User login

Will New Obesity Drugs Make Bariatric Surgery Obsolete?

MADRID — In spirited presentations at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Louis J. Aronne, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, made a compelling case that the next generation of obesity medications will make bariatric surgery obsolete, and Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London in England, made an equally compelling case that they will not.

In fact, Dr. Rubino predicted that “metabolic” surgery — new nomenclature reflecting the power of surgery to reduce not only obesity, but also other metabolic conditions, over the long term — will continue and could even increase in years to come.

‘Medical Treatment Will Dominate’

“Obesity treatment is the superhero of treating metabolic disease because it can defeat all of the bad guys at once, not just one, like the other treatments,” Dr. Aronne told meeting attendees. “If you treat somebody’s cholesterol, you’re just treating their cholesterol, and you may actually increase their risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). You treat their blood pressure, you don’t treat their glucose and you don’t treat their lipids — the list goes on and on and on. But by treating obesity, if you can get enough weight loss, you can get all those things at once.”

He pointed to the SELECT trial, which showed that treating obesity with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist reduced major adverse cardiovascular events as well as death from any cause, results in line with those from other modes of treatment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) or lipid lowering, he said. “But we get much more with these drugs, including positive effects on heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a 73% reduction in T2D. So, we’re now on the verge of a major change in the way we manage metabolic disease.”

Dr. Aronne drew a parallel between treating obesity and the historic way of treating hypertension. Years ago, he said, “we waited too long to treat people. We waited until they had severe hypertension that in many cases was irreversible. What would you prefer to do now for obesity — have the patient lose weight with a medicine that is proven to reduce complications or wait until they develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and then have them undergo surgery to treat that?”

Looking ahead, “the trend could be to treat obesity before it gets out of hand,” he suggested. Treatment might start in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2, who would be treated to a target BMI of 25. “That’s only a 10% or so change, but our goal would be to keep them in the normal range so they never go above that target. In fact, I think we’re going to be looking at people with severe obesity in a few years and saying, ‘I can’t believe someone didn’t treat that guy earlier.’ What’s going to happen to bariatric surgery if no one gets to a higher weight?”

The plethora of current weight-loss drugs and the large group on the horizon mean that if someone doesn’t respond to one drug, there will be plenty of other choices, Dr. Aronne continued. People will be referred for surgery, but possibly only after they’ve not responded to medical treatment — or just the opposite. “In the United States, it’s much cheaper to have surgery, and I bet the insurance companies are going to make people have surgery before they can get the medicines,” he acknowledged.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley suggests that the global market for the newer weight-loss drugs could increase by 15-fold over the next 5 years as their benefits expand beyond weight loss and that as much as 9% of the US population will be taking the drugs by 2035, Dr. Aronne said, adding that he thinks 9% is an underestimate. By contrast, the number of patients treated by his team’s surgical program is down about 20%.

“I think it’s very clear that medical treatment is going to dominate,” he concluded. “But, it’s also possible that surgery could go up because so many people are going to be coming for medical therapy that we may wind up referring more for surgical therapy.”

‘Surgery Is Saving Lives’

Dr. Rubino is convinced that anti-obesity drugs will not make surgery obsolete, “but it will not be business as usual,” he told meeting attendees. “In fact, I think these drugs will expedite a process that is already ongoing — a transformation of bariatric into metabolic surgery.”

“Bariatric surgery will go down in history as one of the biggest missed opportunities that we, as medical professionals, have seen over the past many years,” he said. “It has been shown beyond any doubt to reduce all-cause mortality — in other words, it saves lives,” and it’s also cost effective and improves quality of life. Yet, fewer than 1% of people globally who meet the criteria actually get the surgery.

Many clinicians don’t inform patients about the treatment and don’t refer them for it, he said. “That would be equivalent to having surgery for CVD [cardiovascular disease], cancer, or other important diseases available but not being accessed as they should be.”

A big reason for the dearth of procedures is that people have unrealistic expectations about diet and exercise interventions for weight loss, he said. His team’s survey, presented at the 26th World Congress of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, showed that 43% of respondents believed diet and exercise was the best treatment for severe obesity (BMI > 35). A more recent survey asked which among several choices was the most effective weight-loss intervention, and again a large proportion “believed wrongly that diet and exercise is most effective — more so than drugs or surgery — despite plenty of evidence that this is not the case.”

In this context, he said, “any surgery, no matter how safe or effective, would never be very popular.” If obesity is viewed as a modifiable risk factor, patients may say they’ll think about it for 6 months. In contrast, “nobody will tell you ‘I will think about it’ if you tell them they need gallbladder surgery to get rid of gallstone pain.”

Although drugs are available to treat obesity, none of them are curative, and if they’re stopped, the weight comes back, Dr. Rubino pointed out. “Efficacy of drugs is measured in weeks or months, whereas efficacy of surgery is measured in decades of durability — in the case of bariatric surgery, 10-20 years. That’s why bariatric surgery will remain an option,” he said. “It’s not just preventing disease, it’s resolving ongoing disease.”

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is showing value for people with established T2D, whereas in the past, it was mainly considered to be a weight-loss intervention for younger, healthier patients, he said. “In my practice, we’re operating more often in people with T2D, even those at higher risk for anesthesia and surgery — eg, patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, on dialysis — and we’re still able to maintain the same safety with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that we had with healthier patients.”

A vote held at the end of the session revealed that the audience was split about half and half in favor of drugs making bariatric surgery obsolete or not.

“I think we may have to duke it out now,” Dr. Aronne quipped.

Dr. Aronne disclosed being a consultant, speaker, and adviser for and receiving research support from Altimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Intellihealth, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Senda, UnitedHealth Group, Versanis, and others; he has ownership interests in ERX, Intellihealth, Jamieson, Kallyope, Skye Bioscience, Veru, and others; and he is on the board of directors of ERX, Jamieson Wellness, and Intellihealth/FlyteHealth. Dr. Rubino disclosed receiving research and educational grants from Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic; he is on the scientific advisory board/data safety advisory board for Keyron, Morphic Medical, and GT Metabolic Solutions; he receives speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Ethicon, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; and he is president of the nonprofit Metabolic Health Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID — In spirited presentations at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Louis J. Aronne, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, made a compelling case that the next generation of obesity medications will make bariatric surgery obsolete, and Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London in England, made an equally compelling case that they will not.

In fact, Dr. Rubino predicted that “metabolic” surgery — new nomenclature reflecting the power of surgery to reduce not only obesity, but also other metabolic conditions, over the long term — will continue and could even increase in years to come.

‘Medical Treatment Will Dominate’

“Obesity treatment is the superhero of treating metabolic disease because it can defeat all of the bad guys at once, not just one, like the other treatments,” Dr. Aronne told meeting attendees. “If you treat somebody’s cholesterol, you’re just treating their cholesterol, and you may actually increase their risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). You treat their blood pressure, you don’t treat their glucose and you don’t treat their lipids — the list goes on and on and on. But by treating obesity, if you can get enough weight loss, you can get all those things at once.”

He pointed to the SELECT trial, which showed that treating obesity with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist reduced major adverse cardiovascular events as well as death from any cause, results in line with those from other modes of treatment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) or lipid lowering, he said. “But we get much more with these drugs, including positive effects on heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a 73% reduction in T2D. So, we’re now on the verge of a major change in the way we manage metabolic disease.”

Dr. Aronne drew a parallel between treating obesity and the historic way of treating hypertension. Years ago, he said, “we waited too long to treat people. We waited until they had severe hypertension that in many cases was irreversible. What would you prefer to do now for obesity — have the patient lose weight with a medicine that is proven to reduce complications or wait until they develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and then have them undergo surgery to treat that?”

Looking ahead, “the trend could be to treat obesity before it gets out of hand,” he suggested. Treatment might start in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2, who would be treated to a target BMI of 25. “That’s only a 10% or so change, but our goal would be to keep them in the normal range so they never go above that target. In fact, I think we’re going to be looking at people with severe obesity in a few years and saying, ‘I can’t believe someone didn’t treat that guy earlier.’ What’s going to happen to bariatric surgery if no one gets to a higher weight?”

The plethora of current weight-loss drugs and the large group on the horizon mean that if someone doesn’t respond to one drug, there will be plenty of other choices, Dr. Aronne continued. People will be referred for surgery, but possibly only after they’ve not responded to medical treatment — or just the opposite. “In the United States, it’s much cheaper to have surgery, and I bet the insurance companies are going to make people have surgery before they can get the medicines,” he acknowledged.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley suggests that the global market for the newer weight-loss drugs could increase by 15-fold over the next 5 years as their benefits expand beyond weight loss and that as much as 9% of the US population will be taking the drugs by 2035, Dr. Aronne said, adding that he thinks 9% is an underestimate. By contrast, the number of patients treated by his team’s surgical program is down about 20%.

“I think it’s very clear that medical treatment is going to dominate,” he concluded. “But, it’s also possible that surgery could go up because so many people are going to be coming for medical therapy that we may wind up referring more for surgical therapy.”

‘Surgery Is Saving Lives’

Dr. Rubino is convinced that anti-obesity drugs will not make surgery obsolete, “but it will not be business as usual,” he told meeting attendees. “In fact, I think these drugs will expedite a process that is already ongoing — a transformation of bariatric into metabolic surgery.”

“Bariatric surgery will go down in history as one of the biggest missed opportunities that we, as medical professionals, have seen over the past many years,” he said. “It has been shown beyond any doubt to reduce all-cause mortality — in other words, it saves lives,” and it’s also cost effective and improves quality of life. Yet, fewer than 1% of people globally who meet the criteria actually get the surgery.

Many clinicians don’t inform patients about the treatment and don’t refer them for it, he said. “That would be equivalent to having surgery for CVD [cardiovascular disease], cancer, or other important diseases available but not being accessed as they should be.”

A big reason for the dearth of procedures is that people have unrealistic expectations about diet and exercise interventions for weight loss, he said. His team’s survey, presented at the 26th World Congress of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, showed that 43% of respondents believed diet and exercise was the best treatment for severe obesity (BMI > 35). A more recent survey asked which among several choices was the most effective weight-loss intervention, and again a large proportion “believed wrongly that diet and exercise is most effective — more so than drugs or surgery — despite plenty of evidence that this is not the case.”

In this context, he said, “any surgery, no matter how safe or effective, would never be very popular.” If obesity is viewed as a modifiable risk factor, patients may say they’ll think about it for 6 months. In contrast, “nobody will tell you ‘I will think about it’ if you tell them they need gallbladder surgery to get rid of gallstone pain.”

Although drugs are available to treat obesity, none of them are curative, and if they’re stopped, the weight comes back, Dr. Rubino pointed out. “Efficacy of drugs is measured in weeks or months, whereas efficacy of surgery is measured in decades of durability — in the case of bariatric surgery, 10-20 years. That’s why bariatric surgery will remain an option,” he said. “It’s not just preventing disease, it’s resolving ongoing disease.”

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is showing value for people with established T2D, whereas in the past, it was mainly considered to be a weight-loss intervention for younger, healthier patients, he said. “In my practice, we’re operating more often in people with T2D, even those at higher risk for anesthesia and surgery — eg, patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, on dialysis — and we’re still able to maintain the same safety with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that we had with healthier patients.”

A vote held at the end of the session revealed that the audience was split about half and half in favor of drugs making bariatric surgery obsolete or not.

“I think we may have to duke it out now,” Dr. Aronne quipped.

Dr. Aronne disclosed being a consultant, speaker, and adviser for and receiving research support from Altimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Intellihealth, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Senda, UnitedHealth Group, Versanis, and others; he has ownership interests in ERX, Intellihealth, Jamieson, Kallyope, Skye Bioscience, Veru, and others; and he is on the board of directors of ERX, Jamieson Wellness, and Intellihealth/FlyteHealth. Dr. Rubino disclosed receiving research and educational grants from Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic; he is on the scientific advisory board/data safety advisory board for Keyron, Morphic Medical, and GT Metabolic Solutions; he receives speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Ethicon, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; and he is president of the nonprofit Metabolic Health Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID — In spirited presentations at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Louis J. Aronne, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, made a compelling case that the next generation of obesity medications will make bariatric surgery obsolete, and Francesco Rubino, MD, of King’s College London in England, made an equally compelling case that they will not.

In fact, Dr. Rubino predicted that “metabolic” surgery — new nomenclature reflecting the power of surgery to reduce not only obesity, but also other metabolic conditions, over the long term — will continue and could even increase in years to come.

‘Medical Treatment Will Dominate’

“Obesity treatment is the superhero of treating metabolic disease because it can defeat all of the bad guys at once, not just one, like the other treatments,” Dr. Aronne told meeting attendees. “If you treat somebody’s cholesterol, you’re just treating their cholesterol, and you may actually increase their risk of developing type 2 diabetes (T2D). You treat their blood pressure, you don’t treat their glucose and you don’t treat their lipids — the list goes on and on and on. But by treating obesity, if you can get enough weight loss, you can get all those things at once.”

He pointed to the SELECT trial, which showed that treating obesity with a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist reduced major adverse cardiovascular events as well as death from any cause, results in line with those from other modes of treatment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) or lipid lowering, he said. “But we get much more with these drugs, including positive effects on heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and a 73% reduction in T2D. So, we’re now on the verge of a major change in the way we manage metabolic disease.”

Dr. Aronne drew a parallel between treating obesity and the historic way of treating hypertension. Years ago, he said, “we waited too long to treat people. We waited until they had severe hypertension that in many cases was irreversible. What would you prefer to do now for obesity — have the patient lose weight with a medicine that is proven to reduce complications or wait until they develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and then have them undergo surgery to treat that?”

Looking ahead, “the trend could be to treat obesity before it gets out of hand,” he suggested. Treatment might start in people with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m2, who would be treated to a target BMI of 25. “That’s only a 10% or so change, but our goal would be to keep them in the normal range so they never go above that target. In fact, I think we’re going to be looking at people with severe obesity in a few years and saying, ‘I can’t believe someone didn’t treat that guy earlier.’ What’s going to happen to bariatric surgery if no one gets to a higher weight?”

The plethora of current weight-loss drugs and the large group on the horizon mean that if someone doesn’t respond to one drug, there will be plenty of other choices, Dr. Aronne continued. People will be referred for surgery, but possibly only after they’ve not responded to medical treatment — or just the opposite. “In the United States, it’s much cheaper to have surgery, and I bet the insurance companies are going to make people have surgery before they can get the medicines,” he acknowledged.

A recent report from Morgan Stanley suggests that the global market for the newer weight-loss drugs could increase by 15-fold over the next 5 years as their benefits expand beyond weight loss and that as much as 9% of the US population will be taking the drugs by 2035, Dr. Aronne said, adding that he thinks 9% is an underestimate. By contrast, the number of patients treated by his team’s surgical program is down about 20%.

“I think it’s very clear that medical treatment is going to dominate,” he concluded. “But, it’s also possible that surgery could go up because so many people are going to be coming for medical therapy that we may wind up referring more for surgical therapy.”

‘Surgery Is Saving Lives’

Dr. Rubino is convinced that anti-obesity drugs will not make surgery obsolete, “but it will not be business as usual,” he told meeting attendees. “In fact, I think these drugs will expedite a process that is already ongoing — a transformation of bariatric into metabolic surgery.”

“Bariatric surgery will go down in history as one of the biggest missed opportunities that we, as medical professionals, have seen over the past many years,” he said. “It has been shown beyond any doubt to reduce all-cause mortality — in other words, it saves lives,” and it’s also cost effective and improves quality of life. Yet, fewer than 1% of people globally who meet the criteria actually get the surgery.

Many clinicians don’t inform patients about the treatment and don’t refer them for it, he said. “That would be equivalent to having surgery for CVD [cardiovascular disease], cancer, or other important diseases available but not being accessed as they should be.”

A big reason for the dearth of procedures is that people have unrealistic expectations about diet and exercise interventions for weight loss, he said. His team’s survey, presented at the 26th World Congress of the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, showed that 43% of respondents believed diet and exercise was the best treatment for severe obesity (BMI > 35). A more recent survey asked which among several choices was the most effective weight-loss intervention, and again a large proportion “believed wrongly that diet and exercise is most effective — more so than drugs or surgery — despite plenty of evidence that this is not the case.”

In this context, he said, “any surgery, no matter how safe or effective, would never be very popular.” If obesity is viewed as a modifiable risk factor, patients may say they’ll think about it for 6 months. In contrast, “nobody will tell you ‘I will think about it’ if you tell them they need gallbladder surgery to get rid of gallstone pain.”

Although drugs are available to treat obesity, none of them are curative, and if they’re stopped, the weight comes back, Dr. Rubino pointed out. “Efficacy of drugs is measured in weeks or months, whereas efficacy of surgery is measured in decades of durability — in the case of bariatric surgery, 10-20 years. That’s why bariatric surgery will remain an option,” he said. “It’s not just preventing disease, it’s resolving ongoing disease.”

Furthermore, bariatric surgery is showing value for people with established T2D, whereas in the past, it was mainly considered to be a weight-loss intervention for younger, healthier patients, he said. “In my practice, we’re operating more often in people with T2D, even those at higher risk for anesthesia and surgery — eg, patients with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, on dialysis — and we’re still able to maintain the same safety with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery that we had with healthier patients.”

A vote held at the end of the session revealed that the audience was split about half and half in favor of drugs making bariatric surgery obsolete or not.

“I think we may have to duke it out now,” Dr. Aronne quipped.

Dr. Aronne disclosed being a consultant, speaker, and adviser for and receiving research support from Altimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Intellihealth, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Senda, UnitedHealth Group, Versanis, and others; he has ownership interests in ERX, Intellihealth, Jamieson, Kallyope, Skye Bioscience, Veru, and others; and he is on the board of directors of ERX, Jamieson Wellness, and Intellihealth/FlyteHealth. Dr. Rubino disclosed receiving research and educational grants from Novo Nordisk, Ethicon, and Medtronic; he is on the scientific advisory board/data safety advisory board for Keyron, Morphic Medical, and GT Metabolic Solutions; he receives speaking honoraria from Medtronic, Ethicon, Novo Nordisk, and Eli Lilly; and he is president of the nonprofit Metabolic Health Institute.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EASD 2024

Hot Flashes: Do They Predict CVD and Dementia?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to talk about a recent report in the journal Menopause linking menopausal symptoms to increased risk for cognitive impairment. I’d also like to discuss some of the recent studies that have addressed whether hot flashes are linked to increased risk for heart disease and other forms of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Given that 75%-80% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women have hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, it’s undoubtedly a more complex relationship between hot flashes and these outcomes than a simple one-size-fits-all, yes-or-no question.

Increasing evidence shows that several additional factors are important, including the age at which the symptoms are occurring, the time since menopause, the severity of the symptoms, whether they co-occur with night sweats and sleep disruption, and the cardiovascular status of the woman.

Several studies suggest that women who have more severe hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms are more likely to have prevalent cardiovascular risk factors — hypertension, dyslipidemia, high body mass index, endothelial dysfunction — as measured by flow-mediated vasodilation and other measures.

It is quite plausible that hot flashes could be a marker for increased risk for cognitive impairment. But the question remains, are hot flashes associated with cognitive impairment independent of these other risk factors? It appears that the associations between hot flashes, vasomotor symptoms, and CVD, and other adverse outcomes, may be more likely when hot flashes persist after age 60 or are newly occurring in later menopause. In the Women’s Health Initiative observational study, the presence of hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms in early menopause was not linked to any increased risk for heart attack, stroke, total CVD, or all-cause mortality.

However, the onset of these symptoms, especially new onset of these symptoms after age 60 or in later menopause, was in fact linked to increased risk for CVD and all-cause mortality. With respect to cognitive impairment, if a woman is having hot flashes and night sweats with regular sleep disruption, performance on cognitive testing would not be as favorable as it would be in the absence of these symptoms.

This brings us to the new study in Menopause that included approximately 1300 Latino women in nine Latin American countries, with an average age of 55 years. Looking at the association between severe menopausal symptoms and cognitive impairment, researchers found that women with severe symptoms were more likely to have cognitive impairment.

Conversely, they found that the women who had a favorable CVD risk factor status (physically active, lower BMI, healthier) and were ever users of estrogen were less likely to have cognitive impairment.

Clearly, for estrogen therapy, we need randomized clinical trials of the presence or absence of vasomotor symptoms and cognitive and CVD outcomes. Such analyses are ongoing, and new randomized trials focused specifically on women in early menopause would be very beneficial.

At the present time, it’s important that we not alarm women about the associations seen in some of these studies because often they are not independent associations; they aren’t independent of other risk factors that are commonly linked to hot flashes and night sweats. There are many other complexities in the relationship between hot flashes and cognitive impairment.

We need to appreciate that women who have moderate to severe hot flashes (especially when associated with disrupted sleep) do have impaired quality of life. It’s important to treat these symptoms, especially in early menopause, and very effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatments are available.

For women with symptoms that persist into later menopause or who have new onset of symptoms in later menopause, it’s important to prioritize cardiovascular health. For example, be more vigilant about behavioral lifestyle counseling to lower risk, and be even more aggressive in treating dyslipidemia and diabetes.

JoAnn E. Manson, Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School; Chief, Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; and Past President, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to talk about a recent report in the journal Menopause linking menopausal symptoms to increased risk for cognitive impairment. I’d also like to discuss some of the recent studies that have addressed whether hot flashes are linked to increased risk for heart disease and other forms of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Given that 75%-80% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women have hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, it’s undoubtedly a more complex relationship between hot flashes and these outcomes than a simple one-size-fits-all, yes-or-no question.

Increasing evidence shows that several additional factors are important, including the age at which the symptoms are occurring, the time since menopause, the severity of the symptoms, whether they co-occur with night sweats and sleep disruption, and the cardiovascular status of the woman.

Several studies suggest that women who have more severe hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms are more likely to have prevalent cardiovascular risk factors — hypertension, dyslipidemia, high body mass index, endothelial dysfunction — as measured by flow-mediated vasodilation and other measures.

It is quite plausible that hot flashes could be a marker for increased risk for cognitive impairment. But the question remains, are hot flashes associated with cognitive impairment independent of these other risk factors? It appears that the associations between hot flashes, vasomotor symptoms, and CVD, and other adverse outcomes, may be more likely when hot flashes persist after age 60 or are newly occurring in later menopause. In the Women’s Health Initiative observational study, the presence of hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms in early menopause was not linked to any increased risk for heart attack, stroke, total CVD, or all-cause mortality.

However, the onset of these symptoms, especially new onset of these symptoms after age 60 or in later menopause, was in fact linked to increased risk for CVD and all-cause mortality. With respect to cognitive impairment, if a woman is having hot flashes and night sweats with regular sleep disruption, performance on cognitive testing would not be as favorable as it would be in the absence of these symptoms.

This brings us to the new study in Menopause that included approximately 1300 Latino women in nine Latin American countries, with an average age of 55 years. Looking at the association between severe menopausal symptoms and cognitive impairment, researchers found that women with severe symptoms were more likely to have cognitive impairment.

Conversely, they found that the women who had a favorable CVD risk factor status (physically active, lower BMI, healthier) and were ever users of estrogen were less likely to have cognitive impairment.

Clearly, for estrogen therapy, we need randomized clinical trials of the presence or absence of vasomotor symptoms and cognitive and CVD outcomes. Such analyses are ongoing, and new randomized trials focused specifically on women in early menopause would be very beneficial.

At the present time, it’s important that we not alarm women about the associations seen in some of these studies because often they are not independent associations; they aren’t independent of other risk factors that are commonly linked to hot flashes and night sweats. There are many other complexities in the relationship between hot flashes and cognitive impairment.

We need to appreciate that women who have moderate to severe hot flashes (especially when associated with disrupted sleep) do have impaired quality of life. It’s important to treat these symptoms, especially in early menopause, and very effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatments are available.

For women with symptoms that persist into later menopause or who have new onset of symptoms in later menopause, it’s important to prioritize cardiovascular health. For example, be more vigilant about behavioral lifestyle counseling to lower risk, and be even more aggressive in treating dyslipidemia and diabetes.

JoAnn E. Manson, Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School; Chief, Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; and Past President, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I’d like to talk about a recent report in the journal Menopause linking menopausal symptoms to increased risk for cognitive impairment. I’d also like to discuss some of the recent studies that have addressed whether hot flashes are linked to increased risk for heart disease and other forms of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Given that 75%-80% of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women have hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms, it’s undoubtedly a more complex relationship between hot flashes and these outcomes than a simple one-size-fits-all, yes-or-no question.

Increasing evidence shows that several additional factors are important, including the age at which the symptoms are occurring, the time since menopause, the severity of the symptoms, whether they co-occur with night sweats and sleep disruption, and the cardiovascular status of the woman.

Several studies suggest that women who have more severe hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms are more likely to have prevalent cardiovascular risk factors — hypertension, dyslipidemia, high body mass index, endothelial dysfunction — as measured by flow-mediated vasodilation and other measures.

It is quite plausible that hot flashes could be a marker for increased risk for cognitive impairment. But the question remains, are hot flashes associated with cognitive impairment independent of these other risk factors? It appears that the associations between hot flashes, vasomotor symptoms, and CVD, and other adverse outcomes, may be more likely when hot flashes persist after age 60 or are newly occurring in later menopause. In the Women’s Health Initiative observational study, the presence of hot flashes and vasomotor symptoms in early menopause was not linked to any increased risk for heart attack, stroke, total CVD, or all-cause mortality.

However, the onset of these symptoms, especially new onset of these symptoms after age 60 or in later menopause, was in fact linked to increased risk for CVD and all-cause mortality. With respect to cognitive impairment, if a woman is having hot flashes and night sweats with regular sleep disruption, performance on cognitive testing would not be as favorable as it would be in the absence of these symptoms.

This brings us to the new study in Menopause that included approximately 1300 Latino women in nine Latin American countries, with an average age of 55 years. Looking at the association between severe menopausal symptoms and cognitive impairment, researchers found that women with severe symptoms were more likely to have cognitive impairment.

Conversely, they found that the women who had a favorable CVD risk factor status (physically active, lower BMI, healthier) and were ever users of estrogen were less likely to have cognitive impairment.

Clearly, for estrogen therapy, we need randomized clinical trials of the presence or absence of vasomotor symptoms and cognitive and CVD outcomes. Such analyses are ongoing, and new randomized trials focused specifically on women in early menopause would be very beneficial.

At the present time, it’s important that we not alarm women about the associations seen in some of these studies because often they are not independent associations; they aren’t independent of other risk factors that are commonly linked to hot flashes and night sweats. There are many other complexities in the relationship between hot flashes and cognitive impairment.

We need to appreciate that women who have moderate to severe hot flashes (especially when associated with disrupted sleep) do have impaired quality of life. It’s important to treat these symptoms, especially in early menopause, and very effective hormonal and nonhormonal treatments are available.

For women with symptoms that persist into later menopause or who have new onset of symptoms in later menopause, it’s important to prioritize cardiovascular health. For example, be more vigilant about behavioral lifestyle counseling to lower risk, and be even more aggressive in treating dyslipidemia and diabetes.

JoAnn E. Manson, Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School; Chief, Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; and Past President, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Reform School’ for Pharmacy Benefit Managers: How Might Legislation Help Patients?

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

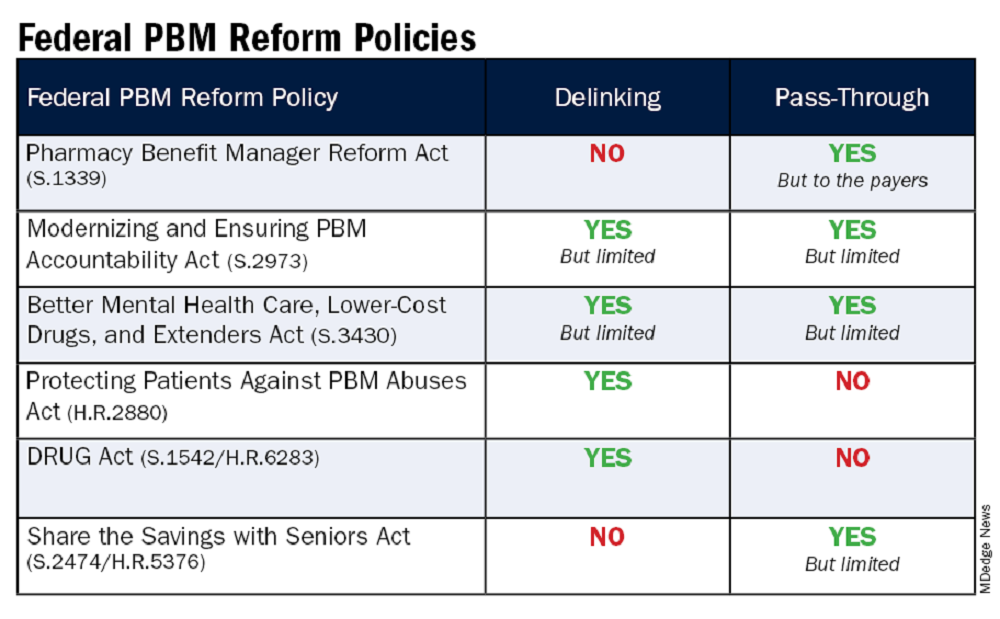

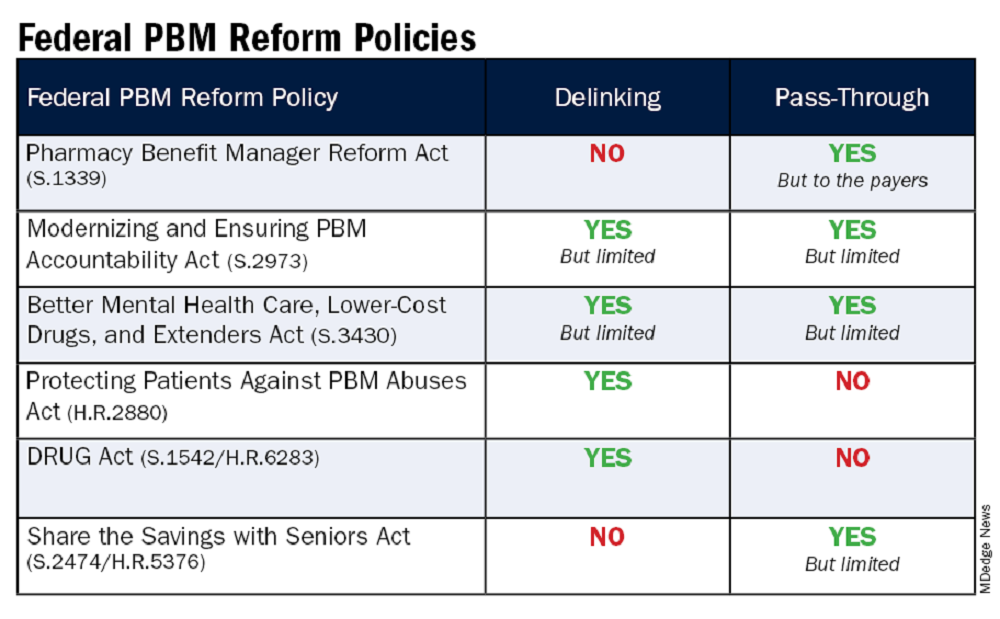

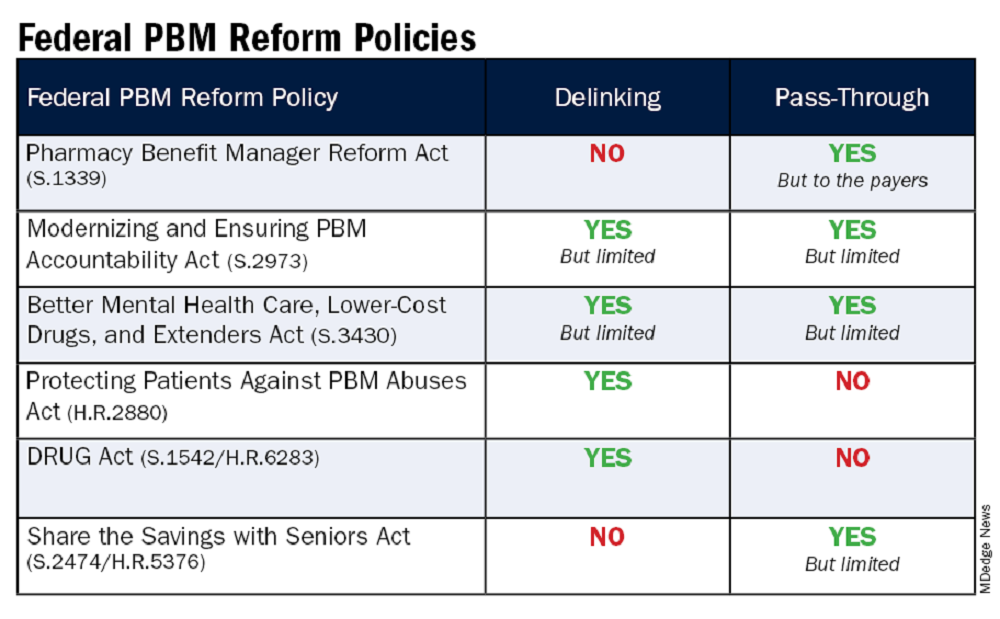

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at [email protected].

Stones, Bones, Groans, and Moans: Could This Be Primary Hyperparathyroidism?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams.

Paul, we’re going to talk about our primary hyperparathyroidism podcast with Dr. Lindsay Kuo. It’s a topic that I feel much more clear on now.

Now, Paul, in primary care, you see a lot of calcium that is just slightly high. Can we just blame that on thiazide diuretics?

Paul N. Williams, MD: It’s a place to start. As you’re starting to think about the possible etiologies, primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy are the two that roll right off the tongue, but it is worth going back to the patient’s medication list and making sure you’re not missing something.

Thiazides famously cause hypercalcemia, but in some of the reading I did for this episode, they may just uncover it a little bit early. Patients who are on thiazides who become hypercalcemic seem to go on to develop primary hyperthyroidism anyway. So I don’t think you can solely blame the thiazide.

Another medication that can be causative is lithium. So a good place to look first after you’ve repeated the labs and confirmed hypercalcemia is the patient’s medication list.

Dr. Watto: We’ve talked before about the basic workup for hypercalcemia, and determining whether it’s PTH dependent or PTH independent. On the podcast, we talk more about the full workup, but I wanted to talk about the classic symptoms. Our expert made the point that we don’t see them as much anymore, although we do see kidney stones. People used to present very late in the disease because they weren’t having labs done routinely.

The classic symptoms include osteoporosis and bone tumors. People can get nephrocalcinosis and kidney stones. I hadn’t really thought of it this way because we’re used to diagnosing it early now. Do you feel the same?

Dr. Williams: As labs have started routinely reporting calcium levels, this is more and more often how it’s picked up. The other aspect is that as we are screening for and finding osteoporosis, part of the workup almost always involves getting a parathyroid hormone and a calcium level. We’re seeing these lab abnormalities before we’re seeing symptoms, which is good.

But it also makes things more diagnostically thorny.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Lindsay Kuo made the point that when she sees patients before and after surgery, she’s aware of these nonclassic symptoms — the stones, bones, groans, and the psychiatric overtones that can be anything from fatigue or irritability to dysphoria.

Some people have a generalized weakness that’s very nonspecific. Dr. Kuo said that sometimes these symptoms will disappear after surgery. The patients may just have gotten used to them, or they thought these symptoms were caused by something else, but after surgery they went away.

There are these nonclassic symptoms that are harder to pin down. I was surprised by that.

Dr. Williams: She mentioned polydipsia and polyuria, which have been reported in other studies. It seems like it can be anything. You have to take a good history, but none of those things in and of themselves is an indication for operating unless the patient has the classic renal or bone manifestations.

Dr. Watto: The other thing we talked about is a normal calcium level in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, or the finding of a PTH level in the normal range but with a high calcium level that is inappropriate. Can you talk a little bit about those two situations?

Dr. Williams: They’re hard to say but kind of easy to manage because you treat them the same way as someone who has elevated calcium and PTH levels.

The normocalcemic patient is something we might stumble across with osteoporosis screening. Initially the calcium level is elevated, so you repeat it and it’s normal but with an elevated PTH level. You’re like, shoot. Now what?

It turns out that most endocrine surgeons say that the indications for surgery for the classic form of primary hyperparathyroidism apply to these patients as well, and it probably helps with the bone outcomes, which is one of the things they follow most closely. If you have hypercalcemia, you should have a suppressed PTH level, the so-called normohormonal hyperparathyroidism, which is not normal at all. So even if the PTH is in the normal range, it’s still relatively elevated compared with what it should be. That situation is treated in the same way as the classic elevated PTH and elevated calcium levels.

Dr. Watto: If the calcium is abnormal and the PTH is not quite what you’d expect it to be, you can always ask your friendly neighborhood endocrinologist to help you figure out whether the patient really has one of these conditions. You have to make sure that they don’t have a simple secondary cause like a low vitamin D level. In that case, you fix the vitamin D and then recheck the numbers to see if they’ve normalized. But I have found a bunch of these edge cases in which it has been helpful to confer with an endocrinologist, especially before you send someone to a surgeon to take out their parathyroid gland.

This was a really fantastic conversation. If you want to hear the full podcast episode, click here.

Dr. Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders, and has received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams.

Paul, we’re going to talk about our primary hyperparathyroidism podcast with Dr. Lindsay Kuo. It’s a topic that I feel much more clear on now.

Now, Paul, in primary care, you see a lot of calcium that is just slightly high. Can we just blame that on thiazide diuretics?

Paul N. Williams, MD: It’s a place to start. As you’re starting to think about the possible etiologies, primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy are the two that roll right off the tongue, but it is worth going back to the patient’s medication list and making sure you’re not missing something.

Thiazides famously cause hypercalcemia, but in some of the reading I did for this episode, they may just uncover it a little bit early. Patients who are on thiazides who become hypercalcemic seem to go on to develop primary hyperthyroidism anyway. So I don’t think you can solely blame the thiazide.

Another medication that can be causative is lithium. So a good place to look first after you’ve repeated the labs and confirmed hypercalcemia is the patient’s medication list.

Dr. Watto: We’ve talked before about the basic workup for hypercalcemia, and determining whether it’s PTH dependent or PTH independent. On the podcast, we talk more about the full workup, but I wanted to talk about the classic symptoms. Our expert made the point that we don’t see them as much anymore, although we do see kidney stones. People used to present very late in the disease because they weren’t having labs done routinely.

The classic symptoms include osteoporosis and bone tumors. People can get nephrocalcinosis and kidney stones. I hadn’t really thought of it this way because we’re used to diagnosing it early now. Do you feel the same?

Dr. Williams: As labs have started routinely reporting calcium levels, this is more and more often how it’s picked up. The other aspect is that as we are screening for and finding osteoporosis, part of the workup almost always involves getting a parathyroid hormone and a calcium level. We’re seeing these lab abnormalities before we’re seeing symptoms, which is good.

But it also makes things more diagnostically thorny.

Dr. Watto: Dr. Lindsay Kuo made the point that when she sees patients before and after surgery, she’s aware of these nonclassic symptoms — the stones, bones, groans, and the psychiatric overtones that can be anything from fatigue or irritability to dysphoria.

Some people have a generalized weakness that’s very nonspecific. Dr. Kuo said that sometimes these symptoms will disappear after surgery. The patients may just have gotten used to them, or they thought these symptoms were caused by something else, but after surgery they went away.

There are these nonclassic symptoms that are harder to pin down. I was surprised by that.

Dr. Williams: She mentioned polydipsia and polyuria, which have been reported in other studies. It seems like it can be anything. You have to take a good history, but none of those things in and of themselves is an indication for operating unless the patient has the classic renal or bone manifestations.

Dr. Watto: The other thing we talked about is a normal calcium level in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism, or the finding of a PTH level in the normal range but with a high calcium level that is inappropriate. Can you talk a little bit about those two situations?

Dr. Williams: They’re hard to say but kind of easy to manage because you treat them the same way as someone who has elevated calcium and PTH levels.

The normocalcemic patient is something we might stumble across with osteoporosis screening. Initially the calcium level is elevated, so you repeat it and it’s normal but with an elevated PTH level. You’re like, shoot. Now what?

It turns out that most endocrine surgeons say that the indications for surgery for the classic form of primary hyperparathyroidism apply to these patients as well, and it probably helps with the bone outcomes, which is one of the things they follow most closely. If you have hypercalcemia, you should have a suppressed PTH level, the so-called normohormonal hyperparathyroidism, which is not normal at all. So even if the PTH is in the normal range, it’s still relatively elevated compared with what it should be. That situation is treated in the same way as the classic elevated PTH and elevated calcium levels.

Dr. Watto: If the calcium is abnormal and the PTH is not quite what you’d expect it to be, you can always ask your friendly neighborhood endocrinologist to help you figure out whether the patient really has one of these conditions. You have to make sure that they don’t have a simple secondary cause like a low vitamin D level. In that case, you fix the vitamin D and then recheck the numbers to see if they’ve normalized. But I have found a bunch of these edge cases in which it has been helpful to confer with an endocrinologist, especially before you send someone to a surgeon to take out their parathyroid gland.

This was a really fantastic conversation. If you want to hear the full podcast episode, click here.

Dr. Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for The Curbsiders, and has received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from The Curbsiders.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr. Paul Nelson Williams.

Paul, we’re going to talk about our primary hyperparathyroidism podcast with Dr. Lindsay Kuo. It’s a topic that I feel much more clear on now.

Now, Paul, in primary care, you see a lot of calcium that is just slightly high. Can we just blame that on thiazide diuretics?