User login

Postoperative Patient Suddenly Worsens

ANSWER

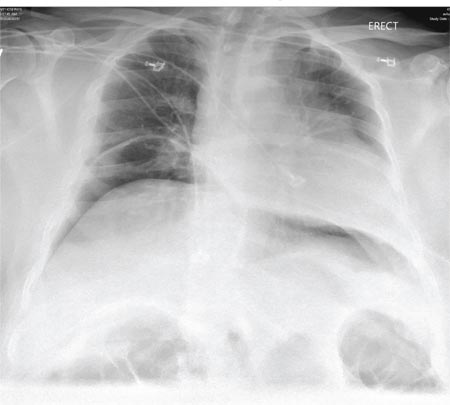

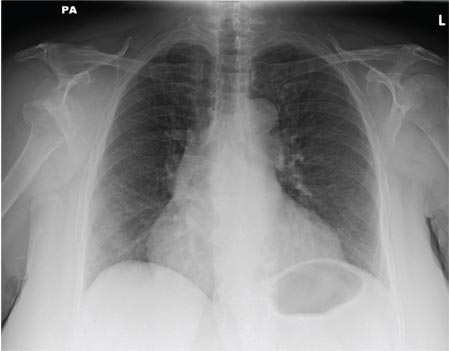

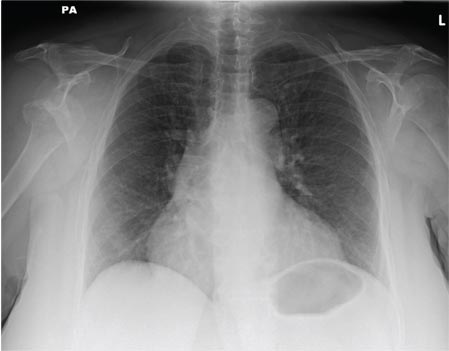

The radiograph demonstrates bilateral elevated diaphragm with a moderate amount of visible free air. With no history of recent abdominal procedures, the primary concern is a perforated viscus.

Urgent surgical consultation, as well as CT of the abdomen and pelvis, was obtained. The imaging confirmed the free air but provided no clear etiology. The patient underwent emergent laparotomy later that day and was found to have a perforated colon.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates bilateral elevated diaphragm with a moderate amount of visible free air. With no history of recent abdominal procedures, the primary concern is a perforated viscus.

Urgent surgical consultation, as well as CT of the abdomen and pelvis, was obtained. The imaging confirmed the free air but provided no clear etiology. The patient underwent emergent laparotomy later that day and was found to have a perforated colon.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates bilateral elevated diaphragm with a moderate amount of visible free air. With no history of recent abdominal procedures, the primary concern is a perforated viscus.

Urgent surgical consultation, as well as CT of the abdomen and pelvis, was obtained. The imaging confirmed the free air but provided no clear etiology. The patient underwent emergent laparotomy later that day and was found to have a perforated colon.

A 55-year-old man undergoes an elective craniotomy for tumor resection, with uneventful preoperative and intraoperative stages. Immediately postoperative, however, he experiences seizures. Noncontrast CT of the head is negative except for postoperative changes. The patient is placed in the ICU for close monitoring. He is slowly improving when, on the fifth postoperative day, tachypnea and dyspnea are observed. The patient is afebrile. His blood pressure is 116/70 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 30 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 98%. A stat portable chest radiograph is obtained. What is your impression?

Leg Swelling Accompanied by Weight Gain

In the past two weeks, a 59-year-old postmenopausal woman has noticed swelling in her legs and a 10-lb weight gain. For the past three days, she has also had a vague, aching pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant, which surprises her, since her gall bladder was removed long ago. There is no prior history of chest pain, dyspnea, or systemic hypertension.

The patient does have a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, palpitations, and pulmonary hypertension. She is chronically obese and has hypothyroidism. Surgical history is significant for cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and left breast lumpectomy with axillary node dissection.

Her job at a local factory, assembling components for pressure washer pumps, requires her to sit for extended periods. She smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day, a habit that began when she was 16. She drinks one or two beers daily and admits she has “many more” on the weekends. She has used marijuana in the recent past but not in the past month. She denies use of any other illicit drugs or homeopathic medications.

Her medication list includes levothyroxine sodium and ibuprofen. She says she’s “supposed to be taking some kind of heart medication” but hasn’t taken it for several months (and cannot remember the name). It was prescribed for her when she was on vacation in the Florida Keys and experienced similar symptoms. She sheepishly admits to trying her husband’s sildenafil, as she’s been told it works for pulmonary hypertension. She is allergic to sulfa and tetracycline.

Review of systems is remarkable for bilateral hip and ankle pain, which she attributes to her weight. She has had no change in bowel or bladder function. The remainder of the review is unremarkable.

Physical exam reveals a weight of 297 lb and height of 5’6”. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 128/88 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; temperature, 98.2°F; and O2 saturation, 98.2%.

She is morbidly obese and in no distress. Pertinent physical findings include elevated jugular venous return, bilateral rales in both lung bases, a soft, early diastolic murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border, and a regular rate and rhythm. She also has mild tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper abdominal quadrant. Her lower extremities demonstrate 3+ pitting edema to the level of the knees bilaterally. There are no skin lesions, and the neurologic exam is grossly intact.

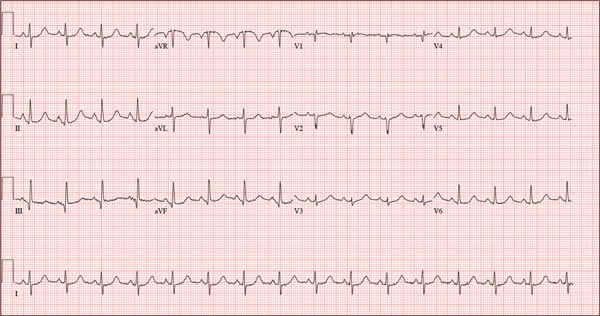

As part of her workup, you order an ECG, which reveals a ventricular rate of 94 beats/min; PR interval, 130 ms; QRS duration, 76 ms; QT/QTc interval, 394/492 ms; P axis, 50°; R axis, 80°; and T axis, 47°. What is your interpretation?

ANSWER

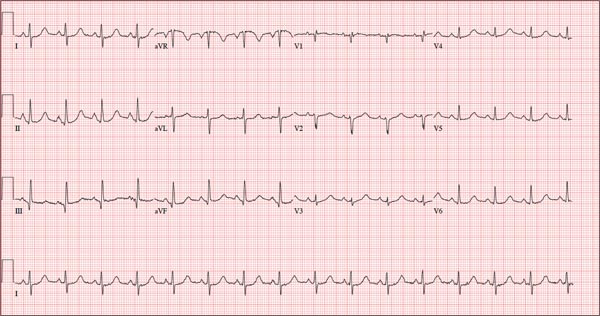

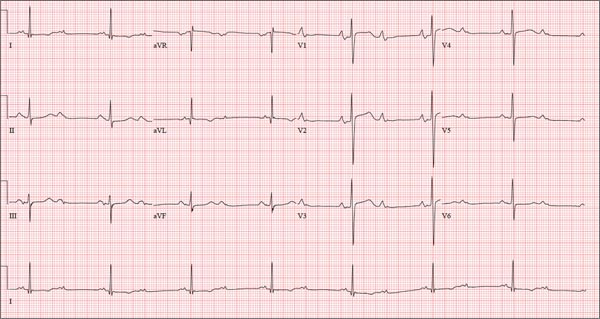

Pertinent findings on this ECG include normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, and a prolonged QT interval. Criteria for right atrial enlargement include P waves > 2.5 mm in leads II, III, and aVF and > 1.5 mm in leads V1 and V2. A prolonged QT interval is evidenced by a QTc > 470 ms using Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT divided by the square root of the RR interval).

The patient’s symptoms and ECG finding of right atrial enlargement coincide with pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure. The prolonged QT interval may be due to her history of hypothyroidism; however, this has not been confirmed.

In the past two weeks, a 59-year-old postmenopausal woman has noticed swelling in her legs and a 10-lb weight gain. For the past three days, she has also had a vague, aching pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant, which surprises her, since her gall bladder was removed long ago. There is no prior history of chest pain, dyspnea, or systemic hypertension.

The patient does have a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, palpitations, and pulmonary hypertension. She is chronically obese and has hypothyroidism. Surgical history is significant for cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and left breast lumpectomy with axillary node dissection.

Her job at a local factory, assembling components for pressure washer pumps, requires her to sit for extended periods. She smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day, a habit that began when she was 16. She drinks one or two beers daily and admits she has “many more” on the weekends. She has used marijuana in the recent past but not in the past month. She denies use of any other illicit drugs or homeopathic medications.

Her medication list includes levothyroxine sodium and ibuprofen. She says she’s “supposed to be taking some kind of heart medication” but hasn’t taken it for several months (and cannot remember the name). It was prescribed for her when she was on vacation in the Florida Keys and experienced similar symptoms. She sheepishly admits to trying her husband’s sildenafil, as she’s been told it works for pulmonary hypertension. She is allergic to sulfa and tetracycline.

Review of systems is remarkable for bilateral hip and ankle pain, which she attributes to her weight. She has had no change in bowel or bladder function. The remainder of the review is unremarkable.

Physical exam reveals a weight of 297 lb and height of 5’6”. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 128/88 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; temperature, 98.2°F; and O2 saturation, 98.2%.

She is morbidly obese and in no distress. Pertinent physical findings include elevated jugular venous return, bilateral rales in both lung bases, a soft, early diastolic murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border, and a regular rate and rhythm. She also has mild tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper abdominal quadrant. Her lower extremities demonstrate 3+ pitting edema to the level of the knees bilaterally. There are no skin lesions, and the neurologic exam is grossly intact.

As part of her workup, you order an ECG, which reveals a ventricular rate of 94 beats/min; PR interval, 130 ms; QRS duration, 76 ms; QT/QTc interval, 394/492 ms; P axis, 50°; R axis, 80°; and T axis, 47°. What is your interpretation?

ANSWER

Pertinent findings on this ECG include normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, and a prolonged QT interval. Criteria for right atrial enlargement include P waves > 2.5 mm in leads II, III, and aVF and > 1.5 mm in leads V1 and V2. A prolonged QT interval is evidenced by a QTc > 470 ms using Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT divided by the square root of the RR interval).

The patient’s symptoms and ECG finding of right atrial enlargement coincide with pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure. The prolonged QT interval may be due to her history of hypothyroidism; however, this has not been confirmed.

In the past two weeks, a 59-year-old postmenopausal woman has noticed swelling in her legs and a 10-lb weight gain. For the past three days, she has also had a vague, aching pain in the right upper abdominal quadrant, which surprises her, since her gall bladder was removed long ago. There is no prior history of chest pain, dyspnea, or systemic hypertension.

The patient does have a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, palpitations, and pulmonary hypertension. She is chronically obese and has hypothyroidism. Surgical history is significant for cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and left breast lumpectomy with axillary node dissection.

Her job at a local factory, assembling components for pressure washer pumps, requires her to sit for extended periods. She smokes 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day, a habit that began when she was 16. She drinks one or two beers daily and admits she has “many more” on the weekends. She has used marijuana in the recent past but not in the past month. She denies use of any other illicit drugs or homeopathic medications.

Her medication list includes levothyroxine sodium and ibuprofen. She says she’s “supposed to be taking some kind of heart medication” but hasn’t taken it for several months (and cannot remember the name). It was prescribed for her when she was on vacation in the Florida Keys and experienced similar symptoms. She sheepishly admits to trying her husband’s sildenafil, as she’s been told it works for pulmonary hypertension. She is allergic to sulfa and tetracycline.

Review of systems is remarkable for bilateral hip and ankle pain, which she attributes to her weight. She has had no change in bowel or bladder function. The remainder of the review is unremarkable.

Physical exam reveals a weight of 297 lb and height of 5’6”. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 128/88 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; temperature, 98.2°F; and O2 saturation, 98.2%.

She is morbidly obese and in no distress. Pertinent physical findings include elevated jugular venous return, bilateral rales in both lung bases, a soft, early diastolic murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border, and a regular rate and rhythm. She also has mild tenderness to deep palpation in the right upper abdominal quadrant. Her lower extremities demonstrate 3+ pitting edema to the level of the knees bilaterally. There are no skin lesions, and the neurologic exam is grossly intact.

As part of her workup, you order an ECG, which reveals a ventricular rate of 94 beats/min; PR interval, 130 ms; QRS duration, 76 ms; QT/QTc interval, 394/492 ms; P axis, 50°; R axis, 80°; and T axis, 47°. What is your interpretation?

ANSWER

Pertinent findings on this ECG include normal sinus rhythm, right atrial enlargement, and a prolonged QT interval. Criteria for right atrial enlargement include P waves > 2.5 mm in leads II, III, and aVF and > 1.5 mm in leads V1 and V2. A prolonged QT interval is evidenced by a QTc > 470 ms using Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT divided by the square root of the RR interval).

The patient’s symptoms and ECG finding of right atrial enlargement coincide with pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure. The prolonged QT interval may be due to her history of hypothyroidism; however, this has not been confirmed.

Those symptoms first appeared two weeks ago. Now, this woman also has abdominal pain. What does an ECG add to the clinical picture?

As Problem Spreads, Man Seeks Help

ANSWER

The correct answer is Schamberg disease (choice “b”), a benign form of capillaritis; see Discussion for more information.

Scurvy patients can present with ecchymosis (among other findings that were missing in this case). But scurvy (choice “a”) is rare, and by the time the disease is evident, the patient is typically quite ill.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “c”) can manifest as purpuric annular lesions. However, these would be unlikely to take the distributive pattern seen in this case, and they usually have an atrophic surface.

Thrombocytopenia (choice “d”) and other coagulopathies, although rightly considered, would probably manifest in other ways as well (ie, not just cutaneously).

Continue for the discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Schamberg disease is typical of a whole class of conditions in which red blood cells (RBCs) are extravasated from slightly damaged capillaries. This results in nonblanchable purpura and subsequent hemosiderin staining caused by phagocytosis of the RBCs by macrophages. Clinically, this family of diseases present as cayenne pepper–colored macules, most of which are annular in configuration.

Schamberg is, by far, the most common of these conditions. This presentation was typical: manifestation on the knees and ankles followed by upward spread (hence the condition’s other name, progressive pigmentary purpura). Usually resolving on their own within months, these lesions are almost always asymptomatic—but nonetheless alarming to the patient.

Other equally benign, self-limited forms of capillaritis include those in which lesions are pruritic (eg, purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis) or lichenoid (purpura of Gougerot-Blum). Another example is lichen aureus, in which only one or two lesions, more gold than brown, appear on the legs of younger patients.

There are many theories as to these conditions’ cause, the most common of which is increased intravascular pressure secondary to dependence. However, if this were so, we’d likely see a great deal more cases, since many patients have problems related to venous insufficiency.

In some cases, skin biopsy (usually 4-mm punch) is necessary to rule out more serious diseases, such as an early form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. When a coagulopathy is suspected, blood work is necessary to confirm or rule out the diagnosis. In this case, there was no reason to suspect coagulopathy (or scurvy), since no other signs were seen.

This patient was educated about his diagnosis and provided Web-based resources he could consult. Various treatments—topical steroids, increased vitamin C intake, and increased exposure to UV light—have been tried but with disappointing results.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Schamberg disease (choice “b”), a benign form of capillaritis; see Discussion for more information.

Scurvy patients can present with ecchymosis (among other findings that were missing in this case). But scurvy (choice “a”) is rare, and by the time the disease is evident, the patient is typically quite ill.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “c”) can manifest as purpuric annular lesions. However, these would be unlikely to take the distributive pattern seen in this case, and they usually have an atrophic surface.

Thrombocytopenia (choice “d”) and other coagulopathies, although rightly considered, would probably manifest in other ways as well (ie, not just cutaneously).

Continue for the discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Schamberg disease is typical of a whole class of conditions in which red blood cells (RBCs) are extravasated from slightly damaged capillaries. This results in nonblanchable purpura and subsequent hemosiderin staining caused by phagocytosis of the RBCs by macrophages. Clinically, this family of diseases present as cayenne pepper–colored macules, most of which are annular in configuration.

Schamberg is, by far, the most common of these conditions. This presentation was typical: manifestation on the knees and ankles followed by upward spread (hence the condition’s other name, progressive pigmentary purpura). Usually resolving on their own within months, these lesions are almost always asymptomatic—but nonetheless alarming to the patient.

Other equally benign, self-limited forms of capillaritis include those in which lesions are pruritic (eg, purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis) or lichenoid (purpura of Gougerot-Blum). Another example is lichen aureus, in which only one or two lesions, more gold than brown, appear on the legs of younger patients.

There are many theories as to these conditions’ cause, the most common of which is increased intravascular pressure secondary to dependence. However, if this were so, we’d likely see a great deal more cases, since many patients have problems related to venous insufficiency.

In some cases, skin biopsy (usually 4-mm punch) is necessary to rule out more serious diseases, such as an early form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. When a coagulopathy is suspected, blood work is necessary to confirm or rule out the diagnosis. In this case, there was no reason to suspect coagulopathy (or scurvy), since no other signs were seen.

This patient was educated about his diagnosis and provided Web-based resources he could consult. Various treatments—topical steroids, increased vitamin C intake, and increased exposure to UV light—have been tried but with disappointing results.

ANSWER

The correct answer is Schamberg disease (choice “b”), a benign form of capillaritis; see Discussion for more information.

Scurvy patients can present with ecchymosis (among other findings that were missing in this case). But scurvy (choice “a”) is rare, and by the time the disease is evident, the patient is typically quite ill.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (choice “c”) can manifest as purpuric annular lesions. However, these would be unlikely to take the distributive pattern seen in this case, and they usually have an atrophic surface.

Thrombocytopenia (choice “d”) and other coagulopathies, although rightly considered, would probably manifest in other ways as well (ie, not just cutaneously).

Continue for the discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Schamberg disease is typical of a whole class of conditions in which red blood cells (RBCs) are extravasated from slightly damaged capillaries. This results in nonblanchable purpura and subsequent hemosiderin staining caused by phagocytosis of the RBCs by macrophages. Clinically, this family of diseases present as cayenne pepper–colored macules, most of which are annular in configuration.

Schamberg is, by far, the most common of these conditions. This presentation was typical: manifestation on the knees and ankles followed by upward spread (hence the condition’s other name, progressive pigmentary purpura). Usually resolving on their own within months, these lesions are almost always asymptomatic—but nonetheless alarming to the patient.

Other equally benign, self-limited forms of capillaritis include those in which lesions are pruritic (eg, purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis) or lichenoid (purpura of Gougerot-Blum). Another example is lichen aureus, in which only one or two lesions, more gold than brown, appear on the legs of younger patients.

There are many theories as to these conditions’ cause, the most common of which is increased intravascular pressure secondary to dependence. However, if this were so, we’d likely see a great deal more cases, since many patients have problems related to venous insufficiency.

In some cases, skin biopsy (usually 4-mm punch) is necessary to rule out more serious diseases, such as an early form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. When a coagulopathy is suspected, blood work is necessary to confirm or rule out the diagnosis. In this case, there was no reason to suspect coagulopathy (or scurvy), since no other signs were seen.

This patient was educated about his diagnosis and provided Web-based resources he could consult. Various treatments—topical steroids, increased vitamin C intake, and increased exposure to UV light—have been tried but with disappointing results.

For several months, a 30-year-old man has had an asymptomatic rash on his legs. The lesions first appeared on his lower legs and ankles; over the subsequent months, they have spread upward. Now, the rash reaches to just below his knees. During this time, he has had two bouts of strep throat, both adequately treated. He denies any other skin problems and has no relevant family history. The patient denies alcohol or drug abuse and is not taking any prescription medications. Prior to referral to dermatology, he was seen in two urgent care clinics; at one, he received a diagnosis of fungal infection and at the other, of “vitamin deficiency.” He was given a month-long course of terbinafine (250 mg/d) that produced no change in his rash. He achieved the same (non)result from an increased intake of vitamins. Examination reveals annular reddish brown macules, measuring 1 to 3 cm, sparsely distributed from the knees to just above the ankles on both legs. The lesions are a bit more densely arrayed on the anterior legs. There is no palpable component to any of them and no discernable surface scale. Digital pressure fails to blanch the lesions. The hairs and follicles on the patient’s legs appear normal. There are no notable skin changes elsewhere, and the patient is alert, oriented, and in no distress.

Friable Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Spindle Cell Malignant Melanoma With Perineural Invasion

The incidence of melanoma has steadily increased in the United States since the 1930s when the incidence was reported at 1.0 per 100,000.1 In 1973 melanoma incidence was 6.8 per 100,000, and by 2007 the rate increased to 20.1 per 100,000.2 The American Cancer Society projects 73,870 new cases of melanoma in 2015, with melanoma as the fifth most common cancer in males and the seventh most common in females.3 Melanoma-related deaths are projected to be 9940. The lifetime probability of developing melanoma is 1 in 34 for males and 1 in 53 for females. Twice as many males are estimated to have melanoma-related deaths compared to females. The 5-year relative survival rate is 93% for white individuals and 75% for black individuals.3

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare variant of melanoma that was originally described by Conley et al4 in 1971. The lesion represents 2% to 4% of all melanomas and presents in older patients on sun-exposed skin as a pink or variably pigmented nodule measuring an average of 2 cm.5 Males are affected more than females, and prominent neural invasion is present in 30% to 100% of cases.6-10 Neural invasion can result in nerve palsies and/or dysesthesia. Because half of these lesions are amelanotic, they are often clinically misdiagnosed prior to biopsy.11

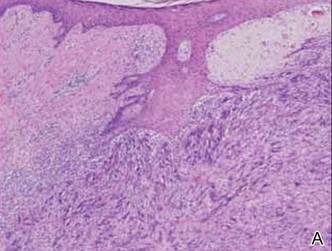

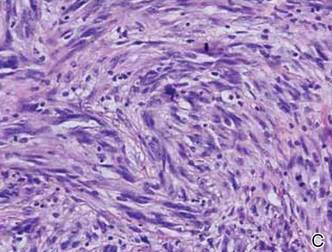

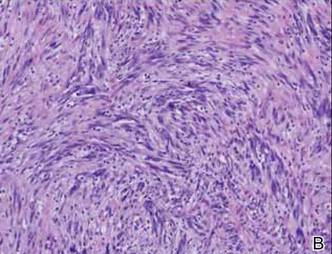

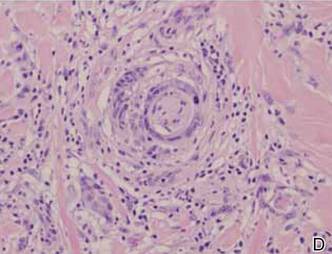

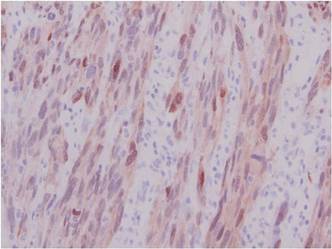

Histopathologically, these lesions can be quite challenging. Spindle cell melanoma histologically is an intradermal lesion composed of spindle cells distributed in bundles, fascicles, or nests, or singly between collagen fibers of the dermis. Other spindle tumors such as spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, angiosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma have a similar presentation with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The diagnostic process for spindle cell tumors is greatly aided by immunohistologic analysis. Spindle cell melanoma usually shows immunoreactivity with S-100. Human melanoma black 45, CD57, and neuron-specific enolase usually do not stain, and CD68 has been demonstrated in a minority of cases.

The initial biopsy specimen in our case displayed a dense dermal atypical spindle cell proliferation with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The differential diagnosis of the proliferation included desmoplastic melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Immunostains were used to further study the lesional biopsy. Cytokeratin 34bE12, CK5/6, cerium ammonium molybdate 5.2, CK7, epithelial membrane antigen, CK18, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, S-100, Melan-A, human melanoma black 45, smooth muscle actin, desmin, CD68, CD34, CD10, and p63 were studied. The atypical dermal spindle cells were positive for S-100. S-100 and Melan-A highlighted an increased number of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. Other markers were negative.

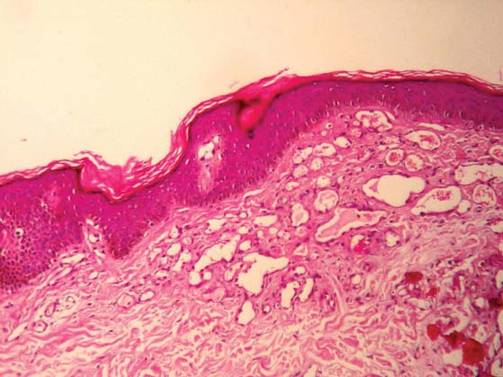

A 1.0-cm wide excision to fascia was performed. Routine hematoxylin and eosin stain showed atypical dermal spindle cells with perineural invasion (Figure 1). The malignant spindle cells were S-100 positive (Figure 2). The spindle cells were negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, CK5/6, p63, Melan-A, A103, microphthalmia, and tyrosinase. These findings confirm melanoma of the spindle cell type.

|

The lesion was a Clark level V melanoma with a Breslow thickness of at least 12 mm. Perineural invasion was noted and the mitotic index was 7 cells/mm2. Vascular and lymphatic invasion was negative and ulceration was present. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were brisk, resulting in a pathologic staging of pT4NXMX.

On initial histologic study with hematoxylin and eosin stain, spindle cell melanoma lesions tend to be generally quite thick. Manganoni et al12 reported in their series a Breslow thickness ranging from 2.1 to 12 mm with a mean of 5.8 mm.

Treatment in our case involved a second wide incision to fascia with an additional 2-cm margin. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) remains undefined. Patients with spindle cell melanoma have a lower frequency of positive sentinel lymph nodes than nondesmoplastic melanomas.13 As such, the need to perform SLNB has not been determined.13-15 Our patient had a history of breast cancer. The lesion appeared on the left side of the back and she pre-viously had a complete axillary lymphadenectomy on the left axillae. She declined SLNB. A systematic workup by the oncology service was negative. Continued follow-up has revealed no recurrent disease and recent workup was negative for metastatic disease.

Many studies report the increased incidence of local recurrence after excision for spindle cell melanoma as compared to non–spindle cell melanoma,16-18 which is likely related to perineural invasion as in our patient.

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare tumor that is often amelanotic and difficult to diagnose clinically. Routine hematoxylin and eosin staining shows a dermal spindle cell tumor. Immunohistochemical study is of great aid in defining the tumor. The clinician and pathologist must work together to correctly diagnose and treat this lesion.

1. Mikkilineni R, Weinstock MA. Epidemiology. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds. Atlas of Clinical Oncology: Skin Cancer. London, England: BC Decker; 2001:1-15.

2. Rigel D. Epidemiology of melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:204-209.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

4. Conley J, Lattes R, Orr W. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma (a rare variant of malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1971;28:914-936.

5. Repertinger SK, Teruya B, Sarma DP. Common spindle cell malignant neoplasms of the skin: differential diagnosis and review of the literature. Internet J Dermatol. 2009;7. https://ispub.com/IJD/7/2/11747. Accessed February 10, 2015.

6. Chang PC, Fischbein NJ, McCalmont TH, et al. Perineural spread of malignant melanoma of the head and neck: clinical and imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradial. 2004;25:5-11.

7. Cruz J, Reis-Filho JS, Lopes JM. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor-like primary cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:218-220.

8. Tsao H, Sober AJ, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:45-47.

9. Kossard S, Doherty E, Murray E. Neurotropic melanoma. a variant of desmoplastic melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1997;7:907-912.

10. Bruijn JA, Salasche S, Sober AJ, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: clinicopathologic aspects of six cases. Dermatology. 1992;185:3-8.

11. Jesitus J. Desmoplastic melanoma. Dermatology Times. March 2009:1-2.

12. Manganoni AM, Farisoglio C, Bassissi S, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: report of 5 cases. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009;2009:679010.

13. Gyorki DE, Busam K, Panageas K, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with desmoplastic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:403-407.

14. Livestro DP, Muzikansky A, Kaine EM, et al. of desmoplastic melanoma: a case-control comparison with other melanomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6739-6746.

15. Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Prieto VG, et al. Assessment of the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy for primary cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer. 2006;106:900-906.

16. Smithers HM, McLeod GR, Little JH. Desmoplastic melanoma: patterns of recurrence. World J Surg. 1992;16:186-190.

17. McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA, Palmer AA. Desmoplastic melanoma: a diagnostic trap for the unwary. Pathology. 2004;36:445-451.

18. Bruijn JA, Mihm MC Jr, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic melanoma. Histopathology. 1992;20:197-205.

The Diagnosis: Spindle Cell Malignant Melanoma With Perineural Invasion

The incidence of melanoma has steadily increased in the United States since the 1930s when the incidence was reported at 1.0 per 100,000.1 In 1973 melanoma incidence was 6.8 per 100,000, and by 2007 the rate increased to 20.1 per 100,000.2 The American Cancer Society projects 73,870 new cases of melanoma in 2015, with melanoma as the fifth most common cancer in males and the seventh most common in females.3 Melanoma-related deaths are projected to be 9940. The lifetime probability of developing melanoma is 1 in 34 for males and 1 in 53 for females. Twice as many males are estimated to have melanoma-related deaths compared to females. The 5-year relative survival rate is 93% for white individuals and 75% for black individuals.3

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare variant of melanoma that was originally described by Conley et al4 in 1971. The lesion represents 2% to 4% of all melanomas and presents in older patients on sun-exposed skin as a pink or variably pigmented nodule measuring an average of 2 cm.5 Males are affected more than females, and prominent neural invasion is present in 30% to 100% of cases.6-10 Neural invasion can result in nerve palsies and/or dysesthesia. Because half of these lesions are amelanotic, they are often clinically misdiagnosed prior to biopsy.11

Histopathologically, these lesions can be quite challenging. Spindle cell melanoma histologically is an intradermal lesion composed of spindle cells distributed in bundles, fascicles, or nests, or singly between collagen fibers of the dermis. Other spindle tumors such as spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, angiosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma have a similar presentation with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The diagnostic process for spindle cell tumors is greatly aided by immunohistologic analysis. Spindle cell melanoma usually shows immunoreactivity with S-100. Human melanoma black 45, CD57, and neuron-specific enolase usually do not stain, and CD68 has been demonstrated in a minority of cases.

The initial biopsy specimen in our case displayed a dense dermal atypical spindle cell proliferation with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The differential diagnosis of the proliferation included desmoplastic melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Immunostains were used to further study the lesional biopsy. Cytokeratin 34bE12, CK5/6, cerium ammonium molybdate 5.2, CK7, epithelial membrane antigen, CK18, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, S-100, Melan-A, human melanoma black 45, smooth muscle actin, desmin, CD68, CD34, CD10, and p63 were studied. The atypical dermal spindle cells were positive for S-100. S-100 and Melan-A highlighted an increased number of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. Other markers were negative.

A 1.0-cm wide excision to fascia was performed. Routine hematoxylin and eosin stain showed atypical dermal spindle cells with perineural invasion (Figure 1). The malignant spindle cells were S-100 positive (Figure 2). The spindle cells were negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, CK5/6, p63, Melan-A, A103, microphthalmia, and tyrosinase. These findings confirm melanoma of the spindle cell type.

|

The lesion was a Clark level V melanoma with a Breslow thickness of at least 12 mm. Perineural invasion was noted and the mitotic index was 7 cells/mm2. Vascular and lymphatic invasion was negative and ulceration was present. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were brisk, resulting in a pathologic staging of pT4NXMX.

On initial histologic study with hematoxylin and eosin stain, spindle cell melanoma lesions tend to be generally quite thick. Manganoni et al12 reported in their series a Breslow thickness ranging from 2.1 to 12 mm with a mean of 5.8 mm.

Treatment in our case involved a second wide incision to fascia with an additional 2-cm margin. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) remains undefined. Patients with spindle cell melanoma have a lower frequency of positive sentinel lymph nodes than nondesmoplastic melanomas.13 As such, the need to perform SLNB has not been determined.13-15 Our patient had a history of breast cancer. The lesion appeared on the left side of the back and she pre-viously had a complete axillary lymphadenectomy on the left axillae. She declined SLNB. A systematic workup by the oncology service was negative. Continued follow-up has revealed no recurrent disease and recent workup was negative for metastatic disease.

Many studies report the increased incidence of local recurrence after excision for spindle cell melanoma as compared to non–spindle cell melanoma,16-18 which is likely related to perineural invasion as in our patient.

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare tumor that is often amelanotic and difficult to diagnose clinically. Routine hematoxylin and eosin staining shows a dermal spindle cell tumor. Immunohistochemical study is of great aid in defining the tumor. The clinician and pathologist must work together to correctly diagnose and treat this lesion.

The Diagnosis: Spindle Cell Malignant Melanoma With Perineural Invasion

The incidence of melanoma has steadily increased in the United States since the 1930s when the incidence was reported at 1.0 per 100,000.1 In 1973 melanoma incidence was 6.8 per 100,000, and by 2007 the rate increased to 20.1 per 100,000.2 The American Cancer Society projects 73,870 new cases of melanoma in 2015, with melanoma as the fifth most common cancer in males and the seventh most common in females.3 Melanoma-related deaths are projected to be 9940. The lifetime probability of developing melanoma is 1 in 34 for males and 1 in 53 for females. Twice as many males are estimated to have melanoma-related deaths compared to females. The 5-year relative survival rate is 93% for white individuals and 75% for black individuals.3

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare variant of melanoma that was originally described by Conley et al4 in 1971. The lesion represents 2% to 4% of all melanomas and presents in older patients on sun-exposed skin as a pink or variably pigmented nodule measuring an average of 2 cm.5 Males are affected more than females, and prominent neural invasion is present in 30% to 100% of cases.6-10 Neural invasion can result in nerve palsies and/or dysesthesia. Because half of these lesions are amelanotic, they are often clinically misdiagnosed prior to biopsy.11

Histopathologically, these lesions can be quite challenging. Spindle cell melanoma histologically is an intradermal lesion composed of spindle cells distributed in bundles, fascicles, or nests, or singly between collagen fibers of the dermis. Other spindle tumors such as spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, atypical fibroxanthoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, angiosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma have a similar presentation with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The diagnostic process for spindle cell tumors is greatly aided by immunohistologic analysis. Spindle cell melanoma usually shows immunoreactivity with S-100. Human melanoma black 45, CD57, and neuron-specific enolase usually do not stain, and CD68 has been demonstrated in a minority of cases.

The initial biopsy specimen in our case displayed a dense dermal atypical spindle cell proliferation with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The differential diagnosis of the proliferation included desmoplastic melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and atypical fibroxanthoma. Immunostains were used to further study the lesional biopsy. Cytokeratin 34bE12, CK5/6, cerium ammonium molybdate 5.2, CK7, epithelial membrane antigen, CK18, high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, S-100, Melan-A, human melanoma black 45, smooth muscle actin, desmin, CD68, CD34, CD10, and p63 were studied. The atypical dermal spindle cells were positive for S-100. S-100 and Melan-A highlighted an increased number of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction. Other markers were negative.

A 1.0-cm wide excision to fascia was performed. Routine hematoxylin and eosin stain showed atypical dermal spindle cells with perineural invasion (Figure 1). The malignant spindle cells were S-100 positive (Figure 2). The spindle cells were negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, CK5/6, p63, Melan-A, A103, microphthalmia, and tyrosinase. These findings confirm melanoma of the spindle cell type.

|

The lesion was a Clark level V melanoma with a Breslow thickness of at least 12 mm. Perineural invasion was noted and the mitotic index was 7 cells/mm2. Vascular and lymphatic invasion was negative and ulceration was present. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were brisk, resulting in a pathologic staging of pT4NXMX.

On initial histologic study with hematoxylin and eosin stain, spindle cell melanoma lesions tend to be generally quite thick. Manganoni et al12 reported in their series a Breslow thickness ranging from 2.1 to 12 mm with a mean of 5.8 mm.

Treatment in our case involved a second wide incision to fascia with an additional 2-cm margin. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) remains undefined. Patients with spindle cell melanoma have a lower frequency of positive sentinel lymph nodes than nondesmoplastic melanomas.13 As such, the need to perform SLNB has not been determined.13-15 Our patient had a history of breast cancer. The lesion appeared on the left side of the back and she pre-viously had a complete axillary lymphadenectomy on the left axillae. She declined SLNB. A systematic workup by the oncology service was negative. Continued follow-up has revealed no recurrent disease and recent workup was negative for metastatic disease.

Many studies report the increased incidence of local recurrence after excision for spindle cell melanoma as compared to non–spindle cell melanoma,16-18 which is likely related to perineural invasion as in our patient.

Spindle cell melanoma is a rare tumor that is often amelanotic and difficult to diagnose clinically. Routine hematoxylin and eosin staining shows a dermal spindle cell tumor. Immunohistochemical study is of great aid in defining the tumor. The clinician and pathologist must work together to correctly diagnose and treat this lesion.

1. Mikkilineni R, Weinstock MA. Epidemiology. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds. Atlas of Clinical Oncology: Skin Cancer. London, England: BC Decker; 2001:1-15.

2. Rigel D. Epidemiology of melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:204-209.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

4. Conley J, Lattes R, Orr W. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma (a rare variant of malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1971;28:914-936.

5. Repertinger SK, Teruya B, Sarma DP. Common spindle cell malignant neoplasms of the skin: differential diagnosis and review of the literature. Internet J Dermatol. 2009;7. https://ispub.com/IJD/7/2/11747. Accessed February 10, 2015.

6. Chang PC, Fischbein NJ, McCalmont TH, et al. Perineural spread of malignant melanoma of the head and neck: clinical and imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradial. 2004;25:5-11.

7. Cruz J, Reis-Filho JS, Lopes JM. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor-like primary cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:218-220.

8. Tsao H, Sober AJ, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:45-47.

9. Kossard S, Doherty E, Murray E. Neurotropic melanoma. a variant of desmoplastic melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1997;7:907-912.

10. Bruijn JA, Salasche S, Sober AJ, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: clinicopathologic aspects of six cases. Dermatology. 1992;185:3-8.

11. Jesitus J. Desmoplastic melanoma. Dermatology Times. March 2009:1-2.

12. Manganoni AM, Farisoglio C, Bassissi S, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: report of 5 cases. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009;2009:679010.

13. Gyorki DE, Busam K, Panageas K, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with desmoplastic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:403-407.

14. Livestro DP, Muzikansky A, Kaine EM, et al. of desmoplastic melanoma: a case-control comparison with other melanomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6739-6746.

15. Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Prieto VG, et al. Assessment of the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy for primary cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer. 2006;106:900-906.

16. Smithers HM, McLeod GR, Little JH. Desmoplastic melanoma: patterns of recurrence. World J Surg. 1992;16:186-190.

17. McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA, Palmer AA. Desmoplastic melanoma: a diagnostic trap for the unwary. Pathology. 2004;36:445-451.

18. Bruijn JA, Mihm MC Jr, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic melanoma. Histopathology. 1992;20:197-205.

1. Mikkilineni R, Weinstock MA. Epidemiology. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds. Atlas of Clinical Oncology: Skin Cancer. London, England: BC Decker; 2001:1-15.

2. Rigel D. Epidemiology of melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:204-209.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2015. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-044552.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2015.

4. Conley J, Lattes R, Orr W. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma (a rare variant of malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1971;28:914-936.

5. Repertinger SK, Teruya B, Sarma DP. Common spindle cell malignant neoplasms of the skin: differential diagnosis and review of the literature. Internet J Dermatol. 2009;7. https://ispub.com/IJD/7/2/11747. Accessed February 10, 2015.

6. Chang PC, Fischbein NJ, McCalmont TH, et al. Perineural spread of malignant melanoma of the head and neck: clinical and imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradial. 2004;25:5-11.

7. Cruz J, Reis-Filho JS, Lopes JM. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor-like primary cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:218-220.

8. Tsao H, Sober AJ, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:45-47.

9. Kossard S, Doherty E, Murray E. Neurotropic melanoma. a variant of desmoplastic melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1997;7:907-912.

10. Bruijn JA, Salasche S, Sober AJ, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: clinicopathologic aspects of six cases. Dermatology. 1992;185:3-8.

11. Jesitus J. Desmoplastic melanoma. Dermatology Times. March 2009:1-2.

12. Manganoni AM, Farisoglio C, Bassissi S, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: report of 5 cases. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009;2009:679010.

13. Gyorki DE, Busam K, Panageas K, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with desmoplastic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:403-407.

14. Livestro DP, Muzikansky A, Kaine EM, et al. of desmoplastic melanoma: a case-control comparison with other melanomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6739-6746.

15. Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Prieto VG, et al. Assessment of the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy for primary cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer. 2006;106:900-906.

16. Smithers HM, McLeod GR, Little JH. Desmoplastic melanoma: patterns of recurrence. World J Surg. 1992;16:186-190.

17. McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA, Palmer AA. Desmoplastic melanoma: a diagnostic trap for the unwary. Pathology. 2004;36:445-451.

18. Bruijn JA, Mihm MC Jr, Barnhill RL. Desmoplastic melanoma. Histopathology. 1992;20:197-205.

A 78-year-old woman presented with a large friable, sharply demarcated nodule of 3 months’ duration on the left side of the back. The lesion occasionally bled but was otherwise asymptomatic. There was no perilesional paresthesia. The patient’s medical history included hypertension, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, breast cancer, osteoporosis, and aortic valve disease.

Telangiectases on the Cheeks and Nose

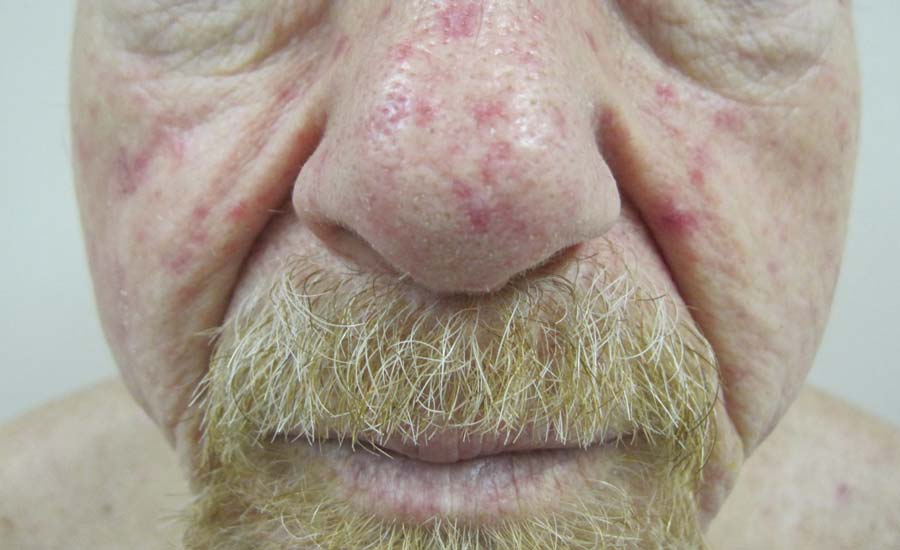

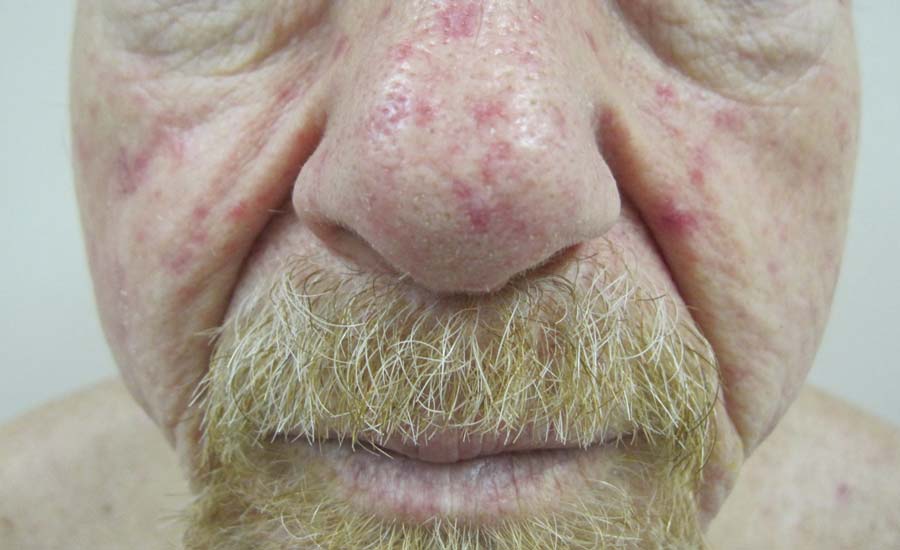

The Diagnosis: Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Physical examination of our patient revealed multiple fine punctate telangiectases on the bilateral cheeks and the dorsum of the nose. Further examination revealed matlike telangiectases on the distal aspect of the tongue (Figure), buccal mucosa, palms, and fingers. Since diagnosis he has experienced several episodes of severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding. He underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy and was found to have bleeding gastric antral vascular ectasia that was treated with argon plasma coagulation. One year later he had a second esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed because of heme-positive stools and was found to have additional bleeding vascular ectasia that was treated again with argon plasma coagulation.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by mucocutaneous and visceral telangiectases, recurrent hemorrhages, and a familial occurrence.1 In North America, the overall incidence is approximately 1 per 5000 to 10,000 individuals per year.2 Although this disorder generally has an autosomal-dominant transmission, approximately 20% of cases do not have a familial component.2

Clinically these patients most commonly present with a recurrent episode of epistaxis that occurs within the first 2 decades of life. Shortly after the onset of these recurrent episodes, patients begin to develop punctate or splinterlike telangiectases on the lips, oral mucosa, upper extremities, nail beds, and trunk. These cutaneous telangiectases are a cosmetic problem and can sometimes cause hemorrhage, especially from the tongue and fingers.1 The serious complications of HHT arise from internal organ involvement. Gastrointestinal telangiectases and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) can result in acute gastrointestinal hemorrhages or iron deficiency anemia in approximately 16% of patients. Central nervous system AVMs result in migraines, brain abscesses, paraparesis, ischemia, strokes, transient ischemic attacks, seizures, and both intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Pulmonary AVMs can cause a right-to-left shunt, leading to hypoxemia and embolic events due to the bypass of the lungs, which act as a filtering capillary bed.3

Genetic linkage analysis has revealed 2 genes that are responsible for HHT. The first gene, ENG, encodes endoglin and is found on band 9q33-34.3 The second gene, ALK1, encodes activin receptorlike kinase 1 and is found on band 12q11-12. Both of these gene products are involved with vascular remodeling. They are integral membrane glycoproteins mainly expressed on vascular endothelial cells and act as surface receptors for transforming growth factor b. Mutations in ALK1 are associated with a generally more benign course, whereas mutations in ENG more commonly have pulmonary AVMs.3

The diagnosis of HHT is established if 3 of the following features are present: (1) epistaxis (ie, spontaneous recurrent nosebleeds); (2) telangiectases in characteristic sites (ie, oral cavity, lips, nose, fingers); (3) visceral lesions, such as gastrointestinal telangiectases (with or without bleeding), pulmonary AVM, hepatic AVM, cerebral AVM, or spinal AVM; (4) family history (ie, a first-degree relative with HHT).3 Similar diseases with telangiectases should be considered in the differential diagnosis including CREST syndrome (characterized by calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia), generalized essential telangiectasia, and ataxia telangiectasia.2

Patients diagnosed with HHT who have a family history of the disease should be evaluated for pulmonary AVM through chest computed tomography and pulmonary angiography because they are at the highest risk. Magnetic resonance imaging is useful to rule out central nervous system involvement. Treatment of cutaneous telangiectases consists of electrocauterization; sclerotherapy; and a variety of lasers and light sources including the Nd:YAG laser, intense pulsed light, argon laser, or pulsed dye laser.1,2,4 An extremely useful resource for patients with HHT and family members is the HHT Foundation (http://curehht.org).

1. Fernández-Jorge B, Del Pozo Losada J, Paradela S, et al. Treatment of cutaneous and mucosal telangiectases in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: report of three cases. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9:29-33.

2. Lee HE, Sagong C, Yeo KY, et al. A case of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:206-208.

3. Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations. part II: associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541-564.

4. Sato Y, Takayama T, Takahari D, et al. Successful treatment for gastro-intestinal bleeding of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease by argon plasma coagulation using double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40(suppl 2):E228-E229.

The Diagnosis: Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Physical examination of our patient revealed multiple fine punctate telangiectases on the bilateral cheeks and the dorsum of the nose. Further examination revealed matlike telangiectases on the distal aspect of the tongue (Figure), buccal mucosa, palms, and fingers. Since diagnosis he has experienced several episodes of severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding. He underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy and was found to have bleeding gastric antral vascular ectasia that was treated with argon plasma coagulation. One year later he had a second esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed because of heme-positive stools and was found to have additional bleeding vascular ectasia that was treated again with argon plasma coagulation.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by mucocutaneous and visceral telangiectases, recurrent hemorrhages, and a familial occurrence.1 In North America, the overall incidence is approximately 1 per 5000 to 10,000 individuals per year.2 Although this disorder generally has an autosomal-dominant transmission, approximately 20% of cases do not have a familial component.2

Clinically these patients most commonly present with a recurrent episode of epistaxis that occurs within the first 2 decades of life. Shortly after the onset of these recurrent episodes, patients begin to develop punctate or splinterlike telangiectases on the lips, oral mucosa, upper extremities, nail beds, and trunk. These cutaneous telangiectases are a cosmetic problem and can sometimes cause hemorrhage, especially from the tongue and fingers.1 The serious complications of HHT arise from internal organ involvement. Gastrointestinal telangiectases and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) can result in acute gastrointestinal hemorrhages or iron deficiency anemia in approximately 16% of patients. Central nervous system AVMs result in migraines, brain abscesses, paraparesis, ischemia, strokes, transient ischemic attacks, seizures, and both intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Pulmonary AVMs can cause a right-to-left shunt, leading to hypoxemia and embolic events due to the bypass of the lungs, which act as a filtering capillary bed.3

Genetic linkage analysis has revealed 2 genes that are responsible for HHT. The first gene, ENG, encodes endoglin and is found on band 9q33-34.3 The second gene, ALK1, encodes activin receptorlike kinase 1 and is found on band 12q11-12. Both of these gene products are involved with vascular remodeling. They are integral membrane glycoproteins mainly expressed on vascular endothelial cells and act as surface receptors for transforming growth factor b. Mutations in ALK1 are associated with a generally more benign course, whereas mutations in ENG more commonly have pulmonary AVMs.3

The diagnosis of HHT is established if 3 of the following features are present: (1) epistaxis (ie, spontaneous recurrent nosebleeds); (2) telangiectases in characteristic sites (ie, oral cavity, lips, nose, fingers); (3) visceral lesions, such as gastrointestinal telangiectases (with or without bleeding), pulmonary AVM, hepatic AVM, cerebral AVM, or spinal AVM; (4) family history (ie, a first-degree relative with HHT).3 Similar diseases with telangiectases should be considered in the differential diagnosis including CREST syndrome (characterized by calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia), generalized essential telangiectasia, and ataxia telangiectasia.2

Patients diagnosed with HHT who have a family history of the disease should be evaluated for pulmonary AVM through chest computed tomography and pulmonary angiography because they are at the highest risk. Magnetic resonance imaging is useful to rule out central nervous system involvement. Treatment of cutaneous telangiectases consists of electrocauterization; sclerotherapy; and a variety of lasers and light sources including the Nd:YAG laser, intense pulsed light, argon laser, or pulsed dye laser.1,2,4 An extremely useful resource for patients with HHT and family members is the HHT Foundation (http://curehht.org).

The Diagnosis: Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Physical examination of our patient revealed multiple fine punctate telangiectases on the bilateral cheeks and the dorsum of the nose. Further examination revealed matlike telangiectases on the distal aspect of the tongue (Figure), buccal mucosa, palms, and fingers. Since diagnosis he has experienced several episodes of severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding. He underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy and was found to have bleeding gastric antral vascular ectasia that was treated with argon plasma coagulation. One year later he had a second esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed because of heme-positive stools and was found to have additional bleeding vascular ectasia that was treated again with argon plasma coagulation.

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by mucocutaneous and visceral telangiectases, recurrent hemorrhages, and a familial occurrence.1 In North America, the overall incidence is approximately 1 per 5000 to 10,000 individuals per year.2 Although this disorder generally has an autosomal-dominant transmission, approximately 20% of cases do not have a familial component.2

Clinically these patients most commonly present with a recurrent episode of epistaxis that occurs within the first 2 decades of life. Shortly after the onset of these recurrent episodes, patients begin to develop punctate or splinterlike telangiectases on the lips, oral mucosa, upper extremities, nail beds, and trunk. These cutaneous telangiectases are a cosmetic problem and can sometimes cause hemorrhage, especially from the tongue and fingers.1 The serious complications of HHT arise from internal organ involvement. Gastrointestinal telangiectases and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) can result in acute gastrointestinal hemorrhages or iron deficiency anemia in approximately 16% of patients. Central nervous system AVMs result in migraines, brain abscesses, paraparesis, ischemia, strokes, transient ischemic attacks, seizures, and both intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Pulmonary AVMs can cause a right-to-left shunt, leading to hypoxemia and embolic events due to the bypass of the lungs, which act as a filtering capillary bed.3

Genetic linkage analysis has revealed 2 genes that are responsible for HHT. The first gene, ENG, encodes endoglin and is found on band 9q33-34.3 The second gene, ALK1, encodes activin receptorlike kinase 1 and is found on band 12q11-12. Both of these gene products are involved with vascular remodeling. They are integral membrane glycoproteins mainly expressed on vascular endothelial cells and act as surface receptors for transforming growth factor b. Mutations in ALK1 are associated with a generally more benign course, whereas mutations in ENG more commonly have pulmonary AVMs.3

The diagnosis of HHT is established if 3 of the following features are present: (1) epistaxis (ie, spontaneous recurrent nosebleeds); (2) telangiectases in characteristic sites (ie, oral cavity, lips, nose, fingers); (3) visceral lesions, such as gastrointestinal telangiectases (with or without bleeding), pulmonary AVM, hepatic AVM, cerebral AVM, or spinal AVM; (4) family history (ie, a first-degree relative with HHT).3 Similar diseases with telangiectases should be considered in the differential diagnosis including CREST syndrome (characterized by calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia), generalized essential telangiectasia, and ataxia telangiectasia.2

Patients diagnosed with HHT who have a family history of the disease should be evaluated for pulmonary AVM through chest computed tomography and pulmonary angiography because they are at the highest risk. Magnetic resonance imaging is useful to rule out central nervous system involvement. Treatment of cutaneous telangiectases consists of electrocauterization; sclerotherapy; and a variety of lasers and light sources including the Nd:YAG laser, intense pulsed light, argon laser, or pulsed dye laser.1,2,4 An extremely useful resource for patients with HHT and family members is the HHT Foundation (http://curehht.org).

1. Fernández-Jorge B, Del Pozo Losada J, Paradela S, et al. Treatment of cutaneous and mucosal telangiectases in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: report of three cases. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9:29-33.

2. Lee HE, Sagong C, Yeo KY, et al. A case of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:206-208.

3. Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations. part II: associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541-564.

4. Sato Y, Takayama T, Takahari D, et al. Successful treatment for gastro-intestinal bleeding of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease by argon plasma coagulation using double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40(suppl 2):E228-E229.

1. Fernández-Jorge B, Del Pozo Losada J, Paradela S, et al. Treatment of cutaneous and mucosal telangiectases in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: report of three cases. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9:29-33.

2. Lee HE, Sagong C, Yeo KY, et al. A case of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:206-208.

3. Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations. part II: associated syndromes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:541-564.

4. Sato Y, Takayama T, Takahari D, et al. Successful treatment for gastro-intestinal bleeding of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease by argon plasma coagulation using double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40(suppl 2):E228-E229.

A 68-year-old man presented for evaluation of numerous telangiectases that developed on the cheeks, nose, lips, tongue, and fingers. He denied any history of gastrointestinal tract bleeding but admitted to numerous nosebleeds in the recent past. Family history indicated that his maternal grandmother died of an aneurysm, his mother died of a cerebral hemorrhage, 2 paternal cousins had hemochromatosis, and 2 brothers were healthy.

Bluish Red Verrucous Lesions on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Linear Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular malformation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Although almost invariably present at birth, it may appear later in childhood or even in adulthood. Lesions commonly are found on the legs and may be linear, multiple, and disseminated or sometimes confined to the digits. In the early phase of evolution, the lesions are nonkeratotic, soft, blue-red plaques, but they gradually become increasingly hyperkeratotic.1 Linear verrucous hemangioma is even more rare with few published reports.

In 1937, Halter2 first used the term verrucous hemangioma to describe a 16-year-old adolescent boy who presented with a linear purpuric cluster of plaques extending from the right buttock to the toes. Imperial and Helwig3 later described it as a distinct entity. Since then, similar lesions have been described using a variety of names such as angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, angiokeratoma corporis neviforme, keratotic hemangioma, nevus vascularis unius lateralis, and nevus keratoangiomatosus.3 Therefore, the exact incidence is difficult to determine.

Lesions generally are noted at birth or in early childhood and are often located on the lower extremities. The early lesions are bluish red in color. Secondary infection is a frequent complication, resulting in reactive papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis; thus, the older lesions acquire a verrucous or warty surface.3 Clinically, they may resemble angiokeratoma, lym-phangioma circumscriptum, verrucous epidermal nevus, verrucous cancer, or even malignant melanoma. Lesions initially resemble port-wine stains and later may become soft, bluish red vascular swellings that tend to grow in size and become verrucous.1

The histologic appearance closely resembles angiokeratoma, as both lesions show vascular spaces beneath a papillomatous and hyperkeratotic epidermis.4 However, in contrast to angiokeratoma, the vascular spaces in verrucous hemangioma also involve the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Although cases of linear verrucous hemangioma have been reported, its distribution along the lines of Blaschko is rare.5,6 It has been proposed that these lesions may actually be following dermatomal patterns or that the linear arrangement represents genetic mosaicism.5 In our case, the lesion started as a small plaque in childhood and gradually spread linearly to the buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was taken from the lesion on the right buttock, which showed numerous dilated capillaries in the dermis (Figure 2).

|

Verrucous hemangiomas are best treated by excision. Larger lesions will need grafting. There is a tendency for recurrence to occur unless excision is complete.1 Yang and Ohara7 reported 14 patients with small localized lesions that were cured by 1 session of surgery without recurrence; 9 patients with wider and more extensive lesions required combination therapy in several stages for optimal results.

1. Atherton DJ, Moss C. Naevi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. London, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004:15-60.

2. Halter K. Haemangioma verrucosum mit Osteoatrophie. Dermatol Z. 1937;75:271-279.

3. Imperial R, Helwig EB. Verrucous hemangioma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:247-253.

4. Calduch L, Ortega C, Navarro V, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:213-217.

5. Wentscher U, Happle R. Linear verrucous hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:516-518.

6. Jain VK, Aggarwal K, Jain S. Linear verrucous hemangioma on the leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:656-658.

7. Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919.

The Diagnosis: Linear Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular malformation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Although almost invariably present at birth, it may appear later in childhood or even in adulthood. Lesions commonly are found on the legs and may be linear, multiple, and disseminated or sometimes confined to the digits. In the early phase of evolution, the lesions are nonkeratotic, soft, blue-red plaques, but they gradually become increasingly hyperkeratotic.1 Linear verrucous hemangioma is even more rare with few published reports.

In 1937, Halter2 first used the term verrucous hemangioma to describe a 16-year-old adolescent boy who presented with a linear purpuric cluster of plaques extending from the right buttock to the toes. Imperial and Helwig3 later described it as a distinct entity. Since then, similar lesions have been described using a variety of names such as angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, angiokeratoma corporis neviforme, keratotic hemangioma, nevus vascularis unius lateralis, and nevus keratoangiomatosus.3 Therefore, the exact incidence is difficult to determine.

Lesions generally are noted at birth or in early childhood and are often located on the lower extremities. The early lesions are bluish red in color. Secondary infection is a frequent complication, resulting in reactive papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis; thus, the older lesions acquire a verrucous or warty surface.3 Clinically, they may resemble angiokeratoma, lym-phangioma circumscriptum, verrucous epidermal nevus, verrucous cancer, or even malignant melanoma. Lesions initially resemble port-wine stains and later may become soft, bluish red vascular swellings that tend to grow in size and become verrucous.1

The histologic appearance closely resembles angiokeratoma, as both lesions show vascular spaces beneath a papillomatous and hyperkeratotic epidermis.4 However, in contrast to angiokeratoma, the vascular spaces in verrucous hemangioma also involve the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Although cases of linear verrucous hemangioma have been reported, its distribution along the lines of Blaschko is rare.5,6 It has been proposed that these lesions may actually be following dermatomal patterns or that the linear arrangement represents genetic mosaicism.5 In our case, the lesion started as a small plaque in childhood and gradually spread linearly to the buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was taken from the lesion on the right buttock, which showed numerous dilated capillaries in the dermis (Figure 2).

|

Verrucous hemangiomas are best treated by excision. Larger lesions will need grafting. There is a tendency for recurrence to occur unless excision is complete.1 Yang and Ohara7 reported 14 patients with small localized lesions that were cured by 1 session of surgery without recurrence; 9 patients with wider and more extensive lesions required combination therapy in several stages for optimal results.

The Diagnosis: Linear Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular malformation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Although almost invariably present at birth, it may appear later in childhood or even in adulthood. Lesions commonly are found on the legs and may be linear, multiple, and disseminated or sometimes confined to the digits. In the early phase of evolution, the lesions are nonkeratotic, soft, blue-red plaques, but they gradually become increasingly hyperkeratotic.1 Linear verrucous hemangioma is even more rare with few published reports.

In 1937, Halter2 first used the term verrucous hemangioma to describe a 16-year-old adolescent boy who presented with a linear purpuric cluster of plaques extending from the right buttock to the toes. Imperial and Helwig3 later described it as a distinct entity. Since then, similar lesions have been described using a variety of names such as angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, angiokeratoma corporis neviforme, keratotic hemangioma, nevus vascularis unius lateralis, and nevus keratoangiomatosus.3 Therefore, the exact incidence is difficult to determine.

Lesions generally are noted at birth or in early childhood and are often located on the lower extremities. The early lesions are bluish red in color. Secondary infection is a frequent complication, resulting in reactive papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis; thus, the older lesions acquire a verrucous or warty surface.3 Clinically, they may resemble angiokeratoma, lym-phangioma circumscriptum, verrucous epidermal nevus, verrucous cancer, or even malignant melanoma. Lesions initially resemble port-wine stains and later may become soft, bluish red vascular swellings that tend to grow in size and become verrucous.1

The histologic appearance closely resembles angiokeratoma, as both lesions show vascular spaces beneath a papillomatous and hyperkeratotic epidermis.4 However, in contrast to angiokeratoma, the vascular spaces in verrucous hemangioma also involve the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Although cases of linear verrucous hemangioma have been reported, its distribution along the lines of Blaschko is rare.5,6 It has been proposed that these lesions may actually be following dermatomal patterns or that the linear arrangement represents genetic mosaicism.5 In our case, the lesion started as a small plaque in childhood and gradually spread linearly to the buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was taken from the lesion on the right buttock, which showed numerous dilated capillaries in the dermis (Figure 2).

|

Verrucous hemangiomas are best treated by excision. Larger lesions will need grafting. There is a tendency for recurrence to occur unless excision is complete.1 Yang and Ohara7 reported 14 patients with small localized lesions that were cured by 1 session of surgery without recurrence; 9 patients with wider and more extensive lesions required combination therapy in several stages for optimal results.

1. Atherton DJ, Moss C. Naevi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. London, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004:15-60.

2. Halter K. Haemangioma verrucosum mit Osteoatrophie. Dermatol Z. 1937;75:271-279.

3. Imperial R, Helwig EB. Verrucous hemangioma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:247-253.

4. Calduch L, Ortega C, Navarro V, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:213-217.

5. Wentscher U, Happle R. Linear verrucous hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:516-518.

6. Jain VK, Aggarwal K, Jain S. Linear verrucous hemangioma on the leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:656-658.

7. Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919.

1. Atherton DJ, Moss C. Naevi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. London, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004:15-60.

2. Halter K. Haemangioma verrucosum mit Osteoatrophie. Dermatol Z. 1937;75:271-279.

3. Imperial R, Helwig EB. Verrucous hemangioma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:247-253.

4. Calduch L, Ortega C, Navarro V, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:213-217.

5. Wentscher U, Happle R. Linear verrucous hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:516-518.

6. Jain VK, Aggarwal K, Jain S. Linear verrucous hemangioma on the leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:656-658.

7. Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919.

An 18-year-old man presented with a history of multiple bluish verrucous lesions over the right leg. A small nodule on the lateral aspect of the right ankle was present at birth; it increased in size and number and gradually extended to the right buttock. He had recurrent bleeding and infection over the lesions. No other remarkable comorbidities were noted. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple well-circumscribed, bluish red, verrucous lesions distributed linearly along the lateral aspect of the leg. The surface of the lesions was verruciform and showed crusting at places. The second and third toes on the right foot were involved. On the buttock, multiple well-defined, bluish red plaques were present. Both limbs were of equal length.

An Incidental Finding During Neuro Evaluation

ANSWER

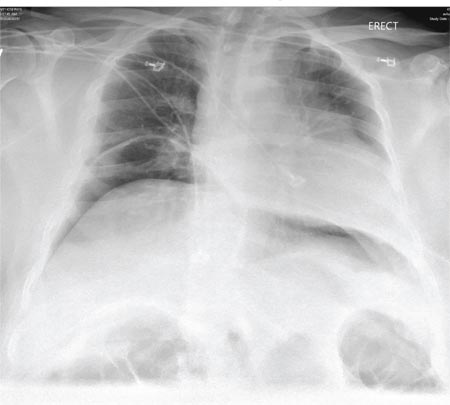

The radiograph shows a normal-appearing chest. Of note, though, is an anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. In addition, there is a fracture within the greater tuberosity of the right humerus.

Prompt orthopedic evaluation is obtained. In further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient had been experiencing falls recently; this injury was most likely the result of one.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a normal-appearing chest. Of note, though, is an anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. In addition, there is a fracture within the greater tuberosity of the right humerus.

Prompt orthopedic evaluation is obtained. In further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient had been experiencing falls recently; this injury was most likely the result of one.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a normal-appearing chest. Of note, though, is an anterior dislocation of the right shoulder. In addition, there is a fracture within the greater tuberosity of the right humerus.

Prompt orthopedic evaluation is obtained. In further discussion with the family, it was revealed that the patient had been experiencing falls recently; this injury was most likely the result of one.

A 65-year-old woman is transferred to your facility from an outlying hospital for evaluation of a brain tumor. Family members found the patient sitting on the sofa, with a decreased level of consciousness. There was reported “seizure-type activity.” When she arrived at the outlying hospital, the patient was noted to have right-side weakness. Stat CT of the head demonstrated a fairly large parasagittal mass, and the patient was urgently transferred to your facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Primary survey on arrival shows an older female who is awake, alert, and in no obvious distress. Vital signs are normal. She has fairly pronounced right upper extremity weakness, more proximally than distally. Otherwise, the exam grossly appears normal. The patient’s initial imaging studies were sent with her on a CD. As you are trying to view the images of the brain, a chest radiograph pops up on your screen. What is your impression?

What Does This Man Need (Besides Milk & Cookies)?

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block with 2:1 conduction; possible left atrial enlargement; and ST-T wave abnormalities suspicious for lateral ischemia.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the P waves that march through at a rate that is consistently double that of the QRS rate (82 beats/min). The PR interval in the conducted beats remains constant, with every other P wave blocked from conducting into the ventricles.

The biphasic P wave seen in lead V1 does not meet criteria for left atrial enlargement (P wave in lead I ≥ 110 ms, terminal negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2) but is suspicious. Finally, ST-T wave elevations in leads V2-V4 are suspicious for ventricular septal ischemia.

The patient underwent placement of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. He has done well since.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block with 2:1 conduction; possible left atrial enlargement; and ST-T wave abnormalities suspicious for lateral ischemia.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the P waves that march through at a rate that is consistently double that of the QRS rate (82 beats/min). The PR interval in the conducted beats remains constant, with every other P wave blocked from conducting into the ventricles.

The biphasic P wave seen in lead V1 does not meet criteria for left atrial enlargement (P wave in lead I ≥ 110 ms, terminal negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2) but is suspicious. Finally, ST-T wave elevations in leads V2-V4 are suspicious for ventricular septal ischemia.

The patient underwent placement of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. He has done well since.

ANSWER

This ECG is representative of sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block with 2:1 conduction; possible left atrial enlargement; and ST-T wave abnormalities suspicious for lateral ischemia.

Sinus rhythm is evidenced by the P waves that march through at a rate that is consistently double that of the QRS rate (82 beats/min). The PR interval in the conducted beats remains constant, with every other P wave blocked from conducting into the ventricles.

The biphasic P wave seen in lead V1 does not meet criteria for left atrial enlargement (P wave in lead I ≥ 110 ms, terminal negative P wave in lead V1 ≥ 1 mm2) but is suspicious. Finally, ST-T wave elevations in leads V2-V4 are suspicious for ventricular septal ischemia.

The patient underwent placement of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. He has done well since.