User login

Purpuric Lesions on the Leg

THE DIAGNOSIS: Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

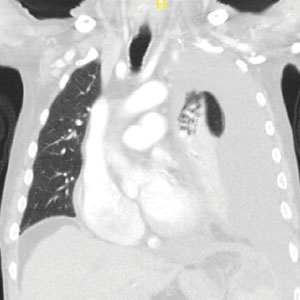

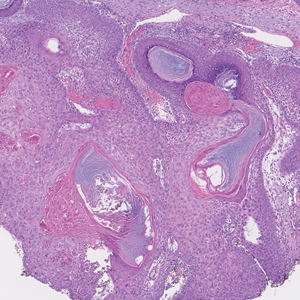

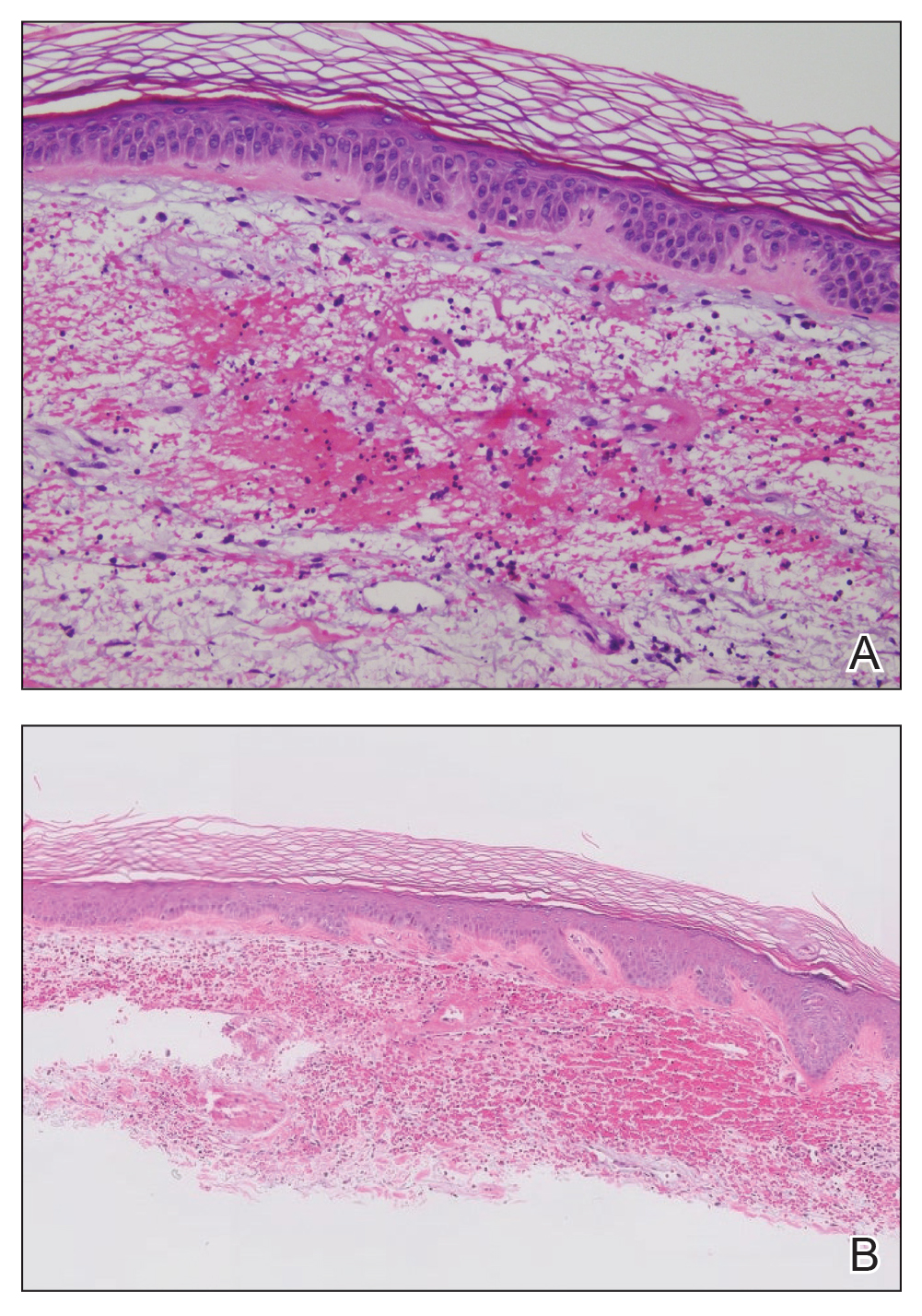

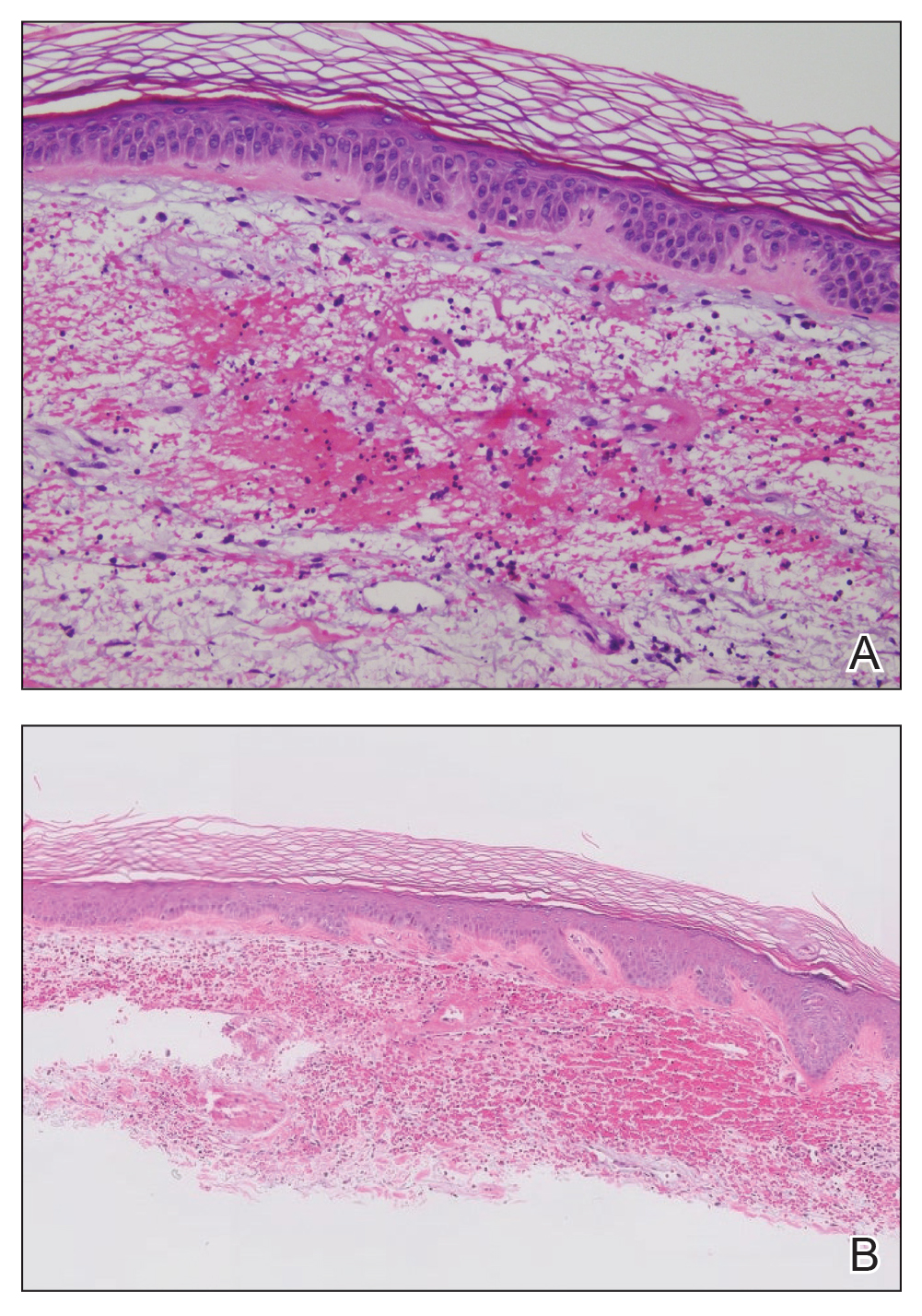

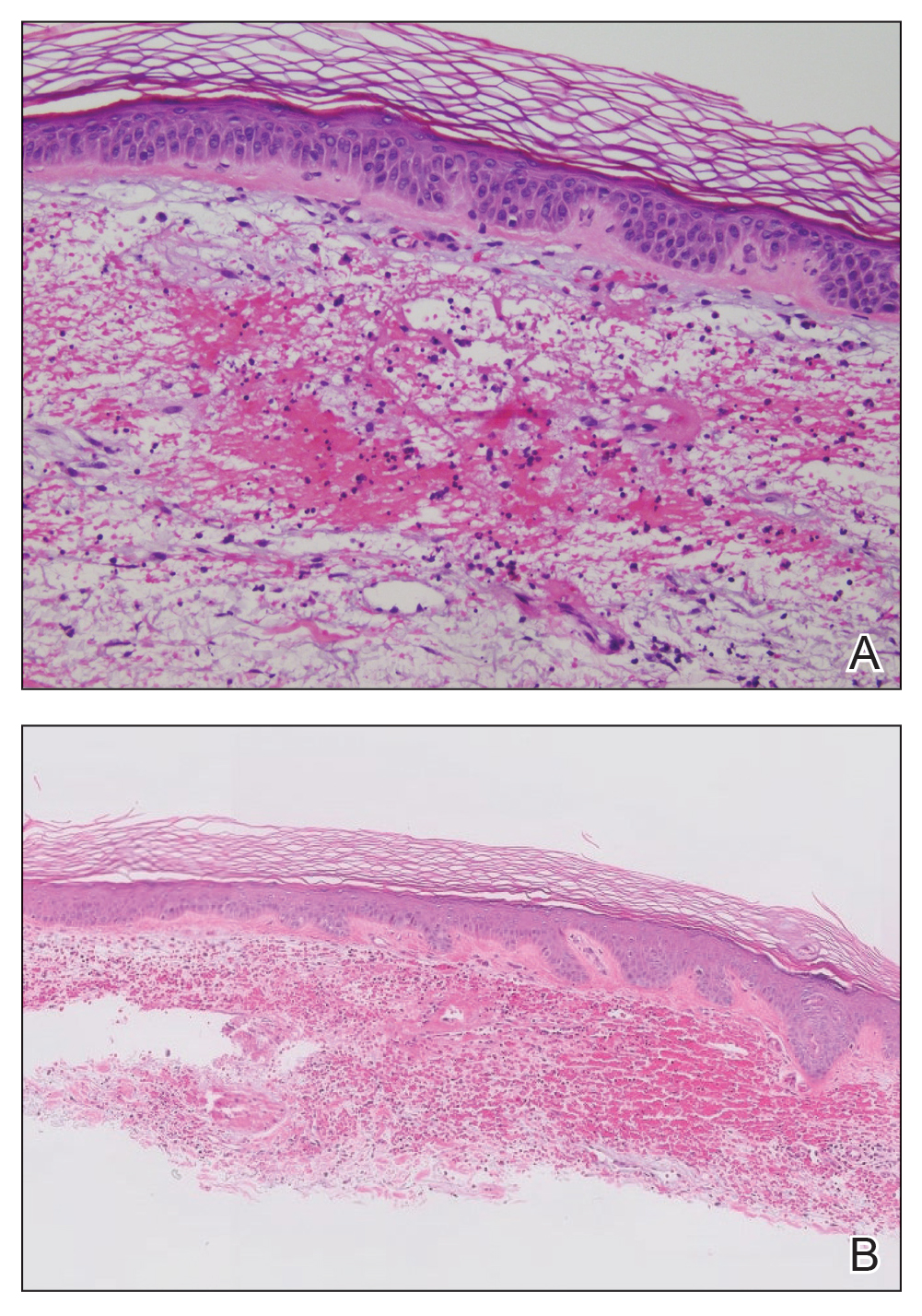

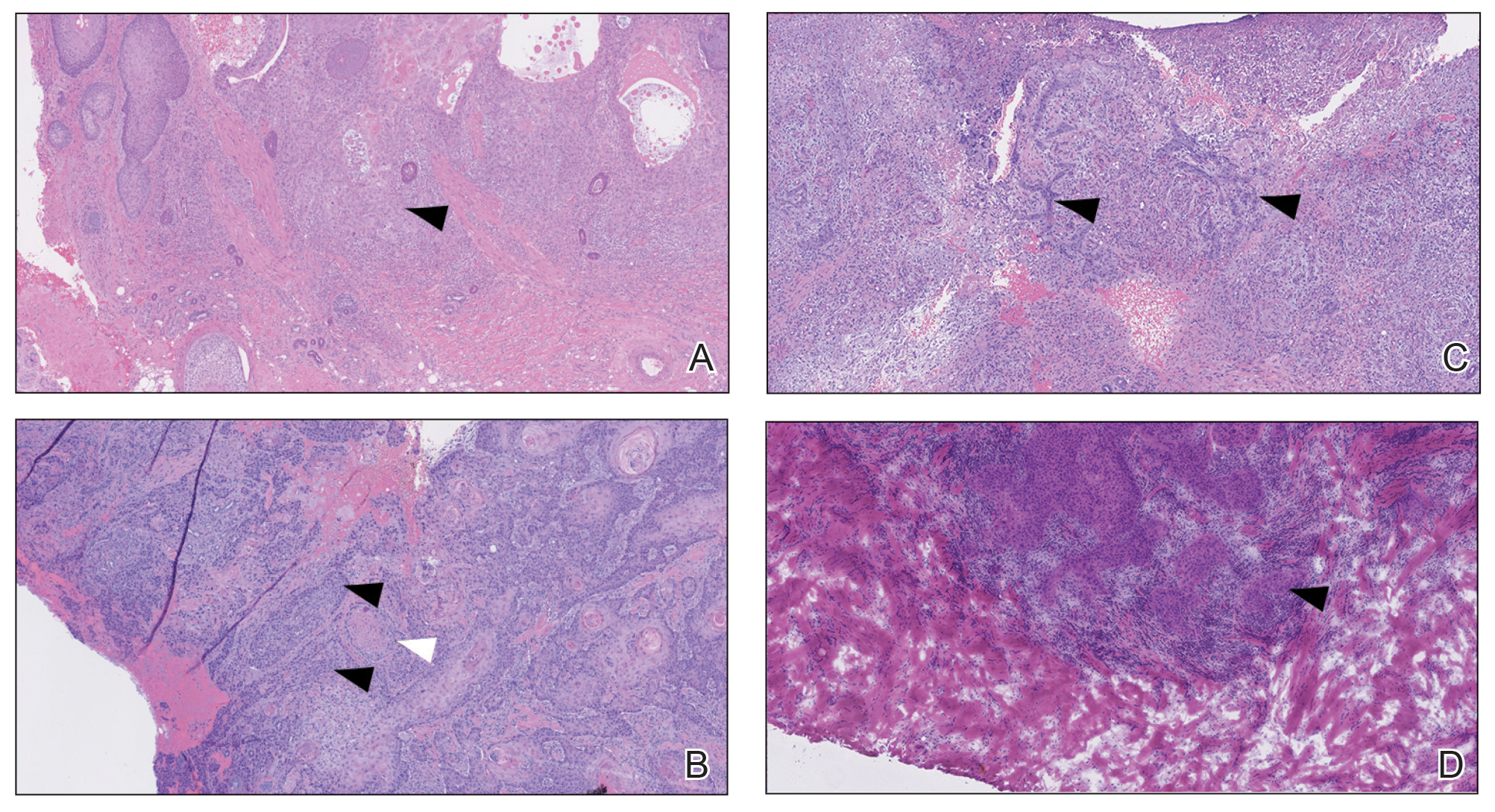

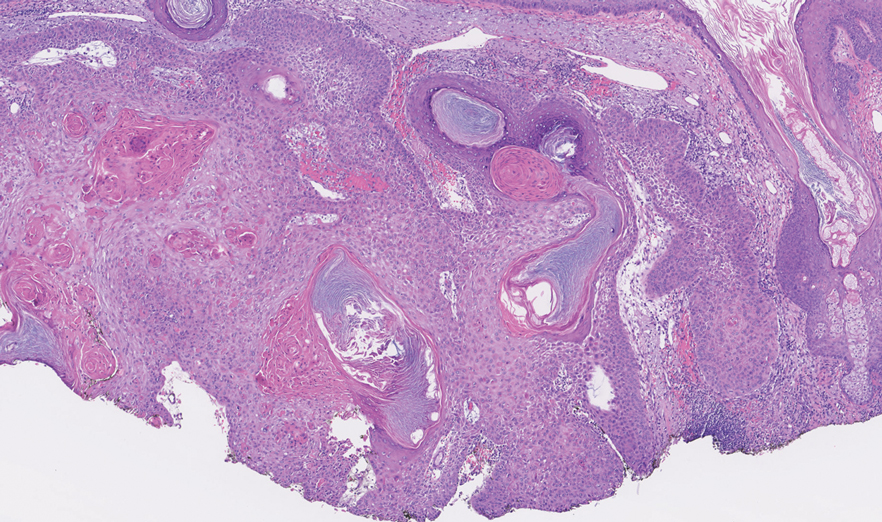

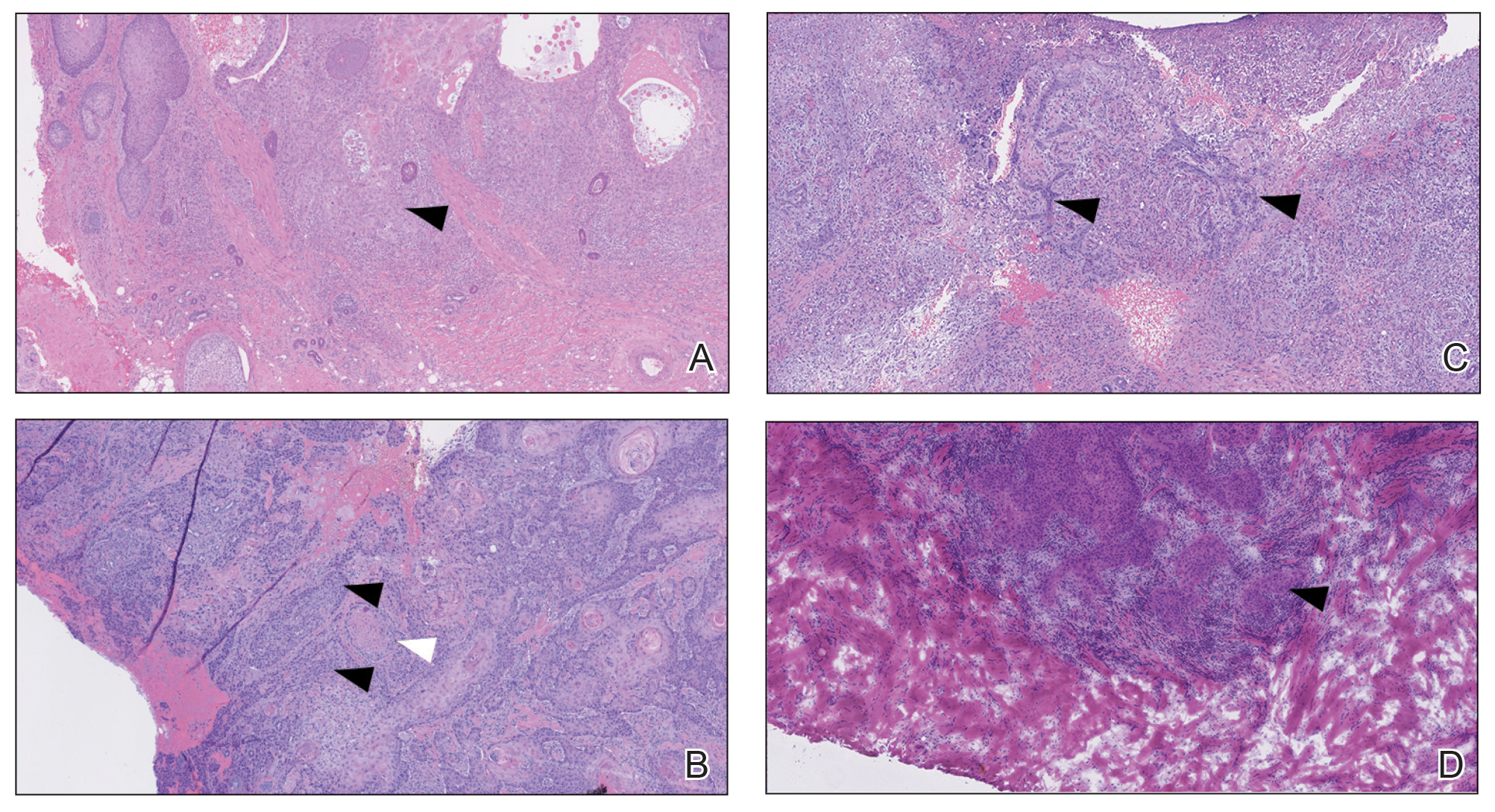

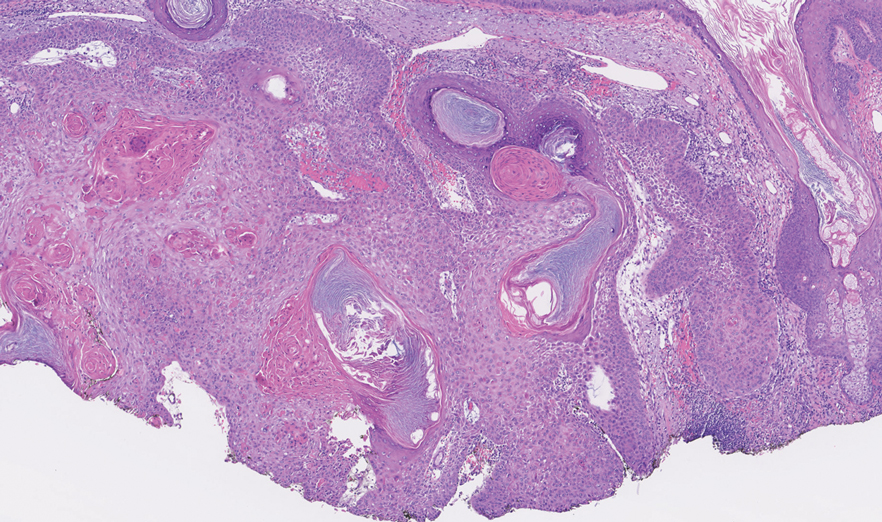

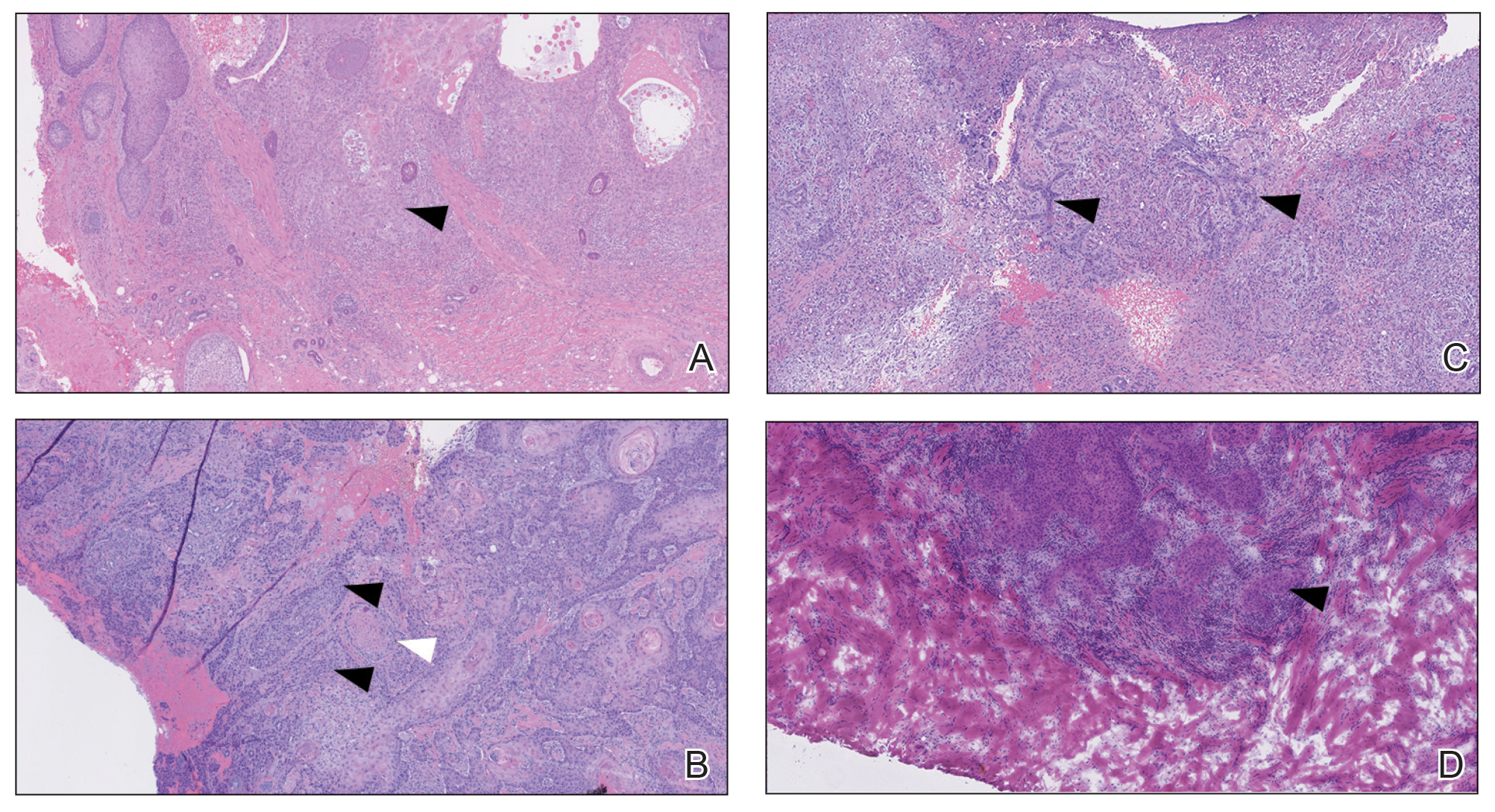

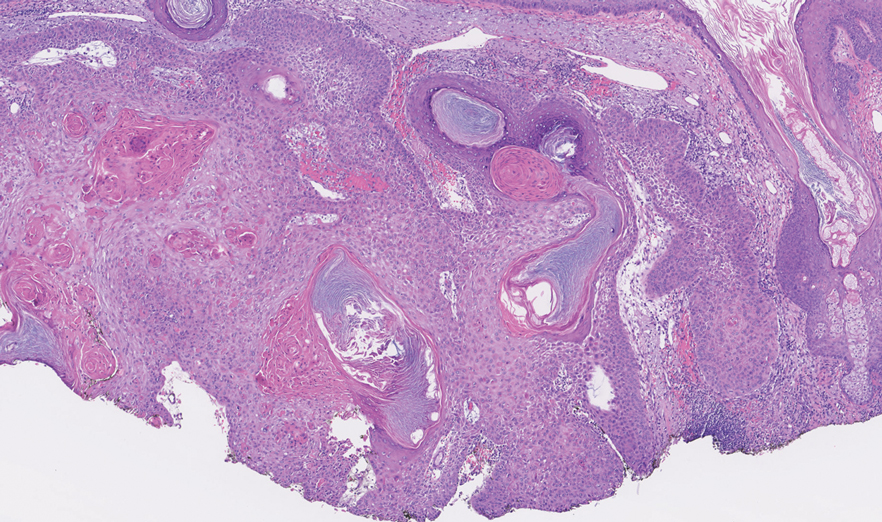

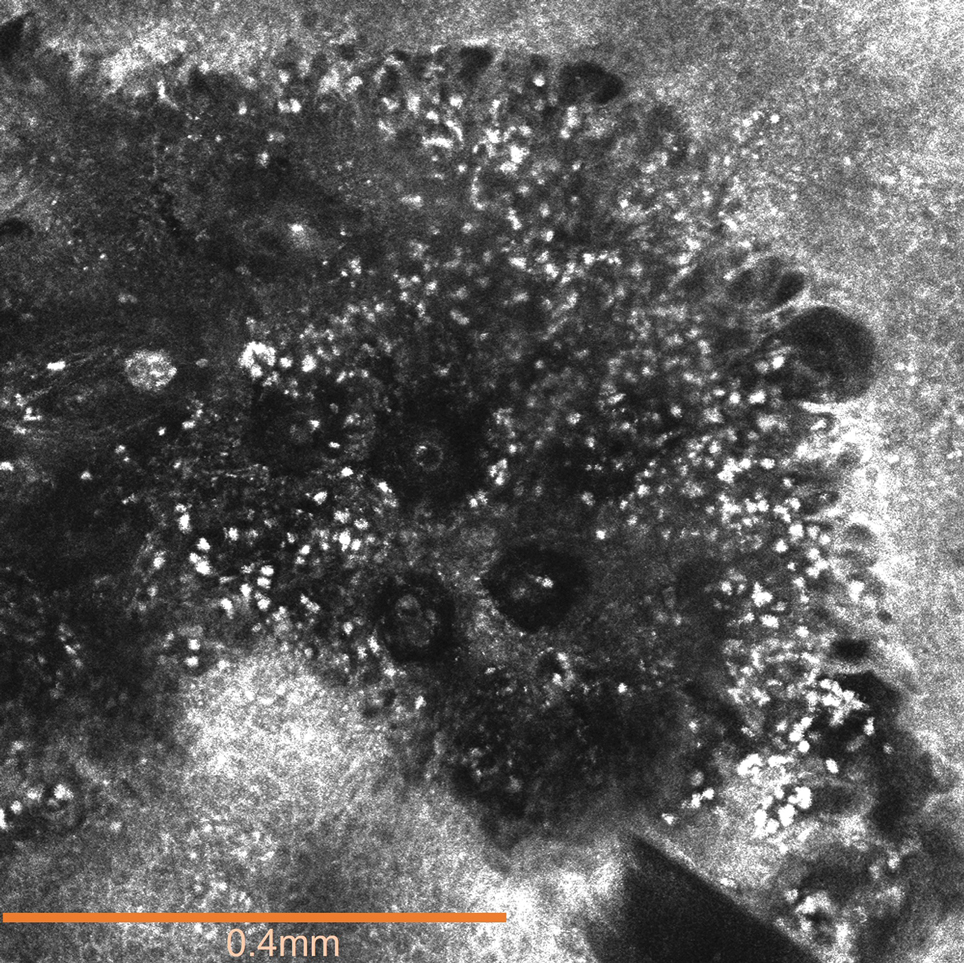

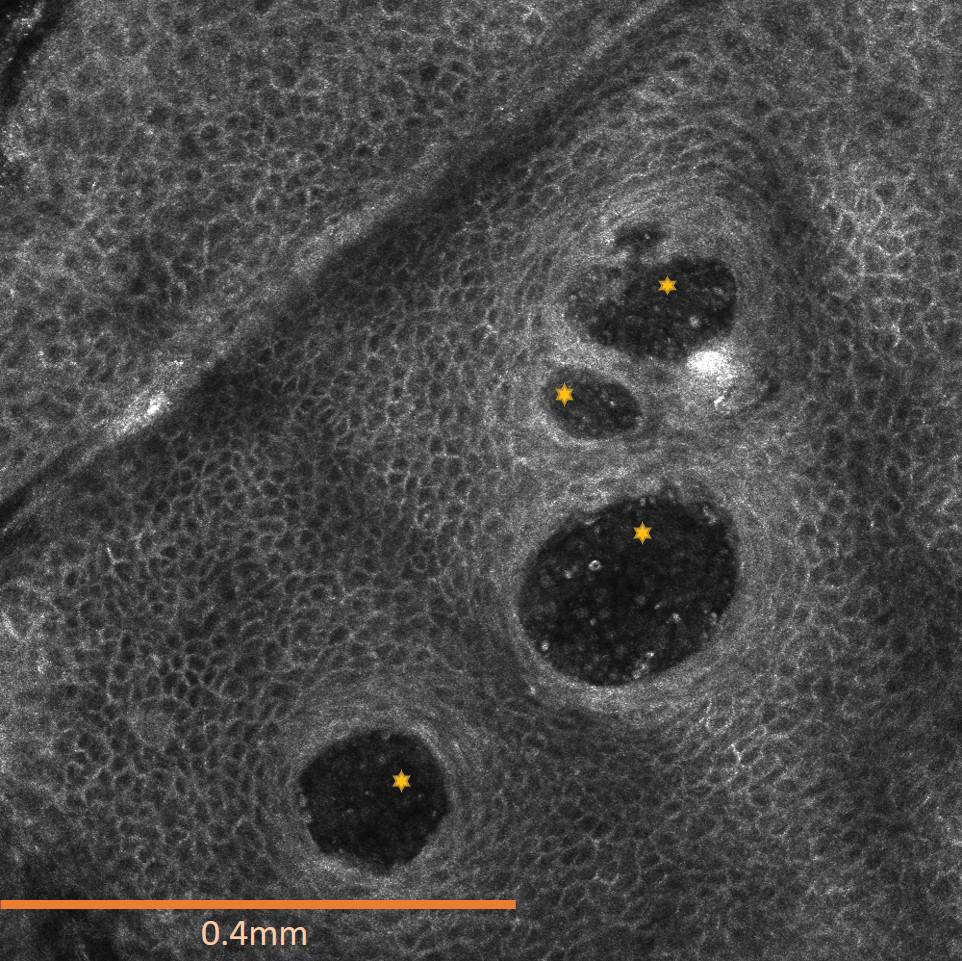

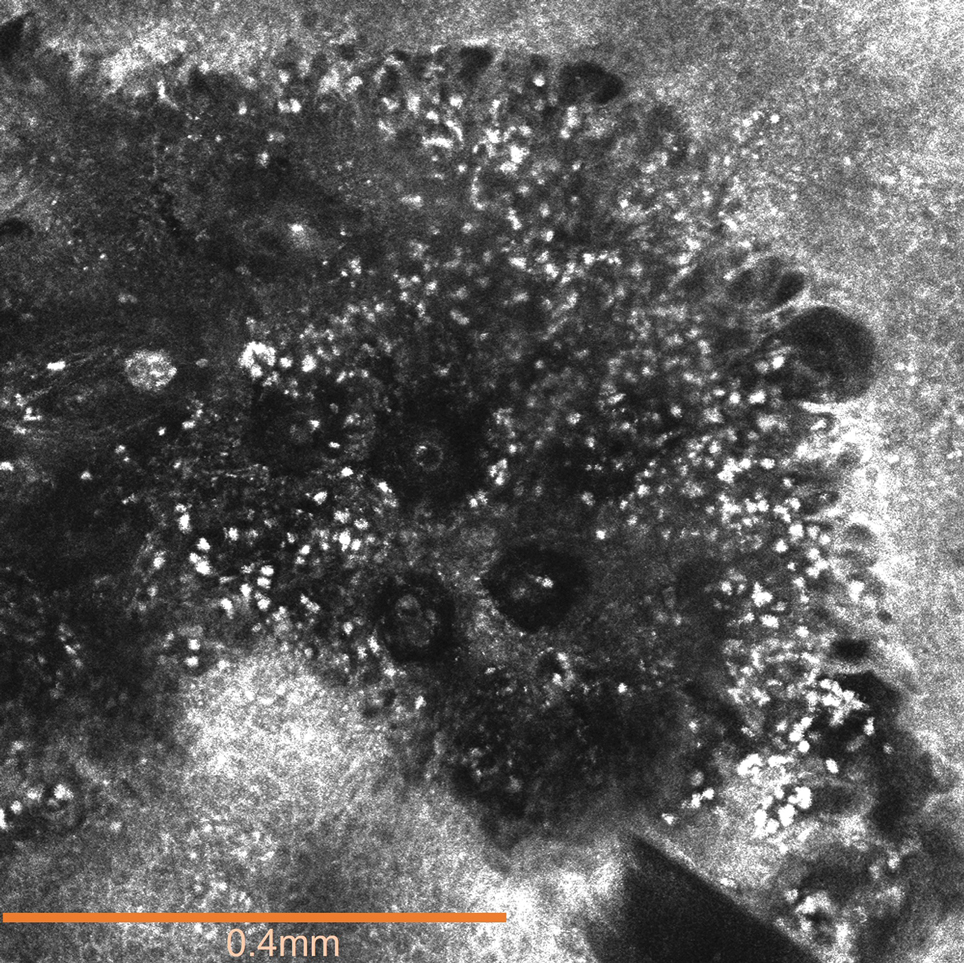

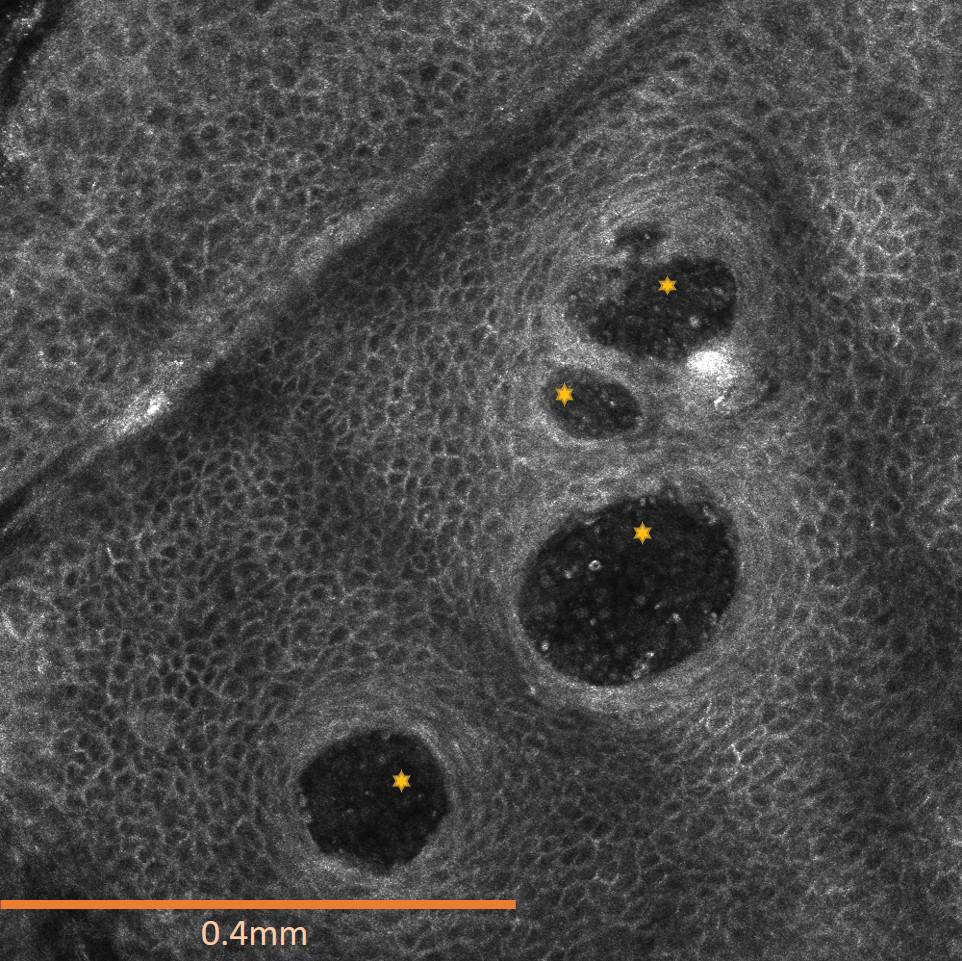

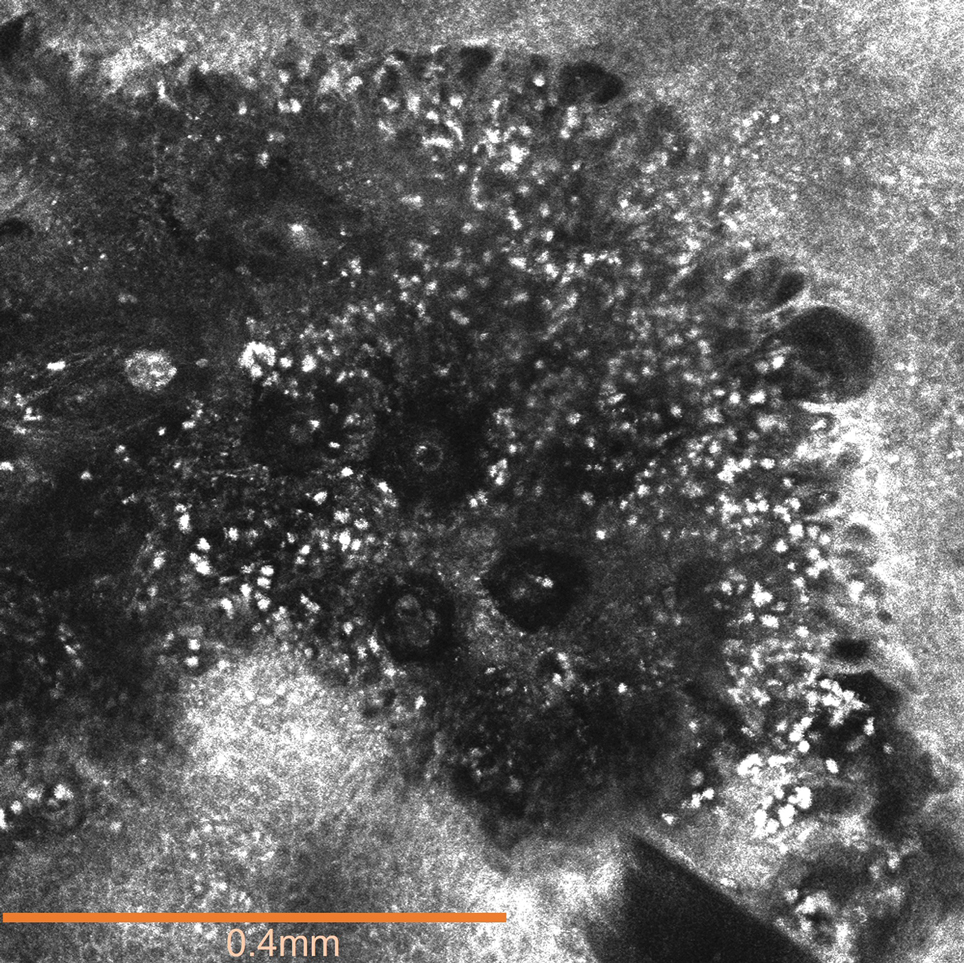

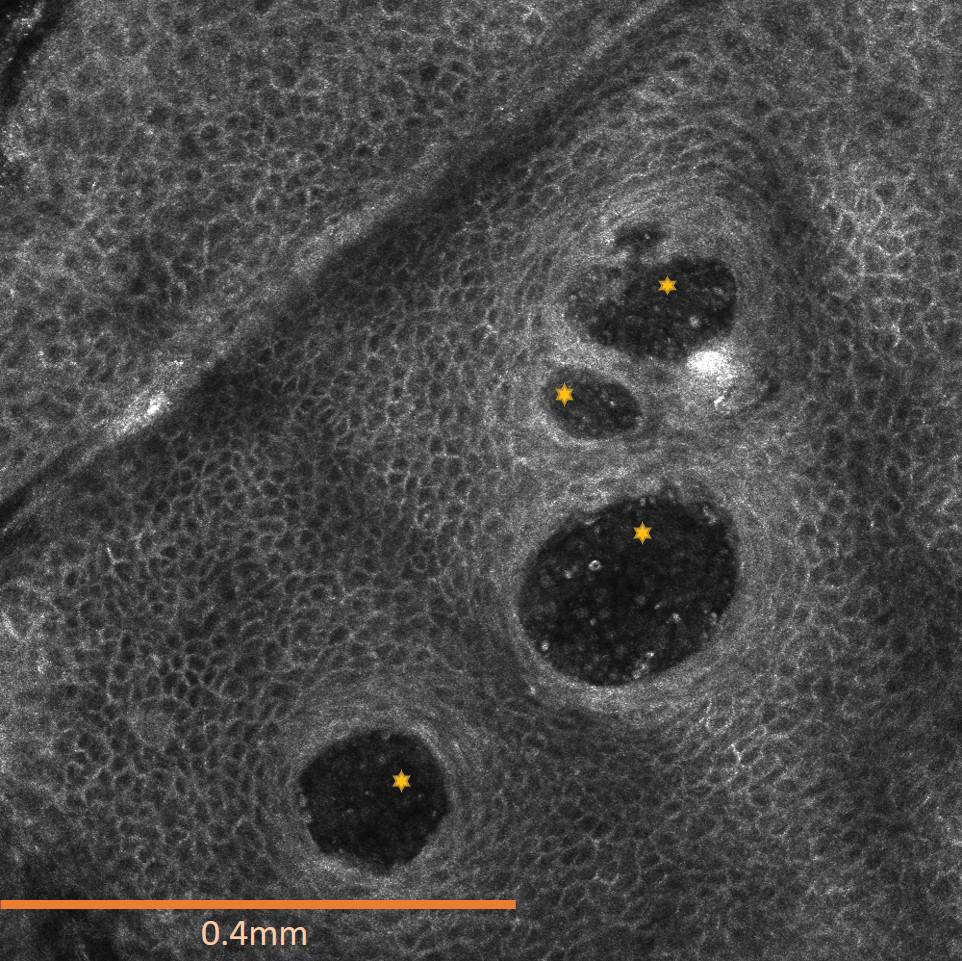

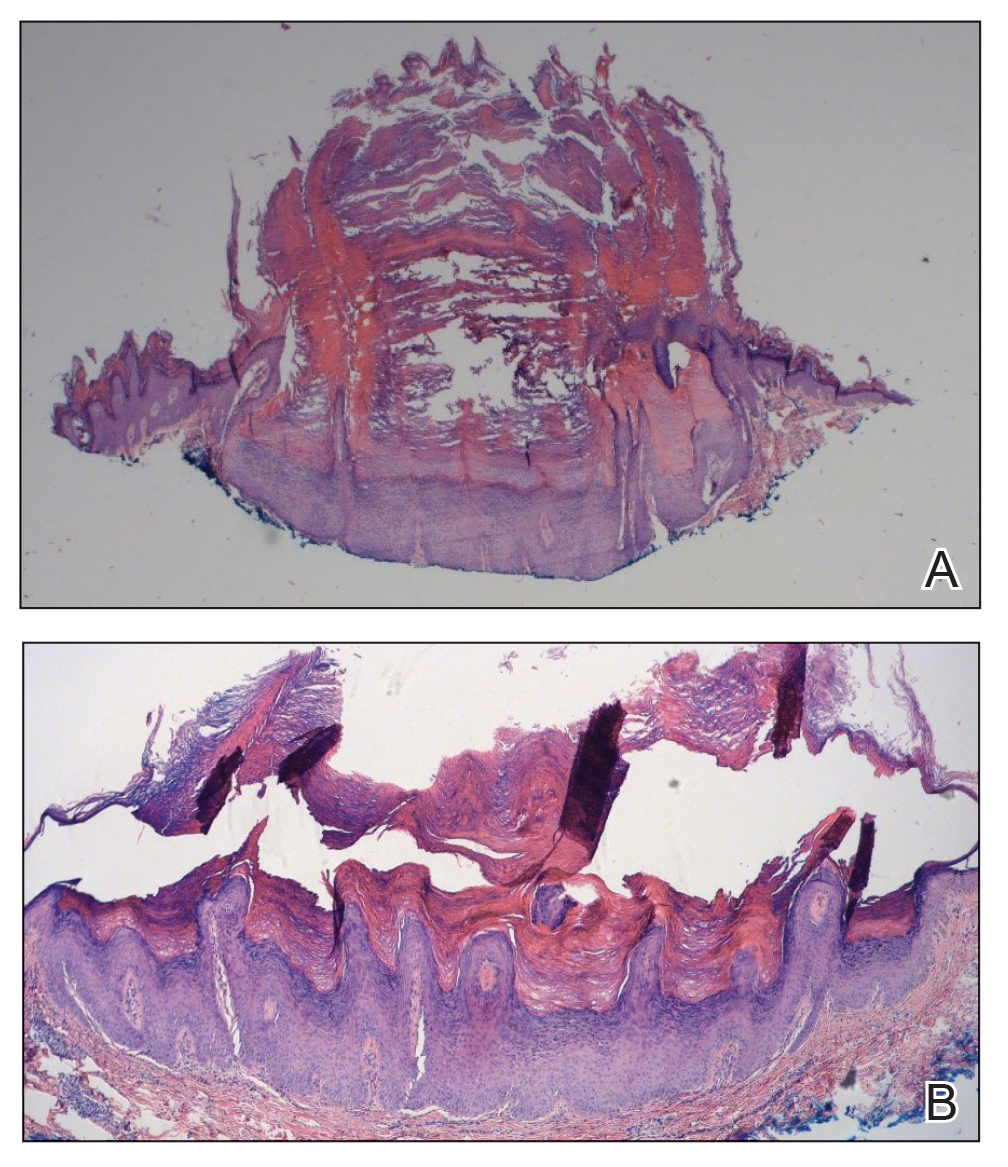

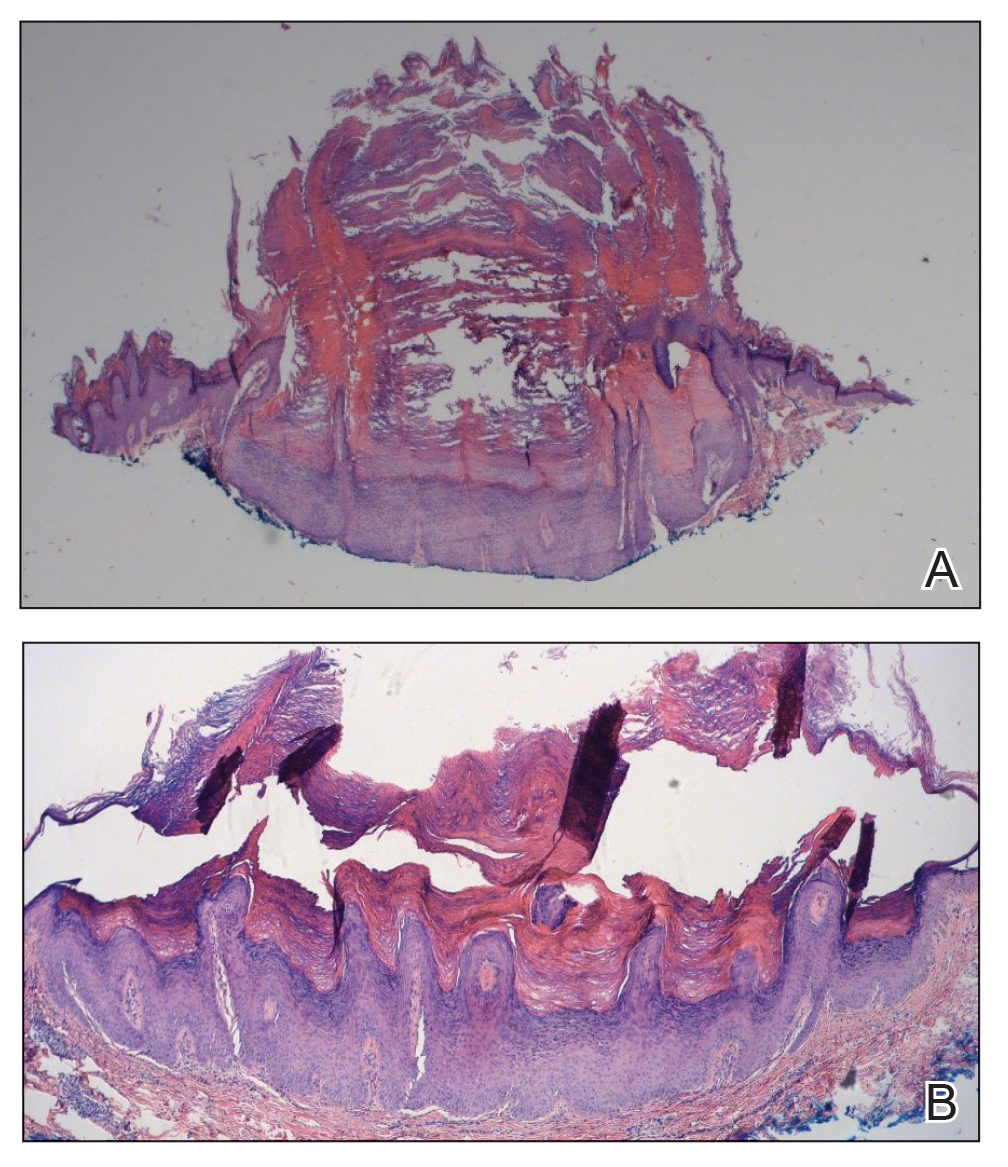

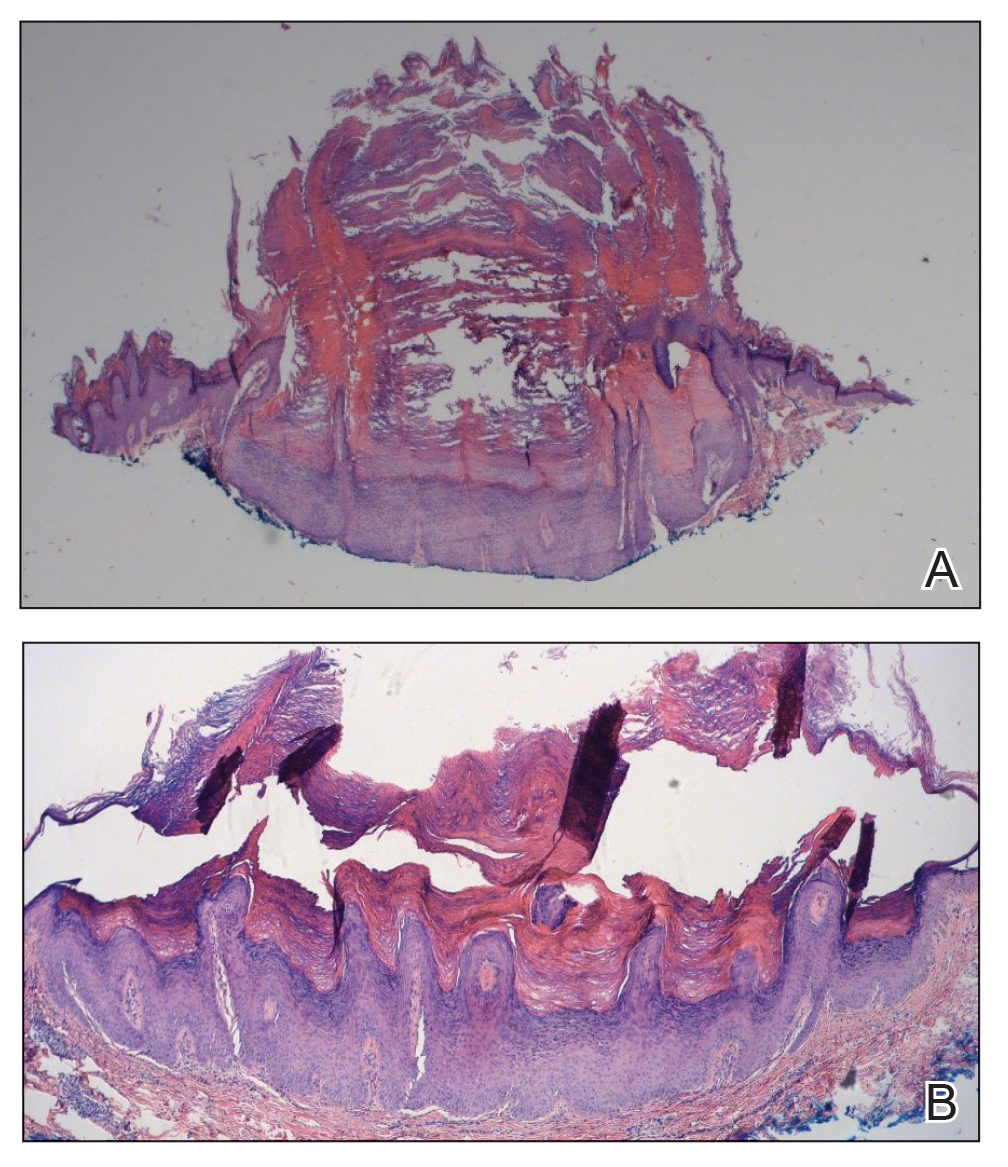

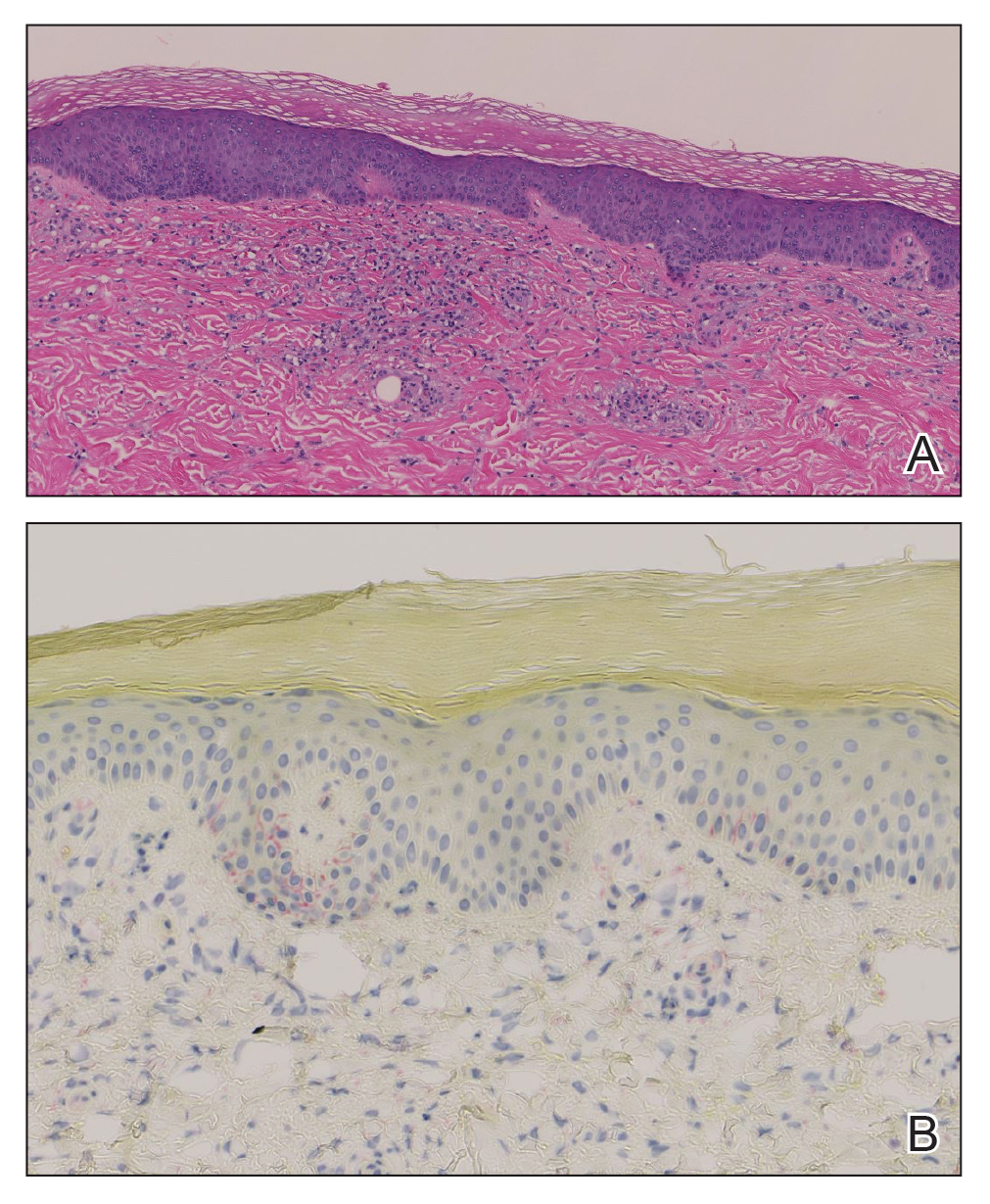

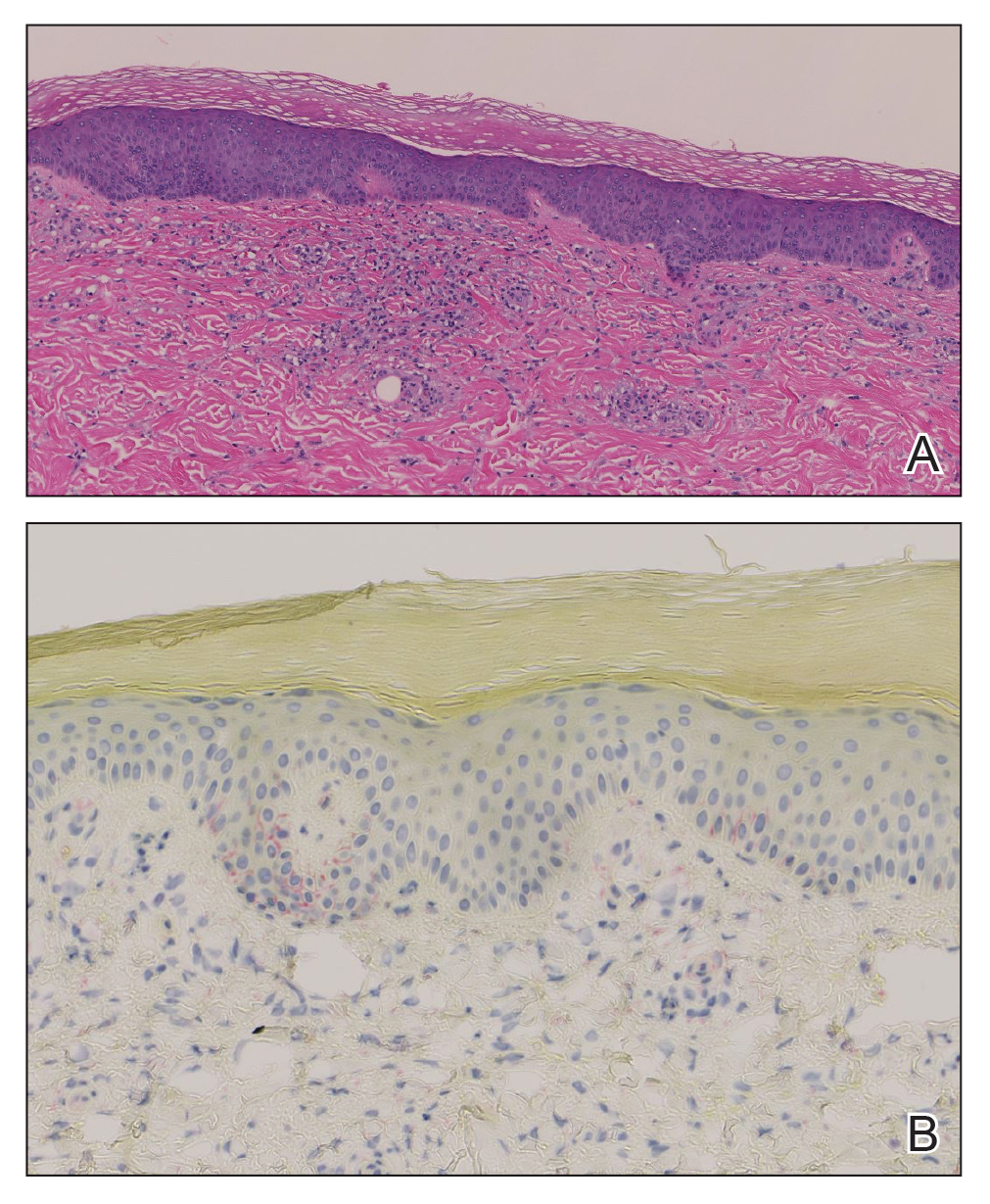

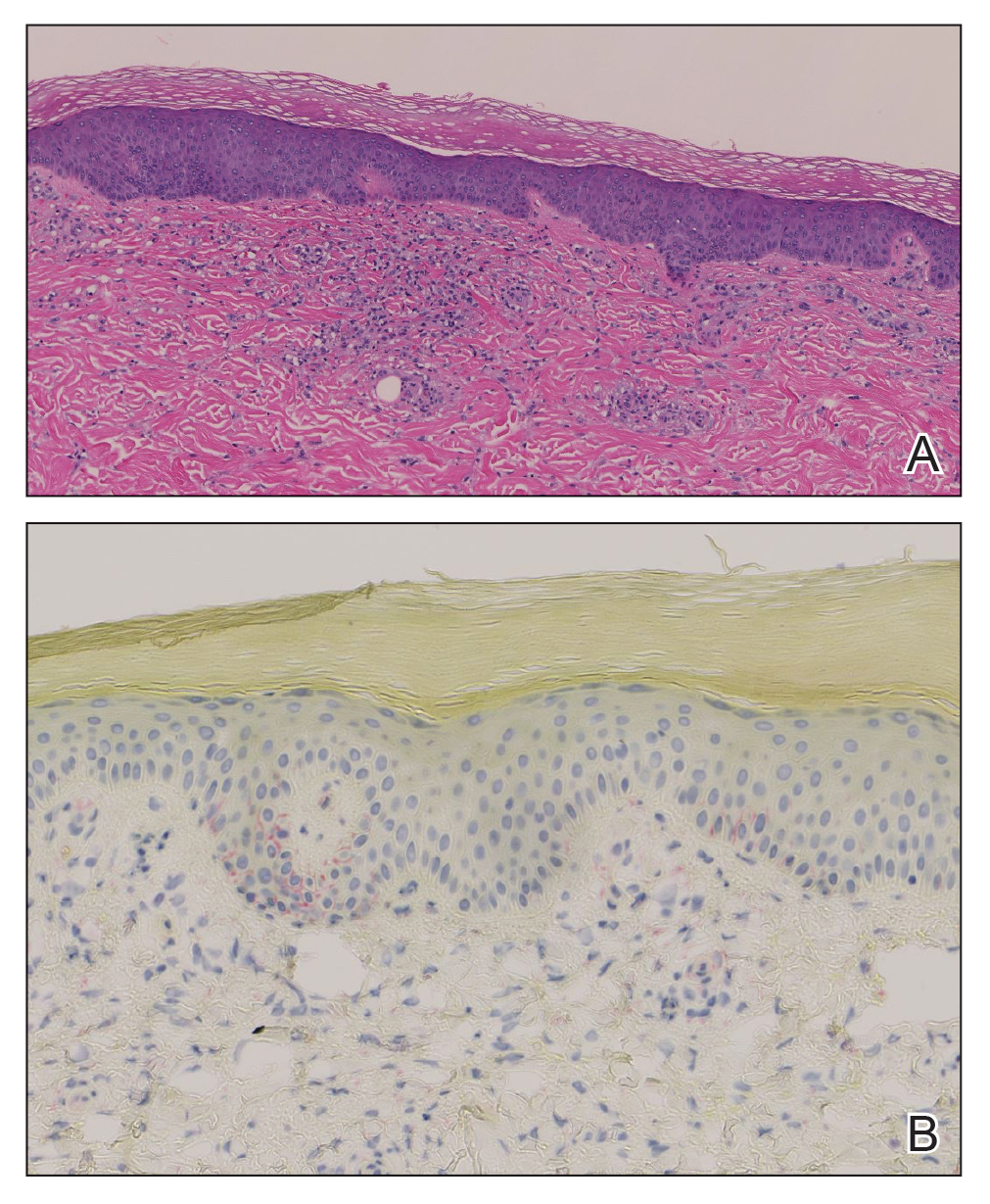

The retiform purpura observed in our patient was suggestive of a vasculitic, thrombotic, or embolic etiology. Dengue IgM serologic testing performed based on her extensive travel history and recent return from a dengue-endemic area was positive, indicating acute infection. A clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) was made based on the hemorrhagic appearance of the lesion. Histopathology revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure). Anti–double-stranded DNA, antideoxyribonuclease, C3 and C4, CH50 (total hemolytic complement), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis B virus tests were normal. Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

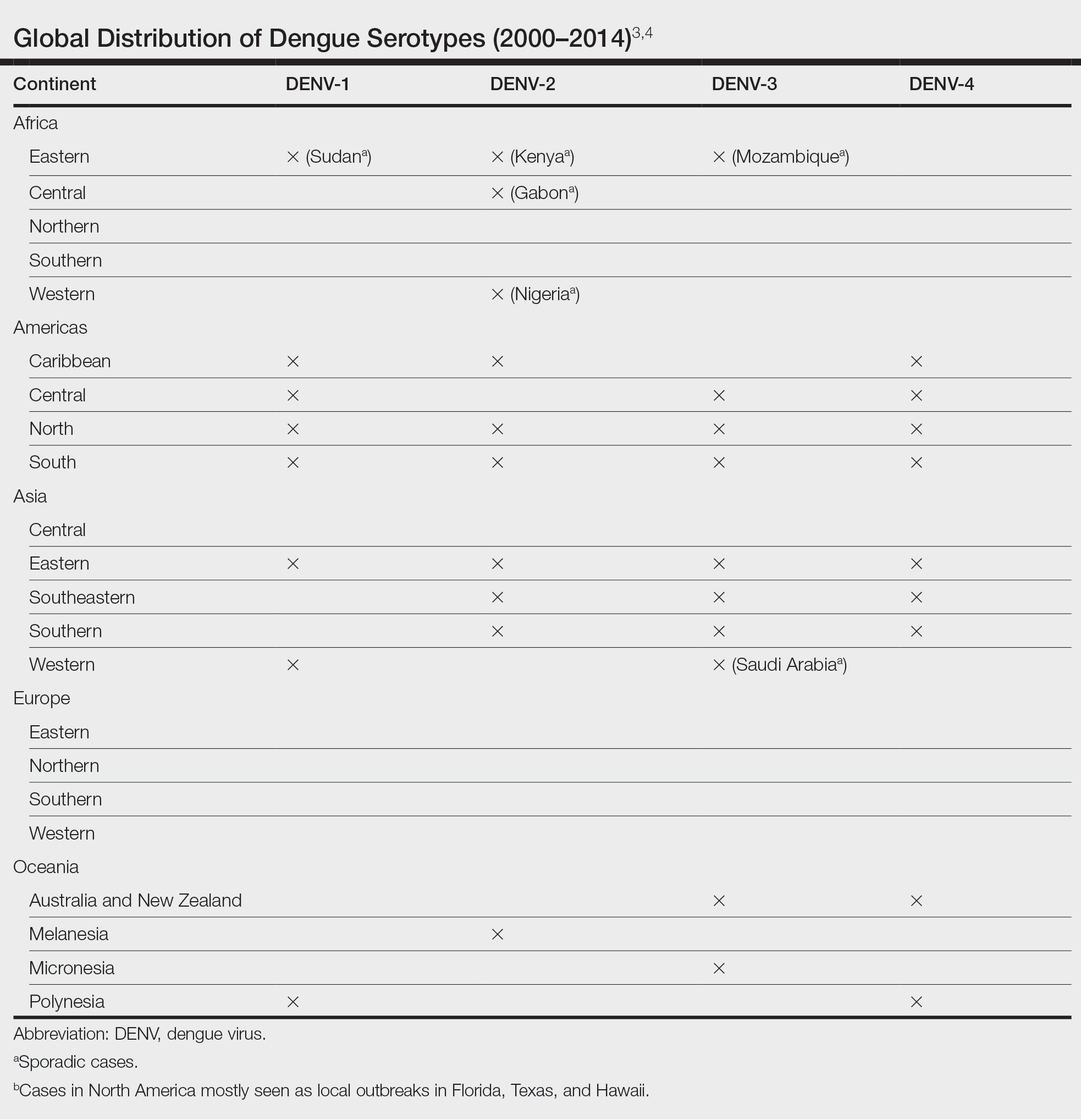

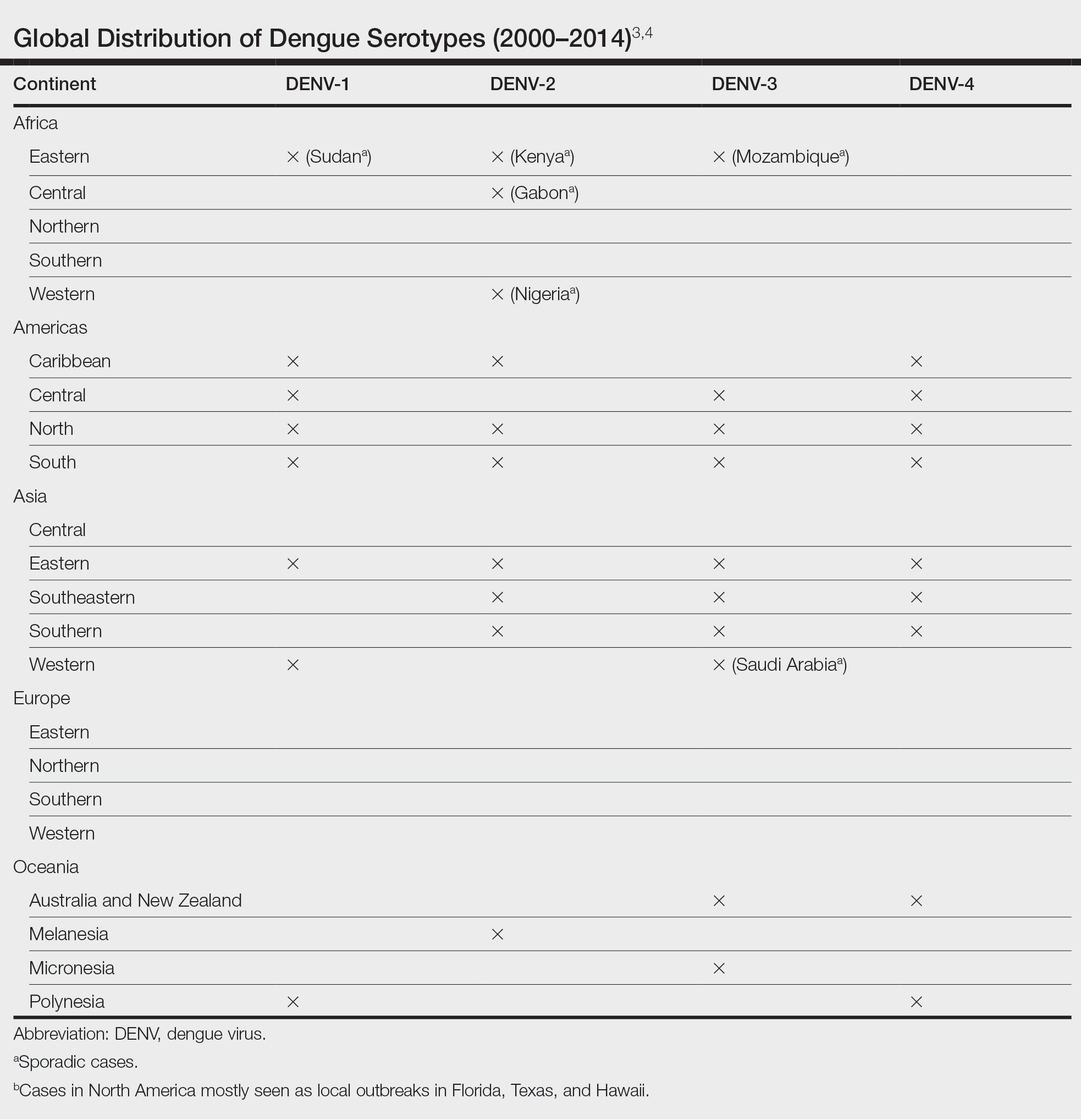

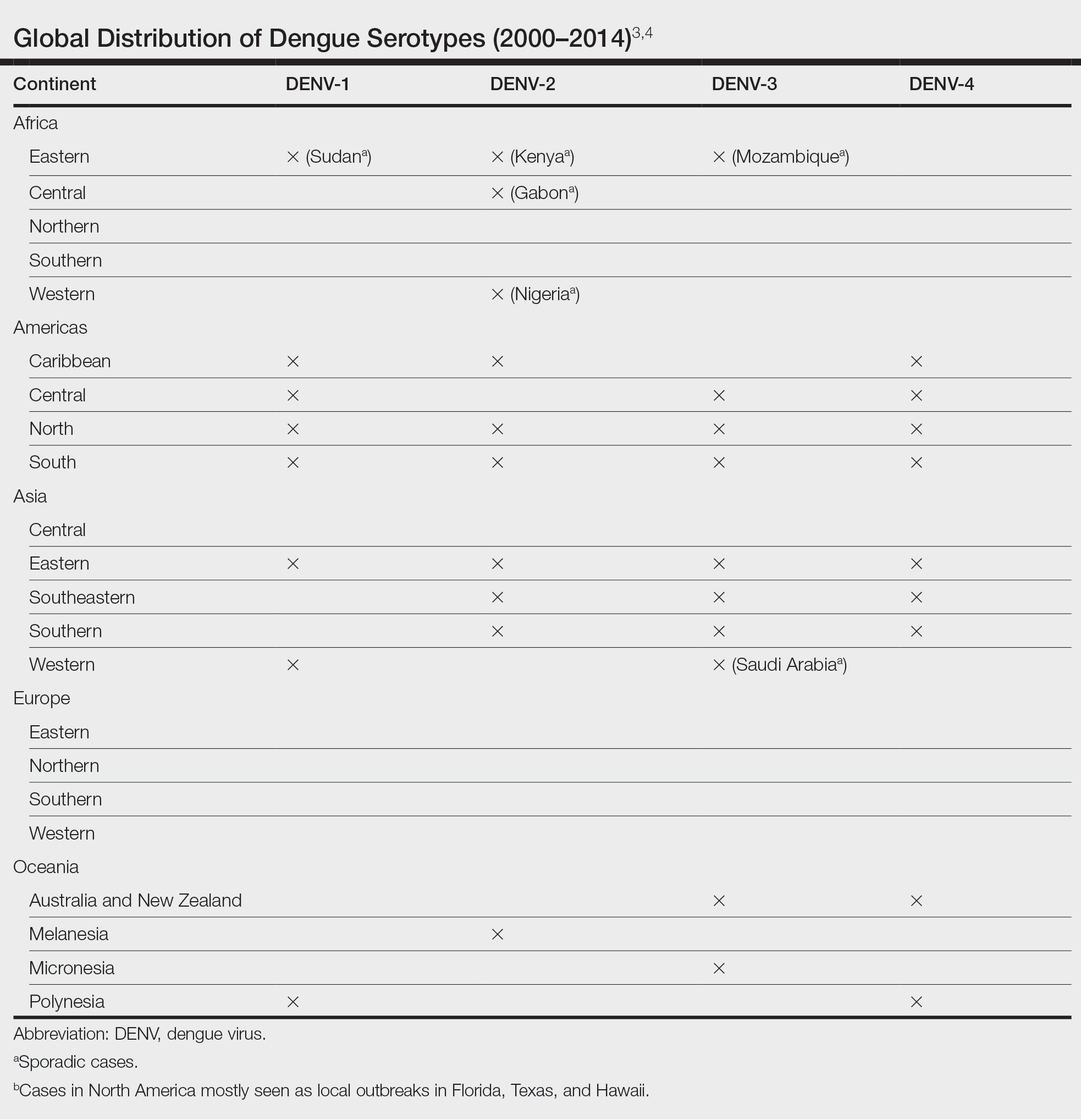

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and is one of the most prevalent arthropod-borne viruses affecting humans today.1,2 Infection with the dengue virus generally is seen in travelers visiting tropical regions of Africa, Mexico, South America, South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean.1 The Table shows the global distribution of dengue serotypes from 2000 to 2014.3,4 There are 4 serotypes of the dengue virus: DENV-1 to DENV-4. Infection with 1 strain elicits longlasting immunity to that strain, but subsequent infection with another strain can result in severe DHF due to antibody cross-reaction.1

Dengue virus infection ranges from mildly symptomatic to a spectrum of increasingly severe conditions that comprise dengue fever (DF) and DHF, as well as dengue shock syndrome and brain stem hemorrhage, which may be fatal.2,5 Dengue fever manifests as severe myalgia, fever, headache (usually retro-orbital), arthralgia, erythema, and rubelliform exanthema.6 The frequency of skin eruptions in patients with DF varies with the virus strain and outbreaks.7 The lesions initially develop with the onset of fever and manifest as flushing or erythematous mottling of the face, neck, and chest areas.1,7 The morbilliform eruption develops 2 to 6 days after the onset of the fever, beginning on the trunk and spreading to the face and extremities.1,7 The rash may become confluent with characteristic sparing of small round areas of normal skin described as white islands in a sea of red.2 Verrucous papules on the ears also have been described and may resemble those seen in Cowden syndrome. In patients with prior infection with a different strain of the virus, hemorrhagic lesions may develop, including characteristic retiform purpura, a positive tourniquet test, and the appearance of petechiae on the lower legs. Pruritus and desquamation, especially on the palms and soles, may follow the termination of the eruption.7

The differential diagnosis of DF includes measles, rubella, enteroviruses, and influenza. Chikungunya and West Nile viruses in Asia and Africa and the O’nyong-nyong virus in Africa are also arboviruses that cause a clinical picture similar to DF but not DHF. Other diagnostic considerations include phases of scarlet fever, typhoid, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, and trypanosomal and rickettsial diseases.7 The differential diagnosis of DHF includes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterial septic vasculitis.

Acute clinical diagnosis of DF can be challenging because of the nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in almost every infectious disease. Clinical presentation assessment should be confirmed with laboratory testing.6 Dengue virus infection usually is confirmed by the identification of viral genomic RNA, antigens, or the antibodies it elicits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based serologic tests are cost-effective and easy to perform.5 IgM antibodies usually show cross-reactivity with platelets, but the antibody levels are not positively correlated with the severity of DF.8 Primary infection with the dengue virus is characterized by the elevation of specific IgM levels that usually occurs 3 to 5 days after symptom onset and persists during the postfebrile stage (up to 30 to 60 days). In secondary infections, the IgM levels usually rise more slowly and reach a lower level than in primary infections.9 For both primary and secondary infections, testing IgM levels after the febrile stage may be helpful with the laboratory diagnosis.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug available for dengue. Treatment of dengue infection is symptomatic and supportive.2

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is indicated by a rising hematocrit (≥20%) and a falling platelet count (>100,000/mm3) accompanying clinical signs of hemorrhage. Treatment includes intravenous fluid replacement and careful clinical monitoring of hematocrit levels, platelet count, vitals, urine output, and other signs of shock.5 For patients with a history of dengue infection, travel to areas with other serotypes is not recommended.

If any travel to a high-risk area is planned, countryspecific travel recommendations and warnings should be reviewed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/dengue-global). Use of an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent to avoid mosquito bites and acetaminophen for managing symptoms is advised. During travel, staying in places with window and door screens and using a bed net during sleep are suggested. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants also are preferred. Travelers should see a health care provider if they have symptoms of dengue.10

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is caused by Rickettsia africae transmitted by Amblyomma ticks. Skin findings in ATBF include erythematous, firm, tender papules with central eschars consistent with the feeding patterns of ticks.11 Histopathology of ATBF usually includes fibrinoid necrosis of vessels in the dermis with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and coagulation necrosis of the surrounding dermis consistent with eschar formation.12 The lack of an eschar weighs against this diagnosis.

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is caused by protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly. A chancrelike, circumscribed, rubbery, indurated red or violaceous nodule measuring 2 to 5 cm in diameter often develops as the earliest cutaneous sign of the disease.13 Nonspecific histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts, may be observed.14 Extravascular parasites have been noted in skin biopsies.15 In later stages, skin lesions called trypanids may be observed as macular, papular, annular, targetoid, purpuric, and erythematous lesions, and histopathologic findings consistent with vasculitis also may be seen.13

Chikungunya virus infection is an acute-onset, mosquito-borne viral disease. Skin manifestations may start with nonspecific, generalized, morbilliform, maculopapular rashes coinciding with fever, which also may be seen initially with DHF. Skin hyperpigmentation, mostly centrofacial and involving the nose (chik sign); purpuric and ecchymotic lesions over the trunk and flexors of limbs in adults, often surmounted by subepidermal bullae and lesions resembling toxic epidermal necrolysis; and nonhealing ulcers in the genital and groin areas are common skin manifestations of chikungunya infection.16 Intraepithelial splitting with acantholysis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration may be observed in the histopathology of blistering lesions, which are not consistent with DHF.17

Zika virus infection is caused by an arbovirus within the Flaviviridae family, which also includes the dengue virus. Initial mucocutaneous findings of the Zika virus include nonspecific diffuse maculopapular eruptions. The eruption generally spares the palms and soles; however, various manifestations including involvement of the palms and soles have been reported.18 The morbilliform eruption begins on the face and extends to the trunk and extremities. Mild hemorrhagic manifestations, including petechiae and bleeding gums, may be observed. Distinguishing between dengue and Zika virus infection relies on the severity of symptoms and laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction or IgM antibody testing.19 The other conditions listed do not produce hemorrhagic fever.

- Pincus LB, Grossman ME, Fox LP. The exanthem of dengue fever: clinical features of two US tourists traveling abroad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:308-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.042

- Radakovic-Fijan S, Graninger W, Müller C, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in a British travel guide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:430-433. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.111904

- Yamashita A, Sakamoto T, Sekizuka T, et al. DGV: dengue genographic viewer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:875. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00875

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dengue in the US states and territories. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/in-the-us.html

- Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6803098. doi:10.1155/2016/6803098

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl 2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Waterman SH, Gubler DJ. Dengue fever. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:117-122. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(89)90034-5

- Lin CF, Lei HY, Liu CC, et al. Generation of IgM anti-platelet autoantibody in dengue patients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:143-149. doi:10.1002/1096- 9071(20000201)63:2<143::AID-JMV1009>3.0.CO;2-L

- Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A, Dash PK, et al. Detection of dengue virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:51-64. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan for travel. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel

- Mack I, Ritz N. African tick-bite fever. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:960. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1810093

- Lepidi H, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Histologic features and immunodetection of African tick-bite fever eschar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1332- 1337. doi:10.3201/eid1209.051540

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1178-1182.

- Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Pathology of African trypanosomiasis. In: Dumas M, Bouteille B, Buguet A, eds. Progress in Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. Springer; 1999:157-181.

- Capewell P, Cren-Travaillé C, Marchesi F, et al. The skin is a significant but overlooked anatomical reservoir for vector-borne African trypanosomes. Elife. 2016;5:e17716. doi:10.7554/eLife.17716

- Singal A. Chikungunya and skin: current perspective. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:307-309. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_93_17

- Robin S, Ramful D, Zettor J, et al. Severe bullous skin lesions associated with chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;169:67-72. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-0986-0

- Hussain A, Ali F, Latiwesh OB, et al. A comprehensive review of the manifestations and pathogenesis of Zika virus in neonates and adults. Cureus. 2018;10:E3290. doi:10.7759/cureus.3290

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim K, Blattner CM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Zika virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1286-1287. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1232

THE DIAGNOSIS: Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

The retiform purpura observed in our patient was suggestive of a vasculitic, thrombotic, or embolic etiology. Dengue IgM serologic testing performed based on her extensive travel history and recent return from a dengue-endemic area was positive, indicating acute infection. A clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) was made based on the hemorrhagic appearance of the lesion. Histopathology revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure). Anti–double-stranded DNA, antideoxyribonuclease, C3 and C4, CH50 (total hemolytic complement), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis B virus tests were normal. Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and is one of the most prevalent arthropod-borne viruses affecting humans today.1,2 Infection with the dengue virus generally is seen in travelers visiting tropical regions of Africa, Mexico, South America, South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean.1 The Table shows the global distribution of dengue serotypes from 2000 to 2014.3,4 There are 4 serotypes of the dengue virus: DENV-1 to DENV-4. Infection with 1 strain elicits longlasting immunity to that strain, but subsequent infection with another strain can result in severe DHF due to antibody cross-reaction.1

Dengue virus infection ranges from mildly symptomatic to a spectrum of increasingly severe conditions that comprise dengue fever (DF) and DHF, as well as dengue shock syndrome and brain stem hemorrhage, which may be fatal.2,5 Dengue fever manifests as severe myalgia, fever, headache (usually retro-orbital), arthralgia, erythema, and rubelliform exanthema.6 The frequency of skin eruptions in patients with DF varies with the virus strain and outbreaks.7 The lesions initially develop with the onset of fever and manifest as flushing or erythematous mottling of the face, neck, and chest areas.1,7 The morbilliform eruption develops 2 to 6 days after the onset of the fever, beginning on the trunk and spreading to the face and extremities.1,7 The rash may become confluent with characteristic sparing of small round areas of normal skin described as white islands in a sea of red.2 Verrucous papules on the ears also have been described and may resemble those seen in Cowden syndrome. In patients with prior infection with a different strain of the virus, hemorrhagic lesions may develop, including characteristic retiform purpura, a positive tourniquet test, and the appearance of petechiae on the lower legs. Pruritus and desquamation, especially on the palms and soles, may follow the termination of the eruption.7

The differential diagnosis of DF includes measles, rubella, enteroviruses, and influenza. Chikungunya and West Nile viruses in Asia and Africa and the O’nyong-nyong virus in Africa are also arboviruses that cause a clinical picture similar to DF but not DHF. Other diagnostic considerations include phases of scarlet fever, typhoid, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, and trypanosomal and rickettsial diseases.7 The differential diagnosis of DHF includes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterial septic vasculitis.

Acute clinical diagnosis of DF can be challenging because of the nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in almost every infectious disease. Clinical presentation assessment should be confirmed with laboratory testing.6 Dengue virus infection usually is confirmed by the identification of viral genomic RNA, antigens, or the antibodies it elicits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based serologic tests are cost-effective and easy to perform.5 IgM antibodies usually show cross-reactivity with platelets, but the antibody levels are not positively correlated with the severity of DF.8 Primary infection with the dengue virus is characterized by the elevation of specific IgM levels that usually occurs 3 to 5 days after symptom onset and persists during the postfebrile stage (up to 30 to 60 days). In secondary infections, the IgM levels usually rise more slowly and reach a lower level than in primary infections.9 For both primary and secondary infections, testing IgM levels after the febrile stage may be helpful with the laboratory diagnosis.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug available for dengue. Treatment of dengue infection is symptomatic and supportive.2

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is indicated by a rising hematocrit (≥20%) and a falling platelet count (>100,000/mm3) accompanying clinical signs of hemorrhage. Treatment includes intravenous fluid replacement and careful clinical monitoring of hematocrit levels, platelet count, vitals, urine output, and other signs of shock.5 For patients with a history of dengue infection, travel to areas with other serotypes is not recommended.

If any travel to a high-risk area is planned, countryspecific travel recommendations and warnings should be reviewed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/dengue-global). Use of an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent to avoid mosquito bites and acetaminophen for managing symptoms is advised. During travel, staying in places with window and door screens and using a bed net during sleep are suggested. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants also are preferred. Travelers should see a health care provider if they have symptoms of dengue.10

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is caused by Rickettsia africae transmitted by Amblyomma ticks. Skin findings in ATBF include erythematous, firm, tender papules with central eschars consistent with the feeding patterns of ticks.11 Histopathology of ATBF usually includes fibrinoid necrosis of vessels in the dermis with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and coagulation necrosis of the surrounding dermis consistent with eschar formation.12 The lack of an eschar weighs against this diagnosis.

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is caused by protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly. A chancrelike, circumscribed, rubbery, indurated red or violaceous nodule measuring 2 to 5 cm in diameter often develops as the earliest cutaneous sign of the disease.13 Nonspecific histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts, may be observed.14 Extravascular parasites have been noted in skin biopsies.15 In later stages, skin lesions called trypanids may be observed as macular, papular, annular, targetoid, purpuric, and erythematous lesions, and histopathologic findings consistent with vasculitis also may be seen.13

Chikungunya virus infection is an acute-onset, mosquito-borne viral disease. Skin manifestations may start with nonspecific, generalized, morbilliform, maculopapular rashes coinciding with fever, which also may be seen initially with DHF. Skin hyperpigmentation, mostly centrofacial and involving the nose (chik sign); purpuric and ecchymotic lesions over the trunk and flexors of limbs in adults, often surmounted by subepidermal bullae and lesions resembling toxic epidermal necrolysis; and nonhealing ulcers in the genital and groin areas are common skin manifestations of chikungunya infection.16 Intraepithelial splitting with acantholysis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration may be observed in the histopathology of blistering lesions, which are not consistent with DHF.17

Zika virus infection is caused by an arbovirus within the Flaviviridae family, which also includes the dengue virus. Initial mucocutaneous findings of the Zika virus include nonspecific diffuse maculopapular eruptions. The eruption generally spares the palms and soles; however, various manifestations including involvement of the palms and soles have been reported.18 The morbilliform eruption begins on the face and extends to the trunk and extremities. Mild hemorrhagic manifestations, including petechiae and bleeding gums, may be observed. Distinguishing between dengue and Zika virus infection relies on the severity of symptoms and laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction or IgM antibody testing.19 The other conditions listed do not produce hemorrhagic fever.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever

The retiform purpura observed in our patient was suggestive of a vasculitic, thrombotic, or embolic etiology. Dengue IgM serologic testing performed based on her extensive travel history and recent return from a dengue-endemic area was positive, indicating acute infection. A clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) was made based on the hemorrhagic appearance of the lesion. Histopathology revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figure). Anti–double-stranded DNA, antideoxyribonuclease, C3 and C4, CH50 (total hemolytic complement), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, HIV, and hepatitis B virus tests were normal. Direct immunofluorescence was negative.

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes and is one of the most prevalent arthropod-borne viruses affecting humans today.1,2 Infection with the dengue virus generally is seen in travelers visiting tropical regions of Africa, Mexico, South America, South and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean.1 The Table shows the global distribution of dengue serotypes from 2000 to 2014.3,4 There are 4 serotypes of the dengue virus: DENV-1 to DENV-4. Infection with 1 strain elicits longlasting immunity to that strain, but subsequent infection with another strain can result in severe DHF due to antibody cross-reaction.1

Dengue virus infection ranges from mildly symptomatic to a spectrum of increasingly severe conditions that comprise dengue fever (DF) and DHF, as well as dengue shock syndrome and brain stem hemorrhage, which may be fatal.2,5 Dengue fever manifests as severe myalgia, fever, headache (usually retro-orbital), arthralgia, erythema, and rubelliform exanthema.6 The frequency of skin eruptions in patients with DF varies with the virus strain and outbreaks.7 The lesions initially develop with the onset of fever and manifest as flushing or erythematous mottling of the face, neck, and chest areas.1,7 The morbilliform eruption develops 2 to 6 days after the onset of the fever, beginning on the trunk and spreading to the face and extremities.1,7 The rash may become confluent with characteristic sparing of small round areas of normal skin described as white islands in a sea of red.2 Verrucous papules on the ears also have been described and may resemble those seen in Cowden syndrome. In patients with prior infection with a different strain of the virus, hemorrhagic lesions may develop, including characteristic retiform purpura, a positive tourniquet test, and the appearance of petechiae on the lower legs. Pruritus and desquamation, especially on the palms and soles, may follow the termination of the eruption.7

The differential diagnosis of DF includes measles, rubella, enteroviruses, and influenza. Chikungunya and West Nile viruses in Asia and Africa and the O’nyong-nyong virus in Africa are also arboviruses that cause a clinical picture similar to DF but not DHF. Other diagnostic considerations include phases of scarlet fever, typhoid, malaria, leptospirosis, hepatitis A, and trypanosomal and rickettsial diseases.7 The differential diagnosis of DHF includes antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody–associated vasculitis, rheumatoid vasculitis, and bacterial septic vasculitis.

Acute clinical diagnosis of DF can be challenging because of the nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in almost every infectious disease. Clinical presentation assessment should be confirmed with laboratory testing.6 Dengue virus infection usually is confirmed by the identification of viral genomic RNA, antigens, or the antibodies it elicits. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay–based serologic tests are cost-effective and easy to perform.5 IgM antibodies usually show cross-reactivity with platelets, but the antibody levels are not positively correlated with the severity of DF.8 Primary infection with the dengue virus is characterized by the elevation of specific IgM levels that usually occurs 3 to 5 days after symptom onset and persists during the postfebrile stage (up to 30 to 60 days). In secondary infections, the IgM levels usually rise more slowly and reach a lower level than in primary infections.9 For both primary and secondary infections, testing IgM levels after the febrile stage may be helpful with the laboratory diagnosis.

Currently, there is no antiviral drug available for dengue. Treatment of dengue infection is symptomatic and supportive.2

Dengue hemorrhagic fever is indicated by a rising hematocrit (≥20%) and a falling platelet count (>100,000/mm3) accompanying clinical signs of hemorrhage. Treatment includes intravenous fluid replacement and careful clinical monitoring of hematocrit levels, platelet count, vitals, urine output, and other signs of shock.5 For patients with a history of dengue infection, travel to areas with other serotypes is not recommended.

If any travel to a high-risk area is planned, countryspecific travel recommendations and warnings should be reviewed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level1/dengue-global). Use of an Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellent to avoid mosquito bites and acetaminophen for managing symptoms is advised. During travel, staying in places with window and door screens and using a bed net during sleep are suggested. Long-sleeved shirts and long pants also are preferred. Travelers should see a health care provider if they have symptoms of dengue.10

African tick bite fever (ATBF) is caused by Rickettsia africae transmitted by Amblyomma ticks. Skin findings in ATBF include erythematous, firm, tender papules with central eschars consistent with the feeding patterns of ticks.11 Histopathology of ATBF usually includes fibrinoid necrosis of vessels in the dermis with a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate and coagulation necrosis of the surrounding dermis consistent with eschar formation.12 The lack of an eschar weighs against this diagnosis.

African trypanosomiasis (also known as sleeping sickness) is caused by protozoa transmitted by the tsetse fly. A chancrelike, circumscribed, rubbery, indurated red or violaceous nodule measuring 2 to 5 cm in diameter often develops as the earliest cutaneous sign of the disease.13 Nonspecific histopathologic findings, such as infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages and proliferation of endothelial cells and fibroblasts, may be observed.14 Extravascular parasites have been noted in skin biopsies.15 In later stages, skin lesions called trypanids may be observed as macular, papular, annular, targetoid, purpuric, and erythematous lesions, and histopathologic findings consistent with vasculitis also may be seen.13

Chikungunya virus infection is an acute-onset, mosquito-borne viral disease. Skin manifestations may start with nonspecific, generalized, morbilliform, maculopapular rashes coinciding with fever, which also may be seen initially with DHF. Skin hyperpigmentation, mostly centrofacial and involving the nose (chik sign); purpuric and ecchymotic lesions over the trunk and flexors of limbs in adults, often surmounted by subepidermal bullae and lesions resembling toxic epidermal necrolysis; and nonhealing ulcers in the genital and groin areas are common skin manifestations of chikungunya infection.16 Intraepithelial splitting with acantholysis and perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltration may be observed in the histopathology of blistering lesions, which are not consistent with DHF.17

Zika virus infection is caused by an arbovirus within the Flaviviridae family, which also includes the dengue virus. Initial mucocutaneous findings of the Zika virus include nonspecific diffuse maculopapular eruptions. The eruption generally spares the palms and soles; however, various manifestations including involvement of the palms and soles have been reported.18 The morbilliform eruption begins on the face and extends to the trunk and extremities. Mild hemorrhagic manifestations, including petechiae and bleeding gums, may be observed. Distinguishing between dengue and Zika virus infection relies on the severity of symptoms and laboratory tests, including polymerase chain reaction or IgM antibody testing.19 The other conditions listed do not produce hemorrhagic fever.

- Pincus LB, Grossman ME, Fox LP. The exanthem of dengue fever: clinical features of two US tourists traveling abroad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:308-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.042

- Radakovic-Fijan S, Graninger W, Müller C, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in a British travel guide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:430-433. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.111904

- Yamashita A, Sakamoto T, Sekizuka T, et al. DGV: dengue genographic viewer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:875. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00875

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dengue in the US states and territories. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/in-the-us.html

- Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6803098. doi:10.1155/2016/6803098

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl 2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Waterman SH, Gubler DJ. Dengue fever. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:117-122. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(89)90034-5

- Lin CF, Lei HY, Liu CC, et al. Generation of IgM anti-platelet autoantibody in dengue patients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:143-149. doi:10.1002/1096- 9071(20000201)63:2<143::AID-JMV1009>3.0.CO;2-L

- Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A, Dash PK, et al. Detection of dengue virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:51-64. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan for travel. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel

- Mack I, Ritz N. African tick-bite fever. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:960. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1810093

- Lepidi H, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Histologic features and immunodetection of African tick-bite fever eschar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1332- 1337. doi:10.3201/eid1209.051540

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1178-1182.

- Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Pathology of African trypanosomiasis. In: Dumas M, Bouteille B, Buguet A, eds. Progress in Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. Springer; 1999:157-181.

- Capewell P, Cren-Travaillé C, Marchesi F, et al. The skin is a significant but overlooked anatomical reservoir for vector-borne African trypanosomes. Elife. 2016;5:e17716. doi:10.7554/eLife.17716

- Singal A. Chikungunya and skin: current perspective. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:307-309. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_93_17

- Robin S, Ramful D, Zettor J, et al. Severe bullous skin lesions associated with chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;169:67-72. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-0986-0

- Hussain A, Ali F, Latiwesh OB, et al. A comprehensive review of the manifestations and pathogenesis of Zika virus in neonates and adults. Cureus. 2018;10:E3290. doi:10.7759/cureus.3290

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim K, Blattner CM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Zika virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1286-1287. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1232

- Pincus LB, Grossman ME, Fox LP. The exanthem of dengue fever: clinical features of two US tourists traveling abroad. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:308-316. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.042

- Radakovic-Fijan S, Graninger W, Müller C, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever in a British travel guide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:430-433. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.111904

- Yamashita A, Sakamoto T, Sekizuka T, et al. DGV: dengue genographic viewer. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:875. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00875

- Centers for Disease and Prevention. Dengue in the US states and territories. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/areaswithrisk/in-the-us.html

- Khetarpal N, Khanna I. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:6803098. doi:10.1155/2016/6803098

- Muller DA, Depelsenaire AC, Young PR. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(suppl 2):S89-S95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw649

- Waterman SH, Gubler DJ. Dengue fever. Clin Dermatol. 1989;7:117-122. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(89)90034-5

- Lin CF, Lei HY, Liu CC, et al. Generation of IgM anti-platelet autoantibody in dengue patients. J Med Virol. 2001;63:143-149. doi:10.1002/1096- 9071(20000201)63:2<143::AID-JMV1009>3.0.CO;2-L

- Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A, Dash PK, et al. Detection of dengue virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;665:51-64. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-817-1_4

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan for travel. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel

- Mack I, Ritz N. African tick-bite fever. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:960. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1810093

- Lepidi H, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Histologic features and immunodetection of African tick-bite fever eschar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1332- 1337. doi:10.3201/eid1209.051540

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1178-1182.

- Kristensson K, Bentivoglio M. Pathology of African trypanosomiasis. In: Dumas M, Bouteille B, Buguet A, eds. Progress in Human African Trypanosomiasis, Sleeping Sickness. Springer; 1999:157-181.

- Capewell P, Cren-Travaillé C, Marchesi F, et al. The skin is a significant but overlooked anatomical reservoir for vector-borne African trypanosomes. Elife. 2016;5:e17716. doi:10.7554/eLife.17716

- Singal A. Chikungunya and skin: current perspective. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:307-309. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_93_17

- Robin S, Ramful D, Zettor J, et al. Severe bullous skin lesions associated with chikungunya virus infection in small infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;169:67-72. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-0986-0

- Hussain A, Ali F, Latiwesh OB, et al. A comprehensive review of the manifestations and pathogenesis of Zika virus in neonates and adults. Cureus. 2018;10:E3290. doi:10.7759/cureus.3290

- Farahnik B, Beroukhim K, Blattner CM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the Zika virus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1286-1287. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1232

A 74-year-old woman who frequently traveled abroad presented to the dermatology department with retiform purpura of the lower leg along with gastrointestinal cramps, fatigue, and myalgia. The patient reported that the symptoms had started 10 days after returning from a recent trip to Africa.

Commentary: Migraine and Comorbidities, October 2024

Neck pain is commonly associated with headaches, especially with migraine headaches. This is well recognized, and the symptom of neck pain occurring during headache episodes or even independently of headache episodes is at least partially related to pain sensitivity.1 While neck pain is often considered a part of the migraine experience, it's not commonly thought of as a disabling symptom. However, neck pain can be a major aspect of migraine disability.

A systematic review published in August 2024 in the journal Cephalalgia described neck pain disability as a part of migraine. The authors used 33 clinic-based studies that utilized either the Neck Disability Index (NDI) or the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) to define the severity of neck pain disability. They concluded that individuals with migraine had higher NDI and NPRS scores than patients with tension-type headaches and patients without headaches. According to the NDI scoring system, 0–4 points indicate no disability, 5–14 points indicate mild disability, 15–24 points indicate moderate disability, 25–34 points indicate severe disability, and ≥ 35 points indicate complete disability. The authors reported that the mean NDI score for patients with migraine was 16.2, which was approximately 12 points higher than for healthy headache-free control participants.2 This brings to light an issue that can substantially affect patients' quality of life. Patients who have neck pain with migraine may need focused attention to that symptom, in addition to overall migraine therapy, and it is important to ask migraine patients about the degree to which neck pain affects their life. In fact, many patients might not even realize that their neck pain is associated with their migraines.

Cardiovascular disease is another comorbidity that has been inconsistently associated with migraine. A study published in Headache: The Journal of Headache and Face Pain in August 2024 used data from a Danish population-based cohort longitudinal study that included over 140,000 women. The authors reported that migraine was associated with a risk for major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in women aged ≤ 60 years.3

This link has been noted previously, although the studies have been inconsistent regarding how strong the link is, any specific causality, and whether there is a link at all. Potential causes for the possible associations have been attributed to "endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulability, platelet aggregation, vasospasm, cardiovascular risk factors, paradoxical embolism, spreading depolarization, shared genetic risk, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and immobilization."4

Of note, there has also been documentation of a possible negative correlation between migraine and cardiovascular disease. Another article, from The Journal of Headache and Pain, published in August 2024, used data from 873,341 and 554,569 individuals, respectively, in two meta-analyses. The authors reported a potential protective effect of migraine on coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke, and a potential protective effect of coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction on migraine.5

A possible explanation for the conflicting results could lie in heterogeneity of migraine. For example, vestibular migraine is associated with many comorbidities, including anxiety disorders or depressive disorders, sleep disorders, persistent postural-perceptual dizziness, and Meniere disease.6 Given the serious consequences of cardiovascular disease, screening for risk factors could be beneficial for preventing adverse health outcomes for migraine patients. Eventually, further research may reveal more specific correlations between comorbidities and migraine subtypes, rather than generalizing comorbidities to all migraine types.

Sources

- Al-Khazali HM, Krøll LS, Ashina H, et al. Neck pain and headache: Pathophysiology, treatments and future directions. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2023;66:102804. Source

- Al-Khazali HM, Al-Sayegh Z, Younis S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2024;44:3331024241274266. Source

- Fuglsang CH, Pedersen L, Schmidt M, Vandenbroucke JP, Bøtker HE, Sørensen HT. The combined impact of migraine and gestational diabetes on long-term risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Headache. 2024 Aug 28. Source

- Agostoni EC, Longoni M. Migraine and cerebrovascular disease: still a dangerous connection? Neurol Sci. 2018;39(Suppl 1):33-37. Source

- Duan X, Du X, Zheng G, et al. Causality between migraine and cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:130. Source

- Ma YM, Zhang DP, Zhang HL, et al. Why is vestibular migraine associated with many comorbidities? J Neurol. 2024 Sept 20. Source

Neck pain is commonly associated with headaches, especially with migraine headaches. This is well recognized, and the symptom of neck pain occurring during headache episodes or even independently of headache episodes is at least partially related to pain sensitivity.1 While neck pain is often considered a part of the migraine experience, it's not commonly thought of as a disabling symptom. However, neck pain can be a major aspect of migraine disability.

A systematic review published in August 2024 in the journal Cephalalgia described neck pain disability as a part of migraine. The authors used 33 clinic-based studies that utilized either the Neck Disability Index (NDI) or the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) to define the severity of neck pain disability. They concluded that individuals with migraine had higher NDI and NPRS scores than patients with tension-type headaches and patients without headaches. According to the NDI scoring system, 0–4 points indicate no disability, 5–14 points indicate mild disability, 15–24 points indicate moderate disability, 25–34 points indicate severe disability, and ≥ 35 points indicate complete disability. The authors reported that the mean NDI score for patients with migraine was 16.2, which was approximately 12 points higher than for healthy headache-free control participants.2 This brings to light an issue that can substantially affect patients' quality of life. Patients who have neck pain with migraine may need focused attention to that symptom, in addition to overall migraine therapy, and it is important to ask migraine patients about the degree to which neck pain affects their life. In fact, many patients might not even realize that their neck pain is associated with their migraines.

Cardiovascular disease is another comorbidity that has been inconsistently associated with migraine. A study published in Headache: The Journal of Headache and Face Pain in August 2024 used data from a Danish population-based cohort longitudinal study that included over 140,000 women. The authors reported that migraine was associated with a risk for major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in women aged ≤ 60 years.3

This link has been noted previously, although the studies have been inconsistent regarding how strong the link is, any specific causality, and whether there is a link at all. Potential causes for the possible associations have been attributed to "endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulability, platelet aggregation, vasospasm, cardiovascular risk factors, paradoxical embolism, spreading depolarization, shared genetic risk, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and immobilization."4

Of note, there has also been documentation of a possible negative correlation between migraine and cardiovascular disease. Another article, from The Journal of Headache and Pain, published in August 2024, used data from 873,341 and 554,569 individuals, respectively, in two meta-analyses. The authors reported a potential protective effect of migraine on coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke, and a potential protective effect of coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction on migraine.5

A possible explanation for the conflicting results could lie in heterogeneity of migraine. For example, vestibular migraine is associated with many comorbidities, including anxiety disorders or depressive disorders, sleep disorders, persistent postural-perceptual dizziness, and Meniere disease.6 Given the serious consequences of cardiovascular disease, screening for risk factors could be beneficial for preventing adverse health outcomes for migraine patients. Eventually, further research may reveal more specific correlations between comorbidities and migraine subtypes, rather than generalizing comorbidities to all migraine types.

Sources

- Al-Khazali HM, Krøll LS, Ashina H, et al. Neck pain and headache: Pathophysiology, treatments and future directions. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2023;66:102804. Source

- Al-Khazali HM, Al-Sayegh Z, Younis S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2024;44:3331024241274266. Source

- Fuglsang CH, Pedersen L, Schmidt M, Vandenbroucke JP, Bøtker HE, Sørensen HT. The combined impact of migraine and gestational diabetes on long-term risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Headache. 2024 Aug 28. Source

- Agostoni EC, Longoni M. Migraine and cerebrovascular disease: still a dangerous connection? Neurol Sci. 2018;39(Suppl 1):33-37. Source

- Duan X, Du X, Zheng G, et al. Causality between migraine and cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:130. Source

- Ma YM, Zhang DP, Zhang HL, et al. Why is vestibular migraine associated with many comorbidities? J Neurol. 2024 Sept 20. Source

Neck pain is commonly associated with headaches, especially with migraine headaches. This is well recognized, and the symptom of neck pain occurring during headache episodes or even independently of headache episodes is at least partially related to pain sensitivity.1 While neck pain is often considered a part of the migraine experience, it's not commonly thought of as a disabling symptom. However, neck pain can be a major aspect of migraine disability.

A systematic review published in August 2024 in the journal Cephalalgia described neck pain disability as a part of migraine. The authors used 33 clinic-based studies that utilized either the Neck Disability Index (NDI) or the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) to define the severity of neck pain disability. They concluded that individuals with migraine had higher NDI and NPRS scores than patients with tension-type headaches and patients without headaches. According to the NDI scoring system, 0–4 points indicate no disability, 5–14 points indicate mild disability, 15–24 points indicate moderate disability, 25–34 points indicate severe disability, and ≥ 35 points indicate complete disability. The authors reported that the mean NDI score for patients with migraine was 16.2, which was approximately 12 points higher than for healthy headache-free control participants.2 This brings to light an issue that can substantially affect patients' quality of life. Patients who have neck pain with migraine may need focused attention to that symptom, in addition to overall migraine therapy, and it is important to ask migraine patients about the degree to which neck pain affects their life. In fact, many patients might not even realize that their neck pain is associated with their migraines.

Cardiovascular disease is another comorbidity that has been inconsistently associated with migraine. A study published in Headache: The Journal of Headache and Face Pain in August 2024 used data from a Danish population-based cohort longitudinal study that included over 140,000 women. The authors reported that migraine was associated with a risk for major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in women aged ≤ 60 years.3

This link has been noted previously, although the studies have been inconsistent regarding how strong the link is, any specific causality, and whether there is a link at all. Potential causes for the possible associations have been attributed to "endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulability, platelet aggregation, vasospasm, cardiovascular risk factors, paradoxical embolism, spreading depolarization, shared genetic risk, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and immobilization."4

Of note, there has also been documentation of a possible negative correlation between migraine and cardiovascular disease. Another article, from The Journal of Headache and Pain, published in August 2024, used data from 873,341 and 554,569 individuals, respectively, in two meta-analyses. The authors reported a potential protective effect of migraine on coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke, and a potential protective effect of coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction on migraine.5

A possible explanation for the conflicting results could lie in heterogeneity of migraine. For example, vestibular migraine is associated with many comorbidities, including anxiety disorders or depressive disorders, sleep disorders, persistent postural-perceptual dizziness, and Meniere disease.6 Given the serious consequences of cardiovascular disease, screening for risk factors could be beneficial for preventing adverse health outcomes for migraine patients. Eventually, further research may reveal more specific correlations between comorbidities and migraine subtypes, rather than generalizing comorbidities to all migraine types.

Sources

- Al-Khazali HM, Krøll LS, Ashina H, et al. Neck pain and headache: Pathophysiology, treatments and future directions. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2023;66:102804. Source

- Al-Khazali HM, Al-Sayegh Z, Younis S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Neck Disability Index and Numeric Pain Rating Scale in patients with migraine and tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2024;44:3331024241274266. Source

- Fuglsang CH, Pedersen L, Schmidt M, Vandenbroucke JP, Bøtker HE, Sørensen HT. The combined impact of migraine and gestational diabetes on long-term risk of premature myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based cohort study. Headache. 2024 Aug 28. Source

- Agostoni EC, Longoni M. Migraine and cerebrovascular disease: still a dangerous connection? Neurol Sci. 2018;39(Suppl 1):33-37. Source

- Duan X, Du X, Zheng G, et al. Causality between migraine and cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. J Headache Pain. 2024;25:130. Source

- Ma YM, Zhang DP, Zhang HL, et al. Why is vestibular migraine associated with many comorbidities? J Neurol. 2024 Sept 20. Source

Head and Neck Cancer: Should Patients Get PEG Access Prior to Therapy? VA pilot study could help clinicians make better-informed decisions to head off malnutrition

Research conducted at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) could offer crucial insight into the hotly debated question of whether patients with head and neck cancer should have access to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) before they develop malnutrition.

While no definitive conclusions can be drawn until a complete study is performed, early findings of a pilot trial are intriguing, said advanced practice oncology dietitian Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO, of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, who spoke in an interview with Federal Practitioner and at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology.

So far, the 12 patients with head and neck cancer who agreed to the placement of prophylactic feeding tubes prior to chemoradiation have had worse outcomes in some areas compared to the 9 patients who had tubes inserted when clinically indicated and the 12 who didn't need feeding tubes.

Petersen cautioned that the study is small and underpowered at this point. Still, she noted, "We're seeing a hint of exactly the opposite of what I expected. Those who get a tube prophylactically are doing worse than those who are getting it reactively or not at all, If that's the case, that's a really important outcome."

As Petersen explained, the placement of PEG feeding tubes is a hot topic in head and neck cancer care. Malnutrition affects about 80% of these patients and can contribute to mortality, raising the question of whether they should have access to feeding tubes placed prior to treatment in case enteral nutrition is needed.

In some patients with head and neck cancer, malnutrition may arise when tumors block food intake or prevent patients from swallowing. "But in my clinical experience, most often it's from the adverse effects of radiation and chemotherapy. Radiation creates burns inside their throat that make it hard to swallow. Or they have taste changes or really dry mouth," Petersen said.

"On top of these problems, chemotherapy can cause nausea and vomiting," she said. Placing feeding tube access may seem like a smart strategy to head off malnutrition as soon as it occurs. But, as Petersen noted, feeding tube use can lead to dependency as patients lose their ability to swallow. "There's a theory that if we give people feeding tubes, they'll go with the easier route of using a feeding tube and not keep swallowing. Then those swallowing muscles would weaken, and patients would end up permanently on a feeding tube."

In 2020, a retrospective VA study linked feeding tube dependence to lower overall survival in head and neck cancer patients. There are also risks to feeding tube placement, such as infection, pain, leakage, and inflammation.

But what if feeding tube valves are inserted prophylactically so they can be used for nutrition if needed? "We just haven't had any prospective studies to get to the heart of the matter and answer the question," she said. "It's hard to recruit. How do you convince somebody to randomly be assigned to have a hole poked in their stomach?"

For the new pilot study, researchers in Phoenix decided not to randomize patients. Instead, they asked them whether they'd accept the placement of feeding tube valves on a prophylactic basis.

Thirty-six veterans enrolled in 3 years, 33% of those were eligible. Twelve have died, 1 withdrew, and 2 were lost to follow-up.

Those in the prophylactic group had worse physical function and muscle strength over time, while those who received feeding tubes when needed had more adverse events.

Why might some outcomes be worse for patients who chose the prophylactic approach? "The answer is unclear," Petersen said. "Although one possibility is that those patients had higher-risk tumors and were more clued into their own risk."

"The goal now is to get funding for an expanded, multicenter study within the VA," Petersen said. The big question that she hopes to answer is: Does a prophylactic approach work? "Does it make a difference for patients in terms of how quickly they go back to living a full, meaningful life and be able to do all the things that they normally would do?"

A complete study would likely last 7 years, but helpful results may come earlier. "We are starting to see significant differences in terms of our main outcomes of physical function," Petersen said. "We only need 1 to 2 years of data for each patient to get to the heart of that."

The study is not funded, and Petersen reported no disclosures.

Research conducted at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) could offer crucial insight into the hotly debated question of whether patients with head and neck cancer should have access to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) before they develop malnutrition.

While no definitive conclusions can be drawn until a complete study is performed, early findings of a pilot trial are intriguing, said advanced practice oncology dietitian Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO, of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, who spoke in an interview with Federal Practitioner and at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology.

So far, the 12 patients with head and neck cancer who agreed to the placement of prophylactic feeding tubes prior to chemoradiation have had worse outcomes in some areas compared to the 9 patients who had tubes inserted when clinically indicated and the 12 who didn't need feeding tubes.

Petersen cautioned that the study is small and underpowered at this point. Still, she noted, "We're seeing a hint of exactly the opposite of what I expected. Those who get a tube prophylactically are doing worse than those who are getting it reactively or not at all, If that's the case, that's a really important outcome."

As Petersen explained, the placement of PEG feeding tubes is a hot topic in head and neck cancer care. Malnutrition affects about 80% of these patients and can contribute to mortality, raising the question of whether they should have access to feeding tubes placed prior to treatment in case enteral nutrition is needed.

In some patients with head and neck cancer, malnutrition may arise when tumors block food intake or prevent patients from swallowing. "But in my clinical experience, most often it's from the adverse effects of radiation and chemotherapy. Radiation creates burns inside their throat that make it hard to swallow. Or they have taste changes or really dry mouth," Petersen said.

"On top of these problems, chemotherapy can cause nausea and vomiting," she said. Placing feeding tube access may seem like a smart strategy to head off malnutrition as soon as it occurs. But, as Petersen noted, feeding tube use can lead to dependency as patients lose their ability to swallow. "There's a theory that if we give people feeding tubes, they'll go with the easier route of using a feeding tube and not keep swallowing. Then those swallowing muscles would weaken, and patients would end up permanently on a feeding tube."

In 2020, a retrospective VA study linked feeding tube dependence to lower overall survival in head and neck cancer patients. There are also risks to feeding tube placement, such as infection, pain, leakage, and inflammation.

But what if feeding tube valves are inserted prophylactically so they can be used for nutrition if needed? "We just haven't had any prospective studies to get to the heart of the matter and answer the question," she said. "It's hard to recruit. How do you convince somebody to randomly be assigned to have a hole poked in their stomach?"

For the new pilot study, researchers in Phoenix decided not to randomize patients. Instead, they asked them whether they'd accept the placement of feeding tube valves on a prophylactic basis.

Thirty-six veterans enrolled in 3 years, 33% of those were eligible. Twelve have died, 1 withdrew, and 2 were lost to follow-up.

Those in the prophylactic group had worse physical function and muscle strength over time, while those who received feeding tubes when needed had more adverse events.

Why might some outcomes be worse for patients who chose the prophylactic approach? "The answer is unclear," Petersen said. "Although one possibility is that those patients had higher-risk tumors and were more clued into their own risk."

"The goal now is to get funding for an expanded, multicenter study within the VA," Petersen said. The big question that she hopes to answer is: Does a prophylactic approach work? "Does it make a difference for patients in terms of how quickly they go back to living a full, meaningful life and be able to do all the things that they normally would do?"

A complete study would likely last 7 years, but helpful results may come earlier. "We are starting to see significant differences in terms of our main outcomes of physical function," Petersen said. "We only need 1 to 2 years of data for each patient to get to the heart of that."

The study is not funded, and Petersen reported no disclosures.

Research conducted at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) could offer crucial insight into the hotly debated question of whether patients with head and neck cancer should have access to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) before they develop malnutrition.

While no definitive conclusions can be drawn until a complete study is performed, early findings of a pilot trial are intriguing, said advanced practice oncology dietitian Katherine Petersen, MS, RDN, CSO, of the Phoenix VA Health Care System, who spoke in an interview with Federal Practitioner and at the annual meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology.

So far, the 12 patients with head and neck cancer who agreed to the placement of prophylactic feeding tubes prior to chemoradiation have had worse outcomes in some areas compared to the 9 patients who had tubes inserted when clinically indicated and the 12 who didn't need feeding tubes.

Petersen cautioned that the study is small and underpowered at this point. Still, she noted, "We're seeing a hint of exactly the opposite of what I expected. Those who get a tube prophylactically are doing worse than those who are getting it reactively or not at all, If that's the case, that's a really important outcome."

As Petersen explained, the placement of PEG feeding tubes is a hot topic in head and neck cancer care. Malnutrition affects about 80% of these patients and can contribute to mortality, raising the question of whether they should have access to feeding tubes placed prior to treatment in case enteral nutrition is needed.

In some patients with head and neck cancer, malnutrition may arise when tumors block food intake or prevent patients from swallowing. "But in my clinical experience, most often it's from the adverse effects of radiation and chemotherapy. Radiation creates burns inside their throat that make it hard to swallow. Or they have taste changes or really dry mouth," Petersen said.

"On top of these problems, chemotherapy can cause nausea and vomiting," she said. Placing feeding tube access may seem like a smart strategy to head off malnutrition as soon as it occurs. But, as Petersen noted, feeding tube use can lead to dependency as patients lose their ability to swallow. "There's a theory that if we give people feeding tubes, they'll go with the easier route of using a feeding tube and not keep swallowing. Then those swallowing muscles would weaken, and patients would end up permanently on a feeding tube."

In 2020, a retrospective VA study linked feeding tube dependence to lower overall survival in head and neck cancer patients. There are also risks to feeding tube placement, such as infection, pain, leakage, and inflammation.

But what if feeding tube valves are inserted prophylactically so they can be used for nutrition if needed? "We just haven't had any prospective studies to get to the heart of the matter and answer the question," she said. "It's hard to recruit. How do you convince somebody to randomly be assigned to have a hole poked in their stomach?"

For the new pilot study, researchers in Phoenix decided not to randomize patients. Instead, they asked them whether they'd accept the placement of feeding tube valves on a prophylactic basis.

Thirty-six veterans enrolled in 3 years, 33% of those were eligible. Twelve have died, 1 withdrew, and 2 were lost to follow-up.

Those in the prophylactic group had worse physical function and muscle strength over time, while those who received feeding tubes when needed had more adverse events.

Why might some outcomes be worse for patients who chose the prophylactic approach? "The answer is unclear," Petersen said. "Although one possibility is that those patients had higher-risk tumors and were more clued into their own risk."

"The goal now is to get funding for an expanded, multicenter study within the VA," Petersen said. The big question that she hopes to answer is: Does a prophylactic approach work? "Does it make a difference for patients in terms of how quickly they go back to living a full, meaningful life and be able to do all the things that they normally would do?"

A complete study would likely last 7 years, but helpful results may come earlier. "We are starting to see significant differences in terms of our main outcomes of physical function," Petersen said. "We only need 1 to 2 years of data for each patient to get to the heart of that."

The study is not funded, and Petersen reported no disclosures.

Commentary: PsA Targeted Therapy Trials, October 2024

Important psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical studies published last month have focused on clinical trials. Several highly efficacious targeted therapies are now available for PsA. However, comparative effectiveness of the various drugs is less well known.

Matching adjusted indirect comparison is one method of evaluating comparative effectiveness. To compare the efficacy between bimekizumab, an interleukin (IL) 17A/F inhibitor and risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, Mease et al conducted such a study using data from four phase 3 trials (BE OPTIMAL, BE COMPLETE, KEEPsAKE-1, and KEEPsAKE-2) involving patients who were biologic-naive or inadequate responders to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors who received bimekizumab (n = 698) or risankizumab (n = 589).1

At week 52, bimekizumab led to a higher likelihood of achieving a ≥ 70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response in patients who were biologic-naive and TNF inhibitor inadequate responders (TNFi-IR), compared with risankizumab. Bimekizumab also had greater odds of achieving minimal disease activity in patients who were TNFi-IR. Thus, bimekizumab may be superior to risankizumab for treating those with PsA. Randomized controlled head-to-head clinical trials are required to confirm these findings.

In regard to long-term safety and efficacy of bimekizumab, Mease et al reported that bimekizumab demonstrated consistent safety and sustained efficacy for up to 2 years in patients with PsA.2 In this open-label extension (BE VITAL) of two phase 3 trials that included biologic-naive (n = 852) and TNFi-IR (n = 400) patients with PsA who were randomly assigned to receive bimekizumab, placebo with crossover to bimekizumab at week 16, or adalimumab followed by bimekizumab at week 52, no new safety signals were noted from weeks 52 to 104,. SARS-CoV-2 infection was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event. Approximately 50% of biologic-naive and TNFi-IR patients maintained a 50% or greater improvement in the ACR response.

Guselkumab, another IL-23 inhibitor, has proven efficacy in treating PsA. Curtis et al investigated the impact of early achievement of improvement with guselkumab and longer-term outcomes.3 This was a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials, DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2, which included 1120 patients with active PsA who received guselkumab every 4 or 8 weeks (Q4W) or placebo with a crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24. The study demonstrated that guselkumab led to early achievement of minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) in clinical disease activity index for PsA (cDAPSA), with higher response rates at week 4 compared with placebo. Moreover, achieving early MCII in cDAPSA was associated with sustained disease control at weeks 24 and 52. Thus, guselkumab treatment achieved MCII in cDAPSA after the first dose and sustained disease control for up to 1 year. Early treatment response and a proven safety record make guselkumab an attractive treatment option for PsA.

PsA clinical trials mostly include patients with polyarthritis. Little is known about treatment efficacy for oligoarticular PsA. To address this gap in knowledge, Gossec et al reported the results of the phase 4 FOREMOST trial that included 308 patients with early (symptom duration 5 years or less) targeted therapy–naive oligoarticular PsA and were randomly assigned to receive apremilast (n = 203) or placebo (n = 105).4 At week 16, a higher proportion of patients receiving apremilast achieved minimal disease activity (joints response) compared with those receiving placebo. No new safety signals were reported. Apremilast is thus efficacious in treating early oligoarticular PsA as well as polyarticular PsA and psoriasis. Similar studies with other targeted therapies will help clinicians better manage early oligoarticular PsA.

References

- Mease PJ, Warren RB, Nash P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab and risankizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis at 52 weeks assessed using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Aug 9. Source

- Mease PJ, Merola JF, Tanaka Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 2-year results from two phase 3 studies. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Aug 31. Source

- Curtis JR, et al. Early improvements with guselkumab associate with sustained control of psoriatic arthritis: post hoc analyses of two phase 3 trials. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Sep 11. Source

- Gossec L, Coates LC, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment of early oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis with apremilast: primary outcomes at week 16 from the FOREMOST randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Sep 16:ard-2024-225833. Source

Important psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical studies published last month have focused on clinical trials. Several highly efficacious targeted therapies are now available for PsA. However, comparative effectiveness of the various drugs is less well known.

Matching adjusted indirect comparison is one method of evaluating comparative effectiveness. To compare the efficacy between bimekizumab, an interleukin (IL) 17A/F inhibitor and risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, Mease et al conducted such a study using data from four phase 3 trials (BE OPTIMAL, BE COMPLETE, KEEPsAKE-1, and KEEPsAKE-2) involving patients who were biologic-naive or inadequate responders to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors who received bimekizumab (n = 698) or risankizumab (n = 589).1

At week 52, bimekizumab led to a higher likelihood of achieving a ≥ 70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response in patients who were biologic-naive and TNF inhibitor inadequate responders (TNFi-IR), compared with risankizumab. Bimekizumab also had greater odds of achieving minimal disease activity in patients who were TNFi-IR. Thus, bimekizumab may be superior to risankizumab for treating those with PsA. Randomized controlled head-to-head clinical trials are required to confirm these findings.

In regard to long-term safety and efficacy of bimekizumab, Mease et al reported that bimekizumab demonstrated consistent safety and sustained efficacy for up to 2 years in patients with PsA.2 In this open-label extension (BE VITAL) of two phase 3 trials that included biologic-naive (n = 852) and TNFi-IR (n = 400) patients with PsA who were randomly assigned to receive bimekizumab, placebo with crossover to bimekizumab at week 16, or adalimumab followed by bimekizumab at week 52, no new safety signals were noted from weeks 52 to 104,. SARS-CoV-2 infection was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event. Approximately 50% of biologic-naive and TNFi-IR patients maintained a 50% or greater improvement in the ACR response.

Guselkumab, another IL-23 inhibitor, has proven efficacy in treating PsA. Curtis et al investigated the impact of early achievement of improvement with guselkumab and longer-term outcomes.3 This was a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials, DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2, which included 1120 patients with active PsA who received guselkumab every 4 or 8 weeks (Q4W) or placebo with a crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24. The study demonstrated that guselkumab led to early achievement of minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) in clinical disease activity index for PsA (cDAPSA), with higher response rates at week 4 compared with placebo. Moreover, achieving early MCII in cDAPSA was associated with sustained disease control at weeks 24 and 52. Thus, guselkumab treatment achieved MCII in cDAPSA after the first dose and sustained disease control for up to 1 year. Early treatment response and a proven safety record make guselkumab an attractive treatment option for PsA.

PsA clinical trials mostly include patients with polyarthritis. Little is known about treatment efficacy for oligoarticular PsA. To address this gap in knowledge, Gossec et al reported the results of the phase 4 FOREMOST trial that included 308 patients with early (symptom duration 5 years or less) targeted therapy–naive oligoarticular PsA and were randomly assigned to receive apremilast (n = 203) or placebo (n = 105).4 At week 16, a higher proportion of patients receiving apremilast achieved minimal disease activity (joints response) compared with those receiving placebo. No new safety signals were reported. Apremilast is thus efficacious in treating early oligoarticular PsA as well as polyarticular PsA and psoriasis. Similar studies with other targeted therapies will help clinicians better manage early oligoarticular PsA.

References

- Mease PJ, Warren RB, Nash P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab and risankizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis at 52 weeks assessed using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Aug 9. Source

- Mease PJ, Merola JF, Tanaka Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 2-year results from two phase 3 studies. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Aug 31. Source

- Curtis JR, et al. Early improvements with guselkumab associate with sustained control of psoriatic arthritis: post hoc analyses of two phase 3 trials. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Sep 11. Source

- Gossec L, Coates LC, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment of early oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis with apremilast: primary outcomes at week 16 from the FOREMOST randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Sep 16:ard-2024-225833. Source

Important psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical studies published last month have focused on clinical trials. Several highly efficacious targeted therapies are now available for PsA. However, comparative effectiveness of the various drugs is less well known.

Matching adjusted indirect comparison is one method of evaluating comparative effectiveness. To compare the efficacy between bimekizumab, an interleukin (IL) 17A/F inhibitor and risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, Mease et al conducted such a study using data from four phase 3 trials (BE OPTIMAL, BE COMPLETE, KEEPsAKE-1, and KEEPsAKE-2) involving patients who were biologic-naive or inadequate responders to tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors who received bimekizumab (n = 698) or risankizumab (n = 589).1

At week 52, bimekizumab led to a higher likelihood of achieving a ≥ 70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response in patients who were biologic-naive and TNF inhibitor inadequate responders (TNFi-IR), compared with risankizumab. Bimekizumab also had greater odds of achieving minimal disease activity in patients who were TNFi-IR. Thus, bimekizumab may be superior to risankizumab for treating those with PsA. Randomized controlled head-to-head clinical trials are required to confirm these findings.

In regard to long-term safety and efficacy of bimekizumab, Mease et al reported that bimekizumab demonstrated consistent safety and sustained efficacy for up to 2 years in patients with PsA.2 In this open-label extension (BE VITAL) of two phase 3 trials that included biologic-naive (n = 852) and TNFi-IR (n = 400) patients with PsA who were randomly assigned to receive bimekizumab, placebo with crossover to bimekizumab at week 16, or adalimumab followed by bimekizumab at week 52, no new safety signals were noted from weeks 52 to 104,. SARS-CoV-2 infection was the most common treatment-emergent adverse event. Approximately 50% of biologic-naive and TNFi-IR patients maintained a 50% or greater improvement in the ACR response.

Guselkumab, another IL-23 inhibitor, has proven efficacy in treating PsA. Curtis et al investigated the impact of early achievement of improvement with guselkumab and longer-term outcomes.3 This was a post hoc analysis of two phase 3 trials, DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2, which included 1120 patients with active PsA who received guselkumab every 4 or 8 weeks (Q4W) or placebo with a crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24. The study demonstrated that guselkumab led to early achievement of minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) in clinical disease activity index for PsA (cDAPSA), with higher response rates at week 4 compared with placebo. Moreover, achieving early MCII in cDAPSA was associated with sustained disease control at weeks 24 and 52. Thus, guselkumab treatment achieved MCII in cDAPSA after the first dose and sustained disease control for up to 1 year. Early treatment response and a proven safety record make guselkumab an attractive treatment option for PsA.

PsA clinical trials mostly include patients with polyarthritis. Little is known about treatment efficacy for oligoarticular PsA. To address this gap in knowledge, Gossec et al reported the results of the phase 4 FOREMOST trial that included 308 patients with early (symptom duration 5 years or less) targeted therapy–naive oligoarticular PsA and were randomly assigned to receive apremilast (n = 203) or placebo (n = 105).4 At week 16, a higher proportion of patients receiving apremilast achieved minimal disease activity (joints response) compared with those receiving placebo. No new safety signals were reported. Apremilast is thus efficacious in treating early oligoarticular PsA as well as polyarticular PsA and psoriasis. Similar studies with other targeted therapies will help clinicians better manage early oligoarticular PsA.

References

- Mease PJ, Warren RB, Nash P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab and risankizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis at 52 weeks assessed using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Aug 9. Source

- Mease PJ, Merola JF, Tanaka Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 2-year results from two phase 3 studies. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Aug 31. Source

- Curtis JR, et al. Early improvements with guselkumab associate with sustained control of psoriatic arthritis: post hoc analyses of two phase 3 trials. Rheumatol Ther. 2024 Sep 11. Source

- Gossec L, Coates LC, Gladman DD, et al. Treatment of early oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis with apremilast: primary outcomes at week 16 from the FOREMOST randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024 Sep 16:ard-2024-225833. Source

A Rare Case of a Splenic Abscess as the Origin of Illness in Exudative Pleural Effusion

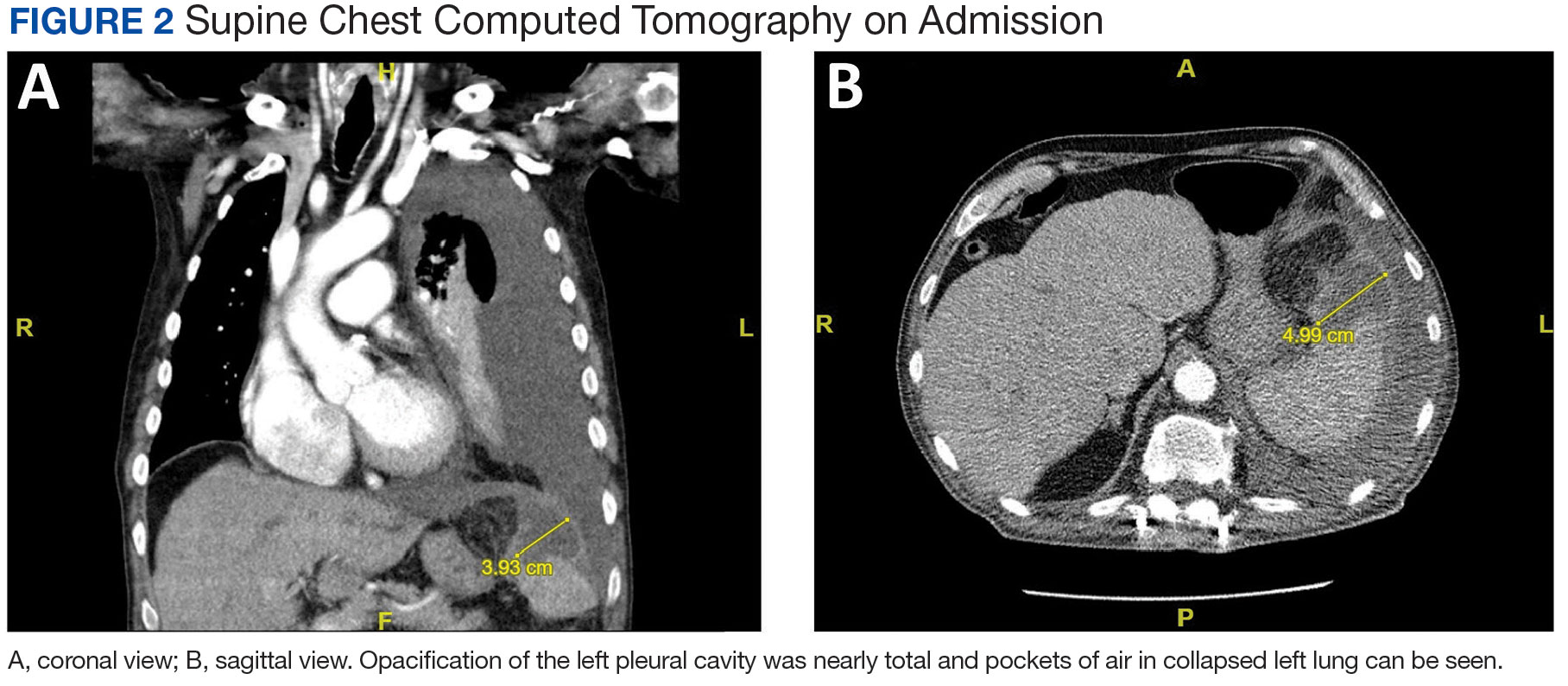

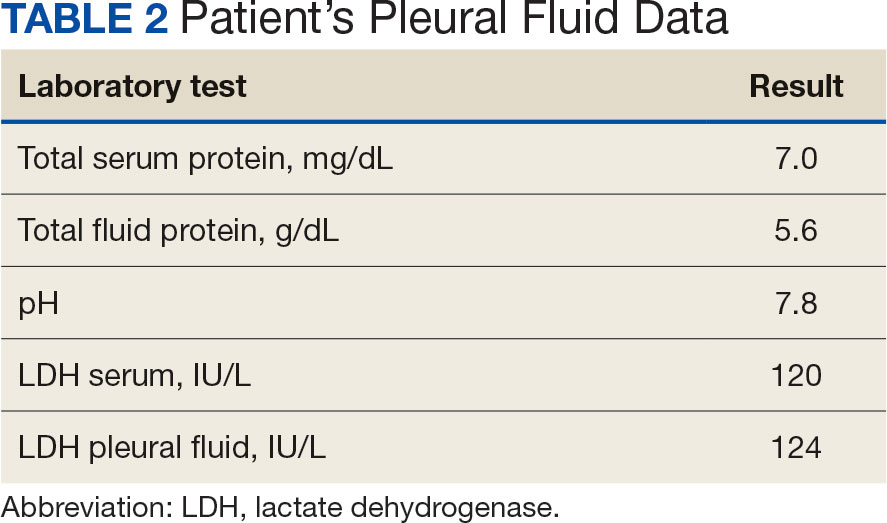

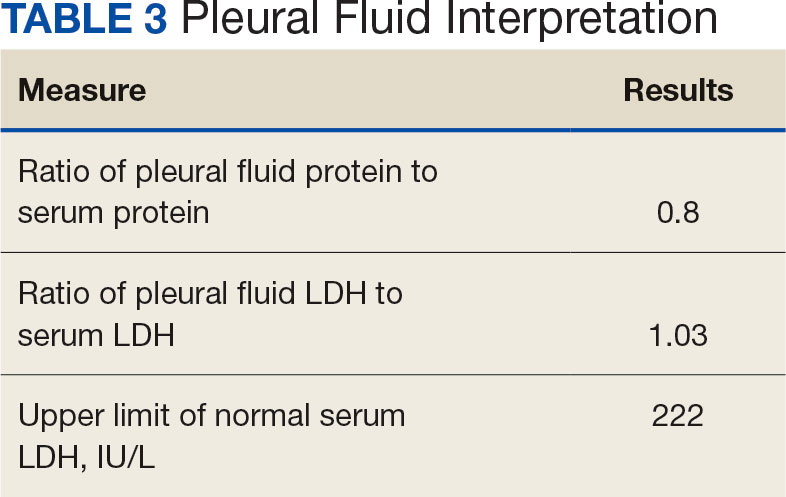

Splenic abscesses are a rare occurrence that represent a marginal proportion of intra-abdominal infections. One study found splenic abscesses in only 0.14% to 0.70% of autopsies and none of the 540 abdominal abscesses they examined originated in the spleen.1 Patients with splenic abscesses tend to present with nonspecific symptoms such as fevers, chills, and abdominal pain.2 Imaging modalities such as abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) are vital to the workup and diagnosis identification.2 Splenic abscesses are generally associated with another underlying process, as seen in patients who are affected by endocarditis, trauma, metastatic infection, splenic infarction, or neoplasia.2

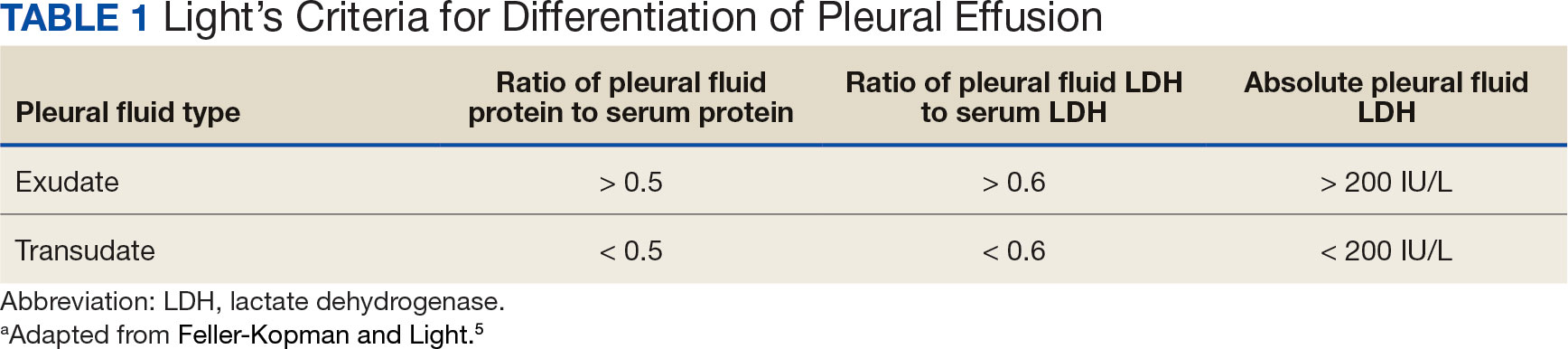

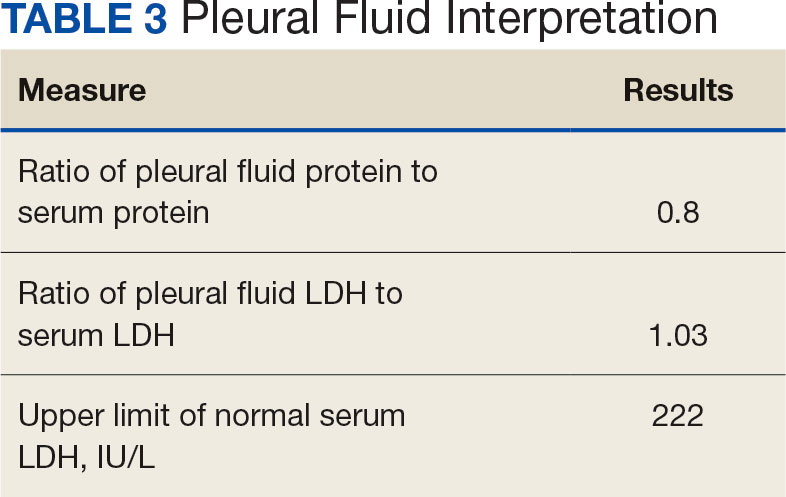

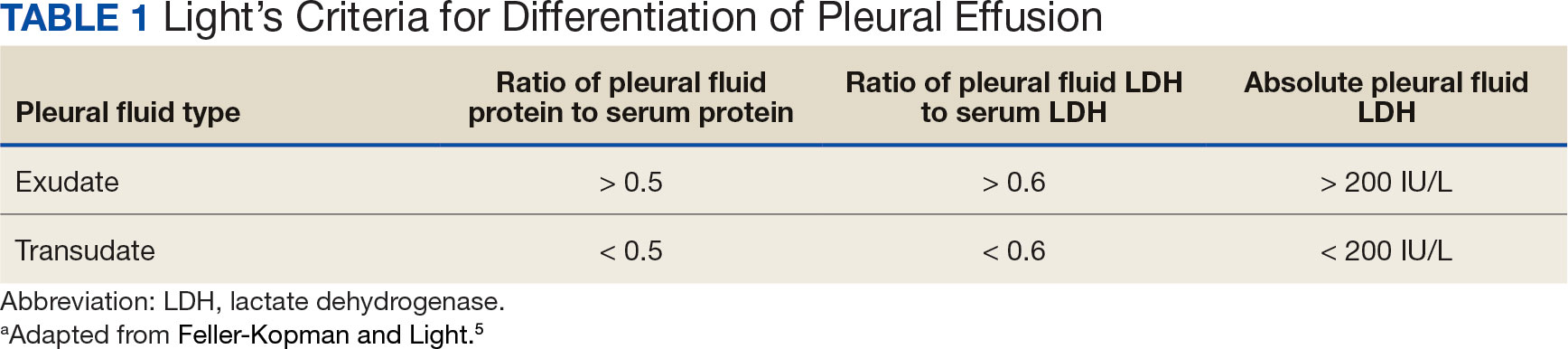

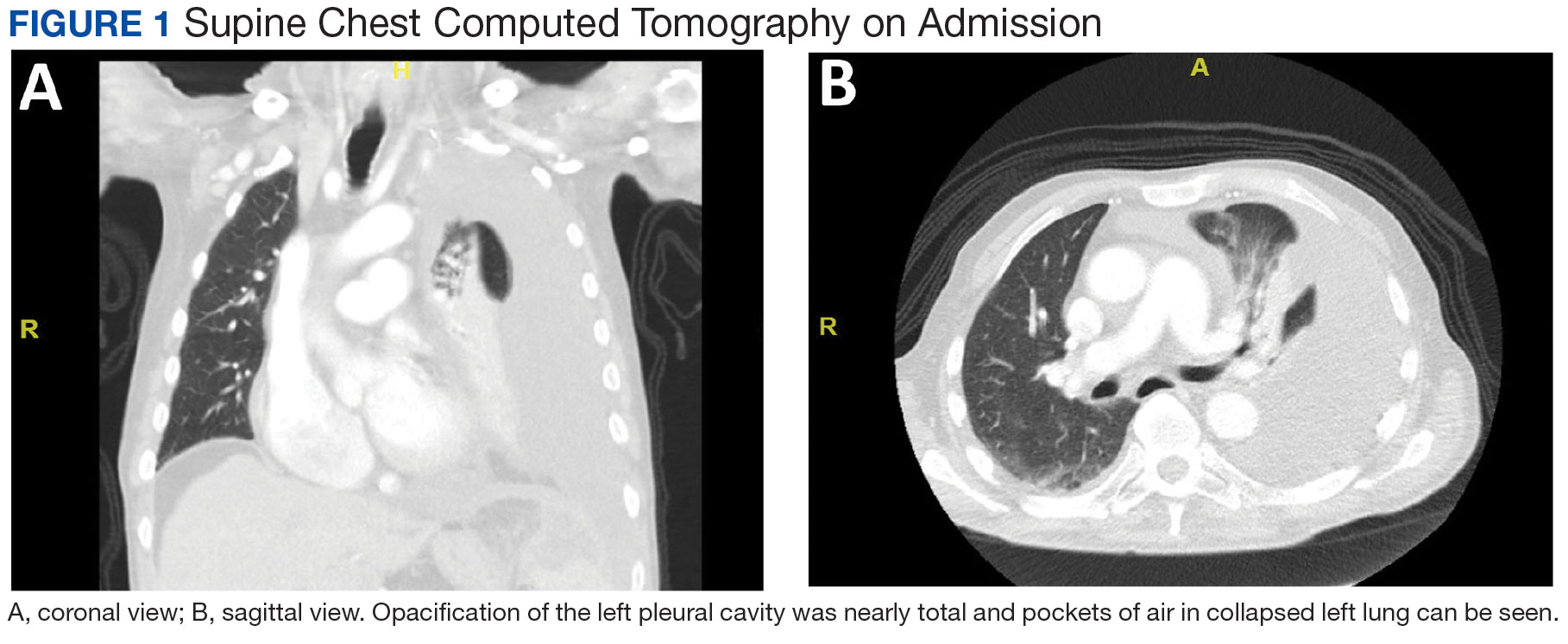

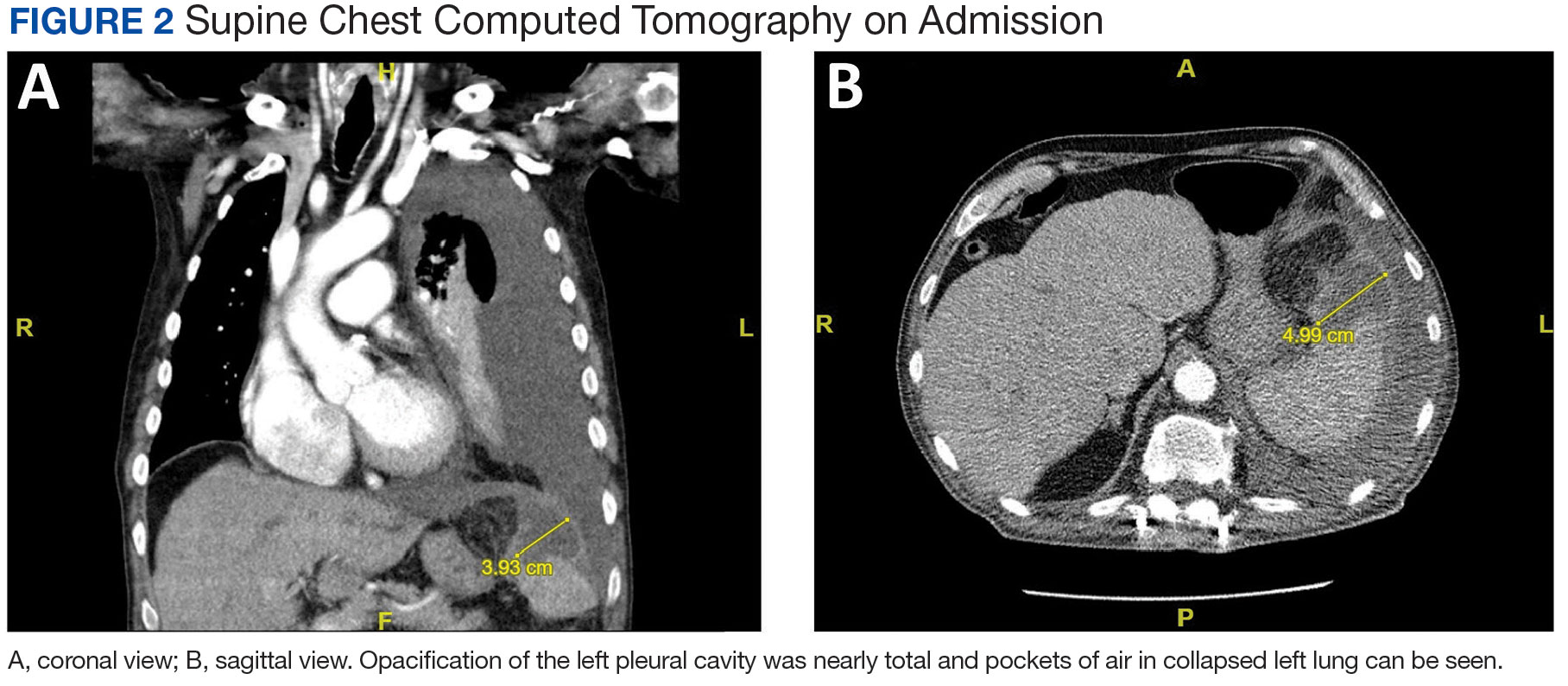

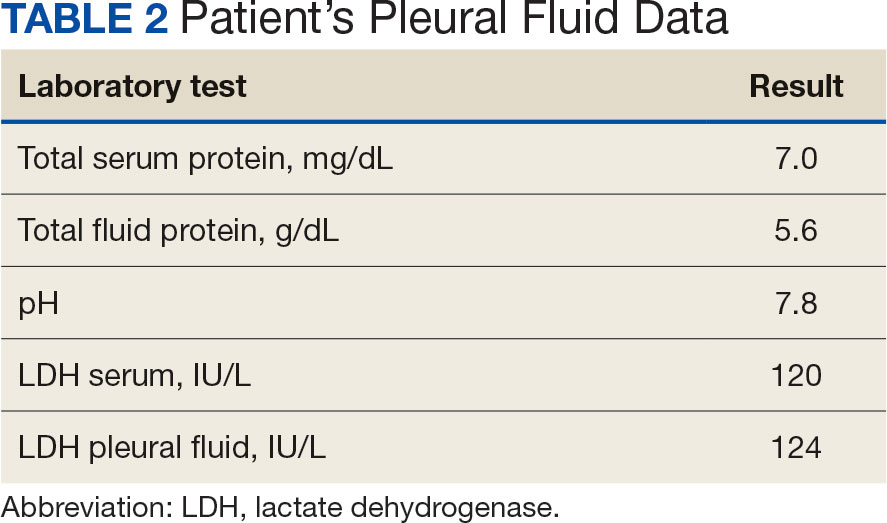

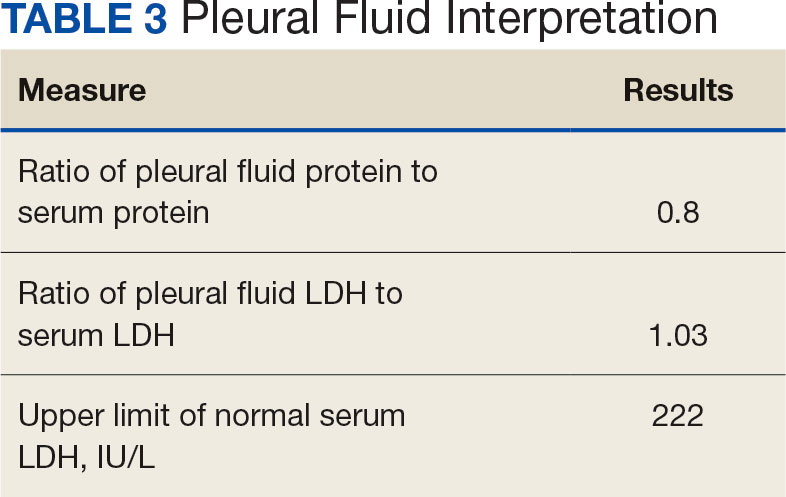

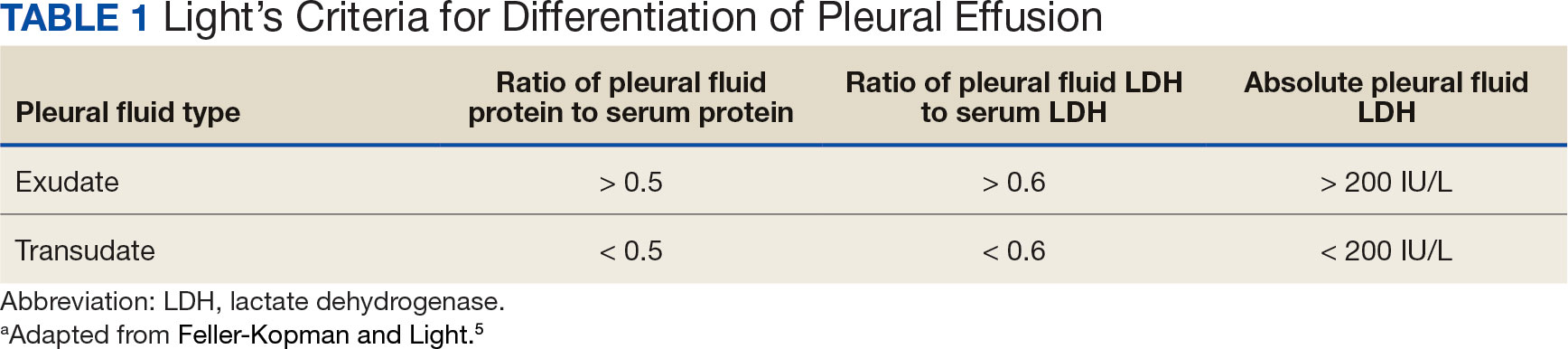

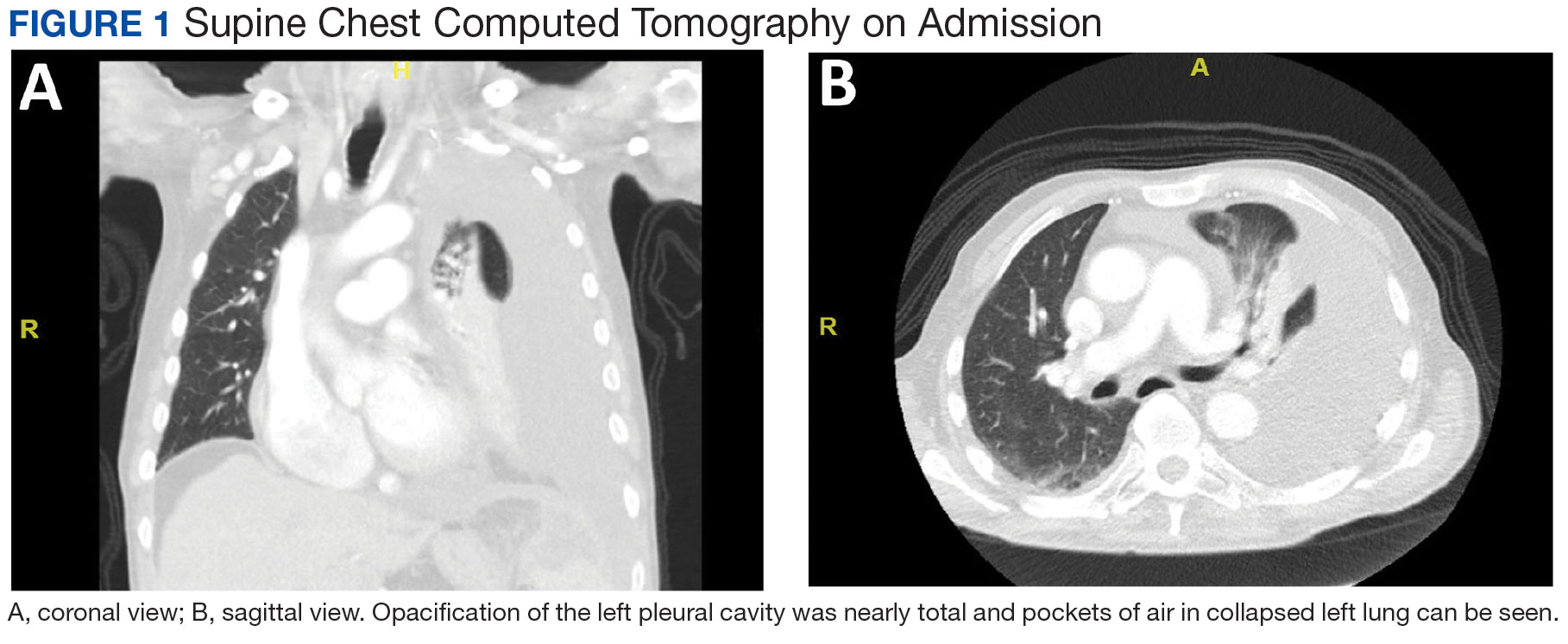

Pleural effusions, or the buildup of fluid within the pleural space, is a common condition typically secondary to another disease.3 Clinical identification of the primary condition may be challenging.3 In the absence of a clear etiology, such as obvious signs of congestive heart failure, further differentiation relies upon pleural fluid analysis, beginning with the distinction between exudate (inflammatory) and transudate (noninflammatory). 3,4 This distinction can be made using Light’s criteria, which relies on protein and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) ratios between the pleural fluid and serum (Table 1).5 Though rare, half of splenic abscesses are associated with pleural effusion.6 As an inflammatory condition, splenic abscesses have been classically described as a cause of exudative pleural effusions.5,6