User login

Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Halobetasol Propionate 0.01%–Tazarotene 0.045% Lotion for Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis in the Hispanic Population: Post Hoc Analysis

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting a diverse patient population, yet epidemiological and clinical data related to psoriasis in patients with skin of color are sparse. The Hispanic ethnic group includes a broad range of skin types and cultures. Prevalence of psoriasis in a Hispanic population has been reported as lower than in a white population1; however, these data may be influenced by the finding that Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when they have skin problems.2 In addition, socioeconomic disparities and cultural variations among racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in access to care and thresholds for seeking care,3 leading to a tendency for more severe disease in skin of color and Hispanic ethnic groups.4,5 Greater impairments in health-related quality of life have been reported in patients with skin of color and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups compared to white patients, independent of psoriasis severity.4,6 Postinflammatory pigment alteration at the sites of resolving lesions, a common clinical feature in skin of color, may contribute to the impact of psoriasis on quality of life in patients with skin of color. Psoriasis in darker skin types also can present diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other papulosquamous disorders and less conspicuous erythema.7

We present a post hoc analysis of the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a novel fixed-combination halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%–tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045% lotion in a Hispanic patient population. Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic patients and other patients with skin of color; in this analysis, the Hispanic population (115/418) represented 28% of the total study population and provided valuable insights.

Methods

Study Design

Two phase 3 randomized controlled trials were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of HP/TAZ lotion. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of moderate or severe localized psoriasis (N=418) were randomized to receive HP/TAZ lotion or vehicle (2:1 ratio) once daily for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up.8,9 A post hoc analysis was conducted on data of the self-identified Hispanic population.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments included treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline in the investigator global assessment [IGA] and a score of clear or almost clear) and impact on individual signs of psoriasis (at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) at the target lesion. In addition, reduction in body surface area (BSA) was recorded, and an IGA×BSA score was calculated by multiplying IGA by BSA at each timepoint for each individual patient. A clinically meaningful improvement in disease severity (percentage of patients achieving a 75% reduction in IGA×BSA [IGA×BSA-75]) also was calculated.

Information on reported and observed adverse events (AEs) was obtained at each visit. The safety population included 112 participants (76 in the HP/TAZ group and 36 in the vehicle group).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical and analytical plan is detailed elsewhere9 and relevant to this post hoc analysis. No statistical analysis was carried out to compare data in the Hispanic population with either the overall study population or the non-Hispanic population.

Results

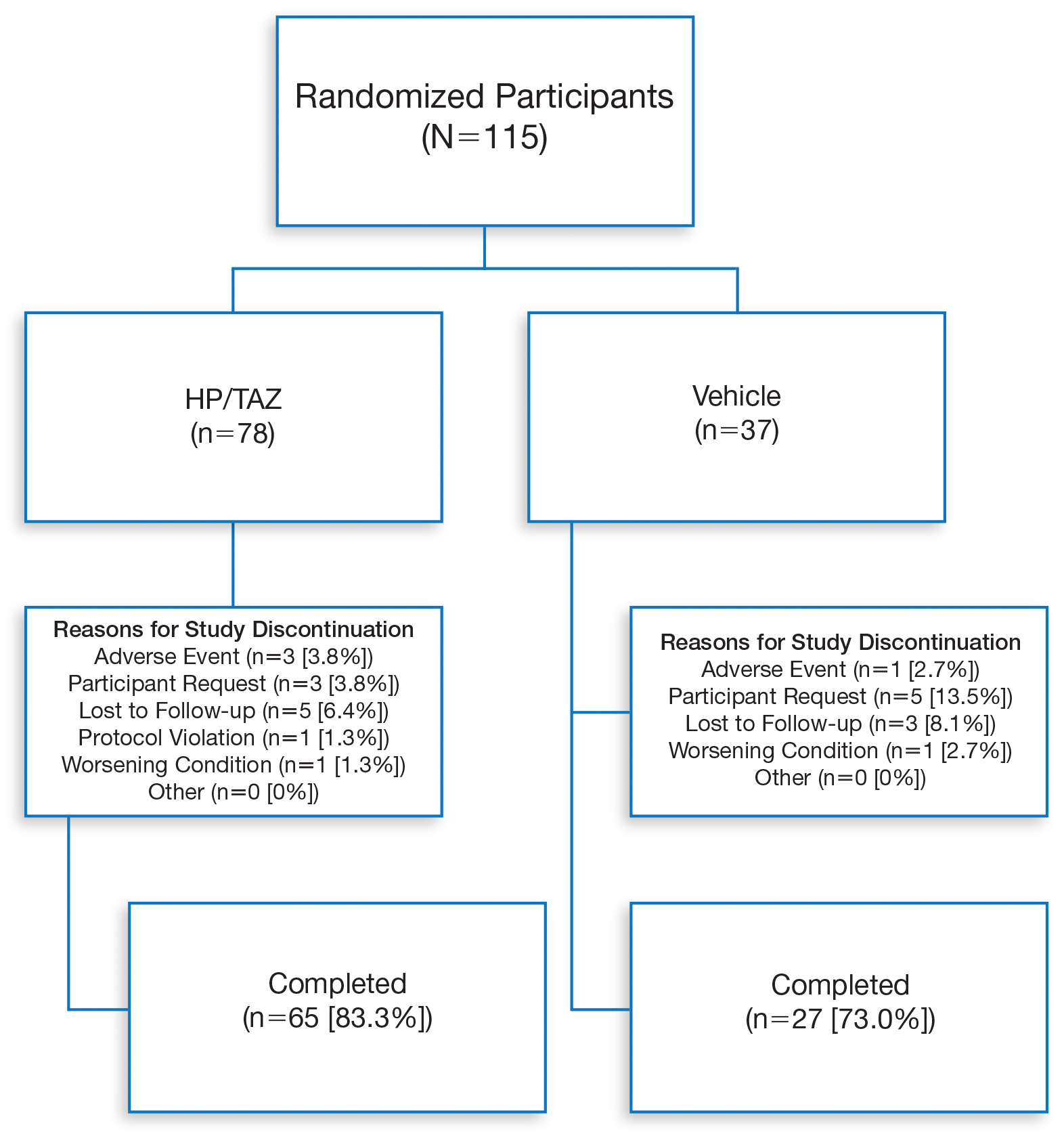

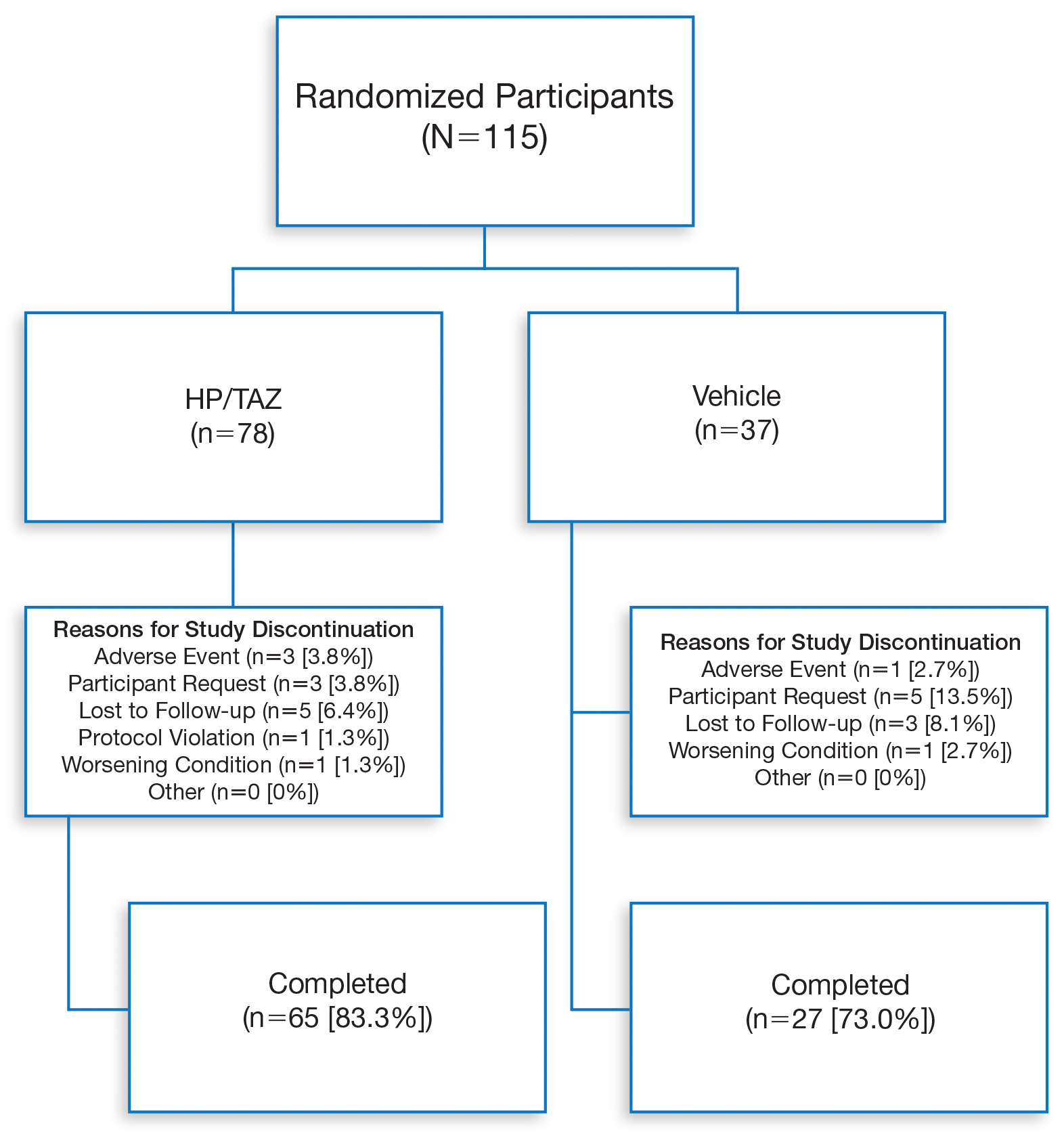

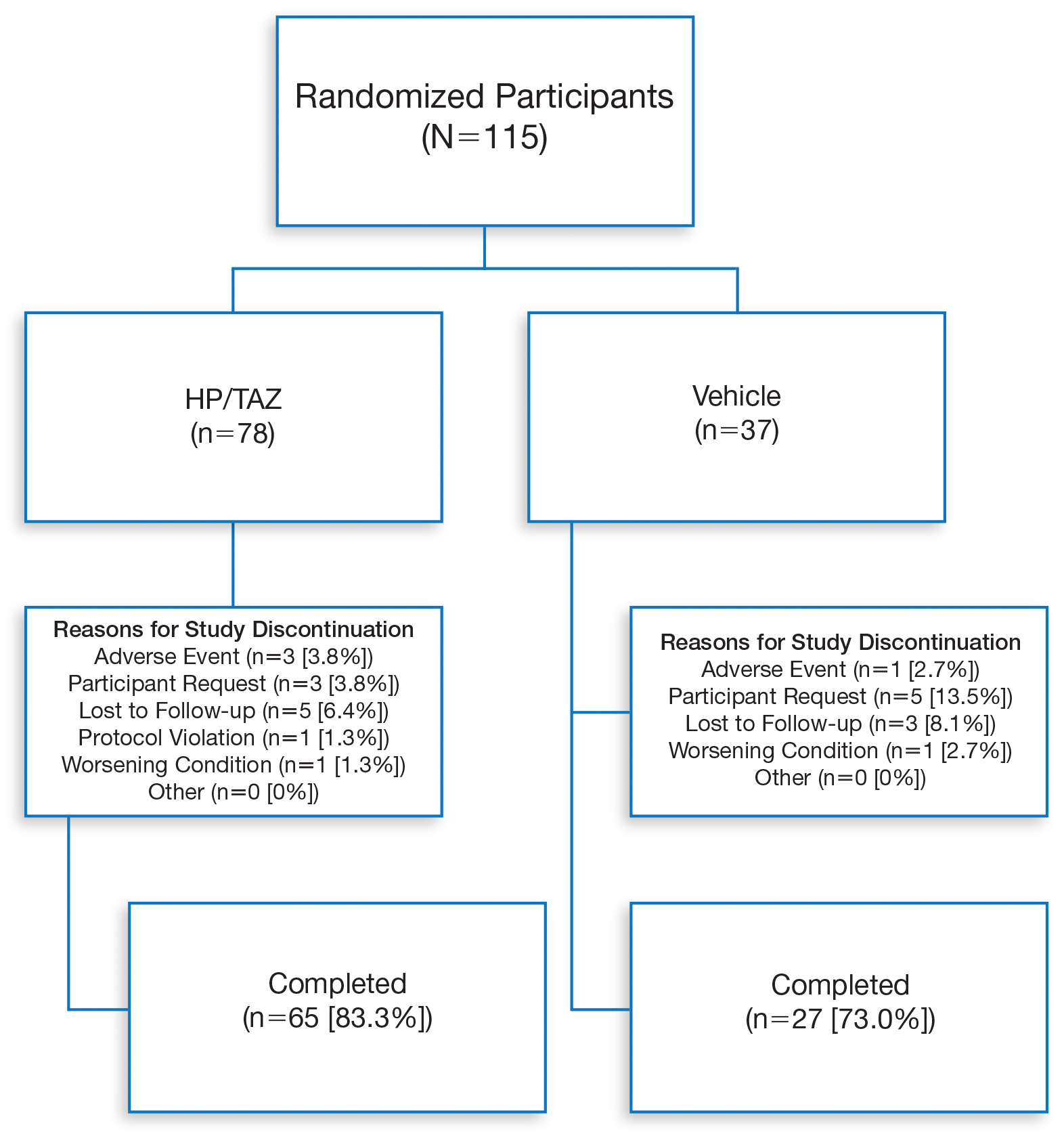

Overall, 115 Hispanic patients (27.5%) were enrolled (eFigure). Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 46.7 (13.12) years, and more than two-thirds were male (n=80, 69.6%).

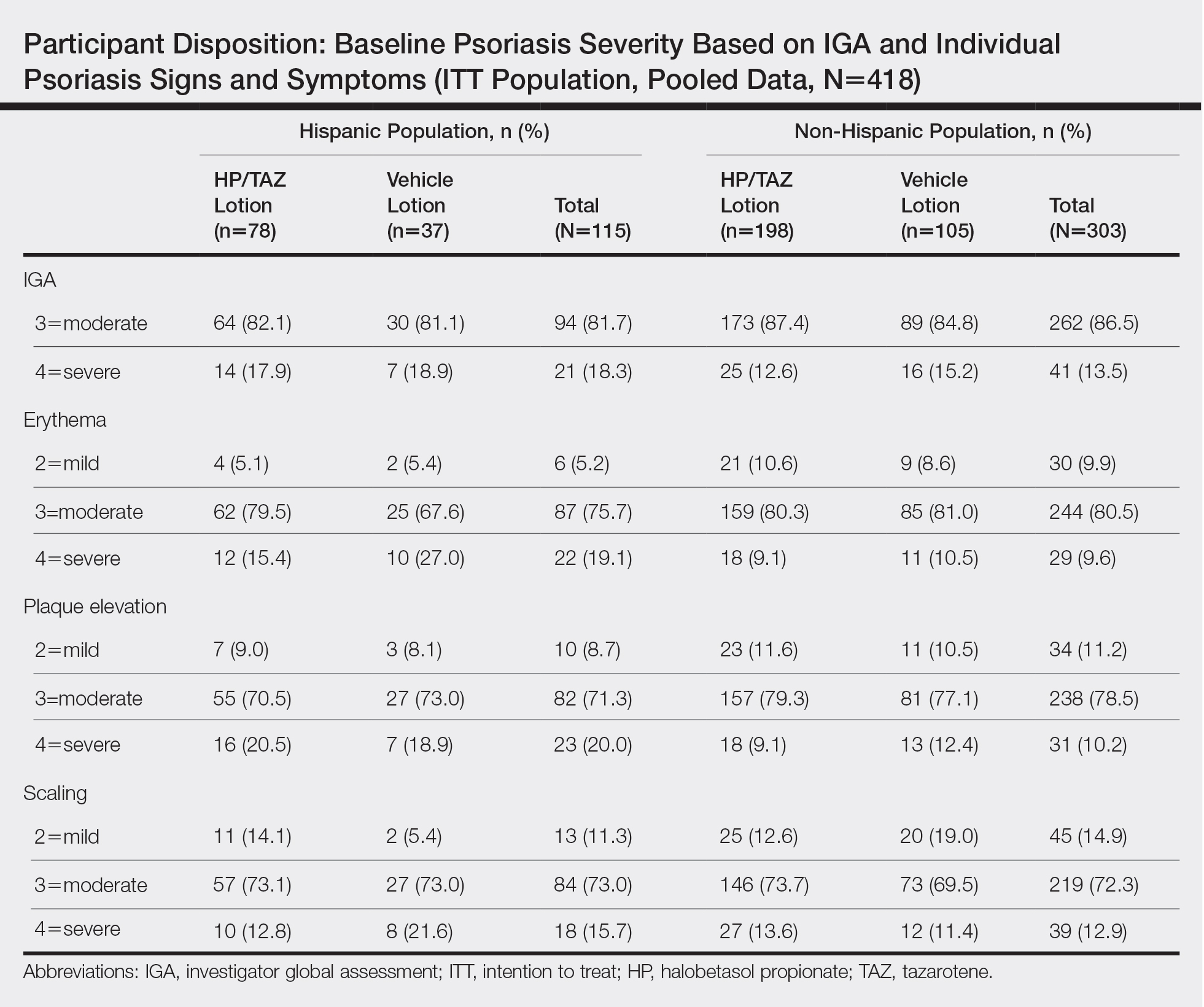

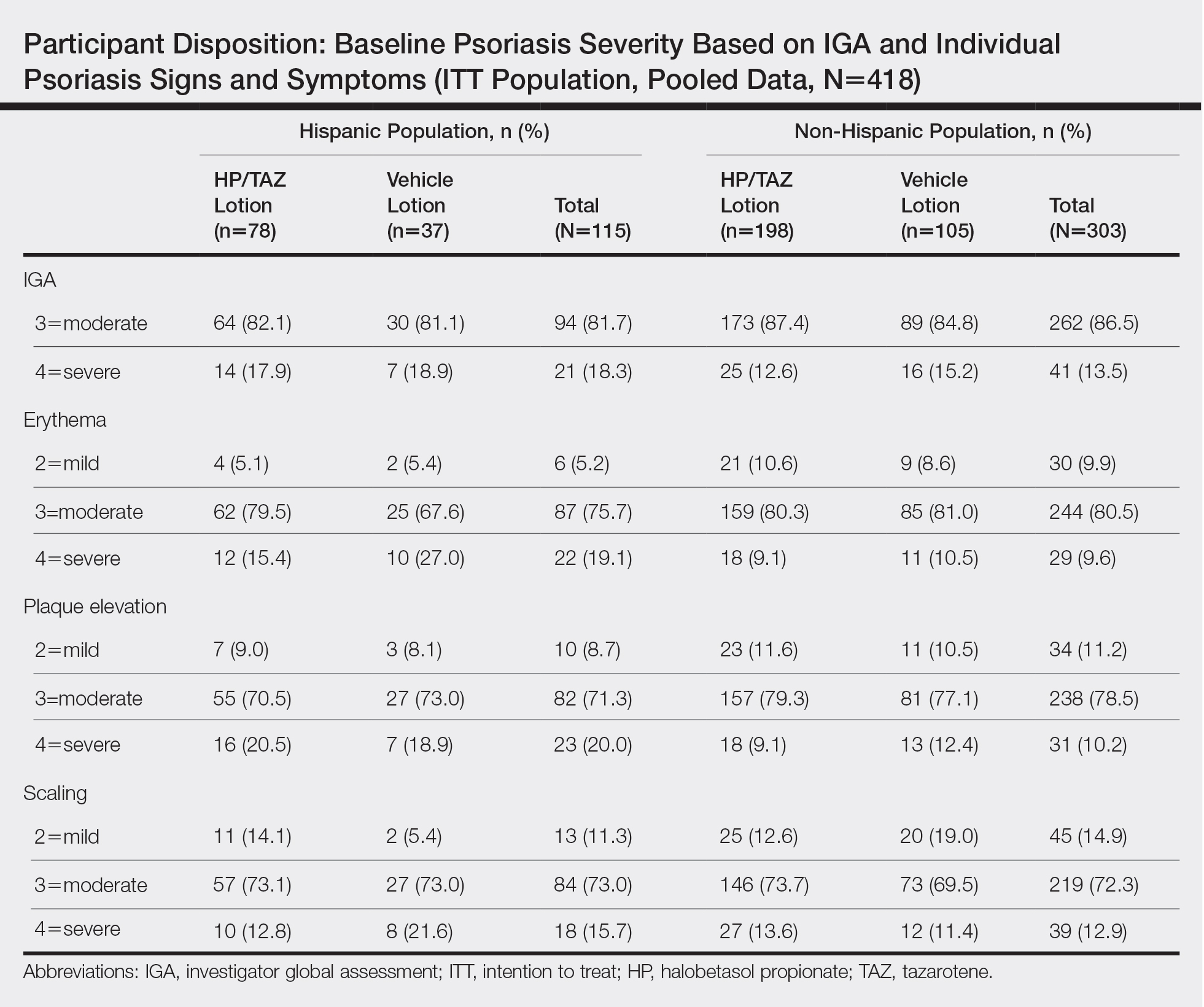

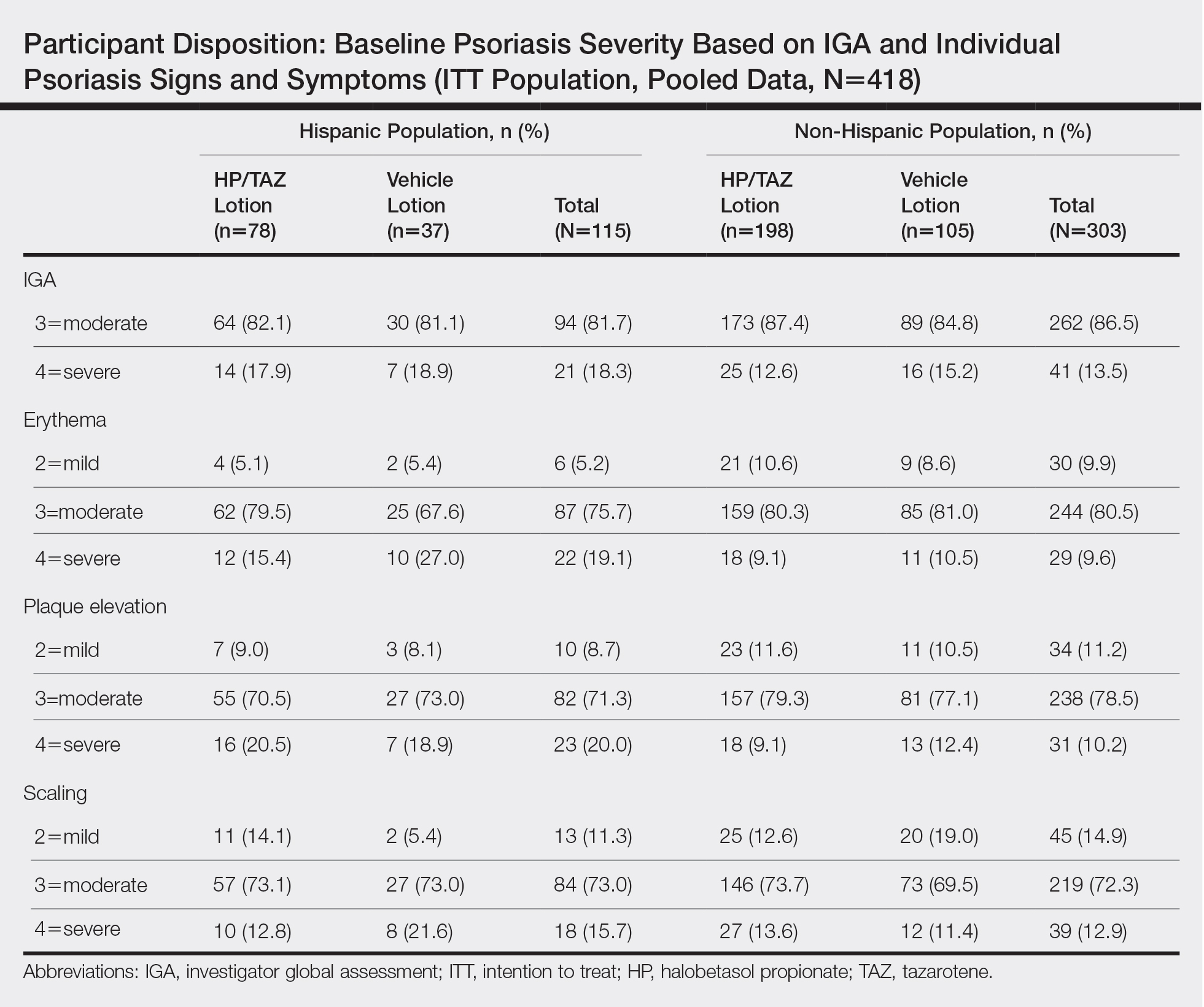

Overall completion rates (80.0%) for Hispanic patients were similar to those in the overall study population, though there were more discontinuations in the vehicle group. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation among Hispanic patients were participant request (n=8, 7.0%), lost to follow-up (n=8, 7.0%), and AEs (n=4, 3.5%). Hispanic patients in this study had more severe disease—18.3% (n=21) had an IGA score of 4 compared to 13.5% (n=41) of non-Hispanic patients—and more severe erythema (19.1% vs 9.6%), plaque elevation (20.0% vs 10.2%), and scaling (15.7% vs 12.9%) compared to the non-Hispanic populations (Table).

Efficacy of HP/TAZ lotion in Hispanic patients was similar to the overall study populations,9 though maintenance of effect posttreatment appeared to be better. The incidence of treatment-related AEs also was lower.

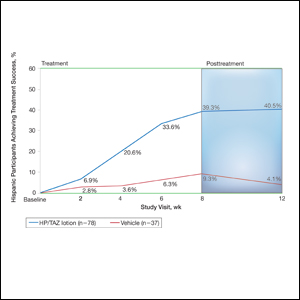

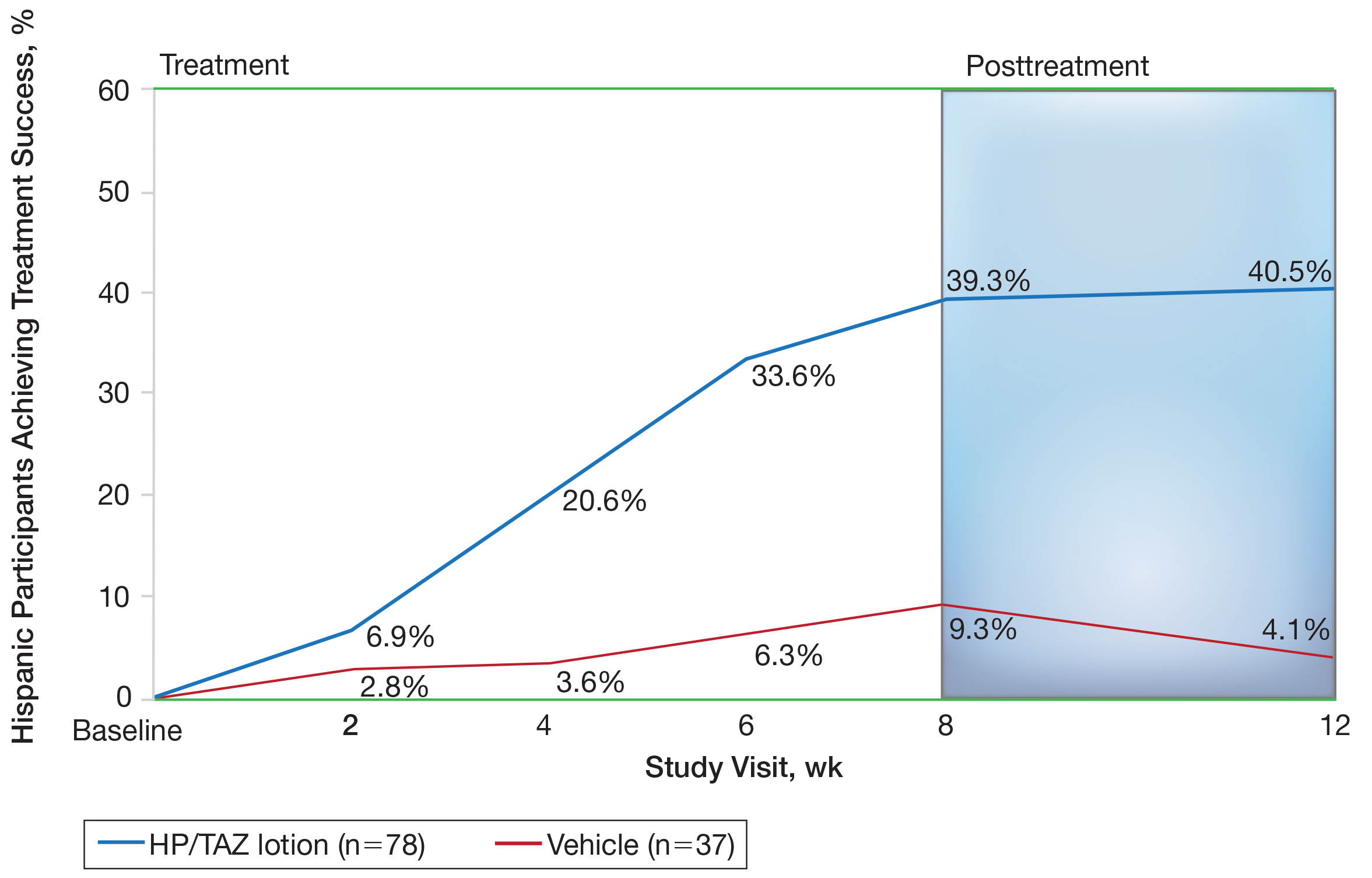

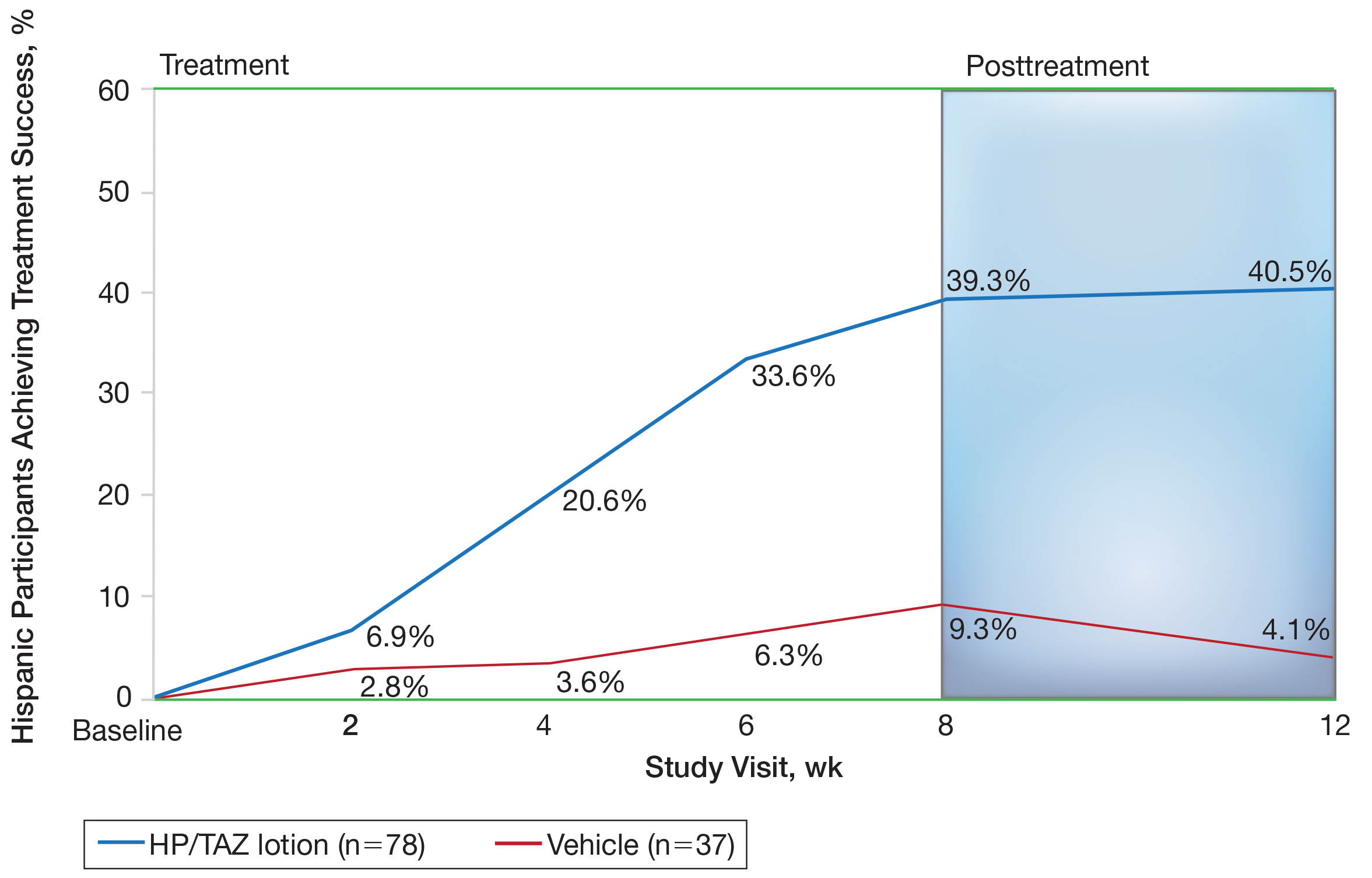

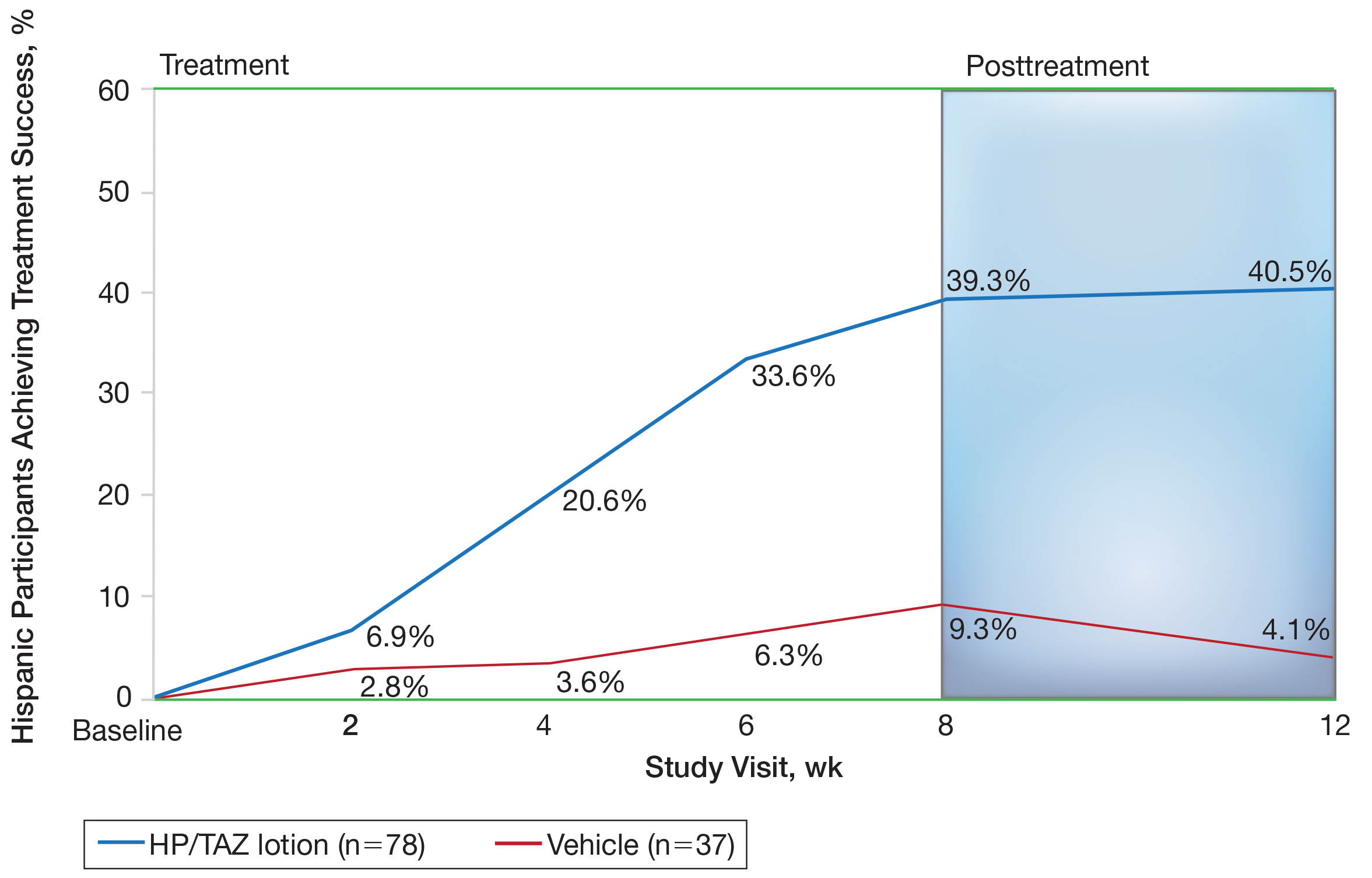

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority based on treatment success compared to vehicle as early as week 4 (P=.034). By week 8, 39.3% of participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion achieved treatment success compared to 9.3% of participants in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 1). Treatment success was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period, whereby 40.5% of the HP/TAZ-treated participants were treatment successes at week 12 compared to only 4.1% of participants in the vehicle group (P<.001).

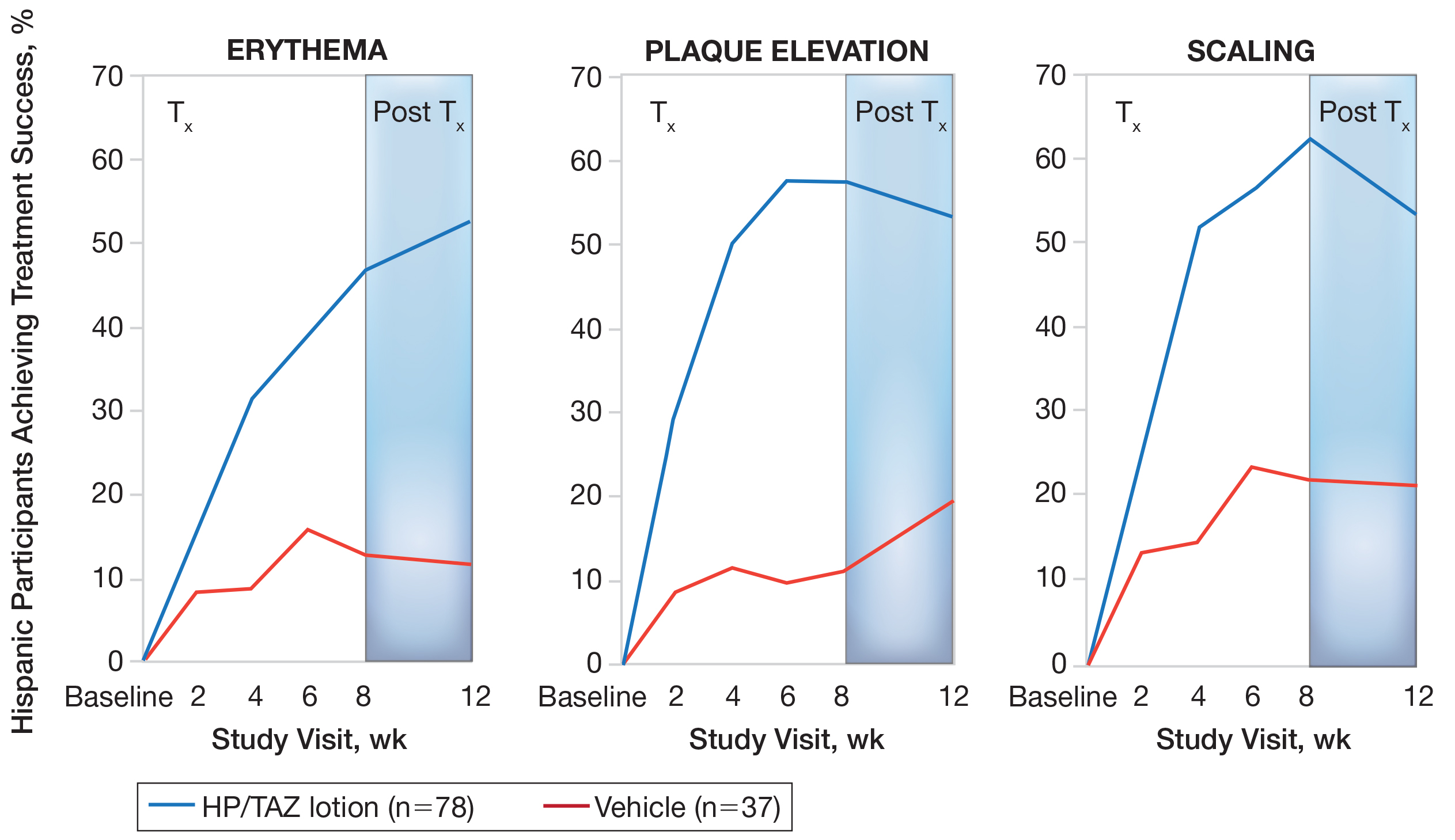

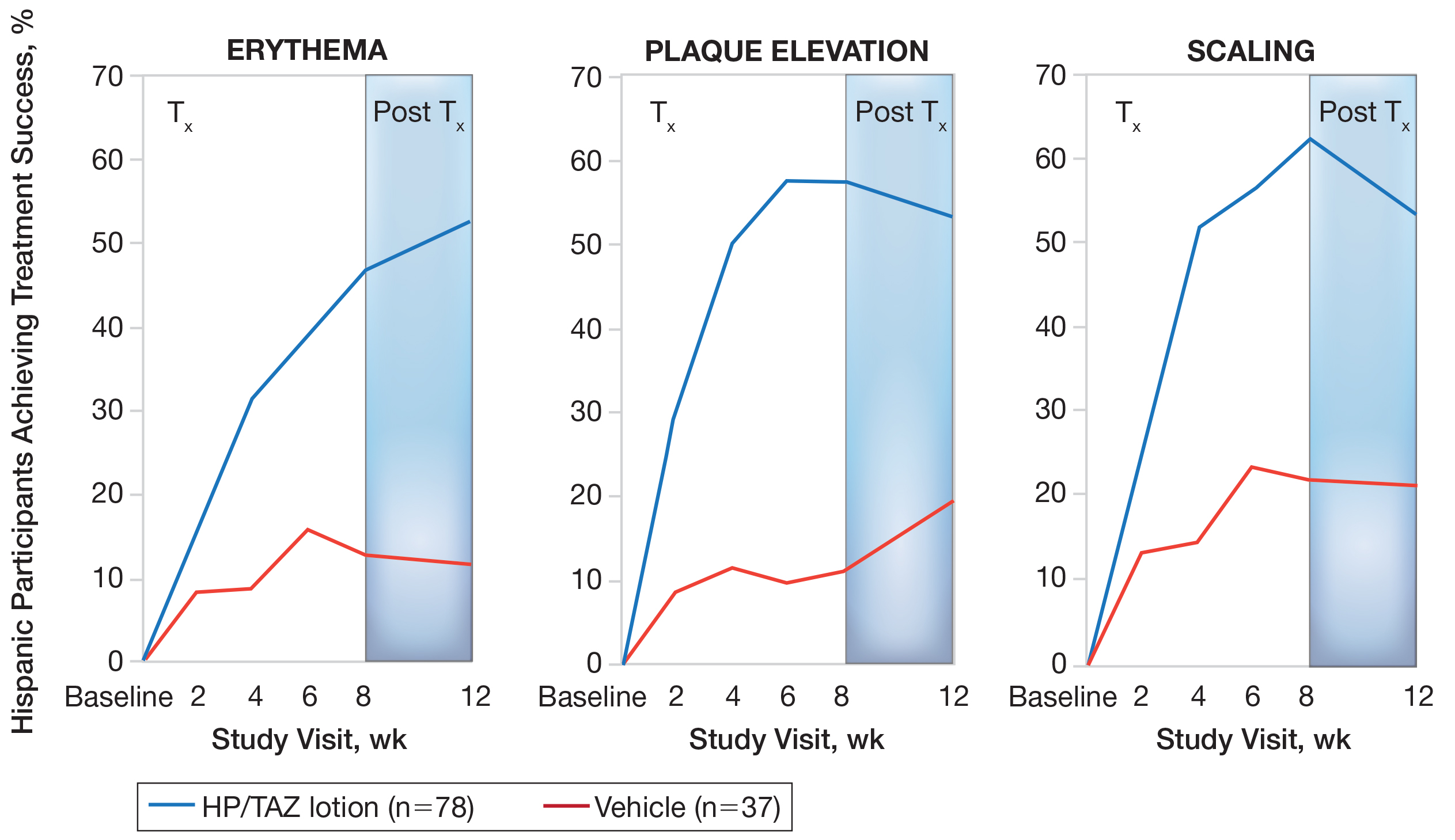

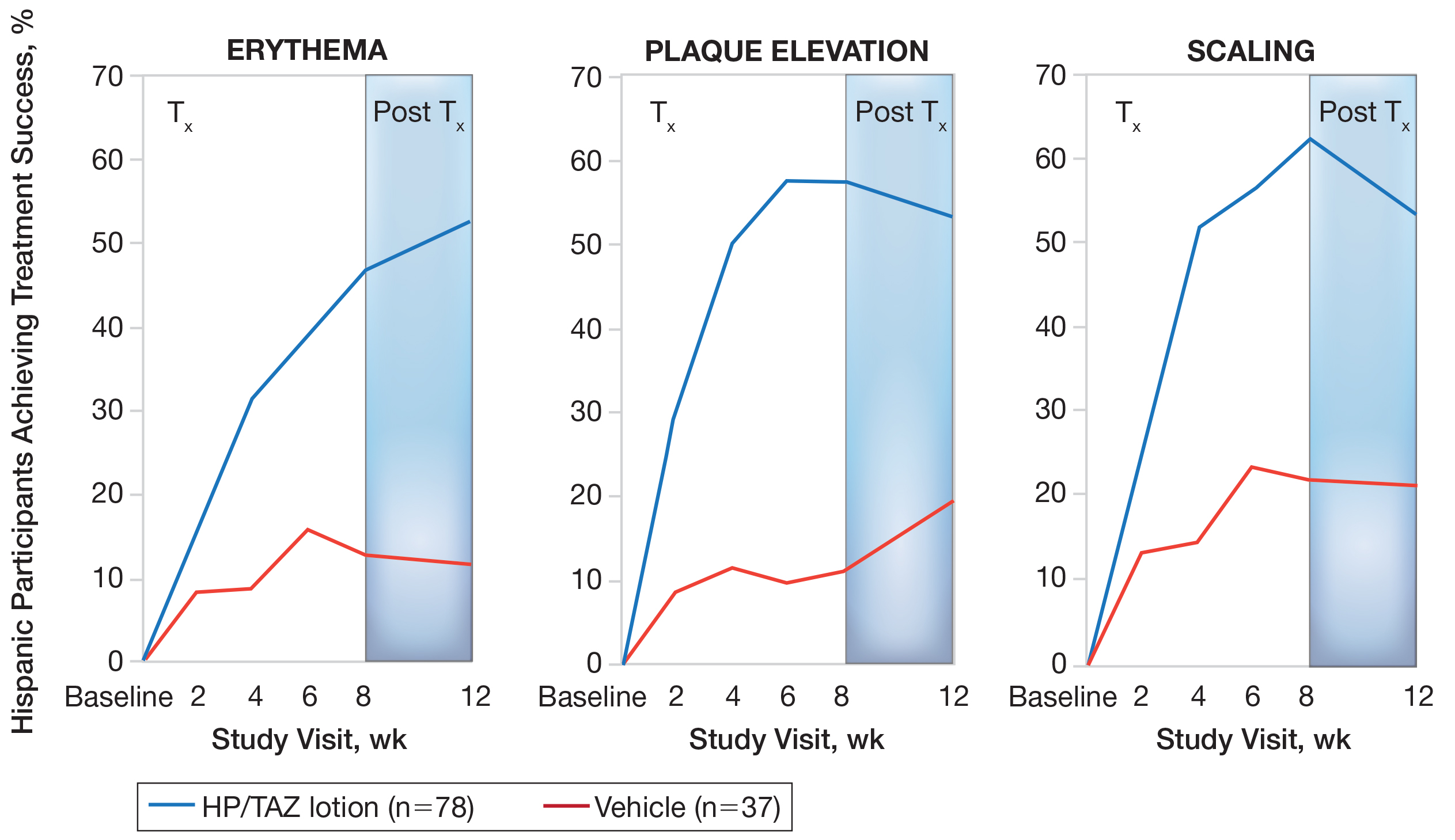

Improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms at the target lesion were statistically significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (plaque elevation, P=.018) or week 4 (erythema, P=.004; scaling, P<.001)(Figure 2). By week 8, 46.8%, 58.1%, and 63.2% of participants showed at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline and were therefore treatment successes for erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling, respectively (all statistically significant [P<.001] compared to vehicle). The number of participants who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema with HP/TAZ lotion increased posttreatment from 46.8% to 53.0%.

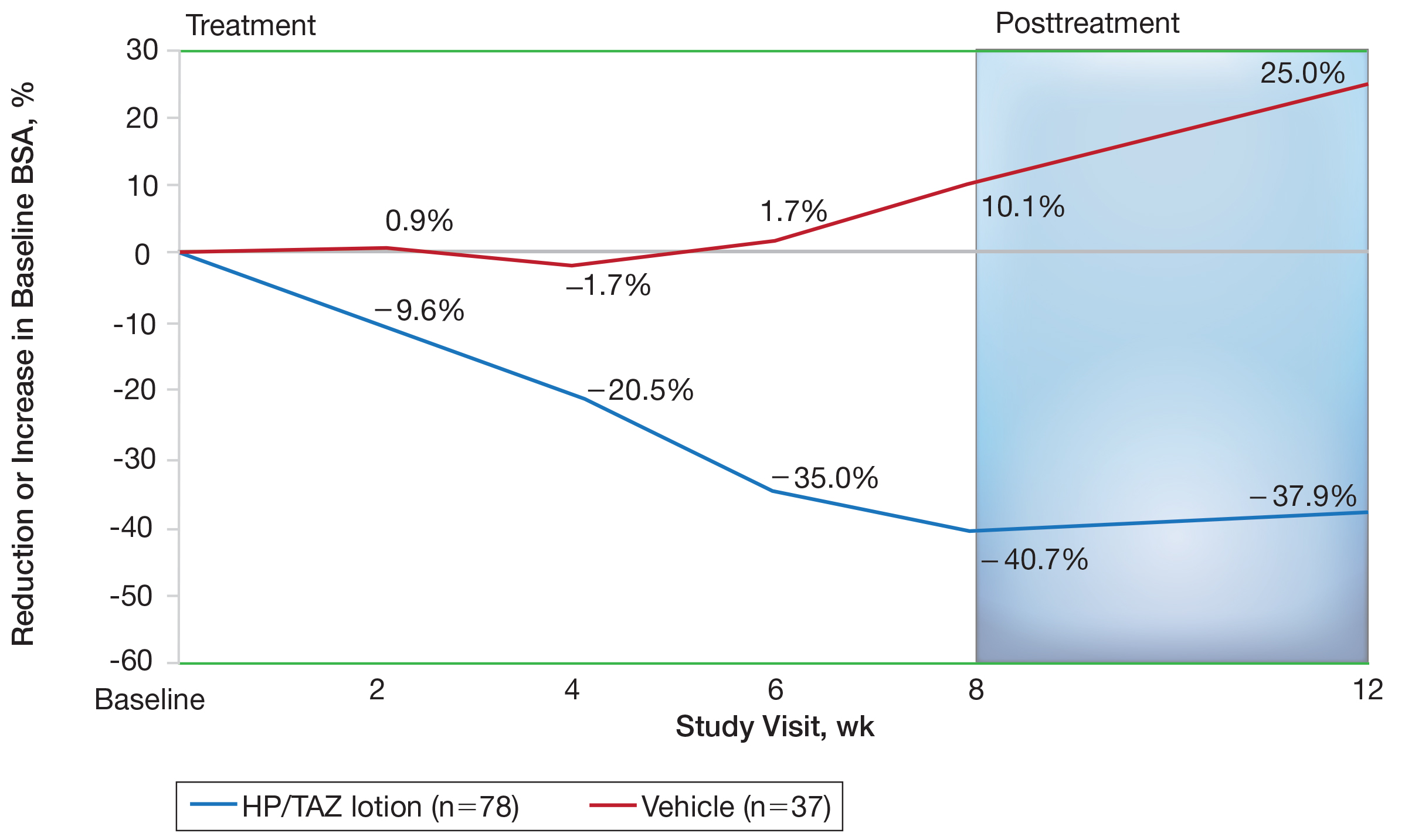

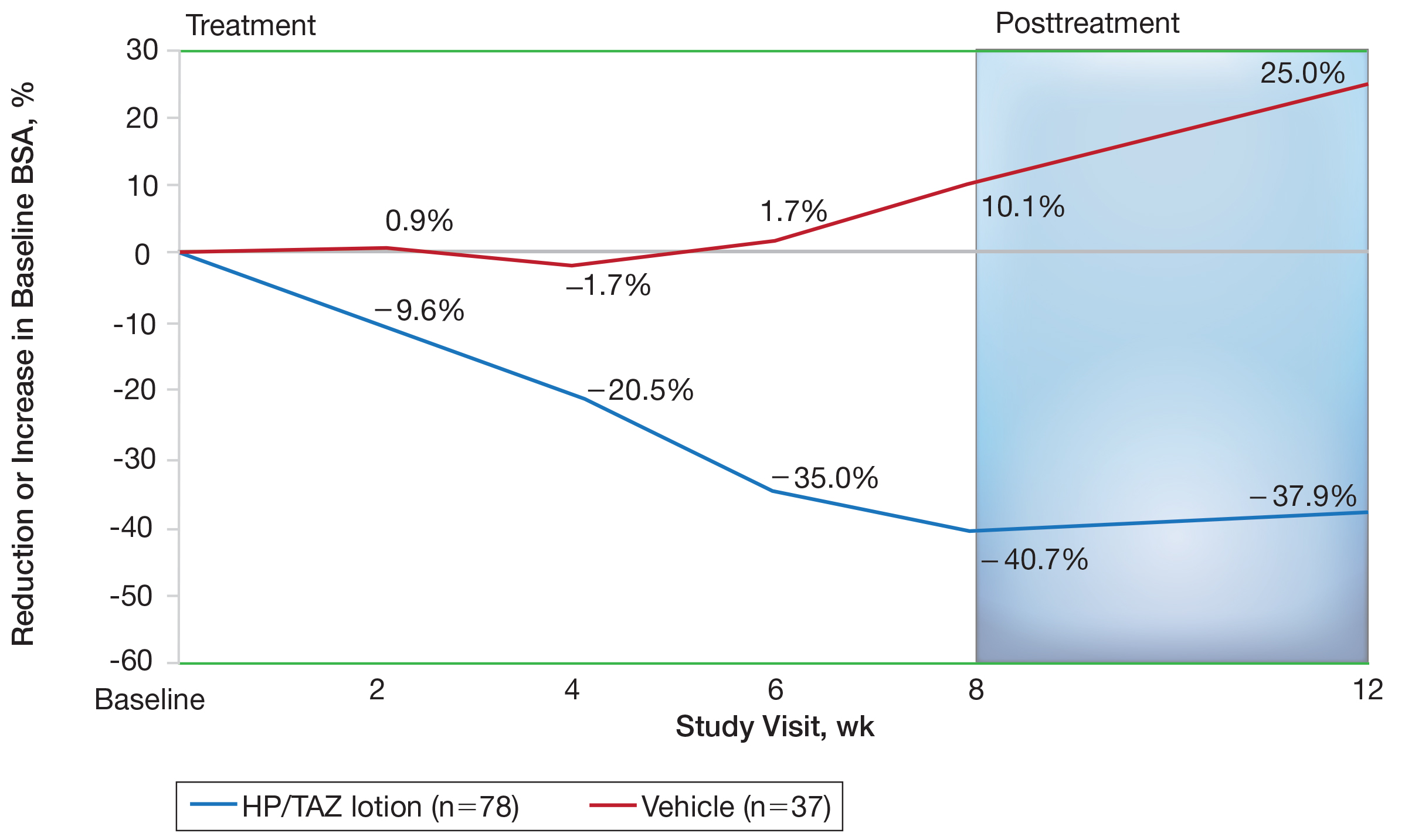

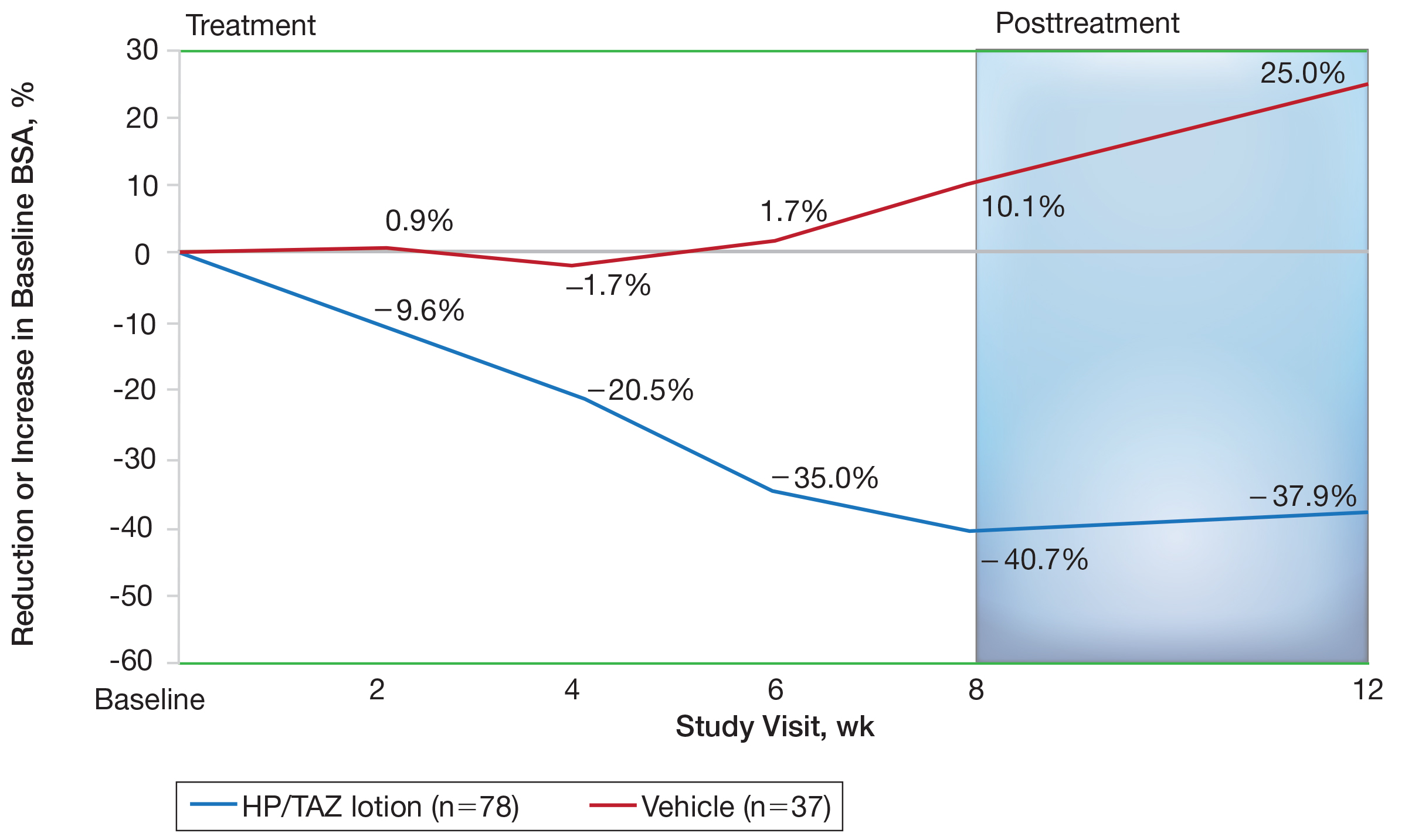

Mean (SD) baseline BSA was 6.2 (3.07), and the mean (SD) size of the target lesion was 36.3 (21.85) cm2. Overall, BSA also was significantly reduced in participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to vehicle. At week 8, the mean percentage change from baseline was —40.7% compared to an increase (+10.1%) in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 3). Improvements in BSA were maintained posttreatment, whereas in the vehicle group, mean (SD) BSA had increased to 6.1 (4.64).

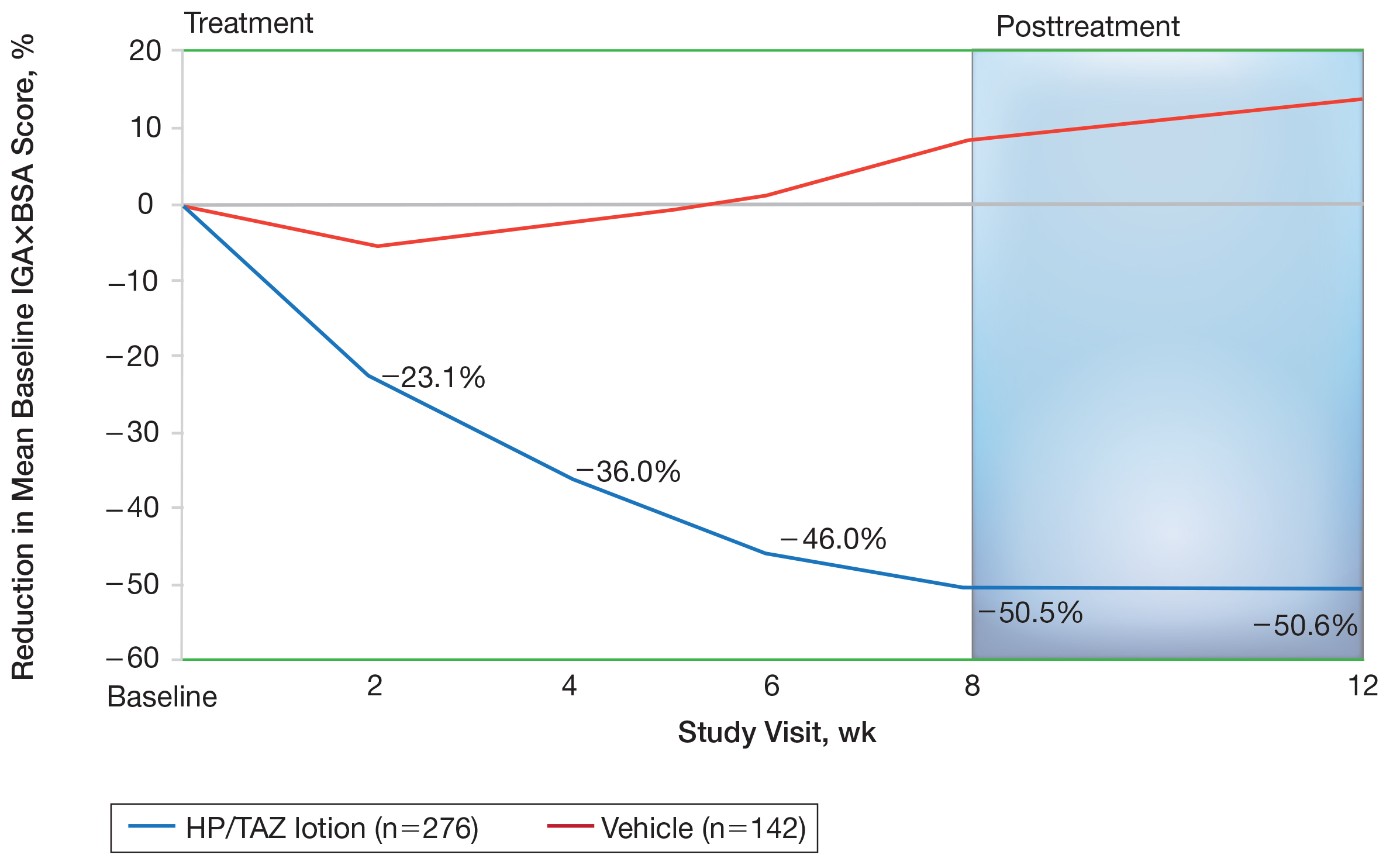

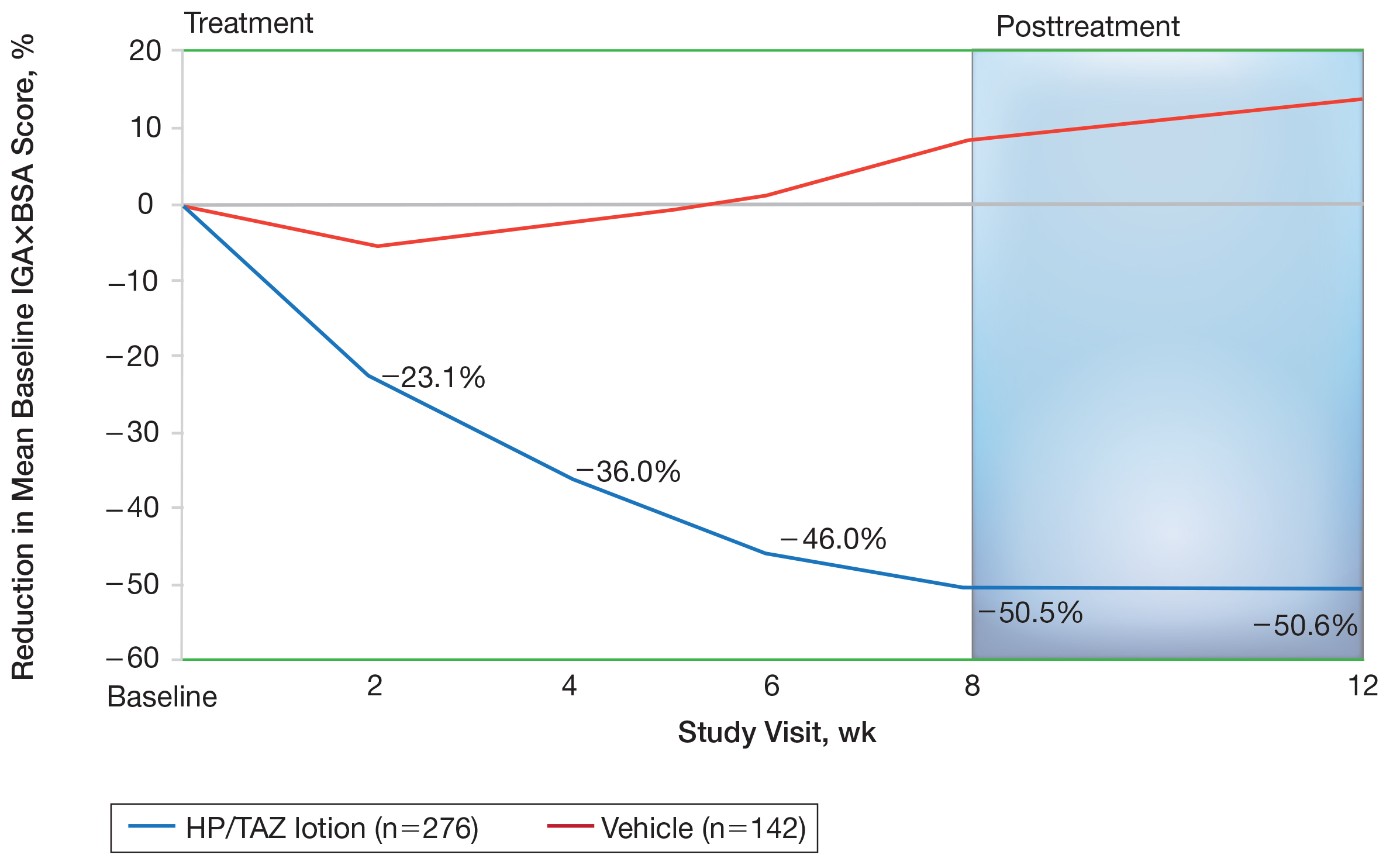

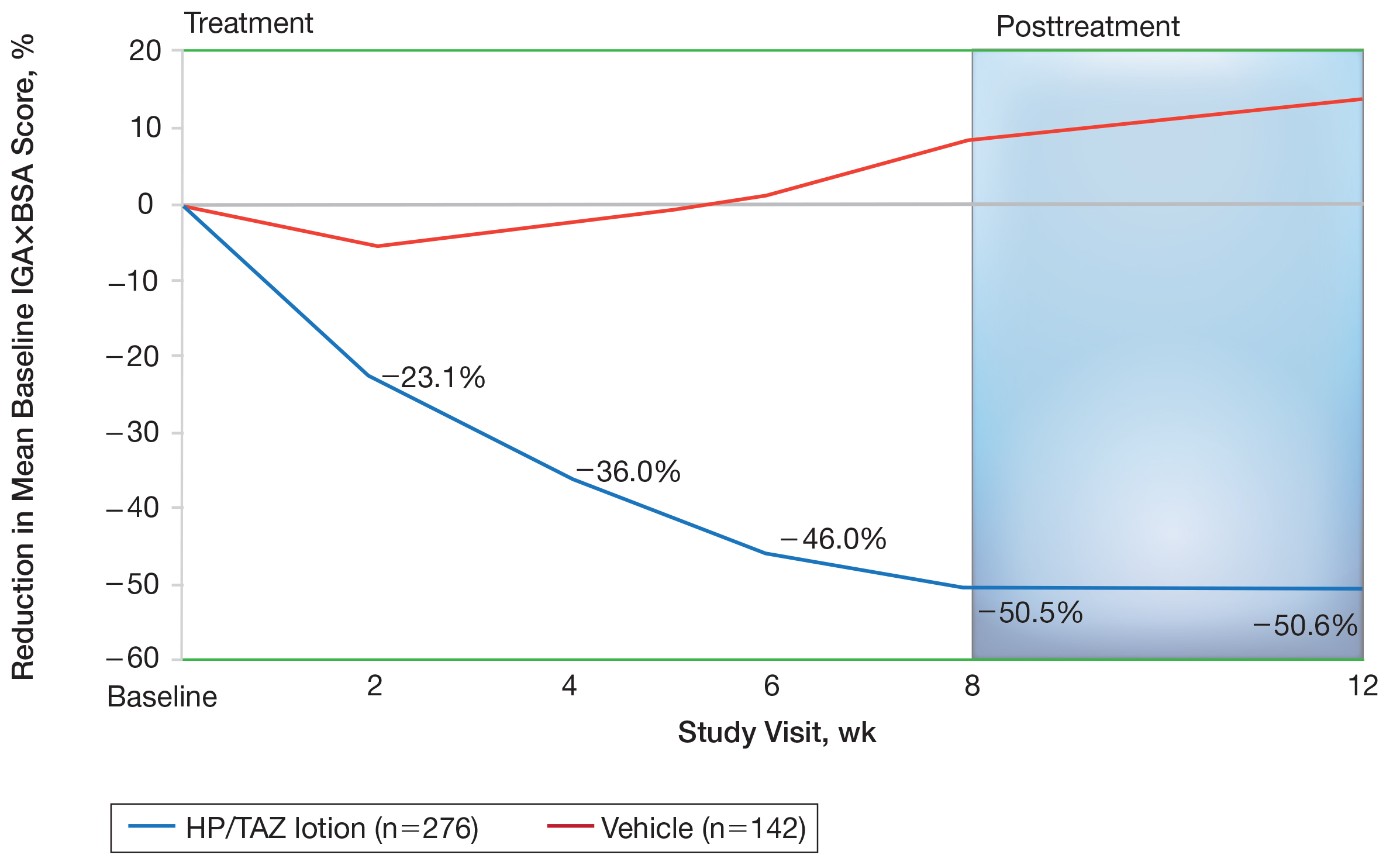

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion achieved a 50.5% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA by week 8 compared to an 8.5% increase with vehicle (P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in treatment groups were significant from week 2 (P=.016). Efficacy was maintained posttreatment, with a 50.6% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA at week 12 compared to an increase of 13.6% in the vehicle group (P<.001). Again, although results were similar to the overall study population at week 8 (50.5% vs 51.9%), maintenance of effect was better posttreatment (50.6% vs 46.6%).10

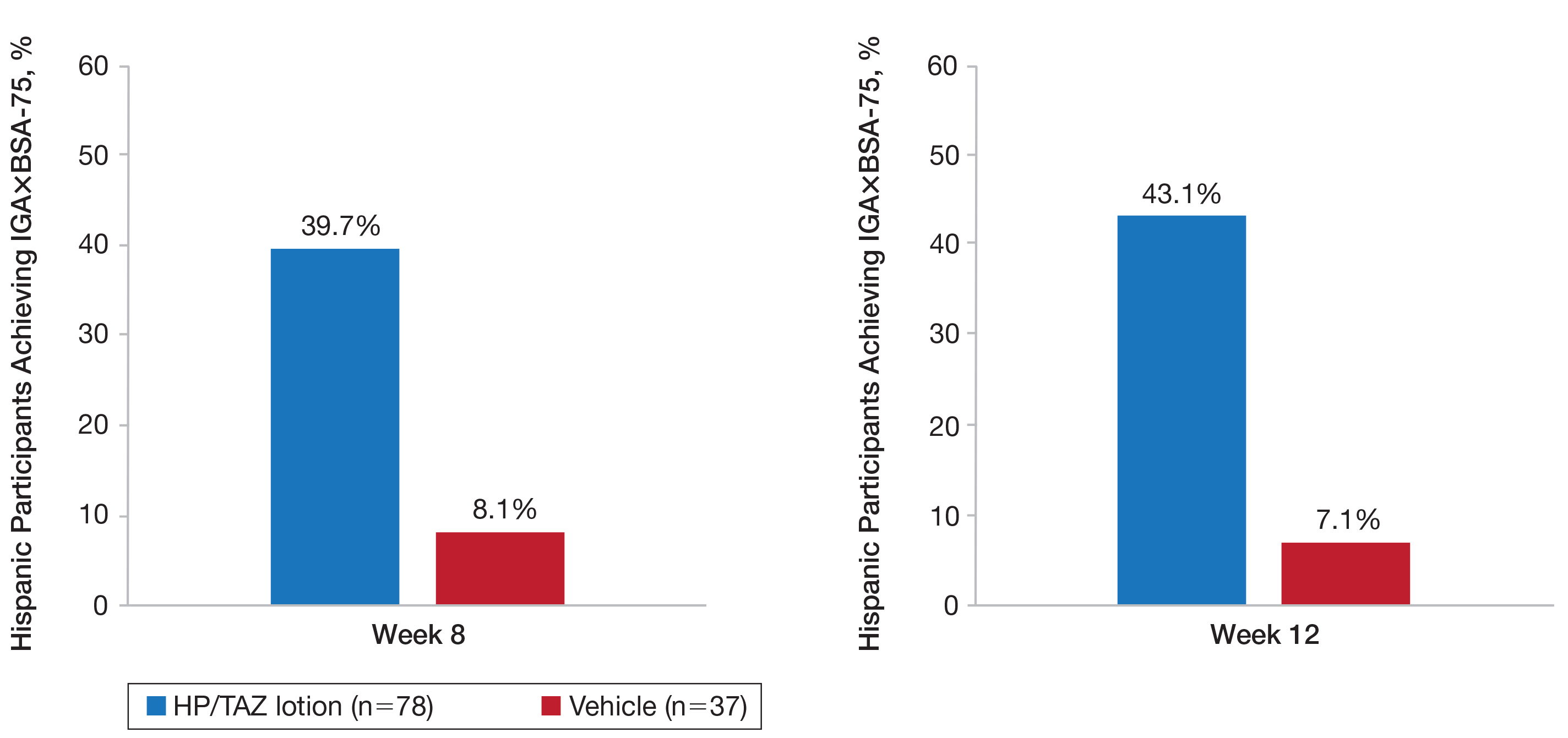

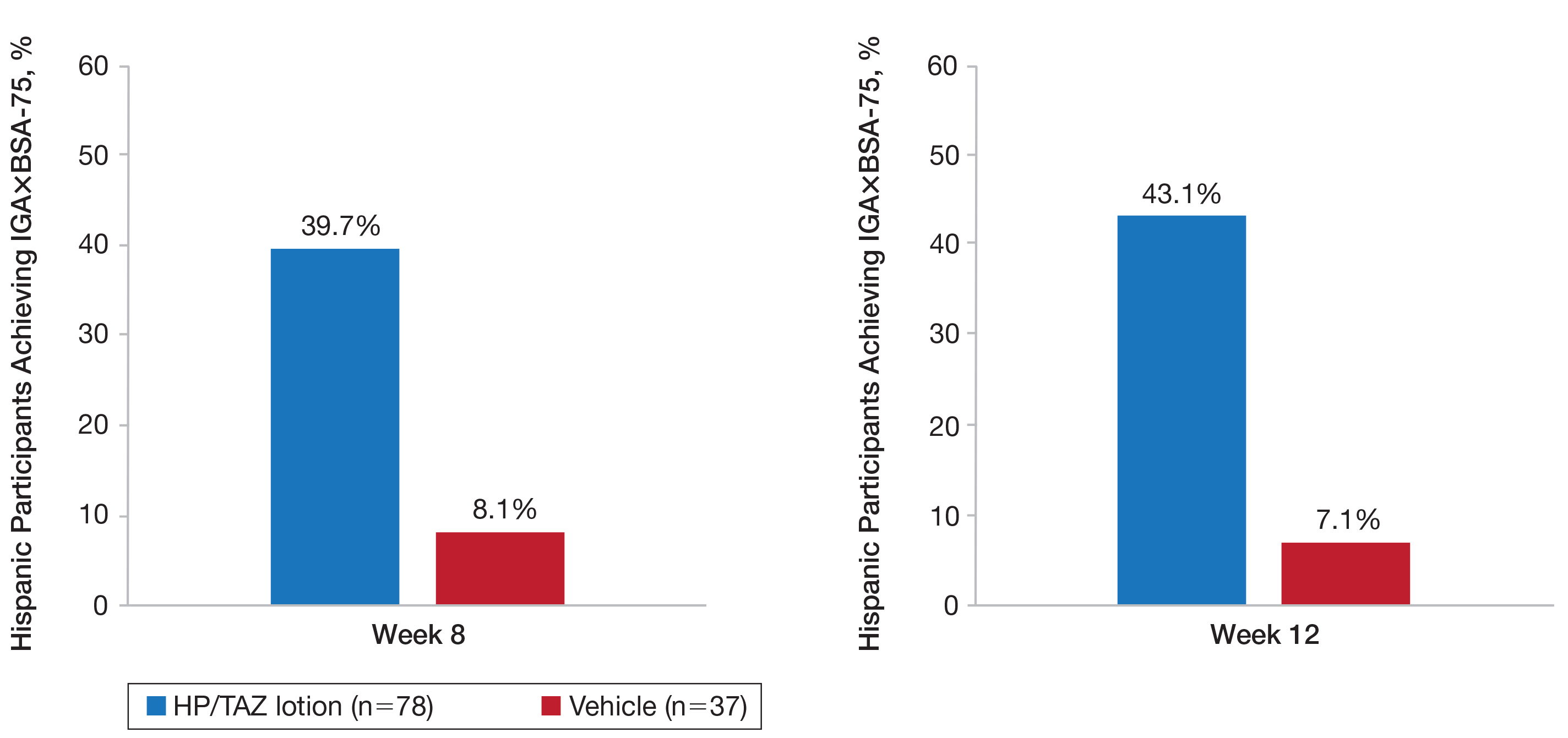

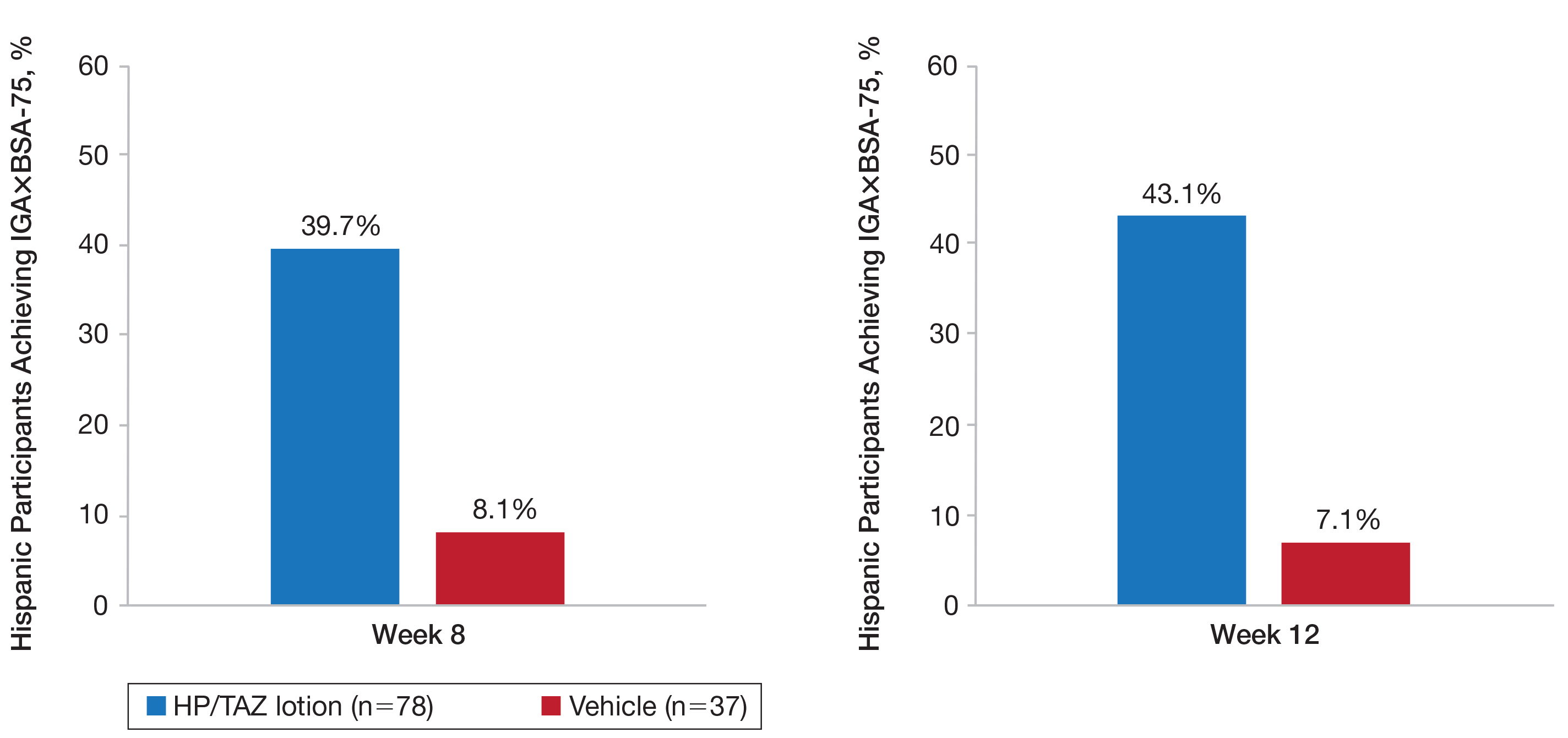

A clinically meaningful effect (IGA×BSA-75) was achieved in 39.7% of Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to 8.1% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001) at week 8. The benefits were significantly different from week 4 and more participants maintained a clinically meaningful effect posttreatment (43.1% vs 7.1%, P<.001)(Figure 5).

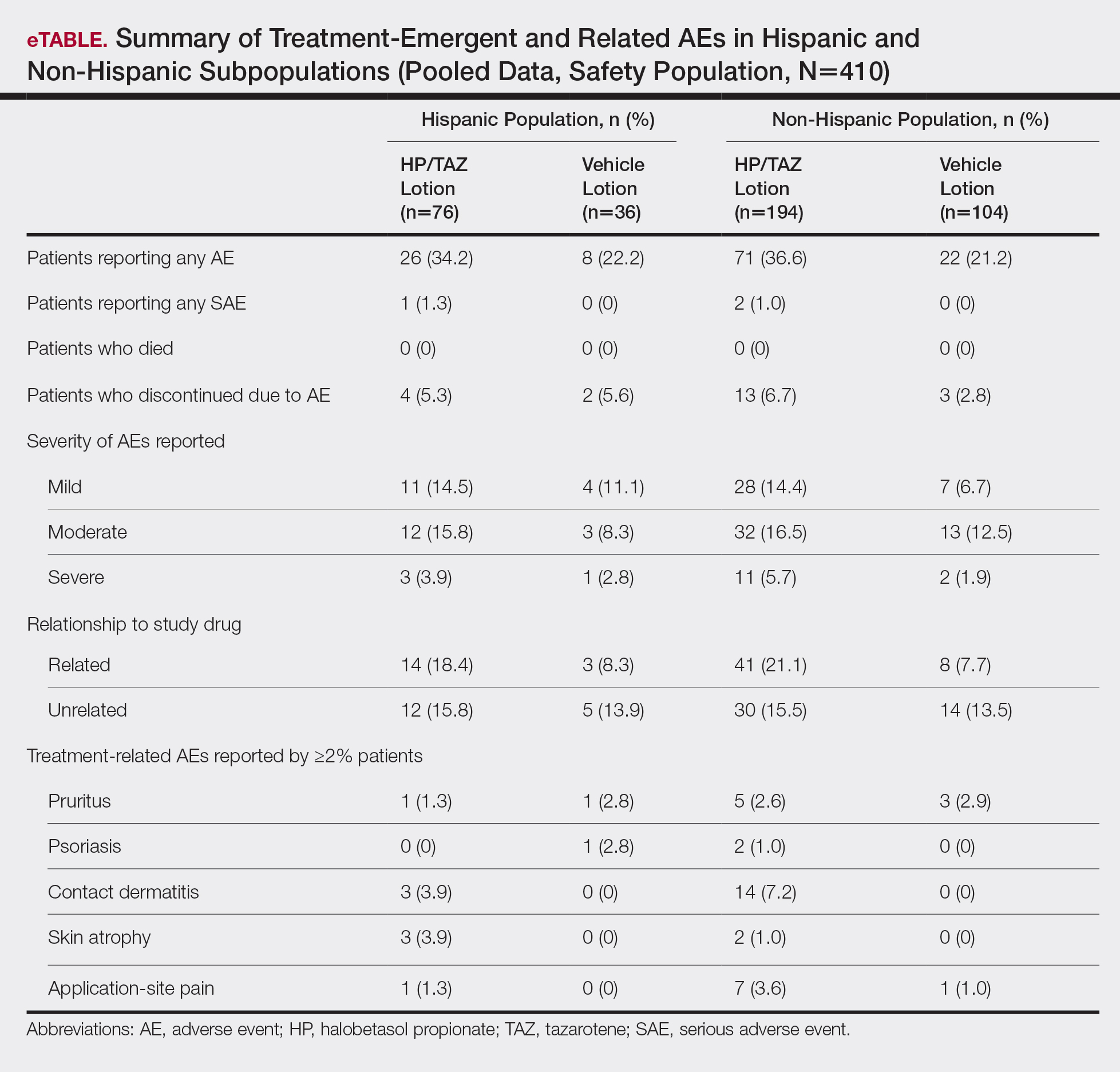

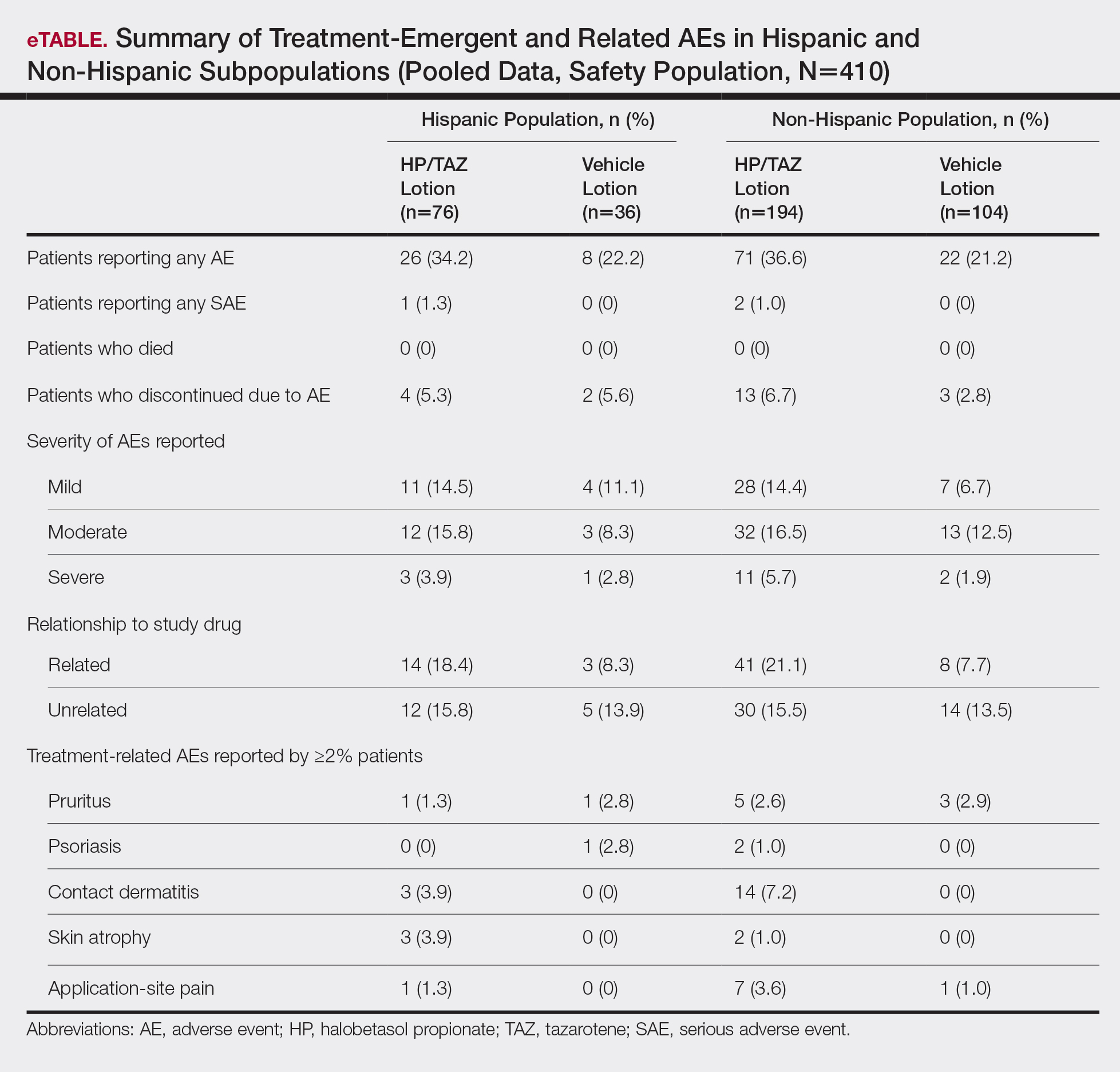

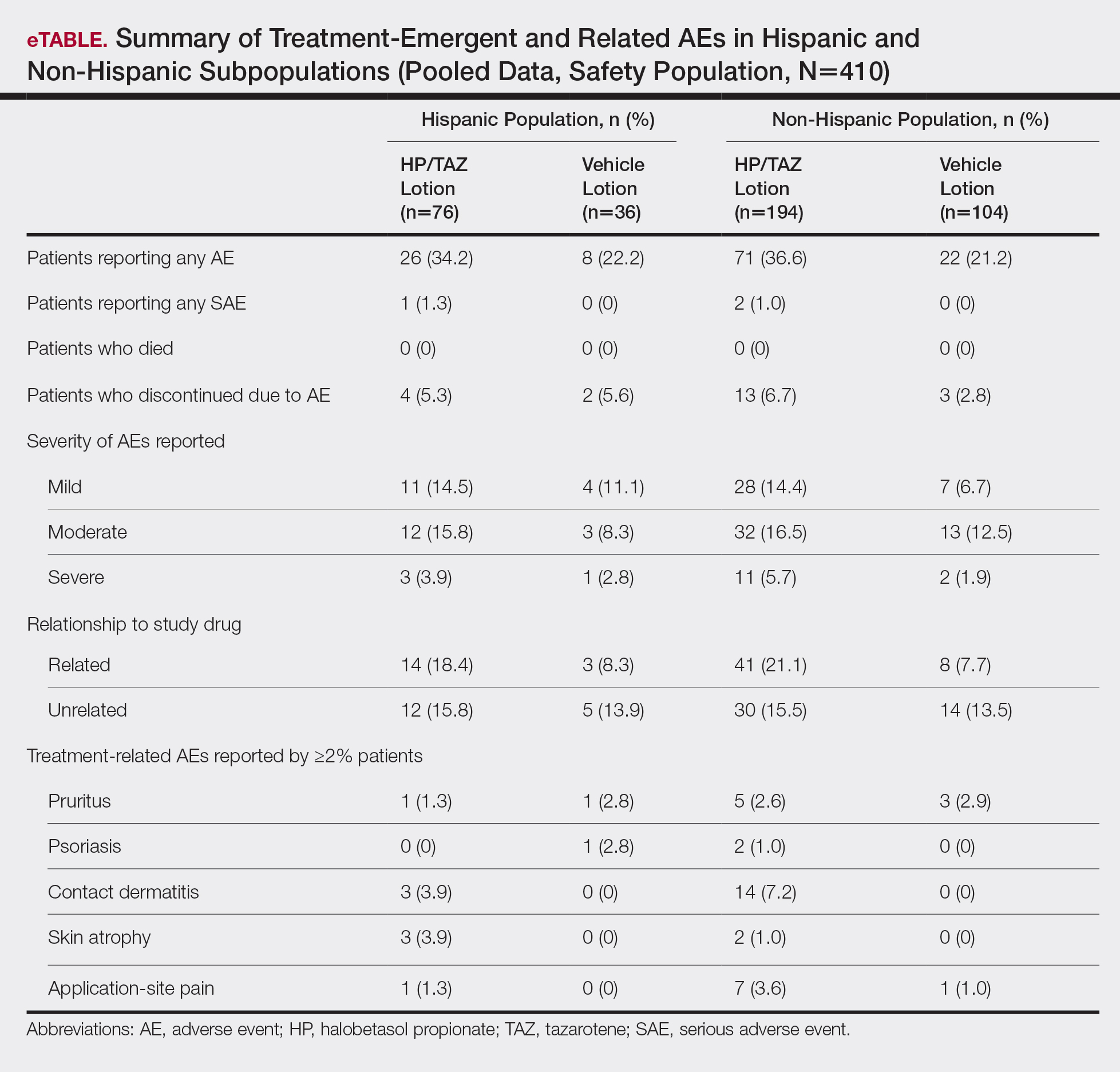

For Hispanic participants overall, 34 participants reported AEs: 26 (34.2%) treated with HP/TAZ lotion and 8 (22.2%) treated with vehicle (eTable). There was 1 (1.3%) serious AE in the HP/TAZ group. Most of the AEs were mild or moderate, with approximately half being related to study treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion were contact dermatitis (n=3, 3.9%) and skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) compared to contact dermatitis (n=14, 7.2%) and application-site pain (n=7, 3.6%) in the non-Hispanic population. Pruritus was the most common AE in Hispanic participants treated with vehicle.

Comment

The large number of Hispanic patients in the 2 phase 3 trials8,9 allowed for this valuable subgroup analysis on the topical treatment of Hispanic patients with plaque psoriasis. Validation of observed differences in maintenance of effect and tolerability warrant further study. Prior clinical studies in psoriasis have tended to enroll a small proportion of Hispanic patients without any post hoc analysis. For example, in a pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials with secukinumab, Hispanic patients accounted for only 16% of the overall population.11 In our analysis, the Hispanic cohort represented 28% of the overall study population of 2 phase 3 studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.8,9 In addition, proportionately more Hispanic patients had severe disease (IGA of 4) or severe signs and symptoms of psoriasis (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) than the non-Hispanic population. This finding supports other studies that have suggested Hispanic patients with psoriasis tend to have more severe disease but also may reflect thresholds for seeking care.3-5

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was significantly more effective than vehicle for all efficacy assessments. In general, efficacy results with HP/TAZ lotion were similar to those reported in the overall phase 3 study populations over the 8-week treatment period. The only noticeable difference was in the posttreatment period. In the overall study population, efficacy was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period in the HP/TAZ group. In the Hispanic subpopulation, there appeared to be continued improvement in the number of participants achieving treatment success (IGA and erythema), clinically meaningful success, and further reductions in BSA. Although there is a paucity of studies evaluating psoriasis therapies in Hispanic populations, data on etanercept and secukinumab have been published.6,11

Onset of effect also is an important aspect of treatment. In patients with skin of color, including patients of Hispanic ethnicity and higher Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, early clearance of lesions may help limit the severity and duration of postinflammatory pigment alteration. Improvements in IGA×BSA scores were significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (P=.016), and a clinically meaningful improvement with HP/TAZ lotion (IGA×BSA-75) was seen by week 4 (P=.024).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was well tolerated, both in the 2 phase 3 studies and in the post hoc analysis of the Hispanic subpopulation. The incidence of skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) was more common vs the non-Hispanic population (n=2, 1.0%). Other common AEs—contact dermatitis, pruritus, and application-site pain—were more common in the non-Hispanic population.

A limitation of our analysis was that it was a post hoc analysis of the Hispanic participants. The phase 3 studies were not designed to specifically study the impact of treatment on ethnicity/race, though the number of Hispanic participants enrolled in the 2 studies was relatively high. The absence of Fitzpatrick skin phototypes in this data set is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt5z21q4k2.

- Abrouk M, Lee K, Brodsky M, et al. Ethnicity affects the presenting severity of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:180-182.

- Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866-872.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Blauvelt A, Green LJ, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy of a once-daily fixed combination halobetasol (0.01%) and tazarotene (0.045%) lotion in the treatment of localized moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:297-299.

- Adsit S, Zaldivar ER, Sofen H, et al. Secukinumab is efficacious and safe in Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1327-1339.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting a diverse patient population, yet epidemiological and clinical data related to psoriasis in patients with skin of color are sparse. The Hispanic ethnic group includes a broad range of skin types and cultures. Prevalence of psoriasis in a Hispanic population has been reported as lower than in a white population1; however, these data may be influenced by the finding that Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when they have skin problems.2 In addition, socioeconomic disparities and cultural variations among racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in access to care and thresholds for seeking care,3 leading to a tendency for more severe disease in skin of color and Hispanic ethnic groups.4,5 Greater impairments in health-related quality of life have been reported in patients with skin of color and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups compared to white patients, independent of psoriasis severity.4,6 Postinflammatory pigment alteration at the sites of resolving lesions, a common clinical feature in skin of color, may contribute to the impact of psoriasis on quality of life in patients with skin of color. Psoriasis in darker skin types also can present diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other papulosquamous disorders and less conspicuous erythema.7

We present a post hoc analysis of the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a novel fixed-combination halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%–tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045% lotion in a Hispanic patient population. Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic patients and other patients with skin of color; in this analysis, the Hispanic population (115/418) represented 28% of the total study population and provided valuable insights.

Methods

Study Design

Two phase 3 randomized controlled trials were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of HP/TAZ lotion. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of moderate or severe localized psoriasis (N=418) were randomized to receive HP/TAZ lotion or vehicle (2:1 ratio) once daily for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up.8,9 A post hoc analysis was conducted on data of the self-identified Hispanic population.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments included treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline in the investigator global assessment [IGA] and a score of clear or almost clear) and impact on individual signs of psoriasis (at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) at the target lesion. In addition, reduction in body surface area (BSA) was recorded, and an IGA×BSA score was calculated by multiplying IGA by BSA at each timepoint for each individual patient. A clinically meaningful improvement in disease severity (percentage of patients achieving a 75% reduction in IGA×BSA [IGA×BSA-75]) also was calculated.

Information on reported and observed adverse events (AEs) was obtained at each visit. The safety population included 112 participants (76 in the HP/TAZ group and 36 in the vehicle group).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical and analytical plan is detailed elsewhere9 and relevant to this post hoc analysis. No statistical analysis was carried out to compare data in the Hispanic population with either the overall study population or the non-Hispanic population.

Results

Overall, 115 Hispanic patients (27.5%) were enrolled (eFigure). Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 46.7 (13.12) years, and more than two-thirds were male (n=80, 69.6%).

Overall completion rates (80.0%) for Hispanic patients were similar to those in the overall study population, though there were more discontinuations in the vehicle group. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation among Hispanic patients were participant request (n=8, 7.0%), lost to follow-up (n=8, 7.0%), and AEs (n=4, 3.5%). Hispanic patients in this study had more severe disease—18.3% (n=21) had an IGA score of 4 compared to 13.5% (n=41) of non-Hispanic patients—and more severe erythema (19.1% vs 9.6%), plaque elevation (20.0% vs 10.2%), and scaling (15.7% vs 12.9%) compared to the non-Hispanic populations (Table).

Efficacy of HP/TAZ lotion in Hispanic patients was similar to the overall study populations,9 though maintenance of effect posttreatment appeared to be better. The incidence of treatment-related AEs also was lower.

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority based on treatment success compared to vehicle as early as week 4 (P=.034). By week 8, 39.3% of participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion achieved treatment success compared to 9.3% of participants in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 1). Treatment success was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period, whereby 40.5% of the HP/TAZ-treated participants were treatment successes at week 12 compared to only 4.1% of participants in the vehicle group (P<.001).

Improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms at the target lesion were statistically significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (plaque elevation, P=.018) or week 4 (erythema, P=.004; scaling, P<.001)(Figure 2). By week 8, 46.8%, 58.1%, and 63.2% of participants showed at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline and were therefore treatment successes for erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling, respectively (all statistically significant [P<.001] compared to vehicle). The number of participants who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema with HP/TAZ lotion increased posttreatment from 46.8% to 53.0%.

Mean (SD) baseline BSA was 6.2 (3.07), and the mean (SD) size of the target lesion was 36.3 (21.85) cm2. Overall, BSA also was significantly reduced in participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to vehicle. At week 8, the mean percentage change from baseline was —40.7% compared to an increase (+10.1%) in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 3). Improvements in BSA were maintained posttreatment, whereas in the vehicle group, mean (SD) BSA had increased to 6.1 (4.64).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion achieved a 50.5% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA by week 8 compared to an 8.5% increase with vehicle (P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in treatment groups were significant from week 2 (P=.016). Efficacy was maintained posttreatment, with a 50.6% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA at week 12 compared to an increase of 13.6% in the vehicle group (P<.001). Again, although results were similar to the overall study population at week 8 (50.5% vs 51.9%), maintenance of effect was better posttreatment (50.6% vs 46.6%).10

A clinically meaningful effect (IGA×BSA-75) was achieved in 39.7% of Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to 8.1% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001) at week 8. The benefits were significantly different from week 4 and more participants maintained a clinically meaningful effect posttreatment (43.1% vs 7.1%, P<.001)(Figure 5).

For Hispanic participants overall, 34 participants reported AEs: 26 (34.2%) treated with HP/TAZ lotion and 8 (22.2%) treated with vehicle (eTable). There was 1 (1.3%) serious AE in the HP/TAZ group. Most of the AEs were mild or moderate, with approximately half being related to study treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion were contact dermatitis (n=3, 3.9%) and skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) compared to contact dermatitis (n=14, 7.2%) and application-site pain (n=7, 3.6%) in the non-Hispanic population. Pruritus was the most common AE in Hispanic participants treated with vehicle.

Comment

The large number of Hispanic patients in the 2 phase 3 trials8,9 allowed for this valuable subgroup analysis on the topical treatment of Hispanic patients with plaque psoriasis. Validation of observed differences in maintenance of effect and tolerability warrant further study. Prior clinical studies in psoriasis have tended to enroll a small proportion of Hispanic patients without any post hoc analysis. For example, in a pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials with secukinumab, Hispanic patients accounted for only 16% of the overall population.11 In our analysis, the Hispanic cohort represented 28% of the overall study population of 2 phase 3 studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.8,9 In addition, proportionately more Hispanic patients had severe disease (IGA of 4) or severe signs and symptoms of psoriasis (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) than the non-Hispanic population. This finding supports other studies that have suggested Hispanic patients with psoriasis tend to have more severe disease but also may reflect thresholds for seeking care.3-5

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was significantly more effective than vehicle for all efficacy assessments. In general, efficacy results with HP/TAZ lotion were similar to those reported in the overall phase 3 study populations over the 8-week treatment period. The only noticeable difference was in the posttreatment period. In the overall study population, efficacy was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period in the HP/TAZ group. In the Hispanic subpopulation, there appeared to be continued improvement in the number of participants achieving treatment success (IGA and erythema), clinically meaningful success, and further reductions in BSA. Although there is a paucity of studies evaluating psoriasis therapies in Hispanic populations, data on etanercept and secukinumab have been published.6,11

Onset of effect also is an important aspect of treatment. In patients with skin of color, including patients of Hispanic ethnicity and higher Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, early clearance of lesions may help limit the severity and duration of postinflammatory pigment alteration. Improvements in IGA×BSA scores were significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (P=.016), and a clinically meaningful improvement with HP/TAZ lotion (IGA×BSA-75) was seen by week 4 (P=.024).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was well tolerated, both in the 2 phase 3 studies and in the post hoc analysis of the Hispanic subpopulation. The incidence of skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) was more common vs the non-Hispanic population (n=2, 1.0%). Other common AEs—contact dermatitis, pruritus, and application-site pain—were more common in the non-Hispanic population.

A limitation of our analysis was that it was a post hoc analysis of the Hispanic participants. The phase 3 studies were not designed to specifically study the impact of treatment on ethnicity/race, though the number of Hispanic participants enrolled in the 2 studies was relatively high. The absence of Fitzpatrick skin phototypes in this data set is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting a diverse patient population, yet epidemiological and clinical data related to psoriasis in patients with skin of color are sparse. The Hispanic ethnic group includes a broad range of skin types and cultures. Prevalence of psoriasis in a Hispanic population has been reported as lower than in a white population1; however, these data may be influenced by the finding that Hispanic patients are less likely to see a dermatologist when they have skin problems.2 In addition, socioeconomic disparities and cultural variations among racial/ethnic groups may contribute to differences in access to care and thresholds for seeking care,3 leading to a tendency for more severe disease in skin of color and Hispanic ethnic groups.4,5 Greater impairments in health-related quality of life have been reported in patients with skin of color and Hispanic racial/ethnic groups compared to white patients, independent of psoriasis severity.4,6 Postinflammatory pigment alteration at the sites of resolving lesions, a common clinical feature in skin of color, may contribute to the impact of psoriasis on quality of life in patients with skin of color. Psoriasis in darker skin types also can present diagnostic challenges due to overlapping features with other papulosquamous disorders and less conspicuous erythema.7

We present a post hoc analysis of the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with a novel fixed-combination halobetasol propionate (HP) 0.01%–tazarotene (TAZ) 0.045% lotion in a Hispanic patient population. Historically, clinical trials for psoriasis have enrolled low proportions of Hispanic patients and other patients with skin of color; in this analysis, the Hispanic population (115/418) represented 28% of the total study population and provided valuable insights.

Methods

Study Design

Two phase 3 randomized controlled trials were conducted to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of HP/TAZ lotion. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of moderate or severe localized psoriasis (N=418) were randomized to receive HP/TAZ lotion or vehicle (2:1 ratio) once daily for 8 weeks with a 4-week posttreatment follow-up.8,9 A post hoc analysis was conducted on data of the self-identified Hispanic population.

Assessments

Efficacy assessments included treatment success (at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline in the investigator global assessment [IGA] and a score of clear or almost clear) and impact on individual signs of psoriasis (at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) at the target lesion. In addition, reduction in body surface area (BSA) was recorded, and an IGA×BSA score was calculated by multiplying IGA by BSA at each timepoint for each individual patient. A clinically meaningful improvement in disease severity (percentage of patients achieving a 75% reduction in IGA×BSA [IGA×BSA-75]) also was calculated.

Information on reported and observed adverse events (AEs) was obtained at each visit. The safety population included 112 participants (76 in the HP/TAZ group and 36 in the vehicle group).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical and analytical plan is detailed elsewhere9 and relevant to this post hoc analysis. No statistical analysis was carried out to compare data in the Hispanic population with either the overall study population or the non-Hispanic population.

Results

Overall, 115 Hispanic patients (27.5%) were enrolled (eFigure). Patients had a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 46.7 (13.12) years, and more than two-thirds were male (n=80, 69.6%).

Overall completion rates (80.0%) for Hispanic patients were similar to those in the overall study population, though there were more discontinuations in the vehicle group. The main reasons for treatment discontinuation among Hispanic patients were participant request (n=8, 7.0%), lost to follow-up (n=8, 7.0%), and AEs (n=4, 3.5%). Hispanic patients in this study had more severe disease—18.3% (n=21) had an IGA score of 4 compared to 13.5% (n=41) of non-Hispanic patients—and more severe erythema (19.1% vs 9.6%), plaque elevation (20.0% vs 10.2%), and scaling (15.7% vs 12.9%) compared to the non-Hispanic populations (Table).

Efficacy of HP/TAZ lotion in Hispanic patients was similar to the overall study populations,9 though maintenance of effect posttreatment appeared to be better. The incidence of treatment-related AEs also was lower.

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion demonstrated statistically significant superiority based on treatment success compared to vehicle as early as week 4 (P=.034). By week 8, 39.3% of participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion achieved treatment success compared to 9.3% of participants in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 1). Treatment success was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period, whereby 40.5% of the HP/TAZ-treated participants were treatment successes at week 12 compared to only 4.1% of participants in the vehicle group (P<.001).

Improvements in psoriasis signs and symptoms at the target lesion were statistically significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (plaque elevation, P=.018) or week 4 (erythema, P=.004; scaling, P<.001)(Figure 2). By week 8, 46.8%, 58.1%, and 63.2% of participants showed at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline and were therefore treatment successes for erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling, respectively (all statistically significant [P<.001] compared to vehicle). The number of participants who achieved at least a 2-grade improvement in erythema with HP/TAZ lotion increased posttreatment from 46.8% to 53.0%.

Mean (SD) baseline BSA was 6.2 (3.07), and the mean (SD) size of the target lesion was 36.3 (21.85) cm2. Overall, BSA also was significantly reduced in participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to vehicle. At week 8, the mean percentage change from baseline was —40.7% compared to an increase (+10.1%) in the vehicle group (P=.002)(Figure 3). Improvements in BSA were maintained posttreatment, whereas in the vehicle group, mean (SD) BSA had increased to 6.1 (4.64).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion achieved a 50.5% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA by week 8 compared to an 8.5% increase with vehicle (P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in treatment groups were significant from week 2 (P=.016). Efficacy was maintained posttreatment, with a 50.6% reduction from baseline IGA×BSA at week 12 compared to an increase of 13.6% in the vehicle group (P<.001). Again, although results were similar to the overall study population at week 8 (50.5% vs 51.9%), maintenance of effect was better posttreatment (50.6% vs 46.6%).10

A clinically meaningful effect (IGA×BSA-75) was achieved in 39.7% of Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion compared to 8.1% of participants treated with vehicle (P<.001) at week 8. The benefits were significantly different from week 4 and more participants maintained a clinically meaningful effect posttreatment (43.1% vs 7.1%, P<.001)(Figure 5).

For Hispanic participants overall, 34 participants reported AEs: 26 (34.2%) treated with HP/TAZ lotion and 8 (22.2%) treated with vehicle (eTable). There was 1 (1.3%) serious AE in the HP/TAZ group. Most of the AEs were mild or moderate, with approximately half being related to study treatment. The most common treatment-related AEs in Hispanic participants treated with HP/TAZ lotion were contact dermatitis (n=3, 3.9%) and skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) compared to contact dermatitis (n=14, 7.2%) and application-site pain (n=7, 3.6%) in the non-Hispanic population. Pruritus was the most common AE in Hispanic participants treated with vehicle.

Comment

The large number of Hispanic patients in the 2 phase 3 trials8,9 allowed for this valuable subgroup analysis on the topical treatment of Hispanic patients with plaque psoriasis. Validation of observed differences in maintenance of effect and tolerability warrant further study. Prior clinical studies in psoriasis have tended to enroll a small proportion of Hispanic patients without any post hoc analysis. For example, in a pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials with secukinumab, Hispanic patients accounted for only 16% of the overall population.11 In our analysis, the Hispanic cohort represented 28% of the overall study population of 2 phase 3 studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of HP/TAZ lotion in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.8,9 In addition, proportionately more Hispanic patients had severe disease (IGA of 4) or severe signs and symptoms of psoriasis (erythema, plaque elevation, and scaling) than the non-Hispanic population. This finding supports other studies that have suggested Hispanic patients with psoriasis tend to have more severe disease but also may reflect thresholds for seeking care.3-5

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was significantly more effective than vehicle for all efficacy assessments. In general, efficacy results with HP/TAZ lotion were similar to those reported in the overall phase 3 study populations over the 8-week treatment period. The only noticeable difference was in the posttreatment period. In the overall study population, efficacy was maintained over the 4-week posttreatment period in the HP/TAZ group. In the Hispanic subpopulation, there appeared to be continued improvement in the number of participants achieving treatment success (IGA and erythema), clinically meaningful success, and further reductions in BSA. Although there is a paucity of studies evaluating psoriasis therapies in Hispanic populations, data on etanercept and secukinumab have been published.6,11

Onset of effect also is an important aspect of treatment. In patients with skin of color, including patients of Hispanic ethnicity and higher Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, early clearance of lesions may help limit the severity and duration of postinflammatory pigment alteration. Improvements in IGA×BSA scores were significant compared to vehicle from week 2 (P=.016), and a clinically meaningful improvement with HP/TAZ lotion (IGA×BSA-75) was seen by week 4 (P=.024).

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was well tolerated, both in the 2 phase 3 studies and in the post hoc analysis of the Hispanic subpopulation. The incidence of skin atrophy (n=3, 3.9%) was more common vs the non-Hispanic population (n=2, 1.0%). Other common AEs—contact dermatitis, pruritus, and application-site pain—were more common in the non-Hispanic population.

A limitation of our analysis was that it was a post hoc analysis of the Hispanic participants. The phase 3 studies were not designed to specifically study the impact of treatment on ethnicity/race, though the number of Hispanic participants enrolled in the 2 studies was relatively high. The absence of Fitzpatrick skin phototypes in this data set is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Halobetasol propionate 0.01%–TAZ 0.045% lotion was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Bulley, MSc (Konic Limited, United Kingdom), for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Ortho Dermatologics funded Konic’s activities pertaining to this manuscript.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt5z21q4k2.

- Abrouk M, Lee K, Brodsky M, et al. Ethnicity affects the presenting severity of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:180-182.

- Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866-872.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Blauvelt A, Green LJ, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy of a once-daily fixed combination halobetasol (0.01%) and tazarotene (0.045%) lotion in the treatment of localized moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:297-299.

- Adsit S, Zaldivar ER, Sofen H, et al. Secukinumab is efficacious and safe in Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1327-1339.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1366-1369.

- Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, et al. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. pii:13030/qt5z21q4k2.

- Abrouk M, Lee K, Brodsky M, et al. Ethnicity affects the presenting severity of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:180-182.

- Shah SK, Arthur A, Yang YC, et al. A retrospective study to investigate racial and ethnic variations in the treatment of psoriasis with etanercept. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:866-872.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Sugarman JL, Weiss J, Tanghetti EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination halobetasol and tazarotene lotion in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:855-861.

- Blauvelt A, Green LJ, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy of a once-daily fixed combination halobetasol (0.01%) and tazarotene (0.045%) lotion in the treatment of localized moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:297-299.

- Adsit S, Zaldivar ER, Sofen H, et al. Secukinumab is efficacious and safe in Hispanic patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: pooled analysis of four phase 3 trials. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1327-1339.

Practice Points

- Although psoriasis is a common inflammatory disease, data in the Hispanic population are sparse and disease may be more severe.

- A recent clinical investigation with halobetasol propionate 0.01%–tazarotene 0.045% lotion included a number of Hispanic patients, affording an ideal opportunity to provide important data on this population.

- This fixed-combination therapy was associated with significant, rapid, and sustained reductions in disease severity in a Hispanic population with moderate to severe psoriasis that continued to show improvement posttreatment with good tolerability and safety.

Why Is Skin Cancer Mortality Higher in Patients With Skin of Color?

Skin Cancer Mortality in Patients With Skin of Color

Skin cancers in patients with skin of color are less prevalent but have a higher morbidity and mortality compared to white patients. Challenges to early detection, including clinical differences in presentation, low public awareness, lower index of suspicion among health care providers, and access to specialty care, likely contribute to observed differences in prognosis between skin of color and white populations.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, accounting for approximately 40% of all neoplasms in white patients but only 1% to 4% in Asian American and black patients.1,2 Largely due to the photoprotective effects of increased constitutive epidermal melanin, melanoma is approximately 10 to 20 times less frequent in black patients and 3 to 7 times less common in Hispanics than age-matched whites.1 Nonmelanoma skin cancers including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma also are less prevalent in darker skin types.3,4

In the United States, Hispanic, American Indian

Similar to melanoma, the mortality from SCC is disproportionately increased in skin of color populations, ranging from 18% to 29% in black patients.3,10,11 There is a paucity of population-based studies in the United States looking at mortality rates of nonmelanoma skin cancers and their trends over time, but a 1993 study suggests that mortality rates are declining less consistently in black patients than white patients.11

Factors that may contribute to higher mortality rates in patients with skin of color include a greater propensity for inherently aggressive skin cancers (eg, higher risk of SCC) and delays in diagnosis (eg, late-stage diagnosis of melanoma).1,4 For melanoma, increased mortality has been attributed to a predominance of acral lentiginous melanomas, which are more frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages than other melanoma subtypes.6,12,13 Black patients, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to present with thicker tumors and metastases on initial presentation than their white counterparts (P<.001).2,8,9,12-14 The higher risk of death from SCC results from the predominance of lesions on non–sun-exposed areas, particularly the legs and anogenital areas, and within sites of chronic scarring or inflammation.4 Unlike sun-induced SCC, the most commonly observed type of SCC in lighter skin types, SCCs that develop in association with chronic inflammatory or ulcerative processes are aggressive and invasive, and they metastasize to distant sites in 20% to 40% of cases (versus 1%–4% in sun-induced SCC).1,3,4 For all skin cancers, poor access to medical care, patients’ unawareness of their skin cancer risk, lack of adequate skin examinations, and prevalence of lesions on uncommon sites that may be inconspicuous or overlooked have all been suggested to delay diagnosis.1,15,16 Given that more advanced disease is associated with worse outcomes, the implications of this delay are enormous and remain a cause for concern.

The alarming skin cancer mortality rates in patients with skin of color are a call to action for the medical community. The consistent use of full-body skin examinations including close inspection of mucosal, acral, and genital areas for all patients independent of skin type and racial/ethnic background is paramount. Advancing skin cancer education in skin of color populations, such as through distribution of patient-directed educational materials produced by organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin Cancer Foundation, and Skin of Color Society, is an important step toward increased public awareness.16 Use of social and traditional media outlets as well as community-directed health outreach campaigns also are important strategies to change the common misconception that darker-skinned individuals do not get skin cancer. We hope that with a multipronged approach, disparities in skin cancer mortality will steadily be eliminated.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760; quiz 761-764.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Mora RG, Perniciaro C. Cancer of the skin in blacks: I. a review of 163 black patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:535-543.

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Updated September 12, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2017.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Chen L, Jin S. Trends in mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma in East Asian populations. Peer J. 2014;4:e2809.

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California Cancer Registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252.

- Johnson DS, Yamane S, Morita S, et al. Malignant melanoma in non-Caucasians: experience from Hawaii. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:275-282.

- Fleming ID, Barnawell JR, Burlison PE, et al. Skin cancer in black patients. Cancer. 1975;35:600-605.

- Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality in the United States, 1969 through 1988. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1286-1290.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:142-143.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Black WC, Goldhahn RT, Wiggins C. Melanoma within a southwestern Hispanic population. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1331-1334.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, et al. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda [published online August 29, 2016]. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:4635740.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

Skin cancers in patients with skin of color are less prevalent but have a higher morbidity and mortality compared to white patients. Challenges to early detection, including clinical differences in presentation, low public awareness, lower index of suspicion among health care providers, and access to specialty care, likely contribute to observed differences in prognosis between skin of color and white populations.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, accounting for approximately 40% of all neoplasms in white patients but only 1% to 4% in Asian American and black patients.1,2 Largely due to the photoprotective effects of increased constitutive epidermal melanin, melanoma is approximately 10 to 20 times less frequent in black patients and 3 to 7 times less common in Hispanics than age-matched whites.1 Nonmelanoma skin cancers including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma also are less prevalent in darker skin types.3,4

In the United States, Hispanic, American Indian

Similar to melanoma, the mortality from SCC is disproportionately increased in skin of color populations, ranging from 18% to 29% in black patients.3,10,11 There is a paucity of population-based studies in the United States looking at mortality rates of nonmelanoma skin cancers and their trends over time, but a 1993 study suggests that mortality rates are declining less consistently in black patients than white patients.11

Factors that may contribute to higher mortality rates in patients with skin of color include a greater propensity for inherently aggressive skin cancers (eg, higher risk of SCC) and delays in diagnosis (eg, late-stage diagnosis of melanoma).1,4 For melanoma, increased mortality has been attributed to a predominance of acral lentiginous melanomas, which are more frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages than other melanoma subtypes.6,12,13 Black patients, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to present with thicker tumors and metastases on initial presentation than their white counterparts (P<.001).2,8,9,12-14 The higher risk of death from SCC results from the predominance of lesions on non–sun-exposed areas, particularly the legs and anogenital areas, and within sites of chronic scarring or inflammation.4 Unlike sun-induced SCC, the most commonly observed type of SCC in lighter skin types, SCCs that develop in association with chronic inflammatory or ulcerative processes are aggressive and invasive, and they metastasize to distant sites in 20% to 40% of cases (versus 1%–4% in sun-induced SCC).1,3,4 For all skin cancers, poor access to medical care, patients’ unawareness of their skin cancer risk, lack of adequate skin examinations, and prevalence of lesions on uncommon sites that may be inconspicuous or overlooked have all been suggested to delay diagnosis.1,15,16 Given that more advanced disease is associated with worse outcomes, the implications of this delay are enormous and remain a cause for concern.

The alarming skin cancer mortality rates in patients with skin of color are a call to action for the medical community. The consistent use of full-body skin examinations including close inspection of mucosal, acral, and genital areas for all patients independent of skin type and racial/ethnic background is paramount. Advancing skin cancer education in skin of color populations, such as through distribution of patient-directed educational materials produced by organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin Cancer Foundation, and Skin of Color Society, is an important step toward increased public awareness.16 Use of social and traditional media outlets as well as community-directed health outreach campaigns also are important strategies to change the common misconception that darker-skinned individuals do not get skin cancer. We hope that with a multipronged approach, disparities in skin cancer mortality will steadily be eliminated.

Skin cancers in patients with skin of color are less prevalent but have a higher morbidity and mortality compared to white patients. Challenges to early detection, including clinical differences in presentation, low public awareness, lower index of suspicion among health care providers, and access to specialty care, likely contribute to observed differences in prognosis between skin of color and white populations.

Skin cancer is the most common malignancy in the United States, accounting for approximately 40% of all neoplasms in white patients but only 1% to 4% in Asian American and black patients.1,2 Largely due to the photoprotective effects of increased constitutive epidermal melanin, melanoma is approximately 10 to 20 times less frequent in black patients and 3 to 7 times less common in Hispanics than age-matched whites.1 Nonmelanoma skin cancers including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and basal cell carcinoma also are less prevalent in darker skin types.3,4

In the United States, Hispanic, American Indian

Similar to melanoma, the mortality from SCC is disproportionately increased in skin of color populations, ranging from 18% to 29% in black patients.3,10,11 There is a paucity of population-based studies in the United States looking at mortality rates of nonmelanoma skin cancers and their trends over time, but a 1993 study suggests that mortality rates are declining less consistently in black patients than white patients.11

Factors that may contribute to higher mortality rates in patients with skin of color include a greater propensity for inherently aggressive skin cancers (eg, higher risk of SCC) and delays in diagnosis (eg, late-stage diagnosis of melanoma).1,4 For melanoma, increased mortality has been attributed to a predominance of acral lentiginous melanomas, which are more frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages than other melanoma subtypes.6,12,13 Black patients, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders are all more likely to present with thicker tumors and metastases on initial presentation than their white counterparts (P<.001).2,8,9,12-14 The higher risk of death from SCC results from the predominance of lesions on non–sun-exposed areas, particularly the legs and anogenital areas, and within sites of chronic scarring or inflammation.4 Unlike sun-induced SCC, the most commonly observed type of SCC in lighter skin types, SCCs that develop in association with chronic inflammatory or ulcerative processes are aggressive and invasive, and they metastasize to distant sites in 20% to 40% of cases (versus 1%–4% in sun-induced SCC).1,3,4 For all skin cancers, poor access to medical care, patients’ unawareness of their skin cancer risk, lack of adequate skin examinations, and prevalence of lesions on uncommon sites that may be inconspicuous or overlooked have all been suggested to delay diagnosis.1,15,16 Given that more advanced disease is associated with worse outcomes, the implications of this delay are enormous and remain a cause for concern.

The alarming skin cancer mortality rates in patients with skin of color are a call to action for the medical community. The consistent use of full-body skin examinations including close inspection of mucosal, acral, and genital areas for all patients independent of skin type and racial/ethnic background is paramount. Advancing skin cancer education in skin of color populations, such as through distribution of patient-directed educational materials produced by organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, Skin Cancer Foundation, and Skin of Color Society, is an important step toward increased public awareness.16 Use of social and traditional media outlets as well as community-directed health outreach campaigns also are important strategies to change the common misconception that darker-skinned individuals do not get skin cancer. We hope that with a multipronged approach, disparities in skin cancer mortality will steadily be eliminated.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760; quiz 761-764.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Mora RG, Perniciaro C. Cancer of the skin in blacks: I. a review of 163 black patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:535-543.

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Updated September 12, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2017.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Chen L, Jin S. Trends in mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma in East Asian populations. Peer J. 2014;4:e2809.

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California Cancer Registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252.

- Johnson DS, Yamane S, Morita S, et al. Malignant melanoma in non-Caucasians: experience from Hawaii. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:275-282.

- Fleming ID, Barnawell JR, Burlison PE, et al. Skin cancer in black patients. Cancer. 1975;35:600-605.

- Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality in the United States, 1969 through 1988. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1286-1290.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:142-143.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Black WC, Goldhahn RT, Wiggins C. Melanoma within a southwestern Hispanic population. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1331-1334.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, et al. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda [published online August 29, 2016]. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:4635740.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

- Gloster HM Jr, Neal K. Skin cancer in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:741-760; quiz 761-764.

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914.

- Mora RG, Perniciaro C. Cancer of the skin in blacks: I. a review of 163 black patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:535-543.

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; April 2016. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/. Updated September 12, 2016. Accessed April 7, 2017.

- Bellows CF, Belafsky P, Fortgang IS, et al. Melanoma in African-Americans: trends in biological behavior and clinical characteristics over two decades. J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:10-16.

- Chen L, Jin S. Trends in mortality rates of cutaneous melanoma in East Asian populations. Peer J. 2014;4:e2809.

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California Cancer Registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252.

- Johnson DS, Yamane S, Morita S, et al. Malignant melanoma in non-Caucasians: experience from Hawaii. Surg Clin N Am. 2003;83:275-282.

- Fleming ID, Barnawell JR, Burlison PE, et al. Skin cancer in black patients. Cancer. 1975;35:600-605.

- Weinstock MA. Nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality in the United States, 1969 through 1988. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1286-1290.

- Byrd KM, Wilson DC, Hoyler SS. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:142-143.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Black WC, Goldhahn RT, Wiggins C. Melanoma within a southwestern Hispanic population. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1331-1334.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, et al. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda [published online August 29, 2016]. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:4635740.

- Robinson JK, Joshi KM, Ortiz S, et al. Melanoma knowledge, perception, and awareness in ethnic minorities in Chicago: recommendations regarding education. Psychooncology. 2011;20:313-320.

Lasers for Darker Skin Types

Laser Best Practices for Darker Skin Types

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

How Common Is Psoriasis in Patients With Skin of Color?

The prevalence of psoriasis in individuals with skin of color is lower than in white individuals, but a number of clinical differences can complicate diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis in patients with darker skin types. Dr. Andrew Alexis discusses some clinical features that may be unique to those with skin of color, including association with persistent pigmentary alterations, as well as special considerations and treatment approaches for psoriasis in darker-skinned patients.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Suggested Reading

Report on the psycho-social impacts of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation Web site. Published in 2009. https://www.psoriasis.org/Document.DOC?id=619. Accessed June 15, 2015.

The prevalence of psoriasis in individuals with skin of color is lower than in white individuals, but a number of clinical differences can complicate diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis in patients with darker skin types. Dr. Andrew Alexis discusses some clinical features that may be unique to those with skin of color, including association with persistent pigmentary alterations, as well as special considerations and treatment approaches for psoriasis in darker-skinned patients.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

The prevalence of psoriasis in individuals with skin of color is lower than in white individuals, but a number of clinical differences can complicate diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis in patients with darker skin types. Dr. Andrew Alexis discusses some clinical features that may be unique to those with skin of color, including association with persistent pigmentary alterations, as well as special considerations and treatment approaches for psoriasis in darker-skinned patients.

The psoriasis audiocast series is created in collaboration with Cutis® and the National Psoriasis Foundation®.

Suggested Reading

Report on the psycho-social impacts of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation Web site. Published in 2009. https://www.psoriasis.org/Document.DOC?id=619. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Suggested Reading

Report on the psycho-social impacts of psoriasis. National Psoriasis Foundation Web site. Published in 2009. https://www.psoriasis.org/Document.DOC?id=619. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Nonablative Lasers for Acne Scarring in Darker Skin Types

For more information, read Dr. Alexis' editorial from the December 2013 issue, "Laser Resurfacing for Treatment of Acne Scarring in Fitzpatrick Skin Types V to VI: Practical Approaches to Maximizing Safety."

For more information, read Dr. Alexis' editorial from the December 2013 issue, "Laser Resurfacing for Treatment of Acne Scarring in Fitzpatrick Skin Types V to VI: Practical Approaches to Maximizing Safety."

For more information, read Dr. Alexis' editorial from the December 2013 issue, "Laser Resurfacing for Treatment of Acne Scarring in Fitzpatrick Skin Types V to VI: Practical Approaches to Maximizing Safety."

Laser Resurfacing for Treatment of Acne Scarring in Fitzpatrick Skin Types V to VI: Practical Approaches to Maximizing Safety

Test your knowledge on laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI with MD-IQ: the medical intelligence quiz. Click here to answer 5 questions.