User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Is the WHO’s HPV vaccination target within reach?

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

FROM PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Pink papule on thigh

A deep-shave biopsy indicated that this was an inflamed/irritated solitary neurofibroma. Basal cell carcinoma, inflamed nevus, and Merkel cell carcinoma were also considered.

Most often manifesting in adults, solitary neurofibromas are common nonencapsulated, soft to firm papules that range in size from 2 mm to 2 cm. Solitary neurofibromas are benign and work-up for systemic neurofibromatosis is not indicated. However, if a patient presents with multiple neurofibromas, axillary freckling, or multiple café au lait macules, systemic disease should be considered, followed by molecular testing and/or referral to a medical geneticist or neurofibromatosis clinic.

Although both the triage amalgamated diagnostic algorithm and the 2-step dermoscopy algorithm suggested this lesion was higher risk, it was ultimately found to be benign. This case highlights areas in which dermoscopy and physical exam lack specificity, but this trade-off increases the sensitivity of an algorithmic approach. Solitary pink papules can include some subtle, but fearsome, diagnoses and deserve close attention. In this case, the biopsy not only helped confirm the diagnosis, but it also alleviated the discomfort caused by the neurofibroma.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Geller S, Pulitzer M, Brady MS, et al. Dermoscopic assessment of vascular structures in solitary small pink lesions—differentiating between good and evil. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:47-50. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0703a10

A deep-shave biopsy indicated that this was an inflamed/irritated solitary neurofibroma. Basal cell carcinoma, inflamed nevus, and Merkel cell carcinoma were also considered.

Most often manifesting in adults, solitary neurofibromas are common nonencapsulated, soft to firm papules that range in size from 2 mm to 2 cm. Solitary neurofibromas are benign and work-up for systemic neurofibromatosis is not indicated. However, if a patient presents with multiple neurofibromas, axillary freckling, or multiple café au lait macules, systemic disease should be considered, followed by molecular testing and/or referral to a medical geneticist or neurofibromatosis clinic.

Although both the triage amalgamated diagnostic algorithm and the 2-step dermoscopy algorithm suggested this lesion was higher risk, it was ultimately found to be benign. This case highlights areas in which dermoscopy and physical exam lack specificity, but this trade-off increases the sensitivity of an algorithmic approach. Solitary pink papules can include some subtle, but fearsome, diagnoses and deserve close attention. In this case, the biopsy not only helped confirm the diagnosis, but it also alleviated the discomfort caused by the neurofibroma.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A deep-shave biopsy indicated that this was an inflamed/irritated solitary neurofibroma. Basal cell carcinoma, inflamed nevus, and Merkel cell carcinoma were also considered.

Most often manifesting in adults, solitary neurofibromas are common nonencapsulated, soft to firm papules that range in size from 2 mm to 2 cm. Solitary neurofibromas are benign and work-up for systemic neurofibromatosis is not indicated. However, if a patient presents with multiple neurofibromas, axillary freckling, or multiple café au lait macules, systemic disease should be considered, followed by molecular testing and/or referral to a medical geneticist or neurofibromatosis clinic.

Although both the triage amalgamated diagnostic algorithm and the 2-step dermoscopy algorithm suggested this lesion was higher risk, it was ultimately found to be benign. This case highlights areas in which dermoscopy and physical exam lack specificity, but this trade-off increases the sensitivity of an algorithmic approach. Solitary pink papules can include some subtle, but fearsome, diagnoses and deserve close attention. In this case, the biopsy not only helped confirm the diagnosis, but it also alleviated the discomfort caused by the neurofibroma.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Geller S, Pulitzer M, Brady MS, et al. Dermoscopic assessment of vascular structures in solitary small pink lesions—differentiating between good and evil. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:47-50. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0703a10

1. Geller S, Pulitzer M, Brady MS, et al. Dermoscopic assessment of vascular structures in solitary small pink lesions—differentiating between good and evil. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:47-50. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0703a10

Some with long COVID see relief after vaccination

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We’re all vaccinated: Can we go back to the office (unmasked) now?

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

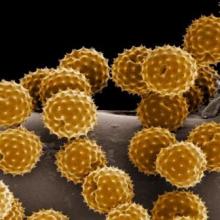

Could pollen be driving COVID-19 infections?

Some scientists say they’ve noticed a pattern to the recurring waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the globe: As pollen levels increased in outdoor air in 31 countries, COVID-19 cases accelerated.

Yet other recent studies point in the opposite direction, suggesting that peaks in pollen seasons coincide with a fall-off in the spread of some respiratory viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza. There’s even some evidence that pollen may compete with the virus that causes COVID-19 and may even help prevent infection.

So which is it? The answer may still be up in the air.

Doctors don’t fully understand what makes some viruses – like the ones that cause the flu – circulate in seasonal patterns.

There are, of course, many theories. These revolve around things like temperature and humidity – viruses tend to prefer colder, drier air – something that’s thought to help them spread more easily in the winter months. People are exposed to less sunlight during the winter, as they spend more time indoors, and the earth points away from the sun, providing some natural shielding. That may play a role because ultraviolet light from the sun acts like a natural disinfectant and may help keep circulating viral levels down.

In addition, exposure to sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, which may help keep our immune responses strong. Extreme temperatures – both cold and hot – also change our behavior, so that we spend more time cloistered indoors, where we can more easily cough and sneeze on each other and generally swap more germs.

Spike in pollen, jump in infections

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds a new variable to this mix – pollen. It relies on data from 248 airborne pollen–monitoring sites in 31 countries. The study also took into account other effects, such as population density, temperature, humidity, and lockdown orders. The study authors found that, when pollen in an area spiked, so did infections, after an average lag of about 4 days. The study authors say pollen seemed to account for, on average, 44% of the infection rate variability between countries.

The study authors say pollen could be a culprit in respiratory infections, not because the viruses hitch a ride on pollen grains and travel into our mouth, eyes, and nose, but because pollen seems to perturb our immune defenses, even if a person isn’t allergic to it.

“When we inhale pollen, they end up on our nasal mucosa, and here they diminish the expression of genes that are important for the defense against airborne viruses,” study author Stefanie Gilles, PhD, chair of environmental medicine at the Technical University of Munich, said in a press conference.

In a study published last year, Dr. Gilles found that mice exposed to pollen made less interferon and other protective chemical signals to the immune system. Those then infected with respiratory syncytial virus had more virus in their bodies, compared with mice not exposed to pollen. She seemed to see the same effect in human volunteers.

The study authors think pollen may cause the body to drop its defenses against the airborne virus that causes COVID-19, too.

“If you’re in a crowded room, and other people are there that are asymptomatic, and you’ve just been breathing in pollen all day long, chances are that you’re going to be more susceptible to the virus,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, a plant physiologist who studies pollen, climate change, and health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York. “Having a mask is obviously really critical in that regard.”

Masks do a great job of blocking pollen, so wearing one is even more important when pollen and viruses are floating around, he says.

Other researchers, however, say that, while the study raises some interesting questions, it can’t prove that pollen is increasing COVID-19 infections.

“Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other,” says Martijn Hoogeveen, PhD, a professor of technical sciences and environment at the Open University in the Netherlands.

Dr. Hoogeveen’s recent study, published in Science of the Total Environment, found that the arrival of pollen season in the Netherlands coincides with the end of flu season, and that COVID-19 infection peaks tend to follow a similar pattern – exactly the opposite of the PNAS study.

Another preprint study, which focused on the Chicago area, found the same thing – as pollen climbs, flu cases drop. The researchers behind that study think pollen may actually compete with viruses in our airways, helping to block them from infecting our cells.

Patterns may be hard to nail down

Why did these studies reach such different conclusions?

Dr. Hoogeveen’s paper focused on a single country and looked at the incidence of flu infections over four seasons, from 2016 to 2020, while the PNAS study collected data on pollen from January through the first week of April 2020.

He thinks that a single season, or really part of a season, may not be long enough to see meaningful patterns, especially considering that this new-to-humans virus was spreading quickly at nearly the same time. He says it will be interesting to follow what happens with COVID-19 infections and pollen in the coming months and years.

Dr. Hoogeveen says that in a large study spanning so many countries it would have been nearly impossible to account for differences in pandemic control strategies. Some countries embraced the use of masks, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing, for example, while others took less stringent measures in order to let the virus run its course in pursuit of herd immunity.

Limiting the study area to a single country or city, he says, helps researchers better understand all the variables that might have been in play along with pollen.

“There is no scientific consensus yet, about what it is driving, and that’s what makes it such an interesting field,” he says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some scientists say they’ve noticed a pattern to the recurring waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the globe: As pollen levels increased in outdoor air in 31 countries, COVID-19 cases accelerated.

Yet other recent studies point in the opposite direction, suggesting that peaks in pollen seasons coincide with a fall-off in the spread of some respiratory viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza. There’s even some evidence that pollen may compete with the virus that causes COVID-19 and may even help prevent infection.

So which is it? The answer may still be up in the air.

Doctors don’t fully understand what makes some viruses – like the ones that cause the flu – circulate in seasonal patterns.

There are, of course, many theories. These revolve around things like temperature and humidity – viruses tend to prefer colder, drier air – something that’s thought to help them spread more easily in the winter months. People are exposed to less sunlight during the winter, as they spend more time indoors, and the earth points away from the sun, providing some natural shielding. That may play a role because ultraviolet light from the sun acts like a natural disinfectant and may help keep circulating viral levels down.

In addition, exposure to sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, which may help keep our immune responses strong. Extreme temperatures – both cold and hot – also change our behavior, so that we spend more time cloistered indoors, where we can more easily cough and sneeze on each other and generally swap more germs.

Spike in pollen, jump in infections

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds a new variable to this mix – pollen. It relies on data from 248 airborne pollen–monitoring sites in 31 countries. The study also took into account other effects, such as population density, temperature, humidity, and lockdown orders. The study authors found that, when pollen in an area spiked, so did infections, after an average lag of about 4 days. The study authors say pollen seemed to account for, on average, 44% of the infection rate variability between countries.

The study authors say pollen could be a culprit in respiratory infections, not because the viruses hitch a ride on pollen grains and travel into our mouth, eyes, and nose, but because pollen seems to perturb our immune defenses, even if a person isn’t allergic to it.

“When we inhale pollen, they end up on our nasal mucosa, and here they diminish the expression of genes that are important for the defense against airborne viruses,” study author Stefanie Gilles, PhD, chair of environmental medicine at the Technical University of Munich, said in a press conference.

In a study published last year, Dr. Gilles found that mice exposed to pollen made less interferon and other protective chemical signals to the immune system. Those then infected with respiratory syncytial virus had more virus in their bodies, compared with mice not exposed to pollen. She seemed to see the same effect in human volunteers.

The study authors think pollen may cause the body to drop its defenses against the airborne virus that causes COVID-19, too.

“If you’re in a crowded room, and other people are there that are asymptomatic, and you’ve just been breathing in pollen all day long, chances are that you’re going to be more susceptible to the virus,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, a plant physiologist who studies pollen, climate change, and health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York. “Having a mask is obviously really critical in that regard.”

Masks do a great job of blocking pollen, so wearing one is even more important when pollen and viruses are floating around, he says.

Other researchers, however, say that, while the study raises some interesting questions, it can’t prove that pollen is increasing COVID-19 infections.

“Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other,” says Martijn Hoogeveen, PhD, a professor of technical sciences and environment at the Open University in the Netherlands.

Dr. Hoogeveen’s recent study, published in Science of the Total Environment, found that the arrival of pollen season in the Netherlands coincides with the end of flu season, and that COVID-19 infection peaks tend to follow a similar pattern – exactly the opposite of the PNAS study.

Another preprint study, which focused on the Chicago area, found the same thing – as pollen climbs, flu cases drop. The researchers behind that study think pollen may actually compete with viruses in our airways, helping to block them from infecting our cells.

Patterns may be hard to nail down

Why did these studies reach such different conclusions?

Dr. Hoogeveen’s paper focused on a single country and looked at the incidence of flu infections over four seasons, from 2016 to 2020, while the PNAS study collected data on pollen from January through the first week of April 2020.

He thinks that a single season, or really part of a season, may not be long enough to see meaningful patterns, especially considering that this new-to-humans virus was spreading quickly at nearly the same time. He says it will be interesting to follow what happens with COVID-19 infections and pollen in the coming months and years.

Dr. Hoogeveen says that in a large study spanning so many countries it would have been nearly impossible to account for differences in pandemic control strategies. Some countries embraced the use of masks, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing, for example, while others took less stringent measures in order to let the virus run its course in pursuit of herd immunity.

Limiting the study area to a single country or city, he says, helps researchers better understand all the variables that might have been in play along with pollen.

“There is no scientific consensus yet, about what it is driving, and that’s what makes it such an interesting field,” he says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Some scientists say they’ve noticed a pattern to the recurring waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections around the globe: As pollen levels increased in outdoor air in 31 countries, COVID-19 cases accelerated.

Yet other recent studies point in the opposite direction, suggesting that peaks in pollen seasons coincide with a fall-off in the spread of some respiratory viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza. There’s even some evidence that pollen may compete with the virus that causes COVID-19 and may even help prevent infection.

So which is it? The answer may still be up in the air.

Doctors don’t fully understand what makes some viruses – like the ones that cause the flu – circulate in seasonal patterns.

There are, of course, many theories. These revolve around things like temperature and humidity – viruses tend to prefer colder, drier air – something that’s thought to help them spread more easily in the winter months. People are exposed to less sunlight during the winter, as they spend more time indoors, and the earth points away from the sun, providing some natural shielding. That may play a role because ultraviolet light from the sun acts like a natural disinfectant and may help keep circulating viral levels down.

In addition, exposure to sunlight helps the body make vitamin D, which may help keep our immune responses strong. Extreme temperatures – both cold and hot – also change our behavior, so that we spend more time cloistered indoors, where we can more easily cough and sneeze on each other and generally swap more germs.

Spike in pollen, jump in infections

The new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds a new variable to this mix – pollen. It relies on data from 248 airborne pollen–monitoring sites in 31 countries. The study also took into account other effects, such as population density, temperature, humidity, and lockdown orders. The study authors found that, when pollen in an area spiked, so did infections, after an average lag of about 4 days. The study authors say pollen seemed to account for, on average, 44% of the infection rate variability between countries.

The study authors say pollen could be a culprit in respiratory infections, not because the viruses hitch a ride on pollen grains and travel into our mouth, eyes, and nose, but because pollen seems to perturb our immune defenses, even if a person isn’t allergic to it.

“When we inhale pollen, they end up on our nasal mucosa, and here they diminish the expression of genes that are important for the defense against airborne viruses,” study author Stefanie Gilles, PhD, chair of environmental medicine at the Technical University of Munich, said in a press conference.

In a study published last year, Dr. Gilles found that mice exposed to pollen made less interferon and other protective chemical signals to the immune system. Those then infected with respiratory syncytial virus had more virus in their bodies, compared with mice not exposed to pollen. She seemed to see the same effect in human volunteers.

The study authors think pollen may cause the body to drop its defenses against the airborne virus that causes COVID-19, too.

“If you’re in a crowded room, and other people are there that are asymptomatic, and you’ve just been breathing in pollen all day long, chances are that you’re going to be more susceptible to the virus,” says Lewis Ziska, PhD, a plant physiologist who studies pollen, climate change, and health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health in New York. “Having a mask is obviously really critical in that regard.”

Masks do a great job of blocking pollen, so wearing one is even more important when pollen and viruses are floating around, he says.

Other researchers, however, say that, while the study raises some interesting questions, it can’t prove that pollen is increasing COVID-19 infections.

“Just because two things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other,” says Martijn Hoogeveen, PhD, a professor of technical sciences and environment at the Open University in the Netherlands.

Dr. Hoogeveen’s recent study, published in Science of the Total Environment, found that the arrival of pollen season in the Netherlands coincides with the end of flu season, and that COVID-19 infection peaks tend to follow a similar pattern – exactly the opposite of the PNAS study.

Another preprint study, which focused on the Chicago area, found the same thing – as pollen climbs, flu cases drop. The researchers behind that study think pollen may actually compete with viruses in our airways, helping to block them from infecting our cells.

Patterns may be hard to nail down

Why did these studies reach such different conclusions?

Dr. Hoogeveen’s paper focused on a single country and looked at the incidence of flu infections over four seasons, from 2016 to 2020, while the PNAS study collected data on pollen from January through the first week of April 2020.

He thinks that a single season, or really part of a season, may not be long enough to see meaningful patterns, especially considering that this new-to-humans virus was spreading quickly at nearly the same time. He says it will be interesting to follow what happens with COVID-19 infections and pollen in the coming months and years.

Dr. Hoogeveen says that in a large study spanning so many countries it would have been nearly impossible to account for differences in pandemic control strategies. Some countries embraced the use of masks, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing, for example, while others took less stringent measures in order to let the virus run its course in pursuit of herd immunity.

Limiting the study area to a single country or city, he says, helps researchers better understand all the variables that might have been in play along with pollen.

“There is no scientific consensus yet, about what it is driving, and that’s what makes it such an interesting field,” he says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This Rash Really Stinks!

ANSWER

The correct diagnosis is Darier disease (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

Darier disease, also known as Darier-White disease or keratosis follicularis, is an inherited defect transmitted by autosomal dominant mode. The pathophysiologic process is a breakdown of cell adhesion that normally binds keratin filaments to tiny connecting fibers called desmosomes.

Darier disease manifests with a “branny” papulosquamous rash, typically arising in the third decade of life and affecting the chest, scalp, back, and intertriginous areas. The nail and intraoral findings noted in this patient are typical. In the author’s experience, the former is more commonly seen and is essentially pathognomic for the disease.

Darier disease is relatively rare, occurring in 1:30,000 to 1:100,000 population, depending on the geographic area studied. Men and women are equally affected, although it is more common in those with darker skin.