User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Treatment for RA, SpA may not affect COVID-19 severity

Patients being treated for RA or spondyloarthritis who develop symptoms of COVID-19 do not appear to be at higher risk of respiratory or life-threatening complications, results from a new study in Italy suggest.

Such patients, the study authors wrote, do not need to be taken off their immunosuppressive medications if they develop COVID-19 symptoms.

In a letter published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, Sara Monti, MD, and colleagues in the rheumatology department of the Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico in San Matteo, Italy, described results from an observational cohort of 320 patients (68% women; mean age, 55 years) with RA or spondyloarthritis from a single outpatient clinic. The vast majority of subjects (92%) were taking biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD), including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, while the rest were taking targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARD).

Four patients in the cohort developed laboratory-confirmed COVID-19; another four developed symptoms highly suggestive of the disease but did not receive confirmatory testing, and five had contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case but did not develop symptoms of COVID-19.

Among the eight confirmed and suspected COVID-19 patients, only one was hospitalized. All temporarily withdrew bDMARD or tsDMARD treatment at symptom onset.

“To date, there have been no significant relapses of the rheumatic disease,” Dr. Monti and colleagues reported. “None of the patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 or with a highly suggestive clinical picture developed severe respiratory complications or died. Only one patient, aged 65, required admission to hospital and low-flow oxygen supplementation for a few days.”

The findings “do not allow any conclusions on the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic diseases, nor on the overall outcome of immunocompromised patients affected by COVID-19,” the investigators cautioned, adding that such patients should receive careful attention and follow-up. “However, our preliminary experience shows that patients with chronic arthritis treated with bDMARDs or tsDMARDs do not seem to be at increased risk of respiratory or life-threatening complications from SARS-CoV-2, compared with the general population.”

Dr. Monti and colleagues noted that, during previous outbreaks of other coronaviruses, no increased mortality was reported for people taking immunosuppressive drugs for a range of conditions, including autoimmune diseases.

“These data can support rheumatologists [in] avoiding the unjustifiable preventive withdrawal of DMARDs, which could lead to an increased risk of relapses and morbidity from the chronic rheumatological condition,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Monti and colleagues reported no outside funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Monti S et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 April 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217424.

Patients being treated for RA or spondyloarthritis who develop symptoms of COVID-19 do not appear to be at higher risk of respiratory or life-threatening complications, results from a new study in Italy suggest.

Such patients, the study authors wrote, do not need to be taken off their immunosuppressive medications if they develop COVID-19 symptoms.

In a letter published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, Sara Monti, MD, and colleagues in the rheumatology department of the Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico in San Matteo, Italy, described results from an observational cohort of 320 patients (68% women; mean age, 55 years) with RA or spondyloarthritis from a single outpatient clinic. The vast majority of subjects (92%) were taking biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD), including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, while the rest were taking targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARD).

Four patients in the cohort developed laboratory-confirmed COVID-19; another four developed symptoms highly suggestive of the disease but did not receive confirmatory testing, and five had contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case but did not develop symptoms of COVID-19.

Among the eight confirmed and suspected COVID-19 patients, only one was hospitalized. All temporarily withdrew bDMARD or tsDMARD treatment at symptom onset.

“To date, there have been no significant relapses of the rheumatic disease,” Dr. Monti and colleagues reported. “None of the patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 or with a highly suggestive clinical picture developed severe respiratory complications or died. Only one patient, aged 65, required admission to hospital and low-flow oxygen supplementation for a few days.”

The findings “do not allow any conclusions on the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic diseases, nor on the overall outcome of immunocompromised patients affected by COVID-19,” the investigators cautioned, adding that such patients should receive careful attention and follow-up. “However, our preliminary experience shows that patients with chronic arthritis treated with bDMARDs or tsDMARDs do not seem to be at increased risk of respiratory or life-threatening complications from SARS-CoV-2, compared with the general population.”

Dr. Monti and colleagues noted that, during previous outbreaks of other coronaviruses, no increased mortality was reported for people taking immunosuppressive drugs for a range of conditions, including autoimmune diseases.

“These data can support rheumatologists [in] avoiding the unjustifiable preventive withdrawal of DMARDs, which could lead to an increased risk of relapses and morbidity from the chronic rheumatological condition,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Monti and colleagues reported no outside funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Monti S et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 April 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217424.

Patients being treated for RA or spondyloarthritis who develop symptoms of COVID-19 do not appear to be at higher risk of respiratory or life-threatening complications, results from a new study in Italy suggest.

Such patients, the study authors wrote, do not need to be taken off their immunosuppressive medications if they develop COVID-19 symptoms.

In a letter published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, Sara Monti, MD, and colleagues in the rheumatology department of the Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico in San Matteo, Italy, described results from an observational cohort of 320 patients (68% women; mean age, 55 years) with RA or spondyloarthritis from a single outpatient clinic. The vast majority of subjects (92%) were taking biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD), including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, while the rest were taking targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARD).

Four patients in the cohort developed laboratory-confirmed COVID-19; another four developed symptoms highly suggestive of the disease but did not receive confirmatory testing, and five had contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case but did not develop symptoms of COVID-19.

Among the eight confirmed and suspected COVID-19 patients, only one was hospitalized. All temporarily withdrew bDMARD or tsDMARD treatment at symptom onset.

“To date, there have been no significant relapses of the rheumatic disease,” Dr. Monti and colleagues reported. “None of the patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 or with a highly suggestive clinical picture developed severe respiratory complications or died. Only one patient, aged 65, required admission to hospital and low-flow oxygen supplementation for a few days.”

The findings “do not allow any conclusions on the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with rheumatic diseases, nor on the overall outcome of immunocompromised patients affected by COVID-19,” the investigators cautioned, adding that such patients should receive careful attention and follow-up. “However, our preliminary experience shows that patients with chronic arthritis treated with bDMARDs or tsDMARDs do not seem to be at increased risk of respiratory or life-threatening complications from SARS-CoV-2, compared with the general population.”

Dr. Monti and colleagues noted that, during previous outbreaks of other coronaviruses, no increased mortality was reported for people taking immunosuppressive drugs for a range of conditions, including autoimmune diseases.

“These data can support rheumatologists [in] avoiding the unjustifiable preventive withdrawal of DMARDs, which could lead to an increased risk of relapses and morbidity from the chronic rheumatological condition,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Monti and colleagues reported no outside funding or financial conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Monti S et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 April 2. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217424.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

‘The kids will be all right,’ won’t they?

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

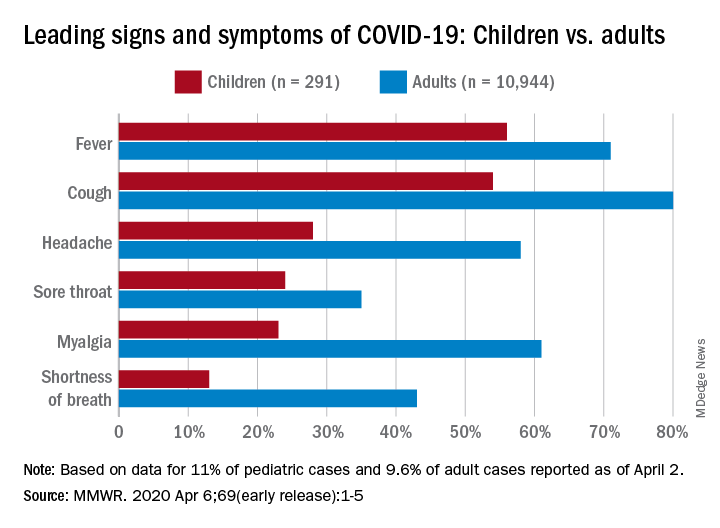

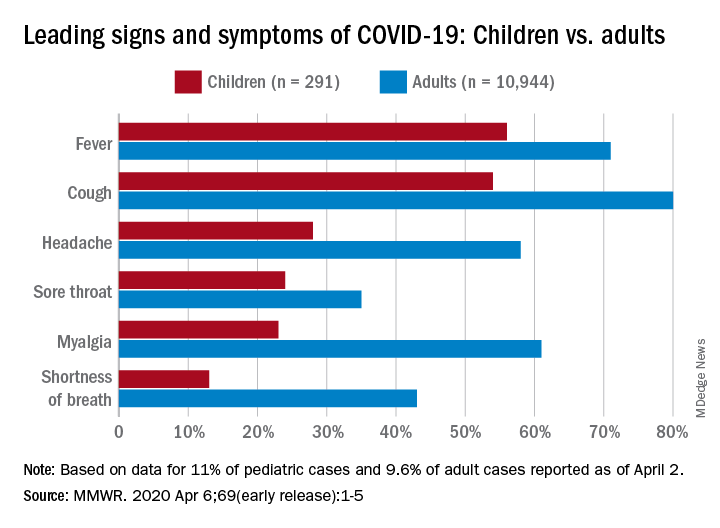

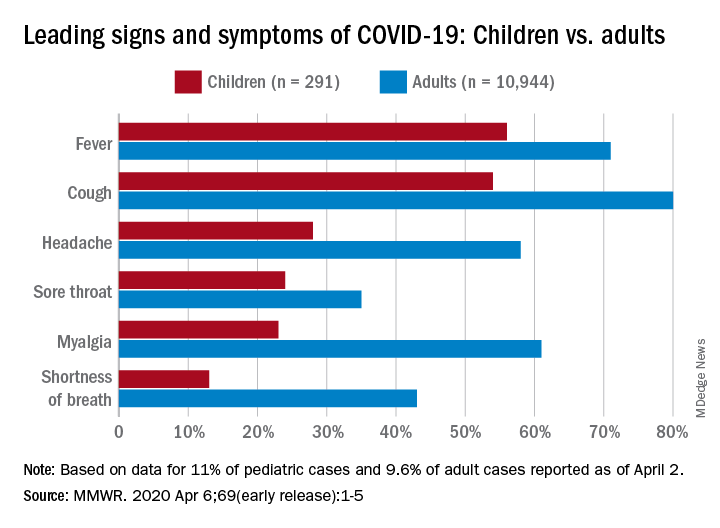

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

Pediatric patients and COVID-19

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects us in many ways. Pediatric patients, interestingly, are largely unaffected clinically by this disease. Less than 1% of documented infections occur in children under 10 years old, according to a review of over 72,000 cases from China.1 In that review, most children were asymptomatic or had mild illness, only three required intensive care, and only one death had been reported as of March 10, 2020. This is in stark contrast to the shocking morbidity and mortality statistics we are becoming all too familiar with on the adult side.

From a social standpoint, however, our pediatric patients’ lives have been turned upside down. Their schedules and routines upended, their education and friendships interrupted, and many are likely experiencing real anxiety and fear.2 For countless children, school is a major source of social, emotional, and nutritional support that has been cut off. Some will lose parents, grandparents, or other loved ones to this disease. Parents will lose jobs and will be unable to afford necessities. Pediatric patients will experience delays of procedures or treatments because of the pandemic. Some have projected that rates of child abuse will increase as has been reported during natural disasters.3

Pediatricians around the country are coming together to tackle these issues in creative ways, including the rapid expansion of virtual/telehealth programs. The school systems are developing strategies to deliver online content, and even food, to their students’ homes. Hopefully these tactics will mitigate some of the potential effects on the mental and physical well-being of these patients.

How about my kids? Will they be all right? I am lucky that my husband and I will have jobs throughout this ordeal. Unfortunately, given my role as a hospitalist and my husband’s as a pulmonary/critical care physician, these same jobs that will keep our kids nourished and supported pose the greatest threat to them. As health care workers, we are worried about protecting our families, which may include vulnerable members. The Spanish health ministry announced that medical professionals account for approximately one in eight documented COVID-19 infections in Spain.4 With inadequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) in our own nation, we are concerned that our statistics could be similar.

There are multiple strategies to protect ourselves and our families during this difficult time. First, appropriate PPE is essential and integrity with the process must be maintained always. Hospital leaders can protect us by tirelessly working to acquire PPE. In Grand Rapids, Mich., our health system has partnered with multiple local manufacturing companies, including Steelcase, who are producing PPE for our workforce.5 Leaders can diligently update their system’s PPE recommendations to be in line with the latest CDC recommendations and disseminate the information regularly. Hospitalists should frequently check with their Infection Prevention department to make sure they understand if there have been any changes to the recommendations. Innovative solutions for sterilization of PPE, stethoscopes, badges and other equipment, such as with the use of UV boxes or hydrogen peroxide vapor,6 should be explored to minimize contamination. Hospitalists should bring a set of clothes and shoes to change into upon arrival to work and to change out of prior to leaving the hospital.

We must also keep our heads strong. Currently the anxiety amongst physicians is palpable but there is solidarity. Hospital leaders must ensure that hospitalists have easy access to free mental health resources, such as virtual counseling. Wellness teams must rise to the occasion with innovative tactics to support us. For example, Spectrum Health’s wellness team is sponsoring a blog where physicians can discuss COVID-19–related challenges openly. Hospitalist leaders should ensure that there is a structure for debriefing after critical incidents, which are sure to increase in frequency. Email lists and discussion boards sponsored by professional society also provide a collaborative venue for some of these discussions. We must take advantage of these resources and communicate with each other.

For me, in the end it comes back to the kids. My kids and most pediatric patients are not likely to be hospitalized from COVID-19, but they are also not immune to the toll that fighting this pandemic will take on our families. We took an oath to protect our patients, but what do we owe to our own children? At a minimum we can optimize how we protect ourselves every day, both physically and mentally. As we come together as a strong community to fight this pandemic, in addition to saving lives, we are working to ensure that, in the end, the kids will be all right.

Dr. Hadley is chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Spectrum Health/Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and clinical assistant professor at Michigan State University, East Lansing.

References

1. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648.

2. Hagan JF Jr; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Terrorism. Psychosocial implications of disaster or terrorism on children: A guide for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):787-795.

3. Gearhart S et al. The impact of natural disasters on domestic violence: An analysis of reports of simple assault in Florida (1997-2007). Violence Gend. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1089/vio.2017.0077.

4. Minder R, Peltier E. Virus knocks thousands of health workers out of action in Europe. The New York Times. March 24, 2020.

5. McVicar B. West Michigan businesses hustle to produce medical supplies amid coronavirus pandemic. MLive. March 25, 2020.

6. Kenney PA et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor sterilization of N95 respirators for reuse. medRxiv preprint. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20041087.

COVID-19 linked to multiple cardiovascular presentations

It’s becoming clear that COVID-19 infection can involve the cardiovascular system in many different ways, and this has “evolving” potential implications for treatment, say a team of cardiologists on the frontlines of the COVID-19 battle in New York City.

In an article published online April 3 in Circulation, Justin Fried, MD, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University, New York City, and colleagues present four case studies of COVID-19 patients with various cardiovascular presentations.

Case 1 is a 64-year-old woman whose predominant symptoms on admission were cardiac in nature, including chest pain and ST elevation, but without fever, cough, or other symptoms suggestive of COVID-19.

“In patients presenting with what appears to be a typical cardiac syndrome, COVID-19 infection should be in the differential during the current pandemic, even in the absence of fever or cough,” the clinicians advise.

Case 2 is a 38-year-old man with cardiogenic shock and acute respiratory distress with profound hypoxia who was rescued with veno-arterial-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV ECMO).

The initial presentation of this patient was more characteristic of severe COVID-19 disease, and cardiac involvement only became apparent after the initiation of ECMO, Fried and colleagues report.

Based on this case, they advise a “low threshold” to assess for cardiogenic shock in patients with acute systolic heart failure related to COVID-19. If inotropic support fails in these patients, intra-aortic balloon pump should be considered first for mechanical circulatory support because it requires the least maintenance from medical support staff.

In addition, in their experience, when a patient on VV ECMO develops superimposed cardiogenic shock, adding an arterial conduit at a relatively low blood flow rate may provide the necessary circulatory support without inducing left ventricular distension, they note.

“Our experience confirms that rescue of patients even with profound cardiogenic or mixed shock may be possible with temporary hemodynamic support at centers with availability of such devices,” Fried and colleagues report.

Case 3 is a 64-year-old woman with underlying cardiac disease who developed profound decompensation with COVID-19 infection.

This case demonstrates that the infection can cause decompensation of underlying heart failure and may lead to mixed shock, the clinicians say.

“Invasive hemodynamic monitoring, if feasible, may be helpful to manage the cardiac component of shock in such cases. Medications that prolong the QT interval are being considered for COVID-19 patients and may require closer monitoring in patients with underlying structural heart disease,” they note.

Case 4 is a 51-year-old man who underwent a heart transplant in 2007 and a kidney transplant in 2010. He had COVID-19 symptoms akin to those seen in nonimmunosuppressed patients with COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a “unique challenge” for solid organ transplant recipients, with only “limited” data on how to adjust immunosuppression during COVID-19 infection, Fried and colleagues say.

The pandemic also creates a challenge for the management of heart failure patients on the heart transplant wait list; the risks of delaying a transplant need to be balanced against the risks of donor infection and uncertainty regarding the impact of post-transplant immunosuppression protocols, they note.

As reported by Medscape Medical News, the American Heart Association has developed a COVID-19 patient registry to collect data on cardiovascular conditions and outcomes related to COVID-19 infection.

To participate in the registry, contact [email protected].

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s becoming clear that COVID-19 infection can involve the cardiovascular system in many different ways, and this has “evolving” potential implications for treatment, say a team of cardiologists on the frontlines of the COVID-19 battle in New York City.

In an article published online April 3 in Circulation, Justin Fried, MD, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University, New York City, and colleagues present four case studies of COVID-19 patients with various cardiovascular presentations.

Case 1 is a 64-year-old woman whose predominant symptoms on admission were cardiac in nature, including chest pain and ST elevation, but without fever, cough, or other symptoms suggestive of COVID-19.

“In patients presenting with what appears to be a typical cardiac syndrome, COVID-19 infection should be in the differential during the current pandemic, even in the absence of fever or cough,” the clinicians advise.

Case 2 is a 38-year-old man with cardiogenic shock and acute respiratory distress with profound hypoxia who was rescued with veno-arterial-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV ECMO).

The initial presentation of this patient was more characteristic of severe COVID-19 disease, and cardiac involvement only became apparent after the initiation of ECMO, Fried and colleagues report.

Based on this case, they advise a “low threshold” to assess for cardiogenic shock in patients with acute systolic heart failure related to COVID-19. If inotropic support fails in these patients, intra-aortic balloon pump should be considered first for mechanical circulatory support because it requires the least maintenance from medical support staff.

In addition, in their experience, when a patient on VV ECMO develops superimposed cardiogenic shock, adding an arterial conduit at a relatively low blood flow rate may provide the necessary circulatory support without inducing left ventricular distension, they note.

“Our experience confirms that rescue of patients even with profound cardiogenic or mixed shock may be possible with temporary hemodynamic support at centers with availability of such devices,” Fried and colleagues report.

Case 3 is a 64-year-old woman with underlying cardiac disease who developed profound decompensation with COVID-19 infection.

This case demonstrates that the infection can cause decompensation of underlying heart failure and may lead to mixed shock, the clinicians say.

“Invasive hemodynamic monitoring, if feasible, may be helpful to manage the cardiac component of shock in such cases. Medications that prolong the QT interval are being considered for COVID-19 patients and may require closer monitoring in patients with underlying structural heart disease,” they note.

Case 4 is a 51-year-old man who underwent a heart transplant in 2007 and a kidney transplant in 2010. He had COVID-19 symptoms akin to those seen in nonimmunosuppressed patients with COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a “unique challenge” for solid organ transplant recipients, with only “limited” data on how to adjust immunosuppression during COVID-19 infection, Fried and colleagues say.

The pandemic also creates a challenge for the management of heart failure patients on the heart transplant wait list; the risks of delaying a transplant need to be balanced against the risks of donor infection and uncertainty regarding the impact of post-transplant immunosuppression protocols, they note.

As reported by Medscape Medical News, the American Heart Association has developed a COVID-19 patient registry to collect data on cardiovascular conditions and outcomes related to COVID-19 infection.

To participate in the registry, contact [email protected].

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s becoming clear that COVID-19 infection can involve the cardiovascular system in many different ways, and this has “evolving” potential implications for treatment, say a team of cardiologists on the frontlines of the COVID-19 battle in New York City.

In an article published online April 3 in Circulation, Justin Fried, MD, Division of Cardiology, Columbia University, New York City, and colleagues present four case studies of COVID-19 patients with various cardiovascular presentations.

Case 1 is a 64-year-old woman whose predominant symptoms on admission were cardiac in nature, including chest pain and ST elevation, but without fever, cough, or other symptoms suggestive of COVID-19.

“In patients presenting with what appears to be a typical cardiac syndrome, COVID-19 infection should be in the differential during the current pandemic, even in the absence of fever or cough,” the clinicians advise.

Case 2 is a 38-year-old man with cardiogenic shock and acute respiratory distress with profound hypoxia who was rescued with veno-arterial-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV ECMO).

The initial presentation of this patient was more characteristic of severe COVID-19 disease, and cardiac involvement only became apparent after the initiation of ECMO, Fried and colleagues report.

Based on this case, they advise a “low threshold” to assess for cardiogenic shock in patients with acute systolic heart failure related to COVID-19. If inotropic support fails in these patients, intra-aortic balloon pump should be considered first for mechanical circulatory support because it requires the least maintenance from medical support staff.

In addition, in their experience, when a patient on VV ECMO develops superimposed cardiogenic shock, adding an arterial conduit at a relatively low blood flow rate may provide the necessary circulatory support without inducing left ventricular distension, they note.

“Our experience confirms that rescue of patients even with profound cardiogenic or mixed shock may be possible with temporary hemodynamic support at centers with availability of such devices,” Fried and colleagues report.

Case 3 is a 64-year-old woman with underlying cardiac disease who developed profound decompensation with COVID-19 infection.

This case demonstrates that the infection can cause decompensation of underlying heart failure and may lead to mixed shock, the clinicians say.

“Invasive hemodynamic monitoring, if feasible, may be helpful to manage the cardiac component of shock in such cases. Medications that prolong the QT interval are being considered for COVID-19 patients and may require closer monitoring in patients with underlying structural heart disease,” they note.

Case 4 is a 51-year-old man who underwent a heart transplant in 2007 and a kidney transplant in 2010. He had COVID-19 symptoms akin to those seen in nonimmunosuppressed patients with COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a “unique challenge” for solid organ transplant recipients, with only “limited” data on how to adjust immunosuppression during COVID-19 infection, Fried and colleagues say.

The pandemic also creates a challenge for the management of heart failure patients on the heart transplant wait list; the risks of delaying a transplant need to be balanced against the risks of donor infection and uncertainty regarding the impact of post-transplant immunosuppression protocols, they note.

As reported by Medscape Medical News, the American Heart Association has developed a COVID-19 patient registry to collect data on cardiovascular conditions and outcomes related to COVID-19 infection.

To participate in the registry, contact [email protected].

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AMA president calls for greater reliance on science in COVID-19 fight

The president of the American Medical Association is calling on politicians and the media to rely on science and evidence to help the public through the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We live in a time when misinformation, falsehoods, and outright lies spread like viruses online, through social media and even, at times, in the media at large,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, said during an April 7 address. “We have witnessed a concerning shift over the last several decades where policy decisions seem to be driven by ideology and politics instead of facts and evidence. The result is a growing mistrust in American institutions, in science, and in the counsel of leading experts whose lives are dedicated to the pursuit of evidence and reason.”

To that end, she called on everyone – from politicians to the general public – to trust the scientific evidence.

Dr. Harris noted that the scientific data on COVID-19 have already yielded important lessons about who is more likely to be affected and how easily the virus can spread. The data also point to the effectiveness of stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders. “This is our best chance to slow the spread of the virus,” she said, adding that the enhanced emphasis on hand washing and other hygiene practices “may seem ‘simplistic,’ but they are, in fact, based in science and evidence.”

And, as the pandemic continues, Dr. Harris said that now is the time to rely on science. She said the AMA “calls on all elected officials to affirm science, evidence, and fact in their words and actions,” and she urged that the government’s scientific institutions be led by experts who are “protected from political influence.”

It is incumbent upon everyone to actively work to contain and stop the spread of misinformation related to COVID-19, she said. “We must ensure the war is against the virus and not against science,” Dr. Harris said.

The president of the American Medical Association is calling on politicians and the media to rely on science and evidence to help the public through the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We live in a time when misinformation, falsehoods, and outright lies spread like viruses online, through social media and even, at times, in the media at large,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, said during an April 7 address. “We have witnessed a concerning shift over the last several decades where policy decisions seem to be driven by ideology and politics instead of facts and evidence. The result is a growing mistrust in American institutions, in science, and in the counsel of leading experts whose lives are dedicated to the pursuit of evidence and reason.”

To that end, she called on everyone – from politicians to the general public – to trust the scientific evidence.

Dr. Harris noted that the scientific data on COVID-19 have already yielded important lessons about who is more likely to be affected and how easily the virus can spread. The data also point to the effectiveness of stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders. “This is our best chance to slow the spread of the virus,” she said, adding that the enhanced emphasis on hand washing and other hygiene practices “may seem ‘simplistic,’ but they are, in fact, based in science and evidence.”

And, as the pandemic continues, Dr. Harris said that now is the time to rely on science. She said the AMA “calls on all elected officials to affirm science, evidence, and fact in their words and actions,” and she urged that the government’s scientific institutions be led by experts who are “protected from political influence.”

It is incumbent upon everyone to actively work to contain and stop the spread of misinformation related to COVID-19, she said. “We must ensure the war is against the virus and not against science,” Dr. Harris said.

The president of the American Medical Association is calling on politicians and the media to rely on science and evidence to help the public through the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We live in a time when misinformation, falsehoods, and outright lies spread like viruses online, through social media and even, at times, in the media at large,” Patrice A. Harris, MD, said during an April 7 address. “We have witnessed a concerning shift over the last several decades where policy decisions seem to be driven by ideology and politics instead of facts and evidence. The result is a growing mistrust in American institutions, in science, and in the counsel of leading experts whose lives are dedicated to the pursuit of evidence and reason.”

To that end, she called on everyone – from politicians to the general public – to trust the scientific evidence.

Dr. Harris noted that the scientific data on COVID-19 have already yielded important lessons about who is more likely to be affected and how easily the virus can spread. The data also point to the effectiveness of stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders. “This is our best chance to slow the spread of the virus,” she said, adding that the enhanced emphasis on hand washing and other hygiene practices “may seem ‘simplistic,’ but they are, in fact, based in science and evidence.”

And, as the pandemic continues, Dr. Harris said that now is the time to rely on science. She said the AMA “calls on all elected officials to affirm science, evidence, and fact in their words and actions,” and she urged that the government’s scientific institutions be led by experts who are “protected from political influence.”

It is incumbent upon everyone to actively work to contain and stop the spread of misinformation related to COVID-19, she said. “We must ensure the war is against the virus and not against science,” Dr. Harris said.

NCCN panel: Defer nonurgent skin cancer care during pandemic

Amid the except when metastatic nodes are threatening vital structures or neoadjuvant therapy is not possible or has already failed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said in a new document about managing melanoma during the pandemic.

“The NCCN Melanoma Panel does not consider neoadjuvant therapy as a superior option to surgery followed by systemic adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma, but available data suggest this is a reasonable resource-conserving option during the COVID-19 outbreak,” according to the panel. Surgery should be performed 8-9 weeks after initiation, said the group, an alliance of physicians from 30 U.S. cancer centers.

Echoing pandemic advice from other medical fields, the group’s melanoma recommendations focused on deferring nonurgent care until after the pandemic passes, and in the meantime limiting patient contact with the medical system and preserving hospital resources by, for instance, using telemedicine and opting for treatment regimens that require fewer trips to the clinic.

In a separate document on nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the group said that, with the exception of Merkel cell carcinoma, excisions for NMSC – including basal and squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and rare tumors – should also generally be postponed during the pandemic.

The exception is if there is a risk of metastases within 3 months, but “such estimations of risks ... should be weighed against risks of the patient contracting COVID-19 infection or asymptomatically transmitting COVID-19 to health care workers,” the panel said.

Along the same lines, adjuvant therapy after surgical clearance of localized NMSC “should generally not be undertaken given the multiple visits required,” except for more extensive disease.

For primary cutaneous melanoma , “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay, even for thicker [cutaneous melanoma],” the group said, so it recommended delaying wide excisions for melanoma in situ, lesions no thicker than 1 mm (T1) so long as the biopsy removed most of the lesion, and invasive melanomas of any depth if the biopsy had clear margins or only peripheral transection of the in situ component. They said sentinel lymph node biopsy can also be delayed for up to 3 months.

Resections for metastatic stage III-IV disease should also be put on hold unless the patient is symptomatic; systemic treatments should instead be continued. However, “given hospital-intensive resources, the use of talimogene laherparepvec for cutaneous/nodal/in-transit metastasis should be cautiously considered and, if possible, deferred until the COVID-19 crisis abates. A single dose of palliative radiation therapy may be useful for larger/symptomatic metastasis, as appropriate,” the group said.

If resection is still a go, the group noted that adjuvant therapy “has not been shown to improve melanoma-specific survival and should be deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with [a less than] 50% chance of disease relapse.” Dabrafenib/trametinib is the evidence-based choice if adjuvant treatment is opted for, but “alternative BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens (encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib) may be substituted if drug supply is limited” by the pandemic, the group said.

For stage IV melanoma, “single-agent anti-PD-1 [programmed cell death 1] is recommended over combination ipilimumab/nivolumab at present” because there’s less inflammation and possible exacerbation of COVID-19, less need for steroids to counter adverse events, and less need for follow up to check for toxicities.

The group said evidence supports that 400 mg pembrolizumab administered intravenously every 6 weeks would likely be as effective as 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks and would help keep people out of the hospital.

However, for stage IV melanoma with brain metastasis, there’s a strong rate of response to ipilimumab/nivolumab, so it may still be an option. In that case, “a regimen of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four infusions, with subsequent consideration for nivolumab monotherapy, is associated with lower rates of immune-mediated toxicity,” compared with standard dosing.

Regarding potential drug shortages, the group noted that encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations can be substituted for dabrafenib/trametinib for adjuvant therapy, and single-agent BRAF inhibitors can be used in the event of MEK inhibitor shortages.

In hospice, the group said oral temozolomide is the preferred option for palliative chemotherapy since it would limit resource utilization and contact with the medical system.

Amid the except when metastatic nodes are threatening vital structures or neoadjuvant therapy is not possible or has already failed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said in a new document about managing melanoma during the pandemic.

“The NCCN Melanoma Panel does not consider neoadjuvant therapy as a superior option to surgery followed by systemic adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma, but available data suggest this is a reasonable resource-conserving option during the COVID-19 outbreak,” according to the panel. Surgery should be performed 8-9 weeks after initiation, said the group, an alliance of physicians from 30 U.S. cancer centers.

Echoing pandemic advice from other medical fields, the group’s melanoma recommendations focused on deferring nonurgent care until after the pandemic passes, and in the meantime limiting patient contact with the medical system and preserving hospital resources by, for instance, using telemedicine and opting for treatment regimens that require fewer trips to the clinic.

In a separate document on nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the group said that, with the exception of Merkel cell carcinoma, excisions for NMSC – including basal and squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and rare tumors – should also generally be postponed during the pandemic.

The exception is if there is a risk of metastases within 3 months, but “such estimations of risks ... should be weighed against risks of the patient contracting COVID-19 infection or asymptomatically transmitting COVID-19 to health care workers,” the panel said.

Along the same lines, adjuvant therapy after surgical clearance of localized NMSC “should generally not be undertaken given the multiple visits required,” except for more extensive disease.

For primary cutaneous melanoma , “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay, even for thicker [cutaneous melanoma],” the group said, so it recommended delaying wide excisions for melanoma in situ, lesions no thicker than 1 mm (T1) so long as the biopsy removed most of the lesion, and invasive melanomas of any depth if the biopsy had clear margins or only peripheral transection of the in situ component. They said sentinel lymph node biopsy can also be delayed for up to 3 months.

Resections for metastatic stage III-IV disease should also be put on hold unless the patient is symptomatic; systemic treatments should instead be continued. However, “given hospital-intensive resources, the use of talimogene laherparepvec for cutaneous/nodal/in-transit metastasis should be cautiously considered and, if possible, deferred until the COVID-19 crisis abates. A single dose of palliative radiation therapy may be useful for larger/symptomatic metastasis, as appropriate,” the group said.

If resection is still a go, the group noted that adjuvant therapy “has not been shown to improve melanoma-specific survival and should be deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with [a less than] 50% chance of disease relapse.” Dabrafenib/trametinib is the evidence-based choice if adjuvant treatment is opted for, but “alternative BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens (encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib) may be substituted if drug supply is limited” by the pandemic, the group said.

For stage IV melanoma, “single-agent anti-PD-1 [programmed cell death 1] is recommended over combination ipilimumab/nivolumab at present” because there’s less inflammation and possible exacerbation of COVID-19, less need for steroids to counter adverse events, and less need for follow up to check for toxicities.

The group said evidence supports that 400 mg pembrolizumab administered intravenously every 6 weeks would likely be as effective as 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks and would help keep people out of the hospital.

However, for stage IV melanoma with brain metastasis, there’s a strong rate of response to ipilimumab/nivolumab, so it may still be an option. In that case, “a regimen of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four infusions, with subsequent consideration for nivolumab monotherapy, is associated with lower rates of immune-mediated toxicity,” compared with standard dosing.

Regarding potential drug shortages, the group noted that encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations can be substituted for dabrafenib/trametinib for adjuvant therapy, and single-agent BRAF inhibitors can be used in the event of MEK inhibitor shortages.

In hospice, the group said oral temozolomide is the preferred option for palliative chemotherapy since it would limit resource utilization and contact with the medical system.

Amid the except when metastatic nodes are threatening vital structures or neoadjuvant therapy is not possible or has already failed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said in a new document about managing melanoma during the pandemic.

“The NCCN Melanoma Panel does not consider neoadjuvant therapy as a superior option to surgery followed by systemic adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma, but available data suggest this is a reasonable resource-conserving option during the COVID-19 outbreak,” according to the panel. Surgery should be performed 8-9 weeks after initiation, said the group, an alliance of physicians from 30 U.S. cancer centers.

Echoing pandemic advice from other medical fields, the group’s melanoma recommendations focused on deferring nonurgent care until after the pandemic passes, and in the meantime limiting patient contact with the medical system and preserving hospital resources by, for instance, using telemedicine and opting for treatment regimens that require fewer trips to the clinic.

In a separate document on nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the group said that, with the exception of Merkel cell carcinoma, excisions for NMSC – including basal and squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and rare tumors – should also generally be postponed during the pandemic.

The exception is if there is a risk of metastases within 3 months, but “such estimations of risks ... should be weighed against risks of the patient contracting COVID-19 infection or asymptomatically transmitting COVID-19 to health care workers,” the panel said.

Along the same lines, adjuvant therapy after surgical clearance of localized NMSC “should generally not be undertaken given the multiple visits required,” except for more extensive disease.

For primary cutaneous melanoma , “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay, even for thicker [cutaneous melanoma],” the group said, so it recommended delaying wide excisions for melanoma in situ, lesions no thicker than 1 mm (T1) so long as the biopsy removed most of the lesion, and invasive melanomas of any depth if the biopsy had clear margins or only peripheral transection of the in situ component. They said sentinel lymph node biopsy can also be delayed for up to 3 months.

Resections for metastatic stage III-IV disease should also be put on hold unless the patient is symptomatic; systemic treatments should instead be continued. However, “given hospital-intensive resources, the use of talimogene laherparepvec for cutaneous/nodal/in-transit metastasis should be cautiously considered and, if possible, deferred until the COVID-19 crisis abates. A single dose of palliative radiation therapy may be useful for larger/symptomatic metastasis, as appropriate,” the group said.

If resection is still a go, the group noted that adjuvant therapy “has not been shown to improve melanoma-specific survival and should be deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with [a less than] 50% chance of disease relapse.” Dabrafenib/trametinib is the evidence-based choice if adjuvant treatment is opted for, but “alternative BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens (encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib) may be substituted if drug supply is limited” by the pandemic, the group said.

For stage IV melanoma, “single-agent anti-PD-1 [programmed cell death 1] is recommended over combination ipilimumab/nivolumab at present” because there’s less inflammation and possible exacerbation of COVID-19, less need for steroids to counter adverse events, and less need for follow up to check for toxicities.

The group said evidence supports that 400 mg pembrolizumab administered intravenously every 6 weeks would likely be as effective as 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks and would help keep people out of the hospital.

However, for stage IV melanoma with brain metastasis, there’s a strong rate of response to ipilimumab/nivolumab, so it may still be an option. In that case, “a regimen of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four infusions, with subsequent consideration for nivolumab monotherapy, is associated with lower rates of immune-mediated toxicity,” compared with standard dosing.

Regarding potential drug shortages, the group noted that encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations can be substituted for dabrafenib/trametinib for adjuvant therapy, and single-agent BRAF inhibitors can be used in the event of MEK inhibitor shortages.

In hospice, the group said oral temozolomide is the preferred option for palliative chemotherapy since it would limit resource utilization and contact with the medical system.

JAK inhibitors may increase risk of herpes zoster

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease or other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors appear generally safe, though they may increase the risk of herpes zoster infection, according to a large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data from more than 66,000 patients revealed no significant links between JAK inhibitors and risks of serious infections, malignancy, or major adverse cardiovascular events, reported lead author Pablo Olivera, MD, of Centro de Educación Médica e Investigación Clínica (CEMIC) in Buenos Aires and colleagues.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review evaluating the risk profile of JAK inhibitors in a wide spectrum of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

The investigators drew studies from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, and EMBASE from 1990 to 2019 and from conference databases from 2012 to 2018. Out of 973 studies identified, 82 were included in the final analysis, of which two-thirds were randomized clinical trials. In total, 101,925 subjects were included, of whom a majority had rheumatoid arthritis (n = 86,308), followed by psoriasis (n = 9,311), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 5,987), and ankylosing spondylitis (n = 319).

Meta-analysis of JAK inhibitor usage involved 66,159 patients. Four JAK inhibitors were included: tofacitinib, filgotinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. The primary outcomes were the incidence rates of adverse events and serious adverse events. The investigators also estimated incidence rates of herpes zoster infection, serious infections, mortality, malignancy, and major adverse cardiovascular events. These rates were compared with those of patients who received placebo or an active comparator in clinical trials.

Analysis showed that almost 9 out of 10 patients (87.16%) who were exposed to a JAK inhibitor received tofacitinib. The investigators described high variability in treatment duration and baseline characteristics of participants. Rates of adverse events and serious adverse events also fell across a broad spectrum, from 10% to 82% and from 0% to 29%, respectively.

“Most [adverse events] were mild, and included worsening of the underlying condition, probably showing lack of efficacy,” the investigators wrote.

Rates of mortality and most adverse events were not significantly associated with JAK inhibitor exposure. In contrast, relative risk of herpes zoster infection was 57% higher in patients who received a JAK inhibitor than in those who received a placebo or comparator (RR, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.37).

“Regarding the risk of herpes zoster with JAK inhibitors, the largest evidence comes from the use of tofacitinib, but it appears to be a class effect, with a clear dose-dependent effect,” the investigators wrote.

Although risks of herpes zoster may be carried across the drug class, they may not be evenly distributed given that a subgroup analysis revealed that some JAK inhibitors may bring higher risks than others; specifically, tofacitinib and baricitinib were associated with higher relative risks of herpes zoster than were upadacitinib and filgotinib.

“Although this is merely a qualitative comparison, this difference could be related to the fact that both filgotinib and upadacitinib are selective JAK1 inhibitors, whereas tofacitinib is a JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor and baricitinib a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor,” the investigators wrote. “Further studies are needed to determine if JAK isoform selectivity affects the risk of herpes zoster.”

The investigators emphasized this need for more research. While the present findings help illuminate the safety profile of JAK inhibitors, they are clouded by various other factors, such as disease-specific considerations, a lack of real-world data, and studies that are likely too short to accurately determine risk of malignancy, the investigators wrote.

“More studies with long follow-up and in the real world setting, in different conditions, will be needed to fully elucidate the safety profile of the different JAK inhibitors,” the investigators concluded.

The investigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Olivera P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.001.

The multiple different cytokines contributing to intestinal inflammation in IBD patients have been a major challenge in the design of therapies. Because the JAK signaling pathway (comprised of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2) is required for responses to a broad range of cytokines, therapies that inhibit JAK signaling have been an active area of interest. A simultaneous and important concern, however, has been the potential for adverse consequences when inhibiting the breadth of immune and hematopoietic molecules that depend on JAK family members for their functions. This meta-analysis by Olivera et al. examined adverse outcomes of four different JAK inhibitors in clinical trials across four immune-mediated diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis), finding that herpes zoster infection was significantly increased (relative risk, 1.57). In contrast, patients treated with JAK inhibitors were not at a significantly increased risk for various other adverse events.

Reduced dosing of JAK inhibitors has been implemented as a means of improving safety profiles in select immune-mediated diseases. Another approach is more selective JAK inhibition, although it is unclear whether this will eliminate the risk of herpes zoster infection. In the current meta-analysis, about 87% of the studies had evaluated tofacitinib treatment, which inhibits both JAK1 and JAK3; more selective JAK inhibitors could not be evaluated in an equivalent manner. Of note, JAK1 is required for signaling by various cytokines that participate in the response to viruses, including type I IFNs and gamma c family members (such as IL-2 and IL-15); therefore, even the more selective JAK1 inhibitors do not leave this immune function fully intact. However, simply reducing the number of JAK family members inhibited simultaneously may be sufficient to reduce risk.

JAK inhibitors warrant further evaluation as additional infectious challenges arise, particularly with respect to viruses. In addition, more selective targeting of JAK inhibition of intestinal tissues may ultimately reduce systemic effects, including the risk of herpes zoster.

Clara Abraham, MD, professor of medicine, section of digestive diseases, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The multiple different cytokines contributing to intestinal inflammation in IBD patients have been a major challenge in the design of therapies. Because the JAK signaling pathway (comprised of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2) is required for responses to a broad range of cytokines, therapies that inhibit JAK signaling have been an active area of interest. A simultaneous and important concern, however, has been the potential for adverse consequences when inhibiting the breadth of immune and hematopoietic molecules that depend on JAK family members for their functions. This meta-analysis by Olivera et al. examined adverse outcomes of four different JAK inhibitors in clinical trials across four immune-mediated diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis), finding that herpes zoster infection was significantly increased (relative risk, 1.57). In contrast, patients treated with JAK inhibitors were not at a significantly increased risk for various other adverse events.

Reduced dosing of JAK inhibitors has been implemented as a means of improving safety profiles in select immune-mediated diseases. Another approach is more selective JAK inhibition, although it is unclear whether this will eliminate the risk of herpes zoster infection. In the current meta-analysis, about 87% of the studies had evaluated tofacitinib treatment, which inhibits both JAK1 and JAK3; more selective JAK inhibitors could not be evaluated in an equivalent manner. Of note, JAK1 is required for signaling by various cytokines that participate in the response to viruses, including type I IFNs and gamma c family members (such as IL-2 and IL-15); therefore, even the more selective JAK1 inhibitors do not leave this immune function fully intact. However, simply reducing the number of JAK family members inhibited simultaneously may be sufficient to reduce risk.

JAK inhibitors warrant further evaluation as additional infectious challenges arise, particularly with respect to viruses. In addition, more selective targeting of JAK inhibition of intestinal tissues may ultimately reduce systemic effects, including the risk of herpes zoster.

Clara Abraham, MD, professor of medicine, section of digestive diseases, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The multiple different cytokines contributing to intestinal inflammation in IBD patients have been a major challenge in the design of therapies. Because the JAK signaling pathway (comprised of JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2) is required for responses to a broad range of cytokines, therapies that inhibit JAK signaling have been an active area of interest. A simultaneous and important concern, however, has been the potential for adverse consequences when inhibiting the breadth of immune and hematopoietic molecules that depend on JAK family members for their functions. This meta-analysis by Olivera et al. examined adverse outcomes of four different JAK inhibitors in clinical trials across four immune-mediated diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, IBD, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis), finding that herpes zoster infection was significantly increased (relative risk, 1.57). In contrast, patients treated with JAK inhibitors were not at a significantly increased risk for various other adverse events.

Reduced dosing of JAK inhibitors has been implemented as a means of improving safety profiles in select immune-mediated diseases. Another approach is more selective JAK inhibition, although it is unclear whether this will eliminate the risk of herpes zoster infection. In the current meta-analysis, about 87% of the studies had evaluated tofacitinib treatment, which inhibits both JAK1 and JAK3; more selective JAK inhibitors could not be evaluated in an equivalent manner. Of note, JAK1 is required for signaling by various cytokines that participate in the response to viruses, including type I IFNs and gamma c family members (such as IL-2 and IL-15); therefore, even the more selective JAK1 inhibitors do not leave this immune function fully intact. However, simply reducing the number of JAK family members inhibited simultaneously may be sufficient to reduce risk.

JAK inhibitors warrant further evaluation as additional infectious challenges arise, particularly with respect to viruses. In addition, more selective targeting of JAK inhibition of intestinal tissues may ultimately reduce systemic effects, including the risk of herpes zoster.

Clara Abraham, MD, professor of medicine, section of digestive diseases, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease or other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors appear generally safe, though they may increase the risk of herpes zoster infection, according to a large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data from more than 66,000 patients revealed no significant links between JAK inhibitors and risks of serious infections, malignancy, or major adverse cardiovascular events, reported lead author Pablo Olivera, MD, of Centro de Educación Médica e Investigación Clínica (CEMIC) in Buenos Aires and colleagues.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review evaluating the risk profile of JAK inhibitors in a wide spectrum of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

The investigators drew studies from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, and EMBASE from 1990 to 2019 and from conference databases from 2012 to 2018. Out of 973 studies identified, 82 were included in the final analysis, of which two-thirds were randomized clinical trials. In total, 101,925 subjects were included, of whom a majority had rheumatoid arthritis (n = 86,308), followed by psoriasis (n = 9,311), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 5,987), and ankylosing spondylitis (n = 319).

Meta-analysis of JAK inhibitor usage involved 66,159 patients. Four JAK inhibitors were included: tofacitinib, filgotinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. The primary outcomes were the incidence rates of adverse events and serious adverse events. The investigators also estimated incidence rates of herpes zoster infection, serious infections, mortality, malignancy, and major adverse cardiovascular events. These rates were compared with those of patients who received placebo or an active comparator in clinical trials.

Analysis showed that almost 9 out of 10 patients (87.16%) who were exposed to a JAK inhibitor received tofacitinib. The investigators described high variability in treatment duration and baseline characteristics of participants. Rates of adverse events and serious adverse events also fell across a broad spectrum, from 10% to 82% and from 0% to 29%, respectively.

“Most [adverse events] were mild, and included worsening of the underlying condition, probably showing lack of efficacy,” the investigators wrote.

Rates of mortality and most adverse events were not significantly associated with JAK inhibitor exposure. In contrast, relative risk of herpes zoster infection was 57% higher in patients who received a JAK inhibitor than in those who received a placebo or comparator (RR, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.37).

“Regarding the risk of herpes zoster with JAK inhibitors, the largest evidence comes from the use of tofacitinib, but it appears to be a class effect, with a clear dose-dependent effect,” the investigators wrote.

Although risks of herpes zoster may be carried across the drug class, they may not be evenly distributed given that a subgroup analysis revealed that some JAK inhibitors may bring higher risks than others; specifically, tofacitinib and baricitinib were associated with higher relative risks of herpes zoster than were upadacitinib and filgotinib.

“Although this is merely a qualitative comparison, this difference could be related to the fact that both filgotinib and upadacitinib are selective JAK1 inhibitors, whereas tofacitinib is a JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor and baricitinib a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor,” the investigators wrote. “Further studies are needed to determine if JAK isoform selectivity affects the risk of herpes zoster.”

The investigators emphasized this need for more research. While the present findings help illuminate the safety profile of JAK inhibitors, they are clouded by various other factors, such as disease-specific considerations, a lack of real-world data, and studies that are likely too short to accurately determine risk of malignancy, the investigators wrote.

“More studies with long follow-up and in the real world setting, in different conditions, will be needed to fully elucidate the safety profile of the different JAK inhibitors,” the investigators concluded.

The investigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Olivera P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.001.

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease or other immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors appear generally safe, though they may increase the risk of herpes zoster infection, according to a large-scale systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data from more than 66,000 patients revealed no significant links between JAK inhibitors and risks of serious infections, malignancy, or major adverse cardiovascular events, reported lead author Pablo Olivera, MD, of Centro de Educación Médica e Investigación Clínica (CEMIC) in Buenos Aires and colleagues.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review evaluating the risk profile of JAK inhibitors in a wide spectrum of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases,” they wrote in Gastroenterology.

The investigators drew studies from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, and EMBASE from 1990 to 2019 and from conference databases from 2012 to 2018. Out of 973 studies identified, 82 were included in the final analysis, of which two-thirds were randomized clinical trials. In total, 101,925 subjects were included, of whom a majority had rheumatoid arthritis (n = 86,308), followed by psoriasis (n = 9,311), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 5,987), and ankylosing spondylitis (n = 319).

Meta-analysis of JAK inhibitor usage involved 66,159 patients. Four JAK inhibitors were included: tofacitinib, filgotinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib. The primary outcomes were the incidence rates of adverse events and serious adverse events. The investigators also estimated incidence rates of herpes zoster infection, serious infections, mortality, malignancy, and major adverse cardiovascular events. These rates were compared with those of patients who received placebo or an active comparator in clinical trials.

Analysis showed that almost 9 out of 10 patients (87.16%) who were exposed to a JAK inhibitor received tofacitinib. The investigators described high variability in treatment duration and baseline characteristics of participants. Rates of adverse events and serious adverse events also fell across a broad spectrum, from 10% to 82% and from 0% to 29%, respectively.

“Most [adverse events] were mild, and included worsening of the underlying condition, probably showing lack of efficacy,” the investigators wrote.

Rates of mortality and most adverse events were not significantly associated with JAK inhibitor exposure. In contrast, relative risk of herpes zoster infection was 57% higher in patients who received a JAK inhibitor than in those who received a placebo or comparator (RR, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.37).

“Regarding the risk of herpes zoster with JAK inhibitors, the largest evidence comes from the use of tofacitinib, but it appears to be a class effect, with a clear dose-dependent effect,” the investigators wrote.

Although risks of herpes zoster may be carried across the drug class, they may not be evenly distributed given that a subgroup analysis revealed that some JAK inhibitors may bring higher risks than others; specifically, tofacitinib and baricitinib were associated with higher relative risks of herpes zoster than were upadacitinib and filgotinib.

“Although this is merely a qualitative comparison, this difference could be related to the fact that both filgotinib and upadacitinib are selective JAK1 inhibitors, whereas tofacitinib is a JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor and baricitinib a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor,” the investigators wrote. “Further studies are needed to determine if JAK isoform selectivity affects the risk of herpes zoster.”

The investigators emphasized this need for more research. While the present findings help illuminate the safety profile of JAK inhibitors, they are clouded by various other factors, such as disease-specific considerations, a lack of real-world data, and studies that are likely too short to accurately determine risk of malignancy, the investigators wrote.

“More studies with long follow-up and in the real world setting, in different conditions, will be needed to fully elucidate the safety profile of the different JAK inhibitors,” the investigators concluded.

The investigators disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Takeda, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Olivera P et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.001.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY