User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

New onset-depression after RA diagnosis raises mortality risk ‘more than sixfold’

The development of depression after a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis increased the risk for death “more than sixfold” when compared with having no depression at diagnosis, according to Danish researchers.

Cumulative mortality at 10 years was approximately 37% in patients with comorbid RA and depression versus around 13.5% of RA patients with no depression, Jens Kristian Pedersen, MD, PhD, of Odense (Denmark) University Hospital–Svendborg Hospital and the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, reported at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

“According to [antidepressant] exposure status, the cumulative mortality followed two clearly different paths,” Dr. Pedersen said. “The mortality curves separated early and already within the first and second year of follow-up.”

RA, depression, and mortality

Rates of depression in patients with RA are high, Dr. Pedersen said, and while it’s previously been reported that their coexistence can increase mortality, this is the first time that the link has been investigated in a population newly diagnosed with RA.

In this study, Dr. Pedersen and collaborators wanted to look at the association in incident RA and defined depression as the first filling of an antidepressant prescription.

“Although antidepressants are used for different indications, we have recently described that in RA the most frequent indication for filling antidepressants is depression,” he explained. Moreover, that research found that “the frequency of filling coincides with the occurrence of depressive disorder previously reported in the scientific literature.”

Data sourced from multiple Danish registers

To examine the mortality risk associated with newly diagnosed RA and new-onset depression, Dr. Pedersen described how five different Danish registers were used.

First, data from the DANBIO register were used to identify patients with incident RA living in Denmark over a 10-year period ending in December 2018. Although perhaps widely known as a biologics register, DANBIO is required by the Danish National Board of Health to collect information on all patients with RA, regardless of their treatment.

Next, the Danish National Prescription Register and Danish National Patient Register were consulted to obtain data on patients who had a first prescription for antidepressant treatment and information on those who developed a diagnosis of depression. Demographic, vital status, and socioeconomic data were collated from the Danish Civil Registration System and Statistics Denmark databases.

To be sure they were looking at incident cases of RA and new cases of depression, the researchers excluded anyone with an existing prescription of antidepressants or methotrexate, or who had a confirmed diagnosis of either disorder 3 years prior to the index date of Jan. 1, 2008.

This meant that, from a total population of 18,000 patients in the DANBIO database, there were just over 11,000 who could be included in the analyses.

Overall, the median age at RA diagnosis was 61 years, two-thirds were female, and two-thirds had seropositive disease.

New-onset depression in incident RA

“During follow-up, about 10% filled a prescription of antidepressants,” said Dr. Pedersen, adding that there were 671 deaths, representing around 57,000 person-years at risk.

“The majority died from natural causes,” he said, although the cause of death was unknown in 30% of cases.

Comparing those who did and did not have a prescription for antidepressants, there were some differences in the age at which death occurred, the percentage of females to males, the presence of other comorbidities, and levels of higher education and income. These were all adjusted for in the analyses.

Adjusted hazard rate ratios were calculated to look at the mortality risk in patients who had antidepressant exposure. The highest HRR for mortality with antidepressant use was seen in patients aged 55 years or younger at 6.66, with the next highest HRRs being for male gender (3.70) and seropositive RA (3.45).

But HRRs for seronegative RA, female gender, and age 55-70 years or older than 75 years were all still around 3.0.

Depression definition questioned

“My only concern is about the definition of depression in your analysis,” said a member of the audience at the congress.

“You used antidepressant use as a proxy of depression diagnosis, but it might be that most or many patients have taken [medication] like duloxetine for pain control, and you are just seeing higher disease activity and more aggressive RA.”

Dr. Pedersen responded: “After the EULAR 2022 submission deadline, we reanalyzed our data using two other measures of depression.

“First, we use treatment with antidepressants with a positive indication of depression, according to the prescribing physician, and secondly, we used first diagnosis with depression according to ICD-10 Code F32 – ‘depressive episode after discharge from hospital as an outpatient,’ ” he said.

“All definitions end up with a hazard rate ratio of about three. So, in my opinion, it doesn’t matter whether you focus on one measure of depression or the other.”

David Isenberg, MD, FRCP, professor of rheumatology at University College London, wanted to know more about the antecedent history of depression and whether people who had been depressed maybe a decade or 2 decades before, were more likely to get RA.

That calculation has not been done, Dr. Pedersen said, adding that the study also can’t account for people who may have had recurrent depression. Depression treatment guidelines often recommend nonpharmacologic intervention in the first instance, “so we do not necessarily get the right picture of recurrent depression if we look further back.”

Pointing out that the sixfold increase in mortality was impressive, another delegate asked about whether it was because of a higher disease activity or joint damage and if the mortality risk might be lower in patients who are in remission.

“We don’t know that yet,” Dr. Pedersen answered. “We haven’t done the calculations, but there is the issue of residual confounding if we don’t take all relevant covariates into account. So, we need to do that calculation as well.”

The study was supported by the Danish Rheumatism Association. Dr. Pedersen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The development of depression after a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis increased the risk for death “more than sixfold” when compared with having no depression at diagnosis, according to Danish researchers.

Cumulative mortality at 10 years was approximately 37% in patients with comorbid RA and depression versus around 13.5% of RA patients with no depression, Jens Kristian Pedersen, MD, PhD, of Odense (Denmark) University Hospital–Svendborg Hospital and the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, reported at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

“According to [antidepressant] exposure status, the cumulative mortality followed two clearly different paths,” Dr. Pedersen said. “The mortality curves separated early and already within the first and second year of follow-up.”

RA, depression, and mortality

Rates of depression in patients with RA are high, Dr. Pedersen said, and while it’s previously been reported that their coexistence can increase mortality, this is the first time that the link has been investigated in a population newly diagnosed with RA.

In this study, Dr. Pedersen and collaborators wanted to look at the association in incident RA and defined depression as the first filling of an antidepressant prescription.

“Although antidepressants are used for different indications, we have recently described that in RA the most frequent indication for filling antidepressants is depression,” he explained. Moreover, that research found that “the frequency of filling coincides with the occurrence of depressive disorder previously reported in the scientific literature.”

Data sourced from multiple Danish registers

To examine the mortality risk associated with newly diagnosed RA and new-onset depression, Dr. Pedersen described how five different Danish registers were used.

First, data from the DANBIO register were used to identify patients with incident RA living in Denmark over a 10-year period ending in December 2018. Although perhaps widely known as a biologics register, DANBIO is required by the Danish National Board of Health to collect information on all patients with RA, regardless of their treatment.

Next, the Danish National Prescription Register and Danish National Patient Register were consulted to obtain data on patients who had a first prescription for antidepressant treatment and information on those who developed a diagnosis of depression. Demographic, vital status, and socioeconomic data were collated from the Danish Civil Registration System and Statistics Denmark databases.

To be sure they were looking at incident cases of RA and new cases of depression, the researchers excluded anyone with an existing prescription of antidepressants or methotrexate, or who had a confirmed diagnosis of either disorder 3 years prior to the index date of Jan. 1, 2008.

This meant that, from a total population of 18,000 patients in the DANBIO database, there were just over 11,000 who could be included in the analyses.

Overall, the median age at RA diagnosis was 61 years, two-thirds were female, and two-thirds had seropositive disease.

New-onset depression in incident RA

“During follow-up, about 10% filled a prescription of antidepressants,” said Dr. Pedersen, adding that there were 671 deaths, representing around 57,000 person-years at risk.

“The majority died from natural causes,” he said, although the cause of death was unknown in 30% of cases.

Comparing those who did and did not have a prescription for antidepressants, there were some differences in the age at which death occurred, the percentage of females to males, the presence of other comorbidities, and levels of higher education and income. These were all adjusted for in the analyses.

Adjusted hazard rate ratios were calculated to look at the mortality risk in patients who had antidepressant exposure. The highest HRR for mortality with antidepressant use was seen in patients aged 55 years or younger at 6.66, with the next highest HRRs being for male gender (3.70) and seropositive RA (3.45).

But HRRs for seronegative RA, female gender, and age 55-70 years or older than 75 years were all still around 3.0.

Depression definition questioned

“My only concern is about the definition of depression in your analysis,” said a member of the audience at the congress.

“You used antidepressant use as a proxy of depression diagnosis, but it might be that most or many patients have taken [medication] like duloxetine for pain control, and you are just seeing higher disease activity and more aggressive RA.”

Dr. Pedersen responded: “After the EULAR 2022 submission deadline, we reanalyzed our data using two other measures of depression.

“First, we use treatment with antidepressants with a positive indication of depression, according to the prescribing physician, and secondly, we used first diagnosis with depression according to ICD-10 Code F32 – ‘depressive episode after discharge from hospital as an outpatient,’ ” he said.

“All definitions end up with a hazard rate ratio of about three. So, in my opinion, it doesn’t matter whether you focus on one measure of depression or the other.”

David Isenberg, MD, FRCP, professor of rheumatology at University College London, wanted to know more about the antecedent history of depression and whether people who had been depressed maybe a decade or 2 decades before, were more likely to get RA.

That calculation has not been done, Dr. Pedersen said, adding that the study also can’t account for people who may have had recurrent depression. Depression treatment guidelines often recommend nonpharmacologic intervention in the first instance, “so we do not necessarily get the right picture of recurrent depression if we look further back.”

Pointing out that the sixfold increase in mortality was impressive, another delegate asked about whether it was because of a higher disease activity or joint damage and if the mortality risk might be lower in patients who are in remission.

“We don’t know that yet,” Dr. Pedersen answered. “We haven’t done the calculations, but there is the issue of residual confounding if we don’t take all relevant covariates into account. So, we need to do that calculation as well.”

The study was supported by the Danish Rheumatism Association. Dr. Pedersen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The development of depression after a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis increased the risk for death “more than sixfold” when compared with having no depression at diagnosis, according to Danish researchers.

Cumulative mortality at 10 years was approximately 37% in patients with comorbid RA and depression versus around 13.5% of RA patients with no depression, Jens Kristian Pedersen, MD, PhD, of Odense (Denmark) University Hospital–Svendborg Hospital and the department of clinical research at the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, reported at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology.

“According to [antidepressant] exposure status, the cumulative mortality followed two clearly different paths,” Dr. Pedersen said. “The mortality curves separated early and already within the first and second year of follow-up.”

RA, depression, and mortality

Rates of depression in patients with RA are high, Dr. Pedersen said, and while it’s previously been reported that their coexistence can increase mortality, this is the first time that the link has been investigated in a population newly diagnosed with RA.

In this study, Dr. Pedersen and collaborators wanted to look at the association in incident RA and defined depression as the first filling of an antidepressant prescription.

“Although antidepressants are used for different indications, we have recently described that in RA the most frequent indication for filling antidepressants is depression,” he explained. Moreover, that research found that “the frequency of filling coincides with the occurrence of depressive disorder previously reported in the scientific literature.”

Data sourced from multiple Danish registers

To examine the mortality risk associated with newly diagnosed RA and new-onset depression, Dr. Pedersen described how five different Danish registers were used.

First, data from the DANBIO register were used to identify patients with incident RA living in Denmark over a 10-year period ending in December 2018. Although perhaps widely known as a biologics register, DANBIO is required by the Danish National Board of Health to collect information on all patients with RA, regardless of their treatment.

Next, the Danish National Prescription Register and Danish National Patient Register were consulted to obtain data on patients who had a first prescription for antidepressant treatment and information on those who developed a diagnosis of depression. Demographic, vital status, and socioeconomic data were collated from the Danish Civil Registration System and Statistics Denmark databases.

To be sure they were looking at incident cases of RA and new cases of depression, the researchers excluded anyone with an existing prescription of antidepressants or methotrexate, or who had a confirmed diagnosis of either disorder 3 years prior to the index date of Jan. 1, 2008.

This meant that, from a total population of 18,000 patients in the DANBIO database, there were just over 11,000 who could be included in the analyses.

Overall, the median age at RA diagnosis was 61 years, two-thirds were female, and two-thirds had seropositive disease.

New-onset depression in incident RA

“During follow-up, about 10% filled a prescription of antidepressants,” said Dr. Pedersen, adding that there were 671 deaths, representing around 57,000 person-years at risk.

“The majority died from natural causes,” he said, although the cause of death was unknown in 30% of cases.

Comparing those who did and did not have a prescription for antidepressants, there were some differences in the age at which death occurred, the percentage of females to males, the presence of other comorbidities, and levels of higher education and income. These were all adjusted for in the analyses.

Adjusted hazard rate ratios were calculated to look at the mortality risk in patients who had antidepressant exposure. The highest HRR for mortality with antidepressant use was seen in patients aged 55 years or younger at 6.66, with the next highest HRRs being for male gender (3.70) and seropositive RA (3.45).

But HRRs for seronegative RA, female gender, and age 55-70 years or older than 75 years were all still around 3.0.

Depression definition questioned

“My only concern is about the definition of depression in your analysis,” said a member of the audience at the congress.

“You used antidepressant use as a proxy of depression diagnosis, but it might be that most or many patients have taken [medication] like duloxetine for pain control, and you are just seeing higher disease activity and more aggressive RA.”

Dr. Pedersen responded: “After the EULAR 2022 submission deadline, we reanalyzed our data using two other measures of depression.

“First, we use treatment with antidepressants with a positive indication of depression, according to the prescribing physician, and secondly, we used first diagnosis with depression according to ICD-10 Code F32 – ‘depressive episode after discharge from hospital as an outpatient,’ ” he said.

“All definitions end up with a hazard rate ratio of about three. So, in my opinion, it doesn’t matter whether you focus on one measure of depression or the other.”

David Isenberg, MD, FRCP, professor of rheumatology at University College London, wanted to know more about the antecedent history of depression and whether people who had been depressed maybe a decade or 2 decades before, were more likely to get RA.

That calculation has not been done, Dr. Pedersen said, adding that the study also can’t account for people who may have had recurrent depression. Depression treatment guidelines often recommend nonpharmacologic intervention in the first instance, “so we do not necessarily get the right picture of recurrent depression if we look further back.”

Pointing out that the sixfold increase in mortality was impressive, another delegate asked about whether it was because of a higher disease activity or joint damage and if the mortality risk might be lower in patients who are in remission.

“We don’t know that yet,” Dr. Pedersen answered. “We haven’t done the calculations, but there is the issue of residual confounding if we don’t take all relevant covariates into account. So, we need to do that calculation as well.”

The study was supported by the Danish Rheumatism Association. Dr. Pedersen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM THE EULAR 2022 CONGRESS

Adjunctive psychotherapy may offer no benefit in severe depression

Results of a cross-sectional, naturalistic, multicenter European study showed there were no significant differences in response rates between patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who received combination treatment with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication in comparison with those who received antidepressant monotherapy, even when comparing different types of psychotherapy.

This “might emphasize the fundamental role of the underlying complex biological interrelationships in MDD and its treatment,” said study investigator Lucie Bartova, MD, PhD, Clinical Division of General Psychiatry, Medical University of Vienna.

However, she noted that patients who received psychotherapy in combination with antidepressants also had “beneficial sociodemographic and clinical characteristics,” which might reflect poorer access to “psychotherapeutic techniques for patients who are more severely ill and have less socioeconomic privilege.”

The resulting selection bias may cause patients with more severe illness to “fall by the wayside,” Dr. Bartova said.

Lead researcher Siegfried Kasper, MD, also from the Medical University of Vienna, agreed, saying in a press release that, by implication, “additional psychotherapy tends to be given to more highly educated and healthier patients, which may reflect the greater availability of psychotherapy to more socially and economically advantaged patients.”

The findings, some of which were previously published in the Journal of Psychiatry Research, were presented at the virtual European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress.

Inconsistent guidelines

During her presentation, Dr. Bartova said that while “numerous effective antidepressant strategies are available for the treatment of MDD, many patients do not achieve a satisfactory treatment response,” which often leads to further management refinement and the use of off-label treatments.

She continued, saying that the “most obvious” approach in these situations is to try the available treatment options in a “systematic and individualized” manner, ideally by following recommended treatment algorithms.

Meta-analyses have suggested that standardized psychotherapy with fixed, regular sessions that follows an established rationale and is based on a defined school of thought is effective in MDD, “with at least moderate effects.”

Among the psychotherapy approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the “best and most investigated,” Dr. Bartova said, but international clinical practice guidelines “lack consistency” regarding recommendations for psychotherapy.

To examine the use and impact of psychotherapy for MDD patients, the researchers studied 1,410 adult inpatients and outpatients from 10 centers in eight countries who were surveyed between 2011 and 2016 by the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression.

Participants were assessed via the Mini–International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Results showed that among 1,279 MDD patients who were included in the final analysis, 880 (68.8%) received only antidepressants, while 399 (31.2%) received some form of structured psychotherapy as part of their treatment.

These patients included 22.8% who received CBT, 3.4% who underwent psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and 1.3% who received systemic psychotherapy. The additional psychotherapy was not specified for 3.8%.

Dr. Bartova explained that the use of psychotherapy in combination pharmacologic treatment was significantly associated with younger age, higher educational attainment, and ongoing employment in comparison with antidepressant use alone (P < .001 for all).

In addition, combination therapy was associated with an earlier average age of MDD onset, lower severity of current depressive symptoms, a lower risk of suicidality, higher rates of additional melancholic features in the patients’ symptomatology, and higher rates of comorbid asthma and migraine (P < .001 for all).

There was also a significant association between the use of psychotherapy plus pharmacologic treatment and lower average daily doses of first-line antidepressant medication (P < .001), as well as more frequent administration of agomelatine (P < .001) and a trend toward greater use of vortioxetine (P = .006).

In contrast, among patients who received antidepressants alone, there was a trend toward higher rates of additional psychotic features (P = .054), and the patients were more likely to have received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as their first-line antidepressant medication (P < .001).

The researchers found there was no significant difference in rates of response, nonresponse, and treatment-resistant depression (TRD) between patients who received combination psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy and those who received antidepressants alone (P = .369).

Dr. Bartova showed that 25.8% of MDD patients who received combination therapy were classified as responders, compared with 23.5% of those given only antidepressants. Nonresponse was identified in 35.6% and 33.8% of patients, respectively, while 38.6% versus 42.7% had TRD.

Dr. Bartova and colleagues performed an additional analysis to determine whether there was any difference in response depending on the type of psychotherapy.

They divided patients who received combination therapy into those who had received CBT and those who had been given another form of psychotherapy.

Again, there were no significant differences in response, nonresponse, and TRD (P = .256). The response rate was 27.1% among patients given combination CBT, versus 22.4% among those who received another psychotherapy.

“Despite clinical guidelines and studies which advocate for psychotherapy and combining psychotherapy with antidepressants, this study shows that in real life, no added value can be demonstrated for psychotherapy in those already treated with antidepressants for severe depression,” Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, Collaborative Antwerp Psychiatric Research Institute, University of Antwerp, Belgium, said in the press release.

“This doesn’t necessarily mean that psychotherapy is not useful, but it is a clear sign that the way we are currently managing these depressed patients with psychotherapy is not effective and needs critical evaluation,” added Dr. De Picker, who was not involved in the research.

However, Michael E. Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization that the current study “is a secondary analysis of a naturalistic study.”

Consequently, it is not possible to account for the “dose and duration, and quality, of the psychotherapy provided.”

Therefore, the findings simply suggest that “the kinds of psychotherapy provided to these patients was not so powerful that people who received it consistently did better than those who did not,” Dr. Thase said.

The European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression obtained an unrestricted grant sponsored by Lundbeck A/S. Dr. Bartova has relationships with AOP Orphan, Medizin Medien Austria, Universimed, Vertretungsnetz, Dialectica, Diagnosia, Schwabe, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Angelini. No other relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a cross-sectional, naturalistic, multicenter European study showed there were no significant differences in response rates between patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who received combination treatment with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication in comparison with those who received antidepressant monotherapy, even when comparing different types of psychotherapy.

This “might emphasize the fundamental role of the underlying complex biological interrelationships in MDD and its treatment,” said study investigator Lucie Bartova, MD, PhD, Clinical Division of General Psychiatry, Medical University of Vienna.

However, she noted that patients who received psychotherapy in combination with antidepressants also had “beneficial sociodemographic and clinical characteristics,” which might reflect poorer access to “psychotherapeutic techniques for patients who are more severely ill and have less socioeconomic privilege.”

The resulting selection bias may cause patients with more severe illness to “fall by the wayside,” Dr. Bartova said.

Lead researcher Siegfried Kasper, MD, also from the Medical University of Vienna, agreed, saying in a press release that, by implication, “additional psychotherapy tends to be given to more highly educated and healthier patients, which may reflect the greater availability of psychotherapy to more socially and economically advantaged patients.”

The findings, some of which were previously published in the Journal of Psychiatry Research, were presented at the virtual European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress.

Inconsistent guidelines

During her presentation, Dr. Bartova said that while “numerous effective antidepressant strategies are available for the treatment of MDD, many patients do not achieve a satisfactory treatment response,” which often leads to further management refinement and the use of off-label treatments.

She continued, saying that the “most obvious” approach in these situations is to try the available treatment options in a “systematic and individualized” manner, ideally by following recommended treatment algorithms.

Meta-analyses have suggested that standardized psychotherapy with fixed, regular sessions that follows an established rationale and is based on a defined school of thought is effective in MDD, “with at least moderate effects.”

Among the psychotherapy approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the “best and most investigated,” Dr. Bartova said, but international clinical practice guidelines “lack consistency” regarding recommendations for psychotherapy.

To examine the use and impact of psychotherapy for MDD patients, the researchers studied 1,410 adult inpatients and outpatients from 10 centers in eight countries who were surveyed between 2011 and 2016 by the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression.

Participants were assessed via the Mini–International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Results showed that among 1,279 MDD patients who were included in the final analysis, 880 (68.8%) received only antidepressants, while 399 (31.2%) received some form of structured psychotherapy as part of their treatment.

These patients included 22.8% who received CBT, 3.4% who underwent psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and 1.3% who received systemic psychotherapy. The additional psychotherapy was not specified for 3.8%.

Dr. Bartova explained that the use of psychotherapy in combination pharmacologic treatment was significantly associated with younger age, higher educational attainment, and ongoing employment in comparison with antidepressant use alone (P < .001 for all).

In addition, combination therapy was associated with an earlier average age of MDD onset, lower severity of current depressive symptoms, a lower risk of suicidality, higher rates of additional melancholic features in the patients’ symptomatology, and higher rates of comorbid asthma and migraine (P < .001 for all).

There was also a significant association between the use of psychotherapy plus pharmacologic treatment and lower average daily doses of first-line antidepressant medication (P < .001), as well as more frequent administration of agomelatine (P < .001) and a trend toward greater use of vortioxetine (P = .006).

In contrast, among patients who received antidepressants alone, there was a trend toward higher rates of additional psychotic features (P = .054), and the patients were more likely to have received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as their first-line antidepressant medication (P < .001).

The researchers found there was no significant difference in rates of response, nonresponse, and treatment-resistant depression (TRD) between patients who received combination psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy and those who received antidepressants alone (P = .369).

Dr. Bartova showed that 25.8% of MDD patients who received combination therapy were classified as responders, compared with 23.5% of those given only antidepressants. Nonresponse was identified in 35.6% and 33.8% of patients, respectively, while 38.6% versus 42.7% had TRD.

Dr. Bartova and colleagues performed an additional analysis to determine whether there was any difference in response depending on the type of psychotherapy.

They divided patients who received combination therapy into those who had received CBT and those who had been given another form of psychotherapy.

Again, there were no significant differences in response, nonresponse, and TRD (P = .256). The response rate was 27.1% among patients given combination CBT, versus 22.4% among those who received another psychotherapy.

“Despite clinical guidelines and studies which advocate for psychotherapy and combining psychotherapy with antidepressants, this study shows that in real life, no added value can be demonstrated for psychotherapy in those already treated with antidepressants for severe depression,” Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, Collaborative Antwerp Psychiatric Research Institute, University of Antwerp, Belgium, said in the press release.

“This doesn’t necessarily mean that psychotherapy is not useful, but it is a clear sign that the way we are currently managing these depressed patients with psychotherapy is not effective and needs critical evaluation,” added Dr. De Picker, who was not involved in the research.

However, Michael E. Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization that the current study “is a secondary analysis of a naturalistic study.”

Consequently, it is not possible to account for the “dose and duration, and quality, of the psychotherapy provided.”

Therefore, the findings simply suggest that “the kinds of psychotherapy provided to these patients was not so powerful that people who received it consistently did better than those who did not,” Dr. Thase said.

The European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression obtained an unrestricted grant sponsored by Lundbeck A/S. Dr. Bartova has relationships with AOP Orphan, Medizin Medien Austria, Universimed, Vertretungsnetz, Dialectica, Diagnosia, Schwabe, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Angelini. No other relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results of a cross-sectional, naturalistic, multicenter European study showed there were no significant differences in response rates between patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who received combination treatment with psychotherapy and antidepressant medication in comparison with those who received antidepressant monotherapy, even when comparing different types of psychotherapy.

This “might emphasize the fundamental role of the underlying complex biological interrelationships in MDD and its treatment,” said study investigator Lucie Bartova, MD, PhD, Clinical Division of General Psychiatry, Medical University of Vienna.

However, she noted that patients who received psychotherapy in combination with antidepressants also had “beneficial sociodemographic and clinical characteristics,” which might reflect poorer access to “psychotherapeutic techniques for patients who are more severely ill and have less socioeconomic privilege.”

The resulting selection bias may cause patients with more severe illness to “fall by the wayside,” Dr. Bartova said.

Lead researcher Siegfried Kasper, MD, also from the Medical University of Vienna, agreed, saying in a press release that, by implication, “additional psychotherapy tends to be given to more highly educated and healthier patients, which may reflect the greater availability of psychotherapy to more socially and economically advantaged patients.”

The findings, some of which were previously published in the Journal of Psychiatry Research, were presented at the virtual European Psychiatric Association 2022 Congress.

Inconsistent guidelines

During her presentation, Dr. Bartova said that while “numerous effective antidepressant strategies are available for the treatment of MDD, many patients do not achieve a satisfactory treatment response,” which often leads to further management refinement and the use of off-label treatments.

She continued, saying that the “most obvious” approach in these situations is to try the available treatment options in a “systematic and individualized” manner, ideally by following recommended treatment algorithms.

Meta-analyses have suggested that standardized psychotherapy with fixed, regular sessions that follows an established rationale and is based on a defined school of thought is effective in MDD, “with at least moderate effects.”

Among the psychotherapy approaches, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the “best and most investigated,” Dr. Bartova said, but international clinical practice guidelines “lack consistency” regarding recommendations for psychotherapy.

To examine the use and impact of psychotherapy for MDD patients, the researchers studied 1,410 adult inpatients and outpatients from 10 centers in eight countries who were surveyed between 2011 and 2016 by the European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression.

Participants were assessed via the Mini–International Neuropsychiatric Interview, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

Results showed that among 1,279 MDD patients who were included in the final analysis, 880 (68.8%) received only antidepressants, while 399 (31.2%) received some form of structured psychotherapy as part of their treatment.

These patients included 22.8% who received CBT, 3.4% who underwent psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and 1.3% who received systemic psychotherapy. The additional psychotherapy was not specified for 3.8%.

Dr. Bartova explained that the use of psychotherapy in combination pharmacologic treatment was significantly associated with younger age, higher educational attainment, and ongoing employment in comparison with antidepressant use alone (P < .001 for all).

In addition, combination therapy was associated with an earlier average age of MDD onset, lower severity of current depressive symptoms, a lower risk of suicidality, higher rates of additional melancholic features in the patients’ symptomatology, and higher rates of comorbid asthma and migraine (P < .001 for all).

There was also a significant association between the use of psychotherapy plus pharmacologic treatment and lower average daily doses of first-line antidepressant medication (P < .001), as well as more frequent administration of agomelatine (P < .001) and a trend toward greater use of vortioxetine (P = .006).

In contrast, among patients who received antidepressants alone, there was a trend toward higher rates of additional psychotic features (P = .054), and the patients were more likely to have received selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as their first-line antidepressant medication (P < .001).

The researchers found there was no significant difference in rates of response, nonresponse, and treatment-resistant depression (TRD) between patients who received combination psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy and those who received antidepressants alone (P = .369).

Dr. Bartova showed that 25.8% of MDD patients who received combination therapy were classified as responders, compared with 23.5% of those given only antidepressants. Nonresponse was identified in 35.6% and 33.8% of patients, respectively, while 38.6% versus 42.7% had TRD.

Dr. Bartova and colleagues performed an additional analysis to determine whether there was any difference in response depending on the type of psychotherapy.

They divided patients who received combination therapy into those who had received CBT and those who had been given another form of psychotherapy.

Again, there were no significant differences in response, nonresponse, and TRD (P = .256). The response rate was 27.1% among patients given combination CBT, versus 22.4% among those who received another psychotherapy.

“Despite clinical guidelines and studies which advocate for psychotherapy and combining psychotherapy with antidepressants, this study shows that in real life, no added value can be demonstrated for psychotherapy in those already treated with antidepressants for severe depression,” Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, Collaborative Antwerp Psychiatric Research Institute, University of Antwerp, Belgium, said in the press release.

“This doesn’t necessarily mean that psychotherapy is not useful, but it is a clear sign that the way we are currently managing these depressed patients with psychotherapy is not effective and needs critical evaluation,” added Dr. De Picker, who was not involved in the research.

However, Michael E. Thase, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization that the current study “is a secondary analysis of a naturalistic study.”

Consequently, it is not possible to account for the “dose and duration, and quality, of the psychotherapy provided.”

Therefore, the findings simply suggest that “the kinds of psychotherapy provided to these patients was not so powerful that people who received it consistently did better than those who did not,” Dr. Thase said.

The European Group for the Study of Resistant Depression obtained an unrestricted grant sponsored by Lundbeck A/S. Dr. Bartova has relationships with AOP Orphan, Medizin Medien Austria, Universimed, Vertretungsnetz, Dialectica, Diagnosia, Schwabe, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Angelini. No other relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EPA 2022

Synthetic opioid use up almost 800% nationwide

The results of a national urine drug test (UDT) study come as the United States is reporting a record-high number of drug overdose deaths – more than 80% of which involved fentanyl or other synthetic opioids and prompting a push for better surveillance models.

Researchers found that UDTs can be used to accurately identify which drugs are circulating in a community, revealing in just a matter of days critically important drug use trends that current surveillance methods take a month or longer to report.

The faster turnaround could potentially allow clinicians and public health officials to be more proactive with targeted overdose prevention and harm-reduction strategies such as distribution of naloxone and fentanyl test strips.

“We’re talking about trying to come up with an early-warning system,” study author Steven Passik, PhD, vice president for scientific affairs for Millennium Health, San Diego, Calif., told this news organization. “We’re trying to find out if we can let people in the harm reduction and treatment space know about what might be coming weeks or a month or more in advance so that some interventions could be marshaled.”

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Call for better surveillance

More than 100,000 people in the United States died of an unintended drug overdose in 2021, a record high and a 15% increase over 2020 figures, which also set a record.

Part of the federal government’s plan to address the crisis includes strengthening epidemiologic efforts by better collection and mining of public health surveillance data.

Sources currently used to detect drug use trends include mortality data, poison control centers, emergency departments, electronic health records, and crime laboratories. But analysis of these sources can take weeks or more.

“One of the real challenges in addressing and reducing overdose deaths has been the relative lack of accessible real-time data that can support agile responses to deployment of resources in a specific geographic region,” study coauthor Rebecca Jackson, MD, professor and associate dean for clinical and translational research at Ohio State University in Columbus, said in an interview.

Ohio State researchers partnered with scientists at Millennium Health, one of the largest urine test labs in the United States, on a cross-sectional study to find out if UDTs could be an accurate and speedier tool for drug surveillance.

They analyzed 500,000 unique urine samples from patients in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities in all 50 states from 2013 to 2020, comparing levels of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, synthetic opioids, and other opioids found in the samples to levels of the same drugs from overdose mortality data at the national, state, and county level from the National Vital Statistics System.

On a national level, synthetic opioids and methamphetamine were highly correlated with overdose mortality data (Spearman’s rho = .96 for both). When synthetic opioids were coinvolved, methamphetamine (rho = .98), heroin (rho = .78), cocaine (rho = .94), and other opioids (rho = .83) were also highly correlated with overdose mortality data.

Similar correlations were found when examining state-level data from 24 states and at the county level upon analysis of 19 counties in Ohio.

A changing landscape

Researchers said the strong correlation between overdose deaths and UDT results for synthetic opioids and methamphetamine are likely explained by the drugs’ availability and lethality.

“The most important thing that we found was just the strength of the correlation, which goes right to the heart of why we considered correlation to be so critical,” lead author Penn Whitley, senior director of bioinformatics for Millennium Health, told this news organization. “We needed to demonstrate that there was a strong correlation of just the UDT positivity rates with mortality – in this case, fatal drug overdose rates – as a steppingstone to build out tools that could utilize UDT as a real-time data source.”

While the main goal of the study was to establish correlation between UDT results and national mortality data, the study also offers a view of a changing landscape in the opioid epidemic.

Overall, UDT positivity for total synthetic opioids increased from 2.1% in 2013 to 19.1% in 2020 (a 792.5% increase). Positivity rates for all included drug categories increased when synthetic opioids were present.

However, in the absence of synthetic opioids, UDT positivity decreased for almost all drug categories from 2013 to 2020 (from 7.7% to 4.7% for cocaine; 3.9% to 1.6% for heroin; 20.5% to 6.9% for other opioids).

Only methamphetamine positivity increased with or without involvement of synthetic opioids. With synthetic opioids, meth positivity rose from 0.1% in 2013 to 7.9% in 2020. Without them, meth positivity rates still rose, from 2.1% in 2013 to 13.1% in 2020.

The findings track with an earlier study showing methamphetamine-involved overdose deaths rose sharply between 2011 and 2018.

“The data from this manuscript support that the opioid epidemic is transitioning from an opioid epidemic to a polysubstance epidemic where illicit synthetic opioids, largely fentanyl, in combination with other substances are now responsible for upwards of 80% of OD deaths,” Dr. Jackson said.

In an accompanying editorial Jeffrey Brent, MD, PhD, clinical professor in internal medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and Stephanie T. Weiss, MD, PhD, staff clinician in the Translational Addiction Medicine Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Baltimore, note that as new agents emerge, different harm-reduction strategies will be needed, adding that having a real-time tool to identify the trends will be key to preventing deaths.

“Surveillance systems are an integral component of reducing morbidity and mortality associated with illicit drug use. On local, regional, and national levels, information of this type is needed to most efficiently allocate limited resources to maximize benefit and save lives,” Dr. Brent and Dr. Weiss write.

The study was funded by Millennium Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Full disclosures are included in the original articles, but no sources reported conflicts related to the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results of a national urine drug test (UDT) study come as the United States is reporting a record-high number of drug overdose deaths – more than 80% of which involved fentanyl or other synthetic opioids and prompting a push for better surveillance models.

Researchers found that UDTs can be used to accurately identify which drugs are circulating in a community, revealing in just a matter of days critically important drug use trends that current surveillance methods take a month or longer to report.

The faster turnaround could potentially allow clinicians and public health officials to be more proactive with targeted overdose prevention and harm-reduction strategies such as distribution of naloxone and fentanyl test strips.

“We’re talking about trying to come up with an early-warning system,” study author Steven Passik, PhD, vice president for scientific affairs for Millennium Health, San Diego, Calif., told this news organization. “We’re trying to find out if we can let people in the harm reduction and treatment space know about what might be coming weeks or a month or more in advance so that some interventions could be marshaled.”

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Call for better surveillance

More than 100,000 people in the United States died of an unintended drug overdose in 2021, a record high and a 15% increase over 2020 figures, which also set a record.

Part of the federal government’s plan to address the crisis includes strengthening epidemiologic efforts by better collection and mining of public health surveillance data.

Sources currently used to detect drug use trends include mortality data, poison control centers, emergency departments, electronic health records, and crime laboratories. But analysis of these sources can take weeks or more.

“One of the real challenges in addressing and reducing overdose deaths has been the relative lack of accessible real-time data that can support agile responses to deployment of resources in a specific geographic region,” study coauthor Rebecca Jackson, MD, professor and associate dean for clinical and translational research at Ohio State University in Columbus, said in an interview.

Ohio State researchers partnered with scientists at Millennium Health, one of the largest urine test labs in the United States, on a cross-sectional study to find out if UDTs could be an accurate and speedier tool for drug surveillance.

They analyzed 500,000 unique urine samples from patients in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities in all 50 states from 2013 to 2020, comparing levels of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, synthetic opioids, and other opioids found in the samples to levels of the same drugs from overdose mortality data at the national, state, and county level from the National Vital Statistics System.

On a national level, synthetic opioids and methamphetamine were highly correlated with overdose mortality data (Spearman’s rho = .96 for both). When synthetic opioids were coinvolved, methamphetamine (rho = .98), heroin (rho = .78), cocaine (rho = .94), and other opioids (rho = .83) were also highly correlated with overdose mortality data.

Similar correlations were found when examining state-level data from 24 states and at the county level upon analysis of 19 counties in Ohio.

A changing landscape

Researchers said the strong correlation between overdose deaths and UDT results for synthetic opioids and methamphetamine are likely explained by the drugs’ availability and lethality.

“The most important thing that we found was just the strength of the correlation, which goes right to the heart of why we considered correlation to be so critical,” lead author Penn Whitley, senior director of bioinformatics for Millennium Health, told this news organization. “We needed to demonstrate that there was a strong correlation of just the UDT positivity rates with mortality – in this case, fatal drug overdose rates – as a steppingstone to build out tools that could utilize UDT as a real-time data source.”

While the main goal of the study was to establish correlation between UDT results and national mortality data, the study also offers a view of a changing landscape in the opioid epidemic.

Overall, UDT positivity for total synthetic opioids increased from 2.1% in 2013 to 19.1% in 2020 (a 792.5% increase). Positivity rates for all included drug categories increased when synthetic opioids were present.

However, in the absence of synthetic opioids, UDT positivity decreased for almost all drug categories from 2013 to 2020 (from 7.7% to 4.7% for cocaine; 3.9% to 1.6% for heroin; 20.5% to 6.9% for other opioids).

Only methamphetamine positivity increased with or without involvement of synthetic opioids. With synthetic opioids, meth positivity rose from 0.1% in 2013 to 7.9% in 2020. Without them, meth positivity rates still rose, from 2.1% in 2013 to 13.1% in 2020.

The findings track with an earlier study showing methamphetamine-involved overdose deaths rose sharply between 2011 and 2018.

“The data from this manuscript support that the opioid epidemic is transitioning from an opioid epidemic to a polysubstance epidemic where illicit synthetic opioids, largely fentanyl, in combination with other substances are now responsible for upwards of 80% of OD deaths,” Dr. Jackson said.

In an accompanying editorial Jeffrey Brent, MD, PhD, clinical professor in internal medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and Stephanie T. Weiss, MD, PhD, staff clinician in the Translational Addiction Medicine Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Baltimore, note that as new agents emerge, different harm-reduction strategies will be needed, adding that having a real-time tool to identify the trends will be key to preventing deaths.

“Surveillance systems are an integral component of reducing morbidity and mortality associated with illicit drug use. On local, regional, and national levels, information of this type is needed to most efficiently allocate limited resources to maximize benefit and save lives,” Dr. Brent and Dr. Weiss write.

The study was funded by Millennium Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Full disclosures are included in the original articles, but no sources reported conflicts related to the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results of a national urine drug test (UDT) study come as the United States is reporting a record-high number of drug overdose deaths – more than 80% of which involved fentanyl or other synthetic opioids and prompting a push for better surveillance models.

Researchers found that UDTs can be used to accurately identify which drugs are circulating in a community, revealing in just a matter of days critically important drug use trends that current surveillance methods take a month or longer to report.

The faster turnaround could potentially allow clinicians and public health officials to be more proactive with targeted overdose prevention and harm-reduction strategies such as distribution of naloxone and fentanyl test strips.

“We’re talking about trying to come up with an early-warning system,” study author Steven Passik, PhD, vice president for scientific affairs for Millennium Health, San Diego, Calif., told this news organization. “We’re trying to find out if we can let people in the harm reduction and treatment space know about what might be coming weeks or a month or more in advance so that some interventions could be marshaled.”

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Call for better surveillance

More than 100,000 people in the United States died of an unintended drug overdose in 2021, a record high and a 15% increase over 2020 figures, which also set a record.

Part of the federal government’s plan to address the crisis includes strengthening epidemiologic efforts by better collection and mining of public health surveillance data.

Sources currently used to detect drug use trends include mortality data, poison control centers, emergency departments, electronic health records, and crime laboratories. But analysis of these sources can take weeks or more.

“One of the real challenges in addressing and reducing overdose deaths has been the relative lack of accessible real-time data that can support agile responses to deployment of resources in a specific geographic region,” study coauthor Rebecca Jackson, MD, professor and associate dean for clinical and translational research at Ohio State University in Columbus, said in an interview.

Ohio State researchers partnered with scientists at Millennium Health, one of the largest urine test labs in the United States, on a cross-sectional study to find out if UDTs could be an accurate and speedier tool for drug surveillance.

They analyzed 500,000 unique urine samples from patients in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment facilities in all 50 states from 2013 to 2020, comparing levels of cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, synthetic opioids, and other opioids found in the samples to levels of the same drugs from overdose mortality data at the national, state, and county level from the National Vital Statistics System.

On a national level, synthetic opioids and methamphetamine were highly correlated with overdose mortality data (Spearman’s rho = .96 for both). When synthetic opioids were coinvolved, methamphetamine (rho = .98), heroin (rho = .78), cocaine (rho = .94), and other opioids (rho = .83) were also highly correlated with overdose mortality data.

Similar correlations were found when examining state-level data from 24 states and at the county level upon analysis of 19 counties in Ohio.

A changing landscape

Researchers said the strong correlation between overdose deaths and UDT results for synthetic opioids and methamphetamine are likely explained by the drugs’ availability and lethality.

“The most important thing that we found was just the strength of the correlation, which goes right to the heart of why we considered correlation to be so critical,” lead author Penn Whitley, senior director of bioinformatics for Millennium Health, told this news organization. “We needed to demonstrate that there was a strong correlation of just the UDT positivity rates with mortality – in this case, fatal drug overdose rates – as a steppingstone to build out tools that could utilize UDT as a real-time data source.”

While the main goal of the study was to establish correlation between UDT results and national mortality data, the study also offers a view of a changing landscape in the opioid epidemic.

Overall, UDT positivity for total synthetic opioids increased from 2.1% in 2013 to 19.1% in 2020 (a 792.5% increase). Positivity rates for all included drug categories increased when synthetic opioids were present.

However, in the absence of synthetic opioids, UDT positivity decreased for almost all drug categories from 2013 to 2020 (from 7.7% to 4.7% for cocaine; 3.9% to 1.6% for heroin; 20.5% to 6.9% for other opioids).

Only methamphetamine positivity increased with or without involvement of synthetic opioids. With synthetic opioids, meth positivity rose from 0.1% in 2013 to 7.9% in 2020. Without them, meth positivity rates still rose, from 2.1% in 2013 to 13.1% in 2020.

The findings track with an earlier study showing methamphetamine-involved overdose deaths rose sharply between 2011 and 2018.

“The data from this manuscript support that the opioid epidemic is transitioning from an opioid epidemic to a polysubstance epidemic where illicit synthetic opioids, largely fentanyl, in combination with other substances are now responsible for upwards of 80% of OD deaths,” Dr. Jackson said.

In an accompanying editorial Jeffrey Brent, MD, PhD, clinical professor in internal medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and Stephanie T. Weiss, MD, PhD, staff clinician in the Translational Addiction Medicine Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Baltimore, note that as new agents emerge, different harm-reduction strategies will be needed, adding that having a real-time tool to identify the trends will be key to preventing deaths.

“Surveillance systems are an integral component of reducing morbidity and mortality associated with illicit drug use. On local, regional, and national levels, information of this type is needed to most efficiently allocate limited resources to maximize benefit and save lives,” Dr. Brent and Dr. Weiss write.

The study was funded by Millennium Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Full disclosures are included in the original articles, but no sources reported conflicts related to the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

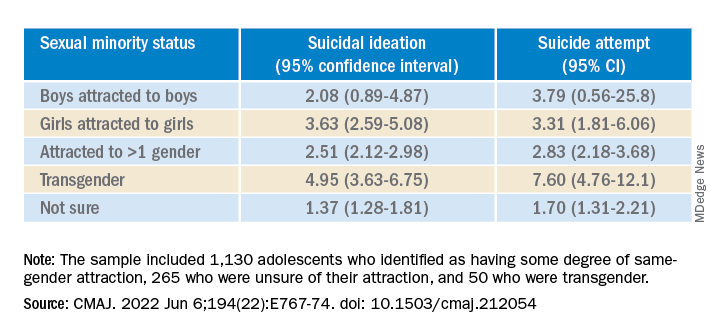

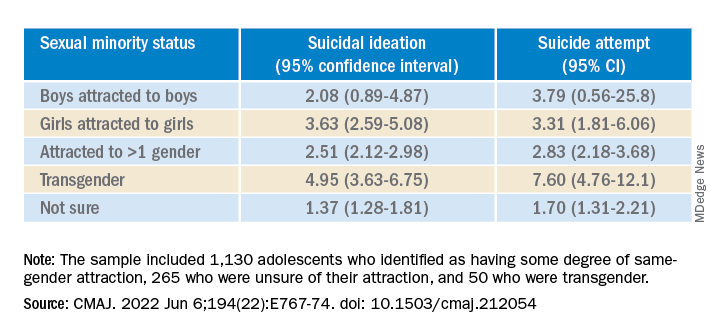

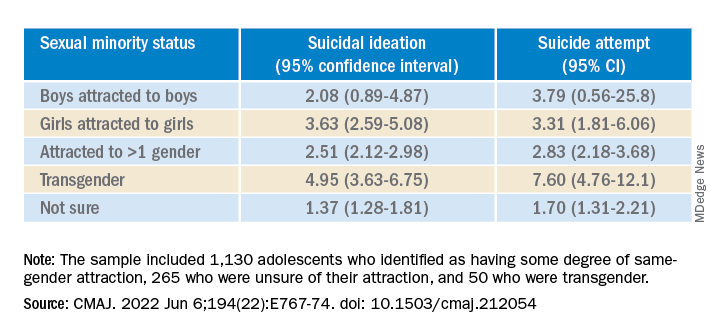

A ‘crisis’ of suicidal thoughts, attempts in transgender youth

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transgender youth are significantly more likely to consider suicide and attempt it, compared with their cisgender peers, new research shows.

In a large population-based study, investigators found the increased risk of suicidality is partly because of bullying and cyberbullying experienced by transgender teens.

The findings are “extremely concerning and should be a wake-up call,” Ian Colman, PhD, with the University of Ottawa School of Epidemiology and Public Health, said in an interview.

Young people who are exploring their sexual identities may suffer from depression and anxiety, both about the reactions of their peers and families, as well as their own sense of self.

“These youth are highly marginalized and stigmatized in many corners of our society, and these findings highlight just how distressing these experiences can be,” Dr. Colman said.

The study was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Sevenfold increased risk of attempted suicide

The risk of suicidal thoughts and actions is not well studied in transgender and nonbinary youth.

To expand the evidence base, the researchers analyzed data for 6,800 adolescents aged 15-17 years from the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth.

The sample included 1,130 (16.5%) adolescents who identified as having some degree of same-gender attraction, 265 (4.3%) who were unsure of their attraction (“questioning”), and 50 (0.6%) who were transgender, meaning they identified as being of a gender different from that assigned at birth.

Overall, 980 (14.0%) adolescents reported having thoughts of suicide in the prior year, and 480 (6.8%) had attempted suicide in their life.

Transgender youth were five times more likely to think about suicide and more than seven times more likely to have ever attempted suicide than cisgender, heterosexual peers.

Among cisgender adolescents, girls who were attracted to girls had 3.6 times the risk of suicidal ideation and 3.3 times the risk of having ever attempted suicide, compared with their heterosexual peers.

Teens attracted to multiple genders had more than twice the risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. Youth who were questioning their sexual orientation had twice the risk of having attempted suicide in their lifetime.

A crisis – with reason for hope

“This is a crisis, and it shows just how much more needs to be done to support transgender young people,” co-author Fae Johnstone, MSW, executive director, Wisdom2Action, who is a trans woman herself, said in the news release.

“Suicide prevention programs specifically targeted to transgender, nonbinary, and sexual minority adolescents, as well as gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents, may help reduce the burden of suicidality among this group,” Ms. Johnstone added.

“The most important thing that parents, teachers, and health care providers can do is to be supportive of these youth,” Dr. Colman told this news organization.

“Providing a safe place where gender and sexual minorities can explore and express themselves is crucial. The first step is to listen and to be compassionate,” Dr. Colman added.

Reached for comment, Jess Ting, MD, director of surgery at the Mount Sinai Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery, New York, said the data from this study on suicidal thoughts and actions among sexual minority and transgender adolescents “mirror what we see and what we know” about suicidality in trans and nonbinary adults.

“The reasons for this are complex, and it’s hard for someone who doesn’t have a lived experience as a trans or nonbinary person to understand the reasons for suicidality,” he told this news organization.

“But we also know that there are higher rates of anxiety and depression and self-image issues and posttraumatic stress disorder, not to mention outside factors – marginalization, discrimination, violence, abuse. When you add up all these intrinsic and extrinsic factors, it’s not hard to believe that there is a high rate of suicidality,” Dr. Ting said.

“There have been studies that have shown that in children who are supported in their gender identity, the rates of depression and anxiety decreased to almost the same levels as non-trans and nonbinary children, so I think that gives cause for hope,” Dr. Ting added.

The study was funded in part by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme and by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award. Ms. Johnstone reports consulting fees from Spectrum Waterloo and volunteer participation with the Youth Suicide Prevention Leadership Committee of Ontario. No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Ting has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

New studies show growing number of trans, nonbinary youth in U.S.

Two new studies point to an ever-increasing number of young people in the United States who identify as transgender and nonbinary, with the figures doubling among 18- to 24-year-olds in one institute’s research – from 0.66% of the population in 2016 to 1.3% (398,900) in 2022.

In addition, 1.4% (300,100) of 13- to 17-year-olds identify as trans or nonbinary, according to the report from that group, the Williams Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law.

Williams, which conducts independent research on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, did not contain data on 13- to 17-year-olds in its 2016 study, so the growth in that group over the past 5+ years is not as well documented.

Overall, some 1.6 million Americans older than age 13 now identify as transgender, reported the Williams researchers.