User login

M. Alexander Otto began his reporting career early in 1999 covering the pharmaceutical industry for a national pharmacists' magazine and freelancing for the Washington Post and other newspapers. He then joined BNA, now part of Bloomberg News, covering health law and the protection of people and animals in medical research. Alex next worked for the McClatchy Company. Based on his work, Alex won a year-long Knight Science Journalism Fellowship to MIT in 2008-2009. He joined the company shortly thereafter. Alex has a newspaper journalism degree from Syracuse (N.Y.) University and a master's degree in medical science -- a physician assistant degree -- from George Washington University. Alex is based in Seattle.

HbA1c cutpoint predicts pediatric T1DM within a year

ORLANDO – Among children with genetic risks for type 1 diabetes and autoantibodies against pancreatic islet cells, a hemoglobin A1c at or above 5.6% strongly predicts the onset of type 1 diabetes within a year, according to investigators from The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study.

The risk is even greater if other factors – age at A1c test, month of A1c test, continent of residence, and the z-score for one antibody in particular, IA2A, a tyrosine phosphatase antigen protein – are taken into account, with an area under the curve (AUC) of about 0.97. The study team is developing an online risk calculator for clinicians so they can simply plug in the numbers.

But the 5.6% cutpoint works well even by itself, with an AUC of about 0.86. Among the children with genetic risk factors and islet cell autoantibodies who hit that mark in the study, the median time to diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) was 7.1 months.

The point of the work is to catch disease onset early to prevent children from going into diabetic ketoacidosis.

The ultimate goal of TEDDY is to identify infectious agents, dietary factors, and other environmental agents that either trigger or protect against T1DM in genetically susceptible children, to develop strategies to prevent, delay, or even reverse T1DM. For more than a decade, the consortium has been following more than 8,000 children who screened positive at birth for genetic anomalies in the human leukocyte antigen region on their 6th chromosome, a major risk factor for T1DM. The team is following them to find out what puts them over the edge; A1c seems to be key.

Catching the disease early is a goal. Until now, the TEDDY team has used the development of pancreatic islet cell autoantibodies to trigger oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) every 6 months.

The problem is that islet antibodies “are great at saying that you are going to get diabetes but not when. We have kids who have been multiple antibody positive now for 6, 7, 8 years” but who still haven’t developed T1DM. In the meantime, their parents have been dragging them in for OGTTs every 6 months for years, said lead investigator and TEDDY study coordinator Michael Killian, of the Pacific Northwest Research Institute, Seattle.

With the A1c cutpoint, it should be safe to hold off on direct glycemic surveillance until A1c levels reach 5.6%, and even safer when the full risk prediction model with 1A2A z-scores and other factors are available. Once children hit the parameters, it’s near certain they will develop T1DM within a year, so the findings should reduce the number of OGTT tests to just two or three. In the end, “we’ll get better compliance” with testing and still “catch these kids early,” Mr. Killian said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Rare is the newborn who is screened for diabetes risk at birth, and even rarer is the child who is followed for autoantibodies. If the findings hold out, however, such early action could be the future.

“We envision a time” when newborns are screened for T1DM risk and followed for autoantibodies. Glycemic surveillance will kick in if they hit A1c levels of 5.6%, said William Hagopian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a TEDDY principal investigator.

Among the 8,000-plus children followed, 456 had persistent islet autoantibodies and at least three A1c tests in the prior 12 months; 104 progressed to T1DM and 352 did not. The mean age to islet autoantibody seroconversion was 43 months, and mean age to T1DM diagnosis was 73 months. The team ran a receiver operating curve analysis to identify the optimum A1c cutpoint, 5.6%.

The month of testing mattered, because “glycemia is higher in the winter, lower in the summer, and insulin sensitivity is lower in the winter, and higher in the summer,” Dr. Hagopian said. It probably has something to do with what the stresses of early human evolution bred into the genes.

The IA2A autoantibody z-score is the only number that will be cumbersome to plug into the upcoming online risk calculator. It’s the number of standard deviations off your reference lab’s mean. “You have to talk to the lab that does your IA2As to know what the standard deviation is,” Dr. Hagopian said.

The investigators had no disclosures. TEDDY is supported by the National Institutes of Health, among other entities.

SOURCE: Killian M et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 162-LB

ORLANDO – Among children with genetic risks for type 1 diabetes and autoantibodies against pancreatic islet cells, a hemoglobin A1c at or above 5.6% strongly predicts the onset of type 1 diabetes within a year, according to investigators from The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study.

The risk is even greater if other factors – age at A1c test, month of A1c test, continent of residence, and the z-score for one antibody in particular, IA2A, a tyrosine phosphatase antigen protein – are taken into account, with an area under the curve (AUC) of about 0.97. The study team is developing an online risk calculator for clinicians so they can simply plug in the numbers.

But the 5.6% cutpoint works well even by itself, with an AUC of about 0.86. Among the children with genetic risk factors and islet cell autoantibodies who hit that mark in the study, the median time to diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) was 7.1 months.

The point of the work is to catch disease onset early to prevent children from going into diabetic ketoacidosis.

The ultimate goal of TEDDY is to identify infectious agents, dietary factors, and other environmental agents that either trigger or protect against T1DM in genetically susceptible children, to develop strategies to prevent, delay, or even reverse T1DM. For more than a decade, the consortium has been following more than 8,000 children who screened positive at birth for genetic anomalies in the human leukocyte antigen region on their 6th chromosome, a major risk factor for T1DM. The team is following them to find out what puts them over the edge; A1c seems to be key.

Catching the disease early is a goal. Until now, the TEDDY team has used the development of pancreatic islet cell autoantibodies to trigger oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) every 6 months.

The problem is that islet antibodies “are great at saying that you are going to get diabetes but not when. We have kids who have been multiple antibody positive now for 6, 7, 8 years” but who still haven’t developed T1DM. In the meantime, their parents have been dragging them in for OGTTs every 6 months for years, said lead investigator and TEDDY study coordinator Michael Killian, of the Pacific Northwest Research Institute, Seattle.

With the A1c cutpoint, it should be safe to hold off on direct glycemic surveillance until A1c levels reach 5.6%, and even safer when the full risk prediction model with 1A2A z-scores and other factors are available. Once children hit the parameters, it’s near certain they will develop T1DM within a year, so the findings should reduce the number of OGTT tests to just two or three. In the end, “we’ll get better compliance” with testing and still “catch these kids early,” Mr. Killian said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Rare is the newborn who is screened for diabetes risk at birth, and even rarer is the child who is followed for autoantibodies. If the findings hold out, however, such early action could be the future.

“We envision a time” when newborns are screened for T1DM risk and followed for autoantibodies. Glycemic surveillance will kick in if they hit A1c levels of 5.6%, said William Hagopian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a TEDDY principal investigator.

Among the 8,000-plus children followed, 456 had persistent islet autoantibodies and at least three A1c tests in the prior 12 months; 104 progressed to T1DM and 352 did not. The mean age to islet autoantibody seroconversion was 43 months, and mean age to T1DM diagnosis was 73 months. The team ran a receiver operating curve analysis to identify the optimum A1c cutpoint, 5.6%.

The month of testing mattered, because “glycemia is higher in the winter, lower in the summer, and insulin sensitivity is lower in the winter, and higher in the summer,” Dr. Hagopian said. It probably has something to do with what the stresses of early human evolution bred into the genes.

The IA2A autoantibody z-score is the only number that will be cumbersome to plug into the upcoming online risk calculator. It’s the number of standard deviations off your reference lab’s mean. “You have to talk to the lab that does your IA2As to know what the standard deviation is,” Dr. Hagopian said.

The investigators had no disclosures. TEDDY is supported by the National Institutes of Health, among other entities.

SOURCE: Killian M et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 162-LB

ORLANDO – Among children with genetic risks for type 1 diabetes and autoantibodies against pancreatic islet cells, a hemoglobin A1c at or above 5.6% strongly predicts the onset of type 1 diabetes within a year, according to investigators from The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study.

The risk is even greater if other factors – age at A1c test, month of A1c test, continent of residence, and the z-score for one antibody in particular, IA2A, a tyrosine phosphatase antigen protein – are taken into account, with an area under the curve (AUC) of about 0.97. The study team is developing an online risk calculator for clinicians so they can simply plug in the numbers.

But the 5.6% cutpoint works well even by itself, with an AUC of about 0.86. Among the children with genetic risk factors and islet cell autoantibodies who hit that mark in the study, the median time to diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) was 7.1 months.

The point of the work is to catch disease onset early to prevent children from going into diabetic ketoacidosis.

The ultimate goal of TEDDY is to identify infectious agents, dietary factors, and other environmental agents that either trigger or protect against T1DM in genetically susceptible children, to develop strategies to prevent, delay, or even reverse T1DM. For more than a decade, the consortium has been following more than 8,000 children who screened positive at birth for genetic anomalies in the human leukocyte antigen region on their 6th chromosome, a major risk factor for T1DM. The team is following them to find out what puts them over the edge; A1c seems to be key.

Catching the disease early is a goal. Until now, the TEDDY team has used the development of pancreatic islet cell autoantibodies to trigger oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs) every 6 months.

The problem is that islet antibodies “are great at saying that you are going to get diabetes but not when. We have kids who have been multiple antibody positive now for 6, 7, 8 years” but who still haven’t developed T1DM. In the meantime, their parents have been dragging them in for OGTTs every 6 months for years, said lead investigator and TEDDY study coordinator Michael Killian, of the Pacific Northwest Research Institute, Seattle.

With the A1c cutpoint, it should be safe to hold off on direct glycemic surveillance until A1c levels reach 5.6%, and even safer when the full risk prediction model with 1A2A z-scores and other factors are available. Once children hit the parameters, it’s near certain they will develop T1DM within a year, so the findings should reduce the number of OGTT tests to just two or three. In the end, “we’ll get better compliance” with testing and still “catch these kids early,” Mr. Killian said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Rare is the newborn who is screened for diabetes risk at birth, and even rarer is the child who is followed for autoantibodies. If the findings hold out, however, such early action could be the future.

“We envision a time” when newborns are screened for T1DM risk and followed for autoantibodies. Glycemic surveillance will kick in if they hit A1c levels of 5.6%, said William Hagopian, MD, PhD, clinical associate professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, and a TEDDY principal investigator.

Among the 8,000-plus children followed, 456 had persistent islet autoantibodies and at least three A1c tests in the prior 12 months; 104 progressed to T1DM and 352 did not. The mean age to islet autoantibody seroconversion was 43 months, and mean age to T1DM diagnosis was 73 months. The team ran a receiver operating curve analysis to identify the optimum A1c cutpoint, 5.6%.

The month of testing mattered, because “glycemia is higher in the winter, lower in the summer, and insulin sensitivity is lower in the winter, and higher in the summer,” Dr. Hagopian said. It probably has something to do with what the stresses of early human evolution bred into the genes.

The IA2A autoantibody z-score is the only number that will be cumbersome to plug into the upcoming online risk calculator. It’s the number of standard deviations off your reference lab’s mean. “You have to talk to the lab that does your IA2As to know what the standard deviation is,” Dr. Hagopian said.

The investigators had no disclosures. TEDDY is supported by the National Institutes of Health, among other entities.

SOURCE: Killian M et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 162-LB

FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Among children with genetic risks for type 1 diabetes and autoantibodies against pancreatic islet cells, a hemoglobin A1c at or above 5.6% strongly predicts the onset of type 1 diabetes within a year.

Major finding: Among the children with genetic risk factors and islet cell autoantibodies who hit that mark, the median time to diagnosis was 7.1 months.

Study details: The findings are from more than 400 children in The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) cohort.

Disclosures: The investigators had no disclosures. TEDDY is supported by the National Institutes of Health, among other entities.

Source: Killian M et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 162-LB.

Timely culture reports lower LOS for neonatal fever

ATLANTA – An adjustment in the culture reporting schedule at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, helped reduce the average length of stay for neonatal fever from 48 to 43 hours, without increasing readmissions for serious bacterial infections, according to a review presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Investigators there were working to meet the goals of the Reducing Excessive Variability in Infant Sepsis Evaluation project (REVISE), a national collaboration aimed at improving care. One of the goals is to reduce the length of stay (LOS) for neonatal fever to fewer than 30 hours for low-risk infants and fewer than 42 hours among high-risk infants.

The traditional standard is to keep children in the hospital for 48 hours to rule out sepsis, but that thinking has begun to change amid evidence that blood cultures generally do not need that long to turn positive, among other findings, said investigator Huay-Ying Lo, MD, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s.

“At our institution,” which admits more than 200 NF cases annually, “we have order sets for neonatal fever, and we’re actually doing pretty well” meeting most of the REVISE goals, “so we decided to focus on reducing length of stay,” she said at the meeting.

Evidence of the safety and cost savings of earlier discharge was presented to providers, and weekly emails reminded them of the early discharge goal and updated them on the current average LOS for NF.

Dr. Lo and her team also brainstormed with providers to identify problems. “One of the barriers they consistently mentioned was the timing of cultures being reported out from the microbiology lab. A lot of time, people were just waiting for the report to say no growth for 36 hours or whatever it was going to be,” she said.

That led to talks with the microbiology department. Blood cultures were already automated, so there wasn’t much that needed to be done. Urine cultures were read manually three to four times a day after the initial incubation period. However, after an initial Gram stain, CSF cultures were read manually only one or two times a day – whenever somebody had time. The hours were random, and sometimes results were not reported until the evening, which meant the child had to spend another night in the hospital.

The lab director agreed that it was a problem, and standardized procedures to read cultures twice a day, at 7 a.m. and 2 p.m. “The times we agreed upon; 7 a.m. works really well for morning discharge, and at 2 p.m., the day team is still there and can get kids out that day,” Dr. Lo explained.

. Among infants 7-60 days old admitted with NF – excluding ill-appearing children and those with comorbidities that increased the risk of infections – the mean LOS fell from 48 hours among 144 infants treated before the intervention, to 43 hours among 157 treated afterward (P = .001), and “we didn’t have any more readmission for serious bacterial infections,” Dr. Lo said.

“We want to reduce it further. If we get to 42 hours, we’ll be pretty happy.” Updating discharge criteria, and letting providers know how their LOS’s compare with their peers’ might help. “I’m sure some people are more conservative and some a little more liberal,” she said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – An adjustment in the culture reporting schedule at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, helped reduce the average length of stay for neonatal fever from 48 to 43 hours, without increasing readmissions for serious bacterial infections, according to a review presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Investigators there were working to meet the goals of the Reducing Excessive Variability in Infant Sepsis Evaluation project (REVISE), a national collaboration aimed at improving care. One of the goals is to reduce the length of stay (LOS) for neonatal fever to fewer than 30 hours for low-risk infants and fewer than 42 hours among high-risk infants.

The traditional standard is to keep children in the hospital for 48 hours to rule out sepsis, but that thinking has begun to change amid evidence that blood cultures generally do not need that long to turn positive, among other findings, said investigator Huay-Ying Lo, MD, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s.

“At our institution,” which admits more than 200 NF cases annually, “we have order sets for neonatal fever, and we’re actually doing pretty well” meeting most of the REVISE goals, “so we decided to focus on reducing length of stay,” she said at the meeting.

Evidence of the safety and cost savings of earlier discharge was presented to providers, and weekly emails reminded them of the early discharge goal and updated them on the current average LOS for NF.

Dr. Lo and her team also brainstormed with providers to identify problems. “One of the barriers they consistently mentioned was the timing of cultures being reported out from the microbiology lab. A lot of time, people were just waiting for the report to say no growth for 36 hours or whatever it was going to be,” she said.

That led to talks with the microbiology department. Blood cultures were already automated, so there wasn’t much that needed to be done. Urine cultures were read manually three to four times a day after the initial incubation period. However, after an initial Gram stain, CSF cultures were read manually only one or two times a day – whenever somebody had time. The hours were random, and sometimes results were not reported until the evening, which meant the child had to spend another night in the hospital.

The lab director agreed that it was a problem, and standardized procedures to read cultures twice a day, at 7 a.m. and 2 p.m. “The times we agreed upon; 7 a.m. works really well for morning discharge, and at 2 p.m., the day team is still there and can get kids out that day,” Dr. Lo explained.

. Among infants 7-60 days old admitted with NF – excluding ill-appearing children and those with comorbidities that increased the risk of infections – the mean LOS fell from 48 hours among 144 infants treated before the intervention, to 43 hours among 157 treated afterward (P = .001), and “we didn’t have any more readmission for serious bacterial infections,” Dr. Lo said.

“We want to reduce it further. If we get to 42 hours, we’ll be pretty happy.” Updating discharge criteria, and letting providers know how their LOS’s compare with their peers’ might help. “I’m sure some people are more conservative and some a little more liberal,” she said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – An adjustment in the culture reporting schedule at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, helped reduce the average length of stay for neonatal fever from 48 to 43 hours, without increasing readmissions for serious bacterial infections, according to a review presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

Investigators there were working to meet the goals of the Reducing Excessive Variability in Infant Sepsis Evaluation project (REVISE), a national collaboration aimed at improving care. One of the goals is to reduce the length of stay (LOS) for neonatal fever to fewer than 30 hours for low-risk infants and fewer than 42 hours among high-risk infants.

The traditional standard is to keep children in the hospital for 48 hours to rule out sepsis, but that thinking has begun to change amid evidence that blood cultures generally do not need that long to turn positive, among other findings, said investigator Huay-Ying Lo, MD, a pediatrician at Texas Children’s.

“At our institution,” which admits more than 200 NF cases annually, “we have order sets for neonatal fever, and we’re actually doing pretty well” meeting most of the REVISE goals, “so we decided to focus on reducing length of stay,” she said at the meeting.

Evidence of the safety and cost savings of earlier discharge was presented to providers, and weekly emails reminded them of the early discharge goal and updated them on the current average LOS for NF.

Dr. Lo and her team also brainstormed with providers to identify problems. “One of the barriers they consistently mentioned was the timing of cultures being reported out from the microbiology lab. A lot of time, people were just waiting for the report to say no growth for 36 hours or whatever it was going to be,” she said.

That led to talks with the microbiology department. Blood cultures were already automated, so there wasn’t much that needed to be done. Urine cultures were read manually three to four times a day after the initial incubation period. However, after an initial Gram stain, CSF cultures were read manually only one or two times a day – whenever somebody had time. The hours were random, and sometimes results were not reported until the evening, which meant the child had to spend another night in the hospital.

The lab director agreed that it was a problem, and standardized procedures to read cultures twice a day, at 7 a.m. and 2 p.m. “The times we agreed upon; 7 a.m. works really well for morning discharge, and at 2 p.m., the day team is still there and can get kids out that day,” Dr. Lo explained.

. Among infants 7-60 days old admitted with NF – excluding ill-appearing children and those with comorbidities that increased the risk of infections – the mean LOS fell from 48 hours among 144 infants treated before the intervention, to 43 hours among 157 treated afterward (P = .001), and “we didn’t have any more readmission for serious bacterial infections,” Dr. Lo said.

“We want to reduce it further. If we get to 42 hours, we’ll be pretty happy.” Updating discharge criteria, and letting providers know how their LOS’s compare with their peers’ might help. “I’m sure some people are more conservative and some a little more liberal,” she said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point: An adjustment in the culture reporting schedule at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, helped reduce the average length of stay for neonatal fever, without increasing readmissions for serious bacterial infections.

Major finding: The mean length of stay fell from 48 hours among 144 infants treated before the intervention, to 43 hours among 157 treated afterward (P = .001).

Study details: Pre/post analysis of quality improvement project.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

FDA: Cancer risk low with recalled valsartan

The risk of cancer from N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) contained in impure valsartan is real but very low, the Food and Drug Administration said in a July 27 statement.

The agency had announced a voluntary recall of valsartan from Major Pharmaceuticals, Solco Healthcare, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, as well as valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide from Solco and Teva, on July 13 after detection of NDMA, a semi-volatile organic compound. The manufacturer, Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceuticals in Linhai, China, has since stopped distribution. Contamination probably is tied to a change in the manufacturing process.

NDMA has been linked to cancer in animal studies but at levels “much higher than the impurity levels in recalled valsartan batches.” Even so, the agency “wanted to put some context around the actual potential risk posed to patients who used versions of valsartan that may have contained high levels of NDMA,” the FDA said in its updated press release.

Based on records from the manufacturer, “some levels of the impurity may have been in the valsartan-containing products for as long as 4 years. FDA scientists estimate that if 8,000 people took the highest valsartan dose (320 mg) from the recalled batches daily for the full 4 years, there may be one additional case of cancer over the lifetimes of these 8,000 people,” the agency said.

“To put this in context, currently one out of every three people in the U.S. will experience cancer in their lifetime,” it said.

The FDA advised patients to check their prescriptions to see if they originate from one of the recalled batches, and to let their doctors and pharmacists know if they are.

To help, the FDA has posted a list of products included in the recall and a list of products not included in the recall.

They should also follow the recall instructions provided by the specific companies, the FDA said.

The risk of cancer from N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) contained in impure valsartan is real but very low, the Food and Drug Administration said in a July 27 statement.

The agency had announced a voluntary recall of valsartan from Major Pharmaceuticals, Solco Healthcare, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, as well as valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide from Solco and Teva, on July 13 after detection of NDMA, a semi-volatile organic compound. The manufacturer, Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceuticals in Linhai, China, has since stopped distribution. Contamination probably is tied to a change in the manufacturing process.

NDMA has been linked to cancer in animal studies but at levels “much higher than the impurity levels in recalled valsartan batches.” Even so, the agency “wanted to put some context around the actual potential risk posed to patients who used versions of valsartan that may have contained high levels of NDMA,” the FDA said in its updated press release.

Based on records from the manufacturer, “some levels of the impurity may have been in the valsartan-containing products for as long as 4 years. FDA scientists estimate that if 8,000 people took the highest valsartan dose (320 mg) from the recalled batches daily for the full 4 years, there may be one additional case of cancer over the lifetimes of these 8,000 people,” the agency said.

“To put this in context, currently one out of every three people in the U.S. will experience cancer in their lifetime,” it said.

The FDA advised patients to check their prescriptions to see if they originate from one of the recalled batches, and to let their doctors and pharmacists know if they are.

To help, the FDA has posted a list of products included in the recall and a list of products not included in the recall.

They should also follow the recall instructions provided by the specific companies, the FDA said.

The risk of cancer from N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) contained in impure valsartan is real but very low, the Food and Drug Administration said in a July 27 statement.

The agency had announced a voluntary recall of valsartan from Major Pharmaceuticals, Solco Healthcare, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, as well as valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide from Solco and Teva, on July 13 after detection of NDMA, a semi-volatile organic compound. The manufacturer, Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceuticals in Linhai, China, has since stopped distribution. Contamination probably is tied to a change in the manufacturing process.

NDMA has been linked to cancer in animal studies but at levels “much higher than the impurity levels in recalled valsartan batches.” Even so, the agency “wanted to put some context around the actual potential risk posed to patients who used versions of valsartan that may have contained high levels of NDMA,” the FDA said in its updated press release.

Based on records from the manufacturer, “some levels of the impurity may have been in the valsartan-containing products for as long as 4 years. FDA scientists estimate that if 8,000 people took the highest valsartan dose (320 mg) from the recalled batches daily for the full 4 years, there may be one additional case of cancer over the lifetimes of these 8,000 people,” the agency said.

“To put this in context, currently one out of every three people in the U.S. will experience cancer in their lifetime,” it said.

The FDA advised patients to check their prescriptions to see if they originate from one of the recalled batches, and to let their doctors and pharmacists know if they are.

To help, the FDA has posted a list of products included in the recall and a list of products not included in the recall.

They should also follow the recall instructions provided by the specific companies, the FDA said.

Asthma medication ratio identifies high-risk pediatric patients

ATLANTA – An according to researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston.

The asthma medication ratio (AMR) – the number of prescriptions for controller medications divided by the number of prescriptions for both controller and rescue medications – has been around for a while, but it’s mostly been used as a quality metric. The new study shows that it’s also useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

A perfect ratio of 1 means that control is good without rescue inhalers. The ratio falls as the number of rescue inhalers goes up, signaling poorer control. Children with a ratio below 0.5 are considered high risk; they’d hit that mark if, for instance, they were prescribed one control medication such as fluticasone propionate (Flovent) and two albuterol rescue inhalers in a month.

If control is good, “you should only need a rescue inhaler very, very sporadically;” high-risk children probably need a higher dose of their controller, or help with compliance, explained lead investigator Annie L. Andrews, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at MUSC.

The university uses the EPIC records system, which incorporates prescription data from Surescripts, so the number of asthma medication fills is already available. The system just needs to be adjusted to calculate and report AMRs monthly, something Dr. Andrews and her team are working on. “The information is right there, but it’s an untapped resource,” she said. “We just need to crunch the numbers, and operationalize it. Why are we waiting until kids are in the hospital” to intervene?

Dr. Andrews presented a proof-of-concept study at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting. Her team identified 214,452 asthma patients aged 2-17 years with at least one claim for an inhaled corticosteroid in the Truven MarketScan Medicaid database from 2013-14.

They calculated AMRs for each child every 3 months over a 15-month period. About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5.

The first AMR was at or above 0.5 in 93,512 children; 18.1% had a subsequent asthma-related event, meaning an ED visit or hospitalization, during the course of the study. Among the 17,635 children with an initial AMR below 0.5, 25% had asthma-related events. The initial AMR couldn’t be calculated in 103,305 children, which likely meant they had less-active disease. Those children had the lowest proportion of asthma events, at 13.9%.

An AMR below 0.5 nearly doubled the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED visit in the subsequent 3 months, with an odds ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, compared with other children. The findings were statistically significant.

In short, serial AMRs helped predict exacerbations among Medicaid children. The team showed the same trend among commercially insured children in a recently published study. The only difference was that Medicaid children had a higher proportion of high-risk AMRs, and a higher number of asthma events (Am J Manag Care. 2018 Jun;24[6]:294-300). Together, the studies validate “the rolling 3-month AMR as an appropriate method for identifying children at high risk for imminent exacerbation,” the investigators concluded.

With automatic AMR reporting already in the works at MUSC, “we are now trying to figure out how to intervene. Do we just tell providers who their high-risk kids are and let them figure out how to contact families, or do we use this information to contact families directly? That’s kind of what I favor: ‘Hey, your kid just popped up as high risk, so let’s figure out what you need. Do you need a new prescription or a reminder to see your doctor?’ ” Dr. Andrews said.

Her team is developing a mobile app to communicate with families.

The mean age in the study was 7.9 years; 59% of the children were boys, and 41% were black.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Andrews had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – An according to researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston.

The asthma medication ratio (AMR) – the number of prescriptions for controller medications divided by the number of prescriptions for both controller and rescue medications – has been around for a while, but it’s mostly been used as a quality metric. The new study shows that it’s also useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

A perfect ratio of 1 means that control is good without rescue inhalers. The ratio falls as the number of rescue inhalers goes up, signaling poorer control. Children with a ratio below 0.5 are considered high risk; they’d hit that mark if, for instance, they were prescribed one control medication such as fluticasone propionate (Flovent) and two albuterol rescue inhalers in a month.

If control is good, “you should only need a rescue inhaler very, very sporadically;” high-risk children probably need a higher dose of their controller, or help with compliance, explained lead investigator Annie L. Andrews, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at MUSC.

The university uses the EPIC records system, which incorporates prescription data from Surescripts, so the number of asthma medication fills is already available. The system just needs to be adjusted to calculate and report AMRs monthly, something Dr. Andrews and her team are working on. “The information is right there, but it’s an untapped resource,” she said. “We just need to crunch the numbers, and operationalize it. Why are we waiting until kids are in the hospital” to intervene?

Dr. Andrews presented a proof-of-concept study at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting. Her team identified 214,452 asthma patients aged 2-17 years with at least one claim for an inhaled corticosteroid in the Truven MarketScan Medicaid database from 2013-14.

They calculated AMRs for each child every 3 months over a 15-month period. About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5.

The first AMR was at or above 0.5 in 93,512 children; 18.1% had a subsequent asthma-related event, meaning an ED visit or hospitalization, during the course of the study. Among the 17,635 children with an initial AMR below 0.5, 25% had asthma-related events. The initial AMR couldn’t be calculated in 103,305 children, which likely meant they had less-active disease. Those children had the lowest proportion of asthma events, at 13.9%.

An AMR below 0.5 nearly doubled the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED visit in the subsequent 3 months, with an odds ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, compared with other children. The findings were statistically significant.

In short, serial AMRs helped predict exacerbations among Medicaid children. The team showed the same trend among commercially insured children in a recently published study. The only difference was that Medicaid children had a higher proportion of high-risk AMRs, and a higher number of asthma events (Am J Manag Care. 2018 Jun;24[6]:294-300). Together, the studies validate “the rolling 3-month AMR as an appropriate method for identifying children at high risk for imminent exacerbation,” the investigators concluded.

With automatic AMR reporting already in the works at MUSC, “we are now trying to figure out how to intervene. Do we just tell providers who their high-risk kids are and let them figure out how to contact families, or do we use this information to contact families directly? That’s kind of what I favor: ‘Hey, your kid just popped up as high risk, so let’s figure out what you need. Do you need a new prescription or a reminder to see your doctor?’ ” Dr. Andrews said.

Her team is developing a mobile app to communicate with families.

The mean age in the study was 7.9 years; 59% of the children were boys, and 41% were black.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Andrews had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

ATLANTA – An according to researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston.

The asthma medication ratio (AMR) – the number of prescriptions for controller medications divided by the number of prescriptions for both controller and rescue medications – has been around for a while, but it’s mostly been used as a quality metric. The new study shows that it’s also useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

A perfect ratio of 1 means that control is good without rescue inhalers. The ratio falls as the number of rescue inhalers goes up, signaling poorer control. Children with a ratio below 0.5 are considered high risk; they’d hit that mark if, for instance, they were prescribed one control medication such as fluticasone propionate (Flovent) and two albuterol rescue inhalers in a month.

If control is good, “you should only need a rescue inhaler very, very sporadically;” high-risk children probably need a higher dose of their controller, or help with compliance, explained lead investigator Annie L. Andrews, MD, associate professor of pediatrics at MUSC.

The university uses the EPIC records system, which incorporates prescription data from Surescripts, so the number of asthma medication fills is already available. The system just needs to be adjusted to calculate and report AMRs monthly, something Dr. Andrews and her team are working on. “The information is right there, but it’s an untapped resource,” she said. “We just need to crunch the numbers, and operationalize it. Why are we waiting until kids are in the hospital” to intervene?

Dr. Andrews presented a proof-of-concept study at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting. Her team identified 214,452 asthma patients aged 2-17 years with at least one claim for an inhaled corticosteroid in the Truven MarketScan Medicaid database from 2013-14.

They calculated AMRs for each child every 3 months over a 15-month period. About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5.

The first AMR was at or above 0.5 in 93,512 children; 18.1% had a subsequent asthma-related event, meaning an ED visit or hospitalization, during the course of the study. Among the 17,635 children with an initial AMR below 0.5, 25% had asthma-related events. The initial AMR couldn’t be calculated in 103,305 children, which likely meant they had less-active disease. Those children had the lowest proportion of asthma events, at 13.9%.

An AMR below 0.5 nearly doubled the risk of an asthma-related hospitalization or ED visit in the subsequent 3 months, with an odds ratios ranging from 1.7 to 1.9, compared with other children. The findings were statistically significant.

In short, serial AMRs helped predict exacerbations among Medicaid children. The team showed the same trend among commercially insured children in a recently published study. The only difference was that Medicaid children had a higher proportion of high-risk AMRs, and a higher number of asthma events (Am J Manag Care. 2018 Jun;24[6]:294-300). Together, the studies validate “the rolling 3-month AMR as an appropriate method for identifying children at high risk for imminent exacerbation,” the investigators concluded.

With automatic AMR reporting already in the works at MUSC, “we are now trying to figure out how to intervene. Do we just tell providers who their high-risk kids are and let them figure out how to contact families, or do we use this information to contact families directly? That’s kind of what I favor: ‘Hey, your kid just popped up as high risk, so let’s figure out what you need. Do you need a new prescription or a reminder to see your doctor?’ ” Dr. Andrews said.

Her team is developing a mobile app to communicate with families.

The mean age in the study was 7.9 years; 59% of the children were boys, and 41% were black.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Andrews had no disclosures. The meeting was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point: The asthma medication ratio is useful in the clinic to identify children who could benefit from extra attention.

Major finding: About 9% of children at any given time had AMRs below 0.5, meaning they were at high risk for acute exacerbations.

Study details: Review of more than 200,000 pediatric asthma patients on Medicaid

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, among others. The study lead had no disclosures.

Short-course IV antibiotics okay for newborn bacteremic UTI

ATLANTA – A short course of IV antibiotics – 7 days or less – is fine for most infants with uncomplicated bacteremic urinary tract infections, according to a review of 116 children younger than 60 days.

How long to treat bacteremic UTIs in the very young has been debated in pediatrics for a while, with some centers opting for a few days and others for 2 weeks or more. Shorter courses reduce length of stay, costs, and complications, but there hasn’t been much research to see whether they work as well.

The new investigation has suggested they do. “Young infants with bacteremic UTI who received less than or equal to 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy did not have more recurrent UTIs,” compared “to infants who received longer courses. Short course IV therapy with early conversion to oral antibiotics may be considered in this population,” said lead investigator Sanyukta Desai, MD, at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The team compared outcomes of 58 infants treated for 7 days or less to outcomes of 58 infants treated for more than 7 days at 11 children’s hospitals scattered across the United States.

Urine was collected by catheter, and each child grew the same organism in their blood and urine cultures, confirming the diagnosis of bacteremic UTI. Children with bacterial meningitis, or suspected of having it, were excluded. The subjects had all been admitted through the ED.

There was quite a bit of variation among the 11 hospitals, with the proportion of children treated with short courses ranging from 10% to 81%.

As for the results, two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days. None of them developed meningitis, and none required ICU admission. Propensity-score matching revealed an odds ratio for recurrence that favored shorter treatment, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The mean length of stay was 5 days in the short-course arm and 11 days in the long-course arm. There were no serious adverse events within 30 days of the index admission in either group.

Among the recurrences, the two children in the short-course arm were initially treated for 3 and 5 days. Both were older than 28 days at their initial presentation, and both had vesicoureteral reflux of at least grade 2, which was not diagnosed in one child until after the recurrence. The other child had been on prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole before the recurrence.

The four recurrent cases in the long arm initially received either 10 or 14 days of IV antibiotics. Two children had grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux and had been on prophylactic amoxicillin.

Infants treated with longer antibiotic courses were more likely to be under 28 days old, appear ill at presentation, have had bacteremia for more than 24 hours, and have and grow out pathogens other than Escherichia coli. The two groups were otherwise balanced for sex, prematurity, complex chronic conditions, and known genitourinary anomalies.

With such low event rates, the study wasn’t powered to detect small but potentially meaningful differences in outcomes, and further work is needed to define which children would benefit from longer treatment courses. Even so, “it was reassuring that patients did well in both arms,” said Dr. Desai, a clinical fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“At our institution with uncomplicated UTI, we wait to see what the culture grows.” If there’s an oral antibiotic that will work, “we send [infants] home in 3-4 days. We haven’t had any poor outcomes, even when they’re bacteremic,” she said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ATLANTA – A short course of IV antibiotics – 7 days or less – is fine for most infants with uncomplicated bacteremic urinary tract infections, according to a review of 116 children younger than 60 days.

How long to treat bacteremic UTIs in the very young has been debated in pediatrics for a while, with some centers opting for a few days and others for 2 weeks or more. Shorter courses reduce length of stay, costs, and complications, but there hasn’t been much research to see whether they work as well.

The new investigation has suggested they do. “Young infants with bacteremic UTI who received less than or equal to 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy did not have more recurrent UTIs,” compared “to infants who received longer courses. Short course IV therapy with early conversion to oral antibiotics may be considered in this population,” said lead investigator Sanyukta Desai, MD, at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The team compared outcomes of 58 infants treated for 7 days or less to outcomes of 58 infants treated for more than 7 days at 11 children’s hospitals scattered across the United States.

Urine was collected by catheter, and each child grew the same organism in their blood and urine cultures, confirming the diagnosis of bacteremic UTI. Children with bacterial meningitis, or suspected of having it, were excluded. The subjects had all been admitted through the ED.

There was quite a bit of variation among the 11 hospitals, with the proportion of children treated with short courses ranging from 10% to 81%.

As for the results, two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days. None of them developed meningitis, and none required ICU admission. Propensity-score matching revealed an odds ratio for recurrence that favored shorter treatment, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The mean length of stay was 5 days in the short-course arm and 11 days in the long-course arm. There were no serious adverse events within 30 days of the index admission in either group.

Among the recurrences, the two children in the short-course arm were initially treated for 3 and 5 days. Both were older than 28 days at their initial presentation, and both had vesicoureteral reflux of at least grade 2, which was not diagnosed in one child until after the recurrence. The other child had been on prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole before the recurrence.

The four recurrent cases in the long arm initially received either 10 or 14 days of IV antibiotics. Two children had grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux and had been on prophylactic amoxicillin.

Infants treated with longer antibiotic courses were more likely to be under 28 days old, appear ill at presentation, have had bacteremia for more than 24 hours, and have and grow out pathogens other than Escherichia coli. The two groups were otherwise balanced for sex, prematurity, complex chronic conditions, and known genitourinary anomalies.

With such low event rates, the study wasn’t powered to detect small but potentially meaningful differences in outcomes, and further work is needed to define which children would benefit from longer treatment courses. Even so, “it was reassuring that patients did well in both arms,” said Dr. Desai, a clinical fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“At our institution with uncomplicated UTI, we wait to see what the culture grows.” If there’s an oral antibiotic that will work, “we send [infants] home in 3-4 days. We haven’t had any poor outcomes, even when they’re bacteremic,” she said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ATLANTA – A short course of IV antibiotics – 7 days or less – is fine for most infants with uncomplicated bacteremic urinary tract infections, according to a review of 116 children younger than 60 days.

How long to treat bacteremic UTIs in the very young has been debated in pediatrics for a while, with some centers opting for a few days and others for 2 weeks or more. Shorter courses reduce length of stay, costs, and complications, but there hasn’t been much research to see whether they work as well.

The new investigation has suggested they do. “Young infants with bacteremic UTI who received less than or equal to 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy did not have more recurrent UTIs,” compared “to infants who received longer courses. Short course IV therapy with early conversion to oral antibiotics may be considered in this population,” said lead investigator Sanyukta Desai, MD, at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The team compared outcomes of 58 infants treated for 7 days or less to outcomes of 58 infants treated for more than 7 days at 11 children’s hospitals scattered across the United States.

Urine was collected by catheter, and each child grew the same organism in their blood and urine cultures, confirming the diagnosis of bacteremic UTI. Children with bacterial meningitis, or suspected of having it, were excluded. The subjects had all been admitted through the ED.

There was quite a bit of variation among the 11 hospitals, with the proportion of children treated with short courses ranging from 10% to 81%.

As for the results, two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days. None of them developed meningitis, and none required ICU admission. Propensity-score matching revealed an odds ratio for recurrence that favored shorter treatment, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The mean length of stay was 5 days in the short-course arm and 11 days in the long-course arm. There were no serious adverse events within 30 days of the index admission in either group.

Among the recurrences, the two children in the short-course arm were initially treated for 3 and 5 days. Both were older than 28 days at their initial presentation, and both had vesicoureteral reflux of at least grade 2, which was not diagnosed in one child until after the recurrence. The other child had been on prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole before the recurrence.

The four recurrent cases in the long arm initially received either 10 or 14 days of IV antibiotics. Two children had grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux and had been on prophylactic amoxicillin.

Infants treated with longer antibiotic courses were more likely to be under 28 days old, appear ill at presentation, have had bacteremia for more than 24 hours, and have and grow out pathogens other than Escherichia coli. The two groups were otherwise balanced for sex, prematurity, complex chronic conditions, and known genitourinary anomalies.

With such low event rates, the study wasn’t powered to detect small but potentially meaningful differences in outcomes, and further work is needed to define which children would benefit from longer treatment courses. Even so, “it was reassuring that patients did well in both arms,” said Dr. Desai, a clinical fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“At our institution with uncomplicated UTI, we wait to see what the culture grows.” If there’s an oral antibiotic that will work, “we send [infants] home in 3-4 days. We haven’t had any poor outcomes, even when they’re bacteremic,” she said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days.

Study details: Review of 116 infants.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

Cannabis falls short for chronic noncancer pain

Cannabis did not improve outcomes or reduce prescription opioid use among 1,514 Australians with noncancer pain, according to a recent report in Lancet Public Health.

Almost a quarter of patients reported using cannabis, mostly illicitly since most of the data were collected before Australia legalized medical marijuana in 2016. About 9% reported marijuana use in the previous month at baseline; 13% reported use in the past month at the final interview.

Overall, users rated the degree of relief they got from pain and pain-related distress as 7 out of 10, but the study findings did not support their impression.

At 4 years, cannabis users, compared with nonusers, reported greater pain severity (for daily or near-daily use: risk ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.32; for less frequent use: RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01-1.29), more interference from pain in their daily lives (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.26; for less frequent use: RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.35 ), less ability to cope with pain (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00; for less frequent use: RR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00), and greater generalized anxiety (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15; for less frequent use: RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.12). Results were adjusted for age, sex, pain duration, and other factors.

Pain severity scores on the 10-point Brief Pain Inventory, for instance, were 4.7 points at the end of the study among nonusers, compared with 5.3 among daily or near-daily users.

Few differences were reported in oral morphine equivalents between the groups. People who reported using marijuana 1-19 days a month were less likely to have discontinued opioids at 4 years (9%) than were those reporting no use (21%).

“Interest in the use of cannabis and cannabinoids to treat chronic noncancer pain is increasing because of their potential to reduce opioid dose requirements.” However, “we found no evidence that cannabis use improved patient outcomes” or that cannabis “exerted an opioid-sparing effect,” said the investigators, led by Gabrielle Campbell, PhD, of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney.

The findings are not a slam dunk against cannabis for chronic pain. The investigators noted that people might have used cannabis because they had more pain to begin with and poorer coping mechanisms. Had they not been using marijuana, perhaps they would have been worse off.

However, “to date, evidence that cannabinoids are effective for chronic noncancer pain and aid in reducing opioid use is lacking. they said.

Dr. Campbell and her associates cited several important limitations. Since cannabis use was primarily illicit, it’s unlikely that it was used under medical supervision. Also, the study only gauged frequency of use on a per-day basis. “We do not know if some people used once in a day or more than once. Likewise, we do not know what type of cannabis the participants used. ... This fact matters, as cannabis varies in strength and, as with any analgesia, the dose needs to be matched to the severity of pain experienced,” the team said.

The subjects were a median age of 58 years at baseline, and 56% were women. They had been prescribed a strong opioid for a median of 4 years at study entry and were on a median oral morphine equivalent dose of 75 mg/day, which fell to 57 mg/day at the study’s conclusion. About 62% of the subjects reported neuropathic pain.

The work was funded by the Australian government, and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Campbell reported grants from Reckitt Benckiser.

SOURCE: Campbell G et al. Lancet Public Health. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30110-5.

Cannabis did not improve outcomes or reduce prescription opioid use among 1,514 Australians with noncancer pain, according to a recent report in Lancet Public Health.

Almost a quarter of patients reported using cannabis, mostly illicitly since most of the data were collected before Australia legalized medical marijuana in 2016. About 9% reported marijuana use in the previous month at baseline; 13% reported use in the past month at the final interview.

Overall, users rated the degree of relief they got from pain and pain-related distress as 7 out of 10, but the study findings did not support their impression.

At 4 years, cannabis users, compared with nonusers, reported greater pain severity (for daily or near-daily use: risk ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.32; for less frequent use: RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01-1.29), more interference from pain in their daily lives (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.26; for less frequent use: RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.35 ), less ability to cope with pain (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00; for less frequent use: RR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00), and greater generalized anxiety (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15; for less frequent use: RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.12). Results were adjusted for age, sex, pain duration, and other factors.

Pain severity scores on the 10-point Brief Pain Inventory, for instance, were 4.7 points at the end of the study among nonusers, compared with 5.3 among daily or near-daily users.

Few differences were reported in oral morphine equivalents between the groups. People who reported using marijuana 1-19 days a month were less likely to have discontinued opioids at 4 years (9%) than were those reporting no use (21%).

“Interest in the use of cannabis and cannabinoids to treat chronic noncancer pain is increasing because of their potential to reduce opioid dose requirements.” However, “we found no evidence that cannabis use improved patient outcomes” or that cannabis “exerted an opioid-sparing effect,” said the investigators, led by Gabrielle Campbell, PhD, of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney.

The findings are not a slam dunk against cannabis for chronic pain. The investigators noted that people might have used cannabis because they had more pain to begin with and poorer coping mechanisms. Had they not been using marijuana, perhaps they would have been worse off.

However, “to date, evidence that cannabinoids are effective for chronic noncancer pain and aid in reducing opioid use is lacking. they said.

Dr. Campbell and her associates cited several important limitations. Since cannabis use was primarily illicit, it’s unlikely that it was used under medical supervision. Also, the study only gauged frequency of use on a per-day basis. “We do not know if some people used once in a day or more than once. Likewise, we do not know what type of cannabis the participants used. ... This fact matters, as cannabis varies in strength and, as with any analgesia, the dose needs to be matched to the severity of pain experienced,” the team said.

The subjects were a median age of 58 years at baseline, and 56% were women. They had been prescribed a strong opioid for a median of 4 years at study entry and were on a median oral morphine equivalent dose of 75 mg/day, which fell to 57 mg/day at the study’s conclusion. About 62% of the subjects reported neuropathic pain.

The work was funded by the Australian government, and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Campbell reported grants from Reckitt Benckiser.

SOURCE: Campbell G et al. Lancet Public Health. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30110-5.

Cannabis did not improve outcomes or reduce prescription opioid use among 1,514 Australians with noncancer pain, according to a recent report in Lancet Public Health.

Almost a quarter of patients reported using cannabis, mostly illicitly since most of the data were collected before Australia legalized medical marijuana in 2016. About 9% reported marijuana use in the previous month at baseline; 13% reported use in the past month at the final interview.

Overall, users rated the degree of relief they got from pain and pain-related distress as 7 out of 10, but the study findings did not support their impression.

At 4 years, cannabis users, compared with nonusers, reported greater pain severity (for daily or near-daily use: risk ratio, 1.17; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.32; for less frequent use: RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01-1.29), more interference from pain in their daily lives (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.26; for less frequent use: RR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.35 ), less ability to cope with pain (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00; for less frequent use: RR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00), and greater generalized anxiety (for daily or near-daily use: RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15; for less frequent use: RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.12). Results were adjusted for age, sex, pain duration, and other factors.

Pain severity scores on the 10-point Brief Pain Inventory, for instance, were 4.7 points at the end of the study among nonusers, compared with 5.3 among daily or near-daily users.

Few differences were reported in oral morphine equivalents between the groups. People who reported using marijuana 1-19 days a month were less likely to have discontinued opioids at 4 years (9%) than were those reporting no use (21%).

“Interest in the use of cannabis and cannabinoids to treat chronic noncancer pain is increasing because of their potential to reduce opioid dose requirements.” However, “we found no evidence that cannabis use improved patient outcomes” or that cannabis “exerted an opioid-sparing effect,” said the investigators, led by Gabrielle Campbell, PhD, of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney.

The findings are not a slam dunk against cannabis for chronic pain. The investigators noted that people might have used cannabis because they had more pain to begin with and poorer coping mechanisms. Had they not been using marijuana, perhaps they would have been worse off.

However, “to date, evidence that cannabinoids are effective for chronic noncancer pain and aid in reducing opioid use is lacking. they said.

Dr. Campbell and her associates cited several important limitations. Since cannabis use was primarily illicit, it’s unlikely that it was used under medical supervision. Also, the study only gauged frequency of use on a per-day basis. “We do not know if some people used once in a day or more than once. Likewise, we do not know what type of cannabis the participants used. ... This fact matters, as cannabis varies in strength and, as with any analgesia, the dose needs to be matched to the severity of pain experienced,” the team said.

The subjects were a median age of 58 years at baseline, and 56% were women. They had been prescribed a strong opioid for a median of 4 years at study entry and were on a median oral morphine equivalent dose of 75 mg/day, which fell to 57 mg/day at the study’s conclusion. About 62% of the subjects reported neuropathic pain.

The work was funded by the Australian government, and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Dr. Campbell reported grants from Reckitt Benckiser.

SOURCE: Campbell G et al. Lancet Public Health. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30110-5.

FROM THE LANCET PUBLIC HEALTH

Key clinical point: Cannabis did not improve outcomes or reduce prescription opioid use among 1,514 Australians with chronic noncancer pain.

Major finding: Pain severity scores on the 10-point Brief Pain Inventory were 4.7 points at the end of the study among nonusers, compared with 5.3 among daily or near-daily users.

Study details: A 4-year observational, prospective investigation.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the Australian government and the National Health and Medical Research Council. The study lead reported grants from Reckitt Benckiser.

Source: Campbell G et al. Lancet Public Health. 2018 Jul. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30110-5.

Epinephrine for cardiac arrest: Better survival, more brain damage

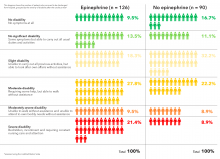

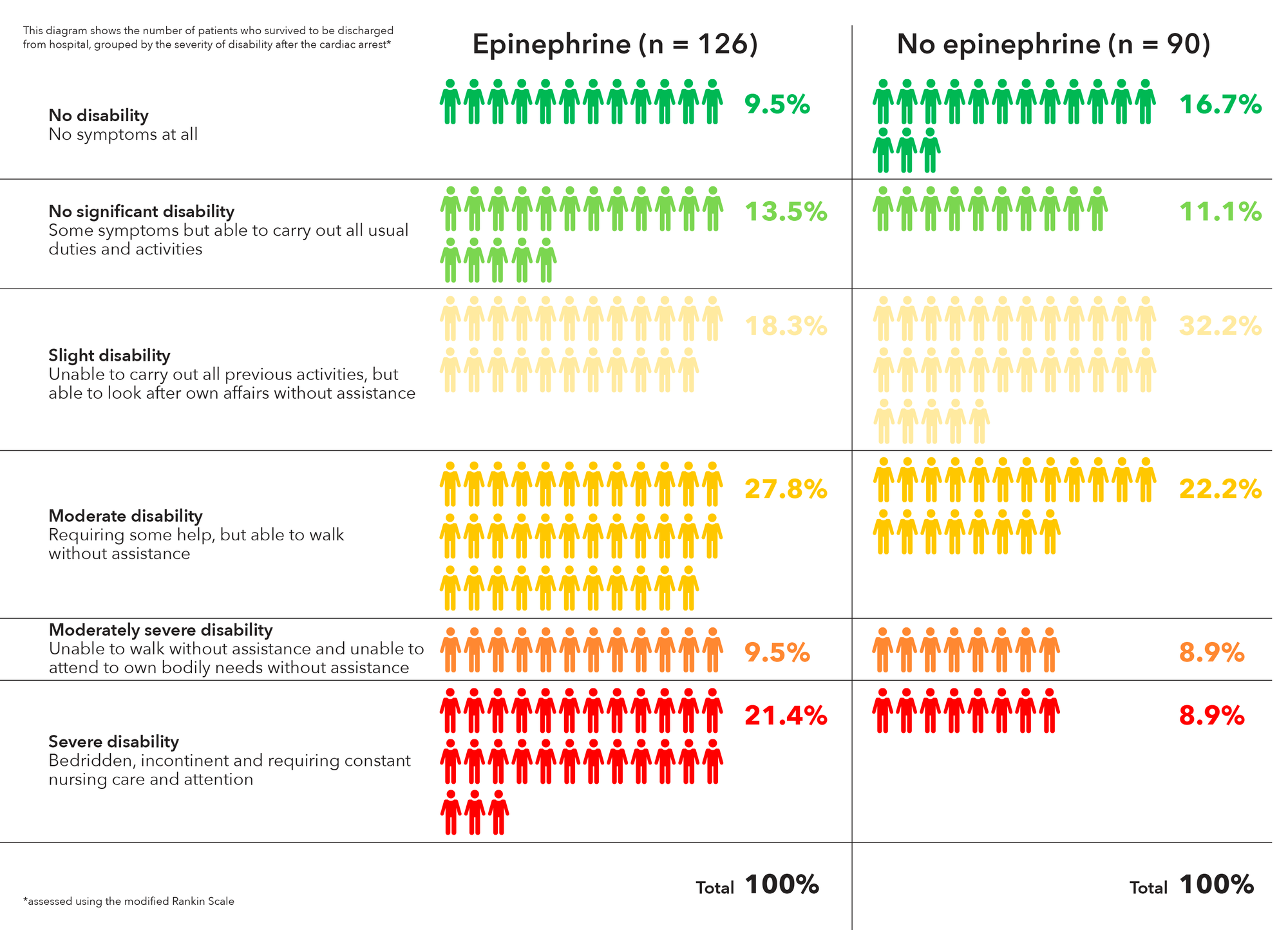

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.