User login

An Agreeable Girl With a Stubborn Rash

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “a”). Impetigo is almost always secondary to another condition, such as contact or irritant dermatitis, eczema, or dry skin.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection usually caused by a combination of strep and staph organisms. It requires a break in the skin to provide a point of entry for the organisms. In young children, scratching and picking at eczema, along with lip licking, exacerbate the barrier-breaching process.

The organisms that cause impetigo are typically benign, but this was not always the case. Prior to WWI, certain strains of strep were capable of triggering an immune response that resulted in kidney damage. These “nephritogenic” strains of the Streptococcus family caused acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Bright disease), which, at that time, killed thousands each year. Fortunately, these strains are rare now.

In the pre-antibiotic days, when the average person bathed once a week, impetigo was highly contagious and serious enough that whole households were quarantined because of it.

Today, impetigo, once diagnosed, is relatively simple to manage. Mild cases can be treated with application of mupirocin ointment or cream three times a day. In this particular case, a 10-day course of an oral antibiotic (trimethoprim sulfa) was added, and the rash rapidly cleared.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “a”). Impetigo is almost always secondary to another condition, such as contact or irritant dermatitis, eczema, or dry skin.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection usually caused by a combination of strep and staph organisms. It requires a break in the skin to provide a point of entry for the organisms. In young children, scratching and picking at eczema, along with lip licking, exacerbate the barrier-breaching process.

The organisms that cause impetigo are typically benign, but this was not always the case. Prior to WWI, certain strains of strep were capable of triggering an immune response that resulted in kidney damage. These “nephritogenic” strains of the Streptococcus family caused acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Bright disease), which, at that time, killed thousands each year. Fortunately, these strains are rare now.

In the pre-antibiotic days, when the average person bathed once a week, impetigo was highly contagious and serious enough that whole households were quarantined because of it.

Today, impetigo, once diagnosed, is relatively simple to manage. Mild cases can be treated with application of mupirocin ointment or cream three times a day. In this particular case, a 10-day course of an oral antibiotic (trimethoprim sulfa) was added, and the rash rapidly cleared.

ANSWER

The correct answer is impetigo (choice “a”). Impetigo is almost always secondary to another condition, such as contact or irritant dermatitis, eczema, or dry skin.

DISCUSSION

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection usually caused by a combination of strep and staph organisms. It requires a break in the skin to provide a point of entry for the organisms. In young children, scratching and picking at eczema, along with lip licking, exacerbate the barrier-breaching process.

The organisms that cause impetigo are typically benign, but this was not always the case. Prior to WWI, certain strains of strep were capable of triggering an immune response that resulted in kidney damage. These “nephritogenic” strains of the Streptococcus family caused acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Bright disease), which, at that time, killed thousands each year. Fortunately, these strains are rare now.

In the pre-antibiotic days, when the average person bathed once a week, impetigo was highly contagious and serious enough that whole households were quarantined because of it.

Today, impetigo, once diagnosed, is relatively simple to manage. Mild cases can be treated with application of mupirocin ointment or cream three times a day. In this particular case, a 10-day course of an oral antibiotic (trimethoprim sulfa) was added, and the rash rapidly cleared.

Distraught parents of a 5-year-old girl are at their wit’s end dealing with their daughter’s perioral rash, which first appeared several months ago. Although they’ve consulted three different primary care providers, who rendered several diagnoses and numerous treatments, the rash continues to worsen. The parents worry about scarring, but they are more concerned that the rash may never clear at all.

Her treatments have included oral erythromycin, oral amoxicillin, topical anti-yeast cream, and various petroleum-based and hydrocortisone-containing OTC lip balms. In a moment of desperation, the parents even applied their son’s psoriasis cream (betamethasone) and diaper cream. These, too, had no effect.

Contactants had been considered as a possible source, causing the family to switch toothpaste brands and toothbrushes and eliminate mouthwash use—again, with no change.

Family history includes an atopic brother (eczema, asthma, seasonal allergies). The parents confirm that the patient has very sensitive skin and can’t tolerate many soaps and moisturizers. Before the rash manifested, they noticed she had a tendency to compulsively lick her lips.

The patient is quite fair-skinned, with red hair and blue eyes. The rash, which covers her entire perioral area, is impressively florid, red, and scaly. Focally, several areas of honey-colored crusts can be seen. The vermillion surfaces of the lips are unaffected except for slight focal fissuring. No nodes can be felt in the head or neck. The patient is in good spirits despite all this, and certainly not in any distress.

Sporotrichoid Fluctuant Nodules

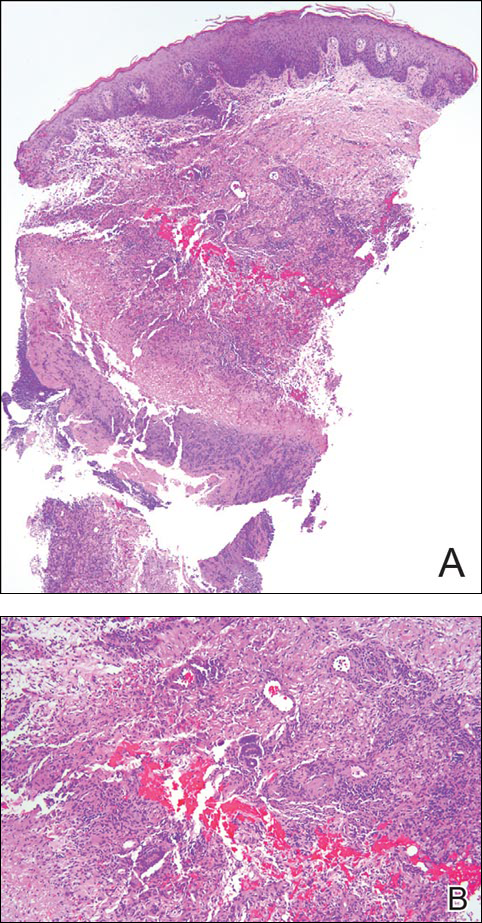

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

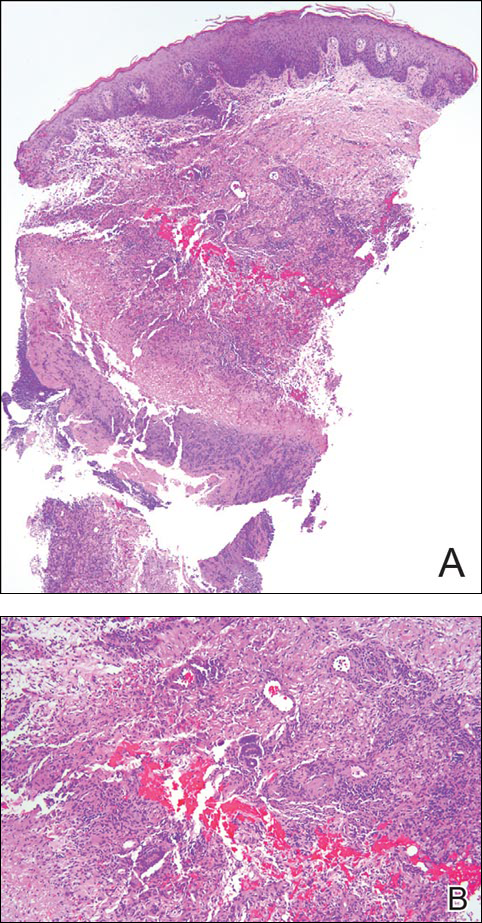

Punch biopsy specimens demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the dermis and subcutis (Figure). Special staining for microorganisms was negative. Tissue culture grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI). The patient began treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Tissue susceptibilities later showed resistance to rifabutin and sensitivity to clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and clofazimine. She subsequently was switched to azithromycin, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin with good response.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is a slow-growing, nonchromogenic, atypical mycobacteria. Although ubiquitous, it tends to only cause serious infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Transmission usually is through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.1 Skin infections with MAI are uncommon and usually are secondary to seeding from disseminated infection or from direct inoculation.2

The clinical presentations of primary cutaneous MAI are myriad, including an isolated red nodule, multiple ulcers, abscesses, draining sinuses, facial nodules, granulomatous plaques, and panniculitis.2,3 Of 3 reported cases of primary cutaneous MAI in the form of sporotrichoid lesions, 2 involved patients with AIDS2 and 1 involved a cardiac transplant recipient.4

Cutaneous MAI is typically diagnosed with skin biopsy and tissue culture. Tissue culture is critical for determining the specific mycobacterial species and antibiotic susceptibilities. Polymerase chain reaction has been utilized to rapidly diagnose cutaneous MAI infection from an acid-fast bacilli–positive tissue sample in which the tissue culture was negative.5

Recommended treatment protocols for MAI involve multidrug regimens because of the intrinsic resistance of MAI and the concern for development of resistance with monotherapy.2 No definitive guidelines exist for treatment of primary cutaneous MAI infections. However, regimens for the treatment of pulmonary infection that also have been successfully utilized for cutaneous infection include a macrolide, ethambutol, and a rifamycin.6 Clinicians should be aware of MAI as a cause of primary cutaneous infections presenting as lymphocutaneous suppurative nodules and ulcerations.

- Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:657-668.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Wood C, Nickoloff BJ, Todes-Taylor NR. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

- Carlos CA, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

Punch biopsy specimens demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the dermis and subcutis (Figure). Special staining for microorganisms was negative. Tissue culture grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI). The patient began treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Tissue susceptibilities later showed resistance to rifabutin and sensitivity to clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and clofazimine. She subsequently was switched to azithromycin, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin with good response.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is a slow-growing, nonchromogenic, atypical mycobacteria. Although ubiquitous, it tends to only cause serious infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Transmission usually is through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.1 Skin infections with MAI are uncommon and usually are secondary to seeding from disseminated infection or from direct inoculation.2

The clinical presentations of primary cutaneous MAI are myriad, including an isolated red nodule, multiple ulcers, abscesses, draining sinuses, facial nodules, granulomatous plaques, and panniculitis.2,3 Of 3 reported cases of primary cutaneous MAI in the form of sporotrichoid lesions, 2 involved patients with AIDS2 and 1 involved a cardiac transplant recipient.4

Cutaneous MAI is typically diagnosed with skin biopsy and tissue culture. Tissue culture is critical for determining the specific mycobacterial species and antibiotic susceptibilities. Polymerase chain reaction has been utilized to rapidly diagnose cutaneous MAI infection from an acid-fast bacilli–positive tissue sample in which the tissue culture was negative.5

Recommended treatment protocols for MAI involve multidrug regimens because of the intrinsic resistance of MAI and the concern for development of resistance with monotherapy.2 No definitive guidelines exist for treatment of primary cutaneous MAI infections. However, regimens for the treatment of pulmonary infection that also have been successfully utilized for cutaneous infection include a macrolide, ethambutol, and a rifamycin.6 Clinicians should be aware of MAI as a cause of primary cutaneous infections presenting as lymphocutaneous suppurative nodules and ulcerations.

The Diagnosis: Atypical Mycobacterial Infection

Punch biopsy specimens demonstrated necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in the dermis and subcutis (Figure). Special staining for microorganisms was negative. Tissue culture grew Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare (MAI). The patient began treatment with azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin. Tissue susceptibilities later showed resistance to rifabutin and sensitivity to clarithromycin, moxifloxacin, and clofazimine. She subsequently was switched to azithromycin, clofazimine, and moxifloxacin with good response.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is a slow-growing, nonchromogenic, atypical mycobacteria. Although ubiquitous, it tends to only cause serious infection in the setting of immunosuppression. Transmission usually is through the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract.1 Skin infections with MAI are uncommon and usually are secondary to seeding from disseminated infection or from direct inoculation.2

The clinical presentations of primary cutaneous MAI are myriad, including an isolated red nodule, multiple ulcers, abscesses, draining sinuses, facial nodules, granulomatous plaques, and panniculitis.2,3 Of 3 reported cases of primary cutaneous MAI in the form of sporotrichoid lesions, 2 involved patients with AIDS2 and 1 involved a cardiac transplant recipient.4

Cutaneous MAI is typically diagnosed with skin biopsy and tissue culture. Tissue culture is critical for determining the specific mycobacterial species and antibiotic susceptibilities. Polymerase chain reaction has been utilized to rapidly diagnose cutaneous MAI infection from an acid-fast bacilli–positive tissue sample in which the tissue culture was negative.5

Recommended treatment protocols for MAI involve multidrug regimens because of the intrinsic resistance of MAI and the concern for development of resistance with monotherapy.2 No definitive guidelines exist for treatment of primary cutaneous MAI infections. However, regimens for the treatment of pulmonary infection that also have been successfully utilized for cutaneous infection include a macrolide, ethambutol, and a rifamycin.6 Clinicians should be aware of MAI as a cause of primary cutaneous infections presenting as lymphocutaneous suppurative nodules and ulcerations.

- Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:657-668.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Wood C, Nickoloff BJ, Todes-Taylor NR. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

- Carlos CA, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

- Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:657-668.

- Kayal JD, McCall CO. Sporotrichoid cutaneous Mycobacterium avium complex infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S249-S250.

- Kullavanijaya P, Sirimachan S, Surarak S. Primary cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex resembling lupus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:264-266.

- Wood C, Nickoloff BJ, Todes-Taylor NR. Pseudotumor resulting from atypical mycobacterial infection: a “histoid” variety of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:524-527.

- Carlos CA, Tang YW, Adler DJ, et al. Mycobacterial infection identified with broad-range PCR amplification and suspension array identification. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:795-797.

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliot BA, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416.

A woman in her 50s presented with low-grade subjective intermittent fevers and painful draining ulcerations on the legs of 7 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for polymyositis and interstitial lung disease managed with prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil. While living in Taiwan, she developed lower extremity abscesses and persistent fevers. The patient denied any skin injuries or exposure to animals or brackish water. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, and she was treated with multiple antibiotics alone and in combination without improvement, including amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, levofloxacin, azithromycin, moxifloxacin, rifampin, rifabutin, and ethambutol. She returned to the United States for evaluation. Physical examination revealed ulcerations with purulent drainage and interconnected sinus tracts with rare fluctuant nodules along the right leg. A single similar lesion was present on the right chest wall. There was no clinical evidence of disseminated disease.

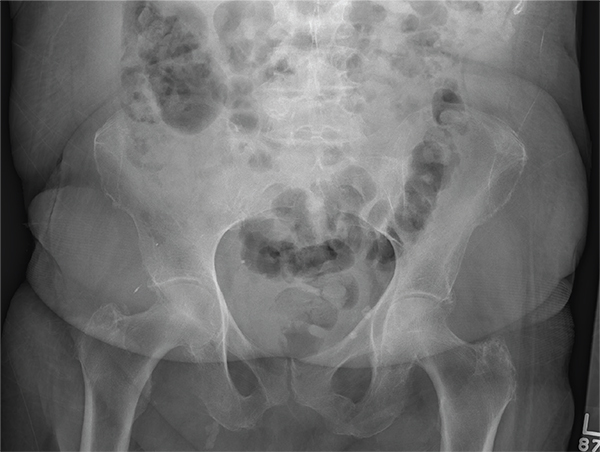

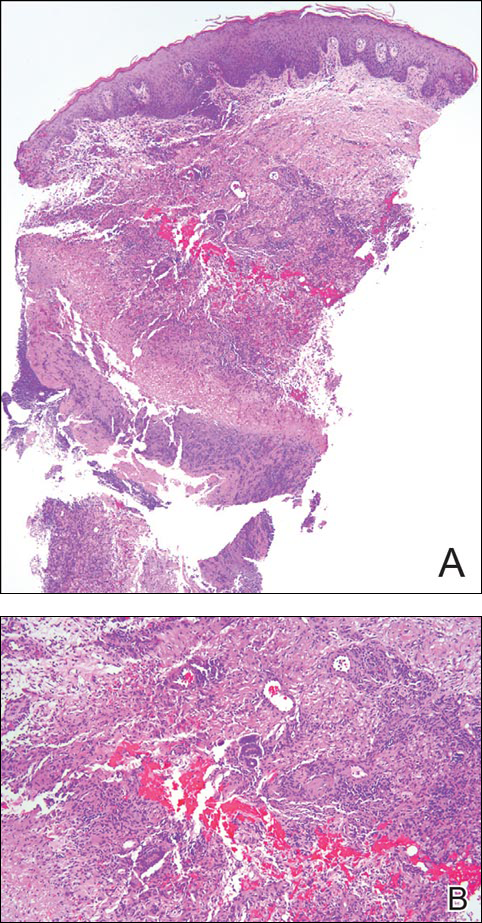

An Alarming Slip of the Hip

After a fall, an 80-year-old woman is brought to the emergency department for evaluation of hip pain. She was getting out of bed when she slipped, fell, and landed on her right hip; bearing weight now is painful. She denies hitting her head. The patient’s vital signs are normal. Her medical history is significant for hypertension and diabetes. Inspection of the hip reveals no obvious deformity or shortening. The right lateral aspect of the hip exhibits mild swelling and decreased range of motion secondary to the pain. You order a pelvic radiograph, which is shown. What is your impression?

1-800-Zap-My-Zits

ANSWERThe correct diagnosis is discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE; choice “c”). For those unfamiliar with DLE, it is often mistaken for the other items listed. Biopsy can distinguish among them.

Fungal infection (dermatophytosis; choice “a”) of the face is unusual and would have responded in some way to the antifungal cream. Likewise, the use of steroid creams would have markedly worsened a fungal infection.

Although this could have been psoriasis (choice “b”), it’s rare for that condition to be confined to the face. It almost always appears elsewhere—the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or nails.

Dermatomyositis (choice “d”), an autoimmune condition, can certainly present with a bimalar rash. However, it is usually accompanied by additional symptoms, such as progressive weakness and muscle pain.

DISCUSSION

DLE can represent a stand-alone diagnosis, or it can be a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). When present in this bimalar form, the lesions are often mistaken for the “butterfly rash” commonly seen in SLE.

This patient was thoroughly tested for SLE, and no evidence of it was found. Biopsy did, however, show changes consistent with DLE (interface dermatitis with increased mucin formation, among others).

The treatment for DLE is rather simple: It consists of sun protection and oral hydroxychloroquine. This helps reduce inflammation, although the patient will still have residual scarring.

ANSWERThe correct diagnosis is discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE; choice “c”). For those unfamiliar with DLE, it is often mistaken for the other items listed. Biopsy can distinguish among them.

Fungal infection (dermatophytosis; choice “a”) of the face is unusual and would have responded in some way to the antifungal cream. Likewise, the use of steroid creams would have markedly worsened a fungal infection.

Although this could have been psoriasis (choice “b”), it’s rare for that condition to be confined to the face. It almost always appears elsewhere—the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or nails.

Dermatomyositis (choice “d”), an autoimmune condition, can certainly present with a bimalar rash. However, it is usually accompanied by additional symptoms, such as progressive weakness and muscle pain.

DISCUSSION

DLE can represent a stand-alone diagnosis, or it can be a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). When present in this bimalar form, the lesions are often mistaken for the “butterfly rash” commonly seen in SLE.

This patient was thoroughly tested for SLE, and no evidence of it was found. Biopsy did, however, show changes consistent with DLE (interface dermatitis with increased mucin formation, among others).

The treatment for DLE is rather simple: It consists of sun protection and oral hydroxychloroquine. This helps reduce inflammation, although the patient will still have residual scarring.

ANSWERThe correct diagnosis is discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE; choice “c”). For those unfamiliar with DLE, it is often mistaken for the other items listed. Biopsy can distinguish among them.

Fungal infection (dermatophytosis; choice “a”) of the face is unusual and would have responded in some way to the antifungal cream. Likewise, the use of steroid creams would have markedly worsened a fungal infection.

Although this could have been psoriasis (choice “b”), it’s rare for that condition to be confined to the face. It almost always appears elsewhere—the scalp, elbows, knees, and/or nails.

Dermatomyositis (choice “d”), an autoimmune condition, can certainly present with a bimalar rash. However, it is usually accompanied by additional symptoms, such as progressive weakness and muscle pain.

DISCUSSION

DLE can represent a stand-alone diagnosis, or it can be a manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). When present in this bimalar form, the lesions are often mistaken for the “butterfly rash” commonly seen in SLE.

This patient was thoroughly tested for SLE, and no evidence of it was found. Biopsy did, however, show changes consistent with DLE (interface dermatitis with increased mucin formation, among others).

The treatment for DLE is rather simple: It consists of sun protection and oral hydroxychloroquine. This helps reduce inflammation, although the patient will still have residual scarring.

A 52-year-old man is referred to dermatology by his primary care provider for evaluation of facial lesions that first appeared almost a year ago. The patient, who works as a welder, has noticed that sun exposure tends to exacerbate the problem. He denies joint pain, fever, and malaise. He self-diagnosed the condition as acne and ordered a product from a TV ad, but this cream only made things worse. The asymptomatic lesions persist, despite application of a number of prescription products (2.5% hydrocortisone cream, adapalene gel, and antifungal creams, including tolnaftate and clotrimazole). The eruption—comprised of discrete, round, scaly lesions—covers a good portion of the bimalar areas of his face. The lesions are purplish red, and on closer inspection, you observe patulous follicular orifices. Some of the older lesions have focal atrophy. The rest of the examination is unremarkable.

An Exhausting Case of “Smoker’s Cough”

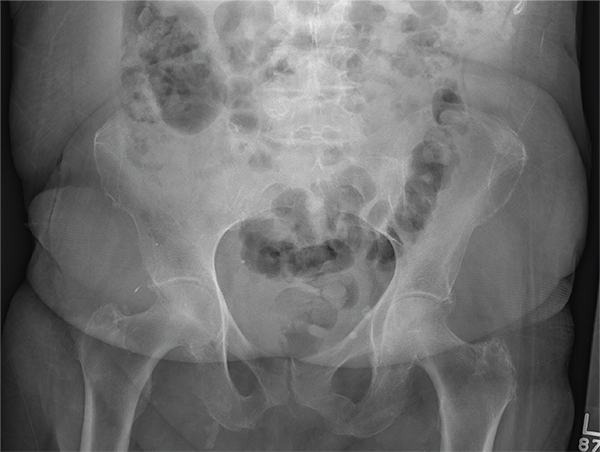

ANSWER

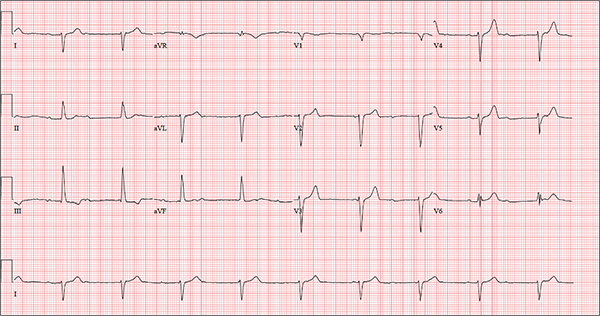

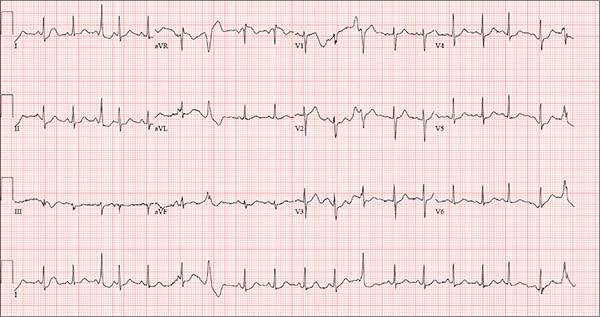

The correct interpretation includes sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional rhythm, a rightward axis, and evidence of an anterior myocardial infarction (MI).

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the regular rate and rhythm of the P waves.

Complete heart block is identified by the atrioventricular (AV) dissociation (QRS independent of the P wave), while the normal QRS duration—despite AV dissociation—confirms the existence of a junctional rhythm.

A positive R-wave axis slightly above the upper limit of normal, as seen with this patient, constitutes a rightward axis.

Finally, the posteriorly directed forces in the anterior precordial leads with poor R-wave progression denote an anterior MI.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional rhythm, a rightward axis, and evidence of an anterior myocardial infarction (MI).

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the regular rate and rhythm of the P waves.

Complete heart block is identified by the atrioventricular (AV) dissociation (QRS independent of the P wave), while the normal QRS duration—despite AV dissociation—confirms the existence of a junctional rhythm.

A positive R-wave axis slightly above the upper limit of normal, as seen with this patient, constitutes a rightward axis.

Finally, the posteriorly directed forces in the anterior precordial leads with poor R-wave progression denote an anterior MI.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes sinus rhythm with complete heart block and a junctional rhythm, a rightward axis, and evidence of an anterior myocardial infarction (MI).

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the regular rate and rhythm of the P waves.

Complete heart block is identified by the atrioventricular (AV) dissociation (QRS independent of the P wave), while the normal QRS duration—despite AV dissociation—confirms the existence of a junctional rhythm.

A positive R-wave axis slightly above the upper limit of normal, as seen with this patient, constitutes a rightward axis.

Finally, the posteriorly directed forces in the anterior precordial leads with poor R-wave progression denote an anterior MI.

One week ago, a 67-year-old African-American woman with a history of diabetes, hypertension, and smoking developed a nonproductive cough and chest discomfort. Over the past 24 hours, her symptoms have progressed, with increasing fatigue. She has delayed seeking care to spend time with visiting family, but this morning she calls for an appointment. At presentation, she describes her chest discomfort as a “vague, dull ache.” She denies sharp chest pain, radiation, syncope, near-syncope, and palpitations. She says her cough has resolved, aside from her usual early-morning “smoker’s cough.” However, she still experiences fatigue with exertion and must stop to rest after walking up one flight of stairs or about half a block on level ground. When asked about gardening, her favorite hobby, she tells you she stopped last week because she “didn’t have the energy” for it. Her medical history is remarkable for type 2 diabetes (for the past 10 years) and hypertension, for which she has been treated her entire adult life. She also has osteoarthritis. In the 20 years she has been in your patient panel, she has closely monitored her health and been vigilant about taking her medications. Her surgical history is remarkable for hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, and bilateral bunion resections. The patient retired two years ago after a 20-year career as a tax attorney. Her husband died of a myocardial infarction at age 56. She has two adult children, who also have hypertension. She has a 50–pack-year history of tobacco use and smokes up to one full pack of cigarettes per day. She denies alcohol and illicit drug use, aside from the occasional “nip” of brandy and infrequent marijuana use. Her medication list includes metformin, glyburide, hydrochlorothiazide, and lisinopril. She is allergic to sulfa. The review of systems is remarkable for hearing loss, diabetic neuropathy in both feet, and chronic loose stools. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 148/88 mm Hg—higher than measurements from her past three visits. Her pulse is 60 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.8°F. On physical exam, her weight is 201 lb and her height is 68 in; her weight has remained stable over the past two years. The HEENT exam findings include corrective lenses, bilateral hearing aids, and extensive dental work (including veneers). The neck is supple, without thyromegaly or jugular venous distention. The lungs are clear in all fields, apart from occasional crackles in both bases that clear with coughing. Her cardiac exam reveals a regular rate with no extra heart sounds or rubs, but a soft, early diastolic murmur at the left lower sternal border. The abdomen is soft and nontender with well-healed surgical scars and no palpable masses. Osteoarthritis is present in both hands, and her left hip has decreased range of motion, compared to her right. Peripheral pulses are strong bilaterally, and her neurologic exam is intact. You draw laboratory specimens and order a chest x-ray and ECG, which reveals a ventricular rate of 56 beats/min; PR interval, unmeasurable; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 400/386 ms; P axis, 36°; R axis, 120°; and T axis, 7°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Patch of Hair Loss on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Temporal Triangular Alopecia

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), also known as congenital triangular alopecia, was first described in the early 1900s.1 It presents clinically as a triangular-shaped area of nonscarring alopecia either unilaterally or bilaterally. Limited clinical data suggest that most unilateral cases are on the left frontotemporal region of the scalp. In bilateral cases, there may be asymmetry in size of the area involved.2 Dermatoscopically, TTA is characterized by decreased terminal hair follicle density as well as the presence of vellus hairs with an absence of inflammation.3 The majority of TTA is noted between birth and 6 years of life with the areas staying stable thereafter. Large areas of TTA may suggest cerebello-trigeminal-dermal dysplasia (Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome), a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by rhombencephalosynapsis, trigeminal anesthesia, and parietooccipital alopecia (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 601853).4 Although TTA is largely idiopathic, it has been suggested that the trait may be paradominant, whereby a postzygotic loss of the wild-type allele in a heterozygotic state causes triangular alopecia and reflects hamartomatous mosaicism.5 It also is an important mimicker of alopecia areata. Correct identification prevents unnecessary treatment to the areas of the scalp. Hair restoration surgery has been reported as a tool to treat this disorder.6

- Tosti A. Congenital triangular alopecia. report of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:991-993.

- Armstrong DK, Burrows D. Congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:394-396.

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Starace M, et al. Videodermoscopy: a useful tool for diagnosing congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:652-654.

- Assoly P, Happle R. A hairy paradox: congenital triangular alopecia with a central hair tuft. Dermatology. 2010;221:107-109.

- Happle R. Congenital triangular alopecia may be categorized as a paradominant trait. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:346-347.

- Wu WY, Otberg N, Kang H, et al. Successful treatment of temporal triangular alopecia by hair restoration surgery using follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1307-1310.

The Diagnosis: Temporal Triangular Alopecia

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), also known as congenital triangular alopecia, was first described in the early 1900s.1 It presents clinically as a triangular-shaped area of nonscarring alopecia either unilaterally or bilaterally. Limited clinical data suggest that most unilateral cases are on the left frontotemporal region of the scalp. In bilateral cases, there may be asymmetry in size of the area involved.2 Dermatoscopically, TTA is characterized by decreased terminal hair follicle density as well as the presence of vellus hairs with an absence of inflammation.3 The majority of TTA is noted between birth and 6 years of life with the areas staying stable thereafter. Large areas of TTA may suggest cerebello-trigeminal-dermal dysplasia (Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome), a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by rhombencephalosynapsis, trigeminal anesthesia, and parietooccipital alopecia (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 601853).4 Although TTA is largely idiopathic, it has been suggested that the trait may be paradominant, whereby a postzygotic loss of the wild-type allele in a heterozygotic state causes triangular alopecia and reflects hamartomatous mosaicism.5 It also is an important mimicker of alopecia areata. Correct identification prevents unnecessary treatment to the areas of the scalp. Hair restoration surgery has been reported as a tool to treat this disorder.6

The Diagnosis: Temporal Triangular Alopecia

Temporal triangular alopecia (TTA), also known as congenital triangular alopecia, was first described in the early 1900s.1 It presents clinically as a triangular-shaped area of nonscarring alopecia either unilaterally or bilaterally. Limited clinical data suggest that most unilateral cases are on the left frontotemporal region of the scalp. In bilateral cases, there may be asymmetry in size of the area involved.2 Dermatoscopically, TTA is characterized by decreased terminal hair follicle density as well as the presence of vellus hairs with an absence of inflammation.3 The majority of TTA is noted between birth and 6 years of life with the areas staying stable thereafter. Large areas of TTA may suggest cerebello-trigeminal-dermal dysplasia (Gomez-Lopez-Hernandez syndrome), a rare neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by rhombencephalosynapsis, trigeminal anesthesia, and parietooccipital alopecia (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 601853).4 Although TTA is largely idiopathic, it has been suggested that the trait may be paradominant, whereby a postzygotic loss of the wild-type allele in a heterozygotic state causes triangular alopecia and reflects hamartomatous mosaicism.5 It also is an important mimicker of alopecia areata. Correct identification prevents unnecessary treatment to the areas of the scalp. Hair restoration surgery has been reported as a tool to treat this disorder.6

- Tosti A. Congenital triangular alopecia. report of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:991-993.

- Armstrong DK, Burrows D. Congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:394-396.

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Starace M, et al. Videodermoscopy: a useful tool for diagnosing congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:652-654.

- Assoly P, Happle R. A hairy paradox: congenital triangular alopecia with a central hair tuft. Dermatology. 2010;221:107-109.

- Happle R. Congenital triangular alopecia may be categorized as a paradominant trait. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:346-347.

- Wu WY, Otberg N, Kang H, et al. Successful treatment of temporal triangular alopecia by hair restoration surgery using follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1307-1310.

- Tosti A. Congenital triangular alopecia. report of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:991-993.

- Armstrong DK, Burrows D. Congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:394-396.

- Iorizzo M, Pazzaglia M, Starace M, et al. Videodermoscopy: a useful tool for diagnosing congenital triangular alopecia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:652-654.

- Assoly P, Happle R. A hairy paradox: congenital triangular alopecia with a central hair tuft. Dermatology. 2010;221:107-109.

- Happle R. Congenital triangular alopecia may be categorized as a paradominant trait. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:346-347.

- Wu WY, Otberg N, Kang H, et al. Successful treatment of temporal triangular alopecia by hair restoration surgery using follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1307-1310.

An 11-year-old girl presented for evaluation of a patch of hair loss on the right parietal scalp that had been present and stable for 2.5 years. Physical examination revealed a unilateral area of hair loss that was triangular in shape on the right parietal/temporal region, measuring 2.1×2.2 cm. Dermatoscope examination showed vellus hairs throughout. A hair-pull test was negative and the patient confirmed that the area had never been completely smooth. There were no associated symptoms and no family history of autoimmune disease or hair loss. Prior to presentation, the patient underwent a trial of intralesional steroids and topical steroids to the area without effect.

Nonpainful Ulcerations on the Nose and Forehead

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

A 57-year-old man with a history of multiple cerebrovascular accidents was transferred from an outside hospital to our inpatient rheumatology service with nonpainful erosions of the forehead and nasal ala of 6 months’ duration. The patient reported that he initially developed a sore on the nose months prior to presentation with worsening sensations of itching and tingling on the forehead and nose. He also noted a headache and gradual loss of vision in the right eye. The patient was immunocompetent and denied arthralgia or any other skin lesions.

Hyperkeratotic Lesions in a Patient With Hepatitis C Virus

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

The Diagnosis: Necrolytic Acral Erythema

Histopathologic analysis of a biopsy specimen from the right leg revealed an erosion with parakeratosis containing neutrophils and marked spongiosis favoring the upper layer of the epidermis with focal individual necrotic keratinocytes. In addition, there was a lymphocytic and neutrophilic exocytosis with edema of the papillary dermal papillae, mild papillary dermal fibrosis, and a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils. Clinicopathologic correlation led to a diagnosis of necrolytic acral erythema (NAE).

The patient was prescribed clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% and oral zinc sulfate 220 mg twice daily but was initially noncompliant with the topical corticosteroid regimen. He did, however, initiate zinc supplementation, which was later increased to 220 mg 3 times daily. At 3-month follow-up, the lesions had nearly completely cleared (Figure) and the serum zinc level was within reference range at 81 μg/dL.

Necrolytic acral erythema is a rare dermatosis that was first described in 1996 by el Darouti and Abu el Ela1 in a series of 7 Egyptian patients. Since then, most of the cases have reported concomitant hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.2 Necrolytic acral erythema classically presents with symmetric, well-defined, hyperkeratotic plaques in an acral distribution, typically on the dorsal aspect of the feet.2,3 Lesions may involve the dorsal aspect of the toes and the lower legs, with less common involvement of the elbows, hands, and buttocks. Patients often report pruritus and/or burning.3

Abdallah et al4 proposed several stages of NAE development with erythematous papules with dusky eroded centers progressing to marginated, erythematous to violaceous, lichenified plaques. Over time, these lesions tend to thin with progressive hyperpigmentation.

Histologically, early findings of NAE include acanthosis with epidermal spongiosis and upper dermal perivascular dermatitis. Over time, lesions may exhibit psoriasiform hyperplasia with papillomatosis and parakeratosis, epidermal pallor, subcorneal pustules, vascular ectasia, papillary dermal inflammation, and necrotic keratinocytes. Minimal to moderate acanthosis with an inflammatory infiltrate may be observed later in disease progression.5

The differential diagnosis of NAE includes many benign inflammatory skin diseases. Given the acral/extensor distribution of hyperkeratotic lesions and psoriasiform pattern on histopathology, NAE initially may be misdiagnosed as psoriasis. Unlike psoriasis, however, NAE rarely involves palmoplantar skin or nails4 and may respond dramatically to treatment with zinc supplementation.6,7 Necrolytic acral erythema also may be confused with other necrolytic erythemas, including necrolytic migratory erythema, acrodermatitis enteropathica, and pellagra. A deficiency of biotin or essential fatty acids also may mimic NAE. Necrolytic acral erythema can be distinguished from these entities based on its characteristic appearance and distribution, along with comorbid HCV infection.2-4

Several reports of NAE have revealed an associated zinc deficiency.2,8 The underlying pathophysiology of zinc deficiency in NAE has not been elucidated but is thought to be related to HCV infection.2 Clinical improvement has been reported with zinc supplementation in patients with NAE at dosages of 220 mg twice daily, even in those with initial serum zinc levels within reference range.6,7 Our patient was observed to have a low serum zinc level that dramatically improved with oral supplementation.

The recognition of this uncommon entity is critical for dermatologists and dermatopathologists, as NAE has been proposed as an early cutaneous marker of HCV and may prompt the initial diagnosis of HCV.1-10 The severity of NAE has even been linked to HCV severity.1,8 Treatment of HCV has cleared NAE in several cases,4,10 implicating the virus in its pathogenesis. A proper workup for liver dysfunction and follow-up with an appropriate health care provider for HCV treatment is crucial. Our patient was encouraged to follow up with the hepatology department, as he had not been evaluated in several years.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

- el Darouti M, Abu el Ela M. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous marker of viral hepatitis C. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:252-256.

- Patel U, Loyd A, Patel R, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:15.

- Geria AN, Holcomb KZ, Scheinfeld NS. Necrolytic acral erythema: a review of the literature. Cutis. 2009;83:309-314.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a cutaneous sign of hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:247-251.

- Abdallah MA, Ghozzi MY, Monib HA, et al. Histological study of necrolytic acral erythema. J Ark Med Soc. 2004;100:354-355.

- Khanna VJ, Shieh S, Benjamin J, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema associated with hepatitis C: effective treatment with interferon alfa and zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:755-757.

- Abdallah MA, Hull C, Horn TD. Necrolytic acral erythema: a patient from the United States successfully treated with oral zinc. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:85-87.

- Najarian DJ, Lefkowitz I, Balfour E, et al. Zinc deficiency associated with necrolytic acral erythema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S108-S110.

- Nofal AA, Nofal E, Attwa E, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: a variant of necrolytic migratory erythema or a distinct entity? Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:916-921.

- Hivnor CM, Yan AC, Junkins-Hopkins JM, et al. Necrolytic acral erythema: response to combination therapy with interferon and ribavirin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S121-S124.

The Cruise With No Snooze

ANSWER

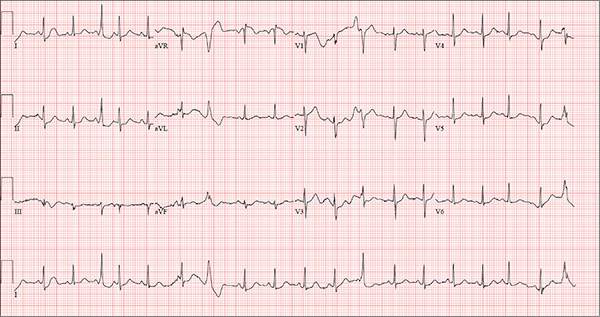

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia with premature supraventricular complexes, some with aberrant conduction.

The first, third, fourth, and 17th beats on lead I at the bottom of the rhythm strip are consistent with premature atrial contractions (PACs), while the sixth, seventh, 12th, and 19th beats represent PACs with aberrancy. The change in the QRS complex in the latter is due to the delay through the conduction system.

This patient was treated with low-dose ß-blockers and instructed to discontinue use of his holistic medication. His symptoms resolved, and follow-up ECGs have shown no evidence of sinus tachycardia or PACs.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia with premature supraventricular complexes, some with aberrant conduction.

The first, third, fourth, and 17th beats on lead I at the bottom of the rhythm strip are consistent with premature atrial contractions (PACs), while the sixth, seventh, 12th, and 19th beats represent PACs with aberrancy. The change in the QRS complex in the latter is due to the delay through the conduction system.

This patient was treated with low-dose ß-blockers and instructed to discontinue use of his holistic medication. His symptoms resolved, and follow-up ECGs have shown no evidence of sinus tachycardia or PACs.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes sinus tachycardia with premature supraventricular complexes, some with aberrant conduction.

The first, third, fourth, and 17th beats on lead I at the bottom of the rhythm strip are consistent with premature atrial contractions (PACs), while the sixth, seventh, 12th, and 19th beats represent PACs with aberrancy. The change in the QRS complex in the latter is due to the delay through the conduction system.

This patient was treated with low-dose ß-blockers and instructed to discontinue use of his holistic medication. His symptoms resolved, and follow-up ECGs have shown no evidence of sinus tachycardia or PACs.

Three weeks ago, while on a Caribbean cruise with his family, a 55-year-old man started experiencing an irregular heart rate, fluttering in his chest, and fullness in his throat. At the time, he was eating to excess, drinking heavily, and consuming three to five cups of coffee each morning to shake off the effects of the previous night. The palpitations were not noticeable during the day but were prevalent at night, when he tried to sleep. On more than one occasion, they woke him.

Since his return home, the symptoms have persisted; they now occur nightly. The patient is so concerned about them that he dreads going to bed. He has lost the 13 lb he gained on vacation and has abstained from alcohol, but he continues to drink four to six cups of coffee per day.

He denies syncope, near-syncope, chest pain, shortness of breath, and exertional dyspnea. On presentation, he is anxious to determine the cause of his symptoms and alleviate them.

The patient describes himself as active; he says he watches his diet, exercises regularly, and has never smoked. His medical history is unremarkable. He has never had surgery, and aside from sprained ankles, has had no medical treatment. His alcohol consumption, which tends to be limited to weekends, consists of four or five highballs at a time.

He is not currently taking any prescription medications, but he does admit to taking a proprietary herbal supplement that he purchases from a local Asian market. He says it “increases energy and libido.” He denies illicit drug use, now or ever.

The patient is married with three teenaged children who are all in the gifted program in high school. He and his wife are both accountants. His parents have no known medical problems; however, he is uncertain about the medical history of his grandparents.

A review of systems is unremarkable and reveals no complaints. The physical exam reveals an anxious male in no distress. His weight is 179 lb and his height, 74 in. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 140/86 mm Hg; pulse, 120 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.2°F.

The HEENT exam is remarkable for contacts but is otherwise normal. There is no thyromegaly or jugular venous distention. His lungs are clear in all fields, and there are no wheezes.

His cardiac exam reveals an irregular rhythm at a rate of 120 beats/min. There are no appreciable murmurs or rubs, given his heart rate.

The abdomen is soft and nontender, with no palpable masses. The peripheral pulses are strong bilaterally in the upper and lower extremities, and the neurologic exam is normal.

Bloodwork is performed to assess blood chemistries, complete blood count, and thyroid and liver function. All results are within normal limits. An ECG shows a ventricular rate of 123 beats/min; PR interval, 128 ms; QRS duration, 72 ms; QT/QTc interval, 308/440 ms; P axis, 43°; R axis, –2°; and T axis, 46°.

What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Altered Mental Status Demands Closer Look

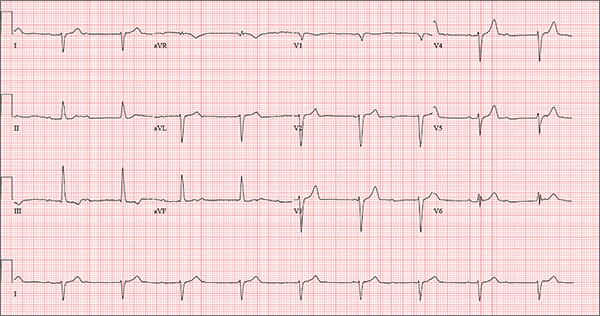

Answer

The radiograph demonstrates a normal gas pattern with a properly placed enteric feeding tube, which appears to be within the stomach. Of note is a sclerotic-appearing lesion on the posterior aspect of the left eighth rib. In a patient with a possible tumor, this lesion poses concern for potential metastasis and warrants appropriate work-up.

Answer

The radiograph demonstrates a normal gas pattern with a properly placed enteric feeding tube, which appears to be within the stomach. Of note is a sclerotic-appearing lesion on the posterior aspect of the left eighth rib. In a patient with a possible tumor, this lesion poses concern for potential metastasis and warrants appropriate work-up.

Answer

The radiograph demonstrates a normal gas pattern with a properly placed enteric feeding tube, which appears to be within the stomach. Of note is a sclerotic-appearing lesion on the posterior aspect of the left eighth rib. In a patient with a possible tumor, this lesion poses concern for potential metastasis and warrants appropriate work-up.

You receive a call from an ICU nurse regarding a patient your service is following—a 60-year-old man who was admitted for altered mental status and is being worked up for a possible brain mass. He has no other significant medical history. The nurse has placed a nasogastric feeding tube to facilitate nutrition and medication administration and has ordered a portable abdominal radiograph to confirm its placement. The completed radiograph is shown. What is your impression?