that “the effect of obesity on type 2 diabetes risk is dominant over other risk factors, highlighting the importance of weight management in type 2 diabetes prevention.”

Ms. Jakupovic, a PhD student at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen, and coauthors examined data on 9,555 participants of the Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort, a large, prospective study that has been running since the early 1990s.

Around half of the study sample were women and the mean age was 52 years. Just over one-fifth (22.8%) were obese, 43% were overweight, and the remaining 35.2% were of normal weight. A quarter (25.4%) had an unfavorable lifestyle, 40% a favorable lifestyle, and the remainder an “intermediate” lifestyle. Over a follow-up of almost 15 years, nearly half (49.5%) developed type 2 diabetes.

Genetic risk was assessed by a GRS comprising 193 genetic variants known to be strongly associated with type 2 diabetes, Ms. Jakupovic explained, adding that, using the GRS, patients were categorized into being at low (the lowest 20%), intermediate (middle 60%) and high risk (top 20%) of type 2 diabetes.

Considering individuals’ GRS and lifestyle score together showed an increasing risk of developing type 2 diabetes from the low GRS/favorable-lifestyle category (HR, 1.0; reference) upward to the high GRS/unfavorable lifestyle (HR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.76-2.81).

The Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort is supported by the Danish Cancer Society. The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is an independent research center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Ms. Jakupovic and associates are funded either directly or indirectly by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

SOURCE: Jakupovic H et al. EASD 2019, Abstract 376.

BARCELONA – Obesity, more so than having a poor lifestyle, significantly raised the odds of developing type 2 diabetes, independent of individuals’ genetic susceptibility, according to data from a Danish population-based, case-cohort study.

In fact, having a body mass index (BMI) of more than 30 kg/m2 was linked with a 480% risk of incident type 2 diabetes, compared with being of normal weight (BMI, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2). The 95% confidence interval was 5.16-6.55. Being overweight (BMI, 25-29.9 kg/m2) also carried a 100% increased risk of type 2 diabetes (hazard ratio, 2.37; 95% CI, 2.15-2.62).

Having an unfavorable lifestyle – which was defined as having no or only one of several healthy-living characteristics, from not smoking and moderating alcohol use to eating a well-balanced, nutritious diet and exercising regularly – increased the risk of diabetes by 18%, compared with having a favorable lifestyle (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.30).

Individuals with a high genetic risk score (GRS) had a 100% increased risk of developing the disease versus those with a low GRS (HR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3).

“High genetic risk, obesity, and [an] unfavorable lifestyle increase the individual-level risk of incident type 2 diabetes,” Hermina Jakupovic and associates reported in a poster presentation at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Their results suggest that “the effect of obesity on type 2 diabetes risk is dominant over other risk factors, highlighting the importance of weight management in type 2 diabetes prevention.”

Ms. Jakupovic, a PhD student at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research at the University of Copenhagen, and coauthors examined data on 9,555 participants of the Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort, a large, prospective study that has been running since the early 1990s.

Around half of the study sample were women and the mean age was 52 years. Just over one-fifth (22.8%) were obese, 43% were overweight, and the remaining 35.2% were of normal weight. A quarter (25.4%) had an unfavorable lifestyle, 40% a favorable lifestyle, and the remainder an “intermediate” lifestyle. Over a follow-up of almost 15 years, nearly half (49.5%) developed type 2 diabetes.

Genetic risk was assessed by a GRS comprising 193 genetic variants known to be strongly associated with type 2 diabetes, Ms. Jakupovic explained, adding that, using the GRS, patients were categorized into being at low (the lowest 20%), intermediate (middle 60%) and high risk (top 20%) of type 2 diabetes.

Considering individuals’ GRS and lifestyle score together showed an increasing risk of developing type 2 diabetes from the low GRS/favorable-lifestyle category (HR, 1.0; reference) upward to the high GRS/unfavorable lifestyle (HR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.76-2.81).

The Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort is supported by the Danish Cancer Society. The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is an independent research center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation. Ms. Jakupovic and associates are funded either directly or indirectly by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

SOURCE: Jakupovic H et al. EASD 2019, Abstract 376.

REPORTING FROM EASD 2019

Universal coverage may be possible without increases in national spending

The Commonwealth Fund and The Urban Institute looked at eight reform scenarios, including ones that build on the Affordable Care Act and expand to universal coverage or single payer. Two scenarios that continue to utilize private insurance show that, conceptually, broad coverage can be achieved without increasing spending.

“This study is important because it shows that there are several health reform approaches that have the potential to increase the number of people with health insurance, make health care more affordable, and slow cost growth,” David Blumenthal, MD, president of The Commonwealth Fund, said during an Oct. 15 conference call introducing the report.

He called the details that separate the varying models “central to the national debate on health care and health insurance coverage as the 2020 campaign season progresses.”

All the scenarios presented in the report have a foundation in various current Democratic health care reform proposals, although no one specific proposal or legislation is profiled within the eight scenarios presented.

“Our hope is that this extensive analysis will clarify for voters and policy makers the implications of the policy choices before us,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, the vice president of health care coverage and access at The Commonwealth Fund, during the call.

The first of these scenarios, dubbed “Universal Coverage I: Private and Public Options,” includes continued use of private insurance but also involves a public option and is the first of four options presented in the report to achieve universal coverage by actively enrolling people who are not enrolled in a private plan for one year in the public option with income-scaled premiums. This option would not utilize the ACA employer mandate and would remove the “firewall” that prevents individuals with access to employer-sponsored coverage from accessing financial assistance and seeking individual coverage from the insurance marketplace.

This scenario, as with all but one of the scenarios analyzed in the report, covers all essential benefits as defined in the Affordable Care Act. The only single-payer option that does not cover all of these essential benefits still provides coverage for medically necessary care, including dental, vision, hearing, and long-term services.

The Universal Coverage I scenario does not have any penalties for not carrying insurance, but all legal residents that forgo voluntary coverage from an employer or the marketplace will be automatically enrolled in coverage for which they are responsible for a premium payment.

There would be no expanded access to short-term, limited duration plans as the automatic enrollment to those not voluntarily covered by an employer or in the marketplace would make coverage universal. Federal government spending under this plan increases government health care spending in 2020 by $122.1 billion and $1.5 trillion over 10 years. However, total national spending in this scenario would decrease by $22.6 billion or 0.6% in 2020, compared with current law.

“Universal Coverage II: Enhanced Subsidies” is similar to Universal Coverage I in all other respects other than that it includes more generous premium and cost-sharing subsidies. These additional offerings would push federal government spending up $161.8 billion more in 2020, compared with current law, and to $2 trillion more over the next 10 years, while showing a minimal decrease in total national spending of less than 1% compared with current law.

The other two options that would move toward providing everyone with health insurance include a single payer system that covers all ACA essential health benefits, features no premiums, has income-related cost sharing, and covers all legal residents. Private insurance in this scenario is prohibited, and provider payments would be similar to those received in Medicare. Federal government spending would increase in 2020 by $1.5 trillion, compared with current law, and $17.6 trillion over the next 10 years. However, total national spending would decrease by $209.5 billion, or 6%, in 2020 compared with current law. These savings would come from lower provider payments and administrative costs that outweigh increased costs associated with near universal coverage and lower cost-sharing requirements.

A second single payer scenario broadens the benefits and would cover all residents in the United States, including undocumented residents. It would have no cost-sharing requirements.

The “optimal levels at which the payments for hospitals and doctors and other providers should be paid are really unknown at this time,” said Linda Blumberg, PhD, fellow at The Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center and one of the report authors, during the call.

Providing total coverage for all people in the United States is estimated to increase federal spending by $2.8 trillion in 2020 compared with current law, and $34 trillion over 10 years, with much of this increase accounted for by the shift in existing state and private spending to the federal government. At the same time, total national spending would increase by approximately $720 billion in 2020 compared with current law. Even though employer, household, and state spending would decrease, these savings would not be enough to offset increases in federal spending as well as the increased consumption of health care that comes with more generous benefits. The offsets from lower administrative costs and lower provider payments also would not offset higher spending.

The report only looks at health care spending and does not present any suggestions on revenue to offset the spending.

SOURCE: Blumberg LJ et al. “From Incremental to Comprehensive Health Insurance Reform: How Various Reform Options Compare On Coverage and Costs.” The Commonwealth Fund and The Urban Institute. 2019 Oct 16.

The Commonwealth Fund and The Urban Institute looked at eight reform scenarios, including ones that build on the Affordable Care Act and expand to universal coverage or single payer. Two scenarios that continue to utilize private insurance show that, conceptually, broad coverage can be achieved without increasing spending.

“This study is important because it shows that there are several health reform approaches that have the potential to increase the number of people with health insurance, make health care more affordable, and slow cost growth,” David Blumenthal, MD, president of The Commonwealth Fund, said during an Oct. 15 conference call introducing the report.

He called the details that separate the varying models “central to the national debate on health care and health insurance coverage as the 2020 campaign season progresses.”

All the scenarios presented in the report have a foundation in various current Democratic health care reform proposals, although no one specific proposal or legislation is profiled within the eight scenarios presented.

“Our hope is that this extensive analysis will clarify for voters and policy makers the implications of the policy choices before us,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, the vice president of health care coverage and access at The Commonwealth Fund, during the call.

The first of these scenarios, dubbed “Universal Coverage I: Private and Public Options,” includes continued use of private insurance but also involves a public option and is the first of four options presented in the report to achieve universal coverage by actively enrolling people who are not enrolled in a private plan for one year in the public option with income-scaled premiums. This option would not utilize the ACA employer mandate and would remove the “firewall” that prevents individuals with access to employer-sponsored coverage from accessing financial assistance and seeking individual coverage from the insurance marketplace.

This scenario, as with all but one of the scenarios analyzed in the report, covers all essential benefits as defined in the Affordable Care Act. The only single-payer option that does not cover all of these essential benefits still provides coverage for medically necessary care, including dental, vision, hearing, and long-term services.

The Universal Coverage I scenario does not have any penalties for not carrying insurance, but all legal residents that forgo voluntary coverage from an employer or the marketplace will be automatically enrolled in coverage for which they are responsible for a premium payment.

There would be no expanded access to short-term, limited duration plans as the automatic enrollment to those not voluntarily covered by an employer or in the marketplace would make coverage universal. Federal government spending under this plan increases government health care spending in 2020 by $122.1 billion and $1.5 trillion over 10 years. However, total national spending in this scenario would decrease by $22.6 billion or 0.6% in 2020, compared with current law.

“Universal Coverage II: Enhanced Subsidies” is similar to Universal Coverage I in all other respects other than that it includes more generous premium and cost-sharing subsidies. These additional offerings would push federal government spending up $161.8 billion more in 2020, compared with current law, and to $2 trillion more over the next 10 years, while showing a minimal decrease in total national spending of less than 1% compared with current law.

The other two options that would move toward providing everyone with health insurance include a single payer system that covers all ACA essential health benefits, features no premiums, has income-related cost sharing, and covers all legal residents. Private insurance in this scenario is prohibited, and provider payments would be similar to those received in Medicare. Federal government spending would increase in 2020 by $1.5 trillion, compared with current law, and $17.6 trillion over the next 10 years. However, total national spending would decrease by $209.5 billion, or 6%, in 2020 compared with current law. These savings would come from lower provider payments and administrative costs that outweigh increased costs associated with near universal coverage and lower cost-sharing requirements.

A second single payer scenario broadens the benefits and would cover all residents in the United States, including undocumented residents. It would have no cost-sharing requirements.

The “optimal levels at which the payments for hospitals and doctors and other providers should be paid are really unknown at this time,” said Linda Blumberg, PhD, fellow at The Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center and one of the report authors, during the call.

Providing total coverage for all people in the United States is estimated to increase federal spending by $2.8 trillion in 2020 compared with current law, and $34 trillion over 10 years, with much of this increase accounted for by the shift in existing state and private spending to the federal government. At the same time, total national spending would increase by approximately $720 billion in 2020 compared with current law. Even though employer, household, and state spending would decrease, these savings would not be enough to offset increases in federal spending as well as the increased consumption of health care that comes with more generous benefits. The offsets from lower administrative costs and lower provider payments also would not offset higher spending.

The report only looks at health care spending and does not present any suggestions on revenue to offset the spending.

SOURCE: Blumberg LJ et al. “From Incremental to Comprehensive Health Insurance Reform: How Various Reform Options Compare On Coverage and Costs.” The Commonwealth Fund and The Urban Institute. 2019 Oct 16.

The Commonwealth Fund and The Urban Institute looked at eight reform scenarios, including ones that build on the Affordable Care Act and expand to universal coverage or single payer. Two scenarios that continue to utilize private insurance show that, conceptually, broad coverage can be achieved without increasing spending.

“This study is important because it shows that there are several health reform approaches that have the potential to increase the number of people with health insurance, make health care more affordable, and slow cost growth,” David Blumenthal, MD, president of The Commonwealth Fund, said during an Oct. 15 conference call introducing the report.

He called the details that separate the varying models “central to the national debate on health care and health insurance coverage as the 2020 campaign season progresses.”

All the scenarios presented in the report have a foundation in various current Democratic health care reform proposals, although no one specific proposal or legislation is profiled within the eight scenarios presented.

“Our hope is that this extensive analysis will clarify for voters and policy makers the implications of the policy choices before us,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, the vice president of health care coverage and access at The Commonwealth Fund, during the call.

The first of these scenarios, dubbed “Universal Coverage I: Private and Public Options,” includes continued use of private insurance but also involves a public option and is the first of four options presented in the report to achieve universal coverage by actively enrolling people who are not enrolled in a private plan for one year in the public option with income-scaled premiums. This option would not utilize the ACA employer mandate and would remove the “firewall” that prevents individuals with access to employer-sponsored coverage from accessing financial assistance and seeking individual coverage from the insurance marketplace.

This scenario, as with all but one of the scenarios analyzed in the report, covers all essential benefits as defined in the Affordable Care Act. The only single-payer option that does not cover all of these essential benefits still provides coverage for medically necessary care, including dental, vision, hearing, and long-term services.

The Universal Coverage I scenario does not have any penalties for not carrying insurance, but all legal residents that forgo voluntary coverage from an employer or the marketplace will be automatically enrolled in coverage for which they are responsible for a premium payment.

There would be no expanded access to short-term, limited duration plans as the automatic enrollment to those not voluntarily covered by an employer or in the marketplace would make coverage universal. Federal government spending under this plan increases government health care spending in 2020 by $122.1 billion and $1.5 trillion over 10 years. However, total national spending in this scenario would decrease by $22.6 billion or 0.6% in 2020, compared with current law.

“Universal Coverage II: Enhanced Subsidies” is similar to Universal Coverage I in all other respects other than that it includes more generous premium and cost-sharing subsidies. These additional offerings would push federal government spending up $161.8 billion more in 2020, compared with current law, and to $2 trillion more over the next 10 years, while showing a minimal decrease in total national spending of less than 1% compared with current law.

The other two options that would move toward providing everyone with health insurance include a single payer system that covers all ACA essential health benefits, features no premiums, has income-related cost sharing, and covers all legal residents. Private insurance in this scenario is prohibited, and provider payments would be similar to those received in Medicare. Federal government spending would increase in 2020 by $1.5 trillion, compared with current law, and $17.6 trillion over the next 10 years. However, total national spending would decrease by $209.5 billion, or 6%, in 2020 compared with current law. These savings would come from lower provider payments and administrative costs that outweigh increased costs associated with near universal coverage and lower cost-sharing requirements.

A second single payer scenario broadens the benefits and would cover all residents in the United States, including undocumented residents. It would have no cost-sharing requirements.

The “optimal levels at which the payments for hospitals and doctors and other providers should be paid are really unknown at this time,” said Linda Blumberg, PhD, fellow at The Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center and one of the report authors, during the call.

Providing total coverage for all people in the United States is estimated to increase federal spending by $2.8 trillion in 2020 compared with current law, and $34 trillion over 10 years, with much of this increase accounted for by the shift in existing state and private spending to the federal government. At the same time, total national spending would increase by approximately $720 billion in 2020 compared with current law. Even though employer, household, and state spending would decrease, these savings would not be enough to offset increases in federal spending as well as the increased consumption of health care that comes with more generous benefits. The offsets from lower administrative costs and lower provider payments also would not offset higher spending.

The report only looks at health care spending and does not present any suggestions on revenue to offset the spending.

SOURCE: Blumberg LJ et al. “From Incremental to Comprehensive Health Insurance Reform: How Various Reform Options Compare On Coverage and Costs.” The Commonwealth Fund and The Urban Institute. 2019 Oct 16.

Health care stayed front and center at Democratic debate

This time, it wasn’t just about Medicare-for-all.

Voters got a better look at Democrats’ health care priorities on Tuesday, as

While the debate began on the topic of impeaching President Trump, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont soon steered the discussion back to kitchen-table issues.

“I think what would be a disaster, if the American people believe that all we were doing is taking on Trump,” he said. “We’re forgetting that 87 million Americans are uninsured or underinsured.”

That was only the beginning of a series of health care conversations that lasted through much of the three-hour debate.

With Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts polling in second place before the night began, she was pressed to offer more details about what Medicare-for-all would look like under her leadership – in particular, whether she would raise taxes to pay for it.

“I have made clear what my principles are here,” she said. “That is, costs will go up for the wealthy and for big corporations, and for hardworking, middle-class families, costs will go down.”

But Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., pushed back, pointing out that, unlike Sen. Sanders – who has said taxes would increase to pay for his universal health care plan – she had not actually said whether she would raise taxes.

“Your signature is to have a plan for everything, except this,” Mr. Buttigieg said. “No plan has been laid out to explain how a multitrillion-dollar hole in this plan that Sen. Warren is putting forward is supposed to get filled in.”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota challenged the practicality of focusing on such a sweeping overhaul as Medicare-for-all. She pushed her support for a public option and noted the importance of issues that get less attention, like long-term care.

“The difference between a plan and a pipe dream is something that you can actually get done,” Sen. Klobuchar said.

But Sen. Warren stood her ground. When she was studying bankruptcy as a professor at Harvard Law School, she said, she noticed that two out of three families that went bankrupt after a medical problem had health insurance. The problem is cost, she said: “That is why hardworking people go broke.”

The candidates also staked their claim on two issues that are critically important to Democratic voters: strengthening gun control measures and guaranteeing access to reproductive health care.

Former Vice President Joe Biden trumpeted his role in securing the now-lapsed assault weapons ban in 1994. Among others, Sen. Kamala Harris of California called for a “comprehensive” background check requirement and a ban on the importation of assault weapons.

And one by one, the candidates vowed to codify abortion access, especially in light of recent conservative attacks in a number of states on the premise of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say women will die because these Republican legislatures in these various states who are out of touch with America are telling women what to do with their bodies,” Sen. Harris said, a reference to crackdowns on abortion access in many Republican-controlled states.

After pointing out earlier in the evening that two Planned Parenthood clinics in Ohio recently closed because of a Trump administration policy change, Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey said he would create an office of reproductive freedom and reproductive rights in his White House.

“It’s an assault on the most fundamental ideal that human beings should control their own body,” Sen. Booker said.

And addressing the opioid crisis, blamed for lowering life expectancy in the United States, many of the candidates called outright for jailing the executives of opioid manufacturers, whom Sen. Harris called “nothing more than some high-level dope dealers.”

“The people who should pay for the treatment are the very people that got people hooked and killed them in the first place,” she said.

The evening was also Sen. Sanders’ first appearance on the debate stage since he had a heart attack and underwent heart surgery just weeks ago. Asked about his health, he seemed impatient: “I’m healthy. I’m feeling great,” Sen. Sanders said as he brought the conversation back to policy.

The debate took place in Westerville, Ohio, a traditionally conservative suburb of Columbus that had turned blue in recent years – a nod to Democrats’ hopes of winning with the support of suburban voters in 2020.

And with those 12 Democrats standing elbow-to-elbow, the debate hosted by CNN and the New York Times had an unusual distinction: the most candidates to ever appear onstage at a presidential debate.

The fifth Democratic debate is scheduled for Nov. 20. The Democratic National Committee plans to hold 12 primary debates in total.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

This time, it wasn’t just about Medicare-for-all.

Voters got a better look at Democrats’ health care priorities on Tuesday, as

While the debate began on the topic of impeaching President Trump, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont soon steered the discussion back to kitchen-table issues.

“I think what would be a disaster, if the American people believe that all we were doing is taking on Trump,” he said. “We’re forgetting that 87 million Americans are uninsured or underinsured.”

That was only the beginning of a series of health care conversations that lasted through much of the three-hour debate.

With Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts polling in second place before the night began, she was pressed to offer more details about what Medicare-for-all would look like under her leadership – in particular, whether she would raise taxes to pay for it.

“I have made clear what my principles are here,” she said. “That is, costs will go up for the wealthy and for big corporations, and for hardworking, middle-class families, costs will go down.”

But Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., pushed back, pointing out that, unlike Sen. Sanders – who has said taxes would increase to pay for his universal health care plan – she had not actually said whether she would raise taxes.

“Your signature is to have a plan for everything, except this,” Mr. Buttigieg said. “No plan has been laid out to explain how a multitrillion-dollar hole in this plan that Sen. Warren is putting forward is supposed to get filled in.”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota challenged the practicality of focusing on such a sweeping overhaul as Medicare-for-all. She pushed her support for a public option and noted the importance of issues that get less attention, like long-term care.

“The difference between a plan and a pipe dream is something that you can actually get done,” Sen. Klobuchar said.

But Sen. Warren stood her ground. When she was studying bankruptcy as a professor at Harvard Law School, she said, she noticed that two out of three families that went bankrupt after a medical problem had health insurance. The problem is cost, she said: “That is why hardworking people go broke.”

The candidates also staked their claim on two issues that are critically important to Democratic voters: strengthening gun control measures and guaranteeing access to reproductive health care.

Former Vice President Joe Biden trumpeted his role in securing the now-lapsed assault weapons ban in 1994. Among others, Sen. Kamala Harris of California called for a “comprehensive” background check requirement and a ban on the importation of assault weapons.

And one by one, the candidates vowed to codify abortion access, especially in light of recent conservative attacks in a number of states on the premise of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say women will die because these Republican legislatures in these various states who are out of touch with America are telling women what to do with their bodies,” Sen. Harris said, a reference to crackdowns on abortion access in many Republican-controlled states.

After pointing out earlier in the evening that two Planned Parenthood clinics in Ohio recently closed because of a Trump administration policy change, Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey said he would create an office of reproductive freedom and reproductive rights in his White House.

“It’s an assault on the most fundamental ideal that human beings should control their own body,” Sen. Booker said.

And addressing the opioid crisis, blamed for lowering life expectancy in the United States, many of the candidates called outright for jailing the executives of opioid manufacturers, whom Sen. Harris called “nothing more than some high-level dope dealers.”

“The people who should pay for the treatment are the very people that got people hooked and killed them in the first place,” she said.

The evening was also Sen. Sanders’ first appearance on the debate stage since he had a heart attack and underwent heart surgery just weeks ago. Asked about his health, he seemed impatient: “I’m healthy. I’m feeling great,” Sen. Sanders said as he brought the conversation back to policy.

The debate took place in Westerville, Ohio, a traditionally conservative suburb of Columbus that had turned blue in recent years – a nod to Democrats’ hopes of winning with the support of suburban voters in 2020.

And with those 12 Democrats standing elbow-to-elbow, the debate hosted by CNN and the New York Times had an unusual distinction: the most candidates to ever appear onstage at a presidential debate.

The fifth Democratic debate is scheduled for Nov. 20. The Democratic National Committee plans to hold 12 primary debates in total.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

This time, it wasn’t just about Medicare-for-all.

Voters got a better look at Democrats’ health care priorities on Tuesday, as

While the debate began on the topic of impeaching President Trump, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont soon steered the discussion back to kitchen-table issues.

“I think what would be a disaster, if the American people believe that all we were doing is taking on Trump,” he said. “We’re forgetting that 87 million Americans are uninsured or underinsured.”

That was only the beginning of a series of health care conversations that lasted through much of the three-hour debate.

With Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts polling in second place before the night began, she was pressed to offer more details about what Medicare-for-all would look like under her leadership – in particular, whether she would raise taxes to pay for it.

“I have made clear what my principles are here,” she said. “That is, costs will go up for the wealthy and for big corporations, and for hardworking, middle-class families, costs will go down.”

But Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., pushed back, pointing out that, unlike Sen. Sanders – who has said taxes would increase to pay for his universal health care plan – she had not actually said whether she would raise taxes.

“Your signature is to have a plan for everything, except this,” Mr. Buttigieg said. “No plan has been laid out to explain how a multitrillion-dollar hole in this plan that Sen. Warren is putting forward is supposed to get filled in.”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota challenged the practicality of focusing on such a sweeping overhaul as Medicare-for-all. She pushed her support for a public option and noted the importance of issues that get less attention, like long-term care.

“The difference between a plan and a pipe dream is something that you can actually get done,” Sen. Klobuchar said.

But Sen. Warren stood her ground. When she was studying bankruptcy as a professor at Harvard Law School, she said, she noticed that two out of three families that went bankrupt after a medical problem had health insurance. The problem is cost, she said: “That is why hardworking people go broke.”

The candidates also staked their claim on two issues that are critically important to Democratic voters: strengthening gun control measures and guaranteeing access to reproductive health care.

Former Vice President Joe Biden trumpeted his role in securing the now-lapsed assault weapons ban in 1994. Among others, Sen. Kamala Harris of California called for a “comprehensive” background check requirement and a ban on the importation of assault weapons.

And one by one, the candidates vowed to codify abortion access, especially in light of recent conservative attacks in a number of states on the premise of the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say women will die because these Republican legislatures in these various states who are out of touch with America are telling women what to do with their bodies,” Sen. Harris said, a reference to crackdowns on abortion access in many Republican-controlled states.

After pointing out earlier in the evening that two Planned Parenthood clinics in Ohio recently closed because of a Trump administration policy change, Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey said he would create an office of reproductive freedom and reproductive rights in his White House.

“It’s an assault on the most fundamental ideal that human beings should control their own body,” Sen. Booker said.

And addressing the opioid crisis, blamed for lowering life expectancy in the United States, many of the candidates called outright for jailing the executives of opioid manufacturers, whom Sen. Harris called “nothing more than some high-level dope dealers.”

“The people who should pay for the treatment are the very people that got people hooked and killed them in the first place,” she said.

The evening was also Sen. Sanders’ first appearance on the debate stage since he had a heart attack and underwent heart surgery just weeks ago. Asked about his health, he seemed impatient: “I’m healthy. I’m feeling great,” Sen. Sanders said as he brought the conversation back to policy.

The debate took place in Westerville, Ohio, a traditionally conservative suburb of Columbus that had turned blue in recent years – a nod to Democrats’ hopes of winning with the support of suburban voters in 2020.

And with those 12 Democrats standing elbow-to-elbow, the debate hosted by CNN and the New York Times had an unusual distinction: the most candidates to ever appear onstage at a presidential debate.

The fifth Democratic debate is scheduled for Nov. 20. The Democratic National Committee plans to hold 12 primary debates in total.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Minimize blood pressure peaks, variability after stroke reperfusion

ST. LOUIS – Albuquerque. Investigators found that every 10–mm Hg increase in peak systolic pressure boosted the risk of in-hospital death 24% (P = .01) and reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a inpatient rehabilitation facility 13% (P = .03). Results were even stronger for peak mean arterial pressure, at 76% (P = .01) and 29% (P = .04), respectively; trends in the same direction for peak diastolic pressure were not statistically significant.

Also, every 10–mm Hg increase in blood pressure variability again increased the risk of dying in the hospital, whether it was systolic (33%; P = .002), diastolic (33%; P = .03), or mean arterial pressure variability (58%; P = .02). Higher variability also reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a rehab 10%-20%, but the findings, although close, were not statistically significant.

Neurologists generally do what they can to control blood pressure after stroke, and the study confirms the need to do that. What’s new is that the work was limited to reperfusion patients – intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase in 83.5%, mechanical thrombectomy in 60%, with some having both – which has not been the specific focus of much research.

“Be much more aggressive in terms of making sure the variability is limited and limiting the peaks,” especially within 24 hours of reperfusion, said lead investigator and stroke neurologist Dinesh Jillella, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “We want to be much more aggressive [with these patients]; it might limit our worse outcomes,” Dr. Jillella said. He conducted the review while in training at the University of New Mexico.

What led to the study is that Dr. Jillella and colleagues noticed that similar reperfusion patients can have very different outcomes, and he wanted to find modifiable risk factors that could account for the differences. The study did not address why high peaks and variability lead to worse outcomes, but he said hemorrhagic conversion might play a role.

It is also possible that higher pressures could be a marker of bad outcomes, as opposed to a direct cause, but the findings were adjusted for two significant confounders: age and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, which were both significantly higher in patients who did not do well. But after adjustment, “we [still] found an independent association with blood pressures and worse outcomes,” he said.

Higher peak systolic pressures and variability were also associated with about a 15% lower odds of leaving the hospital with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less, which means the patient has some moderate disability but is still able to walk without assistance.

Patients were 69 years old on average, and about 60% were men. The majority were white. About a third had a modified Rankin Scale score at or below 3 at discharge, and about two-thirds were discharged home or to a rehabilitation facility; 17% of patients died in the hospital.

Differences in antihypertensive regimens were not associated with outcomes on univariate analysis. Dr. Jillella said that, ideally, he would like to run a multicenter, prospective trial of blood pressure reduction targets after reperfusion.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Jillella didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

ST. LOUIS – Albuquerque. Investigators found that every 10–mm Hg increase in peak systolic pressure boosted the risk of in-hospital death 24% (P = .01) and reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a inpatient rehabilitation facility 13% (P = .03). Results were even stronger for peak mean arterial pressure, at 76% (P = .01) and 29% (P = .04), respectively; trends in the same direction for peak diastolic pressure were not statistically significant.

Also, every 10–mm Hg increase in blood pressure variability again increased the risk of dying in the hospital, whether it was systolic (33%; P = .002), diastolic (33%; P = .03), or mean arterial pressure variability (58%; P = .02). Higher variability also reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a rehab 10%-20%, but the findings, although close, were not statistically significant.

Neurologists generally do what they can to control blood pressure after stroke, and the study confirms the need to do that. What’s new is that the work was limited to reperfusion patients – intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase in 83.5%, mechanical thrombectomy in 60%, with some having both – which has not been the specific focus of much research.

“Be much more aggressive in terms of making sure the variability is limited and limiting the peaks,” especially within 24 hours of reperfusion, said lead investigator and stroke neurologist Dinesh Jillella, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “We want to be much more aggressive [with these patients]; it might limit our worse outcomes,” Dr. Jillella said. He conducted the review while in training at the University of New Mexico.

What led to the study is that Dr. Jillella and colleagues noticed that similar reperfusion patients can have very different outcomes, and he wanted to find modifiable risk factors that could account for the differences. The study did not address why high peaks and variability lead to worse outcomes, but he said hemorrhagic conversion might play a role.

It is also possible that higher pressures could be a marker of bad outcomes, as opposed to a direct cause, but the findings were adjusted for two significant confounders: age and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, which were both significantly higher in patients who did not do well. But after adjustment, “we [still] found an independent association with blood pressures and worse outcomes,” he said.

Higher peak systolic pressures and variability were also associated with about a 15% lower odds of leaving the hospital with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less, which means the patient has some moderate disability but is still able to walk without assistance.

Patients were 69 years old on average, and about 60% were men. The majority were white. About a third had a modified Rankin Scale score at or below 3 at discharge, and about two-thirds were discharged home or to a rehabilitation facility; 17% of patients died in the hospital.

Differences in antihypertensive regimens were not associated with outcomes on univariate analysis. Dr. Jillella said that, ideally, he would like to run a multicenter, prospective trial of blood pressure reduction targets after reperfusion.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Jillella didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

ST. LOUIS – Albuquerque. Investigators found that every 10–mm Hg increase in peak systolic pressure boosted the risk of in-hospital death 24% (P = .01) and reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a inpatient rehabilitation facility 13% (P = .03). Results were even stronger for peak mean arterial pressure, at 76% (P = .01) and 29% (P = .04), respectively; trends in the same direction for peak diastolic pressure were not statistically significant.

Also, every 10–mm Hg increase in blood pressure variability again increased the risk of dying in the hospital, whether it was systolic (33%; P = .002), diastolic (33%; P = .03), or mean arterial pressure variability (58%; P = .02). Higher variability also reduced the chance of being discharged home or to a rehab 10%-20%, but the findings, although close, were not statistically significant.

Neurologists generally do what they can to control blood pressure after stroke, and the study confirms the need to do that. What’s new is that the work was limited to reperfusion patients – intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase in 83.5%, mechanical thrombectomy in 60%, with some having both – which has not been the specific focus of much research.

“Be much more aggressive in terms of making sure the variability is limited and limiting the peaks,” especially within 24 hours of reperfusion, said lead investigator and stroke neurologist Dinesh Jillella, MD, of Emory University, Atlanta, at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “We want to be much more aggressive [with these patients]; it might limit our worse outcomes,” Dr. Jillella said. He conducted the review while in training at the University of New Mexico.

What led to the study is that Dr. Jillella and colleagues noticed that similar reperfusion patients can have very different outcomes, and he wanted to find modifiable risk factors that could account for the differences. The study did not address why high peaks and variability lead to worse outcomes, but he said hemorrhagic conversion might play a role.

It is also possible that higher pressures could be a marker of bad outcomes, as opposed to a direct cause, but the findings were adjusted for two significant confounders: age and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, which were both significantly higher in patients who did not do well. But after adjustment, “we [still] found an independent association with blood pressures and worse outcomes,” he said.

Higher peak systolic pressures and variability were also associated with about a 15% lower odds of leaving the hospital with a modified Rankin Scale score of 3 or less, which means the patient has some moderate disability but is still able to walk without assistance.

Patients were 69 years old on average, and about 60% were men. The majority were white. About a third had a modified Rankin Scale score at or below 3 at discharge, and about two-thirds were discharged home or to a rehabilitation facility; 17% of patients died in the hospital.

Differences in antihypertensive regimens were not associated with outcomes on univariate analysis. Dr. Jillella said that, ideally, he would like to run a multicenter, prospective trial of blood pressure reduction targets after reperfusion.

There was no external funding, and Dr. Jillella didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2019

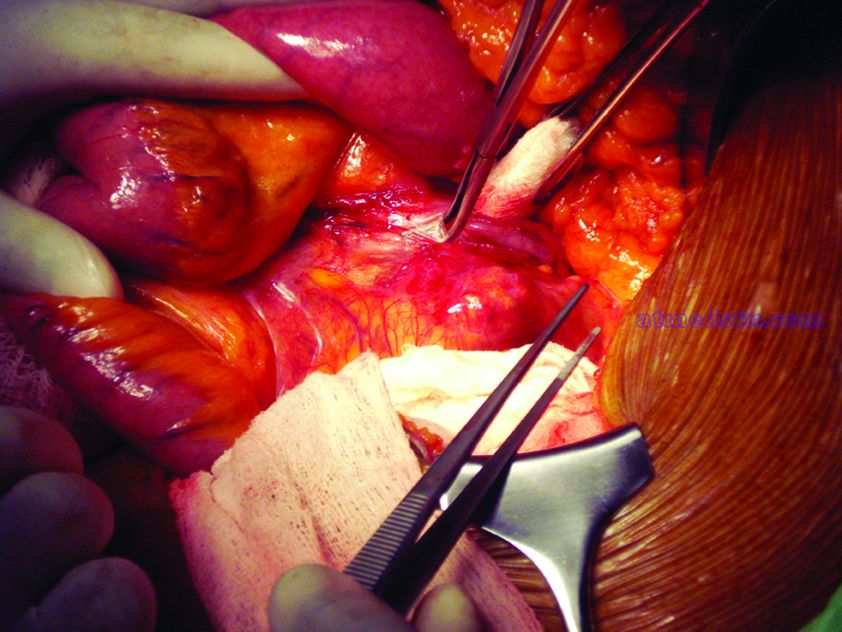

What repair is best for juxtarenal aneurysm?

CHICAGO – Outcomes with fenestrated endografts and endograft anchors to repair abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) in the region of the renal artery have improved as the techniques have gained popularity in recent years, but open repair may still achieve better overall results, vascular surgeons on opposite sides of the controversy contended during a debate at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgery Society.

Fenestrated endovascular aortic repair (FEVAR) “is as safe as open surgery to treat complex aneurysm,” said Carlos Bechara, MD, of Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago. “EndoAnchors [Medtronic] do provide an excellent off-the-shelf solution to treat short, hostile necks with promising short-term results.”

Arguing for open repair was Paul DiMusto, MD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “Open repair has an equal perioperative mortality to FEVAR,” Dr. DiMusto said, adding that the open approach also has a higher long-term branch patency rate, lower secondary-intervention rate, a lower incidence of long-term renal failure, and higher long-term survival. “So putting that all together, open repair is best,” he said.

They staked out their positions by citing a host of published trials.

“The presence of a short neck can create a challenging clinical scenario for an endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm,” Dr. Bechara said. However, he noted he was discussing complex aneurysm in which the aortic clamp is placed above the renal arteries, differentiating it from infrarenal AAA in which the clamp is below the renal arteries with no renal ischemia time. He noted a 2011 study that determined a short neck was a predictor of Type 1A endoleak after AAA repair, but that compliance with best practices at the time was poor; more than 44% of EVARs did not follow the manufacturer’s instruction (Circulation. 2011;123:2848-55).

But FEVAR was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012, with an indication for an infrarenal neck length of 4-14 mm, Dr. Bechara noted. Since then, several studies have reported excellent outcomes with the technique. An early small study of 67 patients reported a 100% technical success rate with one patient having a Type 1 endoleak at 3 years (J Vasc Surg. 2014;60:1420-8).

This year, a larger study evaluated 6,825 patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program who had FEVAR, open AAA repair or standard infrarenal endovascular repair during 2012-2016. “Actually, the fenestrated approach had fewer complications than open repair and the outcomes were comparable to standard EVAR,” Dr. Bechara noted. The trial reported FEVAR had lower rates of perioperative mortality (1.8% vs. 8.8%; P = .001), postoperative renal dysfunction (1.4% vs. 7.7%; P = .002), and overall complications (11% vs. 33%; P less than.001) than did open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2019;69:1670-78).

In regard to the use of endograft anchors for treatment of endoleaks, migrating grafts, and high-risk seal zones, Dr. Bechara noted they are a good “off-the-shelf” choice for complex AAA repair. He cited current results of a cohort of 70 patients with short-neck AAA (J Vasc Surg. 2019;70:732-40). “This study showed a procedural success rate at 97% and a technical success rate at 88.6%,” he said. “They had no stent migration, no increase in sac size or AAA rupture or open conversion.”

He also pointed to just-published results from a randomized trial of 881 patients with up to 14 years of follow-up that found comparable rates of death/secondary procedures, as well as durability, between patients who had endovascular and open repairs (77.7% and 75.5%, respectively, N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2126-35). Also, he noted that hospital volume is an important predictor of success with open repair, with high-volume centers reporting lower mortality (3.9%) than low-volume centers (9%; Ann Surg. 2018 Nov 29. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002873). “So not many centers are doing high-volume open aortic surgery,” he said.

To make his case that open surgery for juxtarenal AAAs is superior, Dr. DiMusto cited a number of recent studies, including a three-center trial of 200 patients who had open and FEVAR procedures (J Endovasc Ther. 2019;26:105-12). “There was no difference in perioperative mortality [2.2% for FEVAR, 1.9% in open repair], ” Dr. DiMusto said “There was a higher freedom from reintervention in the open group [96% vs. 78%], and there was higher long-term vessel patency in the open group” (97.5% having target patency for open vs. 93.3% for FEVAR).

He also pointed to a meta-analysis of 2,326 patients that found similar outcomes for mortality and postoperative renal insufficiency between FEVAR and open repair, around 4.1%, but showed significantly higher rates of renal failure in FEVAR, at 19.7% versus 7.7% (J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:242-55). This study also reported significantly more secondary interventions with FEVAR, 12.7% vs. 4.9%, Dr. DiMusto said.

Another study of 3,253 complex AAA repairs, including 887 FEVAR and 2,125 open procedures, showed that FEVAR had a technical success rate of 97%, with no appreciable difference in perioperative mortality between the two procedures (Ann Surg. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003094).