User login

Jeff Evans has been editor of Rheumatology News/MDedge Rheumatology and the EULAR Congress News since 2013. He started at Frontline Medical Communications in 2001 and was a reporter for 8 years before serving as editor of Clinical Neurology News and World Neurology, and briefly as editor of GI & Hepatology News. He graduated cum laude from Cornell University (New York) with a BA in biological sciences, concentrating in neurobiology and behavior.

Home infusion policies called out in ACR position statement

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Proper administration of intravenous biologics should take place under the close supervision of a physician in a physician’s office, infusion center, or hospital rather than in a patient’s home in order to address potential infusion reactions that can range from mild to life threatening, according to a position statement issued by the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care.

The “Patient Safety and Site of Service for Infusible Biologics” statement, issued in late February, comes in opposition to “policies that require home infusion” that appear to seek potential cost savings with home infusions rather than meet the standard of care with on-site physician supervision.

“One observation made by some but not all payers is that infusible biologics are about twice as expensive when infused in a hospital-based infusion center as compared to other locations, such as a clinic-based infusion center or the patient’s home. Thus, some payers are rolling out policies designed to shift patients from hospital-based infusion centers to less expensive sites. The ACR is opposed to policies that would force patients, solely for the purpose of cost containment, to receive infusible biologics in an improperly supervised setting. The purpose of the position statement is to outline that stance,” Dr. Douglas W. White, chair of the ACR’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care, said in an interview.

He noted that he’s “been in on conversations with two payers who are implementing policies to move patients away from hospital-based infusions, but we are aware that others are in various stages of implementing such policies, too. It’s not so much an issue of critical mass for us, rather we’re just trying to keep ahead of the trends, and we think this will be a big trend.”

The potential for adverse reactions is not uncommon during intravenous administration of biologics, the committee wrote, noting, for example, that 10% of patients given infliximab have acute infusion reactions. On-site physicians such as rheumatologists who have experience with the “tremendous heterogeneity of patients with autoimmune disease and the diversity of conditions treated with biologics” can determine the severity of infusion reactions and decide whether or not it is safe to continue a particular biologic agent, in addition to providing reassurance to patients during acute and potentially severe reactions, according to the ACR statement.

Infusion reactions can range in severity from a mild rash to life-threatening anaphylaxis that can involve multiple organ systems leading to respiratory and cardiovascular collapse and requiring immediate treatment with medications such as epinephrine or intravenous glucocorticoids.

The position statement recognizes unusual situations in which home infusion is necessary for a patient to receive treatment because of transportation problems to a medical facility or comorbid conditions in which the risk of no treatment may outweigh the risk of home infusion. In these circumstances, the ACR “encourages providers in such unusual and difficult situations to make the best medical decision based on the individual needs of the patient. Routine home infusion of biologics is considered an unnecessary and dangerous risk to patients and violates our current clinical standards of practice.”

Requirements for using home infusion also threaten “to reduce access to” intravenous biologics, the ACR contends, because “specially trained physicians are less likely to prescribe treatments that are not properly administered in the safest clinical setting [and] patient fear of biologic therapy may lead to noncompliance and inadequate control of disease.”

The ACR noted that home administration of subcutaneous biologics is medically appropriate and the injection site reactions that can occur with their use are often easily managed.

Antisclerostin osteoporosis drugs might worsen or unmask rheumatoid arthritis

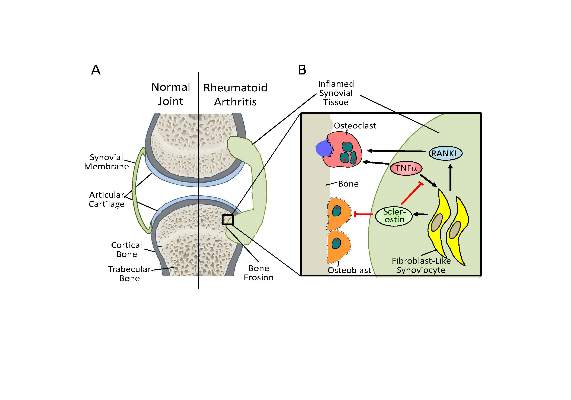

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

Antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies have shown their ability to increase bone density in phase II and III trials of men and women with osteoporosis but could potentially have the opposite effect in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other chronic inflammatory diseases in which tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) plays an important role, according to new research.

The new work, conducted by Corinna Wehmeyer, Ph.D., of the Institute of Experimental Musculoskeletal Medicine at University Hospital Muenster (Germany) and her colleagues, shows that the bone formation–inhibiting protein sclerostin is not expressed in bone only, as was previously thought, but is also expressed on the synovial cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Dr. Wehmeyer and her associates were surprised to find that inhibiting sclerostin in a human TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of RA actually accelerated joint damage rather than prevented it, suggesting that sclerostin actually had a protective role in the presence of chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation. They confirmed this by demonstrating that sclerostin inhibited TNF-alpha signaling in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and showing that blocking sclerostin caused less or little worsening of bone erosions in mouse models of RA that are more dependent on a robust T and B cell response accompanied by high cytokine expression within the joint, rather than damage driven by TNF-alpha.

“These findings strongly suggest that in chronic TNF-alpha–mediated inflammation, sclerostin expression is upregulated as part of an attempt to reestablish bone homeostasis, where it exerts protective functions,” the authors wrote (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4351).

The research needs confirmation in humans with RA and potentially in other chronic inflammatory diseases in which TNF-alpha plays an important role. “Nevertheless, the preliminary data in three different models indicate that sclerostin antibody therapy could be contraindicated in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent inflammatory conditions. The possibility of adverse pathological effects means that caution should be taken both when considering such treatment in RA or in patients with chronic TNF-alpha–dependent comorbidities. Thus, to translate these findings to patients, first strategies to use sclerostin inhibition should exclude inflammatory comorbidities and very thoroughly monitor inflammatory events in patients to which such therapies are applied,” the researchers advised.

In an editorial, Dr. Frank Rauch of McGill University, Montreal, and Dr. Rick Adachi of the department of rheumatology at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., wrote that antisclerostin “treatment might accelerate joint destruction, at least when the inflammatory process is not quelled first. Patients with established RA usually undergo anti-inflammatory treatment, and it is unclear whether sclerostin inactivation would be detrimental in this context. Mouse data suggest that antisclerostin treatment might bring about regression of bone erosions when combined with TNF-alpha inhibition. The new work mirrors the situation of patients who have unrecognized RA while on antisclerostin therapy or who develop RA while receiving this treatment” (Sci Transl Med. 2016 Mar 16;8:330fs7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf4628).

Antisclerostin antibodies in trials

Trials of the antisclerostin monoclonal antibodies romosozumab and blosozumab have been successful in treating postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis.

Romosozumab codevelopers UCB and Amgen reported that the biologic agent significantly reduced the rate of new vertebral fractures by 73% versus placebo at 12 months in the randomized, double-blind phase III FRAME (Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis) study. In the 7,180-patient trial, the reduction was 75% versus placebo at 24 months after both treatment groups had been transitioned to denosumab given every 6 months in the second year of treatment. Romosozumab also significantly lowered the relative risk of clinical fractures (composite of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures) by 36% at 12 months, but the difference was not statistically significant at 24 months.

In the initial 12-month treatment period, the most commonly reported adverse events in both arms (greater than 10%) were arthralgia, nasopharyngitis, and back pain. There were no differences in the proportions of patients who reported hearing loss or worsening of knee osteoarthritis. There were two positively adjudicated events of osteonecrosis of the jaw in the romosozumab treatment group, one after completing romosozumab dosing and the other after completing romosozumab treatment and receiving the initial dose of denosumab. There was one positively adjudicated event of atypical femoral fracture after 3 months of romosozumab treatment.

Phase III results from the 244-patient BRIDGE (Placebo-Controlled Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Romosozumab in Treating Men With Osteoporosis) trial found a significant increase in bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at 12 months, which was the study’s primary endpoint. Other significant increases in femoral neck and total hip BMD were detected at 12 months. Cardiovascular severe adverse events occurred in 4.9% of men on romosozumab and 2.5% on placebo, including death in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively. At least 5% or more of patients who received romosozumab reported nasopharyngitis, back pain, hypertension, headache, and constipation. About 5% of patients who received romosozumab in each trial had injection-site reactions, most of which were mild.

A phase II trial of blosozumab in 120 postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density (mean lumbar spine T-score –2.8) showed that the drug increased BMD in the lumbar spine by 17.7% above baseline at 52 weeks, femoral neck by 8.4%, and total hip by 6.2%, compared with decreases of 1.6%, 0.6%, and 0.7%, respectively, with placebo (J Bone Miner Res. 2015 Feb;30[2]:216-24). However, mild injection-site reactions were reported by up to 40% of women taking blosozumab, and 35% developed antidrug antibodies after exposure to blosozumab. Eli Lilly, its developer, is looking at possible ways to reformulate the drug before it moves to phase III.

The study in Science Translational Medicine was supported by the German Research Foundation. The authors had no competing interests to disclose.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

ACR’s 2016-2020 research agenda built through consensus

Therapeutic goals set the tone for the American College of Rheumatology National Research Agenda 2016-2020 by calling for the discovery and development of new therapies for rheumatic disease; finding predictors of response and nonresponse to, and adverse events from therapy; and improving the understanding of how therapies should be used.

Those are the top 3 out of 15 goals facilitated by the ACR’s Committee on Research, which finalized the agenda after seeking input from members of the ACR and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ARHP) living in the United States, and going through several rounds of refining and prioritizing the importance of goals through the input of clinicians, researchers, patients, and stakeholders. The Committee on Research uses the agenda to “set the compass for the organization in terms of research initiatives and facilitate the ACR’s advocacy for the research goals identified.”

Dr. Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, who jointly led the development of the agenda for the Committee on Research along with Dr. S. Louis Bridges, said that while the goals for 2016-2020 had a great deal of overlap with those of 2011-2015, “some of the topics that came up were different. Some of the topics were more specific than in the previous agenda. We have some idea how important these issues were to rheumatologists, given that rheumatologists (and patients) rated the importance of the items. Defining new therapeutic targets and developing new therapies for rheumatic diseases was by far the most highly rated goal by rheumatologists. Next most highly rated was to advocate for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators – this was included as a supplementary goal that supports the rest of the agenda. Other newer items were those around determining how the changing health care landscape affects rheumatology patients and clinicians. In addition, nonpharmacologic therapy, adult outcomes of pediatric disease, and optimizing patient engagement were topics that were felt to be important. I think these highlight the input of clinicians in identifying research objectives.”

The 2016-2020 agenda is the third set of goals developed by the committee since 2005, and the first to “crowdsource” the important questions to ACR and ARHP members rather than be assembled solely by the committee.

The agenda arose from a multistage process that began with a web-based survey to the ACR/ARHP membership that asked respondents to “list the five most important research questions that need to be addressed over the next 5 years in order to improve the care for patients with rheumatic disease.” A selected group of 100 individuals representing patients, clinicians (academic and community), research (all types with diverse areas/diseases of interest), allied health professionals, pediatric and adult rheumatology, men and women, all career stages, and all regions of the country, used a Delphi exercise to rate 30 statements generated from the survey on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important). They had the option to provide comments. At a Leadership Summit, stakeholders from various nonprofit foundations associated with rheumatic diseases, the National Institutes of Health, and the president of the Rheumatology Research Foundation gave comments on a draft agenda to the Committee on Research, after which the committee discussed the results and input and then solicited further 1-10 ratings and comments on preliminary agenda goals from the same group of 100 individuals as in the second phase, plus an additional 17 clinicians.

Up next in the rank-ordering after therapeutic goals were three goals about understanding:

• The etiology, pathogenesis, and genetic basis of rheumatic diseases.

• Early disease states to improve early diagnosis, develop biomarkers for early detection, and determine how earlier treatment changes outcomes.

• The immune system and autoimmunity by defining autoimmunity triggers and determining how epigenetics affect disease susceptibility and inflammation.

The 5-year plan proposed developing improved outcome measures that incorporate patient self-reports, imaging, and measures of clinical response and disease activity. The agenda also seeks to gain better understanding of how patients with rheumatic disease, rheumatologists, and rheumatology health professionals are being affected by the changing U.S. health care landscape.

The plan calls for determining the role of nonpharmacologic therapy in the management of rheumatic disease (promoting and improving adherence to physical activity, finding optimal exercise prescriptions, and determining the role of diet on disease activity), as well as evaluating the role of regenerative medicine.

The agenda spells out the need for better engagement of patients in their care as well as for understanding how comorbidities are influenced by rheumatic disease and how pain and fatigue arise in rheumatic disease.

In two separate goals, committee members listed the importance of determining adult outcomes of pediatric rheumatic diseases and the effect of aging on the development, progression, and management of rheumatic diseases.

The Committee on Research identified three supplemental goals that support the others:

• Advocating for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators.

• Harmonizing data from existing cohorts and registries to optimize research capabilities.

• Improving patient research partner involvement in research protocols.

Therapeutic goals set the tone for the American College of Rheumatology National Research Agenda 2016-2020 by calling for the discovery and development of new therapies for rheumatic disease; finding predictors of response and nonresponse to, and adverse events from therapy; and improving the understanding of how therapies should be used.

Those are the top 3 out of 15 goals facilitated by the ACR’s Committee on Research, which finalized the agenda after seeking input from members of the ACR and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ARHP) living in the United States, and going through several rounds of refining and prioritizing the importance of goals through the input of clinicians, researchers, patients, and stakeholders. The Committee on Research uses the agenda to “set the compass for the organization in terms of research initiatives and facilitate the ACR’s advocacy for the research goals identified.”

Dr. Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, who jointly led the development of the agenda for the Committee on Research along with Dr. S. Louis Bridges, said that while the goals for 2016-2020 had a great deal of overlap with those of 2011-2015, “some of the topics that came up were different. Some of the topics were more specific than in the previous agenda. We have some idea how important these issues were to rheumatologists, given that rheumatologists (and patients) rated the importance of the items. Defining new therapeutic targets and developing new therapies for rheumatic diseases was by far the most highly rated goal by rheumatologists. Next most highly rated was to advocate for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators – this was included as a supplementary goal that supports the rest of the agenda. Other newer items were those around determining how the changing health care landscape affects rheumatology patients and clinicians. In addition, nonpharmacologic therapy, adult outcomes of pediatric disease, and optimizing patient engagement were topics that were felt to be important. I think these highlight the input of clinicians in identifying research objectives.”

The 2016-2020 agenda is the third set of goals developed by the committee since 2005, and the first to “crowdsource” the important questions to ACR and ARHP members rather than be assembled solely by the committee.

The agenda arose from a multistage process that began with a web-based survey to the ACR/ARHP membership that asked respondents to “list the five most important research questions that need to be addressed over the next 5 years in order to improve the care for patients with rheumatic disease.” A selected group of 100 individuals representing patients, clinicians (academic and community), research (all types with diverse areas/diseases of interest), allied health professionals, pediatric and adult rheumatology, men and women, all career stages, and all regions of the country, used a Delphi exercise to rate 30 statements generated from the survey on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important). They had the option to provide comments. At a Leadership Summit, stakeholders from various nonprofit foundations associated with rheumatic diseases, the National Institutes of Health, and the president of the Rheumatology Research Foundation gave comments on a draft agenda to the Committee on Research, after which the committee discussed the results and input and then solicited further 1-10 ratings and comments on preliminary agenda goals from the same group of 100 individuals as in the second phase, plus an additional 17 clinicians.

Up next in the rank-ordering after therapeutic goals were three goals about understanding:

• The etiology, pathogenesis, and genetic basis of rheumatic diseases.

• Early disease states to improve early diagnosis, develop biomarkers for early detection, and determine how earlier treatment changes outcomes.

• The immune system and autoimmunity by defining autoimmunity triggers and determining how epigenetics affect disease susceptibility and inflammation.

The 5-year plan proposed developing improved outcome measures that incorporate patient self-reports, imaging, and measures of clinical response and disease activity. The agenda also seeks to gain better understanding of how patients with rheumatic disease, rheumatologists, and rheumatology health professionals are being affected by the changing U.S. health care landscape.

The plan calls for determining the role of nonpharmacologic therapy in the management of rheumatic disease (promoting and improving adherence to physical activity, finding optimal exercise prescriptions, and determining the role of diet on disease activity), as well as evaluating the role of regenerative medicine.

The agenda spells out the need for better engagement of patients in their care as well as for understanding how comorbidities are influenced by rheumatic disease and how pain and fatigue arise in rheumatic disease.

In two separate goals, committee members listed the importance of determining adult outcomes of pediatric rheumatic diseases and the effect of aging on the development, progression, and management of rheumatic diseases.

The Committee on Research identified three supplemental goals that support the others:

• Advocating for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators.

• Harmonizing data from existing cohorts and registries to optimize research capabilities.

• Improving patient research partner involvement in research protocols.

Therapeutic goals set the tone for the American College of Rheumatology National Research Agenda 2016-2020 by calling for the discovery and development of new therapies for rheumatic disease; finding predictors of response and nonresponse to, and adverse events from therapy; and improving the understanding of how therapies should be used.

Those are the top 3 out of 15 goals facilitated by the ACR’s Committee on Research, which finalized the agenda after seeking input from members of the ACR and Association of Rheumatology Health Professionals (ARHP) living in the United States, and going through several rounds of refining and prioritizing the importance of goals through the input of clinicians, researchers, patients, and stakeholders. The Committee on Research uses the agenda to “set the compass for the organization in terms of research initiatives and facilitate the ACR’s advocacy for the research goals identified.”

Dr. Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, who jointly led the development of the agenda for the Committee on Research along with Dr. S. Louis Bridges, said that while the goals for 2016-2020 had a great deal of overlap with those of 2011-2015, “some of the topics that came up were different. Some of the topics were more specific than in the previous agenda. We have some idea how important these issues were to rheumatologists, given that rheumatologists (and patients) rated the importance of the items. Defining new therapeutic targets and developing new therapies for rheumatic diseases was by far the most highly rated goal by rheumatologists. Next most highly rated was to advocate for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators – this was included as a supplementary goal that supports the rest of the agenda. Other newer items were those around determining how the changing health care landscape affects rheumatology patients and clinicians. In addition, nonpharmacologic therapy, adult outcomes of pediatric disease, and optimizing patient engagement were topics that were felt to be important. I think these highlight the input of clinicians in identifying research objectives.”

The 2016-2020 agenda is the third set of goals developed by the committee since 2005, and the first to “crowdsource” the important questions to ACR and ARHP members rather than be assembled solely by the committee.

The agenda arose from a multistage process that began with a web-based survey to the ACR/ARHP membership that asked respondents to “list the five most important research questions that need to be addressed over the next 5 years in order to improve the care for patients with rheumatic disease.” A selected group of 100 individuals representing patients, clinicians (academic and community), research (all types with diverse areas/diseases of interest), allied health professionals, pediatric and adult rheumatology, men and women, all career stages, and all regions of the country, used a Delphi exercise to rate 30 statements generated from the survey on a scale from 1 (not important) to 10 (very important). They had the option to provide comments. At a Leadership Summit, stakeholders from various nonprofit foundations associated with rheumatic diseases, the National Institutes of Health, and the president of the Rheumatology Research Foundation gave comments on a draft agenda to the Committee on Research, after which the committee discussed the results and input and then solicited further 1-10 ratings and comments on preliminary agenda goals from the same group of 100 individuals as in the second phase, plus an additional 17 clinicians.

Up next in the rank-ordering after therapeutic goals were three goals about understanding:

• The etiology, pathogenesis, and genetic basis of rheumatic diseases.

• Early disease states to improve early diagnosis, develop biomarkers for early detection, and determine how earlier treatment changes outcomes.

• The immune system and autoimmunity by defining autoimmunity triggers and determining how epigenetics affect disease susceptibility and inflammation.

The 5-year plan proposed developing improved outcome measures that incorporate patient self-reports, imaging, and measures of clinical response and disease activity. The agenda also seeks to gain better understanding of how patients with rheumatic disease, rheumatologists, and rheumatology health professionals are being affected by the changing U.S. health care landscape.

The plan calls for determining the role of nonpharmacologic therapy in the management of rheumatic disease (promoting and improving adherence to physical activity, finding optimal exercise prescriptions, and determining the role of diet on disease activity), as well as evaluating the role of regenerative medicine.

The agenda spells out the need for better engagement of patients in their care as well as for understanding how comorbidities are influenced by rheumatic disease and how pain and fatigue arise in rheumatic disease.

In two separate goals, committee members listed the importance of determining adult outcomes of pediatric rheumatic diseases and the effect of aging on the development, progression, and management of rheumatic diseases.

The Committee on Research identified three supplemental goals that support the others:

• Advocating for increased support for rheumatology research and rheumatology investigators.

• Harmonizing data from existing cohorts and registries to optimize research capabilities.

• Improving patient research partner involvement in research protocols.

Registry study adds evidence for use of DMARD combo first in early RA

A treat-to-target protocol involving methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine, along with an optional intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide injection, led to remission more quickly in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis than did initial methotrexate monotherapy in a registry study comparing two separate cohorts.

The study found that 71.9% (92/128) of patients in the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) registry in a first multicenter cohort of methotrexate monotherapy that began in 2006 met remission criteria at 1 year of follow-up, based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) less than 2.6, which was not statistically different from 77.3% (99/128) in a second multicenter cohort of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) combination therapy that began in 2012. However, at 6 months, a significantly higher percentage of the second cohort achieved a first remission, compared with the first cohort (63.3% vs. 48.4%). The median time to first remission also was significantly shorter among members of the second cohort (17 weeks vs. 27 weeks).

The first author of the study, Laura M.M. Steunebrink of Medisch Spectrum Twente hospital, Enschede, The Netherlands, and her colleagues noted that “in the United States, methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine is by far the DMARD combination most commonly prescribed by rheumatologists. It has been shown to be more potent than methotrexate used alone. An explanation for this may be that hydroxychloroquine increases the bioavailability of methotrexate and/or reduces the clearance of the drug.”

The patients in both cohorts had RA symptoms for less than 1 year and a DAS28 greater than 2.6. The patients in the second cohort were matched with patients in the first cohort on gender, age, and baseline disease activity, although patients in the second cohort had 1 more tender joint (median of 4 vs. 3), higher DAS28 using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mean of 4.8 vs. 4.5), and worse scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, pain visual analog scale, and mental component of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Remission rates in other treat-to-target studies in patients with recent-onset RA, using different criteria for remission and slightly different follow-up periods, have ranged from 10% to 78%. In accordance with the results from these previous randomized clinical trials, “the implementation of a [treat-to-target] protocol may in itself explain the high remission rates in both cohorts, [but] apparently even better results may be attained regarding the time needed to achieve first remission by implementing initial combination protocols in daily clinical practice,” the authors wrote (Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:60. doi:10.1186/s13075-016-0962-9).

One of the main differences in protocols between the two cohorts was the starting and step-up doses of methotrexate. In the first cohort, methotrexate monotherapy started at 15 mg/week, with folic acid taken on the second day after methotrexate. When patients had DAS28 of 2.6 or greater at 2 months, methotrexate increased to 25 mg/week, and after 3 months, sulfasalazine 2,000 mg/day was added and then increased to 3,000 mg/day after 20 weeks. Anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNF-alpha) treatment was prescribed at week 24 for patients whose DAS28 remained at 3.2 or higher, replacing sulfasalazine with subcutaneous adalimumab (Humira) 40 mg every 2 weeks with an escalation at week 36 to 40 mg/week for those with DAS28 of 2.6 or greater.

Patients who continued to have a DAS28 of 3.2 or higher at week 52 exchanged adalimumab for etanercept (Enbrel) 50 mg/week. The attending rheumatologist used discretion in permitting concomitant treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prednisolone at 10 mg/day or less, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

Patients in the second cohort started on methotrexate 20 mg/week and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, with an optional intramuscular triamcinolone injection to a maximum dosage of 120 mg as bridging therapy. Clinicians increased methotrexate to 25 mg/week after 1 month, regardless of disease activity. Folic acid was started on the second day after methotrexate. Methotrexate increased to 30 mg/week when there was a DAS28 of 2.6 or greater at 2 months, and an extra optional intramuscular triamcinolone injection could be administered. The attending rheumatologist added a TNF inhibitor (adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab [Remicade]) at 4 months if DAS28 remained at 3.2 or higher. Patients in whom DAS28 remained between 2.6 and 3.2 at 4 months could receive either sulfasalazine 2,000-3,000 mg/day or an intramuscular triamcinolone injection.

In both cohorts, if at any time point the target of DAS28 less than 2.6 was met, medication was held constant. In case of sustained remission of 6 months or longer, medication was gradually reduced and eventually discontinued. Patients restarted their last effective medication or increased their dose if disease flared – defined as a DAS28 of 2.6 or greater. The attending rheumatologist was free to diverge from the medication schedule at any time based on clinical indication.

Most patients in both cohorts achieved the treatment target using only conventional synthetic DMARDs at 12 months (91% in first cohort and 81% in second), and a small number of the patients in both cohorts were using biologic DMARDs at 12 months (4% in first cohort and 9% in second). Slightly more than half (53%) of patients in the second cohort received an intramuscular injection with triamcinolone, compared with just 3% in the first cohort, and its use was associated with more than a doubling of the odds of achieving first remission within 6 months (odds ratio, 2.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-4.4; P = .04). However, it did not affect the odds of remission at 12 months.

“Although we did not conduct a randomized trial, we still think that the design and results of the study allow us to compare the two cohorts. The cohorts consist of very similar populations of all consecutive newly diagnosed patients with RA treated in the same hospitals by the same rheumatologists,” the authors wrote. “Because in our study we used real-life observational data, the results are generalizable to daily clinical practice.”

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

A treat-to-target protocol involving methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine, along with an optional intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide injection, led to remission more quickly in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis than did initial methotrexate monotherapy in a registry study comparing two separate cohorts.

The study found that 71.9% (92/128) of patients in the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) registry in a first multicenter cohort of methotrexate monotherapy that began in 2006 met remission criteria at 1 year of follow-up, based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) less than 2.6, which was not statistically different from 77.3% (99/128) in a second multicenter cohort of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) combination therapy that began in 2012. However, at 6 months, a significantly higher percentage of the second cohort achieved a first remission, compared with the first cohort (63.3% vs. 48.4%). The median time to first remission also was significantly shorter among members of the second cohort (17 weeks vs. 27 weeks).

The first author of the study, Laura M.M. Steunebrink of Medisch Spectrum Twente hospital, Enschede, The Netherlands, and her colleagues noted that “in the United States, methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine is by far the DMARD combination most commonly prescribed by rheumatologists. It has been shown to be more potent than methotrexate used alone. An explanation for this may be that hydroxychloroquine increases the bioavailability of methotrexate and/or reduces the clearance of the drug.”

The patients in both cohorts had RA symptoms for less than 1 year and a DAS28 greater than 2.6. The patients in the second cohort were matched with patients in the first cohort on gender, age, and baseline disease activity, although patients in the second cohort had 1 more tender joint (median of 4 vs. 3), higher DAS28 using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mean of 4.8 vs. 4.5), and worse scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, pain visual analog scale, and mental component of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Remission rates in other treat-to-target studies in patients with recent-onset RA, using different criteria for remission and slightly different follow-up periods, have ranged from 10% to 78%. In accordance with the results from these previous randomized clinical trials, “the implementation of a [treat-to-target] protocol may in itself explain the high remission rates in both cohorts, [but] apparently even better results may be attained regarding the time needed to achieve first remission by implementing initial combination protocols in daily clinical practice,” the authors wrote (Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:60. doi:10.1186/s13075-016-0962-9).

One of the main differences in protocols between the two cohorts was the starting and step-up doses of methotrexate. In the first cohort, methotrexate monotherapy started at 15 mg/week, with folic acid taken on the second day after methotrexate. When patients had DAS28 of 2.6 or greater at 2 months, methotrexate increased to 25 mg/week, and after 3 months, sulfasalazine 2,000 mg/day was added and then increased to 3,000 mg/day after 20 weeks. Anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNF-alpha) treatment was prescribed at week 24 for patients whose DAS28 remained at 3.2 or higher, replacing sulfasalazine with subcutaneous adalimumab (Humira) 40 mg every 2 weeks with an escalation at week 36 to 40 mg/week for those with DAS28 of 2.6 or greater.

Patients who continued to have a DAS28 of 3.2 or higher at week 52 exchanged adalimumab for etanercept (Enbrel) 50 mg/week. The attending rheumatologist used discretion in permitting concomitant treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prednisolone at 10 mg/day or less, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

Patients in the second cohort started on methotrexate 20 mg/week and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, with an optional intramuscular triamcinolone injection to a maximum dosage of 120 mg as bridging therapy. Clinicians increased methotrexate to 25 mg/week after 1 month, regardless of disease activity. Folic acid was started on the second day after methotrexate. Methotrexate increased to 30 mg/week when there was a DAS28 of 2.6 or greater at 2 months, and an extra optional intramuscular triamcinolone injection could be administered. The attending rheumatologist added a TNF inhibitor (adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab [Remicade]) at 4 months if DAS28 remained at 3.2 or higher. Patients in whom DAS28 remained between 2.6 and 3.2 at 4 months could receive either sulfasalazine 2,000-3,000 mg/day or an intramuscular triamcinolone injection.

In both cohorts, if at any time point the target of DAS28 less than 2.6 was met, medication was held constant. In case of sustained remission of 6 months or longer, medication was gradually reduced and eventually discontinued. Patients restarted their last effective medication or increased their dose if disease flared – defined as a DAS28 of 2.6 or greater. The attending rheumatologist was free to diverge from the medication schedule at any time based on clinical indication.

Most patients in both cohorts achieved the treatment target using only conventional synthetic DMARDs at 12 months (91% in first cohort and 81% in second), and a small number of the patients in both cohorts were using biologic DMARDs at 12 months (4% in first cohort and 9% in second). Slightly more than half (53%) of patients in the second cohort received an intramuscular injection with triamcinolone, compared with just 3% in the first cohort, and its use was associated with more than a doubling of the odds of achieving first remission within 6 months (odds ratio, 2.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-4.4; P = .04). However, it did not affect the odds of remission at 12 months.

“Although we did not conduct a randomized trial, we still think that the design and results of the study allow us to compare the two cohorts. The cohorts consist of very similar populations of all consecutive newly diagnosed patients with RA treated in the same hospitals by the same rheumatologists,” the authors wrote. “Because in our study we used real-life observational data, the results are generalizable to daily clinical practice.”

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

A treat-to-target protocol involving methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine, along with an optional intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide injection, led to remission more quickly in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis than did initial methotrexate monotherapy in a registry study comparing two separate cohorts.

The study found that 71.9% (92/128) of patients in the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring (DREAM) registry in a first multicenter cohort of methotrexate monotherapy that began in 2006 met remission criteria at 1 year of follow-up, based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) less than 2.6, which was not statistically different from 77.3% (99/128) in a second multicenter cohort of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) combination therapy that began in 2012. However, at 6 months, a significantly higher percentage of the second cohort achieved a first remission, compared with the first cohort (63.3% vs. 48.4%). The median time to first remission also was significantly shorter among members of the second cohort (17 weeks vs. 27 weeks).

The first author of the study, Laura M.M. Steunebrink of Medisch Spectrum Twente hospital, Enschede, The Netherlands, and her colleagues noted that “in the United States, methotrexate plus hydroxychloroquine is by far the DMARD combination most commonly prescribed by rheumatologists. It has been shown to be more potent than methotrexate used alone. An explanation for this may be that hydroxychloroquine increases the bioavailability of methotrexate and/or reduces the clearance of the drug.”

The patients in both cohorts had RA symptoms for less than 1 year and a DAS28 greater than 2.6. The patients in the second cohort were matched with patients in the first cohort on gender, age, and baseline disease activity, although patients in the second cohort had 1 more tender joint (median of 4 vs. 3), higher DAS28 using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mean of 4.8 vs. 4.5), and worse scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, pain visual analog scale, and mental component of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Remission rates in other treat-to-target studies in patients with recent-onset RA, using different criteria for remission and slightly different follow-up periods, have ranged from 10% to 78%. In accordance with the results from these previous randomized clinical trials, “the implementation of a [treat-to-target] protocol may in itself explain the high remission rates in both cohorts, [but] apparently even better results may be attained regarding the time needed to achieve first remission by implementing initial combination protocols in daily clinical practice,” the authors wrote (Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:60. doi:10.1186/s13075-016-0962-9).

One of the main differences in protocols between the two cohorts was the starting and step-up doses of methotrexate. In the first cohort, methotrexate monotherapy started at 15 mg/week, with folic acid taken on the second day after methotrexate. When patients had DAS28 of 2.6 or greater at 2 months, methotrexate increased to 25 mg/week, and after 3 months, sulfasalazine 2,000 mg/day was added and then increased to 3,000 mg/day after 20 weeks. Anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha (anti-TNF-alpha) treatment was prescribed at week 24 for patients whose DAS28 remained at 3.2 or higher, replacing sulfasalazine with subcutaneous adalimumab (Humira) 40 mg every 2 weeks with an escalation at week 36 to 40 mg/week for those with DAS28 of 2.6 or greater.

Patients who continued to have a DAS28 of 3.2 or higher at week 52 exchanged adalimumab for etanercept (Enbrel) 50 mg/week. The attending rheumatologist used discretion in permitting concomitant treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, prednisolone at 10 mg/day or less, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

Patients in the second cohort started on methotrexate 20 mg/week and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, with an optional intramuscular triamcinolone injection to a maximum dosage of 120 mg as bridging therapy. Clinicians increased methotrexate to 25 mg/week after 1 month, regardless of disease activity. Folic acid was started on the second day after methotrexate. Methotrexate increased to 30 mg/week when there was a DAS28 of 2.6 or greater at 2 months, and an extra optional intramuscular triamcinolone injection could be administered. The attending rheumatologist added a TNF inhibitor (adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab [Remicade]) at 4 months if DAS28 remained at 3.2 or higher. Patients in whom DAS28 remained between 2.6 and 3.2 at 4 months could receive either sulfasalazine 2,000-3,000 mg/day or an intramuscular triamcinolone injection.

In both cohorts, if at any time point the target of DAS28 less than 2.6 was met, medication was held constant. In case of sustained remission of 6 months or longer, medication was gradually reduced and eventually discontinued. Patients restarted their last effective medication or increased their dose if disease flared – defined as a DAS28 of 2.6 or greater. The attending rheumatologist was free to diverge from the medication schedule at any time based on clinical indication.

Most patients in both cohorts achieved the treatment target using only conventional synthetic DMARDs at 12 months (91% in first cohort and 81% in second), and a small number of the patients in both cohorts were using biologic DMARDs at 12 months (4% in first cohort and 9% in second). Slightly more than half (53%) of patients in the second cohort received an intramuscular injection with triamcinolone, compared with just 3% in the first cohort, and its use was associated with more than a doubling of the odds of achieving first remission within 6 months (odds ratio, 2.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-4.4; P = .04). However, it did not affect the odds of remission at 12 months.

“Although we did not conduct a randomized trial, we still think that the design and results of the study allow us to compare the two cohorts. The cohorts consist of very similar populations of all consecutive newly diagnosed patients with RA treated in the same hospitals by the same rheumatologists,” the authors wrote. “Because in our study we used real-life observational data, the results are generalizable to daily clinical practice.”

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

FROM ARTHRITIS RESEARCH & THERAPY

Key clinical point: A treat-to-target strategy that uses combination DMARD therapy for early RA provides the quickest time to first remission.

Major finding: At 6 months, a significantly higher percentage of the second cohort achieved a first remission, compared with the first cohort (63.3% vs. 48.4%).

Data source: A comparison of two separate observational cohorts from the DREAM registry.

Disclosures: The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Once-daily tofacitinib formulation gets FDA clearance for RA

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a once-daily, extended-release tablet formulation of tofacitinib 11 mg, the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, announced.

The Janus kinase inhibitor, to be marketed as Xeljanz XR, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to methotrexate, but it can be used with methotrexate.

“The availability of Xeljanz XR provides physicians with a new treatment option for people with RA who may prefer an oral once-daily treatment,” Dr. Roy Fleischmann, clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in Pfizer’s announcement.

The original 5-mg tofacitinib tablet, approved in 2012, is taken twice daily.

According to Pfizer, the global clinical development program for tofacitinib has evaluated its safety and efficacy in approximately 6,200 patients with moderate to severe RA, amounting to more than 19,400 patient-years of drug exposure.

The new labeling can be found here.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a once-daily, extended-release tablet formulation of tofacitinib 11 mg, the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, announced.

The Janus kinase inhibitor, to be marketed as Xeljanz XR, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to methotrexate, but it can be used with methotrexate.

“The availability of Xeljanz XR provides physicians with a new treatment option for people with RA who may prefer an oral once-daily treatment,” Dr. Roy Fleischmann, clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in Pfizer’s announcement.

The original 5-mg tofacitinib tablet, approved in 2012, is taken twice daily.

According to Pfizer, the global clinical development program for tofacitinib has evaluated its safety and efficacy in approximately 6,200 patients with moderate to severe RA, amounting to more than 19,400 patient-years of drug exposure.

The new labeling can be found here.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a once-daily, extended-release tablet formulation of tofacitinib 11 mg, the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, announced.

The Janus kinase inhibitor, to be marketed as Xeljanz XR, is indicated for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to methotrexate, but it can be used with methotrexate.

“The availability of Xeljanz XR provides physicians with a new treatment option for people with RA who may prefer an oral once-daily treatment,” Dr. Roy Fleischmann, clinical professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in Pfizer’s announcement.

The original 5-mg tofacitinib tablet, approved in 2012, is taken twice daily.

According to Pfizer, the global clinical development program for tofacitinib has evaluated its safety and efficacy in approximately 6,200 patients with moderate to severe RA, amounting to more than 19,400 patient-years of drug exposure.

The new labeling can be found here.

Anticancer drug bexarotene inhibits build-up of toxic Alzheimer’s protein

Bexarotene, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat skin cancer, stopped the primary nucleation step in the self-assembly of amyloid-beta-42 oligomers and delayed the formation of pathogenic aggregates that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease neurodegeneration using a unique strategy that could potentially identify other anti-Alzheimer’s drugs.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge (England), Lund (Sweden) University, and the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), also found that bexarotene (Targretin) blocked the build-up of toxic amyloid-beta-42 (Ab42) aggregates as well as motility dysfunction in a nematode worm model (Caenorhabditis elegans) of Ab42-mediated toxicity (Sci Adv. 2016 Feb;2:e1501244. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501244).

The researchers used a drug discovery strategy to screen a large set of drugs known to interact with amyloid-beta for molecules that could block the primary nucleation of Ab42 aggregates by analyzing the effects that the drugs had on Ab42’s formation into aggregates. This allowed them to determine potential drug candidates’ mechanism for preventing the build-up of toxic Ab42 aggregates.

Earlier animal studies of bexarotene had suggested that the drug could actually reverse Alzheimer’s symptoms by clearing Ab42 aggregates in the brain. But those earlier results, which were later called into question, were based on a completely different mode of action – the clearance of aggregates – than the one reported in the current study. Bexarotene was tested earlier in an unsuccessful 1-month, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, but this new research suggests that the drug may need to be given very early in the disease.

“We anticipate that the strategy that we have described in this paper will enable the identification of further compounds capable of inhibiting Ab42 aggregation and the definition of the specific microscopic steps affected by each compound (that is, primary or secondary nucleation or elongation),” the researchers wrote. “The results described in the present work indicate that bexarotene and other inhibitors of primary nucleation have the potential to be efficient means of delaying aggregation by reducing the probability that primary nuclei are formed and proliferate, such that our natural protection mechanisms could remain effective to more advanced ages. Indeed, we draw an analogy between the strategy presented here and that of using statins, which reduce the level of cholesterol and thus the risk of heart conditions, and suggest that such molecules could effectively act as ‘neurostatins.’ ”

The research was supported by the Centre for Misfolding Diseases at the University of Cambridge. The authors said they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Bexarotene, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat skin cancer, stopped the primary nucleation step in the self-assembly of amyloid-beta-42 oligomers and delayed the formation of pathogenic aggregates that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease neurodegeneration using a unique strategy that could potentially identify other anti-Alzheimer’s drugs.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge (England), Lund (Sweden) University, and the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), also found that bexarotene (Targretin) blocked the build-up of toxic amyloid-beta-42 (Ab42) aggregates as well as motility dysfunction in a nematode worm model (Caenorhabditis elegans) of Ab42-mediated toxicity (Sci Adv. 2016 Feb;2:e1501244. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501244).

The researchers used a drug discovery strategy to screen a large set of drugs known to interact with amyloid-beta for molecules that could block the primary nucleation of Ab42 aggregates by analyzing the effects that the drugs had on Ab42’s formation into aggregates. This allowed them to determine potential drug candidates’ mechanism for preventing the build-up of toxic Ab42 aggregates.

Earlier animal studies of bexarotene had suggested that the drug could actually reverse Alzheimer’s symptoms by clearing Ab42 aggregates in the brain. But those earlier results, which were later called into question, were based on a completely different mode of action – the clearance of aggregates – than the one reported in the current study. Bexarotene was tested earlier in an unsuccessful 1-month, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, but this new research suggests that the drug may need to be given very early in the disease.

“We anticipate that the strategy that we have described in this paper will enable the identification of further compounds capable of inhibiting Ab42 aggregation and the definition of the specific microscopic steps affected by each compound (that is, primary or secondary nucleation or elongation),” the researchers wrote. “The results described in the present work indicate that bexarotene and other inhibitors of primary nucleation have the potential to be efficient means of delaying aggregation by reducing the probability that primary nuclei are formed and proliferate, such that our natural protection mechanisms could remain effective to more advanced ages. Indeed, we draw an analogy between the strategy presented here and that of using statins, which reduce the level of cholesterol and thus the risk of heart conditions, and suggest that such molecules could effectively act as ‘neurostatins.’ ”

The research was supported by the Centre for Misfolding Diseases at the University of Cambridge. The authors said they have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Bexarotene, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat skin cancer, stopped the primary nucleation step in the self-assembly of amyloid-beta-42 oligomers and delayed the formation of pathogenic aggregates that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease neurodegeneration using a unique strategy that could potentially identify other anti-Alzheimer’s drugs.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge (England), Lund (Sweden) University, and the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), also found that bexarotene (Targretin) blocked the build-up of toxic amyloid-beta-42 (Ab42) aggregates as well as motility dysfunction in a nematode worm model (Caenorhabditis elegans) of Ab42-mediated toxicity (Sci Adv. 2016 Feb;2:e1501244. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501244).

The researchers used a drug discovery strategy to screen a large set of drugs known to interact with amyloid-beta for molecules that could block the primary nucleation of Ab42 aggregates by analyzing the effects that the drugs had on Ab42’s formation into aggregates. This allowed them to determine potential drug candidates’ mechanism for preventing the build-up of toxic Ab42 aggregates.

Earlier animal studies of bexarotene had suggested that the drug could actually reverse Alzheimer’s symptoms by clearing Ab42 aggregates in the brain. But those earlier results, which were later called into question, were based on a completely different mode of action – the clearance of aggregates – than the one reported in the current study. Bexarotene was tested earlier in an unsuccessful 1-month, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II trial in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, but this new research suggests that the drug may need to be given very early in the disease.