User login

Is Postop Lethargy Cause for Concern?

Answer

The radiograph shows a large cavitary lesion within the left mid-lung with evidence of an air fluid level. This finding is strongly suggestive of a postoperative abscess or empyema. Secondarily, there is some pleural thickening within the left lateral apex region. This can be suggestive of scarring or possibly a neoplasm.

The patient was admitted to the ICU for a sepsis workup, and Interventional Radiology was consulted to evaluate for CT-guided drain placement.

Answer

The radiograph shows a large cavitary lesion within the left mid-lung with evidence of an air fluid level. This finding is strongly suggestive of a postoperative abscess or empyema. Secondarily, there is some pleural thickening within the left lateral apex region. This can be suggestive of scarring or possibly a neoplasm.

The patient was admitted to the ICU for a sepsis workup, and Interventional Radiology was consulted to evaluate for CT-guided drain placement.

Answer

The radiograph shows a large cavitary lesion within the left mid-lung with evidence of an air fluid level. This finding is strongly suggestive of a postoperative abscess or empyema. Secondarily, there is some pleural thickening within the left lateral apex region. This can be suggestive of scarring or possibly a neoplasm.

The patient was admitted to the ICU for a sepsis workup, and Interventional Radiology was consulted to evaluate for CT-guided drain placement.

A 65-year-old man is transported to your emergency department from a local rehabilitation hospital. He is three weeks status post cardiac bypass surgery as well as “some other valve procedure.” In the past two to three days, staff members report, the patient has been less active and has not participated in therapy. This morning, he was found to be lethargic, and that is what prompted the call to 911. Examination reveals a lethargic male who has little verbal communication beyond moaning and groaning. His vital signs include a temperature of 36°C; blood pressure, 90/40 mm Hg; and heart rate, 135 beats/min. His O2 saturation is 90% on room air. Inspection of the patient’s chest reveals a recent, healing midline sternotomy incision. There is no overt redness or swelling. On auscultation, you note decreased breath sounds on the left side, with some coarse crackles. As you initiate your facility’s sepsis protocol order set, a stat portable chest radiograph is obtained. What is your impression?

It Reminds Him of When His Heart “Got Very Sick”

ANSWER

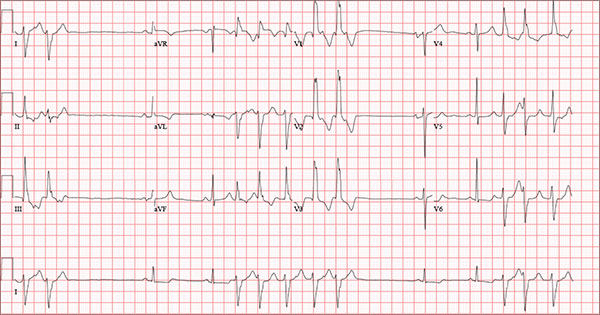

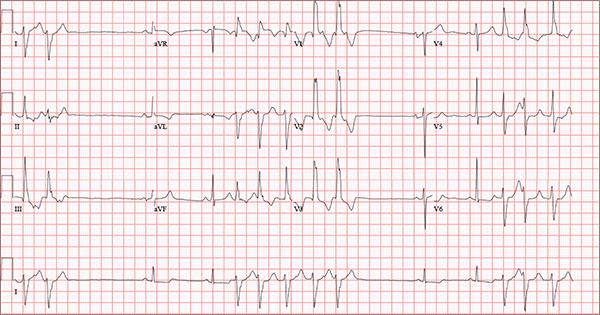

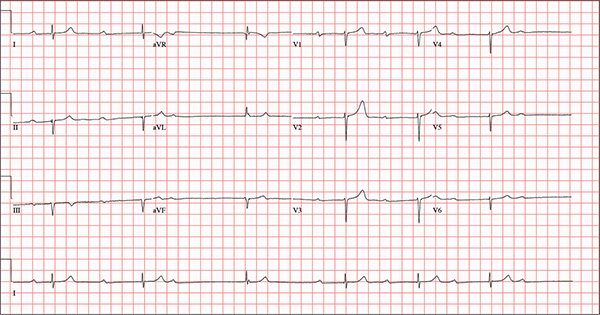

Findings on this ECG include sinus rhythm with frequent, consecutive premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) consistent with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). There is also evidence of a probable left atrial enlargement.

The key to interpreting this ECG is to first locate normal-appearing complexes. These are illustrated by the third, fourth, 10th, and 11th complexes on the rhythm strip (lead I) at the bottom of the ECG. Notice that there is a normal-appearing PQRST complex for each of these beats.

The rate of 82 beats/min is calculated from a sum average of all beats on the 12-lead ECG; however, the R-R interval between the third and fourth and the 10th and 11th beats is roughly 60 beats/min, signifying a normal sinus rhythm. All other beats are PVCs arising from the left ventricle (as evidenced by a right bundle branch pattern in lead V1).

Careful inspection will reveal retrograde P waves located in the terminal upstroke of the S wave. NSVT is defined as three or more consecutive PVCs at a rate greater than 100 beats/min with a duration of less than 30 seconds. The pauses seen between a PVC and a normally conducting P wave are caused by retrograde conduction from the ventricle to the atrium, with subsequent block within the atrium.

Finally, left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a biphasic P wave in the normally conducting beat seen in lead V1.

ANSWER

Findings on this ECG include sinus rhythm with frequent, consecutive premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) consistent with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). There is also evidence of a probable left atrial enlargement.

The key to interpreting this ECG is to first locate normal-appearing complexes. These are illustrated by the third, fourth, 10th, and 11th complexes on the rhythm strip (lead I) at the bottom of the ECG. Notice that there is a normal-appearing PQRST complex for each of these beats.

The rate of 82 beats/min is calculated from a sum average of all beats on the 12-lead ECG; however, the R-R interval between the third and fourth and the 10th and 11th beats is roughly 60 beats/min, signifying a normal sinus rhythm. All other beats are PVCs arising from the left ventricle (as evidenced by a right bundle branch pattern in lead V1).

Careful inspection will reveal retrograde P waves located in the terminal upstroke of the S wave. NSVT is defined as three or more consecutive PVCs at a rate greater than 100 beats/min with a duration of less than 30 seconds. The pauses seen between a PVC and a normally conducting P wave are caused by retrograde conduction from the ventricle to the atrium, with subsequent block within the atrium.

Finally, left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a biphasic P wave in the normally conducting beat seen in lead V1.

ANSWER

Findings on this ECG include sinus rhythm with frequent, consecutive premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) consistent with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). There is also evidence of a probable left atrial enlargement.

The key to interpreting this ECG is to first locate normal-appearing complexes. These are illustrated by the third, fourth, 10th, and 11th complexes on the rhythm strip (lead I) at the bottom of the ECG. Notice that there is a normal-appearing PQRST complex for each of these beats.

The rate of 82 beats/min is calculated from a sum average of all beats on the 12-lead ECG; however, the R-R interval between the third and fourth and the 10th and 11th beats is roughly 60 beats/min, signifying a normal sinus rhythm. All other beats are PVCs arising from the left ventricle (as evidenced by a right bundle branch pattern in lead V1).

Careful inspection will reveal retrograde P waves located in the terminal upstroke of the S wave. NSVT is defined as three or more consecutive PVCs at a rate greater than 100 beats/min with a duration of less than 30 seconds. The pauses seen between a PVC and a normally conducting P wave are caused by retrograde conduction from the ventricle to the atrium, with subsequent block within the atrium.

Finally, left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a biphasic P wave in the normally conducting beat seen in lead V1.

An 84-year-old man is transferred to your facility from a skilled nursing facility (SNF). During the routine morning vital signs check, the medical assistant (MA) at the SNF noted that the patient had a normal blood pressure but an irregular heart rate that she hadn’t observed before. The MA asked the nursing supervisor to verify her findings. The nursing supervisor noticed not only an irregular heart rate, but also pauses of up to 3 seconds. The patient denied chest pain, shortness of breath, or syncope, but he did say that twice overnight he had become lightheaded while walking from his bed to the bathroom. Upon further questioning, he informed the staff that this had happened once before: right before his “heart became very sick” and he spent a long time in the hospital “getting it fixed.” Given this history and the physical findings, the nursing supervisor called 911 to have him further evaluated. Your first impression of the patient is that he is comfortable, pleasant, and in no distress. His medical history is remarkable for a nonischemic cardiomyopathy with acute onset chronic heart failure. A year ago, he had an echocardiogram at another facility that showed aortic sclerosis, mild mitral regurgitation, and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35%. He also has a history of hypertension, COPD, hypothyroidism, and osteoarthritis. His surgical history is remarkable for bilateral knee replacements, left hip replacement, and appendectomy. Family history is significant for heart failure in both parents and in his maternal grandparents. His father died in World War I, and his mother died of complications from abdominal surgery. The patient, a retired contract painter, became a widower five years ago, when his wife died of a hemorrhagic stroke. He has no children. Before voluntarily moving to the SNF after his wife’s death, he smoked one pack of cigarettes and drank one six-pack of beer per day. He now abstains from both substances. His medication list includes metoprolol, furosemide, potassium, lisinopril, and levothyroxine. He is allergic to tetracycline antibiotics.The review of systems is remarkable for hearing loss requiring bilateral hearing aids, corrective lenses, and use of a cane for ambulation. Physical examination reveals a frail, elderly male with a weight of 148 lb and a height of 68 in. His blood pressure is 104/52 mm Hg; pulse, irregularly irregular with pauses at an average rate of 80 beats/min; and O2 saturation, 94% on room air. He is afebrile. Pertinent physical findings include corrective lenses and bilateral hearing aids. A cataract is visible on the left eye. The lungs are clear bilaterally. The cardiac exam reveals an irregular rate, a grade II/VI early systolic murmur at the left upper sternal border with radiation into the neck, a grade II/VI early diastolic murmur heard during periods of a regular heart rate, and no rubs or gallops. The abdomen is protuberant but soft, with an old right lower quadrant surgical scar. The extremities show no evidence of peripheral edema; however, there are advanced changes related to osteoarthritis in both hands, and surgical scars over both knees and the lateral aspect of his left hip. Bloodwork is obtained for analysis, and an ECG is performed. The latter reveals a ventricular rate of 82 beats/min; PR interval, 146 ms; QRS duration, 76 ms; QT/QTc interval, 438/511 ms; P axis, 73°; R axis, 62°; and T axis, 92°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Ear “Wart” Prompts Unkind Comments

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “b”), a rather common hamartomatous congenital tumor. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathologic examination of a tiny sample from the most papular portion of the lesion.

Given the lesion’s congenital nature and complete lack of response to treatment, wart (choice “a”) was quite unlikely. And although trichofolliculoma (choice “c”) and epidermal nevus (choice “d”) were possible differential items, the former usually appears much later in life and the latter is usually more dry and rough to the touch.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS) of Jadassohn was first described in 1895 by a Swedish dermatologist who had seen a series of young patients with hairless plaques in the scalp or on surrounding neck or facial skin. Pathologic exam confirmed them to be organoid nevi representing an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.

Over time, it became clear that NS affects all genders and races equally. For most patients, the lesions are of cosmetic concern due to the lack of hair. But it has also been established that NS can develop in areas, including the face, ears, and neck, on which they may be cosmetically significant and difficult to remove.

Concern arose when reports began to surface that NS could undergo malignant transformation, especially in larger scalp lesions that are subject to years of excess UV exposure. This was the driving force behind the common practice of removing NS at puberty. We now know that although basal or squamous cell carcinoma, or even melanoma, can develop in longstanding NS, the frequency is probably far less than previously thought.

Most cases of NS in the scalp are easy to diagnose by their pink color, plaquish morphology, and mammillated hairless surface (coupled with congenital manifestation). But a few, such as this patient’s ear lesion, require biopsy for confirmation. As this patient ages, he may feel the need to have the rest of it surgically removed.

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “b”), a rather common hamartomatous congenital tumor. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathologic examination of a tiny sample from the most papular portion of the lesion.

Given the lesion’s congenital nature and complete lack of response to treatment, wart (choice “a”) was quite unlikely. And although trichofolliculoma (choice “c”) and epidermal nevus (choice “d”) were possible differential items, the former usually appears much later in life and the latter is usually more dry and rough to the touch.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS) of Jadassohn was first described in 1895 by a Swedish dermatologist who had seen a series of young patients with hairless plaques in the scalp or on surrounding neck or facial skin. Pathologic exam confirmed them to be organoid nevi representing an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.

Over time, it became clear that NS affects all genders and races equally. For most patients, the lesions are of cosmetic concern due to the lack of hair. But it has also been established that NS can develop in areas, including the face, ears, and neck, on which they may be cosmetically significant and difficult to remove.

Concern arose when reports began to surface that NS could undergo malignant transformation, especially in larger scalp lesions that are subject to years of excess UV exposure. This was the driving force behind the common practice of removing NS at puberty. We now know that although basal or squamous cell carcinoma, or even melanoma, can develop in longstanding NS, the frequency is probably far less than previously thought.

Most cases of NS in the scalp are easy to diagnose by their pink color, plaquish morphology, and mammillated hairless surface (coupled with congenital manifestation). But a few, such as this patient’s ear lesion, require biopsy for confirmation. As this patient ages, he may feel the need to have the rest of it surgically removed.

ANSWER

The correct answer is nevus sebaceous (choice “b”), a rather common hamartomatous congenital tumor. The diagnosis was confirmed by pathologic examination of a tiny sample from the most papular portion of the lesion.

Given the lesion’s congenital nature and complete lack of response to treatment, wart (choice “a”) was quite unlikely. And although trichofolliculoma (choice “c”) and epidermal nevus (choice “d”) were possible differential items, the former usually appears much later in life and the latter is usually more dry and rough to the touch.

DISCUSSION

Nevus sebaceous (NS) of Jadassohn was first described in 1895 by a Swedish dermatologist who had seen a series of young patients with hairless plaques in the scalp or on surrounding neck or facial skin. Pathologic exam confirmed them to be organoid nevi representing an overgrowth of sebaceous glands.

Over time, it became clear that NS affects all genders and races equally. For most patients, the lesions are of cosmetic concern due to the lack of hair. But it has also been established that NS can develop in areas, including the face, ears, and neck, on which they may be cosmetically significant and difficult to remove.

Concern arose when reports began to surface that NS could undergo malignant transformation, especially in larger scalp lesions that are subject to years of excess UV exposure. This was the driving force behind the common practice of removing NS at puberty. We now know that although basal or squamous cell carcinoma, or even melanoma, can develop in longstanding NS, the frequency is probably far less than previously thought.

Most cases of NS in the scalp are easy to diagnose by their pink color, plaquish morphology, and mammillated hairless surface (coupled with congenital manifestation). But a few, such as this patient’s ear lesion, require biopsy for confirmation. As this patient ages, he may feel the need to have the rest of it surgically removed.

An 8-year-old boy is referred to dermatology for evaluation and treatment of a “wart” on the inferior rim of his left helix that has been present (and unchanged) since birth. The lesion is asymptomatic, and the boy’s biggest complaint is that it makes him the object of unkind comments from his siblings and friends. The patient’s mother claims the child is otherwise healthy; there is no history of seizure or other neurologic problems, and he does not have any medical conditions requiring treatment. The lesion has been treated, unsuccessfully, with a variety of wart remedies, including salicylic acid-based products and liquid nitrogen. Along the inferior rim of the left helix is a 5-cm linear collection of soft, skin-colored papules that range in size from pinpoint to 2.5 mm. They are so small and flesh-toned as to easily escape detection unless specifically sought. No other significant lesions are seen on the ear or elsewhere on the head or neck. The child looks his stated age and appears well developed and well nourished.

Exophytic Scalp Tumor

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

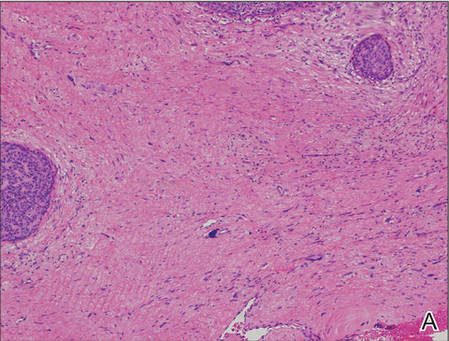

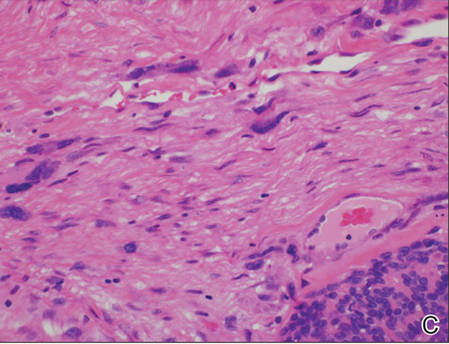

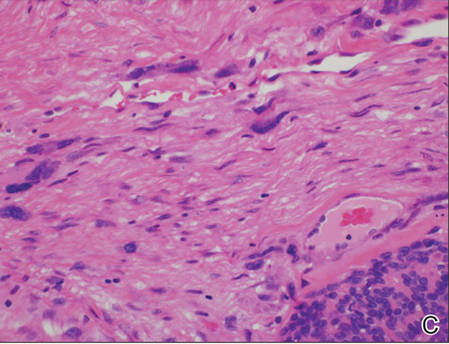

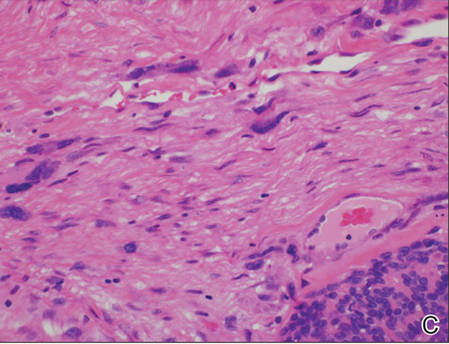

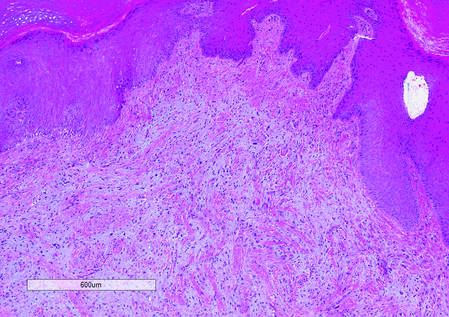

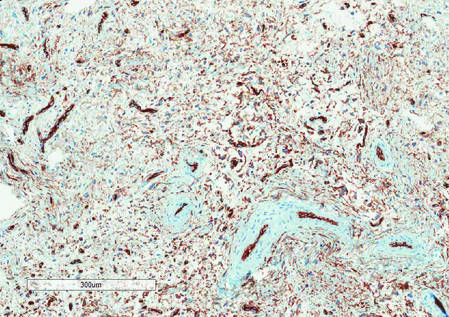

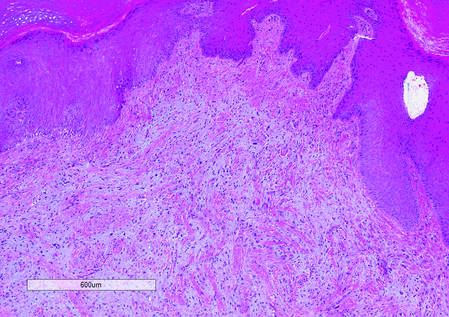

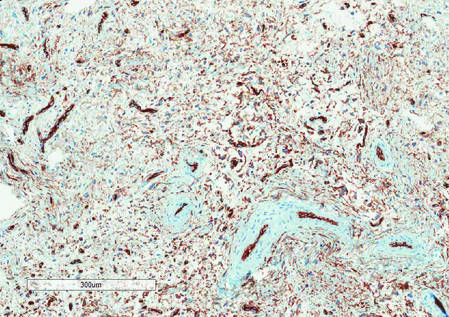

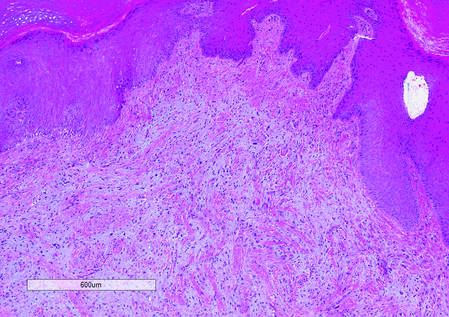

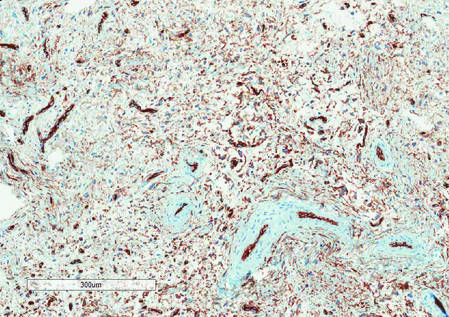

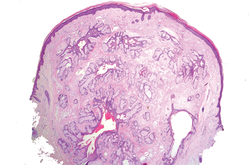

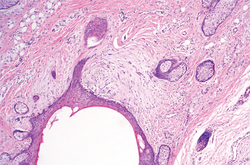

A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an infiltrating tumor consisting of malignant epithelial and stromal components (Figure). The basaloid and squamoid epithelial cells were keratin positive. The stromal cells demonstrated positivity for CD10 but were keratin negative. The epithelial portion of the tumor was composed mostly of basaloid islands of cells with nuclear pleomorphism, scattered mitoses, and focal sebaceous differentiation. The mesenchymal portion of the tumor displayed florid pleomorphism and polymorphism, with many large atypical cells and proliferation. A diagnosis of primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCC) was rendered. Head and neck computed tomography showed tumor penetration of less than 1 cm into scalp soft tissues with no involvement of the underlying bone. There was some evidence of swelling of the supragaleal soft tissues without indication of perineural spread. An 11-mm hyperlucent lower cervical lymph node on the left side that likely represented an incidental finding was noted. Surgical excision with margin evaluation was recommended, but the patient declined. He instead received radiation therapy to the left side of the posterior scalp with a total dose of 30 Gy at 6 Gy per fraction and 1 fraction daily. The patient was found to have a well-healed scar with no evidence of recurrence at 4-week follow-up and again at 5 months after radiation therapy.

|

|

|

| A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an inflitrating tumor consisting on malignant epithelial and stromal components (A-C)(H&E; original magnifications ×10, ×20, and ×40, respectively). |

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.1 Carcinosarcomas have been reported in both the male and female reproductive tracts, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, breasts, larynx, thymus, and thyroid but is uncommon as a primary neoplasm of the skin.2 Epidermal PCC occurs with greater frequency in males than in females and typically presents in the eighth or ninth decades of life.3 These tumors tend to arise in sun-exposed regions, most commonly on the face and scalp.2

Morphologically, PCCs typically are exophytic growths that often feature surface ulceration and may or may not bleed upon palpation.4 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas may present as long-standing lesions that have undergone rapid transformation in the weeks preceding presentation.4 It is not uncommon for PCC lesions to carry the clinical diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, which suggests notable morphologic overlap between these entities. Histopathologically, PCC shows a basal cell carcinoma and/or a squamous cell carcinoma epithelial component intimately admixed with a sarcomatous component.5 The mesenchymal component of PCC typically resembles a superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma characterized by pleomorphic nuclei and cytoplasm, necrosis, and an increased number of mitotic figures.2 Immunohistochemistry can be beneficial in the diagnosis of PCC. A combination of p63 and AE1/AE3 stains can be used to confirm cells of epithelial origin. Staining with vimentin, CD10, or caldesmon can help to delineate the mesenchymal component of PCC.

Epidermal PCC most commonly affects elderly individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure. It has been suggested that p53 mutations due to UV damage are key in tumor formation for both epithelial and mesenchymal elements.5 Literature supports a monoclonal origin for the epithelial and mesenchymal components of this tumor; however, there is insufficient evidence.6 Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for epidermal PCC, but adjuvant or substitutive radiotherapy has been used in some cases.4 The prognosis of PCC is notably better than its visceral counterpart due to early diagnosis and treatment of easily visible lesions. Epidermal PCC has a 70% 5-year disease-free survival rate, while adnexal PCC tends to occur in younger patients and has a 25% 5-year disease-free survival rate.3 Due to the rarity of reported cases and limited follow-up, the long-term prognosis for PCC remains unclear.

We report an unusual case of PCC on the scalp that was successfully treated with radiation therapy alone. This modality should be considered in patients with large tumors who refuse surgery or are not good surgical candidates.

1. El Harroudi T, Ech-Charif S, Amrani M, et al. Primary carcinosarcoma of the skin. J Hand Microsurg. 2010;2:79-81.

2. Patel NK, McKee PH, Smith NP. Primary metaplastic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:363-372.

3. Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

4. Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

5. Tran TA, Muller S, Chaudahri PJ, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: adnexal vs. epidermal types define high- and low-risk tumors. results of a meta-analysis. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:2-11.

6. Paniz Mondolfi AE, Jour G, Johnson M, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: insights into its clonal origin and mutational pattern expression analysis through next-generation sequencing. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2853-2860.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an infiltrating tumor consisting of malignant epithelial and stromal components (Figure). The basaloid and squamoid epithelial cells were keratin positive. The stromal cells demonstrated positivity for CD10 but were keratin negative. The epithelial portion of the tumor was composed mostly of basaloid islands of cells with nuclear pleomorphism, scattered mitoses, and focal sebaceous differentiation. The mesenchymal portion of the tumor displayed florid pleomorphism and polymorphism, with many large atypical cells and proliferation. A diagnosis of primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCC) was rendered. Head and neck computed tomography showed tumor penetration of less than 1 cm into scalp soft tissues with no involvement of the underlying bone. There was some evidence of swelling of the supragaleal soft tissues without indication of perineural spread. An 11-mm hyperlucent lower cervical lymph node on the left side that likely represented an incidental finding was noted. Surgical excision with margin evaluation was recommended, but the patient declined. He instead received radiation therapy to the left side of the posterior scalp with a total dose of 30 Gy at 6 Gy per fraction and 1 fraction daily. The patient was found to have a well-healed scar with no evidence of recurrence at 4-week follow-up and again at 5 months after radiation therapy.

|

|

|

| A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an inflitrating tumor consisting on malignant epithelial and stromal components (A-C)(H&E; original magnifications ×10, ×20, and ×40, respectively). |

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.1 Carcinosarcomas have been reported in both the male and female reproductive tracts, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, breasts, larynx, thymus, and thyroid but is uncommon as a primary neoplasm of the skin.2 Epidermal PCC occurs with greater frequency in males than in females and typically presents in the eighth or ninth decades of life.3 These tumors tend to arise in sun-exposed regions, most commonly on the face and scalp.2

Morphologically, PCCs typically are exophytic growths that often feature surface ulceration and may or may not bleed upon palpation.4 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas may present as long-standing lesions that have undergone rapid transformation in the weeks preceding presentation.4 It is not uncommon for PCC lesions to carry the clinical diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, which suggests notable morphologic overlap between these entities. Histopathologically, PCC shows a basal cell carcinoma and/or a squamous cell carcinoma epithelial component intimately admixed with a sarcomatous component.5 The mesenchymal component of PCC typically resembles a superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma characterized by pleomorphic nuclei and cytoplasm, necrosis, and an increased number of mitotic figures.2 Immunohistochemistry can be beneficial in the diagnosis of PCC. A combination of p63 and AE1/AE3 stains can be used to confirm cells of epithelial origin. Staining with vimentin, CD10, or caldesmon can help to delineate the mesenchymal component of PCC.

Epidermal PCC most commonly affects elderly individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure. It has been suggested that p53 mutations due to UV damage are key in tumor formation for both epithelial and mesenchymal elements.5 Literature supports a monoclonal origin for the epithelial and mesenchymal components of this tumor; however, there is insufficient evidence.6 Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for epidermal PCC, but adjuvant or substitutive radiotherapy has been used in some cases.4 The prognosis of PCC is notably better than its visceral counterpart due to early diagnosis and treatment of easily visible lesions. Epidermal PCC has a 70% 5-year disease-free survival rate, while adnexal PCC tends to occur in younger patients and has a 25% 5-year disease-free survival rate.3 Due to the rarity of reported cases and limited follow-up, the long-term prognosis for PCC remains unclear.

We report an unusual case of PCC on the scalp that was successfully treated with radiation therapy alone. This modality should be considered in patients with large tumors who refuse surgery or are not good surgical candidates.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an infiltrating tumor consisting of malignant epithelial and stromal components (Figure). The basaloid and squamoid epithelial cells were keratin positive. The stromal cells demonstrated positivity for CD10 but were keratin negative. The epithelial portion of the tumor was composed mostly of basaloid islands of cells with nuclear pleomorphism, scattered mitoses, and focal sebaceous differentiation. The mesenchymal portion of the tumor displayed florid pleomorphism and polymorphism, with many large atypical cells and proliferation. A diagnosis of primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCC) was rendered. Head and neck computed tomography showed tumor penetration of less than 1 cm into scalp soft tissues with no involvement of the underlying bone. There was some evidence of swelling of the supragaleal soft tissues without indication of perineural spread. An 11-mm hyperlucent lower cervical lymph node on the left side that likely represented an incidental finding was noted. Surgical excision with margin evaluation was recommended, but the patient declined. He instead received radiation therapy to the left side of the posterior scalp with a total dose of 30 Gy at 6 Gy per fraction and 1 fraction daily. The patient was found to have a well-healed scar with no evidence of recurrence at 4-week follow-up and again at 5 months after radiation therapy.

|

|

|

| A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an inflitrating tumor consisting on malignant epithelial and stromal components (A-C)(H&E; original magnifications ×10, ×20, and ×40, respectively). |

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.1 Carcinosarcomas have been reported in both the male and female reproductive tracts, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, breasts, larynx, thymus, and thyroid but is uncommon as a primary neoplasm of the skin.2 Epidermal PCC occurs with greater frequency in males than in females and typically presents in the eighth or ninth decades of life.3 These tumors tend to arise in sun-exposed regions, most commonly on the face and scalp.2

Morphologically, PCCs typically are exophytic growths that often feature surface ulceration and may or may not bleed upon palpation.4 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas may present as long-standing lesions that have undergone rapid transformation in the weeks preceding presentation.4 It is not uncommon for PCC lesions to carry the clinical diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, which suggests notable morphologic overlap between these entities. Histopathologically, PCC shows a basal cell carcinoma and/or a squamous cell carcinoma epithelial component intimately admixed with a sarcomatous component.5 The mesenchymal component of PCC typically resembles a superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma characterized by pleomorphic nuclei and cytoplasm, necrosis, and an increased number of mitotic figures.2 Immunohistochemistry can be beneficial in the diagnosis of PCC. A combination of p63 and AE1/AE3 stains can be used to confirm cells of epithelial origin. Staining with vimentin, CD10, or caldesmon can help to delineate the mesenchymal component of PCC.

Epidermal PCC most commonly affects elderly individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure. It has been suggested that p53 mutations due to UV damage are key in tumor formation for both epithelial and mesenchymal elements.5 Literature supports a monoclonal origin for the epithelial and mesenchymal components of this tumor; however, there is insufficient evidence.6 Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for epidermal PCC, but adjuvant or substitutive radiotherapy has been used in some cases.4 The prognosis of PCC is notably better than its visceral counterpart due to early diagnosis and treatment of easily visible lesions. Epidermal PCC has a 70% 5-year disease-free survival rate, while adnexal PCC tends to occur in younger patients and has a 25% 5-year disease-free survival rate.3 Due to the rarity of reported cases and limited follow-up, the long-term prognosis for PCC remains unclear.

We report an unusual case of PCC on the scalp that was successfully treated with radiation therapy alone. This modality should be considered in patients with large tumors who refuse surgery or are not good surgical candidates.

1. El Harroudi T, Ech-Charif S, Amrani M, et al. Primary carcinosarcoma of the skin. J Hand Microsurg. 2010;2:79-81.

2. Patel NK, McKee PH, Smith NP. Primary metaplastic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:363-372.

3. Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

4. Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

5. Tran TA, Muller S, Chaudahri PJ, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: adnexal vs. epidermal types define high- and low-risk tumors. results of a meta-analysis. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:2-11.

6. Paniz Mondolfi AE, Jour G, Johnson M, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: insights into its clonal origin and mutational pattern expression analysis through next-generation sequencing. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2853-2860.

1. El Harroudi T, Ech-Charif S, Amrani M, et al. Primary carcinosarcoma of the skin. J Hand Microsurg. 2010;2:79-81.

2. Patel NK, McKee PH, Smith NP. Primary metaplastic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:363-372.

3. Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

4. Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

5. Tran TA, Muller S, Chaudahri PJ, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: adnexal vs. epidermal types define high- and low-risk tumors. results of a meta-analysis. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:2-11.

6. Paniz Mondolfi AE, Jour G, Johnson M, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: insights into its clonal origin and mutational pattern expression analysis through next-generation sequencing. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2853-2860.

An 81-year-old man presented with a 3.5×3.0-cm pink exophytic tumor with an eroded surface and prominent vascularity on the left side of the parietal scalp. The patient reported that the tumor had been present for more than 30 years but recently had grown larger in size. He denied pain or pruritus in association with the lesion and did not report any systemic symptoms. He had received no prior treatments for the tumor.

Painful Lesions on the Tongue

The Diagnosis: Herpetic Glossitis

Oral lesions of the tongue are common during primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, though most primary oral herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections occur during childhood or early adulthood. Reactivation of HSV type 1 most commonly manifests as herpes labialis.1 When recurrent HSV involves intraoral lesions, they are typically confined to the gingiva and palate, sparing the tongue.

Clinical presentation of herpetic glossitis varies. Recurrent herpetic glossitis has been described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematologic malignancies and organ transplants.2 In addition, immunocompromised and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients may present with deep and/or broad ulcers. A case of herpes infection presenting with nodules on the tongue has been reported in Hodgkin disease.3 Herpetic geometric glossitis also has been described, which is a linear, crosshatched, or sharply angled branching with painful fissuring of the tongue. Herpetic geometric glossitis has been reported to occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.4 Tongue involvement during oral reactivation of HSV is exceedingly rare and the pathogenesis remains elusive, though one hypothesis proposes a protective role of salivary-specific IgA and lysozyme.5 Here, we report a case in which a patient developed similar lingual HSV lesions following recent immunosuppression.

1. Arduino PG, Porter SR. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:107-121.

2. Nikkels AF, Piérard GE. Chronic herpes simplex virus type I glossitis in an immunocompromised man. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:343-346.

3. Leming PD, Martin SE, Zwelling LA. Atypical herpes simplex (HSV) infection in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1984;54:3043-3047.

4. Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Herpetic geometric glossitis in an immunocompetent patient with pneumonia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:139-142.

5. Heineman HS, Greenberg MS. Cell protective effect of human saliva specific for herpes simplex virus. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:257-261.

The Diagnosis: Herpetic Glossitis

Oral lesions of the tongue are common during primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, though most primary oral herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections occur during childhood or early adulthood. Reactivation of HSV type 1 most commonly manifests as herpes labialis.1 When recurrent HSV involves intraoral lesions, they are typically confined to the gingiva and palate, sparing the tongue.

Clinical presentation of herpetic glossitis varies. Recurrent herpetic glossitis has been described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematologic malignancies and organ transplants.2 In addition, immunocompromised and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients may present with deep and/or broad ulcers. A case of herpes infection presenting with nodules on the tongue has been reported in Hodgkin disease.3 Herpetic geometric glossitis also has been described, which is a linear, crosshatched, or sharply angled branching with painful fissuring of the tongue. Herpetic geometric glossitis has been reported to occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.4 Tongue involvement during oral reactivation of HSV is exceedingly rare and the pathogenesis remains elusive, though one hypothesis proposes a protective role of salivary-specific IgA and lysozyme.5 Here, we report a case in which a patient developed similar lingual HSV lesions following recent immunosuppression.

The Diagnosis: Herpetic Glossitis

Oral lesions of the tongue are common during primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, though most primary oral herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections occur during childhood or early adulthood. Reactivation of HSV type 1 most commonly manifests as herpes labialis.1 When recurrent HSV involves intraoral lesions, they are typically confined to the gingiva and palate, sparing the tongue.

Clinical presentation of herpetic glossitis varies. Recurrent herpetic glossitis has been described in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematologic malignancies and organ transplants.2 In addition, immunocompromised and human immunodeficiency virus–infected patients may present with deep and/or broad ulcers. A case of herpes infection presenting with nodules on the tongue has been reported in Hodgkin disease.3 Herpetic geometric glossitis also has been described, which is a linear, crosshatched, or sharply angled branching with painful fissuring of the tongue. Herpetic geometric glossitis has been reported to occur in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.4 Tongue involvement during oral reactivation of HSV is exceedingly rare and the pathogenesis remains elusive, though one hypothesis proposes a protective role of salivary-specific IgA and lysozyme.5 Here, we report a case in which a patient developed similar lingual HSV lesions following recent immunosuppression.

1. Arduino PG, Porter SR. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:107-121.

2. Nikkels AF, Piérard GE. Chronic herpes simplex virus type I glossitis in an immunocompromised man. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:343-346.

3. Leming PD, Martin SE, Zwelling LA. Atypical herpes simplex (HSV) infection in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1984;54:3043-3047.

4. Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Herpetic geometric glossitis in an immunocompetent patient with pneumonia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:139-142.

5. Heineman HS, Greenberg MS. Cell protective effect of human saliva specific for herpes simplex virus. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:257-261.

1. Arduino PG, Porter SR. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection: overview on relevant clinico-pathological features. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37:107-121.

2. Nikkels AF, Piérard GE. Chronic herpes simplex virus type I glossitis in an immunocompromised man. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:343-346.

3. Leming PD, Martin SE, Zwelling LA. Atypical herpes simplex (HSV) infection in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer. 1984;54:3043-3047.

4. Mirowski GW, Goddard A. Herpetic geometric glossitis in an immunocompetent patient with pneumonia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:139-142.

5. Heineman HS, Greenberg MS. Cell protective effect of human saliva specific for herpes simplex virus. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:257-261.

A 77-year-old man with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and recent pneumonia was treated with oral prednisone 40 mg daily, antibiotics, and a fluticasone-salmeterol inhaler. One week into treatment, the patient developed painful lesions limited to the oral cavity. Physical examination revealed many fixed, umbilicated, white-tan plaques on the lower lips, tongue, and posterior aspect of the oropharynx. The dermatology department was consulted because the lesions failed to respond to nystatin oral suspension.

Toe Nodule Obliterating the Nail Bed

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAF) was first described in 2001 by Fetsch et al.1 Subsequently, the term digital fibromyxoma was proposed in 2012 by Hollmann et al2 to describe a distinctive, slow-growing, soft-tissue tumor with a predilection for the periungual or subungual regions of the fingers and toes. The benign growth typically presents as a painless or tender nodule in middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance (1.3:1 ratio).1,2 In a case series (N=124) described by Hollmann et al,2 9 of 25 patients (36%) who had imaging studies showed bone involvement by an erosive or lytic lesion. Reports of SAF with bone involvement also have been described in the radiologic and orthopedic surgery literature.3,4 Radiographically, the soft-tissue invasion of the bone is demonstrated by scalloping on plain radiographs (Figure 1).3

Histologically, SAFs are moderately cellular with spindled or stellate fibroblastlike cells within a myxoid or collagenous matrix (Figure 2).1 The vasculature is mildly accentuated and an increase in mast cells usually is observed. The nuclei have a low degree of atypia with few mitotic figures, and the stellate cells exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and CD99.1 Hollmann et al2 found that 66 of 95 tumors (69.5%) infiltrated the dermal collagen, 26 (27.4%) infiltrated fat, and 3 (3.2%) invaded bone. Of the 47 cases that were evaluated on follow-up, 10 tumors (21.3%) recurred locally (all near the nail unit of the fingers or toes) after a mean interval of 27 months. Although invasion of underlying tissues and recurrence of the tumor has been demonstrated, this growth is considered benign. The histologic differential diagnosis includes neurofibroma, myxoma, fibroma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, dermatofibroma, superficial angiomyxoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.2

The primary treatment of SAF is local excision. The incidence of local recurrence found in the case series by Hollmann et al2 was directly linked to positive margins after the first excision (10/47 [21.3%] recurrent lesions had positive margins). To date, there are no known reports of metastatic disease in SAF.2 Our case manifested with a late recurrence of the tumor and bone involvement requiring surgical excision, which illustrates the role of adjuvant imaging and close follow-up following excision of any soft-tissue tumors of the fingers and toes that have been histologically confirmed as SAF, particularly those of the periungual region.

|

|

|

|

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma (a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes.) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

3. Varikatt W, Soper J, Simmon G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a report of two cases with radiological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:499-503.

4. Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx. a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAF) was first described in 2001 by Fetsch et al.1 Subsequently, the term digital fibromyxoma was proposed in 2012 by Hollmann et al2 to describe a distinctive, slow-growing, soft-tissue tumor with a predilection for the periungual or subungual regions of the fingers and toes. The benign growth typically presents as a painless or tender nodule in middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance (1.3:1 ratio).1,2 In a case series (N=124) described by Hollmann et al,2 9 of 25 patients (36%) who had imaging studies showed bone involvement by an erosive or lytic lesion. Reports of SAF with bone involvement also have been described in the radiologic and orthopedic surgery literature.3,4 Radiographically, the soft-tissue invasion of the bone is demonstrated by scalloping on plain radiographs (Figure 1).3

Histologically, SAFs are moderately cellular with spindled or stellate fibroblastlike cells within a myxoid or collagenous matrix (Figure 2).1 The vasculature is mildly accentuated and an increase in mast cells usually is observed. The nuclei have a low degree of atypia with few mitotic figures, and the stellate cells exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and CD99.1 Hollmann et al2 found that 66 of 95 tumors (69.5%) infiltrated the dermal collagen, 26 (27.4%) infiltrated fat, and 3 (3.2%) invaded bone. Of the 47 cases that were evaluated on follow-up, 10 tumors (21.3%) recurred locally (all near the nail unit of the fingers or toes) after a mean interval of 27 months. Although invasion of underlying tissues and recurrence of the tumor has been demonstrated, this growth is considered benign. The histologic differential diagnosis includes neurofibroma, myxoma, fibroma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, dermatofibroma, superficial angiomyxoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.2

The primary treatment of SAF is local excision. The incidence of local recurrence found in the case series by Hollmann et al2 was directly linked to positive margins after the first excision (10/47 [21.3%] recurrent lesions had positive margins). To date, there are no known reports of metastatic disease in SAF.2 Our case manifested with a late recurrence of the tumor and bone involvement requiring surgical excision, which illustrates the role of adjuvant imaging and close follow-up following excision of any soft-tissue tumors of the fingers and toes that have been histologically confirmed as SAF, particularly those of the periungual region.

|

|

|

|

The Diagnosis: Superficial Acral Fibromyxoma

Superficial acral fibromyxoma (SAF) was first described in 2001 by Fetsch et al.1 Subsequently, the term digital fibromyxoma was proposed in 2012 by Hollmann et al2 to describe a distinctive, slow-growing, soft-tissue tumor with a predilection for the periungual or subungual regions of the fingers and toes. The benign growth typically presents as a painless or tender nodule in middle-aged adults with a slight male predominance (1.3:1 ratio).1,2 In a case series (N=124) described by Hollmann et al,2 9 of 25 patients (36%) who had imaging studies showed bone involvement by an erosive or lytic lesion. Reports of SAF with bone involvement also have been described in the radiologic and orthopedic surgery literature.3,4 Radiographically, the soft-tissue invasion of the bone is demonstrated by scalloping on plain radiographs (Figure 1).3

Histologically, SAFs are moderately cellular with spindled or stellate fibroblastlike cells within a myxoid or collagenous matrix (Figure 2).1 The vasculature is mildly accentuated and an increase in mast cells usually is observed. The nuclei have a low degree of atypia with few mitotic figures, and the stellate cells exhibit positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (Figure 3), epithelial membrane antigen, and CD99.1 Hollmann et al2 found that 66 of 95 tumors (69.5%) infiltrated the dermal collagen, 26 (27.4%) infiltrated fat, and 3 (3.2%) invaded bone. Of the 47 cases that were evaluated on follow-up, 10 tumors (21.3%) recurred locally (all near the nail unit of the fingers or toes) after a mean interval of 27 months. Although invasion of underlying tissues and recurrence of the tumor has been demonstrated, this growth is considered benign. The histologic differential diagnosis includes neurofibroma, myxoma, fibroma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, dermatofibroma, superficial angiomyxoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.2

The primary treatment of SAF is local excision. The incidence of local recurrence found in the case series by Hollmann et al2 was directly linked to positive margins after the first excision (10/47 [21.3%] recurrent lesions had positive margins). To date, there are no known reports of metastatic disease in SAF.2 Our case manifested with a late recurrence of the tumor and bone involvement requiring surgical excision, which illustrates the role of adjuvant imaging and close follow-up following excision of any soft-tissue tumors of the fingers and toes that have been histologically confirmed as SAF, particularly those of the periungual region.

|

|

|

|

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma (a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes.) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

3. Varikatt W, Soper J, Simmon G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a report of two cases with radiological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:499-503.

4. Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx. a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

1. Fetsch JF, Laskin WB, Miettinen M. Superficial acral fibromyxoma (a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 37 cases of a distinctive soft tissue tumor with a predilection for the fingers and toes.) Hum Pathol. 2001;32:704-714.

2. Hollmann TJ, Bovée JV, Fletcher CD. Digital fibromyxoma (superficial acral fibromyxoma): a detailed characterization of 124 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:789-798.

3. Varikatt W, Soper J, Simmon G, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma: a report of two cases with radiological findings. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:499-503.

4. Oteo-Alvaro A, Meizoso T, Scarpellini A, et al. Superficial acral fibromyxoma of the toe, with erosion of the distal phalanx. a clinical report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:271-274.

A generally healthy 30-year-old man presented with a 3-cm exophytic, yellowish red, subungual nodule of the left great toe of 1 year’s duration that was obliterating the nail plate. Ten years prior, a similar nodule in the same location was removed via laser by a podiatrist. Medical records were not retrievable, but the patient reported that he was told the excised lesion was a benign tumor. Plain radiographs were performed at the current presentation and demonstrated an inferior cortical lucency of the distal phalanx as well as a lucency over the nail bed region with extension of calcification to the soft tissues. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a mass with a proximal to distal maximum dimension of 2.1 cm that involved the dorsal surface of the proximal phalanx. Magnetic resonance imaging also demonstrated bone erosion from the overlying mass. A 4-mm incisional punch biopsy was performed prior to surgical excision.

Dome-Shaped Papule With a Bloody Crust

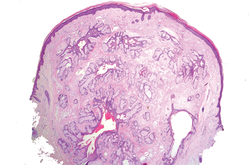

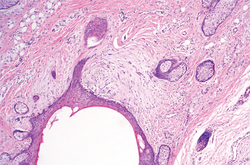

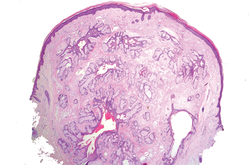

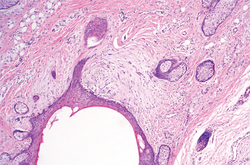

The Diagnosis: Congenital Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (FSCH) is a rare skin condition that is either congenital or acquired. It presents as a slow-growing and flesh-colored papulonodular lesion1 that mainly occurs on the head and neck. Involvement of the nipples, perineum, back, forearms, genital areas, and subcutaneous tissue also has been reported but usually indicates a larger lesion.1,2

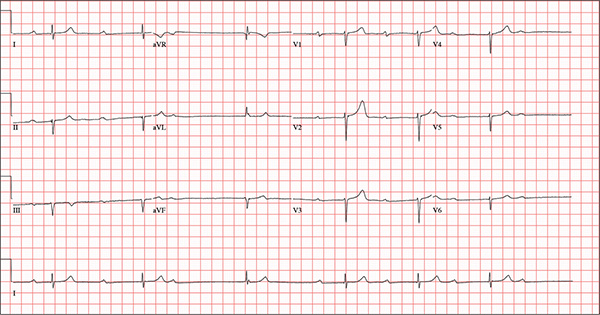

Histologically, FSCH is considered a hamartoma composed of both ectodermal and mesodermal elements.1 Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a more complex lesion composed of infundibulocystic structures connected to maloriented folliculosebaceous units surrounded by whorls of highly vascularized fibrous stroma and adipocytes. Clefts between fibroepithelial units and surrounding stroma usually are present.1

Epithelial components contribute to the adnexal and folliculosebaceous cystic proliferations, and mesenchymal elements include vascular tissue, adipose tissue, and fibroblast-rich stroma.1,2 Acquired lesions arising in adults have been described,1-5 but the congenital presentation of FSCH in infancy is rare.

Histopathologically, some variations of FSCH are mainly composed of epithelial components while others are composed of nonepithelial components. Nonepithelial components include neural proliferation, muscle components, vascular proliferation, and mucin deposition.1-4 In some cases, FSCH may coexist with other diseases, such as nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis and neurofibromatosis type I.4,5

In our case, histopathology showed several dermal infundibulocystic structures that were lined by stratified squamous epithelium and contained horny material (Figure 1). Numerous immature sebaceous lobules and rudimentary hair follicles emanated from some of the cyst walls. Mesenchymal changes around the fibroepithelial units included fibrillary bundles of collagen, clusters of adipocytes, and an increased number of small venules (Figure 2). In addition, the stroma adjacent to the malformed perifollicle contained some amount of mucin. Prominent clefts formed between fibroepithelial units and the surrounding altered stroma.

|

| |

|

The differential diagnosis mainly includes sebaceous trichofolliculoma, molluscum contagiosum, dermoid cysts, pilomatrixoma, Spitz nevus, and nevus lipomatosus superficialis. The differential diagnosis between FSCH and sebaceous trichofolliculoma is challenging. Both lesions show an infundibular cyst and surrounding sebaceous nodules. According to Plewig,6 trichofolliculoma has a wide spectrum ranging from low to high differentiation represented by trichofolliculoma, sebaceous trichofolliculoma, and FSCH, respectively. It is not difficult to distinguish FSCH from other diseases according to its peculiar histopathologic features.

The clinicopathologic features of our case were similar to those of reported FSCH cases, except for the following unique characteristics: congenital lesion, lack of terminal hair, and no sebaceous material extrusion. These features of hair and sebaceous material may be correlated with the patient’s age and hormonal level.1 Androgen may play a key role in sebaceous gland development at puberty, which leads to sebaceous gland hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Therefore, slight pressure from the lesions can make ivory-white sebaceous material discharge. Hence, the dermatologist and pediatrician must be poised and sensitive while making an initial diagnosis of FSCH.

1. Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma: a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

2. Moriki M, Ito T, Hirakawa S, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma presenting as a subcutaneous nodule on the thigh. J Dermatol. 2013;40:483-484.

3. Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma with perifollicular mucinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:58-62.

4. Brasanac D, Boricic I. Giant nevus lipomatosus superficialis with multiple folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and dermoid cysts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:84-86.

5. Noh S, Kwon JE, Lee KG, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S185-S187.

6. Plewig G. In discussion of: Leserbrief zu Zheng LQ, Han XC, Huang Y, Li HW. Several acneiform papules and nodules on the neck. diagnosis: folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:824-825.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (FSCH) is a rare skin condition that is either congenital or acquired. It presents as a slow-growing and flesh-colored papulonodular lesion1 that mainly occurs on the head and neck. Involvement of the nipples, perineum, back, forearms, genital areas, and subcutaneous tissue also has been reported but usually indicates a larger lesion.1,2

Histologically, FSCH is considered a hamartoma composed of both ectodermal and mesodermal elements.1 Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a more complex lesion composed of infundibulocystic structures connected to maloriented folliculosebaceous units surrounded by whorls of highly vascularized fibrous stroma and adipocytes. Clefts between fibroepithelial units and surrounding stroma usually are present.1

Epithelial components contribute to the adnexal and folliculosebaceous cystic proliferations, and mesenchymal elements include vascular tissue, adipose tissue, and fibroblast-rich stroma.1,2 Acquired lesions arising in adults have been described,1-5 but the congenital presentation of FSCH in infancy is rare.

Histopathologically, some variations of FSCH are mainly composed of epithelial components while others are composed of nonepithelial components. Nonepithelial components include neural proliferation, muscle components, vascular proliferation, and mucin deposition.1-4 In some cases, FSCH may coexist with other diseases, such as nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis and neurofibromatosis type I.4,5

In our case, histopathology showed several dermal infundibulocystic structures that were lined by stratified squamous epithelium and contained horny material (Figure 1). Numerous immature sebaceous lobules and rudimentary hair follicles emanated from some of the cyst walls. Mesenchymal changes around the fibroepithelial units included fibrillary bundles of collagen, clusters of adipocytes, and an increased number of small venules (Figure 2). In addition, the stroma adjacent to the malformed perifollicle contained some amount of mucin. Prominent clefts formed between fibroepithelial units and the surrounding altered stroma.

|

| |

|

The differential diagnosis mainly includes sebaceous trichofolliculoma, molluscum contagiosum, dermoid cysts, pilomatrixoma, Spitz nevus, and nevus lipomatosus superficialis. The differential diagnosis between FSCH and sebaceous trichofolliculoma is challenging. Both lesions show an infundibular cyst and surrounding sebaceous nodules. According to Plewig,6 trichofolliculoma has a wide spectrum ranging from low to high differentiation represented by trichofolliculoma, sebaceous trichofolliculoma, and FSCH, respectively. It is not difficult to distinguish FSCH from other diseases according to its peculiar histopathologic features.

The clinicopathologic features of our case were similar to those of reported FSCH cases, except for the following unique characteristics: congenital lesion, lack of terminal hair, and no sebaceous material extrusion. These features of hair and sebaceous material may be correlated with the patient’s age and hormonal level.1 Androgen may play a key role in sebaceous gland development at puberty, which leads to sebaceous gland hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Therefore, slight pressure from the lesions can make ivory-white sebaceous material discharge. Hence, the dermatologist and pediatrician must be poised and sensitive while making an initial diagnosis of FSCH.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Folliculosebaceous Cystic Hamartoma

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma (FSCH) is a rare skin condition that is either congenital or acquired. It presents as a slow-growing and flesh-colored papulonodular lesion1 that mainly occurs on the head and neck. Involvement of the nipples, perineum, back, forearms, genital areas, and subcutaneous tissue also has been reported but usually indicates a larger lesion.1,2

Histologically, FSCH is considered a hamartoma composed of both ectodermal and mesodermal elements.1 Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma is a more complex lesion composed of infundibulocystic structures connected to maloriented folliculosebaceous units surrounded by whorls of highly vascularized fibrous stroma and adipocytes. Clefts between fibroepithelial units and surrounding stroma usually are present.1

Epithelial components contribute to the adnexal and folliculosebaceous cystic proliferations, and mesenchymal elements include vascular tissue, adipose tissue, and fibroblast-rich stroma.1,2 Acquired lesions arising in adults have been described,1-5 but the congenital presentation of FSCH in infancy is rare.

Histopathologically, some variations of FSCH are mainly composed of epithelial components while others are composed of nonepithelial components. Nonepithelial components include neural proliferation, muscle components, vascular proliferation, and mucin deposition.1-4 In some cases, FSCH may coexist with other diseases, such as nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis and neurofibromatosis type I.4,5

In our case, histopathology showed several dermal infundibulocystic structures that were lined by stratified squamous epithelium and contained horny material (Figure 1). Numerous immature sebaceous lobules and rudimentary hair follicles emanated from some of the cyst walls. Mesenchymal changes around the fibroepithelial units included fibrillary bundles of collagen, clusters of adipocytes, and an increased number of small venules (Figure 2). In addition, the stroma adjacent to the malformed perifollicle contained some amount of mucin. Prominent clefts formed between fibroepithelial units and the surrounding altered stroma.

|

| |

|

The differential diagnosis mainly includes sebaceous trichofolliculoma, molluscum contagiosum, dermoid cysts, pilomatrixoma, Spitz nevus, and nevus lipomatosus superficialis. The differential diagnosis between FSCH and sebaceous trichofolliculoma is challenging. Both lesions show an infundibular cyst and surrounding sebaceous nodules. According to Plewig,6 trichofolliculoma has a wide spectrum ranging from low to high differentiation represented by trichofolliculoma, sebaceous trichofolliculoma, and FSCH, respectively. It is not difficult to distinguish FSCH from other diseases according to its peculiar histopathologic features.

The clinicopathologic features of our case were similar to those of reported FSCH cases, except for the following unique characteristics: congenital lesion, lack of terminal hair, and no sebaceous material extrusion. These features of hair and sebaceous material may be correlated with the patient’s age and hormonal level.1 Androgen may play a key role in sebaceous gland development at puberty, which leads to sebaceous gland hyperplasia and hypertrophy. Therefore, slight pressure from the lesions can make ivory-white sebaceous material discharge. Hence, the dermatologist and pediatrician must be poised and sensitive while making an initial diagnosis of FSCH.

1. Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma: a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

2. Moriki M, Ito T, Hirakawa S, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma presenting as a subcutaneous nodule on the thigh. J Dermatol. 2013;40:483-484.

3. Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma with perifollicular mucinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:58-62.

4. Brasanac D, Boricic I. Giant nevus lipomatosus superficialis with multiple folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and dermoid cysts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:84-86.

5. Noh S, Kwon JE, Lee KG, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S185-S187.

6. Plewig G. In discussion of: Leserbrief zu Zheng LQ, Han XC, Huang Y, Li HW. Several acneiform papules and nodules on the neck. diagnosis: folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:824-825.

1. Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma: a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

2. Moriki M, Ito T, Hirakawa S, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma presenting as a subcutaneous nodule on the thigh. J Dermatol. 2013;40:483-484.

3. Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma with perifollicular mucinosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:58-62.

4. Brasanac D, Boricic I. Giant nevus lipomatosus superficialis with multiple folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and dermoid cysts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:84-86.

5. Noh S, Kwon JE, Lee KG, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S185-S187.

6. Plewig G. In discussion of: Leserbrief zu Zheng LQ, Han XC, Huang Y, Li HW. Several acneiform papules and nodules on the neck. diagnosis: folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:824-825.

A 3-year-old girl was referred to our clinic for a lesion on the face that had been present since birth and had enlarged slowly with slight itching. Physical examination revealed a 1.0×1.0-cm, sessile, flesh-colored, sharply demarcated, and dome-shaped papule with a bloody crust. It was firm and slightly painful to palpation. Dilated hair follicle–like orifices and thick central terminal hair were not found. Sebaceous material was not discharged. There was no notable family history or evidence of systemic disease. The lesion was surgically removed for cosmetic reasons and further histopathologic examination was performed.

A Double Dose of Trouble

ANSWER

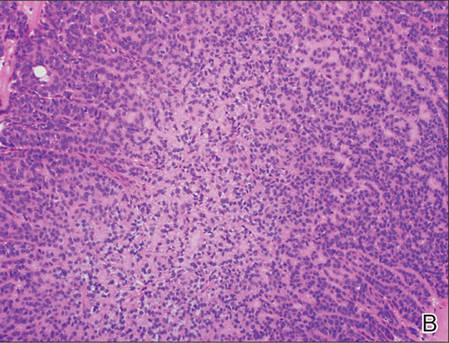

This ECG demonstrates marked sinus bradycardia with a second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Mobitz I). Other findings include left-axis deviation, an old inferior MI, and poor R-wave progression.

Second-degree Mobitz I block is present in a 3:1 pattern of progressive prolongation of the PR interval until the third beat, where there is block in the AV node preventing conduction of the P wave to the ventricles. This is typically caused by progressive fatigue within the AV node until block occurs, then the cycle repeats.

Left-axis deviation is evidenced by a QRS axis of –78°. An old inferior MI is signified by the significant Q waves in leads II, III, and aVF. Finally, poor R-wave progression is demonstrated by small R waves in all of the precordial leads.

This ECG represented a significant change from one obtained three months earlier, during a routine outpatient visit. Careful review of the records at the Alzheimer facility revealed that the patient had received twice his usual dose of propranolol on three consecutive days. His rhythm returned to a baseline sinus rhythm (at 68 beats/min) after his ß-blocker was withheld for two days, and no further intervention was needed.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates marked sinus bradycardia with a second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Mobitz I). Other findings include left-axis deviation, an old inferior MI, and poor R-wave progression.

Second-degree Mobitz I block is present in a 3:1 pattern of progressive prolongation of the PR interval until the third beat, where there is block in the AV node preventing conduction of the P wave to the ventricles. This is typically caused by progressive fatigue within the AV node until block occurs, then the cycle repeats.

Left-axis deviation is evidenced by a QRS axis of –78°. An old inferior MI is signified by the significant Q waves in leads II, III, and aVF. Finally, poor R-wave progression is demonstrated by small R waves in all of the precordial leads.

This ECG represented a significant change from one obtained three months earlier, during a routine outpatient visit. Careful review of the records at the Alzheimer facility revealed that the patient had received twice his usual dose of propranolol on three consecutive days. His rhythm returned to a baseline sinus rhythm (at 68 beats/min) after his ß-blocker was withheld for two days, and no further intervention was needed.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates marked sinus bradycardia with a second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block (Mobitz I). Other findings include left-axis deviation, an old inferior MI, and poor R-wave progression.

Second-degree Mobitz I block is present in a 3:1 pattern of progressive prolongation of the PR interval until the third beat, where there is block in the AV node preventing conduction of the P wave to the ventricles. This is typically caused by progressive fatigue within the AV node until block occurs, then the cycle repeats.

Left-axis deviation is evidenced by a QRS axis of –78°. An old inferior MI is signified by the significant Q waves in leads II, III, and aVF. Finally, poor R-wave progression is demonstrated by small R waves in all of the precordial leads.

This ECG represented a significant change from one obtained three months earlier, during a routine outpatient visit. Careful review of the records at the Alzheimer facility revealed that the patient had received twice his usual dose of propranolol on three consecutive days. His rhythm returned to a baseline sinus rhythm (at 68 beats/min) after his ß-blocker was withheld for two days, and no further intervention was needed.

An 82-year-old man is referred from a nearby Alzheimer care facility following an episode of postural hypotension. While trying to get out of bed, he experienced near-syncope, which was observed by a nurse caring for another patient in the same room. The patient was helped back into bed, and the resident care provider was summoned. A careful examination ruled out any injury sustained when the patient’s knees buckled and he fell to the ground. However, he was found to have profound bradycardia with a pulse of 30 beats/min. Emergency medical services were called, and the patient was transported to your facility for further evaluation. You find the patient to be pleasant but mildly confused. He is in no distress. A review of the limited available records shows that he has had Alzheimer disease for four years; it has been relatively stable, with no recent changes in cognition. His history includes an inferior myocardial infarction (MI) at age 68 and hypertension. The latter has been treated with diuretics and ß-blockers, although the doses have not been changed since his MI. Other remarkable items in the history include hypothyroidism, type 2 diabetes, cholecystectomy, and appendectomy. He has significant osteoarthritis in both knees but does not require a cane or other device to ambulate. The patient is a retired iron worker from the local foundry. He is a widower with two adult children who live remotely and do not visit. He was a heavy drinker in his younger years and smoked one to two packs of cigarettes per day until his MI. He has abstained from alcohol and tobacco since his wife’s death six years ago. His medication list includes a daily aspirin, furosemide, potassium chloride, propranolol, and levothyroxine. He is said to be allergic to penicillin, but there is no record of him ever receiving it. The review of systems is difficult to obtain due to the patient’s confusion. He has not had any recent infectious illnesses, according to the accompanying nurse from the Alzheimer facility. Physical exam reveals a disheveled but otherwise pleasant man. He can remember only one out of three words when asked to recite immediately after hearing them. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 86/48 mm Hg; pulse, 40 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.4°F. His weight is 163 lb and his height, 66 in. The patient wears corrective lenses and hearing aids, but the batteries in the latter are dead. Regardless, he can hear you if you speak loudly. Pertinent physical findings include scattered crackles in both lung bases, a regularly irregular slow heart rate, a grade III/VI systolic murmur that radiates to the neck, and well-healed surgical scars on the abdomen consistent with the surgeries described in the history. There appear to be no gross focal neurologic findings. An ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 38 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 78 ms; QT/QTc interval, 434/345 ms; P axis, 25°; R axis, –78°; and T axis, 13°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

When Trauma Changes the Picture

Answer

The radiograph has several findings. First, there are multiple fractures along the left lateral ribs. Second, there is a small left apical pneumothorax. Most significant, though, is an elevated left hemidiaphragm. There appears to be stomach or possibly bowel protruding into it.

Although a large hiatal hernia could yield similar findings, in the setting of trauma, one must be concerned about a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Subsequent CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis confirmed a defect within the diaphragm, with a significant portion of the stomach herniating into the left chest.

Surgical consultation was obtained. The patient was admitted and ultimately underwent surgical intervention to repair the problem.

Answer

The radiograph has several findings. First, there are multiple fractures along the left lateral ribs. Second, there is a small left apical pneumothorax. Most significant, though, is an elevated left hemidiaphragm. There appears to be stomach or possibly bowel protruding into it.

Although a large hiatal hernia could yield similar findings, in the setting of trauma, one must be concerned about a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Subsequent CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis confirmed a defect within the diaphragm, with a significant portion of the stomach herniating into the left chest.

Surgical consultation was obtained. The patient was admitted and ultimately underwent surgical intervention to repair the problem.

Answer

The radiograph has several findings. First, there are multiple fractures along the left lateral ribs. Second, there is a small left apical pneumothorax. Most significant, though, is an elevated left hemidiaphragm. There appears to be stomach or possibly bowel protruding into it.

Although a large hiatal hernia could yield similar findings, in the setting of trauma, one must be concerned about a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Subsequent CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis confirmed a defect within the diaphragm, with a significant portion of the stomach herniating into the left chest.

Surgical consultation was obtained. The patient was admitted and ultimately underwent surgical intervention to repair the problem.

A 75-year-old man is brought to your emergency center following a fall from his attic. He slipped and fell approximately 10 feet, landing on his left side. He did not hit his head and denies any loss of consciousness. His primary complaint is left-side chest wall pain. Medical history is significant for hypertension, diabetes, reflux, and atrial fibrillation. On primary survey, you note an elderly male who is somewhat uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. His vital signs are stable; O2 saturation is 98% on room air. The patient exhibits moderate tenderness along the anterior lateral aspect of his chest, as well as mild generalized tenderness in his abdomen. Good inspiratory effort is limited secondary to his pain. While you enter orders into the computer, a portable chest radiograph is obtained. What is your impression?

Man Is in Thick of Skin Problem

ANSWER

The correct answer is palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (PPK; choice “c”). As a category, it includes many conditions that are characterized by a heterogeneous thickening of the palms and soles, although each has distinct features.

Psoriasis (choice “a”) can present in somewhat similar fashion. However, it rarely appears so early in life and almost never involves such uniform hyperkeratosis.

Xerosis (choice “b”) merely means dry skin—a common enough problem, but one that does not involve such uniform and deep hyperkeratosis. It is almost never congenital.

Occult cancers (eg, GI, breast) can occasionally trigger a hyperkeratotic “perineoplastic” reaction (choice “d”) in the palms, soles, and other areas. However, it is acquired relatively late in life.

DISCUSSION

PPK is a relatively common problem, especially in those of northern European ancestry. The incidence in Northern Ireland, for example, is 4.4/100,000. In its more severe forms, such as this case, it can be debilitating.

Categorization of this extraordinarily diverse group of disorders is a challenge, to say the least. For purposes of this discussion, let’s start with this patient’s condition and then clarify its place in the panoply of hyperkeratotic disorders.

Our patient has one of the more common forms of diffuse PPK, generically called nonepidermolytic PPK, which presents with a waxy, uniform yellowed hyperkeratosis confined to the palms and soles. The old eponymic term for it was Unna-Thost disorder, named for the Viennese and Norwegian dermatologists who first described it late in the 19th century. A more modern term is tylosis, but many variations exist. This particular form is inherited in autosomal dominant fashion, but other forms of PPK can be transmitted by autosomal recessive or even X-linked genes.

Other types include focal (thick calluses over points of friction, especially on the feet) versions that can present in linear configuration and punctate forms with deep calluses on palms and soles that can be discrete or widespread, with lesions that range in size from pinpoint (“speculated”) to pea-sized.