User login

‘Obesity paradox’ in AFib challenged as mortality climbs with BMI

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

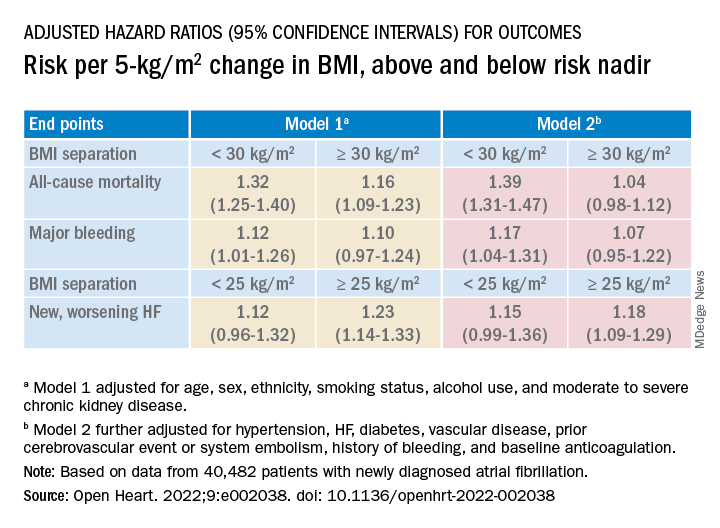

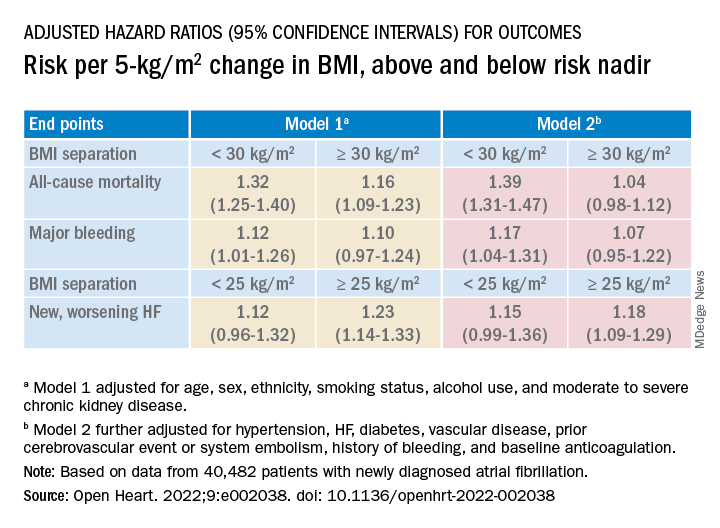

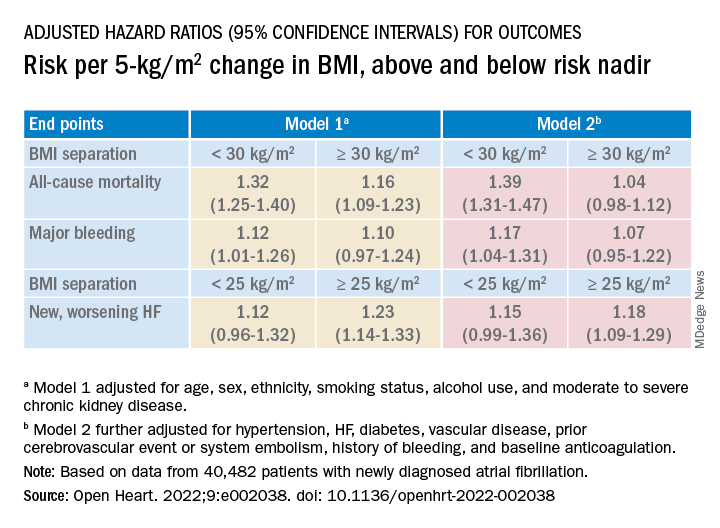

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) is U-shaped, with the risk highest in those who are underweight or severely obese and lowest in patients defined simply as obese, a registry analysis suggests. It also showed a similar relationship between BMI and risk for new or worsening heart failure (HF).

Mortality bottomed out at a BMI of about 30-35 kg/m2, which suggests that mild obesity was protective, compared even with “normal-weight” or “overweight” BMI. Still, mortality went up sharply from there with rising BMI.

But higher BMI, a surrogate for obesity, apparently didn’t worsen outcomes by itself. The risk for death from any cause at higher obesity levels was found to depend a lot on related risk factors and comorbidities when the analysis controlled for conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

The findings suggest an inverse relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in AFib only for patients with BMI less than about 30. They therefore argue against any “obesity paradox” in AFib that posits consistently better survival with increasing levels of obesity, say researchers, based on their analysis of patients with new-onset AFib in the GARFIELD-AF registry.

“It’s common practice now for clinicians to discuss weight within a clinic setting when they’re talking to their AFib patients,” observed Christian Fielder Camm, BM, BCh, University of Oxford (England), and Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, Reading, England. So studies suggesting an inverse association between BMI and AFib-related risk can be a concern.

Such studies “seem to suggest that once you’ve got AFib, maintaining a high or very high BMI may in some way be protective – which is contrary to what would seem to make sense and certainly contrary to what our results have shown,” Dr. Camm told this news organization.

“I think that having further evidence now to suggest, actually, that greater BMI is associated with a greater risk of all-cause mortality and heart failure helps reframe that discussion at the physician-patient interaction level more clearly, and ensures that we’re able to talk to our patients appropriately about risks associated with BMI and atrial fibrillation,” said Dr. Camm, who is lead author on the analysis published in Open Heart.

“Obesity is a cause of most cardiovascular diseases, but [these] data would support that being overweight or having mild obesity does not increase the risk,” observed Carl J. Lavie, MD, of the John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans, La., and the Ochsner Clinical School at the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

“At a BMI of 40, it’s very important for them to lose weight for their long-term prognosis,” Dr. Lavie noted, but “at a BMI of 30, the important thing would be to prevent further weight gain. And if they could keep their BMI of 30, they should have a good prognosis. Their prognosis would be particularly good if they didn’t gain weight and put themselves in a more extreme obesity class that is associated with worse risk.”

The current analysis, Dr. Lavie said, “is way better than the AFFIRM study,” which yielded an obesity-paradox report on its patients with AFib about a dozen years ago. “It’s got more data, more numbers, more statistical power,” and breaks BMI into more categories.

That previous analysis based on the influential AFFIRM randomized trial separated its 4,060 patients with AFib into normal (BMI, 18.5-25), overweight (BMI, 25-30), and obese (BMI, > 30) categories, per the convention at the time. It concluded that “obese patients with atrial fibrillation appear to have better long-term outcomes than nonobese patients.”

Bleeding risk on oral anticoagulants

Also noteworthy in the current analysis, variation in BMI didn’t seem to affect mortality or risk for major bleeding or nonhemorrhagic stroke according to choice of oral anticoagulant – whether a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or a vitamin K antagonist (VKA).

“We saw that even in the obese and extremely obese group, all-cause mortality was lower in the group taking NOACs, compared with taking warfarin,” Dr. Camm observed, “which goes against the idea that we would need any kind of dose adjustments for increased BMI.”

Indeed, the report notes, use of NOACs, compared with VKA, was associated with a 23% drop in risk for death among patients who were either normal weight or overweight and also in those who were obese or extremely obese.

Those findings “are basically saying that the NOACs look better than warfarin regardless of weight,” agreed Dr. Lavie. “The problem is that the study is not very powered.”

Whereas the benefits of NOACs, compared to VKA, seem similar for patients with a BMI of 30 or 34, compared with a BMI of 23, for example, “none of the studies has many people with 50 BMI.” Many clinicians “feel uncomfortable giving the same dose of NOAC to somebody who has a 60 BMI,” he said. At least with warfarin, “you can check the INR [international normalized ratio].”

The current analysis included 40,482 patients with recently diagnosed AFib and at least one other stroke risk factor from among the registry’s more than 50,000 patients from 35 countries, enrolled from 2010 to 2016. They were followed for 2 years.

The 703 patients with BMI under 18.5 at AFib diagnosis were classified per World Health Organization definitions as underweight; the 13,095 with BMI 18.5-25 as normal weight; the 15,043 with BMI 25-30 as overweight; the 7,560 with BMI 30-35 as obese; and the 4,081 with BMI above 35 as extremely obese. Their ages averaged 71 years, and 55.6% were men.

BMI effects on different outcomes

Relationships between BMI and all-cause mortality and between BMI and new or worsening HF emerged as U-shaped, the risk climbing with both increasing and decreasing BMI. The nadir BMI for risk was about 30 in the case of mortality and about 25 for new or worsening HF.

The all-cause mortality risk rose by 32% for every 5 BMI points lower than a BMI of 30, and by 16% for every 5 BMI points higher than 30, in a partially adjusted analysis. The risk for new or worsening HF rose significantly with increasing but not decreasing BMI, and the reverse was observed for the endpoint of major bleeding.

The effect of BMI on all-cause mortality was “substantially attenuated” when the analysis was further adjusted with “likely mediators of any association between BMI and outcomes,” including hypertension, diabetes, HF, cerebrovascular events, and history of bleeding, Dr. Camm said.

That blunted BMI-mortality relationship, he said, “suggests that a lot of the effect is mediated through relatively traditional risk factors like hypertension and diabetes.”

The 2010 AFFIRM analysis by BMI, Dr. Lavie noted, “didn’t even look at the underweight; they actually threw them out.” Yet, such patients with AFib, who tend to be extremely frail or have chronic diseases or conditions other than the arrhythmia, are common. A take-home of the current study is that “the underweight with atrial fibrillation have a really bad prognosis.”

That message isn’t heard as much, he observed, “but is as important as saying that BMI 30 has the best prognosis. The worst prognosis is with the underweight or the really extreme obese.”

Dr. Camm discloses research funding from the British Heart Foundation. Disclosures for the other authors are in the report. Dr. Lavie has previously disclosed serving as a speaker and consultant for PAI Health and DSM Nutritional Products and is the author of “The Obesity Paradox: When Thinner Means Sicker and Heavier Means Healthier” (Avery, 2014).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OPEN HEART

Phase 3 data: Zanubrutinib bests standard CLL treatment

At a median follow-up of 26.2 months, progression to worsening disease or death was much lower in patients with these conditions who took zanubrutinib (Brukinsa), compared with those who took bendamustine-rituximab (hazard ratio. 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-0.63; P < .00011). The study was published in The Lancet Oncology.

Researchers already knew that ibrutinib, another BTKi, improves progression-free survival, study coauthor Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, professor of medical oncology at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, said in an interview. “Now we confirmed that the same advantage can be seen” in zanubrutinib.

According to Dr. Ghia, bendamustine-rituximab has long been a standard treatment in blood cancers and is considered well tolerated and inexpensive. But BTKis such as first-in-line ibrutinib have shown better results, he said, “and progressively, we are going to abandon bendamustine-rituximab.”

However, ibrutinib causes significant adverse effects such as bleeding, worsening hypertension and arrhythmia, he noted. As a result, second-generation BTKi such as zanubrutinib have entered the picture. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2019 for mantle cell lymphoma, and it has since been approved for Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia and marginal zone lymphoma.

In 2021, an interim analysis in a trial of the drug in patients with previously treated CLL, compared with ibrutinib, found that “zanubrutinib was shown to have a superior response rate, an improved PFS, and a lower rate of atrial fibrillation/flutter.”

The drug’s manufacturer, BeiGene, launched the new open-label, multicenter study, in a bid for FDA approval of the drug as a frontline treatment for CLL and SLL. More than 150 hospitals in 14 countries participated in the trial from 2017 to 2019.

The subjects were all adults and at least 65 years old or with comorbidities; None had the genetic trait del(17)(p13.1); 241 were assigned to take zanubrutinib and 238 to bendamustine-rituximab. Another group consisted of 111 patients with CLL and del(17)(p13·1). According to the study authors, these patients are especially difficult to treat.

The vast majority of patients were White (92%-95% depending on group) and male (61%-71%); 90%-92% had CLL.

At follow-up, there was no difference in overall survival between the main zanubrutinib and bendamustine-rituximab groups; 29 (12%) of the 241 patients in the zanubrutinib group and 57 (24%) of 238 patients in the bendamustine-rituximab group had progressed or died (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.27-0.66; P < .00011). Adverse events leading to discontinuation were more common in the bendamustine-rituximab group (14%) versus zanubrutinib (8%).

In the third group, which only received zanubrutinib, 14% of patients died at median follow-up of 30.5 months; 98% of patients had adverse effects, and 5% discontinued treatment.

The researchers wrote that “zanubrutinib showed superior progression-free survival versus bendamustine-rituximab in older patients or those with comorbidities with untreated CLL, with a low incidence of cardiac arrhythmia. Similar efficacy was observed in patients with del(17p)–positive disease.”

The study didn’t examine cost; zanubrutinib is quite expensive.

In an interview, hematologist-oncologist Anthony Mato, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said the new study is important although not surprising, since other medications in the same class have shown similar results. Zanubrutinib is an alternative to ibrutinib, although the latter remains “an excellent drug,” he said.

“The era of chemotherapy being a first choice is over,” he said. “We’ve had several randomized studies that show targeted therapies are better tolerated and have better outcomes. We now need to look through the choices to decide which one of these good options are the best for our patients.”

In an interview, hematologist-oncologist Joanna Rhodes, MD, of Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y., highlighted the side effect profile of zanubrutinib, noting that it is low and resembles that of other BTKis, making it “another excellent treatment option.”

“We are seeing that bruising, upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and arthralgias are the most common side effects,” she said. “Bleeding also is a common side effect, which is consistent across the class of BTKis, with 5% of patients developing a major bleed. Also, 3% of patients treated with zanubrutinib developed atrial fibrillation, which is consistent with data from other trials. Treatment discontinuation rates were low (8%).”

The study was funded by BeiGene. The authors reported multiple disclosures. Dr. Mato reported research or consulting relationships with BeiGene, AstraZeneca, and AbbVie. Dr. Rhodes reported multiple research or consulting relationships with Abbvie, BeiGene, Genentech, and others.

At a median follow-up of 26.2 months, progression to worsening disease or death was much lower in patients with these conditions who took zanubrutinib (Brukinsa), compared with those who took bendamustine-rituximab (hazard ratio. 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-0.63; P < .00011). The study was published in The Lancet Oncology.

Researchers already knew that ibrutinib, another BTKi, improves progression-free survival, study coauthor Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, professor of medical oncology at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, said in an interview. “Now we confirmed that the same advantage can be seen” in zanubrutinib.

According to Dr. Ghia, bendamustine-rituximab has long been a standard treatment in blood cancers and is considered well tolerated and inexpensive. But BTKis such as first-in-line ibrutinib have shown better results, he said, “and progressively, we are going to abandon bendamustine-rituximab.”

However, ibrutinib causes significant adverse effects such as bleeding, worsening hypertension and arrhythmia, he noted. As a result, second-generation BTKi such as zanubrutinib have entered the picture. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2019 for mantle cell lymphoma, and it has since been approved for Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia and marginal zone lymphoma.

In 2021, an interim analysis in a trial of the drug in patients with previously treated CLL, compared with ibrutinib, found that “zanubrutinib was shown to have a superior response rate, an improved PFS, and a lower rate of atrial fibrillation/flutter.”

The drug’s manufacturer, BeiGene, launched the new open-label, multicenter study, in a bid for FDA approval of the drug as a frontline treatment for CLL and SLL. More than 150 hospitals in 14 countries participated in the trial from 2017 to 2019.

The subjects were all adults and at least 65 years old or with comorbidities; None had the genetic trait del(17)(p13.1); 241 were assigned to take zanubrutinib and 238 to bendamustine-rituximab. Another group consisted of 111 patients with CLL and del(17)(p13·1). According to the study authors, these patients are especially difficult to treat.

The vast majority of patients were White (92%-95% depending on group) and male (61%-71%); 90%-92% had CLL.

At follow-up, there was no difference in overall survival between the main zanubrutinib and bendamustine-rituximab groups; 29 (12%) of the 241 patients in the zanubrutinib group and 57 (24%) of 238 patients in the bendamustine-rituximab group had progressed or died (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.27-0.66; P < .00011). Adverse events leading to discontinuation were more common in the bendamustine-rituximab group (14%) versus zanubrutinib (8%).

In the third group, which only received zanubrutinib, 14% of patients died at median follow-up of 30.5 months; 98% of patients had adverse effects, and 5% discontinued treatment.

The researchers wrote that “zanubrutinib showed superior progression-free survival versus bendamustine-rituximab in older patients or those with comorbidities with untreated CLL, with a low incidence of cardiac arrhythmia. Similar efficacy was observed in patients with del(17p)–positive disease.”

The study didn’t examine cost; zanubrutinib is quite expensive.

In an interview, hematologist-oncologist Anthony Mato, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said the new study is important although not surprising, since other medications in the same class have shown similar results. Zanubrutinib is an alternative to ibrutinib, although the latter remains “an excellent drug,” he said.

“The era of chemotherapy being a first choice is over,” he said. “We’ve had several randomized studies that show targeted therapies are better tolerated and have better outcomes. We now need to look through the choices to decide which one of these good options are the best for our patients.”

In an interview, hematologist-oncologist Joanna Rhodes, MD, of Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y., highlighted the side effect profile of zanubrutinib, noting that it is low and resembles that of other BTKis, making it “another excellent treatment option.”

“We are seeing that bruising, upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and arthralgias are the most common side effects,” she said. “Bleeding also is a common side effect, which is consistent across the class of BTKis, with 5% of patients developing a major bleed. Also, 3% of patients treated with zanubrutinib developed atrial fibrillation, which is consistent with data from other trials. Treatment discontinuation rates were low (8%).”

The study was funded by BeiGene. The authors reported multiple disclosures. Dr. Mato reported research or consulting relationships with BeiGene, AstraZeneca, and AbbVie. Dr. Rhodes reported multiple research or consulting relationships with Abbvie, BeiGene, Genentech, and others.

At a median follow-up of 26.2 months, progression to worsening disease or death was much lower in patients with these conditions who took zanubrutinib (Brukinsa), compared with those who took bendamustine-rituximab (hazard ratio. 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.28-0.63; P < .00011). The study was published in The Lancet Oncology.

Researchers already knew that ibrutinib, another BTKi, improves progression-free survival, study coauthor Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, professor of medical oncology at Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan, said in an interview. “Now we confirmed that the same advantage can be seen” in zanubrutinib.

According to Dr. Ghia, bendamustine-rituximab has long been a standard treatment in blood cancers and is considered well tolerated and inexpensive. But BTKis such as first-in-line ibrutinib have shown better results, he said, “and progressively, we are going to abandon bendamustine-rituximab.”

However, ibrutinib causes significant adverse effects such as bleeding, worsening hypertension and arrhythmia, he noted. As a result, second-generation BTKi such as zanubrutinib have entered the picture. The Food and Drug Administration approved it in 2019 for mantle cell lymphoma, and it has since been approved for Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia and marginal zone lymphoma.

In 2021, an interim analysis in a trial of the drug in patients with previously treated CLL, compared with ibrutinib, found that “zanubrutinib was shown to have a superior response rate, an improved PFS, and a lower rate of atrial fibrillation/flutter.”

The drug’s manufacturer, BeiGene, launched the new open-label, multicenter study, in a bid for FDA approval of the drug as a frontline treatment for CLL and SLL. More than 150 hospitals in 14 countries participated in the trial from 2017 to 2019.

The subjects were all adults and at least 65 years old or with comorbidities; None had the genetic trait del(17)(p13.1); 241 were assigned to take zanubrutinib and 238 to bendamustine-rituximab. Another group consisted of 111 patients with CLL and del(17)(p13·1). According to the study authors, these patients are especially difficult to treat.

The vast majority of patients were White (92%-95% depending on group) and male (61%-71%); 90%-92% had CLL.

At follow-up, there was no difference in overall survival between the main zanubrutinib and bendamustine-rituximab groups; 29 (12%) of the 241 patients in the zanubrutinib group and 57 (24%) of 238 patients in the bendamustine-rituximab group had progressed or died (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.27-0.66; P < .00011). Adverse events leading to discontinuation were more common in the bendamustine-rituximab group (14%) versus zanubrutinib (8%).

In the third group, which only received zanubrutinib, 14% of patients died at median follow-up of 30.5 months; 98% of patients had adverse effects, and 5% discontinued treatment.

The researchers wrote that “zanubrutinib showed superior progression-free survival versus bendamustine-rituximab in older patients or those with comorbidities with untreated CLL, with a low incidence of cardiac arrhythmia. Similar efficacy was observed in patients with del(17p)–positive disease.”

The study didn’t examine cost; zanubrutinib is quite expensive.

In an interview, hematologist-oncologist Anthony Mato, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York said the new study is important although not surprising, since other medications in the same class have shown similar results. Zanubrutinib is an alternative to ibrutinib, although the latter remains “an excellent drug,” he said.

“The era of chemotherapy being a first choice is over,” he said. “We’ve had several randomized studies that show targeted therapies are better tolerated and have better outcomes. We now need to look through the choices to decide which one of these good options are the best for our patients.”

In an interview, hematologist-oncologist Joanna Rhodes, MD, of Northwell Health in Hempstead, N.Y., highlighted the side effect profile of zanubrutinib, noting that it is low and resembles that of other BTKis, making it “another excellent treatment option.”

“We are seeing that bruising, upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhea, and arthralgias are the most common side effects,” she said. “Bleeding also is a common side effect, which is consistent across the class of BTKis, with 5% of patients developing a major bleed. Also, 3% of patients treated with zanubrutinib developed atrial fibrillation, which is consistent with data from other trials. Treatment discontinuation rates were low (8%).”

The study was funded by BeiGene. The authors reported multiple disclosures. Dr. Mato reported research or consulting relationships with BeiGene, AstraZeneca, and AbbVie. Dr. Rhodes reported multiple research or consulting relationships with Abbvie, BeiGene, Genentech, and others.

FROM THE LANCET ONCOLOGY

Safety Profile of Mutant EGFR-TK Inhibitors in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-analysis

Lung cancer has been the leading cause of cancer-related mortality for decades. It is also predicted to remain as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality through 2030.1 Platinum-based chemotherapy, including carboplatin and paclitaxel, was introduced 3 decades ago and revolutionized the management of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A more recent advancement has been mutant epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) inhibitors.1 EGFR is a transmembrane protein that functions by transducing essential growth factor signaling from the extracellular milieu to the cell. As 60% of the advanced NSCLC expresses this receptor, blocking the mutant EGFR receptor was a groundbreaking development in the management of advanced NSCLC.2 Development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors has revolutionized the management of advanced NSCLC. This study was conducted to determine the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in the management of advanced NSCLC.

Methods

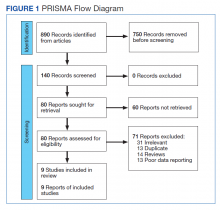

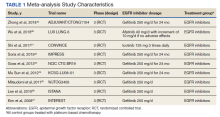

This meta-analysis was conducted according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The findings are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Two authors (MZ and MM) performed a systematic literature search using databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library using the medical search terms and their respective entry words with the following search strategy: safety, “mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors,” advanced, “non–small cell,” “lung cancer,” “adverse effect,” and literature. Additionally, unpublished trials were identified from clinicaltrials.gov, and references of all pertinent articles were also scrutinized to ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies. The search was completed on June 1, 2021, and we only included studies available in English. Two authors (MM and MZ) independently screened the search results in a 2-step process based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, 890 articles were evaluated for relevance on title and abstract level, followed by full-text screening of the final list of 140 articles. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or third-party review, and a total of 9 articles were included in the study.

The following eligibility criteria were used: original articles reporting adverse effects (AEs) of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. All the patients included in the study had an EGFR mutation but randomly assigned to either treatment or control group. All articles with subjective data on mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors AEs in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy were included in the analysis. Only 9 articles qualified the aforementioned selection criteria for eligibility. All qualifying studies were nationwide inpatient or pooled clinical trials data. The reasons for exclusion of the other 71 articles were irrelevant (n = 31), duplicate (n = 13), reviews (n = 14), and poor data reporting (n = 12). Out of the 9 included studies, 9 studies showed correlation of AEs, including rash, diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue. Seven studies showed correlation of AEs including neutropenia, anorexia, and vomiting. Six studies showed correlation of anemia, cough, and stomatitis. Five studies showed correlation of elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and leucopenia. Four studies showed correlation of fever between mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy.

The primary endpoints were reported AEs including rash, diarrhea, elevated ALT, elevated AST, stomatitis, nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever, respectively. Data on baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were then extracted, and summary tables were created. Summary estimates of the clinical endpoints were then calculated with risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was examined with the Cochran Q I2 statistic which can be defined as low (25% to 50%), moderate (50% to 75%), or high (> 75%). Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software CMA Version 3.0.

Results

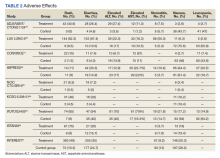

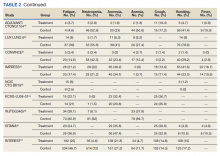

A total of 9 studies including 3415 patients (1775 in EGFR-TK inhibitor treatment group while 1640 patients in platinum-based chemotherapy control group) were included in the study. All 9 studies were phase III randomized control clinical trials conducted to compare the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC. Mean age was 61 years in both treatment and control groups. Further details on study and participant characteristics and safety profile including AEs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. No evidence of publication bias was found.

Rash developed in 45.8% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs only 5.6% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 7.38 with the 95% CI noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher rash event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 2).

Diarrhea occurred in 33.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 13.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 2.63 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher diarrheal rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 3).

Elevated ALT levels developed in 27.9% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 15.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher ALT levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 4).

Elevated AST levels occurred in 40.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 12.8% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.77 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming elevated AST levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 5).

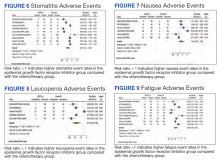

Stomatitis developed in 17.2% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 7.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.53 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher stomatitis event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 6).

Nausea occurred in 16.5% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 42.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher nausea rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 7).

Leucopenia developed in 9.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 51.3% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.18 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher leucopenia incidence in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 8).

Fatigue was reported in 17% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 29.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.59 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fatigue rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 9).

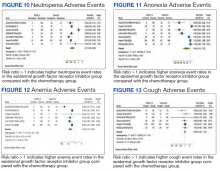

Neutropenia developed in 6.1% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 48.2% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.11 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher neutropenia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 10).

Anorexia developed in 21.3% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 31.4% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.44 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 11).

Anemia occurred in 8.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 32.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.24 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 12).

Cough was reported in 17.8% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 18.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.99 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming slightly higher cough rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 13).

Vomiting developed in 11% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.35 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher vomiting rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 14).

Fever occurred in 5.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.41 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fever rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 15).

Discussion

Despite the advancement in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC, lung cancer stays as most common cause of cancer-related death in North America and European countries, as patients usually have an advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.3 In the past, platinum-based chemotherapy remained the standard of care for most of the patients affected with advanced NSCLC, but the higher recurrence rate and increase in frequency and intensity of AEs with platinum-based chemotherapy led to the development of targeted therapy for NSCLC, one of which includes

Smoking is the most common reversible risk factor associated with lung cancer. The EURTAC trial was the first perspective study in this regard, which compared safety and efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. Results analyzed in this study were in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors except in the group of former smokers.5 On the contrary, the OPTIMAL trial showed results in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors both in active and former smokers; this trial also confirmed the efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in European and Asian populations, confirming the rationale for routine testing of EGFR mutation in all the patients being diagnosed with advanced NSCLC.6 Similarly, osimertinib is one of the most recent mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in patients with EGFR-positive receptors.

According to the FLAURA trial, patients receiving osimertinib showed significantly longer progression-free survival compared with platinum-based chemotherapy and early mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors. Median progression-free survival was noted to be 18.9 months, which showed 54% lower risk of disease progression in the treatment group receiving osimertinib.7 The ARCHER study emphasized a significant improvement in overall survival as well as progression-free survival among a patient population receiving dacomitinib compared with platinum-based chemotherapy.8,9

Being a potent targeted therapy, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors do come with some AEs including diarrhea, which was seen in 33.6% of the patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study vs 53% in the chemotherapy group, as was observed in the study conducted by Pless and colleagues.10 Similarly, only 16.5% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed nausea compared with 66% being observed in patients receiving chemotherapy. Correspondingly, only a small fraction of patients (9.7%) receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed leucopenia, which was 10 times less reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with patients receiving chemotherapy having a percentage of 100%. A similar trend was reported for neutropenia and anemia in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with an incidence of 6.1% and 8.7%, compared with the platinum-based chemotherapy group in which the incidence was found to be 80% and 100%, respectively. It was concluded that platinum-based chemotherapy had played a vital role in the treatment of advanced NSCLC but at an expense of serious and severe AEs which led to discontinuation or withdrawal of treatment, leading to relapse and recurrence of lung cancer.10,11

Zhong and colleagues conducted a phase 2 randomized clinical trial comparing mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. They concluded that in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy, incidence of rash, vomiting, anorexia, neutropenia, and nausea were 29.4%, 47%, 41.2%, 55.8%, and 32.4% compared with 45.8%, 11%, 21.3%, 6.1%, and 16.5%, respectively, reported in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC.12

Another study was conducted in 2019 by Noronha and colleagues to determine the impact of platinum-based chemotherapy combined with gefitinib on patients with advanced NSCLC.13 They concluded that 70% of the patients receiving combination treatment developed rash, which was significantly higher compared with 45.8% patients receiving the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors alone in our study. Also, 56% of patients receiving combination therapy developed diarrhea vs 33.6% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors only. Similarly, 96% of patients in the combination therapy group developed some degree of anemia compared with only 8.7% patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. In the same way, neutropenia was observed in 55% of patients receiving combination therapy vs 6.1% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors solely. They concluded that mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy increase the incidence of AEs of chemotherapy by many folds.13,14

Kato and colleagues conducted a study to determine the impact on AEs when erlotinib was combined with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors like bevacizumab, they stated that 98.7% of patient in combination therapy developed rash, the incidence of which was only 45.8% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was observed in our study. Similar trends were noticed with other AEs, including diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and elevated liver enzymes.15

With the latest advancements in the management of advanced NSCLC, nivolumab, a programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor, was developed and either used as monotherapy in patients with PD-L1 expression or was combined with platinum-based chemotherapy regardless of PD-L1 expression.16,17 Patients expressing lower PD-L1 levels were not omitted from receiving nivolumab as no significant difference was noted in progression-free span and overall survival in patients receiving nivolumab irrespective of PD-L1 levels.15 Rash developed in 17% of patients after receiving nivolumab vs 45.8% patients being observed in our study. A similar trend was observed with diarrhea as only 17% of the population receiving nivolumab developed diarrhea compared with 33.6% of the population receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Likewise, only 9.9% of the patients receiving nivolumab developed nausea as an AE compared with 16.5% being observed in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Also, fatigue was observed in 14.4% of the population receiving nivolumab vs 17% observed in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was noticed in our study.7,8

Rizvi and colleagues conducted a study on the role of nivolumab when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC and reported that 40% of patients included in the study developed rash compared with 45.8% reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study. Similarly, only 13% of patients in the nivolumab group developed diarrhea vs 33.6% cases reported in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. Also, 7% of patients in the nivolumab group developed elevated ALT levels vs 27.9% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors included in our study, concluding that addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors like nivolumab to platinum-based chemotherapy does not increase the frequency of AEs.18

Conclusions

Our study focused on the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs platinum-based chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. Mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors are safer than platinum-based chemotherapy when compared for nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever. On the other end, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors cause slightly higher AEs, including rash, diarrhea, elevated AST and ALT levels, and stomatitis. However, considering that the development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors laid a foundation of targeted therapy, we recommend continuing using mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC especially in patients having mutant EGFR receptors. AEs caused by mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors are significant but are usually tolerable and can be avoided by reducing the dosage of it with each cycle or by skipping or delaying the dose until the patient is symptomatic.

1. Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913-2921. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155

2. da Cunha Santos G, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS. EGFR mutations and lung cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:49-69. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130206

3. Sgambato A, Casaluce F, Maione P, et al. The role of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the first-line treatment of advanced non small cell lung cancer patients harboring EGFR mutation. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(20):3337-3352. doi:10.2174/092986712801215973

4. Rossi A, Di Maio M. Platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer: optimal number of treatment cycles. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(6):653-660. doi:10.1586/14737140.2016.1170596

5. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non–small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239-246. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X

6. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non–small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):735-742. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X

7. Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113-125. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1713137

8. Mok TS, Cheng Y, Zhou X, et al. Improvement in overall survival in a randomized study that compared dacomitinib with gefitinib in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer and EGFR-activating mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2244-2250. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.7994

9. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947-957. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810699

10. Pless M, Stupp R, Ris HB, et al. Induction chemoradiation in stage IIIA/N2 non–small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9998):1049-1056. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60294-X

11. Albain KS, Rusch VW, Crowley JJ, et al. Concurrent cisplatin/etoposide plus chest radiotherapy followed by surgery for stages IIIA (N2) and IIIB non–small-cell lung cancer: mature results of Southwest Oncology Group phase II study 8805. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(8):1880-1892. doi:10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1880

12. Zhong WZ, Chen KN, Chen C, et al. Erlotinib versus gemcitabine plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant treatment of Stage IIIA-N2 EGFR-mutant non–small-cell lung cancer (EMERGING-CTONG 1103): a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(25):2235-2245. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.00075

13. Noronha V, Patil VM, Joshi A, et al. Gefitinib versus gefitinib plus pemetrexed and carboplatin chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(2):124-136. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01154

14. Noronha V, Prabhash K, Thavamani A, et al. EGFR mutations in Indian lung cancer patients: clinical correlation and outcome to EGFR targeted therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61561. Published 2013 Apr 19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061561

15. Kato T, Seto T, Nishio M, et al. Erlotinib plus bevacizumab phase ll study in patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (JO25567): updated safety results. Drug Saf. 2018;41(2):229-237. doi:10.1007/s40264-017-0596-0

16. Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020-2031. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910231

17. Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093-2104. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801946

18. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Brahmer JR, et al. Nivolumab in combination with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(25):2969-2979. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9861

19. Zhong WZ, Wang Q, Mao WM, et al. Gefitinib versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin as adjuvant treatment for stage II-IIIA (N1-N2) EGFR-mutant NSCLC: final overall survival analysis of CTONG1104 Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):713-722. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.01820

20. Yang JC, Sequist LV, Geater SL, et al. Clinical activity of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring uncommon EGFR mutations: a combined post-hoc analysis of LUX-Lung 2, LUX-Lung 3, and LUX-Lung 6. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):830-838. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00026-1

21. Shi YK, Wang L, Han BH, et al. First-line icotinib versus cisplatin/pemetrexed plus pemetrexed maintenance therapy for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (CONVINCE): a phase 3, open-label, randomized study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2443-2450. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx359

22. Soria JC, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, et al. Gefitinib plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on first-line gefitinib (IMPRESS): a phase 3 randomized trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):990-998 doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00121-7

23. Goss GD, O’Callaghan C, Lorimer I, et al. Gefitinib versus placebo in completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the NCIC CTG BR19 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3320-3326. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1816

24. Sun JM, Lee KH, Kim SW, et al. Gefitinib versus pemetrexed as second-line treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (KCSG-LU08-01): an open-label, phase 3 trial. Cancer. 2012;118(24):6234-6242. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1816

25. Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):121-128. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X

26. Lee DH, Park K, Kim JH, Lee JS, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gefitinib versus docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer patients who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(4):1307-1314. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1903

27. Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomized phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;22;372(9652):1809-1818. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4

Lung cancer has been the leading cause of cancer-related mortality for decades. It is also predicted to remain as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality through 2030.1 Platinum-based chemotherapy, including carboplatin and paclitaxel, was introduced 3 decades ago and revolutionized the management of advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). A more recent advancement has been mutant epidermal growth factor receptor–tyrosine kinase (EGFR-TK) inhibitors.1 EGFR is a transmembrane protein that functions by transducing essential growth factor signaling from the extracellular milieu to the cell. As 60% of the advanced NSCLC expresses this receptor, blocking the mutant EGFR receptor was a groundbreaking development in the management of advanced NSCLC.2 Development of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors has revolutionized the management of advanced NSCLC. This study was conducted to determine the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in the management of advanced NSCLC.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The findings are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Two authors (MZ and MM) performed a systematic literature search using databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and Cochrane Library using the medical search terms and their respective entry words with the following search strategy: safety, “mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors,” advanced, “non–small cell,” “lung cancer,” “adverse effect,” and literature. Additionally, unpublished trials were identified from clinicaltrials.gov, and references of all pertinent articles were also scrutinized to ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies. The search was completed on June 1, 2021, and we only included studies available in English. Two authors (MM and MZ) independently screened the search results in a 2-step process based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. First, 890 articles were evaluated for relevance on title and abstract level, followed by full-text screening of the final list of 140 articles. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or third-party review, and a total of 9 articles were included in the study.

The following eligibility criteria were used: original articles reporting adverse effects (AEs) of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. All the patients included in the study had an EGFR mutation but randomly assigned to either treatment or control group. All articles with subjective data on mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors AEs in patients with advanced NSCLC compared with control groups receiving platinum-based chemotherapy were included in the analysis. Only 9 articles qualified the aforementioned selection criteria for eligibility. All qualifying studies were nationwide inpatient or pooled clinical trials data. The reasons for exclusion of the other 71 articles were irrelevant (n = 31), duplicate (n = 13), reviews (n = 14), and poor data reporting (n = 12). Out of the 9 included studies, 9 studies showed correlation of AEs, including rash, diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue. Seven studies showed correlation of AEs including neutropenia, anorexia, and vomiting. Six studies showed correlation of anemia, cough, and stomatitis. Five studies showed correlation of elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and leucopenia. Four studies showed correlation of fever between mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors and platinum-based chemotherapy.

The primary endpoints were reported AEs including rash, diarrhea, elevated ALT, elevated AST, stomatitis, nausea, leucopenia, fatigue, neutropenia, anorexia, anemia, cough, vomiting, and fever, respectively. Data on baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were then extracted, and summary tables were created. Summary estimates of the clinical endpoints were then calculated with risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was examined with the Cochran Q I2 statistic which can be defined as low (25% to 50%), moderate (50% to 75%), or high (> 75%). Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software CMA Version 3.0.

Results

A total of 9 studies including 3415 patients (1775 in EGFR-TK inhibitor treatment group while 1640 patients in platinum-based chemotherapy control group) were included in the study. All 9 studies were phase III randomized control clinical trials conducted to compare the safety profile of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in patients with advanced NSCLC. Mean age was 61 years in both treatment and control groups. Further details on study and participant characteristics and safety profile including AEs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. No evidence of publication bias was found.

Rash developed in 45.8% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors vs only 5.6% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 7.38 with the 95% CI noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher rash event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 2).

Diarrhea occurred in 33.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 13.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 2.63 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher diarrheal rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 3).

Elevated ALT levels developed in 27.9% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 15.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher ALT levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 4).

Elevated AST levels occurred in 40.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors treatment group vs 12.8% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.77 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming elevated AST levels in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 5).

Stomatitis developed in 17.2% of patients in the treatment group receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with 7.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 1.53 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher stomatitis event rates in patients receiving EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 6).

Nausea occurred in 16.5% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 42.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.37 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher nausea rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 7).

Leucopenia developed in 9.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 51.3% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.18 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher leucopenia incidence in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 8).

Fatigue was reported in 17% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 29.5% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.59 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fatigue rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 9).

Neutropenia developed in 6.1% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 48.2% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.11 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher neutropenia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 10).

Anorexia developed in 21.3% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 31.4% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.44 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 11).

Anemia occurred in 8.7% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 32.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.24 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher anorexia rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 12).

Cough was reported in 17.8% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 18.9% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.99 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming slightly higher cough rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with treatment for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 13).

Vomiting developed in 11% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group vs 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.35 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher vomiting rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 14).

Fever occurred in 5.6% of patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group compared with 30.1% of patients in the control group receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall RR of 0.41 and 95% CI was noted, which was statistically significant, confirming higher fever rates in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy compared with the treatment group for their advanced NSCLC (Figure 15).

Discussion

Despite the advancement in the treatment of metastatic NSCLC, lung cancer stays as most common cause of cancer-related death in North America and European countries, as patients usually have an advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.3 In the past, platinum-based chemotherapy remained the standard of care for most of the patients affected with advanced NSCLC, but the higher recurrence rate and increase in frequency and intensity of AEs with platinum-based chemotherapy led to the development of targeted therapy for NSCLC, one of which includes

Smoking is the most common reversible risk factor associated with lung cancer. The EURTAC trial was the first perspective study in this regard, which compared safety and efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. Results analyzed in this study were in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors except in the group of former smokers.5 On the contrary, the OPTIMAL trial showed results in favor of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors both in active and former smokers; this trial also confirmed the efficacy of mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in European and Asian populations, confirming the rationale for routine testing of EGFR mutation in all the patients being diagnosed with advanced NSCLC.6 Similarly, osimertinib is one of the most recent mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in patients with EGFR-positive receptors.

According to the FLAURA trial, patients receiving osimertinib showed significantly longer progression-free survival compared with platinum-based chemotherapy and early mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors. Median progression-free survival was noted to be 18.9 months, which showed 54% lower risk of disease progression in the treatment group receiving osimertinib.7 The ARCHER study emphasized a significant improvement in overall survival as well as progression-free survival among a patient population receiving dacomitinib compared with platinum-based chemotherapy.8,9

Being a potent targeted therapy, mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors do come with some AEs including diarrhea, which was seen in 33.6% of the patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors in our study vs 53% in the chemotherapy group, as was observed in the study conducted by Pless and colleagues.10 Similarly, only 16.5% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed nausea compared with 66% being observed in patients receiving chemotherapy. Correspondingly, only a small fraction of patients (9.7%) receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors developed leucopenia, which was 10 times less reported in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors compared with patients receiving chemotherapy having a percentage of 100%. A similar trend was reported for neutropenia and anemia in mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with an incidence of 6.1% and 8.7%, compared with the platinum-based chemotherapy group in which the incidence was found to be 80% and 100%, respectively. It was concluded that platinum-based chemotherapy had played a vital role in the treatment of advanced NSCLC but at an expense of serious and severe AEs which led to discontinuation or withdrawal of treatment, leading to relapse and recurrence of lung cancer.10,11

Zhong and colleagues conducted a phase 2 randomized clinical trial comparing mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors with platinum-based chemotherapy. They concluded that in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy, incidence of rash, vomiting, anorexia, neutropenia, and nausea were 29.4%, 47%, 41.2%, 55.8%, and 32.4% compared with 45.8%, 11%, 21.3%, 6.1%, and 16.5%, respectively, reported in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors for their advanced NSCLC.12

Another study was conducted in 2019 by Noronha and colleagues to determine the impact of platinum-based chemotherapy combined with gefitinib on patients with advanced NSCLC.13 They concluded that 70% of the patients receiving combination treatment developed rash, which was significantly higher compared with 45.8% patients receiving the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors alone in our study. Also, 56% of patients receiving combination therapy developed diarrhea vs 33.6% of patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors only. Similarly, 96% of patients in the combination therapy group developed some degree of anemia compared with only 8.7% patients in the mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors group included in our study. In the same way, neutropenia was observed in 55% of patients receiving combination therapy vs 6.1% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors solely. They concluded that mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors when combined with platinum-based chemotherapy increase the incidence of AEs of chemotherapy by many folds.13,14

Kato and colleagues conducted a study to determine the impact on AEs when erlotinib was combined with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors like bevacizumab, they stated that 98.7% of patient in combination therapy developed rash, the incidence of which was only 45.8% in patients receiving mutant EGFR-TK inhibitors as was observed in our study. Similar trends were noticed with other AEs, including diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, and elevated liver enzymes.15